HMS Bounty on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

His Majesty's ship the Bounty, also known as the Bounty, HMS ''Bounty'', or HMAV (His Majesty's Armed Vessel) ''Bounty'', was a British

His Majesty's ship the Bounty, also known as the Bounty, HMS ''Bounty'', or HMAV (His Majesty's Armed Vessel) ''Bounty'', was a British

After five months in Tahiti, ''Bounty'' set sail with her breadfruit cargo on 4 April 1789. Some west of Tahiti, near

After five months in Tahiti, ''Bounty'' set sail with her breadfruit cargo on 4 April 1789. Some west of Tahiti, near  The mutineers remained undetected on Pitcairn until February 1808, when sole remaining mutineer

The mutineers remained undetected on Pitcairn until February 1808, when sole remaining mutineer

The details of the voyage of ''Bounty'' are very well documented, largely due to the effort of Bligh to maintain an accurate log before, during, and after the actual mutiny. ''Bounty''s crew list is also well chronicled.

Bligh's original log remained intact throughout his ordeal and was used as a major piece of evidence in his own trial for the loss of ''Bounty'', as well as the subsequent trial of captured mutineers. The original log is presently maintained at the

The details of the voyage of ''Bounty'' are very well documented, largely due to the effort of Bligh to maintain an accurate log before, during, and after the actual mutiny. ''Bounty''s crew list is also well chronicled.

Bligh's original log remained intact throughout his ordeal and was used as a major piece of evidence in his own trial for the loss of ''Bounty'', as well as the subsequent trial of captured mutineers. The original log is presently maintained at the

In the immediate wake of the mutiny, all but four of the loyal crew joined Bligh in the long boat for the voyage to Timor, and eventually made it safely back to England, unless otherwise noted in the table below. Four were detained against their will on ''Bounty'' for their needed skills and for lack of space on the long boat. The mutineers first returned to Tahiti, where most of the survivors were later captured by ''Pandora'' and taken to England for trial. Nine mutineers continued their flight from the law and eventually settled on Pitcairn Island, where all but one died before their fate became known to the outside world.

In the immediate wake of the mutiny, all but four of the loyal crew joined Bligh in the long boat for the voyage to Timor, and eventually made it safely back to England, unless otherwise noted in the table below. Four were detained against their will on ''Bounty'' for their needed skills and for lack of space on the long boat. The mutineers first returned to Tahiti, where most of the survivors were later captured by ''Pandora'' and taken to England for trial. Nine mutineers continued their flight from the law and eventually settled on Pitcairn Island, where all but one died before their fate became known to the outside world.

When the 1935 film ''

When the 1935 film ''

Photo gallery of HMS ''Bounty'' replica at Tall Ships Nova Scotia 2009 and 2012.

{{DEFAULTSORT:Bounty, Hms 1784 ships 1957 archaeological discoveries Full-rigged ships History of the Pitcairn Islands History of the Royal Navy Individual sailing vessels Mutiny on the Bounty Ships built on the Humber Replica ships Maritime incidents in 1790 Maritime folklore Shipwrecks in the Pacific Ocean Colliers

His Majesty's ship the Bounty, also known as the Bounty, HMS ''Bounty'', or HMAV (His Majesty's Armed Vessel) ''Bounty'', was a British

His Majesty's ship the Bounty, also known as the Bounty, HMS ''Bounty'', or HMAV (His Majesty's Armed Vessel) ''Bounty'', was a British merchant ship

A merchant ship, merchant vessel, trading vessel, or merchantman is a watercraft that transports cargo or carries passengers for hire. This is in contrast to pleasure craft, which are used for personal recreation, and naval ships, which are ...

that the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

purchased in 1787 for a botanical mission. The ship was sent to the South Pacific Ocean

South is one of the cardinal directions or compass points. The direction is the opposite of north and is perpendicular to both west and east.

Etymology

The word ''south'' comes from Old English ''sūþ'', from earlier Proto-Germanic ''*sunþa ...

under the command of William Bligh

William Bligh (9 September 1754 – 7 December 1817) was a Vice-admiral (Royal Navy), Royal Navy vice-admiral and colonial administrator who served as the governor of New South Wales from 1806 to 1808. He is best known for his role in the Muti ...

to acquire breadfruit

Breadfruit (''Artocarpus altilis'') is a species of flowering tree in the mulberry and jackfruit family ( Moraceae) believed to have been selectively bred in Polynesia from the breadnut ('' Artocarpus camansi''). Breadfruit was spread into ...

plants and transport them to the British West Indies

The British West Indies (BWI) were the territories in the West Indies under British Empire, British rule, including Anguilla, the Cayman Islands, the Turks and Caicos Islands, Montserrat, the British Virgin Islands, Bermuda, Antigua and Barb ...

. That mission was never completed owing to a 1789 mutiny

Mutiny is a revolt among a group of people (typically of a military or a crew) to oppose, change, or remove superiors or their orders. The term is commonly used for insubordination by members of the military against an officer or superior, ...

led by acting lieutenant Fletcher Christian, an incident now popularly known as the Mutiny on the ''Bounty''. The mutineers later burned ''Bounty'' while she was moored at Pitcairn Island in the Southern Pacific Ocean in 1790. An American adventurer helped land several remains of ''Bounty'' in 1957.

