Gray's Manual on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Asa Gray (November 18, 1810 – January 30, 1888) is considered the most important American

While he was in Paris at the Jardin des Plantes, Gray saw an unnamed dried specimen, collected by

While he was in Paris at the Jardin des Plantes, Gray saw an unnamed dried specimen, collected by

The ''Elements of Botany'' (1836), an introductory textbook, was the first of Gray's many works. In this book Gray espoused the idea that botany was useful not only to medicine, but also to farmers. Gray and Torrey published the ''Flora of North America'' together in 1838. By the mid-1850s the demands of teaching, research, gardening, collecting, and corresponding had become so great, and he had become so influential, that Gray wrote two high school-level texts in the late 1850s: ''First Lessons in Botany and Vegetable Physiology'' (1857) and ''How Plants Grow: A Simple Introduction to Structural Botany'' (1858). The publishers pressured Gray to make these two books non-technical enough so that high school students and non-scientists could understand them. As with most scientists in American academic institutions, Gray found it difficult to concentrate purely on research.

Gray met physician and botanist

The ''Elements of Botany'' (1836), an introductory textbook, was the first of Gray's many works. In this book Gray espoused the idea that botany was useful not only to medicine, but also to farmers. Gray and Torrey published the ''Flora of North America'' together in 1838. By the mid-1850s the demands of teaching, research, gardening, collecting, and corresponding had become so great, and he had become so influential, that Gray wrote two high school-level texts in the late 1850s: ''First Lessons in Botany and Vegetable Physiology'' (1857) and ''How Plants Grow: A Simple Introduction to Structural Botany'' (1858). The publishers pressured Gray to make these two books non-technical enough so that high school students and non-scientists could understand them. As with most scientists in American academic institutions, Gray found it difficult to concentrate purely on research.

Gray met physician and botanist

Prior to 1840, besides what he had discovered during his trip to Europe, Gray's knowledge of the flora of the

Prior to 1840, besides what he had discovered during his trip to Europe, Gray's knowledge of the flora of the  Gray traveled to the American West on two separate occasions, the first in 1872 by train, and then again with

Gray traveled to the American West on two separate occasions, the first in 1872 by train, and then again with

:Just fate, prolong his life, well spent,

:Whose indefatigable hours

:Have been as gayly innocent,

:And fragrant as his flowers.

Darwin Correspondence Project

National Academy of Sciences Biographical Memoir

A doctoral thesis on the correspondence between Asa Gray and Charles Darwin

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Gray, Asa 1810 births 1888 deaths American botanical writers American taxonomists Botanists active in North America American male non-fiction writers American people of Scotch-Irish descent American Protestants Burials at Mount Auburn Cemetery Corresponding members of the Saint Petersburg Academy of Sciences Fellows of the American Association for the Advancement of Science Foreign members of the Royal Society Hall of Fame for Great Americans inductees Harvard University faculty University of Michigan faculty Members of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences Museum founders People from Sauquoit, New York Theistic evolutionists 19th-century American botanists 19th-century American male writers Scientists from New York (state) 19th-century American philanthropists Writers about religion and science Science activists Members of the American Philosophical Society

botanist

Botany, also called plant science, is the branch of natural science and biology studying plants, especially Plant anatomy, their anatomy, Plant taxonomy, taxonomy, and Plant ecology, ecology. A botanist or plant scientist is a scientist who s ...

of the 19th century. His ''Darwiniana

''Darwiniana: Essays and Reviews Pertaining to Darwinism'' is a collection of essays by botanist Asa Gray, first published in 1876. These widely read essays both defended the theory of evolution from the standpoint of botany and sought reconcilia ...

'' (1876) was considered an important explanation of how religion and science were not necessarily mutually exclusive. Gray was adamant that a genetic connection must exist between all members of a species. He was also strongly opposed to the ideas of hybridization within one generation and special creation

In Christian theology, special creation is a term with varying meanings dependent on context.

In creationism, the term refers to a belief that the universe and all life in it originated in its present form by fiat or divine decree.

Catholicism u ...

in the sense of its not allowing for evolution. He was a strong supporter of Darwin, although Gray's theistic evolution

Theistic evolution (also known as theistic evolutionism or God-guided evolution), alternatively called evolutionary creationism, is a view that God acts and creates through laws of nature. Here, God is taken as the primary cause while natural cau ...

was guided by a Creator.

As a professor of botany at Harvard University

Harvard University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Founded in 1636 and named for its first benefactor, the History of the Puritans in North America, Puritan clergyma ...

for several decades, Gray regularly visited, and corresponded with, many of the leading natural scientists of the era, including Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English Natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci ...

, who held great regard for him. Gray made several trips to Europe to collaborate with leading European scientists of the era, as well as trips to the southern and western United States. He also built an extensive network of specimen collectors.

A prolific writer, he was instrumental in unifying the taxonomic

280px, Generalized scheme of taxonomy

Taxonomy is a practice and science concerned with classification or categorization. Typically, there are two parts to it: the development of an underlying scheme of classes (a taxonomy) and the allocation ...

