Great Hippocampus Question on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Great Hippocampus Question was a 19th-century scientific controversy about the

Huxley was among the friends rallying round the publication of Darwin's ''

Huxley was among the friends rallying round the publication of Darwin's '' Gorillas became the topic of the day with the return of the explorer

Gorillas became the topic of the day with the return of the explorer

It then recounts Huxley's ripostes, and:

The poem was actually by the eminent palaeontologist Sir Philip Egerton who, as a trustee of the

It then recounts Huxley's ripostes, and:

The poem was actually by the eminent palaeontologist Sir Philip Egerton who, as a trustee of the

At the 1862

At the 1862

Huxley expanded his lectures for working men into a book titled '' Evidence as to Man's Place in Nature'', published in 1863. His intention was expressed in a letter to

Huxley expanded his lectures for working men into a book titled '' Evidence as to Man's Place in Nature'', published in 1863. His intention was expressed in a letter to

anatomy

Anatomy () is the branch of morphology concerned with the study of the internal structure of organisms and their parts. Anatomy is a branch of natural science that deals with the structural organization of living things. It is an old scien ...

of ape

Apes (collectively Hominoidea ) are a superfamily of Old World simians native to sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia (though they were more widespread in Africa, most of Asia, and Europe in prehistory, and counting humans are found global ...

and human

Humans (''Homo sapiens'') or modern humans are the most common and widespread species of primate, and the last surviving species of the genus ''Homo''. They are Hominidae, great apes characterized by their Prehistory of nakedness and clothing ...

uniqueness. The dispute between Thomas Henry Huxley

Thomas Henry Huxley (4 May 1825 – 29 June 1895) was an English biologist and anthropologist who specialized in comparative anatomy. He has become known as "Darwin's Bulldog" for his advocacy of Charles Darwin's theory of evolution.

The stor ...

and Richard Owen

Sir Richard Owen (20 July 1804 – 18 December 1892) was an English biologist, comparative anatomy, comparative anatomist and paleontology, palaeontologist. Owen is generally considered to have been an outstanding naturalist with a remarkabl ...

became central to the scientific debate on human evolution

''Homo sapiens'' is a distinct species of the hominid family of primates, which also includes all the great apes. Over their evolutionary history, humans gradually developed traits such as Human skeletal changes due to bipedalism, bipedalism, de ...

that followed Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English Natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci ...

's publication of ''On the Origin of Species

''On the Origin of Species'' (or, more completely, ''On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life'')The book's full original title was ''On the Origin of Species by M ...

''. The name comes from the title of a satire the Reverend Charles Kingsley

Charles Kingsley (12 June 1819 – 23 January 1875) was a broad church priest of the Church of England, a university professor, social reformer, historian, novelist and poet. He is particularly associated with Christian socialism, the workin ...

wrote about the arguments, which in modified form appeared as "the great hippopotamus test" in Kingsley's 1863 book for children, '' The Water-Babies, A Fairy Tale for a Land Baby''. Together with other humorous skits on the topic, this helped to spread and popularise Darwin's ideas on evolution.

The key point that Owen asserted was that only humans had part of the brain then known as the hippocampus minor (now called the calcar avis), and that this gave us our unique abilities. Careful dissection eventually showed that apes and monkeys also have a hippocampus minor.

Background

In October 1836Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English Natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci ...

returned from the ''Beagle'' voyage with fossil collections which the anatomist Richard Owen

Sir Richard Owen (20 July 1804 – 18 December 1892) was an English biologist, comparative anatomy, comparative anatomist and paleontology, palaeontologist. Owen is generally considered to have been an outstanding naturalist with a remarkabl ...

described, contributing to the inception of Darwin's theory

The inception of Darwin's theory occurred during an intensively busy period which began when Charles Darwin returned from the survey voyage of the ''Beagle'', with his reputation as a fossil collector and geologist already established. He was gi ...

of natural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the Heredity, heritable traits characteristic of a population over generation ...

. Darwin outlined his theory in an Essay of 1844, and discussed transmutation with his friend Joseph Dalton Hooker

Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker (30 June 1817 – 10 December 1911) was a British botanist and explorer in the 19th century. He was a founder of geographical botany and Charles Darwin's closest friend. For 20 years he served as director of the Ro ...

. He did not tell Owen, who as the up-and-coming "English Cuvier

Jean Léopold Nicolas Frédéric, baron Cuvier (23 August 1769 – 13 May 1832), known as Georges Cuvier (; ), was a French natural history, naturalist and zoology, zoologist, sometimes referred to as the "founding father of paleontology". Cuv ...

" held the conventional belief that every species was uniquely created and perfectly adapted. Owen's brilliance and political skills made him a leading figure in the scientific establishment, developing ideas of divine archetype

The concept of an archetype ( ) appears in areas relating to behavior, historical psychology, philosophy and literary analysis.

An archetype can be any of the following:

# a statement, pattern of behavior, prototype, "first" form, or a main mo ...

s produced by vague secondary laws similar to a form of theistic evolution

Theistic evolution (also known as theistic evolutionism or God-guided evolution), alternatively called evolutionary creationism, is a view that God acts and creates through laws of nature. Here, God is taken as the primary cause while natural cau ...

