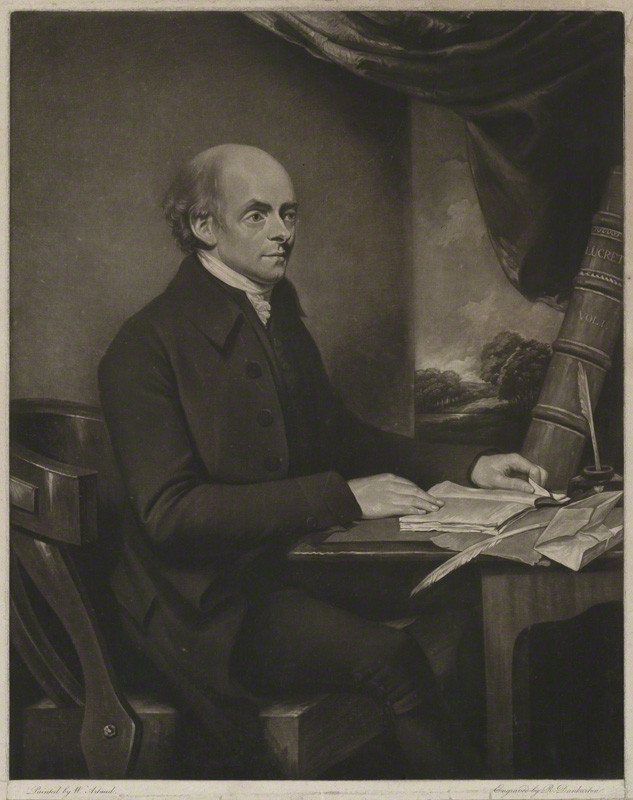

Gilbert Wakefield on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Gilbert Wakefield (1756–1801) was an English

Gilbert Wakefield (1756–1801) was an English

Evidences of Christianity

' 1793 *''The Spirit of Christianity, Compared with the Spirit of the Times in Great Britain'' (1794). There was an anonymous reply ''Vindiciae Britannicae'' in the Revolution Controversy, arguing in defence of the status quo in the British constitution, by "An Under Graduate" (identified as William Penn (1776–1845), son of Richard Penn, matriculated at

Gilbert Wakefield (1756–1801) was an English

Gilbert Wakefield (1756–1801) was an English scholar

A scholar is a person who is a researcher or has expertise in an academic discipline. A scholar can also be an academic, who works as a professor, teacher, or researcher at a university. An academic usually holds an advanced degree or a termina ...

and controversialist

Polemic ( , ) is contentious rhetoric intended to support a specific position by forthright claims and to undermine the opposing position. The practice of such argumentation is called polemics, which are seen in arguments on controversial to ...

. He moved from being a cleric and academic, into tutoring at dissenting academies, and finally became a professional writer and publicist. In a celebrated state trial, he was imprisoned for a pamphlet critical of government policy of the French Revolutionary Wars

The French Revolutionary Wars () were a series of sweeping military conflicts resulting from the French Revolution that lasted from 1792 until 1802. They pitted French First Republic, France against Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain, Habsb ...

; and died shortly after his release.

Early life and background

He was born 22 February 1756 inNottingham

Nottingham ( , East Midlands English, locally ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and Unitary authorities of England, unitary authority area in Nottinghamshire, East Midlands, England. It is located south-east of Sheffield and nor ...

, the third son of the Rev. George Wakefield, then rector of St Nicholas' Church, Nottingham but afterwards at Kingston-upon-Thames

Kingston upon Thames, colloquially known as Kingston, is a town in the Royal Borough of Kingston upon Thames, south-west London, England. It is situated on the River Thames, south-west of Charing Cross. It is an ancient market town, notable as ...

, and his wife Elizabeth. He was one of five brothers, who included George, a merchant in Manchester.