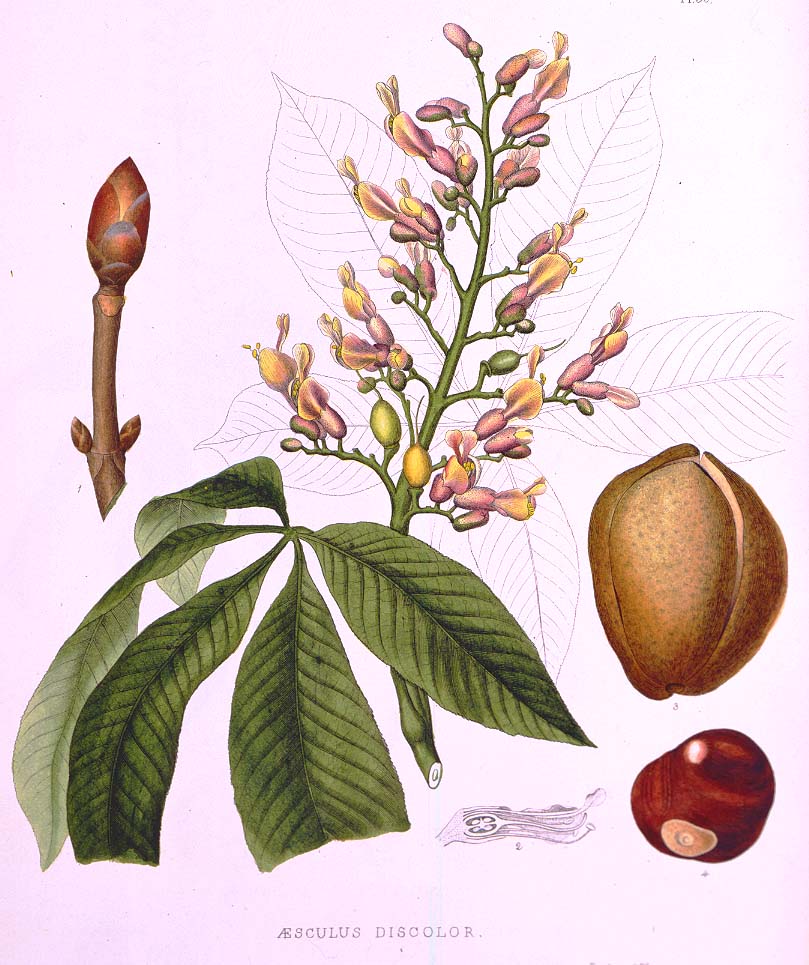

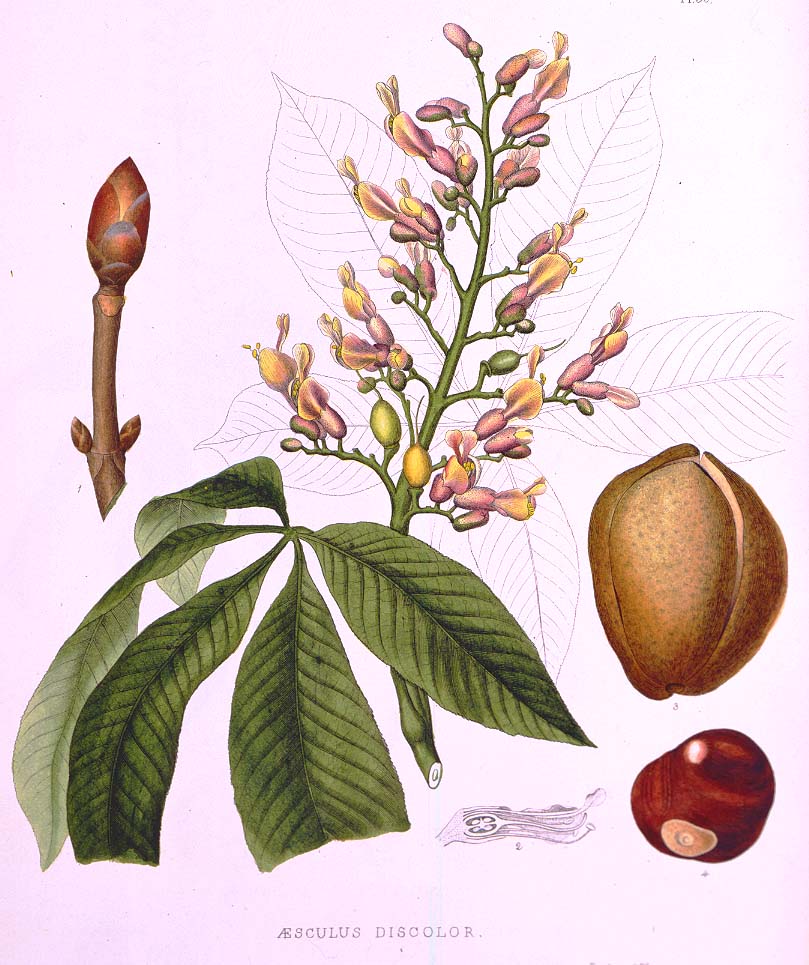

knowledge of the plants of North America. Of Gray's many works on botany, the most popular was his '' Manual of the Botany of the Northern United States, from New England to Wisconsin and South to Ohio and Pennsylvania Inclusive'', known today simply as ''Gray's Manual''. Gray was the sole author of the first five editions of the book and co-author of the sixth, with botanical illustrations by Isaac Sprague

Isaac Sprague (September 5, 1811 – 1895) was a self-taught landscape, botanical, and ornithological painter. He was America's best known botanical illustrator of his day.

Sprague was born in Hingham, Massachusetts and apprenticed with his unc ...

. Further editions have been published, and it remains a standard in the field. Gray also worked extensively on a phenomenon that is now called the "Asa Gray disjunction", namely, the surprising morphological similarities between many eastern Asian and eastern North American plants. Several structures, geographic features, and plants have been named after Gray.

In 1848, Gray was elected as a member of the American Philosophical Society

The American Philosophical Society (APS) is an American scholarly organization and learned society founded in 1743 in Philadelphia that promotes knowledge in the humanities and natural sciences through research, professional meetings, publicat ...

.

Early life and education

Gray was born inSauquoit, New York

Sauquoit is a Hamlet (New York), hamlet in the Paris, New York, Town of Paris, Oneida County, New York, United States. It is located on New York State Route 8, New York Route 8, approximately six miles south of Utica, New York, Utica and east of ...

, on November 18, 1810, to Moses Gray (b.February 26, 1786), then a tanner, and Roxanna Howard Gray (b. March 15, 1789). Born in the back of his father's tannery, Gray was the eldest of their eight children. Gray's paternal great-grandfather had arrived in Boston

Boston is the capital and most populous city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Massachusetts in the United States. The city serves as the cultural and Financial centre, financial center of New England, a region of the Northeas ...

from Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ; ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, part of the United Kingdom in the north-east of the island of Ireland. It has been #Descriptions, variously described as a country, province or region. Northern Ireland shares Repub ...

in 1718; Gray's Scotch-Irish Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a historically Reformed Protestant tradition named for its form of church government by representative assemblies of elders, known as "presbyters". Though other Reformed churches are structurally similar, the word ''Pr ...

ancestors had moved to New York from Massachusetts

Massachusetts ( ; ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Maine to its east, Connecticut and Rhode ...

and Vermont

Vermont () is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders Massachusetts to the south, New Hampshire to the east, New York (state), New York to the west, and the Provinces and territories of Ca ...

after Shays' Rebellion

Shays's Rebellion was an armed uprising in Western Massachusetts and Worcester, Massachusetts, Worcester in response to a debt crisis among the citizenry and in opposition to the state government's increased efforts to collect taxes on both in ...

. His parents married on July 30, 1809. Tanneries needed a lot of wood to burn, and the lumber supply in the area had been shrinking, so Gray's father used his profits to buy farms in the area, and in about 1823 sold the tannery and became a farmer.

Gray was an avid reader even in his youth. He completed Clinton Grammar School from about 1823 to 1825, in those years reading many books from the nearby library at Hamilton College

Hamilton College is a Private college, private Liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts college in Clinton, Oneida County, New York, Clinton, New York. It was established as the Hamilton-Oneida Academy in 1793 and received its c ...

. In 1825 he enrolled at Fairfield Academy

Fairfield Academy was an academy that existed for nearly one hundred years in the Town of Fairfield, New York, Fairfield, Herkimer County, New York.

Founding

It was organized as an academy for men in 1802, when the community was an active local ...

, switching to its Fairfield Medical College, also known as the Medical College of the Western District of Fairfield, in autumn 1826. It was during this time that Gray began to mount botanical specimens. On a trip to New York City, he attempted to meet with John Torrey

John Torrey (August 15, 1796 – March 10, 1873) was an American botany, botanist, chemist, and physician. Throughout much of his career, he was a teacher of chemistry, often at multiple universities, while he also pursued botanical work, focus ...

to get assistance in identifying specimens, but Torrey was not home, so Gray left the specimens at Torrey's house. Torrey was so impressed with Gray's specimens that he began a correspondence with him. Gray graduated and became an M.D.

A Doctor of Medicine (abbreviated MD, from the Latin ) is a medical degree, the meaning of which varies between different jurisdictions. In the United States, and some other countries, the ''MD'' denotes a professional degree of physician. This ge ...

in February 1831, even though he was not yet 21 years of age, which was a requirement at the time. Although Gray did open a medical office in Bridgewater, New York

Bridgewater is a town in Oneida County, New York, United States. The population was 1,522 at the 2010 census.

The Town of Bridgewater is on the southern border of the county. The town has a former village called Bridgewater near the southern ...

, where he had served an apprenticeship with Doctor John Foote Trowbridge while he was in medical school, he never truly practiced medicine, as he enjoyed botany more. It was around this time that he began making explorations in New York and New Jersey

New Jersey is a U.S. state, state located in both the Mid-Atlantic States, Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern United States, Northeastern regions of the United States. Located at the geographic hub of the urban area, heavily urbanized Northeas ...

. By autumn 1831 he had all but given up his medical practice to devote more time to botany.

In 1832 he was hired to teach chemistry, mineralogy

Mineralogy is a subject of geology specializing in the scientific study of the chemistry, crystal structure, and physical (including optical mineralogy, optical) properties of minerals and mineralized artifact (archaeology), artifacts. Specific s ...

, and botany at Bartlett's High School in Utica, New York

Utica () is the county seat of Oneida County, New York, United States. The tenth-most populous city in New York, its population was 65,283 in the 2020 census. It is located on the Mohawk River in the Mohawk Valley at the foot of the Adiro ...

, and at Fairfield Medical School, replacing instructors who had died in mid-term. Agreeing to teach for one year, with a break from August to December 1832, Gray had to cancel his plans for an expedition to Mexico, which at the time included what is now the southwestern United States. Gray first met Torrey in person in September 1832, and they went on an expedition to New Jersey. After completing his teaching assignment in Utica on August 1, 1833, Gray became an assistant to Torrey at the College of Physicians and Surgeons in New York City. By this time, Gray was corresponding and trading specimens with botanists not just in America, but also in Asia, Europe, and the Pacific Islands. Gray held a temporary teaching position in 1834 at Hamilton College

Hamilton College is a Private college, private Liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts college in Clinton, Oneida County, New York, Clinton, New York. It was established as the Hamilton-Oneida Academy in 1793 and received its c ...

. Due to funding shortages, in 1835 Gray was obliged to leave his job as Torrey's assistant, and in February or March 1836 became curator and librarian at the Lyceum of Natural History in New York, now called the New York Academy of Sciences

The New York Academy of Sciences (NYAS), originally founded as the Lyceum of Natural History in January 1817, is a nonprofit professional society based in New York City, with more than 20,000 members from 100 countries. It is the fourth-oldes ...

