Gunpowder plot on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

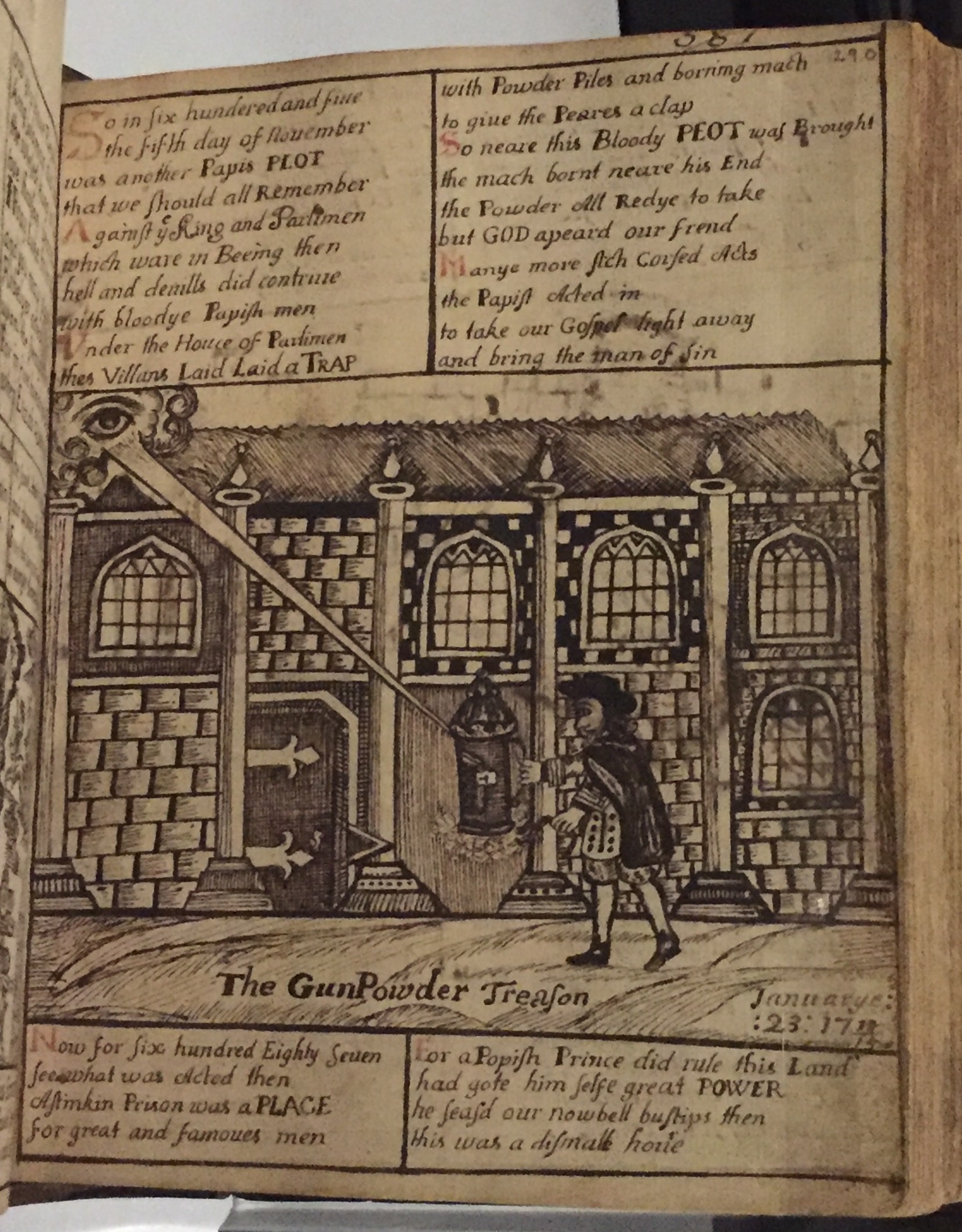

The Gunpowder Plot of 1605, in earlier centuries often called the Gunpowder Treason Plot or the Jesuit Treason, was an unsuccessful attempted regicide against King James VI of Scotland and I of England by a group of

Between 1533 and 1540,

Between 1533 and 1540,

The conspirators' principal aim was to kill King James, but many other important targets would also be present at the State Opening of Parliament, including the monarch's nearest relatives and members of the Privy Council. The senior judges of the English legal system, most of the Protestant aristocracy, and the bishops of the Church of England would all have attended in their capacity as members of the House of Lords, along with the members of the

The conspirators' principal aim was to kill King James, but many other important targets would also be present at the State Opening of Parliament, including the monarch's nearest relatives and members of the Privy Council. The senior judges of the English legal system, most of the Protestant aristocracy, and the bishops of the Church of England would all have attended in their capacity as members of the House of Lords, along with the members of the

Following their oath, the plotters left London and returned to their homes.

The conspirators returned to London in October 1604, when Robert Keyes, a "desperate man, ruined and indebted", was admitted to the group. His responsibility was to take charge of Catesby's house in Lambeth, where the gunpowder and other supplies were to be stored. Keyes's family had notable connections; his wife's employer was the Catholic Lord Mordaunt. He was tall, with a red beard, and was seen as trustworthy and—like Fawkes—capable of looking after himself. In December Catesby recruited his servant, Thomas Bates, into the plot, after the latter accidentally became aware of it.

It was announced on 24 December 1604 that the scheduled February re-opening of Parliament would be delayed. Concern over the plague meant that rather than sitting in February, as the plotters had originally planned for, Parliament would not sit again until 3 October 1605. The contemporaneous account of the prosecution claimed that during this delay the conspirators were digging a tunnel beneath Parliament. This may have been a government fabrication, as no evidence for the existence of a tunnel was presented by the prosecution, and no trace of one has ever been found. The account of a tunnel comes directly from Thomas Wintour's confession, and Guy Fawkes did not admit the existence of such a scheme until his fifth interrogation. Logistically, digging a tunnel would have proved extremely difficult, especially as none of the conspirators had any experience of mining. If the story is true, by 6 December 1604 the Scottish commissioners had finished their work, and the conspirators were busy tunnelling from their rented house to the House of Lords. They ceased their efforts when, during tunnelling, they heard a noise from above. The noise turned out to be the then-tenant's widow, who was clearing out the

Following their oath, the plotters left London and returned to their homes.

The conspirators returned to London in October 1604, when Robert Keyes, a "desperate man, ruined and indebted", was admitted to the group. His responsibility was to take charge of Catesby's house in Lambeth, where the gunpowder and other supplies were to be stored. Keyes's family had notable connections; his wife's employer was the Catholic Lord Mordaunt. He was tall, with a red beard, and was seen as trustworthy and—like Fawkes—capable of looking after himself. In December Catesby recruited his servant, Thomas Bates, into the plot, after the latter accidentally became aware of it.

It was announced on 24 December 1604 that the scheduled February re-opening of Parliament would be delayed. Concern over the plague meant that rather than sitting in February, as the plotters had originally planned for, Parliament would not sit again until 3 October 1605. The contemporaneous account of the prosecution claimed that during this delay the conspirators were digging a tunnel beneath Parliament. This may have been a government fabrication, as no evidence for the existence of a tunnel was presented by the prosecution, and no trace of one has ever been found. The account of a tunnel comes directly from Thomas Wintour's confession, and Guy Fawkes did not admit the existence of such a scheme until his fifth interrogation. Logistically, digging a tunnel would have proved extremely difficult, especially as none of the conspirators had any experience of mining. If the story is true, by 6 December 1604 the Scottish commissioners had finished their work, and the conspirators were busy tunnelling from their rented house to the House of Lords. They ceased their efforts when, during tunnelling, they heard a noise from above. The noise turned out to be the then-tenant's widow, who was clearing out the

In the second week of June, Catesby met in London the principal

In the second week of June, Catesby met in London the principal

The details of the plot were finalised in October, in a series of taverns across London and

The details of the plot were finalised in October, in a series of taverns across London and

Although two accounts of the number of searches and their timing exist, according to the King's version, the first search of the buildings in and around Parliament was made on Monday 4 November—as the plotters were busy making their final preparations—by Suffolk, Monteagle, and John Whynniard. They found a large pile of firewood in the undercroft beneath the House of Lords, accompanied by what they presumed to be a serving man (Fawkes), who told them that the firewood belonged to his master, Thomas Percy. They left to report their findings, at which time Fawkes also left the building. The mention of Percy's name aroused further suspicion as he was already known to the authorities as a Catholic agitator. The King insisted that a more thorough search be undertaken. Late that night, the search party, headed by Thomas Knyvet, returned to the undercroft. They again found Fawkes, dressed in a cloak and hat, and wearing boots and spurs. He was arrested, whereupon he gave his name as John Johnson. He was carrying a lantern now held in the

Although two accounts of the number of searches and their timing exist, according to the King's version, the first search of the buildings in and around Parliament was made on Monday 4 November—as the plotters were busy making their final preparations—by Suffolk, Monteagle, and John Whynniard. They found a large pile of firewood in the undercroft beneath the House of Lords, accompanied by what they presumed to be a serving man (Fawkes), who told them that the firewood belonged to his master, Thomas Percy. They left to report their findings, at which time Fawkes also left the building. The mention of Percy's name aroused further suspicion as he was already known to the authorities as a Catholic agitator. The King insisted that a more thorough search be undertaken. Late that night, the search party, headed by Thomas Knyvet, returned to the undercroft. They again found Fawkes, dressed in a cloak and hat, and wearing boots and spurs. He was arrested, whereupon he gave his name as John Johnson. He was carrying a lantern now held in the

