Gromyko Commission on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Gromyko Commission, officially titled the State Commission for Consideration of Issues Raised in Applications of Citizens of the USSR from Among the Crimean Tatars () was the first state commission on the subject of addressing what the dubbed "the Tatar problem". Formed in July 1987 and led by Andrey Gromyko, it issued a conclusion in June 1988 rejecting all major demands of Crimean Tatar civil rights activists ranging from

The Gromyko Commission, officially titled the State Commission for Consideration of Issues Raised in Applications of Citizens of the USSR from Among the Crimean Tatars () was the first state commission on the subject of addressing what the dubbed "the Tatar problem". Formed in July 1987 and led by Andrey Gromyko, it issued a conclusion in June 1988 rejecting all major demands of Crimean Tatar civil rights activists ranging from

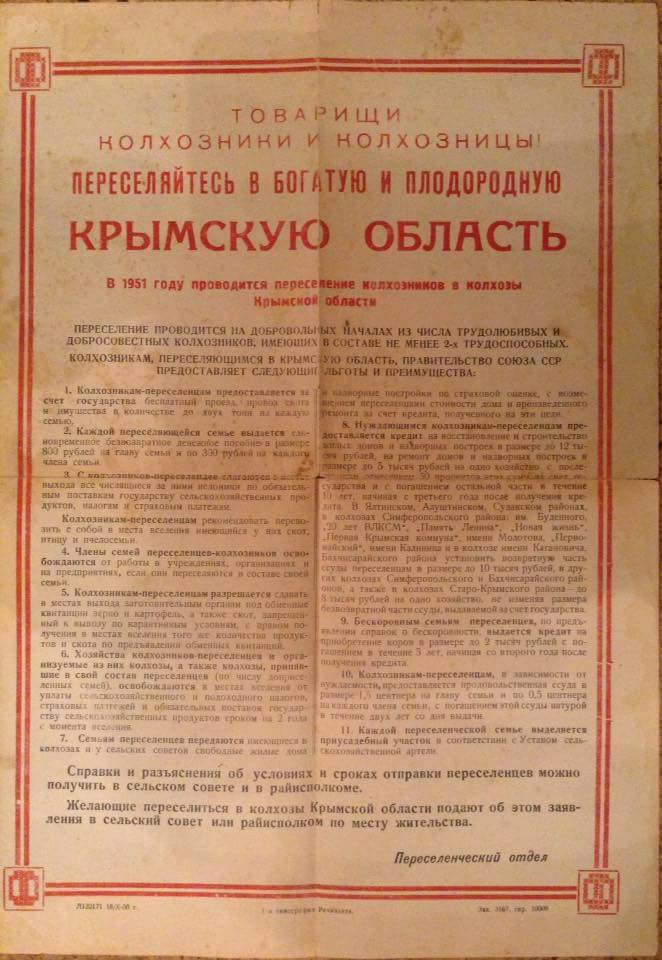

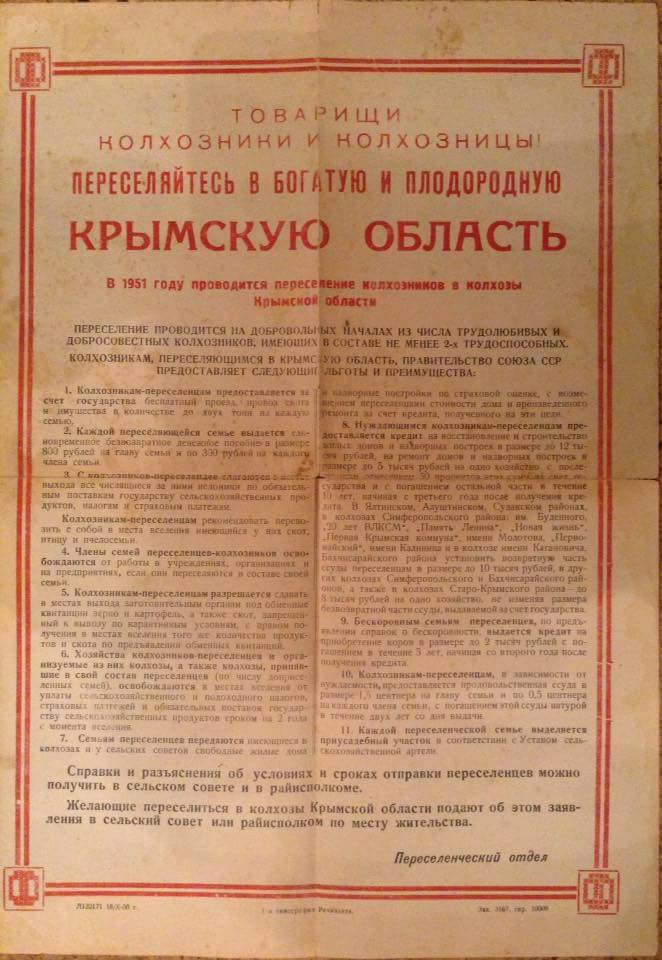

When pressed on the issue by foreign journalists, the government insisted that Crimean Tatars had equal rights and but that most simply did not want to return to Crimea and had "taken root" in places of exile. However, when Crimean Tatars tried to move to Crimea, they were almost always denied the required propiska (residence permit) and subject to re-deportation, while slavic migrants to Crimea faced no such barriers to getting permission to live in Crimea and were frequently encouraged to move there. While Crimean Tatars were told that Crimea was already overpopulated as an excuse for not letting them return, even though newspapers frequently advertised the need for more workers in Crimea.

In the

When pressed on the issue by foreign journalists, the government insisted that Crimean Tatars had equal rights and but that most simply did not want to return to Crimea and had "taken root" in places of exile. However, when Crimean Tatars tried to move to Crimea, they were almost always denied the required propiska (residence permit) and subject to re-deportation, while slavic migrants to Crimea faced no such barriers to getting permission to live in Crimea and were frequently encouraged to move there. While Crimean Tatars were told that Crimea was already overpopulated as an excuse for not letting them return, even though newspapers frequently advertised the need for more workers in Crimea.

In the

The Gromyko Commission, officially titled the State Commission for Consideration of Issues Raised in Applications of Citizens of the USSR from Among the Crimean Tatars () was the first state commission on the subject of addressing what the dubbed "the Tatar problem". Formed in July 1987 and led by Andrey Gromyko, it issued a conclusion in June 1988 rejecting all major demands of Crimean Tatar civil rights activists ranging from

