Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev (2 March 1931 – 30 August 2022) was a Soviet and Russian politician who served as the last

leader of the Soviet Union

During its 69-year history, the Soviet Union usually had a '' de facto'' leader who would not always necessarily be head of state or even head of government but would lead while holding an office such as Communist Party General Secretary. Th ...

from 1985 to

the country's dissolution in 1991. He served as

General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

The General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. was the Party leader, leader of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU). From 1924 until the dissolution of the Soviet Union, country's dissoluti ...

from 1985 and additionally as

head of state

A head of state is the public persona of a sovereign state.#Foakes, Foakes, pp. 110–11 "he head of state

He or HE may refer to:

Language

* He (letter), the fifth letter of the Semitic abjads

* He (pronoun), a pronoun in Modern English

* He (kana), one of the Japanese kana (へ in hiragana and ヘ in katakana)

* Ge (Cyrillic), a Cyrillic letter cal ...

being an embodiment of the State itself or representative of its international persona." The name given to the office of head of sta ...

beginning in 1988, as Chairman of the

Presidium of the Supreme Soviet

The Presidium of the Supreme Soviet () was the standing body of the highest organ of state power, highest body of state authority in the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR).The Presidium of the Soviet Union is, in short, the legislativ ...

from 1988 to 1989, Chairman of the

Supreme Soviet

The Supreme Soviet () was the common name for the legislative bodies (parliaments) of the Soviet socialist republics (SSR) in the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR). These soviets were modeled after the Supreme Soviet of the USSR, establ ...

from 1989 to 1990 and the

president of the Soviet Union

The president of the Soviet Union (), officially the president of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (), abbreviated as president of the USSR (), was the executive head of state of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics from 15 March ...

from 1990 to 1991. Ideologically, Gorbachev initially adhered to

Marxism–Leninism

Marxism–Leninism () is a communist ideology that became the largest faction of the History of communism, communist movement in the world in the years following the October Revolution. It was the predominant ideology of most communist gov ...

but moved towards

social democracy

Social democracy is a Social philosophy, social, Economic ideology, economic, and political philosophy within socialism that supports Democracy, political and economic democracy and a gradualist, reformist, and democratic approach toward achi ...

by the early 1990s.

Gorbachev was born in

Privolnoye,

North Caucasus Krai

North Caucasus Krai (, ''Severo-Kavkazskiy kray'') was an administrative division (''krai'') within the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic of the Soviet Union. It was established on 17 October 1924. Its administrative center was Rost ...

, to a poor peasant family of Russian and Ukrainian heritage. Growing up under the

rule of Joseph Stalin

Rule or ruling may refer to:

Human activity

* The exercise of political or personal control by someone with authority or power

* Business rule, a rule pertaining to the structure or behavior internal to a business

* School rule, a rule th ...

, in his youth he operated

combine harvester

The modern combine harvester, also called a combine, is a machine designed to harvest a variety of cultivated seeds. Combine harvesters are one of the most economically important labour-saving inventions, significantly reducing the fraction of ...

s on a

collective farm

Collective farming and communal farming are various types of "agricultural production in which multiple farmers run their holdings as a joint enterprise". There are two broad types of communal farms: agricultural cooperatives, in which member-o ...

before joining the

Communist Party, which then governed the

Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

as a

one-party state

A one-party state, single-party state, one-party system or single-party system is a governance structure in which only a single political party controls the ruling system. In a one-party state, all opposition parties are either outlawed or en ...

. Studying at

Moscow State University

Moscow State University (MSU), officially M. V. Lomonosov Moscow State University,. is a public university, public research university in Moscow, Russia. The university includes 15 research institutes, 43 faculties, more than 300 departments, a ...

, he married fellow student

Raisa Titarenko in 1953 and received his law degree in 1955. Moving to

Stavropol

Stavropol (, ), known as Voroshilovsk from 1935 until 1943, is a city and the administrative centre of Stavropol Krai, in southern Russia. As of the 2021 Census, its population was 547,820, making it one of Russia's fastest growing cities.

E ...

, he worked for the

Komsomol

The All-Union Leninist Young Communist League, usually known as Komsomol, was a political youth organization in the Soviet Union. It is sometimes described as the youth division of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU), although it w ...

youth organization and, after Stalin's death, became a keen proponent of the

de-Stalinization

De-Stalinization () comprised a series of political reforms in the Soviet Union after Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, the death of long-time leader Joseph Stalin in 1953, and Khrushchev Thaw, the thaw brought about by ascension of Nik ...

reforms of Soviet leader

Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and the Premier of the Soviet Union, Chai ...

. He was appointed the First Party Secretary of the Stavropol Regional Committee in 1970, overseeing the construction of the

Great Stavropol Canal

The Great Stavropol Canal () is an irrigation canal in Stavropol Krai in Russia. It starts at a dam at Ust-Dzheguta on the upper Kuban River and leads water northeast via the Kalaus (river), Kalaus River to the Chogray Reservoir on the Manych Ri ...

. In 1978, he returned to Moscow to become a Secretary of the party's

Central Committee; he joined the governing

Politburo

A politburo () or political bureau is the highest organ of the central committee in communist parties. The term is also sometimes used to refer to similar organs in socialist and Islamist parties, such as the UK Labour Party's NEC or the Poli ...

(

25th term) as a non-voting member in 1979 and a voting member in 1980. Three years after the death of Soviet leader

Leonid Brezhnev

Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev (19 December 190610 November 1982) was a Soviet politician who served as the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1964 until Death and state funeral of Leonid Brezhnev, his death in 1982 as w ...

—following the brief tenures of

Yuri Andropov

Yuri Vladimirovich Andropov ( – 9 February 1984) was a Soviet politician who served as the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from late 1982 until his death in 1984. He previously served as the List of Chairmen of t ...

and

Konstantin Chernenko

Konstantin Ustinovich Chernenko ( – 10 March 1985) was a Soviet politician who served as the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1984 until his death a year later.

Born to a poor family in Siberia, Chernenko jo ...

—in 1985, the Politburo elected Gorbachev as general secretary, the ''de facto'' leader.

Although committed to preserving the Soviet state and its Marxist–Leninist ideals, Gorbachev believed significant reform was necessary for its survival. He

withdrew troops from the

Soviet–Afghan War

The Soviet–Afghan War took place in the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan from December 1979 to February 1989. Marking the beginning of the 46-year-long Afghan conflict, it saw the Soviet Union and the Armed Forces of the Democratic Republic o ...

and embarked on summits with United States president

Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan (February 6, 1911 – June 5, 2004) was an American politician and actor who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He was a member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party a ...

to limit

nuclear weapon

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission or atomic bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions (thermonuclear weapon), producing a nuclear exp ...

s and end the

Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

. Domestically, his policy of ''

glasnost

''Glasnost'' ( ; , ) is a concept relating to openness and transparency. It has several general and specific meanings, including a policy of maximum openness in the activities of state institutions and freedom of information and the inadmissi ...

'' ("openness") allowed for enhanced

freedom of speech

Freedom of speech is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or a community to articulate their opinions and ideas without fear of retaliation, censorship, or legal sanction. The rights, right to freedom of expression has been r ...

and

press

Press may refer to:

Media

* Publisher

* News media

* Printing press, commonly called "the press"

* Press TV, an Iranian television network

Newspapers United States

* ''The Press'', a former name of ''The Press-Enterprise'', Riverside, California

...

, while his ''

perestroika

''Perestroika'' ( ; rus, перестройка, r=perestrojka, p=pʲɪrʲɪˈstrojkə, a=ru-perestroika.ogg, links=no) was a political reform movement within the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) during the late 1980s, widely associ ...

'' ("restructuring") sought to decentralize economic decision-making to improve its efficiency. Ultimately, Gorbachev's

democratization

Democratization, or democratisation, is the structural government transition from an democratic transition, authoritarian government to a more democratic political regime, including substantive political changes moving in a democratic direction ...

measures and formation of the elected

Congress of People's Deputies undermined the one-party state. When various

Warsaw Pact

The Warsaw Pact (WP), formally the Treaty of Friendship, Co-operation and Mutual Assistance (TFCMA), was a Collective security#Collective defense, collective defense treaty signed in Warsaw, Polish People's Republic, Poland, between the Sovi ...

countries

abandoned Marxist–Leninist governance in 1989, he declined to intervene militarily. Growing

nationalist

Nationalism is an idea or movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the State (polity), state. As a movement, it presupposes the existence and tends to promote the interests of a particular nation,Anthony D. Smith, Smith, A ...

sentiment within

constituent republics threatened to break up the Soviet Union, leading hardliners within the

Communist Party to launch

an unsuccessful coup against Gorbachev in August 1991. In the coup's wake, the

Soviet Union dissolved

The Soviet Union was formally dissolved as a sovereign state and subject of international law on 26 December 1991 by Declaration No. 142-N of the Soviet of the Republics of the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union. Declaration No. 142-Н of t ...

against Gorbachev's wishes. After resigning from the presidency, he launched the

Gorbachev Foundation

The Gorbachev Foundation (, ''Gorbachyov-Fond'') is a non-profit organization headquartered in Moscow, founded by the former Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev in December 1991 and began its work in January 1992. The foundation researches the Pere ...

