George Murray Levick on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

George Murray Levick (3 July 1876 – 30 May 1956) was a British Antarctic explorer,

George Murray Levick (3 July 1876 – 30 May 1956) was a British Antarctic explorer,

George Murray Levick (3 July 1876 – 30 May 1956) was a British Antarctic explorer,

George Murray Levick (3 July 1876 – 30 May 1956) was a British Antarctic explorer, naval surgeon

A naval surgeon, or less commonly ship's doctor, is the person responsible for the health of the ship's company aboard a warship. The term appears often in reference to Royal Navy's medical personnel during the Age of Sail.

Ancient uses

Specialis ...

and founder of the Public Schools Exploring Society.

Early life

Levick was born inNewcastle upon Tyne

Newcastle upon Tyne, or simply Newcastle ( , Received Pronunciation, RP: ), is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and metropolitan borough in Tyne and Wear, England. It is England's northernmost metropolitan borough, located o ...

, the son of civil engineer George Levick and Jeannie Sowerby. His elder sister was the sculptor Ruby Levick. He studied medicine at St Bartholomew's Hospital

St Bartholomew's Hospital, commonly known as Barts, is a teaching hospital located in the City of London. It was founded in 1123 by Rahere, and is currently run by Barts Health NHS Trust.

History

Early history

Barts was founded in 1123 by ...

and was commissioned a surgeon in the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

in November 1902. He was secretary of the Royal Navy Rugby Union at its founding in 1907.

Career

''Terra Nova'' expedition and trauma

He was given leave of absence to accompanyRobert Falcon Scott

Captain Robert Falcon Scott (6 June 1868 – ) was a British Royal Navy officer and explorer who led two expeditions to the Antarctic regions: the Discovery Expedition, ''Discovery'' expedition of 1901–04 and the Terra Nova Expedition ...

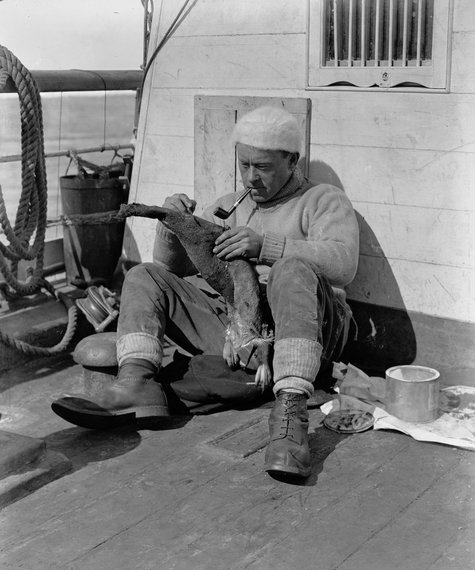

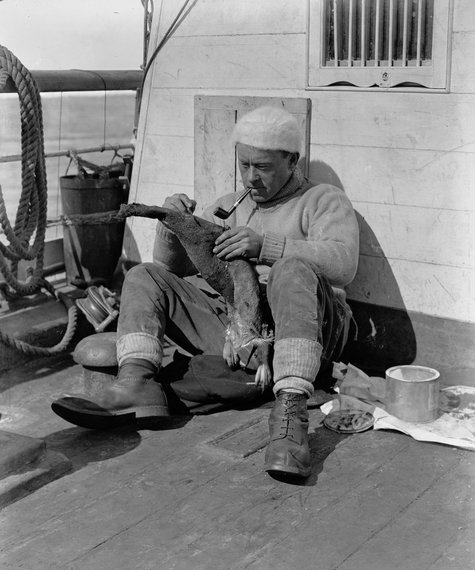

as surgeon and zoologist on his ''Terra Nova'' expedition. Levick photographed extensively throughout the expedition. Prevented by pack ice from embarking on the in February 1912, Levick and the other five members of the party ( Victor L. A. Campbell, Raymond Priestley, George P. Abbott, Harry Dickason, and Frank V. Browning) were forced to overwinter on Inexpressible Island in a cramped ice cave.

Part of the Northern Party, Levick spent the austral summer of 1911–1912 at Cape Adare in the midst of an Adélie penguin

The Adélie penguin (''Pygoscelis adeliae'') is a species of penguin common along the entire coast of the Antarctic continent, which is the only place where it is found. It is the most widespread penguin species, and, along with the emperor peng ...

rookery. To date, this has been the only study of the Cape Adare rookery

A rookery is a colony of breeding rooks, and more broadly a colony of several types of breeding animals, generally gregarious birds.

Coming from the nesting habits of rooks, the term is used for corvids and the breeding grounds of colony-fo ...

, the largest Adélie penguin colony in the world, and he has been the only one to spend an entire breeding cycle there. His observations of the courting, mating, and chick-rearing behaviours of these birds are recorded in his book ''Antarctic Penguins''. A manuscript he wrote about the penguins' sexual habits, which included sexual coercion

Rape is a type of sexual assault involving sexual intercourse, or other forms of sexual penetration, carried out against a person without consent. The act may be carried out by physical force, coercion, abuse of authority, or against a person w ...

