Greely Expedition on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

*

The Lady Franklin Bay Expedition of 1881–1884 ( the Greely Expedition) to

The Lady Franklin Bay Expedition of 1881–1884 ( the Greely Expedition) to

The Lady Franklin Bay Expedition was led by Lieutenant Adolphus W. Greely of the Fifth United States Cavalry, with astronomer

The Lady Franklin Bay Expedition was led by Lieutenant Adolphus W. Greely of the Fifth United States Cavalry, with astronomer

Frederick Hadley Journal, Surgeon on the ''Neptune''

at Dartmouth College Library

Charles S. McClain diary excerpts

at Dartmouth College Library

P.W. Johnson Diary

at Dartmouth College Library

PBS: Abandoned in the Arctic

{{Authority control 19th century in the Arctic 1881 in Canada 1882 in Canada 1883 in Canada 1884 in Canada Arctic expeditions Incidents of cannibalism North American expeditions

The Lady Franklin Bay Expedition of 1881–1884 ( the Greely Expedition) to

The Lady Franklin Bay Expedition of 1881–1884 ( the Greely Expedition) to Lady Franklin Bay

Lady Franklin Bay is an Arctic waterway in the Qikiqtaaluk Region, Nunavut, Canada. The bay is located in Nares Strait, northwest of Judge Daly Promontory and is an inlet into the northeastern shore of Ellesmere Island.

Fort Conger—former ...

on Ellesmere Island

Ellesmere Island (; ) is Canada's northernmost and List of Canadian islands by area, third largest island, and the List of islands by area, tenth largest in the world. It comprises an area of , slightly smaller than Great Britain, and the total ...

in the Canadian Arctic

Northern Canada (), colloquially the North or the Territories, is the vast northernmost region of Canada, variously defined by geography and politics. Politically, the term refers to the three territories of Canada: Yukon, Northwest Territories a ...

was led by Lieutenant Adolphus Greely

Adolphus Washington Greely (March 27, 1844 – October 20, 1935) was a United States Army officer and polar explorer. He attained the rank of major general and was a recipient of the Medal of Honor.

A native of Newburyport, Massachusetts, ...

, and was promoted by the United States Army Signal Corps

The United States Army Signal Corps (USASC) is a branch of the United States Army responsible for creating and managing Military communications, communications and information systems for the command and control of combined arms forces. It was ...

. Its purpose was to establish a meteorological-observation station as part of the First International Polar Year

The International Polar Years (IPY) are collaborative, international efforts with intensive research focus on the polar regions. Karl Weyprecht, an Austro-Hungarian naval officer, motivated the endeavor in 1875, but died before it first occurred ...

, and to collect astronomical and magnetic data. During the expedition, two members of the crew reached a new Farthest North

Farthest North describes the most northerly latitude reached by explorers, before the first successful expedition to the North Pole rendered the expression obsolete. The Arctic polar regions are much more accessible than those of the Antarctic, as ...

record, but of the original twenty-five men, only seven survived to return.

The expedition was under the auspices of the Signal Corps at a time when the corps' chief disbursements officer, Henry W. Howgate, was arrested for embezzlement

Embezzlement (from Anglo-Norman, from Old French ''besillier'' ("to torment, etc."), of unknown origin) is a type of financial crime, usually involving theft of money from a business or employer. It often involves a trusted individual taking ...

. However, that did not deter the planning and execution of the voyage.

Expedition

First year, 1881

The Lady Franklin Bay Expedition was led by Lieutenant Adolphus W. Greely of the Fifth United States Cavalry, with astronomer

The Lady Franklin Bay Expedition was led by Lieutenant Adolphus W. Greely of the Fifth United States Cavalry, with astronomer Edward Israel

Edward Israel (July 1, 1859 – May 27, 1884) was an astronomer and Polar explorer.