His father was from Rolleston, Staffordshire, and came to Cambridge in 1739 as a sizar

At Trinity College Dublin and the University of Cambridge, a sizar is an Undergraduate education, undergraduate who receives some form of assistance such as meals, lower fees or lodging during his or her period of study, in some cases in retur ...

. He had support in his education from the Hardinge family, of Melbourne, Derbyshire

Melbourne () is a market town and civil parish in South Derbyshire, England.

It was home to Thomas Cook, founder of Thomas Cook & Son, the eponymous travel agency, and has a street named after him. It is south of Derby and from the River Trent ...

, his patrons being Nicholas Hardinge and his physician brother. In his early career he was chaplain to Margaret Newton, in her own right 2nd Countess Coningsby. George Hardinge, son of Nicholas, after Gilbert's death pointed out that the living of Kingston passed to George Wakefield in 1769, under an Act of Parliament specifying presentations to chapels of the parish, only because he had used his personal influence with his uncle Charles Pratt, 1st Baron Camden the Lord Chancellor, and Jeremiah Dyson.

Education and Fellowship

Wakefield had some schooling in the Nottingham area, under Samuel Berdmore and then atWilford

Wilford is a village and former civil parish in the Nottingham district in the ceremonial county of Nottinghamshire, England. The village is to the northeast of Clifton, Nottinghamshire, Clifton, southwest of West Bridgford, northwest of Ruddi ...

under Isaac Pickthall. He then made good progress at Kingston Free School under Richard Wooddeson the elder (died 1774), father of Richard Wooddeson the jurist.

Wakefield was sent to university young, because Wooddeson was retiring from teaching. An offer came of a place at Christ Church, Oxford

Christ Church (, the temple or house, ''wikt:aedes, ædes'', of Christ, and thus sometimes known as "The House") is a Colleges of the University of Oxford, constituent college of the University of Oxford in England. Founded in 1546 by Henry V ...

, from the Rev. John Jeffreys (1718–1798); but his father turned it down. He went to Jesus College, Cambridge

Jesus College is a Colleges of the University of Cambridge, constituent college of the University of Cambridge. Jesus College was established in 1496 on the site of the twelfth-century Benedictine nunnery of St Radegund's Priory, Cambridge, St ...

on a scholarship founded by Robert Marsden: the Master Lynford Caryl was from Nottinghamshire, and a friend of his father. He matriculated in 1772, and graduated B.A. as second wrangler

At the University of Cambridge in England, a "Wrangler" is a student who gains first-class honours in the Mathematical Tripos competition. The highest-scoring student is the Senior Wrangler, the second highest is the Second Wrangler, and so on ...

in 1776. He was a Fellow of the college from 1776 to 1779, and was ordained deacon in the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the State religion#State churches, established List of Christian denominations, Christian church in England and the Crown Dependencies. It is the mother church of the Anglicanism, Anglican Christian tradition, ...

in 1778.

Wakefield associated with John Jebb and Robert Tyrwhitt. William Bennet, senior tutor of Emmanuel College, became a long-term friend from this time, as Wakefield put it in 1799, "amidst all the differences of opinion".

The Rev. George Wakefield died in 1776, aged 56. The situation of Gilbert's younger brother Thomas, then still an undergraduate at Jesus College but also ordained priest and a curate to his father at Kingston, was anomalous, at least in the view of George Hardinge. His younger brother Henry Hardinge, at this point signed up at Peterhouse

Peterhouse is the oldest Colleges of the University of Cambridge, constituent college of the University of Cambridge in England, founded in 1284 by Hugh de Balsham, Bishop of Ely. Peterhouse has around 300 undergraduate and 175 graduate stud ...

but yet to matriculate, became vicar of Kingston in 1778. Thomas Wakefield was at St Mary Magdalene, Richmond

St Mary Magdalene, Richmond, in the Anglican Diocese of Southwark, is a Grade II* listed parish church on Paradise Road, Richmond, London. The church, dedicated to Jesus' companion Mary Magdalene, was built in the early 16th century but has be ...

for the rest of his life, dying in 1806; and Gilbert was buried there. In the first edition of his autobiography, Gilbert was critical of Hardinge's legal moves to dislodge Thomas from this Richmond chapel, to which the presentation had been with his father (under Act of Parliament). The matter ended up in the Court of Common Pleas, which ruled for Thomas Wakefield. The 1802 edition tacitly omitted slurs to which Hardinge objected. Hardinge blamed an unnamed malevolent person, and his parting shot was that Thomas as a boy "had been intended for trade".