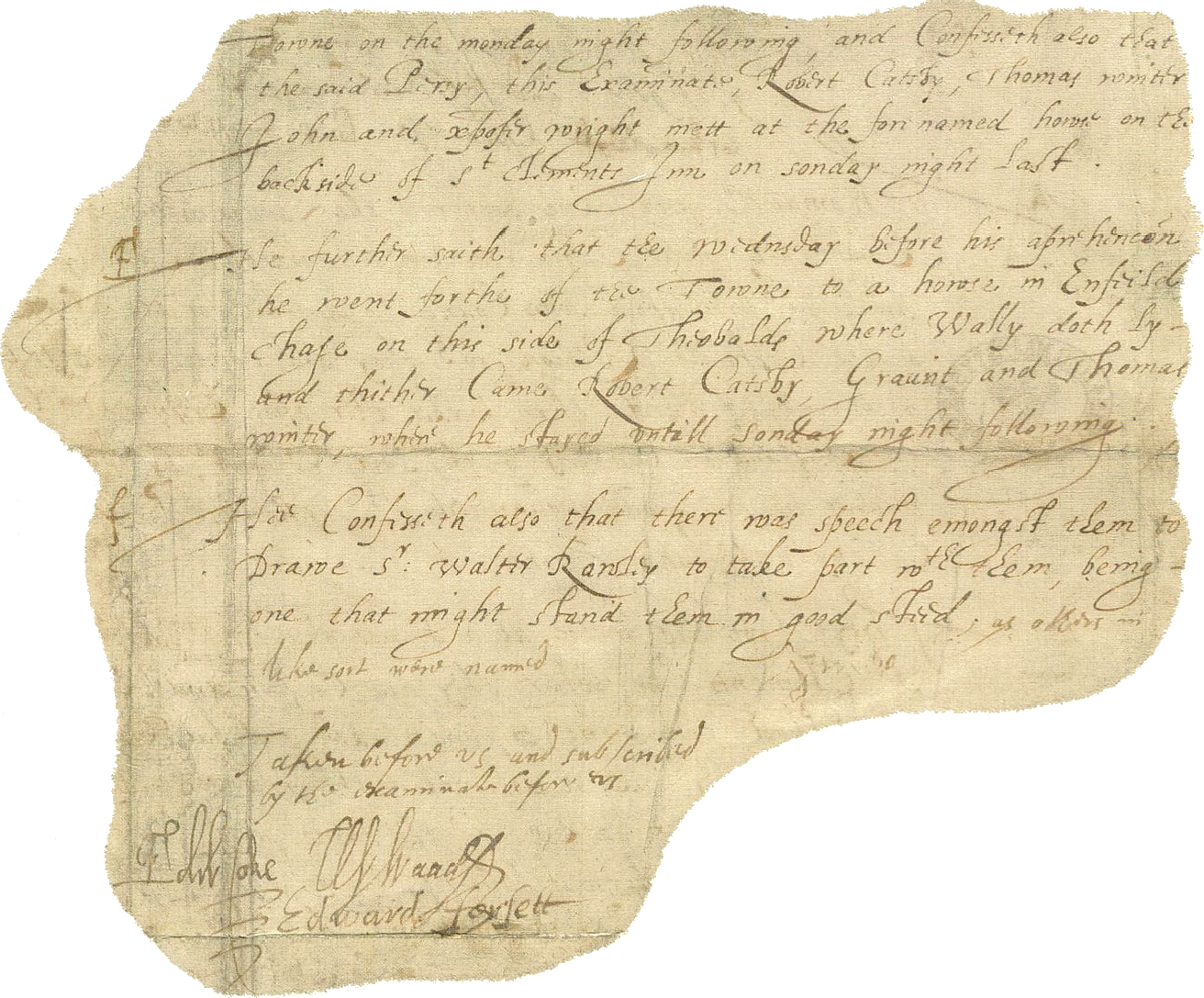

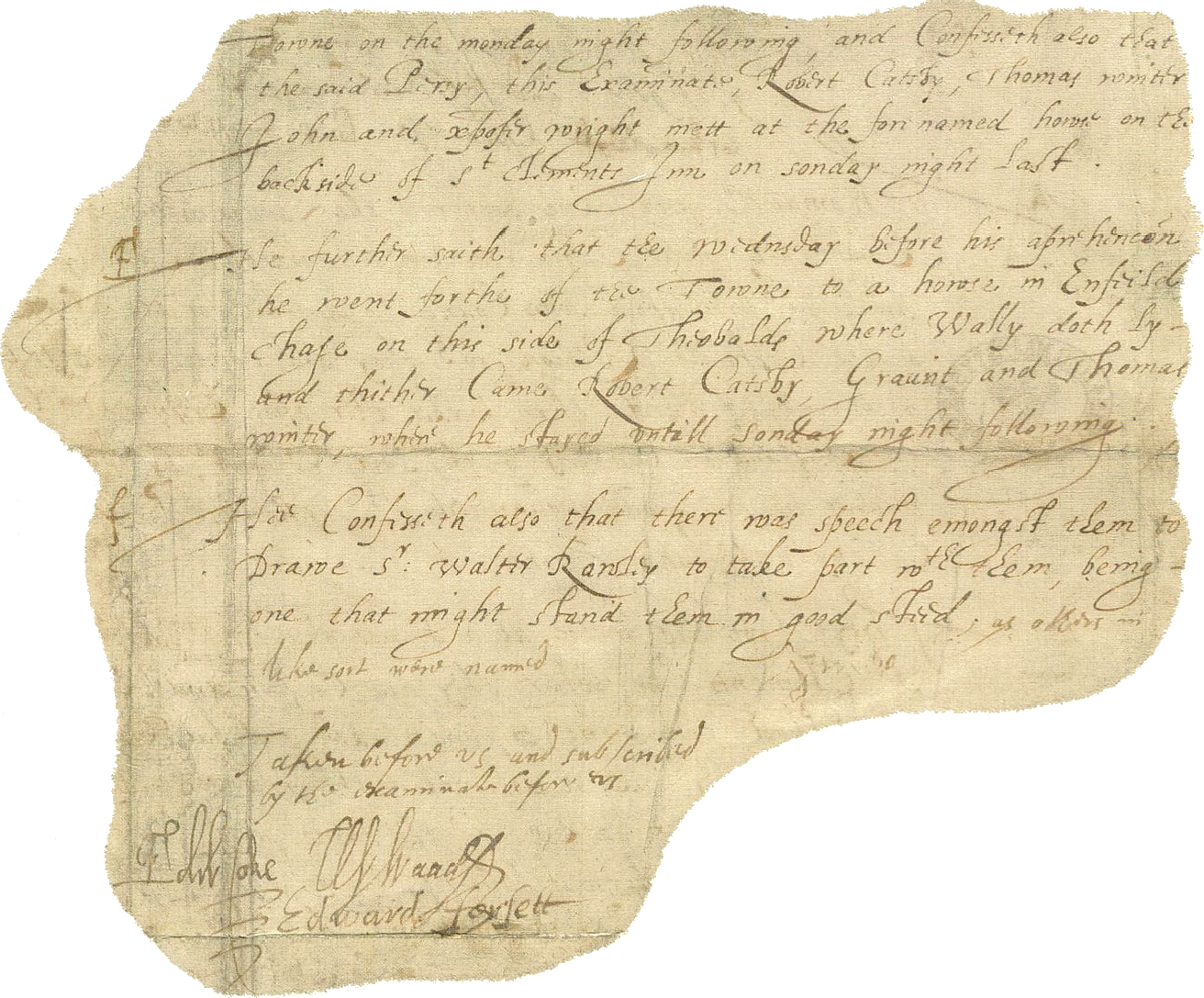

On 6 November, the Lord Chief Justice, Sir John Popham (a man with a deep-seated hatred of Catholics) questioned Rookwood's servants. By the evening he had learned the names of several of those involved in the conspiracy: Catesby, Rookwood, Keyes, Wynter, John and Christopher Wright, and Grant. "Johnson" meanwhile persisted with his story, and along with the gunpowder he was found with, was moved to the

On 6 November, the Lord Chief Justice, Sir John Popham (a man with a deep-seated hatred of Catholics) questioned Rookwood's servants. By the evening he had learned the names of several of those involved in the conspiracy: Catesby, Rookwood, Keyes, Wynter, John and Christopher Wright, and Grant. "Johnson" meanwhile persisted with his story, and along with the gunpowder he was found with, was moved to the

Sir

Sir

Thomas Bates confessed on 4 December, providing much of the information that Salisbury needed to link the Catholic clergy to the plot. Bates had been present at most of the conspirators' meetings, and under interrogation he implicated Tesimond in the plot. On 13 January 1606, he described how he had visited Garnet and Tesimond on 7 November to inform Garnet of the plot's failure. Bates also told his interrogators of his ride with Tesimond to Huddington, before the priest left him to head for the Habingtons at Hindlip Hall, and of a meeting between Garnet, Gerard, and Tesimond in October 1605.

At about the same time in December, Tresham's health began to deteriorate. He was visited regularly by his wife, a nurse, and his servant William Vavasour—who documented his strangury. Before he died, Tresham had also told of Garnet's involvement with the 1603 mission to Spain, but in his last hours he retracted some of these statements. Nowhere in his confession did he mention the Monteagle letter. He died early on the morning of 23 December, and was buried in the Tower. Nevertheless, he was attainted along with the other plotters; his head was set on a pike either (accounts differ) at

Thomas Bates confessed on 4 December, providing much of the information that Salisbury needed to link the Catholic clergy to the plot. Bates had been present at most of the conspirators' meetings, and under interrogation he implicated Tesimond in the plot. On 13 January 1606, he described how he had visited Garnet and Tesimond on 7 November to inform Garnet of the plot's failure. Bates also told his interrogators of his ride with Tesimond to Huddington, before the priest left him to head for the Habingtons at Hindlip Hall, and of a meeting between Garnet, Gerard, and Tesimond in October 1605.

