Georges Cuvier on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Jean Léopold Nicolas Frédéric, baron Cuvier (23 August 1769 – 13 May 1832), known as Georges Cuvier (; ), was a French

Jean Léopold Nicolas Frédéric Cuvier was born in Montbéliard, where his Protestant ancestors had lived since the time of the Reformation. His mother was Anne Clémence Chatel; his father, Jean-Georges Cuvier, was a lieutenant in the Swiss Guards and a bourgeois of the town of Montbéliard. At the time, the town, which would be annexed to France on 10 October 1793, belonged to the Sovereign County of Montbéliard (in

Jean Léopold Nicolas Frédéric Cuvier was born in Montbéliard, where his Protestant ancestors had lived since the time of the Reformation. His mother was Anne Clémence Chatel; his father, Jean-Georges Cuvier, was a lieutenant in the Swiss Guards and a bourgeois of the town of Montbéliard. At the time, the town, which would be annexed to France on 10 October 1793, belonged to the Sovereign County of Montbéliard (in  At the age of 10, soon after entering the gymnasium, he encountered a copy of Conrad Gessner's ''Historiae Animalium'', the work that first sparked his interest in

At the age of 10, soon after entering the gymnasium, he encountered a copy of Conrad Gessner's ''Historiae Animalium'', the work that first sparked his interest in  Cuvier then devoted himself more especially to three lines of inquiry: (i) the structure and classification of the ''

Cuvier then devoted himself more especially to three lines of inquiry: (i) the structure and classification of the ''

Early in his tenure at the National Museum in Paris, Cuvier published studies of fossil bones in which he argued that they belonged to large, extinct quadrupeds. His first two such publications were those identifying mammoth and mastodon fossils as belonging to extinct species rather than modern elephants and the study in which he identified the ''Megatherium'' as a giant, extinct species of sloth. His primary evidence for his identifications of mammoths and mastodons as separate, extinct species was the structure of their jaws and teeth. His primary evidence that the ''Megatherium'' fossil had belonged to a massive sloth came from his comparison of its skull with those of extant sloth species.

Cuvier wrote of his paleontological method that "the form of the tooth leads to the form of the condyle, that of the scapula to that of the nails, just as an equation of a curve implies all of its properties; and, just as in taking each property separately as the basis of a special equation we are able to return to the original equation and other associated properties, similarly, the nails, the scapula, the condyle, the femur, each separately reveal the tooth or each other; and by beginning from each of them the thoughtful professor of the laws of organic economy can reconstruct the entire animal."

However, Cuvier's actual method was heavily dependent on the comparison of fossil specimens with the anatomy of extant species in the necessary context of his vast knowledge of animal anatomy and access to unparalleled natural history collections in Paris. This reality, however, did not prevent the rise of a popular legend that Cuvier could reconstruct the entire bodily structures of extinct animals given only a few fragments of bone.

At the time Cuvier presented his 1796 paper on living and fossil elephants, it was still widely believed that no species of animal had ever become extinct. Authorities such as Buffon had claimed that fossils found in Europe of animals such as the woolly rhinoceros and the mammoth were remains of animals still living in the tropics (i.e.

Early in his tenure at the National Museum in Paris, Cuvier published studies of fossil bones in which he argued that they belonged to large, extinct quadrupeds. His first two such publications were those identifying mammoth and mastodon fossils as belonging to extinct species rather than modern elephants and the study in which he identified the ''Megatherium'' as a giant, extinct species of sloth. His primary evidence for his identifications of mammoths and mastodons as separate, extinct species was the structure of their jaws and teeth. His primary evidence that the ''Megatherium'' fossil had belonged to a massive sloth came from his comparison of its skull with those of extant sloth species.

Cuvier wrote of his paleontological method that "the form of the tooth leads to the form of the condyle, that of the scapula to that of the nails, just as an equation of a curve implies all of its properties; and, just as in taking each property separately as the basis of a special equation we are able to return to the original equation and other associated properties, similarly, the nails, the scapula, the condyle, the femur, each separately reveal the tooth or each other; and by beginning from each of them the thoughtful professor of the laws of organic economy can reconstruct the entire animal."

However, Cuvier's actual method was heavily dependent on the comparison of fossil specimens with the anatomy of extant species in the necessary context of his vast knowledge of animal anatomy and access to unparalleled natural history collections in Paris. This reality, however, did not prevent the rise of a popular legend that Cuvier could reconstruct the entire bodily structures of extinct animals given only a few fragments of bone.

At the time Cuvier presented his 1796 paper on living and fossil elephants, it was still widely believed that no species of animal had ever become extinct. Authorities such as Buffon had claimed that fossils found in Europe of animals such as the woolly rhinoceros and the mammoth were remains of animals still living in the tropics (i.e.

Cuvier came to believe that most, if not all, the animal fossils he examined were remains of species that had become extinct. Near the end of his 1796 paper on living and fossil elephants, he said:

:''All of these facts, consistent among themselves, and not opposed by any report, seem to me to prove the existence of a world previous to ours, destroyed by some kind of catastrophe.''

Contrary to many natural scientists' beliefs at the time, Cuvier believed that animal extinction was not a product of

Cuvier came to believe that most, if not all, the animal fossils he examined were remains of species that had become extinct. Near the end of his 1796 paper on living and fossil elephants, he said:

:''All of these facts, consistent among themselves, and not opposed by any report, seem to me to prove the existence of a world previous to ours, destroyed by some kind of catastrophe.''

Contrary to many natural scientists' beliefs at the time, Cuvier believed that animal extinction was not a product of

Cuvier's most admired work was his '' Le Règne Animal''. It appeared in four octavo volumes in 1817; a second edition in five volumes was brought out in 1829–1830. In this classic work, Cuvier presented the results of his life's research into the structure of living and fossil animals. With the exception of the section on

Cuvier's most admired work was his '' Le Règne Animal''. It appeared in four octavo volumes in 1817; a second edition in five volumes was brought out in 1829–1830. In this classic work, Cuvier presented the results of his life's research into the structure of living and fossil animals. With the exception of the section on

Apart from his own original investigations in zoology and

Apart from his own original investigations in zoology and

(text in French) 234

*''Mémoires pour servir à l'histoire et à l'anatomie des mollusques'' (1817) *''Éloges historiques des membres de l'Académie royale des sciences, lus dans les séances de l'Institut royal de France par M. Cuvier'' (3 volumes, 1819–1827

Vol. 1Vol. 2

an

Vol. 3

*''Théorie de la terre'' (1821) ::--- ''Essay on the theory of the earth''

1813

1815

trans. Robert Kerr.

''Recherches sur les ossemens fossiles''

1821–1823 (5 vols). *''Discours sur les révolutions de la surface du globe et sur les changements qu'elles ont produits dans le règne animal'' (1822). New edition: Christian Bourgeois, Paris, 1985

(text in French)

*''Histoire des progrès des sciences naturelles depuis 1789 jusqu'à ce jour'' (5 volumes, 1826–1836) *''Histoire naturelle des poissons'' (11 volumes, 1828–1848), continued by

"''Galeocerdo cuvier''"

'' FishBase''. July 2011 version.

Profile of Cuvier and his work on extinction and taxonomy. * * * *

Victorian Web Bio

Infoscience

{{DEFAULTSORT:Cuvier, Georges French naturalists 19th-century French geologists French paleontologists 1769 births 1832 deaths 19th-century French anthropologists French ichthyologists French malacologists French ornithologists French science writers French taxonomists Paleozoologists Teuthologists French barons Catastrophism Critics of Lamarckism Grand Officers of the Legion of Honour Members of the French Academy of Sciences Members of the Académie Française Members of the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres Chancellors of the University of Paris Academic staff of the Collège de France Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences Foreign members of the Royal Society Honorary members of the Saint Petersburg Academy of Sciences Members of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences Members of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences Members of the Chamber of Peers of the July Monarchy French Lutherans Scientists from Montbéliard Deaths from cholera in France Burials at Père Lachaise Cemetery French male non-fiction writers 18th-century French zoologists 19th-century French zoologists National Museum of Natural History (France) people People educated at the Karlsschule Stuttgart

naturalist

Natural history is a domain of inquiry involving organisms, including animals, fungi, and plants, in their natural environment, leaning more towards observational than experimental methods of study. A person who studies natural history is cal ...

and zoologist

Zoology ( , ) is the scientific study of animals. Its studies include the structure, embryology, classification, habits, and distribution of all animals, both living and extinct, and how they interact with their ecosystems. Zoology is one ...

