George Simpson (HBC administrator) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sir George Simpson ( – 7 September 1860) was a Scottish explorer and colonial governor of the

This was at the time of conflict between the HBC and the

This was at the time of conflict between the HBC and the

A street was named in his honor, called Simpson Street, next to Parc Percy-Walters, McGregor Street, and :fr:Maison John-Wilson-McConnell, Maison John-Wilson-McConnell. The park was previously occupied by one of his houses, and was part of his 15 acre estate on Mount Royal. It was then occupied by Rosemount House, which was built on the land of Governor Simpson and was the home of Sir John Rose, 1st Baronet, and later William Watson Ogilvie. Galt House was also built on Simpson Street by Canadian Founding Father Sir Alexander Tilloch Galt. The entrance of Simpson Street is now occupied by Sir George Simpson (condominiums), Sir George Simpson Tower.

Both Simpson Street and Prince of Wales Terrace were in the Golden Square Mile, a neighbourhood of Downtown Montreal where nearly 3/4 of all the wealth in Canada was held by its inhabitants. During that era, most Canadian enterprises were either owned or controlled by approximately fifty men. As the most important man in the

A street was named in his honor, called Simpson Street, next to Parc Percy-Walters, McGregor Street, and :fr:Maison John-Wilson-McConnell, Maison John-Wilson-McConnell. The park was previously occupied by one of his houses, and was part of his 15 acre estate on Mount Royal. It was then occupied by Rosemount House, which was built on the land of Governor Simpson and was the home of Sir John Rose, 1st Baronet, and later William Watson Ogilvie. Galt House was also built on Simpson Street by Canadian Founding Father Sir Alexander Tilloch Galt. The entrance of Simpson Street is now occupied by Sir George Simpson (condominiums), Sir George Simpson Tower.

Both Simpson Street and Prince of Wales Terrace were in the Golden Square Mile, a neighbourhood of Downtown Montreal where nearly 3/4 of all the wealth in Canada was held by its inhabitants. During that era, most Canadian enterprises were either owned or controlled by approximately fifty men. As the most important man in the

Simpson sired at least eleven children by at least seven women, only one of whom was his wife.

During his years in London, he fathered two daughters, born to two separate women. Maria-Louisa, born 1815 to a mother named Maria, and Isabella, born 1817 to an unknown mother. Once Simpson left for Rupert's Land, both daughters were sent to Scotland to be cared for by his relatives.

Sometime during his first year in Rupert's Land, in about 1821, he met and began a relationship with Elizabeth "Betsey" Sinclair, a Métis washerwoman, who he likely met at Fort Wedderburn. He fathered one child with her, a daughter named Maria, who died at age 16 when she drowned while travelling to the Columbia District. Simpson ended their relationship when he began his 1822 trip westward, regarding her as an "unnecessary & expensive appendage" who was of little use to him while he was away travelling.

James Keith Simpson (1823–1901) is poorly documented. Ann Simpson, born in Montreal in 1828, is known only from her baptismal record. Simpson fathered two sons, George Stewart (1827) and John Mackenzie (1829), with Margaret (Marguerite) Taylor. George married Isabella Yale (1840–1927), daughter of fur trader James Murray Yale, of the Yale (surname), Yale family. George was also the brother-in-law of Eliza Yale, wife of Capt. Henry Newsham Peers, grandson of Count Julianus Petrus de Linnée.

Soon after the birth of John Mackenzie, Simpson left Margaret to cousin marriage, marry his cousin. Simpson shocked his peers by neglecting to notify Margaret of his marriage or make any arrangements for the future of his two sons.

Simpson sired at least eleven children by at least seven women, only one of whom was his wife.

During his years in London, he fathered two daughters, born to two separate women. Maria-Louisa, born 1815 to a mother named Maria, and Isabella, born 1817 to an unknown mother. Once Simpson left for Rupert's Land, both daughters were sent to Scotland to be cared for by his relatives.

Sometime during his first year in Rupert's Land, in about 1821, he met and began a relationship with Elizabeth "Betsey" Sinclair, a Métis washerwoman, who he likely met at Fort Wedderburn. He fathered one child with her, a daughter named Maria, who died at age 16 when she drowned while travelling to the Columbia District. Simpson ended their relationship when he began his 1822 trip westward, regarding her as an "unnecessary & expensive appendage" who was of little use to him while he was away travelling.

James Keith Simpson (1823–1901) is poorly documented. Ann Simpson, born in Montreal in 1828, is known only from her baptismal record. Simpson fathered two sons, George Stewart (1827) and John Mackenzie (1829), with Margaret (Marguerite) Taylor. George married Isabella Yale (1840–1927), daughter of fur trader James Murray Yale, of the Yale (surname), Yale family. George was also the brother-in-law of Eliza Yale, wife of Capt. Henry Newsham Peers, grandson of Count Julianus Petrus de Linnée.

Soon after the birth of John Mackenzie, Simpson left Margaret to cousin marriage, marry his cousin. Simpson shocked his peers by neglecting to notify Margaret of his marriage or make any arrangements for the future of his two sons.

Hudson's Bay Company

The Hudson's Bay Company (HBC), originally the Governor and Company of Adventurers of England Trading Into Hudson’s Bay, is a Canadian holding company of department stores, and the oldest corporation in North America. It was the owner of the ...

during the period of its greatest power. From 1820 to 1860, he was in practice, if not in law, the British viceroy

A viceroy () is an official who reigns over a polity in the name of and as the representative of the monarch of the territory.

The term derives from the Latin prefix ''vice-'', meaning "in the place of" and the Anglo-Norman ''roy'' (Old Frenc ...

for the whole of Rupert's Land

Rupert's Land (), or Prince Rupert's Land (), was a territory in British North America which comprised the Hudson Bay drainage basin. The right to "sole trade and commerce" over Rupert's Land was granted to Hudson's Bay Company (HBC), based a ...

, an enormous territory of 3.9 millions square kilometres corresponding to nearly forty per cent of modern-day Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its Provinces and territories of Canada, ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, making it the world's List of coun ...

.

His efficient administration of the west was a precondition for the confederation of western and eastern Canada, which later created the ''Dominion of Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its Provinces and territories of Canada, ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, making it the world's List of coun ...

''. He was noted for his grasp of administrative detail and his physical stamina in traveling through the wilderness. Excepting voyageurs

Voyageurs (; ) were 18th- and 19th-century French and later French Canadians and others who transported furs by canoe at the peak of the North American fur trade. The emblematic meaning of the term applies to places (New France, including the ...

and their Siberian equivalents, few men have spent as much time travelling in the wilderness.

