Golden Spike (other) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The golden spike (also known as the last spike) is the ceremonial 17.6-

The golden spike (also known as the last spike) is the ceremonial 17.6-

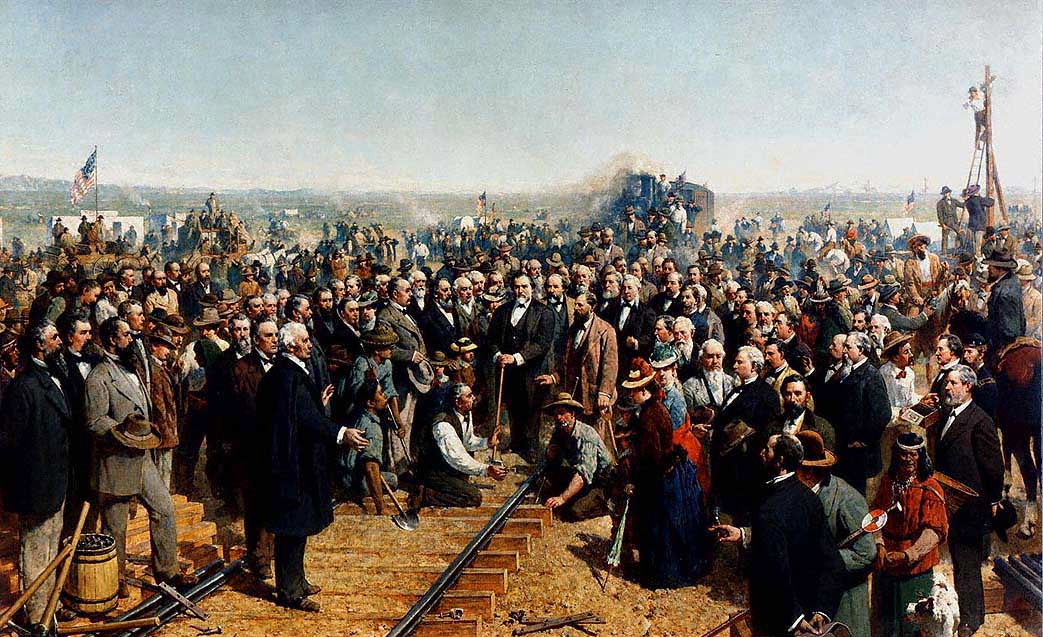

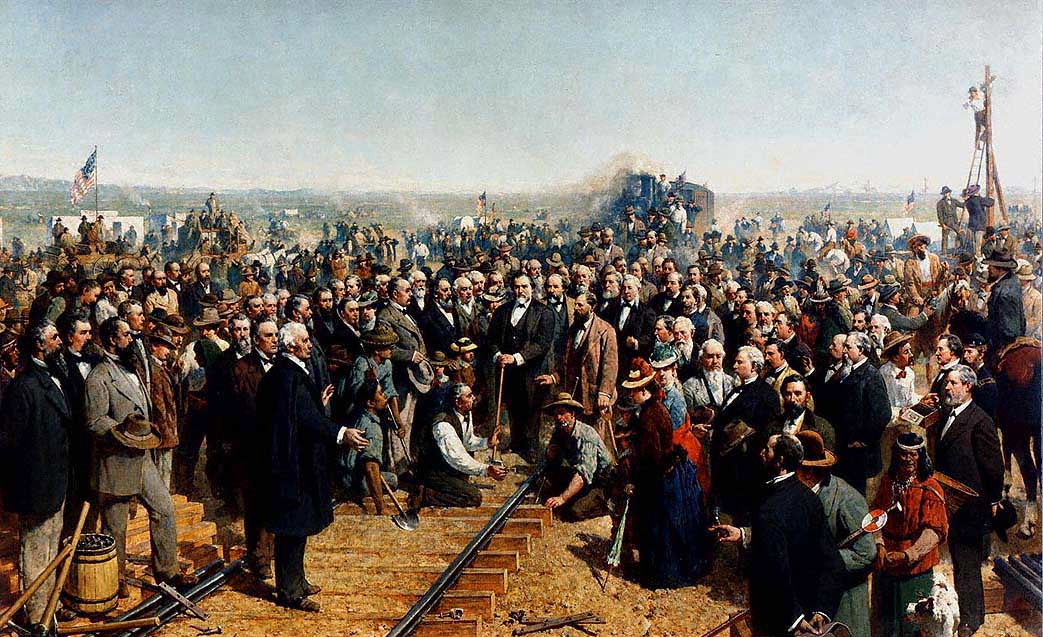

"Driving the Last Spike at Promontory, 1869"

''California Historical Society Quarterly'', Vol. XXXVI, No. 2, June 1957, pp. 96–106, and Vol. XXXVI, No. 3, September 1957, pp. 263–274. The spike was manufactured in 1869 especially for the May event by the William T. Garratt Foundry in San Francisco. Two of the sides were engraved with the names of the railroad officers and directors. A special On May 10, in anticipation of the ceremony,

On May 10, in anticipation of the ceremony,

In 1942, the old rails over Promontory Summit were salvaged for the

In 1942, the old rails over Promontory Summit were salvaged for the  It remains a common myth that Chinese workers are not visible in the famous Andrew J. Russell "champagne photograph" of the last spike ceremony. Many Chinese workers were absent from the Golden Spike ceremony in 1869 despite their tremendous contribution in the completion of the railroad. More than 12,000 Chinese had labored to build the rail line from the west, 80% of the railroad workers were Chinese.