Curacies

In 1778, Wakefield was a curate atSt Mary's Church, Stockport

St Mary's Church is the oldest parish church in the town of Stockport, Greater Manchester, England. It stands in Churchgate overlooking the market place. The church is recorded in the National Heritage List for England as a designated Grade ...

, under the Rev. John Watson, an antiquarian. He was interested in becoming head of Brewood School, but baulked at again signing up to the 39 Articles.

Wakefield then was a curate in Liverpool

Liverpool is a port City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. It is situated on the eastern side of the River Mersey, Mersey Estuary, near the Irish Sea, north-west of London. With a population ...

. There he preached on abolitionism

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the political movement to end slavery and liberate enslaved individuals around the world.

The first country to fully outlaw slavery was France in 1315, but it was later used in its colonies. ...

, and against privateering

A privateer is a private person or vessel which engages in commerce raiding under a commission of war. Since Piracy, robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sover ...

, which was badly received at this time in the Anglo-French War (1778–1783)

The Anglo-French War, also known as the War of 1778 or the Bourbon War in Britain, was a military conflict fought between France and Great Britain, sometimes with their respective allies, between 1778 and 1783. As a consequence, Great Britain wa ...

. He commented in his autobiography that Liverpool was the "headquarters" of the Atlantic slave trade

The Atlantic slave trade or transatlantic slave trade involved the transportation by slave traders of Slavery in Africa, enslaved African people to the Americas. European slave ships regularly used the triangular trade route and its Middle Pass ...

, that the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was the armed conflict that comprised the final eight years of the broader American Revolution, in which Am ...

with the French war impeded slaving, and the upsurge with privateering, which he saw as aggravating war, was a consequence.

From 1778, Wakefield began to question the scriptural foundation of the orthodox teaching of the Church of England; and he expressed political views by modifying the language in prayers he read in Liverpool against the American revolutionaries. He married in 1779, bringing his fellowship to an end.

Dissenting tutor

Wakefield left the ministry, and in mid-1779 became classical tutor at Warrington Academy, recommended by Jebb. The Academy closed in 1783, in Wakefield's view from financial troubles. He commented also that at least a third of the students during his time there were from Church of England families, rather than being from a dissenting background. Wakefield's theology had become a nonconformingUnitarianism

Unitarianism () is a Nontrinitarianism, nontrinitarian sect of Christianity. Unitarian Christians affirm the wikt:unitary, unitary God in Christianity, nature of God as the singular and unique Creator deity, creator of the universe, believe that ...

. John Hunt in his ''Religious Thought in England'' classed him with Edward Evanson

Edward Evanson (21 April 173125 September 1805) was a controversial English clergyman.

Life

He was born at Warrington, Lancashire. After graduating at Emmanuel College, Cambridge and taking holy orders, he spent several years as curate at Mitcham ...

, among prominent Unitarians leaving the Church of England, and as having in common that "they can scarcely be regarded as representing anybody but themselves". He had attracted the attention of Theophilus Lindsey

Theophilus Lindsey (20 June 1723 O.S.3 November 1808) was an English theologian and clergyman who founded the first avowedly Unitarian congregation in the country, at Essex Street Chapel. Lindsey's 1774 revised prayer book based on Samuel C ...