. He had an apartment in their new building in Manhattan. Torrey's attempt to get Gray a job at Princeton University

Princeton University is a private university, private Ivy League research university in Princeton, New Jersey, United States. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth, New Jersey, Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the List of Colonial ...

was unsuccessful, as were other attempts to find him a position in science. Despite Gray no longer being his assistant, Torrey and Gray became lifelong friends and colleagues. Torrey's wife, Eliza Torrey, had a profound impact upon Gray in his manners, tastes, habits, and religious life.

Career

In October 1836 Gray was selected to be one of the botanists on theUnited States Exploring Expedition

The United States Exploring Expedition of 1838–1842 was an exploring and surveying expedition of the Pacific Ocean and surrounding lands conducted by the United States. The original appointed commanding officer was Commodore Thomas ap Catesby ...

(1838–1842), also known as the "Wilkes Expedition", which was supposed to last three years. Gray began getting paid well for his work preparing and planning for this expedition, even to the point of loading supplies onto a ship in New York harbor. However, the expedition was fraught with politics, bickering, turmoil, inefficiency, and delays. Referring to the Secretary of the Navy

The Secretary of the Navy (SECNAV) is a statutory officer () and the head (chief executive officer) of the Department of the Navy, a military department within the United States Department of Defense. On March 25, 2025, John Phelan was confirm ...

, Mahlon Dickerson

Mahlon Dickerson (April 17, 1770 – October 5, 1853) was a justice of the Supreme Court of New Jersey, the seventh governor of New Jersey, United States Senator from New Jersey, the 10th United States Secretary of the Navy and a United States ...

, Gray wrote of "abominable management & stupidity". Despite this, Gray resigned from the Lyceum in April 1837 to devote his time to the preparations. By 1838 the expedition was in utter turmoil. The new state of Michigan

Michigan ( ) is a peninsular U.S. state, state in the Great Lakes region, Great Lakes region of the Upper Midwest, Upper Midwestern United States. It shares water and land boundaries with Minnesota to the northwest, Wisconsin to the west, ...

was starting its university, and Gray applied for a professorship in early 1838. He resigned from the Wilkes Expedition on July 10, 1838. In 1848 Gray was hired to work on the botanical specimens, and published the first volume of the report on botany in 1854, but Wilkes was unable to secure the funding for the second volume.

On July 17, 1838, Gray became the very first permanent paid professor at the newly founded University of Michigan

The University of Michigan (U-M, U of M, or Michigan) is a public university, public research university in Ann Arbor, Michigan, United States. Founded in 1817, it is the oldest institution of higher education in the state. The University of Mi ...

, although in the event he never taught classes. His position was also the first one devoted solely to botany at any educational institution in America. Appointed Professor of Botany and Zoology, Gray was dispatched to Europe by the regents of the university for the purpose of purchasing a suitable array of books to form the university's library, and equipment such as microscopes to aid research. Botanist Charles F. Jenkins states that the main purpose of this trip was to examine American flora in Europe's herbariums. Gray departed on the packet ship

Packet boats were medium-sized boats designed mainly for domestic mail and freight transport in European countries and in North American rivers and canals. Eventually including basic passenger accommodation, they were used extensively during t ...

''Philadelphia'' on November 9, 1838, sailing through The Narrows

The Narrows is the tidal strait separating the boroughs of Staten Island and Brooklyn in New York City. It connects the Upper New York Bay and Lower New York Bay (of larger New York Bay) and forms the principal channel by which the Hudson Ri ...

out of New York Harbor nine days before his 28th birthday. Gray and the regents were both involved in stocking the university library. In 1839 the regents purchased a complete copy of Audubon's ''The Birds of America

''The Birds of America'' is a book by naturalist and painter John James Audubon, containing illustrations of a wide variety of birds of the United States. It was first published as a series in sections between 1827 and 1838, in Edinburgh and L ...

'' for the then-extraordinary sum of $970. Gray's first stop was in Glasgow

Glasgow is the Cities of Scotland, most populous city in Scotland, located on the banks of the River Clyde in Strathclyde, west central Scotland. It is the List of cities in the United Kingdom, third-most-populous city in the United Kingdom ...

, visiting William Hooker, who aided and financially supported many botanists, including Gray. On January 16, 1839, he arrived in London and stayed until March 14. He then spent time in Paris, where he collaborated with Joseph Decaisne

Joseph Decaisne (7 March 1807 – 8 January 1882) was a French botanist and agronomist. He became an ''aide-naturaliste'' to Adrien-Henri de Jussieu (1797–1853), who served as the chair of rural botany. It was during this time that he began to ...

at the Jardin des Plantes

The Jardin des Plantes (, ), also known as the Jardin des Plantes de Paris () when distinguished from other ''jardins des plantes'' in other cities, is the main botanical garden in France. Jardin des Plantes is the official name in the present da ...

. In mid-April 1839 he left Paris for Italy by way of southern France, then visiting Genoa

Genoa ( ; ; ) is a city in and the capital of the Italian region of Liguria, and the sixth-largest city in Italy. As of 2025, 563,947 people live within the city's administrative limits. While its metropolitan city has 818,651 inhabitan ...

, Rome, Florence

Florence ( ; ) is the capital city of the Italy, Italian region of Tuscany. It is also the most populated city in Tuscany, with 362,353 inhabitants, and 989,460 in Metropolitan City of Florence, its metropolitan province as of 2025.

Florence ...

, Venice, Bologna

Bologna ( , , ; ; ) is the capital and largest city of the Emilia-Romagna region in northern Italy. It is the List of cities in Italy, seventh most populous city in Italy, with about 400,000 inhabitants and 150 different nationalities. Its M ...

, Padua

Padua ( ) is a city and ''comune'' (municipality) in Veneto, northern Italy, and the capital of the province of Padua. The city lies on the banks of the river Bacchiglione, west of Venice and southeast of Vicenza, and has a population of 20 ...

, and Trieste

Trieste ( , ; ) is a city and seaport in northeastern Italy. It is the capital and largest city of the Regions of Italy#Autonomous regions with special statute, autonomous region of Friuli-Venezia Giulia, as well as of the Province of Trieste, ...

. After Italy, Gray went to Vienna

Vienna ( ; ; ) is the capital city, capital, List of largest cities in Austria, most populous city, and one of Federal states of Austria, nine federal states of Austria. It is Austria's primate city, with just over two million inhabitants. ...

, Austria. While in Vienna, he spent twelve days studying specimen collections and gardens with Stephan Endlicher

Stephan Friedrich Ladislaus Endlicher, also known as Endlicher István László (24 June 1804 – 28 March 1849), was an Austrian Empire, Austrian botanist, numismatist and Sinologist. He was a director of the Botanical Garden of Vienna.

Biog ...

, who also introduced him to other local botanists. In 1840 Endlicher became director of the Botanical Garden of the University of Vienna

The Botanical Garden of the University of Vienna is a botanical garden in Vienna, Austria. It covers 8 hectares and is immediately adjacent to the Belvedere gardens. It is a part of the University of Vienna.

History

The gardens date back to 17 ...

. Departing Austria, Gray went to Munich

Munich is the capital and most populous city of Bavaria, Germany. As of 30 November 2024, its population was 1,604,384, making it the third-largest city in Germany after Berlin and Hamburg. Munich is the largest city in Germany that is no ...

, Zürich

Zurich (; ) is the list of cities in Switzerland, largest city in Switzerland and the capital of the canton of Zurich. It is in north-central Switzerland, at the northwestern tip of Lake Zurich. , the municipality had 448,664 inhabitants. The ...

, and Geneva

Geneva ( , ; ) ; ; . is the List of cities in Switzerland, second-most populous city in Switzerland and the most populous in French-speaking Romandy. Situated in the southwest of the country, where the Rhône exits Lake Geneva, it is the ca ...

, where he met the prominent botanist Augustin Pyramus de Candolle

Augustin Pyramus (or Pyrame) de Candolle (, , ; 4 February 17789 September 1841) was a Swiss people, Swiss botany, botanist. René Louiche Desfontaines launched de Candolle's botanical career by recommending him at a herbarium. Within a couple ...

