Glorious First of June on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Glorious First of June, also known as the Fourth Battle of Ushant, (known in France as the or ) was fought on 1 June 1794 between the

'' Worcestershire Regiment'', retrieved 23 December 2007The Glorious First of June 1794

, ''Queen's Royal West Surrey Regiment'', retrieved 1 January 2008 Despite these difficulties, the Channel Squadron was possessed of one of the best naval commanders of the age; its commander-in-chief,

''

Although ''Queen Charlotte'' pressed on all sail, she was not the first through the enemy line. That distinction belonged to a ship of the van squadron under Admiral Graves: HMS ''Defence'' under Captain James Gambier, a notoriously dour officer nicknamed "Dismal Jimmy" by his contemporaries. ''Defence'', the seventh ship of the British line, successfully cut the French line between its sixth and seventh ships; ''Mucius'' and ''Tourville''. Raking both opponents, ''Defence'' soon found herself in difficulty due to the failure of those ships behind her to properly follow up. This left her vulnerable to ''Mucius'', ''Tourville'' and the ships following them, with which she began a furious fusillade. However, ''Defence'' was not the only ship of the van to break the French line; minutes later George Cranfield Berkeley in HMS ''Marlborough'' executed Howe's manoeuvre perfectly, raking and then entangling his ship with ''Impétueux''.

In front of ''Marlborough'' the rest of the van had mixed success. HMS ''Bellerophon'' and HMS ''Leviathan'' were both still suffering the effects of their exertions earlier in the week and did not breach the enemy line. Instead they pulled along the near side of ''Éole'' and ''America'' respectively and brought them to close gunnery duels. Rear-Admiral Thomas Pasley of ''Bellerophon'' was an early casualty, losing a leg in the opening exchanges. HMS ''Royal Sovereign'', Graves's flagship, was less successful due to a miscalculation of distance that resulted in her pulling up too far from the French line and coming under heavy fire from her opponent ''Terrible''. In the time it took to engage ''Terrible'' more closely, ''Royal Sovereign'' suffered a severe pounding and Admiral Graves was badly wounded.

More disturbing to Lord Howe were the actions of HMS ''Russell'' and HMS ''Caesar''. ''Russell's'' captain John Willett Payne was criticised at the time for failing to get to grips with the enemy more closely and allowing her opponent ''Téméraire'' to badly damage her rigging in the early stages, although later commentators blamed damage received on 29 May for her poor start to the action. There were no such excuses, however, for Captain Anthony Molloy of ''Caesar'', who totally failed in his duty to engage the enemy. Molloy completely ignored Howe's signal and continued ahead as if the British battleline was following him rather than engaging the French fleet directly. ''Caesar'' did participate in a desultory exchange of fire with the leading French ship ''Trajan'' but her fire had little effect, while ''Trajan'' inflicted much damage to ''Caesar's'' rigging and was subsequently able to attack ''Bellerophon'' as well, roaming unchecked through the melee developing at the head of the line.

Although ''Queen Charlotte'' pressed on all sail, she was not the first through the enemy line. That distinction belonged to a ship of the van squadron under Admiral Graves: HMS ''Defence'' under Captain James Gambier, a notoriously dour officer nicknamed "Dismal Jimmy" by his contemporaries. ''Defence'', the seventh ship of the British line, successfully cut the French line between its sixth and seventh ships; ''Mucius'' and ''Tourville''. Raking both opponents, ''Defence'' soon found herself in difficulty due to the failure of those ships behind her to properly follow up. This left her vulnerable to ''Mucius'', ''Tourville'' and the ships following them, with which she began a furious fusillade. However, ''Defence'' was not the only ship of the van to break the French line; minutes later George Cranfield Berkeley in HMS ''Marlborough'' executed Howe's manoeuvre perfectly, raking and then entangling his ship with ''Impétueux''.

In front of ''Marlborough'' the rest of the van had mixed success. HMS ''Bellerophon'' and HMS ''Leviathan'' were both still suffering the effects of their exertions earlier in the week and did not breach the enemy line. Instead they pulled along the near side of ''Éole'' and ''America'' respectively and brought them to close gunnery duels. Rear-Admiral Thomas Pasley of ''Bellerophon'' was an early casualty, losing a leg in the opening exchanges. HMS ''Royal Sovereign'', Graves's flagship, was less successful due to a miscalculation of distance that resulted in her pulling up too far from the French line and coming under heavy fire from her opponent ''Terrible''. In the time it took to engage ''Terrible'' more closely, ''Royal Sovereign'' suffered a severe pounding and Admiral Graves was badly wounded.

More disturbing to Lord Howe were the actions of HMS ''Russell'' and HMS ''Caesar''. ''Russell's'' captain John Willett Payne was criticised at the time for failing to get to grips with the enemy more closely and allowing her opponent ''Téméraire'' to badly damage her rigging in the early stages, although later commentators blamed damage received on 29 May for her poor start to the action. There were no such excuses, however, for Captain Anthony Molloy of ''Caesar'', who totally failed in his duty to engage the enemy. Molloy completely ignored Howe's signal and continued ahead as if the British battleline was following him rather than engaging the French fleet directly. ''Caesar'' did participate in a desultory exchange of fire with the leading French ship ''Trajan'' but her fire had little effect, while ''Trajan'' inflicted much damage to ''Caesar's'' rigging and was subsequently able to attack ''Bellerophon'' as well, roaming unchecked through the melee developing at the head of the line.

''

'' The conflict between ''Queen Charlotte'' and ''Montagne'' was oddly one-sided, the French flagship failing to make use of her lower-deck guns and consequently suffering extensive damage and casualties. ''Queen Charlotte'' in her turn was damaged by fire from nearby ships and was therefore unable to follow when ''Montagne'' set her remaining sails and slipped to the north to create a new focal point for the survivors of the French fleet. ''Queen Charlotte'' also took fire during the engagement from HMS ''Gibraltar'', under Thomas Mackenzie, which had failed to close with the enemy and instead fired at random into the smoke bank surrounding the flagship. Captain Sir Andrew Snape Douglas was seriously wounded by this fire. Following ''Montagnes escape, ''Queen Charlotte'' engaged ''Jacobin'' and ''Républicain'' as they passed, and was successful in forcing the surrender of ''Juste''. To the east of ''Queen Charlotte'', ''Brunswick'' and ''Vengeur du Peuple'' continued their bitter combat, locked together and firing main broadsides from point blank range. Captain Harvey of ''Brunswick'' was mortally wounded early in this action by langrage fire from ''Vengeur'', but refused to quit the deck, ordering more fire into his opponent.Harvey, John

The conflict between ''Queen Charlotte'' and ''Montagne'' was oddly one-sided, the French flagship failing to make use of her lower-deck guns and consequently suffering extensive damage and casualties. ''Queen Charlotte'' in her turn was damaged by fire from nearby ships and was therefore unable to follow when ''Montagne'' set her remaining sails and slipped to the north to create a new focal point for the survivors of the French fleet. ''Queen Charlotte'' also took fire during the engagement from HMS ''Gibraltar'', under Thomas Mackenzie, which had failed to close with the enemy and instead fired at random into the smoke bank surrounding the flagship. Captain Sir Andrew Snape Douglas was seriously wounded by this fire. Following ''Montagnes escape, ''Queen Charlotte'' engaged ''Jacobin'' and ''Républicain'' as they passed, and was successful in forcing the surrender of ''Juste''. To the east of ''Queen Charlotte'', ''Brunswick'' and ''Vengeur du Peuple'' continued their bitter combat, locked together and firing main broadsides from point blank range. Captain Harvey of ''Brunswick'' was mortally wounded early in this action by langrage fire from ''Vengeur'', but refused to quit the deck, ordering more fire into his opponent.Harvey, John

''

Villaret in ''Montagne'', having successfully broken contact with the British flagship and slipped away to the north, managed to gather 11 ships of the line around him and formed them up in a reconstituted battle squadron. At 11:30, with the main action drawing to a close, he began a recovery manoeuvre intended to lessen the tactical defeat his fleet had suffered. Aiming his new squadron at the battered ''Queen'', Villaret's attack created consternation in the British fleet, which was unprepared for a second engagement. However, discerning Villaret's intention, Howe also pulled his ships together to create a new force. His reformed squadron consisted of ''Queen Charlotte'', ''Royal Sovereign'', ''Valiant'', ''Leviathan'', ''Barfleur'', and ''Thunderer''. Howe deployed this squadron in defence of ''Queen'', and the two short lines engaged one another at a distance before Villaret abandoned his manoeuvre and hauled off to collect several of his own dismasted ships that were endeavouring to escape British pursuit. Villaret was subsequently joined by the battered ''Terrible'', which sailed straight through the dispersed British fleet to reach the French lines, and he also recovered the dismasted ''Scipion'', ''Mucius'', ''Jemmappes'', and ''Républicain''—all of which lay within reach of the unengaged British ships—before turning eastwards towards France. At this stage of the battle, Howe retired below and the British consolidation was left to his

