Gentry on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Gentry (from

Gentry (from

Emperor Constantine convoked the First Council of Nicaea in 325 whose Nicene Creed included belief in "one holy catholic and apostolic Church". Emperor Theodosius I made First Council of Nicaea, Nicene Christianity the state church of the Roman Empire with the Edict of Thessalonica of 380.

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century, there emerged no single powerful secular government in the West, but there was a central ecclesiastical power in Rome, the Catholic Church. In this power vacuum, the Church rose to become the dominant power in the Western Roman Empire, West.

In essence, the earliest vision of Christendom was a vision of a Christian theocracy, a government founded upon and upholding Christian values, whose institutions are spread through and over with Christian doctrine. The Catholic Church's peak of authority over all European Christians and their common endeavours of the Christian community—for example, the Crusades, the fight against the Moors in the Iberian Peninsula and against the Ottomans in the Balkans—helped to develop a sense of communal identity against the obstacle of Europe's deep political divisions.

The classical heritage flourished throughout the Middle Ages in both the Byzantine Greek East and Latin West. In Plato's ideal state there are three major classes (producers, auxiliaries and guardians), which was representative of the idea of the "Chariot Allegory, tripartite soul", which is expressive of three functions or capacities of the human soul: "appetites" (or "passions"), "the spirited element" and "reason" the part that must guide the soul to truth. Will Durant made a convincing case that certain prominent features of Plato's The Republic (Plato), ideal community were discernible in the organization, dogma and effectiveness of "the" Medieval Church in Europe:

Emperor Constantine convoked the First Council of Nicaea in 325 whose Nicene Creed included belief in "one holy catholic and apostolic Church". Emperor Theodosius I made First Council of Nicaea, Nicene Christianity the state church of the Roman Empire with the Edict of Thessalonica of 380.

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century, there emerged no single powerful secular government in the West, but there was a central ecclesiastical power in Rome, the Catholic Church. In this power vacuum, the Church rose to become the dominant power in the Western Roman Empire, West.

In essence, the earliest vision of Christendom was a vision of a Christian theocracy, a government founded upon and upholding Christian values, whose institutions are spread through and over with Christian doctrine. The Catholic Church's peak of authority over all European Christians and their common endeavours of the Christian community—for example, the Crusades, the fight against the Moors in the Iberian Peninsula and against the Ottomans in the Balkans—helped to develop a sense of communal identity against the obstacle of Europe's deep political divisions.

The classical heritage flourished throughout the Middle Ages in both the Byzantine Greek East and Latin West. In Plato's ideal state there are three major classes (producers, auxiliaries and guardians), which was representative of the idea of the "Chariot Allegory, tripartite soul", which is expressive of three functions or capacities of the human soul: "appetites" (or "passions"), "the spirited element" and "reason" the part that must guide the soul to truth. Will Durant made a convincing case that certain prominent features of Plato's The Republic (Plato), ideal community were discernible in the organization, dogma and effectiveness of "the" Medieval Church in Europe:

The nobility of a person might be either inherited or earned. Nobility in its most general and strict sense is an acknowledged preeminence that is hereditary: legitimate descendants (or all male descendants, in some societies) of nobles are nobles, unless explicitly stripped of the privilege. The terms ''aristocrat'' and ''aristocracy'' are a less formal means to refer to persons belonging to this social environment, social milieu.

Historically in some cultures, members of an upper class often did not have to work for a living, as they were supported by earned or inherited investments (often real estate), although members of the upper class may have had less actual money than merchants. Upper-class status commonly derived from the social position of one's family and not from one's own achievements or wealth. Much of the population that comprised the upper class consisted of aristocrats, ruling families, Royal and noble ranks, titled people, and religious hierarchs. These people were usually born into their status, and historically, there was not much movement across class boundaries. This is to say that it was much harder for an individual to move up in class simply because of the structure of society.

In many countries, the term ''upper class'' was intimately associated with hereditary land ownership and titles. Political power was often in the hands of the landowners in many pre-industrial societies (which was one of the causes of the French Revolution), despite there being no legal barriers to land ownership for other social classes. Power began to shift from upper-class landed families to the general population in the Early modern Europe, early modern age, leading to marital alliances between the two groups, providing the foundation for the modern upper classes in the West. Upper-class landowners in Europe were often also members of the titled nobility, though not necessarily: the prevalence of titles of nobility varied widely from country to country. Some upper classes were almost entirely untitled, for example, the Szlachta of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

Before the Age of Absolutism (European history), Absolutism, institutions, such as the church, legislatures, or social elites, restrained monarchical power. Absolutism was characterized by the ending of feudal partitioning, consolidation of power with the monarch, rise of state, rise of professional standing armies, professional bureaucracies, the codification of state laws, and the rise of ideologies that justify the absolutist monarchy. Hence, Absolutism was made possible by new innovations and characterized as a phenomenon of Early Modern Europe, rather than that of the Middle Ages, where the clergy and nobility counterbalanced as a result of mutual rivalry.

The nobility of a person might be either inherited or earned. Nobility in its most general and strict sense is an acknowledged preeminence that is hereditary: legitimate descendants (or all male descendants, in some societies) of nobles are nobles, unless explicitly stripped of the privilege. The terms ''aristocrat'' and ''aristocracy'' are a less formal means to refer to persons belonging to this social environment, social milieu.

Historically in some cultures, members of an upper class often did not have to work for a living, as they were supported by earned or inherited investments (often real estate), although members of the upper class may have had less actual money than merchants. Upper-class status commonly derived from the social position of one's family and not from one's own achievements or wealth. Much of the population that comprised the upper class consisted of aristocrats, ruling families, Royal and noble ranks, titled people, and religious hierarchs. These people were usually born into their status, and historically, there was not much movement across class boundaries. This is to say that it was much harder for an individual to move up in class simply because of the structure of society.

In many countries, the term ''upper class'' was intimately associated with hereditary land ownership and titles. Political power was often in the hands of the landowners in many pre-industrial societies (which was one of the causes of the French Revolution), despite there being no legal barriers to land ownership for other social classes. Power began to shift from upper-class landed families to the general population in the Early modern Europe, early modern age, leading to marital alliances between the two groups, providing the foundation for the modern upper classes in the West. Upper-class landowners in Europe were often also members of the titled nobility, though not necessarily: the prevalence of titles of nobility varied widely from country to country. Some upper classes were almost entirely untitled, for example, the Szlachta of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

Before the Age of Absolutism (European history), Absolutism, institutions, such as the church, legislatures, or social elites, restrained monarchical power. Absolutism was characterized by the ending of feudal partitioning, consolidation of power with the monarch, rise of state, rise of professional standing armies, professional bureaucracies, the codification of state laws, and the rise of ideologies that justify the absolutist monarchy. Hence, Absolutism was made possible by new innovations and characterized as a phenomenon of Early Modern Europe, rather than that of the Middle Ages, where the clergy and nobility counterbalanced as a result of mutual rivalry.

The Thirteen Colonies, Colonial American use of ''gentry'' was not common. Historians use it to refer to rich landowners in the South before 1776. Typically large scale landowners rented out farms to white tenant farmers. North of Maryland, there were few large comparable rural estates, except in the Dutch domains in the Hudson Valley of New York.

The Thirteen Colonies, Colonial American use of ''gentry'' was not common. Historians use it to refer to rich landowners in the South before 1776. Typically large scale landowners rented out farms to white tenant farmers. North of Maryland, there were few large comparable rural estates, except in the Dutch domains in the Hudson Valley of New York.

There were two leading classes, i.e. the gentry, in the time of feudal Japan: the ''daimyō'' and the ''samurai''. The Confucian ideals in the Japanese culture emphasised the importance of productive members of society, so farmers and fishermen were considered of a higher status than merchants.

Emperor Meiji abolished the samurai's right to be the only armed force in favor of a more modern, Western-style, conscripted army in 1873. Samurai became ''Shizoku'' (), but the right to wear a katana in public was eventually abolished along with the right to execution, execute commoners who paid them disrespect.