At about the same time in December, Tresham's health began to deteriorate. He was visited regularly by his wife, a nurse, and his servant William Vavasour—who documented his strangury. Before he died, Tresham had also told of Garnet's involvement with the 1603 mission to Spain, but in his last hours he retracted some of these statements. Nowhere in his confession did he mention the Monteagle letter. He died early on the morning of 23 December, and was buried in the Tower. Nevertheless, he was attainted along with the other plotters; his head was set on a pike either (accounts differ) at

By coincidence, on the same day that Garnet was found, the surviving conspirators were arraigned in

By coincidence, on the same day that Garnet was found, the surviving conspirators were arraigned in

The discovery of such a wide-ranging conspiracy and the subsequent trials led Parliament to consider new anti-Catholic legislation. The event destroyed all hope that the Spanish would ever secure tolerance of the Catholics in England. In the summer of 1606, laws against recusancy were strengthened; the Popish Recusants Act returned England to the Elizabethan system of fines and restrictions, introduced a sacramental test, and an Oath of Allegiance, requiring Catholics to abjure as a "heresy" the doctrine that "princes excommunicated by the Pope could be deposed or assassinated". Catholic emancipation took another 200 years, but many important and loyal Catholics retained high office during James I's reign. Although there was no "golden time" of "toleration" of Catholics, which Garnet had hoped for, James's reign was nevertheless a period of relative leniency for Catholics.

The playwright

The discovery of such a wide-ranging conspiracy and the subsequent trials led Parliament to consider new anti-Catholic legislation. The event destroyed all hope that the Spanish would ever secure tolerance of the Catholics in England. In the summer of 1606, laws against recusancy were strengthened; the Popish Recusants Act returned England to the Elizabethan system of fines and restrictions, introduced a sacramental test, and an Oath of Allegiance, requiring Catholics to abjure as a "heresy" the doctrine that "princes excommunicated by the Pope could be deposed or assassinated". Catholic emancipation took another 200 years, but many important and loyal Catholics retained high office during James I's reign. Although there was no "golden time" of "toleration" of Catholics, which Garnet had hoped for, James's reign was nevertheless a period of relative leniency for Catholics.

The playwright

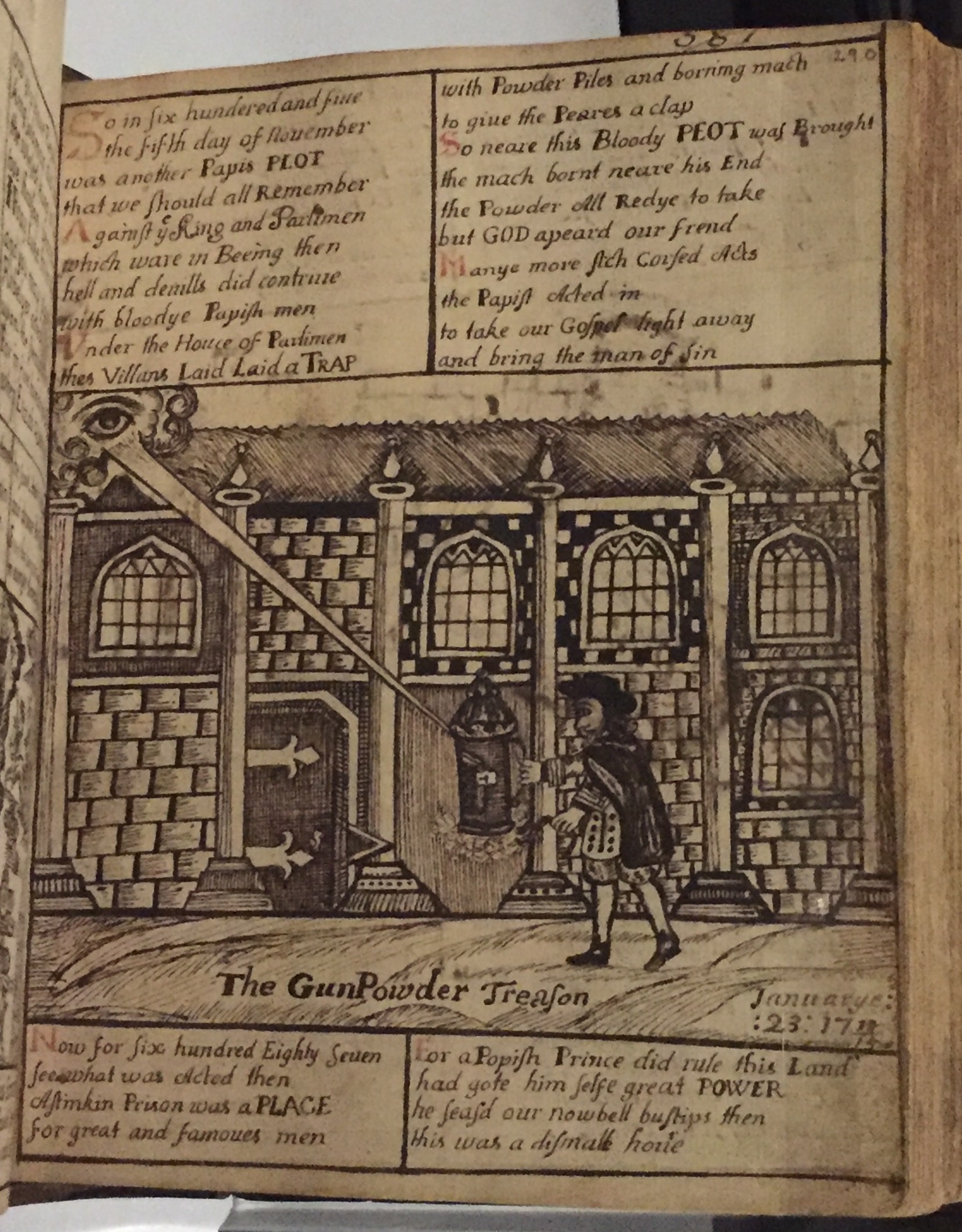

In January 1606, during the first sitting of Parliament since the plot, the Observance of 5th November Act 1605 was passed, making services commemorating the event an annual feature of English life; the act remained in force until 1859. The tradition of marking the day with the ringing of church bells and bonfires started soon after the Plot's discovery, and

In January 1606, during the first sitting of Parliament since the plot, the Observance of 5th November Act 1605 was passed, making services commemorating the event an annual feature of English life; the act remained in force until 1859. The tradition of marking the day with the ringing of church bells and bonfires started soon after the Plot's discovery, and

In the 2005 ITV programme '' The Gunpowder Plot: Exploding the Legend'', a full-size replica of the House of Lords was built and destroyed with barrels of gunpowder, totalling 1

In the 2005 ITV programme '' The Gunpowder Plot: Exploding the Legend'', a full-size replica of the House of Lords was built and destroyed with barrels of gunpowder, totalling 1

The Gunpowder Plot

The original House of Commons Journal recording the discovery of the plot – Parliamentary Archives catalogue

Digital image of the Original Thanksgiving Act following the Gunpowder Plot from the Parliamentary Archives

Photograph of the Guy Fawkes Search that takes place at the start of a new Parliament – Parliamentary Archives

The Palace of Westminster in 1605 from the Parliamentary Archives

The Gunpowder Plot Society

The story of Guy Fawkes and The Gunpowder Plot

from '' BBC History'', with archive video clips

What If the Gunpowder Plot Had Succeeded?

Interactive Guide: Gunpowder Plot

''

Website of a crew member of ITV's ''Exploding the Legend'' programme, with a photograph of the explosion

* Mark Nicholls

''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' online (accessed 7 November 2010) {{Authority control 1605 in England 17th century in London 17th-century coups d'état Anti-Protestantism Attacks on legislatures in the United Kingdom Charles I of England Conflicts in 1605 Conspiracies Failed assassination attempts in the United Kingdom Henry Frederick, Prince of Wales History of Catholicism in England James VI and I Palace of Westminster

English Roman Catholics

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Culture, language and peoples

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

* ''English'', an Amish ter ...

, led by Robert Catesby, who considered their actions attempted tyrannicide

Tyrannicide is the killing or assassination of a tyrant or unjust ruler, purportedly for the common good, and usually by one of the tyrant's subjects. Tyrannicide was legally permitted and encouraged in Classical Athens. Often, the term "tyrant ...

and who sought regime change in England after decades of religious persecution

Religious persecution is the systematic oppression of an individual or a group of individuals as a response to their religion, religious beliefs or affiliations or their irreligion, lack thereof. The tendency of societies or groups within socie ...

.

The plan was to blow up the House of Lords

The House of Lords is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Like the lower house, the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminster in London, England. One of the oldest ext ...

during the State Opening of Parliament

The State Opening of Parliament is a ceremonial event which formally marks the beginning of each Legislative session, session of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. At its core is His or Her Majesty's "Speech from the throne, gracious speech ...

on Tuesday 5 November 1605, as the prelude to a popular revolt in the Midlands during which King James's nine-year-old daughter, Princess Elizabeth, was to be installed as the new head of state. Catesby is suspected by historians to have embarked on the scheme after hopes of greater religious tolerance

Religious tolerance or religious toleration may signify "no more than forbearance and the permission given by the adherents of a dominant religion for other religions to exist, even though the latter are looked on with disapproval as inferior, ...

under King James I had faded, leaving many English Catholics disappointed. His fellow conspirators were John and Christopher Wright, Robert and Thomas Wintour

Robert Wintour (1568 – 30 January 1606) and Thomas Wintour (1571 or 1572 – 31 January 1606), also spelt Winter, were members of the Gunpowder Plot, a failed conspiracy to assassinate James VI and I, King James I. They were brothers, and re ...

, Thomas Percy, Guy Fawkes, Robert Keyes, Thomas Bates, John Grant, Ambrose Rookwood, Sir Everard Digby and Francis Tresham. Fawkes, who had 10 years of military experience fighting in the Spanish Netherlands

The Spanish Netherlands (; ; ; ) (historically in Spanish: , the name "Flanders" was used as a '' pars pro toto'') was the Habsburg Netherlands ruled by the Spanish branch of the Habsburgs from 1556 to 1714. They were a collection of States of t ...

in the failed suppression of the Dutch Revolt

The Eighty Years' War or Dutch Revolt (; 1566/1568–1648) was an armed conflict in the Habsburg Netherlands between disparate groups of rebels and the Spanish government. The causes of the war included the Reformation, centralisation, exc ...

, was given charge of the explosives.

