Great Tit on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The great tit (''Parus major'') is a small

The great tit (''Parus major'') is a small

The great tit was formerly treated as ranging from Britain to Japan and south to the islands of Indonesia, with 36 described subspecies ascribed to four main species groups. The ''major'' group had 13 subspecies across Europe, temperate Asia and north Africa, the ''minor'' group's nine subspecies occurred from southeast

The great tit was formerly treated as ranging from Britain to Japan and south to the islands of Indonesia, with 36 described subspecies ascribed to four main species groups. The ''major'' group had 13 subspecies across Europe, temperate Asia and north Africa, the ''minor'' group's nine subspecies occurred from southeast

There is some variation in the subspecies. ''P. m. newtoni'' is like the nominate race but has a slightly longer bill, the mantle is slightly deeper green, there is less white on the tail tips, and the ventral mid-line stripe is broader on the belly. ''P. m. corsus'' also resembles the nominate form but has duller upperparts, less white in the tail and less yellow in the nape. ''P. m. mallorcae'' is like the nominate subspecies, but has a larger bill, greyer-blue upperparts and slightly paler underparts. ''P. m. ecki'' is like ''P. m. mallorcae'' except with bluer upperparts and paler underparts. ''P. m. excelsus'' is similar to the nominate race but has much brighter green upperparts, bright yellow underparts and no (or very little) white on the tail. ''P. m. aphrodite'' has darker, more olive-grey upperparts, and the underparts are more yellow to pale cream. ''P. m. niethammeri'' is similar to ''P. m. aphrodite'' but the upperparts are duller and less green, and the underparts are pale yellow. ''P. m. terrasanctae'' resembles the previous two subspecies but has slightly paler upperparts. ''P. m. blandfordi'' is like the nominate but with a greyer mantle and scapulars and pale yellow underparts, and ''P. m. karelini'' is intermediate between the nominate and ''P. m. blandfordi'', and lacks white on the tail. The plumage of ''P. m. bokharensis'' is much greyer, pale creamy white to washed out grey underparts, a larger white cheep patch, a grey tail, wings, back and nape. It is also slightly smaller, with a smaller bill but longer tail. The situation is similar for the two related subspecies in the Turkestan tit group. ''P. m. turkestanicus'' is like ''P. m. bokharensis'' but with a larger bill and darker upperparts. ''P. m. ferghanensis'' is like ''P. m. bokharensis'' but with a smaller bill, darker grey on the flanks and a more yellow wash on the juvenile birds.

There is some variation in the subspecies. ''P. m. newtoni'' is like the nominate race but has a slightly longer bill, the mantle is slightly deeper green, there is less white on the tail tips, and the ventral mid-line stripe is broader on the belly. ''P. m. corsus'' also resembles the nominate form but has duller upperparts, less white in the tail and less yellow in the nape. ''P. m. mallorcae'' is like the nominate subspecies, but has a larger bill, greyer-blue upperparts and slightly paler underparts. ''P. m. ecki'' is like ''P. m. mallorcae'' except with bluer upperparts and paler underparts. ''P. m. excelsus'' is similar to the nominate race but has much brighter green upperparts, bright yellow underparts and no (or very little) white on the tail. ''P. m. aphrodite'' has darker, more olive-grey upperparts, and the underparts are more yellow to pale cream. ''P. m. niethammeri'' is similar to ''P. m. aphrodite'' but the upperparts are duller and less green, and the underparts are pale yellow. ''P. m. terrasanctae'' resembles the previous two subspecies but has slightly paler upperparts. ''P. m. blandfordi'' is like the nominate but with a greyer mantle and scapulars and pale yellow underparts, and ''P. m. karelini'' is intermediate between the nominate and ''P. m. blandfordi'', and lacks white on the tail. The plumage of ''P. m. bokharensis'' is much greyer, pale creamy white to washed out grey underparts, a larger white cheep patch, a grey tail, wings, back and nape. It is also slightly smaller, with a smaller bill but longer tail. The situation is similar for the two related subspecies in the Turkestan tit group. ''P. m. turkestanicus'' is like ''P. m. bokharensis'' but with a larger bill and darker upperparts. ''P. m. ferghanensis'' is like ''P. m. bokharensis'' but with a smaller bill, darker grey on the flanks and a more yellow wash on the juvenile birds.

The colour of the male bird's breast has been shown to correlate with stronger sperm, and is one way that the male demonstrates his reproductive superiority to females. Higher levels of

The colour of the male bird's breast has been shown to correlate with stronger sperm, and is one way that the male demonstrates his reproductive superiority to females. Higher levels of

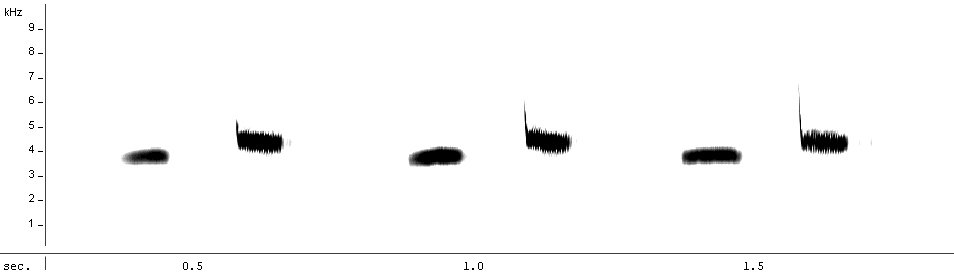

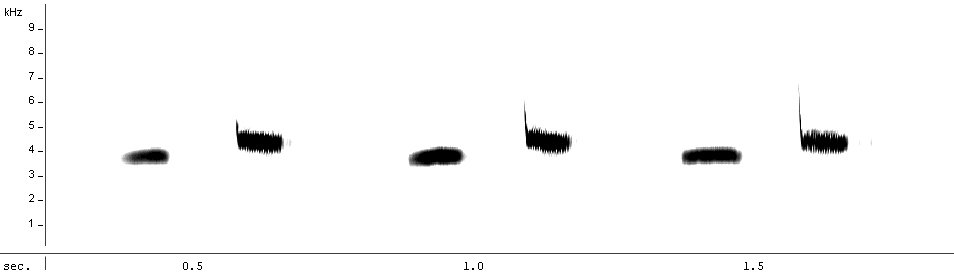

The great tit is, like other tits, a vocal bird, and has up to 40 types of calls and songs. The calls are generally the same between the sexes, but the male is much more vocal and the female rarely calls. Soft single notes such as "pit", "spick", or "chit" are used as contact calls. A loud "tink" is used by adult males as an alarm or in territorial disputes. One of the most familiar is a "teacher, teacher", often likened to a squeaky wheelbarrow wheel, which is used in proclaiming ownership of a territory. In former times, English folk considered the "saw-sharpening" call to be a foretelling of rain. Tit calls from different geographic regions show some variation, and tits from the two south Asian groups recently split from the great tit do not recognise or react to the calls of the temperate great tits.

One explanation for the great tit's wide repertoire is the Beau Geste hypothesis. The eponymous hero of the novel propped dead soldiers against the battlements to give the impression that his fort was better defended than was really the case. Similarly, the multiplicity of calls gives the impression that the tit's territory is more densely occupied than it actually is. Whether the theory is correct or not, those birds with large vocabularies are socially dominant and breed more successfully.

