George S. Morison (engineer) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

George Shattuck Morison (December 19, 1842 – July 1, 1903) was an American engineer. A classics major at Harvard who trained to be a lawyer, he instead became a

/ref>

Born in

Born in

Alton Bridge, Spanning Mississippi River between IL & MO, Alton, Madison, IL

/ref> * Bellefontaine Bridge *

Historic American Engineering Record (Library of Congress)

– Survey number HAER NE-2. 500+ data pages discuss Chief Engineer George S. Morison and his many bridges * Gerber, E., Prout, H. G., and Schneider, C. C. (1905). “Memoir of George Shattuck Morison.” Trans. Am. Soc. Civ. Eng., Volume 54, 513–521.

Bridges by Morison

at Bridgehunter.com * – Partial listing of Morison's Bridges

Personal stories

by the descendant Elting E. Morison (1986) {{DEFAULTSORT:Morison, George Shattuck 1842 births 1903 deaths Phillips Exeter Academy alumni Harvard Law School alumni People from New Bedford, Massachusetts People from Peterborough, New Hampshire 19th-century American engineers American civil engineers American railroad mechanical engineers Harvard College alumni

civil engineer

A civil engineer is a person who practices civil engineering – the application of planning, designing, constructing, maintaining, and operating infrastructure while protecting the public and environmental health, as well as improving existing i ...

and leading bridge designer in North America during the late 19th century. During his lifetime, bridge design evolved from using 'empirical “rules of thumb” to the use of mathematical analysis techniques'. Some of Morison's projects included several large Missouri River bridges as well as the great cantilever railroad bridge at Memphis, Tennessee

Memphis is a city in Shelby County, Tennessee, United States, and its county seat. Situated along the Mississippi River, it had a population of 633,104 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, making it the List of municipalities in Tenne ...

, and the Boone, Iowa viaduct. Morison served as president of the American Society of Civil Engineers

The American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) is a tax-exempt professional body founded in 1852 to represent members of the civil engineering profession worldwide. Headquartered in Reston, Virginia, it is the oldest national engineering soci ...

(1895) as well as a member of the British Institute of Civil Engineers winning that institution's Telford Medal

The Telford Medal is a prize awarded by the British Institution of Civil Engineers (ICE) for a paper or series of papers. It was introduced in 1835 following a bequest made by Thomas Telford, the ICE's first president. It can be awarded in gold ...

in 1892 for his work on the Memphis bridge. In 1899, he was appointed to the Isthmian Canal Commission

The Isthmian Canal Commission (often known as the ICC) was an American administration commission set up to oversee the construction of the Panama Canal in the early years of American involvement. Established on February 26, 1904, it was given con ...

and recommended it be built at Panama

Panama, officially the Republic of Panama, is a country in Latin America at the southern end of Central America, bordering South America. It is bordered by Costa Rica to the west, Colombia to the southeast, the Caribbean Sea to the north, and ...

.Marianos Jr, W. N. "George Shattuck Morison and the development of bridge engineering." American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) Journal of Bridge Engineering 13.3 (2008): 291-298. Accessed a/ref>

History

Born in

Born in New Bedford, Massachusetts

New Bedford is a city in Bristol County, Massachusetts, United States. It is located on the Acushnet River in what is known as the South Coast region. At the 2020 census, New Bedford had a population of 101,079, making it the state's ninth-l ...

, he was the son of John Hopkins Morison, a Unitarian minister. At age 14, he entered Phillips Exeter Academy

Phillips Exeter Academy (often called Exeter or PEA) is an Independent school, independent, co-educational, college-preparatory school in Exeter, New Hampshire. Established in 1781, it is America's sixth-oldest boarding school and educates an es ...

and graduated by age 16. He went on to Harvard College

Harvard College is the undergraduate education, undergraduate college of Harvard University, a Private university, private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Part of the Harvard Faculty of Arts and Scienc ...

where he was a classmate of philosopher John Fiske. Morison received a Bachelor of Arts