, while emphasising the differences separating man from ape. At the end of 1844 the anonymous book ''Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation

''Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation'' is an 1844 work of speculative natural history and philosophy by Robert Chambers. Published anonymously in England, it brought together various ideas of stellar evolution with the progressive tra ...

'' brought wide public interest in transmutation of species

The Transmutation of species and transformism are 18th and early 19th-century ideas about the change of one species into another that preceded Charles Darwin's theory of evolution through natural selection. The French ''Transformisme'' was a ter ...

and the idea that humans were descended from apes, and after a slow initial response, strong condemnation from the scientific establishment.

Darwin discussed his interest in transmutation with friends including Charles Lyell

Sir Charles Lyell, 1st Baronet, (14 November 1797 – 22 February 1875) was a Scottish geologist who demonstrated the power of known natural causes in explaining the earth's history. He is best known today for his association with Charles ...

, and Hooker eventually read Darwin's ''Essay'' in 1847. When Thomas Henry Huxley

Thomas Henry Huxley (4 May 1825 – 29 June 1895) was an English biologist and anthropologist who specialized in comparative anatomy. He has become known as "Darwin's Bulldog" for his advocacy of Charles Darwin's theory of evolution.

The stor ...

savagely reviewed the latest edition of ''Vestiges'' in 1854, Darwin wrote to him, making friends while cautiously admitting to being "almost as unorthodox about species". Huxley had become increasingly irritated by Owen's condescension and manipulation, and having gained a teaching position at the school of mining, began openly attacking Owen's work.

Hippocampus minor

In 1564 a prominent feature on the floor of thelateral ventricles

The lateral ventricles are the two largest ventricles of the brain and contain cerebrospinal fluid. Each cerebral hemisphere contains a lateral ventricle, known as the left or right lateral ventricle, respectively.

Each lateral ventricle resemb ...

of the brain was named the hippocampus

The hippocampus (: hippocampi; via Latin from Ancient Greek, Greek , 'seahorse'), also hippocampus proper, is a major component of the brain of humans and many other vertebrates. In the human brain the hippocampus, the dentate gyrus, and the ...

by Aranzi as its curved shape on each side supposedly reminded him of a seahorse, the ''Hippocampus

The hippocampus (: hippocampi; via Latin from Ancient Greek, Greek , 'seahorse'), also hippocampus proper, is a major component of the brain of humans and many other vertebrates. In the human brain the hippocampus, the dentate gyrus, and the ...

'' (though Mayer mistakenly used the term hippopotamus

The hippopotamus (''Hippopotamus amphibius;'' ; : hippopotamuses), often shortened to hippo (: hippos), further qualified as the common hippopotamus, Nile hippopotamus and river hippopotamus, is a large semiaquatic mammal native to sub-Sahar ...

in 1779, and was followed by several others until 1829). At that same time a ridge on the occipital horn was named the calcar avis, but in 1786 this was renamed the hippocampus minor, with the hippocampus being called the hippocampus major.

Richard Owen

Sir Richard Owen (20 July 1804 – 18 December 1892) was an English biologist, comparative anatomy, comparative anatomist and paleontology, palaeontologist. Owen is generally considered to have been an outstanding naturalist with a remarkabl ...

presented several papers on the anatomical differences between apes and humans, arguing that they had been created separately and stressing the impossibility of apes being transmuted into men. In 1857 he went even further, presenting an authoritative paper to the Linnean Society of London

The Linnean Society of London is a learned society dedicated to the study and dissemination of information concerning natural history, evolution, and Taxonomy (biology), taxonomy. It possesses several important biological specimen, manuscript a ...

on his anatomical studies of primate

Primates is an order (biology), order of mammals, which is further divided into the Strepsirrhini, strepsirrhines, which include lemurs, galagos, and Lorisidae, lorisids; and the Haplorhini, haplorhines, which include Tarsiiformes, tarsiers a ...

brains and asserting that humans were not merely a distinct biological order of primates, as had been accepted by great anatomists such as Carl Linnaeus

Carl Linnaeus (23 May 1707 – 10 January 1778), also known after ennoblement in 1761 as Carl von Linné,#Blunt, Blunt (2004), p. 171. was a Swedish biologist and physician who formalised binomial nomenclature, the modern system of naming o ...

and Georges Cuvier

Jean Léopold Nicolas Frédéric, baron Cuvier (23 August 1769 – 13 May 1832), known as Georges Cuvier (; ), was a French natural history, naturalist and zoology, zoologist, sometimes referred to as the "founding father of paleontology". Cuv ...

, but a separate sub-class of mammal

A mammal () is a vertebrate animal of the Class (biology), class Mammalia (). Mammals are characterised by the presence of milk-producing mammary glands for feeding their young, a broad neocortex region of the brain, fur or hair, and three ...

ia, distinct from all the other primates and mammals generally. Owen supported his argument with a figure by himself of a South American monkey, a figure of a Khoekhoe

Khoikhoi ( /ˈkɔɪkɔɪ/ ''KOY-koy'') (or Khoekhoe in Namibian orthography) are the traditionally nomadic pastoralist indigenous population of South Africa. They are often grouped with the hunter-gatherer San (literally "foragers") peop ...

woman's brain by Friedrich Tiedemann, and of a chimpanzee's brain by Jacobus Schroeder van der Kolk and Willem Vrolik.