Origin and description

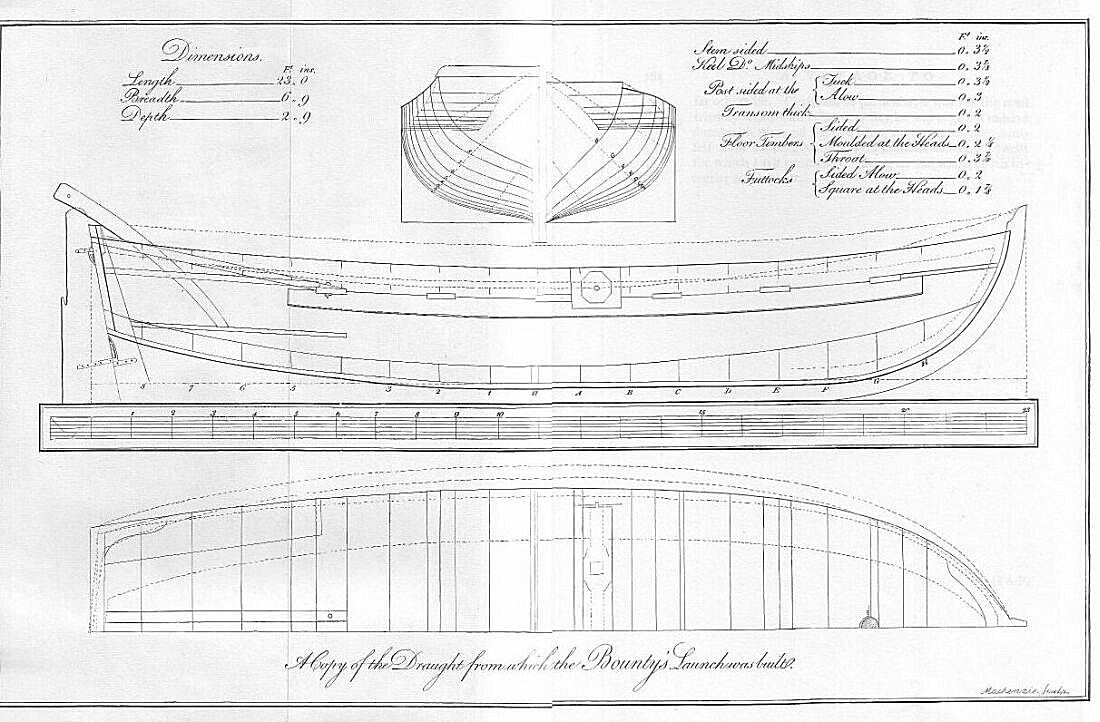

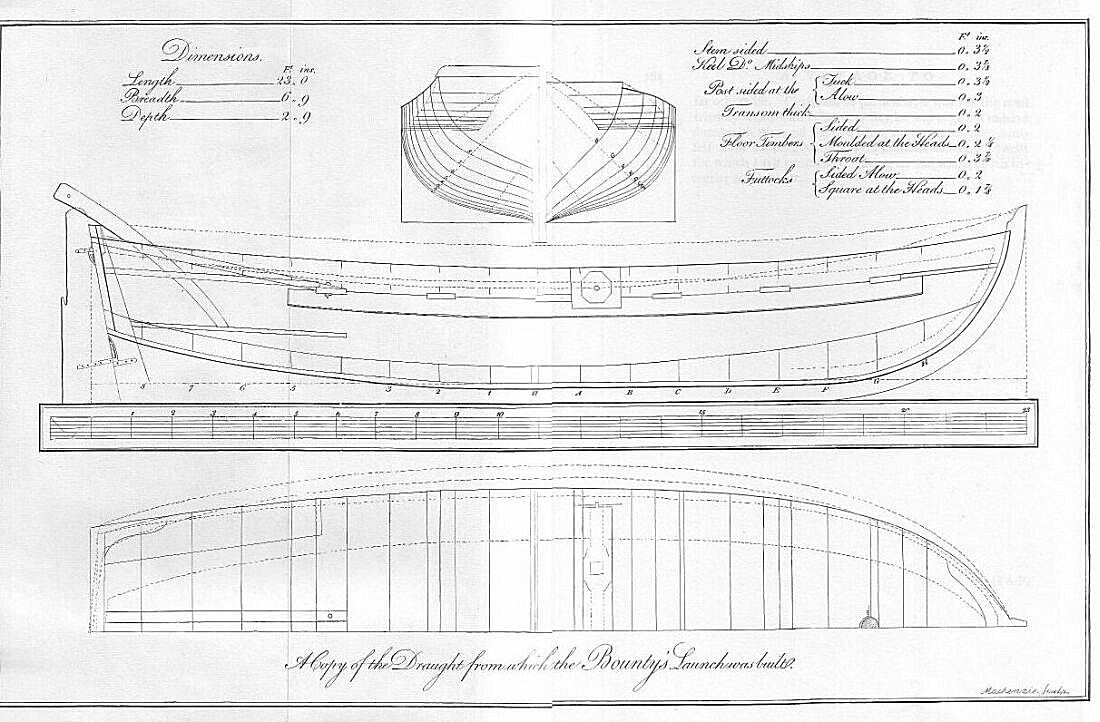

''Bounty'' was originally the collier ''Bethia,'' which was reportedly built in 1784 atBlaydes Yard

Blaydes' Yard was a private shipbuilder in Kingston upon Hull, England, founded in the 18th century which fulfilled multiple Royal Navy contracts. Her most notable ship was HMS Bounty, HMS ''Bounty'' famed for its mutiny.

History

Hugh Blaydes ...

in Hull, Yorkshire

Yorkshire ( ) is an area of Northern England which was History of Yorkshire, historically a county. Despite no longer being used for administration, Yorkshire retains a strong regional identity. The county was named after its county town, the ...

. The Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

purchased her for £1,950 on 23 May 1787 (), and subsequently refit

Refitting or refit of boats and marine vessels includes repairing, fixing, restoring, renewing, mending, and renovating an old vessel. Refitting has become one of the most important activities inside a shipyard. It offers a variety of services for ...

ted the ship and renamed her ''Bounty.'' The ship was relatively small at 215 tons, but had three masts and was full-rigged. After conversion for the breadfruit expedition, she was equipped with four cannons and ten swivel gun

A swivel gun (or simply swivel) is a small cannon mounted on a swiveling stand or fork which allows a very wide arc of movement. Another type of firearm referred to as a swivel gun was an early flintlock combination gun with two barrels that rot ...

s.