The Gromyko Commission, officially titled the State Commission for Consideration of Issues Raised in Applications of Citizens of the USSR from Among the Crimean Tatars () was the first state commission on the subject of addressing what the dubbed "the Tatar problem". Formed in July 1987 and led by Andrey Gromyko, it issued a conclusion in June 1988 rejecting all major demands of Crimean Tatar civil rights activists ranging from right of return

The right of return is a principle in international law which guarantees everyone's right of return to, or re-entry to, their country of citizenship. The right of return is part of the broader human rights concept of freedom of movement and is al ...

to restoration of the Crimean ASSR.

Background

In May 1944 the Crimean Tatar people was deported from Crimea on blanket accusations of mass collaboration withNazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

. Most were sent to the Uzbek SSR

The Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic (, ), also known as Soviet Uzbekistan, the Uzbek SSR, UzSSR, or simply Uzbekistan and rarely Uzbekia, was a union republic of the Soviet Union. It was governed by the Uzbek branch of the Soviet Communist P ...

and scattered around various oblasts within the Uzbek SSR, but some were sent to other areas such as the Mari ASSR

The Mari Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (Mari ASSR) ( Mari: Марий Автоном Совет Социализм Республик, ''Mariy Avtonom Sovet Sotsializm Respublik'') was an autonomous republic of the Russian SFSR, succeeding ...

. Those who did not collaborate with the Nazis were not spared deportation. Even the families of Heroes of the Soviet Union

The title Hero of the Soviet Union () was the highest distinction in the Soviet Union, awarded together with the Order of Lenin personally or collectively for heroic feats in service to the Soviet state and society. The title was awarded both t ...

where the head of the household was Crimean Tatar were subject to deportation. Crimean Tatars who were members of the Communist Party and in leadership positions in the Crimean ASSR

Several different governments controlled the Crimean Peninsula during the period of the Soviet Union, from the 1920s to 1991. The government of Crimea from 1921 to 1936 was the Crimean Autonomous Socialist Soviet Republic, which was an Autonomo ...

government, as well Crimean Tatars serving in the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army, often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Republic and, from 1922, the Soviet Union. The army was established in January 1918 by a decree of the Council of People ...

and even Tajfa Crimean Tatar Holocaust

The Holocaust (), known in Hebrew language, Hebrew as the (), was the genocide of History of the Jews in Europe, European Jews during World War II. From 1941 to 1945, Nazi Germany and Collaboration with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy ...

survivors were subject to exile. As special settlers in diaspora they had few civil rights and were forbidden from leaving a small radius of the village or city they were assigned to, punishable by 20 years in prison.