, sometimes referred to as the "founding father of paleontology". Cuvier was a major figure in natural sciences research in the early 19th century and was instrumental in establishing the fields of comparative anatomy

Comparative anatomy is the study of similarities and differences in the anatomy of different species. It is closely related to evolutionary biology and phylogeny (the evolution of species).

The science began in the classical era, continuing in t ...

and paleontology

Paleontology, also spelled as palaeontology or palæontology, is the scientific study of the life of the past, mainly but not exclusively through the study of fossils. Paleontologists use fossils as a means to classify organisms, measure ge ...

through his work in comparing living animals with fossils.

Cuvier's work is considered the foundation of vertebrate paleontology

Vertebrate paleontology is the subfield of paleontology that seeks to discover, through the study of fossilized remains, the behavior, reproduction and appearance of extinct vertebrates (animals with vertebrae and their descendants). It also t ...

, and he expanded Linnaean taxonomy

Linnaean taxonomy can mean either of two related concepts:

# The particular form of biological classification (taxonomy) set up by Carl Linnaeus, as set forth in his ''Systema Naturae'' (1735) and subsequent works. In the taxonomy of Linnaeus th ...

by grouping classes into phyla

Phyla, the plural of ''phylum'', may refer to:

* Phylum, a biological taxon between Kingdom and Class

* by analogy, in linguistics, a large division of possibly related languages, or a major language family which is not subordinate to another

Phy ...

and incorporating both fossils and living species into the classification. Cuvier is also known for establishing extinction

Extinction is the termination of an organism by the death of its Endling, last member. A taxon may become Functional extinction, functionally extinct before the death of its last member if it loses the capacity to Reproduction, reproduce and ...

as a fact—at the time, extinction was considered by many of Cuvier's contemporaries to be merely controversial speculation. In his ''Essay on the Theory of the Earth'' (1813) Cuvier proposed that now-extinct species had been wiped out by periodic catastrophic flooding events. In this way, Cuvier became the most influential proponent of catastrophism in geology

Geology (). is a branch of natural science concerned with the Earth and other astronomical objects, the rocks of which they are composed, and the processes by which they change over time. Modern geology significantly overlaps all other Earth ...

in the early 19th century. His study of the strata

In geology and related fields, a stratum (: strata) is a layer of Rock (geology), rock or sediment characterized by certain Lithology, lithologic properties or attributes that distinguish it from adjacent layers from which it is separated by v ...

of the Paris basin with Alexandre Brongniart established the basic principles of biostratigraphy.

Among his other accomplishments, Cuvier established that elephant-like bones found in North America belonged to an extinct animal he later would name a "mastodon

A mastodon, from Ancient Greek μαστός (''mastós''), meaning "breast", and ὀδούς (''odoús'') "tooth", is a member of the genus ''Mammut'' (German for 'mammoth'), which was endemic to North America and lived from the late Miocene to ...

", and that a large skeleton dug up in present-day Argentina

Argentina, officially the Argentine Republic, is a country in the southern half of South America. It covers an area of , making it the List of South American countries by area, second-largest country in South America after Brazil, the fourt ...

was of a giant, prehistoric ground sloth, which he named ''Megatherium

''Megatherium'' ( ; from Greek () 'great' + () 'beast') is an extinct genus of ground sloths endemic to South America that lived from the Early Pliocene through the end of the Late Pleistocene. It is best known for the elephant-sized type spe ...

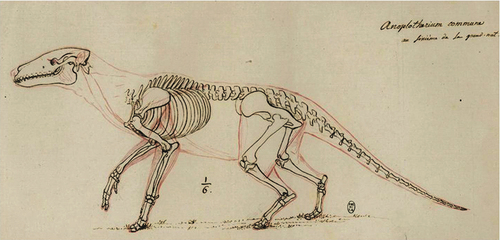

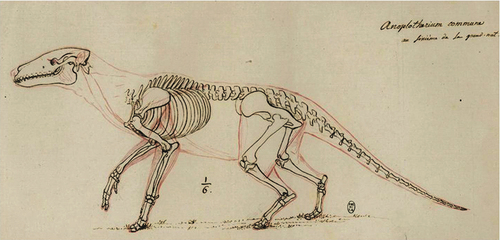

''. He also established two ungulate genera from the Paris Basin named '' Palaeotherium'' and '' Anoplotherium'' based on fragmentary remains alone, although more complete remains were later uncovered. He named the pterosaur '' Pterodactylus'', described (but did not discover or name) the aquatic reptile '' Mosasaurus'', and was one of the first people to suggest the earth had been dominated by reptiles, rather than mammals, in prehistoric times.

Cuvier is also remembered for strongly opposing theories of evolution, which at the time (before Darwin's theory) were mainly proposed by Jean-Baptiste de Lamarck

Jean-Baptiste Pierre Antoine de Monet, chevalier de Lamarck (1 August 1744 – 18 December 1829), often known simply as Lamarck (; ), was a French naturalist, biologist, academic, and soldier. He was an early proponent of the idea that biologi ...

and Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire. Cuvier believed there was no evidence for evolution

Evolution is the change in the heritable Phenotypic trait, characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. It occurs when evolutionary processes such as natural selection and genetic drift act on genetic variation, re ...

, but rather evidence for cyclical creations and destructions of life forms by global extinction events such as deluges. In 1830, Cuvier and Geoffroy engaged in a famous debate, which is said to exemplify the two major deviations in biological thinking at the time – whether animal structure was due to function or (evolutionary) morphology. Cuvier supported function and rejected Lamarck's thinking.

Cuvier also conducted racial studies which provided part of the foundation for scientific racism

Scientific racism, sometimes termed biological racism, is the pseudoscience, pseudoscientific belief that the Human, human species is divided into biologically distinct taxa called "race (human categorization), races", and that empirical evi ...

, and published work on the supposed differences between racial groups' physical properties and mental abilities. Cuvier subjected Sarah Baartman to examinations alongside other French naturalists during a period in which she was held captive in a state of neglect. Cuvier examined Baartman shortly before her death, and conducted a dissection following her death that disparagingly compared her physical features to those of monkeys.

His most famous work among the general public was the Preliminary Discourse of the Recherches sur les ossemens fossiles de 1812, which was published as a separate in 1821 and in book form in 1825, with the title Discours sur les révolutions de la surface du Globe. The evolution of his ideas on Comparative Anatomy, Paleontology, and pre-Darwinian Natural History can be seen by comparing these works in the form of a Variorum. Another important work was '' Le Règne Animal'' (1817; English: ''The Animal Kingdom''). In 1819, he was created a peer for life in honour of his scientific contributions. Thereafter, he was known as Baron Cuvier. He died in Paris during an epidemic of cholera

Cholera () is an infection of the small intestine by some Strain (biology), strains of the Bacteria, bacterium ''Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea last ...

. Some of Cuvier's most influential followers were Louis Agassiz

Jean Louis Rodolphe Agassiz ( ; ) FRS (For) FRSE (May 28, 1807 – December 14, 1873) was a Swiss-born American biologist and geologist who is recognized as a scholar of Earth's natural history.

