HMS Indefatigable (1909) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

HMS ''Indefatigable'' was the

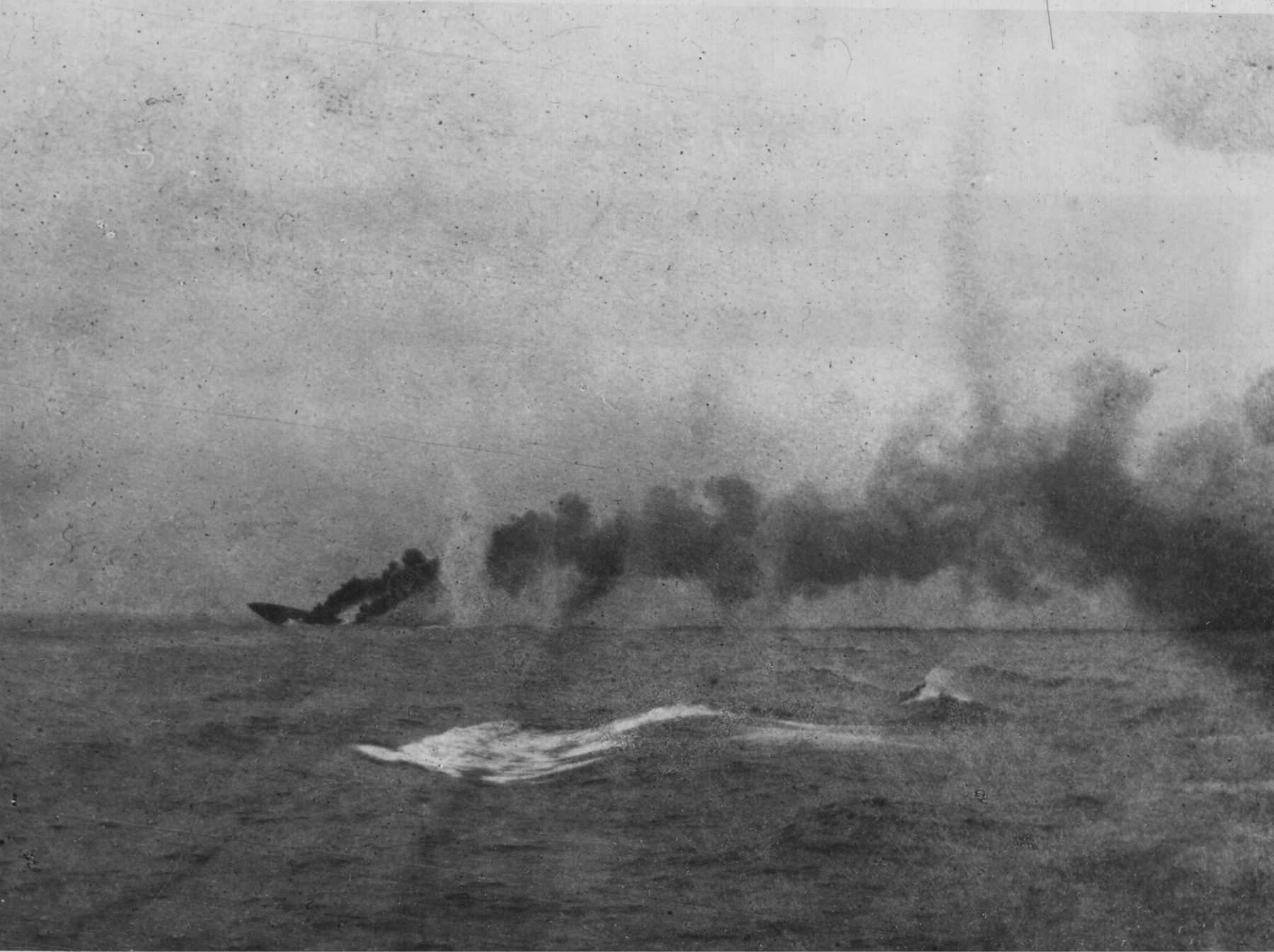

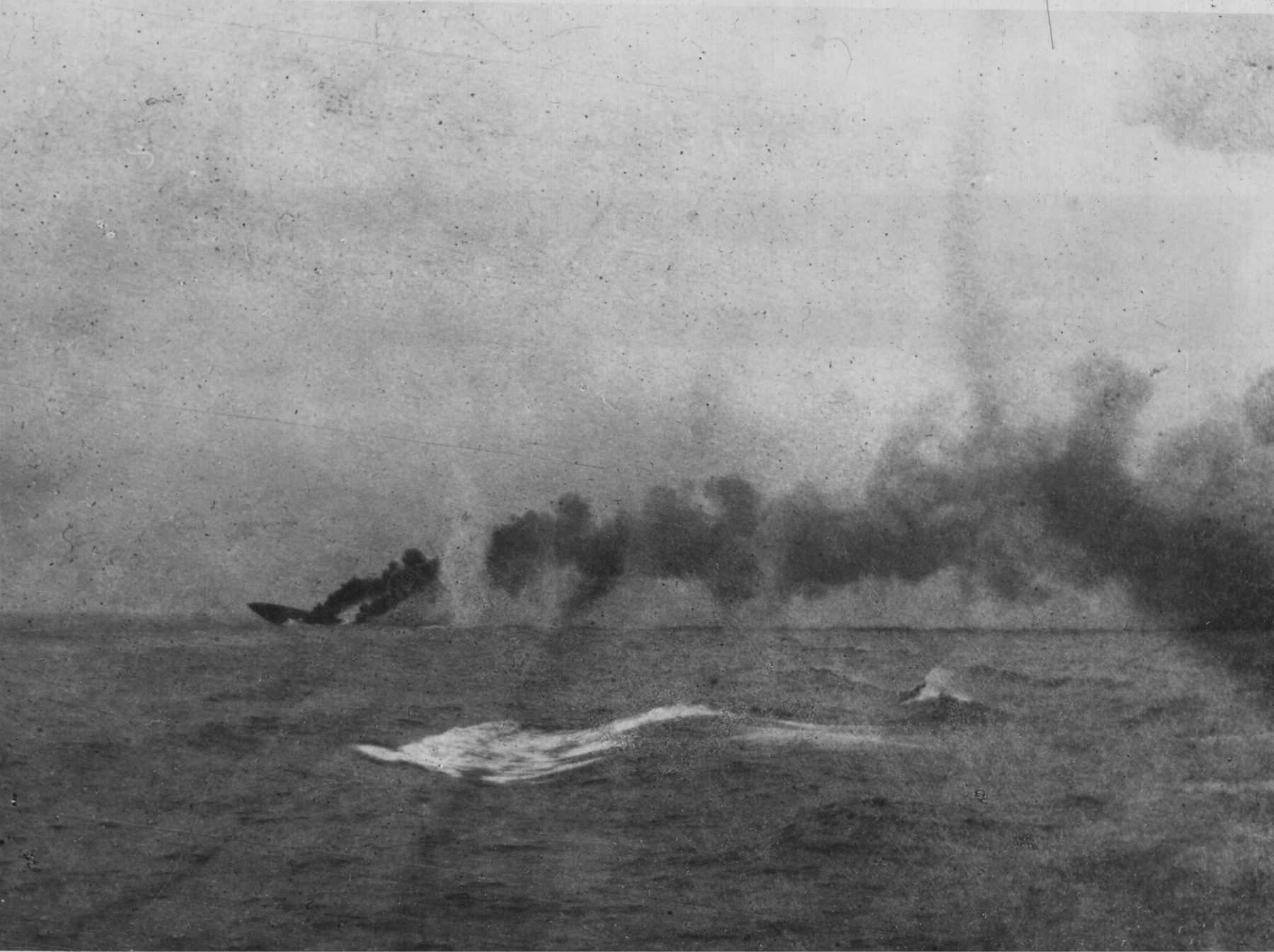

Around 16:00, ''Indefatigable'' was hit around the rear turret by two or three shells from ''Von der Tann''. She fell out of formation to starboard and started sinking towards the stern and listing to port. Her magazines exploded at 16:03 after more hits, one on the

Around 16:00, ''Indefatigable'' was hit around the rear turret by two or three shells from ''Von der Tann''. She fell out of formation to starboard and started sinking towards the stern and listing to port. Her magazines exploded at 16:03 after more hits, one on the

Maritimequest HMS Indefatigable Photo Gallery

Battle of Jutland Crew Lists Project – HMS Indefatigable Crew List

{{DEFAULTSORT:Indefatigable (1909) 1909 ships Indefatigable-class battlecruisers Ships built in Plymouth, Devon Protected wrecks of the United Kingdom Maritime incidents in 1916 Ships sunk at the Battle of Jutland World War I battlecruisers of the United Kingdom Naval magazine explosions

lead ship

The lead ship, name ship, or class leader is the first of a series or class of ships that are all constructed according to the same general design. The term is applicable to naval ships and large civilian vessels.