The great tit is, like other tits, a vocal bird, and has up to 40 types of calls and songs. The calls are generally the same between the sexes, but the male is much more vocal and the female rarely calls. Soft single notes such as "pit", "spick", or "chit" are used as contact calls. A loud "tink" is used by adult males as an alarm or in territorial disputes. One of the most familiar is a "teacher, teacher", often likened to a squeaky wheelbarrow wheel, which is used in proclaiming ownership of a territory. In former times, English folk considered the "saw-sharpening" call to be a foretelling of rain. Tit calls from different geographic regions show some variation, and tits from the two south Asian groups recently split from the great tit do not recognise or react to the calls of the temperate great tits.

One explanation for the great tit's wide repertoire is the Beau Geste hypothesis. The eponymous hero of the novel propped dead soldiers against the battlements to give the impression that his fort was better defended than was really the case. Similarly, the multiplicity of calls gives the impression that the tit's territory is more densely occupied than it actually is. Whether the theory is correct or not, those birds with large vocabularies are socially dominant and breed more successfully.

The great tit has a wide distribution across much of Eurasia. It can be found across all of Europe except for

The great tit has a wide distribution across much of Eurasia. It can be found across all of Europe except for

Great tits are primarily insectivorous in the summer, feeding on

Great tits are primarily insectivorous in the summer, feeding on

Great tits are seasonal breeders. The exact timing of breeding varies by a number of factors, most importantly location. Most breeding occurs between January and September; in Europe the breeding season usually begins after March. In Israel there are exceptional records of breeding during the months of October to December. The amount of sunlight and daytime temperatures will also affect breeding timing. One study found a strong correlation between the timing of laying and the peak abundance of caterpillar prey, which is in turn correlated to temperature. On an individual level, younger females tend to start laying later than older females.

Great tits are seasonal breeders. The exact timing of breeding varies by a number of factors, most importantly location. Most breeding occurs between January and September; in Europe the breeding season usually begins after March. In Israel there are exceptional records of breeding during the months of October to December. The amount of sunlight and daytime temperatures will also affect breeding timing. One study found a strong correlation between the timing of laying and the peak abundance of caterpillar prey, which is in turn correlated to temperature. On an individual level, younger females tend to start laying later than older females.

Great tits are cavity nesters, breeding in a hole that is usually inside a tree, although occasionally in a wall or rock face, and they will readily take to nest boxes. The nest inside the cavity is built by the female, and is made of plant fibres, grasses, moss, hair, wool and feathers. The number in the

Great tits are cavity nesters, breeding in a hole that is usually inside a tree, although occasionally in a wall or rock face, and they will readily take to nest boxes. The nest inside the cavity is built by the female, and is made of plant fibres, grasses, moss, hair, wool and feathers. The number in the  The chicks, like those of all tits, hatch unfeathered and blind. Once feathers begin to erupt, the nestlings are unusual for

The chicks, like those of all tits, hatch unfeathered and blind. Once feathers begin to erupt, the nestlings are unusual for

The great tit is a popular garden bird due to its acrobatic performances when feeding on nuts or seed. Its willingness to move into nest boxes has made it a valuable study subject in

The great tit is a popular garden bird due to its acrobatic performances when feeding on nuts or seed. Its willingness to move into nest boxes has made it a valuable study subject in

RSPB page

Song sample

BBC fact file

Ageing and sexing (PDF; 2.5 MB) by Javier Blasco-Zumeta & Gerd-Michael Heinze

Great tit videos, photos & sounds

on the Internet Bird Collection

Titbox and the jay - video

{{Good article great tit Birds of Eurasia great tit great tit

The great tit (''Parus major'') is a small

The great tit (''Parus major'') is a small passerine

A passerine () is any bird of the order Passeriformes (; from Latin 'sparrow' and '-shaped') which includes more than half of all bird species. Sometimes known as perching birds, passerines generally have an anisodactyl arrangement of their ...

bird

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class (biology), class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the Oviparity, laying of Eggshell, hard-shelled eggs, a high Metabolism, metabolic rate, a fou ...

in the tit family Paridae. It is a widespread and common species throughout Europe, the Middle East

The Middle East (term originally coined in English language) is a geopolitical region encompassing the Arabian Peninsula, the Levant, Turkey, Egypt, Iran, and Iraq.

The term came into widespread usage by the United Kingdom and western Eur ...

, Central Asia

Central Asia is a region of Asia consisting of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. The countries as a group are also colloquially referred to as the "-stans" as all have names ending with the Persian language, Pers ...

and east across the Palearctic

The Palearctic or Palaearctic is a biogeographic realm of the Earth, the largest of eight. Confined almost entirely to the Eastern Hemisphere, it stretches across Europe and Asia, north of the foothills of the Himalayas, and North Africa.

Th ...

to the Amur River

The Amur River () or Heilong River ( zh, s=黑龙江) is a perennial river in Northeast Asia, forming the natural border between the Russian Far East and Northeast China (historically the Outer and Inner Manchuria). The Amur ''proper'' is ...

, south to parts of North Africa

North Africa (sometimes Northern Africa) is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region. However, it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of t ...

where it is generally resident in any sort of woodland; most great tits do not migrate except in extremely harsh winters. Until 2005 this species was lumped with numerous other subspecies. DNA

Deoxyribonucleic acid (; DNA) is a polymer composed of two polynucleotide chains that coil around each other to form a double helix. The polymer carries genetic instructions for the development, functioning, growth and reproduction of al ...

studies have shown these other subspecies to be distinct from the great tit and these have now been separated as two distinct species, the cinereous tit (''Parus cinereus'') of southern Asia, and the Japanese tit (''Parus minor'') of East Asia. The great tit remains the most widespread species in the genus ''Parus''.

The great tit is a distinctive bird with a black head and neck, prominent white cheeks, olive upperparts and yellow underparts, with some variation amongst the numerous subspecies. It is predominantly insectivorous in the summer, but will consume a wider range of food items in the winter months, including small hibernating bats. Like all tits it is a cavity nester, usually nesting in a hole in a tree. The female lays around 12 eggs and incubates them alone, although both parents raise the chicks. In most years the pair will raise two broods. The nests may be raided by woodpeckers, squirrel

Squirrels are members of the family Sciuridae (), a family that includes small or medium-sized rodents. The squirrel family includes tree squirrels, ground squirrels (including chipmunks and prairie dogs, among others), and flying squirrel ...

s and weasels and infested with flea

Flea, the common name for the order (biology), order Siphonaptera, includes 2,500 species of small flightless insects that live as external parasites of mammals and birds. Fleas live by hematophagy, ingesting the blood of their hosts. Adult f ...

s, and adults may be hunted by sparrowhawks. The great tit has adapted well to human changes in the environment and is a common and familiar bird in urban parks and gardens. The great tit is also an important study species in ornithology

Ornithology, from Ancient Greek ὄρνις (''órnis''), meaning "bird", and -logy from λόγος (''lógos''), meaning "study", is a branch of zoology dedicated to the study of birds. Several aspects of ornithology differ from related discip ...

.