1787 breadfruit expedition

Preparations

The Royal Navy had purchased ''Bethia'' for the sole purpose of carrying out the mission of acquiringbreadfruit

Breadfruit (''Artocarpus altilis'') is a species of flowering tree in the mulberry and jackfruit family ( Moraceae) believed to have been selectively bred in Polynesia from the breadnut ('' Artocarpus camansi''). Breadfruit was spread into ...

plants from Tahiti

Tahiti (; Tahitian language, Tahitian , ; ) is the largest island of the Windward Islands (Society Islands), Windward group of the Society Islands in French Polynesia, an overseas collectivity of France. It is located in the central part of t ...

, which would then be transported to the British West Indies

The British West Indies (BWI) were the territories in the West Indies under British Empire, British rule, including Anguilla, the Cayman Islands, the Turks and Caicos Islands, Montserrat, the British Virgin Islands, Bermuda, Antigua and Barb ...

as a cheap source of food for the region's slaves

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

. English naturalist Sir Joseph Banks

Sir Joseph Banks, 1st Baronet, (19 June 1820) was an English naturalist, botanist, and patron of the natural sciences.

Banks made his name on the 1766 natural-history expedition to Newfoundland and Labrador. He took part in Captain James Co ...

originated the idea and promoted it in Britain, recommending Lieutenant William Bligh

William Bligh (9 September 1754 – 7 December 1817) was a Vice-admiral (Royal Navy), Royal Navy vice-admiral and colonial administrator who served as the governor of New South Wales from 1806 to 1808. He is best known for his role in the Muti ...

to the Admiralty as the mission's commander. Bligh, in turn, was promoted in rank via a prize offered by the Royal Society of Arts

The Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce, commonly known as the Royal Society of Arts (RSA), is a learned society that champions innovation and progress across a multitude of sectors by fostering creativity, s ...

.

In June 1787, ''Bounty'' was refitted at Deptford

Deptford is an area on the south bank of the River Thames in southeast London, in the Royal Borough of Greenwich and London Borough of Lewisham. It is named after a Ford (crossing), ford of the River Ravensbourne. From the mid 16th century ...

. The great cabin was converted to house the potted breadfruit plants, and gratings were fitted to the upper deck. William Bligh was appointed commanding lieutenant of ''Bounty'' on 16 August 1787 at the age of 33, after a career that included a tour as sailing master

The master, or sailing master, is a historical rank for a naval Officer (armed forces), officer trained in and responsible for the navigation of a sailing ship, sailing vessel.

In the Royal Navy, the master was originally a warrant officer who ...

of the sloop ''Resolution'' during the third voyage of James Cook

James Cook's third and final voyage (12 July 1776 – 4 October 1780) was a British attempt to discover the Northwest Passage between the Atlantic ocean and the Pacific coast of North America. The attempt failed and Death of James Cook, Cook ...

, which lasted from 1776 to 1780. The ship's complement consisted of 46 men, with Bligh as the sole commissioned officer, two civilian gardeners to care for the breadfruit plants and the remaining crew consisting of enlisted Royal Navy personnel.

Voyage out

On 23 December 1787, ''Bounty'' sailed fromSpithead

Spithead is an eastern area of the Solent and a roadstead for vessels off Gilkicker Point in Hampshire, England. It is protected from all winds except those from the southeast, with the Isle of Wight lying to the south-west. Spithead and the ch ...

for Tahiti

Tahiti (; Tahitian language, Tahitian , ; ) is the largest island of the Windward Islands (Society Islands), Windward group of the Society Islands in French Polynesia, an overseas collectivity of France. It is located in the central part of t ...

. For a full month, the crew attempted to take the ship west, around South America's Cape Horn

Cape Horn (, ) is the southernmost headland of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago of southern Chile, and is located on the small Hornos Island. Although not the most southerly point of South America (which is Águila Islet), Cape Horn marks the nor ...

, but adverse weather prevented this. Bligh then proceeded east, rounding the southern tip of Africa (Cape Agulhas

Cape Agulhas (; , "Cape of Needles") is a rocky headland in Western Cape, South Africa. It is the geographic southern tip of Africa and the beginning of the traditional dividing line between the Atlantic and Indian oceans according to the In ...

) and crossing the width of the Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third-largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, covering or approximately 20% of the water area of Earth#Surface, Earth's surface. It is bounded by Asia to the north, Africa to the west and Australia (continent), ...

, a route 7,000 miles longer. During the outward voyage, Bligh demoted Sailing Master

The master, or sailing master, is a historical rank for a naval Officer (armed forces), officer trained in and responsible for the navigation of a sailing ship, sailing vessel.

In the Royal Navy, the master was originally a warrant officer who ...

John Fryer John Fryer may refer to:

*John Fryer (physician, died 1563), English physician, humanist and early reformer

*John Fryer (physician, died 1672), English physician

*John Fryer (travel writer) (1650–1733), British travel-writer and doctor

*Sir John ...

, replacing him with Fletcher Christian . This act seriously damaged the relationship between Bligh and Fryer, and Fryer later claimed that Bligh's act was entirely personal.

Bligh is commonly portrayed as the epitome of abusive sailing captains, but this portrayal has recently come into dispute. Caroline Alexander points out in her 2003 book ''The Bounty'' that Bligh was relatively lenient compared with other British naval officers. Bligh enjoyed the patronage of Sir Joseph Banks

Sir Joseph Banks, 1st Baronet, (19 June 1820) was an English naturalist, botanist, and patron of the natural sciences.

Banks made his name on the 1766 natural-history expedition to Newfoundland and Labrador. He took part in Captain James Co ...

, a wealthy botanist and influential figure in Britain at the time. That, together with his experience sailing with Cook, familiarity with navigation in the area, and local customs were probably important factors in his appointment.