Large ships are very comple ...

of her class of three battlecruiser

The battlecruiser (also written as battle cruiser or battle-cruiser) was a type of capital ship of the first half of the 20th century. These were similar in displacement, armament and cost to battleships, but differed in form and balance of att ...

s built for the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

during the first decade of the 20th Century. When the First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

began, ''Indefatigable'' was serving with the 2nd Battlecruiser Squadron (BCS) in the Mediterranean, where she unsuccessfully pursued the battlecruiser and the light cruiser

A light cruiser is a type of small or medium-sized warship. The term is a shortening of the phrase "light armored cruiser", describing a small ship that carried armor in the same way as an armored cruiser: a protective belt and deck. Prior to thi ...

of the German Imperial Navy

The Imperial German Navy or the ''Kaiserliche Marine'' (Imperial Navy) was the navy of the German Empire, which existed between 1871 and 1919. It grew out of the small Prussian Navy (from 1867 the North German Federal Navy), which was mainly f ...

as they fled toward the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

. The ship bombarded Ottoman fortifications defending the Dardanelles

The Dardanelles ( ; ; ), also known as the Strait of Gallipoli (after the Gallipoli peninsula) and in classical antiquity as the Hellespont ( ; ), is a narrow, natural strait and internationally significant waterway in northwestern Turkey th ...

on 3 November 1914, then, following a refit in Malta, returned to the United Kingdom in February where she rejoined the 2nd BCS.

''Indefatigable'' was sunk on 31 May 1916 during the Battle of Jutland

The Battle of Jutland () was a naval battle between Britain's Royal Navy Grand Fleet, under Admiral John Jellicoe, 1st Earl Jellicoe, Sir John Jellicoe, and the Imperial German Navy's High Seas Fleet, under Vice-Admiral Reinhard Scheer, durin ...

, the largest naval battle of the war. Part of Vice-Admiral

Vice admiral is a senior naval flag officer rank, usually equivalent to lieutenant general and air marshal. A vice admiral is typically senior to a rear admiral and junior to an admiral.

Australia

In the Royal Australian Navy, the rank of vic ...

Sir David Beatty

Admiral of the Fleet David Richard Beatty, 1st Earl Beatty, (17 January 1871 – 12 March 1936) was a Royal Navy officer. After serving in the Mahdist War and then the response to the Boxer Rebellion, he commanded the Battle Cruiser Fleet at t ...

's Battlecruiser Fleet, she was hit several times in the first minutes of the "Run to the South", the opening phase of the battlecruiser action. Shells from the German battlecruiser caused an explosion ripping a hole in her hull, and a second explosion hurled large pieces of the ship 200 feet (60 m) in the air. Only three of the crew of 1,019 survived.

Design and description

No battlecruisers were ordered after the three ships in 1905 until ''Indefatigable'' became the lone battlecruiser of the 1908–1909 Naval Programme. A newLiberal Government Liberal government may refer to:

Australia

In Australian politics, a Liberal government may refer to the following governments administered by the Liberal Party of Australia:

* Menzies Government (1949–66), several Australian ministries under S ...

had taken power in January 1906 and demanded reductions in naval spending, and the Admiralty

Admiralty most often refers to:

*Admiralty, Hong Kong

* Admiralty (United Kingdom), military department in command of the Royal Navy from 1707 to 1964

*The rank of admiral

*Admiralty law

Admiralty can also refer to:

Buildings

* Admiralty, Tra ...

submitted a reduced programme, requesting dreadnought

The dreadnought was the predominant type of battleship in the early 20th century. The first of the kind, the Royal Navy's , had such an effect when launched in 1906 that similar battleships built after her were referred to as "dreadnoughts", ...

s but no battlecruisers. The Cabinet

Cabinet or The Cabinet may refer to:

Furniture

* Cabinetry, a box-shaped piece of furniture with doors and/or drawers

* Display cabinet, a piece of furniture with one or more transparent glass sheets or transparent polycarbonate sheets

* Filin ...

rejected this proposal in favour of two outmoded armoured cruiser

The armored cruiser was a type of warship of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It was designed like other types of cruisers to operate as a long-range, independent warship, capable of defeating any ship apart from a pre-dreadnought battles ...

s but finally acceded to a request for one battlecruiser instead, after the Admiralty pointed out the need to match the recently published German naval construction plan and to maintain the heavy gun and armour industries. ''Indefatigable''s outline design was prepared in March 1908, and the final design, slightly larger than ''Invincible'' with a revised protection arrangement and additional length amidships to allow her two middle turrets

Turret may refer to:

* Turret (architecture), a small tower that projects above the wall of a building

* Gun turret, a mechanism of a projectile-firing weapon

* Objective turret, an indexable holder of multiple lenses in an optical microscope

* ...

to fire on either broadside, was approved in November 1908. A larger design with more armour and better underwater protection was rejected as too expensive.

''Indefatigable'' had an overall length of , a beam

Beam may refer to:

Streams of particles or energy

*Light beam, or beam of light, a directional projection of light energy

**Laser beam

*Radio beam

*Particle beam, a stream of charged or neutral particles

**Charged particle beam, a spatially lo ...

of , and a draught of at deep load

The displacement or displacement tonnage of a ship is its weight. As the term indicates, it is measured indirectly, using Archimedes' principle, by first calculating the volume of water displaced by the ship, then converting that value into weig ...