, who died in 1841. Gray continued extensive collaboration with deCandolle's son Alphonse Pyramus de Candolle

Alphonse Louis Pierre Pyramus (or Pyrame) de Candolle (27 October 18064 April 1893) was a French-Swiss botanist, the son of the Swiss botanist Augustin Pyramus de Candolle.

Biography

De Candolle, son of Augustin Pyramus de Candolle, first devot ...

. Gray returned to Germany, going to Freiburg

Freiburg im Breisgau or simply Freiburg is the List of cities in Baden-Württemberg by population, fourth-largest city of the German state of Baden-Württemberg after Stuttgart, Mannheim and Karlsruhe. Its built-up area has a population of abou ...

, Tübingen

Tübingen (; ) is a traditional college town, university city in central Baden-Württemberg, Germany. It is situated south of the state capital, Stuttgart, and developed on both sides of the Neckar and Ammer (Neckar), Ammer rivers. about one in ...

, Dresden

Dresden (; ; Upper Saxon German, Upper Saxon: ''Dräsdn''; , ) is the capital city of the States of Germany, German state of Saxony and its second most populous city after Leipzig. It is the List of cities in Germany by population, 12th most p ...

, Halle, and then Berlin

Berlin ( ; ) is the Capital of Germany, capital and largest city of Germany, by both area and List of cities in Germany by population, population. With 3.7 million inhabitants, it has the List of cities in the European Union by population withi ...

, where he stayed for a month. While in Berlin, he spent most of his time in Schöneberg

Schöneberg () is a locality of Berlin, Germany. Until Berlin's 2001 administrative reform it was a separate borough including the locality of Friedenau. Together with the former borough of Tempelhof it is now part of the new borough of Te ...

, where the region's Botanical Gardens were then located. Gray then returned to London by way of Hamburg

Hamburg (, ; ), officially the Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg,. is the List of cities in Germany by population, second-largest city in Germany after Berlin and List of cities in the European Union by population within city limits, 7th-lar ...

. Gray admitted he just managed some of the book purchasing and that he delegated the actual buying of books to George Palmer Putnam

George Palmer Putnam (February 7, 1814 – December 20, 1872) was an American publisher and author. He founded the firm G. P. Putnam's Sons and ''Putnam's Magazine''. He was an advocate of international copyright reform, secretary for many year ...

, who was then living in London. Gray spent a year in Europe, leaving for America from Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port city status in the United Kingdom, city and unitary authority in Hampshire, England. Most of Portsmouth is located on Portsea Island, off the south coast of England in the Solent, making Portsmouth the only city in En ...

, England, aboard the sailing ship ''Toronto'' on October 1, 1839, and arriving back in New York on November 4. Gray, together with his agents, eventually purchased about 3,700 books for the University of Michigan library. The regents at the University of Michigan were so impressed by Gray's work in Europe, including his spending about $1,500 of his own money on specimen collections, that they granted him another year's salary that covered him until the summer of 1841. However, finances at the university were so bad that they asked him to resign in April 1840.

While he was in Paris at the Jardin des Plantes, Gray saw an unnamed dried specimen, collected by

While he was in Paris at the Jardin des Plantes, Gray saw an unnamed dried specimen, collected by André Michaux

André Michaux (' → ahn- mee-; sometimes Anglicisation, anglicised as Andrew Michaud; 8 March 174611 October 1802) was a French botanist and explorer. He is most noted for his study of North American flora. In addition Michaux collected specime ...

, and named it ''Shortia galacifolia

''Shortia galacifolia'', the Oconee bells or acony bell, is a rare North American plant in the family Diapensiaceae found in the southern Appalachian Mountains, concentrated in the tri-state border region of Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia, North C ...

''. He spent considerable time and effort over the next 38 years looking for a specimen in the wild. The first such expedition was in late June to late July 1841 to an area near Jefferson, Ashe County, North Carolina. His further expeditions searching for this species were also unsuccessful, including one in 1876. In May 1877 a North Carolina herb collector found a specimen but did not know what it was. Eighteen months later the collector sent it to Joseph Whipple Congdon

Joseph Whipple Congdon (April 13, 1834 – April 5, 1910) was a lawyer by trade who contributed significantly to early botanical exploration in California, particularly in the Yosemite region, where he resided in Mariposa from 1882 until 1905. C ...

, who contacted Gray, telling Gray that he felt he had found ''Shortia''. Gray was ecstatic to confirm this when he saw the specimen in October 1878. In spring 1879 Gray led an expedition, in which the collector helped, to the spot where ''S.galacifolia'' had been found. Gray never saw the species in the wild in bloom, but made a final trip to this region in 1884.

Harvard professor

Both Gray and Torrey were elected to theAmerican Academy of Arts and Sciences

The American Academy of Arts and Sciences (The Academy) is one of the oldest learned societies in the United States. It was founded in 1780 during the American Revolution by John Adams, John Hancock, James Bowdoin, Andrew Oliver, and other ...

in December 1841. Gray never returned to teach a course at Michigan. In 1833 Dr.Joshua Fisher, a resident of Beverly, Massachusetts

Beverly is a city in Essex County, Massachusetts, United States, and a suburb of Boston. The population was 42,670 at the time of the 2020 United States census. A resort, residential, and manufacturing community on the Massachusetts North Sho ...

, and a Harvard University

Harvard University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Founded in 1636 and named for its first benefactor, the History of the Puritans in North America, Puritan clergyma ...

alumnus, bequeathed $20,000 to Harvard to endow a chair in natural history. The university allowed the proceeds to accumulate until it could fund a full year's salary for a professor. Because of this and a few problems in finding a suitable professor, this chair was not filled until it was formally offered to Gray on March 26, 1842. The offer was $1,000/year salary, teaching duties limited to only botany, and being superintendent of Harvard's botanic garden. While the salary was low, the teaching limitation, rare for the time, allowed him plenty of time to do research and work in the botanic garden. After an exchange of letters, Gray accepted this appointment as Fisher Professor of Natural History at Harvard. The formal appointment was made April 30, 1842. Gray arrived at Harvard on July 22, 1842, and began his duties in September. He did not have to teach in the fall of 1842, but began in spring 1843, the first classes he had taught in nine years. Early in his years at Harvard, Gray had to borrow money from his father. Soon he was able to repay his father and help his family by supplementing his income giving lectures outside of Harvard, including at the Lowell Institute

The Lowell Institute is a United States educational foundation located in Boston, Massachusetts, providing both free public lectures, and also advanced lectures. It was endowed by a bequest of $250,000 left by John Lowell Jr., who died in 1836. T ...

. Gray was considered a weak lecturer, but because of his expert knowledge, he was highly regarded by his peers. His skills were better suited to teaching advanced rather than introductory classes. He also gained renown for his textbooks and high quality illustrations. Gray moved into what became known as the Asa Gray House

The Asa Gray House, recorded in an HABS survey as the Garden House, is a historic house at 88 Garden Street, Cambridge, Massachusetts. A National Historic Landmark, it is notable architecturally as the earliest known work of the designer and ...

in the Botanic Garden in the summer of 1844. It had been built in 1810 for William Dandridge Peck

William Dandridge Peck (May 8, 1763 – October 8, 1822) was an American naturalist, the first native-born entomologist and a pioneer in the field of economic entomology. In 1806 he became the first professor of natural history at Harvard, a pos ...

and later occupied by Thomas Nuttall

Thomas Nuttall (5 January 1786 – 10 September 1859) was an English botanist and zoologist who lived and worked in America from 1808 until 1841.

Nuttall was born in the village of Long Preston, near Settle in the West Riding of Yorkshire a ...

. As the demands of teaching, collecting, selling specimens, taking care of the herbarium, and writing books increased and he himself was not a good illustrator, Gray found it necessary to hire a botanical illustratorIsaac Sprague

Isaac Sprague (September 5, 1811 – 1895) was a self-taught landscape, botanical, and ornithological painter. He was America's best known botanical illustrator of his day.

Sprague was born in Hingham, Massachusetts and apprenticed with his unc ...

, who illustrated much of Gray's works for decades to come.

By June 1848 many of the specimens from the Wilkes Expedition had been damaged or lost. Many were still not classified or published, as the mismanagement and bungling that had plagued the expedition before it ever departed continued. While on a trip to Washington, D.C., that month with his new bride, Gray was hired to study the botanical specimens for five years. This included a year in Europe, with his wife, using the facilities at the herbariums in Europe. Mr.and Mrs.Gray departed for England on June 11, 1850. They spent the summer traveling to Belgium

Belgium, officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. Situated in a coastal lowland region known as the Low Countries, it is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeas ...