On the 145th anniversary of the Golden Spike ceremony,

It remains a common myth that Chinese workers are not visible in the famous Andrew J. Russell "champagne photograph" of the last spike ceremony. Many Chinese workers were absent from the Golden Spike ceremony in 1869 despite their tremendous contribution in the completion of the railroad. More than 12,000 Chinese had labored to build the rail line from the west, 80% of the railroad workers were Chinese.

On the 145th anniversary of the Golden Spike ceremony,  Three of the Chinese workers who helped build the railroad in 1869, Wong Fook, Lee Chao, and Ging Cui were given a place in the celebratory 50th anniversary parade at

Three of the Chinese workers who helped build the railroad in 1869, Wong Fook, Lee Chao, and Ging Cui were given a place in the celebratory 50th anniversary parade at

File:CP steam loco.jpg, A replica of the ''Jupiter'' (CP# 60) at the

An elaborate four-day event called the Golden Spike Days Celebration was held in Omaha, Nebraska, from April 26 to 29, 1939, to commemorate the 70th anniversary of the joining of the UP and CPRR rails and driving of the Last Spike at Promontory Summit, Utah, in 1869. The centerpiece event of the celebration occurred on April 28 with the

An elaborate four-day event called the Golden Spike Days Celebration was held in Omaha, Nebraska, from April 26 to 29, 1939, to commemorate the 70th anniversary of the joining of the UP and CPRR rails and driving of the Last Spike at Promontory Summit, Utah, in 1869. The centerpiece event of the celebration occurred on April 28 with the

V&T No. 22 ''"INYO"''

Nevada State Railroad Museum

Golden Spike National Historic Monument

* ttps://goldenspiketower.com/ Golden Spike Tower and Visitors Center (Nebraska) {{DEFAULTSORT:Golden Spike First transcontinental railroad 1869 in the United States Box Elder County, Utah American frontier Gold objects History of the American West History of California History of Nevada History of Utah Union Pacific Railroad Utah Territory 1869 in rail transport 1869 in Utah Territory es:Primer ferrocarril transcontinental de Estados Unidos#Golden Spike

The golden spike (also known as the last spike) is the ceremonial 17.6-

The golden spike (also known as the last spike) is the ceremonial 17.6-karat

The fineness of a precious metal object (coin, bar, jewelry, etc.) represents the weight of ''fine metal'' therein, in proportion to the total weight which includes alloying base metals and any impurities. Alloy metals are added to increase hardn ...

gold final spike

Spike, spikes, or spiking may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media

Books

* ''The Spike'' (novel), a novel by Arnaud de Borchgrave

* ''The Spike'' (Broderick book), a nonfiction book by Damien Broderick

* ''The Spike'', a starship in Peter ...

driven by Leland Stanford

Amasa Leland Stanford (March 9, 1824June 21, 1893) was an American attorney, industrialist, philanthropist, and Republican Party (United States), Republican Party politician from Watervliet, New York. He served as the eighth governor of Calif ...

to join the rails of the first transcontinental railroad

America's first transcontinental railroad (known originally as the "Pacific Railroad" and later as the "Overland Route (Union Pacific Railroad), Overland Route") was a continuous railroad line built between 1863 and 1869 that connected the exis ...

across the United States connecting the Central Pacific Railroad

The Central Pacific Railroad (CPRR) was a rail company chartered by U.S. Congress in 1862 to build a railroad eastwards from Sacramento, California, to complete most of the western part of the "First transcontinental railroad" in North Americ ...

from Sacramento

Sacramento ( or ; ; ) is the capital city of the U.S. state of California and the seat of Sacramento County. Located at the confluence of the Sacramento and American Rivers in Northern California's Sacramento Valley, Sacramento's 2020 p ...

and the Union Pacific Railroad

The Union Pacific Railroad is a Railroad classes, Class I freight-hauling railroad that operates 8,300 locomotives over routes in 23 U.S. states west of Chicago and New Orleans. Union Pacific is the second largest railroad in the United Stat ...

from Omaha

Omaha ( ) is the List of cities in Nebraska, most populous city in the U.S. state of Nebraska. It is located in the Midwestern United States along the Missouri River, about north of the mouth of the Platte River. The nation's List of United S ...

on May 10, 1869, at Promontory Summit, Utah Territory

Promontory is an area of high ground in Box Elder County, Utah, United States, 32 mi (51 km) west of Brigham City and 66 mi (106 km) northwest of Salt Lake City. Rising to an elevation of 4,902 feet (1,494 m) above s ...

. The term ''last spike'' has been used to refer to one driven at the usually ceremonial completion of any new railroad construction projects, particularly those in which construction is undertaken from two disparate origins toward a common meeting point. The spike is now displayed in the Cantor Arts Center

Cantor Arts Center (officially Iris and B. Gerald Cantor Center for Visual Arts at Stanford University, previously the Stanford University Museum of Art) is an art museum on the campus of Stanford University in Stanford, California, United State ...

at Stanford University

Leland Stanford Junior University, commonly referred to as Stanford University, is a Private university, private research university in Stanford, California, United States. It was founded in 1885 by railroad magnate Leland Stanford (the eighth ...

.

History

Completing the last link in the transcontinental railroad with a spike of gold was the brainchild ofDavid Hewes

David Hewes (May 16, 1822 in Lynnfield, Massachusetts – July 23, 1915 in Orange, California), was an American born into one of the "old families" of Massachusetts that could be traced back seven generations to the patriot Joshua Hewes. Hewes ...

