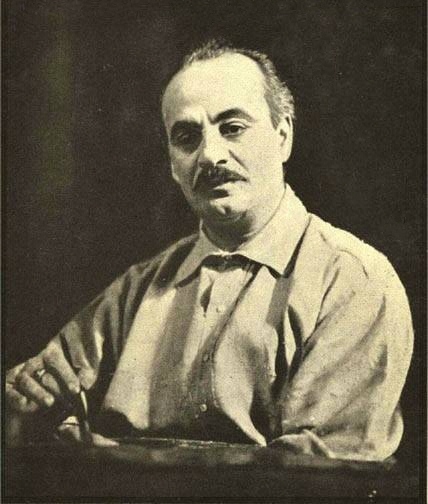

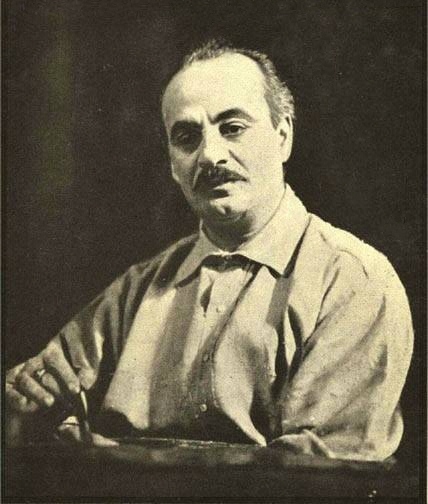

Gibran Painted By Howayek on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Gibran Khalil Gibran (January 6, 1883 – April 10, 1931), usually referred to in English as Kahlil Gibran, was a Lebanese-American writer, poet and

Kamila and her children settled in Boston's South End, at the time the second-largest Syrian-Lebanese-American community in the United States. Gibran entered the Josiah Quincy School on September 30, 1895. School officials placed him in a special class for immigrants to learn English. His name was registered using the anglicized spelling 'Ka''h''lil Gibran'. His mother began working as a seamstress peddler, selling lace and linens that she carried from door-to-door. His half-brother Boutros opened a shop. Gibran also enrolled in an art school at Denison House, a nearby

Kamila and her children settled in Boston's South End, at the time the second-largest Syrian-Lebanese-American community in the United States. Gibran entered the Josiah Quincy School on September 30, 1895. School officials placed him in a special class for immigrants to learn English. His name was registered using the anglicized spelling 'Ka''h''lil Gibran'. His mother began working as a seamstress peddler, selling lace and linens that she carried from door-to-door. His half-brother Boutros opened a shop. Gibran also enrolled in an art school at Denison House, a nearby

Gibran held the first art exhibition of his drawings in January 1904 in Boston at Day's studio. During this exhibition, Gibran met Mary Haskell, the headmistress of a girls' school in the city, nine years his senior. The two formed a friendship that lasted the rest of Gibran's life. Haskell would spend large sums of money to support Gibran and would also edit all of his English writings. The nature of their romantic relationship remains obscure; while some biographers assert the two were lovers but never married because Haskell's family objected, other evidence suggests that their relationship was never physically consummated. Gibran and Haskell were engaged briefly between 1910 and 1911. According to Joseph P. Ghougassian, Gibran had proposed to her "not knowing how to repay back in gratitude to Miss Haskell," but Haskell called it off, making it "clear to him that she preferred his friendship to any burdensome tie of marriage.". Haskell would later marry Jacob Florance Minis in 1926, while remaining Gibran's close friend, patroness and benefactress, and using her influence to advance his career.

It was in 1904 also that Gibran met Amin al-Ghurayyib, editor of ''Al-Mohajer'' ('The Emigrant'), where Gibran started to publish articles. In 1905, Gibran's first published written work was ''A Profile of the Art of Music'', in Arabic, by ''Al-Mohajer''s printing department in New York City. His next work, ''Nymphs of the Valley'', was published the following year, also in Arabic. On January 27, 1908, Haskell introduced Gibran to her friend writer

Gibran held the first art exhibition of his drawings in January 1904 in Boston at Day's studio. During this exhibition, Gibran met Mary Haskell, the headmistress of a girls' school in the city, nine years his senior. The two formed a friendship that lasted the rest of Gibran's life. Haskell would spend large sums of money to support Gibran and would also edit all of his English writings. The nature of their romantic relationship remains obscure; while some biographers assert the two were lovers but never married because Haskell's family objected, other evidence suggests that their relationship was never physically consummated. Gibran and Haskell were engaged briefly between 1910 and 1911. According to Joseph P. Ghougassian, Gibran had proposed to her "not knowing how to repay back in gratitude to Miss Haskell," but Haskell called it off, making it "clear to him that she preferred his friendship to any burdensome tie of marriage.". Haskell would later marry Jacob Florance Minis in 1926, while remaining Gibran's close friend, patroness and benefactress, and using her influence to advance his career.

It was in 1904 also that Gibran met Amin al-Ghurayyib, editor of ''Al-Mohajer'' ('The Emigrant'), where Gibran started to publish articles. In 1905, Gibran's first published written work was ''A Profile of the Art of Music'', in Arabic, by ''Al-Mohajer''s printing department in New York City. His next work, ''Nymphs of the Valley'', was published the following year, also in Arabic. On January 27, 1908, Haskell introduced Gibran to her friend writer

In 1912, the poetic

In 1912, the poetic

While most of Gibran's early writings had been in Arabic, most of his work published after 1918 was in English. Such was '' The Madman'', Gibran's first book published by

While most of Gibran's early writings had been in Arabic, most of his work published after 1918 was in English. Such was '' The Madman'', Gibran's first book published by

''Sand and Foam'' was published in 1926, and ''Jesus, the Son of Man'' in 1928. At the beginning of 1929, Gibran was diagnosed with an

''Sand and Foam'' was published in 1926, and ''Jesus, the Son of Man'' in 1928. At the beginning of 1929, Gibran was diagnosed with an  Gibran had expressed the wish that he be buried in Lebanon. His body lay temporarily at Mount Benedict Cemetery in Boston before it was taken on July 23 to

Gibran had expressed the wish that he be buried in Lebanon. His body lay temporarily at Mount Benedict Cemetery in Boston before it was taken on July 23 to

According to Ghougassian, the works of English poet

According to Ghougassian, the works of English poet

Ages of Women by Kahlil Gibran - Soumaya.jpg, ''The Ages of Women'', 1910 (

Gibran Museum

Bsharri, Lebanon

Online copies of texts by Gibran

Kahlil Gibran: Profile and Poems on Poets.org

BBC World Service: "The Man Behind the Prophet"

The Kahlil Gibran Collective

website includin

in ''The New York Times'' Archives {{DEFAULTSORT:Gibran, Kahlil 20th-century American novelists 20th-century American painters 20th-century American poets 20th-century American short story writers 20th-century Christian mystics 20th-century Lebanese painters 20th-century Lebanese poets 20th-century painters from the Ottoman Empire 20th-century poets from the Ottoman Empire American Arabic-language poets Arab-American writers Académie Julian alumni American Christian mystics Cultural history of Boston Exophonic writers Lebanese novelists Lebanese short story writers Mahjar Novelists from the Ottoman Empire People from Bsharri Symbolist painters Symbolist poets Writers who illustrated their own writing Deaths from cirrhosis Alcohol-related deaths in New York City Tuberculosis deaths in New York (state) 20th-century deaths from tuberculosis 1883 births 1931 deaths

visual artist

The visual arts are art forms such as painting, drawing, printmaking, sculpture, ceramics (art), ceramics, photography, video, image, filmmaking, design, crafts, and architecture. Many artistic disciplines such as performing arts, conceptual a ...

; he was also considered a philosopher, although he himself rejected the title. He is best known as the author of '' The Prophet'', which was first published in the United States in 1923 and has since become one of the best-selling books of all time, having been translated into more than 100 languages.

Born in Bsharri

Bsharri ( ''Bšarrī''; also romanized ''Becharre'', ''Bcharre'', ''Bsharre'', ''Bcharre Al Arz'') is a Lebanese town located in the district of the same name, North Governorate, situated at altitudes between and . Bsharri is the location o ...

, a village of the Ottoman-ruled Mount Lebanon Mutasarrifate

The Mount Lebanon Mutasarrifate (1861–1918, ; ) was one of the Ottoman Empire's subdivisions following the 19th-century Tanzimat reform. After 1861, there existed an autonomous Mount Lebanon with a Christian Mutasarrif (governor), which had be ...

to a Maronite Christian

Lebanese Maronite Christians (; ) refers to Lebanese people who are members of the Maronite Church in Lebanon, the largest Christian body in the country. The Lebanese Maronite population is concentrated mainly in Mount Lebanon and East Beir ...

family, young Gibran immigrated with his mother and siblings to the United States in 1895. As his mother worked as a seamstress, he was enrolled at a school in Boston

Boston is the capital and most populous city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Massachusetts in the United States. The city serves as the cultural and Financial centre, financial center of New England, a region of the Northeas ...