While Owen conceded the "all-pervading similitude of structure—every tooth, every bone, strictly homologous" which made it difficult for anatomists to determine the difference between man and ape, he based his new classification on three characteristics which to him distinguished mankind's "highest form of brain", the most important being his claim that only the human brain

The human brain is the central organ (anatomy), organ of the nervous system, and with the spinal cord, comprises the central nervous system. It consists of the cerebrum, the brainstem and the cerebellum. The brain controls most of the activi ...

has a hippocampus minor. To Owen in 1857, this feature together with the extent to which the "posterior lobe" projected beyond the cerebellum

The cerebellum (: cerebella or cerebellums; Latin for 'little brain') is a major feature of the hindbrain of all vertebrates. Although usually smaller than the cerebrum, in some animals such as the mormyrid fishes it may be as large as it or eve ...

and the presence of the posterior horn were how man "fulfills his destiny as the supreme master of this earth and of the lower creation." Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English Natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci ...

commented, "Owen's is a grand Paper; but I cannot swallow Man making a division as distinct from a Chimpanzee, as an ornithorhynchus from a Horse: I wonder what a Chimpanzee wd. say to this?". Owen repeated the paper as the Rede Lecture at the University of Cambridge

The University of Cambridge is a Public university, public collegiate university, collegiate research university in Cambridge, England. Founded in 1209, the University of Cambridge is the List of oldest universities in continuous operation, wo ...

on 10 May 1859 when he was the first to be given an honorary degree by the university.

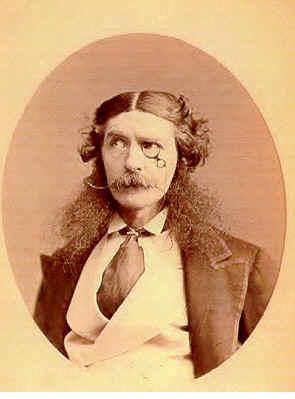

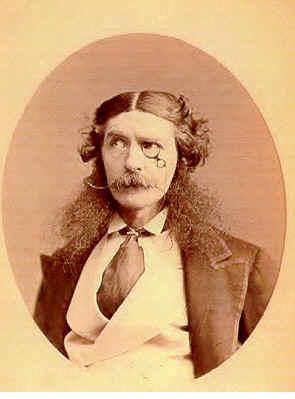

To Thomas Henry Huxley

Thomas Henry Huxley (4 May 1825 – 29 June 1895) was an English biologist and anthropologist who specialized in comparative anatomy. He has become known as "Darwin's Bulldog" for his advocacy of Charles Darwin's theory of evolution.

The stor ...

the claim about the hippocampus minor appeared to be a significant blunder by Owen, and Huxley began systematically dissecting the brains of monkeys, determined that "before I have done with that mendacious humbug I will nail him out, like a kite to a barn door, an example to all evil doers." He did not discuss this in public at this stage, but continued to attack Owen's other ideas, aiming to undermine Owen's status. At his 17 June 1858 Royal Institution

The Royal Institution of Great Britain (often the Royal Institution, Ri or RI) is an organisation for scientific education and research, based in the City of Westminster. It was founded in 1799 by the leading British scientists of the age, inc ...

Croonian Lecture

The Croonian Medal and Lecture is a prestigious award, a medal, and lecture given at the invitation of the Royal Society and the Royal College of Physicians.

Among the papers of William Croone at his death in 1684, was a plan to endow a singl ...

"On the Theory of the Vertebrate Skull", Huxley directly challenged Owen's central idea of archetypes shown by homology, with Owen in the audience. Huxley's aim was to overcome the domination of science by wealthy clergymen led by Owen, in order to create a professional salaried scientific civil service and make science secular

Secularity, also the secular or secularness (from Latin , or or ), is the state of being unrelated or neutral in regards to religion. The origins of secularity can be traced to the Bible itself. The concept was fleshed out through Christian hi ...

. Under Darwin's influence he took up transmutation as a way of dividing science from theology, and in January 1859 argued that "it is as respectable to be modified monkey as modified dirt".

Owen and Huxley debate human and ape brain structure

Huxley was among the friends rallying round the publication of Darwin's ''

Huxley was among the friends rallying round the publication of Darwin's ''On the Origin of Species

''On the Origin of Species'' (or, more completely, ''On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life'')The book's full original title was ''On the Origin of Species by M ...

'', and was sharpening his "beak and claws" to disembowel "the curs who will bark and yelp". Charles Kingsley

Charles Kingsley (12 June 1819 – 23 January 1875) was a broad church priest of the Church of England, a university professor, social reformer, historian, novelist and poet. He is particularly associated with Christian socialism, the workin ...

was sent a review copy, and told Darwin that he had "long since, from watching the crossing of domesticated animals and plants, learnt to disbelieve the dogma of the permanence of species." Darwin was delighted that this "celebrated author and divine" had "gradually learnt to see that it is just as noble a conception of the Deity to believe that He created a few original forms capable of self-development into other and needful forms, as to believe that He required a fresh act of creation to supply the voids caused by the action of His laws."