, became a vocal critic of Russian presidents

Boris Yeltsin

Boris Nikolayevich Yeltsin (1 February 1931 – 23 April 2007) was a Soviet and Russian politician and statesman who served as President of Russia from 1991 to 1999. He was a member of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) from 1961 to ...

and

Vladimir Putin

Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin (born 7 October 1952) is a Russian politician and former intelligence officer who has served as President of Russia since 2012, having previously served from 2000 to 2008. Putin also served as Prime Minister of Ru ...

, and campaigned for Russia's social-democratic movement.

Considered one of the most significant figures of the second half of the 20th century, Gorbachev remains controversial. The recipient of a wide range of awards, including the

Nobel Peace Prize

The Nobel Peace Prize (Swedish language, Swedish and ) is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the Will and testament, will of Sweden, Swedish industrialist, inventor, and armaments manufacturer Alfred Nobel, along with the prizes in Nobe ...

, he was praised for his role in ending the Cold War, introducing new political and economic freedoms in the Soviet Union, and tolerating both the fall of Marxist–Leninist administrations in eastern and central Europe and the

German reunification

German reunification () was the process of re-establishing Germany as a single sovereign state, which began on 9 November 1989 and culminated on 3 October 1990 with the dissolution of the East Germany, German Democratic Republic and the int ...

. Critics see him as weakening Russia's global influence and precipitating an

economic collapse in the country.

Early life and education

1931–1950: Childhood and adolescence

Gorbachev was born on 2 March 1931 in the village of

Privolnoye, then in the

North Caucasus Krai

North Caucasus Krai (, ''Severo-Kavkazskiy kray'') was an administrative division (''krai'') within the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic of the Soviet Union. It was established on 17 October 1924. Its administrative center was Rost ...

of the

Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (Russian SFSR or RSFSR), previously known as the Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic and the Russian Soviet Republic, and unofficially as Soviet Russia,Declaration of Rights of the labo ...

,

Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

. At the time, Privolnoye was divided between ethnic Russians and Ukrainians. Gorbachev's paternal family were

Russians

Russians ( ) are an East Slavs, East Slavic ethnic group native to Eastern Europe. Their mother tongue is Russian language, Russian, the most spoken Slavic languages, Slavic language. The majority of Russians adhere to Eastern Orthodox Church ...

and had moved from

Voronezh

Voronezh ( ; , ) is a city and the administrative centre of Voronezh Oblast in southwestern Russia straddling the Voronezh River, located from where it flows into the Don River. The city sits on the Southeastern Railway, which connects wes ...

several generations before; his maternal family were of ethnic

Ukrainian heritage and had migrated from

Chernihiv

Chernihiv (, ; , ) is a city and municipality in northern Ukraine, which serves as the administrative center of Chernihiv Oblast and Chernihiv Raion within the oblast. Chernihiv's population is

The city was designated as a Hero City of Ukraine ...

. His parents named him Viktor at birth, but at his mother's insistence he had a secret

baptism

Baptism (from ) is a Christians, Christian sacrament of initiation almost invariably with the use of water. It may be performed by aspersion, sprinkling or affusion, pouring water on the head, or by immersion baptism, immersing in water eit ...

, where his grandfather christened him Mikhail. His relationship with his father, Sergey Andreyevich Gorbachev, was close; his mother, Maria Panteleyevna Gorbacheva (née Gopkalo), was colder and punitive. His parents were poor, and lived as peasants. They had married as teenagers in 1928, and in keeping with local tradition had initially resided in Sergey's father's house, an

adobe

Adobe (from arabic: الطوب Attub ; ) is a building material made from earth and organic materials. is Spanish for mudbrick. In some English-speaking regions of Spanish heritage, such as the Southwestern United States, the term is use ...

-walled hut, before a hut of their own could be built.

The Soviet Union was a

one-party state

A one-party state, single-party state, one-party system or single-party system is a governance structure in which only a single political party controls the ruling system. In a one-party state, all opposition parties are either outlawed or en ...

governed by the

Communist Party, led by

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Dzhugashvili; 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and revolutionary who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

. Stalin had initiated a project of

mass rural collectivization meant to help convert the country into a

socialist society

The Socialist Society was founded in 1981 by a group of British socialists, including Raymond Williams and Ralph Miliband, who founded it as an organisation devoted to socialist education and research, linking the left of the British Labour Part ...

. Gorbachev's maternal grandfather joined the Communist Party and helped form the village's first

kolkhoz

A kolkhoz ( rus, колхо́з, a=ru-kolkhoz.ogg, p=kɐlˈxos) was a form of collective farm in the Soviet Union. Kolkhozes existed along with state farms or sovkhoz. These were the two components of the socialized farm sector that began to eme ...

(collective farm) in 1929, becoming its chair. It was outside Privolnoye, and when he was three years old, Gorbachev left his parental home and moved into the kolkhoz with his maternal grandparents.

The country was experiencing the

famine of 1930–1933, in which two of Gorbachev's paternal uncles and an aunt died. This was followed by the

Great Purge

The Great Purge, or the Great Terror (), also known as the Year of '37 () and the Yezhovshchina ( , ), was a political purge in the Soviet Union that took place from 1936 to 1938. After the Assassination of Sergei Kirov, assassination of ...

, in which individuals accused of being "

enemies of the people

The terms enemy of the people and enemy of the nation are designations for the political opponents and the social-class opponents of the power group within a larger social unit, who, thus identified, can be subjected to political repression. ...

" were interned in labor camps or executed. Both of Gorbachev's grandfathers served time in labor camps. After his December 1938 release, Gorbachev's maternal grandfather discussed having been tortured by

the secret police, an account that influenced the young boy.

During the

Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, in June 1941 the

German Army

The German Army (, 'army') is the land component of the armed forces of Federal Republic of Germany, Germany. The present-day German Army was founded in 1955 as part of the newly formed West German together with the German Navy, ''Marine'' (G ...

invaded the Soviet Union. German forces occupied Privolnoye for four and a half months in 1942. Gorbachev's father fought on the frontlines; he was wrongly declared dead during the conflict and fought in the

Battle of Kursk

The Battle of Kursk, also called the Battle of the Kursk Salient, was a major World War II Eastern Front battle between the forces of Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union near Kursk in southwestern Russia during the summer of 1943, resulting in ...

before returning to his family, injured. After Germany was defeated, Gorbachev's parents had their second son, Aleksandr, in 1947; he and Mikhail were their only children.

The village school was closed during much of the war, re-opening in autumn 1944. Gorbachev did not want to return but excelled academically when he did. He read voraciously, moving from the Western novels of

Thomas Mayne Reid

Thomas Mayne Reid (4 April 1818 – 22 October 1883) was an Irish British novelist who fought in the Mexican–American War (1846–1848). His many works on American life describe colonial policy in the American colonies, the horrors of slave ...

to the works of

Vissarion Belinsky

Vissarion Grigoryevich Belinsky (; Pre-reform spelling: Виссаріонъ Григорьевичъ Бѣлинскій. – ) was a Russian literary critic of Westernizing tendency. Belinsky played one of the key roles in the career of p ...

,

Alexander Pushkin

Alexander Sergeyevich Pushkin () was a Russian poet, playwright, and novelist of the Romantic era.Basker, Michael. Pushkin and Romanticism. In Ferber, Michael, ed., ''A Companion to European Romanticism''. Oxford: Blackwell, 2005. He is consid ...

,

Nikolai Gogol

Nikolai Vasilyevich Gogol; ; (; () was a Russian novelist, short story writer, and playwright of Ukrainian origin.

Gogol used the Grotesque#In literature, grotesque in his writings, for example, in his works "The Nose (Gogol short story), ...

, and

Mikhail Lermontov

Mikhail Yuryevich Lermontov ( , ; rus, Михаи́л Ю́рьевич Ле́рмонтов, , mʲɪxɐˈil ˈjʉrʲjɪvʲɪtɕ ˈlʲerməntəf, links=yes; – ) was a Russian Romanticism, Romantic writer, poet and painter, sometimes called ...

. In 1946, he joined the

Komsomol

The All-Union Leninist Young Communist League, usually known as Komsomol, was a political youth organization in the Soviet Union. It is sometimes described as the youth division of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU), although it w ...