, a San Francisco

San Francisco, officially the City and County of San Francisco, is a commercial, Financial District, San Francisco, financial, and Culture of San Francisco, cultural center of Northern California. With a population of 827,526 residents as of ...

financier and contractor.Bowman, J.N"Driving the Last Spike at Promontory, 1869"

''California Historical Society Quarterly'', Vol. XXXVI, No. 2, June 1957, pp. 96–106, and Vol. XXXVI, No. 3, September 1957, pp. 263–274. The spike was manufactured in 1869 especially for the May event by the William T. Garratt Foundry in San Francisco. Two of the sides were engraved with the names of the railroad officers and directors. A special

tie

Tie has two principal meanings:

* Tie (draw), a finish to a competition with identical results, particularly sports

* Necktie, a long piece of cloth worn around the neck or shoulders

Tie or TIE may also refer to:

Engineering and technology

* T ...

of polished California laurel was chosen to complete the line where the spike would be driven. The ceremony was planned to be held on May 8 (the date engraved on the spike), but it was postponed two days because of bad weather and a labor dispute that delayed the arrival of the Union Pacific side of the rail line.

On May 10, in anticipation of the ceremony,

On May 10, in anticipation of the ceremony, Union Pacific No. 119

Union Pacific No. 119 was a 4-4-0 American type steam locomotive made famous for meeting the Central Pacific Railroad's ''Jupiter'' at Promontory Summit, Utah, during the Golden Spike ceremony commemorating the completion of the first transcontin ...

and Central Pacific No. 60 (better known as the ''Jupiter

Jupiter is the fifth planet from the Sun and the List of Solar System objects by size, largest in the Solar System. It is a gas giant with a Jupiter mass, mass more than 2.5 times that of all the other planets in the Solar System combined a ...

'') locomotives were drawn up face-to-face on Promontory Summit. How many people attended the event is unknown; estimates run from as few as 500 to as many as 3,000; government and railroad officials and track workers were present to witness the event.

Before the last spike was driven, three other commemorative spikes, presented on behalf of the three other members of the Central Pacific's Big Four who did not attend the ceremony, had been driven into their places in a pre-bored laurel tie:

* a second, lower-quality gold spike, supplied by the San Francisco ''News Letter'', was made of what in 1869 was $200 worth of gold and inscribed: ''With this spike the San Francisco News Letter offers its homage to the great work which has joined the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans.''

* a silver spike, supplied by the State of Nevada

Nevada ( ; ) is a landlocked state in the Western United States. It borders Oregon to the northwest, Idaho to the northeast, California to the west, Arizona to the southeast, and Utah to the east. Nevada is the seventh-most extensive, th ...

; forged, rather than cast, of of unpolished silver

* a blended iron, silver, and gold spike, supplied by the Arizona Territory

The Territory of Arizona, commonly known as the Arizona Territory, was a territory of the United States that existed from February 24, 1863, until February 14, 1912, when the remaining extent of the territory was admitted to the Union as the ...

, engraved: ''Ribbed with iron clad in silver and crowned with gold Arizona presents her offering to the enterprise that has banded a continent and dictated a pathway to commerce.'' This spike was given to Union Pacific president, Oliver Ames, following the ceremony. The spike was donated to the Museum of the City of New York

The Museum of the City of New York (MCNY) is a history and art museum in Manhattan, New York City, New York. It was founded by Henry Collins Brown, in 1923Beard, Rick. "Museum of the City of New York" in to preserve and present the history ...

in 1943, by a descendant of Sidney Dillon

Sidney Dillon (May 7, 1812 – June 9, 1892) was an American railroad executive and one of the US's premier railroad builders.

Early life

Dillon was born in Northampton, Fulton County, New York. His father, Timothy, was a farmer.

Career

Sidney ...

. It was, for a time, on display at the Union Pacific Railroad Museum

The Union Pacific Railroad is a Class I freight-hauling railroad that operates 8,300 locomotives over routes in 23 U.S. states west of Chicago and New Orleans. Union Pacific is the second largest railroad in the United States after BNSF, wi ...

in Council Bluffs, Iowa. The Museum of the city of New York sold the spike in January 2023, via auction, to benefit other items in its collection. The winning bid totaled million

The golden spike was made of 17.6-karat

The fineness of a precious metal object (coin, bar, jewelry, etc.) represents the weight of ''fine metal'' therein, in proportion to the total weight which includes alloying base metals and any impurities. Alloy metals are added to increase hardn ...

(73%) copper-alloyed gold, and weighed . It was dropped into a drilled hole in the ceremonial last tie and gently tapped into place with a ceremonial silver spike maul

A spike maul is a hand tool used to drive railroad spikes in railroad track work. It is also known as a spiking hammer.

Description

Spike mauls are akin to sledge hammers, typically weighing from with handles long.

They have elongated doubl ...

. The golden spike was engraved on all four sides:

* ''The Pacific Railroad ground broken January 8, 1863, and completed May 8, 1869''

* ''Directors of the C. P. R. R. of Cal. Hon. Leland Stanford. C. P. Huntington. E. B. Crocker. Mark Hopkins. A. P. Stanford. E. H. Miller Jr.''

* ''Officers. Hon. Leland Stanford. Presdt. C. P. Huntington Vice Presdt. E. B. Crocker. Atty. Mark Hopkins. Tresr. Chas Crocker Gen. Supdt. E. H. Miller Jr. Secty. S. S. Montague. Chief Engr.''