, where his creative abilities were quickly noticed by a teacher who presented him to photographer and publisher F. Holland Day

Fred Holland Day (July 23, 1864 – November 23, 1933) was an American photographer and publisher. He was prominent in literary and photography circles in the late nineteenth century and was a leading Pictorialist. He was an early and vocal ...

. Gibran was sent back to his native land by his family at the age of fifteen to enroll at the Collège de la Sagesse

The Collège de la Sagesse () is a Lebanese major national and Catholic school founded in 1875 by the Maronite archbishop of Beirut at the time, Joseph Debs who laid the first stone of the original building. The school originally known as l'É ...

in Beirut

Beirut ( ; ) is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Lebanon. , Greater Beirut has a population of 2.5 million, just under half of Lebanon's population, which makes it the List of largest cities in the Levant region by populatio ...

. Returning to Boston upon his youngest sister's death in 1902, he lost his older half-brother and his mother the following year, seemingly relying afterwards on his remaining sister's income from her work at a dressmaker's shop for some time.

In 1904, Gibran's drawings were displayed for the first time at Day's studio in Boston, and his first book in Arabic was published in 1905 in New York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

. With the financial help of a newly met benefactress, Mary Haskell, Gibran studied art in Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

from 1908 to 1910. While there, he came in contact with Syrian political thinkers promoting rebellion in Ottoman Syria after the Young Turk Revolution

The Young Turk Revolution (July 1908; ) was a constitutionalist revolution in the Ottoman Empire. Revolutionaries belonging to the Internal Committee of Union and Progress, an organization of the Young Turks movement, forced Sultan Abdul Hamid II ...

; some of Gibran's writings, voicing the same ideas as well as anti-clericalism

Anti-clericalism is opposition to clergy, religious authority, typically in social or political matters. Historically, anti-clericalism in Christian traditions has been opposed to the influence of Catholicism. Anti-clericalism is related to secul ...

, would eventually be banned by the Ottoman authorities. In 1911, Gibran settled in New York, where his first book in English, '' The Madman'', was published by Alfred A. Knopf

Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. () is an American publishing house that was founded by Blanche Knopf and Alfred A. Knopf Sr. in 1915. Blanche and Alfred traveled abroad regularly and were known for publishing European, Asian, and Latin American writers ...

in 1918, with writing of ''The Prophet'' or ''The Earth Gods

''The Earth Gods'' is a literary work written by poet and philosopher Kahlil Gibran. It was originally published in 1931, also the year of the author's death. The story is structured as a dialogue between three unnamed earth gods, only referred t ...

'' also underway. His visual artwork was shown at Montross Gallery in 1914, and at the galleries of M. Knoedler & Co. in 1917. He had also been corresponding remarkably with May Ziadeh

May Elias Ziadeh ( ; , ; 11 February 1886 – 17 October 1941) was a Palestinians, Palestinian-Lebanese people, Lebanese Maronite poet, essayist, and translator, who wrote many different works both in Arabic language, Arabic and in French la ...

since 1912. In 1920, Gibran re-founded the Pen League

The Mahjar (, one of its more literal meanings being "the Arabs, Arab diaspora") was a movement related to neo-romanticism, Romanticism migrant literature, migrant literary literary movement, movement started by Arabic-speaking writers who had emig ...

with fellow Mahjar

The Mahjar (, one of its more literal meanings being "the Arab diaspora") was a movement related to Romanticism migrant literary movement started by Arabic-speaking writers who had emigrated to the Americas from Ottoman-ruled Lebanon, Syria and ...

i poets. By the time of his death at the age of 48 from cirrhosis

Cirrhosis, also known as liver cirrhosis or hepatic cirrhosis, chronic liver failure or chronic hepatic failure and end-stage liver disease, is a chronic condition of the liver in which the normal functioning tissue, or parenchyma, is replaced ...

and incipient tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB), also known colloquially as the "white death", or historically as consumption, is a contagious disease usually caused by ''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can al ...

in one lung, he had achieved literary fame on "both sides of the Atlantic Ocean", and ''The Prophet'' had already been translated into German and French. His body was transferred to his birth village of Bsharri (in present-day Lebanon), to which he had bequeathed all future royalties on his books, and where a museum

A museum is an institution dedicated to displaying or Preservation (library and archive), preserving culturally or scientifically significant objects. Many museums have exhibitions of these objects on public display, and some have private colle ...

dedicated to his works now stands.

In the words of Suheil Bushrui

Suheil Badi Bushrui (; September 14, 1929 – September 2, 2015) was a Palestinian professor, author, poet, critic, translator, and peace maker.

He was a prominent scholar in regard to the life and works of the Lebanese-American author and poet ...

and Joe Jenkins, Gibran's life was "often caught between Nietzschean

Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900) developed his philosophy during the late 19th century. He owed the awakening of his philosophical interest to reading Arthur Schopenhauer's ''Die Welt als Wille und Vorstellung'' (''The World as Will and Represe ...

rebellion, Blakean pantheism

Pantheism can refer to a number of philosophical and religious beliefs, such as the belief that the universe is God, or panentheism, the belief in a non-corporeal divine intelligence or God out of which the universe arisesAnn Thomson; Bodies ...

and Sufi

Sufism ( or ) is a mysticism, mystic body of religious practice found within Islam which is characterized by a focus on Islamic Tazkiyah, purification, spirituality, ritualism, and Asceticism#Islam, asceticism.

Practitioners of Sufism are r ...

mysticism

Mysticism is popularly known as becoming one with God or the Absolute (philosophy), Absolute, but may refer to any kind of Religious ecstasy, ecstasy or altered state of consciousness which is given a religious or Spirituality, spiritual meani ...

." Gibran discussed different themes in his writings and explored diverse literary forms. Salma Khadra Jayyusi

Salma Khadra Jayyusi (; 16 April 1925 – 20 April 2023) was a Palestinian poet, writer, translator and anthologist. She was the founder and director of the Project of Translation from Arabic (PROTA), which aims to provide translation of Arabic ...

has called him "the single most important influence on Arabic poetry

Arabic poetry ( ''ash-shi‘r al-‘arabīyy'') is one of the earliest forms of Arabic literature. Pre-Islamic Arabic poetry contains the bulk of the oldest poetic material in Arabic, but Old Arabic inscriptions reveal the art of poetry existe ...

and literature

Literature is any collection of Writing, written work, but it is also used more narrowly for writings specifically considered to be an art form, especially novels, Play (theatre), plays, and poetry, poems. It includes both print and Electroni ...

during the first half of he twentieth

He or HE may refer to:

Language

* He (letter), the fifth letter of the Semitic abjads

* He (pronoun), a pronoun in Modern English

* He (kana), one of the Japanese kana (へ in hiragana and ヘ in katakana)

* Ge (Cyrillic), a Cyrillic letter cal ...

century," and he is still celebrated as a literary hero in Lebanon. At the same time, "most of Gibran's paintings expressed his personal vision, incorporating spiritual and mythological symbolism," with art critic Alice Raphael recognizing in the painter a classicist

Classics, also classical studies or Ancient Greek and Roman studies, is the study of classical antiquity. In the Western world, ''classics'' traditionally refers to the study of Ancient Greek literature, Ancient Greek and Roman literature and ...

, whose work owed "more to the findings of Da Vinci

Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci (15 April 1452 - 2 May 1519) was an Italian polymath of the High Renaissance who was active as a painter, draughtsman, engineer, scientist, theorist, sculptor, and architect. While his fame initially rested o ...

than it idto any modern insurgent." His "prodigious body of work" has been described as "an artistic legacy to people of all nations".

Life

Childhood

Gibran was born January 6, 1883, in the village ofBsharri

Bsharri ( ''Bšarrī''; also romanized ''Becharre'', ''Bcharre'', ''Bsharre'', ''Bcharre Al Arz'') is a Lebanese town located in the district of the same name, North Governorate, situated at altitudes between and . Bsharri is the location o ...

in the Mount Lebanon Mutasarrifate

The Mount Lebanon Mutasarrifate (1861–1918, ; ) was one of the Ottoman Empire's subdivisions following the 19th-century Tanzimat reform. After 1861, there existed an autonomous Mount Lebanon with a Christian Mutasarrif (governor), which had be ...