On 26 October 1605 an anonymous letter of warning was sent to William Parker, 4th Baron Monteagle, a Catholic member of Parliament, who immediately showed it to the authorities. During a search of the House of Lords on the evening of 4 November 1605, Fawkes was discovered guarding 36 barrels of gunpowder

Gunpowder, also commonly known as black powder to distinguish it from modern smokeless powder, is the earliest known chemical explosive. It consists of a mixture of sulfur, charcoal (which is mostly carbon), and potassium nitrate, potassium ni ...

—enough to reduce the House of Lords to rubble—and arrested. Hearing that the plot had been discovered, most of the conspirators fled from London while trying to enlist support along the way. Several made a last stand against the pursuing Sheriff of Worcester and a posse of his men at Holbeche House; in the ensuing gunfight Catesby was one of those shot and killed. At their trial on 27 January 1606, eight of the surviving conspirators, including Fawkes, were convicted and sentenced to be hanged, drawn and quartered

To be hanged, drawn and quartered was a method of torture, torturous capital punishment used principally to execute men convicted of High treason in the United Kingdom, high treason in medieval and early modern Britain and Ireland. The convi ...

.

Some details of the assassination attempt were allegedly known by the principal Jesuit of England, Henry Garnet. Although Garnet was convicted of high treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its d ...

and put to death, doubt has been cast on how much he really knew. As the plot's existence was revealed to him through confession, Garnet was prevented from informing the authorities by the absolute confidentiality of the confessional. Although anti-Catholic legislation was introduced soon after the discovery of the plot, many important and loyal Catholics remained in high office during the rest of King James I's reign. The thwarting of the Gunpowder Plot was commemorated for many years afterwards by special sermons and other public events such as the ringing of church bells, which evolved into the British variant of Bonfire Night of today.

Background

Religion in England

Between 1533 and 1540,

Between 1533 and 1540, King Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is known for his six marriages and his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disagreement w ...

took control of the English Church from Rome, the start of several decades of religious tension in England. English Catholics struggled in a society dominated by the newly separate and increasingly Protestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the State religion#State churches, established List of Christian denominations, Christian church in England and the Crown Dependencies. It is the mother church of the Anglicanism, Anglican Christian tradition, ...

. Henry's daughter, Queen Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. She was the last and longest reigning monarch of the House of Tudor. Her eventful reign, and its effect on history ...

, responded to the growing religious divide by introducing the Elizabethan Religious Settlement

The Elizabethan Religious Settlement is the name given to the religious and political arrangements made for England during the reign of Elizabeth I (1558–1603). The settlement, implemented from 1559 to 1563, marked the end of the English Ref ...

, which required anyone appointed to a public or church office to swear allegiance to the monarch as head of the Church and state. The penalties for refusal were severe; fines were imposed for recusancy, and repeat offenders risked imprisonment and execution. Catholicism became marginalised, but despite the threat of torture or execution, priests continued to practise their faith in secret.

Succession

Queen Elizabeth, unmarried and childless, steadfastly refused to name an heir. Many Catholics believed that her Catholic cousin,Mary, Queen of Scots

Mary, Queen of Scots (8 December 1542 – 8 February 1587), also known as Mary Stuart or Mary I of Scotland, was List of Scottish monarchs, Queen of Scotland from 14 December 1542 until her forced abdication in 1567.

The only surviving legit ...

, was the legitimate heir to the English throne, but she was executed for treason in 1587. The English Secretary of State, Robert Cecil, negotiated secretly with Mary's son and successor, King James VI of Scotland

James VI and I (James Charles Stuart; 19 June 1566 – 27 March 1625) was King of Scotland as James VI from 24 July 1567 and King of England and Ireland as James I from the union of the Scottish and English crowns on 24 March 1603 until ...

. In the months before Elizabeth's death on 24 March 1603, Cecil prepared the way for James to succeed her.

Some exiled Catholics favoured Philip II of Spain

Philip II (21 May 152713 September 1598), sometimes known in Spain as Philip the Prudent (), was King of Spain from 1556, King of Portugal from 1580, and King of Naples and List of Sicilian monarchs, Sicily from 1554 until his death in 1598. He ...

's daughter, Isabella, as Elizabeth's successor. More moderate Catholics looked to James's and Elizabeth's cousin Arbella Stuart, a woman thought to have Catholic sympathies. As Elizabeth's health deteriorated, the government detained those they considered to be the "principal papists", and the Privy Council grew so worried that Arbella Stuart was moved closer to London to prevent her from being kidnapped by papists.

Despite competing claims to the English throne, the transition of power following Elizabeth's death went smoothly. James's succession was announced by a proclamation from Cecil on 24 March, which was generally celebrated. Leading papists, rather than causing trouble as anticipated, reacted to the news by offering their enthusiastic support for the new monarch. Jesuit

The Society of Jesus (; abbreviation: S.J. or SJ), also known as the Jesuit Order or the Jesuits ( ; ), is a religious order (Catholic), religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rom ...

priests, whose presence in England was punishable by death, also demonstrated their support for James, who was widely believed to embody "the natural order of things".

James ordered a ceasefire in the conflict with Spain, and even though the two countries were still technically at war, King Philip III sent his envoy, Don Juan de Tassis, to congratulate James on his accession. In the following year both countries signed the Treaty of London.

For decades, the English had lived under a monarch who refused to provide an heir, but James arrived with a family and a clear line of succession. His wife, Anne of Denmark

Anne of Denmark (; 12 December 1574 – 2 March 1619) was the wife of King James VI and I. She was List of Scottish royal consorts, Queen of Scotland from their marriage on 20 August 1589 and List of English royal consorts, Queen of Engl ...

, was the daughter of King Frederick II of Denmark. Their eldest child, the nine-year-old Henry, was considered a handsome and confident boy, and their two younger children, Elizabeth and Charles

Charles is a masculine given name predominantly found in English language, English and French language, French speaking countries. It is from the French form ''Charles'' of the Proto-Germanic, Proto-Germanic name (in runic alphabet) or ''* ...

, were proof that James was able to provide heirs to continue the Protestant monarchy.

Early reign of James I

James's attitude towards Catholics was more moderate than that of his predecessor, perhaps even tolerant. He swore that he would not "persecute any that will be quiet and give an outward obedience to the law", and believed that exile was a better solution thancapital punishment

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty and formerly called judicial homicide, is the state-sanctioned killing of a person as punishment for actual or supposed misconduct. The sentence (law), sentence ordering that an offender b ...

: "I would be glad to have both their heads and their bodies separated from this whole island and transported beyond seas." Some Catholics believed that the martyrdom of James's mother, Mary, Queen of Scots

Mary, Queen of Scots (8 December 1542 – 8 February 1587), also known as Mary Stuart or Mary I of Scotland, was List of Scottish monarchs, Queen of Scotland from 14 December 1542 until her forced abdication in 1567.

The only surviving legit ...

, would encourage James to convert to the Catholic faith, and the Catholic houses of Europe may also have shared that hope.

James received an envoy from Albert VII, ruler of the remaining Catholic territories in the Netherlands after over 30 years of war in the Dutch Revolt

The Eighty Years' War or Dutch Revolt (; 1566/1568–1648) was an armed conflict in the Habsburg Netherlands between disparate groups of rebels and the Spanish government. The causes of the war included the Reformation, centralisation, exc ...

by English-supported Protestant rebels. For the Catholic expatriates engaged in that struggle, the restoration by force of a Catholic monarchy was an intriguing possibility, but following the failed Spanish invasion of England in 1588 the papacy had taken a longer-term view on the return of a Catholic monarch to the English throne.

During James I's reign the European wars of religion

The European wars of religion were a series of wars waged in Europe during the 16th, 17th and early 18th centuries. Fought after the Protestant Reformation began in 1517, the wars disrupted the religious and political order in the Catholic Chu ...

were intensifying. Protestants and Catholics were engaged in violent persecution of each other across Europe following the Protestant Reformation

The Reformation, also known as the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation, was a time of major theological movement in Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the papacy and ...

. Catholics made several assassination attempts on Protestant rulers in Europe and in England, including plans to poison James I's predecessor, Elizabeth I. In 1589, during the French Wars of Religion

The French Wars of Religion were a series of civil wars between French Catholic Church, Catholics and Protestantism, Protestants (called Huguenots) from 1562 to 1598. Between two and four million people died from violence, famine or disease di ...

, the French King Henry III was mortally wounded with a dagger by Jacques Clément

Jacques Clément (1567 – 1 August 1589) was a French conspirator and the regicide of King Henry III.

Early life

He was born at Serbonnes, in today's Yonne '' département'', in Burgundy, and became a lay brother of the Third Order of S ...

, a fanatic member of the Catholic League of France. Nine years later, the Jesuit Juan de Mariana's 1599 ''On Kings and the Education of Kings'' (''De rege et regis institutione'') argued in support of tyrannicide

Tyrannicide is the killing or assassination of a tyrant or unjust ruler, purportedly for the common good, and usually by one of the tyrant's subjects. Tyrannicide was legally permitted and encouraged in Classical Athens. Often, the term "tyrant ...

. This work recounted the assassination of Henry III and argued for the legal right to overthrow a tyrant. Perhaps due in part to the publication of ''De rege'', until the 1620s, some English Catholics believed that regicide was justifiable to remove 'tyrants' from power. Much of the "rather nervous" political writing from James I was "concerned with the threat of Catholic assassination and refutation of the atholicargument that 'faith did not need to be kept with heretics'".

Early plots

In the absence of any sign that James would move to end the persecution of Catholics, as some had hoped for, several members of theclergy

Clergy are formal leaders within established religions. Their roles and functions vary in different religious traditions, but usually involve presiding over specific rituals and teaching their religion's doctrines and practices. Some of the ter ...

(including two anti-Jesuit priests) decided to take matters into their own hands. In what became known as the Bye Plot

The Bye Plot of 1603 was a conspiracy, by Priesthood (Catholic Church), Roman Catholic priests and Puritans aiming at toleration, tolerance for their respective denominations, to kidnap the new English king, James I of England. It is referred to ...