* ''May God continue the unity of our Country, as this Railroad unites the two great Oceans of the world. Presented by David Hewes San Francisco.''

The original golden spike was removed immediately after being hammered in, to prevent it from being stolen.

A duplicate golden spike, exactly like the one used in the ceremony (except for the date), was cast at the same time, but engraved at a later time and bearing the correct Promontory date of May 10, 1869. It has been noted that the first Golden Spike engraving appeared "rushed". The duplicate golden spike, the Hewes family spike, bears lettering that appeared more polished. Unknown to the public, the duplicate golden spike was held by the Hewes family until 2005 and it is now on permanent display, along with Thomas Hill's famous painting ''The Last Spike'', at the California State Railroad Museum

The California State Railroad Museum is a museum in the California State Parks system that interprets the role of railroads in the Western U.S. It is located in Old Sacramento State Historic Park at 111 I Street, Sacramento, California.

Featu ...

in Sacramento.

With the locomotives drawn so near, the crowd pressed so closely around Stanford and the other railroad officials that the ceremony became somewhat disorganized, leading to varying accounts of the events. ''On the Union Pacific side, thrusting westward, the last two rails were laid by Irishmen; on the Central Pacific side, thrusting eastward, the last two rails were laid by the Chinese!'' A. J. Russell stereoview No. 539 photograph shows the "Chinese at Laying Last Rail UPRR". Eight Chinese workers laid the last rail, and three of these men, Ging Cui, Wong Fook, and Lee Shao, lived long enough to participate in the 50th anniversary parade. At the conclusion of the ceremony, the participating Chinese workers were honored and cheered by the CPRR officials and that road's construction chief, J. H. Strobridge, at a dinner in his private railroad car.

To drive the final spike, Stanford lifted a silver spike maul and drove the spike into the tie, completing the line. Stanford and Hewes missed the spike, but the single word "done" was nevertheless flashed by telegraph around the country. In the United States, the event has come to be considered one of the first nationwide media event

A media event, also known as a pseudo-event, is an event, activity, or experience conducted for the purpose of creating media publicity. It may also be any event that is covered in the mass media or was hosted largely with the media in mind.

Etym ...

s. The locomotives were moved forward until their cowcatcher

A cowcatcher, also known as a pilot, is the device mounted at the front of a locomotive to deflect obstacles on the track that might otherwise damage or Derailment, derail it or the train.

In the UK, small metal bars called ''life-guards'', ...

s met, and photographs were taken. Immediately afterward, the golden spike and the laurel tie were removed, lest they be stolen. They were replaced with a regular iron spike and normal railroad tie. At exactly 12:47 pm, the last iron spike was driven, finally completing the line.

After the ceremony, the Golden Spike used in the ceremony was donated to the Stanford Museum

Cantor Arts Center (officially Iris and B. Gerald Cantor Center for Visual Arts at Stanford University, previously the Stanford University Museum of Art) is an art museum on the campus of Stanford University in Stanford, California, United State ...

(now Cantor Arts Center

Cantor Arts Center (officially Iris and B. Gerald Cantor Center for Visual Arts at Stanford University, previously the Stanford University Museum of Art) is an art museum on the campus of Stanford University in Stanford, California, United State ...

) in 1898. The ceremonial laurel tie was destroyed in the fires caused by the 1906 San Francisco earthquake

At 05:12 AM Pacific Time Zone, Pacific Standard Time on Wednesday, April 18, 1906, the coast of Northern California was struck by a major earthquake with an estimated Moment magnitude scale, moment magnitude of 7.9 and a maximum Mercalli inte ...

. A replica of the laurel tie, dedicated in late 2024, is on display in the Gravity Car Barn Museum on Mount Tamalpais

Mount Tamalpais (; ; Miwok languages, Miwok: ''Támal Pájiṣ''), known locally as Mount Tam, is a mountain, peak in Marin County, California, Marin County, California, United States, often considered symbolic of Marin County. Much of Mount Tama ...

.

Aftermath

Although the Promontory event marked the completion of the transcontinental railroad from Omaha to Sacramento on May 10, 1869, it did not mark the completion of the Pacific Railroad "from the Missouri river to the Pacific" authorized by thePacific Railroad Acts

The Pacific Railroad Acts of 1862 were a series of acts of Congress that promoted the construction of a "transcontinental railroad" (the Pacific Railroad) in the United States through authorizing the issuance of government bonds and the grants ...

, much less a seamless coast-to-coast rail network: neither Sacramento nor Omaha was a seaport, nor did they have rail connections until after they were designated as the termini. Western Pacific completed the westernmost transcontinental leg from Sacramento to San Francisco Bay on September 6, 1869, with the last spike at the Mossdale bridge

Mossdale Bridge or Mossdale Railroad Bridge is a vertical-lift bridge, vertical-lift railway bridge spanning the San Joaquin River in the city of Lathrop, California. The original Mossdale swing bridge, completed by Western Pacific Railroad (1862 ...

across the San Joaquin River

The San Joaquin River ( ; ) is the longest river of Central California. The long river starts in the high Sierra Nevada and flows through the rich agricultural region of the northern San Joaquin Valley before reaching Suisun Bay, San Francis ...

near Lathrop, California

Lathrop (, ) is a city located south of Stockton in San Joaquin County, California, United States. The 2020 census reported that Lathrop's population was 28,701. The city is located in Northern California at the intersection of Interstate 5 ...

