German Philosopher on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

German philosophy, meaning

In his writings,

In his writings,

In 1781,

In 1781,

File:Johann Gottlieb Fichte.jpg,

(1762–1814) File:Nb pinacoteca stieler friedrich wilhelm joseph von schelling.jpg,

(1775–1854) File:Hegel by Schlesinger.jpg,

(1770–1831)

File:Ludwig Andreas Feuerbach.jpg,

(1804–72) File:1908 David-Friedrich-Strauss.jpg,

(1808–74) File:Bruno Bauer.jpg,

(1809–82) File:MaxStirner1.svg,

(1806–56) File:Karl Marx 001.jpg,

(1818–83)

An

An

File:Edmund Husserl 1900.jpg, Edmund Husserl

(1859–1938) File:Karl Jaspers 1910.jpg, Karl Jaspers

(1883–1969) File:Heidegger 2 (1960).jpg,

(1889–1976) File:Hannah Arendt 1933.jpg, Hannah Arendt

(1906–1975)

In 1923, Carl Grünberg founded the University of Frankfurt Institute for Social Research, Institute for Social Research, drawing from

In 1923, Carl Grünberg founded the University of Frankfurt Institute for Social Research, Institute for Social Research, drawing from

Austrian Philosophy by Barry Smith

{{DEFAULTSORT:German Philosophy German philosophy, Culture of Germany German literature

philosophy

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, Value (ethics and social sciences), value, mind, and language. It is a rational an ...

in the German language

German (, ) is a West Germanic language in the Indo-European language family, mainly spoken in Western Europe, Western and Central Europe. It is the majority and Official language, official (or co-official) language in Germany, Austria, Switze ...

or philosophy by German people

Germans (, ) are the natives or inhabitants of Germany, or sometimes more broadly any people who are of German descent or native speakers of the German language. The Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany, constitution of Germany, imple ...

, in its diversity, is fundamental for both the analytic and continental

Continental may refer to:

Places

* Continental, Arizona, a small community in Pima County, Arizona, US

* Continental, Ohio, a small town in Putnam County, US

Arts and entertainment

* ''Continental'' (album), an album by Saint Etienne

* Continen ...

traditions. It covers figures such as Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (or Leibnitz; – 14 November 1716) was a German polymath active as a mathematician, philosopher, scientist and diplomat who is credited, alongside Sir Isaac Newton, with the creation of calculus in addition to ...

, Immanuel Kant

Immanuel Kant (born Emanuel Kant; 22 April 1724 – 12 February 1804) was a German Philosophy, philosopher and one of the central Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment thinkers. Born in Königsberg, Kant's comprehensive and systematic works ...

, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (27 August 1770 – 14 November 1831) was a 19th-century German idealist. His influence extends across a wide range of topics from metaphysical issues in epistemology and ontology, to political philosophy and t ...

, Karl Marx

Karl Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, political theorist, economist, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. He is best-known for the 1848 pamphlet '' The Communist Manifesto'' (written with Friedrich Engels) ...

, Friedrich Nietzsche

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (15 October 1844 – 25 August 1900) was a German philosopher. He began his career as a classical philology, classical philologist, turning to philosophy early in his academic career. In 1869, aged 24, Nietzsche bec ...

, Martin Heidegger

Martin Heidegger (; 26 September 1889 – 26 May 1976) was a German philosopher known for contributions to Phenomenology (philosophy), phenomenology, hermeneutics, and existentialism. His work covers a range of topics including metaphysics, art ...

, Ludwig Wittgenstein

Ludwig Josef Johann Wittgenstein ( ; ; 26 April 1889 – 29 April 1951) was an Austrian philosopher who worked primarily in logic, the philosophy of mathematics, the philosophy of mind, and the philosophy of language.

From 1929 to 1947, Witt ...

, the Vienna Circle

The Vienna Circle () of logical empiricism was a group of elite philosophers and scientists drawn from the natural and social sciences, logic and mathematics who met regularly from 1924 to 1936 at the University of Vienna, chaired by Moritz Sc ...

, and the Frankfurt School

The Frankfurt School is a school of thought in sociology and critical theory. It is associated with the University of Frankfurt Institute for Social Research, Institute for Social Research founded in 1923 at the University of Frankfurt am Main ...

, who now count among the most famous and studied philosophers of all time. They are central to major philosophical movements such as rationalism

In philosophy, rationalism is the Epistemology, epistemological view that "regards reason as the chief source and test of knowledge" or "the position that reason has precedence over other ways of acquiring knowledge", often in contrast to ot ...

, German idealism

German idealism is a philosophical movement that emerged in Germany in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. It developed out of the work of Immanuel Kant in the 1780s and 1790s, and was closely linked both with Romanticism and the revolutionary ...

, Romanticism

Romanticism (also known as the Romantic movement or Romantic era) was an artistic and intellectual movement that originated in Europe towards the end of the 18th century. The purpose of the movement was to advocate for the importance of subjec ...

, dialectical materialism

Dialectical materialism is a materialist theory based upon the writings of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels that has found widespread applications in a variety of philosophical disciplines ranging from philosophy of history to philosophy of scien ...

, existentialism

Existentialism is a family of philosophical views and inquiry that explore the human individual's struggle to lead an authentic life despite the apparent absurdity or incomprehensibility of existence. In examining meaning, purpose, and valu ...

, phenomenology

Phenomenology may refer to:

Art

* Phenomenology (architecture), based on the experience of building materials and their sensory properties

Philosophy

* Phenomenology (Peirce), a branch of philosophy according to Charles Sanders Peirce (1839� ...

, hermeneutics

Hermeneutics () is the theory and methodology of interpretation, especially the interpretation of biblical texts, wisdom literature, and philosophical texts. As necessary, hermeneutics may include the art of understanding and communication.

...

, logical positivism

Logical positivism, also known as logical empiricism or neo-positivism, was a philosophical movement, in the empiricist tradition, that sought to formulate a scientific philosophy in which philosophical discourse would be, in the perception of ...

, and critical theory

Critical theory is a social, historical, and political school of thought and philosophical perspective which centers on analyzing and challenging systemic power relations in society, arguing that knowledge, truth, and social structures are ...

. The Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard

Søren Aabye Kierkegaard ( , ; ; 5 May 1813 – 11 November 1855) was a Danes, Danish theologian, philosopher, poet, social critic, and religious author who is widely considered to be the first existentialist philosopher. He wrote critical tex ...

is often also included in surveys of German philosophy due to his extensive engagement with German thinkers.

Middle ages

In his writings,

In his writings, Albertus Magnus

Albertus Magnus ( 1200 – 15 November 1280), also known as Saint Albert the Great, Albert of Swabia, Albert von Bollstadt, or Albert of Cologne, was a German Dominican friar, philosopher, scientist, and bishop, considered one of the great ...

covers a wide range of topics in science and philosophy.

17th century

Jakob Böhme

Jakob Böhme (; ; 24 April 1575 – 17 November 1624) was a German philosopher, Christian mysticism, Christian mystic, and Lutheran Protestant Theology, theologian. He was considered an original thinker by many of his contemporaries within the L ...

(1575–1624), the Lutheran

Lutheranism is a major branch of Protestantism that emerged under the work of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German friar and Protestant Reformers, reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practices of the Catholic Church launched ...

philosopher who founded Christian theosophy

Christian theosophy, also known as Boehmian theosophy and theosophy, refers to a range of positions within Christianity that focus on the attainment of direct, unmediated knowledge of the nature of divinity and the origin and purpose of the unive ...

, influenced later key figures including F.W.J. Schelling and G.W.F. Hegel, who called him "the first German philosopher".

Leibniz

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (or Leibnitz; – 14 November 1716) was a German polymath active as a mathematician, philosopher, scientist and diplomat who is credited, alongside Sir Isaac Newton, with the creation of calculus in addition to ...