Spending his early life in Switzerland, he recei ...

on the continent and in the United States, and Richard Owen

Sir Richard Owen (20 July 1804 – 18 December 1892) was an English biologist, comparative anatomy, comparative anatomist and paleontology, palaeontologist. Owen is generally considered to have been an outstanding naturalist with a remarkabl ...

in Britain. His name is one of the 72 names inscribed on the Eiffel Tower.

Biography

Jean Léopold Nicolas Frédéric Cuvier was born in Montbéliard, where his Protestant ancestors had lived since the time of the Reformation. His mother was Anne Clémence Chatel; his father, Jean-Georges Cuvier, was a lieutenant in the Swiss Guards and a bourgeois of the town of Montbéliard. At the time, the town, which would be annexed to France on 10 October 1793, belonged to the Sovereign County of Montbéliard (in

Jean Léopold Nicolas Frédéric Cuvier was born in Montbéliard, where his Protestant ancestors had lived since the time of the Reformation. His mother was Anne Clémence Chatel; his father, Jean-Georges Cuvier, was a lieutenant in the Swiss Guards and a bourgeois of the town of Montbéliard. At the time, the town, which would be annexed to France on 10 October 1793, belonged to the Sovereign County of Montbéliard (in personal union

A personal union is a combination of two or more monarchical states that have the same monarch while their boundaries, laws, and interests remain distinct. A real union, by contrast, involves the constituent states being to some extent in ...

with the Duchy of Württemberg

The Duchy of Württemberg () was a duchy located in the south-western part of the Holy Roman Empire. It was a Imperial Estate, state of the Holy Roman Empire from 1495 to 1803. The dukedom's long survival for over three centuries was mainly du ...

). His mother, who was much younger than his father, tutored him diligently throughout his early years, so he easily surpassed the other children at school. During his gymnasium years, he had little trouble acquiring Latin and Greek, and was always at the head of his class in mathematics, history, and geography. According to Lee, "The history of mankind was, from the earliest period of his life, a subject of the most indefatigable application; and long lists of sovereigns, princes, and the driest chronological facts, once arranged in his memory, were never forgotten."

At the age of 10, soon after entering the gymnasium, he encountered a copy of Conrad Gessner's ''Historiae Animalium'', the work that first sparked his interest in

At the age of 10, soon after entering the gymnasium, he encountered a copy of Conrad Gessner's ''Historiae Animalium'', the work that first sparked his interest in natural history

Natural history is a domain of inquiry involving organisms, including animals, fungi, and plants, in their natural environment, leaning more towards observational than experimental methods of study. A person who studies natural history is cal ...

. He then began frequent visits to the home of a relative, where he could borrow volumes of the Comte de Buffon's massive ''Histoire Naturelle

The ''Histoire Naturelle, générale et particulière, avec la description du Cabinet du Roi'' (; ) is an encyclopaedic collection of 36 large (quarto) volumes written between 1749–1804, initially by the Georges-Louis Leclerc de Buffon, Comte ...

.'' All of these he read and reread, retaining so much of the information, that by the age of 12, "he was as familiar with quadrupeds and birds as a first-rate naturalist." He remained at the gymnasium for four years.

Cuvier spent an additional four years at the Caroline Academy in Stuttgart

Stuttgart (; ; Swabian German, Swabian: ; Alemannic German, Alemannic: ; Italian language, Italian: ; ) is the capital city, capital and List of cities in Baden-Württemberg by population, largest city of the States of Germany, German state of ...

, where he excelled in all of his coursework. Although he knew no German on his arrival, after only nine months of study, he managed to win the school prize for that language. Cuvier's German education exposed him to the work of the geologist Abraham Gottlob Werner (1750–1817), whose Neptunism and emphasis on the importance of rigorous, direct observation of three-dimensional, structural relationships of rock formations to geological understanding provided models for Cuvier's scientific theories and methods.

Upon graduation, he had no money on which to live as he awaited an appointment to an academic office. So in July 1788, he took a job at Fiquainville chateau in Normandy as tutor to the only son of the Comte d'Héricy, a Protestant noble. There, during the early 1790s, he began his comparisons of fossils with extant forms. Cuvier regularly attended meetings held at the nearby town of Valmont for the discussion of agricultural topics. There, he became acquainted with Henri Alexandre Tessier (1741–1837), who had assumed a false identity. Previously, he had been a physician and well-known agronomist, who had fled the Terror in Paris. After hearing Tessier speak on agricultural matters, Cuvier recognized him as the author of certain articles on agriculture in the '' Encyclopédie Méthodique'' and addressed him as M. Tessier.

Tessier replied in dismay, "I am known, then, and consequently lost."—"Lost!" replied M. Cuvier, "no; you are henceforth the object of our most anxious care." They soon became intimate and Tessier introduced Cuvier to his colleagues in Paris"I have just found a pearl in the dunghill of Normandy", he wrote his friend Antoine-Augustin Parmentier. As a result, Cuvier entered into correspondence with several leading naturalists of the day and was invited to Paris. Arriving in the spring of 1795, at the age of 26, he soon became the assistant of Jean-Claude Mertrud (1728–1802), who had been appointed to the chair of Animal Anatomy

Anatomy () is the branch of Morphology (biology), morphology concerned with the study of the internal structure of organisms and their parts. Anatomy is a branch of natural science that deals with the structural organization of living things ...

at the Jardin des Plantes. When Mertrud died in 1802, Cuvier replaced him in office and the Chair changed its name to Chair of Comparative Anatomy

Comparative anatomy is the study of similarities and differences in the anatomy of different species. It is closely related to evolutionary biology and phylogeny (the evolution of species).

The science began in the classical era, continuing in t ...

.

The Institut de France was founded in the same year, and he was elected a member of its Academy of Sciences. On 4 April 1796 he began to lecture at the École Centrale du Pantheon and, at the opening of the National Institute in April, he read his first paleontological paper, which subsequently was published in 1800 under the title ''Mémoires sur les espèces d'éléphants vivants et fossiles''. In this paper, he analyzed skeletal remains of Indian and African elephant

Elephants are the largest living land animals. Three living species are currently recognised: the African bush elephant ('' Loxodonta africana''), the African forest elephant (''L. cyclotis''), and the Asian elephant ('' Elephas maximus ...

s, as well as mammoth

A mammoth is any species of the extinct elephantid genus ''Mammuthus.'' They lived from the late Miocene epoch (from around 6.2 million years ago) into the Holocene until about 4,000 years ago, with mammoth species at various times inhabi ...

fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserve ...

s, and a fossil skeleton known at that time as the "Ohio animal". In his second paper in 1796, he described and analyzed a large skeleton found in Paraguay

Paraguay, officially the Republic of Paraguay, is a landlocked country in South America. It is bordered by Argentina to the Argentina–Paraguay border, south and southwest, Brazil to the Brazil–Paraguay border, east and northeast, and Boli ...

, which he would name ''Megatherium

''Megatherium'' ( ; from Greek () 'great' + () 'beast') is an extinct genus of ground sloths endemic to South America that lived from the Early Pliocene through the end of the Late Pleistocene. It is best known for the elephant-sized type spe ...

''. He concluded this skeleton represented yet another extinct animal and, by comparing its skull with living species of tree-dwelling sloths, that it was a kind of ground-dwelling giant sloth.

Together, these two 1796 papers were a seminal or landmark event, becoming a turning point in the history of paleontology, and in the development of comparative anatomy

Comparative anatomy is the study of similarities and differences in the anatomy of different species. It is closely related to evolutionary biology and phylogeny (the evolution of species).

The science began in the classical era, continuing in t ...

, as well. They also greatly enhanced Cuvier's personal reputation and they essentially ended what had been a long-running debate about the reality of extinction

Extinction is the termination of an organism by the death of its Endling, last member. A taxon may become Functional extinction, functionally extinct before the death of its last member if it loses the capacity to Reproduction, reproduce and ...

.