While reviews were by custom anonymous, their authors were usually known. Huxley's reviews of ''On the Origin of Species'' irritated Owen, whose own anonymous review in April praised himself and his own ''axiom of the continuous operation of the ordained becoming of living things'', took offence at the way the creationist position had been depicted, and complained that his own pre-eminence had been ignored. Owen bitterly attacked Huxley, Hooker and Darwin, but also signalled acceptance of a kind of evolution as a teleological

Teleology (from , and )Partridge, Eric. 1977''Origins: A Short Etymological Dictionary of Modern English'' London: Routledge, p. 4187. or finalityDubray, Charles. 2020 912Teleology. In ''The Catholic Encyclopedia'' 14. New York: Robert Applet ...

plan in a continuous "ordained becoming", with new species appearing by natural birth.

The dispute between Huxley and Owen over human uniqueness began in public at the 1860 Oxford evolution debate

The 1860 Oxford evolution debate took place at the Oxford University Museum in Oxford, England, on 7 July 1860, seven months after the publication of Charles Darwin's ''On the Origin of Species''. Several prominent British scientists and philoso ...

, during a meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science

The British Science Association (BSA) is a Charitable organization, charity and learned society founded in 1831 to aid in the promotion and development of science. Until 2009 it was known as the British Association for the Advancement of Scienc ...

in Oxford on Thursday 28 June 1860. After Charles Daubeny

Charles Giles Bridle Daubeny (11 February 179512 December 1867) was an English chemist, botanist and geologist.

Education

Daubeny was born at Stratton near Cirencester in Gloucestershire, the son of the Rev. James Daubeny. He went to Winchest ...

's paper "On the Final Causes of the Sexuality of Plants with Particular Reference to Mr. Darwin's Work", the chairman asked Huxley for comments, but he declined as he thought the public venue inappropriate. Owen then spoke of facts which would enable the public to "come to some conclusions ... of the truth of Mr. Darwin's theory", reportedly arguing that "the brain of the gorilla was more different from that of man than from that of the lowest primate particularly because only man had a posterior lobe, a posterior horn, and a hippocampus minor." In response, Huxley flatly but politely "denied altogether that the difference between the brain of the gorilla and man was so great" in a "direct and unqualified contradiction" of Owen, citing previous studies as well as promising to provide detailed support for his position.

Anguish over the death of his son of scarlet fever

Scarlet fever, also known as scarlatina, is an infectious disease caused by ''Streptococcus pyogenes'', a Group A streptococcus (GAS). It most commonly affects children between five and 15 years of age. The signs and symptoms include a sore ...

in September 1860 pushed Huxley to the brink, from which Kingsley rescued him by a series of letters. Huxley put his fury over the death into composing a paper which violently assaulted Owen's ideas and professional reputation. It was published in January 1861 in the first issue of Huxley's relaunched '' Natural History Review'' magazine, and presented citations, quotations and letters from leading anatomists to attack Owen's three claims, aiming to prove him "guilty of wilful and deliberate falsehood" by citing Owen himself, and (with less clear cut justification) the anatomists whose illustrations Owen had used in the 1857 paper. While readily agreeing that the human brain differed from that of apes in size, proportions and complexity of convolutions, Huxley played the significance of these features down, and argued that to a lesser extent these also differed between the "highest" and "lowest" human races. Darwin congratulated Huxley on this "smasher" against the "canting humbug" Owen. From February to May Huxley delivered a very popular series of sixpenny lectures for working men at the School of Mines

A school is the educational institution (and, in the case of in-person learning, the building) designed to provide learning environments for the teaching of students, usually under the direction of teachers. Most countries have systems of ...

where he taught, on "The Relation of Man to the Rest of the Animal Kingdom". He told his wife that "My working men stick by me wonderfully, the house being fuller than ever last night. By next Friday evening they will all be convinced that they are monkeys."

Gorillas became the topic of the day with the return of the explorer

Gorillas became the topic of the day with the return of the explorer Paul Du Chaillu

Paul Belloni Du Chaillu (July 31, 1831 (disputed)April 29, 1903) was a French-American traveler, zoologist, and anthropologist. He became famous in the 1860s as the first modern European outsider to confirm the existence of gorillas, and later t ...

. Owen arranged for him to speak and display his collections on stage at a spectacular Royal Geographical Society

The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers), often shortened to RGS, is a learned society and professional body for geography based in the United Kingdom. Founded in 1830 for the advancement of geographical scien ...

meeting on 25 February, and followed this by giving a lecture at the Royal Institution

The Royal Institution of Great Britain (often the Royal Institution, Ri or RI) is an organisation for scientific education and research, based in the City of Westminster. It was founded in 1799 by the leading British scientists of the age, inc ...

on 19 March on the brains of ''The Gorilla and the Negro'', asserting that the dispute was one of interpretation rather than fact, and hedging his previous claim by stating that humans alone had a hippocampus minor "as defined in human anatomy". This lecture was published in the '' Athenæum'' on 23 March with unlabelled and inaccurate illustrations, and Huxley's response in the next issue a week later, ''Man and the Apes'', ridiculed Owen's use of these illustrations and failure to mention the findings of anatomists that the three structures were present in animals. In the following week's issue Owen's letter blamed "the Artist" for the illustrations, but claimed that the argument was correct and referred the reader to his 1858 paper. In the ''Athenæum'' of 13 April Huxley responded to this repetition of the claim by writing that "Life is too short to occupy oneself with the slaying of the slain more than once."