A Bachelor of Arts (abbreviated B.A., BA, A.B. or AB; from the Latin ', ', or ') is the holder of a bachelor's degree awarded for an undergraduate program in the liberal arts, or, in some cases, other disciplines. A Bachelor of Arts deg ...

degree in 1863 when he was just 20. After a brief break he attended Harvard Law School

Harvard Law School (HLS) is the law school of Harvard University, a Private university, private research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1817, Harvard Law School is the oldest law school in continuous operation in the United ...

where he earned a Bachelor of Laws

A Bachelor of Laws (; LLB) is an undergraduate law degree offered in most common law countries as the primary law degree and serves as the first professional qualification for legal practitioners. This degree requires the study of core legal subje ...

degree and was admitted to the New York Bar. In 1867, with only general mathematics

Mathematics is a field of study that discovers and organizes methods, Mathematical theory, theories and theorems that are developed and Mathematical proof, proved for the needs of empirical sciences and mathematics itself. There are many ar ...

training and an aptitude for mechanics

Mechanics () is the area of physics concerned with the relationships between force, matter, and motion among Physical object, physical objects. Forces applied to objects may result in Displacement (vector), displacements, which are changes of ...

, he abandoned the practice of law and pursued a career as a civil engineer

A civil engineer is a person who practices civil engineering – the application of planning, designing, constructing, maintaining, and operating infrastructure while protecting the public and environmental health, as well as improving existing i ...

. He apprenticed under Octave Chanute

Octave Chanute (February 18, 1832 – November 23, 1910) was a French-American civil engineer and aviation pioneer. He advised and publicized many aviation enthusiasts, including the Wright brothers. At his death, he was hailed as the father of ...

, along with Joseph Tomlinson, during the construction of the first bridge to cross the Missouri River

The Missouri River is a river in the Central United States, Central and Mountain states, Mountain West regions of the United States. The nation's longest, it rises in the eastern Centennial Mountains of the Bitterroot Range of the Rocky Moun ...

, the swing-span Hannibal Bridge

The First Hannibal Bridge was the first permanent rail crossing of the Missouri River and helped establish the City of Kansas (renamed Kansas City, Missouri, in 1889) as a major city and rail center. In its early days, it was called the Kans ...

.

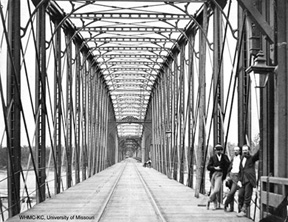

Morison designed many steel

Steel is an alloy of iron and carbon that demonstrates improved mechanical properties compared to the pure form of iron. Due to steel's high Young's modulus, elastic modulus, Yield (engineering), yield strength, Fracture, fracture strength a ...

truss bridge

A truss bridge is a bridge whose load-bearing superstructure is composed of a truss, a structure of connected elements, usually forming triangular units. The connected elements, typically straight, may be stressed from tension, compression, or ...

s, including several crossing the Missouri River, Ohio River

The Ohio River () is a river in the United States. It is located at the boundary of the Midwestern and Southern United States, flowing in a southwesterly direction from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, to its river mouth, mouth on the Mississippi Riv ...

, and the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the main stem, primary river of the largest drainage basin in the United States. It is the second-longest river in the United States, behind only the Missouri River, Missouri. From its traditional source of Lake Ita ...

. The 1892, Memphis Bridge is considered to be his crowning achievement, the largest bridge he designed and the first to span the difficult Lower Mississippi River

The Lower Mississippi River is the portion of the Mississippi River downstream of Cairo, Illinois, Cairo, Illinois. From the Confluence (geography), confluence of the Ohio River and the Middle Mississippi River at Cairo, the Lower flows just u ...

.

Morison was a member of several important engineering committees, the most important of which was the Isthmus Canal Commission

The Isthmian Canal Commission (often known as the ICC) was an American administration commission set up to oversee the construction of the Panama Canal in the early years of American involvement. Established on February 26, 1904, it was given con ...