(1646–1716) was both a philosopher and a mathematician

A mathematician is someone who uses an extensive knowledge of mathematics in their work, typically to solve mathematical problems. Mathematicians are concerned with numbers, data, quantity, mathematical structure, structure, space, Mathematica ...

who wrote primarily in Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

and French. Leibniz, along with René Descartes

René Descartes ( , ; ; 31 March 1596 – 11 February 1650) was a French philosopher, scientist, and mathematician, widely considered a seminal figure in the emergence of modern philosophy and Modern science, science. Mathematics was paramou ...

and Baruch Spinoza

Baruch (de) Spinoza (24 November 163221 February 1677), also known under his Latinized pen name Benedictus de Spinoza, was a philosopher of Portuguese-Jewish origin, who was born in the Dutch Republic. A forerunner of the Age of Enlightenmen ...

, was one of the three great 17th century advocates of rationalism

In philosophy, rationalism is the Epistemology, epistemological view that "regards reason as the chief source and test of knowledge" or "the position that reason has precedence over other ways of acquiring knowledge", often in contrast to ot ...

. The work of Leibniz also anticipated modern logic

Logic is the study of correct reasoning. It includes both formal and informal logic. Formal logic is the study of deductively valid inferences or logical truths. It examines how conclusions follow from premises based on the structure o ...

and analytic philosophy

Analytic philosophy is a broad movement within Western philosophy, especially English-speaking world, anglophone philosophy, focused on analysis as a philosophical method; clarity of prose; rigor in arguments; and making use of formal logic, mat ...

, but his philosophy also looks back to the scholastic tradition, in which conclusions are produced by applying reason to first principles or a priori definitions rather than to empirical evidence

Empirical evidence is evidence obtained through sense experience or experimental procedure. It is of central importance to the sciences and plays a role in various other fields, like epistemology and law.

There is no general agreement on how the ...

.

Leibniz is noted for his optimism – his ''Théodicée

(from French: ''Essays of Theodicy on the Goodness of God, the Freedom of Man and the Origin of Evil''), more simply known as , is a book of philosophy by the German polymath Gottfried Leibniz. The book, published in 1710, introduced the te ...

'' tries to justify the apparent imperfections of the world by claiming that it is optimal among all possible worlds. It must be the best possible and most balanced world, because it was created by an all powerful and all knowing God, who would not choose to create an imperfect world if a better world could be known to him or possible to exist. In effect, apparent flaws that can be identified in this world must exist in every possible world, because otherwise God would have chosen to create the world that excluded those flaws.

Leibniz is also known for his theory of monads, as exposited in ''Monadologie

The ''Monadology'' (, 1714) is one of Gottfried Leibniz's best known works of his later philosophy. It is a short text which presents, in some 90 paragraphs, a metaphysics of simple substance theory, substances, or ''monad (philosophy), monads'' ...

''. They can also be compared to the corpuscles of the mechanical philosophy

Mechanism is the belief that natural wholes (principally living things) are similar to complicated machines or artifacts, composed of parts lacking any intrinsic relationship to each other.

The doctrine of mechanism in philosophy comes in two diff ...

of René Descartes and others. Monads are the ultimate elements of the universe

The universe is all of space and time and their contents. It comprises all of existence, any fundamental interaction, physical process and physical constant, and therefore all forms of matter and energy, and the structures they form, from s ...

. The monads are "substantial forms of being" with the following properties: they are eternal, indecomposable, individual, subject to their own laws, un-interacting, and each reflecting the entire universe in a pre-established harmony (a historically important example of panpsychism

In philosophy of mind, panpsychism () is the view that the mind or a mind-like aspect is a fundamental and ubiquitous feature of reality. It is also described as a theory that "the mind is a fundamental feature of the world which exists throug ...

). Monads are centers of force

In physics, a force is an influence that can cause an Physical object, object to change its velocity unless counterbalanced by other forces. In mechanics, force makes ideas like 'pushing' or 'pulling' mathematically precise. Because the Magnitu ...

; substance is force, while space

Space is a three-dimensional continuum containing positions and directions. In classical physics, physical space is often conceived in three linear dimensions. Modern physicists usually consider it, with time, to be part of a boundless ...

, matter

In classical physics and general chemistry, matter is any substance that has mass and takes up space by having volume. All everyday objects that can be touched are ultimately composed of atoms, which are made up of interacting subatomic pa ...

, and motion

In physics, motion is when an object changes its position with respect to a reference point in a given time. Motion is mathematically described in terms of displacement, distance, velocity, acceleration, speed, and frame of reference to an o ...

are merely phenomenal.

18th century

Wolff

Christian Wolff (1679–1754) was the most eminent German philosopher between Leibniz and Kant. His main achievement was a complete ''oeuvre'' on almost every scholarly subject of his time, displayed and unfolded according to his demonstrative-deductive, mathematical method, which perhaps represents the peak of Enlightenmentrationality

Rationality is the quality of being guided by or based on reason. In this regard, a person acts rationally if they have a good reason for what they do, or a belief is rational if it is based on strong evidence. This quality can apply to an ab ...

in Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

.

Wolff was one of the first to use German as a language of scholarly instruction and research, although he also wrote in Latin, so that an international audience could, and did, read him. A founding father of, among other fields, economics

Economics () is a behavioral science that studies the Production (economics), production, distribution (economics), distribution, and Consumption (economics), consumption of goods and services.

Economics focuses on the behaviour and interac ...

and public administration

Public administration, or public policy and administration refers to "the management of public programs", or the "translation of politics into the reality that citizens see every day",Kettl, Donald and James Fessler. 2009. ''The Politics of the ...

as academic disciplines, he concentrated especially in these fields, giving advice on practical matters to people in government, and stressing the professional nature of university education.

Kant

In 1781,

In 1781, Immanuel Kant

Immanuel Kant (born Emanuel Kant; 22 April 1724 – 12 February 1804) was a German Philosophy, philosopher and one of the central Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment thinkers. Born in Königsberg, Kant's comprehensive and systematic works ...

(1724–1804) published his ''Critique of Pure Reason

The ''Critique of Pure Reason'' (; 1781; second edition 1787) is a book by the German philosopher Immanuel Kant, in which the author seeks to determine the limits and scope of metaphysics. Also referred to as Kant's "First Critique", it was foll ...

'', in which he attempted to determine what we can and cannot know through the use of reason independent of all experience. Briefly, he came to the conclusion that we could come to know an external world through experience, but that what we could know about it was limited by the limited terms in which the mind can think: if we can only comprehend things in terms of cause and effect, then we can only know causes and effects. It follows from this that we can know the form of all possible experience independent of all experience, but nothing else, but we can never know the world from the "standpoint of nowhere" and therefore we can never know the world in its entirety, neither via reason nor experience.

Since the publication of his ''Critique'', Immanuel Kant has been considered one of the greatest influences in all of western philosophy. In the late 18th and early 19th century, one direct line of influence from Kant is German Idealism

German idealism is a philosophical movement that emerged in Germany in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. It developed out of the work of Immanuel Kant in the 1780s and 1790s, and was closely linked both with Romanticism and the revolutionary ...

.

19th century

German idealism

German idealism was aphilosophical movement

List of philosophies, schools of thought and philosophical movements.

A

Absurdism –

Academic skepticism – Accelerationism -

Achintya Bheda Abheda –

Action, philosophy of –

Actual idealism –

Actualism –

Advaita Vedanta ...

that emerged in Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. It developed out of the work of Immanuel Kant in the 1780s and 1790s, and was closely linked both with Romanticism

Romanticism (also known as the Romantic movement or Romantic era) was an artistic and intellectual movement that originated in Europe towards the end of the 18th century. The purpose of the movement was to advocate for the importance of subjec ...

and the revolutionary politics of the Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment (also the Age of Reason and the Enlightenment) was a European intellectual and philosophical movement active from the late 17th to early 19th century. Chiefly valuing knowledge gained through rationalism and empirici ...

. The most prominent German idealists in the movement, besides Kant, were Johann Gottlieb Fichte

Johann Gottlieb Fichte (; ; 19 May 1762 – 29 January 1814) was a German philosopher who became a founding figure of the philosophical movement known as German idealism, which developed from the theoretical and ethical writings of Immanuel Ka ...