Taxonomy

The great tit was described under its current binomial name byCarl Linnaeus

Carl Linnaeus (23 May 1707 – 10 January 1778), also known after ennoblement in 1761 as Carl von Linné,#Blunt, Blunt (2004), p. 171. was a Swedish biologist and physician who formalised binomial nomenclature, the modern system of naming o ...

in his 1758 10th edition of ''Systema Naturae''. Its scientific name is derived from the Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

''parus'' "tit" and ''maior'' "larger". Francis Willughby had used the name in the 17th century.

The great tit was formerly treated as ranging from Britain to Japan and south to the islands of Indonesia, with 36 described subspecies ascribed to four main species groups. The ''major'' group had 13 subspecies across Europe, temperate Asia and north Africa, the ''minor'' group's nine subspecies occurred from southeast

The great tit was formerly treated as ranging from Britain to Japan and south to the islands of Indonesia, with 36 described subspecies ascribed to four main species groups. The ''major'' group had 13 subspecies across Europe, temperate Asia and north Africa, the ''minor'' group's nine subspecies occurred from southeast Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

and Japan

Japan is an island country in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean off the northeast coast of the Asia, Asian mainland, it is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan and extends from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea ...

into northern southeast Asia and the 11 subspecies in the ''cinereus'' group were found from Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) and also known as Persia, is a country in West Asia. It borders Iraq to the west, Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Armenia to the northwest, the Caspian Sea to the north, Turkmenistan to the nort ...

across south Asia to Indonesia

Indonesia, officially the Republic of Indonesia, is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania, between the Indian Ocean, Indian and Pacific Ocean, Pacific oceans. Comprising over List of islands of Indonesia, 17,000 islands, including Sumatra, ...

. The three ''bokharensis'' subspecies were often treated as a separate species, ''Parus bokharensis'', the Turkestan tit. This form was once thought to form a ring species

In biology, a ring species is a connected series of neighbouring populations, each of which interbreeds with closely sited related populations, but for which there exist at least two "end populations" in the series, which are too distantly relate ...

around the Tibetan Plateau

The Tibetan Plateau, also known as the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau or Qingzang Plateau, is a vast elevated plateau located at the intersection of Central Asia, Central, South Asia, South, and East Asia. Geographically, it is located to the north of H ...

, with gene flow throughout the subspecies, but this theory was abandoned when sequences of mitochondrial DNA

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA and mDNA) is the DNA located in the mitochondrion, mitochondria organelles in a eukaryotic cell that converts chemical energy from food into adenosine triphosphate (ATP). Mitochondrial DNA is a small portion of the D ...

were examined, finding that the four groups were distinct (monophyletic

In biological cladistics for the classification of organisms, monophyly is the condition of a taxonomic grouping being a clade – that is, a grouping of organisms which meets these criteria:

# the grouping contains its own most recent co ...

) and that the hybridisation zones between the groups were the result of secondary contact after a temporary period of isolation.

A study published in 2005 confirmed that the ''major'' group was distinct from the ''cinereus'' and ''minor'' groups and that along with ''P. m. bokharensis'' it diverged from these two groups around 1.5 million years ago. The divergence between the ''bokharensis'' and ''major'' groups was estimated to have been about half a million years ago. The study also examined hybrids between representatives of the ''major'' and ''minor'' groups in the Amur Valley where the two meet. Hybrids were rare, suggesting that there were some reproductive barriers between the two groups. The study recommended that the two eastern groups be split out as new species, the cinereous tit (''Parus cinereus''), and the Japanese tit (''Parus minor''), but that the Turkestan tit be lumped in with the great tit. This taxonomy has been followed by some authorities, for example the '' IOC World Bird List''. The ''Handbook of the Birds of the World

The ''Handbook of the Birds of the World'' (HBW) is a multi-volume series produced by the Spanish publishing house Lynx Edicions in partnership with BirdLife International. It is the first handbook to cover every known living species of bird. ...

'' volume treating the ''Parus'' species went for the more traditional classification, treating the Turkestan tit as a separate species but retaining the Japanese and cinereous tits with the great tit, a move that has not been without criticism.

The nominate subspecies

In biological classification, subspecies (: subspecies) is a rank below species, used for populations that live in different areas and vary in size, shape, or other physical characteristics ( morphology), but that can successfully interbreed. ...

of the great tit is the most widespread, its range stretching from the Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula ( ), also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in south-western Europe. Mostly separated from the rest of the European landmass by the Pyrenees, it includes the territories of peninsular Spain and Continental Portugal, comprisin ...

to the Amur Valley and from Scandinavia

Scandinavia is a subregion#Europe, subregion of northern Europe, with strong historical, cultural, and linguistic ties between its constituent peoples. ''Scandinavia'' most commonly refers to Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. It can sometimes also ...

to the Middle East. The other subspecies have much more restricted distributions, four being restricted to islands and the remainder of the ''P. m. major'' subspecies representing former glacial refuge populations. The dominance of a single, morphologically uniform subspecies over such a large area suggests that the nominate race rapidly recolonised a large area after the last glacial epoch. This hypothesis is supported by genetic studies which suggest a geologically recent genetic bottleneck followed by a rapid population expansion.

The genus ''Parus'' once held most of the species of tit in the family Paridae, but morphological and genetic studies led to the splitting of that large genus in 1998. The great tit was retained in ''Parus'', which along with '' Cyanistes'' comprises a lineage of tits known as the "non-hoarders", with reference to the hoarding

Hoarding is the act of engaging in excessive acquisition of items that are not needed or for which no space is available.

Civil unrest or the threat of natural disasters may lead people to hoard foodstuffs, water, gasoline, and other essentials ...

behaviour of members of the other clade. The genus ''Parus'' is still the largest in the family, but may be split again. Other than those species formerly considered to be subspecies, the great tit's closest relatives are the white-naped and green-backed tits of southern Asia. Hybrids with tits outside the genus ''Parus'' are very rare, but have been recorded with blue tit, coal tit, and probably marsh tit.

Subspecies

There are currently 15 recognised subspecies of great tit: *''P. m. newtoni'', described by Pražák in 1894, is found across theBritish Isles

The British Isles are an archipelago in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean off the north-western coast of continental Europe, consisting of the islands of Great Britain, Ireland, the Isle of Man, the Inner Hebrides, Inner and Outer Hebr ...

.

*''P. m. major'', described by Linnaeus

Carl Linnaeus (23 May 1707 – 10 January 1778), also known after ennoblement in 1761 as Carl von Linné,#Blunt, Blunt (2004), p. 171. was a Swedish biologist and physician who formalised binomial nomenclature, the modern system of naming o ...

in 1758, is found throughout much of Europe, Asia Minor

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

, northern and eastern Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan, officially the Republic of Kazakhstan, is a landlocked country primarily in Central Asia, with a European Kazakhstan, small portion in Eastern Europe. It borders Russia to the Kazakhstan–Russia border, north and west, China to th ...

, southern Siberia

Siberia ( ; , ) is an extensive geographical region comprising all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has formed a part of the sovereign territory of Russia and its predecessor states ...

and northern Mongolia

Mongolia is a landlocked country in East Asia, bordered by Russia to the north and China to the south and southeast. It covers an area of , with a population of 3.5 million, making it the world's List of countries and dependencies by po ...

, as far as the mid-Amur Valley.

*''P. m. excelsus'', described by Buvry in 1857, is found in northwestern Africa.