Each Saturday, Darwin read the latest ripostes in the ''Athenæum''. Owen tried to smear Huxley by portraying him as an "advocate of man's origins from a transmuted ape", and one of his contributions was titled "Ape-Origin of Man as Tested by the Brain". This backfired, as Huxley had already delighted Darwin by speculating on "pithecoid man" (ape-like man), and was glad of the invitation to publicly turn the anatomy of brain structure into a question of human ancestry. Darwin egged him on from Down, writing "Oh Lord what a thorn you must be in the poor dear man's side". Huxley told Darwin's friend Joseph Dalton Hooker

Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker (30 June 1817 – 10 December 1911) was a British botanist and explorer in the 19th century. He was a founder of geographical botany and Charles Darwin's closest friend. For 20 years he served as director of the Ro ...

, "Owen occupied an entirely untenable position ... The fact is he made a prodigious blunder in commencing the attack, and now his only chance is to be silent and let people forget the exposure. I do not believe that in the whole history of science there is a case of any man of reputation getting himself into such a contemptible position. He will be the laughing-stock of all the continental anatomists."

Public interest and satire

This very public slanging match attracted wide attention, and humorists were quick to take up the opportunity for satire. '' Punch'' featured the issue several times that year, notably on 18 May 1861 when a cartoon under the heading ''Monkeyana'' showed a standinggorilla

Gorillas are primarily herbivorous, terrestrial great apes that inhabit the tropical forests of equatorial Africa. The genus ''Gorilla'' is divided into two species: the eastern gorilla and the western gorilla, and either four or five su ...

with a sign parodying Josiah Wedgwood's anti-slavery slogan "Am I Not A Man And A Brother?". This was accompanied by a satirical poem by "Gorilla" at the zoo asking to be told if he was "A man in ape's shape, An anthropoid ape, Or monkey deprived of his tail?", and noting:

It then recounts Huxley's ripostes, and:

The poem was actually by the eminent palaeontologist Sir Philip Egerton who, as a trustee of the

It then recounts Huxley's ripostes, and:

The poem was actually by the eminent palaeontologist Sir Philip Egerton who, as a trustee of the Royal College of Surgeons

The Royal College of Surgeons is an ancient college (a form of corporation) established in England to regulate the activity of surgeons. Derivative organisations survive in many present and former members of the Commonwealth. These organisations ...

and the British Museum

The British Museum is a Museum, public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is the largest in the world. It documents the story of human cu ...

, acted as Owen's patron. When a delighted Huxley found out who the author of the piece was, he thought it "speaks volumes for Owen's perfect success in damning himself."

In the second issue of Huxley's ''Natural History Review'', an article by George Rolleston

George Rolleston (30 July 1829 – 16 June 1881) was an English physician and zoologist. He was the first Linacre Professor of Anatomy and Physiology to be appointed at the University of Oxford, a post he held from 1860 until his death in 1881. ...

on the orangutan

Orangutans are great apes native to the rainforests of Indonesia and Malaysia. They are now found only in parts of Borneo and Sumatra, but during the Pleistocene they ranged throughout Southeast Asia and South China. Classified in the genus ...

brain showed the features that Owen claimed apes lacked, and when Owen responded in a letter to the ''Annals and Magazine of Natural History

The ''Journal of Natural History'' is a scientific journal published by Taylor & Francis focusing on entomology and zoology. The journal was established in 1841 under the name ''Annals and Magazine of Natural History'' (''Ann. Mag. Nat. Hist.'') ...

'' that the issue was a matter of definition rather than fact, Huxley made a public dissection of a spider monkey

Spider monkeys are New World monkeys belonging to the genus ''Ateles'', part of the subfamily Atelinae, family Atelidae. Like other atelines, they are found in tropical forests of Central and South America, from southern Mexico to Brazil. The g ...

that had died at the zoo, to support his case. In the following issue John Marshall

John Marshall (September 24, 1755July 6, 1835) was an American statesman, jurist, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the fourth chief justice of the United States from 1801 until his death in 1835. He remai ...

provided detailed measurements making the same point about the chimpanzee

The chimpanzee (; ''Pan troglodytes''), also simply known as the chimp, is a species of Hominidae, great ape native to the forests and savannahs of tropical Africa. It has four confirmed subspecies and a fifth proposed one. When its close rel ...

, as well as explaining how a chimpanzee's brain could be distorted by not being properly preserved and removed from the skull, so that it would look like the one in Owen's illustration.