. The ship normally displaced and at deep load. She had a crew of 737 officers and ratings.

The ship was powered by two sets of Parsons direct-drive

A direct-drive mechanism is a mechanism design where the force or torque from a prime mover is transmitted directly to the effector device (such as the drive wheels of a vehicle) without involving any intermediate couplings such as a gear train o ...

steam turbine

A steam turbine or steam turbine engine is a machine or heat engine that extracts thermal energy from pressurized steam and uses it to do mechanical work utilising a rotating output shaft. Its modern manifestation was invented by Sir Charles Par ...

s, each driving two propeller shaft

A drive shaft, driveshaft, driving shaft, tailshaft (Australian English), propeller shaft (prop shaft), or Cardan shaft (after Girolamo Cardano) is a component for transmitting mechanical power, torque, and rotation, usually used to connect o ...

s, using steam provided by 31 coal-burning Babcock & Wilcox boiler

A high pressure watertube boiler (also spelled water-tube and water tube) is a type of boiler in which water circulates in tubes heated externally by fire. Fuel is burned inside the furnace, creating hot gas which boils water in the steam-generat ...

s. The turbines were rated at and were intended to give the ship a maximum speed of . During her sea trial

A sea trial or trial trip is the testing phase of a watercraft (including boats, ships, and submarines). It is also referred to as a "shakedown cruise" by many naval personnel. It is usually the last phase of construction and takes place on op ...

s on 10 April 1911, ''Indefatigable'' reached a top speed of from after her propellers were replaced. She carried enough coal and fuel oil

Fuel oil is any of various fractions obtained from the distillation of petroleum (crude oil). Such oils include distillates (the lighter fractions) and residues (the heavier fractions). Fuel oils include heavy fuel oil (bunker fuel), marine f ...

to give her a range of at a cruising speed of .

The ''Indefatigable'' class had a main armament of eight breech-loading

A breechloader is a firearm in which the user loads the ammunition from the breech end of the barrel (i.e., from the rearward, open end of the gun's barrel), as opposed to a muzzleloader, in which the user loads the ammunition from the ( muzzle ...

BL Mark X guns mounted in four hydraulically powered twin-gun turrets. Two turrets were mounted fore and aft on the centreline, identified as 'A' and 'X' respectively. The other two were wing turrets mounted amidships and staggered diagonally: 'P' was forward and to port

A port is a maritime facility comprising one or more wharves or loading areas, where ships load and discharge cargo and passengers. Although usually situated on a sea coast or estuary, ports can also be found far inland, such as Hamburg, Manch ...

of the centre funnel, while 'Q' was situated starboard

Port and starboard are Glossary of nautical terms (M-Z), nautical terms for watercraft and spacecraft, referring respectively to the left and right sides of the vessel, when aboard and facing the Bow (watercraft), bow (front).

Vessels with bil ...

and aft

This list of ship directions provides succinct definitions for terms applying to spatial orientation in a marine environment or location on a vessel, such as ''fore'', ''aft'', ''astern'', ''aboard'', or ''topside''.

Terms

* Abaft (prepositi ...

. 'P' and 'Q' turrets had some limited ability to fire to the opposite side. Their secondary armament

Secondary armaments are smaller, faster-firing weapons that are typically effective at a shorter range than the main battery, main (heavy) weapons on military systems, including battleship- and cruiser-type warships, tanks/armored personnel c ...

consisted of sixteen BL Mark VII guns positioned in the superstructure

A superstructure is an upward extension of an existing structure above a baseline. This term is applied to various kinds of physical structures such as buildings, bridges, or ships.

Aboard ships and large boats

On water craft, the superstruct ...

. They mounted two submerged torpedo tube

A torpedo tube is a cylindrical device for launching torpedoes.

There are two main types of torpedo tube: underwater tubes fitted to submarines and some surface ships, and deck-mounted units (also referred to as torpedo launchers) installed aboa ...

s, one on each side aft of 'X' barbette

Barbettes are several types of gun emplacement in terrestrial fortifications or on naval ships.

In recent naval usage, a barbette is a protective circular armour support for a heavy gun turret. This evolved from earlier forms of gun protection ...

, and twelve torpedoes were carried.

The ''Indefatigable''s were protected by a waterline

The waterline is the line where the hull of a ship meets the surface of the water.

A waterline can also refer to any line on a ship's hull that is parallel to the water's surface when the ship is afloat in a level trimmed position. Hence, wate ...

armoured belt that extended between and covered the end barbette

Barbettes are several types of gun emplacement in terrestrial fortifications or on naval ships.

