Great Disruption on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Disruption of 1843, also known as the Great Disruption, was a schism in 1843 in which 450

The Disruption of 1843, also known as the Great Disruption, was a schism in 1843 in which 450

In 1834, the

In 1834, the

In a second case, the Court of Session summoned the Presbytery of

In a second case, the Court of Session summoned the Presbytery of

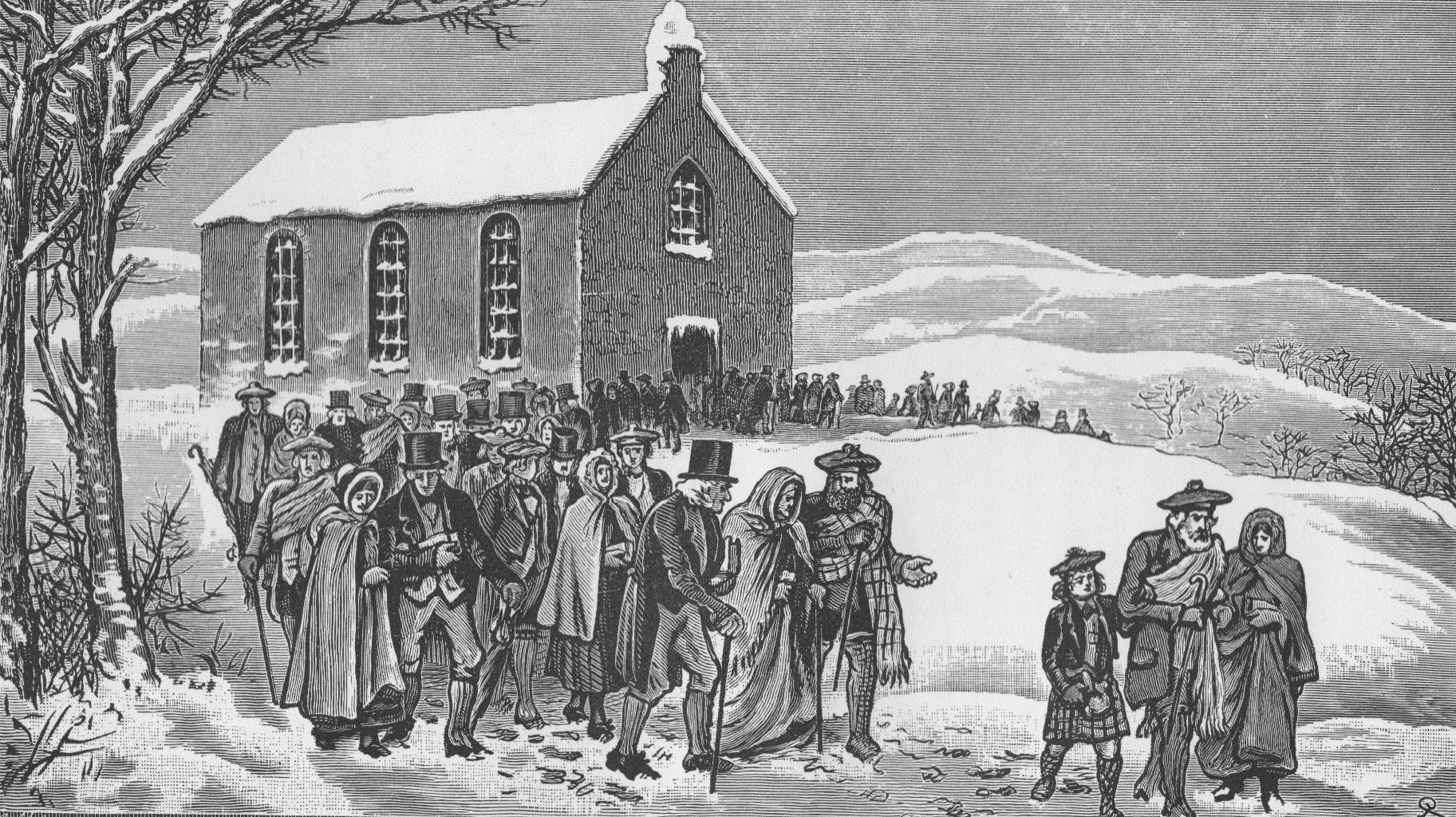

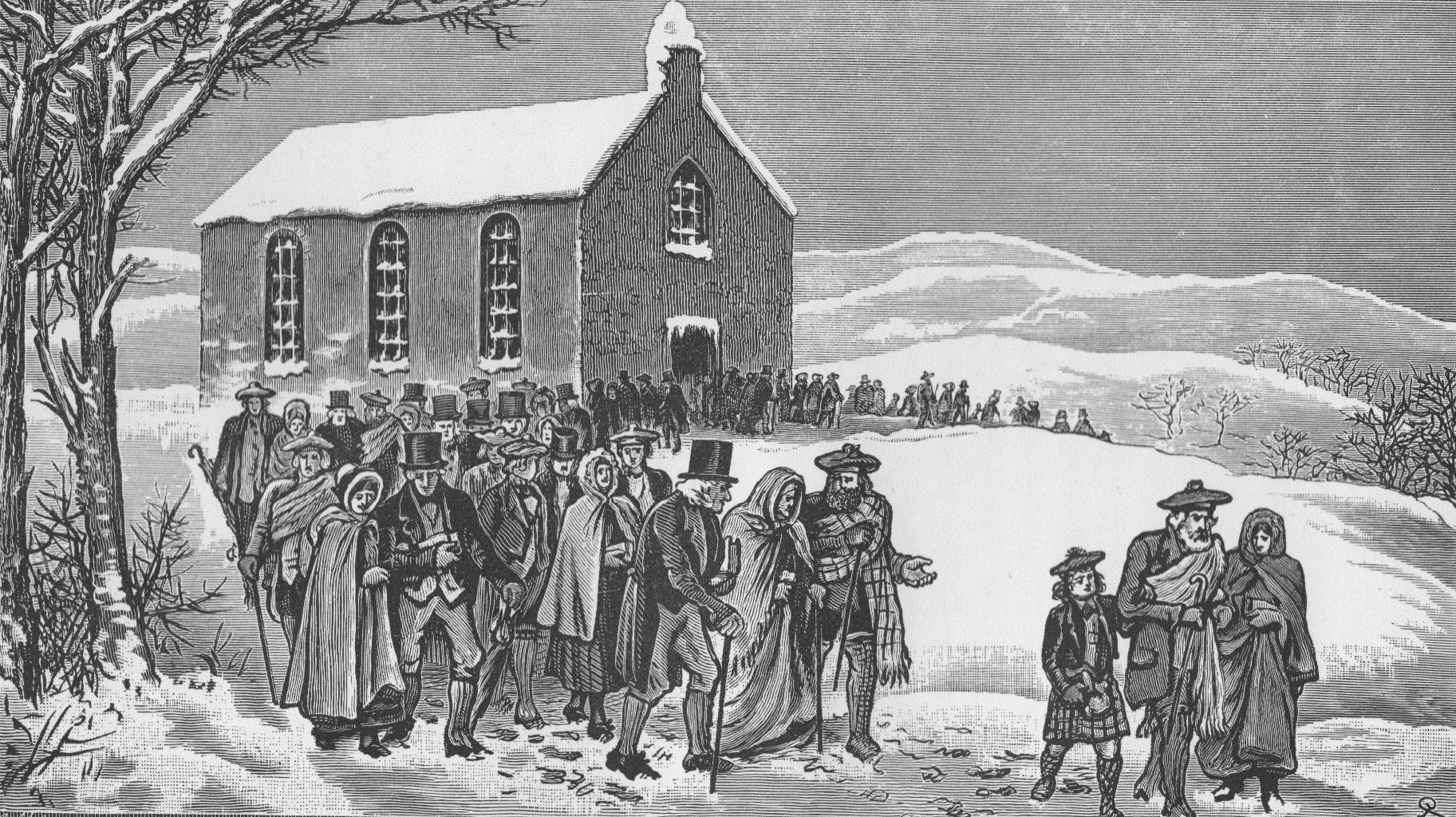

File:Leaving The Manse.jpg, alt=A minister and his family leaving their Church of Scotland manse during the Disruption (engraving J. M. Corner based on Quitting The Manse (oil painting G. Harvey) – featuring Tullibody Old Kirk, A minister and his family leaving their Church of Scotland manse during the Disruption (engraving J. M. Corner) based on Quitting The Manse (oil painting G. Harvey) – featuring

The Disruption of 1843, also known as the Great Disruption, was a schism in 1843 in which 450

The Disruption of 1843, also known as the Great Disruption, was a schism in 1843 in which 450 evangelical

Evangelicalism (), also called evangelical Christianity or evangelical Protestantism, is a worldwide, interdenominational movement within Protestantism, Protestant Christianity that emphasizes evangelism, or the preaching and spreading of th ...

ministers broke away from the Church of Scotland

The Church of Scotland (CoS; ; ) is a Presbyterian denomination of Christianity that holds the status of the national church in Scotland. It is one of the country's largest, having 245,000 members in 2024 and 259,200 members in 2023. While mem ...