The Great Hippocampus Question

The debate continued in 1862. A detailed paper byWilliam Henry Flower

Sir William Henry Flower (30 November 18311 July 1899) was an English surgeon, museum curator and comparative anatomist, who became a leading authority on mammals and especially on the primate brain. He supported Thomas Henry Huxley in an ...

in the prestigious journal, the ''Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society

''Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society'' is a scientific journal published by the Royal Society. In its earliest days, it was a private venture of the Royal Society's secretary. It was established in 1665, making it the second journ ...

'', reviewed the earlier literature and presented his own studies based on having dissected sixteen species of primates, including prosimian

Prosimians are a group of primates that includes all living and extinct Strepsirrhini, strepsirrhines (lemurs, Lorisoidea, lorisoids, and Adapiformes, adapiforms), as well as the Haplorhini, haplorhine tarsiers and their extinct relatives, the Om ...

s, monkeys and an orangutan. Having stated at the outset that he had no opinion on transmutation or the origin of humans, he refuted Owen's three claims, and went further, stating that in relation to the mass of the brain, the hippocampus minor was proportionately largest in the marmoset

The marmosets (), also known as zaris or sagoin, are twenty-two New World monkey species of the genera '' Callithrix'', '' Cebuella'', '' Callibella'', and ''Mico''. All four genera are part of the biological family Callitrichidae. The term ...

, and proportionately smallest in mankind. The paper used terms recently coined by Huxley, and Flower was one of his close colleagues. Huxley presented more evidence against Owen in his '' Natural History Review''. The Dutch anatomists Jacobus Schroeder van der Kolk and Willem Vrolik found that Owen had repeatedly used their 1849 illustration of a chimpanzee's brain to support his arguments, and to prevent the public from being misled they dissected the brain of an orangutan that had died in the Amsterdam zoo, reporting at a meeting of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences

The Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences (, KNAW) is an organization dedicated to the advancement of science and literature in the Netherlands. The academy is housed in the Trippenhuis in Amsterdam.

In addition to various advisory a ...

that the three features Owen claimed were unique to humans were present in this ape. They admitted that their earlier illustration was incorrect due to the way they had removed the brain for inspection, and suggested that Owen had become "lost" and "fell into a trap" in debating against Darwin. Huxley reprinted the report, in French, in his ''Review''. His confrontations with Owen went on.

At the 1862

At the 1862 British Association

The British Science Association (BSA) is a charity and learned society founded in 1831 to aid in the promotion and development of science. Until 2009 it was known as the British Association for the Advancement of Science (BA). The current Chief ...

meeting in Cambridge that year, Owen presented two papers opposing Darwin: one claimed that the adaptations of the Aye-aye

The aye-aye (''Daubentonia madagascariensis'') is a long-fingered lemur, a Strepsirrhini, strepsirrhine primate native to Madagascar with rodent-like teeth that perpetually grow and a special thin middle finger that they can use to catch grubs ...

disproved evolution, and the second paper reiterated Owen's claims about human brains being unique, as well as discussing the question of whether apes have toes or thumbs. Huxley said Owen appeared to be "lying & shuffling", and Huxley's allies presented successive attacks on Owen. This was the first British Association annual meeting attended by Charles Kingsley

Charles Kingsley (12 June 1819 – 23 January 1875) was a broad church priest of the Church of England, a university professor, social reformer, historian, novelist and poet. He is particularly associated with Christian socialism, the workin ...

, and during the meeting he produced a privately printed satirical skit on the argument, "a little squib for circulation among his friends" written in the style of the then popular stage character Lord Dundreary, a good natured but brainless aristocrat known for huge bushy sideburns and for mangling proverbs or sayings in "Dundrearyisms". The skit was titled ''Speech of Lord Dundreary in Section D, on Friday Last, On the Great Hippocampus Question''.

The ''British Medical Journal

''The BMJ'' is a fortnightly peer-reviewed medical journal, published by BMJ Publishing Group Ltd, which in turn is wholly-owned by the British Medical Association (BMA). ''The BMJ'' has editorial freedom from the BMA. It is one of the world ...

'' asked, "Is it not high time that the annual passage of barbed words between Professor Owen and Professor Huxley, on the cerebral distinction between men and monkeys, should cease? ... Continued on its present footing, it becomes a hindrance and an injury to science, a joke for the populace, and a scandal to the scientific world." The London ''Quarterly Review

The ''Quarterly Review'' was a literary and political periodical founded in March 1809 by London publishing house John Murray. It ceased publication in 1967. It was referred to as ''The London Quarterly Review'', as reprinted by Leonard Scott, f ...

'' took up the joke, describing the confrontation of Owen with Huxley and his supporters Rolleston and Flower dramatically: "Animation increased, 'decorous reticence' was at an end, and all parties enjoyed the scene except the disputants. Surely apes were never before so honoured, as to be the theme of the warmest discussion in one of the two principal university towns in England. Strange sight was this, that three or four most accomplished anatomists were contending against each other like so many gorillas, and either reducing man to a monkey, or elevating the monkey to the man!" In October the '' Medical Times and Gazette'' reported Owen's presentation with full detail of the responses by Huxley, Rolleston and Flower, as well as Owen's rebuttal. The dispute continued in the next two issues of the magazine.