, the Soviet political youth organization, becoming leader of his local group, and was then elected to the Komsomol committee for the district. From primary school he moved to the high school in

Molotovskoye; he stayed there during the week and walked the home during weekends. As well as being a member of the school's drama society, he organized sporting and social activities and led the school's morning exercise class. Over the course of five consecutive summers starting with 1946, he returned home to assist his father in operating a combine harvester; during those summers, they sometimes worked 20-hour days. In 1948, they harvested over 8,000

centners of grain, a feat for which Sergey was awarded the

Order of Lenin

The Order of Lenin (, ) was an award named after Vladimir Lenin, the leader of the October Revolution. It was established by the Central Executive Committee on 6 April 1930. The order was the highest civilian decoration bestowed by the Soviet ...

and his son the

Order of the Red Banner of Labour

The Order of the Red Banner of Labour () was an order of the Soviet Union established to honour great deeds and services to the Soviet state and society in the fields of production, science, culture, literature, the arts, education, sports ...

.

1950–1955: University

In June 1950, Gorbachev became a candidate member of the Communist Party. He applied to study at the law school of

Moscow State University

Moscow State University (MSU), officially M. V. Lomonosov Moscow State University,. is a public university, public research university in Moscow, Russia. The university includes 15 research institutes, 43 faculties, more than 300 departments, a ...

(MSU), then the most prestigious university in the country. They accepted him without asking for an exam, likely because of his worker-peasant origins and his possession of the Order of the Red Banner of Labour. His choice of law was unusual; it was not a well-regarded subject in Soviet society at that time. At age 19, he traveled by train to Moscow, the first time he had left his home region.

In Moscow, Gorbachev resided with fellow MSU students at a dormitory in the

Sokolniki District

Sokolniki District () is a district of the Eastern Administrative Okrug of the federal city of Moscow located in the north-east corner of the city. Population:

Etymology

Sokolniki derives its name from the word "" (''sokol'', meaning "falcon") ...

. He felt at odds with his urban counterparts, but soon came to fit in. Fellow students recall his working especially hard, often late into the night. He gained a reputation as a mediator during disputes and was outspoken in class, but was private about his views; for instance, he confided in some students his opposition to the Soviet jurisprudential norm that a confession proved guilt, noting that confessions could have been forced. During his studies, an

antisemitic

Antisemitism or Jew-hatred is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who harbours it is called an antisemite. Whether antisemitism is considered a form of racism depends on the school of thought. Antisemi ...

campaign spread through the Soviet Union, culminating in the

Doctors' plot

The "doctors' plot" () was a Soviet state-sponsored anti-intellectual and anti-cosmopolitan campaign based on a conspiracy theory that alleged an anti-Soviet cabal of prominent medical specialists, including some of Jewish ethnicity, intend ...

; Gorbachev publicly defended Volodya Liberman, a Jewish student accused of disloyalty.

At MSU, Gorbachev became the Komsomol head of his entering class, and then Komsomol's deputy secretary for agitation and propaganda at the law school. One of his first Komsomol assignments in Moscow was to monitor the election polling in

Presnensky District

Presnensky District (), commonly called Presnya (), is a district of Central Administrative Okrug of the federal city of Moscow, Russia. Population:

The district is home to the Moscow Zoo, White House of Russia, Kudrinskaya Square Building, ...

to ensure near-total turnout; Gorbachev found that most people voted "out of fear". In 1952, he was appointed a full member of the Communist Party. He was tasked with monitoring fellow students for subversion; some of his fellow students said he did so only minimally and that they trusted him to keep confidential information secret from the authorities. Gorbachev became close friends with

Zdeněk Mlynář

Zdeněk Mlynář (born Zdeněk Müller; 22 June 1930 – 15 April 1997) was a Czech Communist politician and lawyer. He was the secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia during the 1968 Prague Spring. Mlynář ...

, a

Czechoslovak

Czechoslovak may refer to:

*A demonym or adjective pertaining to Czechoslovakia (1918–93)

**First Czechoslovak Republic (1918–38)

**Second Czechoslovak Republic (1938–39)

**Third Czechoslovak Republic (1948–60)

** Fourth Czechoslovak Repu ...

student who later became a primary ideologist of the 1968

Prague Spring

The Prague Spring (; ) was a period of liberalization, political liberalization and mass protest in

the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic. It began on 5 January 1968, when reformist Alexander Dubček was elected Secretary (title), First Secre ...

. Mlynář recalled that the duo remained committed Marxist–Leninists despite their growing concerns about the

Stalinist

Stalinism (, ) is the totalitarian means of governing and Marxist–Leninist policies implemented in the Soviet Union (USSR) from 1927 to 1953 by dictator Joseph Stalin and in Soviet satellite states between 1944 and 1953. Stalinism in ...

system. After Stalin died in March 1953, Gorbachev and Mlynář joined the crowds massing to see Stalin's body lying in state.

At MSU, Gorbachev met

Raisa Titarenko, who was studying in the university's philosophy department. She was engaged to another man, but after that engagement fell apart, she began a relationship with Gorbachev; together they went to bookstores, museums, and art exhibits. In early 1953, he took an internship at the procurator's office in Molotovskoye district, but he was angered by the incompetence and arrogance of those working there. That summer, he returned to Privolnoye to work with his father on the harvest; the money earned allowed him to pay for his wedding. On 25 September 1953 he and Raisa registered their marriage at Sokolniki Registry Office and in October moved in together at the

Lenin Hills dormitory. Raisa discovered that she was pregnant and although the couple wanted to keep the child she fell ill and required an abortion.

In June 1955, Gorbachev graduated with a distinction; his final paper had been on the advantages of "socialist democracy" over "bourgeois democracy" (

liberal democracy

Liberal democracy, also called Western-style democracy, or substantive democracy, is a form of government that combines the organization of a democracy with ideas of liberalism, liberal political philosophy. Common elements within a liberal dem ...

). He was subsequently assigned to the

Soviet Procurator's office, which was focusing on the rehabilitation of the innocent victims of Stalin's purges, but found that they had no work for him. He was then offered a place on an MSU graduate course specializing in kolkhoz law, but declined. He had wanted to remain in Moscow, where Raisa was enrolled in a PhD program, but instead gained employment in

Stavropol

Stavropol (, ), known as Voroshilovsk from 1935 until 1943, is a city and the administrative centre of Stavropol Krai, in southern Russia. As of the 2021 Census, its population was 547,820, making it one of Russia's fastest growing cities.

E ...

; Raisa abandoned her studies to join him there.

Early CPSU career

1955–1969: Stavropol Komsomol

In August 1955, Gorbachev started work at the Stavropol regional procurator's office, but disliked it and got a transfer to work for Komsomol, becoming deputy director of Komsomol's agitation and propaganda department for that region. In this position, he visited villages in the area and tried to improve the lives of their inhabitants; he established a discussion circle in Gorkaya Balka to help its peasant residents gain social contacts.

Gorbachev and his wife Raisa initially rented a small room in Stavropol, taking daily evening walks around the city and on weekends hiking in the countryside. In January 1957, Raisa gave birth to a daughter, Irina, and in 1958 they moved into two rooms in a

communal apartment

Communal apartments (, colloquial: ''kommunalka'') are apartments in which several unrelated persons or families live in isolated living rooms and share common areas such a kitchen, shower, and toilet. When the Bolsheviks came to power in 1917 aft ...

. In 1961, Gorbachev pursued a second degree, in agricultural production; he took a

correspondence course

Distance education, also known as distance learning, is the education of students who may not always be physically present at school, or where the learner and the teacher are separated in both time and distance; today, it usually involves online ...

from the local Stavropol Agricultural Institute, receiving his diploma in 1967. His wife had also pursued a second degree, attaining a PhD in sociology in 1967 from the

Moscow State Pedagogical University

Moscow State Pedagogical University or Moscow State University of Education is an educational and scientific institution in Moscow, Russia, with eighteen faculties and seven branches operational in other Russian cities. The institution had under ...

; while in Stavropol she joined the Communist Party.

Stalin was succeeded as Soviet leader by

Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and the Premier of the Soviet Union, Chai ...

, who denounced Stalin and his

cult of personality

A cult of personality, or a cult of the leader,Cas Mudde, Mudde, Cas and Kaltwasser, Cristóbal Rovira (2017) ''Populism: A Very Short Introduction''. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 63. is the result of an effort which is made to create ...

in a

speech given in February 1956, after which he launched a

de-Stalinization

De-Stalinization () comprised a series of political reforms in the Soviet Union after Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, the death of long-time leader Joseph Stalin in 1953, and Khrushchev Thaw, the thaw brought about by ascension of Nik ...

process throughout Soviet society. Later biographer

William Taubman

William Chase Taubman (born November 13, 1941, in New York City) is an American political scientist. His biography of Nikita Khrushchev won the Pulitzer Prize for Biography in 2004 and the National Book Critics Circle Award for Biography in 2 ...

suggested that Gorbachev "embodied" the "reformist spirit" of the Khrushchev era. Gorbachev was among those who saw themselves as "genuine Marxists" or "genuine Leninists". He helped spread Khrushchev's anti-Stalinist message in Stavropol, but encountered many who saw Stalin as a hero and praised his purges as just.