''Bounty'' reached Tahiti, then called "Otaheite", on 26 October 1788, after ten months at sea. The crew spent five months there collecting and preparing 1,015 breadfruit plants to be transported to the West Indies. Bligh allowed the crew to live ashore and care for the potted breadfruit plants, and they became socialised to the customs and culture of the Tahitians. Many of the seamen and some of the "young gentlemen" had themselves tattooed in native fashion. Master's Mate

Master's mate is an obsolete rating which was used by the British Royal Navy, Royal Navy, United States Navy and merchant services in both countries for a senior petty officer who assisted the sailing master, master. Master's mates evolved into th ...

and Acting Lieutenant Fletcher Christian married Maimiti, a Tahitian woman. Other warrant officers

Warrant officer (WO) is a Military rank, rank or category of ranks in the armed forces of many countries. Depending on the country, service, or historical context, warrant officers are sometimes classified as the most junior of the commissioned ...

and seamen were also said to have formed "connections" with native women.

Mutiny and destruction of the ship

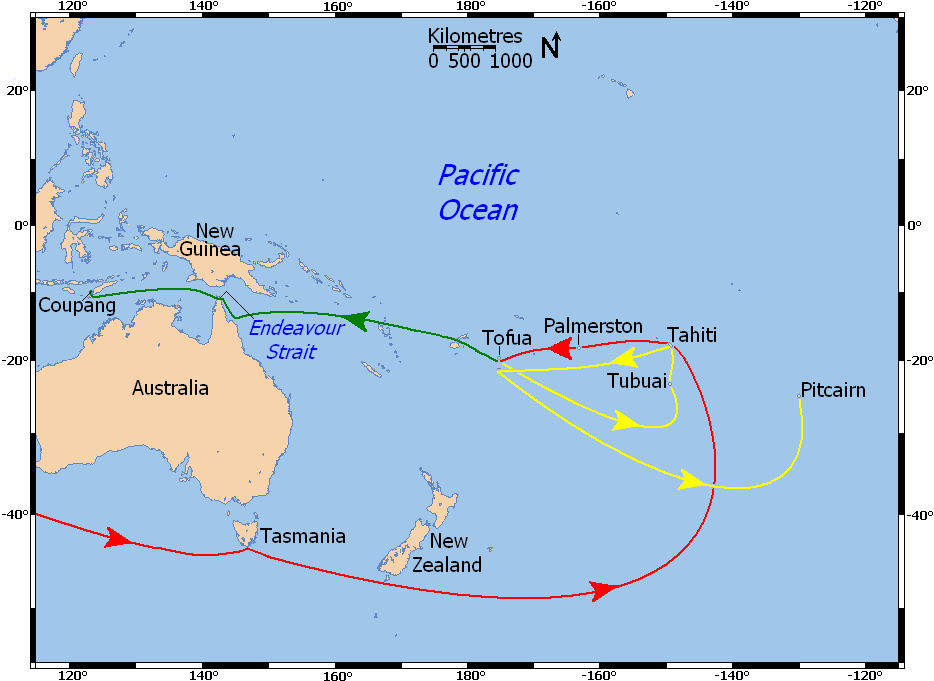

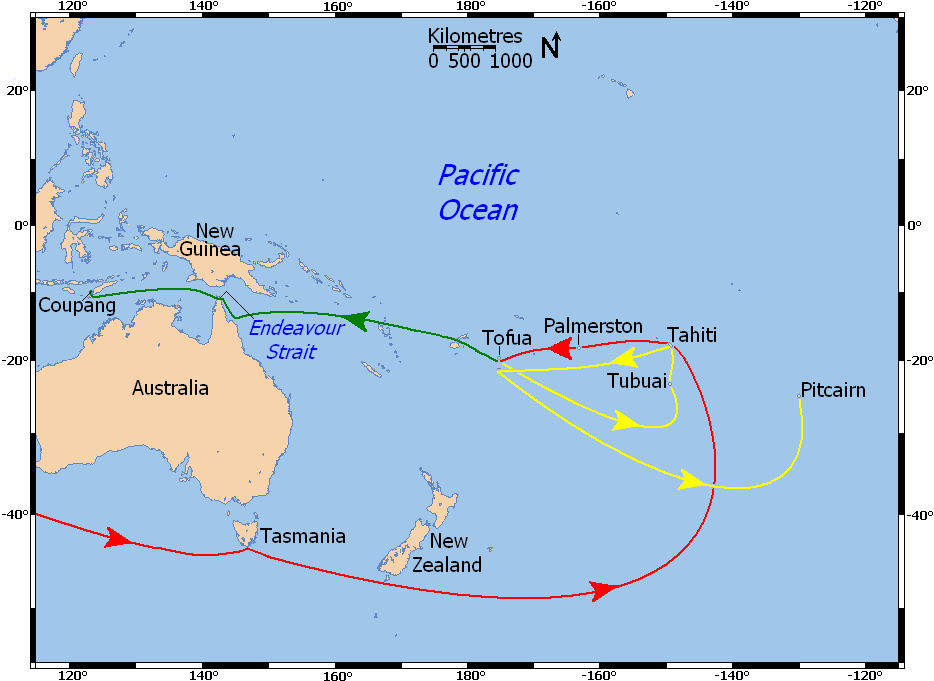

After five months in Tahiti, ''Bounty'' set sail with her breadfruit cargo on 4 April 1789. Some west of Tahiti, near

After five months in Tahiti, ''Bounty'' set sail with her breadfruit cargo on 4 April 1789. Some west of Tahiti, near Tonga

Tonga, officially the Kingdom of Tonga, is an island country in Polynesia, part of Oceania. The country has 171 islands, of which 45 are inhabited. Its total surface area is about , scattered over in the southern Pacific Ocean. accordin ...