; who made qualifications of his approval of someone he considered a "true scholar". In 1783 Lindsey explained to William Turner his reasons for not supporting Wakefield as a replacement for the ailing William Leechman at Glasgow. Wakefield at Warrington still attended services of the Church of England; and he hoped "time will mellow his dispositions, and lessen the high opinion he has of himself".

Robert Malthus

Thomas Robert Malthus (; 13/14 February 1766 – 29 December 1834) was an English economist, cleric, and scholar influential in the fields of political economy and demography.

In his 1798 book ''An Essay on the Principle of Population'', Mal ...

, a pupil of Wakefield at the Academy, continued with him for a year after the Warrington closure. Residing at Bramcote

Bramcote (, ) is a suburban village and former civil parish in the Borough of Broxtowe, Broxtowe district of Nottinghamshire, England, between Stapleford, Nottinghamshire, Stapleford and Beeston, Nottinghamshire, Beeston. It is in the parliame ...

outside Nottingham, and then in Richmond, Surrey

Richmond is a town in south-west London,The London Government Act 1963 (c.33) (as amended) categorises the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames as an Outer London borough. Although it is on both sides of the River Thames, the Boundary Commis ...

where his brother Thomas was at St Mary Magdalene's chapel, Wakefield found no more students. At the chapel, on the day in 1784 appointed for a thanksgiving for the end of the American war, he preached an anti-colonial sermon. It was quoted by Thomas Clarkson

Thomas Clarkson (28 March 1760 – 26 September 1846) was an English abolitionist, and a leading campaigner against the slave trade in the British Empire. He helped found the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade (also known ...

in his history of abolitionism, together with accounts of two contemporary works, the ''Essays, Historical and Moral'' of George Gregory, and the ''Essay on the Treatment and Conversion of the African Slaves in the British Sugar Colonies'' by James Ramsay.

Wakefield lived in Nottingham from 1784 to 1790. Here he was able to find private pupils. One was Robert Hibbert, from a slave-holding family in Jamaica

Jamaica is an island country in the Caribbean Sea and the West Indies. At , it is the third-largest island—after Cuba and Hispaniola—of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean. Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, west of Hispaniola (the is ...

, who went on to Cambridge. He was a Unitarian, on good terms with William Frend, and founded the Hibbert Trust. He was also at odds with his cousin George Hibbert

George Hibbert (13 January 1757 – 8 October 1837) was an English merchant, politician and ship-owner. Alongside fellow slaver Robert Milligan (merchant), Robert Milligan, he was also one of the principals of the West India Dock Company which ...

. George Hibbert was Wakefield's patron, whom Wakefield thanked in his autobiography; but it was Robert who gave financial support when he was imprisoned.

In 1790, Wakefield was appointed to the New College, Hackney, where Thomas Belsham

Thomas Belsham (26 April 175011 November 1829) was an English Unitarian minister.

Life

Belsham was born in Bedford, England, and was the elder brother of William Belsham, the English political writer and historian. He was educated at the di ...

had been recruited the year before, and Joseph Priestley

Joseph Priestley (; 24 March 1733 – 6 February 1804) was an English chemist, Unitarian, Natural philosophy, natural philosopher, English Separatist, separatist theologian, Linguist, grammarian, multi-subject educator and Classical libera ...

arrived the year after. It was a contentious trio of hirings. Wakefield's application was strengthened by a character reference from George Walker, minister at the High Pavement Chapel in Nottingham and a friend.

Among Wakefield's pupils at Hackney was John Jones. His time at the New College was short: he left in 1791, on the grounds of disillusion with public worship. The subsequent controversy showed Wakefield in "one of the most extreme positions" maintained in Rational Dissent.

Writer and pamphleteer

Wakefield from then on lived by his pen, and was a prolific author. He was a passionate defender of the French Revolution. The final issue, in 1798, of the '' Anti-Jacobin'' contained a satirical poem "New Morality", calling on opposition newspapers, poets and radicals includingJohn Thelwall

John Thelwall (27 July 1764 – 17 February 1834) was a radical British orator, writer, political reformer, journalist, poet, elocutionist and speech therapist.