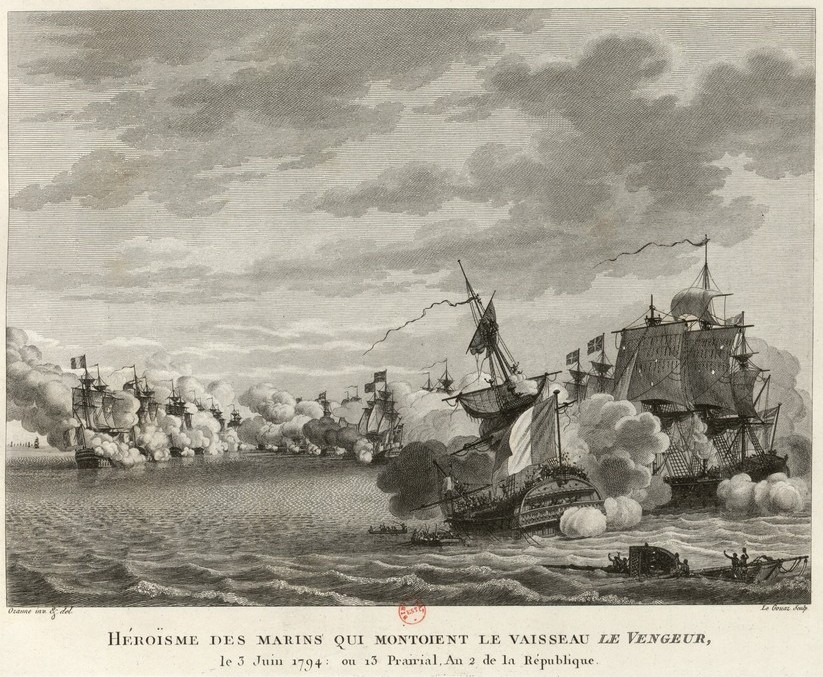

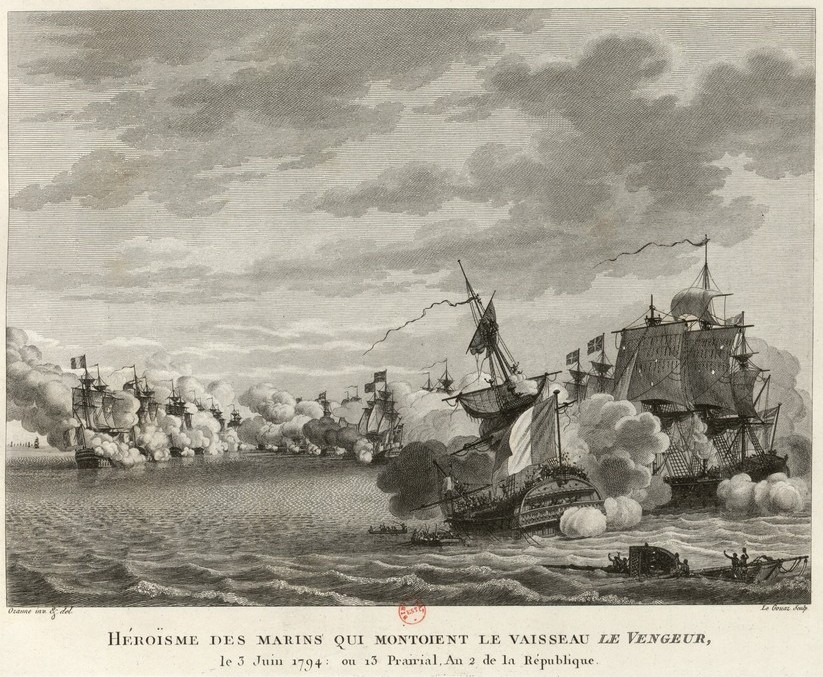

Villaret in ''Montagne'', having successfully broken contact with the British flagship and slipped away to the north, managed to gather 11 ships of the line around him and formed them up in a reconstituted battle squadron. At 11:30, with the main action drawing to a close, he began a recovery manoeuvre intended to lessen the tactical defeat his fleet had suffered. Aiming his new squadron at the battered ''Queen'', Villaret's attack created consternation in the British fleet, which was unprepared for a second engagement. However, discerning Villaret's intention, Howe also pulled his ships together to create a new force. His reformed squadron consisted of ''Queen Charlotte'', ''Royal Sovereign'', ''Valiant'', ''Leviathan'', ''Barfleur'', and ''Thunderer''. Howe deployed this squadron in defence of ''Queen'', and the two short lines engaged one another at a distance before Villaret abandoned his manoeuvre and hauled off to collect several of his own dismasted ships that were endeavouring to escape British pursuit. Villaret was subsequently joined by the battered ''Terrible'', which sailed straight through the dispersed British fleet to reach the French lines, and he also recovered the dismasted ''Scipion'', ''Mucius'', ''Jemmappes'', and ''Républicain''—all of which lay within reach of the unengaged British ships—before turning eastwards towards France. At this stage of the battle, Howe retired below and the British consolidation was left to his  In fact, the British fleet was unable to pursue Villaret, having only 11 ships still capable of battle to the French 12, and having numerous dismasted ships and prizes to protect. Retiring and regrouping, the British crews set about making hasty repairs and securing their prizes; seven in total, including the badly damaged ''Vengeur du Peuple''. ''Vengeur'' had been holed by cannon firing from ''Brunswick'' directly through the ship's bottom, and after her surrender no British ship had managed to get men aboard. This left ''Vengeurs few remaining unwounded crew to attempt to salvage what they could—a task made harder when some of her sailors broke into the spirit room and became drunk. Ultimately the ship's pumps became unmanageable, and ''Vengeur'' began to sink. Only the timely arrival of boats from the undamaged ''Alfred'' and HMS ''Culloden'', as well as the services of the cutter HMS ''Rattler'', saved any of the ''Vengeur's'' crew from drowning, these ships taking off nearly 500 sailors between them. Lieutenant John Winne of ''Rattler'' was especially commended for this hazardous work. By 18:15, ''Vengeur'' was clearly beyond salvage and only the very worst of the wounded, the dead, and the drunk remained aboard. Several sailors are said to have waved the tricolor from the bow of the ship and cried "Vive la Nation, vive la République!"

Having escaped to the east, Villaret made what sail his battered fleet could muster to return to France, and dispatched his frigates in search of the convoy. Villaret was also hoping for reinforcements; eight ships of the line, commanded by Admiral Pierre-François Cornic Dumoulin, were patrolling near the

In fact, the British fleet was unable to pursue Villaret, having only 11 ships still capable of battle to the French 12, and having numerous dismasted ships and prizes to protect. Retiring and regrouping, the British crews set about making hasty repairs and securing their prizes; seven in total, including the badly damaged ''Vengeur du Peuple''. ''Vengeur'' had been holed by cannon firing from ''Brunswick'' directly through the ship's bottom, and after her surrender no British ship had managed to get men aboard. This left ''Vengeurs few remaining unwounded crew to attempt to salvage what they could—a task made harder when some of her sailors broke into the spirit room and became drunk. Ultimately the ship's pumps became unmanageable, and ''Vengeur'' began to sink. Only the timely arrival of boats from the undamaged ''Alfred'' and HMS ''Culloden'', as well as the services of the cutter HMS ''Rattler'', saved any of the ''Vengeur's'' crew from drowning, these ships taking off nearly 500 sailors between them. Lieutenant John Winne of ''Rattler'' was especially commended for this hazardous work. By 18:15, ''Vengeur'' was clearly beyond salvage and only the very worst of the wounded, the dead, and the drunk remained aboard. Several sailors are said to have waved the tricolor from the bow of the ship and cried "Vive la Nation, vive la République!"