The great hippopotamus test

At about the same time as he was attending the CambridgeBritish Association

The British Science Association (BSA) is a charity and learned society founded in 1831 to aid in the promotion and development of science. Until 2009 it was known as the British Association for the Advancement of Science (BA). The current Chief ...

meeting in 1862, instalments of Charles Kingsley's story for children '' The Water-Babies, A Fairy Tale for a Land Baby'' were being published in '' Macmillan's Magazine'' as a serial. Kingsley incorporated material modified from his skit about Dundreary's speech ''On the Great Hippocampus Question'', as well as other references to the protagonists, the British Association, and notable scientists of the day. When the protagonist Tom is turned into a water-baby by the fairies, the question is raised that if there were water-babies, surely someone would have caught one and "put it into spirits, or into the ''Illustrated News'', or perhaps cut it into two halves, poor dear little thing, and sent one to Professor Owen, and one to Professor Huxley, to see what they would each say about it." As for the suggestion that a water-baby is contrary to nature;

Keeping up an even-handed treatment, Kingsley introduced as a character in the story Professor Ptthmllnsprts (Put-them-all-in-spirits) as an amalgam of Owen and Huxley, satirising each in turn. Like the very possessive Owen, the Professor was "very good to all the world as long as it was good to him. Only one fault he had, which cock-robins have likewise, as you may see if you look out of the nursery window—that, when any one else found a curious worm, he would hop round them, and peck them, and set up his tail, and bristle up his feathers, just as a cock-robin would; and declare that he found the worm first; and that it was his worm; and, if not, that then it was not a worm at all." Like Huxley, "the professor had not the least notion of allowing that things were true, merely because people thought them beautiful. ... The professor, indeed, went further, and held that no man was forced to believe anything to be true, but what he could see, hear, taste, or handle." A paragraph on "the great hippopotamus test" opens with the Professor, like Huxley, declaring "that apes had hippopotamus majors in their brains just as men have", but then like Owen presenting the argument that "If you have a hippopotamus major in your brain, you are no ape".

Then, presented with the awkward question, "But why are there not water-babies?", the Professor in Huxley's characteristic voice answered quite sharply: "Because there ain’t."

''The Water-Babies'' was published in book form in 1863, and in the same year an even more satirical short play was published anonymously by George Pycroft. In ''A Report of a Sad Case Recently Tried before the Lord Mayor, Owen versus Huxley... the Great Bone Case'', the vulgarity of the behaviour of Owen and Huxley is parodied as them being taken to court for brawling

in the streets and disturbing the peace. In court, they shout terms such as "posterior cornu" and "hippocampus minor". In giving evidence, Huxley states "Well, as I was saying, Owen and me is in the same trade; and we both cuts up monkeys, and I finds something in the brains of them. Hallo! says I, here's a hippocampus. No, there ain't says Owen. Look here says I. I can't see it he says and he sets to werriting and haggling about it, and goes and tells everybody, as what I finds ain't there, and what he finds is".

Man's Place in Nature

Huxley expanded his lectures for working men into a book titled '' Evidence as to Man's Place in Nature'', published in 1863. His intention was expressed in a letter to

Huxley expanded his lectures for working men into a book titled '' Evidence as to Man's Place in Nature'', published in 1863. His intention was expressed in a letter to Charles Lyell

Sir Charles Lyell, 1st Baronet, (14 November 1797 – 22 February 1875) was a Scottish geologist who demonstrated the power of known natural causes in explaining the earth's history. He is best known today for his association with Charles ...

which referred to the ''Monkeyana'' poem of 1861: "I do not think you will find room to complain of any want of distinctness in my definition of Owen's position touching the Hippocampus question. I mean to give the whole history of the business in a note, so that the paraphrase of Sir Ph. Egerton's line 'To which Huxley replies that Owen he lies', shall be unmistakable." Darwin exclaimed, "Hurrah the monkey book has come". A central part of the book provides a step by step explanation suitable for newcomers to anatomy of how the brains of apes and humans are fundamentally similar, with particular reference to both having a posterior lobe, a posterior horn, and a hippocampus minor. The chapter concludes that this close similarity between apes and mankind proves that the original definition by Linnaeus

Carl Linnaeus (23 May 1707 – 10 January 1778), also known after ennoblement in 1761 as Carl von Linné,#Blunt, Blunt (2004), p. 171. was a Swedish biologist and physician who formalised binomial nomenclature, the modern system of naming o ...

of the biological Order of Primate

Primates is an order (biology), order of mammals, which is further divided into the Strepsirrhini, strepsirrhines, which include lemurs, galagos, and Lorisidae, lorisids; and the Haplorhini, haplorhines, which include Tarsiiformes, tarsiers a ...

s was correct to include both, and mentions that an explanation of humans originating from apes is provided by Darwin's theory. The book also includes six pages of small print giving "a succinct History of the Controversy respecting the Cerebral Structure of Man and the Apes" describing how Owen had "suppressed" and denied what Huxley had now shown to be the truth regarding the hippocampus minor, posterior horn, and posterior lobe, describing this as reflecting on Owen's "personal veracity". Reviewers regarded the book as a polemic against Owen, and a majority of them sided with Huxley.