, Switzerland, Germany, and the Netherlands

, Terminology of the Low Countries, informally Holland, is a country in Northwestern Europe, with Caribbean Netherlands, overseas territories in the Caribbean. It is the largest of the four constituent countries of the Kingdom of the Nether ...

. Gray then set down to work on the expedition's plant sheets at the estate of botanist George Bentham

George Bentham (22 September 1800 – 10 September 1884) was an English botanist, described by the weed botanist Duane Isely as "the premier systematic botanist of the nineteenth century". Born into a distinguished family, he initially studie ...

, whom he had met eleven years earlier, and then with William Henry Harvey

William Henry Harvey, FRS FLS (5 February 1811 – 15 May 1866) was an Irish botanist and phycologist who specialised in algae.

Biography

Harvey was born at Summerville near Limerick, Ireland, in 1811, the youngest of 11 children. His father ...

in Ireland. Gray returned to England and settled into a routine at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew

Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew is a non-departmental public body in the United Kingdom sponsored by the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs. An internationally important botanical research and education institution, it employs 1,10 ...

. The couple was back in America on September 4, 1851. In the meantime, a dispute had arisen between Wilkes and the team of Torrey and Gray about the format of the books resulting from the expedition. Gray almost hired his father-in-law to break the contract. This dispute largely centered on the use of Latin and English. Wilkes wanted a literal Latin to English translation while Torrey and Gray wanted a looser one because they felt that technical English terms were equally incomprehensible to the public. Much of the work was stymied or burned in fires.

In 1855, Torrey and Gray contributed a "Report on the Botany of the Expedition" to Volume II of the ''Reports of Explorations and Surveys to ascertain the most practicable and economical route for a railroad from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean'' (known as the Pacific Railroad Surveys

The Pacific Railroad Surveys (1853–1855) were a series of explorations of the American West designed to find and document possible routes for a transcontinental railroad across North America. The expeditions included surveyors, scientists, and a ...

). The Report included a catalogue of plants collected along with 10 black and white plates for illustration.

During the late summer of 1855, Gray made his third trip to Europe. This was an emergency trip to bring his ill brother-in-law home from Paris. Gray spent only three weeks in London and Paris, and on the way back he read the newly published ''Géographie botanique raisonnée'' by Alphonse deCandolle. This was a ground-breaking book that for the first time brought together the large mass of data being collected by the expeditions of the time. The natural sciences had become highly specialized, yet this book synthesized them to explain living organisms within their environment and why plants were distributed the way they were, all upon a geologic scale. Gray instantly saw that this brought taxonomic botany into focus.

Despite Gray constantly seeking collectors and people to help him with the Harvard herbarium, in the first fifteen years he was at Harvard, no graduate entered botany as a career. This changed in 1858 with the arrival of Daniel Cady Eaton

Daniel Cady Eaton (September 12, 1834 – June 29, 1895) was an American botanist and author. After studies at the Rensselaer Institute in Troy and Russell's military school in New Haven, he gained his bachelor's degree at Yale College, then w ...

, who had graduated from Yale University

Yale University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in New Haven, Connecticut, United States. Founded in 1701, Yale is the List of Colonial Colleges, third-oldest institution of higher education in the United Stat ...

in 1857 and came to Harvard to study with Gray. Eaton later returned to Yale to be a botany professor and oversee its herbarium, just as Gray did at Harvard. Daniel Eaton was the grandson of Amos Eaton

Amos Eaton (May 17, 1776 – May 10, 1842) was an American botany, botanist, geologist, and educator who is considered the founder of the modern scientific prospectus in education, which was a radical departure from the American liberal arts tra ...

, whose textbooks Gray had studied during his college days. Eaton influenced the teaching style of Gray, and both required practical work of their students. Gray retained the Fisher post until 1873 while living in the Asa Gray House.

In 1859 Gray was elected a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences () is one of the Swedish Royal Academies, royal academies of Sweden. Founded on 2 June 1739, it is an independent, non-governmental scientific organization that takes special responsibility for promoting nat ...

. The National Academy of Sciences

The National Academy of Sciences (NAS) is a United States nonprofit, NGO, non-governmental organization. NAS is part of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, along with the National Academy of Engineering (NAE) and the ...

was created by Congress on March 3, 1863, and he was one of the original 50 members. In 1864 Gray donated 200,000 plant specimens and 2,200 books to Harvard with the condition that the herbarium and garden be built. This effectively created the botany department at Harvard, and the Gray Herbarium

The Harvard University Herbaria and Botanical Museum are institutions located on the grounds of Harvard University at 22 Divinity Avenue, Cambridge, Massachusetts. The Botanical Museum is one of three which comprise the Harvard Museum of Natural ...

was named after him. He was president of the American Association for the Advancement of Science

The American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) is a United States–based international nonprofit with the stated mission of promoting cooperation among scientists, defending scientific freedom, encouraging scientific responsib ...

in 1872 and of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences 1863–1873. Gray was also a regent at the Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums, Education center, education and Research institute, research centers, created by the Federal government of the United States, U.S. government "for the increase a ...

in 1874–1888 and a foreign member of the Royal Society of London

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, r ...

in 1873.

The ''Elements of Botany'' (1836), an introductory textbook, was the first of Gray's many works. In this book Gray espoused the idea that botany was useful not only to medicine, but also to farmers. Gray and Torrey published the ''Flora of North America'' together in 1838. By the mid-1850s the demands of teaching, research, gardening, collecting, and corresponding had become so great, and he had become so influential, that Gray wrote two high school-level texts in the late 1850s: ''First Lessons in Botany and Vegetable Physiology'' (1857) and ''How Plants Grow: A Simple Introduction to Structural Botany'' (1858). The publishers pressured Gray to make these two books non-technical enough so that high school students and non-scientists could understand them. As with most scientists in American academic institutions, Gray found it difficult to concentrate purely on research.

Gray met physician and botanist

The ''Elements of Botany'' (1836), an introductory textbook, was the first of Gray's many works. In this book Gray espoused the idea that botany was useful not only to medicine, but also to farmers. Gray and Torrey published the ''Flora of North America'' together in 1838. By the mid-1850s the demands of teaching, research, gardening, collecting, and corresponding had become so great, and he had become so influential, that Gray wrote two high school-level texts in the late 1850s: ''First Lessons in Botany and Vegetable Physiology'' (1857) and ''How Plants Grow: A Simple Introduction to Structural Botany'' (1858). The publishers pressured Gray to make these two books non-technical enough so that high school students and non-scientists could understand them. As with most scientists in American academic institutions, Gray found it difficult to concentrate purely on research.

Gray met physician and botanist George Engelmann

George Engelmann, also known as Georg Engelmann, (2 February 1809 – 4 February 1884) was a German-American botanist. He was instrumental in describing the flora (plants), flora of the west of North America, then very poorly known to Europeans; ...

in the early 1840s, and they remained friends and colleagues until Engelmann died in 1884. Torrey was an early American supporter of the "natural system of classification", which relies upon geography and a plant's entire structure, and as his assistant, Gray was a proponent of this system, too. This contrasts with Linnaeus' artificial classification, which was designed for ease of use and focused on readily observed aspects of a plant, particularly the differences in the flowers. Amos Eaton was also a proponent of the artificial system. Gray was so impressed with Wilhelm Nikolaus Suksdorf

Wilhelm Nikolaus Suksdorf (September 15, 1850 – October 3, 1932) was an American botanist who specialized in the flora of the Pacific Northwest. He was largely self-taught and is considered one of the top three self-taught botanists of his ...

, a largely self-taught immigrant from Germany who specialized in the flora of the Pacific Northwest

The Pacific Northwest (PNW; ) is a geographic region in Western North America bounded by its coastal waters of the Pacific Ocean to the west and, loosely, by the Rocky Mountains to the east. Though no official boundary exists, the most common ...

, that he had Suksdorf come to Harvard to be his assistant and named the genus ''Suksdorfia

''Suksdorfia'' is a genus in the family Saxifragaceae. It has only two accepted species, '' Suksdorfia alchemilloides'' and '' Suksdorfia violacea'', native to central South America and northwestern North America, respectively. Asa Gray named th ...

'' after him.