In 1799, he succeeded Daubenton as professor of natural history in the '' Collège de France''. In 1802, he became titular professor at the '' Jardin des Plantes''; and in the same year, he was appointed commissary of the institute to accompany the inspectors general of public instruction. In this latter capacity, he visited the south of France, but in the early part of 1803, he was chosen permanent secretary of the department of physical sciences of the Academy, and he consequently abandoned the earlier appointment and returned to Paris. In 1806, he became a foreign member of the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

, and in 1812, a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences () is one of the Swedish Royal Academies, royal academies of Sweden. Founded on 2 June 1739, it is an independent, non-governmental scientific organization that takes special responsibility for promoting nat ...

. In 1812, he became a correspondent for the Royal Institute of the Netherlands, and became a member in 1827. Cuvier was elected a Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

The American Academy of Arts and Sciences (The Academy) is one of the oldest learned societies in the United States. It was founded in 1780 during the American Revolution by John Adams, John Hancock, James Bowdoin, Andrew Oliver, and other ...

in 1822.

Cuvier then devoted himself more especially to three lines of inquiry: (i) the structure and classification of the ''

Cuvier then devoted himself more especially to three lines of inquiry: (i) the structure and classification of the ''Mollusca

Mollusca is a phylum of protostome, protostomic invertebrate animals, whose members are known as molluscs or mollusks (). Around 76,000 extant taxon, extant species of molluscs are recognized, making it the second-largest animal phylum ...

''; (ii) the comparative anatomy and systematic arrangement of the fishes; (iii) fossil mammals and reptiles and, secondarily, the osteology of living forms belonging to the same groups.

In 1812, Cuvier made what the cryptozoologist Bernard Heuvelmans called his "Rash dictum": he remarked that it was unlikely that any large animal remained undiscovered. Ten years after his death, the word "dinosaur" would be coined by Richard Owen

Sir Richard Owen (20 July 1804 – 18 December 1892) was an English biologist, comparative anatomy, comparative anatomist and paleontology, palaeontologist. Owen is generally considered to have been an outstanding naturalist with a remarkabl ...

in 1842.

During his lifetime, Cuvier served as an imperial councillor under Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte (born Napoleone di Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French general and statesman who rose to prominence during the French Revolution and led Military career ...

, president of the Council of Public Instruction and chancellor of the university under the restored Bourbons, Grand Officer of the Legion of Honour, a Peer of France, Minister of the Interior, and president of the Council of State under Louis Philippe. He was eminent in all these capacities, and yet the dignity given by such high administrative positions was as nothing compared to his leadership in natural science.

Cuvier was by birth, education, and conviction a devout Lutheran

Lutheranism is a major branch of Protestantism that emerged under the work of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German friar and Protestant Reformers, reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practices of the Catholic Church launched ...

, and remained Protestant throughout his life while regularly attending church service

A church service (or a worship service) is a formalized period of Christian communal Christian worship, worship, often held in a Church (building), church building. Most Christian denominations hold church services on the Lord's Day (offering Su ...

s. Despite this, he regarded his personal faith as a private matter; he evidently identified himself with his confessional minority group when he supervised governmental educational programs for Protestants

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

. He also was very active in founding the Parisian Biblical Society in 1818, where he later served as a vice president. From 1822 until his death in 1832, Cuvier was Grand Master of the Protestant Faculties of Theology of the French University.

Scientific ideas and their impact

Opposition to evolution

Cuvier was critical of theories of evolution, in particular those proposed by his contemporaries Lamarck and Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, which involved the gradual transmutation of one form into another. He repeatedly emphasized that his extensive experience with fossil material indicated one fossil form does not, as a rule, gradually change into a succeeding, distinct fossil form. A deep-rooted source of his opposition to the gradual transformation of species was his goal of creating an accurate taxonomy based on principles of comparative anatomy. Such a project would become impossible if species were mutable, with no clear boundaries between them. According to the University of California Museum of Paleontology, "Cuvier did not believe in organic evolution, for any change in an organism's anatomy would have rendered it unable to survive. He studied the mummified cats and ibises that Geoffroy had brought back from Napoleon's invasion of Egypt, and showed they were no different from their living counterparts; Cuvier used this to support his claim that life forms did not evolve over time." He also observed that Napoleon's expedition to Egypt had retrieved animals mummified thousands of years previously that seemed no different from their modern counterparts. "Certainly", Cuvier wrote, "one cannot detect any greater difference between these creatures and those we see, than between the human mummies and the skeletons of present-day men." Lamarck dismissed this conclusion, arguing that evolution happened much too slowly to be observed over just a few thousand years. Cuvier, however, in turn criticized how Lamarck and other naturalists conveniently introduced hundreds of thousands of years "with a stroke of a pen" to uphold their theory. Instead, he argued that one may judge what a long time would produce only by multiplying what a lesser time produces. Since a lesser time produced no organic changes, neither, he argued, would a much longer time. Moreover, his commitment to the principle of the correlation of parts caused him to doubt that any mechanism could ever gradually modify any part of an animal in isolation from all the other parts (in the way Lamarck proposed), without rendering the animal unable to survive. In his ''Éloge de M. de Lamarck'' (''Praise for M. de Lamarck''), Cuvier wrote that Lamarck's theory of evolution rested on two arbitrary suppositions; the one, that it is the seminal vapour which organizes the embryo; the other, that efforts and desires may engender organs. A system established on such foundations may amuse the imagination of a poet; a metaphysician may derive from it an entirely new series of systems; but it cannot for a moment bear the examination of anyone who has dissected a hand, a viscus, or even a feather. Instead, he said, the typical form makes an abrupt appearance in the fossil record, and persists unchanged to the time of its extinction. Cuvier attempted to explain this paleontological phenomenon he envisioned (which would be readdressed more than a century later by " punctuated equilibrium") and to harmonize it with the ''Bible''. He attributed the different time periods he was aware of as intervals between major catastrophes, the last of which is found in ''Genesis''. Cuvier's claim that new fossil forms appear abruptly in the geological record and then continue without alteration in overlying strata was used by later critics of evolution to support creationism, to whom the abruptness seemed consistent with special divine creation (although Cuvier's finding that different types made their paleontological debuts in different geological strata clearly did not). The lack of change was consistent with the supposed sacred immutability of "species", but, again, the idea of extinction, of which Cuvier was the great proponent, obviously was not. Many writers have unjustly accused Cuvier of obstinately maintaining that fossil human beings could never be found. In his ''Essay on the Theory of the Earth'', he did say, "no human bones have yet been found among fossil remains", but he made it clear exactly what he meant: "When I assert that human bones have not been hitherto found among extraneous fossils, I must be understood to speak of fossils, or petrifactions, properly so called". Petrified bones, which have had time to mineralize and turn to stone, are typically far older than bones found to that date. Cuvier's point was that all human bones found that he knew of, were of relatively recent age because they had not been petrified and had been found only in superficial strata. He was not dogmatic in this claim, however; when new evidence came to light, he included in a later edition an appendix describing a skeleton that he freely admitted was an "instance of a fossil human petrifaction". The harshness of his criticism and the strength of his reputation, however, continued to discourage naturalists from speculating about the gradual transmutation of species, untilCharles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English Natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci ...

published ''On the Origin of Species

''On the Origin of Species'' (or, more completely, ''On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life'')The book's full original title was ''On the Origin of Species by M ...

'' more than two decades after Cuvier's death.

Extinction

Early in his tenure at the National Museum in Paris, Cuvier published studies of fossil bones in which he argued that they belonged to large, extinct quadrupeds. His first two such publications were those identifying mammoth and mastodon fossils as belonging to extinct species rather than modern elephants and the study in which he identified the ''Megatherium'' as a giant, extinct species of sloth. His primary evidence for his identifications of mammoths and mastodons as separate, extinct species was the structure of their jaws and teeth. His primary evidence that the ''Megatherium'' fossil had belonged to a massive sloth came from his comparison of its skull with those of extant sloth species.