In recent naval usage, a barbette is a protective circular armour support for a heavy gun turret. This evolved from earlier forms of gun protection ...

s. Their armoured deck ranged in thickness between with the thickest portions protecting the steering gear in the stern. The turret faces were thick, and the turrets were supported by barbettes of the same thickness.

''Indefatigable'' was unique among British battlecruisers in having an armoured spotting and signal tower behind the conning tower

A conning tower is a raised platform on a ship or submarine, often armoured, from which an officer in charge can conn (nautical), conn (conduct or control) the vessel, controlling movements of the ship by giving orders to those responsible for t ...

, protected by of armour. However, the spotting tower was of limited use, as its view was obscured by the conning tower in front of it and the legs of the foremast and superstructure behind it. During a pre-war refit, a rangefinder

A rangefinder (also rangefinding telemeter, depending on the context) is a device used to Length measurement, measure distances to remote objects. Originally optical devices used in surveying, they soon found applications in other fields, suc ...

was added to the rear of the 'A' turret roof, and this turret was equipped to control the entire main armament as an emergency backup for the normal fire-control positions.

Wartime modifications

''Indefatigable'' received a singleQF 3-inch 20 cwt

The QF 3-inch 20 cwt anti-aircraft gun became the standard anti-aircraft gun used in the home defence of the United Kingdom against German Zeppelins airships and bombers and on the Western Front in World War I. It was also common on British warsh ...

"cwt" is the abbreviation for hundredweight

The hundredweight (abbreviation: cwt), formerly also known as the centum weight or quintal, is a British imperial and United States customary unit of weight or mass. Its value differs between the United States customary and British imperial sy ...

, 20 cwt referring to the weight of the gun. anti-aircraft

Anti-aircraft warfare (AAW) is the counter to aerial warfare and includes "all measures designed to nullify or reduce the effectiveness of hostile air action".AAP-6 It encompasses surface-based, subsurface ( submarine-launched), and air-ba ...

gun on a high-angle Mark II mount in March 1915. It was provided with 500 rounds. All of her 4-inch guns were enclosed in casemate

A casemate is a fortified gun emplacement or armoured structure from which guns are fired, in a fortification, warship, or armoured fighting vehicle.Webster's New Collegiate Dictionary

When referring to antiquity, the term "casemate wall" ...

s and given gun shield

A U.S. Marine manning an M240 machine gun equipped with a gun shield

A gun shield is a flat (or sometimes curved) piece of armor designed to be mounted on a crew-served weapon such as a machine gun, automatic grenade launcher, or artillery pie ...

s during a refit in November 1915 to better protect the gun crews from weather and enemy action, although two aft guns were removed at the same time.Campbell (1978), p. 13.

She received a fire-control director between mid-1915 and May 1916 that centralised fire control under the director officer who now fired the guns. The turret crewmen merely had to follow pointers transmitted from the director to align their guns on the target. This greatly increased accuracy since the ship's roll no longer dispersed the shells as each turret fired on its own; also, the fire-control director could more easily spot the fall of the shells.

Service

Early career

''Indefatigable'' was laid down at the Devonport Dockyard,Plymouth

Plymouth ( ) is a port city status in the United Kingdom, city and unitary authority in Devon, South West England. It is located on Devon's south coast between the rivers River Plym, Plym and River Tamar, Tamar, about southwest of Exeter and ...

on 23 February 1909. She was launched on 28 October 1909 and was completed on 24 February 1911. Upon commissioning, ''Indefatigable'' served in the 1st Cruiser Squadron, which in January 1913 was renamed the 1st Battlecruiser Squadron

The First Battlecruiser Squadron was a Royal Navy squadron of battlecruisers that saw service as part of the Grand Fleet during the First World War. It was created in 1909 as the First Cruiser Squadron and was renamed in 1913 to First Battle Cr ...

(BCS). C. F. Sowerby was appointed captain on 24 February 1913. In December of the same year, she transferred to the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern ...

, where she joined the 2nd Battlecruiser Squadron.

Pursuit of ''Goeben'' and ''Breslau''

''Indefatigable'', accompanied by the battlecruiser and under the command ofAdmiral

Admiral is one of the highest ranks in many navies. In the Commonwealth nations and the United States, a "full" admiral is equivalent to a "full" general in the army or the air force. Admiral is ranked above vice admiral and below admiral of ...

Sir Berkeley Milne, encountered the German battlecruiser ''Goeben'' and the light cruiser

A light cruiser is a type of small or medium-sized warship. The term is a shortening of the phrase "light armored cruiser", describing a small ship that carried armor in the same way as an armored cruiser: a protective belt and deck. Prior to thi ...

''Breslau'' on the morning of 4 August 1914, which were headed east after a cursory bombardment of the French Algerian port of Philippeville

Philippeville (; ) is a city and municipality of Wallonia located in the province of Namur, Belgium. The Philippeville municipality includes the former municipalities of Fagnolle, Franchimont, Jamagne, Jamiolle, Merlemont, Neuville, Om ...