, Priestley and Wakefield to "praise Lepaux", i.e. Louis Marie de La Révellière-Lépeaux

Louis Marie de La Révellière-Lépeaux (24 August 1753 – 24 March 1824) was a deputy to the National Convention during the French Revolution. He later served as a prominent leader of the French Directory.

Life

He was born at Montaigu (Vend� ...

, a leader of the French Directory

The Directory (also called Directorate; ) was the system of government established by the Constitution of the Year III, French Constitution of 1795. It takes its name from the committee of 5 men vested with executive power. The Directory gov ...

.

William Burdon replied to a remark of Thomas James Mathias:

Whenever I think of the name of Gilbert Wakefield, and look at the list of his works, (for I would not undertake to read them ''all''), I feel alternate sorrow and indignation.Burdon wrote:

To the name and character of Gilbert Wakefield, I am desirous to shew every possible respect, as a zealous, though sometimes an imprudent defender of the rights of human nature.In 1794, Wakefield expressed admiration for the Manchester radical Thomas Walker. Acquainted socially, they were both guests at a London radical dinner given on 3 January 1795 by Thomas Northmore, others there being John Disney,

William Godwin

William Godwin (3 March 1756 – 7 April 1836) was an English journalist, political philosopher and novelist. He is considered one of the first exponents of utilitarianism and the first modern proponent of anarchism. Godwin is most famous fo ...

, Thomas Brand Hollis and "Bard" Iolo Morganwg

Edward Williams, better known by his bardic name Iolo Morganwg (; 10March 174718December 1826), was a Welsh antiquarian, poet and collector.Jones, Mary (2004)"Edward Williams/Iolo Morganwg/Iolo Morgannwg" From ''Jones' Celtic Encyclopedia''. R ...

.

Of the 1798 quickly-written wartime squib that provoked a prosecution of Wakefield, Marilyn Butler

Marilyn Speers Butler, Lady Butler, FRSA, FRSL, Fellow of the British Academy, FBA (''née'' Evans; 11 February 1937 – 11 March 2014) was a British literary criticism, literary critic. She was King Edward VII Professor of English Literature at ...

wrote:

Very lively and very impertinent, Wakefield's pamphlet exemplified both the ability of radical writers to make a point, and their alienation from the temper of the mass of the British people in a national crisis.

Pamphlets of the 1790s

*''An Enquiry into the Expediency and Propriety of Public or Social Worship'' (1791). There were replies from Joseph Priestley, Anna Barbauld, Eusebia ( Mary Hays); John Disney, James Wilson (M.A. Glasgow) of Stockport;John Bruckner

John Bruckner (also Jean or Johannes) (31 December 1726 – 12 May 1804) was a Dutch Lutheran minister and author, who settled in Norwich, England.

Life

He was born on the Land van Cadzand (locally Kezand), then a small island in Zeeland. He was ...

; Thomas Jervis and others. Wakefield answered Priestley.

* Evidences of Christianity

' 1793 *''The Spirit of Christianity, Compared with the Spirit of the Times in Great Britain'' (1794). There was an anonymous reply ''Vindiciae Britannicae'' in the Revolution Controversy, arguing in defence of the status quo in the British constitution, by "An Under Graduate" (identified as William Penn (1776–1845), son of Richard Penn, matriculated at

St John's College, Cambridge

St John's College, formally the College of St John the Evangelist in the University of Cambridge, is a Colleges of the University of Cambridge, constituent college of the University of Cambridge, founded by the House of Tudor, Tudor matriarch L ...

1795.).