, where he was instrumental in changing its recommended location from Nicaragua

Nicaragua, officially the Republic of Nicaragua, is the geographically largest Sovereign state, country in Central America, comprising . With a population of 7,142,529 as of 2024, it is the third-most populous country in Central America aft ...

to Panama

Panama, officially the Republic of Panama, is a country in Latin America at the southern end of Central America, bordering South America. It is bordered by Costa Rica to the west, Colombia to the southeast, the Caribbean Sea to the north, and ...

. In '' The Path Between the Seas'', author David McCullough

David Gaub McCullough (; July 7, 1933 – August 7, 2022) was an American popular historian. He was a two-time winner of both the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award. In 2006, he was given the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the United S ...

notes that in the Panama canal affair, "Morison emerges a bit like the butler at the end of the mystery--as the ever-present, frequently unobtrusive, highly instrumental fixture around whom the entire plot turned." McCullough believed that had Morison lived, Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. (October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), also known as Teddy or T.R., was the 26th president of the United States, serving from 1901 to 1909. Roosevelt previously was involved in New York (state), New York politics, incl ...

would have asked him to take a major part in the building of the canal.

In the 1890s, Morison developed a series of lectures — inspired by reading his Harvard classmate Fiske's book ''The Discovery of America'' — on the transformative effects of the new manufacturing power of that era. Though he collected these lectures for publication in 1898, they were not published until 1903, shortly after his death, under the title ''The New Epoch as Developed by the Manufacture of Power''.

Morison died in his rooms at 36 West 50th Street in New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

New York may also refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* ...

, and was buried in Peterborough

Peterborough ( ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city in the City of Peterborough district in the Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county of Cambridgeshire, England. The city is north of London, on the River Nene. A ...

, New Hampshire

New Hampshire ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders Massachusetts to the south, Vermont to the west, Maine and the Gulf of Maine to the east, and the Canadian province of Quebec t ...

, where he had a summer home

A summer house or summerhouse is a building or shelter used for relaxation in warm weather. This would often take the form of a small, roofed building on the grounds of a larger one, but could also be built in a garden or park, often designed t ...

(and designed the town library).

He was the great-uncle of historian of technology Elting E. Morison (1909–1995).

Personality

According to David McCullough, Morison was "arrogant, inflexible, most unpopular, a man who was easy to admire from a distance." According to Elting Morison, his great uncle was rude to waiters, hired a substitute during theCivil War

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

, and "invariably referred to Mexico

Mexico, officially the United Mexican States, is a country in North America. It is the northernmost country in Latin America, and borders the United States to the north, and Guatemala and Belize to the southeast; while having maritime boundar ...

as Pjacko." He "had, like Zeno

Zeno may refer to:

People

* Zeno (name), including a list of people and characters with the given name

* Zeno (surname)

Philosophers

* Zeno of Elea (), philosopher, follower of Parmenides, known for his paradoxes

* Zeno of Citium (333 – 264 B ...

, a conviction that time was a solid. If he made an appointment to confer with a person at 3:15 P.M., as he always put it, at 15:15 hours, that was when they met. Those who arrived earlier waited; those who came at any time after 15:15 never conferred at all." Morison read the ''Anabasis

Anabasis (from Greek ''ana'' = "upward", ''bainein'' = "to step or march") is an expedition from a coastline into the interior of a country. Anabase and Anabasis may also refer to:

History

* '' Anabasis Alexandri'' (''Anabasis of Alexander''), ...

'' in Greek, the ''Aeneid

The ''Aeneid'' ( ; or ) is a Latin Epic poetry, epic poem that tells the legendary story of Aeneas, a Troy, Trojan who fled the Trojan War#Sack of Troy, fall of Troy and travelled to Italy, where he became the ancestor of the Ancient Rome ...