. The official completion date of the Pacific Railroad as called for by Section 6 of the Pacific Railroad Act of 1862, et seq. was determined to be November 6, 1869, by the U.S. Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that turn on question ...

in Part I of the Court ''Opinion and Order'' dated January 27, 1879, in re ''Union Pacific Railroad vs. United States'' (99 U.S. 402).

Passengers were required to cross the Missouri River

The Missouri River is a river in the Central United States, Central and Mountain states, Mountain West regions of the United States. The nation's longest, it rises in the eastern Centennial Mountains of the Bitterroot Range of the Rocky Moun ...

between Council Bluffs, Iowa

Council Bluffs is a city in and the county seat of Pottawattamie County, Iowa, Pottawattamie County, Iowa, United States. The population was 62,799 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, making it the state's List of cities in Iowa, te ...

, and Omaha, Nebraska

Omaha ( ) is the List of cities in Nebraska, most populous city in the U.S. state of Nebraska. It is located in the Midwestern United States along the Missouri River, about north of the mouth of the Platte River. The nation's List of United S ...

, by boat until the building of the Union Pacific Missouri River Bridge

The Union Pacific Missouri River Bridge is a rail truss bridge across the Missouri River between Council Bluffs, Iowa, and Omaha, Nebraska.

History

When the first railroad bridge on the site opened on March 27, 1872, it connected the First tra ...

in March 1872. In the meantime, a coast-to-coast rail link was achieved in August 1870 in Strasburg, Colorado

Strasburg is an unincorporated town located east of downtown Denver along the I-70 corridor. It is home to Strasburg School District 31-J, and there are several small businesses, medical clinics, and a post office. Strasburg is a census-designa ...

, by the completion of the Denver

Denver ( ) is a List of municipalities in Colorado#Consolidated city and county, consolidated city and county, the List of capitals in the United States, capital and List of municipalities in Colorado, most populous city of the U.S. state of ...

extension of the Kansas Pacific Railway

The Kansas Pacific Railway (KP) was a historic railroad company that operated in the western United States in the late 19th century. It was a federally chartered railroad, backed with government land grants. At a time when the first transcontin ...

.

In 1904, a new railroad route called the Lucin Cutoff

The Lucin Cutoff is a railroad line in Utah, United States that runs from Ogden to its namesake in Lucin. The most prominent feature of the cutoff was a railroad trestle crossing the Great Salt Lake, which was in use from 1904 until the l ...

was built by-passing the Promontory location to the south. By going west across the Great Salt Lake from Ogden, Utah, to Lucin, Utah, the new railroad line shortened the distance by 43 miles and avoided curves and grades. Main line trains no longer passed over Promontory Summit.

In 1942, the old rails over Promontory Summit were salvaged for the

In 1942, the old rails over Promontory Summit were salvaged for the war

War is an armed conflict between the armed forces of states, or between governmental forces and armed groups that are organized under a certain command structure and have the capacity to sustain military operations, or between such organi ...

effort; the event was marked by a ceremonial "undriving" of the last iron spike. The original event had been all but forgotten except by local residents, who erected a commemorative marker in 1943. The following year a commemorative postage stamp was issued to mark the 75th anniversary. The years after the war saw a revival of interest in the event; the first re-enactment was staged in 1948.

In 1957, Congress established the Golden Spike National Historic Site

Golden Spike National Historical Park is a United States National Historical Park located at Promontory Summit, north of the Great Salt Lake in east-central Box Elder County, Utah, United States. The nearest city is Corinne, approximately ...

to preserve the area around Promontory Summit as closely as possible to its appearance in 1869. O'Connor Engineering Laboratories in Costa Mesa, California, designed and built working replicas of the locomotives present at the original ceremony for the Park Service. These engines are drawn up face-to-face each Saturday during the summer for a re-enactment of the event.

For the May 10, 1969, centennial of the driving of the last spike, the High Iron Company ran a steam-powered excursion train round trip from New York City to Promontory. The Golden Spike Centennial Limited transported more than 100 passengers including, for the last leg into Salt Lake City, actor John Wayne

Marion Robert Morrison (May 26, 1907 – June 11, 1979), known professionally as John Wayne, was an American actor. Nicknamed "Duke", he became a Pop icon, popular icon through his starring roles in films which were produced during Hollywood' ...

. The Union Pacific Railroad also sent a special display train and the U.S. Army Transportation Corps sent a steam-powered 3-car special from Fort Eustis

Fort Eustis is a United States Army installation in Newport News, Virginia. In 2010, it was combined with nearby Langley Air Force Base to form Joint Base Langley–Eustis.

The post is the home to the United States Army Training and Doctrin ...

, Virginia.

On May 10, 2006, on the anniversary of the driving of the spike, Utah announced that its state quarter design would be a depiction of the driving of the spike. The Golden Spike design was selected as the winner from among several others by Utah's governor, Jon Huntsman Jr.

Jon Meade Huntsman Jr. (born March 26, 1960) is an American politician, businessman, and diplomat who served as the 16th governor of Utah from 2005 to 2009. A member of the Republican Party, he served as the ambassador of the United States ...

, following a period during which Utah residents voted and commented on their favorite of three finalists.

On May 10, 2019, the United States Postal Service issued a set of three new commemorative postage stamps to mark the 150th anniversary of the driving of the golden spike: one stamp for the Jupiter locomotive, one stamp for locomotive #119, and one stamp for the golden spike.

It remains a common myth that Chinese workers are not visible in the famous Andrew J. Russell "champagne photograph" of the last spike ceremony. Many Chinese workers were absent from the Golden Spike ceremony in 1869 despite their tremendous contribution in the completion of the railroad. More than 12,000 Chinese had labored to build the rail line from the west, 80% of the railroad workers were Chinese.