(modern-day Lebanon

Lebanon, officially the Republic of Lebanon, is a country in the Levant region of West Asia. Situated at the crossroads of the Mediterranean Basin and the Arabian Peninsula, it is bordered by Syria to the north and east, Israel to the south ...

).. The few records mentioning the Gibrans indicate that they arrived at Bsharri towards the end of the 17th-century. While a family myth links them to Chaldean sources, a more plausible story relates that the Gibran family came from Damascus

Damascus ( , ; ) is the capital and List of largest cities in the Levant region by population, largest city of Syria. It is the oldest capital in the world and, according to some, the fourth Holiest sites in Islam, holiest city in Islam. Kno ...

, Syria

Syria, officially the Syrian Arab Republic, is a country in West Asia located in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Levant. It borders the Mediterranean Sea to the west, Turkey to Syria–Turkey border, the north, Iraq to Iraq–Syria border, t ...

, in the 16th-century, and settled on a farm near Baalbek

Baalbek (; ; ) is a city located east of the Litani River in Lebanon's Beqaa Valley, about northeast of Beirut. It is the capital of Baalbek-Hermel Governorate. In 1998, the city had a population of 82,608. Most of the population consists of S ...

, later moving to Bash'elah in 1672. Another story places the origin of the Gibran family in Acre

The acre ( ) is a Unit of measurement, unit of land area used in the Imperial units, British imperial and the United States customary units#Area, United States customary systems. It is traditionally defined as the area of one Chain (unit), ch ...

before migrating to Bash'elah in the year 1300. Gibran parents, Khalil Sa'ad Gibran and Kamila Rahmeh, the daughter of a priest, were Maronite

Maronites (; ) are a Syriac Christianity, Syriac Christian ethnoreligious group native to the Eastern Mediterranean and the Levant (particularly Lebanon) whose members belong to the Maronite Church. The largest concentration has traditionally re ...

Christian. As written by Bushrui and Jenkins, they would set for Gibran an example of tolerance by "refusing to perpetuate religious prejudice and bigotry in their daily lives." Kamila's paternal grandfather had converted from Islam to Christianity. She was thirty when Gibran was born, and Gibran's father, Khalil, was her third husband. Gibran had two younger sisters, Marianna and Sultana, and an older half-brother, Boutros, from one of Kamila's previous marriages. Gibran's family lived in poverty. In 1888, Gibran entered Bsharri's one-class school, which was run by a priest, and there he learnt the rudiments of Arabic, Syriac, and arithmetic.

Gibran's father initially worked in an apothecary

''Apothecary'' () is an Early Modern English, archaic English term for a medicine, medical professional who formulates and dispenses ''materia medica'' (medicine) to physicians, surgeons and patients. The modern terms ''pharmacist'' and, in Brit ...

, but he had gambling debts he was unable to pay. He went to work for a local Ottoman-appointed administrator. In 1891, while acting as a tax collector, he was removed and his staff was investigated. Khalil was imprisoned for embezzlement, and his family's property was confiscated by the authorities. Kamila decided to follow her brother to the United States. Although Khalil was released in 1894, Kamila remained resolved and left for New York on June 25, 1895, taking Boutros, Gibran, Marianna and Sultana with her.

Kamila and her children settled in Boston's South End, at the time the second-largest Syrian-Lebanese-American community in the United States. Gibran entered the Josiah Quincy School on September 30, 1895. School officials placed him in a special class for immigrants to learn English. His name was registered using the anglicized spelling 'Ka''h''lil Gibran'. His mother began working as a seamstress peddler, selling lace and linens that she carried from door-to-door. His half-brother Boutros opened a shop. Gibran also enrolled in an art school at Denison House, a nearby

Kamila and her children settled in Boston's South End, at the time the second-largest Syrian-Lebanese-American community in the United States. Gibran entered the Josiah Quincy School on September 30, 1895. School officials placed him in a special class for immigrants to learn English. His name was registered using the anglicized spelling 'Ka''h''lil Gibran'. His mother began working as a seamstress peddler, selling lace and linens that she carried from door-to-door. His half-brother Boutros opened a shop. Gibran also enrolled in an art school at Denison House, a nearby settlement house

The settlement movement was a reformist social movement that began in the 1880s and peaked around the 1920s in the United Kingdom and the United States. Its goal was to bring the rich and the poor of society together in both physical proximity an ...

. Through his teachers there, he was introduced to the avant-garde

In the arts and literature, the term ''avant-garde'' ( meaning or ) identifies an experimental genre or work of art, and the artist who created it, which usually is aesthetically innovative, whilst initially being ideologically unacceptable ...

Boston artist, photographer and publisher F. Holland Day

Fred Holland Day (July 23, 1864 – November 23, 1933) was an American photographer and publisher. He was prominent in literary and photography circles in the late nineteenth century and was a leading Pictorialist. He was an early and vocal ...

, who encouraged and supported Gibran in his creative endeavors. In March 1898, Gibran met Josephine Preston Peabody

Josephine Preston Peabody (May 30, 1874 – December 4, 1922) was an American poet and dramatist.

Biography

Peabody was born in New York and educated at the Girls' Latin School, Boston, and at Radcliffe College. She also participated in Geor ...

, eight years his senior, at an exhibition of Day's photographs "in which Gibran's face was a major subject." Gibran would develop a romantic attachment to her. The same year, a publisher used some of Gibran's drawings for book covers.

Kamila and Boutros wanted Gibran to absorb more of his own heritage rather than just the Western aesthetic culture he was attracted to. Thus, at the age of 15, Gibran returned to his homeland to study Arabic literature

Arabic literature ( / ALA-LC: ''al-Adab al-‘Arabī'') is the writing, both as prose and poetry, produced by writers in the Arabic language. The Arabic word used for literature is ''Adab (Islam), Adab'', which comes from a meaning of etiquett ...

for three years at the Collège de la Sagesse

The Collège de la Sagesse () is a Lebanese major national and Catholic school founded in 1875 by the Maronite archbishop of Beirut at the time, Joseph Debs who laid the first stone of the original building. The school originally known as l'É ...

, a Maronite-run institute in Beirut

Beirut ( ; ) is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Lebanon. , Greater Beirut has a population of 2.5 million, just under half of Lebanon's population, which makes it the List of largest cities in the Levant region by populatio ...

, also learning French. In his final year at the school, Gibran created a student magazine with other students, including Youssef Howayek

Youssef Saadallah Howayek (; also Yusuf Huwayyik, Hoyek, Hoayek, Hawayek) (1883–1962) was a painter, sculptor and writer from Helta, in modern-day Lebanon.

Career

Youssef Howayek's father, Saadallah Howayek, was a Councillor elected into t ...

(who would remain a lifelong friend of his),. and he was made the "college poet". Gibran graduated from the school at eighteen with high honors, then went to Paris to learn painting, visiting Greece, Italy, and Spain on his way there from Beirut. On April 2, 1902, Sultana died at the age of 14, from what is believed to have been tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB), also known colloquially as the "white death", or historically as consumption, is a contagious disease usually caused by ''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can al ...

. Upon learning about it, Gibran returned to Boston, arriving two weeks after Sultana's death. The following year, on March 12, Boutros died of the same disease, with his mother passing from cancer on June 28.. Two days later, Peabody "left him without explanation." Marianna supported Gibran and herself by working at a dressmaker's shop.

Debuts, Mary Haskell, and second stay in Paris

Gibran held the first art exhibition of his drawings in January 1904 in Boston at Day's studio. During this exhibition, Gibran met Mary Haskell, the headmistress of a girls' school in the city, nine years his senior. The two formed a friendship that lasted the rest of Gibran's life. Haskell would spend large sums of money to support Gibran and would also edit all of his English writings. The nature of their romantic relationship remains obscure; while some biographers assert the two were lovers but never married because Haskell's family objected, other evidence suggests that their relationship was never physically consummated. Gibran and Haskell were engaged briefly between 1910 and 1911. According to Joseph P. Ghougassian, Gibran had proposed to her "not knowing how to repay back in gratitude to Miss Haskell," but Haskell called it off, making it "clear to him that she preferred his friendship to any burdensome tie of marriage.". Haskell would later marry Jacob Florance Minis in 1926, while remaining Gibran's close friend, patroness and benefactress, and using her influence to advance his career.