Having escaped to the east, Villaret made what sail his battered fleet could muster to return to France, and dispatched his frigates in search of the convoy. Villaret was also hoping for reinforcements; eight ships of the line, commanded by Admiral Pierre-François Cornic Dumoulin, were patrolling near the

With a large portion of his fleet no longer battleworthy, Howe was unable to resume his search for the French convoy in the Bay of Biscay. The Admiralty, though unaware of Howe's specific circumstances, knew a battle had taken place through the arrival of HMS ''Audacious'' in Portsmouth, and was preparing a second expedition under George Montagu. Montagu had returned to England after his unsuccessful May cruise, and was refitting in Portsmouth when ordered to sea again. His force of ten ships was intended to both cover Howe's withdrawal from Biscay, and find and attack the French grain convoy. Montagu returned to sea on 3 June, and by 8 June was off Ushant searching for signs of either the French or Howe; unknown to him, neither had yet entered European waters. At 15:30 on 8 June Montagu spotted sails, and soon identified them as the enemy. He had located Cornic's squadron, which was also patrolling for the convoy and the returning fleets. Montagu gave chase and drove Cornic into Bertheaume Bay, where he blockaded the French squadron overnight, hoping to bring them to action the following day. However, on 9 June, Montagu sighted 19 French ships appearing from the west—the remnants of Villaret's fleet. Hastily turning his ships, Montagu sailed south to avoid becoming trapped between two forces which might easily overwhelm him. Villaret and Cornic gave chase for a day before turning east towards the safety of the French ports.

Howe benefited from Montagu's withdrawal, as his own battered fleet passed close to the scene of this stand-off on 10 June, pushing north into the English Channel. With Villaret and Cornic fortuitously pursuing Montagu to the south, Howe was free to pass Ushant without difficulty and arrived off

With a large portion of his fleet no longer battleworthy, Howe was unable to resume his search for the French convoy in the Bay of Biscay. The Admiralty, though unaware of Howe's specific circumstances, knew a battle had taken place through the arrival of HMS ''Audacious'' in Portsmouth, and was preparing a second expedition under George Montagu. Montagu had returned to England after his unsuccessful May cruise, and was refitting in Portsmouth when ordered to sea again. His force of ten ships was intended to both cover Howe's withdrawal from Biscay, and find and attack the French grain convoy. Montagu returned to sea on 3 June, and by 8 June was off Ushant searching for signs of either the French or Howe; unknown to him, neither had yet entered European waters. At 15:30 on 8 June Montagu spotted sails, and soon identified them as the enemy. He had located Cornic's squadron, which was also patrolling for the convoy and the returning fleets. Montagu gave chase and drove Cornic into Bertheaume Bay, where he blockaded the French squadron overnight, hoping to bring them to action the following day. However, on 9 June, Montagu sighted 19 French ships appearing from the west—the remnants of Villaret's fleet. Hastily turning his ships, Montagu sailed south to avoid becoming trapped between two forces which might easily overwhelm him. Villaret and Cornic gave chase for a day before turning east towards the safety of the French ports.

Howe benefited from Montagu's withdrawal, as his own battered fleet passed close to the scene of this stand-off on 10 June, pushing north into the English Channel. With Villaret and Cornic fortuitously pursuing Montagu to the south, Howe was free to pass Ushant without difficulty and arrived off

''

''

Tome 5

pp. 17–27

British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies.

* British national identity, the characteristics of British people and culture ...

and French navies during the War of the First Coalition

The War of the First Coalition () was a set of wars that several European powers fought between 1792 and 1797, initially against the Constitutional Cabinet of Louis XVI, constitutional Kingdom of France and then the French First Republic, Frenc ...

. It was the first and largest fleet action of the French Revolutionary Wars

The French Revolutionary Wars () were a series of sweeping military conflicts resulting from the French Revolution that lasted from 1792 until 1802. They pitted French First Republic, France against Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain, Habsb ...

.

The action was the culmination of the Atlantic campaign of May 1794, which had criss-crossed the Bay of Biscay

The Bay of Biscay ( ) is a gulf of the northeast Atlantic Ocean located south of the Celtic Sea. It lies along the western coast of France from Point Penmarc'h to the Spanish border, and along the northern coast of Spain, extending westward ...

over the previous month and saw both sides capturing numerous merchant ships and small warships along with engaging in two partial, but inconclusive, fleet actions. The British Channel Squadron under Admiral Lord Howe attempted to prevent the passage of a vital French grain

A grain is a small, hard, dry fruit (caryopsis) – with or without an attached husk, hull layer – harvested for human or animal consumption. A grain crop is a grain-producing plant. The two main types of commercial grain crops are cereals and ...

convoy

A convoy is a group of vehicles, typically motor vehicles or ships, traveling together for mutual support and protection. Often, a convoy is organized with armed defensive support and can help maintain cohesion within a unit. It may also be used ...

from the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

, which was protected by the French Atlantic Squadron, commanded by Counter-admiral Louis Thomas Villaret de Joyeuse. The two forces clashed in the Atlantic Ocean, some west of the French island of Ushant

Ushant (; , ; , ) is a French island at the southwestern end of the English Channel which marks the westernmost point of metropolitan France. It belongs to Brittany and in medieval times, Léon. In lower tiers of government, it is a commune in t ...

on 1 June 1794.

During the battle, Howe defied naval convention by ordering his fleet to turn towards the French and for each of his vessels to rake

Rake may refer to:

Common meanings

* Rake (tool), a horticultural implement, a long-handled tool with tines

* Rake (stock character), a man habituated to immoral conduct

* Rake (poker), the commission taken by the house when hosting a poker game

...

and engage their immediate opponent. This unexpected order was not understood by all of his captains, and as a result, his attack was more piecemeal than he intended. Nevertheless, his ships inflicted a severe tactical defeat on the French fleet. In the aftermath of the battle both fleets were left shattered; in no condition for further combat, Howe and Villaret returned to their home ports. Despite losing seven of his ships of the line

A ship of the line was a type of naval warship constructed during the Age of Sail from the 17th century to the mid-19th century. The ship of the line was designed for the naval tactic known as the line of battle, which involved the two column ...

, Villaret had bought enough time for the French grain convoy to reach safety unimpeded by Howe's fleet, securing a strategic success. However, he was also forced to withdraw his battle fleet back to port, leaving the British free to conduct a campaign of blockade

A blockade is the act of actively preventing a country or region from receiving or sending out food, supplies, weapons, or communications, and sometimes people, by military force.

A blockade differs from an embargo or sanction, which are ...

for the remainder of the war. In the immediate aftermath, both sides claimed victory and the outcome of the battle was seized upon by the press of both nations as a demonstration of the prowess and bravery of their respective navies.

The battle demonstrated a number of the major problems inherent in the French and British navies at the start of the French Revolutionary Wars. Both admirals were faced with disobedience from their captains, along with ill-discipline and poor training among their shorthanded crews, and they failed to control their fleets effectively during the height of the combat.

Background

Since early 1792 France had been at war with four of its neighbours on two fronts, battling theHabsburg monarchy

The Habsburg monarchy, also known as Habsburg Empire, or Habsburg Realm (), was the collection of empires, kingdoms, duchies, counties and other polities (composite monarchy) that were ruled by the House of Habsburg. From the 18th century it is ...

and Prussia

Prussia (; ; Old Prussian: ''Prūsija'') was a Germans, German state centred on the North European Plain that originated from the 1525 secularization of the Prussia (region), Prussian part of the State of the Teutonic Order. For centuries, ...

in the Austrian Netherlands

The Austrian Netherlands was the territory of the Burgundian Circle of the Holy Roman Empire between 1714 and 1797. The period began with the acquisition by the Austrian Habsburg monarchy of the former Spanish Netherlands under the Treaty of Ras ...

, and the Austrians and Piedmontese

Piedmontese ( ; autonym: or ; ) is a language spoken by some 2,000,000 people mostly in Piedmont, a region of Northwest Italy. Although considered by most linguists a separate language, in Italy it is often mistakenly regarded as an Italian ...

in Italy. On 2 January 1793, almost one year into the French Revolutionary War

The French Revolutionary Wars () were a series of sweeping military conflicts resulting from the French Revolution that lasted from 1792 until 1802. They pitted France against Great Britain, Austria, Prussia, Russia, and several other countries ...

, republican-held forts at Brest in Brittany fired on the British brig

A brig is a type of sailing vessel defined by its rig: two masts which are both square rig, square-rigged. Brigs originated in the second half of the 18th century and were a common type of smaller merchant vessel or warship from then until the l ...

HMS '' Childers''. A few weeks later, following the execution

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty and formerly called judicial homicide, is the state-sanctioned killing of a person as punishment for actual or supposed misconduct. The sentence ordering that an offender be punished in ...

of the imprisoned King Louis XVI

Louis XVI (Louis-Auguste; ; 23 August 1754 – 21 January 1793) was the last king of France before the fall of the monarchy during the French Revolution. The son of Louis, Dauphin of France (1729–1765), Louis, Dauphin of France (son and heir- ...

, diplomatic ties between Britain and France were broken. On 1 February, France declared war on both Britain and the Dutch Republic

The United Provinces of the Netherlands, commonly referred to in historiography as the Dutch Republic, was a confederation that existed from 1579 until the Batavian Revolution in 1795. It was a predecessor state of the present-day Netherlands ...