Simpson was also the first person known to have "circumnavigated" the world by land, and became the most powerful man of the North American fur trade

The North American fur trade is the (typically) historical Fur trade, commercial trade of furs and other goods in North America, beginning in the eastern provinces of French Canada and the northeastern Thirteen Colonies, American colonies (soon- ...

during his lifetime.

Early life

Born atDingwall

Dingwall (, ) is a town and a royal burgh in the Highland (council area), Highland council area of Scotland. It has a population of 5,491. It was an east-coast harbour that now lies inland.

Dingwall Castle was once the biggest castle north ...

, Ross-Shire

Ross-shire (; ), or the County of Ross, was a county in the Scottish Highlands. It bordered Sutherland to the north and Inverness-shire to the south, as well as having a complex border with Cromartyshire, a county consisting of numerous enc ...

, Scotland, as the illegitimate son of George Simpson, Writer to the Signet

The Society of Writers to His Majesty's Signet is a private society of Scottish solicitors, dating back to 1594 and part of the College of Justice. Writers to the Signet originally had special privileges in relation to the drawing up of documen ...

, he was raised by two aunts and his paternal grandmother, Isobel Simpson (1731–1821), daughter of George Mackenzie, 2nd Laird

Laird () is a Scottish word for minor lord (or landlord) and is a designation that applies to an owner of a large, long-established Scotland, Scottish estate. In the traditional Scottish order of precedence, a laird ranked below a Baronage of ...

of Gruinard

Gruinard Island ( ;

) is a small, oval-shaped Scottish island approximately long by wide, located in Gruinard Bay, about halfway between Gairloch and Ullapool. At its closest point to the mainland, it is about offshore. In 1942, the island be ...

—grandson of George Mackenzie, 2nd Earl of Seaforth—and Elizabeth, daughter of Duncan Forbes, Lord Culloden. Simpson's father was a first cousin of Sir Alexander Mackenzie's father-in-law.

In 1808, he was sent to London to work in the sugar brokerage business run by his uncle, Geddes Mackenzie Simpson (1775–1848). When his uncle's firm merged with that of Andrew Colvile-Wedderburn in 1812, Simpson came into contact with the Hudson's Bay Company

The Hudson's Bay Company (HBC), originally the Governor and Company of Adventurers of England Trading Into Hudson’s Bay, is a Canadian holding company of department stores, and the oldest corporation in North America. It was the owner of the ...

, as Colvile was a company director and brother-in-law of Thomas Douglas, 5th Earl of Selkirk

Thomas Douglas, 5th Earl of Selkirk FRS FRSE (20 June 1771 – 8 April 1820) was a Scottish landowner and philanthropist. He was noteworthy as a Scottish philanthropist who sponsored immigrant settlements in Canada at the Red River Colony.

E ...

.

Career (1820–42)

This was at the time of conflict between the HBC and the

This was at the time of conflict between the HBC and the North West Company

The North West Company was a Fur trade in Canada, Canadian fur trading business headquartered in Montreal from 1779 to 1821. It competed with increasing success against the Hudson's Bay Company in the regions that later became Western Canada a ...

. Governor William Williams, who had been sent out in 1818, had arrested or captured several North West Company men. The Nor'Westers replied with a Quebec warrant for Williams' arrest. The London governors were unhappy with Williams' clumsy management and both companies were under British pressure to settle their differences. The in Simpson's title meant that if Williams had been arrested, Simpson would take his place. In 1820, he joined the prominent Beaver Club

The Beaver Club was a gentleman's club, gentleman's dining club founded in 1785 by the predominantly English-speaking men who had gained control of the fur trade of Montreal. According to the club's rules, the object of their meeting was "to bring ...

.

He went by ship to New York, by boat and cart to Montreal

Montreal is the List of towns in Quebec, largest city in the Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Quebec, the List of the largest municipalities in Canada by population, second-largest in Canada, and the List of North American cit ...

and left by the usual route for York Factory

York Factory was a settlement and Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) factory (trading post) on the southwestern shore of Hudson Bay in northeastern Manitoba, Canada, at the mouth of the Hayes River, approximately south-southeast of Churchill.

York ...

on Hudson Bay

Hudson Bay, sometimes called Hudson's Bay (usually historically), is a large body of Saline water, saltwater in northeastern Canada with a surface area of . It is located north of Ontario, west of Quebec, northeast of Manitoba, and southeast o ...

. He met Williams at Rock Depot on the Hayes River

The Hayes River is a river in Northern Manitoba, Canada, that flows from Molson Lake to Hudson Bay at York Factory. It was historically an important river in the development of Canada and is now a Canadian Heritage River and the longest natu ...

. Since Williams had not been arrested he was William's subordinate and was sent west to Fort Wedderburn on Lake Athabaska

Lake Athabasca ( ; French: ''lac Athabasca''; from Woods Cree: , "herethere are plants one after another") is in the north-west corner of Saskatchewan and the north-east corner of Alberta between 58° and 60° N in Canada. The lake is ...

. There he spent the winter learning about, and reorganizing, the fur trade. On his return journey in 1821, he learned that the two companies had merged. This put an end to a ruinous and sometimes violent competition and converted the HBC monopoly into an informal government for western Canada. He escorted that year's furs to Rock Depot and returned upriver to Norway House

Norway House is a population centre of over 5,000 people, some north of Lake Winnipeg, on the bank of the eastern channel of the Nelson River, in the province of Manitoba, Canada. The population centre shares the name ''Norway House'' with the ...

for the first meeting of the merged companies. There he learned that he had been made governor of the Northern—that is, western—Department and Williams had been made his equal in the Southern Department south of Hudson Bay. In December 1821, the HBC monopoly was extended to the Pacific coast.

After the meeting he returned downstream to take up his duties at York Factory. In December 1821, he set out on snowshoes for Cumberland House

Cumberland House was a mansion on the south side of Pall Mall in London, England. It was built in the 1760s by Matthew Brettingham for Prince Edward, Duke of York and Albany and was originally called York House. The Duke of York died in 1767 a ...

and then the Red River Colony

The Red River Colony (or Selkirk Settlement), also known as Assiniboia, was a colonization project set up in 1811 by Thomas Douglas, 5th Earl of Selkirk, on of land in British North America. This land was granted to Douglas by the Hudson's Bay ...

. By July 1822, he was back at York Factory for the second meeting of the Northern Council, the first that he chaired. After the meeting he went by water to Lac Île-à-la-Crosse

Lac Île-à-la-Crosse is a Y-shaped lake in the north-central region of the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian province of Saskatchewan along the course of the Churchill River (Hudson Bay), Churchill River. At the centre of the "Y" ...

and then by dog sled to Fort Chipewyan

Fort Chipewyan , commonly referred to as Fort Chip, is an unincorporated hamlet in northern Alberta, Canada, within the Regional Municipality (RM) of Wood Buffalo.