, sex among males and sex with dead females, was deemed too indecent by the Keeper of Zoology at the British Museum of Natural History, Sir Sidney Harmer, and prevented from being published.

Nearly 100 years later, the manuscript was rediscovered and published in the journal ''Polar Record

''Polar Record'' is a quarterly peer-reviewed academic journal covering all aspects of Arctic and Antarctic exploration and research. It is managed by the Scott Polar Research Institute and published by Cambridge University Press. The journal was ...

'' in 2012. The discovery significantly illuminates the behaviour of a species that is an indicator of climate change

Present-day climate change includes both global warming—the ongoing increase in Global surface temperature, global average temperature—and its wider effects on Earth's climate system. Climate variability and change, Climate change in ...

. In 2013, Levick's photography notebook was found by a member of the Antarctic Heritage Trust. It was found outside Scott's 1911 Cape Evans base. The notebook contains Levick's pencil notes detailing the date, subjects and exposure details for the photographs he took while at Cape Adare. After conservation it was returned to Antarctica. This notebook should not be confused with Levick's notebooks of his zoological records at Cape Adare, of which the first volume contains his revelations about the mating behaviour of the penguins.

Apsley Cherry-Garrard

Apsley George Benet Cherry-Garrard (2 January 1886 – 18 May 1959) was an English explorer of Antarctica. He was a member of the Terra Nova Expedition, ''Terra Nova'' expedition and is acclaimed for his 1922 account of this expedition, ''T ...

described the difficulties endured by the party in the winter of 1912:

First World War

On his return, Levick served in theGrand Fleet

The Grand Fleet was the main battlefleet of the Royal Navy during the First World War. It was established in August 1914 and disbanded in April 1919. Its main base was Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands.

History

Formed in August 1914 from th ...

and at Gallipoli

The Gallipoli Peninsula (; ; ) is located in the southern part of East Thrace, the European part of Turkey, with the Aegean Sea to the west and the Dardanelles strait to the east.

Gallipoli is the Italian form of the Greek name (), meaning ' ...

on board during the First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

. He was specially promoted in 1915 to the rank of fleet surgeon for his services with the Antarctic Expedition. He married Edith Audrey Mayson Beeton, a granddaughter of Isabella Beeton, on 16 November 1918.

After his retirement from the Royal Navy he pioneered the training of blind people in physiotherapy against much opposition. In 1932, he founded the Public Schools Exploring Society, which took groups of schoolboys to Scandinavia and Canada, and remained its president until his death in June 1956.

Second World War

In 1940, at the beginning ofWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, he returned to the Royal Navy, at the age of 64, to take up a position, as a specialist in guerrilla warfare, at the Commando

A commando is a combatant, or operative of an elite light infantry or special operations force, specially trained for carrying out raids and operating in small teams behind enemy lines.

Originally, "a commando" was a type of combat unit, as oppo ...

Special Training Centre at Lochailort

Lochailort ( , ) is a hamlet in Scotland that lies at the head of Loch Ailort, a sea loch, on the junction of the Road to the Isles (A830 road, A830) between Fort William, Highland, Fort William and Mallaig with the A861 road, A861 towards Salen, ...

, on the west coast of Scotland. He taught fitness, diet and survival techniques, many of which were published in his 1944 training manual ''Hardening of Commando Troops for Warfare''.

He was one of the consultants for Operation Tracer; in the event that Gibraltar

Gibraltar ( , ) is a British Overseas Territories, British Overseas Territory and British overseas cities, city located at the southern tip of the Iberian Peninsula, on the Bay of Gibraltar, near the exit of the Mediterranean Sea into the A ...

was taken by the Axis powers, a small party was to be sealed into a secret chamber, dubbed ''Stay Behind Cave'', in the Rock of Gibraltar to report enemy movements.

Death

Levick died on 30 May 1956 at the age of 79. At the time of his death, Major D. Glyn Owen, chairman of the British Exploring Society wrote: "A truly great Englishman has passed from our midst, but the memory of his nobleness of character and our pride in his achievements cannot pass from us. Having been on Scott's last Antarctic expedition, Murray Levick was later to resolve that exploring facilities for youth should be created under as rigorous conditions as could be made available. With his usual untiring energy and purposefulness he turned this concept into reality when he founded the Public Schools Exploring Society in 1932, later to become the British Schools Exploring Society, drawing schoolboys of between 16 and 18½ years to partake in annual expeditions abroad into wild and trackless country."British Schools Exploring Society Annual Report, 1956.References

Further reading

* Davis, Lloyd Spencer (2019). A Polar Affair: Antarctica's Forgotten Hero and the Secret Love Lives of Penguins. New York: Pegasus Books. * Hooper, Meredith (2010). ''The Longest Winter: Scott's Other Heroes''. London: John Murray.External links

* * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Levick, George Murray 1876 births 1956 deaths Alumni of the Medical College of St Bartholomew's Hospital English explorers 20th-century British explorers 20th-century English educators Educators of the blind British explorers of Antarctica People educated at St Paul's School, London People from Newcastle upon Tyne Recipients of the Polar Medal Royal Navy Medical Service officers Royal Navy officers of World War I Royal Navy officers of World War II Terra Nova expedition