.

Protected from immediate invasion by the English Channel

The English Channel, also known as the Channel, is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that separates Southern England from northern France. It links to the southern part of the North Sea by the Strait of Dover at its northeastern end. It is the busi ...

, Britain prepared for an extensive naval campaign and dispatched troops to the Netherlands for service against the French. Throughout the remainder of 1793, the British and French navies undertook minor operations in Northern waters, the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern ...

and the West

West is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from east and is the direction in which the Sun sets on the Earth.

Etymology

The word "west" is a Germanic word passed into some Romance langu ...

and East Indies

The East Indies (or simply the Indies) is a term used in historical narratives of the Age of Discovery. The ''Indies'' broadly referred to various lands in Eastern world, the East or the Eastern Hemisphere, particularly the islands and mainl ...

, where both nations maintained colonies

A colony is a territory subject to a form of foreign rule, which rules the territory and its indigenous peoples separated from the foreign rulers, the colonizer, and their '' metropole'' (or "mother country"). This separated rule was often or ...

. The closest the British Channel Squadron had come to an engagement was when it had narrowly missed intercepting the French convoy from the Caribbean, escorted by 15 ships of the line on 2 August. The only major clash was the Siege of Toulon

The siege of Toulon (29 August – 19 December 1793) was a military engagement that took place during the Federalist revolts and the War of the First Coalition, part of the French Revolutionary Wars. It was undertaken by forces of the French Re ...

, a confused and bloody affair in which the British force holding the town—alongside Spanish

Spanish might refer to:

* Items from or related to Spain:

**Spaniards are a nation and ethnic group indigenous to Spain

**Spanish language, spoken in Spain and many countries in the Americas

**Spanish cuisine

**Spanish history

**Spanish culture

...

, Sardinian, Austrian and French Royalist troops—had to be evacuated by the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

to prevent its imminent defeat at the hands of the French Revolutionary Army

The French Revolutionary Army () was the French land force that fought the French Revolutionary Wars from 1792 to 1802. In the beginning, the French armies were characterised by their revolutionary fervour, their poor equipment and their great nu ...

. The aftermath of this siege was punctuated by recriminations and accusations of cowardice and betrayal among the allies, eventually resulting in Spain switching allegiance with the signing of the Treaty of San Ildefonso two years later. Nevertheless, the siege produced one major success: Sir Sidney Smith, with parties of sailors from the retreating British fleet, accomplished the destruction of substantial French naval stores and shipping in Toulon

Toulon (, , ; , , ) is a city in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region of southeastern France. Located on the French Riviera and the historical Provence, it is the prefecture of the Var (department), Var department.

The Commune of Toulon h ...

. More might have been achieved had the Spanish raiding parties that accompanied Smith not been issued with secret orders to stall the destruction of the French fleet.

The situation in Europe remained volatile into 1794. Off northern France, the French Atlantic Squadron had mutinied due to errors in provisions and pay. In consequence, the French Navy officer corps suffered greatly from the effects of the Reign of Terror

The Reign of Terror (French: ''La Terreur'', literally "The Terror") was a period of the French Revolution when, following the creation of the French First Republic, First Republic, a series of massacres and Capital punishment in France, nu ...

, with many experienced sailors being executed, imprisoned or dismissed from the service for perceived disloyalty. The shortage of provisions was more than a navy problem though; France itself was starving because the social upheavals of the previous year had combined with a harsh winter to ruin the harvest. By this time at war with all her neighbours, France had nowhere to turn for overland imports of fresh provisions. Eventually a solution to the food crisis was agreed by the National Convention

The National Convention () was the constituent assembly of the Kingdom of France for one day and the French First Republic for its first three years during the French Revolution, following the two-year National Constituent Assembly and the ...

: food produced in France's overseas colonies would be concentrated on board a fleet of merchant ships gathered in Chesapeake Bay

The Chesapeake Bay ( ) is the largest estuary in the United States. The bay is located in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region and is primarily separated from the Atlantic Ocean by the Delmarva Peninsula, including parts of the Ea ...

, and augmented with food and goods purchased from the United States. During April and May 1794, the merchantmen would convoy the supplies across the Atlantic to Brest, protected by elements of the Atlantic Squadron.

Fleets

The navies of Britain and France in 1794 were at very different stages of development. Although the British fleet was numerically superior, the French ships were larger (even if more lightly built), and carried a heavier weight of shot. The largest French ships were three-decker first rates, carrying 110 or 120 guns, against 100 guns on the largest British vessels.Royal Navy

Since theNootka Crisis

The Nootka Crisis, also known as the Spanish Armament, was an international incident and political dispute between Spain and Great Britain triggered by a series of events revolving around sovereignty claims and rights of navigation and trade. It ...

of 1790, the Royal Navy had been at sea in a state of readiness for over three years. The Navy's dockyards under First Lord of the Admiralty

First Lord of the Admiralty, or formally the Office of the First Lord of the Admiralty, was the title of the political head of the English and later British Royal Navy. He was the government's senior adviser on all naval affairs, responsible f ...

Charles Middleton were all fully fitted and prepared for conflict. This was quite unlike the disasters of the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was the armed conflict that comprised the final eight years of the broader American Revolution, in which Am ...

ten years earlier, when an ill-prepared Royal Navy had taken too long to reach full effectiveness and was consequently unable to support the North American campaign, which ended in defeat at the Siege of Yorktown

The siege of Yorktown, also known as the Battle of Yorktown and the surrender at Yorktown, was the final battle of the American Revolutionary War. It was won decisively by the Continental Army, led by George Washington, with support from the Ma ...

due to lack of supplies. With British dockyards now readily turning out cannon, shot, sails, provisions and other essential equipment, the only remaining problem was that of manning the several hundred ships on the Navy list.

Unfortunately for the British, gathering sufficient manpower was difficult and never satisfactorily accomplished throughout the entire war. The shortage of seamen was such that press gangs were forced to take thousands of men with no experience on the sea, meaning that training and preparing them for naval life would take quite some time. The lack of Royal Marines

The Royal Marines provide the United Kingdom's amphibious warfare, amphibious special operations capable commando force, one of the :Fighting Arms of the Royal Navy, five fighting arms of the Royal Navy, a Company (military unit), company str ...

was even more urgent, and soldiers from the British Army

The British Army is the principal Army, land warfare force of the United Kingdom. the British Army comprises 73,847 regular full-time personnel, 4,127 Brigade of Gurkhas, Gurkhas, 25,742 Army Reserve (United Kingdom), volunteer reserve perso ...

were drafted into the fleet for service at sea. Men of the 2nd. Regiment of Foot – The Queen's (Royal West Surrey Regiment) and the 29th Regiment of Foot served aboard Royal Navy ships during the campaign; their descendant regiments still maintain the battle honour

A battle honour is an award of a right by a government or sovereign to a military unit to emblazon the name of a battle or Military operation, operation on its flags ("colours"), uniforms or other accessories where ornamentation is possible.

In ...

"1 June 1794".The Glorious First of June 1794'' Worcestershire Regiment'', retrieved 23 December 2007The Glorious First of June 1794

, ''Queen's Royal West Surrey Regiment'', retrieved 1 January 2008 Despite these difficulties, the Channel Squadron was possessed of one of the best naval commanders of the age; its commander-in-chief,

Richard Howe, 1st Earl Howe

Admiral of the Fleet Richard Howe, 1st Earl Howe (8 March 1726 – 5 August 1799) was a Royal Navy officer and politician. After serving in the War of the Austrian Succession, he gained a reputation for his role in amphibious operations agai ...

, had learned his trade under Edward Hawke, 1st Baron Hawke

Admiral of the Fleet (Royal Navy), Admiral of the Fleet Edward Hawke, 1st Baron Hawke, (21 February 1705 – 17 October 1781) was a Royal Navy officer and politician. As captain of the third-rate , he took part in the Battle of Toulon (1744), ...

and fought at the Battle of Quiberon Bay

The Battle of Quiberon Bay (known as the ''Bataille des Cardinaux'' by the French) was a decisive naval engagement during the Seven Years' War. It was fought on 20 November 1759 between the Royal Navy and the French Navy in Quiberon Bay, off ...

in 1759.Howe, Richard''

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

The ''Dictionary of National Biography'' (''DNB'') is a standard work of reference on notable figures from History of the British Isles, British history, published since 1885. The updated ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (''ODNB'') ...

'', Roger Knight, retrieved 23 December 2007 In the spring of 1794, with the French convoy's arrival in European waters imminent, Howe had dispersed his fleet in three groups. George Montagu, in HMS ''Hector'', was sent with six ships of the line and two frigate

A frigate () is a type of warship. In different eras, the roles and capabilities of ships classified as frigates have varied.