The Crimean ASSR was dissolved on 30 June 1945, and a campaign of mass detatarization of Crimea followed: Crimean Tatar books were burned, villages with Crimean Tatar names were renamed, and Crimean Tatar cemeteries were not only destroyed but the gravestones used as building materials. Crimea was quickly resettled by waves of ethnic Russian and Ukrainian immigrants, many of whom were given houses and property of deported Crimean Tatars.

In 1956 other nations deported with accusations of mass treason were permitted to return and their titular republics were officially restored - such as the Chechens

The Chechens ( ; , , Old Chechen: Нахчой, ''Naxçoy''), historically also known as ''Kistin, Kisti'' and ''Durdzuks'', are a Northeast Caucasian languages, Northeast Caucasian ethnic group of the Nakh peoples native to the North Caucasus. ...

and Ingush

Ingush may refer to:

* Ingush language, Northeast Caucasian language

* Ingush people, an ethnic group of the North Caucasus

See also

*Ingushetia (disambiguation)

Ingushetia is a federal republic and subject of Russia.

Ingushetia may also refer ...

, Kalmyks

Kalmyks (), archaically anglicised as Calmucks (), are the only Mongolic ethnic group living in Europe, residing in the easternmost part of the European Plain.

This dry steppe area, west of the lower Volga River, known among the nomads as ...

, Balkars

Balkars ( or аланла, romanized: alanla or таулула, , 'mountaineers') are a Turkic peoples, Turkic ethnic group in the North Caucasus region, one of the titular nation, titular populations of Kabardino-Balkaria.

Their Karachay-B ...

, and Karachays

The Karachays or Karachais ( or ) are a North Caucasian- Turkic ethnic group primarily located in their ancestral lands in Karachay–Cherkess Republic, a republic of Russia in the North Caucasus. They and the Balkars share a common orig ...

. The deported Caucasian peoples heavily resisted their exile, many participating in a prolonged guerrilla war against the NKVD in the mountains of the Caucasus. Abrek

250px, up Chechen abrek

Abrek is a Caucasian term used for a lone Caucasian warrior living a partisan lifestyle outside power and law and fighting for a just cause. Abreks were irregular soldiers who abandoned all material life, including their f ...

s, like Akhmed Khuchbarov

Akhmed Sosievich Khuchbarov (1894–1956) was an Ingush ''abrek'', guerrilla fighter and warlord who led an Ingush resistance against the Soviet regime for 27 years up until his death in 1956. Akhmed made numerous operations and attacks on NKVD ...

and Laysat Baisarova became folk heroes of those deported peoples. In contrast, Crimean Tatars put up considerably less resistance to exile, but still had a strong desire to return. The decree rehabilitating the aforementioned deported peoples of the Caucasus in 1956 did not restore the Crimean ASSR, and said that Crimean Tatars who wanted a national autonomy could "reunite" with the Volga Tatars of the Tatar ASSR

The Tatar Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic, abbreviated as Tatar ASSR or TASSR, was an autonomous republic of the Russian SFSR. The resolution for its creation was signed on 27 May 1920 and the republic was proclaimed on 25 June 1920. Kazan ...

.

For twenty years, the government maintained that their national issue had been "solved" by the decree in 1967 which proclaimed that "people of Tatar nationality formerly living in Crimea" icwere "rehabilitated". The decree, published selectively in newspapers where Crimean Tatars lived for them to see, showed that the state no longer recognized Crimean Tatars as a distinct ethnic group, through the use of the euphemism "people of Tatar nationality formerly living in Crimea". The decree did not answer any of the requests of Crimean Tatar rights activists at the time, specifically official rehabilitation by the state restoration of the Crimean ASSR with a Crimean Tatar national district, the right to return to Crimea. As more and more tried to return to Crimea, the government made it even harder for Crimean Tatars to return to Crimea by issuing decrees in the 1970s tightening the passport regime in Crimea.