It was in 1904 also that Gibran met Amin al-Ghurayyib, editor of ''Al-Mohajer'' ('The Emigrant'), where Gibran started to publish articles. In 1905, Gibran's first published written work was ''A Profile of the Art of Music'', in Arabic, by ''Al-Mohajer''s printing department in New York City. His next work, ''Nymphs of the Valley'', was published the following year, also in Arabic. On January 27, 1908, Haskell introduced Gibran to her friend writer

Gibran held the first art exhibition of his drawings in January 1904 in Boston at Day's studio. During this exhibition, Gibran met Mary Haskell, the headmistress of a girls' school in the city, nine years his senior. The two formed a friendship that lasted the rest of Gibran's life. Haskell would spend large sums of money to support Gibran and would also edit all of his English writings. The nature of their romantic relationship remains obscure; while some biographers assert the two were lovers but never married because Haskell's family objected, other evidence suggests that their relationship was never physically consummated. Gibran and Haskell were engaged briefly between 1910 and 1911. According to Joseph P. Ghougassian, Gibran had proposed to her "not knowing how to repay back in gratitude to Miss Haskell," but Haskell called it off, making it "clear to him that she preferred his friendship to any burdensome tie of marriage.". Haskell would later marry Jacob Florance Minis in 1926, while remaining Gibran's close friend, patroness and benefactress, and using her influence to advance his career.

It was in 1904 also that Gibran met Amin al-Ghurayyib, editor of ''Al-Mohajer'' ('The Emigrant'), where Gibran started to publish articles. In 1905, Gibran's first published written work was ''A Profile of the Art of Music'', in Arabic, by ''Al-Mohajer''s printing department in New York City. His next work, ''Nymphs of the Valley'', was published the following year, also in Arabic. On January 27, 1908, Haskell introduced Gibran to her friend writer Charlotte Teller

Charlotte Rose Teller, later Hirsch (March 3, 1876 – December 30, 1953), also using the pen name John Brangwyn, was an American writer and socialist active in New York City. She graduated in 1899 from the University of Chicago (BA). Her book The ...

, aged 31, and in February, to Émilie Michel (Micheline), a French teacher at Haskell's school,. aged 19. Both Teller and Micheline agreed to pose for Gibran as models and became close friends of his. The same year, Gibran published ''Spirits Rebellious'' in Arabic, a novel deeply critical of secular and spiritual authority. According to Barbara Young, a late acquaintance of Gibran, "in an incredibly short time it was burned in the market place in Beirut by priestly zealots who pronounced it 'dangerous, revolutionary, and poisonous to youth. The Maronite Patriarchate would let the rumor of his excommunication wander, but would never officially pronounce it.

In July 1908, with Haskell's financial support, Gibran went to study art in Paris at the Académie Julian

The () was a private art school for painting and sculpture founded in Paris, France, in 1867 by French painter and teacher Rodolphe Julian (1839–1907). The school was active from 1868 through 1968. It remained famous for the number and qual ...

where he joined the ''atelier'' of Jean-Paul Laurens

Jean-Paul Laurens (; 28 March 1838 – 23 March 1921) was a romanticism French painter and sculptor, and he is one of the last major exponents of the French Academic style.

Biography

Laurens was born in Fourquevaux and was a pupil of Léon ...

. Gibran had accepted Haskell's offer partly so as to distance himself from Micheline, "for he knew that this love was contrary to his sense of gratefulness toward Miss Haskell"; however, "to his surprise Micheline came unexpectedly to him in Paris.". "She became pregnant, but the pregnancy was ectopic, and she had to have an abortion, probably in France." Micheline had returned to the United States by late October. Gibran would pay her a visit upon her return to Paris in July 1910, but there would be no hint of intimacy left between them.

By early February 1909, Gibran had "been working for a few weeks in the studio of Pierre Marcel-Béronneau

Pierre Amédée Marcel-Béronneau (1869–1937) was a French Symbolist painter. He first worked at the École des Beaux-Arts de Bordeaux at the same time as Fernand Sabatté then became "one of the most brilliant students" of Gustave Moreau ...

", and he "used his sympathy towards Béronneau as an excuse to leave the Académie Julian altogether." In December 1909, Gibran started a series of pencil portraits that he would later call "The Temple of Art", featuring "famous men and women artists of the day" and "a few of Gibran's heroes from past times." While in Paris, Gibran also entered into contact with Syrian political dissidents, in whose activities he would attempt to be more involved upon his return to the United States. In June 1910, Gibran visited London with Howayek and Ameen Rihani

Ameen Rihani (Amīn Fāris Anṭūn ar-Rīḥānī; / ALA-LC: ''Amīn ar-Rīḥānī''; November 24, 1876 – September 13, 1940) was a Lebanese-American writer, intellectual and political activist. He was also a major figure in the ''mah ...

, whom Gibran had met in Paris. Rihani, who was six years older than Gibran, would be Gibran's role model for a while, and a friend until at least May 1912.. Gibran biographer Robin Waterfield

Robin Anthony Herschel Waterfield (born 6 August 1952) is a British classical scholar, translator, editor, and writer of children's fiction.

Career

Waterfield was born in 1952, and studied Classics at Manchester University, where he achieved a f ...

argues that, by 1918, "as Gibran's role changed from that of angry young man to that of prophet, Rihani could no longer act as a paradigm". Haskell (in her private journal entry of May 29, 1924) and Howayek also provided hints at an enmity that began between Gibran and Rihani sometime after May 1912.

Return to the United States and growing reputation

Gibran sailed back to New York City fromBoulogne-sur-Mer

Boulogne-sur-Mer (; ; ; or ''Bononia''), often called just Boulogne (, ), is a coastal city in Hauts-de-France, Northern France. It is a Subprefectures in France, sub-prefecture of the Departments of France, department of Pas-de-Calais. Boul ...

on the ''Nieuw Amsterdam'' on October 22, 1910, and was back in Boston by November 11. By February 1911, Gibran had joined the Boston branch of a Syrian international organization, the Golden Links Society. He lectured there for several months "in order to promote radicalism in independence and liberty" from Ottoman Syria. At the end of April, Gibran was staying in Teller's vacant flat at 164 Waverly Place

Waverly Place is a narrow street in the Greenwich Village section of the New York City borough of Manhattan, that runs from Bank Street to Broadway. Waverly changes direction roughly at its midpoint at Christopher Street, turning about 120 ...

in New York City. "Gibran settled in, made himself known to his Syrian friends—especially Amin Rihani, who was now living in New York—and began both to look for a suitable studio and to sample the energy of New York." As Teller returned on May 15, he moved to Rihani's small room at 28 West 9th Street. Gibran then moved to one of the Tenth Street Studio Building

The Tenth Street Studio Building, constructed in New York City in 1857, was the first modern facility designed solely to serve the needs of artists. It became the center of the New York art world for the remainder of the 19th century.

Situated a ...

's studios for the summer, before changing to another of its studios (number 30, which had a balcony, on the third story) in fall. Gibran would live there until his death, referring to it as "The Hermitage.". Over time, however, and "ostensibly often for reasons of health", he would spend "longer and longer periods away from New York, sometimes months at a time .. staying either with friends in the countryside or with Marianna in Boston or on the Massachusetts

Massachusetts ( ; ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Maine to its east, Connecticut and Rhode ...

coast.". His friendships with Teller and Micheline would wane; the last encounter between Gibran and Teller would occur in September 1912, and Gibran would tell Haskell in 1914 that he now found Micheline "repellent."

In 1912, the poetic

In 1912, the poetic novella

A novella is a narrative prose fiction whose length is shorter than most novels, but longer than most novelettes and short stories. The English word ''novella'' derives from the Italian meaning a short story related to true (or apparently so) ...

'' Broken Wings'' was published in Arabic by the printing house of the periodical '' Meraat-ul-Gharb'' in New York. Gibran presented a copy of his book to Lebanese writer May Ziadeh

May Elias Ziadeh ( ; , ; 11 February 1886 – 17 October 1941) was a Palestinians, Palestinian-Lebanese people, Lebanese Maronite poet, essayist, and translator, who wrote many different works both in Arabic language, Arabic and in French la ...

, who lived in Egypt, and asked her to criticize it. As worded by Ghougassian,

Gibran and Ziadeh never met. According to Shlomit C. Schuster

Shlomit C. Schuster (; born 19 July 1951 in Paramaribo, Suriname; died 15 February 2016 in Jerusalem, Israel) was an Israeli philosophical counselor, considered a pioneer in the field.

Schuster migrated to Israel in 1976 and studied philosop ...

, "whatever the relationship between Kahlil and May might have been, the letters in ''A Self-Portrait'' mainly reveal their literary ties. Ziadeh reviewed all of Gibran's books and Gibran replies to these reviews elegantly."

In 1913, Gibran started contributing to ''Al-Funoon

''Al-Funoon'' () was an Arabic-language magazine founded in New York City by Nasib Arida in 1913 and co-edited by Mikhail Naimy, "so that he might display his knowledge of international literature." As worded by Suheil Bushrui, it was "the fir ...