, mutiny broke out on 28 April 1789. Despite strong words and threats heard on both sides, the ship was taken bloodlessly and apparently without struggle by any of the loyalists except Bligh himself. Of the 42 men on board aside from Bligh and Christian, 22 joined Christian in mutiny, two were passive, and 18 remained loyal to Bligh.

The mutineers ordered Bligh, two midshipmen, the surgeon's mate (Ledward), and the ship's clerk into the ship's boat. Several more men voluntarily joined Bligh rather than remain aboard. Bligh and his men sailed the open boat to Tofua in search of supplies, but were forced to flee after attacks by hostile natives resulted in the death of one of the men.

Bligh then undertook an arduous journey to the Dutch settlement of Coupang, located over from Tofua. He safely landed there 47 days later, having lost no men during the voyage except the one killed on Tofua.

The mutineers sailed for the island of Tubuai, where they tried to settle. After three months of bloody conflict with the natives, however, they returned to Tahiti. Sixteen of the mutineers – including the four loyalists who had been unable to accompany Bligh – remained there, taking their chances that the Royal Navy would not find them and bring them to justice.

was sent out by the Admiralty in November 1790 in pursuit of ''Bounty'', to capture the mutineers and bring them back to Britain to face a court martial

A court-martial (plural ''courts-martial'' or ''courts martial'', as "martial" is a postpositive adjective) is a military court or a trial conducted in such a court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of members of the mili ...

. She arrived in March 1791 and captured fourteen men within two weeks; they were locked away in a makeshift wooden prison on ''Pandora''s quarterdeck. The men called their cell "Pandora's box". They remained in their prison until 29 August 1791 when ''Pandora'' was wrecked on the Great Barrier Reef

The Great Barrier Reef is the world's largest coral reef system, composed of over 2,900 individual reefs and 900 islands stretching for over over an area of approximately . The reef is located in the Coral Sea, off the coast of Queensland, ...

with the loss of 35 lives, including one loyalist and three mutineers (Stewart, Sumner, Skinner, and Hildebrand).

Immediately after setting the sixteen men ashore in Tahiti in September 1789, Fletcher Christian, eight other crewmen, six Tahitian men, and 11 women, one with a baby, set sail in ''Bounty'' hoping to elude the Royal Navy. According to a journal kept by one of Christian's followers, the Tahitians were actually kidnapped when Christian set sail without warning them, the purpose of this being to acquire the women. The mutineers passed through the Fiji

Fiji, officially the Republic of Fiji, is an island country in Melanesia, part of Oceania in the South Pacific Ocean. It lies about north-northeast of New Zealand. Fiji consists of an archipelago of more than 330 islands—of which about ...

and Cook Islands

The Cook Islands is an island country in Polynesia, part of Oceania in the South Pacific Ocean. It consists of 15 islands whose total land area is approximately . The Cook Islands' Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) covers of ocean. Avarua is its ...

, but feared that they would be found there.

Continuing their quest for a safe haven, on 15 January 1790 they rediscovered Pitcairn Island, which had been misplaced on the Royal Navy's charts. After the decision was made to settle on Pitcairn, livestock and other provisions were removed from ''Bounty''. To prevent the ship's detection, and anyone's possible escape, the ship was burned on 23 January 1790 in what is now called Bounty Bay.

The mutineers remained undetected on Pitcairn until February 1808, when sole remaining mutineer

The mutineers remained undetected on Pitcairn until February 1808, when sole remaining mutineer John Adams

John Adams (October 30, 1735 – July 4, 1826) was a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the second president of the United States from 1797 to 1801. Before Presidency of John Adams, his presidency, he was a leader of ...

and the surviving Tahitian women and their children were discovered by the Boston sealer ''Topaz'', commanded by Captain Mayhew Folger of Nantucket

Nantucket () is an island in the state of Massachusetts in the United States, about south of the Cape Cod peninsula. Together with the small islands of Tuckernuck Island, Tuckernuck and Muskeget Island, Muskeget, it constitutes the Town and Co ...

, Massachusetts

Massachusetts ( ; ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Maine to its east, Connecticut and Rhode ...

. Adams gave to Folger the ''Bounty'' azimuth compass

An azimuth compass (or azimuthal compass) is a nautical instrument used to measure the magnetic azimuth, the angle of the arc on the horizon between the direction of the Sun or some other celestial object and the magnetic north. This can be compar ...

and marine chronometer

A marine chronometer is a precision timepiece that is carried on a ship and employed in the determination of the ship's position by celestial navigation. It is used to determine longitude by comparing Greenwich Mean Time (GMT), and the time at t ...

.

Seventeen years later, in 1825, , on a voyage of exploration under Captain Frederick William Beechey

Rear-Admiral Frederick William Beechey (17 February 1796 – 29 November 1856) was an English naval officer, artist, explorer, hydrographer and writer.

Life and career

He was the son of two painters, Sir William Beechey, RA and his sec ...

, arrived on Christmas Day off Pitcairn and spent 19 days there. Beechey later recorded this in his 1831 published account of the voyage, as did one of his crew, John Bechervaise, in his 1839 ''Thirty-Six Years of a Seafaring Life by an Old Quarter Master''. Beechey wrote a detailed account of the mutiny as recounted to him by the last survivor, Adams. Bechervaise, who described the life of the islanders, says he found the remains of ''Bounty'' and took some pieces of wood from it which were turned into souvenirs such as snuff boxes.

Mission details

The details of the voyage of ''Bounty'' are very well documented, largely due to the effort of Bligh to maintain an accurate log before, during, and after the actual mutiny. ''Bounty''s crew list is also well chronicled.

Bligh's original log remained intact throughout his ordeal and was used as a major piece of evidence in his own trial for the loss of ''Bounty'', as well as the subsequent trial of captured mutineers. The original log is presently maintained at the

The details of the voyage of ''Bounty'' are very well documented, largely due to the effort of Bligh to maintain an accurate log before, during, and after the actual mutiny. ''Bounty''s crew list is also well chronicled.