Because they were not a recognized ethnic group and lumped into the Tatars

Tatars ( )Tatar

in the Collins English Dictionary are a group of Turkic peoples across Eas ...

in censuses despite being a completely separate ethnic group of a different origin, it was very hard to determine what the Crimean Tatar population was in the Soviet Union during the struggle for the right of return.

in the Collins English Dictionary are a group of Turkic peoples across Eas ...

When pressed on the issue by foreign journalists, the government insisted that Crimean Tatars had equal rights and but that most simply did not want to return to Crimea and had "taken root" in places of exile. However, when Crimean Tatars tried to move to Crimea, they were almost always denied the required propiska (residence permit) and subject to re-deportation, while slavic migrants to Crimea faced no such barriers to getting permission to live in Crimea and were frequently encouraged to move there. While Crimean Tatars were told that Crimea was already overpopulated as an excuse for not letting them return, even though newspapers frequently advertised the need for more workers in Crimea.

In the

When pressed on the issue by foreign journalists, the government insisted that Crimean Tatars had equal rights and but that most simply did not want to return to Crimea and had "taken root" in places of exile. However, when Crimean Tatars tried to move to Crimea, they were almost always denied the required propiska (residence permit) and subject to re-deportation, while slavic migrants to Crimea faced no such barriers to getting permission to live in Crimea and were frequently encouraged to move there. While Crimean Tatars were told that Crimea was already overpopulated as an excuse for not letting them return, even though newspapers frequently advertised the need for more workers in Crimea.

In the Uzbek SSR

The Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic (, ), also known as Soviet Uzbekistan, the Uzbek SSR, UzSSR, or simply Uzbekistan and rarely Uzbekia, was a union republic of the Soviet Union. It was governed by the Uzbek branch of the Soviet Communist P ...

, where most Crimean Tatars lived, those who expressed desire to move to Crimea were told that they could not move to Crimea and should know better than to ask for the right of return, and Crimean Tatars who tried to return to Crimea were almost always forced to leave. Nevertheless, most Crimean Tatars still wanted to return to Crimea.

Initial Red Square protest and delegations

During the early days of the Crimean Tatar national movement, Crimean Tatars sent large delegations of highly respected Crimean Tatar activists and party members to Moscow to meet with Soviet leaders and ask for right of return and restoration of the Crimean ASSR and present them with petitions. However, as time passed and the delegations accomplished little besides being participants being berated for their participation, such delegations and visits to Moscow became smaller and less frequent. However, due toperestroika

''Perestroika'' ( ; rus, перестройка, r=perestrojka, p=pʲɪrʲɪˈstrojkə, a=ru-perestroika.ogg, links=no) was a political reform movement within the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) during the late 1980s, widely associ ...

, Crimean Tatar activists developed a renewed interest in visiting Moscow en masse. In addition, they hoped that under reduced censorship the media would be willing to listen to and include their opinions in media coverage of the national issue instead of maintaining the line that the issue was settled. On 20 June 1987 the first Crimean Tatar delegates arrived in Moscow, where they visited the offices of various newspapers, magazines, and TV stations as well as the writers union and talked about their exile and requested that their letters and petitions be published, but they were typically turned down. Later on 26 June several Crimean Tatars met with Pyotr Demichev

Pyotr Nilovich Demichev (; 10 August 2010) was a Soviet politician. He was deputy Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet from 1986 to 1988 and Minister of Culture from 1974 to 1986. He was a deputy Politburo member from 1964 until his ...

, who only agreed to tell Gorbachev about their comments. Later on in early July several dozen Crimean Tatars began picketing in Red Square holding signs calling for right of return. The size of the protests grew quickly: the picket in front of the building of the Central Committee of the CPSU

The Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union was the Central committee, highest organ of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) between Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, Congresses. Elected by the ...

on 23 July drew around 100 protesters, but the number increased to around 500 just two days later.