History

Fort Chipewyan is one of the oldest European settlements in the Provi ...

and Fort Resolution

Fort Resolution (''Denı́nu Kų́ę́'' (pronounced "deh-nih-noo-kwenh") "moose island place") is a hamlet in the South Slave Region of the Northwest Territories, Canada. The community is situated at the mouth of the Slave River, on the shores ...

on the Tıdeè Lake. He then went south to Fort Dunvegan

Dunvegan Provincial Park and Historic Dunvegan ( ) are a provincial park and a provincial historic site of Alberta located together on one site. They are located in Dunvegan, at the crossing of Peace River and Highway 2, between Rycroft and Fa ...

on the Peace River

The Peace River () is a river in Canada that originates in the Rocky Mountains of northern British Columbia and flows to the northeast through northern Alberta. The Peace River joins the Athabasca River in the Peace-Athabasca Delta to form the ...

and then Fort Edmonton

Fort Edmonton (also named Edmonton House) was the name of a series of Trading post, trading posts of the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) from 1795 to 1914, all of which were located on the north banks of the North Saskatchewan River in what is now ce ...

and after the thaw, back to York Factory.

Second Trip to the Columbia (1824–25)

In August 1824, he leftYork Factory

York Factory was a settlement and Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) factory (trading post) on the southwestern shore of Hudson Bay in northeastern Manitoba, Canada, at the mouth of the Hayes River, approximately south-southeast of Churchill.

York ...

for the Pacific, taking the unorthodox Nelson

Nelson may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* ''Nelson'' (1918 film), a historical film directed by Maurice Elvey

* ''Nelson'' (1926 film), a historical film directed by Walter Summers

* ''Nelson'' (opera), an opera by Lennox Berkeley to a lib ...

–Burntwood River

The Burntwood River is a river in northeast Manitoba, Canada between the Churchill River and the Nelson River, which passes through Thompson, Manitoba. It is over long and flows mostly east to join the Nelson River at Split Lake, Manitoba.

His ...

route, and ascended the Churchill River and Athabasca River

The Athabasca River (French: ''Rivière Athabasca'') in Alberta, Canada, originates at the Columbia Icefield in Jasper National Park and flows more than before emptying into Lake Athabasca. Much of the land along its banks is protected in nationa ...

s to Jasper House

Jasper House National Historic Site, in Jasper National Park, Alberta, is the second site of a trading post on the Athabasca River that functioned from 1813 to 1884 as a major staging and supply post for travel through the Canadian Rockies.

The ...

at the east side of Athabasca Pass

Athabasca Pass (el. ) is a high mountain pass in the Canadian Rockies on the border between Alberta and British Columbia. In fur trade days it connected Jasper House on the Athabasca River with Boat Encampment on the Columbia River.Whittaker, ...

. He crossed the pass on horseback to Boat Encampment and then down the Columbia River

The Columbia River (Upper Chinook language, Upper Chinook: ' or '; Sahaptin language, Sahaptin: ''Nch’i-Wàna'' or ''Nchi wana''; Sinixt dialect'' '') is the largest river in the Pacific Northwest region of North America. The river headwater ...

, reaching its mouth on November 8 at Fort George, previously named Fort Astoria

Fort Astoria (also named Fort George) was the primary Fur trade, fur trading post of John Jacob Astor's Pacific Fur Company (PFC). A maritime contingent of PFC staff was sent on board the ''Tonquin (1807 ship), Tonquin'', while another party tra ...

. This 80-day journey was 20 days faster than the previous record. He moved the headquarters of the Columbia District

The Columbia District was a fur-trading district in the Pacific Northwest region of North America, in both the United States and British North America in the 19th century. Much of its territory overlapped with the temporarily jointly occupi ...

to Fort Vancouver

Fort Vancouver was a 19th-century fur trading post built in the winter of 1824–1825. It was the headquarters of the Hudson's Bay Company's Columbia Department, located in the Pacific Northwest. Named for Captain George Vancouver, the fort was ...

, guessing that the south side of the river might fall to the Americans.

He left in March 1825, and crossed the snow-covered Athabasca Pass. From Fort Assiniboine

Fort Assiniboine is a hamlet in northwest Alberta, Canada, within Woodlands County. It is located along the north shore of the Athabasca River at the junction of Highway 33 and Highway 661. It is approximately northwest of Barrhead, sou ...

he went on horseback south to Fort Edmonton

Fort Edmonton (also named Edmonton House) was the name of a series of Trading post, trading posts of the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) from 1795 to 1914, all of which were located on the north banks of the North Saskatchewan River in what is now ce ...

on the North Saskatchewan River

The North Saskatchewan River is a glacier-fed river that flows from the Canadian Rockies continental divide east to central Saskatchewan, where it joins with the South Saskatchewan River to make up the Saskatchewan River. Its water flows event ...

. He had ordered this new road laid out on his outward voyage. It was a major saving over the old Methye Portage

The Methye Portage or Portage La Loche in northwestern Saskatchewan was one of the most important portages in the old North American fur trade, fur trade route across Canada. The portage connected the Mackenzie River basin to rivers that ran east ...

route. He went on horseback from Fort Carlton

Fort Carlton was a Hudson's Bay Company fur trading post from 1795 until 1885. It was located along the North Saskatchewan River not far from Duck Lake, Saskatchewan, Duck Lake, in what is now the Canadian province of Saskatchewan. The fort wa ...

to the Red River settlements, and then by boat to York Factory. During this trip his servant, Tom Taylor, became separated on a hunting trip. After searching for half a day, Simpson left Taylor to his fate. Taylor reached the Swan River post after 14 days in the wilderness with no proper equipment.

Third Trip to the Columbia (1828–29)

In 1825, he returned to Britain and learned that William Williams had retired, thereby adding the eastern area to his domain. Returning toMontreal

Montreal is the List of towns in Quebec, largest city in the Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Quebec, the List of the largest municipalities in Canada by population, second-largest in Canada, and the List of North American cit ...

, he went to the Red River settlements, Rock Depot for the annual meeting, the posts on James Bay

James Bay (, ; ) is a large body of water located on the southern end of Hudson Bay in Canada. It borders the provinces of Quebec and Ontario, and is politically part of Nunavut. Its largest island is Akimiski Island.

Numerous waterways of the ...

to inspect his new domain, and back to Montreal. In May 1828, he started his second trip to the Pacific along with his dog, mistress and personal piper, going first to York Factory and then using the Peace River

The Peace River () is a river in Canada that originates in the Rocky Mountains of northern British Columbia and flows to the northeast through northern Alberta. The Peace River joins the Athabasca River in the Peace-Athabasca Delta to form the ...

route. This trip remains the longest North American canoe journey ever made in one season.