Gray was a leading opponent of the Scientific Lazzaroni

The Scientific Lazzaroni is a self-mocking name adopted by Alexander Dallas Bache and his group of scientists who flourished before and up to the American Civil War. (" Lazzaroni" was slang for the homeless idlers of Naples who live by chance work ...

, a group of mostly physical scientists who wanted American academia to mimic the autocratic academic structures of European universities. A large percentage of the original 50 members of the National Academy of Sciences were Lazzaroni members. The American Academy of Arts and Sciences was opposed to the National Academy and collectively elected Gray and his friend, colleague, and fellow Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English Natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci ...

supporter William Barton Rogers

William Barton Rogers (December 7, 1804 – May 30, 1882) was an American geologist, physicist, and the founder and first president of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

An acclaimed lecturer in the physical sciences, Rogers taug ...

to the National Academy. Rogers founded the Massachusetts Institute of Technology

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) is a Private university, private research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Established in 1861, MIT has played a significant role in the development of many areas of moder ...

. This is one of the areas where Gray and his friend and colleague, Louis Agassiz

Jean Louis Rodolphe Agassiz ( ; ) FRS (For) FRSE (May 28, 1807 – December 14, 1873) was a Swiss-born American biologist and geologist who is recognized as a scholar of Earth's natural history.

Spending his early life in Switzerland, he recei ...

, were in disagreement; Agassiz was a member of the Lazzaroni group. Agassiz had come to lecture at the Lowell Institute in 1846 and got hired by Harvard in 1847. Gray befriended him the way he had been befriended during his trip to Europe.

Gray abhorred slavery

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

. In his view, science proved the unity of all man because all human races can interbreed and produce fertile offspring, i.e., all members of a species are connected genetically. He also felt Christianity taught the unity of man. He was not an abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the political movement to end slavery and liberate enslaved individuals around the world.

The first country to fully outlaw slavery was Kingdom of France, France in 1315, but it was later used ...

, feeling it was more important to preserve the Union, yet he also felt if the South

South is one of the cardinal directions or compass points. The direction is the opposite of north and is perpendicular to both west and east.

Etymology

The word ''south'' comes from Old English ''sūþ'', from earlier Proto-Germanic ''*sunþa ...

persevered in the conflict, every slave should be set free, by use of more force if necessary. However, he was not sure what should be done with the freed slaves. This was another area where Gray and Agassiz disagreed; Agassiz felt each race had different origins.

During the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

, Gray was a steadfast supporter of the North and the Republican Party. About February 1861two months before the war startedGray lost part of his left thumb, just above the base of the nail, in an accident in the garden. Despite now being 50 years old, he regretted that this accident ended his "fighting days". After hostilities began, he joined a company that guarded the Massachusetts State Arsenal in Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a List of cities in the United Kingdom, city and non-metropolitan district in the county of Cambridgeshire, England. It is the county town of Cambridgeshire and is located on the River Cam, north of London. As of the 2021 Unit ...

. He also bought war bonds, was surprised more people did not do likewise, and supported a 5%tax to support the war. Gray regretted not having children because he had "no son to send to the war". Gray considered Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

as a second George Washington

George Washington (, 1799) was a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the first president of the United States, serving from 1789 to 1797. As commander of the Continental Army, Washington led Patriot (American Revoluti ...

because of the way he managed to preserve the Union during the war. He also predicted that the fate of slavery depended upon the length and bitterness of the war, and the longer it lasted the more disastrous it would be for the South. As a corollary, he felt that if the South had given up early in the war, they would have had a chance of preserving slavery longer. Regarding his botanical endeavors, the war sundered his supply of information and specimens from the South. Even the Southern botanists who supported the North, such as Alvan Wentworth Chapman

Alvan Wentworth Chapman (September 28, 1809 – April 6, 1899) was an American physician and pioneering botanist in the study of flora of the Southeastern United States, American Southeast.Makers of American Botany, Harry Baker Humphrey, Ronald Pr ...

and Thomas Minott Peters

Thomas Minott Peters (December 4, 1810 – June 14, 1888) was an American lawyer, jurist, and botanist who studied the flora of the Southern United States.

Life and career

Born in Clarksville, the county seat of Tennessee's Montgomery County ...

, were soon forced to cease communications with Gray. It was during the war that Gray first began to think of retiring from his professorial duties so he could concentrate on completing ''Flora of North America''.

Harvard was able to secure substantial new funding for its botanical programs in the years after the war, but Gray encountered significant trouble finding a suitable replacement for his professorial duties. The American university system had failed to train replacements for its professors. Only Harvard and Yale had botany programs, and in the war and pre-war years there had been few botany students. However, after the war there was an upswing in the numbers of botany students. Gray was grooming Horace Mann Jr.

Horace Mann Jr. (February 25, 1844 – November 11, 1868) was an American botanist, son of Horace Mann. His mother was one of the famous Peabody Sisters Mary Tyler Peabody Mann. Mentored in botany by Henry David Thoreau, whom he accompanied on a ...

as his replacement, but he died of tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB), also known colloquially as the "white death", or historically as consumption, is a contagious disease usually caused by ''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can al ...

at the age of 24 in November 1868.

Growing weary of his workload, Gray and his wife departed on a trip to Britain, Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

(for three months), and Switzerland in September 1868. It was during the winter spent in Egypt that Gray first grew his white beard. They returned in autumn 1869. In early 1872 Gray tried to resign his professorship and garden duties still with no replacement for himself. He proposed only looking after the herbarium and writing books in exchange for the rent of the house in which he and his wife lived on the university grounds. Due to the way the finances of the funding sources were handled and the lack of a replacement, Gray was unable to resign at that time.

In late 1872 Charles Sprague Sargent

Charles Sprague Sargent (April 24, 1841March 22, 1927) was an American botanist. He was appointed in 1872 as the first director of Harvard University's Arnold Arboretum in Boston, Massachusetts, and held the post until his death. He published se ...

was appointed director of the Botanic Garden, the newly constructed Arnold Arboretum

The Arnold Arboretum is a botanical research institution and free public park affiliated with Harvard University and located in the Jamaica Plain and Roslindale, Massachusetts, Roslindale neighborhoods of Boston.

Established in 1872, it is the ...

, and new botany-related buildings. This freed up much of Gray's time. Also, late in 1872, Ignatius Sargent, Charles' father, and Horatio Hollis Hunnewell

Horatio Hollis Hunnewell (July 27, 1810 – May 20, 1902) was an American railroad financier, philanthropist, amateur botanist, and one of the most prominent horticulturists in America in the nineteenth century. Hunnewell was a partner in the ...

both agreed to donate $500 yearly each to support Gray so that he could devote "undivided attention" to completing ''Flora of North America''. This is what finally allowed Gray to resign his professorship and devote all his time to research and writing.

Harvard had so much trouble finding a replacement for Gray that they considered hiring a European, but they found an American and hired George Lincoln Goodale

George Lincoln Goodale (August 3, 1839 – April 12, 1923) was an American botanist and the first director of Harvard's Botanical Museum (now part of the Harvard Museum of Natural History). It was he who commissioned the making of the univers ...

in late 1872. Goodale had a medical degree from Harvard and a solid knowledge of botany. By late June 1873 Goodale had enough experience that Gray was excited to pronounce he had taught his last class. William Gilson Farlow

William Gilson Farlow (December 17, 1844 – June 3, 1919) was an American botanist, mycologist, and professor at Harvard University for more than 40 years. Farlow conducted groundbreaking research on plant pathology, taught the first plant patho ...

also had a medical degree from Harvard and had studied botany. He became Gray's assistant in 1870 after obtaining his medical degree and then studied in Europe for a few years. He returned to Harvard in 1874 and became a botany professor. Sereno Watson

Sereno Watson (December 1, 1826 – March 9, 1892) was an American botanist.

Life

Watson was born on December 1, 1826, in East Windsor Hill, Connecticut.

Graduating from Yale in 1847 in biology, he drifted through various occupations unt ...

began helping Gray with taxonomy in 1872 and became the herbarium curator. The reorganization of botany at Harvard in the early 1870s was a major accomplishment of Gray's.