In defining how a modern Japan should be, members of the Meiji government decided to follow in the footsteps of the United Kingdom and Germany, basing the country on the concept of ''noblesse oblige''. Samurai were not to be a political force under the new order. The difference between the Japanese and European feudal systems was that European feudalism was grounded in Roman law, Roman legal structure, while Japan feudalism had Chinese Confucianism, Confucian morality as its basis.

There were two leading classes, i.e. the gentry, in the time of feudal Japan: the ''daimyō'' and the ''samurai''. The Confucian ideals in the Japanese culture emphasised the importance of productive members of society, so farmers and fishermen were considered of a higher status than merchants.

Emperor Meiji abolished the samurai's right to be the only armed force in favor of a more modern, Western-style, conscripted army in 1873. Samurai became ''Shizoku'' (), but the right to wear a katana in public was eventually abolished along with the right to execution, execute commoners who paid them disrespect.

In defining how a modern Japan should be, members of the Meiji government decided to follow in the footsteps of the United Kingdom and Germany, basing the country on the concept of ''noblesse oblige''. Samurai were not to be a political force under the new order. The difference between the Japanese and European feudal systems was that European feudalism was grounded in Roman law, Roman legal structure, while Japan feudalism had Chinese Confucianism, Confucian morality as its basis.

''Chivalry'' is a term related to the medieval institution of knighthood. It is usually associated with ideals of knightly virtues, honour and courtly love.

Christianity had a modifying influence on the virtues of chivalry, with limits placed on knights to protect and honour the weaker members of society and maintain peace. The church became more tolerant of war in the defence of faith, espousing theories of the just war. In the 11th century, the concept of a "knight of Christ" (''miles Christi'') gained currency in France, Spain and Italy.. These concepts of "religious chivalry" were further elaborated in the era of the Crusades.

In the later Middle Ages, wealthy merchants strove to adopt chivalric attitudes. This was a democratisation of chivalry, leading to a new genre called the courtesy book, which were guides to the behaviour of "gentlemen".

When examining mediaeval literature, medieval literature, chivalry can be classified into three basic but overlapping areas:

# Duties to countrymen and fellow Christians

# Duties to God

# Duties to women

These three areas obviously overlap quite frequently in chivalry and are often indistinguishable. Another classification of chivalry divides it into warrior, religious and courtly love strands. One particular similarity between all three of these categories is honour. Honour is the foundational and guiding principle of chivalry. Thus, for the knight, honour would be one of the guides of action.

''Chivalry'' is a term related to the medieval institution of knighthood. It is usually associated with ideals of knightly virtues, honour and courtly love.

Christianity had a modifying influence on the virtues of chivalry, with limits placed on knights to protect and honour the weaker members of society and maintain peace. The church became more tolerant of war in the defence of faith, espousing theories of the just war. In the 11th century, the concept of a "knight of Christ" (''miles Christi'') gained currency in France, Spain and Italy.. These concepts of "religious chivalry" were further elaborated in the era of the Crusades.

In the later Middle Ages, wealthy merchants strove to adopt chivalric attitudes. This was a democratisation of chivalry, leading to a new genre called the courtesy book, which were guides to the behaviour of "gentlemen".

When examining mediaeval literature, medieval literature, chivalry can be classified into three basic but overlapping areas:

# Duties to countrymen and fellow Christians

# Duties to God

# Duties to women

These three areas obviously overlap quite frequently in chivalry and are often indistinguishable. Another classification of chivalry divides it into warrior, religious and courtly love strands. One particular similarity between all three of these categories is honour. Honour is the foundational and guiding principle of chivalry. Thus, for the knight, honour would be one of the guides of action.

The term gentleman (from Latin ''gentilis'', belonging to a race or ''gens'', and "man", cognate with the French word ''gentilhomme'', the Spanish ''gentilhombre'' and the Italian ''gentil uomo'' or ''gentiluomo''), in its original and strict signification, denoted a man of good family, analogous to the Latin ''generosus'' (its invariable translation in English-Latin documents). In this sense the word equates with the French ''gentilhomme'' ("nobleman"), which was in Great Britain long confined to the peerage. The term ''gentry'' (from the Old French ''genterise'' for ''gentelise'') has much of the social-class significance of the French ''noblesse'' or of the German ''Adel'', but without the strict technical requirements of those traditions (such as quarters of nobility). To a degree, ''gentleman'' signified a man with an income derived from landed property, a old money, legacy or some other source and was thus independently wealthy and did not need to work.

The term gentleman (from Latin ''gentilis'', belonging to a race or ''gens'', and "man", cognate with the French word ''gentilhomme'', the Spanish ''gentilhombre'' and the Italian ''gentil uomo'' or ''gentiluomo''), in its original and strict signification, denoted a man of good family, analogous to the Latin ''generosus'' (its invariable translation in English-Latin documents). In this sense the word equates with the French ''gentilhomme'' ("nobleman"), which was in Great Britain long confined to the peerage. The term ''gentry'' (from the Old French ''genterise'' for ''gentelise'') has much of the social-class significance of the French ''noblesse'' or of the German ''Adel'', but without the strict technical requirements of those traditions (such as quarters of nobility). To a degree, ''gentleman'' signified a man with an income derived from landed property, a old money, legacy or some other source and was thus independently wealthy and did not need to work.

A coat of arms is a heraldic device dating to the 12th century in Europe. It was originally a cloth tunic worn over or in place of armour to establish identity in battle.. The coat of arms is drawn with heraldic rules for a person, family or organisation. Family coats of arms were originally derived from personal ones, which then became extended in time to the whole family. In Scotland, family coats of arms are still personal ones and are mainly used by the head of the family. In heraldry, a person entitled to a coat of arms is an armiger, and their family would be armigerous.

A coat of arms is a heraldic device dating to the 12th century in Europe. It was originally a cloth tunic worn over or in place of armour to establish identity in battle.. The coat of arms is drawn with heraldic rules for a person, family or organisation. Family coats of arms were originally derived from personal ones, which then became extended in time to the whole family. In Scotland, family coats of arms are still personal ones and are mainly used by the head of the family. In heraldry, a person entitled to a coat of arms is an armiger, and their family would be armigerous.

online

* Heal, Felicity. ''The gentry in England and Wales, 1500–1700'' (1994

online

* Mingay, Gordon E. ''The Gentry: The Rise and Fall of a Ruling Class'' (1976

online

* O'Hart, John. ''The Irish And Anglo-Irish Landed Gentry, When Cromwell Came to Ireland: or, a Supplement to Irish Pedigrees'' (2 vols) (reprinted 2007) * Sayer, M. J. ''English Nobility: The Gentry, the Heralds and the Continental Context'' (Norwich, 1979) * Wallis, Patrick, and Cliff Webb. "The education and training of gentry sons in early modern England." ''Social History'' 36.1 (2011): 36–53

online

online

* Lieven, Dominic C.B. ''The aristocracy in Europe, 1815–1914'' (Macmillan, 1992). * Wallerstein, Immanuel. ''The modern world-system I: Capitalist agriculture and the origins of the European world-economy in the sixteenth century. Vol. 1'' (Univ of California Press, 2011). * Wasson, Ellis. ''Aristocracy and the modern world'' (Macmillan International Higher Education, 2006), for 19th and 20th centuries

online

* Tawney, R. H. "The rise of the gentry, 1558–1640." ''Economic History Review'' 11.1 (1941): 1–38

online

launched a historiographical debate * Tawney, R. H. "The rise of the gentry: a postscript." ''Economic History Review'' 7.1 (1954): 91–97

online

online

* Chuzo, Ichiko; "The role of the gentry: an hypothesis." in ''China in Revolution: The First Phase, 1900–1913'' ed. by Mary C. Wright (1968) pp: 297–317. * Miller, Harry. ''State versus Gentry in Late Ming Dynasty China, 1572–1644'' (Springer, 2008).

Gentry (from

Gentry (from Old French

Old French (, , ; Modern French: ) was the language spoken in most of the northern half of France from approximately the 8th to the 14th centuries. Rather than a unified language, Old French was a linkage of Romance dialects, mutually intelligib ...