'' in Latin, and the dime novels of Archibald Clavering Gunter

Archibald Clavering Gunter (25 October 1847 – 24 February 1907) was a British-American writer primarily known today for authoring the novel that the film '' A Florida Enchantment'' was based upon, and for his hand in popularizing "Casey at the ...

in English. "He thought that people who were good with animals, particularly horses, were popular with their fellows and loose in their morals. When he himself drove a horse, he brought it to a full stop by saying, 'Whoa, cow.'" One Sunday Morison walked out of church when the minister preached that silver should be coined at a ratio of 16 to 1, telling the minister that "he should never try to deal with a subject he obviously didn't understand." Of his neighbor, composer Edward MacDowell

Edward Alexander MacDowell (December 18, 1860January 23, 1908) was an American composer and pianist of the late Romantic period. He was best known for his second piano concerto and his piano suites '' Woodland Sketches'', ''Sea Pieces'' and ''Ne ...

, Morison said, he was "a man with whom I had absolutely nothing in common." Between 1893 and 1897, Morison, a bachelor, built a house of about 57 rooms so, he said, that he would "have a place to eat Thanksgiving

Thanksgiving is a national holiday celebrated on various dates in October and November in the United States, Canada, Saint Lucia, Liberia, and unofficially in countries like Brazil and Germany. It is also observed in the Australian territory ...

dinner and to watch the sun set over Mount Monadnock

Mount Monadnock, or Grand Monadnock, is a mountain in the town of Jaffrey, New Hampshire. It is the most prominent mountain peak in southern New Hampshire and is the highest point in Cheshire County, New Hampshire, Cheshire County. It lies sou ...

." A fellow engineer, one Fullerton L. Waldo, wrote that he hated eating lunch with Morison, "but I'd trust his judgment sooner than that of any other engineer I know."

See also

* Alton Bridge/ref> * Bellefontaine Bridge *

Burlington Rail Bridge

The Burlington Bridge is a vertical-lift railroad bridge across the Mississippi River between Burlington, Iowa, and Gulfport, Illinois, United States. It is owned by BNSF Railway and carries two tracks which are part of BNSF's Chicago–Denver ...

* Cairo Rail Bridge

Cairo Rail Bridge is the name of two bridges crossing the Ohio River near Cairo, Illinois in the United States. The original was an 1889 George S. Morison through-truss and deck truss bridge, replaced by the current bridge in 1952. The second a ...

* Maroon Creek Bridge

*Merchants Bridge

The Merchants Bridge, officially the Merchants Memorial Mississippi Rail Bridge, is a rail bridge crossing the Mississippi River between St. Louis, Missouri, and Venice, Illinois. The bridge is owned by the Terminal Railroad Association of St ...

* Frisco Bridge

The Frisco Bridge, previously known as the Memphis Bridge, is a cantilevered through truss bridge carrying a rail line across the Mississippi River between West Memphis, Arkansas, and Memphis, Tennessee.

Construction

At the time of the Memph ...

* Taft Bridge

The Taft Bridge (also known as the Connecticut Avenue Bridge or William Howard Taft Bridge) is a historic bridge located in the Northwest quadrant of Washington, D.C. Built in 1906, it carries Connecticut Avenue over the Rock Creek gorge, includ ...

References

Sources

Historic American Engineering Record (Library of Congress)

– Survey number HAER NE-2. 500+ data pages discuss Chief Engineer George S. Morison and his many bridges * Gerber, E., Prout, H. G., and Schneider, C. C. (1905). “Memoir of George Shattuck Morison.” Trans. Am. Soc. Civ. Eng., Volume 54, 513–521.

External links

*Bridges by Morison

at Bridgehunter.com * – Partial listing of Morison's Bridges

Personal stories

by the descendant Elting E. Morison (1986) {{DEFAULTSORT:Morison, George Shattuck 1842 births 1903 deaths Phillips Exeter Academy alumni Harvard Law School alumni People from New Bedford, Massachusetts People from Peterborough, New Hampshire 19th-century American engineers American civil engineers American railroad mechanical engineers Harvard College alumni