*''Remarks on the General Orders of the Duke of York to his Army on June 7, 1794'' (1794)

*''An Examination of The Age of Reason: or an investigation of true and fabulous theology by Thomas Paine'' (1794)

*''A Reply to the Letter of Edmund Burke, Esq. to a Noble Lord'' (1796)

*''A Letter to William Wilberforce, Esq. on the Subject of His Late Publication'' (1797). Reply from the point of view of rational dissent to William Wilberforce

William Wilberforce (24 August 1759 – 29 July 1833) was a British politician, philanthropist, and a leader of the movement to abolish the Atlantic slave trade. A native of Kingston upon Hull, Yorkshire, he began his political career in 1780 ...

's ''A Practical View of the Prevailing Religious System of Professed Christians, in the Middle and Higher Classes in this Country, Contrasted with Real Christianity'' (1797). There were related replies from Thomas Belsham and Joshua Toulmin

Joshua Toulmin ( – 23 July 1815) of Taunton, England was a noted theologian and a serial Dissenting minister of Presbyterian (1761–1764), Baptist (1765–1803), and then Unitarian (1804–1815) congregations. Toulmin's sympathy for bot ...

. The nonconformist John Watkins wrote in support of Wilberforce, as did the Anglican Rev. George Hutton in 1798.

*''A letter to Sir J. Scott, his Majesty's Attorney-General, on the subject of a late Trial at Guildhall'' (1798). Addressed to Sir John Scott. On the trial of the radical booksellers Joseph Johnson and J. S. Jordan for seditious libel, and liberty of the press according to commentary in the '' Analytical Review''.

*''The Defence of Gilbert Wakefield, B.A.'' (1799)

Imprisonment and death

The controversial pamphlet ''A Reply to some Parts of the Bishop of Landaff's Address'' (1798) saw both Wakefield and his publisher, Joseph Johnson, taken to court forseditious libel

Seditious libel is a criminal offence under common law of printing written material with seditious purposethat is, the purpose of bringing contempt upon a political authority. It remains an offence in Canada but has been abolished in England and ...

. A work alluding to the concentration of poverty in the area centred on Hackney, it was written in response to ''An Address to the People of Great Britain'' (1798), by Richard Watson, Bishop of Llandaff

The Bishop of Llandaff is the Ordinary (officer), ordinary of the Church in Wales Diocese of Llandaff.

Area of authority

The diocese covers most of the County of Glamorgan. The bishop's cathedra, seat is in the Llandaff Cathedral, Cathedral Chu ...

. Watson argued that national taxes should be raised to pay for the war against France and to reduce the national debt.

For selling the ''Reply'', Johnson was fined £50 and sentenced to six months imprisonment in King's Bench Prison

The King's Bench Prison was a prison in Southwark, south London, England, from the Middle Ages until it closed in 1880. It took its name from the King's Bench court of law in which cases of defamation, bankruptcy and other misdemeanours were he ...

in February 1799. Later in the year, Wakefield appeared before Lord Kenyon in the Court of King's Bench

The Court of King's Bench, formally known as The Court of the King Before the King Himself, was a court of common law in the English legal system. Created in the late 12th to early 13th century from the '' curia regis'', the King's Bench initi ...

, conducting his own defence, with Sir John Scott. His trial followed on directly after that of the bookseller John Cuthell, with the same jury. Much of the prosecution case was read from the ''Reply''. Wakefield made a systemic and personalised attack on the lack of justice in the court and process. He had checked the pamphlet for libellous content with a barrister. The judge summed up in support of Scott, and the jury returned a guilty verdict without retiring.

Wakefield was imprisoned in Dorchester gaol for two years for seditious libel. Among his visitors there was Robert Southey

Robert Southey (; 12 August 1774 – 21 March 1843) was an English poet of the Romantic poetry, Romantic school, and Poet Laureate of the United Kingdom, Poet Laureate from 1813 until his death. Like the other Lake Poets, William Wordsworth an ...

in 1801. He was released from prison on 29 May 1801, and died in Hackney on 9 September 1801, a victim of typhus fever

Typhus, also known as typhus fever, is a group of infectious diseases that include epidemic typhus, scrub typhus, and murine typhus. Common symptoms include fever, headache, and a rash. Typically these begin one to two weeks after exposure ...