*''P. m. corsus'', described by Kleinschmidt in 1903, is found in Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic, is a country on the Iberian Peninsula in Southwestern Europe. Featuring Cabo da Roca, the westernmost point in continental Europe, Portugal borders Spain to its north and east, with which it share ...

, southern Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

, and Corsica

Corsica ( , , ; ; ) is an island in the Mediterranean Sea and one of the Regions of France, 18 regions of France. It is the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, fourth-largest island in the Mediterranean and lies southeast of the Metro ...

.

*''P. m. mallorcae'', described by von Jordans in 1913, is found in the Balearic Islands

The Balearic Islands are an archipelago in the western Mediterranean Sea, near the eastern coast of the Iberian Peninsula. The archipelago forms a Provinces of Spain, province and Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Spain, ...

.

*''P. m. ecki'', described by von Jordans in 1970, is found on Sardinia

Sardinia ( ; ; ) is the Mediterranean islands#By area, second-largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, and one of the Regions of Italy, twenty regions of Italy. It is located west of the Italian Peninsula, north of Tunisia an ...

.

*''P. m. niethammeri'', described by von Jordans in 1970, is found on Crete

Crete ( ; , Modern Greek, Modern: , Ancient Greek, Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the List of islands by area, 88th largest island in the world and the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, fifth la ...

.

*''P. m. aphrodite'', described by Madarász in 1901, is found in southern Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

, southern Greece

Greece, officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. Located on the southern tip of the Balkan peninsula, it shares land borders with Albania to the northwest, North Macedonia and Bulgaria to the north, and Turkey to th ...

, Cyprus

Cyprus (), officially the Republic of Cyprus, is an island country in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Situated in West Asia, its cultural identity and geopolitical orientation are overwhelmingly Southeast European. Cyprus is the List of isl ...

and the Aegean Islands.

*''P. m. terrasanctae'' was described by Hartert in 1910. It is found in Lebanon

Lebanon, officially the Republic of Lebanon, is a country in the Levant region of West Asia. Situated at the crossroads of the Mediterranean Basin and the Arabian Peninsula, it is bordered by Syria to the north and east, Israel to the south ...

, Israel

Israel, officially the State of Israel, is a country in West Asia. It Borders of Israel, shares borders with Lebanon to the north, Syria to the north-east, Jordan to the east, Egypt to the south-west, and the Mediterranean Sea to the west. Isr ...

, Jordan

Jordan, officially the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, is a country in the Southern Levant region of West Asia. Jordan is bordered by Syria to the north, Iraq to the east, Saudi Arabia to the south, and Israel and the occupied Palestinian ter ...

and Syria

Syria, officially the Syrian Arab Republic, is a country in West Asia located in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Levant. It borders the Mediterranean Sea to the west, Turkey to Syria–Turkey border, the north, Iraq to Iraq–Syria border, t ...

.

*''P. m. karelini'', described by Zarudny in 1910, is found in southeastern Azerbaijan

Azerbaijan, officially the Republic of Azerbaijan, is a Boundaries between the continents, transcontinental and landlocked country at the boundary of West Asia and Eastern Europe. It is a part of the South Caucasus region and is bounded by ...

and northwestern Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) and also known as Persia, is a country in West Asia. It borders Iraq to the west, Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Armenia to the northwest, the Caspian Sea to the north, Turkmenistan to the nort ...

.

*''P. m. blandfordi'' was described by Pražák in 1894. It is found in north central and southwestern Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) and also known as Persia, is a country in West Asia. It borders Iraq to the west, Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Armenia to the northwest, the Caspian Sea to the north, Turkmenistan to the nort ...

.

*''P. m. bokharensis'' was described by Lichtenstein in 1823. It is found in southern Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan, officially the Republic of Kazakhstan, is a landlocked country primarily in Central Asia, with a European Kazakhstan, small portion in Eastern Europe. It borders Russia to the Kazakhstan–Russia border, north and west, China to th ...

, Uzbekistan

, image_flag = Flag of Uzbekistan.svg

, image_coat = Emblem of Uzbekistan.svg

, symbol_type = Emblem of Uzbekistan, Emblem

, national_anthem = "State Anthem of Uzbekistan, State Anthem of the Republ ...

, Turkmenistan

Turkmenistan is a landlocked country in Central Asia bordered by Kazakhstan to the northwest, Uzbekistan to the north, east and northeast, Afghanistan to the southeast, Iran to the south and southwest and the Caspian Sea to the west. Ash ...

and far north of Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) and also known as Persia, is a country in West Asia. It borders Iraq to the west, Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Armenia to the northwest, the Caspian Sea to the north, Turkmenistan to the nort ...

and Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. It is bordered by Pakistan to the Durand Line, east and south, Iran to the Afghanistan–Iran borde ...

. It was, along with following two subspecies, once treated as separate species.

*''P. m. turkestanicus'', was described by Zarudny & Loudon in 1905, and ranges from east Kazakhstan to extreme north west China and west Mongolia

Mongolia is a landlocked country in East Asia, bordered by Russia to the north and China to the south and southeast. It covers an area of , with a population of 3.5 million, making it the world's List of countries and dependencies by po ...

.

*''P. m. ferghanensis'', was described by Buturlin in 1912, and is found in Tajikistan

Tajikistan, officially the Republic of Tajikistan, is a landlocked country in Central Asia. Dushanbe is the capital city, capital and most populous city. Tajikistan borders Afghanistan to the Afghanistan–Tajikistan border, south, Uzbekistan to ...

and Kyrgyzstan

Kyrgyzstan, officially the Kyrgyz Republic, is a landlocked country in Central Asia lying in the Tian Shan and Pamir Mountains, Pamir mountain ranges. Bishkek is the Capital city, capital and List of cities in Kyrgyzstan, largest city. Kyrgyz ...

.

*''P. m. kapustini'', was described by Portenko in 1954, and is found in north west China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

(north west Xinjiang

Xinjiang,; , SASM/GNC romanization, SASM/GNC: Chinese postal romanization, previously romanized as Sinkiang, officially the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (XUAR), is an Autonomous regions of China, autonomous region of the China, People' ...

) to Mongolia

Mongolia is a landlocked country in East Asia, bordered by Russia to the north and China to the south and southeast. It covers an area of , with a population of 3.5 million, making it the world's List of countries and dependencies by po ...

and Siberia

Siberia ( ; , ) is an extensive geographical region comprising all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has formed a part of the sovereign territory of Russia and its predecessor states ...

.

Description

The great tit is large for a tit at in length, and has a distinctive appearance that makes it easy to recognise. The nominate race ''P. major major'' has a bluish-black crown, black neck, throat, bib and head, and white cheeks and ear coverts. The breast is bright lemon-yellow and there is a broad black mid-line stripe running from the bib to vent. There is a dull white spot on the neck turning to greenish yellow on the uppernape

The nape is the back of the neck. In technical anatomical/medical terminology, the nape is also called the nucha (from the Medieval Latin rendering of the Arabic , ). The corresponding adjective is ''nuchal'', as in the term ''nuchal rigidity'' ...

