George Ernest Morrison on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

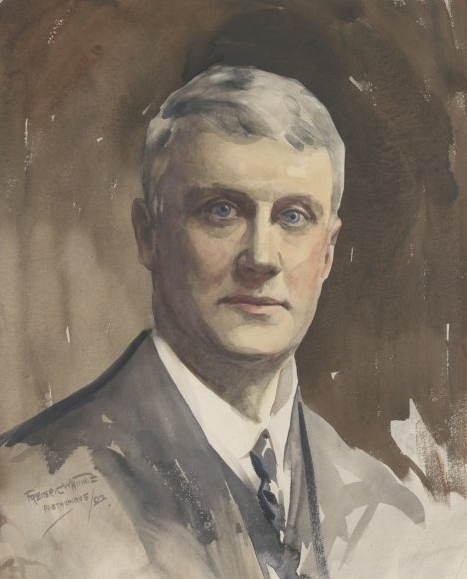

George Ernest Morrison (4 February 1862 – 30 May 1920) was an Australian journalist, political adviser to and representative of the government of the

George Ernest Morrison (4 February 1862 – 30 May 1920) was an Australian journalist, political adviser to and representative of the government of the

"Historical Background"

Official Toyo Bunko website, retrieved 17 November 2009 In 1932, the inaugural George Ernest Morrison Lecture in Ethnology was delivered at

''East Asian History'' 34 (December 2007)

* "The Objects of the Foundation of the Lectureship, and a Review of Dr Morrison's Life in China," W.P. Che

''East Asian History'' Issue 34 (December 2007)

* "Reminiscences of George E. Morrison; and Chinese Abroad,"

''East Asian History'' Issue 34 (December 2007)

,

Digital Archive

of Toyo Bunko Rare Books: 27 rare books selected from the collection of Dr. George Ernest Morrison. * *

"Dr George Morrison and his Correspondence," An Appreciation by C.P. FitzGerald

forward to The Correspondence of George E. Morrison, 1895–1912, edited by Lo Hui-min (Cambridge University Press, 1974), vol.1, pp.vii-xiv. * Linda Jaivin. "Morrison's World" (72nd Annual George E. Morrison Lecture

YouTube

{{DEFAULTSORT:Morrison, George Ernest 1862 births 1920 deaths Australian people of Scottish descent 20th-century Australian geologists People from Geelong The Age (Melbourne) people Burials at Brompton Cemetery People educated at Geelong College War correspondents of the Russo-Japanese War Alumni of the University of Edinburgh Australian book and manuscript collectors People from the Colony of Victoria Australian expatriates in China People of the Boxer Rebellion

George Ernest Morrison (4 February 1862 – 30 May 1920) was an Australian journalist, political adviser to and representative of the government of the

George Ernest Morrison (4 February 1862 – 30 May 1920) was an Australian journalist, political adviser to and representative of the government of the Republic of China

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia. The main geography of Taiwan, island of Taiwan, also known as ''Formosa'', lies between the East China Sea, East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocea ...

during World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, and owner of the then largest Asiatic library ever assembled.

Early life

Morrison was born inGeelong, Victoria

Geelong ( ) (Wathawurrung language, Wathawurrung: ''Djilang''/''Djalang'') is a port city in Victoria, Australia, located at the eastern end of Corio Bay (the smaller western portion of Port Phillip Bay) and the left bank of Barwon River (Victo ...

, Australia. His father George Morrison, who emigrated from Edinkillie, Elgin, Scotland, to Australia in 1858, was headmaster of The Geelong College where Morrison was educated. George Sr married Rebecca Greenwood, of Yorkshire, in 1859, and Morrison was the second child of the marriage. Three of Morrison's seven uncles were rectors of the Presbyterian Church, and two of the four others were principal (Alexander

Alexander () is a male name of Greek origin. The most prominent bearer of the name is Alexander the Great, the king of the Ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia who created one of the largest empires in ancient history.

Variants listed here ar ...

) and master (Robert) of Scotch College, Melbourne

Scotch College is a private, Presbyterian day and boarding school for boys, located in Hawthorn, an inner-eastern suburb of Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.

The college was established in 1851 as The Melbourne Academy in a house in Spri ...

, where George Sr also taught mathematics for six months. Another Uncle, Donald Morrison, was the Rector of The Glasgow Academy

The Glasgow Academy is a coeducational Private schools in the United Kingdom, private day school for pupils aged 3–18 in Glasgow, Scotland. In 2016, it had the third-best Higher level exam results in Scotland. Founded in 1845, it is the oldes ...

between 1861 until 1899. He won Geelong College's Scripture History gold medal in 1876 and, an all-round athlete, the Geelong College Cup for running in 1878.