Formation of commission

On 9 July 1987 the government agreed to form a commission decide the fate of the Crimean Tatar people. The day before, a small delegation of Crimean Tatars met with People's Writer of the USSRYevgeny Yevtushenko

Yevgeny Aleksandrovich Yevtushenko (; 18 July 1933 – 1 April 2017) was a Soviet and Russian poet, novelist, essayist, dramatist, screenwriter, publisher, actor, editor, university professor, and director of several films.

Biography Early lif ...

, who then encouraged Soviet leaders to give them a meeting or at least listen to them. Originally they were given a meeting with Pyotr Demichev, not Gorbachev; Demichev was not sympathetic to their petitioning but did forward their message to Gorbachev.

The issue made it to discussion in the politburo, and Gorbachev, who was reluctant to make any solid decisions on the issue, decided to outsource the issue to a commission. Subsequently, Gromyko, who rarely handled domestic issues, was selected by Gorbachev to head the commission despite his extreme reluctance to meet with Crimean Tatars and his hostile attitude towards the ethnic group. In a conversation with Gorbachev, he expressed desire to ignore the Crimean Tatars entirely and keep them in places of exile as was policy for the past decades. Nevertheless, Gromyko was appointed head of the commission, and he reluctantly discussed the issue with other Soviet politicians.

The leadership of the commission consisted of various senior Soviet politicians who had strong feelings on the issue, specifically Viktor Chebrikov

Viktor Mikhailovich Chebrikov (; 27 April 1923 – 2 July 1999) was a Soviet public official and security administrator and head of the KGB from December 1982 to October 1988.Montgomery, Isobel (7 July 1999)Viktor Chebrikov: KGB chief who favoure ...

, Vitaly Vorotnikov

Vitaly Ivanovich Vorotnikov (; 20 January 1926 – 19 February 2012) was a Soviet politician and diplomat who was the Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the Russian SFSR between 1988 and 1990.

Early life and education

Vorot ...

, Vladimir Shcherbitsky, Inomjon Usmonxoʻjayev

Inomjon Buzrukovich Usmonxojayev (in Uzbek Cyrillic: Иномжон Бузрукович Усмонхўжаев ; in Russian: Инамджан Бузрукович Усманходжаев ''Inamdzhan Buzrukovich Usmankhodzhayev''; 22 May 1930 ...

, Pyotr Demichev

Pyotr Nilovich Demichev (; 10 August 2010) was a Soviet politician. He was deputy Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet from 1986 to 1988 and Minister of Culture from 1974 to 1986. He was a deputy Politburo member from 1964 until his ...

, Alexander Yakovlev

Alexander Nikolayevich Yakovlev (; 2 December 1923 – 18 October 2005) was a Soviet and Russian politician, diplomat, and historian. A member of the Politburo and Secretariat of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union throughout the 1980s ...

, Anatoly Lukyanov

Anatoly Ivanovich Lukyanov (, 7 May 1930 – 9 January 2019) was a Russian Communist politician who was the Chairman of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR between 15 March 1990 and 4 September 1991. One of the founders of the Communist Party of the ...

, Georgy Razumovsky, but no Crimean Tatars.

Period of operation

After asking for meetings withMikhail Gorbachev

Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev (2 March 1931 – 30 August 2022) was a Soviet and Russian politician who served as the last leader of the Soviet Union from 1985 to dissolution of the Soviet Union, the country's dissolution in 1991. He served a ...

, 21 Crimean Tatar representatives eventually met in the Kremlin with Gromyko on 27 July 1987 in a very unproductive meeting for 2 hours and 27 minutes where he demanded Crimean Tatars be more calm but was extremely condescending insulted them as an "invented" ethnic group and showed his hatred for Crimean Tatars, living up to his nickname "Mr. No."

Compounded by the publication of the libelous announcement from TASS

The Russian News Agency TASS, or simply TASS, is a Russian state-owned news agency founded in 1904. It is the largest Russian news agency and one of the largest news agencies worldwide.

TASS is registered as a Federal State Unitary Enterpri ...

in central newspapers the next day about the formation of the commission, many Crimean Tatar activists and even communist elders were very disappointed as it became obvious that the commission was unwilling to seriously consider their demands. Later another statement from Gromyko warning that any attempt to put pressure on state organs would not work out in their favor was republished by TASS.