to form the Free Church of Scotland.

The main conflict was over whether the Church of Scotland or the British Government had the power to control clerical positions and benefits. The Disruption came at the end of a bitter conflict within the Church of Scotland, and had major effects in the church and upon Scottish civic life.

The patronage issue

"The Church of Scotland was recognised by Acts of the Parliament as thenational church

A national church is a Christian church associated with a specific ethnic group or nation state. The idea was notably discussed during the 19th century, during the emergence of modern nationalism.

Samuel Taylor Coleridge, in a draft discussing ...

of the Scottish people". Particularly under John Knox

John Knox ( – 24 November 1572) was a Scottish minister, Reformed theologian, and writer who was a leader of the country's Reformation. He was the founder of the Church of Scotland.

Born in Giffordgate, a street in Haddington, East Lot ...

and later Andrew Melville

Andrew Melville (1 August 1545 – 1622) was a Scottish scholar, theologian, poet and religious reformer. His fame encouraged scholars from the European continent to study at Glasgow and St. Andrews.

He was born at Baldovie, on 1 August 154 ...

, the Church of Scotland had always claimed an inherent right to exercise independent spiritual jurisdiction over its own affairs. To some extent, this right was recognised by the Claim of Right

The Claim of Right (c. 28) () is an act passed by the Convention of the Estates, a sister body to the Parliament of Scotland (or Three Estates), in April 1689. It is one of the key documents of United Kingdom constitutional law and Scottish ...

of 1689, which ended royal and parliamentary

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

interference in the order and worship of the church. It was ratified by the Act of Union in 1707.

On the other hand, the right of patronage, in which the patron of a parish had the right to install a minister of his choice, became a point of contention. Many church members believed that this right infringed on the spiritual independence of the church. Others felt that this right was a property of the state. As early as 1712 the right of patronage had been restored in Scotland, amid remonstrances from the church. For many years afterwards, the church's General Assembly

A general assembly or general meeting is a meeting of all the members of an organization or shareholders of a company.

Specific examples of general assembly include:

Churches

* General Assembly (presbyterian church), the highest court of presby ...

tried to reform this practice. However the dominant Moderate Party

The Moderate Party ( , , M), commonly referred to as the Moderates ( ), is a Liberal conservatism, liberal-conservative*

*

*

*

* List of political parties in Sweden, political party in Sweden. The party generally supports tax cuts, the free ma ...

in the church blocked reform out of fear of conflict with the British Government

His Majesty's Government, abbreviated to HM Government or otherwise UK Government, is the central government, central executive authority of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

.