"Asa Gray disjunction"

Gray worked extensively on a phenomenon that is now called the "Asa Gray disjunction", namely, the surprising morphological similarities between many eastern Asian and eastern North American plants. In fact, Gray felt the flora of eastern North America is more similar to the flora of Japan than it is to the flora of western North America, but more recent studies have shown this is not so. While Gray was not the first botanist to notice this (it was first noticed in the early 18thcentury), beginning in the early 1840s he brought scientific focus to the issue. He was the first scientist in the world to possess the requisite knowledge set to do so as he had intimate knowledge of the northeast and southeast United States as well as eastern Asiadue to several contacts he had there. The phenomenon involves about 65genera and is not limited to plants, but also includes fungi,arachnid

Arachnids are arthropods in the Class (biology), class Arachnida () of the subphylum Chelicerata. Arachnida includes, among others, spiders, scorpions, ticks, mites, pseudoscorpions, opiliones, harvestmen, Solifugae, camel spiders, Amblypygi, wh ...

s, millipede

Millipedes (originating from the Latin , "thousand", and , "foot") are a group of arthropods that are characterised by having two pairs of jointed legs on most body segments; they are known scientifically as the class Diplopoda, the name derive ...

s, insects, and freshwater fish

Freshwater fish are fish species that spend some or all of their lives in bodies of fresh water such as rivers, lakes, ponds and inland wetlands, where the salinity is less than 1.05%. These environments differ from marine habitats in many wa ...

es. It was believed that each pair of species might be international sister species

In phylogenetics, a sister group or sister taxon, also called an adelphotaxon, comprises the closest relative(s) of another given unit in an evolutionary tree.

Definition

The expression is most easily illustrated by a cladogram:

Taxon A and ...

, but it is now known that this is not generally the case; the species involved are less closely related to one another. Today, botanists suggest three possible causes for the observed morphological similarity, which probably developed at different times and via different pathways; the species pairs are: (1)the products of similar environmental conditions in separate locations, (2)relics of species that were formerly widely distributed but diversified later, (3)not as morphologically similar as was previously believed. Gray's work in this area gave significant support to Darwin's theory of evolution

''Darwinism'' is a term used to describe a theory of biological evolution developed by the English naturalist Charles Darwin (1809–1882) and others. The theory states that all species of organisms arise and develop through the natural sele ...

and is one of the hallmarks of Gray's career. In 1880 David P. Penhallow was accepted by Gray as a research assistant. Penhallow aided in Gray's work regarding the distribution of northern hemisphere plants, and in 1882 Gray recommended Penhallow as a lecturer to Sir John Dawson of McGill University

McGill University (French: Université McGill) is an English-language public research university in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. Founded in 1821 by royal charter,Frost, Stanley Brice. ''McGill University, Vol. I. For the Advancement of Learning, ...

in Montreal, Quebec

Montreal is the List of towns in Quebec, largest city in the Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Quebec, the List of the largest municipalities in Canada by population, second-largest in Canada, and the List of North American cit ...

, Canada.

Later career

Despite no longer having the burden of his professorial and garden duties, by the late 1870s the burden of maintaining himself as the pillar of American botany prevented Gray from the progress he desired on ''Synoptical Flora of North America'', the follow-on to ''Flora of North America''. This burden consisted of the fact that other scientists often only accepted Gray's word on a botanical matter, and the number of incoming specimens to identify was increasing vastly: numbers had to be assigned to them, collectors needed to be corresponded with, and preliminary papers had to be published. By the early 1880s, Gray's home was the center of everything to do with botany in America. Every aspiring botanist came to see him, even if just to look at him through his window. After turning over his non-research duties to Sargent, Goodale, Farlow, and Watson, Gray concentrated more on research and writing, especially onplant taxonomy

Plant taxonomy is the science that finds, identifies, describes, classifies, and names plants. It is one of the main branches of taxonomy (the science that finds, describes, classifies, and names living things).

Plant taxonomy is closely allied ...

, as well as lecturing around the country, largely promoting Darwinian ideas. Many of his lectures during this time were given at the Yale Divinity School

Yale Divinity School (YDS) is one of the twelve graduate and professional schools of Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut.

Congregationalist theological education was the motivation at the founding of Yale, and the professional school has ...

. Liberty Hyde Bailey

Liberty Hyde Bailey (March 15, 1858 – December 25, 1954) was an American Horticulture, horticulturist and reformer of rural life. He was cofounder of the American Society for Horticultural Science.Makers of American Botany, Harry Baker Humphrey ...

worked as Gray's herbarium assistant for two years during 1883–1884.

In spring 1887 Gray and his wife made their last trip to Europe, this one for six months from April–October, primarily to see Hooker.

Gray received the following advanced degrees: honorary degree of Master of Arts (1844) and Doctor of Laws (1875) from Harvard, and Doctor of Laws from Hamilton College (New York)

Hamilton College is a Private college, private Liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts college in Clinton, Oneida County, New York, Clinton, New York. It was established as the Hamilton-Oneida Academy in 1793 and received its c ...

(1860), McGill University

McGill University (French: Université McGill) is an English-language public research university in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. Founded in 1821 by royal charter,Frost, Stanley Brice. ''McGill University, Vol. I. For the Advancement of Learning, ...

(1884), and the University of Michigan (1887).

Research regarding the American West

Prior to 1840, besides what he had discovered during his trip to Europe, Gray's knowledge of the flora of the

Prior to 1840, besides what he had discovered during his trip to Europe, Gray's knowledge of the flora of the American West

The Western United States (also called the American West, the Western States, the Far West, the Western territories, and the West) is census regions United States Census Bureau

As American settlement in the U.S. expanded westward, the mea ...

was limited to what he could learn from Edwin James, who had been on the expedition to the West of Major Stephen Harriman Long

Stephen Harriman Long (December 30, 1784 – September 4, 1864) was an American army civil engineer, explorer, and inventor. As an inventor, he is noted for his developments in the design of steam locomotives. He was also one of the most pro ...

, and from Thomas Nuttall

Thomas Nuttall (5 January 1786 – 10 September 1859) was an English botanist and zoologist who lived and worked in America from 1808 until 1841.

Nuttall was born in the village of Long Preston, near Settle in the West Riding of Yorkshire a ...

, who had been on an expedition to the Pacific coast with Nathaniel Jarvis Wyeth

Nathaniel Jarvis Wyeth (January 29, 1802 – August 31, 1856) was an American inventor and businessman in Boston, Massachusetts who contributed greatly to its ice industry. Due to his inventions, Boston could harvest and ship ice internati ...

. In the latter half of 1840, Gray met the German-American botanist and physician George Engelmann

George Engelmann, also known as Georg Engelmann, (2 February 1809 – 4 February 1884) was a German-American botanist. He was instrumental in describing the flora (plants), flora of the west of North America, then very poorly known to Europeans; ...

in New York City. Engelmann took frequent trips to explore the American West and northern Mexico. The two remained close friends and botanical collaborators. Engelmann would send specimens to Gray, who would classify them and act as a sales agent. Their collaborations greatly enhanced botanical knowledge of those areas. Another German-American botanist, Ferdinand Lindheimer

Ferdinand Jacob Lindheimer (May 21, 1801 – December 2, 1879) was a German Texan botanist who spent his working life on the American frontier. In 1936, Recorded Texas Historic Landmark number 1590 was placed on Lindheimer's grave.

Biography Ear ...

, collaborated with both Engelmann and Gray, focusing on collecting plants in Texas

Texas ( , ; or ) is the most populous U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. It borders Louisiana to the east, Arkansas to the northeast, Oklahoma to the north, New Mexico to the we ...

, hoping to find specimens with "no Latin names". This cooperation resulted in issuing the exsiccata

Exsiccata (Latin, ''gen.'' -ae, ''plur.'' -ae) is a work with "published, uniform, numbered set of preserved specimens distributed with printed labels". Typically, exsiccatae are numbered collections of dried herbarium Biological specimen, spe ...

-like series ''Lindheimer Flora Texana exsiccata''. Another long-term and productive collaboration was with Charles Wright, who collected in Texas and New Mexico

New Mexico is a state in the Southwestern United States, Southwestern region of the United States. It is one of the Mountain States of the southern Rocky Mountains, sharing the Four Corners region with Utah, Colorado, and Arizona. It also ...

on two separate expeditions in 1849 and 1851–1852. These trips resulted in publication of the two-volume ''Plantae Wrightianae'' in 1852–1853.

Gray traveled to the American West on two separate occasions, the first in 1872 by train, and then again with

Gray traveled to the American West on two separate occasions, the first in 1872 by train, and then again with Joseph Dalton Hooker

Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker (30 June 1817 – 10 December 1911) was a British botanist and explorer in the 19th century. He was a founder of geographical botany and Charles Darwin's closest friend. For 20 years he served as director of the Ro ...