Cuvier wrote of his paleontological method that "the form of the tooth leads to the form of the condyle, that of the scapula to that of the nails, just as an equation of a curve implies all of its properties; and, just as in taking each property separately as the basis of a special equation we are able to return to the original equation and other associated properties, similarly, the nails, the scapula, the condyle, the femur, each separately reveal the tooth or each other; and by beginning from each of them the thoughtful professor of the laws of organic economy can reconstruct the entire animal."

However, Cuvier's actual method was heavily dependent on the comparison of fossil specimens with the anatomy of extant species in the necessary context of his vast knowledge of animal anatomy and access to unparalleled natural history collections in Paris. This reality, however, did not prevent the rise of a popular legend that Cuvier could reconstruct the entire bodily structures of extinct animals given only a few fragments of bone.

At the time Cuvier presented his 1796 paper on living and fossil elephants, it was still widely believed that no species of animal had ever become extinct. Authorities such as Buffon had claimed that fossils found in Europe of animals such as the woolly rhinoceros and the mammoth were remains of animals still living in the tropics (i.e.

Early in his tenure at the National Museum in Paris, Cuvier published studies of fossil bones in which he argued that they belonged to large, extinct quadrupeds. His first two such publications were those identifying mammoth and mastodon fossils as belonging to extinct species rather than modern elephants and the study in which he identified the ''Megatherium'' as a giant, extinct species of sloth. His primary evidence for his identifications of mammoths and mastodons as separate, extinct species was the structure of their jaws and teeth. His primary evidence that the ''Megatherium'' fossil had belonged to a massive sloth came from his comparison of its skull with those of extant sloth species.

Cuvier wrote of his paleontological method that "the form of the tooth leads to the form of the condyle, that of the scapula to that of the nails, just as an equation of a curve implies all of its properties; and, just as in taking each property separately as the basis of a special equation we are able to return to the original equation and other associated properties, similarly, the nails, the scapula, the condyle, the femur, each separately reveal the tooth or each other; and by beginning from each of them the thoughtful professor of the laws of organic economy can reconstruct the entire animal."

However, Cuvier's actual method was heavily dependent on the comparison of fossil specimens with the anatomy of extant species in the necessary context of his vast knowledge of animal anatomy and access to unparalleled natural history collections in Paris. This reality, however, did not prevent the rise of a popular legend that Cuvier could reconstruct the entire bodily structures of extinct animals given only a few fragments of bone.

At the time Cuvier presented his 1796 paper on living and fossil elephants, it was still widely believed that no species of animal had ever become extinct. Authorities such as Buffon had claimed that fossils found in Europe of animals such as the woolly rhinoceros and the mammoth were remains of animals still living in the tropics (i.e. rhinoceros

A rhinoceros ( ; ; ; : rhinoceros or rhinoceroses), commonly abbreviated to rhino, is a member of any of the five extant taxon, extant species (or numerous extinct species) of odd-toed ungulates (perissodactyls) in the family (biology), famil ...

and elephant

Elephants are the largest living land animals. Three living species are currently recognised: the African bush elephant ('' Loxodonta africana''), the African forest elephant (''L. cyclotis''), and the Asian elephant ('' Elephas maximus ...

s), which had shifted out of Europe and Asia as the earth became cooler.

Thereafter, Cuvier performed a pioneering research study on some elephant fossils excavated around Paris. The bones he studied, however, were remarkably different from the bones of elephants currently thriving in India and Africa. This discovery led Cuvier to denounce the idea that fossils came from those that are currently living. The idea that these bones belonged to elephants living – but hiding – somewhere on Earth seemed ridiculous to Cuvier, because it would be nearly impossible to miss them due to their enormous size. The ''Megatherium'' provided another compelling data point for this argument. Ultimately, his repeated identification of fossils as belonging to species unknown to man, combined with mineralogical evidence from his stratigraphical studies in Paris, drove Cuvier to the proposition that the abrupt changes the Earth underwent over a long period of time caused some species to go extinct.

Cuvier's theory on extinction has met opposition from other notable natural scientists like Darwin and Charles Lyell. Unlike Cuvier, they didn't believe that extinction was a sudden process; they believed that like the Earth, animals collectively undergo gradual change as a species. This differed widely from Cuvier's theory, which seemed to propose that animal extinction was catastrophic.

However, Cuvier's theory of extinction is still justified in the case of mass extinctions that occurred in the last 600 million years, when approximately half of all living species went completely extinct within a short geological span of two million years, due in part by volcanic eruptions, asteroids, and rapid fluctuations in sea level. At this time, new species rose and others fell, precipitating the arrival of human beings.

Cuvier's early work demonstrated conclusively that extinction was indeed a credible natural global process. Cuvier's thinking on extinctions was influenced by his extensive readings in Greek and Latin literature; he gathered every ancient report known in his day relating to discoveries of petrified bones of remarkable size in the Mediterranean region.

Influence on Cuvier's theory of extinction was his collection of specimens from the New World, many of them obtained from Native Americans. He also maintained an archive of Native American observations, legends, and interpretations of immense fossilized skeletal remains, sent to him by informants and friends in the Americas. He was impressed that most of the Native American accounts identified the enormous bones, teeth, and tusks as animals of the deep past that had been destroyed by catastrophe.

Catastrophism

Cuvier came to believe that most, if not all, the animal fossils he examined were remains of species that had become extinct. Near the end of his 1796 paper on living and fossil elephants, he said:

:''All of these facts, consistent among themselves, and not opposed by any report, seem to me to prove the existence of a world previous to ours, destroyed by some kind of catastrophe.''

Contrary to many natural scientists' beliefs at the time, Cuvier believed that animal extinction was not a product of

Cuvier came to believe that most, if not all, the animal fossils he examined were remains of species that had become extinct. Near the end of his 1796 paper on living and fossil elephants, he said:

:''All of these facts, consistent among themselves, and not opposed by any report, seem to me to prove the existence of a world previous to ours, destroyed by some kind of catastrophe.''

Contrary to many natural scientists' beliefs at the time, Cuvier believed that animal extinction was not a product of anthropogenic

Anthropogenic ("human" + "generating") is an adjective that may refer to:

* Anthropogeny, the study of the origins of humanity

Anthropogenic may also refer to things that have been generated by humans, as follows:

* Human impact on the enviro ...

causes. Instead, he proposed that humans were around long enough to indirectly maintain the fossilized records of ancient Earth. He also attempted to verify the water catastrophe by analyzing records of various cultural backgrounds. Though he found many accounts of the water catastrophe unclear, he did believe that such an event occurred at the brink of human history nonetheless.

This led Cuvier to become an active proponent of the geological school of thought called catastrophism, which maintained that many of the geological features of the earth and the history of life could be explained by catastrophic events that had caused the extinction of many species of animals. Over the course of his career, Cuvier came to believe there had not been a single catastrophe, but several, resulting in a succession of different faunas. He wrote about these ideas many times, in particular, he discussed them in great detail in the preliminary discourse (an introduction) to a collection of his papers, ''Recherches sur les ossements fossiles de quadrupèdes'' (''Researches on quadruped fossil bones''), on quadruped

Quadrupedalism is a form of locomotion in which animals have four legs that are used to bear weight and move around. An animal or machine that usually maintains a four-legged posture and moves using all four legs is said to be a quadruped (fr ...

fossils published in 1812.

Cuvier's own explanation for such a catastrophic event is derived from two different sources, including those from Jean-André Deluc and Déodat de Dolomieu. The former proposed that the continents existing ten millennia ago collapsed, allowing the ocean floors to rise higher than the continental plates and become the continents that now exist today. The latter proposed that a massive tsunami

A tsunami ( ; from , ) is a series of waves in a water body caused by the displacement of a large volume of water, generally in an ocean or a large lake. Earthquakes, volcanic eruptions and underwater explosions (including detonations, ...

hit the globe, leading to mass extinction. Whatever the case was, he believed that the deluge happened quite recently in human history. In fact, he believed that Earth's existence was limited and not as extended as many natural scientists, like Lamarck

Jean-Baptiste Pierre Antoine de Monet, chevalier de Lamarck (1 August 1744 – 18 December 1829), often known simply as Lamarck (; ), was a French naturalist, biologist, academic, and soldier. He was an early proponent of the idea that biolo ...