The name frigate in the 17th to early 18th centuries was given to any full-rigged ship built for speed and maneuvera ...

s to guard British convoys to the East Indies, West Indies and Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region of Labrador, having a total size of . As of 2025 the population ...

as far as Cape Finisterre

Cape Finisterre (, also ; ; ) is a rock-bound peninsula on the west coast of Galicia, Spain.

In Roman times it was believed to be an end of the known world. The name Finisterre, like that of Finistère in France, derives from the Latin , mean ...

. Peter Rainier, in HMS ''Suffolk and commanding six other ships, was to escort the convoys for the rest of their passage. The third force consisted of 26 ships of the line, with several supporting vessels, under Howe's direct command. They were to patrol the Bay of Biscay for the arriving French.

French Navy

In contrast to their British counterparts, theFrench Navy

The French Navy (, , ), informally (, ), is the Navy, maritime arm of the French Armed Forces and one of the four military service branches of History of France, France. It is among the largest and most powerful List of navies, naval forces i ...

was in a state of confusion. Although the quality of the fleet's ships was high, the fleet hierarchy was riven by the same crises that had torn through France since the Revolution

In political science, a revolution (, 'a turn around') is a rapid, fundamental transformation of a society's class, state, ethnic or religious structures. According to sociologist Jack Goldstone, all revolutions contain "a common set of elements ...

five years earlier. Consequently, the high standard of ships and ordnance was not matched by that of the available crews, which were largely untrained and inexperienced. With the Terror resulting in the death or dismissal of many senior French sailors and officers, political appointees and conscripts—many of whom had never been to sea at all, let alone in a fighting vessel—filled the Atlantic Squadron.

The manpower problem was compounded by the supply crisis which was affecting the entire nation, with the fleet going unpaid and largely unfed for months at times. In August 1793, these problems came to a head in the Brest Fleet, when a lack of provisions resulted in a mutiny among the fleet's naval rating

In military terminology, a rate or rating (also known as bluejacket in the United States) is a junior enlisted sailor in a navy who is below the military rank of warrant officer. Depending on the country and navy that uses it, the exact te ...

s. The crews overruled their officers and brought their ships into harbour in search of food, leaving the French coast undefended. The National Convention

The National Convention () was the constituent assembly of the Kingdom of France for one day and the French First Republic for its first three years during the French Revolution, following the two-year National Constituent Assembly and the ...

responded by instantly executing a swathe of the fleet's senior officers and non-commissioned officers. Hundreds more officers and sailors were imprisoned, banished or dismissed from the navy. The effect of this purge was devastating, seriously degrading the fighting ability of the fleet by removing at a stroke many of its most capable personnel. In their places were promoted junior officers, merchant captains and even civilians who expressed sufficient revolutionary zeal, although few of them knew how to fight or control a battle fleet at sea.

The newly appointed commander of this troubled fleet was Louis Thomas Villaret de Joyeuse; although formerly in a junior position, he was known to possess a high degree of tactical ability, and had served under Vice-Admiral Pierre André de Suffren

Pierre is a masculine given name. It is a French form of the name Peter. Pierre originally meant "rock" or "stone" in French (derived from the Greek word πέτρος (''petros'') meaning "stone, rock", via Latin "petra"). It is a translation ...

in the Indian Ocean during the American War of Independence. However, Villaret's attempts to mould his new officer corps into an effective fighting unit were hampered by another new appointee, a deputy of the National Convention named Jean-Bon Saint-André. Saint-André's job was to report directly to the National Convention on the revolutionary ardour of both the fleet and its admiral. He frequently intervened in strategic planning and tactical operations. Shortly after his arrival, Saint-André proposed issuing a decree ordering that any officer deemed to have shown insufficient zeal in defending his ship in action should be put to death on his return to France, although this highly controversial legislation does not appear to have ever been acted upon. Although his interference was a source of frustration for Villaret, Saint-André's dispatches to Paris were published regularly in ''Le Moniteur Universel

() was a French newspaper founded in Paris on November 24, 1789 under the title by Charles-Joseph Panckoucke, and which ceased publication on December 31, 1868. It was the main French newspaper during the French Revolution and was for a long ...

'', and did much to popularise the Navy in France.

The Atlantic Squadron was even more dispersed than the British in the spring of 1794: Counter-Admiral Pierre Jean Van Stabel had been dispatched, with five ships including two of the line, to meet the much-needed French grain convoy off the American eastern seaboard. Counter-Admiral Joseph-Marie Nielly had sailed from Rochefort with five ships of the line and assorted cruising warships to rendezvous with the convoy in the mid-Atlantic. This left Villaret with 25 ships of the line at Brest to meet the threat posed by the British fleet under Lord Howe.

Convoy

By early spring of 1794, the situation in France was dire. With famine looming after the failure of the harvest and the blockade of French ports and trade, the French government was forced to look overseas for sustenance. Turning to France's colonies in the Americas, and the agricultural bounty of the United States, the National Convention gave orders for the formation of a large convoy of sailing vessels to gather atHampton Roads

Hampton Roads is a body of water in the United States that serves as a wide channel for the James River, James, Nansemond River, Nansemond, and Elizabeth River (Virginia), Elizabeth rivers between Old Point Comfort and Sewell's Point near whe ...

in the Chesapeake Bay

The Chesapeake Bay ( ) is the largest estuary in the United States. The bay is located in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region and is primarily separated from the Atlantic Ocean by the Delmarva Peninsula, including parts of the Ea ...

, where Admiral Vanstabel would wait for them. According to contemporary historian William James

William James (January 11, 1842 – August 26, 1910) was an American philosopher and psychologist. The first educator to offer a psychology course in the United States, he is considered to be one of the leading thinkers of the late 19th c ...

this conglomeration of ships was said to be over 350 strong, although he disputes this figure, citing the number as 117 (in addition to the French warships).

The convoy had also been augmented by the United States government, in both cargo and shipping, as repayment for French financial, moral and military support during the American Revolution

The American Revolution (1765–1783) was a colonial rebellion and war of independence in which the Thirteen Colonies broke from British America, British rule to form the United States of America. The revolution culminated in the American ...

. In supporting the French Revolution in this way, the American government, urged especially by Ambassador Gouverneur Morris

Gouverneur Morris ( ; January 31, 1752 – November 6, 1816) was an American statesman, a Founding Father of the United States, and a signatory to the Articles of Confederation and the United States Constitution. He wrote the Preamble to the ...

, was fulfilling its ten-year-old debt to France. Friendly relations between the United States and France did not long survive the Jay Treaty

The Treaty of Amity, Commerce, and Navigation, Between His Britannic Majesty and the United States of America, commonly known as the Jay Treaty, and also as Jay's Treaty, was a 1794 treaty between the United States and Great Britain that averted ...

which came into effect in 1796; by 1798 the two nations would be engaged in the Quasi War

The Quasi-War was an undeclared war from 1798 to 1800 between the United States and the French First Republic. It was fought almost entirely at sea, primarily in the Caribbean and off the East Coast of the United States, with minor actions in ...

.

May 1794

The French convoy, escorted by Vanstabel, departed America fromVirginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States between the East Coast of the United States ...

on 2 April, and Howe sailed from Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port city status in the United Kingdom, city and unitary authority in Hampshire, England. Most of Portsmouth is located on Portsea Island, off the south coast of England in the Solent, making Portsmouth the only city in En ...

on 2 May, taking his entire fleet to both escort British convoys to the Western Approaches

The Western Approaches is an approximately rectangular area of the Atlantic Ocean lying immediately to the west of Ireland and parts of Great Britain. Its north and south boundaries are defined by the corresponding extremities of Britain. The c ...

and intercept the French. Checking that Villaret was still in Brest, Howe spent two weeks searching the Bay of Biscay for the grain convoy, returning to Brest on 18 May to discover that Villaret had sailed the previous day. Returning to sea in search of his opponent, Howe pursued Villaret deep into the Atlantic. Also at sea during this period were the squadrons of Nielly (French) and Montagu (British), both of whom had met with some success; Nielly had captured a number of British merchant ships and Montagu had taken several back. Nielly was the first to encounter the grain convoy, deep in the Atlantic in the second week of May. He took it under escort as it moved closer to Europe, while Montagu was searching fruitlessly to the south.