Bligh's original log remained intact throughout his ordeal and was used as a major piece of evidence in his own trial for the loss of ''Bounty'', as well as the subsequent trial of captured mutineers. The original log is presently maintained at the State Library of New South Wales

The State Library of New South Wales, part of which is known as the Mitchell Library, is a large heritage-listed special collections, reference and research library open to the public and is one of the oldest libraries in Australia. Establis ...

, with available transcripts in both print and electronic format.

Mission log

; 1787 : 16 August: William Bligh is ordered to command a breadfruit gathering expedition to Tahiti : 3 September: ''Bounty'' launched from the drydock atDeptford

Deptford is an area on the south bank of the River Thames in southeast London, in the Royal Borough of Greenwich and London Borough of Lewisham. It is named after a Ford (crossing), ford of the River Ravensbourne. From the mid 16th century ...

: 4–9 October: ''Bounty'' navigated with a partial crew to an ammunition loading station, south of Deptford

: 10–12 October: Onload of arms and weapons at Long Reach

: 15 October – 4 November: Navigated to Spithead

Spithead is an eastern area of the Solent and a roadstead for vessels off Gilkicker Point in Hampshire, England. It is protected from all winds except those from the southeast, with the Isle of Wight lying to the south-west. Spithead and the ch ...

for final crew and stores onload

: 29 November: Made anchor at St Helens, Isle of Wight

: 23 December: Departed English waters for Tahiti

; 1788

: 5–10 January: Anchored off Tenerife

Tenerife ( ; ; formerly spelled ''Teneriffe'') is the largest and most populous island of the Canary Islands, an Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Spain. With a land area of and a population of 965,575 inhabitants as of A ...

, Canary Islands

: 5 February: Crossed equator

The equator is the circle of latitude that divides Earth into the Northern Hemisphere, Northern and Southern Hemisphere, Southern Hemispheres of Earth, hemispheres. It is an imaginary line located at 0 degrees latitude, about in circumferen ...

at 21.50 degrees West

: 26 February: Marked at 100 leagues from the eastern coast of Brazil

Brazil, officially the Federative Republic of Brazil, is the largest country in South America. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by area, fifth-largest country by area and the List of countries and dependencies by population ...

: 23 March: Arrived Tierra del Fuego

Tierra del Fuego (, ; Spanish for "Land of Fire", rarely also Fireland in English) is an archipelago off the southernmost tip of the South America, South American mainland, across the Strait of Magellan.

The archipelago consists of the main is ...

: 9 April: Entered the Strait of Magellan

The Strait of Magellan (), also called the Straits of Magellan, is a navigable sea route in southern Chile separating mainland South America to the north and the Tierra del Fuego archipelago to the south. Considered the most important natura ...

: 25 April: Abandoned attempt to round Cape Horn

Cape Horn (, ) is the southernmost headland of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago of southern Chile, and is located on the small Hornos Island. Although not the most southerly point of South America (which is Águila Islet), Cape Horn marks the nor ...

and turned east

: 22 May: Within sight of the Cape of Good Hope

The Cape of Good Hope ( ) is a rocky headland on the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic coast of the Cape Peninsula in South Africa.

A List of common misconceptions#Geography, common misconception is that the Cape of Good Hope is the southern tip of Afri ...

: 24 May – 29 June: Anchored at Simon's Bay

: 28 July: Within sight of Saint Paul's Island, west of Van Diemen's Land

Van Diemen's Land was the colonial name of the island of Tasmania during the European exploration of Australia, European exploration and colonisation of Australia in the 19th century. The Aboriginal Tasmanians, Aboriginal-inhabited island wa ...

: 20 August – 2 September: Anchored Van Diemen's Land

: 19 September: Past the southern tip of New Zealand

New Zealand () is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and List of islands of New Zealand, over 600 smaller islands. It is the List of isla ...

: 26 October: Arrived Tahiti

: 25 December: Shifted mooring to "Toahroah" harbour, Pare "Oparre", Tahiti. ''Bounty'' ran aground.

; 1789

: 4 April: Weighed anchor from the harbour at Pare, Tahiti

: 23–25 April: Anchored for provisions off Annamooka

Nomuka is a small island in the southern part of the Haʻapai, Haapai group of islands in Tonga. It is part of the Nomuka Group of islands, also called the Otu Muomua. Among neighboring islands are Kelefesia, Nukutula, Tonumea, Fonoifua, Telekit ...

(Tonga

Tonga, officially the Kingdom of Tonga, is an island country in Polynesia, part of Oceania. The country has 171 islands, of which 45 are inhabited. Its total surface area is about , scattered over in the southern Pacific Ocean. accordin ...

)

: 26 April: Departed Annamooka for the West Indies

The West Indies is an island subregion of the Americas, surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea, which comprises 13 independent island country, island countries and 19 dependent territory, dependencies in thr ...

: 28 April: Mutiny – Captain Bligh and loyal crew members set adrift in ''Bounty'' launch

: ''From this point, Bligh's mission log reflects the voyage of the Bounty launch towards the Dutch East Indies

The Dutch East Indies, also known as the Netherlands East Indies (; ), was a Dutch Empire, Dutch colony with territory mostly comprising the modern state of Indonesia, which Proclamation of Indonesian Independence, declared independence on 17 Au ...

''

: 29 April: ''Bounty'' launch arrives at Tofua

: 2 May: ''Bounty'' launch castaways flee Tofua after being attacked by natives

: 28 May: Landfall on a small island north of New Hebrides

New Hebrides, officially the New Hebrides Condominium () and named after the Hebrides in Scotland, was the colonial name for the island group in the South Pacific Ocean that is now Vanuatu. Native people had inhabited the islands for three th ...