, the priests William Watson and William Clark planned to kidnap James and hold him in the Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic citadel and castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London, England. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamle ...

until he agreed to be more tolerant towards Catholics. Cecil received news of the plot from several sources, including the Archpriest

The ecclesiastical title of archpriest or archpresbyter belongs to certain priests with supervisory duties over a number of parishes. The term is most often used in Eastern Orthodoxy and the Eastern Catholic Churches and may be somewhat analogo ...

George Blackwell, who instructed his priests to have no part in any such schemes. At about the same time, Lord Cobham, Lord Grey de Wilton, Griffin Markham and Walter Raleigh

Sir Walter Raleigh (; – 29 October 1618) was an English statesman, soldier, writer and explorer. One of the most notable figures of the Elizabethan era, he played a leading part in English colonisation of North America, suppressed rebell ...

hatched what became known as the Main Plot, which involved removing James and his family and supplanting them with Arbella Stuart. Amongst others, they approached Philip III of Spain for funding, but were unsuccessful. All those involved in both plots were arrested in July and tried in autumn 1603. George Brooke was executed, but James—keen not to have too bloody a start to his reign—reprieved Cobham, Grey, and Markham while they were at the scaffold. Raleigh, who had watched while his colleagues sweated, had been due to be executed a few days later, but was also pardoned. Arbella Stuart denied any knowledge of the Main Plot. However, the two priests, Watson and Clark—condemned and "very bloodily handled"—were executed.

The Catholic community responded to news of these plots with shock. That the Bye Plot had been revealed by Catholics was instrumental in saving them from further persecution, and James was grateful enough to allow pardons for those recusants who sued for them, as well as postponing payment of their fines for a year.

On 19 February 1604, shortly after he discovered that his wife, Queen Anne, had been sent a rosary

The Rosary (; , in the sense of "crown of roses" or "garland of roses"), formally known as the Psalter of Jesus and Mary (Latin: Psalterium Jesu et Mariae), also known as the Dominican Rosary (as distinct from other forms of rosary such as the ...

from the pope via one of James's spies, Sir Anthony Standen, James denounced the Catholic Church. Three days later, he ordered all Jesuits and all other Catholic priests to leave the country, and reimposed the collection of fines for recusancy.

James changed his focus from the anxieties of English Catholics to the establishment of an Anglo-Scottish union. He also appointed Scottish nobles such as George Home to his court, which proved unpopular with the Parliament of England

The Parliament of England was the legislature of the Kingdom of England from the 13th century until 1707 when it was replaced by the Parliament of Great Britain. Parliament evolved from the Great Council of England, great council of Lords Spi ...

. Some Members of Parliament made it clear that, in their view, the "effluxion of people from the Northern parts" was unwelcome, and compared them to "plants which are transported from barren ground into a more fertile one". Even more discontent resulted when the King allowed his Scottish nobles to collect the recusancy fines. There were 5,560 convicted of recusancy in 1605, of whom 112 were landowners. The very few Catholics of great wealth who refused to attend services at their parish church were fined £20 per month. Those of more moderate means had to pay two-thirds of their annual rental income; middle class recusants were fined one shilling

The shilling is a historical coin, and the name of a unit of modern currency, currencies formerly used in the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, other British Commonwealth countries and Ireland, where they were generally equivalent to 1 ...

a week, although the collection of all these fines was "haphazard and negligent". When James came to power, almost £5,000 a year (equivalent to almost £12 million in 2020) was being raised by these fines.

On 19 March, the King gave his opening speech to his first English Parliament in which he spoke of his desire to secure peace, but only by "profession of the true religion". He also spoke of a Christian union and reiterated his desire to avoid religious persecution. For the Catholics, the King's speech made it clear that they were not to "increase their number and strength in this Kingdom", that "they might be in hope to erect their Religion again". To John Gerard, these words were almost certainly responsible for the heightened levels of persecution the members of his faith now suffered, and for the priest Oswald Tesimond, they were a repudiation of the early claims that the King had made, upon which the papists had built their hopes. A week after James's speech, Edmund, Lord Sheffield, informed the king of over 900 recusants brought before the Assizes

The assizes (), or courts of assize, were periodic courts held around England and Wales until 1972, when together with the quarter sessions they were abolished by the Courts Act 1971 and replaced by a single permanent Crown Court. The assizes ex ...

in Normanby, and on 24 April, the Popish Recusants Act 1605 was introduced in Parliament which threatened to outlaw all English followers of the Catholic Church.

Plot

The conspirators' principal aim was to kill King James, but many other important targets would also be present at the State Opening of Parliament, including the monarch's nearest relatives and members of the Privy Council. The senior judges of the English legal system, most of the Protestant aristocracy, and the bishops of the Church of England would all have attended in their capacity as members of the House of Lords, along with the members of the

The conspirators' principal aim was to kill King James, but many other important targets would also be present at the State Opening of Parliament, including the monarch's nearest relatives and members of the Privy Council. The senior judges of the English legal system, most of the Protestant aristocracy, and the bishops of the Church of England would all have attended in their capacity as members of the House of Lords, along with the members of the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the Bicameralism, bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of ...

. Another important objective was the kidnapping of the King's daughter, Elizabeth. Housed at Coombe Abbey near Coventry

Coventry ( or rarely ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and metropolitan borough in the West Midlands (county), West Midlands county, in England, on the River Sherbourne. Coventry had been a large settlement for centurie ...

, she lived only ten miles north of Warwick—convenient for the plotters, most of whom lived in the Midlands. Once the King and his Parliament were dead, the plotters intended to install Elizabeth on the English throne as a titular Queen. The fate of her brothers, Henry and Charles, would be improvised; their role in state ceremonies was, as yet, uncertain. The plotters planned to use Henry Percy, 9th Earl of Northumberland, as Elizabeth's regent

In a monarchy, a regent () is a person appointed to govern a state because the actual monarch is a minor, absent, incapacitated or unable to discharge their powers and duties, or the throne is vacant and a new monarch has not yet been dete ...

, but most likely never informed him of this.

Initial recruitment

Robert Catesby (1573–1605), a man of "ancient, historic and distinguished lineage", was the inspiration behind the plot. He was described by contemporaries as "a good-looking man, about six feet tall, athletic and a good swordsman". Along with several other conspirators, he took part in the Essex Rebellion in 1601, during which he was wounded and captured. Queen Elizabeth allowed him to escape with his life after fining him 4,000marks

Marks may refer to:

Business

* Mark's, a Canadian retail chain

* Marks & Spencer, a British retail chain

* Collective trade marks

A collective trademark, collective trade mark, or collective mark is a trademark owned by an organization (such ...

(equivalent to more than £6 million in 2008), after which he sold his estate in Chastleton.

In 1603, Catesby helped to organise a mission to the new king of Spain, Philip III, urging Philip to launch an invasion attempt on England, which they assured him would be well supported, particularly by the English Catholics. Thomas Wintour (1571–1606) was chosen as the emissary, but the Spanish king, although sympathetic to the plight of Catholics in England, was intent on making peace with James. Wintour had also attempted to convince the Spanish envoy Don Juan de Tassis that "3,000 Catholics" were ready and waiting to support such an invasion. Concern was voiced by Pope Clement VIII

Pope Clement VIII (; ; 24 February 1536 – 3 March 1605), born Ippolito Aldobrandini, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 30 January 1592 to his death in March 1605.

Born in Fano, Papal States to a prominen ...

that using violence to achieve a restoration of Catholic power in England would result in the destruction of those that remained.

According to contemporary accounts, in February 1604, Catesby invited Thomas Wintour to his house in Lambeth

Lambeth () is a district in South London, England, which today also gives its name to the (much larger) London Borough of Lambeth. Lambeth itself was an ancient parish in the county of Surrey. It is situated 1 mile (1.6 km) south of Charin ...

, where they discussed Catesby's plan to re-establish Catholicism in England by blowing up the House of Lords during the State Opening of Parliament. Wintour was known as a competent scholar, able to speak several languages, and he had fought with the English army in the Netherlands. His uncle, Francis Ingleby, had been executed for being a Catholic priest in 1586, and Wintour later converted to Catholicism. Also present at the meeting was John Wright, a devout Catholic said to be one of the best swordsmen of his day, and a man who had taken part with Catesby in the Earl of Essex's rebellion three years earlier. Despite his reservations over the possible repercussions should the attempt fail, Wintour agreed to join the conspiracy, perhaps persuaded by Catesby's rhetoric: "Let us give the attempt and where it faileth, pass no further."

Wintour travelled to Flanders

Flanders ( or ; ) is the Dutch language, Dutch-speaking northern portion of Belgium and one of the communities, regions and language areas of Belgium. However, there are several overlapping definitions, including ones related to culture, la ...

to enquire about Spanish support. While there, he sought out Guy Fawkes (1570–1606), a committed Catholic who had served as a soldier in the Southern Netherlands under the command of William Stanley, and in 1603 had been recommended for a captaincy. Accompanied by John Wright's brother Christopher, Fawkes had also been a member of the 1603 delegation to the Spanish court pleading for an invasion of England. Wintour told Fawkes that "", and that certain gentlemen "". The two men returned to England late in April 1604, telling Catesby that Spanish support was unlikely. Thomas Percy, Catesby's friend and John Wright's brother-in-law, was introduced to the plot several weeks later.

Percy had found employment with his kinsman the Earl of Northumberland, and by 1596, was his agent for the family's northern estates. About 1600–1601 he served with his patron in the Low Countries

The Low Countries (; ), historically also known as the Netherlands (), is a coastal lowland region in Northwestern Europe forming the lower Drainage basin, basin of the Rhine–Meuse–Scheldt delta and consisting today of the three modern "Bene ...

. At some point during Northumberland's command in the Low Countries, Percy became his agent in his communications with James I. Percy was reputedly a "serious" character who had converted to the Catholic faith. His early years were, according to a Catholic source, marked by a tendency to rely on "his sword and personal courage". Northumberland, although not a Catholic himself, planned to build a strong relationship with James I in order to better the prospects of English Catholics, and to reduce the family disgrace caused by his separation from his wife Martha Wright, a favourite of Elizabeth I.