Early years

Israel was born in Kalamazoo, Michigan on July 1, 1859. He was the son of Mannes and Tillie Israel, the first Jews to settle in Kalamazoo. After gradu ...

and photographer George W. Rice among the crew of twenty-one officers and men. They sailed on the ship ''Proteus'' and reached St. John's, Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region of Labrador, having a total size of . As of 2025 the population ...

, in early July 1881. At Godhavn

Qeqertarsuaq (, historically known as Godhavn) is a port and town in Qeqertalik municipality, located on the south coast of Disko Island on the west coast of Greenland. Founded in 1773, the town is now home to a campus of the University of Cope ...

, Greenland

Greenland is an autonomous territory in the Danish Realm, Kingdom of Denmark. It is by far the largest geographically of three constituent parts of the kingdom; the other two are metropolitan Denmark and the Faroe Islands. Citizens of Greenlan ...

, they picked up Jens Edward Jens may refer to:

* Jens (given name), a list of people with the name

* Jens (surname), a list of people

* Jens, Switzerland, a municipality

* 1719 Jens, an asteroid

See also

* Jensen (disambiguation) Jensen may refer to:

People and fictional ...

and Thorlip Frederik Christiansen, two Inuit

Inuit (singular: Inuk) are a group of culturally and historically similar Indigenous peoples traditionally inhabiting the Arctic and Subarctic regions of North America and Russia, including Greenland, Labrador, Quebec, Nunavut, the Northwe ...

dogsled drivers, as well as physician Octave Pierre Pavy and Mr. Clay who had continued scientific studies instead of returning on ''Florence'' with the remainder of the 1880 Howgate Expedition.

''Proteus'' arrived without problems at Lady Franklin Bay

Lady Franklin Bay is an Arctic waterway in the Qikiqtaaluk Region, Nunavut, Canada. The bay is located in Nares Strait, northwest of Judge Daly Promontory and is an inlet into the northeastern shore of Ellesmere Island.

Fort Conger—former ...

by August 11, dropped off men and provisions, and left. In the following months, Lieutenant James Booth Lockwood and Sergeant David Legge Brainard

David Legge Brainard (December 21, 1856 – March 22, 1946) was a career officer in the United States Army. He enlisted in 1876, received his officer's commission in 1886, and served until 1919. Brainard attained the rank of brigadier gener ...

achieved a new Farthest North

Farthest North describes the most northerly latitude reached by explorers, before the first successful expedition to the North Pole rendered the expression obsolete. The Arctic polar regions are much more accessible than those of the Antarctic, as ...

record at , off the north coast of Greenland. Unbeknownst to Greely, the summer had been extraordinarily warm, which led to an underestimation of the difficulties which their relief expeditions would face in reaching Lady Franklin Bay in subsequent years.

Second year, 1882

By summer of 1882, the men were expecting a supply ship from the south. ''Neptune'', laden with relief supplies, set out in July 1882 but, cut off by ice and weather, Captain Beebe was forced to turn around prematurely. All he could do was leave some supplies atSmith Sound

Smith Sound (; ) is an Arctic sea passage between Greenland

Greenland is an autonomous territory in the Danish Realm, Kingdom of Denmark. It is by far the largest geographically of three constituent parts of the kingdom; the other two are ...

in August, and the remaining provisions in Newfoundland, with plans for their delivery the following year.

On July 20, Pavy's contract ended, and Pavy announced that he would not renew it, but would continue to attend to the expedition's medical needs. Greely was incensed, and ordered the doctor to turn over all his records and journals. Pavy refused, and Greely placed him under arrest. Pavy was not confined, however Greely claimed he intended to court-martial

A court-martial (plural ''courts-martial'' or ''courts martial'', as "martial" is a postpositive adjective) is a military court or a trial conducted in such a court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of members of the arme ...

him when they returned to the United States.

Third year, 1883

In 1883, new rescue attempts by ''Proteus'', commanded by LieutenantErnest Albert Garlington

Ernest Albert Garlington (February 20, 1853 – October 16, 1934) was a United States Army general who received the Medal of Honor for his participation in the Wounded Knee Massacre during the Indian Wars.