. Named "Restoration Island" by Captain Bligh

: 30–31 May: ''Bounty'' launch transits to a second nearby island, named "Sunday Island"

: 1–2 June: ''Bounty'' launch transits 42 miles to a third island, named "Turtle Island"

: 3 June: ''Bounty'' launch sails into the open ocean towards Australia

: 13 June: ''Bounty'' launch lands at Timor

Timor (, , ) is an island at the southern end of Maritime Southeast Asia, in the north of the Timor Sea. The island is Indonesia–Timor-Leste border, divided between the sovereign states of Timor-Leste in the eastern part and Indonesia in the ...

: 14 June: Launch castaways circle Timor and land at Coupang. Mutiny is reported to Dutch authorities

: ''Bligh's mission log from this point reflects his return to England onboard various merchant vessels and sailing ships''

: 20 August – 10 September: Sailed via schooner

A schooner ( ) is a type of sailing ship, sailing vessel defined by its Rig (sailing), rig: fore-and-aft rigged on all of two or more Mast (sailing), masts and, in the case of a two-masted schooner, the foremast generally being shorter than t ...

to Pasuruan

Pasuruan () is a city in East Java Province of Java, Indonesia. It had a population of 186,262 at the 2010 CensusBiro Pusat Statistik, Jakarta, 2011. and 208,006 at the 2020 Census;Badan Pusat Statistik, Jakarta, 2021. the official estimate as at ...

, Java

Java is one of the Greater Sunda Islands in Indonesia. It is bordered by the Indian Ocean to the south and the Java Sea (a part of Pacific Ocean) to the north. With a population of 156.9 million people (including Madura) in mid 2024, proje ...

: 11–12 September: In transit to Surabaya

Surabaya is the capital city of East Java Provinces of Indonesia, province and the List of Indonesian cities by population, second-largest city in Indonesia, after Jakarta. Located on the northeastern corner of Java island, on the Madura Strai ...

: 15–17 September: In transit to the town of Gresik, Madura Strait

Madura Strait is a stretch of water that separates the Indonesian islands of Java and Madura, in the province of East Java. The islands of Kambing, Giliraja, Genteng, and Ketapang lie in the Strait. The Suramadu Bridge, the longest in Indones ...

: 18–22 September: In transit to Semarang

Semarang (Javanese script, Javanese: , ''Kutha Semarang'') is the capital and largest city of Central Java province in Indonesia. It was a major port during the Netherlands, Dutch Dutch East Indies, colonial era, and is still an important regio ...

: 26 September – 1 October: In transit to Batavia (Jakarta

Jakarta (; , Betawi language, Betawi: ''Jakartè''), officially the Special Capital Region of Jakarta (; ''DKI Jakarta'') and formerly known as Batavia, Dutch East Indies, Batavia until 1949, is the capital and largest city of Indonesia and ...

)

: 16 October: Sailed for Europe on board the Dutch packet SS ''Vlydte''

: 16 December: Arrived Cape of Good Hope

; 1790

: 13 January: Sailed from Cape of Good Hope for England

: 13 March: Arrived Portsmouth Harbour

Crew list

In the immediate wake of the mutiny, all but four of the loyal crew joined Bligh in the long boat for the voyage to Timor, and eventually made it safely back to England, unless otherwise noted in the table below. Four were detained against their will on ''Bounty'' for their needed skills and for lack of space on the long boat. The mutineers first returned to Tahiti, where most of the survivors were later captured by ''Pandora'' and taken to England for trial. Nine mutineers continued their flight from the law and eventually settled on Pitcairn Island, where all but one died before their fate became known to the outside world.

In the immediate wake of the mutiny, all but four of the loyal crew joined Bligh in the long boat for the voyage to Timor, and eventually made it safely back to England, unless otherwise noted in the table below. Four were detained against their will on ''Bounty'' for their needed skills and for lack of space on the long boat. The mutineers first returned to Tahiti, where most of the survivors were later captured by ''Pandora'' and taken to England for trial. Nine mutineers continued their flight from the law and eventually settled on Pitcairn Island, where all but one died before their fate became known to the outside world.

Discovery of the wreck

Luis Marden rediscovered the remains of ''Bounty'' in January 1957. After spotting remains of the rudder (which had been found in 1933 by Parkin Christian, and is still displayed in the Fiji Museum in Suva), he persuaded his editors and writers to let him dive off Pitcairn Island, where the rudder had been found. Despite the warnings of one islander"Man, you gwen be dead as a hatchet!"Marden dived for several days in the dangerous swells near the island, and found the remains of the ship: a rudder pin, nails, a ships boat oarlock, fittings and a ''Bounty'' anchor that he raised. He subsequently met withMarlon Brando

Marlon Brando Jr. (April 3, 1924 – July 1, 2004) was an American actor. Widely regarded as one of the greatest cinema actors of the 20th century,''Movies in American History: An Encyclopedia''

to counsel him on his role as Fletcher Christian in the 1962 film ''Mutiny on the Bounty

The mutiny on the ''Bounty'' occurred in the South Pacific Ocean on 28 April 1789. Disaffected crewmen, led by acting-Lieutenant Fletcher Christian, seized control of the ship, , from their captain, Lieutenant (navy), Lieutenant William Bli ...

''. Later in life, Marden wore cuff links made of nails from ''Bounty''. Marden also dived on the wreck of ''Pandora'' and left a ''Bounty'' nail with ''Pandora''.

Some of the ''Bounty''s remains, such as the ballast stones, are still partially visible in the waters of Bounty Bay.