Thomas Percy's meetings with James seemed to go well. Percy returned with promises of support for the Catholics, and Northumberland believed that James would go so far as to allow Mass

Mass is an Intrinsic and extrinsic properties, intrinsic property of a physical body, body. It was traditionally believed to be related to the physical quantity, quantity of matter in a body, until the discovery of the atom and particle physi ...

in private houses, so as not to cause public offence. Percy, keen to improve his standing, went even further, claiming that the future king would guarantee the safety of English Catholics.

Initial planning

The first meeting between the five conspirators took place on 20 May 1604, probably at the Duck and Drake Inn, just off the Strand, Thomas Wintour's usual residence when staying in London. Catesby, Thomas Wintour, and John Wright were in attendance, joined by Guy Fawkes and Thomas Percy. Alone in a private room, the five plotters swore an oath of secrecy on a prayer book. By coincidence, and ignorant of the plot, John Gerard (a friend of Catesby's) was celebrating Mass in another room, and the five men subsequently received theEucharist

The Eucharist ( ; from , ), also called Holy Communion, the Blessed Sacrament or the Lord's Supper, is a Christianity, Christian Rite (Christianity), rite, considered a sacrament in most churches and an Ordinance (Christianity), ordinance in ...

.

Further recruitment

The adjournment of Parliament gave the conspirators, they thought, until February 1605 to finalise their plans. On 9 June 1604, Percy's patron, the Earl of Northumberland, appointed him to the Band of Gentlemen Pensioners, a mounted troop of 50 bodyguards to the King. This role gave Percy reason to seek a base in London, and a small property near the Prince's Chamber owned by Henry Ferrers, a tenant of John Whynniard, was chosen. Percy arranged for the use of the house through Northumberland's agents, Dudley Carleton and John Hippisley. Fawkes, using the pseudonym "John Johnson", took charge of the building, posing as Percy's servant. The building was occupied by Scottish commissioners appointed by the King to consider his plans for the unification of England and Scotland, so the plotters hired Catesby's lodgings in Lambeth, on the opposite bank of the Thames, from where their stored gunpowder and other supplies could be conveniently rowed across each night. Meanwhile, King James I continued with his policies against the Catholics, and Parliament pushed through anti-Catholic legislation, until its adjournment on 7 July. Following their oath, the plotters left London and returned to their homes.

The conspirators returned to London in October 1604, when Robert Keyes, a "desperate man, ruined and indebted", was admitted to the group. His responsibility was to take charge of Catesby's house in Lambeth, where the gunpowder and other supplies were to be stored. Keyes's family had notable connections; his wife's employer was the Catholic Lord Mordaunt. He was tall, with a red beard, and was seen as trustworthy and—like Fawkes—capable of looking after himself. In December Catesby recruited his servant, Thomas Bates, into the plot, after the latter accidentally became aware of it.

It was announced on 24 December 1604 that the scheduled February re-opening of Parliament would be delayed. Concern over the plague meant that rather than sitting in February, as the plotters had originally planned for, Parliament would not sit again until 3 October 1605. The contemporaneous account of the prosecution claimed that during this delay the conspirators were digging a tunnel beneath Parliament. This may have been a government fabrication, as no evidence for the existence of a tunnel was presented by the prosecution, and no trace of one has ever been found. The account of a tunnel comes directly from Thomas Wintour's confession, and Guy Fawkes did not admit the existence of such a scheme until his fifth interrogation. Logistically, digging a tunnel would have proved extremely difficult, especially as none of the conspirators had any experience of mining. If the story is true, by 6 December 1604 the Scottish commissioners had finished their work, and the conspirators were busy tunnelling from their rented house to the House of Lords. They ceased their efforts when, during tunnelling, they heard a noise from above. The noise turned out to be the then-tenant's widow, who was clearing out the

Following their oath, the plotters left London and returned to their homes.

The conspirators returned to London in October 1604, when Robert Keyes, a "desperate man, ruined and indebted", was admitted to the group. His responsibility was to take charge of Catesby's house in Lambeth, where the gunpowder and other supplies were to be stored. Keyes's family had notable connections; his wife's employer was the Catholic Lord Mordaunt. He was tall, with a red beard, and was seen as trustworthy and—like Fawkes—capable of looking after himself. In December Catesby recruited his servant, Thomas Bates, into the plot, after the latter accidentally became aware of it.

It was announced on 24 December 1604 that the scheduled February re-opening of Parliament would be delayed. Concern over the plague meant that rather than sitting in February, as the plotters had originally planned for, Parliament would not sit again until 3 October 1605. The contemporaneous account of the prosecution claimed that during this delay the conspirators were digging a tunnel beneath Parliament. This may have been a government fabrication, as no evidence for the existence of a tunnel was presented by the prosecution, and no trace of one has ever been found. The account of a tunnel comes directly from Thomas Wintour's confession, and Guy Fawkes did not admit the existence of such a scheme until his fifth interrogation. Logistically, digging a tunnel would have proved extremely difficult, especially as none of the conspirators had any experience of mining. If the story is true, by 6 December 1604 the Scottish commissioners had finished their work, and the conspirators were busy tunnelling from their rented house to the House of Lords. They ceased their efforts when, during tunnelling, they heard a noise from above. The noise turned out to be the then-tenant's widow, who was clearing out the undercroft

An undercroft is traditionally a cellar or storage room, often brick-lined and Vault (architecture), vaulted, and used for storage in buildings since medieval times. In modern usage, an undercroft is generally a ground (street-level) area whi ...

directly beneath the House of Lords—the room where the plotters eventually stored the gunpowder.

By the time the plotters reconvened at the start of the old style

Old Style (O.S.) and New Style (N.S.) indicate dating systems before and after a calendar change, respectively. Usually, they refer to the change from the Julian calendar to the Gregorian calendar as enacted in various European countries betwe ...

new year on Lady Day

In the Western liturgical year, Lady Day is the common name in some English-speaking and Scandinavian countries of the Feast of the Annunciation, celebrated on 25 March to commemorate the annunciation of the archangel Gabriel to the Virgin Mar ...

, 25 March 1605, three more had been admitted to their ranks; Robert Wintour, John Grant, and Christopher Wright. The additions of Wintour and Wright were obvious choices. Along with a small fortune, Robert Wintour inherited Huddington Court (a known refuge for priests) near Worcester, and was reputedly a generous and well-liked man. A devout Catholic, he married Gertrude, the daughter of John Talbot of Grafton, from a prominent Worcestershire family of recusants. Christopher Wright (1568–1605), John's brother, had also taken part in the Earl of Essex's revolt and had moved his family to Twigmore in Lincolnshire

Lincolnshire (), abbreviated ''Lincs'', is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the East Midlands and Yorkshire and the Humber regions of England. It is bordered by the East Riding of Yorkshire across the Humber estuary to th ...

, then known as something of a haven for priests. John Grant was married to Wintour's sister, Dorothy, and was lord of the manor

Lord of the manor is a title that, in Anglo-Saxon England and Norman England, referred to the landholder of a historical rural estate. The titles date to the English Feudalism, feudal (specifically English feudal barony, baronial) system. The ...

of Norbrook near Stratford-upon-Avon

Stratford-upon-Avon ( ), commonly known as Stratford, is a market town and civil parish in the Stratford-on-Avon (district), Stratford-on-Avon district, in the county of Warwickshire, in the West Midlands (region), West Midlands region of Engl ...

. Reputed to be an intelligent, thoughtful man, he sheltered Catholics at his home at Snitterfield, and was another who had been involved in the Essex revolt of 1601.

Undercroft

In addition, 25 March was the day on which the plotters purchased the lease to theundercroft

An undercroft is traditionally a cellar or storage room, often brick-lined and Vault (architecture), vaulted, and used for storage in buildings since medieval times. In modern usage, an undercroft is generally a ground (street-level) area whi ...

they had supposedly tunnelled near to, owned by John Whynniard. The Palace of Westminster

The Palace of Westminster is the meeting place of the Parliament of the United Kingdom and is located in London, England. It is commonly called the Houses of Parliament after the House of Commons and the House of Lords, the two legislative ch ...

in the early 17th century was a warren of buildings clustered around the medieval chambers, chapels, and halls of the former royal palace that housed both Parliament and the various royal law courts. The old palace was easily accessible; merchants, lawyers, and others lived and worked in the lodgings, shops and taverns within its precincts. Whynniard's building was along a right-angle to the House of Lords, alongside a passageway called Parliament Place, which itself led to Parliament Stairs and the River Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the The Isis, River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the Longest rivers of the United Kingdom, s ...

. Undercrofts were common features at the time, used to house a variety of materials including food and firewood. Whynniard's undercroft, on the ground floor, was directly beneath the first-floor House of Lords, and may once have been part of the palace's medieval kitchen. Unused and filthy, its location was ideal for what the group planned to do.