Sir Charles Lyell's authoritative ''Geological Evidences of the Antiquity of Man

''Geological Evidences of the Antiquity of Man'' is a book written by British geologist, Charles Lyell in 1863. The first three editions appeared in February, April, and November 1863, respectively. A much-revised fourth edition appeared in 1 ...

'' was also published in 1863, and included a detailed review of the hippocampus question which gave solid and unambiguous support to Huxley's arguments. In an attempt to refute Lyell's judgement, Owen again defended his classification scheme, introducing a new claim that the hippocampus minor was virtually absent in an "idiot". Then in 1866 Owen's book ''On the Anatomy of Vertebrates'' presented accurate brain illustrations. In a long footnote, Owen cited himself and the earlier literature to admit at last that in apes "all the homologous parts of the human cerebral organ exist". However, he still believed that this did not invalidate his classification of man in a separate subclass. He now claimed that the structures concerned – the posterior lobe, the posterior horn, and the hippocampus minor – were in apes only "under modified form and low grades of development". He accused Huxley and his allies of making "puerile", "ridiculous" and "disgraceful" attacks on his scheme of classification.

The publicity surrounding the affair tarnished Owen's reputation. While Owen had a laudable aim of finding an objective way of defining the uniqueness of humanity and distinguishing their brain anatomy in a qualitative way, not just a quantitative way, his obstinacy in refusing to admit his errors in trying to find that difference led to his fall from the pinnacle of British science. Huxley gained influence, and his X Club

The X Club was a dining club of nine men who supported the theories of natural selection and academic liberalism in late 19th-century England. Thomas Henry Huxley was the initiator; he called the first meeting for 3 November 1864. The club m ...

of like minded scientists used the journal ''Nature

Nature is an inherent character or constitution, particularly of the Ecosphere (planetary), ecosphere or the universe as a whole. In this general sense nature refers to the Scientific law, laws, elements and phenomenon, phenomena of the physic ...

'' to promote evolution and naturalism, shaping much of late Victorian science. Even many of his supporters, including Charles Lyell

Sir Charles Lyell, 1st Baronet, (14 November 1797 – 22 February 1875) was a Scottish geologist who demonstrated the power of known natural causes in explaining the earth's history. He is best known today for his association with Charles ...

and Alfred Russel Wallace

Alfred Russel Wallace (8 January 1823 – 7 November 1913) was an English naturalist, explorer, geographer, anthropologist, biologist and illustrator. He independently conceived the theory of evolution through natural selection; his 1858 pap ...

, thought that though humans shared a common ancestor with apes, the higher mental faculties could not have evolved through a purely material process. Darwin published his own explanation in 1871 in the '' Descent of Man''.

Modern relevance

In a talk about biologicalsystematics

Systematics is the study of the diversification of living forms, both past and present, and the relationships among living things through time. Relationships are visualized as evolutionary trees (synonyms: phylogenetic trees, phylogenies). Phy ...

(classification) and cladistics

Cladistics ( ; from Ancient Greek 'branch') is an approach to Taxonomy (biology), biological classification in which organisms are categorized in groups ("clades") based on hypotheses of most recent common ancestry. The evidence for hypothesiz ...

given at the American Museum of Natural History

The American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) is a natural history museum on the Upper West Side of Manhattan in New York City. Located in Theodore Roosevelt Park, across the street from Central Park, the museum complex comprises 21 interconn ...

in 1981, the paleontologist

Paleontology, also spelled as palaeontology or palæontology, is the scientific study of the life of the past, mainly but not exclusively through the study of fossils. Paleontologists use fossils as a means to classify organisms, measure geolo ...

Colin Patterson discussed an argument put in a paper by Ernst Mayr

Ernst Walter Mayr ( ; ; 5 July 1904 – 3 February 2005) was a German-American evolutionary biologist. He was also a renowned Taxonomy (biology), taxonomist, tropical explorer, ornithologist, Philosophy of biology, philosopher of biology, and ...

that humans could be distinguished from apes by the presence of Broca's area

Broca's area, or the Broca area (, also , ), is a region in the frontal lobe of the dominant Cerebral hemisphere, hemisphere, usually the left, of the Human brain, brain with functions linked to speech production.

Language processing in the brai ...

in the brain. Patterson commented that this reminded him of "The Great Hippocampus Question" as recorded in fiction by Kingsley, and as in fact being a controversy between Huxley and Owen that "eventually as usual, Huxley won."

Notes

References

* * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

{{Cite journal , last1 = Owen , first1 = C. , last2 = Howard , first2 = A. , last3 = Binder , first3 = D. , title = Hippocampus minor, calcar avis, and the Huxley-Owen debate , journal = Neurosurgery , volume = 65 , issue = 6 , pages = 1098–1104; discussion 1104–5 , year = 2009 , pmid = 19934969 , doi = 10.1227/01.NEU.0000359535.84445.0B , s2cid = 19663125 (subscription required) History of evolutionary biology Evolutionary biology literature Parodies Biology controversies 19th-century controversies Scientific debates