Marriage and Knighthood (1830–41)

He returned via Athabasca Pass toMoose Factory

Moose Factory is a community in the Cochrane District, Ontario, Canada. It is located on Moose Factory Island, near the mouth of the Moose River (Ontario), Moose River, which is at the southern end of James Bay. It was the first English language ...

and Montreal and immediately went south to New York and took ship to Liverpool. After a brief courtship he married his first cousin, Frances Ramsay Simpson, in February 1830, and returned with his new wife to New York, Montreal, Michipicoten, Ontario, for the annual meeting, York Factory, and Red River. Here his wife gave birth to his first legitimate child, who soon died. In 1832, John Jacob Astor

John Jacob Astor (born Johann Jakob Astor; July 17, 1763 – March 29, 1848) was a German-born American businessman, merchant, real estate mogul, and investor. Astor made his fortune mainly in a fur trade monopoly, by exporting History of opiu ...

approached Gov. Simpson for talks to restrain liquor

Liquor ( , sometimes hard liquor), spirits, distilled spirits, or spiritous liquor are alcoholic drinks produced by the distillation of grains, fruits, vegetables, or sugar that have already gone through ethanol fermentation, alcoholic ferm ...

from the fur trade, and the two met in New York, but a binding agreement never ensued.

In May 1833, he suffered a mild stroke. He and his wife returned to Scotland, where she remained for the next five years and gave birth to a baby girl. In the spring of 1834, he returned to Canada and attended the Southern Council at Moose Factory in May and the Northern Council at York Factory in June, inspected posts on the Saint Lawrence

Saint Lawrence or Laurence (; 31 December 225 – 10 August 258) was one of the seven deacons of the city of Rome under Pope Sixtus II who were martyred in the Persecution of Christians, persecution of the Christians that the Roman Empire, Rom ...

, and arrived back in England in October 1835.

In the summer of 1838, he went to Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg, formerly known as Petrograd and later Leningrad, is the List of cities and towns in Russia by population, second-largest city in Russia after Moscow. It is situated on the Neva, River Neva, at the head of the Gulf of Finland ...

to negotiate with Baron Ferdinand von Wrangel

Baron Ferdinand Friedrich Georg Ludwig von Wrangel (, Romanization of Russian, tr. ; – ) was a Russia Germans, Russia German (Baltic Germans, Baltic German) explorer and officer in the Imperial Russian Navy, Honorable Member of the Saint P ...

of the Russian-American Company

The Russian-American Company Under the High Patronage of His Imperial Majesty was a state-sponsored chartered company formed largely on the basis of the Shelikhov-Golikov Company, United American Company. Emperor Paul I of Russia chartered the c ...

. The Russians recognized the HBC posts and the HBC agreed to supply the Russian posts. He then went to Montreal, Red River, Moose Factory, the Saint Lawrence posts, and down the Hudson

Hudson may refer to:

People

* Hudson (given name)

* Hudson (surname)

* Hudson (footballer, born 1986), Hudson Fernando Tobias de Carvalho, Brazilian football right-back

* Hudson (footballer, born 1988), Hudson Rodrigues dos Santos, Brazilian f ...

to New York, where he took ship to England. Simpson received the title of Knight Bachelor

The title of Knight Bachelor is the basic rank granted to a man who has been knighted by the monarch but not inducted as a member of one of the organised Order of chivalry, orders of chivalry; it is a part of the Orders, decorations, and medals ...

from Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until Death and state funeral of Queen Victoria, her death in January 1901. Her reign of 63 year ...

, giving him the non-hereditary title of Sir on 25 January 1841.

Circumnavigation (1841–42)

He left London in March 1841, and went by canoe toFort Garry

Fort Garry, also known as Upper Fort Garry, was a Hudson's Bay Company trading post located at the confluence of the Red and Assiniboine rivers in or near the area now known as The Forks in what is now central Winnipeg, Manitoba.

Fort Garr ...

(now the site of Winnipeg

Winnipeg () is the capital and largest city of the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian province of Manitoba. It is centred on the confluence of the Red River of the North, Red and Assiniboine River, Assiniboine rivers. , Winnipeg h ...

). On this part of the trip he was accompanied by James Alexander, 3rd Earl of Caledon

James Du Pre Alexander, 3rd Earl of Caledon (27 July 1812 – 30 June 1855), styled Viscount Alexander from birth until 1839, was a soldier and politician.

Early life

Born into an Ulster-Scots aristocratic family in London, he was the son of the ...

, who left to hunt on the prairie and later published a journal. Travelling on horseback to Fort Edmonton

Fort Edmonton (also named Edmonton House) was the name of a series of Trading post, trading posts of the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) from 1795 to 1914, all of which were located on the north banks of the North Saskatchewan River in what is now ce ...

, Simpson caught up with James Sinclair's wagon train of over 100 settlers heading for the Oregon country

Oregon Country was a large region of the Pacific Northwest of North America that was subject to a long Oregon boundary dispute, dispute between the United Kingdom and the United States in the early 19th century. The area, which had been demarcat ...

, a sign of what would soon destroy his fur trade empire. Instead of taking the usual route, he went to what is now Banff, Alberta

Banff is a resort town in Banff National Park, Alberta, Canada, in Alberta's Rockies along the Trans-Canada Highway, west of Calgary, east of Lake Louise, Alberta, Lake Louise, and above

Banff was the first municipality to incorporate within ...

, made the first recorded passage of the pass named after him in August, and went down the Kootenay River

The Kootenay River or Kootenai River is a major river of the Northwest Plateau in southeastern British Columbia, Canada, and northern Montana and Idaho in the United States. It is one of the uppermost major tributaries of the Columbia River, ...

to Fort Vancouver

Fort Vancouver was a 19th-century fur trading post built in the winter of 1824–1825. It was the headquarters of the Hudson's Bay Company's Columbia Department, located in the Pacific Northwest. Named for Captain George Vancouver, the fort was ...

.

Guessing that the 49th parallel border would be extended to the Pacific and considering the difficulties of the Columbia Bar

The Columbia Bar is a system of bars and shoals at the mouth of the Columbia River spanning the U.S. states of Oregon and Washington. It is one of the most dangerous bar crossings in the world, earning the nickname Graveyard of the Pacific. The ...

, he proposed to move the HBC headquarters to what is now Victoria, British Columbia

Victoria is the capital city of the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian province of British Columbia, on the southern tip of Vancouver Island off Canada's Pacific Ocean, Pacific coast. The city has a population of 91,867, and the Gre ...