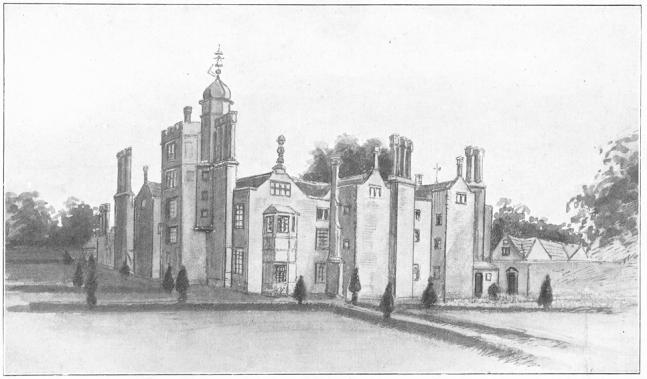

In the second week of June, Catesby met in London the principal

In the second week of June, Catesby met in London the principal Jesuit

The Society of Jesus (; abbreviation: S.J. or SJ), also known as the Jesuit Order or the Jesuits ( ; ), is a religious order (Catholic), religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rom ...

in England, Henry Garnet, and asked him about the morality of entering into an undertaking which might involve the destruction of the innocent, together with the guilty. Garnet answered that such actions could often be excused, but according to his own account later admonished Catesby during a second meeting in July in Essex, showing him a letter from the pope which forbade rebellion. Soon after, the Jesuit priest Oswald Tesimond told Garnet he had taken Catesby's confession, in the course of which he had learnt of the plot. Garnet and Catesby met for a third time on 24 July 1605, at the house of the wealthy Catholic Anne Vaux in Enfield Chase. Garnet decided that Tesimond's account had been given under the seal of the confessional, and that canon law therefore forbade him to repeat what he had heard. Without acknowledging that he was aware of the precise nature of the plot, Garnet attempted to dissuade Catesby from his course, to no avail. Garnet wrote to a colleague in Rome, Claudio Acquaviva

Claudio Acquaviva, SJ (14 September 1543 – 31 January 1615) was an Italian Jesuit priest. Elected in 1581 as the fifth Superior General of the Society of Jesus, he has been referred to as the second founder of the Jesuit order.

Early life and ...

, expressing his concerns about open rebellion in England. He also told Acquaviva that "there is a risk that some private endeavour may commit treason or use force against the King", and urged the pope to issue a public brief against the use of force.

According to Fawkes, 20 barrels of gunpowder were brought in at first, followed by 16 more on 20 July. The supply of gunpowder was theoretically controlled by the government, but it was easily obtained from illicit sources. On 28 July, the ever-present threat of the plague again delayed the opening of Parliament, this time until Tuesday 5 November. Fawkes left the country for a short time. The King, meanwhile, spent much of the summer away from the city, hunting. He stayed wherever was convenient, including on occasion at the houses of prominent Catholics. Garnet, convinced that the threat of an uprising had receded, travelled the country on a pilgrimage

A pilgrimage is a travel, journey to a holy place, which can lead to a personal transformation, after which the pilgrim returns to their daily life. A pilgrim (from the Latin ''peregrinus'') is a traveler (literally one who has come from afar) w ...

.

It is uncertain when Fawkes returned to England, but he was back in London by late August, when he and Wintour discovered that the gunpowder stored in the undercroft had decayed. More gunpowder was brought into the room, along with firewood to conceal it. The final three conspirators were recruited in late 1605. At Michaelmas

Michaelmas ( ; also known as the Feast of Saints Michael, Gabriel, and Raphael, the Feast of the Archangels, or the Feast of Saint Michael and All Angels) is a Christian festival observed in many Western Christian liturgical calendars on 29 Se ...

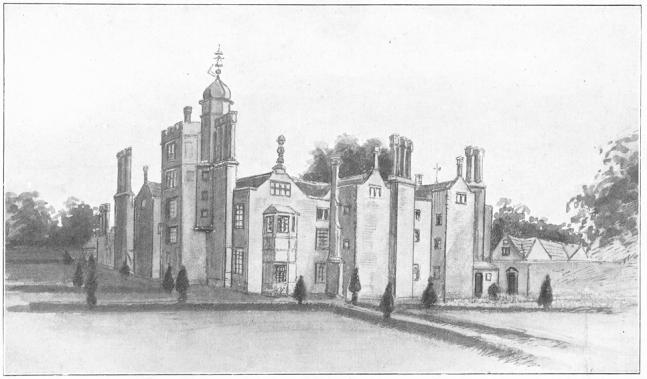

, Catesby persuaded the staunchly Catholic Ambrose Rookwood to rent Clopton House

Clopton House is a 17th-century country mansion near Stratford upon Avon, Warwickshire, now converted into residential apartments. It is a Grade II* listed building.

History

The Manor of Clopton was granted to the eponymous family in the 13th ce ...

near Stratford-upon-Avon. Rookwood was a young man with recusant connections, whose stable of horses at Coldham Hall in Stanningfield, Suffolk

Suffolk ( ) is a ceremonial county in the East of England and East Anglia. It is bordered by Norfolk to the north, the North Sea to the east, Essex to the south, and Cambridgeshire to the west. Ipswich is the largest settlement and the county ...

was an important factor in his enlistment. His parents, Robert Rookwood and Dorothea Drury, were wealthy landowners, and had educated their son at a Jesuit school near Calais

Calais ( , , traditionally , ) is a French port city in the Pas-de-Calais department, of which it is a subprefecture. Calais is the largest city in Pas-de-Calais. The population of the city proper is 67,544; that of the urban area is 144,6 ...

. Everard Digby was a young man who was generally well liked, and lived at Gayhurst House in Buckinghamshire

Buckinghamshire (, abbreviated ''Bucks'') is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South East England and one of the home counties. It is bordered by Northamptonshire to the north, Bedfordshire to the north-east, Hertfordshir ...

. He had been knighted by the King in April 1603, and was converted to Catholicism by Gerard. Digby and his wife, Mary Mulshaw, had accompanied the priest on his pilgrimage, and the two men were reportedly close friends. Digby was asked by Catesby to rent Coughton Court near Alcester

Alcester ( ) is a market town and civil parishes in England, civil parish in the Stratford-on-Avon District in Warwickshire, England. It is west of Stratford-upon-Avon, and 7 miles south of Redditch. The town dates back to the times of Roman ...

. Digby also promised £1,500 after Percy failed to pay the rent due for the properties he had taken in Westminster. Finally, on 14 October Catesby invited Francis Tresham into the conspiracy. Tresham was the son of the Catholic Thomas Tresham, and a cousin to Robert Catesby; the two had been raised together. He was also the heir to his father's large fortune, which had been depleted by recusant fines, expensive tastes, and by Francis and Catesby's involvement in the Essex revolt.

Catesby and Tresham met at the home of Tresham's brother-in-law and cousin, Lord Stourton. In his confession, Tresham claimed that he had asked Catesby if the plot would damn their souls, to which Catesby had replied it would not, and that the plight of England's Catholics required that it be done. Catesby also apparently asked for £2,000, and the use of Rushton Hall in Northamptonshire

Northamptonshire ( ; abbreviated Northants.) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the East Midlands of England. It is bordered by Leicestershire, Rutland and Lincolnshire to the north, Cambridgeshire to the east, Bedfordshi ...

. Tresham declined both offers (although he did give £100 to Thomas Wintour), and told his interrogators that he had moved his family from Rushton to London in advance of the plot; hardly the actions of a guilty man, he claimed.

Monteagle letter

The details of the plot were finalised in October, in a series of taverns across London and

The details of the plot were finalised in October, in a series of taverns across London and Daventry

Daventry ( , ) is a market town and civil parish in the West Northamptonshire unitary authority area of Northamptonshire, England, close to the border with Warwickshire. At the 2021 United Kingdom census, 2021 Census, Daventry had a populati ...

. Fawkes would be left to light the fuse and then escape across the Thames, while simultaneously a revolt in the Midlands would help to ensure the capture of the King's daughter, Elizabeth. Fawkes would leave for the continent, to explain events in England to the European Catholic powers.

The wives of those involved and Anne Vaux (a friend of Garnet who often shielded priests at her home) became increasingly concerned by what they suspected was about to happen. Several of the conspirators expressed worries about the safety of fellow Catholics who would be present in Parliament on the day of the planned explosion. Percy was concerned for his patron, Northumberland, and the young Earl of Arundel

Earl of Arundel is a title of nobility in England, and one of the oldest extant in the English peerage. It is currently held by the Duke of Norfolk, and it is used (along with the earldom of Surrey) by his heir apparent as a courtesy title ...

's name was brought up; Catesby suggested that a minor wound might keep him from the chamber on that day. The Lords Vaux, Montagu, Monteagle, and Stourton were also mentioned. Keyes suggested warning Lord Mordaunt, his wife's employer, to derision from Catesby.

On Saturday 26 October, Monteagle (Tresham's brother-in-law) arranged a meal in a long-disused house at Hoxton

Hoxton is an area in the London Borough of Hackney, England. It was Historic counties of England, historically in the county of Middlesex until 1889. Hoxton lies north-east of the City of London, is considered to be a part of London's East End ...

. Suddenly a servant appeared saying he had been handed a letter for Lord Monteagle from a stranger in the road. Monteagle ordered it to be read aloud to the company.

Uncertain of the letter's meaning, Monteagle promptly rode to Whitehall

Whitehall is a road and area in the City of Westminster, Central London, England. The road forms the first part of the A roads in Zone 3 of the Great Britain numbering scheme, A3212 road from Trafalgar Square to Chelsea, London, Chelsea. It ...

and handed it to Cecil (then Earl of Salisbury). Salisbury informed the Earl of Worcester, considered to have recusant sympathies, and the suspected Catholic Henry Howard, 1st Earl of Northampton, but kept news of the plot from the King, who was busy hunting in Cambridgeshire

Cambridgeshire (abbreviated Cambs.) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the East of England and East Anglia. It is bordered by Lincolnshire to the north, Norfolk to the north-east, Suffolk to the east, Essex and Hertfor ...

and not expected back for several days. Monteagle's servant, Thomas Ward, had family connections with the Wright brothers, and sent a message to Catesby about the betrayal. Catesby, who had been due to go hunting with the King, suspected that Tresham was responsible for the letter, and with Thomas Wintour confronted the recently recruited conspirator. Tresham managed to convince the pair that he had not written the letter, but urged them to abandon the plot. Salisbury was already aware of certain stirrings before he received the letter, but did not yet know the exact nature of the plot, or who exactly was involved. He therefore elected to wait, to see how events unfolded.