. The rest of the nape and back are green tinged with olive. The wing-coverts are green, the rest of the wing is bluish-grey with a white wing-bar. The tail is bluish grey with white outer tips. The plumage

Plumage () is a layer of feathers that covers a bird and the pattern, colour, and arrangement of those feathers. The pattern and colours of plumage differ between species and subspecies and may vary with age classes. Within species, there can b ...

of the female is similar to that of the male except that the colours are overall duller; the bib is less intensely black, as is the line running down the belly, which is also narrower and sometimes broken. Young birds are like the female, except that they have dull olive-brown napes and necks, greyish rumps, and greyer tails, with less defined white tips.

There is some variation in the subspecies. ''P. m. newtoni'' is like the nominate race but has a slightly longer bill, the mantle is slightly deeper green, there is less white on the tail tips, and the ventral mid-line stripe is broader on the belly. ''P. m. corsus'' also resembles the nominate form but has duller upperparts, less white in the tail and less yellow in the nape. ''P. m. mallorcae'' is like the nominate subspecies, but has a larger bill, greyer-blue upperparts and slightly paler underparts. ''P. m. ecki'' is like ''P. m. mallorcae'' except with bluer upperparts and paler underparts. ''P. m. excelsus'' is similar to the nominate race but has much brighter green upperparts, bright yellow underparts and no (or very little) white on the tail. ''P. m. aphrodite'' has darker, more olive-grey upperparts, and the underparts are more yellow to pale cream. ''P. m. niethammeri'' is similar to ''P. m. aphrodite'' but the upperparts are duller and less green, and the underparts are pale yellow. ''P. m. terrasanctae'' resembles the previous two subspecies but has slightly paler upperparts. ''P. m. blandfordi'' is like the nominate but with a greyer mantle and scapulars and pale yellow underparts, and ''P. m. karelini'' is intermediate between the nominate and ''P. m. blandfordi'', and lacks white on the tail. The plumage of ''P. m. bokharensis'' is much greyer, pale creamy white to washed out grey underparts, a larger white cheep patch, a grey tail, wings, back and nape. It is also slightly smaller, with a smaller bill but longer tail. The situation is similar for the two related subspecies in the Turkestan tit group. ''P. m. turkestanicus'' is like ''P. m. bokharensis'' but with a larger bill and darker upperparts. ''P. m. ferghanensis'' is like ''P. m. bokharensis'' but with a smaller bill, darker grey on the flanks and a more yellow wash on the juvenile birds.

There is some variation in the subspecies. ''P. m. newtoni'' is like the nominate race but has a slightly longer bill, the mantle is slightly deeper green, there is less white on the tail tips, and the ventral mid-line stripe is broader on the belly. ''P. m. corsus'' also resembles the nominate form but has duller upperparts, less white in the tail and less yellow in the nape. ''P. m. mallorcae'' is like the nominate subspecies, but has a larger bill, greyer-blue upperparts and slightly paler underparts. ''P. m. ecki'' is like ''P. m. mallorcae'' except with bluer upperparts and paler underparts. ''P. m. excelsus'' is similar to the nominate race but has much brighter green upperparts, bright yellow underparts and no (or very little) white on the tail. ''P. m. aphrodite'' has darker, more olive-grey upperparts, and the underparts are more yellow to pale cream. ''P. m. niethammeri'' is similar to ''P. m. aphrodite'' but the upperparts are duller and less green, and the underparts are pale yellow. ''P. m. terrasanctae'' resembles the previous two subspecies but has slightly paler upperparts. ''P. m. blandfordi'' is like the nominate but with a greyer mantle and scapulars and pale yellow underparts, and ''P. m. karelini'' is intermediate between the nominate and ''P. m. blandfordi'', and lacks white on the tail. The plumage of ''P. m. bokharensis'' is much greyer, pale creamy white to washed out grey underparts, a larger white cheep patch, a grey tail, wings, back and nape. It is also slightly smaller, with a smaller bill but longer tail. The situation is similar for the two related subspecies in the Turkestan tit group. ''P. m. turkestanicus'' is like ''P. m. bokharensis'' but with a larger bill and darker upperparts. ''P. m. ferghanensis'' is like ''P. m. bokharensis'' but with a smaller bill, darker grey on the flanks and a more yellow wash on the juvenile birds.

The colour of the male bird's breast has been shown to correlate with stronger sperm, and is one way that the male demonstrates his reproductive superiority to females. Higher levels of

The colour of the male bird's breast has been shown to correlate with stronger sperm, and is one way that the male demonstrates his reproductive superiority to females. Higher levels of carotenoid

Carotenoids () are yellow, orange, and red organic pigments that are produced by plants and algae, as well as several bacteria, archaea, and fungi. Carotenoids give the characteristic color to pumpkins, carrots, parsnips, corn, tomatoes, cana ...

increase the intensity of the yellow of the breast its colour, and also enable the sperm to better withstand the onslaught of free radical

A daughter category of ''Ageing'', this category deals only with the biological aspects of ageing.

Ageing

Biogerontology

Biological processes

Causes of death

Cellular processes

Gerontology

Life extension

Metabolic disorders

Metabolism

...

s. Carotenoids cannot be synthesized by the bird and have to be obtained from food, so a bright colour in a male demonstrates his ability to obtain good nutrition. However, the saturation of the yellow colour is also influenced by environmental factors, such as weather conditions. The width of the male's ventral stripe, which varies with individual, is selected for by females, with higher quality females apparently selecting males with wider stripes.

Voice

The great tit is, like other tits, a vocal bird, and has up to 40 types of calls and songs. The calls are generally the same between the sexes, but the male is much more vocal and the female rarely calls. Soft single notes such as "pit", "spick", or "chit" are used as contact calls. A loud "tink" is used by adult males as an alarm or in territorial disputes. One of the most familiar is a "teacher, teacher", often likened to a squeaky wheelbarrow wheel, which is used in proclaiming ownership of a territory. In former times, English folk considered the "saw-sharpening" call to be a foretelling of rain. Tit calls from different geographic regions show some variation, and tits from the two south Asian groups recently split from the great tit do not recognise or react to the calls of the temperate great tits.

One explanation for the great tit's wide repertoire is the Beau Geste hypothesis. The eponymous hero of the novel propped dead soldiers against the battlements to give the impression that his fort was better defended than was really the case. Similarly, the multiplicity of calls gives the impression that the tit's territory is more densely occupied than it actually is. Whether the theory is correct or not, those birds with large vocabularies are socially dominant and breed more successfully.

The great tit is, like other tits, a vocal bird, and has up to 40 types of calls and songs. The calls are generally the same between the sexes, but the male is much more vocal and the female rarely calls. Soft single notes such as "pit", "spick", or "chit" are used as contact calls. A loud "tink" is used by adult males as an alarm or in territorial disputes. One of the most familiar is a "teacher, teacher", often likened to a squeaky wheelbarrow wheel, which is used in proclaiming ownership of a territory. In former times, English folk considered the "saw-sharpening" call to be a foretelling of rain. Tit calls from different geographic regions show some variation, and tits from the two south Asian groups recently split from the great tit do not recognise or react to the calls of the temperate great tits.

One explanation for the great tit's wide repertoire is the Beau Geste hypothesis. The eponymous hero of the novel propped dead soldiers against the battlements to give the impression that his fort was better defended than was really the case. Similarly, the multiplicity of calls gives the impression that the tit's territory is more densely occupied than it actually is. Whether the theory is correct or not, those birds with large vocabularies are socially dominant and breed more successfully.