Gorbachev rose steadily through the ranks of the local administration. The authorities regarded him as politically reliable, and he would flatter his superiors, for instance gaining favor with prominent local politician

Fyodor Kulakov

Fyodor Davydovich Kulakov () (4 February 1918 – 17 July 1978) was a Soviet statesman during the Cold War.

Kulakov served as Stavropol First Secretary from 1960 until 1964, immediately following Nikita Khrushchev's ouster. During his First Secre ...

. With an ability to outmanoeuvre rivals, some colleagues resented his success. In September 1956, he was promoted First Secretary of the Stavropol city's Komsomol, placing him in charge of it; in April 1958 he was made deputy head of the Komsomol for the entire region. He was given better accommodation: a two-room flat with its own private kitchen, toilet, and bathroom. In Stavropol, he formed a discussion club for youths, and helped mobilize local young people to take part in Khrushchev's agricultural and development campaigns.

In March 1961, Gorbachev became First Secretary of the regional Komsomol, in which position he went out of his way to appoint women as city and district leaders. In 1961, Gorbachev played host to the Italian delegation for the

World Youth Festival

The World Festival of Youth and Students is an international event organized by the World Federation of Democratic Youth (WFDY) and the International Union of Students after 1947. History

The festival has been held occasionally since 1947, mainl ...

in Moscow; that October, he attended the

22nd Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. In January 1963, Gorbachev was promoted to personnel chief for the regional party's agricultural committee, and in September 1966 became First Secretary of the Stavropol City Party Organization ("Gorkom"). By 1968 he was frustrated with his job—in large part because Khrushchev's reforms were stalling or being reversed—and he contemplated leaving politics to work in academia. However, in August 1968, he was named Second Secretary of the Stavropol Kraikom, making him the deputy of First Secretary Leonid Yefremov and the second most senior figure in Stavropol Krai. In 1969, he was elected as a deputy to the

Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union

The Supreme Soviet of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (SSUSSR) was the highest body of state authority of the Soviet Union (USSR) from 1936 to 1991. Based on the principle of unified power, it was the only branch of government in the So ...

and made a member of its Standing Commission for the Protection of the Environment.

Cleared for travel to

Eastern Bloc

The Eastern Bloc, also known as the Communist Bloc (Combloc), the Socialist Bloc, the Workers Bloc, and the Soviet Bloc, was an unofficial coalition of communist states of Central and Eastern Europe, Asia, Africa, and Latin America that were a ...

countries, in 1966 he was part of a delegation which visited East Germany, and in 1969 and 1974 visited People's Republic of Bulgaria, Bulgaria. In August 1968 Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia, the Soviet Union led an invasion of Czechoslovakia to put an end to the Prague Spring. Although Gorbachev later stated that he had had private concerns about the invasion, he publicly supported it. In September 1969 he was part of a Soviet delegation sent to Czechoslovakia, where he found the people largely unwelcoming. That year, the Soviet authorities ordered him to punish Fagim B. Sadygov, a philosophy professor of the Stavropol agricultural institute whose ideas were regarded as critical of Soviet agricultural policy; Gorbachev ensured that Sadykov was fired from teaching but ignored calls for him to face tougher punishment. Gorbachev later related that he was "deeply affected" by the incident; "my conscience tormented me" for overseeing Sadykov's persecution.

1970–1977: heading the Stavropol region

In April 1970, Yefremov was promoted to a higher position in Moscow and Gorbachev succeeded him as the First Secretary of the Stavropol kraikom. This granted Gorbachev significant power over the Stavropol region. He had been vetted for the position by senior Kremlin leaders and was informed of their decision by the Soviet leader,

Leonid Brezhnev

Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev (19 December 190610 November 1982) was a Soviet politician who served as the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1964 until Death and state funeral of Leonid Brezhnev, his death in 1982 as w ...

. Aged 39, he was considerably younger than his predecessors. As head of the Stavropol region, he automatically became a member of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (Central Committee of the 24th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, 24th term) in 1971. According to biographer Zhores Medvedev, Gorbachev "had now joined the Party's super-elite". As regional leader, Gorbachev initially attributed economic and other failures to "the inefficiency and incompetence of cadres, flaws in management structure or gaps in legislation", but eventually concluded that they were caused by an excessive centralization of decision making in Moscow. He began reading translations of restricted texts by Western Marxist authors such as Antonio Gramsci, Louis Aragon, Roger Garaudy, and Giuseppe Boffa, and came under their influence.

Gorbachev's main task as regional leader was to raise agricultural production levels, a task hampered by severe droughts in 1975 and 1976. He oversaw the expansion of irrigation systems through construction of the

Great Stavropol Canal

The Great Stavropol Canal () is an irrigation canal in Stavropol Krai in Russia. It starts at a dam at Ust-Dzheguta on the upper Kuban River and leads water northeast via the Kalaus (river), Kalaus River to the Chogray Reservoir on the Manych Ri ...

. For overseeing a record grain harvest in Ipatovsky district, in March 1972 he was awarded the Order of the October Revolution by Brezhnev in a Moscow ceremony. Gorbachev sought to maintain Brezhnev's trust; as regional leader, he repeatedly praised Brezhnev in his speeches, for instance referring to him as "the outstanding statesman of our time". Gorbachev and his wife holidayed in Moscow, Leningrad, Uzbekistan, and resorts in the North Caucasus; he holidayed with the head of the KGB,

Yuri Andropov

Yuri Vladimirovich Andropov ( – 9 February 1984) was a Soviet politician who served as the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from late 1982 until his death in 1984. He previously served as the List of Chairmen of t ...

, who was favorable towards him and who became an important patron. Gorbachev developed good relationships with senior figures including the Soviet prime minister, Alexei Kosygin, and the longstanding senior party member Mikhail Suslov.

The government considered Gorbachev sufficiently reliable to be sent in Soviet delegations to Western Europe; he made five trips there between 1970 and 1977. In September 1971 he was part of a delegation to Italy, where they met with representatives of the Italian Communist Party; Gorbachev loved Italian culture but was struck by the poverty and inequality he saw there. In 1972, he visited Belgium and the Netherlands, and in 1973 West Germany. Gorbachev and his wife visited France in 1976 and 1977, on the latter occasion touring the country with a guide from the French Communist Party. He was surprised by how openly West Europeans offered their opinions and criticized their political leaders, something absent from the Soviet Union, where most people did not feel safe speaking so openly. He later related that for him and his wife, these visits "shook our a priori belief in the superiority of socialist over bourgeois democracy".

Gorbachev had remained close to his parents; after his father became terminally ill in 1974, Gorbachev traveled to be with him in Privolnoe shortly before his death. His daughter, Irina, married fellow student Anatoly Virgansky in April 1978. In 1977, the Supreme Soviet appointed Gorbachev to chair the Standing Commission on Youth Affairs due to his experience with mobilizing young people in Komsomol.

Secretary of the Central Committee of CPSU

In November 1978, Gorbachev was appointed a Secretary of the Central Committee. His appointment was approved unanimously by the Central Committee's members. To fill this position, Gorbachev and his wife moved to Moscow, where they were initially given an old dacha outside the city. They then moved to another, at Sosnovka, before being allocated a newly built brick house. He was given an apartment inside the city, but gave that to his daughter and son-in-law; Irina had begun work at Moscow's Russian National Research Medical University, Second Medical Institute. As part of the Moscow political elite, Gorbachev and his wife now had access to better medical care and to specialized shops; they were given cooks, servants, bodyguards, and secretaries, many of these spies for the KGB. In his new position, Gorbachev often worked twelve to sixteen hour days. He and his wife socialized little, but liked to visit Moscow's theaters and museums.

In 1978, Gorbachev was appointed to the Central Committee's Secretariat for Agriculture (Secretariat of the 25th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, 25th term), replacing his old patron Kulakov, who had died of a heart attack. Gorbachev concentrated his attentions on agriculture: the harvests of 1979, 1980, and 1981 were all poor, due largely to weather conditions, and the country had to import increasing quantities of grain. He had growing concerns about the country's agricultural management system, coming to regard it as overly centralized and requiring more bottom-up decision making; he raised these points at his first speech at a Central Committee Plenum, given in July 1978. He began to have concerns about other policies too. In December 1979, the Soviets sent the Soviet Armed Forces, armed forces into Soviet–Afghan War, neighbouring Afghanistan to support its Democratic Republic of Afghanistan, Soviet-aligned government against Afghan mujahideen, Islamist insurgents; Gorbachev privately thought it a mistake. At times he openly supported the government position; in October 1980 he for instance endorsed Soviet calls for Poland's Marxist–Leninist government to crack down on Solidarity (Polish trade union), growing internal dissent in that country. That same month, he was promoted from a candidate member to a full member of the

Politburo

A politburo () or political bureau is the highest organ of the central committee in communist parties. The term is also sometimes used to refer to similar organs in socialist and Islamist parties, such as the UK Labour Party's NEC or the Poli ...