'', an Arabic-language magazine that had been recently established by Nasib Arida

Nasib Arida (, ; 1887–1946) was a Syrian-born poet and writer of the Mahjar movement and a founding member of the New York Pen League.

Life

Arida was born in Homs to a Syrian Greek Orthodox family where he received his education until h ...

and Abd al-Masih Haddad. ''A Tear and a Smile'' was published in Arabic in 1914. In December of the same year, visual artworks by Gibran were shown at the Montross Gallery, catching the attention of American painter Albert Pinkham Ryder

Albert Pinkham Ryder (March 19, 1847 – March 28, 1917) was an American painter best known for his poetic and moody allegory, allegorical works and seascapes, as well as his Eccentricity (behavior), eccentric personality. While his art shared an ...

. Gibran wrote him a prose poem in January and would become one of the aged man's last visitors. After Ryder's death in 1917, Gibran's poem would be quoted first by Henry McBride in the latter's posthumous tribute to Ryder, then by newspapers across the country, from which would come the first widespread mention of Gibran's name in America.. By March 1915, two of Gibran's poems had also been read at the Poetry Society of America

Poetry (from the Greek word '' poiesis'', "making") is a form of literary art that uses aesthetic and often rhythmic qualities of language to evoke meanings in addition to, or in place of, literal or surface-level meanings. Any partic ...

, after which Corinne Roosevelt Robinson

Corinne Roosevelt Robinson (September 27, 1861 – February 17, 1933) was an American poet, writer and lecturer. She was also the younger sister of President of the United States Theodore Roosevelt and an aunt of First Lady of the United States, ...

, the younger sister of Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. (October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), also known as Teddy or T.R., was the 26th president of the United States, serving from 1901 to 1909. Roosevelt previously was involved in New York (state), New York politics, incl ...

, stood up and called them "destructive and diabolical stuff"; nevertheless, beginning in 1918 Gibran would become a frequent visitor at Robinson's, also meeting her brother.

''The Madman'', the Pen League, and ''The Prophet''

Gibran acted as a secretary of theSyrian–Mount Lebanon Relief Committee

The Syrian–Mount Lebanon Relief Committee () was an organization "formed in June of 1916 under the chairmanship of Najib Maalouf and the Assistant Chairmanship of Ameen Rihani" in the United States. Kahlil Gibran was its secretary. Its offices we ...

, which was formed in June 1916. The same year, Gibran met Lebanese author Mikhail Naimy

Mikha'il Nu'ayma (, ; US legal name: Michael Joseph Naimy), better known in English by his pen name Mikhail Naimy (October 17, 1889 – February 28, 1988), was a Lebanese poet, novelist, and philosopher, famous for his spiritual writings, notabl ...

after Naimy had moved from the University of Washington

The University of Washington (UW and informally U-Dub or U Dub) is a public research university in Seattle, Washington, United States. Founded in 1861, the University of Washington is one of the oldest universities on the West Coast of the Uni ...

to New York. Naimy, whom Gibran would nickname "Mischa", had previously made a review of ''Broken Wings'' in his article "The Dawn of Hope After the Night of Despair", published in ''Al-Funoon'', and he would become "a close friend and confidant, and later one of Gibran's biographers." In 1917, an exhibition of forty wash drawings was held at Knoedler

M. Knoedler & Co. () was an art dealership in New York City founded in 1846. When it closed in 2011, amid lawsuits for fraud, it was one of the oldest commercial art galleries in the US, having been in operation for 165 years.

History

Knoedler ...

in New York from January 29 to February 19 and another of thirty such drawings at Doll & Richards, Boston, April 16–28.

While most of Gibran's early writings had been in Arabic, most of his work published after 1918 was in English. Such was '' The Madman'', Gibran's first book published by

While most of Gibran's early writings had been in Arabic, most of his work published after 1918 was in English. Such was '' The Madman'', Gibran's first book published by Alfred A. Knopf

Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. () is an American publishing house that was founded by Blanche Knopf and Alfred A. Knopf Sr. in 1915. Blanche and Alfred traveled abroad regularly and were known for publishing European, Asian, and Latin American writers ...

in 1918. ''The Processions'' (in Arabic) and ''Twenty Drawings'' were published the following year. In 1920, Gibran re-created the Arabic-language New York Pen League

The Mahjar (, one of its more literal meanings being "the Arab diaspora") was a movement related to Romanticism migrant literary movement started by Arabic-speaking writers who had emigrated to the Americas from Ottoman-ruled Lebanon, Syria and P ...

with Arida and Haddad (its original founders), Rihani, Naimy, and other Mahjar

The Mahjar (, one of its more literal meanings being "the Arab diaspora") was a movement related to Romanticism migrant literary movement started by Arabic-speaking writers who had emigrated to the Americas from Ottoman-ruled Lebanon, Syria and ...

i writers such as Elia Abu Madi

Elia Abu Madi (also known as Elia D. Madey; 'Lebanese Arabic Transliteration: , .) (May 15, 1890 – November 23, 1957) was a Lebanon, Lebanese-born American poet.

Early life

Abu Madi was born in the village of Al-Muhaydithah, now part o ...

. The same year, ''The Tempests'' was published in Arabic in Cairo, and ''The Forerunner'' in New York.

In a letter of 1921 to Naimy, Gibran reported that doctors had told him to "give up all kinds of work and exertion for six months, and do nothing but eat, drink and rest"; in 1922, Gibran was ordered to "stay away from cities and city life" and had rented a cottage near the sea, planning to move there with Marianna and to remain until "this heart egainedits orderly course"; this three-month summer in Scituate, he later told Haskell, was a refreshing time, during which he wrote some of "the best Arabic poems" he had ever written..

In 1923, ''The New and the Marvelous'' was published in Arabic in Cairo, whereas '' The Prophet'' was published in New York. ''The Prophet'' sold well despite a cool critical reception. At a reading of ''The Prophet'' organized by rector William Norman Guthrie

William Norman Guthrie also known as Norman de Lagutry (4 March 1868 – 9 December 1944) was an American clergyman and grandson of famous radical Frances Wright. His father, Eugène Picault de Lagutry, was the husband of Frances Sylva Piquepal d ...

in St. Mark's Church in-the-Bowery

St. Mark's Church in-the-Bowery is a parish of the Episcopal Church at 131 East 10th Street (near Stuyvesant Street and Second Avenue) in the East Village neighborhood of Manhattan in New York City. The property has been the site of continuo ...

, Gibran met poet Barbara Young, who would occasionally work as his secretary from 1925 until Gibran's death; Young did this work without remuneration. In 1924, Gibran told Haskell that he had been contracted to write ten pieces for '' Al-Hilal'' in Cairo. In 1925, Gibran participated in the founding of the periodical ''The New East''.

Later years and death

''Sand and Foam'' was published in 1926, and ''Jesus, the Son of Man'' in 1928. At the beginning of 1929, Gibran was diagnosed with an

''Sand and Foam'' was published in 1926, and ''Jesus, the Son of Man'' in 1928. At the beginning of 1929, Gibran was diagnosed with an enlarged liver

Hepatomegaly is enlargement of the liver. It is a non-specific medical sign, having many causes, which can broadly be broken down into infection, hepatic tumours, and metabolic disorder. Often, hepatomegaly presents as an abdominal mass. Dependi ...

. In a letter dated March 26, he wrote to Naimy that "the rheumatic pains are gone, and the swelling has turned to something opposite". In a telegram dated the same day, he reported being told by the doctors that he "must not work for full year", which was something he found "more painful than illness." The last book published during Gibran's life was ''The Earth Gods

''The Earth Gods'' is a literary work written by poet and philosopher Kahlil Gibran. It was originally published in 1931, also the year of the author's death. The story is structured as a dialogue between three unnamed earth gods, only referred t ...

'', on March 14, 1931.

Gibran was admitted to St. Vincent's Hospital, Manhattan

Saint Vincent's Catholic Medical Centers (also known as Saint Vincent's or SVCMC) was a healthcare system in New York City, anchored by its flagship hospital, St. Vincent's Hospital Manhattan.

St. Vincent's was founded in 1849 and was a majo ...

, on April 10, 1931, where he died the same day, aged forty-eight, after refusing the last rites

The last rites, also known as the Commendation of the Dying, are the last prayers and ministrations given to an individual of Christian faith, when possible, shortly before death. The Commendation of the Dying is practiced in liturgical Chri ...