. Britain and Germany were not yet at war, so Milne turned to shadow the Germans as they headed back to Messina

Messina ( , ; ; ; ) is a harbour city and the capital city, capital of the Italian Metropolitan City of Messina. It is the third largest city on the island of Sicily, and the 13th largest city in Italy, with a population of 216,918 inhabitants ...

to re-coal. All three battlecruisers had problems with their boilers, but ''Goeben'' and ''Breslau'' were able to break contact and reached Messina by the morning of the 5th. By this time, Germany had invaded Belgium

Belgium, officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. Situated in a coastal lowland region known as the Low Countries, it is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeas ...

and war had been declared, but an Admiralty order to respect Italian neutrality and stay more than from the Italian coast precluded entering the Strait of Messina

The Strait of Messina (; ) is a narrow strait between the eastern tip of Sicily (Punta del Faro) and the western tip of Calabria (Punta Pezzo) in Southern Italy. It connects the Tyrrhenian Sea to the north with the Ionian Sea to the south, with ...

, from which they could have observed the port directly. Therefore, Milne stationed and ''Indefatigable'' at the northern exit of the strait, expecting the Germans to break out to the west where they could attack French troop transports. He stationed the light cruiser at the southern exit, and sent ''Indomitable'' to coal at Bizerte

Bizerte (, ) is the capital and largest city of Bizerte Governorate in northern Tunisia. It is the List of northernmost items, northernmost city in Africa, located north of the capital Tunis. It is also known as the last town to remain under Fr ...

, where she was ready for action in the Western Mediterranean.

The Germans sortie

A sortie (from the French word meaning ''exit'' or from Latin root ''surgere'' meaning to "rise up") is a deployment or dispatch of one military unit, be it an aircraft, ship, or troops, from a strongpoint. The term originated in siege warf ...

d from Messina on 6 August and headed east, toward Constantinople

Constantinople (#Names of Constantinople, see other names) was a historical city located on the Bosporus that served as the capital of the Roman Empire, Roman, Byzantine Empire, Byzantine, Latin Empire, Latin, and Ottoman Empire, Ottoman empire ...

, trailed by ''Gloucester''. Milne, still expecting Rear-Admiral

Rear admiral is a flag officer rank used by English-speaking navies. In most European navies, the equivalent rank is called counter admiral.

Rear admiral is usually immediately senior to commodore and immediately below vice admiral. It is ...

Wilhelm Souchon

Wilhelm Anton Souchon (; 2 June 1864 – 13 January 1946) was a German admiral in World War I. Souchon commanded the '' Kaiserliche Marine''s Mediterranean squadron in the early days of the war. His initiatives played a major part in the entry ...

to turn west, kept the battlecruisers at Malta

Malta, officially the Republic of Malta, is an island country in Southern Europe located in the Mediterranean Sea, between Sicily and North Africa. It consists of an archipelago south of Italy, east of Tunisia, and north of Libya. The two ...

until shortly after midnight on 8 August when he set sail at a leisurely for Cape Matapan

Cape Matapan (, Maniot dialect: Ματαπά), also called Cape Tainaron or Taenarum (), or Cape Tenaro, is situated at the end of the Mani Peninsula, Greece. Cape Matapan is the southernmost point of mainland Greece, and the second southe ...

, where ''Goeben'' had been spotted eight hours earlier. At 14:30,The times used in this article are in UT, which is one hour behind CET

CET or cet may refer to:

Places

* Cet, Albania

* Cet, standard astronomical abbreviation for the constellation Cetus

* Colchester Town railway station (National Rail code CET), in Colchester, England

Arts, entertainment, and media

* Comcast En ...

, which is often used in German works. he received an incorrect message from the Admiralty stating that Britain was at war with Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, also referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Dual Monarchy or the Habsburg Monarchy, was a multi-national constitutional monarchy in Central Europe#Before World War I, Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. A military ...

. War would not actually be declared until 12 August, and the order was countermanded four hours later, but Milne gave up the hunt for ''Goeben'', following his standing orders to guard the Adriatic against an Austrian break-out attempt. On 9 August, Milne was given clear orders to "chase ''Goeben'' which had passed Cape Matapan on the 7th steering north-east."Massie, pp. 45–46. Milne still did not believe that Souchon was heading for the Dardanelles, and so he resolved to guard the exit from the Aegean, unaware that the ''Goeben'' did not intend to come out.

On 3 November 1914, Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

, then First Lord of the Admiralty

First Lord of the Admiralty, or formally the Office of the First Lord of the Admiralty, was the title of the political head of the English and later British Royal Navy. He was the government's senior adviser on all naval affairs, responsible f ...