''genterie'', from ''gentil'', "high-born, noble") are "well-born, genteel and well-bred people" of high social class

A social class is a grouping of people into a set of Dominance hierarchy, hierarchical social categories, the most common being the Upper class, upper, Middle class, middle and Working class, lower classes. Membership in a social class can for ...

, especially in the past.

Word similar to gentle imple and decentfamilies

''Gentry'', in its widest connotation, refers to people of good social position connected to landed estate

In real estate, a landed property or landed estate is a property that generates income for the owner (typically a member of the gentry) without the owner having to do the actual work of the estate.

In medieval Western Europe, there were two compet ...

s (see manorialism

Manorialism, also known as the manor system or manorial system, was the method of land ownership (or "tenure") in parts of Europe, notably France and later England, during the Middle Ages. Its defining features included a large, sometimes forti ...

), upper levels of the clergy

Clergy are formal leaders within established religions. Their roles and functions vary in different religious traditions, but usually involve presiding over specific rituals and teaching their religion's doctrines and practices. Some of the ter ...

, and "gentle" families of long descent who in some cases never obtained the official right to bear a coat of arms

A coat of arms is a heraldry, heraldic communication design, visual design on an escutcheon (heraldry), escutcheon (i.e., shield), surcoat, or tabard (the latter two being outer garments). The coat of arms on an escutcheon forms the central ele ...

. The gentry largely consisted of landowners who could live entirely from rental income, or at least had a country estate

An estate is a large parcel of land under single ownership, which would historically generate income for its owner.

British context

In the UK, historically an estate comprises the houses, outbuildings, supporting farmland, and woods that s ...

; some were gentleman farmers. In the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

, the term ''gentry'' refers to the landed gentry

The landed gentry, or the ''gentry'', is a largely historical British social class of landowners who could live entirely from rental income, or at least had a country estate. While distinct from, and socially below, the British peerage, th ...

: the majority of the land-owning social class who typically had a coat of arms, but did not have a peerage

A peerage is a legal system historically comprising various hereditary titles (and sometimes non-hereditary titles) in a number of countries, and composed of assorted noble ranks.

Peerages include:

Australia

* Australian peers

Belgium

* Belgi ...

. The adjective "patrician

Patrician may refer to:

* Patrician (ancient Rome), the original aristocratic families of ancient Rome, and a synonym for "aristocratic" in modern English usage

* Patrician (post-Roman Europe), the governing elites of cities in parts of medieval ...

" ("of or like a person of high social rank") describes in comparison other analogous traditional social elite strata based in cities, such as free cities of Italy (Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 ...

and Genoa

Genoa ( ; it, Genova ; lij, Zêna ). is the capital of the Italian region of Liguria and the List of cities in Italy, sixth-largest city in Italy. In 2015, 594,733 people lived within the city's administrative limits. As of the 2011 Italian ce ...

), and the free imperial cities

In the Holy Roman Empire, the collective term free and imperial cities (german: Freie und Reichsstädte), briefly worded free imperial city (', la, urbs imperialis libera), was used from the fifteenth century to denote a self-ruling city that ...

of Germany, Switzerland, and the Hanseatic League

The Hanseatic League (; gml, Hanse, , ; german: label=Modern German, Deutsche Hanse) was a medieval commercial and defensive confederation of merchant guilds and market towns in Central and Northern Europe. Growing from a few North German to ...

.

The term "gentry" by itself, so Peter Coss

Peter R. Coss is a British historian, specialising in the history of the English medieval gentry. He is Emeritus Professor of Medieval History at the School of History, Archaeology, and Religion at Cardiff University, Wales. His research interests ...

argues, is a construct that historians have applied loosely to rather different societies. Any particular model may not fit a specific society, yet a single definition nevertheless remains desirable.

Historical background of social stratification in the West

The Indo-Europeans who settledEurope

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

, Central

Central is an adjective usually referring to being in the center of some place or (mathematical) object.

Central may also refer to:

Directions and generalised locations

* Central Africa, a region in the centre of Africa continent, also known as ...

and Western Asia

Western Asia, West Asia, or Southwest Asia, is the westernmost subregion of the larger geographical region of Asia, as defined by some academics, UN bodies and other institutions. It is almost entirely a part of the Middle East, and includes Ana ...

and the Indian subcontinent

The Indian subcontinent is a list of the physiographic regions of the world, physiographical region in United Nations geoscheme for Asia#Southern Asia, Southern Asia. It is situated on the Indian Plate, projecting southwards into the Indian O ...

conceived their societies to be ordered (not divided) in a tripartite fashion, the three parts being castes. Castes came to be further divided, perhaps as a result of greater specialisation.

The "classic" formulation of the caste system as largely described by Georges Dumézil was that of a priestly or religiously occupied caste, a warrior caste, and a worker caste. Dumézil divided the Proto-Indo-Europeans

The Proto-Indo-Europeans are a hypothetical prehistoric population of Eurasia who spoke Proto-Indo-European (PIE), the ancestor of the Indo-European languages according to linguistic reconstruction.

Knowledge of them comes chiefly from t ...

into three categories: sovereignty

Sovereignty is the defining authority within individual consciousness, social construct, or territory. Sovereignty entails hierarchy within the state, as well as external autonomy for states. In any state, sovereignty is assigned to the perso ...

, military

A military, also known collectively as armed forces, is a heavily armed, highly organized force primarily intended for warfare. It is typically authorized and maintained by a sovereign state, with its members identifiable by their distinct ...

, and productivity (see Trifunctional hypothesis

The trifunctional hypothesis of prehistoric Proto-Indo-European society postulates a tripartite ideology ("''idéologie tripartite''") reflected in the existence of three classes or castes— priests, warriors, and commoners (farmers or trades ...

). He further subdivided sovereignty

Sovereignty is the defining authority within individual consciousness, social construct, or territory. Sovereignty entails hierarchy within the state, as well as external autonomy for states. In any state, sovereignty is assigned to the perso ...

into two distinct and complementary sub-parts. One part was formal, juridical, and priestly, but rooted in this world. The other was powerful, unpredictable, and also priestly, but rooted in the "other", the supernatural and spiritual world. The second main division was connected with the use of force, the military

A military, also known collectively as armed forces, is a heavily armed, highly organized force primarily intended for warfare. It is typically authorized and maintained by a sovereign state, with its members identifiable by their distinct ...

, and war. Finally, there was a third group, ruled by the other two, whose role was productivity: herding, farming, and crafts

A craft or trade is a pastime or an occupation that requires particular skills and knowledge of skilled work. In a historical sense, particularly the Middle Ages and earlier, the term is usually applied to people occupied in small scale prod ...

.

This system of caste roles can be seen in the castes which flourished on the Indian subcontinent and amongst the Italic peoples

The Italic peoples were an ethnolinguistic group identified by their use of Italic languages, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

The Italic peoples are descended from the Indo-European speaking peoples who inhabited Italy from at leas ...

.

Examples of the Indo-European castes:

* Indo-Iranian – Brahmin/Athravan, Kshatriyas/Rathaestar, Vaishyas

* Celtic – Druids, Equites, Plebs, Plebes (according to Julius Caesar)

* Anglo-Saxon – Gebedmen (prayer-men), Fyrdmen (army-men), Weorcmen (workmen) (according to Alfred the Great)

* Slavic – Volkhv, Volkhvs, Voin, Krestyanin/Smerd

* Nordic – Earl, Churl, Thrall (according to the Poetic Edda, Lay of Rig)

* Greece (Attica) – Eupatridae, Geomori (Athens), Geomori, Demiourgoi

* Greece (Sparta) – Spartiate, Homoioi, Perioeci, Helots

Kings were born out of the warrior or noble class.

Medieval Christendom

Emperor Constantine convoked the First Council of Nicaea in 325 whose Nicene Creed included belief in "one holy catholic and apostolic Church". Emperor Theodosius I made First Council of Nicaea, Nicene Christianity the state church of the Roman Empire with the Edict of Thessalonica of 380.

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century, there emerged no single powerful secular government in the West, but there was a central ecclesiastical power in Rome, the Catholic Church. In this power vacuum, the Church rose to become the dominant power in the Western Roman Empire, West.