(

25th term), becoming the youngest member of the highest decision-making authority in the Communist Party. After Brezhnev's death in November 1982, Andropov succeeded him as General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, General Secretary of the Communist Party, the ''de facto'' leader in the Soviet Union. Gorbachev was enthusiastic about the appointment. However, although Gorbachev hoped that Andropov would introduce liberalizing reforms, the latter carried out only personnel shifts rather than structural change. Gorbachev became Andropov's closest ally in the Politburo; with Andropov's encouragement, Gorbachev sometimes chaired Politburo meetings. Andropov encouraged Gorbachev to expand into policy areas other than agriculture, preparing him for future higher office. In April 1983, in a sign of growing ascendancy, Gorbachev delivered the annual speech marking the birthday of the Soviet founder Vladimir Lenin; this required him re-reading many of Lenin's later writings, in which the latter had called for reform in the context of the New Economic Policy of the 1920s, and encouraged Gorbachev's own conviction that reform was needed. In May 1983, Gorbachev was sent to Canada, where he met Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau and spoke to the Parliament of Canada, Canadian Parliament. There, he met and befriended the Soviet ambassador, Aleksandr Yakovlev, who later became a key political ally.

In February 1984, Andropov died; on his deathbed he indicated his desire that Gorbachev succeed him. Many in the Central Committee nevertheless thought the 53-year-old Gorbachev was too young and inexperienced. Instead,

Konstantin Chernenko

Konstantin Ustinovich Chernenko ( – 10 March 1985) was a Soviet politician who served as the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1984 until his death a year later.

Born to a poor family in Siberia, Chernenko jo ...

—a longstanding Brezhnev ally—was appointed general secretary, but he too was in very poor health. Chernenko was often too sick to chair Politburo meetings, with Gorbachev stepping in last minute. Gorbachev continued to cultivate allies both in the Kremlin and beyond, and gave the main speech at a conference on Soviet ideology, where he angered party hardliners by implying that the country required reform.

In April 1984, Gorbachev was appointed chair of the Foreign Affairs Committee of the Soviet legislature, a largely honorific position. In June he traveled to Italy as a Soviet representative for the funeral of Italian Communist Party leader Enrico Berlinguer, and in September to Sofia, Bulgaria to attend celebrations of the fortieth anniversary of its liberation from the Nazis by the Red Army. In December, he visited Britain at the request of its prime minister Margaret Thatcher; she was aware that he was a potential reformer and wanted to meet him. At the end of the visit, Thatcher said: "I like Mr. Gorbachev. We can do business together". He felt that the visit helped to erode Andrei Gromyko's dominance of Soviet foreign policy and sent a signal to the United States government that he wanted to improve Soviet–US relations.

Leader of the Soviet Union (1985-1991)

On 11 March 1985, Mikhail Gorbachev was elected the eighth

General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

The General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. was the Party leader, leader of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU). From 1924 until the dissolution of the Soviet Union, country's dissoluti ...

by the Politburo of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, Politburo of the CPSU after the death of

Konstantin Chernenko

Konstantin Ustinovich Chernenko ( – 10 March 1985) was a Soviet politician who served as the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1984 until his death a year later.

Born to a poor family in Siberia, Chernenko jo ...

.

While Gorbachev wanted to preserve the Soviet Union and Marxism–Leninism, Marxist-Leninist ideals, he recognised the need for significant reforms. He decided to withdraw troops from the

Soviet–Afghan War

The Soviet–Afghan War took place in the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan from December 1979 to February 1989. Marking the beginning of the 46-year-long Afghan conflict, it saw the Soviet Union and the Armed Forces of the Democratic Republic o ...

and met with United States president

Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan (February 6, 1911 – June 5, 2004) was an American politician and actor who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He was a member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party a ...

at the Reykjavík Summit, Reykjavik Summit to discuss the limitation of

nuclear weapon

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission or atomic bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions (thermonuclear weapon), producing a nuclear exp ...

s production and ending the

Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

. He also proposed a three-stage programme for Nuclear disarmament, abolishing the List of states with nuclear weapons, world's nuclear weapons by the end of the 20th century.

Domestically, his policy of ''

glasnost

''Glasnost'' ( ; , ) is a concept relating to openness and transparency. It has several general and specific meanings, including a policy of maximum openness in the activities of state institutions and freedom of information and the inadmissi ...

'' ("openness") allowed for the improvement of

freedom of speech

Freedom of speech is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or a community to articulate their opinions and ideas without fear of retaliation, censorship, or legal sanction. The rights, right to freedom of expression has been r ...

and Freedom of the press, free press, while his ''

perestroika

''Perestroika'' ( ; rus, перестройка, r=perestrojka, p=pʲɪrʲɪˈstrojkə, a=ru-perestroika.ogg, links=no) was a political reform movement within the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) during the late 1980s, widely associ ...

'' ("restructuring") sought to decentralize economic decision-making to improve its efficiency. Ultimately, Gorbachev's

democratization

Democratization, or democratisation, is the structural government transition from an democratic transition, authoritarian government to a more democratic political regime, including substantive political changes moving in a democratic direction ...

efforts and formation of the elected

Congress of People's Deputies undermined the supremacy the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, CPSU had in Soviet governance.

[ ]

Russia

, section ''Demokratizatsiya''. Data as of July 1996 (retrieved December 25, 2014) When various

Warsaw Pact

The Warsaw Pact (WP), formally the Treaty of Friendship, Co-operation and Mutual Assistance (TFCMA), was a Collective security#Collective defense, collective defense treaty signed in Warsaw, Polish People's Republic, Poland, between the Sovi ...

countries

abandoned Marxist–Leninist governance in 1989, he declined to intervene militarily. Growing

nationalist

Nationalism is an idea or movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the State (polity), state. As a movement, it presupposes the existence and tends to promote the interests of a particular nation,Anthony D. Smith, Smith, A ...

sentiment within

constituent republics threatened to break up the Soviet Union, leading the hardliners within the

Communist Party to launch

an unsuccessful coup against Gorbachev in August 1991.

[

]

Unraveling of the USSR

In the Revolutions of 1989, most of the Marxist–Leninist states of Central and Eastern Europe held multi-party elections resulting in regime change. In most countries, like Poland and Hungary, this was achieved peacefully, but in Romania, the Romanian Revolution, revolution turned violent, and led to Ceaușescu's overthrow and execution. Gorbachev was too preoccupied with domestic problems to pay much attention to these events. He believed that democratic elections would not lead Eastern European countries into abandoning their commitment to socialism. In 1989, he visited East Germany for the fortieth anniversary of its founding; shortly after, in November, the East German government allowed its citizens to cross the Berlin Wall, a decision Gorbachev praised. Over the following years, much of the wall was demolished. Neither Gorbachev nor Thatcher or Mitterrand wanted a swift reunification of Germany, aware that it would likely become the dominant European power. Gorbachev wanted a gradual process of German integration but Kohl began calling for rapid reunification. With German reunification in 1990, many observers declared the Cold War over.

1990–1991: presidency of the Soviet Union

In February 1990, both liberalisers and Marxist–Leninist hardliners intensified their attacks on Gorbachev. A liberalizer march took place in Moscow criticizing Communist Party rule, while at a Central Committee meeting, the hardliner Vladimir Brovikov accused Gorbachev of reducing the country to "anarchy" and "ruin" and of pursuing Western approval at the expense of the Soviet Union and the Marxist–Leninist cause. Gorbachev was aware that the Central Committee could still oust him as general secretary, and so decided to reformulate the role of head of government to a presidency from which he could not be removed. He decided that the presidential election should be held by the Congress of People's Deputies. He chose this over a public vote because he thought the latter would escalate tensions and feared that he might lose it; a spring 1990 poll nevertheless still showed him as the most popular politician in the country.

In March, the Congress of People's Deputies held the first (and only) 1990 Soviet Union presidential election, Soviet presidential election, in which Gorbachev was the only candidate. He secured 1,329 in favor to 495 against; 313 votes were invalid or absent. He therefore became the first (and only) executive President of the Soviet Union. A new 18-member Presidential Council (USSR), Presidential Council ''de facto'' replaced the Politburo. At the same Congress meeting, he presented the idea of repealing Article 6 of the Soviet constitution, which had ratified the Communist Party as the "ruling party" of the Soviet Union. The Congress passed the reform, undermining the ''de jure'' nature of the one-party state.