Despite Howe's pursuit, the main French sortie found initial success, running into a Dutch convoy and taking 20 ships from it on Villaret's first day at sea. For the next week Howe continued to follow the French, seizing and burning a trail of French-held Dutch ships and enemy corvettes. On 25 May Howe spotted a straggler from Villaret's fleet and gave chase; ''Audacieux'' led Howe straight to his opponent's location. Having finally found Villaret, on 28 May Howe attacked, using a flying squadron of his fastest ships to cut off its rearmost vessel ''Révolutionnaire''. This first rate

In the rating system of the Royal Navy used to categorise sailing warships, a first rate was the designation for the largest ships of the line. Originating in the Jacobean era with the designation of Ships Royal capable of carrying at least ...

was at various times engaged with six British ships and took heavy damage, possibly striking her colours late in the action. As darkness fell the British and French fleets separated, leaving ''Révolutionnaire'' and her final enemy, HMS ''Audacious'', still locked in combat behind them. These two ships parted company during the night and eventually returned to their respective home ports. By this stage Villaret knew through his patrolling frigates that the grain convoy was close, and deliberately took his fleet to the west, hoping to decoy Howe away from the vital convoy.

Taking the bait, the following day Howe attacked again, but his attempt to split the French fleet in half was unsuccessful when his lead ship, HMS ''Caesar'', failed to follow orders. Much damage was done to both fleets but the action was inconclusive, and the two forces again separated without having settled the issue. Howe had however gained an important advantage during the engagement by seizing the weather gage

The weather gage (sometimes spelled weather gauge or known as nautical gauge) is the advantageous position of a fighting sailing vessel relative to another. The concept is from the Age of Sail and is now antique. A ship at sea is said to possess ...

, enabling him to further attack Villaret at a time of his choosing. Three French ships were sent back to port with damage, but these losses were offset by reinforcements gained the following day with the arrival of Nielly's detached squadron.Battle was postponed during the next two days because of thick fog, but when the haze lifted on 1 June 1794, the battle lines were only 6 miles (10 km) apart and Howe was prepared to force a decisive action.

First of June

Although Howe was in a favourable position, Villaret had not been idle during the night. He had attempted, with near success, to distance his ships from the British fleet; when dawn broke at 05:00 he was within a few hours of gaining enough wind to escape over the horizon. Allowing his men to breakfast, Howe took full advantage of his position on the weather gage to close with Villaret, and by 08:12 the British fleet was just four miles (6 km) from the enemy. By this time, Howe's formation was deployed in an organised line parallel to the French, withfrigate

A frigate () is a type of warship. In different eras, the roles and capabilities of ships classified as frigates have varied.

The name frigate in the 17th to early 18th centuries was given to any full-rigged ship built for speed and maneuvera ...

s acting as repeaters for the admiral's commands.The French were likewise in line ahead and the two lines began exchanging long-range gunfire at 09:24, whereupon Howe unleashed his innovative battleplan.

It was normal in fleet actions of the 18th century for the two lines of battle to pass one another sedately, exchanging fire at long ranges and then wearing away, often without either side losing a ship or taking an enemy. In contrast, Howe was counting on the professionalism of his captains and crews combined with the advantage of the weather gage to attack the French directly, driving through their line. However, this time he did not plan to manoeuvre in the way he had during the two previous encounters, each ship following in the wake of that in front to create a new line arrowing through his opponent's force (as Rodney had done at the Battle of the Saintes

The Battle of the Saintes (known to the French as the Bataille de la Dominique), also known as the Battle of Dominica, was an important naval battle in the Caribbean between the British and the French that took place 9–12 April 1782. The Brit ...

12 years earlier). Instead, Howe ordered each of his ships to turn individually towards the French line, intending to breach it at every point and rake the French ships at both bow and stern. The British captains would then pull up on the leeward side of their opposite numbers, cutting them off from their retreat downwind, and engage them directly, hopefully forcing each to surrender and consequently destroying the French Atlantic Fleet.

British break the line

Within minutes of issuing the signal and turning his flagship HMS ''Queen Charlotte'', Howe's plan began to falter. Many of the British captains had either misunderstood or ignored the signal and were hanging back in the original line. Other ships were still struggling with damage from Howe's earlier engagements and could not get into action fast enough. The result was a ragged formation tipped by ''Queen Charlotte'' that headed unevenly for Villaret's fleet. The French responded by firing on the British ships as they approached, but the lack of training and coordination in the French fleet was obvious; many ships which did obey Howe's order and attacked the French directly arrived in action without significant damage.Van squadron

Although ''Queen Charlotte'' pressed on all sail, she was not the first through the enemy line. That distinction belonged to a ship of the van squadron under Admiral Graves: HMS ''Defence'' under Captain James Gambier, a notoriously dour officer nicknamed "Dismal Jimmy" by his contemporaries. ''Defence'', the seventh ship of the British line, successfully cut the French line between its sixth and seventh ships; ''Mucius'' and ''Tourville''. Raking both opponents, ''Defence'' soon found herself in difficulty due to the failure of those ships behind her to properly follow up. This left her vulnerable to ''Mucius'', ''Tourville'' and the ships following them, with which she began a furious fusillade. However, ''Defence'' was not the only ship of the van to break the French line; minutes later George Cranfield Berkeley in HMS ''Marlborough'' executed Howe's manoeuvre perfectly, raking and then entangling his ship with ''Impétueux''.

In front of ''Marlborough'' the rest of the van had mixed success. HMS ''Bellerophon'' and HMS ''Leviathan'' were both still suffering the effects of their exertions earlier in the week and did not breach the enemy line. Instead they pulled along the near side of ''Éole'' and ''America'' respectively and brought them to close gunnery duels. Rear-Admiral Thomas Pasley of ''Bellerophon'' was an early casualty, losing a leg in the opening exchanges. HMS ''Royal Sovereign'', Graves's flagship, was less successful due to a miscalculation of distance that resulted in her pulling up too far from the French line and coming under heavy fire from her opponent ''Terrible''. In the time it took to engage ''Terrible'' more closely, ''Royal Sovereign'' suffered a severe pounding and Admiral Graves was badly wounded.

More disturbing to Lord Howe were the actions of HMS ''Russell'' and HMS ''Caesar''. ''Russell's'' captain John Willett Payne was criticised at the time for failing to get to grips with the enemy more closely and allowing her opponent ''Téméraire'' to badly damage her rigging in the early stages, although later commentators blamed damage received on 29 May for her poor start to the action. There were no such excuses, however, for Captain Anthony Molloy of ''Caesar'', who totally failed in his duty to engage the enemy. Molloy completely ignored Howe's signal and continued ahead as if the British battleline was following him rather than engaging the French fleet directly. ''Caesar'' did participate in a desultory exchange of fire with the leading French ship ''Trajan'' but her fire had little effect, while ''Trajan'' inflicted much damage to ''Caesar's'' rigging and was subsequently able to attack ''Bellerophon'' as well, roaming unchecked through the melee developing at the head of the line.

Although ''Queen Charlotte'' pressed on all sail, she was not the first through the enemy line. That distinction belonged to a ship of the van squadron under Admiral Graves: HMS ''Defence'' under Captain James Gambier, a notoriously dour officer nicknamed "Dismal Jimmy" by his contemporaries. ''Defence'', the seventh ship of the British line, successfully cut the French line between its sixth and seventh ships; ''Mucius'' and ''Tourville''. Raking both opponents, ''Defence'' soon found herself in difficulty due to the failure of those ships behind her to properly follow up. This left her vulnerable to ''Mucius'', ''Tourville'' and the ships following them, with which she began a furious fusillade. However, ''Defence'' was not the only ship of the van to break the French line; minutes later George Cranfield Berkeley in HMS ''Marlborough'' executed Howe's manoeuvre perfectly, raking and then entangling his ship with ''Impétueux''.

In front of ''Marlborough'' the rest of the van had mixed success. HMS ''Bellerophon'' and HMS ''Leviathan'' were both still suffering the effects of their exertions earlier in the week and did not breach the enemy line. Instead they pulled along the near side of ''Éole'' and ''America'' respectively and brought them to close gunnery duels. Rear-Admiral Thomas Pasley of ''Bellerophon'' was an early casualty, losing a leg in the opening exchanges. HMS ''Royal Sovereign'', Graves's flagship, was less successful due to a miscalculation of distance that resulted in her pulling up too far from the French line and coming under heavy fire from her opponent ''Terrible''. In the time it took to engage ''Terrible'' more closely, ''Royal Sovereign'' suffered a severe pounding and Admiral Graves was badly wounded.