. The cause of death was reported to be cirrhosis

Cirrhosis, also known as liver cirrhosis or hepatic cirrhosis, chronic liver failure or chronic hepatic failure and end-stage liver disease, is a chronic condition of the liver in which the normal functioning tissue, or parenchyma, is replaced ...

of the liver with incipient tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB), also known colloquially as the "white death", or historically as consumption, is a contagious disease usually caused by ''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can al ...

in one of his lungs. Waterfield argues that the cirrhosis was contracted through excessive drinking of alcohol and was the only real cause of Gibran's death.

Providence, Rhode Island

Providence () is the List of capitals in the United States, capital and List of municipalities in Rhode Island, most populous city of the U.S. state of Rhode Island. The county seat of Providence County, Rhode Island, Providence County, it is o ...

, and from there to Lebanon on the liner ''Sinaia

Sinaia () is a town and a mountain resort in Prahova County, Romania. It is situated in the historical region of Muntenia. The town was named after the Sinaia Monastery of 1695, around which it was built. The monastery, in turn, is named after ...

''. Gibran's body reached Bsharri in August and was deposited in a church near-by until a cousin of Gibran finalized the purchase of the Mar Sarkis Monastery, now the Gibran Museum

The Gibran Museum, formerly the Monastery of Mar Sarkis, is a biographical museum in Bsharri, Lebanon, from Beirut. It is dedicated to the Lebanese writer, philosopher, and artist Kahlil Gibran.

The museum was an old cavern where many hermit ...

.

All future American royalties to his books were willed to his hometown of Bsharri

Bsharri ( ''Bšarrī''; also romanized ''Becharre'', ''Bcharre'', ''Bsharre'', ''Bcharre Al Arz'') is a Lebanese town located in the district of the same name, North Governorate, situated at altitudes between and . Bsharri is the location o ...

, to be used for "civic betterment.". Gibran had also willed the contents of his studio to Haskell.

In 1950, Haskell donated her personal collection of nearly one hundred original works of art by Gibran (including five oils) to the Telfair Museum of Art

Telfair Museums, in the historic district of Savannah, Georgia, was the first public art museum in the Southern United States. Founded through the bequest of Mary Telfair (1791–1875), a prominent local citizen, and operated by the Georgia Hi ...

in Savannah, Georgia

Savannah ( ) is the oldest city in the U.S. state of Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia and the county seat of Chatham County, Georgia, Chatham County. Established in 1733 on the Savannah River, the city of Savannah became the Kingdom of Great Brita ...

. Haskell had been thinking of placing her collection at the Telfair as early as 1914. Her gift to the Telfair is the largest public collection of Gibran's visual art in the country.

Works

Writings

Forms, themes, and language

Gibran explored literary forms as diverse as "poetry,parable

A parable is a succinct, didactic story, in prose or verse, that illustrates one or more instructive lessons or principles. It differs from a fable in that fables employ animals, plants, inanimate objects, or forces of nature as characters, whe ...

s, fragments of conversation, short stories

A short story is a piece of prose fiction. It can typically be read in a single sitting and focuses on a self-contained incident or series of linked incidents, with the intent of evoking a single effect or mood. The short story is one of the old ...

, fable

Fable is a literary genre defined as a succinct fictional story, in prose or verse, that features animals, legendary creatures, plants, inanimate objects, or forces of nature that are anthropomorphized, and that illustrates or leads to a parti ...

s, political essay

An essay ( ) is, generally, a piece of writing that gives the author's own argument, but the definition is vague, overlapping with those of a Letter (message), letter, a term paper, paper, an article (publishing), article, a pamphlet, and a s ...

s, letters, and aphorism

An aphorism (from Greek ἀφορισμός: ''aphorismos'', denoting 'delimitation', 'distinction', and 'definition') is a concise, terse, laconic, or memorable expression of a general truth or principle. Aphorisms are often handed down by tra ...

s." Two plays

Play most commonly refers to:

* Play (activity), an activity done for enjoyment

* Play (theatre), a work of drama

Play may refer also to:

Computers and technology

* Google Play, a digital content service

* Play Framework, a Java framework

* P ...

in English and five plays in Arabic were also published posthumously between 1973 and 1993; three unfinished plays written in English towards the end of Gibran's life remain unpublished (''The Banshee'', ''The Last Unction'', and ''The Hunchback or the Man Unseen''). Gibran discussed "such themes as religion, justice, free will, science, love, happiness, the soul, the body, and death" in his writings, which were "characterized by innovation breaking with forms of the past, by symbolism

Symbolism or symbolist may refer to:

*Symbol, any object or sign that represents an idea

Arts

*Artistic symbol, an element of a literary, visual, or other work of art that represents an idea

** Color symbolism, the use of colors within various c ...

, an undying love for his native land, and a sentimental, melancholic yet often oratorical style." According to Salma Jayyusi

Salma Khadra Jayyusi (; 16 April 1925 – 20 April 2023) was a Palestinian poet, writer, translator and anthologist. She was the founder and director of the Project of Translation from Arabic (PROTA), which aims to provide translation of Arabic ...

, Roger Allen and others, Gibran as the leading poet of the Mahjar

The Mahjar (, one of its more literal meanings being "the Arab diaspora") was a movement related to Romanticism migrant literary movement started by Arabic-speaking writers who had emigrated to the Americas from Ottoman-ruled Lebanon, Syria and ...

school belongs to Romantic (neo-romantic

The term neo-romanticism is used to cover a variety of movements in philosophy, literature, music, painting, and architecture, as well as social movements, that exist after and incorporate elements from the era of Romanticism.

It has been used ...

) movement.

About his language in general (both in Arabic and English), Salma Khadra Jayyusi

Salma Khadra Jayyusi (; 16 April 1925 – 20 April 2023) was a Palestinian poet, writer, translator and anthologist. She was the founder and director of the Project of Translation from Arabic (PROTA), which aims to provide translation of Arabic ...

remarks that "because of the spiritual and universal aspect of his general themes, he seems to have chosen a vocabulary less idiomatic than would normally have been chosen by a modern poet conscious of modernism in language." According to Jean Gibran and Kahlil G. Gibran,

The poem "You Have Your Language and I Have Mine" (1924) was published in response to criticism of his Arabic language and style.

Influences and antecedents

According to Bushrui and Jenkins, an "inexhaustible" source of influence on Gibran was theBible

The Bible is a collection of religious texts that are central to Christianity and Judaism, and esteemed in other Abrahamic religions such as Islam. The Bible is an anthology (a compilation of texts of a variety of forms) originally writt ...

, especially the King James Version

The King James Version (KJV), also the King James Bible (KJB) and the Authorized Version (AV), is an Early Modern English Bible translations, Early Modern English translation of the Christianity, Christian Bible for the Church of England, wh ...

. Gibran's literary oeuvre is also steeped in the Syriac tradition. According to Haskell, Gibran once told her that As worded by Waterfield, "the parables of the New Testament" affected "his parables and homilies" while "the poetry of some of the Old Testament books" affected "his devotional language and incantational rhythms." Annie Salem Otto notes that Gibran avowedly imitated the style of the Bible, whereas other Arabic authors from his time like Rihani unconsciously imitated the Quran

The Quran, also Romanization, romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a Waḥy, revelation directly from God in Islam, God (''Allah, Allāh''). It is organized in 114 chapters (, ) which ...

.

According to Ghougassian, the works of English poet

According to Ghougassian, the works of English poet William Blake

William Blake (28 November 1757 – 12 August 1827) was an English poet, painter, and printmaker. Largely unrecognised during his life, Blake has become a seminal figure in the history of the Romantic poetry, poetry and visual art of the Roma ...

"played a special role in Gibran's life", and in particular "Gibran agreed with Blake's ''apocalyptic vision'' of the world as the latter expressed it in his poetry and art.". Gibran wrote of Blake as "the God-man", and of his drawings as "so far the profoundest things done in English—and his vision, putting aside his drawings and poems, is the most godly." According to George Nicolas El-Hage,

Gibran was also a great admirer of Syrian poet and writer Francis Marrash, whose works Gibran had studied at the Collège de la Sagesse.. According to Shmuel Moreh

Shmuel Moreh (; December 22, 1932 – September 22, 2017) was a professor of Arabic Language and Literature at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and a recipient of the Israel Prize in Middle Eastern studies in 1999. In addition to having written ...

, Gibran's own works echo Marrash's style, including the structure of some of his works and "many of isideas on enslavement, education, women's liberation, truth, the natural goodness of man, and the corrupted morals of society." Bushrui and Jenkins have mentioned Marrash's concept of universal love, in particular, in having left a "profound impression" on Gibran.