Early life and education

Garlington was ...

, and ''Yantic'', commanded by Commander Frank Wildes, failed, with ''Proteus'' being crushed by pack ice.

In the summer of 1883, in accordance with his instructions for the case of two consecutive relief expeditions not reaching Fort Conger

Fort Conger is a former settlement, military fortification, and scientific research post in the Qikiqtaaluk Region, Nunavut, Canada. It was established in 1881 as an Arctic exploration camp, notable as the site of the first major northern polar ...

, Greely decided to head South with his crew. It had been planned that the relief ships should depot supplies along the Nares Strait

Nares Strait (; ) is a waterway between Ellesmere Island and Greenland that connects the northern part of Baffin Bay in the Atlantic Ocean with the Lincoln Sea in the Arctic Ocean. From south to north, the strait includes Smith Sound, Kane Basi ...

, around Cape Sabine

Cape Sabine is a land point on Pim Island, off the eastern shores of the Johan Peninsula, Ellesmere Island, in the Smith Sound, Qikiqtaaluk Region, Nunavut, Canada.

History

The cape was named after Arctic explorer Sir Edward Sabine (1788–1883 ...

and at Littleton Island, if they were unable to reach Fort Conger, which should have made for a comfortable wintering of Greely's men. But with ''Neptune'' not even getting that far and ''Proteus'' sunk, in reality only a small emergency cache with 40 days worth of supplies had been laid at Cape Sabine by ''Proteus''.

When arriving there in October 1883, the season was too advanced for Greely to either try to brave the Baffin Bay

Baffin Bay (Inuktitut: ''Saknirutiak Imanga''; ; ; ), located between Baffin Island and the west coast of Greenland, is defined by the International Hydrographic Organization as a marginal sea of the Arctic Ocean. It is sometimes considered a s ...

to reach Greenland with his small boats, or to retire to Fort Conger, so he had to winter on the spot.

Fourth year, 1884

In 1884, Secretary of the Navy, William E. Chandler, was credited with planning the ensuing rescue effort, commanded by Cdr.Winfield Scott Schley

Winfield Scott Schley (9 October 1839 – 2 October 1911) was a rear admiral in the United States Navy and the hero of the Battle of Santiago de Cuba during the Spanish–American War.

Biography

Early life

Born at "Richfields" (his father's far ...

. While four vessels—, , , and ''Loch Garry''—made it to Greely's camp on June 22, only seven men had survived the winter. The rest had succumbed to starvation, hypothermia

Hypothermia is defined as a body core temperature below in humans. Symptoms depend on the temperature. In mild hypothermia, there is shivering and mental confusion. In moderate hypothermia, shivering stops and confusion increases. In severe ...