In essence, the earliest vision of Christendom was a vision of a Christian theocracy, a government founded upon and upholding Christian values, whose institutions are spread through and over with Christian doctrine. The Catholic Church's peak of authority over all European Christians and their common endeavours of the Christian community—for example, the Crusades, the fight against the Moors in the Iberian Peninsula and against the Ottomans in the Balkans—helped to develop a sense of communal identity against the obstacle of Europe's deep political divisions.

The classical heritage flourished throughout the Middle Ages in both the Byzantine Greek East and Latin West. In Plato's ideal state there are three major classes (producers, auxiliaries and guardians), which was representative of the idea of the "Chariot Allegory, tripartite soul", which is expressive of three functions or capacities of the human soul: "appetites" (or "passions"), "the spirited element" and "reason" the part that must guide the soul to truth. Will Durant made a convincing case that certain prominent features of Plato's The Republic (Plato), ideal community were discernible in the organization, dogma and effectiveness of "the" Medieval Church in Europe:

Emperor Constantine convoked the First Council of Nicaea in 325 whose Nicene Creed included belief in "one holy catholic and apostolic Church". Emperor Theodosius I made First Council of Nicaea, Nicene Christianity the state church of the Roman Empire with the Edict of Thessalonica of 380.

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century, there emerged no single powerful secular government in the West, but there was a central ecclesiastical power in Rome, the Catholic Church. In this power vacuum, the Church rose to become the dominant power in the Western Roman Empire, West.

In essence, the earliest vision of Christendom was a vision of a Christian theocracy, a government founded upon and upholding Christian values, whose institutions are spread through and over with Christian doctrine. The Catholic Church's peak of authority over all European Christians and their common endeavours of the Christian community—for example, the Crusades, the fight against the Moors in the Iberian Peninsula and against the Ottomans in the Balkans—helped to develop a sense of communal identity against the obstacle of Europe's deep political divisions.

The classical heritage flourished throughout the Middle Ages in both the Byzantine Greek East and Latin West. In Plato's ideal state there are three major classes (producers, auxiliaries and guardians), which was representative of the idea of the "Chariot Allegory, tripartite soul", which is expressive of three functions or capacities of the human soul: "appetites" (or "passions"), "the spirited element" and "reason" the part that must guide the soul to truth. Will Durant made a convincing case that certain prominent features of Plato's The Republic (Plato), ideal community were discernible in the organization, dogma and effectiveness of "the" Medieval Church in Europe:

For a thousand years Europe was ruled by an order of guardians considerably like that which was visioned by our philosopher. During the Middle Ages it was customary to classify the population of Christendom into laboratores (workers), bellatores (soldiers), and oratores (clergy). The last group, though small in number, monopolized the instruments and opportunities of culture, and ruled with almost unlimited sway half of the most powerful continent on the globe. The clergy, like Plato's guardians, were placed in authority ... by their talent as shown in ecclesiastical studies and administration, by their disposition to a life of meditation and simplicity, and ... by the influence of their relatives with the powers of state and church. In the latter half of the period in which they ruled [800 CE onwards], the clergy were as free from family cares as even Plato could desire [for such guardians] ... [Clerical] Celibacy was part of the psychological structure of the power of the clergy; for on the one hand they were unimpeded by the narrowing egoism of the family, and on the other their apparent superiority to the call of the flesh added to the awe in which lay sinners held them. ...Gaetano Mosca wrote on the same subject matter in his book The Ruling Class concerning the Medieval Church and its structure that Beyond the fact that Clerical celibacy functioned as a spiritual discipline it also was guarantor of the independence of the Church.

the Catholic Church has always aspired to a preponderant share in political power, it has never been able to monopolize it entirely, because of two traits, chiefly, that are basic in its structure. Celibacy has generally been required of the clergy and of monks. Therefore no real dynasties of abbots and bishops have ever been able to establish themselves. ... Secondly, in spite of numerous examples to the contrary supplied by the warlike Middle Ages, the ecclesiastical calling has by its very nature never been strictly compatible with the bearing of arms. The precept that exhorts the Church to abhor bloodshed has never dropped completely out of sight, and in relatively tranquil and orderly times it has always been very much to the fore.

Two principal estates of the realm

The fundamental social structure in Europe in the Middle Ages was between the Hierarchy of the Catholic Church, ecclesiastical hierarchy, nobles i.e. the tenants in chivalry (counts, barons, knights, esquires, franklin (class), franklins) and the ignobles, the Serfdom#Villeins, villeins, citizens, and Burgess (title), burgesses. The division of society into classes of nobles and ignobles, in the smaller regions of medieval Europe was inexact. After the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, social intermingling between the noble class and the hereditary clerical upper class became a feature in the monarchies of Nordic countries. The gentility is primarily formed on the bases of the medieval societies' two higher estates of the realm, nobility andclergy

Clergy are formal leaders within established religions. Their roles and functions vary in different religious traditions, but usually involve presiding over specific rituals and teaching their religion's doctrines and practices. Some of the ter ...

, both exempted from taxation. Subsequent "gentle" families of long descent who never obtained official rights to bear a coat of arms were also admitted to the rural upper-class society: the gentry.

The three estates

The widespread three estates order was particularly characteristic of France:

* First estate included the group of all clergy, that is, members of the higher clergy and the lower clergy.

* Second estate has been encapsulated by the nobility. Here too, it did not matter whether they came from a lower or higher nobility or if they were impoverished members.

* Third estate included all nominally free citizens; in some places, free peasants.

At the top of the pyramid were the princes and estates of the king or emperor, or with the clergy, the bishops and the pope.

The feudal system was, for the people of the Middle Ages and early modern period, fitted into a God-given order. The nobility and the third estate were born into their class, and change in social position was slow. Wealth had little influence on what estate one belonged to. The exception was the Medieval Church, which was the only institution where competent men (and women) of merit could reach, in one lifetime, the highest positions in society.

The first estate comprised the entire clergy, traditionally divided into "higher" and "lower" clergy. Although there was no formal demarcation between the two categories, the upper clergy were, effectively, clerical nobility, from the families of the second estate or as in the case of Cardinal Wolsey, from more humble backgrounds.

The second estate was the nobility. Being wealthy or influential did not automatically make one a noble, and not all nobles were wealthy and influential (aristocratic families have lost their fortunes in various ways, and the concept of the "poor nobleman" is almost as old as nobility itself). Countries without a feudal tradition did not have a nobility as such.

The nobility of a person might be either inherited or earned. Nobility in its most general and strict sense is an acknowledged preeminence that is hereditary: legitimate descendants (or all male descendants, in some societies) of nobles are nobles, unless explicitly stripped of the privilege. The terms ''aristocrat'' and ''aristocracy'' are a less formal means to refer to persons belonging to this social environment, social milieu.

Historically in some cultures, members of an upper class often did not have to work for a living, as they were supported by earned or inherited investments (often real estate), although members of the upper class may have had less actual money than merchants. Upper-class status commonly derived from the social position of one's family and not from one's own achievements or wealth. Much of the population that comprised the upper class consisted of aristocrats, ruling families, Royal and noble ranks, titled people, and religious hierarchs. These people were usually born into their status, and historically, there was not much movement across class boundaries. This is to say that it was much harder for an individual to move up in class simply because of the structure of society.

In many countries, the term ''upper class'' was intimately associated with hereditary land ownership and titles. Political power was often in the hands of the landowners in many pre-industrial societies (which was one of the causes of the French Revolution), despite there being no legal barriers to land ownership for other social classes. Power began to shift from upper-class landed families to the general population in the Early modern Europe, early modern age, leading to marital alliances between the two groups, providing the foundation for the modern upper classes in the West. Upper-class landowners in Europe were often also members of the titled nobility, though not necessarily: the prevalence of titles of nobility varied widely from country to country. Some upper classes were almost entirely untitled, for example, the Szlachta of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

Before the Age of Absolutism (European history), Absolutism, institutions, such as the church, legislatures, or social elites, restrained monarchical power. Absolutism was characterized by the ending of feudal partitioning, consolidation of power with the monarch, rise of state, rise of professional standing armies, professional bureaucracies, the codification of state laws, and the rise of ideologies that justify the absolutist monarchy. Hence, Absolutism was made possible by new innovations and characterized as a phenomenon of Early Modern Europe, rather than that of the Middle Ages, where the clergy and nobility counterbalanced as a result of mutual rivalry.