On the 145th anniversary of the Golden Spike ceremony,

It remains a common myth that Chinese workers are not visible in the famous Andrew J. Russell "champagne photograph" of the last spike ceremony. Many Chinese workers were absent from the Golden Spike ceremony in 1869 despite their tremendous contribution in the completion of the railroad. More than 12,000 Chinese had labored to build the rail line from the west, 80% of the railroad workers were Chinese.

On the 145th anniversary of the Golden Spike ceremony, Corky Lee

Young Corky Lee (September 5, 1947 – January 27, 2021) was a Chinese-American activist, community organizer, photographer, journalist, and the self-proclaimed unofficial Asian American Photographer Laureate. He called himself an "ABC from NYC ...

gathered more than 200 Chinese, Chinese Americans and other Asian Pacific American groups to create what he called "photographic justice".

Research conducted by the Stanford University

Leland Stanford Junior University, commonly referred to as Stanford University, is a Private university, private research university in Stanford, California, United States. It was founded in 1885 by railroad magnate Leland Stanford (the eighth ...

"Chinese Railroad Workers in North America Project" disproved the myth, identifying two Chinese laborers who were photographed in the famous Andrew J. Russell photograph. More Chinese laborers who attended the last spike ceremony are visible in Russell's "stereo view # 539 Chinese at Laying Last Rail UPRR", although the Chinese laborers who attended the ceremony only represented a small fraction of the total Chinese workforce on the railroad.

Three of the Chinese workers who helped build the railroad in 1869, Wong Fook, Lee Chao, and Ging Cui were given a place in the celebratory 50th anniversary parade at

Three of the Chinese workers who helped build the railroad in 1869, Wong Fook, Lee Chao, and Ging Cui were given a place in the celebratory 50th anniversary parade at Ogden, Utah

Ogden ( ) is a city in and the county seat of Weber County, Utah, Weber County, Utah, United States, approximately east of the Great Salt Lake and north of Salt Lake City. The population was 87,321 in 2020, according to the United States Census ...

, in 1919. However, during the 1969 ceremony no Chinese representatives spoke during the dedication of a plaque memorializing Chinese railroad workers. The 2019 ceremony brought an intentionally greater focus on the Chinese contribution with then United States Secretary of Transportation

The United States secretary of transportation is the head of the United States Department of Transportation. The secretary serves as the principal advisor to the president of the United States on all matters relating to transportation. The secre ...

Elaine Chao

Elaine Lan Chao (born March 26, 1953) is an American businesswoman and former government official who served as United States secretary of labor in the administration of George W. Bush from 2001 to 2009 and as United States secretary of transpor ...

speaking at the event. The Chinese Railway Workers Descendants Association continues to hold annual gatherings at Chinese Arch near Promontory. A monument dedicated to Chinese workers on the railroad was installed at the Utah State capitol building to correspond with the 155th anniversary.

A Utah state park, planned to celebrate the Golden Spike opening in Brigham City, Utah

Brigham City is a city in Box Elder County, Utah, Box Elder County, Utah, United States. The population was 19,650 at the 2020 United States Census, 2020 census, up from the 2010 figure of 17,899. It is the county seat of Box Elder County. It l ...

in 2025, will feature a 43 feet tall statue depicting the Golden Spike. The statue, mounted on the back of a truck; has toured various parts of America throughout 2023 and 2024.

Golden Spike National Historic Site

Golden Spike National Historical Park is a United States National Historical Park located at Promontory Summit, north of the Great Salt Lake in east-central Box Elder County, Utah, United States. The nearest city is Corinne, approximately ...

File:UP steam loco.jpg, A replica of UP# 119 at Golden Spike National Historic Siter

File:Golden Spike Recreation.jpg, The current site of the Golden Spike National Historic Site, with replicas of No. 119 and the ''Jupiter'' facing each other to re-enact the driving of the Golden Spike

Golden Spike Days Celebration (1939)

An elaborate four-day event called the Golden Spike Days Celebration was held in Omaha, Nebraska, from April 26 to 29, 1939, to commemorate the 70th anniversary of the joining of the UP and CPRR rails and driving of the Last Spike at Promontory Summit, Utah, in 1869. The centerpiece event of the celebration occurred on April 28 with the

An elaborate four-day event called the Golden Spike Days Celebration was held in Omaha, Nebraska, from April 26 to 29, 1939, to commemorate the 70th anniversary of the joining of the UP and CPRR rails and driving of the Last Spike at Promontory Summit, Utah, in 1869. The centerpiece event of the celebration occurred on April 28 with the world premiere

A premiere, also spelled première, (from , ) is the debut (first public presentation) of a work, i.e. play, film, dance, musical composition, or even a performer in that work.

History

Raymond F. Betts attributes the introduction of the film ...

of the Cecil B. DeMille

Cecil Blount DeMille (; August 12, 1881January 21, 1959) was an American filmmaker and actor. Between 1914 and 1958, he made 70 features, both silent and sound films. He is acknowledged as a founding father of American cinema and the most co ...

feature motion picture ''Union Pacific

The Union Pacific Railroad is a Class I freight-hauling railroad that operates 8,300 locomotives over routes in 23 U.S. states west of Chicago and New Orleans. Union Pacific is the second largest railroad in the United States after BNSF, ...