. His library was put up for auction by Leigh, Sotherby & Co. in March 1802.

Scholarship

''A new translation of those parts only of the New Testament, which are wrongly translated in our common version'' (1789) was followed in 1791 by Wakefield's ''Translation of the New Testament, with Notes,'' in three volumes. In his memoirs Wakefield records that the work was laborious, particularly in the comparison of the Oriental versions with theReceived Text

The (Latin for 'received text') is the succession of printed Greek New Testament texts starting with Erasmus' ''Novum Instrumentum omne'' (1516) and including the editions of Robert Estienne, Stephanus, Theodore Beza, Beza, the House of Elzevir ...

; but was "much more profitable to me than all my other publications put together". A revised edition followed in 1795.

Wakefield also published editions of various classical writers, and among his theological writings are ''Early Christian Writers on the Person of Christ'' (1784), ''Silva Critica'' (1789–95), and illustrations of the Scriptures.

Memoirs and letters

* Autobiography: ''Memoirs of the life of Gilbert Wakefield'' 1792 - 405 pages * Correspondence:, ed. Charles James Fox ''Correspondence of the late Gilbert Wakefield, B. A.'' 1813Family

Wakefield married in 1779 Anne Watson (died 1819), niece of the incumbent John Watson at Stockport St Mary where he had been a curate. They had five sons and two daughters. *George (born c.1780), the eldest son, married in 1816 Anne Bowness, daughter of the Rev. William Bowness. He worked as an ordnance storekeeper in Kingston, Upper Canada, and died in 1837 atBarnstaple

Barnstaple ( or ) is a river-port town and civil parish in the North Devon district of Devon, England. The town lies at the River Taw's lowest crossing point before the Bristol Channel. From the 14th century, it was licensed to export wool from ...

, aged 57.

*Gilbert (baptised 1790 in Nottingham)

*Henry (1793–1861), third son, married in 1817 Harriet Pomeroy, daughter of Thomas Pomeroy. He was a surgeon, beginning as a pupil in Knutsford

Knutsford () is a market town and civil parish in the Cheshire East district, in Cheshire, England; it is located south-west of Manchester, north-west of Macclesfield and south-east of Warrington. The population of the parish at the 2021 Uni ...

of Peter Holland, father of Sir Henry Holland. He was on the continent after Waterloo, where his brother George was serving. He was surgeon to the county prisons from 1830.

*Robert, youngest surviving son, died in 1866 at age 70.

*Alfred, who died while his father was in prison.

*Anne (died 1821) married Charles Rochemont Aikin, and was mother of Anna Letitia Le Breton

Anna Letitia Le Breton ( Aikin; 30 June 1808 – 29 September 1885) was an English author. She was best known for publishing the memoirs of her great-aunt, the poet Anna Laetitia Barbauld as well as her aunt, the writer Lucy Aikin.

Early year ...

.

*Elizabeth (died 1811), younger daughter, married in 1809 Francis Wakefield the younger.

Their daughter Anne, in poor health, went to stay with Peter Crompton and his wife at Eton House, on the edge of Liverpool, shortly before Gilbert was imprisoned. George, the eldest son, went to Dorchester Grammar school, under Henry John Richman who was on good terms with Wakefield. At this time William Shepherd took care of his younger brother Gilbert. One of the daughters, to whom Wakefield's gaoler's son had been paying unwelcome attentions, went to stay with William Roscoe

William Roscoe (8 March 175330 June 1831) was an English banker, lawyer, and briefly a Member of Parliament. He is best known as one of England's first abolitionists, and as the author of the poem for children '' The Butterfly's Ball, and th ...

.

See also

* Hardy progeny of the NorthReferences

External links

* * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Wakefield, Gilbert 1756 births 1801 deaths People from Nottingham Alumni of Jesus College, Cambridge Second Wranglers Dissenting academy tutors