The nobility of a person might be either inherited or earned. Nobility in its most general and strict sense is an acknowledged preeminence that is hereditary: legitimate descendants (or all male descendants, in some societies) of nobles are nobles, unless explicitly stripped of the privilege. The terms ''aristocrat'' and ''aristocracy'' are a less formal means to refer to persons belonging to this social environment, social milieu.

Historically in some cultures, members of an upper class often did not have to work for a living, as they were supported by earned or inherited investments (often real estate), although members of the upper class may have had less actual money than merchants. Upper-class status commonly derived from the social position of one's family and not from one's own achievements or wealth. Much of the population that comprised the upper class consisted of aristocrats, ruling families, Royal and noble ranks, titled people, and religious hierarchs. These people were usually born into their status, and historically, there was not much movement across class boundaries. This is to say that it was much harder for an individual to move up in class simply because of the structure of society.

In many countries, the term ''upper class'' was intimately associated with hereditary land ownership and titles. Political power was often in the hands of the landowners in many pre-industrial societies (which was one of the causes of the French Revolution), despite there being no legal barriers to land ownership for other social classes. Power began to shift from upper-class landed families to the general population in the Early modern Europe, early modern age, leading to marital alliances between the two groups, providing the foundation for the modern upper classes in the West. Upper-class landowners in Europe were often also members of the titled nobility, though not necessarily: the prevalence of titles of nobility varied widely from country to country. Some upper classes were almost entirely untitled, for example, the Szlachta of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

Before the Age of Absolutism (European history), Absolutism, institutions, such as the church, legislatures, or social elites, restrained monarchical power. Absolutism was characterized by the ending of feudal partitioning, consolidation of power with the monarch, rise of state, rise of professional standing armies, professional bureaucracies, the codification of state laws, and the rise of ideologies that justify the absolutist monarchy. Hence, Absolutism was made possible by new innovations and characterized as a phenomenon of Early Modern Europe, rather than that of the Middle Ages, where the clergy and nobility counterbalanced as a result of mutual rivalry.

Gentries

Continental Europe

Baltic

From the middle of the 1860s the privileged position of Baltic Germans in the Russian Empire began to waver. Already during the reign of Nicholas I of Russia, Nicholas I (1825–55), who was under pressure from Russian nationalists, some sporadic steps had been taken towards the russification of the provinces. Later, the Baltic Germans faced fierce attacks from the Russian nationalist press, which accused the Baltic aristocracy of separatism, and advocated closer linguistic and administrative integration with Russia. Social division was based on the dominance of the Baltic Germans which formed the upper classes while the majority of indigenous population, called "Undeutsch", composed the peasantry. In the Imperial census of 1897, 98,573 Germans (7.58% of total population) lived in the Governorate of Livonia, 51,017 (7.57%) in the Governorate of Curonia, and 16,037 (3.89%) in the Governorate of Estonia. The social changes faced by the emancipation, both social and national, of the Estonians and Latvians where not taken seriously by the Baltic German gentry. The provisional government of Russia after 1917 revolution gave the Estonians and Latvians self-governance which meant the end of the Baltic German era in Baltics. The Lithuanian gentry consisted mainly of Lithuanians, but due to strong ties to Poland, had been culturally Polonized. After the Union of Lublin in 1569, they became less distinguishable from Polish ''szlachta'', although preserved Lithuanian national awareness.Kingdom of Hungary

In Kingdom of Hungary (1867–1918), Hungary during the late 19th and early 20th century gentry (sometimes spelled as ''dzsentri'') were nobility without land who often sought employment as civil servants, army officers, or went into politics.Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

In the history of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, "gentry" is often used in English to describe the Polish landed gentry ( pl, ziemiaństwo, ziemianie, from ''ziemia'', "land"). They were the lesser members of the nobility (the ''szlachta''), contrasting with the much smaller but more powerful group of "magnate" families (sing. ''magnat'', plural ''magnaci'' in Polish), the Magnates of Poland and Lithuania. Compared to the situation in England and some other parts of Europe, these two parts of the overall "nobility" to a large extent operated as different classes, and were often in conflict. After the Partitions of Poland, at least in the stereotypes of 19th-century nationalist lore, the magnates often made themselves at home in the capitals and courts of the partitioning powers, while the gentry remained on their estates, keeping the national culture alive. From the 15th century, only the ''szlachta'', and a few patrician bughers from some cities, were allowed to own rural estates of any size, as part of the very extensive szlachta privileges. These restrictions were reduced or removed after the Partitions of Poland, and commoner landowners began to emerge. By the 19th century, there were at least 60,000 ''szlachta'' families, most rather poor, and many no longer owning land. By then the "gentry" included many non-noble landowners.Spain and Portugal

In Spanish nobility and former Portuguese nobility, see Hidalgo (nobility), hidalgos and infanzones.Swedish

In Sweden, there was not outright serfdom. Hence, the gentry was a class of well-off citizens that had grown from the wealthier or more powerful members of the peasantry. The two historically legally privileged Social class, classes in Sweden were the Swedish nobility ''(Swedish nobility, Adeln)'', a rather small group numerically, and theclergy

Clergy are formal leaders within established religions. Their roles and functions vary in different religious traditions, but usually involve presiding over specific rituals and teaching their religion's doctrines and practices. Some of the ter ...

, which were part of the so-called ''frälse'' (a classification defined by tax exemptions and representation in the Diet (assembly), diet).

At the head of the Swedish clergy stood the Archbishop of Uppsala since 1164. The clergy encompassed almost all the educated men of the day and furthermore was strengthened by considerable wealth, and thus it came naturally to play a significant political role. Until the Reformation, the clergy was the first estate but was relegated to the secular estate in the Protestant North Europe.

In the Middle Ages, celibacy in the Catholic Church had been a natural barrier to the formation of an hereditary priestly class. After compulsory celibacy was abolished in Sweden during the Protestant Reformation, Reformation, the formation of a hereditary priestly class became possible, whereby wealth and clerical positions were frequently inheritable. Hence the bishops and the vicars, who formed the clerical upper class, would frequently have Manorialism, manors similar to those of other country gentry. Hence continued the medieval Church legacy of the intermingling between noble class and clerical upper class and the intermarriage as the distinctive element in several Nordic countries after the Reformation.

Swedish name#Surnames amongst the Swedish gentry, Surnames in Sweden can be traced to the 15th century, when they were first used by the Gentry (Frälse), i.e., priests and nobles. The names of these were usually in Swedish, Latin, German or Greek.

The adoption of Latin names was first used by the Catholic clergy in the 15th century. The given name was preceded by Herr (Sir), such as Herr Lars, Herr Olof, Herr Hans, followed by a Latinized form of patronymic names, e.g., Lars Petersson Latinized as Laurentius Petri. Starting from the time of the Reformation, the Latinized form of their birthplace (Laurentius Petri Gothus, from Östergötland) became a common naming practice for the clergy.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, the surname was only rarely the original family name of the ennobled; usually, a more imposing new name was chosen. This was a period which produced a myriad of two-word Swedish-language family names for the nobility (very favored prefixes were Adler, "eagle"; Ehren – "ära", "honor"; Silfver, "silver"; and Gyllen, "golden"). The regular difference with Britain was that it became the new surname of the whole house, and the old surname was dropped altogether.