The last of ''Bounty''s four 4-pounder cannon was recovered in 1998 by an archaeological team from James Cook University

James Cook University (JCU) is a public university in North Queensland, Australia. The second oldest university in Queensland, JCU is a teaching and research institution. The university's main campuses are located in the tropical cities of Cair ...

and was sent to the Queensland Museum in Townsville to be stabilised through lengthy conservation treatment via electrolysis

In chemistry and manufacturing, electrolysis is a technique that uses Direct current, direct electric current (DC) to drive an otherwise non-spontaneous chemical reaction. Electrolysis is commercially important as a stage in the separation of c ...

over a period of nearly 40 months. The gun was subsequently returned to Pitcairn Island, where it has been placed on display in a new community hall. Several other pieces of the ship were found but local law forbids removal of such items from the island.

Modern reconstructions

When the 1935 film ''

When the 1935 film ''Mutiny on the Bounty

The mutiny on the ''Bounty'' occurred in the South Pacific Ocean on 28 April 1789. Disaffected crewmen, led by acting-Lieutenant Fletcher Christian, seized control of the ship, , from their captain, Lieutenant (navy), Lieutenant William Bli ...

'' was made, sailing vessels (often with assisting engines) were still common; existing vessels were adapted to act as ''Bounty'' and ''Pandora''. For ''Bounty'', Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios Inc. (also known as Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Pictures, commonly shortened to MGM or MGM Studios) is an American Film production, film and television production and film distribution, distribution company headquartered ...

(MGM) had the wooden 19th century schooner ''Lily

''Lilium'' ( ) is a genus of herbaceous flowering plants growing from bulbs, all with large and often prominent flowers. Lilies are a group of flowering plants which are important in culture and literature in much of the world. Most species are ...

'' transformed into the three masted full square-rigged ''Bounty''. '' Metha Nelson'', which had been featured in movies from 1931 on, was given the role of ''Pandora''.

Both reconstructions, the modern ''Bounty'' and ''Pandora'', sailed from the US west coast to Tahiti for film shoots at the original location. A model ship was built in two parts to serve as a set design in an MGM studio.

For the 1962 film, a new '' Bounty'' was constructed in 1960 in Nova Scotia. For much of 1962 to 2012, she was owned by a not-for-profit organisation whose primary aim was to sail her and other square rigged sailing ships, and she sailed the world to appear at harbours for inspections, and take paying passengers, to recoup running costs. For long voyages, she took on volunteer crew.

On 29 October 2012, sixteen ''Bounty'' crew members abandoned ship off the coast of North Carolina

North Carolina ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, South Carolina to the south, Georgia (U.S. stat ...

after getting caught in the high seas brought on by Hurricane Sandy

Hurricane Sandy (unofficially referred to as Superstorm Sandy) was an extremely large and devastating tropical cyclone which ravaged the Caribbean and the coastal Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region of the United States in late ...

. The ship sank, according to Coast Guard Air Station Elizabeth City, at 12:45 UTC Monday 29 October 2012 and two crew members, including Captain Robin Walbridge, were reported as missing. The captain was not found and presumed dead on 2 November 2012. It was later reported that the Coast Guard had recovered one of the missing crew members, Claudene Christian, descendant of Fletcher Christian of the original ''Bounty''. Christian was found to be unresponsive and pronounced dead on arrival at a hospital in North Carolina.

A second ''Bounty'' replica, named HMAV ''Bounty'', was built in New Zealand in 1979 and used in the 1984 film '' The Bounty''. The hull is constructed of welded steel oversheathed with timber. For many years she served the tourist excursion market from Darling Harbour

Darling Harbour is a harbour and neighborhood adjacent to the city centre of Sydney, New South Wales, Australia, that is made up of a large recreational and pedestrian precinct that is situated on western outskirts of the Sydney central busines ...

, Sydney

Sydney is the capital city of the States and territories of Australia, state of New South Wales and the List of cities in Australia by population, most populous city in Australia. Located on Australia's east coast, the metropolis surrounds Syd ...

, Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country comprising mainland Australia, the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania and list of islands of Australia, numerous smaller isl ...

and appeared in a Tamil language

Tamil (, , , also written as ''Tamizhil'' according to linguistic pronunciation) is a Dravidian language natively spoken by the Tamil people of South Asia. It is one of the longest-surviving classical languages in the world,. "Tamil is one of ...

Indian (1996 film)

''Indian'' is a 1996 Indian Tamil-language vigilante action film directed by S. Shankar, who wrote the script with dialogues by Sujatha, and produced by A. M. Rathnam. The film stars Kamal Haasan in dual roles, alongside Manisha Koirala, ...

, before being sold to HKR International Limited

HKR International Limited (, abbreviated as HKRI) is a conglomerate headquartered in Hong Kong. The company was founded by Cha Chi-ming, a textile industrialist from Shanghai and one of the pioneers of Hong Kong's industrial boom in the 1950-70 ...

in October 2007. She was then a tourist attraction (also used for charter, excursions and sail training) based in Discovery Bay

Discovery Bay is a picturesque residential community located on Lantau Island.

The 2021 census recorded a population of 19,336 residents in DB, with 55% of them being non-Chinese. DB is home to a significant community compared of expatriates ...

, on Lantau Island

Lantau Island (also Lantao Island, Lan Tao or Lan Tau) is the largest island in Hong Kong, located west of Hong Kong Island and the Kowloon Peninsula, and is part of the New Territories. Administratively, most of Lantau Island is part of the ...

in Hong Kong

Hong Kong)., Legally Hong Kong, China in international treaties and organizations. is a special administrative region of China. With 7.5 million residents in a territory, Hong Kong is the fourth most densely populated region in the wor ...

, and was given an additional Chinese name '. She was decommissioned on 1 August 2017.

References

External links

Photo gallery of HMS ''Bounty'' replica at Tall Ships Nova Scotia 2009 and 2012.

{{DEFAULTSORT:Bounty, Hms 1784 ships 1957 archaeological discoveries Full-rigged ships History of the Pitcairn Islands History of the Royal Navy Individual sailing vessels Mutiny on the Bounty Ships built on the Humber Replica ships Maritime incidents in 1790 Maritime folklore Shipwrecks in the Pacific Ocean Colliers