, believed it to be.

Much of the evidence he used to support his catastrophist theories has been taken from his fossil records. He strongly suggested that the fossils he found were evidence of the world's first reptiles, followed chronologically by mammals and humans. Cuvier didn't wish to delve much into the causation of all the extinction and introduction of new animal species but rather focused on the sequential aspects of animal history on Earth. In a way, his chronological dating of Earth's history somewhat reflected Lamarck's transformationist theories.

Cuvier also worked alongside Alexandre Brongniart in analyzing the Parisian rock cycle. Using stratigraphical methods, they were both able to extrapolate key information regarding Earth history from studying these rocks. These rocks contained remnants of molluscs, bones of mammals, and shells. From these findings, Cuvier and Brongniart concluded that many environmental changes occurred in quick catastrophes, though Earth itself was often placid for extended periods of time in between sudden disturbances.

The 'Preliminary Discourse' became very well known and, unauthorized translations were made into English, German, and Italian (and in the case of those in English, not entirely accurately). In 1826, Cuvier published a revised version under the name, ''Discours sur les révolutions de la surface du globe'' (''Discourse on the upheavals of the surface of the globe'').

After Cuvier's death, the catastrophic school of geological thought lost ground to uniformitarianism, as championed by Charles Lyell and others, which claimed that the geological features of the earth were best explained by currently observable forces, such as erosion and volcanism, acting gradually over an extended period of time. The increasing interest in the topic of mass extinction starting in the late twentieth century, however, has led to a resurgence of interest among historians of science and other scholars in this aspect of Cuvier's work.

Stratigraphy

Cuvier collaborated for several years with Alexandre Brongniart, an instructor at the Paris mining school, to produce a monograph on the geology of the region around Paris. They published a preliminary version in 1808 and the final version was published in 1811. In this monograph, they identified characteristic fossils of different rock layers that they used to analyze the geological column, the ordered layers of sedimentary rock, of the Paris basin. They concluded that the layers had been laid down over an extended period during which there clearly had been faunal succession and that the area had been submerged under sea water at times and at other times under fresh water. Along with William Smith's work during the same period on a geological map of England, which also used characteristic fossils and the principle of faunal succession to correlate layers of sedimentary rock, the monograph helped establish the scientific discipline ofstratigraphy

Stratigraphy is a branch of geology concerned with the study of rock layers (strata) and layering (stratification). It is primarily used in the study of sedimentary and layered volcanic rocks.

Stratigraphy has three related subfields: lithost ...

. It was a major development in the history of paleontology and the history of geology

The history of geology is concerned with the development of the natural science of geology. Geology is the scientific study of the origin, history, and structure of the Earth.

Antiquity

In the year 540 BC, Xenophanes described fossil fish a ...

.

Age of reptiles

In 1800 and working only from a drawing, Cuvier was the first to correctly identify in print, a fossil found in Bavaria as a small flying reptile, which he named the ''Ptero-Dactyle'' in 1809, (later Latinized as '' Pterodactylus antiquus'')—the first known member of the diverse order of pterosaurs. In 1808 Cuvier identified a fossil found inMaastricht

Maastricht ( , , ; ; ; ) is a city and a Municipalities of the Netherlands, municipality in the southeastern Netherlands. It is the capital city, capital and largest city of the province of Limburg (Netherlands), Limburg. Maastricht is loca ...

as a giant marine lizard, the first known mosasaur

Mosasaurs (from Latin ''Mosa'' meaning the 'Meuse', and Ancient Greek, Greek ' meaning 'lizard') are an extinct group of large aquatic reptiles within the family Mosasauridae that lived during the Late Cretaceous. Their first fossil remains wer ...

.

Cuvier speculated correctly that there had been a time when reptile

Reptiles, as commonly defined, are a group of tetrapods with an ectothermic metabolism and Amniotic egg, amniotic development. Living traditional reptiles comprise four Order (biology), orders: Testudines, Crocodilia, Squamata, and Rhynchocepha ...

s rather than mammal

A mammal () is a vertebrate animal of the Class (biology), class Mammalia (). Mammals are characterised by the presence of milk-producing mammary glands for feeding their young, a broad neocortex region of the brain, fur or hair, and three ...

s had been the dominant fauna. This speculation was confirmed over the two decades following his death by a series of spectacular finds, mostly by English geologists and fossil collectors such as Mary Anning, William Conybeare, William Buckland, and Gideon Mantell, who found and described the first ichthyosaurs, plesiosaur

The Plesiosauria or plesiosaurs are an Order (biology), order or clade of extinct Mesozoic marine reptiles, belonging to the Sauropterygia.

Plesiosaurs first appeared in the latest Triassic Period (geology), Period, possibly in the Rhaetian st ...

s, and dinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic Geological period, period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the #Evolutio ...

s.

Principle of the correlation of parts

In a 1798 paper on the fossil remains of an animal found in some plaster quarries near Paris, Cuvier states what is known as the principle of the correlation of parts. He writes: :''If an animal's teeth are such as they must be, in order for it to nourish itself with flesh, we can be sure without further examination that the whole system of its digestive organs is appropriate for that kind of food, and that its whole skeleton and locomotive organs, and even its sense organs, are arranged in such a way as to make it skilful at pursuing and catching its prey. For these relations are the necessary conditions of existence of the animal; if things were not so, it would not be able to subsist.'' This idea is referred to as Cuvier's principle of correlation of parts, which states that all organs in an animal's body are deeply interdependent. Species' existence relies on the way in which these organs interact. For example, a species whose digestive tract is best suited to digesting flesh but whose body is best suited to foraging for plants cannot survive. Thus in all species, the functional significance of each body part must be correlated to the others, or else the species cannot sustain itself.Applications

Cuvier believed that the power of his principle came in part from its ability to aid in the reconstruction of fossils. In most cases, fossils of quadrupeds were not found as complete, assembled skeletons, but rather as scattered pieces that needed to be put together by anatomists. To make matters worse, deposits often contained the fossilized remains of several species of animals mixed together. Anatomists reassembling these skeletons ran the risk of combining remains of different species, producing imaginary composite species. However, by examining the functional purpose of each bone and applying the principle of correlation of parts, Cuvier believed that this problem could be avoided. This principle's ability to aid in the reconstruction of fossils was also helpful to Cuvier's work in providing evidence in favour of extinction. The strongest evidence Cuvier could provide in favour of extinction would be to prove that the fossilized remains of an animal belonged to a species that no longer existed. By applying Cuvier's principle of correlation of parts, it would be easier to verify that a fossilized skeleton had been authentically reconstructed, thus validating any observations drawn from comparing it to skeletons of existing species. In addition to helping anatomists reconstruct fossilized remains, Cuvier believed that his principle also held enormous predictive power. For example, when he discovered a fossil that resembled a marsupial in the gypsum quarries of Montmartre, he correctly predicted that the fossil would contain bones commonly found in marsupials in its pelvis as well.Impact