The "Ten Years' Conflict"

Veto Act

In 1834, the

In 1834, the evangelical

Evangelicalism (), also called evangelical Christianity or evangelical Protestantism, is a worldwide, interdenominational movement within Protestantism, Protestant Christianity that emphasizes evangelism, or the preaching and spreading of th ...

party attained a majority in the General Assembly for the first time in 100 years. One of their actions was to pass the Veto Act, which gave parishioners the right to reject a minister nominated by their patron. The Veto Act was to prevent the intrusion of ministers on unwilling parishioners, and to restore the importance of the congregational "call". However, it served to polarise positions in the church, and set it on a collision course with the government.

The first test of the Veto Act came with the ''Auchterarder'' case of 1834. The parish of Auchterarder

Auchterarder (; , meaning Upper Highland) is a town north of the Ochil Hills in Perth and Kinross, Scotland, and home to the Gleneagles Hotel. The High Street of Auchterarder gave the town its popular name of "The Lang Toun" or Long Town.

The ...

unanimously rejected the patron's nominee – and the Presbytery refused to proceed with his ordination

Ordination is the process by which individuals are Consecration in Christianity, consecrated, that is, set apart and elevated from the laity class to the clergy, who are thus then authorized (usually by the religious denomination, denominationa ...

and induction. The nominee, Robert Young, appealed to the Court of Session

The Court of Session is the highest national court of Scotland in relation to Civil law (common law), civil cases. The court was established in 1532 to take on the judicial functions of the royal council. Its jurisdiction overlapped with othe ...

. In 1838, by an 8–5 majority, the court held that in passing the Veto Act, the church had acted ''ultra vires

('beyond the powers') is a Latin phrase used in law to describe an act that requires legal authority but is done without it. Its opposite, an act done under proper authority, is ('within the powers'). Acts that are may equivalently be termed ...

'', and had infringed the statutory rights of patrons. It also ruled Church of Scotland was a creation of the state and derived its legitimacy from act of Parliament.

The'' Auchterarder'' ruling contradicted the Scottish church's Confession of Faith

A creed, also known as a confession of faith, a symbol, or a statement of faith, is a statement of the shared beliefs of a community (often a religious community) which summarizes its core tenets.

Many Christian denominations use three creeds: ...

. As Burleigh puts it: "The notion of the Church as an independent community governed by its own officers and capable of entering into a compact with the state was repudiated" (p. 342). An appeal to the House of Lords

The House of Lords is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Like the lower house, the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminster in London, England. One of the oldest ext ...

was rejected.

Further conflicts

In a second case, the Court of Session summoned the Presbytery of

In a second case, the Court of Session summoned the Presbytery of Dunkeld

Dunkeld (, , from , "fort of the Caledonians") is a town in Perth and Kinross, Scotland. The location of a historic cathedral, it lies on the north bank of the River Tay, opposite Birnam. Dunkeld lies close to the geological Highland Boundar ...

for proceeding with an ordination despite a court interdict. In 1839, the General Assembly suspended seven ministers from Strathbogie for proceeding with an induction in Marnoch in defiance of its orders. In 1841, the seven Strathbogie ministers were deposed for acknowledging the superiority of the secular court in spiritual matters.

The evangelical party later presented to parliament a ''Claim, Declaration and Protest Anent the Encroachments of the Court of Session''. The claim recognised the jurisdiction of the civil courts

A lawsuit is a proceeding by one or more parties (the plaintiff or claimant) against one or more parties (the defendant) in a Civil law (common law), civil court of law. The archaic term "suit in law" is found in only a small number of laws s ...

over the endowments that the government gave to the Scottish church. This "The Claim of Right" was drawn up by Alexander Murray Dunlop

Alexander Colquhoun-Stirling-Murray-Dunlop (27 December 1798 – 1 September 1870) was a Scottish church advocate and Liberal Party politician. He was the Member of Parliament (MP) for Greenock from 1852 to 1868. He was a very influential ...

. However, the claim resolved that the church give up these endowments rather than see the 'Crown Rights of the Redeemer' (i.e. the spiritual independence of the church) compromised. This claim was rejected by parliament in January 1843, leading to the Disruption in May.