More disturbing to Lord Howe were the actions of HMS ''Russell'' and HMS ''Caesar''. ''Russell's'' captain John Willett Payne was criticised at the time for failing to get to grips with the enemy more closely and allowing her opponent ''Téméraire'' to badly damage her rigging in the early stages, although later commentators blamed damage received on 29 May for her poor start to the action. There were no such excuses, however, for Captain Anthony Molloy of ''Caesar'', who totally failed in his duty to engage the enemy. Molloy completely ignored Howe's signal and continued ahead as if the British battleline was following him rather than engaging the French fleet directly. ''Caesar'' did participate in a desultory exchange of fire with the leading French ship ''Trajan'' but her fire had little effect, while ''Trajan'' inflicted much damage to ''Caesar's'' rigging and was subsequently able to attack ''Bellerophon'' as well, roaming unchecked through the melee developing at the head of the line.

Centre

The centre of the two fleets was divided by two separate squadrons of the British line: the forward division under admirals Benjamin Caldwell and George Bowyer and the rear under Lord Howe. While Howe in ''Queen Charlotte'' was engaging the French closely, his subordinates in the forward division were less active. Instead of moving in on their opposite numbers directly, the forward division sedately closed with the French in line ahead formation, engaging in a long distance duel which did not prevent their opponents from harassing the embattled ''Defence'' just ahead of them. Of all the ships in this squadron only HMS ''Invincible'', under Thomas Pakenham, ranged close to the French lines. ''Invincible'' was badly damaged by her lone charge but managed to engage the larger ''Juste''. HMS ''Barfleur'' under Bowyer did later enter the action, but Bowyer was not present, having lost a leg in the opening exchanges. Howe and ''Queen Charlotte'' led the fleet by example, sailing directly at the French flagship ''Montagne''. Passing between ''Montagne'' and the next in line ''Vengeur du Peuple'', ''Queen Charlotte'' raked both and hauled up close to ''Montagne'' to engage in a close-range artillery battle. As she did so, ''Queen Charlotte'' also became briefly entangled with ''Jacobin'', and exchanged fire with her too, causing serious damage to both French ships. To the right of ''Queen Charlotte'', HMS ''Brunswick'' had initially struggled to join the action. Labouring behind the flagship, her captain John Harvey received a rebuke from Howe for the delay. Spurred by this signal, Harvey pushed his ship forward and almost outstripped ''Queen Charlotte'', blocking her view of the eastern half of the French fleet for a time and taking severe damage from French fire as she did so. Harvey hoped to run aboard ''Jacobin'' and support his admiral directly, but was not fast enough to reach her and so attempted to cut between ''Achille'' and ''Vengeur du Peuple''. This manoeuvre failed when ''Brunswick's'' anchors became entangled in ''Vengeur's'' rigging. Harvey'smaster

Master, master's or masters may refer to:

Ranks or titles

In education:

*Master (college), head of a college

*Master's degree, a postgraduate or sometimes undergraduate degree in the specified discipline

*Schoolmaster or master, presiding office ...

asked if ''Vengeur'' should be cut loose, to which Harvey replied "No; we have got her and we will keep her". The two ships swung so close to each other that ''Brunswick's'' crew could not open their gunports and had to fire through the closed lids, the ships battering each other from a distance of just a few feet.

Behind this combat, other ships of the centre division struck the French line, HMS ''Valiant'' under Thomas Pringle passing close to ''Patriote'' which pulled away, her crew suffering from contagion and unable to take their ship into battle. ''Valiant'' instead turned her attention on ''Achille'', which had already been raked by ''Queen Charlotte'' and ''Brunswick'', and badly damaged her before pressing on sail to join the embattled van division. HMS ''Orion'' under John Thomas Duckworth and HMS ''Queen'' under Admiral Alan Gardner both attacked the same ship, ''Queen'' suffering severely from the earlier actions in which her masts were badly damaged and her captain John Hutt mortally wounded. Both ships bore down on the French ''Northumberland'', which was soon dismasted and left attempting to escape on only the stump of a mast. ''Queen'' was too slow to engage ''Northumberland'' as closely as ''Orion'', and soon fell in with ''Jemmapes'', both ships battering each other severely.

Rear

Of the British rear ships, only two made a determined effort to break the French line. Admiral Hood's flagship HMS ''Royal George'' pierced it between ''Républicain'' and ''Sans Pareil'', engaging both closely, while HMS ''Glory'' came through the line behind ''Sans Pareil'' and threw herself into the melee as well. The rest of the British and French rearguard did not participate in this close combat; HMS ''Montagu'' fought a long range gunnery duel with ''Neptune'' which damaged neither ship severely, although the British captain James Montagu was killed in the opening exchanges, command devolving to Lieutenant Ross Donnelly.Donnelly, Sir Ross''

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

The ''Dictionary of National Biography'' (''DNB'') is a standard work of reference on notable figures from History of the British Isles, British history, published since 1885. The updated ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (''ODNB'') ...

'', J. K. Laughton and Andrew Lambert

Andrew David Lambert (born 31 December 1956) is a British naval historian, who since 2001 has been the Laughton Professor of Naval History in the Department of War Studies, King's College London.

Academic career

After completing his doctoral ...

, (subscription required), retrieved 10 May 2012 Next in line, HMS ''Ramillies'' ignored her opponent completely and sailed west, Captain Henry Harvey seeking ''Brunswick'', his brother's ship, in the confused action around ''Queen Charlotte''.

Three other British ships failed to respond to the signal from Howe, including HMS ''Alfred'' which engaged the French line at extreme range without noticeable effect, and Captain Charles Cotton

Charles Cotton (28 April 1630 – 16 February 1687) was an English poet and writer, best known for translating the work of Michel de Montaigne from French, for his contributions to ''The Compleat Angler'', and for the influential ''The Complea ...

in HMS ''Majestic'' who likewise did little until the action was decided, at which point he took the surrender of several already shattered French ships. Finally HMS ''Thunderer'' under Albemarle Bertie took no part in the initial action at all, standing well away from the British line and failing to engage the enemy despite the signal for close engagement hanging limply from her mainmast. The French rear ships were no less idle, with ''Entreprenant'' and ''Pelletier'' firing at any British ships in range but refusing to close or participate in the melees on either side. The French rear ship ''Scipion'' did not attempt to join the action either, but could not avoid becoming embroiled in the group around ''Royal George'' and ''Républicain'' and suffered severe damage.

Melee

Within an hour of their opening volleys the British and French lines were hopelessly confused, with three separate engagements being fought within sight of one another. In the van, ''Caesar'' had finally attempted to join the fight, only to have a vital spar shot away by ''Trajan'' which caused her to slip down the two embattled fleets without contributing significantly to the battle. ''Bellerophon'' and ''Leviathan'' were in the thick of the action, the outnumbered ''Bellerophon'' taking serious damage to her rigging. This left her unable to manoeuvre and in danger from her opponents, of which ''Eole'' also suffered severely. Captain William Johnstone Hope sought to extract his ship from her perilous position and called up support; the frigate HMS ''Latona'' under Captain Edward Thornbrough arrived to provide assistance. Thornbrough brought his small ship between the ships of the French battleline and opened fire on ''Eole'', helping to drive off three ships of the line and then towing ''Bellerophon'' to safety. ''Leviathan'', underLord Hugh Seymour

Vice-Admiral Lord Hugh Seymour (29 April 1759 – 11 September 1801) was a Royal Navy officer and politician who served in the American Revolutionary War, American War of Independence and French Revolutionary Wars. The fifth son of Francis Seymo ...

, had been more successful than ''Bellerophon'', her gunnery dismasting ''America'' despite receiving fire from ''Eole'' and ''Trajan'' in passing. ''Leviathan'' only left ''America'' after a two-hour duel, sailing at 11:50 to join ''Queen Charlotte'' in the centre.

''Russell'' had not broken the French line and her opponent ''Témeraire'' got the better of her, knocking away a topmast and escaping to windward with ''Trajan'' and ''Eole''. ''Russell'' then fired on several passing French ships before joining ''Leviathan'' in attacking the centre of the French line. ''Russell's'' boats also took the surrender of ''America'', her crew boarding the vessel to make her a prize (although later replaced by men from ''Royal Sovereign'') ''Royal Sovereign'' lost Admiral Graves to a serious wound and lost her opponent as well, as ''Terrible'' fell out of the line to windward and joined a growing collection of French ships forming a new line on the far side of the action. Villaret was leading this line in his flagship ''Montagne'', which had escaped from ''Queen Charlotte'', and it was ''Montagne'' which ''Royal Sovereign'' engaged next, pursuing her close to the new French line accompanied by ''Valiant'', and beginning a long-range action.