, a suggestion that earned him the enmity of John McLoughlin

John McLoughlin, baptized Jean-Baptiste McLoughlin, (October 19, 1784 – September 3, 1857) was a French-Canadian, later American, Chief Factor and Superintendent of the Columbia District of the Hudson's Bay Company at Fort Vancouver from 1 ...

, who had done much to develop the Columbia district. Simpson took the north along the Pacific coast to the Russian post at Sitka, and then another boat as far south as Santa Barbara, stopping at the HBC post of Yerba Buena

Yerba buena or hierba buena is the Spanish name for a number of aromatic plants, most of which belong to the mint family. ''Yerba buena'' translates as "good herb". The specific plant species regarded as ''yerba buena'' varies from region to reg ...

.

At some point he met Mariano Vallejo

Don Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo (July 4, 1807 – January 18, 1890) was a Californio general, statesman, and public figure. He was born a subject of Spain, performed his military duties as an officer of the Republic of Mexico, and shaped the trans ...

, a Californio

Californios (singular Californio) are Californians of Spaniards, Spanish descent, especially those descended from settlers of the 17th through 19th centuries before California was annexed by the United States. California's Spanish language in C ...

statesman and general. He sailed to the HBC post in Hawaii (then known as the Sandwich Islands) in February 1842, and back to Sitka, where he took a Russian ship to Okhotsk

Okhotsk ( rus, Охотск, p=ɐˈxotsk) is an urban locality (a work settlement) and the administrative center of Okhotsky District of Khabarovsk Krai, Russia, located at the mouth of the Okhota River on the Sea of Okhotsk. Population:

...

in June. He went on horseback to Yakutsk

Yakutsk ( ) is the capital and largest city of Sakha, Russia, located about south of the Arctic Circle. Fueled by the mining industry, Yakutsk has become one of Russia's most rapidly growing regional cities, with a population of 355,443 at the ...

, up the Lena River

The Lena is a river in the Russian Far East and is the easternmost river of the three great rivers of Siberia which flow into the Arctic Ocean, the others being Ob (river), Ob and Yenisey. The Lena River is long and has a capacious drainage basi ...

by horse-drawn boat, visited Lake Baikal

Lake Baikal is a rift lake and the deepest lake in the world. It is situated in southern Siberia, Russia between the Federal subjects of Russia, federal subjects of Irkutsk Oblast, Irkutsk Oblasts of Russia, Oblast to the northwest and the Repu ...

, went by horse and later carriage to Saint Petersburg and reached London by ship at the end of October. This trip was documented in his book, ''An overland journey round the world''.

Hawaii

During his visit to Hawaii, he met with KingKamehameha III

Kamehameha III (born Kauikeaouli) (March 17, 1814 – December 15, 1854) was the third king of the Kingdom of Hawaii from 1825 to 1854. His full Hawaiian name was Keaweaweula Kīwalaō Kauikeaouli Kaleiopapa and then lengthened to Keaweaweula K ...

and his advisers. Simpson, along with Timoteo Haalilio and William Richards were commissioned as joint Ministers Plenipotentiary on 8 April 1842. Simpson, shortly thereafter, left for England, via Alaska and Siberia

Siberia ( ; , ) is an extensive geographical region comprising all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has formed a part of the sovereign territory of Russia and its predecessor states ...

, while Haalilio and Richards departed for the United States, via Mexico, on 8 July. The Hawaiian delegation, while in the United States, secured the assurance of President John Tyler

John Tyler (March 29, 1790 – January 18, 1862) was the tenth president of the United States, serving from 1841 to 1845, after briefly holding office as the tenth vice president of the United States, vice president in 1841. He was elected ...

of its recognition of Hawaiian independence on 19 December, and then proceeded to meet Simpson in Europe and secure formal recognition by Great Britain and France. He was instrumental in arranging conferences between Hawaiian representatives and the British Foreign Office which resulted in a British commitment to recognize the independence of the islands. On 17 March 1843, King Louis Philippe I of France

Louis Philippe I (6 October 1773 – 26 August 1850), nicknamed the Citizen King, was King of the French from 1830 to 1848, the penultimate monarch of France, and the last French monarch to bear the title "King". He abdicated from his throne ...

recognized Hawaiian independence at the urging of King Leopold I of Belgium, and on 1 April, Lord Aberdeen

George Hamilton-Gordon, 4th Earl of Aberdeen (28 January 178414 December 1860), styled Lord Haddo from 1791 to 1801, was a British statesman, diplomat and landowner, successively a Tory, Conservative and Peelite politician and specialist in fo ...

on behalf of Queen Victoria, assured the Hawaiian delegation that: "Her Majesty's Government was willing and had determined to recognize the independence of the Sandwich Islands under their present sovereign."

Later life

By then, Simpson and his wife had a large house on theLachine Canal

The Lachine Canal (, ) is a canal passing through the southwestern part of the Island of Montreal, Quebec, Canada, running 14.5 kilometres (9 miles) from the Old Port of Montreal to Lake Saint-Louis, through the boroughs of Lachine (borough), L ...

across from the depot from which the fur brigades started west. He also owned other estates such as a Manor in Coteau-du-Lac

Coteau-du-Lac () is a small city in southwestern Quebec, Canada. It is on the north shore of the St. Lawrence River in the Vaudreuil-Soulanges Regional County Municipality.

The name of the town comes from the French word ''coteau'' which means ...