Cuvier hoped that his principles of anatomy would provide the law-based framework that would elevate natural history to the truly scientific level occupied by physics and chemistry thanks to the laws established by Isaac Newton (1643 – 1727) and Antoine Lavoisier (1743 – 1794), respectively. He expressed confidence in the introduction to '' Le Règne Animal'' that someday anatomy would be expressed as laws as simple, mathematical, and predictive as Newton's laws of physics, and he viewed his principle as an important step in that direction. To him, the predictive capabilities of his principles demonstrated in his prediction of the existence of marsupial pelvic bones in the gypsum quarries of Montmartre demonstrated that these goals were not only in reach, but imminent. The principle of correlation of parts was also Cuvier's way of understanding function in a non-evolutionary context, without invoking a divine creator. In the same 1798 paper on the fossil remains of an animal found in plaster quarries near Paris, Cuvier emphasizes the predictive power of his principle, writing,Today comparative anatomy has reached such a point of perfection that, after inspecting a single bone, one can often determine the class, and sometimes even the genus of the animal to which it belonged, above all if that bone belonged to the head or the limbs ... This is because the number, direction, and shape of the bones that compose each part of an animal's body are always in a necessary relation to all the other parts, in such a way that—up to a point—one can infer the whole from any one of them and vice versa.Though Cuvier believed that his principle's major contribution was that it was a rational, mathematical way to reconstruct fossils and make predictions, in reality, it was difficult for Cuvier to use his principle. The functional significance of many body parts was still unknown at the time, and so relating those body parts to other body parts using Cuvier's principle was impossible. Though Cuvier was able to make accurate predictions about fossil finds, in practice, the accuracy of his predictions came not from application of his principle, but rather from his vast knowledge of comparative anatomy. However, despite Cuvier's exaggerations of the power of his principle, the basic concept is central to comparative anatomy and paleontology.

Scientific work

Comparative anatomy and classification

At the Paris Museum, Cuvier furthered his studies on the anatomical classification of animals. He believed that classification should be based on how organs collectively function, a concept he called functional integration. Cuvier reinforced the idea of subordinating less vital body parts to more critical organ systems as part of anatomical classification. He included these ideas in his 1817 book, '' The Animal Kingdom''. In his anatomical studies, Cuvier believed function played a bigger role than form in the field of taxonomy. His scientific beliefs rested in the idea of the principles of the correlation of parts and of the conditions of existence. The former principle accounts for the connection between organ function and its practical use for an organism to survive. The latter principle emphasizes the animal's physiological function in relation to its surrounding environment. These findings were published in his scientific readings, including ''Leçons d'anatomie comparée'' (''Lessons on Comparative Anatomy'') between 1800 and 1805, and ''The Animal Kingdom'' in 1817. Ultimately, Cuvier developed four embranchements, or branches, through which he classified animals based on his taxonomical and anatomical studies. He later performed groundbreaking work in classifying animals in vertebrate and invertebrate groups by subdividing each category. For instance, he proposed that the invertebrates could be segmented into three individual categories, including ''Mollusca'', ''Radiata'', and ''Articulata''. He also articulated that species cannot move across these categories, a theory called transmutation. He reasoned that organisms cannot acquire or change their physical traits over time and still retain optimal survival. As a result, he often conflicted with Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire and Jean-Baptiste Lamarck's theories of transmutation. In 1798, Cuvier published his first independent work, the ''Tableau élémentaire de l'histoire naturelle des animaux'', which was an abridgement of his course of lectures at the École du Pantheon and may be regarded as the foundation and first statement of his natural classification of the animal kingdom.Mollusks

Cuvier categorized snails, cockles, and cuttlefish into one category he called molluscs (''Mollusca

Mollusca is a phylum of protostome, protostomic invertebrate animals, whose members are known as molluscs or mollusks (). Around 76,000 extant taxon, extant species of molluscs are recognized, making it the second-largest animal phylum ...

''), an embranchment. Though he noted how all three of these animals were outwardly different in terms of shell shape and diet, he saw a noticeable pattern pertaining to their overall physical appearance.

Cuvier began his intensive studies of molluscs during his time in Normandy

Normandy (; or ) is a geographical and cultural region in northwestern Europe, roughly coextensive with the historical Duchy of Normandy.

Normandy comprises Normandy (administrative region), mainland Normandy (a part of France) and insular N ...

– the first time he had ever seen the sea – and his papers on the so-called ''Mollusca'' began appearing as early as 1792. However, most of his memoirs on this branch were published in the ''Annales du museum'' between 1802 and 1815; they were subsequently collected as ''Mémoires pour servir à l'histoire et à l'anatomie des mollusques'', published in one volume at Paris in 1817.

Fish

Cuvier's researches onfish

A fish (: fish or fishes) is an aquatic animal, aquatic, Anamniotes, anamniotic, gill-bearing vertebrate animal with swimming fish fin, fins and craniate, a hard skull, but lacking limb (anatomy), limbs with digit (anatomy), digits. Fish can ...

, begun in 1801, finally culminated in the publication of the ''Histoire naturelle des poissons'', which contained descriptions of 5,000 species of fishes, and was a joint production with Achille Valenciennes

Achille Valenciennes (9 August 1794 – 13 April 1865) was a French zoology, zoologist.

Valenciennes was born in Paris, and studied under Georges Cuvier. His study of parasitic worms in humans made an important contribution to the study of parasi ...

. Cuvier's work on this project extended over the years 1828–1831.

Palaeontology and osteology

In palaeontology, Cuvier published a long list of memoirs, partly relating to the bones of extinct animals, and partly detailing the results of observations on the skeletons of living animals, specially examined with a view toward throwing light upon the structure and affinities of the fossil forms. Among living forms he published papers relating to the osteology of the ''Rhinoceros

A rhinoceros ( ; ; ; : rhinoceros or rhinoceroses), commonly abbreviated to rhino, is a member of any of the five extant taxon, extant species (or numerous extinct species) of odd-toed ungulates (perissodactyls) in the family (biology), famil ...

indicus'', the tapir

Tapirs ( ) are large, herbivorous mammals belonging to the family Tapiridae. They are similar in shape to a Suidae, pig, with a short, prehensile nose trunk (proboscis). Tapirs inhabit jungle and forest regions of South America, South and Centr ...

, '' Hyrax capensis'', the hippopotamus, the sloth

Sloths are a Neotropical realm, Neotropical group of xenarthran mammals constituting the suborder Folivora, including the extant Arboreal locomotion, arboreal tree sloths and extinct terrestrial ground sloths. Noted for their slowness of move ...

s, the manatee

Manatees (, family (biology), family Trichechidae, genus ''Trichechus'') are large, fully aquatic, mostly herbivory, herbivorous marine mammals sometimes known as sea cows. There are three accepted living species of Trichechidae, representing t ...

, etc.

He produced an even larger body of work on fossils, dealing with the extinct mammals of the Eocene

The Eocene ( ) is a geological epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 56 to 33.9 million years ago (Ma). It is the second epoch of the Paleogene Period (geology), Period in the modern Cenozoic Era (geology), Era. The name ''Eocene'' comes ...

beds of Montmartre

Montmartre ( , , ) is a large hill in Paris's northern 18th arrondissement of Paris, 18th arrondissement. It is high and gives its name to the surrounding district, part of the Rive Droite, Right Bank. Montmartre is primarily known for its a ...

and other localities near Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

, such as the Buttes Chaumont, the fossil species of hippopotamus, '' Palaeotherium'', '' Anoplotherium'', a marsupial

Marsupials are a diverse group of mammals belonging to the infraclass Marsupialia. They are natively found in Australasia, Wallacea, and the Americas. One of marsupials' unique features is their reproductive strategy: the young are born in a r ...

(which he called ''Didelphys gypsorum''), the '' Megalonyx'', the ''Megatherium

''Megatherium'' ( ; from Greek () 'great' + () 'beast') is an extinct genus of ground sloths endemic to South America that lived from the Early Pliocene through the end of the Late Pleistocene. It is best known for the elephant-sized type spe ...

'', the cave-hyena, the pterodactyl, the extinct species of rhinoceros

A rhinoceros ( ; ; ; : rhinoceros or rhinoceroses), commonly abbreviated to rhino, is a member of any of the five extant taxon, extant species (or numerous extinct species) of odd-toed ungulates (perissodactyls) in the family (biology), famil ...