Ukraine

The Western Ukrainian Clergy of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church were a hereditary tight-knit social caste that dominated western Ukrainian society from the late eighteenth until the mid-20th centuries, following the reforms instituted by Joseph II, Holy Roman Emperor, Joseph II, Emperor of Austria. Because, like their Eastern Orthodox Church, Eastern Orthodox brethren, Ukrainian Catholic priests could marry, they were able to establish "priestly dynasties", often associated with specific regions, for many generations. Numbering approximately 2,000–2,500 by the 19th century, priestly families tended to marry within their group, constituting a tight-knit hereditary caste.. In the absence of a significant native nobility and enjoying a virtual monopoly on education and wealth within western Ukrainian society, the clergy came to form that group's native aristocracy. The clergy adopted Austria's role for them as bringers of culture and education to the Ukrainian countryside. Most Ukrainian social and political movements in Austrian-controlled territory emerged or were highly influenced by the clergy themselves or by their children. This influence was so great that western Ukrainians were accused of wanting to create a theocracy in western Ukraine by their Polish rivals. The central role played by the Ukrainian clergy or their children in western Ukrainian society would weaken somewhat at the end of the 19th century but would continue until the mid-20th century.United States

The American gentry were rich landowning members of the American upper class in the colonial South. The Thirteen Colonies, Colonial American use of ''gentry'' was not common. Historians use it to refer to rich landowners in the South before 1776. Typically large scale landowners rented out farms to white tenant farmers. North of Maryland, there were few large comparable rural estates, except in the Dutch domains in the Hudson Valley of New York.

The Thirteen Colonies, Colonial American use of ''gentry'' was not common. Historians use it to refer to rich landowners in the South before 1776. Typically large scale landowners rented out farms to white tenant farmers. North of Maryland, there were few large comparable rural estates, except in the Dutch domains in the Hudson Valley of New York.

Great Britain

The British upper classes consist of two sometimes overlapping entities, the peerage andlanded gentry

The landed gentry, or the ''gentry'', is a largely historical British social class of landowners who could live entirely from rental income, or at least had a country estate. While distinct from, and socially below, the British peerage, th ...

. In the British peerage, only the senior family member (typically the eldest son) inherits a substantive title (duke, marquess, earl, viscount, baron); these are referred to as peers or lords. The rest of the nobility form part of the "landed gentry" (abbreviated "gentry"). The members of the gentry usually bear no titles but can be described as esquire or gentleman. Exceptions are the eldest sons of peers, who bear their fathers' inferior titles as "courtesy titles" (but for Parliamentary purposes count as commoners), Barons in Scotland, Scottish barons (who bear the designation Baron of X after their name) and baronets (a title corresponding to a hereditary knighthood). Laird, Scottish lairds do not have a title of nobility but may have a description of their lands in the form of a territorial designation that forms part of their name.

The landed gentry is a traditional British social class

A social class is a grouping of people into a set of Dominance hierarchy, hierarchical social categories, the most common being the Upper class, upper, Middle class, middle and Working class, lower classes. Membership in a social class can for ...

consisting of gentlemen in the original sense; that is, those who owned land in the form of country estates to such an extent that they were not required to actively work, except in an administrative capacity on their own lands. The estates were often (but not always) made up of tenant farm, tenanted farms, in which case the gentleman could live entirely off renting, rent income. Gentlemen, ranking below esquires and above yeomen, form the lowest rank of British nobility. It is the lowest rank to which the descendants of a Knight, Baronet or Peer can sink. Strictly speaking, anybody with officially matriculated English or Scottish arms is a gentleman and thus noble.

The term ''landed gentry'', although originally used to mean nobility, came to be used for the lesser nobility in England around 1540. Once identical, these terms eventually became complementary. The term ''gentry'' by itself, as commonly used by historians, according to Peter Coss

Peter R. Coss is a British historian, specialising in the history of the English medieval gentry. He is Emeritus Professor of Medieval History at the School of History, Archaeology, and Religion at Cardiff University, Wales. His research interests ...

, is a construct applied loosely to rather different societies. Any particular model may not fit a specific society, yet a single definition nevertheless remains desirable. Titles, while often considered central to the upper class, are not strictly so. Both Captain Mark Phillips and Vice Admiral Sir Timothy Laurence, the respective first and second husbands of Forms of address in the United Kingdom, HRH Anne, Princess Royal, Princess Anne, lacked any rank of peerage at the time of their marriage to Princess Anne. However, the backgrounds of both men were considered to be essentially patrician, and they were thus deemed suitable husbands for a princess.

Esquire (abbreviated Esq.) is a term derived from the Old French word "escuier" (which also gave equerry) and is in the United Kingdom the second-lowest designation for a nobleman, referring only to males, and used to denote a high but indeterminate social status. The most common occurrence of term ''Esquire'' today is the conferral as the suffix ''Esq.'' in order to pay an informal compliment to a male recipient by way of implying Nobility, gentle birth. In the post-medieval world, the title of ''esquire'' came to apply to all men of the higher landed gentry; an esquire ranked socially above a gentleman but below a knight. In the modern world, where all men are assumed to be gentlemen, the term has often been extended (albeit only in very formal writing) to all men without any higher title. It is used post-nominally, usually in abbreviated form (for example, "Thomas Smith, Esq.").

A knight could refer to either a medieval tenant who gave military service as a mounted man-at-arms to a feudal landholder, or a medieval gentleman-soldier, usually high-born, raised by a sovereign to privileged military status after training as a page and squire (for a contemporary reference, see British honours system). In formal protocol, ''Sir'' is the correct Style (manner of address), styling for a knight or for a baronet, used with (one of) the knight's given name(s) or full name, but not with the surname alone. The equivalent for a woman who holds the title in her own right is Dame (title), Dame; for such women, the title ''Dame'' is used as ''Sir'' for a man, never before the surname on its own. This usage was devised in 1917, derived from the practice, up to the 17th century (and still also in legal proceedings), for the wife of a knight. The wife of a knight or baronet is now styled "Lady [husband's surname]".Historiography

The "Storm over the gentry" was a major historiographical debate among scholars that took place in the 1940s and 1950s regarding the role of the gentry in causing the English Civil War of the 17th century. R. H. Tawney had suggested in 1941 that there was a major economic crisis for the nobility in the 16th and 17th centuries, and that the rapidly rising gentry class was demanding a share of power. When the aristocracy resisted, Tawney argued, the gentry launched the civil war. After heated debate, historians generally concluded that the role of the gentry was not especially important.Irish

East Asia

China

The 'four divisions of society' refers to the Four occupations (China), model of society in ancient China and was a meritocraticsocial class

A social class is a grouping of people into a set of Dominance hierarchy, hierarchical social categories, the most common being the Upper class, upper, Middle class, middle and Working class, lower classes. Membership in a social class can for ...

system in China and other subsequently influenced Confucian societies. The four castes—gentry, farmers, artisans and merchants—are combined to form the term Shìnónggōngshāng (士農工商).