, ordered the first British attack on the Dardanelles following the commencement of hostilities between Ottoman Turkey and Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

. The attack was carried out by ''Indomitable'' and ''Indefatigable'', as well as the French pre-dreadnought battleship

Pre-dreadnought battleships were sea-going battleships built from the mid- to late- 1880s to the early 1900s. Their designs were conceived before the appearance of in 1906 and their classification as "pre-dreadnought" is retrospectively appli ...

s and . The intention of the attack was to test the fortifications and measure the Turkish response. The results were deceptively encouraging. In a twenty-minute bombardment, a single shell struck the magazine of the fort at Sedd el Bahr

Sedd el Bahr (, , meaning "Walls of the Sea") is a village in the Eceabat District, Çanakkale Province, Turkey. It is located at Cape Helles on the Gallipoli peninsula in Turkey. The village lies east of the cape, on the shore of the Dardanelle ...

at the tip of the Gallipoli peninsula, displacing (but not destroying) 10 guns and killing 86 Turkish soldiers. The most significant consequence was that the attention of the Turks was drawn to strengthening their defences, and they set about expanding the mine field. This attack actually took place before Britain's formal declaration of war against the Ottoman Empire on 6 November. ''Indefatigable'' remained in the Mediterranean until she was relieved by ''Inflexible'' on 24 January 1915 and proceeded to Malta for a refit; she then sailed to England on 14 February and joined the 2nd BCS upon her arrival. The ship conducted uneventful patrols of the North Sea for the next year and a half. She was the temporary flagship of the 2nd BCS during April–May 1916, while her half-sister

A sibling is a relative that shares at least one parent with the other person. A male sibling is a brother, and a female sibling is a sister. A person with no siblings is an only child.

While some circumstances can cause siblings to be raise ...

was under repair after colliding with ''Indefatigable''s other half-sister .

Battle of Jutland

On 31 May 1916, the 2nd BCS consisted of ''New Zealand'' (flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of navy, naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically ...

of Rear-Admiral William Pakenham) and ''Indefatigable''. The squadron was assigned to Admiral Beatty's Battlecruiser Fleet which had put to sea to intercept a sortie by the High Seas Fleet

The High Seas Fleet () was the battle fleet of the German Empire, German Imperial German Navy, Imperial Navy and saw action during the First World War. In February 1907, the Home Fleet () was renamed the High Seas Fleet. Admiral Alfred von Tirpi ...

into the North Sea. The British were able to decode the German radio messages and left their bases before the Germans put to sea. Admiral Franz von Hipper

Franz Ritter von Hipper (born Franz Hipper; 13 September 1863 – 25 May 1932) was an admiral in the German Imperial Navy, (''Kaiserliche Marine'') who played an important role in the naval warfare of World War I. Franz von Hipper joined th ...

's battlecruisers spotted the Battlecruiser Fleet to their west at 15:20, but Beatty's ships did not spot the Germans to their east until 15:30. Two minutes later, he ordered a course change to east south-east to position himself astride the German's line of retreat and called his ships' crews to action stations. He also ordered the 2nd BCS, which had been leading, to fall in astern

This list of ship directions provides succinct definitions for terms applying to spatial orientation in a marine environment or location on a vessel, such as ''fore'', ''aft'', ''astern'', ''aboard'', or ''topside''.

Terms

* Abaft (prepositi ...

of the 1st BCS. Hipper ordered his ships to turn to starboard, away from the British, to assume a south-easterly course, and to reduce speed to to allow three light cruisers of the 2nd Scouting Group to catch up. With this turn Hipper was falling back on the High Seas Fleet, then about behind him. Around this time Beatty altered course to the east as it was quickly apparent that he was still too far north to cut off Hipper.

This began what was to be called the "Run to the South" as Beatty changed course to steer east south-east at 15:45, paralleling Hipper's course, now that the range closed to under . The Germans opened fire first at 15:48, followed by the British. The British ships were still in the process of making their turn as only the two leading ships, and , had steadied on their course when the Germans opened fire. The British formation was echeloned to the right with ''Indefatigable'' in the rear and furthest to the west, and ''New Zealand'' ahead of her and slightly further east. The German fire was accurate from the beginning, but the British overestimated the range as the German ships blended into the haze. ''Indefatigable'' aimed at and ''New Zealand'' targeted while remaining unengaged herself. By 15:54, the range was down to and Beatty ordered a course change two points

A point is a small dot or the sharp tip of something. Point or points may refer to:

Mathematics

* Point (geometry), an entity that has a location in space or on a plane, but has no extent; more generally, an element of some abstract topologica ...

to starboard to open up the range at 15:57.