In the 1990 Russian Supreme Soviet election, 1990 elections for the Supreme Soviet of Russia, Russian Supreme Soviet, the Communist Party faced challengers from an alliance of liberalisers known as "Democratic Russia"; the latter did particularly well in urban centers. Yeltsin was elected the parliament's chair, something Gorbachev was unhappy about. That year, opinion polls showed Yeltsin overtaking Gorbachev as the most popular politician in the Soviet Union. Gorbachev struggled to understand Yeltsin's growing popularity, commenting: "he drinks like a fish ... he's inarticulate, he comes up with the devil knows what, he's like a worn-out record". The Russian Supreme Soviet was now out of Gorbachev's control; in June 1990, it declared that in the Russian Republic, its laws took precedence over those of the Soviet central government. Amid a growth in Russian nationalism, Russian nationalist sentiment, Gorbachev had reluctantly allowed the formation of a Communist Party of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic as a branch of the larger Soviet Communist Party. Gorbachev attended its first congress in June, but soon found it dominated by hardliners who opposed his reformist stance.

In February 1990, both liberalisers and Marxist–Leninist hardliners intensified their attacks on Gorbachev. A liberalizer march took place in Moscow criticizing Communist Party rule, while at a Central Committee meeting, the hardliner Vladimir Brovikov accused Gorbachev of reducing the country to "anarchy" and "ruin" and of pursuing Western approval at the expense of the Soviet Union and the Marxist–Leninist cause. Gorbachev was aware that the Central Committee could still oust him as general secretary, and so decided to reformulate the role of head of government to a presidency from which he could not be removed. He decided that the presidential election should be held by the Congress of People's Deputies. He chose this over a public vote because he thought the latter would escalate tensions and feared that he might lose it; a spring 1990 poll nevertheless still showed him as the most popular politician in the country.

In March, the Congress of People's Deputies held the first (and only) 1990 Soviet Union presidential election, Soviet presidential election, in which Gorbachev was the only candidate. He secured 1,329 in favor to 495 against; 313 votes were invalid or absent. He therefore became the first (and only) executive President of the Soviet Union. A new 18-member Presidential Council (USSR), Presidential Council ''de facto'' replaced the Politburo. At the same Congress meeting, he presented the idea of repealing Article 6 of the Soviet constitution, which had ratified the Communist Party as the "ruling party" of the Soviet Union. The Congress passed the reform, undermining the ''de jure'' nature of the one-party state.

In the 1990 Russian Supreme Soviet election, 1990 elections for the Supreme Soviet of Russia, Russian Supreme Soviet, the Communist Party faced challengers from an alliance of liberalisers known as "Democratic Russia"; the latter did particularly well in urban centers. Yeltsin was elected the parliament's chair, something Gorbachev was unhappy about. That year, opinion polls showed Yeltsin overtaking Gorbachev as the most popular politician in the Soviet Union. Gorbachev struggled to understand Yeltsin's growing popularity, commenting: "he drinks like a fish ... he's inarticulate, he comes up with the devil knows what, he's like a worn-out record". The Russian Supreme Soviet was now out of Gorbachev's control; in June 1990, it declared that in the Russian Republic, its laws took precedence over those of the Soviet central government. Amid a growth in Russian nationalism, Russian nationalist sentiment, Gorbachev had reluctantly allowed the formation of a Communist Party of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic as a branch of the larger Soviet Communist Party. Gorbachev attended its first congress in June, but soon found it dominated by hardliners who opposed his reformist stance.