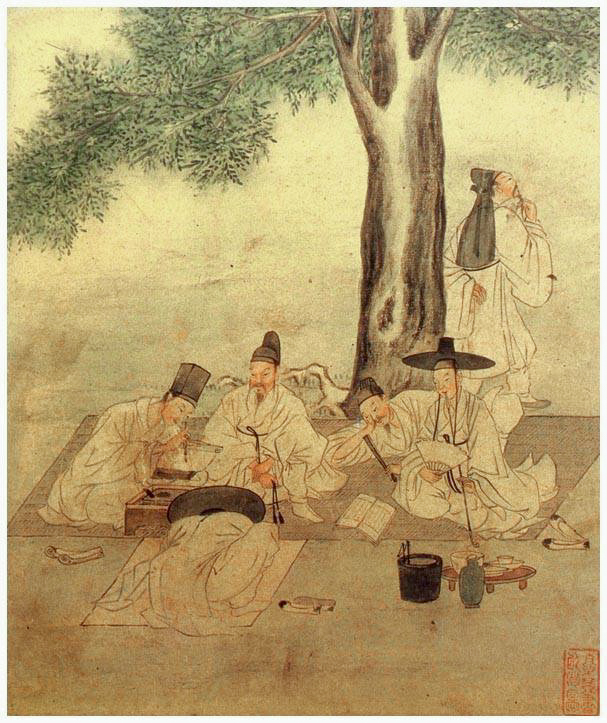

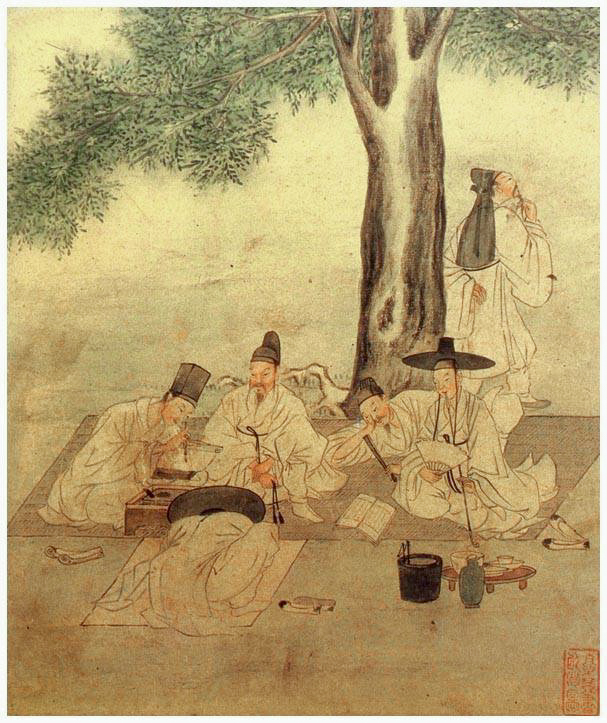

Gentry (士) means different things in different countries. In China, Korea, and Vietnam, this meant that the Confucian scholar gentry that would – for the most part – make up most of the bureaucracy. This caste would comprise both the more-or-less hereditary aristocracy as well as the meritocratic scholars that rise through the rank by public service and, later, by imperial exams. Some sources, such as Xun Kuang, Xunzi, list farmers before the gentry, based on the Confucian view that they directly contributed to the welfare of the state. In China, the farmer lifestyle is also closely linked with the ideals of Confucian gentlemen.

In Japan, this caste essentially equates to the samurai class. In the Edo period, with the creation of the Han (country subdivision), Domains (''han'') under the rule of Tokugawa Ieyasu, all land was confiscated and reissued as fiefdoms to the ''daimyōs''.

The small lords, the , were ordered either to give up their swords and rights and remain on their lands as peasants or to move to the castle cities to become paid retainers of the ''daimyōs''. Only a few samurai were allowed to remain in the countryside; the . Some 5 per cent of the population were samurai. Only the samurai could have proper surnames, something that after the Meiji Restoration became compulsory to all inhabitants (see Japanese name).

Hierarchical structure of Feudal Japan

There were two leading classes, i.e. the gentry, in the time of feudal Japan: the ''daimyō'' and the ''samurai''. The Confucian ideals in the Japanese culture emphasised the importance of productive members of society, so farmers and fishermen were considered of a higher status than merchants.

Emperor Meiji abolished the samurai's right to be the only armed force in favor of a more modern, Western-style, conscripted army in 1873. Samurai became ''Shizoku'' (), but the right to wear a katana in public was eventually abolished along with the right to execution, execute commoners who paid them disrespect.

In defining how a modern Japan should be, members of the Meiji government decided to follow in the footsteps of the United Kingdom and Germany, basing the country on the concept of ''noblesse oblige''. Samurai were not to be a political force under the new order. The difference between the Japanese and European feudal systems was that European feudalism was grounded in Roman law, Roman legal structure, while Japan feudalism had Chinese Confucianism, Confucian morality as its basis.

There were two leading classes, i.e. the gentry, in the time of feudal Japan: the ''daimyō'' and the ''samurai''. The Confucian ideals in the Japanese culture emphasised the importance of productive members of society, so farmers and fishermen were considered of a higher status than merchants.

Emperor Meiji abolished the samurai's right to be the only armed force in favor of a more modern, Western-style, conscripted army in 1873. Samurai became ''Shizoku'' (), but the right to wear a katana in public was eventually abolished along with the right to execution, execute commoners who paid them disrespect.

In defining how a modern Japan should be, members of the Meiji government decided to follow in the footsteps of the United Kingdom and Germany, basing the country on the concept of ''noblesse oblige''. Samurai were not to be a political force under the new order. The difference between the Japanese and European feudal systems was that European feudalism was grounded in Roman law, Roman legal structure, while Japan feudalism had Chinese Confucianism, Confucian morality as its basis.

Korea

Korean monarchy and the native ruling upper class existed in Korea until the end of the Korea under Japanese rule, Japanese occupation. The system concerning the nobility is roughly the same as that of the Chinese nobility. As the monastical orders did during Europe's Dark Ages (historiography), Dark Ages, the Buddhist monks became the purveyors and guardians of Korea's literary traditions while documenting Korea's written history and legacies from the Silla period to the end of the Goryeo dynasty. Korean Buddhist monks also developed and used the first movable metal type printing presses in history—some 500 years before Johannes Gutenberg, Gutenberg—to print ancient Buddhist texts. Buddhist monks also engaged in record keeping, food storage and distribution, as well as the ability to exercise power by influencing the Goryeo royal court.Values and traditions

Military and clerical

Historically, the nobles in Europe became soldiers; the aristocracy in Europe can trace their origins to military leaders from the migration period and the Middle Ages. For many years, the British Army, together with the Church, was seen as the ideal career for the younger sons of the aristocracy. Although now much diminished, the practice has not totally disappeared. Such practices are not unique to the British either geographically or historically. As a very practical form of displaying patriotism, it has been at times fashionable for "gentlemen" to participate in the military. The fundamental idea of gentry had come to be that of the essential superiority of the fighting man, usually maintained in the granting of arms. At the last, the wearing of a sword on all occasions was the outward and visible sign of a "gentleman"; the custom survives in the sword worn with "court dress". A suggestion that a gentleman must have a coat of arms was vigorously advanced by certain 19th- and 20th-century heraldists, notably Arthur Charles Fox-Davies in England and Thomas Innes of Learney in Scotland. The significance of a right to a coat of arms was that it was definitive proof of the status of gentleman, but it recognised rather than conferred such a status, and the status could be and frequently was accepted without a right to a coat of arms.Chivalry

''Chivalry'' is a term related to the medieval institution of knighthood. It is usually associated with ideals of knightly virtues, honour and courtly love.

Christianity had a modifying influence on the virtues of chivalry, with limits placed on knights to protect and honour the weaker members of society and maintain peace. The church became more tolerant of war in the defence of faith, espousing theories of the just war. In the 11th century, the concept of a "knight of Christ" (''miles Christi'') gained currency in France, Spain and Italy.. These concepts of "religious chivalry" were further elaborated in the era of the Crusades.

In the later Middle Ages, wealthy merchants strove to adopt chivalric attitudes. This was a democratisation of chivalry, leading to a new genre called the courtesy book, which were guides to the behaviour of "gentlemen".

When examining mediaeval literature, medieval literature, chivalry can be classified into three basic but overlapping areas:

# Duties to countrymen and fellow Christians

# Duties to God

# Duties to women

These three areas obviously overlap quite frequently in chivalry and are often indistinguishable. Another classification of chivalry divides it into warrior, religious and courtly love strands. One particular similarity between all three of these categories is honour. Honour is the foundational and guiding principle of chivalry. Thus, for the knight, honour would be one of the guides of action.

''Chivalry'' is a term related to the medieval institution of knighthood. It is usually associated with ideals of knightly virtues, honour and courtly love.

Christianity had a modifying influence on the virtues of chivalry, with limits placed on knights to protect and honour the weaker members of society and maintain peace. The church became more tolerant of war in the defence of faith, espousing theories of the just war. In the 11th century, the concept of a "knight of Christ" (''miles Christi'') gained currency in France, Spain and Italy.. These concepts of "religious chivalry" were further elaborated in the era of the Crusades.

In the later Middle Ages, wealthy merchants strove to adopt chivalric attitudes. This was a democratisation of chivalry, leading to a new genre called the courtesy book, which were guides to the behaviour of "gentlemen".

When examining mediaeval literature, medieval literature, chivalry can be classified into three basic but overlapping areas:

# Duties to countrymen and fellow Christians

# Duties to God

# Duties to women

These three areas obviously overlap quite frequently in chivalry and are often indistinguishable. Another classification of chivalry divides it into warrior, religious and courtly love strands. One particular similarity between all three of these categories is honour. Honour is the foundational and guiding principle of chivalry. Thus, for the knight, honour would be one of the guides of action.