Another influence on Gibran was American poet Walt Whitman

Walter Whitman Jr. (; May 31, 1819 – March 26, 1892) was an American poet, essayist, and journalist; he also wrote two novels. He is considered one of the most influential poets in American literature and world literature. Whitman incor ...

, whom Gibran followed "by pointing up the universality of all men and by delighting in nature. According to El-Hage, the influence of German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (15 October 1844 – 25 August 1900) was a German philosopher. He began his career as a classical philology, classical philologist, turning to philosophy early in his academic career. In 1869, aged 24, Nietzsche bec ...

"did not appear in Gibran's writings until ''The Tempests''.". Nevertheless, although Nietzsche's style "no doubt fascinated" him, Gibran was "not the least under his spell":

Critics

Gibran was neglected by scholars and critics for a long time.. Bushrui and John M. Munro have argued that "the failure of serious Western critics to respond to Gibran" resulted from the fact that "his works, though for the most part originally written in English, cannot be comfortably accommodated within the Western literary tradition." According to El-Hage, critics have also "generally failed to understand the poet's conception of imagination and his fluctuating tendencies towards nature."Visual art

Overview

According to Waterfield, "Gibran was confirmed in his aspiration to be a Symbolist painter" after working in Marcel-Béronneau's studio in Paris.Oil paint

Oil paint is a type of slow-drying paint that consists of particles of pigment suspended in a drying oil, commonly linseed oil. Oil paint also has practical advantages over other paints, mainly because it is waterproof.

The earliest surviving ...

was Gibran's "preferred medium between 1908 and 1914, but before and after this time he worked primarily with pencil, ink, watercolor

Watercolor (American English) or watercolour (Commonwealth English; see American and British English spelling differences#-our, -or, spelling differences), also ''aquarelle'' (; from Italian diminutive of Latin 'water'), is a painting metho ...

and gouache

Gouache (; ), body color, or opaque watercolor is a water-medium paint consisting of natural pigment, water, a binding agent (usually gum arabic or dextrin), and sometimes additional inert material. Gouache is designed to be opaque. Gouach ...

." In a letter to Haskell, Gibran wrote that "among all the English artists Turner

Turner may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Turner (surname), a common surname, including a list of people and fictional characters with the name

* Turner (given name), a list of people with the given name

*One who uses a lathe for tur ...

is the very greatest." In her diary entry of March 17, 1911, Haskell recorded that Gibran told her he was inspired by J. M. W. Turner's painting ''The Slave Ship

''The Slave Ship'', originally titled ''Slavers Throwing overboard the Dead and Dying—Typhon coming on'', is a painting by the British artist J. M. W. Turner, first exhibited at The Royal Academy of Arts in 1840.

Measuring in oil on can ...

'' (1840) to utilize "raw colors ..one over another on the canvas ..instead of killing them first on the palette" in what would become the painting ''Rose Sleeves'' (1911, Telfair Museums

Telfair Museums, in the historic district of Savannah, Georgia, was the first public art museum in the Southern United States. Founded through the bequest of Mary Telfair (1791–1875), a prominent local citizen, and operated by the Georgia His ...

).

Gibran created more than seven hundred visual artworks, including the Temple of Art portrait series. His works may be seen at the Gibran Museum

The Gibran Museum, formerly the Monastery of Mar Sarkis, is a biographical museum in Bsharri, Lebanon, from Beirut. It is dedicated to the Lebanese writer, philosopher, and artist Kahlil Gibran.

The museum was an old cavern where many hermit ...

in Bsharri; the Telfair Museums

Telfair Museums, in the historic district of Savannah, Georgia, was the first public art museum in the Southern United States. Founded through the bequest of Mary Telfair (1791–1875), a prominent local citizen, and operated by the Georgia His ...

in Savannah, Georgia; the Museo Soumaya

The Museo Soumaya is a private museum in Mexico City and a non-profit cultural institution with two museum buildings in Mexico City — Plaza Carso and Plaza Loreto. It has over 66,000 works from 30 centuries of art including sculptures from Pre ...

in Mexico City; Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art in Doha; the Brooklyn Museum

The Brooklyn Museum is an art museum in the New York City borough (New York City), borough of Brooklyn. At , the museum is New York City's second largest and contains an art collection with around 500,000 objects. Located near the Prospect Heig ...

and the Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, colloquially referred to as the Met, is an Encyclopedic museum, encyclopedic art museum in New York City. By floor area, it is the List of largest museums, third-largest museum in the world and the List of larg ...

in New York City; and the Harvard Art Museums

The Harvard Art Museums are part of Harvard University and comprise three museums: the Fogg Museum (established in 1895), the Busch-Reisinger Museum (established in 1903), and the Arthur M. Sackler Museum (established in 1985), and four research ...

. A possible Gibran painting was the subject of a September 2008 episode of the PBS TV series ''History Detectives

''History Detectives'' was a documentary television series on PBS. It featured investigations made by members of a small team of researchers to identify and/or authenticate items which may have historical significance or connections to important h ...

''.

Gallery

Museo Soumaya

The Museo Soumaya is a private museum in Mexico City and a non-profit cultural institution with two museum buildings in Mexico City — Plaza Carso and Plaza Loreto. It has over 66,000 works from 30 centuries of art including sculptures from Pre ...

)

Khalil Gibran - Autorretrato con musa, c. 1911.jpg, ''Self-Portrait and Muse'', (Museo Soumaya

The Museo Soumaya is a private museum in Mexico City and a non-profit cultural institution with two museum buildings in Mexico City — Plaza Carso and Plaza Loreto. It has over 66,000 works from 30 centuries of art including sculptures from Pre ...

)

Untitled (Rose Sleeves) by Kahlil Gibran.jpg, ''Untitled (Rose Sleeves)'', 1911 (Telfair Museums

Telfair Museums, in the historic district of Savannah, Georgia, was the first public art museum in the Southern United States. Founded through the bequest of Mary Telfair (1791–1875), a prominent local citizen, and operated by the Georgia His ...

)

Towards the Infinite (Kamila Gibran, mother of the artist) MET 87681.jpg, ''Towards the Infinite (Kamila Gibran, mother of the artist)'', 1916 (Metropolitan Museum of Arts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, colloquially referred to as the Met, is an encyclopedic art museum in New York City. By floor area, it is the third-largest museum in the world and the largest art museum in the Americas. With 5.36 million v ...

)

The Three are One by Kahlil Gibran.jpg, ''The Three are One'', 1918 (Telfair Museums

Telfair Museums, in the historic district of Savannah, Georgia, was the first public art museum in the Southern United States. Founded through the bequest of Mary Telfair (1791–1875), a prominent local citizen, and operated by the Georgia His ...

), also '' The Madman''s frontispiece

The Slave by Kahlil Gibran.jpg, ''The Slave'', 1920 (Harvard Art Museums

The Harvard Art Museums are part of Harvard University and comprise three museums: the Fogg Museum (established in 1895), the Busch-Reisinger Museum (established in 1903), and the Arthur M. Sackler Museum (established in 1985), and four research ...

)

Standing Figure and Child by Kahlil Gibran.jpg, ''Standing Figure and Child'', undated ( Barjeel Art Foundation)

Religious views

According to Bushrui and Jenkins, Besides Christianity, Islam and Sufism, Gibran's mysticism was also influenced bytheosophy

Theosophy is a religious movement established in the United States in the late 19th century. Founded primarily by the Russian Helena Blavatsky and based largely on her writings, it draws heavily from both older European philosophies such as Neop ...

and Jung

Carl Gustav Jung ( ; ; 26 July 1875 – 6 June 1961) was a Swiss psychiatrist, psychotherapist, and psychologist who founded the school of analytical psychology. A prolific author of over 20 books, illustrator, and correspondent, Jung was a c ...

ian psychology.

Around 1911–1912, Gibran met with ʻAbdu'l-Bahá

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá (; Persian: , ;, 23 May 1844 – 28 November 1921), born ʻAbbás (, ), was the eldest son of Baháʼu'lláh, founder of the Bahá’í Faith, who designated him to be his successor and head of the Baháʼí Faith from 1892 un ...

, the leader of the Baháʼí Faith

The Baháʼí Faith is a religion founded in the 19th century that teaches the Baháʼí Faith and the unity of religion, essential worth of all religions and Baháʼí Faith and the unity of humanity, the unity of all people. Established by ...

who was visiting the United States, to draw his portrait. The meeting made a strong impression on Gibran. One of Gibran's acquaintances later in life, Juliet Thompson, herself a Baháʼí, reported that Gibran was unable to sleep the night before meeting him. This encounter with ʻAbdu'l-Bahá later inspired Gibran to write ''Jesus the Son of Man'' that portrays Jesus through the "words of seventy-seven contemporaries who knew him – enemies and friends: Syrians, Romans, Jews, priests, and poets." After the death of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, Gibran gave a talk on religion with Baháʼís and at another event with a viewing of a movie of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, Gibran rose to proclaim in tears an exalted station of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá and left the event weeping..