(1762–1814), Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling

Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling (; 27 January 1775 – 20 August 1854), later (after 1812) von Schelling, was a German philosopher. Standard histories of philosophy make him the midpoint in the development of German idealism, situating him be ...

, (1775–1854) and Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (27 August 1770 – 14 November 1831) was a 19th-century German idealist. His influence extends across a wide range of topics from metaphysical issues in epistemology and ontology, to political philosophy and t ...

(1770–1831), who was the predominant figure in nineteenth century German philosophy. Also important were the Jena Romantics Friedrich Hölderlin

Johann Christian Friedrich Hölderlin (, ; ; 20 March 1770 – 7 June 1843) was a Germans, German poet and philosopher. Described by Norbert von Hellingrath as "the most German of Germans", Hölderlin was a key figure of German Romanticis ...

(1770–1843), Novalis

Georg Philipp Friedrich Freiherr von Hardenberg (2 May 1772 – 25 March 1801), pen name Novalis (; ), was a German nobility, German aristocrat and polymath, who was a poet, novelist, philosopher and Mysticism, mystic. He is regarded as an inf ...

(1772–1801), and Karl Wilhelm Friedrich Schlegel

Karl Wilhelm Friedrich (after 1814: von) Schlegel ( ; ; 10 March 1772 – 12 January 1829) was a German literary critic, philosopher, and Indologist. With his older brother, August Wilhelm Schlegel, he was one of the main figures of Jena Roma ...

(1772–1829). August Ludwig Hülsen

August Ludwig Hülsen (3 March 1765 – 24 September 1809), also known by the pseudonym Hegekern, was a German philosopher, writer and pedagogue of early German Romanticism. His thought played a role in the development of German idealism.

Life

H ...

, Friedrich Heinrich Jacobi

Friedrich Heinrich Jacobi (; ; 25 January 1743 – 10 March 1819) was a German philosopher, writer and socialite. He is best known for popularizing the concept of nihilism. He promoted the idea that it is the necessary result of Enlightenment th ...

, Gottlob Ernst Schulze, Karl Leonhard Reinhold

Karl Leonhard Reinhold (; ; 26 October 1757 – 10 April 1823) was an Austrian philosopher who helped to popularise the work of Immanuel Kant in the late 18th century. His "elementary philosophy" (''Elementarphilosophie'') also influenced German ...

, Salomon Maimon

Salomon Maimon (; ; ; ''Shlomo ben Yehoshua Maimon''; 1753 – 22 November 1800) was a philosopher born of Lithuanian Jewish parentage in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, present-day Belarus. His work was written in German and in Hebrew.

Bi ...

, Friedrich Schleiermacher

Friedrich Daniel Ernst Schleiermacher (; ; 21 November 1768 – 12 February 1834) was a German Reformed Church, Reformed theology, theologian, philosopher, and biblical scholar known for his attempt to reconcile the criticisms of the Age o ...

, and Arthur Schopenhauer

Arthur Schopenhauer ( ; ; 22 February 1788 – 21 September 1860) was a German philosopher. He is known for his 1818 work ''The World as Will and Representation'' (expanded in 1844), which characterizes the Phenomenon, phenomenal world as ...

also made major contributions.

Johann Gottlieb Fichte

Johann Gottlieb Fichte (; ; 19 May 1762 – 29 January 1814) was a German philosopher who became a founding figure of the philosophical movement known as German idealism, which developed from the theoretical and ethical writings of Immanuel Ka ...

(1762–1814) File:Nb pinacoteca stieler friedrich wilhelm joseph von schelling.jpg,

Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling

Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling (; 27 January 1775 – 20 August 1854), later (after 1812) von Schelling, was a German philosopher. Standard histories of philosophy make him the midpoint in the development of German idealism, situating him be ...

(1775–1854) File:Hegel by Schlesinger.jpg,

G. W. F. Hegel

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (27 August 1770 – 14 November 1831) was a 19th-century German idealism, German idealist. His influence extends across a wide range of topics from metaphysical issues in epistemology and ontology, to political phi ...

(1770–1831)

Fichte

As a representative ofsubjective idealism

Subjective idealism, or empirical idealism or immaterialism, is a form of philosophical monism that holds that only minds and mental contents exist. It entails and is generally identified or associated with immaterialism, the doctrine that m ...

, Fichte

Johann Gottlieb Fichte (; ; 19 May 1762 – 29 January 1814) was a German philosopher who became a founding figure of the philosophical movement known as German idealism, which developed from the theoretical and ethical writings of Immanuel Kan ...

rejected the Kantian "thing-in-itself

In Kantian philosophy, the thing-in-itself () is the status of objects as they are, independent of representation and observation. The concept of the thing-in-itself was introduced by the German philosopher Immanuel Kant, and over the following ...

." Fichte declares as the starting point of his philosophy the absolute "I," which itself creates the world with all its laws. Fichte understands the activity of this "I" as the activity of thought, as a process of self-awareness. Fichte recognizes absolute free will

Free will is generally understood as the capacity or ability of people to (a) choice, choose between different possible courses of Action (philosophy), action, (b) exercise control over their actions in a way that is necessary for moral respon ...

, God and the immortality

Immortality is the concept of eternal life. Some species possess "biological immortality" due to an apparent lack of the Hayflick limit.

From at least the time of the Ancient Mesopotamian religion, ancient Mesopotamians, there has been a con ...

of the soul

The soul is the purported Mind–body dualism, immaterial aspect or essence of a Outline of life forms, living being. It is typically believed to be Immortality, immortal and to exist apart from the material world. The three main theories that ...

. He sees in law

Law is a set of rules that are created and are enforceable by social or governmental institutions to regulate behavior, with its precise definition a matter of longstanding debate. It has been variously described as a science and as the ar ...

one of the manifestations of the “I".

Speaking with progressive slogans of defending the national sovereignty of the Germans from Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte (born Napoleone di Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French general and statesman who rose to prominence during the French Revolution and led Military career ...

, Fichte at the same time put forward chauvinist slogans, especially in his '' Addresses to the German Nation'' (1808), for which Fichte is regarded as one of the founders of modern German nationalism

German nationalism () is an ideological notion that promotes the unity of Germans and of the Germanosphere into one unified nation-state. German nationalism also emphasizes and takes pride in the patriotism and national identity of Germans as ...

.

Schelling

Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling

Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling (; 27 January 1775 – 20 August 1854), later (after 1812) von Schelling, was a German philosopher. Standard histories of philosophy make him the midpoint in the development of German idealism, situating him be ...

, who initially adhered to the ideas of Fichte, subsequently created his own philosophical system. Nature and consciousness, object and subject, Schelling argued, coincide in the Absolute; Schelling called his philosophy "the philosophy of identity."

In natural philosophy

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics, that is, nature and the physical universe, while ignoring any supernatural influence. It was dominant before the develop ...

, Schelling set himself the task of knowing the absolute, infinite spirit that lies at the basis of empirical visible nature. According to Schelling, the science of nature, based exclusively on reason, is designed to reveal the unconditioned cause that produces all natural phenomena. Schelling considered the absolute as a beginning capable of self-development through contradictions; in this sense, Schelling’s philosophy is characterized by some features of idealist dialectics

Dialectic (; ), also known as the dialectical method, refers originally to dialogue between people holding different points of view about a subject but wishing to arrive at the truth through reasoned argument. Dialectic resembles debate, but the ...

. In his early philosophy, around 1800, Schelling assigned a special role to art, in which, according to him, the reality of "higher being" is fully comprehended. Schelling interpreted art as "revelation." The artist, according to Schelling at this time, is a kind of mystical creature who creates in unconsciousness.

For Schelling, the main instrument of creativity is intuition

Intuition is the ability to acquire knowledge without recourse to conscious reasoning or needing an explanation. Different fields use the word "intuition" in very different ways, including but not limited to: direct access to unconscious knowledg ...