, son of William Hooker, in 1877. His wife accompanied him on both trips. Both times his goal was botanical research, and he avidly collected plant specimens to bring back with him to Harvard. On his second trip through the American West, he and Hooker reportedly collected over 1,000 specimens. Gray's and Hooker's research was reported in their joint 1880 publication, "The Vegetation of the Rocky Mountain Region and a Comparison with that of Other Parts of the World," which appeared in volume six of Hayden's ''Bulletin of the United States Geological and Geophysical Survey of the Territories''.

On both trips he climbed Grays Peak

Grays Peak is the tenth-highest summit of the Rocky Mountains of North America and the U.S. state of Colorado. The prominent fourteener is the highest summit of the Front Range and the highest point on the Continental Divide and the Contine ...

, one of Colorado's many fourteener

In the mountaineering parlance of the Western United States, a fourteener (also spelled 14er) is a mountain peak with an elevation of at least . The 96 fourteeners in the United States are all west of the Mississippi River. Colorado

Co ...

s. His wife climbed Grays Peak with him in 1872. This mountain was named after Gray by the botanist and explorer of the Rocky Mountains Charles Christopher Parry

image:Charles Christopher Parry.jpg, Parry circa 1875

Charles Christopher Parry (August 28, 1823 – February 20, 1890) was a British-American botanist and Mountaineering, mountaineer.

Biography

Parry was born in Gloucestershire, England, but mo ...

.

Prior to the 1870s, collecting in the western part of the country required slow horses, wagons, and often military escorts. But by this time, permanent settlements and railroads resulted in so many specimens coming in that Gray alone could not keep up with them. One of the post-war collectors who worked extensively with Gray was John Gill Lemmon

John Gill ("J.G.") Lemmon (January 2, 1832, Lima Township, Michigan – November 24, 1908, Oakland, California) was an American Botany, botanist and American Civil War, Civil War veteran and former prisoner of Andersonville prison, Andersonville. H ...

, husband of fellow botanist Sara Plummer Lemmon

Sara Allen Plummer Lemmon (1836–1923) was an American botanist. Mount Lemmon in Arizona is named for her, as she was the first Euro-American woman to ascend it. She was responsible for the designation of the golden poppy (''Eschscholzia califor ...

. Gray named a new genus ''Plummera'', now called ''Hymenoxys

''Hymenoxys'' (rubberweed or bitterweed) is a genus of plants in the sunflower family, native to North and South America. It was named by Alexandre Henri Gabriel de Cassini in 1828.

Plants of this genus are toxic to sheep due to the presence of ...

'', in Sara's honor.

Relationship with Darwin

Gray andJoseph Dalton Hooker

Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker (30 June 1817 – 10 December 1911) was a British botanist and explorer in the 19th century. He was a founder of geographical botany and Charles Darwin's closest friend. For 20 years he served as director of the Ro ...

went to visit Richard Owen

Sir Richard Owen (20 July 1804 – 18 December 1892) was an English biologist, comparative anatomy, comparative anatomist and paleontology, palaeontologist. Owen is generally considered to have been an outstanding naturalist with a remarkabl ...

at London's Hunterian Museum

The Hunterian is a complex of museums located in and operated by the University of Glasgow in Glasgow, Scotland. It is the oldest museum in Scotland. It covers the Hunterian Museum, the Hunterian Art Gallery, the Mackintosh House, the Zoology M ...

in January 1839. Gray met Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English Natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci ...

during lunch that day at Kew Gardens

Kew Gardens is a botanical garden, botanic garden in southwest London that houses the "largest and most diverse botany, botanical and mycology, mycological collections in the world". Founded in 1759, from the exotic garden at Kew Park, its li ...

, apparently introduced by Hooker. Darwin found a kindred spirit in Gray, as they both had an empirical

Empirical evidence is evidence obtained through sense experience or experimental procedure. It is of central importance to the sciences and plays a role in various other fields, like epistemology and law.

There is no general agreement on how t ...

approach to science, and first wrote to him in April 1855. During 1855–1881 they exchanged about 300 letters. Darwin then wrote to Gray requesting information about the distribution of various species of American flowers, which Gray provided, and which was helpful for the development of Darwin's theory

Following the inception of Darwin's theory, inception of Charles Darwin's theory of natural selection in 1838, the development of Darwin's theory to explain the "mystery of mysteries" of how new species originated was his "prime hobby" in the bac ...

. This was the beginning of an extensive lifelong correspondence.

Gray, Darwin, and Hooker became lifelong friends and colleagues, and Gray and Hooker conducted research on Darwin's behalf in 1877 on their Rocky Mountain

The Rocky Mountains, also known as the Rockies, are a major mountain range and the largest mountain system in North America. The Rocky Mountains stretch in straight-line distance from the northernmost part of Western Canada, to New Mexico in ...

expedition. After Hooker returned to England and reported to Darwin on their adventure, Darwin wrote back to Gray: "I have just ... heard prodigies of your strength & activity. That you run up a mountain like a cat!"

Before 1846, Gray had been firmly opposed to the idea of transmutation of species

The Transmutation of species and transformism are 18th and early 19th-century ideas about the change of one species into another that preceded Charles Darwin's theory of evolution through natural selection. The French ''Transformisme'' was a ter ...

, in which simpler forms naturally become more complex over time, including via hybridization. By the early 1850s, Gray had clearly defined his concept that the species

A species () is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate sexes or mating types can produce fertile offspring, typically by sexual reproduction. It is the basic unit of Taxonomy (biology), ...

is the basic unit of taxonomy. This was partly the result of the 1831–1836 voyage during which Darwin discovered the differentiation of species among the various Galápagos Islands

The Galápagos Islands () are an archipelago of volcanic islands in the Eastern Pacific, located around the equator, west of the mainland of South America. They form the Galápagos Province of the Republic of Ecuador, with a population of sli ...

. Local geography could produce variances, like in the Galápagos and Hawaii, which Gray did not get to study in depth as he had wanted. Gray was insistent that a genetic connection must exist between all members of a species, that like begat like. This concept was critical to Darwin's theories. Gray was also strongly opposed to the ideas of hybridization within one generation and special creation

In Christian theology, special creation is a term with varying meanings dependent on context.

In creationism, the term refers to a belief that the universe and all life in it originated in its present form by fiat or divine decree.

Catholicism u ...

in the sense of its not allowing for evolution.

When Darwin received Alfred Russel Wallace

Alfred Russel Wallace (8 January 1823 – 7 November 1913) was an English naturalist, explorer, geographer, anthropologist, biologist and illustrator. He independently conceived the theory of evolution through natural selection; his 1858 pap ...

's paper that described natural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the Heredity, heritable traits characteristic of a population over generation ...

, Hooker and Charles Lyell

Sir Charles Lyell, 1st Baronet, (14 November 1797 – 22 February 1875) was a Scottish geologist who demonstrated the power of known natural causes in explaining the earth's history. He is best known today for his association with Charles ...

arranged for a joint reading of papers by Darwin and Wallace to the Linnean Society

The Linnean Society of London is a learned society dedicated to the study and dissemination of information concerning natural history, evolution, and taxonomy. It possesses several important biological specimen, manuscript and literature collec ...

on July 1, 1858. Since Darwin had nothing prepared, the reading included excerpts from his 1844 ''Essay'' and from a letter he had sent to Asa Gray in July 1857 outlining his theory on the origin of species. By that time, Darwin had begun writing his book ''On the Origin of Species

''On the Origin of Species'' (or, more completely, ''On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life'')The book's full original title was ''On the Origin of Species by M ...

''. The correspondence with Gray was thus a key piece of evidence in establishing Darwin's intellectual priority with respect to the theory of evolution by natural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the heritable traits characteristic of a population over generations. Charle ...

. Neither Darwin nor Wallace attended the meeting. The papers were published by the society as ''On the Tendency of Species to form Varieties; and on the Perpetuation of Varieties and Species by Natural Means of Selection

"On the Tendency of Species to form Varieties; and on the Perpetuation of Varieties and Species by Natural Means of Selection" is the title of a journal article, comprising and resulting from the joint presentation of two scientific papers to th ...

''. By summer 1859 it was obvious to Gray and others working with Darwin that ''On the Origin of Species'' would be a ground-breaking book.