'' that took place simultaneously in the city's Omaha, Orpheum, and Paramount theaters. The film features an elaborate reenactment of the original Golden Spike ceremony (filmed in Canoga Park, California) as the closing scene of the motion picture, for which DeMille borrowed the actual Golden Spike from Stanford University

Leland Stanford Junior University, commonly referred to as Stanford University, is a Private university, private research university in Stanford, California, United States. It was founded in 1885 by railroad magnate Leland Stanford (the eighth ...

to be held by Dr. W. H. Harkness (Stanley Andrews

Stanley Martin Andrews (born Andrzejewski; August 28, 1891 – June 23, 1969) was an American actor perhaps best known as the voice of Daddy Warbucks on the radio program ''Little Orphan Annie'' and later as "The Old Ranger", the first host of ...

) as he delivered his remarks prior to its driving to complete the railroad. (A prop spike was used for the hammering sequence.)

Also included as a part of the overall celebration's major attractions, was the Golden Spike Historical Exposition, a large assemblage of artifacts (including the Golden Spike), tools, equipment, photographs, documents, and other materials from the construction of the Pacific Railroad that were put on display at Omaha's Municipal Auditorium. The four days of events drew more than 250,000 people to Omaha during its run, a number roughly equivalent to the city's then population. The celebration was opened by President Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), also known as FDR, was the 32nd president of the United States, serving from 1933 until his death in 1945. He is the longest-serving U.S. president, and the only one to have served ...

who inaugurated it by pressing a telegraph key at the White House in Washington, D.C.

On the same day as the premiere of the movie, a gold-colored concrete spike called the "Golden Spike Monument", measuring some in height, was unveiled at 21st Street and 9th Avenue in Council Bluffs, Iowa, adjacent to the UP's main yard, the location of milepost 0.0 of that road's portion of the Pacific Railroad

The Pacific Railroad (not to be confused with Union Pacific Railroad) was a railroad based in Missouri. It was a predecessor of both the Missouri Pacific Railroad and St. Louis-San Francisco Railway.

The Pacific was chartered by Missouri in 184 ...

. The concrete spike remains on display at the site.

In popular culture

Artwork

* In 2012, artist Greg Stimac used the original "golden spike", on display at theCantor Arts Center

Cantor Arts Center (officially Iris and B. Gerald Cantor Center for Visual Arts at Stanford University, previously the Stanford University Museum of Art) is an art museum on the campus of Stanford University in Stanford, California, United State ...

at Stanford University

Leland Stanford Junior University, commonly referred to as Stanford University, is a Private university, private research university in Stanford, California, United States. It was founded in 1885 by railroad magnate Leland Stanford (the eighth ...

, to produce a series of photogram

A photogram is a Photography, photographic image made without a camera by placing objects directly onto the surface of a light-sensitive material such as photographic paper and then exposing it to light.

The usual result is a negative shadow im ...

s, or cameraless photographs.

Films

* The first motion picture depiction of the driving of the golden spike occurred in '' The Iron Horse'' (1924), asilent film

A silent film is a film without synchronized recorded sound (or more generally, no audible dialogue). Though silent films convey narrative and emotion visually, various plot elements (such as a setting or era) or key lines of dialogue may, w ...

directed by John Ford

John Martin Feeney (February 1, 1894 – August 31, 1973), better known as John Ford, was an American film director and producer. He is regarded as one of the most important and influential filmmakers during the Golden Age of Hollywood, and w ...

and produced by Fox Film

The Fox Film Corporation (also known as Fox Studios) was an American independent company that produced motion pictures and was formed in 1914 by the theater "chain" pioneer William Fox. It was the corporate successor to his earlier Greater Ne ...

. In 2011, this film was deemed "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant" by the United States Library of Congress

The Library of Congress (LOC) is a research library in Washington, D.C., serving as the library and research service for the United States Congress and the ''de facto'' national library of the United States. It also administers Copyright law o ...

and selected for preservation in the National Film Registry

The National Film Registry (NFR) is the United States National Film Preservation Board's (NFPB) collection of films selected for preservation (library and archival science), preservation, each selected for its cultural, historical, and aestheti ...

.

* In the fictional action comedy film ''Wild Wild West

''Wild Wild West'' is a 1999 American steampunk Western film directed by Barry Sonnenfeld and written by S. S. Wilson and Brent Maddock alongside Jeffrey Price and Peter S. Seaman, based on a story conceived by Jim and John Thomas. Loosely ...

'' (1999), the joining ceremony is the setting of an assassination attempt on then U.S. President Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was the 18th president of the United States, serving from 1869 to 1877. In 1865, as Commanding General of the United States Army, commanding general, Grant led the Uni ...

by the film's antagonist Dr. Arliss Loveless. (In reality Grant did not attend the Golden Spike ceremony.) The extensive Promontory Summit set for the film's Golden Spike ceremony scenes was built at the 20,000-acre Cook's Ranch near Santa Fe, New Mexico.

* In the Western action film "The Lone Ranger

The Lone Ranger is a fictional masked former Texas Ranger who fought outlaws in the American Old West with his Native American friend Tonto. The character has been called an enduring icon of American culture.

He first appeared in 1933 in a ...

" (2013), the joining of two railroads was commenced by the film's antagonist, Latham Cole. However, it was interrupted by the start of a chase. Instead of Union Pacific #119, they used a scratch-built locomotive entitled, Constitution (A locomotive based on Illinois Central 382 that Casey Jones

John Luther "Casey" Jones (March 14, 1864 – April 30, 1900) was an American railroader who was killed when his passenger train collided with a stalled freight train in Vaughan, Mississippi.