In the poem "The Voice of the Poet" (), published in ''A Tear and a Smile'' (1914), Gibran wrote:

In 1921, Gibran participated in an "interrogatory" meeting on the question "Do We Need a New World Religion to Unite the Old Religions?" at St. Mark's Church in-the-Bowery

St. Mark's Church in-the-Bowery is a parish of the Episcopal Church at 131 East 10th Street (near Stuyvesant Street and Second Avenue) in the East Village neighborhood of Manhattan in New York City. The property has been the site of continuo ...

.

Political thought

According to Young, Nevertheless, Gibran called for the adoption of Arabic as a national language of Syria, considered from a geographic point of view, not as a political entity. When Gibran metʻAbdu'l-Bahá

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá (; Persian: , ;, 23 May 1844 – 28 November 1921), born ʻAbbás (, ), was the eldest son of Baháʼu'lláh, founder of the Bahá’í Faith, who designated him to be his successor and head of the Baháʼí Faith from 1892 un ...

in 1911–12, who traveled to the United States partly to promote peace, Gibran admired the teachings on peace but argued that "young nations like his own" be freed from Ottoman control. Gibran also wrote his famous poem "Pity the Nation" during these years; it was published posthumously some 20 years later in ''The Garden of the Prophet

''The Prophet'' is a book of 26 prose poetry fables written in English by the Lebanese-American poet and writer Kahlil Gibran. It was originally published in 1923 by Alfred A. Knopf. It is Gibran's best known work. The Kahlil Gibran Collective ...

''.

On May 26, 1916, Gibran wrote a letter to Mary Haskell that reads: "The famine in Mount Lebanon has been planned and instigated by the Turkish government. Already 80,000 have succumbed to starvation and thousands are dying every single day. The same process happened with the Christian Armenians and applied to the Christians in Mount Lebanon." Gibran dedicated a poem named "Dead Are My People" to the fallen of the famine.

When the Ottomans were eventually driven from Syria during World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, Gibran sketched a euphoric drawing "Free Syria", which was then printed on the special edition cover of the Arabic-language paper '' As-Sayeh'' (''The Traveler''; founded 1912 in New York by Haddad). Adel Beshara reports that, "in a draft of a play, still kept among his papers, Gibran expressed great hope for national independence and progress. This play, according to Khalil Hawi

Khalil Hawi (Arabic: خليل حاوي; Transliterated Khalīl Ḥāwī) (1919-1982) was one of the most famous Lebanese poets of the 20th century. In 1982, upon the Israeli invasion of Beirut in the midst of the Lebanese Civil War, Hawi committed ...

, 'defines Gibran's belief in Syrian nationalism

Syrian nationalism (), also known as pan-Syrian nationalism or pan-Syrianism (), refers to the nationalism of the region of Syria, as a cultural or political entity known as " Greater Syria," known in Arabic as '' Bilād ash-Shām'' ().

Syrian ...

with great clarity, distinguishing it from both Lebanese and Arab nationalism

Arab nationalism () is a political ideology asserting that Arabs constitute a single nation. As a traditional nationalist ideology, it promotes Arab culture and civilization, celebrates Arab history, the Arabic language and Arabic literatur ...

, and showing us that nationalism lived in his mind, even at this late stage, side by side with internationalism.

According to Waterfield, Gibran "was not entirely in favour of socialism

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

(which he believed tends to seek the lowest common denominator, rather than bringing out the best in people)".

Legacy

The popularity of '' The Prophet'' grew markedly during the 1960s with theAmerican counterculture

A counterculture is a culture whose values and norms of behavior differ substantially from those of mainstream society, sometimes diametrically opposed to mainstream cultural mores.Eric Donald Hirsch. ''The Dictionary of Cultural Literacy''. Ho ...

and then with the flowering of the New Age

New Age is a range of Spirituality, spiritual or Religion, religious practices and beliefs that rapidly grew in Western world, Western society during the early 1970s. Its highly eclecticism, eclectic and unsystematic structure makes a precise d ...

movements. It has remained popular with these and with the wider population to this day. Since it was first published in 1923, ''The Prophet'' has never been out of print. It has been translated into more than 100 languages, making it among the top ten most translated books in history. It was one of the best-selling books of the twentieth century in the United States.

Elvis Presley

Elvis Aaron Presley (January 8, 1935 – August 16, 1977) was an American singer and actor. Referred to as the "King of Rock and Roll", he is regarded as Cultural impact of Elvis Presley, one of the most significant cultural figures of the ...

referred to Gibran's ''The Prophet'' for the rest of his life after receiving his first copy as a gift from his girlfriend June Juanico in July 1956. His marked-up copy still exists in Lebanon and another exists at the Elvis Presley museum in Düsseldorf

Düsseldorf is the capital city of North Rhine-Westphalia, the most populous state of Germany. It is the second-largest city in the state after Cologne and the List of cities in Germany with more than 100,000 inhabitants, seventh-largest city ...

. A line of poetry from ''Sand and Foam'' (1926), which reads "Half of what I say is meaningless, but I say it so that the other half may reach you," was used by John Lennon

John Winston Ono Lennon (born John Winston Lennon; 9 October 19408 December 1980) was an English singer-songwriter, musician and activist. He gained global fame as the founder, co-lead vocalist and rhythm guitarist of the Beatles. Lennon's ...

and placed, though in a slightly altered form, into the song "Julia

Julia may refer to:

People

*Julia (given name), including a list of people with the name

*Julia (surname), including a list of people with the name

*Julia gens, a patrician family of Ancient Rome

*Julia (clairvoyant) (fl. 1689), lady's maid of Qu ...

" from the Beatles

The Beatles were an English Rock music, rock band formed in Liverpool in 1960. The core lineup of the band comprised John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Ringo Starr. They are widely regarded as the Cultural impact of the Beatle ...

' 1968 album ''The Beatles

The Beatles were an English Rock music, rock band formed in Liverpool in 1960. The core lineup of the band comprised John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Ringo Starr. They are widely regarded as the Cultural impact of the Beatle ...

'' (a.k.a. "The White Album").

Johnny Cash

John R. Cash (born J. R. Cash; February 26, 1932 – September 12, 2003) was an American singer-songwriter. Most of his music contains themes of sorrow, moral tribulation, and redemption, especially songs from the later stages of his career. ...

recorded ''The Eye of the Prophet'' as an audio cassette book, and Cash can be heard talking about Gibran's work on a track called "Book Review" on his 2003 album '' Unearthed''. British singer David Bowie

David Robert Jones (8 January 194710 January 2016), known as David Bowie ( ), was an English singer, songwriter and actor. Regarded as one of the most influential musicians of the 20th century, Bowie was acclaimed by critics and musicians, pa ...

mentioned Gibran in the song "The Width of a Circle

"The Width of a Circle" is a song written by the English musician David Bowie in 1969 for his 1970 album, '' The Man Who Sold the World''. Recorded during the spring of 1970, it was released later that year in the United States and in April 1971 ...

" from Bowie's 1970 album '' The Man Who Sold the World''. Bowie used Gibran as a "hip reference", because Gibran's work ''A Tear and a Smile'' became popular in the hippie

A hippie, also spelled hippy, especially in British English, is someone associated with the counterculture of the 1960s, counterculture of the mid-1960s to early 1970s, originally a youth movement that began in the United States and spread to dif ...

counterculture of the 1960s. In 1978 Uruguayan musician Armando Tirelli recorded an album based on ''The Prophet''. In 2016 Gibran's fable "On Death" from ''The Prophet'' was composed in Hebrew by Gilad Hochman

Gilad Hochman (; born 26 July 1982 in Herzliya) is a Berlin-based Israeli composer of contemporary classical music.

Education

Hochman was born to an Odessa native father and a Paris native mother and currently resides in Berlin, Germany. He began ...

to the unique setting of soprano, theorbo

The theorbo is a plucked string instrument of the lute family, with an extended neck that houses the second pegbox. Like a lute, a theorbo has a curved-back sound box with a flat top, typically with one or three sound holes decorated with rose ...

and percussion, and it premiered in France under the title ''River of Silence''.

Gibran's influence extends far beyond the artistic world. In his 1961 inaugural address, President John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), also known as JFK, was the 35th president of the United States, serving from 1961 until his assassination in 1963. He was the first Roman Catholic and youngest person elected p ...

might have drawn inspiration from Gibran's 1925 essay