, "inner contemplation." In later life, Schelling evolves towards a mystical philosophy (''Mysterienlehre''). He was invited by the Prussian

Prussia (; ; Old Prussian: ''Prūsija'') was a German state centred on the North European Plain that originated from the 1525 secularization of the Prussian part of the State of the Teutonic Order. For centuries, the House of Hohenzoll ...

king Friedrich Wilhelm IV to the post of professor at the University of Berlin

The Humboldt University of Berlin (, abbreviated HU Berlin) is a public research university in the central borough of Mitte in Berlin, Germany.

The university was established by Frederick William III on the initiative of Wilhelm von Humbol ...

with the aim of combating the then-popular ideas of the left-liberal Young Hegelians

The Young Hegelians (), or Left Hegelians (''Linkshegelianer''), or the Hegelian Left (''die Hegelsche Linke''), were a group of German intellectuals who, in the decade or so after the death of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel in 1831, reacted to an ...

. It was during this period of his life that Schelling created the mystical "philosophy of revelation".

Hegel

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (27 August 1770 – 14 November 1831) was a 19th-century German idealist. His influence extends across a wide range of topics from metaphysical issues in epistemology and ontology, to political philosophy and t ...

is widely considered to be the greatest German idealist philosopher. According to Hegel’s system of objective or absolute idealism

Absolute idealism is chiefly associated with Friedrich Schelling and G. W. F. Hegel, both of whom were German idealist philosophers in the 19th century. The label has also been attached to others such as Josiah Royce, an American philosopher wh ...

, reality is self-movement, and its activity can be expressed only in thinking, in self-knowledge. It is internally contradictory, it moves and changes, passing into its opposite.

Hegel presents the dialectical process of self-development in three main stages, which are ordered conceptually, not temporally. The first stage is logical, was describes the "pre-natural" structure being in the "element of pure thinking." At this stage, the "absolute idea" appears as a system of logical concepts and categories, as a system of logic. This part of Hegel's philosophical system is set forth in his ''Science of Logic

''Science of Logic'' (), first published between 1812 and 1816, is the work in which Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel outlined his vision of logic. Hegel's logic is a system of ''dialectics'', i.e., a dialectical metaphysics: it is a development o ...

''. At the second stage, the "idea" is considered "in its externality" as nature. Hegel expounded his doctrine of nature in The ''Philosophy of Nature''. The highest, third step in the self-development of the idea is spirit, which Hegel, for the most part, presents as it increasingly comes to know itself in history. Hegel reveals this stage of development of the "absolute idea" in his work ''Philosophy of Spirit'' from the ''Encyclopedia of the Philosophical Sciences

The ''Encyclopaedia of the Philosophical Sciences in Basic Outline'' (), by Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (first published in 1817, second edition 1827, third edition 1830), is a work that presents an abbreviated version of Hegel's systematic ph ...

'' and in his lectures at the University of Berlin, many of which cover material not found in his published writings. The highest stage of spirit is presented as in the forms of art

Art is a diverse range of cultural activity centered around ''works'' utilizing creative or imaginative talents, which are expected to evoke a worthwhile experience, generally through an expression of emotional power, conceptual ideas, tec ...

, religion

Religion is a range of social system, social-cultural systems, including designated religious behaviour, behaviors and practices, morals, beliefs, worldviews, religious text, texts, sanctified places, prophecies, ethics in religion, ethics, or ...

, and philosophy

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, Value (ethics and social sciences), value, mind, and language. It is a rational an ...

.

The main works of Hegel are ''The Phenomenology of Spirit

''The Phenomenology of Spirit'' (or ''The Phenomenology of Mind''; ) is the most consequential philosophical work of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel. Hegel described the 1807 work, a ladder to the greater philosophica ...

'' (1807), ''Science of Logic

''Science of Logic'' (), first published between 1812 and 1816, is the work in which Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel outlined his vision of logic. Hegel's logic is a system of ''dialectics'', i.e., a dialectical metaphysics: it is a development o ...

'' (1812–1816), ''Encyclopedia of the Philosophical Sciences

The ''Encyclopaedia of the Philosophical Sciences in Basic Outline'' (), by Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (first published in 1817, second edition 1827, third edition 1830), is a work that presents an abbreviated version of Hegel's systematic ph ...

'' (''Logic,'' ''Philosophy of Nature,'' ''Philosophy of Spirit'') (1817), ''Elements of the Philosophy of Right

''Elements of the Philosophy of Right'' (or ''Outlines of the Philosophy of Right''; ) is a work by Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel published in 1820, though the book's original title page dates it to 1821. Hegel's most mature statement of his l ...

'' (1821).

German Romanticism

Immanuel Kant

Immanuel Kant (born Emanuel Kant; 22 April 1724 – 12 February 1804) was a German Philosophy, philosopher and one of the central Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment thinkers. Born in Königsberg, Kant's comprehensive and systematic works ...

's criticism of rationalism was a source of influence for early Romantic thought. Hamann's and Herder

A herder is a pastoralism, pastoral worker responsible for the care and management of a herd or flock of domestic animals, usually on extensive management, open pasture. It is particularly associated with nomadic pastoralism, nomadic or transhuma ...

's philosophical thoughts were also influential on both the proto-Romantic ''Sturm und Drang

(, ; usually translated as "storm and stress") was a proto-Romanticism, Romantic movement in German literature and Music of Germany, music that occurred between the late 1760s and early 1780s. Within the movement, individual subjectivity an ...

'' movement and on Romanticism itself.

The philosophy of Fichte

Johann Gottlieb Fichte (; ; 19 May 1762 – 29 January 1814) was a German philosopher who became a founding figure of the philosophical movement known as German idealism, which developed from the theoretical and ethical writings of Immanuel Kan ...

was of pivotal importance for the Romantics. The founder of German Romanticism, Friedrich Schlegel

Karl Wilhelm Friedrich (after 1814: von) Schlegel ( ; ; 10 March 1772 – 12 January 1829) was a German literary critic, philosopher, and Indologist. With his older brother, August Wilhelm Schlegel, he was one of the main figures of Jena Roma ...

, identified the "three sources of Romanticism": the French Revolution, Fichte's philosophy, and Goethe

Johann Wolfgang (von) Goethe (28 August 1749 – 22 March 1832) was a German polymath who is widely regarded as the most influential writer in the German language. His work has had a wide-ranging influence on Western literature, literary, Polit ...

's novel '' Wilhelm Meister''.

Schelling, who was associated with the Schlegel brothers

A brother (: brothers or brethren) is a man or boy who shares one or more parents with another; a male sibling. The female counterpart is a sister. Although the term typically refers to a familial relationship, it is sometimes used endearingl ...

in Jena

Jena (; ) is a List of cities and towns in Germany, city in Germany and the second largest city in Thuringia. Together with the nearby cities of Erfurt and Weimar, it forms the central metropolitan area of Thuringia with approximately 500,000 in ...

, took many of his philosophical and aesthetical

Aesthetics (also spelled esthetics) is the branch of philosophy concerned with the nature of beauty and taste (sociology), taste, which in a broad sense incorporates the philosophy of art.Slater, B. H.Aesthetics ''Internet Encyclopedia of Ph ...

ideas from the Romantics, and also influenced them on their own views: "In his philosophy of art, Schelling emerged from the subjective boundaries in which Kant concluded aesthetics, referring it only to features of judgment. Schelling's aesthetics, understanding the world as an artistic creation, has adopted a universal character and served as the basis for the teachings of the Romantic school." It is argued that Friedrich Schlegel's subjectivism

Subjectivism is the doctrine that "our own mental activity is the only unquestionable fact of our experience", instead of shared or communal, and that there is no external or objective truth.