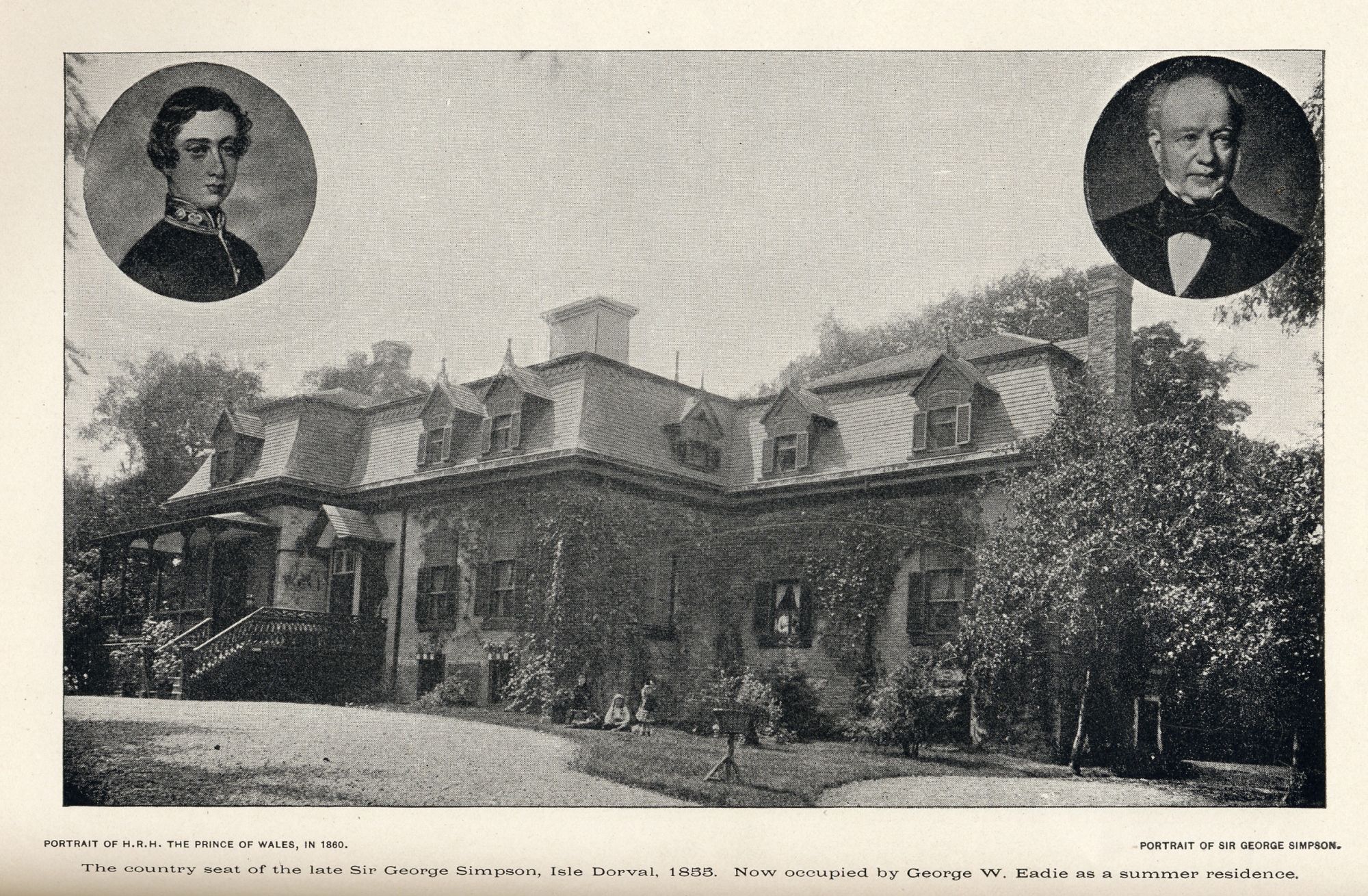

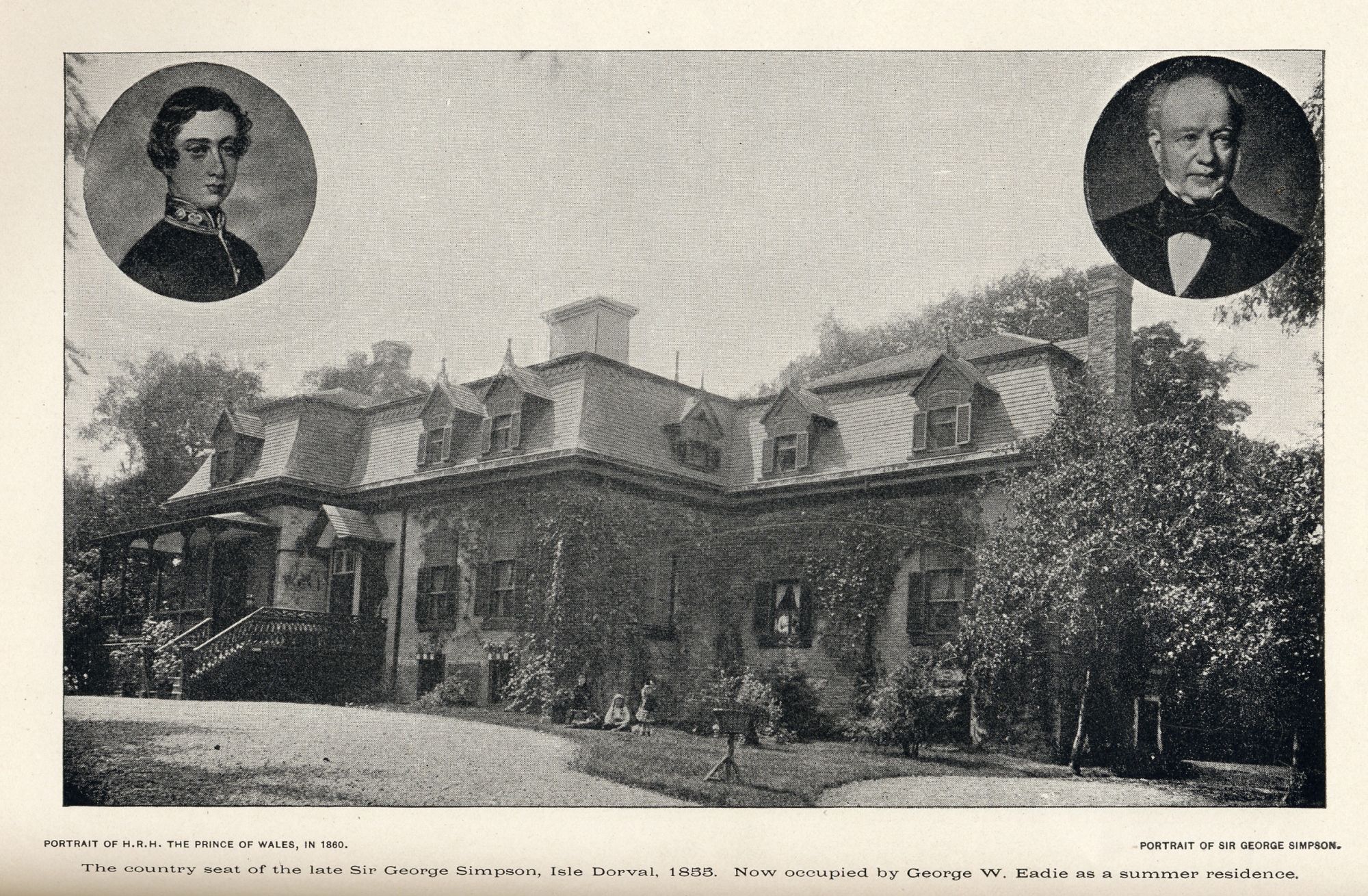

that he sold to the Comte de Beaujeu and Adélaïde de Gaspé, and another estate in Dorval

Dorval (; ) is an Greater Montreal, on-island suburban City (Quebec), city on the island of Montreal in southwestern Quebec, Canada. In 2016, the Canadian Census indicated that the population increased by 4.2% to 18,980. Although the city has t ...

where he received and entertained Prince Edward VII

Edward VII (Albert Edward; 9 November 1841 – 6 May 1910) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 22 January 1901 until Death and state funeral of Edward VII, his death in 1910.