The Disruption

On 18 May 1843, 121 ministers and 73 elders led byDavid Welsh

David Welsh FRSE (11 December 1793 – 24 April 1845) was a Scottish Presbyterian minister and academic. He was Moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland in 1842. In the Disruption of 1843 he was one of the leading figu ...

met at the Church of St Andrew St. Andrew's Church, Church of St Andrew, or variants thereof, may refer to:

Albania

* St. Andrew's Church, Himarë

Australia Australian Capital Territory

* St Andrew's Presbyterian Church, Canberra, founded by John Walker (Presbyterian minis ...

in George Street, Edinburgh

Edinburgh is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. The city is located in southeast Scotland and is bounded to the north by the Firth of Forth and to the south by the Pentland Hills. Edinburgh ...

. After Welsh read a Protest, the group left St. Andrews and walked down the hill to the Tanfield Hall at Canonmills

Canonmills is a district of Edinburgh, the capital of Scotland. It lies to the south east of the Royal Botanic Garden at Inverleith, east of Stockbridge and west of Bellevue, in a low hollow north of Edinburgh's New Town. The area was formerl ...

. There they held the first meeting of the Free Church of Scotland, the Disruption Assembly. Thomas Chalmers

Thomas Chalmers (17 March 178031 May 1847), was a Scottish Presbyterian minister, professor of theology, political economist, and a leader of both the Church of Scotland and of the Free Church of Scotland (1843—1900), Free Church of Scotl ...

was appointed the first Moderator. On 23 May, a second meeting was held for the signing of the Act of Separation by the ministers. Eventually, 474 of about 1,200 ministers left the Church of Scotland for the Free Church.

In leaving the established church, however, they did not reject the principle of establishment. As Chalmers declared: "Though we quit the Establishment, we go out on the Establishment principle; we quit a vitiated Establishment but would rejoice in returning to a pure one. We are advocates for a national recognition of religion – and we are not voluntaries."

Perhaps a third of the evangelicals, the "middle party", remained within the established church – wishing to preserve its unity. However, for those who left, the issue was clear. It was not the democratising of the church (although concern with power for ordinary people was a movement sweeping Europe at the time), but whether the Church was sovereign within its own domain. The body of the church reflecting Jesus Christ, not the monarch nor Parliament, was to be its head. The Disruption was basically a spiritual phenomenon – and for its proponents it stood in a direct line with the Reformation

The Reformation, also known as the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation, was a time of major Theology, theological movement in Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the p ...

and the National Covenant

The National Covenant () was an agreement signed by many people of Scotland during 1638, opposing the proposed Laudian reforms of the Church of Scotland (also known as '' the Kirk'') by King Charles I. The king's efforts to impose changes on th ...

s.

Splitting the church had major implications. Those who left forfeited livings, manses and pulpits, and had, without the aid of the establishment, to found and finance a national church from scratch. This was done with remarkable energy, zeal and sacrifice. Another implication was that the church they left was more tolerant of a wider range of doctrinal views.

There was also the issue of needing to train its clergy, resulting in the establishment of New College, with Chalmers appointed as its first principal. It was founded as an institution to educate future ministers and the Scottish leadership, who would in turn guide the moral and religious lives of the Scottish people. New College opened its doors to 168 students in November 1843, including about 100 students who had begun their theological studies before the Disruption.

Most of the principles on which the protestors went out were conceded by Parliament by 1929, clearing the way for the re-union of that year, but the Church of Scotland never fully regained its position after the division.