While Thomas Hobbes was an early proponent of subjecti ...

and his glorification of the superior intellect as property of a select elite

In political and sociological theory, the elite (, from , to select or to sort out) are a small group of powerful or wealthy people who hold a disproportionate amount of wealth, privilege, political power, or skill in a group. Defined by the ...

influenced Schelling's doctrine of intellectual intuition, which György Lukács

György Lukács (born Bernát György Löwinger; ; ; 13 April 1885 – 4 June 1971) was a Hungarian Marxist philosopher, literary historian, literary critic, and Aesthetics, aesthetician. He was one of the founders of Western Marxism, an inter ...

called "the first manifestation of irrationalism

Irrationalism is a philosophical movement that emerged in the early 19th century, emphasizing the non-rational dimension of human life. As they reject logic, irrationalists argue that instinct and feelings are superior to reason in the research ...

". As much as Early Romanticism influenced the young Schelling's ''Naturphilosophie

"''Naturphilosophie''" (German for "nature-philosophy") is a term used in English-language philosophy to identify a current in the philosophical tradition of German idealism, as applied to the study of nature in the earlier 19th century. German ...

'' (his interpretation of nature

Nature is an inherent character or constitution, particularly of the Ecosphere (planetary), ecosphere or the universe as a whole. In this general sense nature refers to the Scientific law, laws, elements and phenomenon, phenomena of the physic ...

as an expression of spiritual powers), so did Late Romanticism influence the older Schelling's mythological

Myth is a genre of folklore consisting primarily of narratives that play a fundamental role in a society. For scholars, this is very different from the vernacular usage of the term "myth" that refers to a belief that is not true. Instead, the ...

and mysticist worldview (''Mysterienlehre'').

According to Lukács, Kierkegaard's views on philosophy and aesthetics were also an offshoot of Romanticism.

Schopenhauer

Arthur Schopenhauer ( ; ; 22 February 1788 – 21 September 1860) was a German philosopher. He is known for his 1818 work '' The World as Will and Representation'' (expanded in 1844), which characterizes the phenomenal world as the manife ...

also owed certain features of his philosophy to Romantic pessimism

Pessimism is a mental attitude in which an undesirable outcome is anticipated from a given situation. Pessimists tend to focus on the negatives of life in general. A common question asked to test for pessimism is "Is the glass half empty or half ...

: "Since salvation from suffering associated with the will is available through art only to a select few, Schopenhauer proposed another, more accessible way of overcoming the "I" – Buddhist

Buddhism, also known as Buddhadharma and Dharmavinaya, is an Indian religion and List of philosophies, philosophical tradition based on Pre-sectarian Buddhism, teachings attributed to the Buddha, a wandering teacher who lived in the 6th or ...

Nirvana

Nirvana, in the Indian religions (Jainism, Hinduism, Buddhism, and Sikhism), is the concept of an individual's passions being extinguished as the ultimate state of salvation, release, or liberation from suffering ('' duḥkha'') and from the ...

. In essence, Schopenhauer, although he was confident in the innovation of his revelations, did not give anything original here in comparison with the idealization of the Eastern world outlook by reactionary Romantics – it was indeed Friedrich Schlegel

Karl Wilhelm Friedrich (after 1814: von) Schlegel ( ; ; 10 March 1772 – 12 January 1829) was a German literary critic, philosopher, and Indologist. With his older brother, August Wilhelm Schlegel, he was one of the main figures of Jena Roma ...

who introduced this idealization in Germany with his ''Über die Sprache und Weisheit der Indier'' (''About the language and wisdom of the Indians'')."

In the opinion of György Lukács

György Lukács (born Bernát György Löwinger; ; ; 13 April 1885 – 4 June 1971) was a Hungarian Marxist philosopher, literary historian, literary critic, and Aesthetics, aesthetician. He was one of the founders of Western Marxism, an inter ...

, Friedrich Nietzsche

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (15 October 1844 – 25 August 1900) was a German philosopher. He began his career as a classical philology, classical philologist, turning to philosophy early in his academic career. In 1869, aged 24, Nietzsche bec ...

's importance as an irrationalist philosopher lay in that, while his early influences are to be found in Romanticism, he founded a modern irrationalism antithetical to that of the Romantics Even in his post-Schopenhauerian period, however, Nietzsche paid some tributes to Romanticism, for example borrowing the title of his book ''The Gay Science

''The Gay Science'' (; sometimes translated as ''The Joyful Wisdom'' or ''The Joyous Science'') is a book by Friedrich Nietzsche published in 1882, and followed by a second edition in 1887 after the completion of ''Thus Spoke Zarathustra'' and ...

'' (''Die fröhliche Wissenschaft'', 1882–87) from Friedrich Schlegel

Karl Wilhelm Friedrich (after 1814: von) Schlegel ( ; ; 10 March 1772 – 12 January 1829) was a German literary critic, philosopher, and Indologist. With his older brother, August Wilhelm Schlegel, he was one of the main figures of Jena Roma ...

's 1799 novel ''Lucinde''.

Lukács also emphasized that the emergence of organicism

Organicism is the philosophical position that states that the universe and its various parts (including human societies) ought to be considered alive and naturally ordered, much like a living organism.Gilbert, S. F., and S. Sarkar. 2000. "Emb ...

in philosophy received its impetus from Romanticism:

This view, that only 'organic growth', that is to say change through small and gradual reforms with the consent of the ruling class, was regarded as 'a natural principle', whereas every revolutionary upheaval received the dismissive tag of 'contrary to nature' gained a particularly extensive form in the course of the development of reactionary German romanticism ( Savigny, the historical law school, etc.). The antithesis of 'organic growth' and 'mechanical fabrication' was now elaborated: it constituted a defence of 'naturally grown' feudal privileges against the praxis of the French Revolution and the bourgeois ideologies underlying it, which were repudiated as mechanical, highbrow and abstract.

Wilhelm Dilthey

Wilhelm Dilthey (; ; 19 November 1833 – 1 October 1911) was a German historian, psychologist, sociologist, and hermeneutic philosopher, who held Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel's Chair in Philosophy at the University of Berlin. As a polymathi ...

, founder (along with Nietzsche, Simmel, and Klages) of the intuitionist

In the philosophy of mathematics, intuitionism, or neointuitionism (opposed to preintuitionism), is an approach where mathematics is considered to be purely the result of the constructive mental activity of humans rather than the discovery of ...

and irrationalist school of '' Lebensphilosophie'' in Germany, is credited with leading the Romantic revival in hermeneutics

Hermeneutics () is the theory and methodology of interpretation, especially the interpretation of biblical texts, wisdom literature, and philosophical texts. As necessary, hermeneutics may include the art of understanding and communication.

...

of the early 20th century. With his Schleiermacher

Friedrich Daniel Ernst Schleiermacher (; ; 21 November 1768 – 12 February 1834) was a German Reformed theologian, philosopher, and biblical scholar known for his attempt to reconcile the criticisms of the Enlightenment with traditional ...

biography and works on Novalis

Georg Philipp Friedrich Freiherr von Hardenberg (2 May 1772 – 25 March 1801), pen name Novalis (; ), was a German nobility, German aristocrat and polymath, who was a poet, novelist, philosopher and Mysticism, mystic. He is regarded as an inf ...

, Hölderlin, and others, he was one of the initiators of the Romantic renaissance in the imperial period. His discovery and annotation of the young Hegel

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (27 August 1770 – 14 November 1831) was a 19th-century German idealism, German idealist. His influence extends across a wide range of topics from metaphysical issues in epistemology and ontology, to political phi ...

's manuscripts became crucial to the vitalistic interpretation of Hegelian philosophy in the post-war period; his Goethe

Johann Wolfgang (von) Goethe (28 August 1749 – 22 March 1832) was a German polymath who is widely regarded as the most influential writer in the German language. His work has had a wide-ranging influence on Western literature, literary, Polit ...

study likewise ushered in the vitalistic interpretation of Goethe subsequently leading from Simmel and Gundolf to Klages.