Meanwhile, authorities in Crimea remained hostile to the idea of allowing Crimean Tatar right of return, and further tightened the passport regime in Crimea as additional Crimean Tatars attempted to arrive and register in the peninsula. A decree signed by Nikolai Ryzhkov

Nikolai Ivanovich Ryzhkov (; ; 28 September 1929 – 28 February 2024) was a Russian politician. He served as the last Premier of the Soviet Union, chairman of the Council of Ministers of the Soviet Union from 1985 to 1991 and was succeeded b ...

created special restrictions on registering new residents in Crimea as well as Krasnodar

Krasnodar, formerly Yekaterinodar (until 1920), is the largest city and the administrative centre of Krasnodar Krai, Russia. The city stands on the Kuban River in southern Russia, with a population of 1,154,885 residents, and up to 1.263 millio ...

. The government characterized the Crimean Tatar desire to return and restoration of the Crimean ASSR as an extreme position and claimed such positions were not specific.

Central Initiative Group actions

Despite Gromyko's warning that increased protests and other forms of public discontent would not be taken well, members of the Central Initiative Group (OKND) led byMustafa Dzhemilev

Mustafa Abduldzhemil Jemilev (, ), also known widely with his adopted descriptive surname Qırımoğlu "Son of Crimea" ( Crimean Tatar Cyrillic: , ; born 13 November 1943, Ay Serez, Crimea), is the former chairman of the Mejlis of the Crimean T ...

continued to remain in Moscow, holding rallies in Izmailovsky Park. Prominent representatives from the Dzhemilev faction including Sabriye Seutova, Safinar Dzhemileva, Reshat Dzhemilev, and Fuat Ablyamitov. While the original advocates of the Crimean Tatar national movement who were condemned by mainstream Soviet dissidents as Marxists

Marxism is a political philosophy and method of socioeconomic analysis. It uses a dialectical and materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to analyse class relations, social conflict, and ...

, many members of the more radical Central Initiative Group listed above, among others, openly solicited support from the West, which concerned the more moderate NDKT. The Central Initiative group disproportionately of the younger generation born in exile and had never been part of the national movement before, and grew in power as Soviet authorities failed to meaningfully address Crimean Tatar rights.

Results

Despite being sent various proposals for plans to restore the Crimean ASSR and return Crimean Tatars to Crimea, in addition to polling information of Crimean Tatars showing that a solid majority supported returning to Crimea, the requests of the Crimean Tatar community were rejected. The conclusion statement issued by Gromyko in June 1988 stated there was "no basis" restore the Crimean ASSR because of the current demographics of Crimea, and suggested only a small percent of the Crimean Tatars to Crimea to work in Crimea under an organized recruitment scheme, but maintained that there would be no mass return of Crimean Tatars, and instead offered additional small-scale measures to address the cultural needs of Crimean Tatars places of exile. It also did not agree to restore the official recognition of Crimean Tatars as a distinct ethnic group.Reception and aftermath

Responses to the conclusions of the commission were overwhelmingly negative; even people the most loyal communist Crimean Tatars were disappointed by the conclusions of the commission and criticized the lack of good faith on part of the commission. For exampleRollan Kadyev

Rollan Kemalevich Kadyev (, ; 9 April 1937 – 15 May 1990) was a Crimean Tatar physicist and civil rights activist in the Soviet Union. A defendant in the Tashkent process, he became known as a firebrand opponent of marginalization and delimina ...

, by then having evolved politically to the point of opposing the rally in Red Square out of fear it would provoke authorities and frequently telling other Crimean Tatars to not respond to provocations from the government and maintain patriotism, expressed dismay at the idea that only a few more Crimean Tatars could be allowed to move to Crimea, which he dubbed "lottery for the homeland." He also criticized Gromyko's conclusions that the Crimean ASSR could not be restored because of demographic reasons, noting that the Kazakh SSR was formed when Kazakhs were only 13% of the population of the region.

Barely a year after the conclusion of the commission rejecting return and restoration of the Crimean ASSR, a second commission was composed to re-evaluated the issue, but headed by Yanaev instead of Gromyko and inclusive of Crimean Tatars on the board. Only in 1989 were the restrictions on the use of the term Crimean Tatar officially lifted. "In 1989, the secret ban on the ethnonym “Crimean Tatar” was lifted"

Footnotes

References

Works cited

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * {{Crimean Tatar Surgun era De-Tatarization of Crimea Politics of the Crimean Tatars