Around 16:00, ''Indefatigable'' was hit around the rear turret by two or three shells from ''Von der Tann''. She fell out of formation to starboard and started sinking towards the stern and listing to port. Her magazines exploded at 16:03 after more hits, one on the

Around 16:00, ''Indefatigable'' was hit around the rear turret by two or three shells from ''Von der Tann''. She fell out of formation to starboard and started sinking towards the stern and listing to port. Her magazines exploded at 16:03 after more hits, one on the forecastle

The forecastle ( ; contracted as fo'c'sle or fo'c's'le) is the upper deck (ship), deck of a sailing ship forward of the foremast, or, historically, the forward part of a ship with the sailors' living quarters. Related to the latter meaning is t ...

and another on the forward turret. Smoke and flames gushed from the forward part of the ship and large pieces were thrown into the air. It has been thought that the most likely cause of her loss was a deflagration

Deflagration (Lat: ''de + flagrare'', 'to burn down') is subsonic combustion in which a pre-mixed flame propagates through an explosive or a mixture of fuel and oxidizer. Deflagrations in high and low explosives or fuel–oxidizer mixtures ma ...

or low-order explosion in 'X' magazine that blew out her bottom and severed the steering control shafts, followed by the explosion of her forward magazines from the second volley. More recent archaeological evidence shows that the ship was actually blown in half within the opening minutes of the engagement with ''Von der Tann'' which fired only fifty-two shells at ''Indefatigable'' before the fore part of the ship also exploded.McCartney (2017b), pp. 317–329 Of her crew of 1,019, only three survived. While still in the water, two survivors, Able Seaman

An able seaman (AB) is a seaman and member of the deck department of a merchant ship with more than two years' experience at sea and considered "well acquainted with his duty". An AB may work as a watchstander, a day worker, or a combination ...

Frederick Arthur Gordon Elliott and Leading Signalman Charles Farmer, found ''Indefatigable's'' captain, C.F. Sowerby, who was badly wounded. Elliott and Farmer were later rescued by the German torpedo boat

A torpedo boat is a relatively small and fast naval ship designed to carry torpedoes into battle. The first designs were steam-powered craft dedicated to ramming enemy ships with explosive spar torpedoes. Later evolutions launched variants of ...

, but by then Sowerby had died of his injuries. A third survivor, Signalman John Bowyer, was picked up by another unknown German ship. He was incorrectly reported as a crew member from in ''The Times'' on 24 June 1916.

''Indefatigable'' today

''Indefatigable'', along with the other Jutland wrecks, was belatedly declared a protected place under theProtection of Military Remains Act 1986

The Protection of Military Remains Act 1986 (1986 c. 35) is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that provides protection for the wreckage of military aircraft and designated military vessels. The Act provides for two types of prot ...

, to discourage further damage to the resting place of 1,016 men. Mount Indefatigable in the Canadian Rockies

The Canadian Rockies () or Canadian Rocky Mountains, comprising both the Alberta Rockies and the British Columbian Rockies, is the Canadian segment of the North American Rocky Mountains. It is the easternmost part of the Canadian Cordillera, w ...

was named after the battlecruiser in 1917. The wreck was identified in 2001, when it was found to have been heavily salvaged sometime in the past.McCartney (2017a), pp. 196–204 The most recent survey of the wreck by nautical archaeologist Innes McCartney

Innes McCartney (born 1964) is a British nautical archaeologist and historian. He is a Visiting Fellow at Bournemouth University in the UK.

Career

McCartney is a nautical archaeologist specializing in the interaction of shipwreck archaeology ...

revealed that the initial hits on the ship by ''Von der Tann'' caused 'X' turret magazine to detonate, blowing off a portion of the ship from forward of the turret to the stern

The stern is the back or aft-most part of a ship or boat, technically defined as the area built up over the sternpost, extending upwards from the counter rail to the taffrail. The stern lies opposite the bow, the foremost part of a ship. O ...

. The supersonic shock-wave such an explosion generated was probably the reason for the very heavy loss of life on board. The fore part of the ship simply drifted on under its own momentum, still under fire, until it foundered

Shipwrecking is any event causing a ship to wreck, such as a collision causing the ship to sink; the stranding of a ship on rocks, land or shoal; poor maintenance, resulting in a lack of seaworthiness; or the destruction of a ship either intent ...

. The two halves of the wreck are separated on the seabed by a linear distance of over . The stern portion had not previously been discovered.

Notes

Citations

References

* * * * * * * * * * *External links

Maritimequest HMS Indefatigable Photo Gallery

Battle of Jutland Crew Lists Project – HMS Indefatigable Crew List

{{DEFAULTSORT:Indefatigable (1909) 1909 ships Indefatigable-class battlecruisers Ships built in Plymouth, Devon Protected wrecks of the United Kingdom Maritime incidents in 1916 Ships sunk at the Battle of Jutland World War I battlecruisers of the United Kingdom Naval magazine explosions