, the cave bear

The cave bear (''Ursus spelaeus'') is a prehistoric species of bear that lived in Europe and Asia during the Pleistocene and became extinct about 24,000 years ago during the Last Glacial Maximum.

Both the word ''cave'' and the scientific name '' ...

, the mastodon

A mastodon, from Ancient Greek μαστός (''mastós''), meaning "breast", and ὀδούς (''odoús'') "tooth", is a member of the genus ''Mammut'' (German for 'mammoth'), which was endemic to North America and lived from the late Miocene to ...

, the extinct species of elephant

Elephants are the largest living land animals. Three living species are currently recognised: the African bush elephant ('' Loxodonta africana''), the African forest elephant (''L. cyclotis''), and the Asian elephant ('' Elephas maximus ...

, fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserve ...

species of manatee and seals, fossil forms of crocodilians

Crocodilia () is an order of semiaquatic, predatory reptiles that are known as crocodilians. They first appeared during the Late Cretaceous and are the closest living relatives of birds. Crocodilians are a type of crocodylomorph pseudosuchi ...

, chelonians, fish, birds, etc. If his identification of fossil animals was dependent upon comparison with the osteology of extant animals whose anatomy was poorly known, Cuvier would often publish a thorough documentation of the relevant extant species' anatomy before publishing his analyses of the fossil specimens. The department of palaeontology dealing with the Mammal

A mammal () is a vertebrate animal of the Class (biology), class Mammalia (). Mammals are characterised by the presence of milk-producing mammary glands for feeding their young, a broad neocortex region of the brain, fur or hair, and three ...

ia may be said to have been essentially created and established by Cuvier.

The results of Cuvier's principal palaeontological and geological investigations ultimately were given to the world in the form of two separate works: ''Recherches sur les ossemens fossiles de quadrupèdes'' (Paris, 1812; later editions in 1821 and 1825); and ''Discours sur les revolutions de la surface du globe'' (Paris, 1825). In this latter work he expounded a scientific theory of Catastrophism.

''The Animal Kingdom'' (''Le Règne Animal'')

Cuvier's most admired work was his '' Le Règne Animal''. It appeared in four octavo volumes in 1817; a second edition in five volumes was brought out in 1829–1830. In this classic work, Cuvier presented the results of his life's research into the structure of living and fossil animals. With the exception of the section on

Cuvier's most admired work was his '' Le Règne Animal''. It appeared in four octavo volumes in 1817; a second edition in five volumes was brought out in 1829–1830. In this classic work, Cuvier presented the results of his life's research into the structure of living and fossil animals. With the exception of the section on insect

Insects (from Latin ') are Hexapoda, hexapod invertebrates of the class (biology), class Insecta. They are the largest group within the arthropod phylum. Insects have a chitinous exoskeleton, a three-part body (Insect morphology#Head, head, ...

s, in which he was assisted by his friend Latreille, the whole of the work was his own. It was translated into English many times, often with substantial notes and supplementary material updating the book in accordance with the expansion of knowledge.

Racial studies

Cuvier was aProtestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

and a believer in monogenism

Monogenism or sometimes monogenesis is the theory of human origins which posits a common descent for all humans. The negation of monogenism is polygenism. This issue was hotly debated in the Western world in the nineteenth century, as the assum ...

, who held that all men descended from the biblical Adam, although his position usually was confused as polygenist. Some writers who have studied his racial work have dubbed his position as "quasi-polygenist", and most of his racial studies have influenced scientific racism

Scientific racism, sometimes termed biological racism, is the pseudoscience, pseudoscientific belief that the Human, human species is divided into biologically distinct taxa called "race (human categorization), races", and that empirical evi ...

. Cuvier believed there were three distinct races: the Caucasian (white), Mongolian (yellow), and the Ethiopia

Ethiopia, officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country located in the Horn of Africa region of East Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the north, Djibouti to the northeast, Somalia to the east, Ken ...

n (black). Cuvier claimed that Adam and Eve

Adam and Eve, according to the creation myth of the Abrahamic religions, were the first man and woman. They are central to the belief that humanity is in essence a single family, with everyone descended from a single pair of original ancestors. ...

were Caucasian, the original race of mankind. The other two races originated from survivors escaping in different directions after a major catastrophe hit the earth 5,000 years ago, with those survivors then living in complete isolation from each other.

Cuvier categorized these divisions he identified into races according to his perception of the beauty or ugliness of their skulls and the quality of their civilizations. Cuvier's racial studies held the supposed features of polygenism, namely fixity of species; limits on environmental influence; unchanging underlying type; anatomical and cranial measurement differences in races; and physical and mental differences between distinct races.

Sarah Baartman

Alongside other French naturalists, Cuvier subjected Sarah Baartman, a South African Khokhoi woman exhibited in Europeanfreak show

A freak show is an exhibition of biological rarities, referred to in popular culture as "Freak, freaks of nature". Typical features would be physically unusual Human#Anatomy and physiology, humans, such as those uncommonly large or small, t ...

s as the "Hottentot Venus", to examinations. At the time that Cuvier interacted with Baartman, Baartman's "existence was really quite miserable and extraordinarily poor. Sara was literally ictreated like an animal." In 1815, while Baartman was very ill, Cuvier commissioned a nude painting of her. She died shortly afterward, aged 26.

Following Baartman's death, Cuvier sought out and received permission to dissect her body, focusing on her genitalia, buttocks and skull shape. In his examination, Cuvier concluded that many of Baartman's features more closely resembled the anatomy of a monkey than a human. Her remains were displayed in the Musée de l’Homme in Paris until 1970, then were put into storage. Her remains were returned to South Africa in 2002.

Taxa described by him

*See :Taxa named by Georges CuvierOfficial and public work

Apart from his own original investigations in zoology and

Apart from his own original investigations in zoology and paleontology

Paleontology, also spelled as palaeontology or palæontology, is the scientific study of the life of the past, mainly but not exclusively through the study of fossils. Paleontologists use fossils as a means to classify organisms, measure ge ...

Cuvier carried out a vast amount of work as perpetual secretary of the National Institute, and as an official connected with public education generally; and much of this work appeared ultimately in a published form. Thus, in 1808 he was placed by Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte (born Napoleone di Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French general and statesman who rose to prominence during the French Revolution and led Military career ...

upon the council of the Imperial University, and in this capacity he presided (in the years 1809, 1811, and 1813) over commissions charged to examine the state of the higher educational establishments in the districts beyond the Alps

The Alps () are some of the highest and most extensive mountain ranges in Europe, stretching approximately across eight Alpine countries (from west to east): Monaco, France, Switzerland, Italy, Liechtenstein, Germany, Austria and Slovenia.

...

and the Rhine

The Rhine ( ) is one of the List of rivers of Europe, major rivers in Europe. The river begins in the Swiss canton of Graubünden in the southeastern Swiss Alps. It forms part of the Swiss-Liechtenstein border, then part of the Austria–Swit ...

that had been annexed to France, and to report upon the means by which these could be affiliated with the central university. He published three separate reports on this subject.

In his capacity, again, of perpetual secretary of the Institute, he not only prepared a number of '' éloges historiques'' on deceased members of the Academy of Sciences, but was also the author of a number of reports on the history of the physical and natural sciences, the most important of these being the ''Rapport historique sur le progrès des sciences physiques depuis 1789'', published in 1810.

Prior to the fall of Napoleon (1814) he had been admitted to the council of state, and his position remained unaffected by the restoration of the Bourbons. He was elected chancellor of the university, in which capacity he acted as interim president of the council of public instruction, while he also, as a Lutheran

Lutheranism is a major branch of Protestantism that emerged under the work of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German friar and Protestant Reformers, reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practices of the Catholic Church launched ...

, superintended the faculty of Protestant theology. In 1819 he was appointed president of the committee of the interior, an office he retained until his death.

In 1826 he was made grand officer of the Legion of Honour