Photographic portraiture

The painterDavid Octavius Hill

David Octavius Hill (20 May 1802 – 17 May 1870) was a Scottish painter, photographer and arts activist. He formed Hill & Adamson studio with the engineer and photographer Robert Adamson between 1843 and 1847 to pioneer many aspects of p ...

was present at the Disruption Assembly and decided to record the scene. He received encouragement from another spectator, the physicist Sir David Brewster

Sir David Brewster KH PRSE FRS FSA Scot FSSA MICE (11 December 178110 February 1868) was a British scientist, inventor, author, and academic administrator. In science he is principally remembered for his experimental work in physical optic ...

who suggested using the new invention, photography, to get likenesses of all the ministers present, and introduced Hill to the photographer Robert Adamson. Subsequently, a series of photographs were taken of those who had been present, and the 5-foot x 11-foot 4 inches (1.53 m x 3.45 m) painting was eventually completed in 1866. The partnership that developed between Hill and Adamson pioneered the art of photography in Scotland. The painting predominantly features the ministers involved in the Disruption but Hill also included many other men – and some women – who were involved in the establishment of the Free Church. The painting depicts 457 people of the 1500 or so who were present at the assembly on 23 May 1843.

Gallery

Tullibody

Tullibody () is a village set in the Central Lowlands of Scotland. It lies north of the River Forth near to the foot of the Ochil Hills within the Forth Valley. The village is southwest of Alva, Clackmannanshire, Alva, northwest of Alloa and ...

Old Kirk

File:New College on the Mound, Edinburgh.jpg, alt=New College, on the Mound, designed by William Henry Playfair and built 1845–1850. 0New College, on the Mound, designed by William Henry Playfair

William Henry Playfair Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, FRSE (15 July 1790 – 19 March 1857) was a prominent Scottish architect in the 19th century who designed the Eastern, or Third, New Town, Edinburgh, New Town and many of Edinb ...

and built 1845–1850.

File:Dumbarton Presbytery 1845.jpg, Hill & Adamson

Hill & Adamson was the first photography studio in Scotland, set up by painter David Octavius Hill and engineer Robert Adamson in 1843. During their brief partnership that ended with Adamson's untimely death, Hill & Adamson produced "the first ...

took photographic portraits of all the clergymen who had been at the assembly.

In literature and the arts

The social tensions underlying the Disruption are the subject ofWilliam Alexander William or Bill Alexander may refer to:

Literature

*William Alexander (poet) (1808–1875), American poet and author

*William Alexander (journalist and author) (1826–1894), Scottish journalist and author

* William Alexander (author) (born 1976), ...

's novel, ''Johnny Gibb of Gushetneuk'' (1870). David Octavius Hill's use of photography to record the ministers who participated in the schism of 1843 features in Ali Bacon's novel ''In the Blink of an Eye'' (2018). The novel ''Clear'' (2024) by Carys Davies is set against the backdrop of the Great Disruption and the Highland Clearances

The Highland Clearances ( , the "eviction of the Gaels") were the evictions of a significant number of tenants in the Scottish Highlands and Islands, mostly in two phases from 1750 to 1860.

The first phase resulted from Scottish Agricultural R ...

.Davies, Carys (2024), ''Clear'', Granta Books,

See also

*History of Scotland

The recorded history of Scotland begins with the Scotland during the Roman Empire, arrival of the Roman Empire in the 1st century, when the Roman province, province of Roman Britain, Britannia reached as far north as the Antonine Wall. No ...

*Religion in the United Kingdom

Christianity is the largest religion in the United Kingdom. Results of the United Kingdom Census 2021, 2021 Census for England and Wales showed that Christianity is the largest religion (though it makes up less than half of the population at ...

References

Citations

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* Cameron, N. ''et al.'' (eds.) ''Dictionary of Scottish Church History and Theology'', Edinburgh:T&T Clark

T&T Clark is a British publishing firm which was founded in Edinburgh, Scotland, in 1821 and which now exists as an imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing.

History

The firm was founded in 1821 by Thomas Clark, then aged 22 and who had a Free Church ...

, 1993.

* Burleigh, J. H. S. ''A Church History of Scotland'' Edinburgh: Hope Trust 1988.

{{Nineteenth-century Scotland

History of the Church of Scotland

Presbyterianism in Scotland

Schisms in Christianity

1843 in Scotland

19th-century Reformed Christianity

1843 in Christianity

Church of Scotland