Jones was a locomotive engineer for the Illinois Cen ...

drove on his final trip on April 30th, 1900).

Television

* The '' Batman: The Animated Series'' episode "Showdown" features an extended flashback taking place in the Utah Territory in 1883, with the territorial governor (voiced byPatrick Leahy

Patrick Joseph Leahy ( ; born March 31, 1940) is an American politician and attorney who represented Vermont in the United States Senate from 1975 to 2023. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, he also was the pr ...

) presiding over the ceremony to drive home the Golden Spike, before they are interrupted by an aerial attack by Ra's al Ghul

Ra's al Ghul is a supervillain appearing in American comic books published by DC Comics, commonly as an adversary of the superhero Batman. Created by editor Julius Schwartz, writer Dennis O'Neil, and artist Neal Adams, the character first appeared ...

. In reality, 1883 was the year in which the southern section of the Southern Pacific

The Southern Pacific (or Espee from the railroad initials) was an American Class I railroad network that existed from 1865 to 1996 and operated largely in the Western United States. The system was operated by various companies under the names ...

railroad (the ''second'' transcontinental line) was completed; the completion ceremony took place in Texas rather than Utah, and the ceremonial spikes driven were silver, not gold.

* ''Hell on Wheels

Hell on Wheels was the itinerant collection of flimsily assembled gambling houses, dance halls, saloons, and brothels that followed the army of Union Pacific Railroad workers westward as they constructed the first transcontinental railroad in 18 ...

'' presents a multi-season arc on the construction of the transcontinental railroad. In Season 5, Episode 11, a flash forward sequence includes a picture of the railroad ceremony and a main character claiming to possess a ring made of gold crafted from part of the ceremonial golden spike.

* In Syfy original series ''Warehouse 13

''Warehouse 13'' is an American science fiction television series that originally ran from July 7, 2009, to May 19, 2014, on the Syfy network, and was executively produced by Jack Kenny and David Simkins for Universal Cable Productions. Des ...

'', the golden spike is featured as an artifact that was used by Pete & Myka to temporarily negate the effects of the Rhodes Bowl. Later, the spike is depicted as stuck within the Warehouse expansion joints as it expanded to accommodate additional artifacts.

Trains

* The ''Inyo'', a4-4-0

4-4-0, in the Whyte notation, denotes a steam locomotive with a wheel arrangement of four leading wheels on two axles (usually in a leading bogie), four powered and coupled driving wheels on two axles, and no trailing wheels.

First built in the ...

steam locomotive built for the Virginia & Truckee Railroad

The Virginia and Truckee Railroad (stylized as Virginia & Truckee Railroad) is a privately owned heritage railway, heritage railroad, headquartered in Virginia City, Nevada. Its private and publicly owned route is long. When first constructe ...

(V&T #22) in 1875 by the Baldwin Locomotive Works

The Baldwin Locomotive Works (BLW) was an American manufacturer of railway locomotives from 1825 to 1951. Originally located in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, it moved to nearby Eddystone, Pennsylvania, Eddystone in the early 20th century. The com ...

in Philadelphia, appeared in both the Golden Spike ceremony scene in ''Union Pacific

The Union Pacific Railroad is a Class I freight-hauling railroad that operates 8,300 locomotives over routes in 23 U.S. states west of Chicago and New Orleans. Union Pacific is the second largest railroad in the United States after BNSF, ...

'' (1939) and in the 1960s television series ''The Wild Wild West

''The Wild Wild West'' is an American Western (genre), Western, spy film, spy, and science fiction on television, science fiction television series that ran on the CBS television network for four seasons from September 17, 1965, to April 11, 19 ...

''. It appears briefly as the Jupiter in '' Go West''. In May 1969, the ''Inyo'' participated in the Golden Spike Centennial at Promontory, Utah, and then served for ten years as the replica of the Central Pacific's ''Jupiter'' (CPRR #60) at the Golden Spike National Historical Site, until the current replica was built in 1979. Purchased by the Nevada State Railroad Museum

The Nevada State Railroad Museum, located in Carson City, Nevada, preserves the heritage railroad, railroad heritage of Nevada, including locomotives and cars of the famous Virginia and Truckee Railroad. Much of the museum equipment was obtai ...

in Carson City, Nevada, in 1974, it was eventually brought back to Nevada and fully restored there in 1983, where it remains operational.Nevada State Railroad Museum

See also

*Cornerstone

A cornerstone (or foundation stone or setting stone) is the first stone set in the construction of a masonry Foundation (engineering), foundation. All other stones will be set in reference to this stone, thus determining the position of the entir ...

* Last Spike (Canadian Pacific Railway)

* Last Spike Monument (New Zealand)

* List of heritage railroads in the United States

This is a list of heritage railroads in the United States; there are currently no such railroads in two U.S. states, Mississippi and North Dakota.

Heritage railroads by state Alabama

* Heart of Dixie Railroad Museum, Shelby & Southern Railroad ...

References

External links

Golden Spike National Historic Monument

* ttps://goldenspiketower.com/ Golden Spike Tower and Visitors Center (Nebraska) {{DEFAULTSORT:Golden Spike First transcontinental railroad 1869 in the United States Box Elder County, Utah American frontier Gold objects History of the American West History of California History of Nevada History of Utah Union Pacific Railroad Utah Territory 1869 in rail transport 1869 in Utah Territory es:Primer ferrocarril transcontinental de Estados Unidos#Golden Spike