The second child ...

, of the House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha

The House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha ( ; ) is a European royal house of German origin. It takes its name from its oldest domain, the Ernestine duchy of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, and its members later sat on the thrones of Belgium, Bulgaria, Portugal ...

. The Manor's estate included the Fur Trade Depot, and was later sold to Senator Lawrence Alexander Wilson and Lt. Col. W. A. Grant of the Royal Regiment of Canadian Artillery

The Royal Regiment of Canadian Artillery () is the artillery personnel branch of the Canadian Army.

History

Many of the units and batteries of the Royal Regiment of Canadian Artillery are older than the Dominion of Canada itself. The first arti ...

. Lord Donald Smith of Knebworth House

Knebworth House is an English country house in the parish of Knebworth in Hertfordshire, England. It is a Listed building#Categories of listed building, Grade II* listed building. Its gardens are also listed Register of Historic Parks and Gar ...

, Co-Premier of Canada Sir Francis Hincks, and other leading members of Montreal's society would attend Simpson's banquets.

He began investing in banks, railroads, ships, mines and canals. He became a board director and shareholder of Canada’s first bank, the Bank of Montreal

The Bank of Montreal (, ), abbreviated as BMO (pronounced ), is a Canadian multinational Investment banking, investment bank and financial services company.

The bank was founded in Montreal, Quebec, in 1817 as Montreal Bank, making it Canada ...

, as well as of the Bank of British North America

The Bank of British North America was founded by royal charter issued in 1836 in London, England. British North America was the common name by which the British colonies and territories that now comprise Canada were known prior to 1867.

By 189 ...

, the Montreal and Lachine Railroad

The Montreal and Lachine Railroad was Montreal's first railroad. The railroad was opened on November 19, 1847, with service between Bonaventure Station in Montreal and the St. Lawrence River in Lachine. Built to bypass the Lachine Rapids, it was ...

, the Champlain and St. Lawrence Railroad

The Champlain and St. Lawrence Railroad (C&SL) was a historic Rail transport, railway in Lower Canada, the first Canadian public railway and Oldest railroads in North America, one of the first railways built in British North America.

Origin

The ...

, the St. Lawrence and Atlantic Railroad

The St. Lawrence and Atlantic Railroad , known as St-Laurent et Atlantique Quebec in Canada, is a short-line railway operating between Portland, Maine, on the Atlantic Ocean, and Montreal, Quebec, on the St. Lawrence River. It crosses the Ca ...

, the Grand Trunk Railway

The Grand Trunk Railway (; ) was a Rail transport, railway system that operated in the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian provinces of Quebec and Ontario and in the List of states and territories of the United States, American sta ...

, and the Montreal Ocean Steamship Company.

His business partners included Canada's richest man Sir Hugh Allan, Sir John Rose, Sir Alexander Mackenzie

Sir Alexander Mackenzie ( – 12 March 1820) was a Scottish explorer and fur trader known for accomplishing the first crossing of North America north of Mexico by a European in 1793. The Mackenzie River and Mount Sir Alexander are named afte ...

, President David Torrance, minister Luther H. Holton, Senator George Crawford, Senator Thomas Ryan, banker John Redpath

John Redpath (1796 – March 5, 1869) was a Scots-Quebecer businessman and philanthropist who helped pioneer the industrial movement that made Montreal, Quebec, the largest and most prosperous city in Canada.

Early years

In 1796, John Red ...

, and bankers John Molson

John Molson (28 December 1763 – 11 January 1836) was an English people, English-born brewer and entrepreneur in colonial Province of Quebec (1763–91), Quebec, which during his lifetime became Lower Canada. In addition to founding Molson Brewe ...

and William Molson

William Molson (November 5, 1793 – February 18, 1875) was a Canadian politician, entrepreneur and philanthropist. He was the founder and President of Molson Bank, which was in 1925 absorbed by the Bank of Montreal. He was the son of the founde ...

.

With Governor Drummond, Sir Antoine-Aimé Dorion, and John Young, they founded the Transmundane Telegraph Company, but the venture later failed. In the spring of 1845, he went to Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from Virginia, and shares land borders with ...

, to discuss the Oregon boundary with the Americans, which he had already done with Sir Robert Peel

Sir Robert Peel, 2nd Baronet (5 February 1788 – 2 July 1850), was a British Conservative statesman who twice was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom (1834–1835, 1841–1846), and simultaneously was Chancellor of the Exchequer (1834–183 ...

. In 1846, the Oregon Treaty

The Oregon Treaty was a treaty between the United Kingdom and the United States that was signed on June 15, 1846, in Washington, D.C. The treaty brought an end to the Oregon boundary dispute by settling competing American and British claims to ...

established the current border. His wife contracted tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB), also known colloquially as the "white death", or historically as consumption, is a contagious disease usually caused by ''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can al ...

in 1846 and died in 1853.

In 1854, he was able to travel by rail to Chicago

Chicago is the List of municipalities in Illinois, most populous city in the U.S. state of Illinois and in the Midwestern United States. With a population of 2,746,388, as of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, it is the List of Unite ...

before he boarded his voyageur canoe at Sault Ste. Marie Sault Ste. Marie may refer to:

People

* Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians, a Native American tribe in Michigan

Places

* Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario, Canada

** Sault Ste. Marie (federal electoral district), a Canadian federal electora ...

. In 1855, he was in Washington, D.C., and discussed Oregon affairs, and in 1857, defended the HBC monopoly in London. In May 1860, he went by rail to Saint Paul, Minnesota

Saint Paul (often abbreviated St. Paul) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital city of the U.S. state of Minnesota and the county seat of Ramsey County, Minnesota, Ramsey County. As of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, ...

; decided that his health would not bear the trip to Red River; and returned to Lachine.

In August 1860, he entertained the Prince of Wales

Prince of Wales (, ; ) is a title traditionally given to the male heir apparent to the History of the English monarchy, English, and later, the British throne. The title originated with the Welsh rulers of Kingdom of Gwynedd, Gwynedd who, from ...

at Lachine, who came for the inauguration of Victoria Bridge, in honour of his mother Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until Death and state funeral of Queen Victoria, her death in January 1901. Her reign of 63 year ...