Passivity was a key element of the Romantic mood in Germany, and it was brought by the Romantics into their own religious and philosophical views. The theologian Schleiermacher

Friedrich Daniel Ernst Schleiermacher (; ; 21 November 1768 – 12 February 1834) was a German Reformed theologian, philosopher, and biblical scholar known for his attempt to reconcile the criticisms of the Enlightenment with traditional ...

argued that the true essence of religion lies not in the active love of one’s neighbor, but in the passive contemplation of the infinite. In Schelling’s philosophical system, the creative absolute (God

In monotheistic belief systems, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator, and principal object of faith. In polytheistic belief systems, a god is "a spirit or being believed to have created, or for controlling some part of the un ...

) is immersed in the same passive, motionless state.

The only activity that the Romantics allowed is that in which there is almost no volitional element, that is, artistic creativity. They considered the representatives of art to be the happiest people, and in their works, along with knights chained in armor, poets, painters and musicians usually appear. Schelling considered an artist to be incomparably higher than a philosopher, because the secret of the world can be guessed from his minutia not by systematic logical thinking, but only by direct artistic intuition (" intellectual intuition"). Romantics loved to dream of such legendary countries, where all life with its everyday cares gave way to the eternal holiday of poetry.

The quietist and aestheticist mood of Romanticism, the reflection and idealization of the mood of the aristocracy

Aristocracy (; ) is a form of government that places power in the hands of a small, privileged ruling class, the aristocracy (class), aristocrats.

Across Europe, the aristocracy exercised immense Economy, economic, Politics, political, and soc ...

, again emerges in Schopenhauer

Arthur Schopenhauer ( ; ; 22 February 1788 – 21 September 1860) was a German philosopher. He is known for his 1818 work '' The World as Will and Representation'' (expanded in 1844), which characterizes the phenomenal world as the manife ...

’s philosophical system ''The World as Will and Representation

''The World as Will and Representation'' (''WWR''; , ''WWV''), sometimes translated as ''The World as Will and Idea'', is the central work of the German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer. The first edition was published in late 1818, with the date ...

,'' ending with a pessimistic chord. Schopenhauer argued that at the heart of the world and man lies the “ will to life,” which leads them to suffering and boredom, and happiness can be experienced only by those who free themselves from its oppressive domination. Even the artist is freed from the power of the will only temporarily. As soon as he turns into an ordinary mortal, his greedy will again raises its voice and throws him into the embrace of disappointment and boredom. Above the artist stands, therefore, the Hindu

Hindus (; ; also known as Sanātanīs) are people who religiously adhere to Hinduism, also known by its endonym Sanātana Dharma. Jeffery D. Long (2007), A Vision for Hinduism, IB Tauris, , pp. 35–37 Historically, the term has also be ...

sage or the holy ascetic

Asceticism is a lifestyle characterized by abstinence from worldly pleasures through self-discipline, self-imposed poverty, and simple living, often for the purpose of pursuing spiritual goals. Ascetics may withdraw from the world for their pra ...

.

Karl Marx and the Young Hegelians

Hegel was hugely influential throughout the nineteenth century; by its end, according toBertrand Russell

Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3rd Earl Russell, (18 May 1872 – 2 February 1970) was a British philosopher, logician, mathematician, and public intellectual. He had influence on mathematics, logic, set theory, and various areas of analytic ...

, "the leading academic philosophers, both in America and Britain, were largely Hegelian". His influence has continued in contemporary philosophy, especially in Continental philosophy

Continental philosophy is a group of philosophies prominent in 20th-century continental Europe that derive from a broadly Kantianism, Kantian tradition.Continental philosophers usually identify such conditions with the transcendental subject or ...

.

Right Hegelians

Among those influenced by Hegel immediately after his death in 1831, two distinct groups can be roughly divided into the politically and religiously radical 'left', or 'young', Hegelians and the more conservative 'right', or 'old', Hegelians. The Right Hegelians followed the master in believing that thedialectic

Dialectic (; ), also known as the dialectical method, refers originally to dialogue between people holding different points of view about a subject but wishing to arrive at the truth through reasoned argument. Dialectic resembles debate, but the ...

of history had come to an end—Hegel's ''Phenomenology of Spirit

''The Phenomenology of Spirit'' (or ''The Phenomenology of Mind''; ) is the most consequential philosophical work of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel. Hegel described the 1807 work, a ladder to the greater philosophical system of the '' Encyclopaed ...

'' reveals itself to be the culmination of history as the reader reaches its end. Here he meant that reason and freedom had reached their maximums as they were embodied by the existing Prussia

Prussia (; ; Old Prussian: ''Prūsija'') was a Germans, German state centred on the North European Plain that originated from the 1525 secularization of the Prussia (region), Prussian part of the State of the Teutonic Order. For centuries, ...

n state. And here the master’s claim was viewed as paradox, at best; the Prussian regime indeed provided extensive civil and social services, good universities, high employment and some industrialization, but it was ranked as rather backward politically compared with the more liberal constitutional monarchies of France and Britain.

Speculative theism was an 1830s movement closely related to, but distinguished from, Right Hegelianism. Its proponents ( Immanuel Hermann Fichte (1796–1879), Christian Hermann Weisse (1801–1866), and Hermann Ulrici (1806–1884) were united in their demand to recover the " personal God" after panrationalist Hegelianism. The movement featured elements of anti-psychologism In logic, anti-psychologism (also logical objectivism or logical realism) is the theory that logical truth does not depend upon the contents of human ideas, but exists independent of human ideas.

Overview

The anti-psychologistic treatment of logic ...

in the historiography of philosophy.

Young Hegelians

TheYoung Hegelians

The Young Hegelians (), or Left Hegelians (''Linkshegelianer''), or the Hegelian Left (''die Hegelsche Linke''), were a group of German intellectuals who, in the decade or so after the death of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel in 1831, reacted to an ...

drew on Hegel's idea that the purpose and promise of history was the total negation of everything conducive to restricting freedom and reason; and they proceeded to mount radical critiques, first of religion and then of the Prussian political system. They felt Hegel's apparent belief in the end of history conflicted with other aspects of his thought and that, contrary to his later thought, the dialectic was certainly ''not'' complete; this they felt was obvious given the irrationality of religious beliefs and the empirical lack of freedoms—especially political and religious freedoms—in existing Prussian society. They rejected anti-utopian aspects of his thought that "Old Hegelians" have interpreted to mean that the world has already essentially reached perfection. They included Ludwig Feuerbach

Ludwig Andreas von Feuerbach (; ; 28 July 1804 – 13 September 1872) was a German anthropologist and philosopher, best known for his book '' The Essence of Christianity'', which provided a critique of Christianity that strongly influenced ge ...

(1804–72), David Strauss

David Friedrich Strauss (; ; 27 January 1808 – 8 February 1874) was a German liberal Protestant theologian and writer, who influenced Christian Europe with his portrayal of the "historical Jesus", whose divine nature he explored via myth. St ...

(1808–74), Bruno Bauer

Bruno Bauer (; ; 6 September 180913 April 1882) was a German philosopher and theologian. As a student of G. W. F. Hegel, Bauer was a radical Rationalist in philosophy, politics and Biblical criticism. Bauer investigated the sources of the New T ...

(1809–82) and Max Stirner

Johann Kaspar Schmidt (; 25 October 1806 – 26 June 1856), known professionally as Max Stirner (; ), was a German post-Hegelian philosopher, dealing mainly with the Hegelian notion of social alienation and self-consciousness. Stirner is oft ...

(1806–56) among their ranks.

Karl Marx

Karl Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, political theorist, economist, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. He is best-known for the 1848 pamphlet '' The Communist Manifesto'' (written with Friedrich Engels) ...

(1818–83) often attended their meetings. He developed an interest in Hegelianism, French socialism, and British economic theory. He transformed the three into an essential work of economics called ''Das Kapital

''Capital: A Critique of Political Economy'' (), also known as ''Capital'' or (), is the most significant work by Karl Marx and the cornerstone of Marxian economics, published in three volumes in 1867, 1885, and 1894. The culmination of his ...

'', which consisted of a critical economic examination of capitalism. Marxism

Marxism is a political philosophy and method of socioeconomic analysis. It uses a dialectical and materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to analyse class relations, social conflict, ...

became one of the major forces on twentieth century world history.