Distribution, movements and habitat

The great tit has a wide distribution across much of Eurasia. It can be found across all of Europe except for

The great tit has a wide distribution across much of Eurasia. It can be found across all of Europe except for Iceland

Iceland is a Nordic countries, Nordic island country between the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic and Arctic Oceans, on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge between North America and Europe. It is culturally and politically linked with Europe and is the regi ...

and northern Scandinavia

Scandinavia is a subregion#Europe, subregion of northern Europe, with strong historical, cultural, and linguistic ties between its constituent peoples. ''Scandinavia'' most commonly refers to Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. It can sometimes also ...

, including numerous Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern ...

islands. In North Africa it lives in Morocco

Morocco, officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It has coastlines on the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria to Algeria–Morocc ...

, Algeria

Algeria, officially the People's Democratic Republic of Algeria, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It is bordered to Algeria–Tunisia border, the northeast by Tunisia; to Algeria–Libya border, the east by Libya; to Alger ...

and Tunisia

Tunisia, officially the Republic of Tunisia, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It is bordered by Algeria to the west and southwest, Libya to the southeast, and the Mediterranean Sea to the north and east. Tunisia also shares m ...

. It also occurs across the Middle East

The Middle East (term originally coined in English language) is a geopolitical region encompassing the Arabian Peninsula, the Levant, Turkey, Egypt, Iran, and Iraq.

The term came into widespread usage by the United Kingdom and western Eur ...

, and parts of Central Asia

Central Asia is a region of Asia consisting of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. The countries as a group are also colloquially referred to as the "-stans" as all have names ending with the Persian language, Pers ...

from northern Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) and also known as Persia, is a country in West Asia. It borders Iraq to the west, Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Armenia to the northwest, the Caspian Sea to the north, Turkmenistan to the nort ...

and Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. It is bordered by Pakistan to the Durand Line, east and south, Iran to the Afghanistan–Iran borde ...

to Mongolia

Mongolia is a landlocked country in East Asia, bordered by Russia to the north and China to the south and southeast. It covers an area of , with a population of 3.5 million, making it the world's List of countries and dependencies by po ...

, as well as across northern Asia from the Urals as far east as northern China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

and the Amur Valley.

The great tit occupies a range of habitats. It is most commonly found in open deciduous woodland

A woodland () is, in the broad sense, land covered with woody plants (trees and shrubs), or in a narrow sense, synonymous with wood (or in the U.S., the '' plurale tantum'' woods), a low-density forest forming open habitats with plenty of sunli ...

, mixed forests, forest edges and gardens. In dense forests, including conifer forests it prefers forest clearings. In northern Siberia

Siberia ( ; , ) is an extensive geographical region comprising all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has formed a part of the sovereign territory of Russia and its predecessor states ...

it lives in boreal taiga

Taiga or tayga ( ; , ), also known as boreal forest or snow forest, is a biome characterized by coniferous forests consisting mostly of pines, spruces, and larches. The taiga, or boreal forest, is the world's largest land biome. In North A ...

. In North Africa it rather resides in oak forests as well as stands of Atlas cedar and even palm groves. In the east of its range in Siberia, Mongolia and China it favours riverine willow

Willows, also called sallows and osiers, of the genus ''Salix'', comprise around 350 species (plus numerous hybrids) of typically deciduous trees and shrubs, found primarily on moist soils in cold and temperate regions.

Most species are known ...

and birch forest. Riverine woodlands of willows, poplars are among the habitats of the Turkestan subspecies, as well as low scrubland

Shrubland, scrubland, scrub, brush, or bush is a plant community characterized by vegetation dominance (ecology), dominated by shrubs, often also including grasses, herbaceous plant, herbs, and geophytes. Shrubland may either occur naturally o ...

, oases; at higher altitudes it occupies habitats ranging from dense deciduous and coniferous forests to open areas with scattered trees.

The great tit is generally not migratory. Pairs will usually remain near or in their territory

A territory is an area of land, sea, or space, belonging or connected to a particular country, person, or animal.

In international politics, a territory is usually a geographic area which has not been granted the powers of self-government, ...

year round, even in the northern parts of their range. Young birds will disperse from their parents' territory, but usually not far. Populations may become irruptive in poor or harsh winters, meaning that groups of up to a thousand birds may unpredictably move from northern Europe to the Baltic and also to Netherlands, Britain, even as far as the southern Balkans

The Balkans ( , ), corresponding partially with the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throug ...

.

The great tit was unsuccessfully introduced into the United States; birds were set free near Cincinnati, Ohio

Cincinnati ( ; colloquially nicknamed Cincy) is a city in Hamilton County, Ohio, United States, and its county seat. Settled in 1788, the city is located on the northern side of the confluence of the Licking River (Kentucky), Licking and Ohio Ri ...

between 1872 and 1874 but failed to become established. Suggestions that they were an excellent control measure for codling moths nearly led to their introduction to some new areas particularly in the United States of America, however this plan was not implemented. A small population is present in the upper Midwest, believed to be the descendants of birds liberated in Chicago in 2002 along with European goldfinches, Eurasian jays, common chaffinches, European greenfinches, saffron finch

The saffron finch (''Sicalis flaveola'') is a tanager from South America that is common in open and semi-open areas in lowlands outside the Amazon Basin. They have a wide distribution in Colombia, northern Venezuela (where it is called "canari ...

es, blue tits and Eurasian linnets, although sightings of some of these species pre-date the supposed introduction date. Birds were introduced to the Almaty Province in what is now Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan, officially the Republic of Kazakhstan, is a landlocked country primarily in Central Asia, with a European Kazakhstan, small portion in Eastern Europe. It borders Russia to the Kazakhstan–Russia border, north and west, China to th ...

in 1960–61 and became established, although their present status is unclear.

Behaviour

Diet and feeding

insect

Insects (from Latin ') are Hexapoda, hexapod invertebrates of the class (biology), class Insecta. They are the largest group within the arthropod phylum. Insects have a chitinous exoskeleton, a three-part body (Insect morphology#Head, head, ...

s and spider

Spiders (order (biology), order Araneae) are air-breathing arthropods that have eight limbs, chelicerae with fangs generally able to inject venom, and spinnerets that extrude spider silk, silk. They are the largest order of arachnids and ran ...

s which they capture by foliage

A leaf (: leaves) is a principal appendage of the stem of a vascular plant, usually borne laterally above ground and specialized for photosynthesis. Leaves are collectively called foliage, as in "autumn foliage", while the leaves, stem, f ...

gleaning. Their larger invertebrate

Invertebrates are animals that neither develop nor retain a vertebral column (commonly known as a ''spine'' or ''backbone''), which evolved from the notochord. It is a paraphyletic grouping including all animals excluding the chordata, chordate s ...

prey include cockroach

Cockroaches (or roaches) are insects belonging to the Order (biology), order Blattodea (Blattaria). About 30 cockroach species out of 4,600 are associated with human habitats. Some species are well-known Pest (organism), pests.

Modern cockro ...

es, grasshopper

Grasshoppers are a group of insects belonging to the suborder Caelifera. They are amongst what are possibly the most ancient living groups of chewing herbivorous insects, dating back to the early Triassic around 250 million years ago.