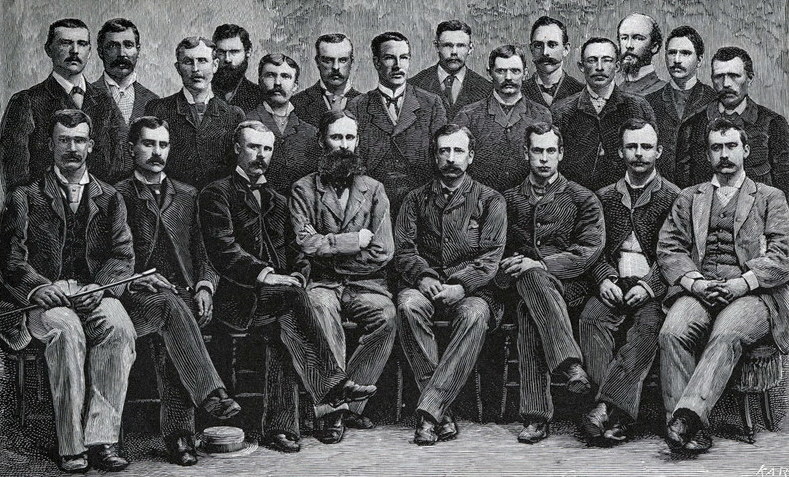

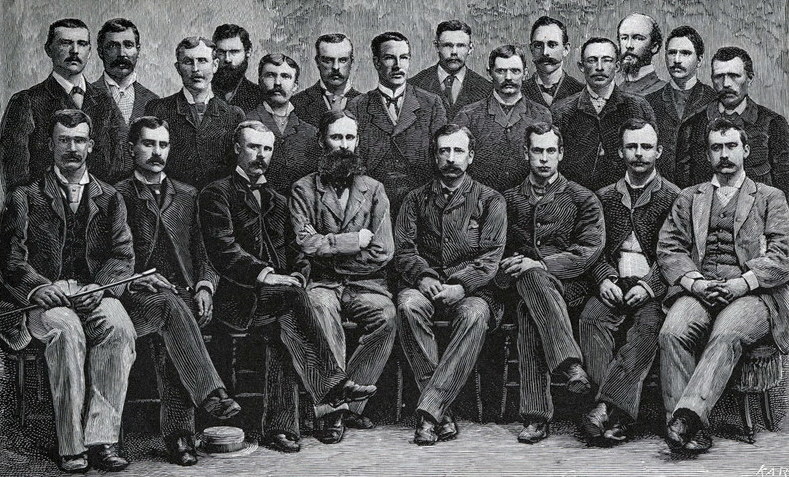

, and drowning, and one man, Private Henry, had been executed on Greely's order for repeated theft of food. Of the seven rescued, Joseph Elison died on July 8 following multiple amputations. The relief party arrived at St. John's, Newfoundland on July 17, 1884, from which the news was telegraphed throughout the States, and a sketched portrait of the members of the Greely Expedition, both living and dead, was published. After a stay of ten days the ships left for New York.

Civil War hero David Lewis Gifford

David Lewis Gifford (September 18, 1844 – January 13, 1904) was a Union Army soldier in the American Civil War who received the U.S. military's highest decoration, the Medal of Honor. He was awarded the Medal of Honor, for extraordinary herois ...

served as an ice master on HMS ''Alert''.

The surviving members of the expedition were received as heroes. A parade attended by thousands was held in Portsmouth, New Hampshire

Portsmouth is a city in Rockingham County, New Hampshire, Rockingham County, New Hampshire, United States. At the 2020 United States census, 2020 census it had a population of 21,956. A historic seaport and popular summer tourist destination on ...

. It was decided that each of the survivors was to be awarded a promotion in rank by the Army, although Greely reportedly refused.

Controversy

Rumors ofcannibalism

Cannibalism is the act of consuming another individual of the same species as food. Cannibalism is a common ecological interaction in the animal kingdom and has been recorded in more than 1,500 species. Human cannibalism is also well document ...

arose following the return of the corpses. On August 14, 1884, a few days after his funeral, the body of Lieutenant Frederick Kislingbury, second in command of the expedition, was exhumed and an autopsy was performed. The finding that flesh had been cut from the bones appeared to confirm the accusation. However, Greely and the surviving crew denied knowledge of cannibalism. Brainard and Rice had devised a method of netting sea-lice for food, and Greely surmised that if flesh had been cut from the bodies of the dead, some group members who died before being rescued needed bait, so they cut into the bodies of those who had previously died.

Notes

References

Bibliography

* * * * *External links

* *Frederick Hadley Journal, Surgeon on the ''Neptune''

at Dartmouth College Library

Charles S. McClain diary excerpts

at Dartmouth College Library

P.W. Johnson Diary

at Dartmouth College Library

PBS: Abandoned in the Arctic

{{Authority control 19th century in the Arctic 1881 in Canada 1882 in Canada 1883 in Canada 1884 in Canada Arctic expeditions Incidents of cannibalism North American expeditions