It is important to note that the groups were not as unified or as self-conscious as the labels 'right' and 'left' make them appear. The term 'Right Hegelian', for example, was never actually used by those to whom it was later ascribed, namely, Hegel's direct successors at the Fredrick William University (now the Humboldt University of Berlin

The Humboldt University of Berlin (, abbreviated HU Berlin) is a public research university in the central borough of Mitte in Berlin, Germany.

The university was established by Frederick William III on the initiative of Wilhelm von Humbol ...

). (The term was first used by David Strauss to describe Bruno Bauer—who actually was a typically 'Left', or Young, Hegelian.)

Ludwig Feuerbach

Ludwig Andreas von Feuerbach (; ; 28 July 1804 – 13 September 1872) was a German anthropologist and philosopher, best known for his book '' The Essence of Christianity'', which provided a critique of Christianity that strongly influenced ge ...

(1804–72) File:1908 David-Friedrich-Strauss.jpg,

David Strauss

David Friedrich Strauss (; ; 27 January 1808 – 8 February 1874) was a German liberal Protestant theologian and writer, who influenced Christian Europe with his portrayal of the "historical Jesus", whose divine nature he explored via myth. St ...

(1808–74) File:Bruno Bauer.jpg,

Bruno Bauer

Bruno Bauer (; ; 6 September 180913 April 1882) was a German philosopher and theologian. As a student of G. W. F. Hegel, Bauer was a radical Rationalist in philosophy, politics and Biblical criticism. Bauer investigated the sources of the New T ...

(1809–82) File:MaxStirner1.svg,

Max Stirner

Johann Kaspar Schmidt (; 25 October 1806 – 26 June 1856), known professionally as Max Stirner (; ), was a German post-Hegelian philosopher, dealing mainly with the Hegelian notion of social alienation and self-consciousness. Stirner is oft ...

(1806–56) File:Karl Marx 001.jpg,

Karl Marx

Karl Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, political theorist, economist, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. He is best-known for the 1848 pamphlet '' The Communist Manifesto'' (written with Friedrich Engels) ...

(1818–83)

Friedrich Engels

Friedrich Engels

Friedrich Engels ( ;"Engels"

''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''.Young Hegelian The Young Hegelians (), or Left Hegelians (''Linkshegelianer''), or the Hegelian Left (''die Hegelsche Linke''), were a group of German intellectuals who, in the decade or so after the death of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel in 1831, reacted to an ...

originally, was a friend and associate of Marx, together with whom he developed the theory of ''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''.Young Hegelian The Young Hegelians (), or Left Hegelians (''Linkshegelianer''), or the Hegelian Left (''die Hegelsche Linke''), were a group of German intellectuals who, in the decade or so after the death of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel in 1831, reacted to an ...

scientific socialism

Scientific socialism in Marxism is the application of historical materialism to the development of socialism, as not just a practical and achievable outcome of historical processes, but the only possible outcome. It contrasts with utopian social ...

(communism

Communism () is a political sociology, sociopolitical, political philosophy, philosophical, and economic ideology, economic ideology within the history of socialism, socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a ...

) and the doctrines of dialectical

Dialectic (; ), also known as the dialectical method, refers originally to dialogue between people holding different points of view about a subject but wishing to arrive at the truth through reasoned argument. Dialectic resembles debate, but the c ...

and historical materialism

Historical materialism is Karl Marx's theory of history. Marx located historical change in the rise of Class society, class societies and the way humans labor together to make their livelihoods.

Karl Marx stated that Productive forces, techno ...

. His major works include '' The Holy Family'' (together with Marx, 1844) criticizing the Young Hegelians, ''The Condition of the Working Class in England

''The Condition of the Working Class in England'' () is an 1845 book by the German philosopher Friedrich Engels, a study of the industrial working class in Victorian England. Engels' first book, it was originally written in German; an English t ...

'' (1845), a study of the deprived conditions of the working class in Manchester

Manchester () is a city and the metropolitan borough of Greater Manchester, England. It had an estimated population of in . Greater Manchester is the third-most populous metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, with a population of 2.92&nbs ...

and Salford

Salford ( ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, city in Greater Manchester, England, on the western bank of the River Irwell which forms its boundary with Manchester city centre. Landmarks include the former Salford Town Hall, town hall, ...

based on Engels's personal observations, ''The Peasant War in Germany

''The Peasant War in Germany'' () by Friedrich Engels is a short account of the early-16th-century uprisings known as the German Peasants' War (1524–1525). It was written by Engels in London during the summer of 1850, following the revolution ...

'' (1850), an account of the early 16th-century uprising known as the German Peasants' War

The German Peasants' War, Great Peasants' War or Great Peasants' Revolt () was a widespread popular revolt in some German-speaking areas in Central Europe from 1524 to 1525. It was Europe's largest and most widespread popular uprising befor ...

with a comparison with the recent revolutionary uprisings of 1848–1849 across Europe, ''Anti-Dühring

''Anti-Dühring'' (, "Herr Eugen Dühring's Revolution in Science") is a book by Friedrich Engels, first published in German in 1877 in parts and then in 1878 in book form. It had previously been serialised in the newspaper '' Vorwärts.'' There ...

'' (1878) criticizing the philosophy of Eugen Dühring, '' Socialism: Utopian and Scientific'' (1880) studying the utopian socialists

Utopian socialism is the term often used to describe the first current of modern socialism and socialist thought as exemplified by the work of Henri de Saint-Simon, Charles Fourier, Étienne Cabet, and Robert Owen. Utopian socialism is oft ...

Charles Fourier

François Marie Charles Fourier (; ; 7 April 1772 – 10 October 1837) was a French philosopher, an influential early socialist thinker, and one of the founders of utopian socialism. Some of his views, held to be radical in his lifetime, have be ...

and Robert Owen

Robert Owen (; 14 May 1771 – 17 November 1858) was a Welsh textile manufacturer, philanthropist, political philosopher and social reformer, and a founder of utopian socialism and the cooperative movement, co-operative movement. He strove to ...

and their differences with Engels' version of socialism, ''Dialectics of Nature

''Dialectics of Nature'' () is an unfinished 1883 work by Friedrich Engels that applies Marxist ideas – particularly those of dialectical materialism – to nature.

History and contents

Engels wrote most of the manuscript between ...

'' (1883) applying Marxist

Marxism is a political philosophy and method of socioeconomic analysis. It uses a dialectical and materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to analyse class relations, social conflic ...

ideas, particularly those of dialectical materialism

Dialectical materialism is a materialist theory based upon the writings of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels that has found widespread applications in a variety of philosophical disciplines ranging from philosophy of history to philosophy of scien ...

, to science

Science is a systematic discipline that builds and organises knowledge in the form of testable hypotheses and predictions about the universe. Modern science is typically divided into twoor threemajor branches: the natural sciences, which stu ...

, and ''The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State

''The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State: in the Light of the Researches of Lewis H. Morgan'' () is an 1884 anthropological treatise by Friedrich Engels. It is partially based on notes by Karl Marx to Lewis H. Morgan's book ''Anc ...

'' (1884) arguing that the family

Family (from ) is a Social group, group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or Affinity (law), affinity (by marriage or other relationship). It forms the basis for social order. Ideally, families offer predictabili ...

is an ever-changing institution that has been shaped by capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their use for the purpose of obtaining profit. This socioeconomic system has developed historically through several stages and is defined by ...

. It contains an historical view of the family in relation to issues of class, female subjugation and private property.

Dietzgen

Joseph Dietzgen

Peter Josef Dietzgen (December 9, 1828April 15, 1888) was a German socialist philosophy, philosopher, Marxist, and journalist.