Behind ''Royal Sovereign'' was ''Marlborough'', inextricably tangled with ''Impétueux''. Badly damaged and on the verge of surrender, ''Impétueux'' was briefly reprieved when ''Mucius'' appeared through the smoke and collided with both ships. The three entangled ships continued exchanging fire for some time, all suffering heavy casualties with ''Marlborough'' and ''Impétueux'' losing all three of their masts. This combat continued for several hours. Captain Berkeley of ''Marlborough'' had to retire below with serious wounds, and command fell to Lieutenant John Monkton, who signalled for help from the frigates in reserve. Robert Stopford responded in HMS ''Aquilon'', which had the assignment of repeating signals, and towed ''Marlborough'' out of the line as ''Mucius'' freed herself and made for the regrouped French fleet to the north. ''Impétueux'' was in too damaged a state to move at all, and was soon seized by sailors from HMS ''Russell''.

Dismasted, ''Defence'' was unable to hold any of her various opponents to a protracted duel, and by 13:00 was threatened by the damaged ''Républicain'' moving from the east. Although ''Républicain'' later hauled off to join Villaret to the north, Gambier requested support for his ship from the fleet's frigates and was aided by HMS ''Phaeton'' under Captain William Bentinck. As ''Impétueux'' passed she fired on ''Phaeton'', to which Bentinck responded with several broadsides of his own. ''Invincible'', the only ship of the forward division of the British centre to engage the enemy closely, became embroiled in the confusion surrounding ''Queen Charlotte''. ''Invincible's'' guns drove ''Juste'' onto the broadside of ''Queen Charlotte'', where she was forced to surrender to Lieutenant Henry Blackwood

Vice-Admiral Sir Henry Blackwood, 1st Baronet (28 December 1770 – 13 December 1832), whose burial site and memorial are in Killyleagh Parish Church, was an Irish officer of the British Royal Navy.

Early life

Blackwood was the fourth son of ...

in a boat from ''Invincible''. Among the other ships of the division there were only minor casualties, although HMS ''Impregnable'' lost several yards and was only brought back into line by the quick reactions of two junior officers, Lieutenant Robert Otway and Midshipman Charles Dashwood.Otway, Sir Robert''

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

The ''Dictionary of National Biography'' (''DNB'') is a standard work of reference on notable figures from History of the British Isles, British history, published since 1885. The updated ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (''ODNB'') ...

'', J. K. Laughton, retrieved 2 January 2008

The conflict between ''Queen Charlotte'' and ''Montagne'' was oddly one-sided, the French flagship failing to make use of her lower-deck guns and consequently suffering extensive damage and casualties. ''Queen Charlotte'' in her turn was damaged by fire from nearby ships and was therefore unable to follow when ''Montagne'' set her remaining sails and slipped to the north to create a new focal point for the survivors of the French fleet. ''Queen Charlotte'' also took fire during the engagement from HMS ''Gibraltar'', under Thomas Mackenzie, which had failed to close with the enemy and instead fired at random into the smoke bank surrounding the flagship. Captain Sir Andrew Snape Douglas was seriously wounded by this fire. Following ''Montagnes escape, ''Queen Charlotte'' engaged ''Jacobin'' and ''Républicain'' as they passed, and was successful in forcing the surrender of ''Juste''. To the east of ''Queen Charlotte'', ''Brunswick'' and ''Vengeur du Peuple'' continued their bitter combat, locked together and firing main broadsides from point blank range. Captain Harvey of ''Brunswick'' was mortally wounded early in this action by langrage fire from ''Vengeur'', but refused to quit the deck, ordering more fire into his opponent.Harvey, John

The conflict between ''Queen Charlotte'' and ''Montagne'' was oddly one-sided, the French flagship failing to make use of her lower-deck guns and consequently suffering extensive damage and casualties. ''Queen Charlotte'' in her turn was damaged by fire from nearby ships and was therefore unable to follow when ''Montagne'' set her remaining sails and slipped to the north to create a new focal point for the survivors of the French fleet. ''Queen Charlotte'' also took fire during the engagement from HMS ''Gibraltar'', under Thomas Mackenzie, which had failed to close with the enemy and instead fired at random into the smoke bank surrounding the flagship. Captain Sir Andrew Snape Douglas was seriously wounded by this fire. Following ''Montagnes escape, ''Queen Charlotte'' engaged ''Jacobin'' and ''Républicain'' as they passed, and was successful in forcing the surrender of ''Juste''. To the east of ''Queen Charlotte'', ''Brunswick'' and ''Vengeur du Peuple'' continued their bitter combat, locked together and firing main broadsides from point blank range. Captain Harvey of ''Brunswick'' was mortally wounded early in this action by langrage fire from ''Vengeur'', but refused to quit the deck, ordering more fire into his opponent.Harvey, John''

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

The ''Dictionary of National Biography'' (''DNB'') is a standard work of reference on notable figures from History of the British Isles, British history, published since 1885. The updated ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (''ODNB'') ...

'', J. K. Laughton, retrieved 24 December 2007 ''Brunswick'' also managed to drive ''Achille'' off from her far side when the French ship attempted to intervene. ''Achille'', already damaged, was totally dismasted in the exchange and briefly surrendered, although her crew rescinded this when it became clear ''Brunswick'' was in no position to take possession. With her colours rehoisted, ''Achille'' then made what sail she could in an attempt to join Villaret to the north. It was not until 12:45 that the shattered ''Vengeur'' and ''Brunswick'' pulled apart, both largely dismasted and very battered. ''Brunswick'' was only able to return to the British side of the line after being supported by ''Ramillies'', while ''Vengeur'' was unable to move at all. ''Ramillies'' took ''Vengeur's'' surrender after a brief cannonade but was unable to board her and instead pursued the fleeing ''Achille'', which soon surrendered as well.

To the east, ''Orion'' and ''Queen'' forced the surrender of both ''Northumberland'' and ''Jemmappes'', although ''Queen'' was unable to secure ''Jemmappes'' and she had to be abandoned later. ''Queen'' especially was badly damaged and unable to make the British lines again, wallowing between the newly reformed French fleet and the British battleline along with several other shattered ships. ''Royal George'' and ''Glory'' had between them disabled ''Scipion'' and ''Sans Pareil'' in a bitter exchange, but were also too badly damaged themselves to take possession. All four ships were among those left drifting in the gap between the fleets.

French recovery

Villaret in ''Montagne'', having successfully broken contact with the British flagship and slipped away to the north, managed to gather 11 ships of the line around him and formed them up in a reconstituted battle squadron. At 11:30, with the main action drawing to a close, he began a recovery manoeuvre intended to lessen the tactical defeat his fleet had suffered. Aiming his new squadron at the battered ''Queen'', Villaret's attack created consternation in the British fleet, which was unprepared for a second engagement. However, discerning Villaret's intention, Howe also pulled his ships together to create a new force. His reformed squadron consisted of ''Queen Charlotte'', ''Royal Sovereign'', ''Valiant'', ''Leviathan'', ''Barfleur'', and ''Thunderer''. Howe deployed this squadron in defence of ''Queen'', and the two short lines engaged one another at a distance before Villaret abandoned his manoeuvre and hauled off to collect several of his own dismasted ships that were endeavouring to escape British pursuit. Villaret was subsequently joined by the battered ''Terrible'', which sailed straight through the dispersed British fleet to reach the French lines, and he also recovered the dismasted ''Scipion'', ''Mucius'', ''Jemmappes'', and ''Républicain''—all of which lay within reach of the unengaged British ships—before turning eastwards towards France. At this stage of the battle, Howe retired below and the British consolidation was left to his

Villaret in ''Montagne'', having successfully broken contact with the British flagship and slipped away to the north, managed to gather 11 ships of the line around him and formed them up in a reconstituted battle squadron. At 11:30, with the main action drawing to a close, he began a recovery manoeuvre intended to lessen the tactical defeat his fleet had suffered. Aiming his new squadron at the battered ''Queen'', Villaret's attack created consternation in the British fleet, which was unprepared for a second engagement. However, discerning Villaret's intention, Howe also pulled his ships together to create a new force. His reformed squadron consisted of ''Queen Charlotte'', ''Royal Sovereign'', ''Valiant'', ''Leviathan'', ''Barfleur'', and ''Thunderer''. Howe deployed this squadron in defence of ''Queen'', and the two short lines engaged one another at a distance before Villaret abandoned his manoeuvre and hauled off to collect several of his own dismasted ships that were endeavouring to escape British pursuit. Villaret was subsequently joined by the battered ''Terrible'', which sailed straight through the dispersed British fleet to reach the French lines, and he also recovered the dismasted ''Scipion'', ''Mucius'', ''Jemmappes'', and ''Républicain''—all of which lay within reach of the unengaged British ships—before turning eastwards towards France. At this stage of the battle, Howe retired below and the British consolidation was left to his Captain of the Fleet

Fleet captain (US) is a historic military title that was bestowed upon a naval officer who served as chief of staff to a flag officer. In the UK, a captain of the fleet could be appointed to assist an admiral when the admiral had ten or more shi ...