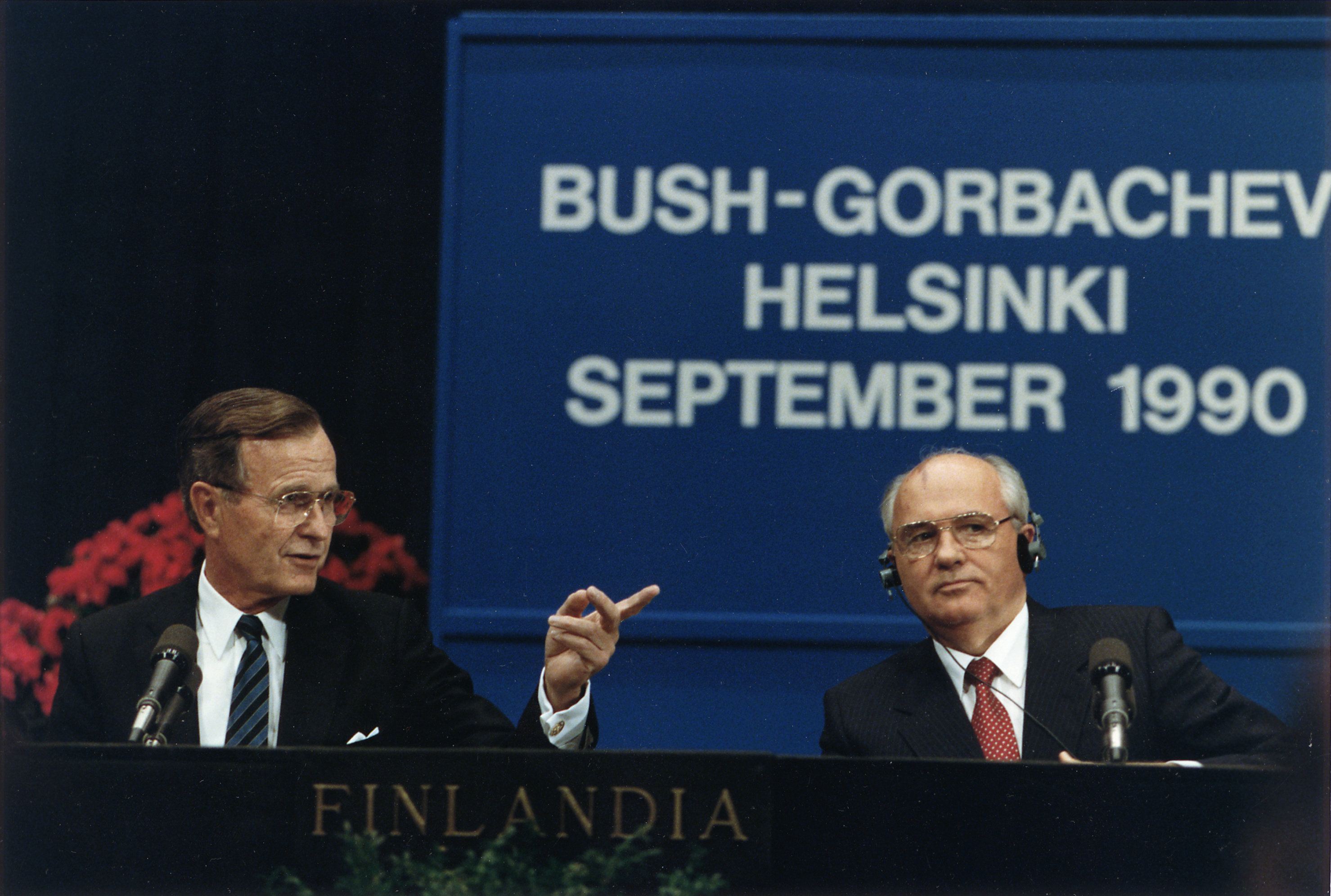

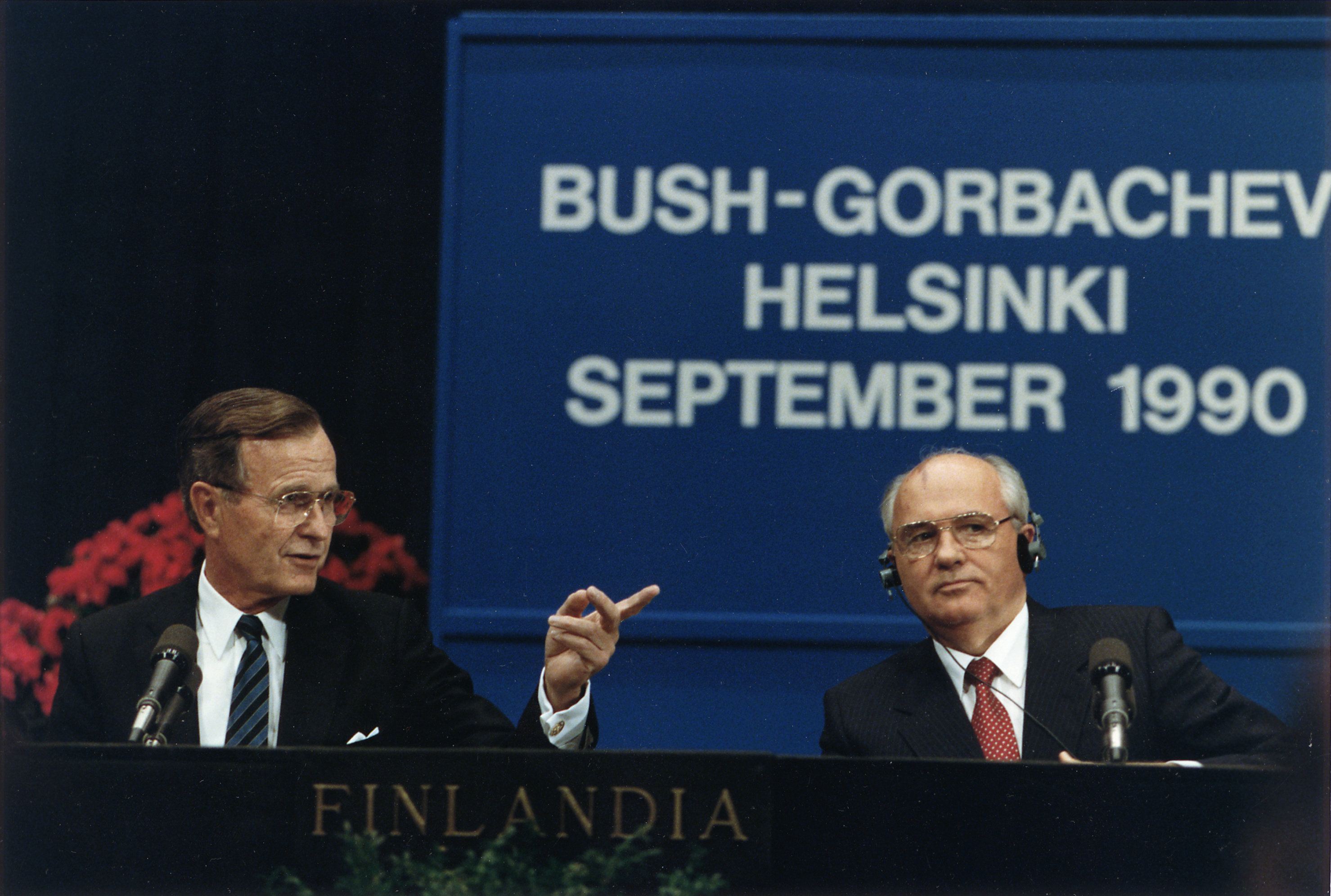

German reunification and the Gulf War

In January 1990, Gorbachev privately agreed to permit East German reunification with West Germany, but rejected the idea that a unified Germany could retain West Germany's NATO membership. His compromise that Germany might retain both NATO and Warsaw Pact memberships did not attract support. On 9 February 1990 in a phone conversation with James Baker, then the US secretary of state, he said that "a broadening of the NATO zone is not acceptable" to which Baker agreed. Scholars are puzzled why Gorbachev never pursued a written pledge. In August 1990, Saddam Hussein's Iraqi government Iraqi invasion of Kuwait, invaded Kuwait; Gorbachev endorsed President Bush's condemnation of it. This brought criticism from many in the Soviet state apparatus, who saw Hussein as a key ally in the Persian Gulf and feared for the safety of the 9,000 Soviet citizens in Iraq, although Gorbachev argued that the Iraqis were the clear aggressors. In November the Soviets endorsed United Nations Security Council Resolution 660, a UN Resolution permitting force to be used in expelling the Iraqi Army from Kuwait. Gorbachev later called it a "watershed" in world politics, "the first time the superpowers acted together in a regional crisis". However, when the US announced plans for Gulf War, a ground invasion, Gorbachev opposed it, urging instead a peaceful solution. In October 1990, Gorbachev was awarded the

In August 1990, Saddam Hussein's Iraqi government Iraqi invasion of Kuwait, invaded Kuwait; Gorbachev endorsed President Bush's condemnation of it. This brought criticism from many in the Soviet state apparatus, who saw Hussein as a key ally in the Persian Gulf and feared for the safety of the 9,000 Soviet citizens in Iraq, although Gorbachev argued that the Iraqis were the clear aggressors. In November the Soviets endorsed United Nations Security Council Resolution 660, a UN Resolution permitting force to be used in expelling the Iraqi Army from Kuwait. Gorbachev later called it a "watershed" in world politics, "the first time the superpowers acted together in a regional crisis". However, when the US announced plans for Gulf War, a ground invasion, Gorbachev opposed it, urging instead a peaceful solution. In October 1990, Gorbachev was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize

The Nobel Peace Prize (Swedish language, Swedish and ) is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the Will and testament, will of Sweden, Swedish industrialist, inventor, and armaments manufacturer Alfred Nobel, along with the prizes in Nobe ...

; he was flattered but acknowledged "mixed feelings" about the accolade. Polls indicated that 90% of Soviet citizens disapproved of the award, widely seen as an anti-Soviet accolade.

With the Soviet budget deficit climbing and no domestic money markets to provide the state with loans, Gorbachev looked elsewhere. Throughout 1991, Gorbachev requested sizable loans from Western countries and Japan, hoping to keep the Soviet economy afloat and ensure the success of perestroika. Although the Soviet Union had been excluded from the G7, Gorbachev secured an invitation to 17th G7 summit, its London summit in July 1991. There, he continued to call for financial assistance; Mitterrand and Kohl backed him, while Thatcher—no longer in office—urged Western leaders to agree. Most G7 members were reluctant, instead offering technical assistance and proposing the Soviets receive "special associate" status—rather than full membership—of the World Bank and International Monetary Fund. Gorbachev was frustrated that the US would spend $100 billion on the Gulf War but would not offer his country loans. Other countries were more forthcoming; West Germany had given the Soviets Deutsche Mark, DM60 billion by mid-1991. Bush visited Moscow in late July, when he and Gorbachev concluded ten years of negotiations by signing the START I treaty, a bilateral agreement on the reduction and limitation of strategic offensive arms.

August coup and government crises

At the 28th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, 28th Communist Party Congress in July 1990, hardliners criticized the reformists, but Gorbachev was re-elected party leader. Seeking compromise with the liberalizers, Gorbachev assembled a team of his own and Yeltsin's advisers to come up with an economic reform package: the result was the "500 Days" programme. This called for further decentralization and some privatization. In September, Yeltsin presented the plan to the Russian Supreme Soviet, which backed it. Many in the Communist Party and state apparatus warned against it, and it was abandoned.

By mid-November 1990, much of the press was calling for Gorbachev to resign and predicting civil war. In November, he announced an eight-point program with governmental reforms, among them the abolition of the presidential council. By this point, Gorbachev was isolated from many of his former close allies and aides. Yakovlev had moved out of his inner circle and Shevardnadze had resigned.

Amid growing dissent in the Baltics, in January 1991 Gorbachev demanded that the Lithuanian Supreme Council rescind its pro-independence reforms. Soviet troops occupied buildings in Vilnius and January Events, attacked protesters,

At the 28th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, 28th Communist Party Congress in July 1990, hardliners criticized the reformists, but Gorbachev was re-elected party leader. Seeking compromise with the liberalizers, Gorbachev assembled a team of his own and Yeltsin's advisers to come up with an economic reform package: the result was the "500 Days" programme. This called for further decentralization and some privatization. In September, Yeltsin presented the plan to the Russian Supreme Soviet, which backed it. Many in the Communist Party and state apparatus warned against it, and it was abandoned.

By mid-November 1990, much of the press was calling for Gorbachev to resign and predicting civil war. In November, he announced an eight-point program with governmental reforms, among them the abolition of the presidential council. By this point, Gorbachev was isolated from many of his former close allies and aides. Yakovlev had moved out of his inner circle and Shevardnadze had resigned.

Amid growing dissent in the Baltics, in January 1991 Gorbachev demanded that the Lithuanian Supreme Council rescind its pro-independence reforms. Soviet troops occupied buildings in Vilnius and January Events, attacked protesters, In August, Gorbachev holidayed at his dacha in Foros, Crimea. Two weeks into his holiday, a group of senior Communist Party figures—the "Gang of Eight (Soviet Union), Gang of Eight" launched a 1991 Soviet coup d'état attempt, coup d'état. The coup leaders demanded that Gorbachev declare a state of emergency, but he refused. He was kept under house arrest in the dacha. The coup plotters publicly announced that Gorbachev was ill and thus Vice President Yanayev would take charge of the country.

Yeltsin entered the Moscow White House (Moscow), White House. Protesters prevented troops storming the building to arrest him. In front of the White House, Yeltsin, atop a tank, gave a memorable speech condemning the coup. The coup's leaders realized that they lacked sufficient support and ended their efforts. Gorbachev returned to Moscow and thanked Yeltsin. Two days later, he resigned as general secretary.