Discovery

The letter was shown to the King on the first of November following his arrival back in London. Upon reading it, James immediately seized upon the word "blow" and felt that it hinted at "some strategem of fire and powder", perhaps an explosion exceeding in violence the one that killed his father, Lord Darnley, at Kirk o' Field in 1567. Keen not to seem too intriguing, and wanting to allow the King to take the credit for unveiling the conspiracy, Salisbury feigned ignorance. The following day members of the Privy Council visited the King at thePalace of Whitehall

The Palace of Whitehall – also spelled White Hall – at Westminster was the main residence of the English monarchs from 1530 until 1698, when most of its structures, with the notable exception of Inigo Jones's Banqueting House of 1622, ...

and informed him that, based on the information that Salisbury had given them a week earlier, on Monday the Lord Chamberlain Thomas Howard, 1st Earl of Suffolk would undertake a search of the Houses of Parliament, "both above and below". On Sunday 3 November, Percy, Catesby and Wintour had a final meeting, where Percy told his colleagues that they should "abide the uttermost triall", and reminded them of their ship waiting at anchor on the Thames.

By 4 November, Digby was ensconced with a "hunting party" at Dunchurch, ready to abduct Elizabeth. The same day, Percy visited the Earl of Northumberland—who was uninvolved in the conspiracy—to see if he could discern what rumours surrounded the letter to Monteagle. Percy returned to London and assured Wintour, John Wright, and Robert Keyes that they had nothing to be concerned about, and returned to his lodgings on Gray's Inn Road. That same evening Catesby, likely accompanied by John Wright and Bates, set off for the Midlands. Fawkes visited Keyes, and was given a pocket watch left by Percy, to time the fuse, and an hour later Rookwood received several engraved swords from a local cutler.

Although two accounts of the number of searches and their timing exist, according to the King's version, the first search of the buildings in and around Parliament was made on Monday 4 November—as the plotters were busy making their final preparations—by Suffolk, Monteagle, and John Whynniard. They found a large pile of firewood in the undercroft beneath the House of Lords, accompanied by what they presumed to be a serving man (Fawkes), who told them that the firewood belonged to his master, Thomas Percy. They left to report their findings, at which time Fawkes also left the building. The mention of Percy's name aroused further suspicion as he was already known to the authorities as a Catholic agitator. The King insisted that a more thorough search be undertaken. Late that night, the search party, headed by Thomas Knyvet, returned to the undercroft. They again found Fawkes, dressed in a cloak and hat, and wearing boots and spurs. He was arrested, whereupon he gave his name as John Johnson. He was carrying a lantern now held in the

Although two accounts of the number of searches and their timing exist, according to the King's version, the first search of the buildings in and around Parliament was made on Monday 4 November—as the plotters were busy making their final preparations—by Suffolk, Monteagle, and John Whynniard. They found a large pile of firewood in the undercroft beneath the House of Lords, accompanied by what they presumed to be a serving man (Fawkes), who told them that the firewood belonged to his master, Thomas Percy. They left to report their findings, at which time Fawkes also left the building. The mention of Percy's name aroused further suspicion as he was already known to the authorities as a Catholic agitator. The King insisted that a more thorough search be undertaken. Late that night, the search party, headed by Thomas Knyvet, returned to the undercroft. They again found Fawkes, dressed in a cloak and hat, and wearing boots and spurs. He was arrested, whereupon he gave his name as John Johnson. He was carrying a lantern now held in the Ashmolean Museum

The Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology () on Beaumont Street in Oxford, England, is Britain's first public museum. Its first building was erected in 1678–1683 to house the cabinet of curiosities that Elias Ashmole gave to the University ...

, Oxford

Oxford () is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and non-metropolitan district in Oxfordshire, England, of which it is the county town.

The city is home to the University of Oxford, the List of oldest universities in continuou ...

, and a search of his person revealed a pocket watch, several slow match

Slow match, also called match cord, is the slow-burning cord or twine fuse used by early gunpowder musketeers, artillerymen, and soldiers to ignite matchlock muskets, cannons, shells, and petards. Slow matches were most suitable for use ar ...

es and touchwood. Thirty-six barrels of gunpowder were discovered hidden under piles of faggots and coal. Fawkes was taken to the King early on the morning of 5 November.

Flight

As news of "John Johnson's" arrest spread among the plotters still in London, most fled northwest, along Watling Street. Christopher Wright and Thomas Percy left together. Rookwood left soon after, and managed to cover 30 miles in two hours on one horse. He overtook Keyes, who had set off earlier, then Wright and Percy at Little Brickhill, before catching Catesby, John Wright, and Bates on the same road. Reunited, the group continued northwest to Dunchurch, using horses provided by Digby. Keyes went to Mordaunt's house at Drayton. Meanwhile, Thomas Wintour stayed in London, and even went to Westminster to see what was happening. When he realised the plot had been uncovered, he took his horse and made for his sister's house at Norbrook, before continuing to Huddington Court. The group of six conspirators stopped at Ashby St Ledgers at about 6 pm, where they met Robert Wintour and updated him on their situation. They then continued on to Dunchurch, and met with Digby. Catesby convinced him that despite the plot's failure, an armed struggle was still a real possibility. He announced to Digby's "hunting party" that the King and Salisbury were dead, before the fugitives moved west to Warwick. In London, news of the plot was spreading, and the authorities set extra guards on the city gates, closed the ports, and protected the house of the Spanish Ambassador, which was surrounded by an angry mob. An arrest warrant was issued against Thomas Percy, and his patron, the Earl of Northumberland, was placed under house arrest. In "John Johnson's" initial interrogation he revealed nothing other than the name of his mother, and that he was fromYorkshire

Yorkshire ( ) is an area of Northern England which was History of Yorkshire, historically a county. Despite no longer being used for administration, Yorkshire retains a strong regional identity. The county was named after its county town, the ...

. A letter to Guy Fawkes was discovered on his person, but he claimed that name was one of his aliases. Far from denying his intentions, "Johnson" stated that it had been his purpose to destroy the King and Parliament. Nevertheless, he maintained his composure and insisted that he had acted alone. His unwillingness to yield so impressed the King that he described him as possessing "a Roman resolution".

Investigation

On 6 November, the Lord Chief Justice, Sir John Popham (a man with a deep-seated hatred of Catholics) questioned Rookwood's servants. By the evening he had learned the names of several of those involved in the conspiracy: Catesby, Rookwood, Keyes, Wynter, John and Christopher Wright, and Grant. "Johnson" meanwhile persisted with his story, and along with the gunpowder he was found with, was moved to the

On 6 November, the Lord Chief Justice, Sir John Popham (a man with a deep-seated hatred of Catholics) questioned Rookwood's servants. By the evening he had learned the names of several of those involved in the conspiracy: Catesby, Rookwood, Keyes, Wynter, John and Christopher Wright, and Grant. "Johnson" meanwhile persisted with his story, and along with the gunpowder he was found with, was moved to the Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic citadel and castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London, England. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamle ...

, where the King had decided that "Johnson" would be torture

Torture is the deliberate infliction of severe pain or suffering on a person for reasons including corporal punishment, punishment, forced confession, extracting a confession, interrogational torture, interrogation for information, or intimid ...

d. The use of torture was forbidden, except by royal prerogative or a body such as the Privy Council or Star Chamber

The court of Star Chamber () was an English court that sat at the royal Palace of Westminster, from the late to the mid-17th century (), and was composed of privy counsellors and common-law judges, to supplement the judicial activities of the ...

. In a letter of 6 November James wrote: "The gentler tortours orturesare to be first used unto him, nd thus by steps extended to the bottom depths and so God speed your good work." "Johnson" may have been placed in manacles and hung from the wall, but he was almost certainly subjected to the horrors of the rack. On 7 November his resolve was broken; he confessed late that day, and again over the following two days.

Last stand

On 6 November, with Fawkes maintaining his silence, the fugitives raided Warwick Castle for supplies, then continued to Norbrook to collect weapons. From there they continued their journey to Huddington. Bates left the group and travelled to Coughton Court to deliver a letter from Catesby, to Garnet and the other priests, informing them of what had transpired, and asking for their help in raising an army. Garnet replied by begging Catesby and his followers to stop their "wicked actions", before himself fleeing. Several priests set out for Warwick, worried about the fate of their colleagues. They were caught, and then imprisoned in London. Catesby and the others arrived at Huddington early in the afternoon, and were met by Thomas Wintour. They received practically no support or sympathy from those they met, including family members, who were terrified at the prospect of being associated with treason. They continued on to Holbeche House on the border ofStaffordshire

Staffordshire (; postal abbreviation ''Staffs''.) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the West Midlands (region), West Midlands of England. It borders Cheshire to the north-west, Derbyshire and Leicestershire to the east, ...

, the home of Stephen Littleton, a member of their ever-decreasing band of followers. Whilst there, Stephen Littleton and Thomas Wintour went to Pepperhill, the Shropshire

Shropshire (; abbreviated SalopAlso used officially as the name of the county from 1974–1980. The demonym for inhabitants of the county "Salopian" derives from this name.) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the West M ...

residence at Boningale of Robert Wintour's father-in-law John Talbot, to gain support, but to no avail. Tired and desperate, they spread out some of the now-soaked gunpowder in front of the fire, to dry out. Although gunpowder does not explode unless physically contained, a spark from the fire landed on the powder and the resultant flames engulfed Catesby, Rookwood, Grant, and a man named Morgan, who was a member of the hunting party.

Thomas Wintour and Littleton, on their way from Huddington to Holbeche House, were told by a messenger that Catesby had died. At that point, Littleton left, but Thomas arrived at the house to find Catesby alive, albeit scorched. John Grant was not so lucky, and had been blinded by the fire. Digby, Robert Wintour and his half-brother John, and Thomas Bates, had all left. Of the plotters, only the singed figures of Catesby and Grant, the Wright brothers, Rookwood, and Percy remained. The fugitives resolved to stay in the house and wait for the arrival of the King's men.

Richard Walsh ( Sheriff of Worcestershire) and his company of 200 men besieged Holbeche House on the morning of 8 November. Thomas Wintour was hit in the shoulder while crossing the courtyard. John Wright was shot, followed by his brother, and then Rookwood. Catesby and Percy were reportedly killed by a single lucky shot. The attackers rushed the property, and stripped the dead or dying defenders of their clothing. Grant, Morgan, Rookwood, and Wintour were arrested.

Reaction