Gentleman

The term gentleman (from Latin ''gentilis'', belonging to a race or ''gens'', and "man", cognate with the French word ''gentilhomme'', the Spanish ''gentilhombre'' and the Italian ''gentil uomo'' or ''gentiluomo''), in its original and strict signification, denoted a man of good family, analogous to the Latin ''generosus'' (its invariable translation in English-Latin documents). In this sense the word equates with the French ''gentilhomme'' ("nobleman"), which was in Great Britain long confined to the peerage. The term ''gentry'' (from the Old French ''genterise'' for ''gentelise'') has much of the social-class significance of the French ''noblesse'' or of the German ''Adel'', but without the strict technical requirements of those traditions (such as quarters of nobility). To a degree, ''gentleman'' signified a man with an income derived from landed property, a old money, legacy or some other source and was thus independently wealthy and did not need to work.

The term gentleman (from Latin ''gentilis'', belonging to a race or ''gens'', and "man", cognate with the French word ''gentilhomme'', the Spanish ''gentilhombre'' and the Italian ''gentil uomo'' or ''gentiluomo''), in its original and strict signification, denoted a man of good family, analogous to the Latin ''generosus'' (its invariable translation in English-Latin documents). In this sense the word equates with the French ''gentilhomme'' ("nobleman"), which was in Great Britain long confined to the peerage. The term ''gentry'' (from the Old French ''genterise'' for ''gentelise'') has much of the social-class significance of the French ''noblesse'' or of the German ''Adel'', but without the strict technical requirements of those traditions (such as quarters of nobility). To a degree, ''gentleman'' signified a man with an income derived from landed property, a old money, legacy or some other source and was thus independently wealthy and did not need to work.

Confucianism

The East Asia, Far East also held similar ideas to the West of what a gentleman is, which are based on Confucianism, Confucian principles. The term ''Junzi, Jūnzǐ'' (君子) is a term crucial to classical Confucianism. Literally meaning "son of a ruler", "prince" or "noble", the ideal of a "gentleman", "proper man", "exemplary person", or "perfect man" is that for which Confucianism exhorts all people to strive. A succinct description of the "perfect man" is one who "combine[s] the qualities of saint, scholar, and gentleman" (Catholic Encyclopedia, CE). A hereditary elitism was bound up with the concept, and gentlemen were expected to act as moral guides to the rest of society. They were to: * cultivate themselves morally; * participate in the correct performance of ritual; * show filial piety and loyalty where these are due; and * cultivate humaneness. The opposite of the ''Jūnzǐ'' was the ''Xiǎorén'' (小人), literally "small person" or "petty person". Like English "small", the word in this context in Chinese can mean petty in mind and heart, narrowly self-interested, greedy, superficial, and materialistic.Noblesse oblige

The idea of ''noblesse oblige'', "nobility obliges", among gentry is, as the ''Oxford English Dictionary'' expresses, that the term "suggests noble ancestry constrains to honorable behaviour; privilege entails to responsibility". Being a noble meant that one had responsibilities to lead, manage and so on. One was not to simply spend one's time in idle pursuits.Heraldry

A coat of arms is a heraldic device dating to the 12th century in Europe. It was originally a cloth tunic worn over or in place of armour to establish identity in battle.. The coat of arms is drawn with heraldic rules for a person, family or organisation. Family coats of arms were originally derived from personal ones, which then became extended in time to the whole family. In Scotland, family coats of arms are still personal ones and are mainly used by the head of the family. In heraldry, a person entitled to a coat of arms is an armiger, and their family would be armigerous.

A coat of arms is a heraldic device dating to the 12th century in Europe. It was originally a cloth tunic worn over or in place of armour to establish identity in battle.. The coat of arms is drawn with heraldic rules for a person, family or organisation. Family coats of arms were originally derived from personal ones, which then became extended in time to the whole family. In Scotland, family coats of arms are still personal ones and are mainly used by the head of the family. In heraldry, a person entitled to a coat of arms is an armiger, and their family would be armigerous.

Ecclesiastical heraldry

Ecclesiastical heraldry is the tradition of heraldry developed by Christian clergy. Initially used to mark documents, ecclesiastical heraldry evolved as a system for identifying people and dioceses. It is most formalised within the Catholic Church, where most bishops, including the pope, have a personalcoat of arms

A coat of arms is a heraldry, heraldic communication design, visual design on an escutcheon (heraldry), escutcheon (i.e., shield), surcoat, or tabard (the latter two being outer garments). The coat of arms on an escutcheon forms the central ele ...

. Clergy in Anglicanism, Anglican, Lutheranism, Lutheran, Eastern Catholic Churches, Eastern Catholic, and Eastern Christianity, Orthodox churches follow similar customs.

See also

* American gentry * Aristocracy * Cabang Atas * Ecclesiastical address * Gentlewoman * Grand Burgher * Habitus (sociology), Habitus * Hanseaten (class) * Landed gentry * Nobility * Patrician (ancient Rome) * Principalía * Priyayi * ''Redorer son blason'' * Bildungsbürgertum * Social environment * Symbolic capital * Szlachta * YeomanNotes

References

Further reading

Great Britain

* Acheson, Eric. ''A gentry community: Leicestershire in the fifteenth century, c. 1422–c. 1485'' (Cambridge University Press, 2003). * Butler, Joan. ''Landed Gentry'' (1954) * Coss, Peter R. ''The origins of the English gentry'' (2005online

* Heal, Felicity. ''The gentry in England and Wales, 1500–1700'' (1994

online

* Mingay, Gordon E. ''The Gentry: The Rise and Fall of a Ruling Class'' (1976

online

* O'Hart, John. ''The Irish And Anglo-Irish Landed Gentry, When Cromwell Came to Ireland: or, a Supplement to Irish Pedigrees'' (2 vols) (reprinted 2007) * Sayer, M. J. ''English Nobility: The Gentry, the Heralds and the Continental Context'' (Norwich, 1979) * Wallis, Patrick, and Cliff Webb. "The education and training of gentry sons in early modern England." ''Social History'' 36.1 (2011): 36–53

online

Europe

* Eatwell, Roger, ed. ''European political cultures'' (Routledge, 2002). * Jones, Michael ed. ''Gentry and Lesser Nobility in Late Medieval Europe'' (1986online

* Lieven, Dominic C.B. ''The aristocracy in Europe, 1815–1914'' (Macmillan, 1992). * Wallerstein, Immanuel. ''The modern world-system I: Capitalist agriculture and the origins of the European world-economy in the sixteenth century. Vol. 1'' (Univ of California Press, 2011). * Wasson, Ellis. ''Aristocracy and the modern world'' (Macmillan International Higher Education, 2006), for 19th and 20th centuries

Historiography

* Hexter, Jack H. ''Reappraisals in history: New views on history and society in early modern Europe'' (1961), emphasis on England. * MacDonald, William W. "English Historians Repeating Themselves: The Refining of the Whig Interpretation of the English Revolution and Civil War." ''Journal of Thought'' (1972): 166–175online

* Tawney, R. H. "The rise of the gentry, 1558–1640." ''Economic History Review'' 11.1 (1941): 1–38

online

launched a historiographical debate * Tawney, R. H. "The rise of the gentry: a postscript." ''Economic History Review'' 7.1 (1954): 91–97

online

China

* Bastid-Bruguiere, Marianne. "Currents of social change." ''The Cambridge History of China 11.2 1800–1911'' (1980): pp. 536–571. * Brook, Timothy. ''Praying for power: Buddhism and the formation of gentry society in late-Ming China'' (Brill, 2020). * Chang, Chung-li. ''The Chinese gentry: studies on their role in nineteenth-century Chinese society'' (1955online

* Chuzo, Ichiko; "The role of the gentry: an hypothesis." in ''China in Revolution: The First Phase, 1900–1913'' ed. by Mary C. Wright (1968) pp: 297–317. * Miller, Harry. ''State versus Gentry in Late Ming Dynasty China, 1572–1644'' (Springer, 2008).

External links

* {{Authority control Gentry, High society (social class) Nobility