Dietzgen was born in Hennef (Sieg), Blankenberg in the Rhine Province of Prussia. He was the first of five children o ...

was a German leatherworker and social democrat, who independently developed a number of questions of philosophy and came to conclusions very close to the dialectical materialism of Marx and Engels. After the revolution of 1848

The revolutions of 1848, known in some countries as the springtime of the peoples or the springtime of nations, were a series of revolutions throughout Europe over the course of more than one year, from 1848 to 1849. It remains the most widespre ...

he emigrated to America

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

and in 1864 in search of work, he went to Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

. Working in a tannery in St. Petersburg

Saint Petersburg, formerly known as Petrograd and later Leningrad, is the second-largest city in Russia after Moscow. It is situated on the River Neva, at the head of the Gulf of Finland on the Baltic Sea. The city had a population of 5,601, ...

, Dietzgen devoted all his leisure time to works in the field of philosophy, political economy

Political or comparative economy is a branch of political science and economics studying economic systems (e.g. Marketplace, markets and national economies) and their governance by political systems (e.g. law, institutions, and government). Wi ...

and socialism

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

. In Russia he wrote a large philosophical treatise, ''The Essence of the Mental Labor of Man'', a review of the first volume of ''Capital

Capital and its variations may refer to:

Common uses

* Capital city, a municipality of primary status

** Capital region, a metropolitan region containing the capital

** List of national capitals

* Capital letter, an upper-case letter

Econom ...

'' by Karl Marx

Karl Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, political theorist, economist, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. He is best-known for the 1848 pamphlet '' The Communist Manifesto'' (written with Friedrich Engels) ...

. In 1869 Dietzgen returned to Germany, and then moved again to America, where he wrote his philosophical works ''Excursions of a Socialist in the Field of the Theory of Knowledge'' and ''Acquisition of Philosophy''.

Marx highly appreciated Dietzgen as a thinker. Noting a number of mistakes and confusion in his views, Marx wrote that Dietzgen expressed “many excellent thoughts, and as a product of the independent thinking of a worker, worthy of amazement.” Engels gave Dietzgen the same high assessment. “And it is remarkable,” wrote Engels, “that we were not alone in discovering this materialistic dialectic, which for many years now has been our best tool of labor and our sharpest weapon; the German worker Joseph Dietzgen rediscovered it independently of us and even independently of Hegel.”

The "academic socialists"

The '' Kathedersozialismus'' movement (academic socialism) was a theoretical and political trend that arose in the second half of the 19th century in German universities. The “academic socialists” – mostly economists and sociologists belonging to the “ Historical School” – tried to prove that a people’s state could be built in Prussian Germany through reform, without the revolutionary overthrow ofcapitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their use for the purpose of obtaining profit. This socioeconomic system has developed historically through several stages and is defined by ...

and of the state

State most commonly refers to:

* State (polity), a centralized political organization that regulates law and society within a territory

**Sovereign state, a sovereign polity in international law, commonly referred to as a country

**Nation state, a ...

, thus rejecting the Marxist

Marxism is a political philosophy and method of socioeconomic analysis. It uses a dialectical and materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to analyse class relations, social conflic ...

notion of class struggle

In political science, the term class conflict, class struggle, or class war refers to the economic antagonism and political tension that exist among social classes because of clashing interests, competition for limited resources, and inequali ...

. In 1872 the ''Kathedersozialisten'' formed in Germany the "Union of Social Policy". Their ideas were similar to those of the Fabian socialists in Britain.

“Academic socialism” supported a variation of Otto von Bismarck

Otto, Prince of Bismarck, Count of Bismarck-Schönhausen, Duke of Lauenburg (; born ''Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck''; 1 April 1815 – 30 July 1898) was a German statesman and diplomat who oversaw the unification of Germany and served as ...

’s welfare state

A welfare state is a form of government in which the State (polity), state (or a well-established network of social institutions) protects and promotes the economic and social well-being of its citizens, based upon the principles of equal oppor ...

. The most notable “academic socialists” in Germany were Bruno Hildebrand, who was openly against Marx and Engels, Gustav von Schmoller

}

Gustav Friedrich (after 1908: von) Schmoller (; 24 June 1838 – 27 June 1917) was the leader of the "younger" German historical school of economics.

He was a leading ''Sozialpolitiker'' (more derisively, ''Kathedersozialist'', "Socialist of ...

, Adolph Wagner, Lujo Brentano, Johann Plenge, Hans Delbrück, Ferdinand Toennies and Werner Sombart Werner may refer to:

People

* Werner (name), origin of the name and people with this name as surname and given name

Fictional characters

* Werner (comics), a German comic book character

* Werner Von Croy, a fictional character in the ''Tomb Rai ...

. In the labor movement in Germany, their line was supported by Ferdinand Lassalle

Ferdinand Johann Gottlieb Lassalle (born Lassal; 11 April 1825 – 31 August 1864) was a German jurist, philosopher, socialist, and political activist. Remembered as an initiator of the German labour movement, he developed the theory of state s ...

.

Dühring

Eugen Dühring was a German professor ofmechanics

Mechanics () is the area of physics concerned with the relationships between force, matter, and motion among Physical object, physical objects. Forces applied to objects may result in Displacement (vector), displacements, which are changes of ...

, philosopher and economist. In philosophy he was an eclectic who combined positivism

Positivism is a philosophical school that holds that all genuine knowledge is either true by definition or positivemeaning '' a posteriori'' facts derived by reason and logic from sensory experience.John J. Macionis, Linda M. Gerber, ''Soci ...

, mechanistic materialism and idealism. He criticized the views of Friedrich Engels

Friedrich Engels ( ;"Engels"

''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''.Social Democrats Social democracy is a social, economic, and political philosophy within socialism that supports political and economic democracy and a gradualist, reformist, and democratic approach toward achieving social equality. In modern practice, s ...

, in particular by ''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''.Social Democrats Social democracy is a social, economic, and political philosophy within socialism that supports political and economic democracy and a gradualist, reformist, and democratic approach toward achieving social equality. In modern practice, s ...

Eduard Bernstein

Eduard Bernstein (; 6 January 1850 – 18 December 1932) was a German Marxist theorist and politician. A prominent member of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD), he has been both condemned and praised as a "Revisionism (Marxism), revisi ...

. Engels dedicated his entire book ''Anti-Dühring

''Anti-Dühring'' (, "Herr Eugen Dühring's Revolution in Science") is a book by Friedrich Engels, first published in German in 1877 in parts and then in 1878 in book form. It had previously been serialised in the newspaper '' Vorwärts.'' There ...

'' to criticizing Dühring's views.

Schopenhauer

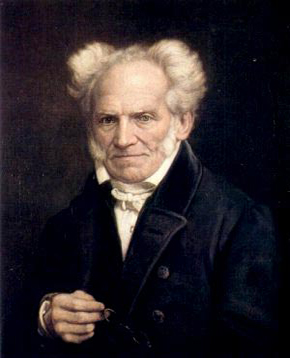

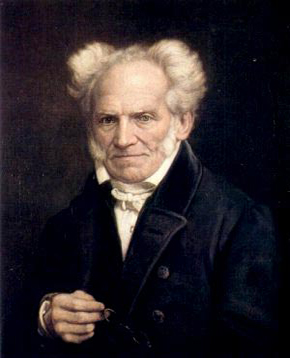

An

An idiosyncratic

An idiosyncrasy is a unique feature of something. The term is often used to express peculiarity.

Etymology

The term "idiosyncrasy" originates from Greek ', "a peculiar temperament, habit of body" (from ', "one's own", ', "with" and ', "blend ...

opponent of German idealism, particularly Hegel's thought, was Arthur Schopenhauer

Arthur Schopenhauer ( ; ; 22 February 1788 – 21 September 1860) was a German philosopher. He is known for his 1818 work ''The World as Will and Representation'' (expanded in 1844), which characterizes the Phenomenon, phenomenal world as ...

(1788 –1860). He was influenced by Eastern philosophy

Eastern philosophy (also called Asian philosophy or Oriental philosophy) includes the various philosophies that originated in East and South Asia, including Chinese philosophy, Japanese philosophy, Korean philosophy, and Vietnamese philoso ...

, particularly Buddhism