In August, Gorbachev holidayed at his dacha in Foros, Crimea. Two weeks into his holiday, a group of senior Communist Party figures—the "Gang of Eight (Soviet Union), Gang of Eight" launched a 1991 Soviet coup d'état attempt, coup d'état. The coup leaders demanded that Gorbachev declare a state of emergency, but he refused. He was kept under house arrest in the dacha. The coup plotters publicly announced that Gorbachev was ill and thus Vice President Yanayev would take charge of the country.

Yeltsin entered the Moscow White House (Moscow), White House. Protesters prevented troops storming the building to arrest him. In front of the White House, Yeltsin, atop a tank, gave a memorable speech condemning the coup. The coup's leaders realized that they lacked sufficient support and ended their efforts. Gorbachev returned to Moscow and thanked Yeltsin. Two days later, he resigned as general secretary.

Final days and collapse

After the coup, the Supreme Soviet indefinitely suspended all Communist Party activity, effectively ending communist rule in the Soviet Union. On 30 October, Gorbachev attended Madrid Conference of 1991, a conference in Madrid trying to revive the Israeli–Palestinian peace process. The event was co-sponsored by the US and Soviet Union. There, he again met with Bush. En route home, he traveled to France where he stayed with Mitterrand at the latter's home near Bayonne.

To maintain unity, Gorbachev continued to plan for a union treaty, but met opposition to the continuation of a federal state as the leaders of several Soviet republics bowed to nationalist pressure. Yeltsin stated that he would veto any idea of a unified state, instead favoring a confederation with little central authority. Only the leaders of Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic, Kazakhstan and Kirghiz Soviet Socialist Republic, Kirghizia supported Gorbachev's approach. The 1991 Ukrainian independence referendum, referendum in Ukraine on 1 December with a 90% turnout for secession from the Union was a fatal blow; Gorbachev had expected Ukrainians to reject independence.

On 30 October, Gorbachev attended Madrid Conference of 1991, a conference in Madrid trying to revive the Israeli–Palestinian peace process. The event was co-sponsored by the US and Soviet Union. There, he again met with Bush. En route home, he traveled to France where he stayed with Mitterrand at the latter's home near Bayonne.

To maintain unity, Gorbachev continued to plan for a union treaty, but met opposition to the continuation of a federal state as the leaders of several Soviet republics bowed to nationalist pressure. Yeltsin stated that he would veto any idea of a unified state, instead favoring a confederation with little central authority. Only the leaders of Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic, Kazakhstan and Kirghiz Soviet Socialist Republic, Kirghizia supported Gorbachev's approach. The 1991 Ukrainian independence referendum, referendum in Ukraine on 1 December with a 90% turnout for secession from the Union was a fatal blow; Gorbachev had expected Ukrainians to reject independence.

Without Gorbachev's knowledge, Yeltsin met with Ukrainian president Leonid Kravchuk and Belarusian president Stanislav Shushkevich in Belovezha Forest, near Brest, Belarus, on 8 December and signed the Belavezha Accords, which declared the Soviet Union had ceased to exist and formed the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) as its successor. Gorbachev only learned of this development when Shushkevich phoned him; Gorbachev was furious. He desperately looked for an opportunity to preserve the Soviet Union, hoping that the media and intelligentsia would rally against its dissolution. Ukrainian, Belarusian, and Russian Supreme Soviets then ratified the establishment of the CIS. On 9 December, Gorbachev issued a statement calling the CIS agreement "illegal and dangerous". On 20 December, the leaders of 11 of the 12 remaining republics—all except Georgia—met in Kazakhstan and signed the Alma-Ata Protocol, agreeing to dismantle the Soviet Union and formally establish the CIS. They provisionally accepted Gorbachev's resignation as president of what remained of the Soviet Union. Accepting the ''fait accompli'', Gorbachev said he would resign as soon as he saw that the CIS was a reality.

Gorbachev reached a deal with Yeltsin that called for Gorbachev to announce his resignation as Soviet president and Commander-in-Chief on 25 December, vacating the Kremlin by 29 December. Yakovlev, Chernyaev and Shevardnadze joined Gorbachev to help him write a resignation speech. Gorbachev gave his speech in the Kremlin in front of television cameras, for international broadcast. In it, he announced, "I hereby discontinue my activities at the post of President of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics." He expressed regret for the breakup of the Soviet Union but cited what he saw as the achievements of his administration: political and religious freedom, the end of totalitarianism, the introduction of democracy and a market economy, and an end to the arms race and Cold War. Gorbachev was the third out of eight Soviet leaders, after Malenkov and Khrushchev, not to die in office. The following day, 26 December, the Soviet of the Republics, the upper house of the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union, voted the country out of existence. As of 31 December 1991, all Soviet institutions that had not been taken over by Russia ceased to function.

Without Gorbachev's knowledge, Yeltsin met with Ukrainian president Leonid Kravchuk and Belarusian president Stanislav Shushkevich in Belovezha Forest, near Brest, Belarus, on 8 December and signed the Belavezha Accords, which declared the Soviet Union had ceased to exist and formed the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) as its successor. Gorbachev only learned of this development when Shushkevich phoned him; Gorbachev was furious. He desperately looked for an opportunity to preserve the Soviet Union, hoping that the media and intelligentsia would rally against its dissolution. Ukrainian, Belarusian, and Russian Supreme Soviets then ratified the establishment of the CIS. On 9 December, Gorbachev issued a statement calling the CIS agreement "illegal and dangerous". On 20 December, the leaders of 11 of the 12 remaining republics—all except Georgia—met in Kazakhstan and signed the Alma-Ata Protocol, agreeing to dismantle the Soviet Union and formally establish the CIS. They provisionally accepted Gorbachev's resignation as president of what remained of the Soviet Union. Accepting the ''fait accompli'', Gorbachev said he would resign as soon as he saw that the CIS was a reality.

Gorbachev reached a deal with Yeltsin that called for Gorbachev to announce his resignation as Soviet president and Commander-in-Chief on 25 December, vacating the Kremlin by 29 December. Yakovlev, Chernyaev and Shevardnadze joined Gorbachev to help him write a resignation speech. Gorbachev gave his speech in the Kremlin in front of television cameras, for international broadcast. In it, he announced, "I hereby discontinue my activities at the post of President of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics." He expressed regret for the breakup of the Soviet Union but cited what he saw as the achievements of his administration: political and religious freedom, the end of totalitarianism, the introduction of democracy and a market economy, and an end to the arms race and Cold War. Gorbachev was the third out of eight Soviet leaders, after Malenkov and Khrushchev, not to die in office. The following day, 26 December, the Soviet of the Republics, the upper house of the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union, voted the country out of existence. As of 31 December 1991, all Soviet institutions that had not been taken over by Russia ceased to function.

Post-USSR life

1991–1999: Initial years

Out of office, he and Raisa initially lived in their dilapidated dacha on Rublevskoe Shosse, and were allowed to privatize their smaller apartment on Kosygin Street. He focused on establishing International Foundation for Socio-Economic and Political Studies, his foundation, launched in March 1992; Yakovlev and Revenko were its first vice presidents. Its initial tasks were analyzing and publishing material on the history of perestroika, and defending the policy. The foundation tasked itself with monitoring and critiquing life in post-Soviet Russia, presenting alternative development forms to Yeltsin's.

To finance his foundation, Gorbachev began lecturing internationally, charging large fees. On a visit to Japan, he was given multiple honorary degrees. In 1992, he toured the US in a Forbes private jet to raise money for his foundation, meeting the Reagans for a social visit. From there he went to Spain, where he met with his friend Prime Minister Felipe González. He further visited Israel and Germany, where he was received warmly for his role in facilitating

Out of office, he and Raisa initially lived in their dilapidated dacha on Rublevskoe Shosse, and were allowed to privatize their smaller apartment on Kosygin Street. He focused on establishing International Foundation for Socio-Economic and Political Studies, his foundation, launched in March 1992; Yakovlev and Revenko were its first vice presidents. Its initial tasks were analyzing and publishing material on the history of perestroika, and defending the policy. The foundation tasked itself with monitoring and critiquing life in post-Soviet Russia, presenting alternative development forms to Yeltsin's.

To finance his foundation, Gorbachev began lecturing internationally, charging large fees. On a visit to Japan, he was given multiple honorary degrees. In 1992, he toured the US in a Forbes private jet to raise money for his foundation, meeting the Reagans for a social visit. From there he went to Spain, where he met with his friend Prime Minister Felipe González. He further visited Israel and Germany, where he was received warmly for his role in facilitating German reunification

German reunification () was the process of re-establishing Germany as a single sovereign state, which began on 9 November 1989 and culminated on 3 October 1990 with the dissolution of the East Germany, German Democratic Republic and the int ...

. To supplement his lecture fees and book sales, Gorbachev appeared in television commercials and photograph advertisements, enabling him to keep the foundation afloat. With his wife's assistance, he worked on his memoirs, which were published in Russian in 1995 and in English the following year. He began writing a monthly syndicated column for ''The New York Times''.