Grassh ...

s and crickets, lacewings, earwigs, bugs (Hemiptera

Hemiptera (; ) is an order of insects, commonly called true bugs, comprising more than 80,000 species within groups such as the cicadas, aphids, planthoppers, leafhoppers, assassin bugs, bed bugs, and shield bugs. They range in size from ...

), ants, flies (Diptera), caddisflies, beetles, scorpionflies, harvestmen, bees and wasps, snails and woodlice. During the breeding season, the tits prefer to feed protein-rich caterpillar

Caterpillars ( ) are the larval stage of members of the order Lepidoptera (the insect order comprising butterflies and moths).

As with most common names, the application of the word is arbitrary, since the larvae of sawflies (suborder ...

s to their young. A study published in 2007 found that great tits helped to reduce caterpillar damage in apple orchards by as much as 50%. Nestlings also undergo a period in their early development where they are fed a number of spiders, possibly for nutritional reasons. In autumn and winter, when insect prey becomes scarcer, great tits add berries

A berry is a small, pulpy, and often edible fruit. Typically, berries are juicy, rounded, brightly colored, sweet, sour or tart, and do not have a stone fruit, stone or pit (fruit), pit although many wikt:pip#Etymology 2, pips or seeds may be p ...

and seed

In botany, a seed is a plant structure containing an embryo and stored nutrients in a protective coat called a ''testa''. More generally, the term "seed" means anything that can be Sowing, sown, which may include seed and husk or tuber. Seeds ...

s to their diet. Seeds and fruit

In botany, a fruit is the seed-bearing structure in flowering plants (angiosperms) that is formed from the ovary after flowering.

Fruits are the means by which angiosperms disseminate their seeds. Edible fruits in particular have long propaga ...

usually come from deciduous trees and shrubs, like for instance the seeds of beech

Beech (genus ''Fagus'') is a genus of deciduous trees in the family Fagaceae, native to subtropical (accessory forest element) and temperate (as dominant element of Mesophyte, mesophytic forests) Eurasia and North America. There are 14 accepted ...

and hazel. Where it is available they will readily take table scraps, peanut

The peanut (''Arachis hypogaea''), also known as the groundnut, goober (US), goober pea, pindar (US) or monkey nut (UK), is a legume crop grown mainly for its edible seeds. It is widely grown in the tropics and subtropics by small and large ...

s and seeds from bird tables. In particularly severe winters they may consume 44% of their body weight in sunflower seeds. They often forage on the ground, particularly in years with high beech

Beech (genus ''Fagus'') is a genus of deciduous trees in the family Fagaceae, native to subtropical (accessory forest element) and temperate (as dominant element of Mesophyte, mesophytic forests) Eurasia and North America. There are 14 accepted ...

mast production. Great tits, along with other tits, will join winter mixed-species foraging flock

A mixed-species feeding flock, also termed a mixed-species foraging flock, mixed hunting party or informally bird wave, is a flock (birds), flock of usually insectivorous birds of different species that join each other and move together while fora ...

s.

Large food items, such as large seeds or prey, are dealt with by "hold-hammering", where the item is held with one or both feet and then struck with the bill until it is ready to eat. Using this method, a great tit can get into a hazelnut

The hazelnut is the fruit of the hazel tree and therefore includes any of the nuts deriving from species of the genus '' Corylus'', especially the nuts of the species ''Corylus avellana''. They are also known as cobnuts or filberts according to ...

in about twenty minutes. When feeding young, adults will hammer off the heads of large insects to make them easier to consume, and remove the gut from caterpillars so that the tannin

Tannins (or tannoids) are a class of astringent, polyphenolic biomolecules that bind to and Precipitation (chemistry), precipitate proteins and various other organic compounds including amino acids and alkaloids. The term ''tannin'' is widel ...

s in the gut will not retard the chick's growth.

Great tits combine dietary versatility with a considerable amount of intelligence and the ability to solve problems with insight learning, that is to solve a problem through insight rather than trial and error. In England, great tits learned to break the foil caps of milk bottles delivered at the doorstep of homes to obtain the cream at the top. This behaviour, first noted in 1921, spread rapidly in the next two decades. In 2009, great tits were reported killing, and eating the brains of roosting pipistrelle bats. This is the first time a songbird has been recorded preying on bats. The tits only do this during winter when the bats are hibernating and other food is scarce. They have also been recorded using tools

A tool is an object that can extend an individual's ability to modify features of the surrounding environment or help them accomplish a particular task. Although many animals use simple tools, only human beings, whose use of stone tools dates ...

, using a conifer needle in the bill to extract larvae from a hole in a tree.

Breeding

Great tits are monogamous breeders and establish breeding territories. These territories are established in late January and defence begins in late winter or early spring. Territories are usually reoccupied in successive years, even if one of the pair dies, so long as the brood is raised successfully. Females are likely to disperse to new territories if their nest is predated the previous year. If the pair divorces for some reason then the birds will disperse, with females travelling further than males to establish new territories. Although the great tit is socially monogamous, extra-pair copulations are frequent. One study in Germany found that 40% of nests contained some offspring fathered by parents other than the breeding male and that 8.5% of all chicks were the result of cuckoldry. Adult males tend to have a higher reproductive success compared to sub-adults.

Great tits are cavity nesters, breeding in a hole that is usually inside a tree, although occasionally in a wall or rock face, and they will readily take to nest boxes. The nest inside the cavity is built by the female, and is made of plant fibres, grasses, moss, hair, wool and feathers. The number in the

Great tits are cavity nesters, breeding in a hole that is usually inside a tree, although occasionally in a wall or rock face, and they will readily take to nest boxes. The nest inside the cavity is built by the female, and is made of plant fibres, grasses, moss, hair, wool and feathers. The number in the clutch

A clutch is a mechanical device that allows an output shaft to be disconnected from a rotating input shaft. The clutch's input shaft is typically attached to a motor, while the clutch's output shaft is connected to the mechanism that does th ...

is often very large, as many as 18, but five to twelve is more common. Clutch size is smaller when birds start laying later, and is also lower when the density of competitors is higher. Second broods tend to have smaller clutches. Insularity also affects clutch size, with great tits on offshore islands laying smaller clutches with larger eggs than mainland birds. The eggs are white with red spots. The female undertakes all incubation duties, and is fed by the male during incubation. The bird is a close sitter, hissing when disturbed. The timing of hatching, which is best synchronised with peak availability of prey, can be manipulated when environmental conditions change after the laying of the first egg by delaying the beginning of incubation, laying more eggs or pausing during incubation. The incubation period is between 12 and 15 days.