. Simpson built :fr:Prince of Wales Terrace, Prince of Wales Terrace in his honour. The building, made of a limestone facade in the Classical Greek Architecture, Greek style, consisted of a row of nine luxurious houses, and was inhabited by Sir William Christopher Macdonald and Mcgill University's Principal William Peterson (academic), William Peterson. It was later demolished to make room for Samuel Bronfman's pavilion, which was seen by Alcan CEO David Culver as an unforgivable act of vandalism.

North American fur trade

The North American fur trade is the (typically) historical Fur trade, commercial trade of furs and other goods in North America, beginning in the eastern provinces of French Canada and the northeastern Thirteen Colonies, American colonies (soon- ...

, he was one of them.

Legacy and death

Shortly after the Princes of Wales's visit, Governor Simpson suffered a massive stroke and died six days later in Lachine. At his death in 1860, he left an estate worth over £100,000, which in relation to GDP, amounted to half a billion dollars in 2023 Canadian money. The amount is also very similar to Harlaxton Manor's building cost. Simpson also gave money to the general endowment of McGill University in 1856, along with Peter McGill and Peter Redpath, among others. James Raffan, author of ''Emperor of the North'', was of the view that Simpson should be counted among Canada’s founding fathers for his role as Governor-in-chief ofRupert's Land

Rupert's Land (), or Prince Rupert's Land (), was a territory in British North America which comprised the Hudson Bay drainage basin. The right to "sole trade and commerce" over Rupert's Land was granted to Hudson's Bay Company (HBC), based a ...

, and its later Canadian Confederation, merger in 1867 to form the ''Dominion of Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its Provinces and territories of Canada, ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, making it the world's List of coun ...

''. Rupert's Land territory was Canada's largest land acquisition to form modern Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its Provinces and territories of Canada, ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, making it the world's List of coun ...

, and included land in Quebec, Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta, the Northwest Territories, Nunavut, Montana, Minnesota, and North Dakota, North and South Dakota. In newspapers and books, he has been referred as the ''King of the Fur-trade'', the ''Emperor of the North'', the ''Emperor of the Plains'', the ''Emperor of Lachine'', the ''Birch-bark Emperor'', and the ''Little Emperor''.

Simpson also had a passion for Napoleon, and was living during his lifetime. It was one of the passions of his life, collecting writing relating to his hero, covering his walls with Napoleonic prints at The Fur Trade at Lachine National Historic Site, Lachine Depot, Norway House

Norway House is a population centre of over 5,000 people, some north of Lake Winnipeg, on the bank of the eastern channel of the Nelson River, in the province of Manitoba, Canada. The population centre shares the name ''Norway House'' with the ...

and Fort Garry

Fort Garry, also known as Upper Fort Garry, was a Hudson's Bay Company trading post located at the confluence of the Red and Assiniboine rivers in or near the area now known as The Forks in what is now central Winnipeg, Manitoba.

Fort Garr ...

, and infecting the factors and fur traders of the Hudson's Bay Company

The Hudson's Bay Company (HBC), originally the Governor and Company of Adventurers of England Trading Into Hudson’s Bay, is a Canadian holding company of department stores, and the oldest corporation in North America. It was the owner of the ...

with them.

Children

Simpson sired at least eleven children by at least seven women, only one of whom was his wife.

During his years in London, he fathered two daughters, born to two separate women. Maria-Louisa, born 1815 to a mother named Maria, and Isabella, born 1817 to an unknown mother. Once Simpson left for Rupert's Land, both daughters were sent to Scotland to be cared for by his relatives.

Sometime during his first year in Rupert's Land, in about 1821, he met and began a relationship with Elizabeth "Betsey" Sinclair, a Métis washerwoman, who he likely met at Fort Wedderburn. He fathered one child with her, a daughter named Maria, who died at age 16 when she drowned while travelling to the Columbia District. Simpson ended their relationship when he began his 1822 trip westward, regarding her as an "unnecessary & expensive appendage" who was of little use to him while he was away travelling.

James Keith Simpson (1823–1901) is poorly documented. Ann Simpson, born in Montreal in 1828, is known only from her baptismal record. Simpson fathered two sons, George Stewart (1827) and John Mackenzie (1829), with Margaret (Marguerite) Taylor. George married Isabella Yale (1840–1927), daughter of fur trader James Murray Yale, of the Yale (surname), Yale family. George was also the brother-in-law of Eliza Yale, wife of Capt. Henry Newsham Peers, grandson of Count Julianus Petrus de Linnée.

Soon after the birth of John Mackenzie, Simpson left Margaret to cousin marriage, marry his cousin. Simpson shocked his peers by neglecting to notify Margaret of his marriage or make any arrangements for the future of his two sons.

Simpson sired at least eleven children by at least seven women, only one of whom was his wife.

During his years in London, he fathered two daughters, born to two separate women. Maria-Louisa, born 1815 to a mother named Maria, and Isabella, born 1817 to an unknown mother. Once Simpson left for Rupert's Land, both daughters were sent to Scotland to be cared for by his relatives.

Sometime during his first year in Rupert's Land, in about 1821, he met and began a relationship with Elizabeth "Betsey" Sinclair, a Métis washerwoman, who he likely met at Fort Wedderburn. He fathered one child with her, a daughter named Maria, who died at age 16 when she drowned while travelling to the Columbia District. Simpson ended their relationship when he began his 1822 trip westward, regarding her as an "unnecessary & expensive appendage" who was of little use to him while he was away travelling.

James Keith Simpson (1823–1901) is poorly documented. Ann Simpson, born in Montreal in 1828, is known only from her baptismal record. Simpson fathered two sons, George Stewart (1827) and John Mackenzie (1829), with Margaret (Marguerite) Taylor. George married Isabella Yale (1840–1927), daughter of fur trader James Murray Yale, of the Yale (surname), Yale family. George was also the brother-in-law of Eliza Yale, wife of Capt. Henry Newsham Peers, grandson of Count Julianus Petrus de Linnée.

Soon after the birth of John Mackenzie, Simpson left Margaret to cousin marriage, marry his cousin. Simpson shocked his peers by neglecting to notify Margaret of his marriage or make any arrangements for the future of his two sons.

References

Notes

Citations

Works Cited

* * * * * * * * * * * *External links

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Simpson, George 1790s births 1860 deaths Yale family Canadian fur traders Date of birth unknown Hudson's Bay Company people Knights Bachelor Lower Canada people Burials at Mount Royal Cemetery People from Dingwall People from Lachine, Quebec People from Rupert's Land Persons of National Historic Significance (Canada) 19th-century Canadian businesspeople Pre-Confederation Manitoba people Scottish emigrants to pre-Confederation Quebec Scottish explorers of North America Scottish knights Circumnavigators of the globe