The chicks, like those of all tits, hatch unfeathered and blind. Once feathers begin to erupt, the nestlings are unusual for

The chicks, like those of all tits, hatch unfeathered and blind. Once feathers begin to erupt, the nestlings are unusual for altricial

Precocial species in birds and mammals are those in which the young are relatively mature and mobile from the moment of birth or hatching. They are normally nidifugous, meaning that they leave the nest shortly after birth or hatching. Altricial ...

birds in having plumage coloured with carotenoid

Carotenoids () are yellow, orange, and red organic pigments that are produced by plants and algae, as well as several bacteria, archaea, and fungi. Carotenoids give the characteristic color to pumpkins, carrots, parsnips, corn, tomatoes, cana ...

s similar to their parents (in most species it is dun-coloured to avoid predation). The nape

The nape is the back of the neck. In technical anatomical/medical terminology, the nape is also called the nucha (from the Medieval Latin rendering of the Arabic , ). The corresponding adjective is ''nuchal'', as in the term ''nuchal rigidity'' ...

is yellow and attracts the attention of the parents by its ultraviolet

Ultraviolet radiation, also known as simply UV, is electromagnetic radiation of wavelengths of 10–400 nanometers, shorter than that of visible light, but longer than X-rays. UV radiation is present in sunlight and constitutes about 10% of ...

reflectance. This may be to make them easier to find in low light, or be a signal of fitness to win the parents' attention. This patch turns white after the first moult at age two months, and diminishes in size as the bird grows.

Chicks are fed by both parents, usually receiving of food a day. Both parents provision the chicks with food and aid in nest sanitation by removing faecal packets, with no difference in the feeding effort between the sexes. The nestling period is between 16 and 22 days, with chicks being independent of the parents eight days after fledging. Feeding of the fledgling may continue after independence, lasting up to 25 days in chicks from the first brood, but as long as 50 days in the second brood. Nestlings from second broods have weaker immune systems and body condition than those from first broods, and hence have a lower juvenile survival rate.

Inbreeding depression

Inbreeding depression is the reduced biological fitness caused by loss of genetic diversity as a consequence of inbreeding, the breeding of individuals closely related genetically. This loss of genetic diversity results from small population siz ...

occurs when the offspring produced as a result of a mating between close relatives show reduced fitness. The reduced fitness is generally considered to be a consequence of the increased expression of deleterious recessive alleles in these offspring. In natural populations of ''P. major'', inbreeding is avoided by dispersal of individuals from their birthplace, which reduces the chance of mating with a close relative.

Ecology

TheEurasian sparrowhawk

The Eurasian sparrowhawk (''Accipiter nisus''), also known as the northern sparrowhawk or simply the sparrowhawk, is a small bird of prey in the family Accipitridae. Adult male Eurasian sparrowhawks have bluish grey upperparts and orange-barred ...

is a predator of great tits, with the young from second broods being at higher risk partly because of the hawk's greater need for food for its own developing young. The nests of great tits are raided by great spotted woodpeckers, particularly when nesting in certain types of nest boxes. Other nest predators include introduced grey squirrels (in Britain) and least weasels, which are able to take nesting adults as well. A species of biting louse ( Mallophaga) described as ''Rostrinirmus hudeci'' was isolated and described in 1981 from great tits in central Europe. The hen flea ''Ceratophyllus gallinae'' is exceedingly common in the nests of blue and great tits. It was originally a specialist tit flea, but the dry, crowded conditions of chicken runs enabled it to flourish with its new host. This flea is preferentially predated by the clown beetle ''Gnathoncus punctulatus'', The rove beetle

The rove beetles are a family (biology), family (Staphylinidae) of beetles, primarily distinguished by their short elytra (wing covers) that typically leave more than half of their abdominal segments exposed. With over 66,000 species in thousand ...

''Microglotta pulla'' also feeds on fleas and their larvae. Although these beetles often remain in deserted nests, they can only breed in the elevated temperatures produced by brooding birds, tits being the preferred hosts. Great tits compete with the pied flycatcher for nesting boxes, and can kill prospecting flycatcher males. Incidences of fatal competition are more frequent when nesting times overlap, and climate change

Present-day climate change includes both global warming—the ongoing increase in Global surface temperature, global average temperature—and its wider effects on Earth's climate system. Climate variability and change, Climate change in ...

has led to greater synchrony of nesting between the two species and flycatcher deaths. Having killed the flycatchers, the great tits may consume their brains.

Physiology

Great tits have been found to possess special physiological adaptations for cold environments. When preparing for winter months, the great tit can increase how thermogenic (heat producing) its blood is. The mechanism for this adaptation is a seasonal increase in mitochondrial volume and mitochondrial respiration in red blood cells and increased uncoupling of the electron transport from ATP production. As a result, the energy that would have been used to make ATP is released as heat and their blood becomes more thermogenic. In the face of winter food shortages, the great tit has also shown a type of peripheral vasoconstriction (constriction of blood vessels) to reduce heat loss and cold injury. Reduced cold injury and heat loss is mediated by the great tits' counter-current vascular arrangements, and peripheral vasoconstriction in major vessels in and around the birds' bill and legs. This mechanism allows uninsulated regions (i.e., bill and legs) to remain close to the surrounding temperature. In response to food restriction, the great tits' bill temperature dropped, and once food availably was increased, bill temperatures gradually returned to normal. Vasoconstriction of blood vessels in the bill not only serves as an energy saving mechanism, but also reduces the amount of heat transferred from core body tissues to the skin (via cutaneous vasodilation), which, in turn, reduces heat loss rate by lowering skin temperature relative to the environment.Relationship with humans

The great tit is a popular garden bird due to its acrobatic performances when feeding on nuts or seed. Its willingness to move into nest boxes has made it a valuable study subject in

The great tit is a popular garden bird due to its acrobatic performances when feeding on nuts or seed. Its willingness to move into nest boxes has made it a valuable study subject in ornithology

Ornithology, from Ancient Greek ὄρνις (''órnis''), meaning "bird", and -logy from λόγος (''lógos''), meaning "study", is a branch of zoology dedicated to the study of birds. Several aspects of ornithology differ from related discip ...

; it has been particularly useful as a model for the study of the evolution of various life-history traits, particularly clutch size. A study of a literature database search found 1,349 articles relating to ''Parus major'' for the period between 1969 and 2002.

The great tit has generally adjusted to human modifications of the environment. It is more common and has better breeding success in areas with undisturbed forest cover, but it has adapted well to human-modified habitats, and can be very common in urban areas. For example, the breeding population in the city of Sheffield

Sheffield is a city in South Yorkshire, England, situated south of Leeds and east of Manchester. The city is the administrative centre of the City of Sheffield. It is historically part of the West Riding of Yorkshire and some of its so ...

(a city of half a million people) has been estimated at some 17,000 individuals. In adapting to human environments its song has been observed to change in noise-polluted urban environments. In areas with low frequency background noise pollution, the song has a higher frequency than in quieter areas. This tit has expanded its range, moving northwards into Scandinavia and Scotland, and south into Israel and Egypt. The total population is estimated at between 300 and 1,100 million birds in a range of 32.4 million km2 (12.5 million sq mi). While there have been some localised declines in population in areas with poorer quality habitats, its large range and high numbers mean that the great tit is not considered to be threatened, and it is classed as least concern

A least-concern species is a species that has been evaluated and categorized by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) as not being a focus of wildlife conservation because the specific species is still plentiful in the wil ...

on the IUCN Red List

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species, also known as the IUCN Red List or Red Data Book, founded in 1964, is an inventory of the global conservation status and extinction risk of biological ...

.

References

External links

*RSPB page

Song sample

BBC fact file

Ageing and sexing (PDF; 2.5 MB) by Javier Blasco-Zumeta & Gerd-Michael Heinze

Great tit videos, photos & sounds

on the Internet Bird Collection

Titbox and the jay - video

{{Good article great tit Birds of Eurasia great tit great tit