At 16, Morrison idolised explorer Henry Morton Stanley

Sir Henry Morton Stanley (born John Rowlands; 28 January 1841 – 10 May 1904) was a Welsh-American explorer, journalist, soldier, colonial administrator, author, and politician famous for his exploration of Central Africa and search for missi ...

—so much so, in fact, that he wrote a book on Australian exploration in admiration of him.

During a vacation in early 1880, before his tertiary education, he walked from the heads at Queenscliff, Victoria, to Adelaide

Adelaide ( , ; ) is the list of Australian capital cities, capital and most populous city of South Australia, as well as the list of cities in Australia by population, fifth-most populous city in Australia. The name "Adelaide" may refer to ei ...

, following the coastline, a distance of about 650 miles (960 km) in 46 days. He sold his diary of the journey to the ''Leader'' for seven guineas. Despite having already made up his mind to become a "Special Correspondent", he initially studied medicine at the University of Melbourne

The University of Melbourne (colloquially known as Melbourne University) is a public university, public research university located in Melbourne, Australia. Founded in 1853, it is Australia's second oldest university and the oldest in the state ...

. After passing his first year, the 18-year-old took a vacation trip down the Murray River

The Murray River (in South Australia: River Murray; Ngarrindjeri language, Ngarrindjeri: ''Millewa'', Yorta Yorta language, Yorta Yorta: ''Dhungala'' or ''Tongala'') is a river in Southeastern Australia. It is List of rivers of Australia, Aust ...

in a canoe, the ''Stanley'', from Albury, New South Wales

Albury (; ) is a major regional city that is located in the Murray River, Murray region of New South Wales, Australia. It is part of the twin city of Albury–Wodonga, Albury-Wodonga and is located on the Hume Highway and the northern side of ...

, to its mouth, a distance of some . The first person to do so, he completed the distance in 65 days. Attracted more to adventure than study, he failed his exams two years running (which he later called "one of the fortunate episodes of my life").

Slave ship undercover reporting, 1882

On 1 June 1882, he sailed for theNew Hebrides

New Hebrides, officially the New Hebrides Condominium () and named after the Hebrides in Scotland, was the colonial name for the island group in the South Pacific Ocean that is now Vanuatu. Native people had inhabited the islands for three th ...

, while posing as crew of the brigantine slave ship

Slave ships were large cargo ships specially built or converted from the 17th to the 19th century for transporting Slavery, slaves. Such ships were also known as "Guineamen" because the trade involved human trafficking to and from the Guinea ( ...

, ''Lavinia'', for three months, which sought to "recruit" Kanakas

Kanakas were workers (a mix of voluntary and Blackbirding, involuntary) from various Pacific Islands employed in British Empire, British colonies, such as British Columbia (Canada), Fiji, Solomon Islands, Vanuatu, Papua New Guinea, and Queen ...

, in an undercover reporting scheme that Morrison had hatched for ''The Age

''The Age'' is a daily newspaper in Melbourne, Australia, that has been published since 1854. Owned and published by Nine Entertainment, ''The Age'' primarily serves Victoria (Australia), Victoria, but copies also sell in Tasmania, the Austral ...

''; storied proprietor David Syme had promised £1 a column (), so it's reasonable to believe Morrison was doing this as a moral imperative, not for financial incentive. His eight-part series, "A Cruise in a Queensland Slaver. By a Medical Student" was, by October, also published in the weekly companion publication, '' The Leader''. Written in a tone of wonder, and expressing "only the mildest criticism"; six months later, Morrison "revised his original assessment", describing details of the ''Lavinias blackbirding

Blackbirding was the trade in indentured labourers from the Pacific in the 19th and early 20th centuries. It is often described as a form of slavery, despite the British Slavery Abolition Act 1833 banning slavery throughout the British Empire, ...

operation, and sharply denouncing the slave trade in Queensland. His articles, letters to the editor, and ''The Age'' editorials, sparked considerable debate, leading to government intervention to eradicate what was, by Morrison's account, a slave trade Slave trade may refer to:

* History of slavery - overview of slavery

It may also refer to slave trades in specific countries, areas:

* Al-Andalus slave trade

* Atlantic slave trade

** Brazilian slave trade

** Bristol slave trade

** Danish sl ...

.

New Guinea

Morrison next visitedNew Guinea

New Guinea (; Hiri Motu: ''Niu Gini''; , fossilized , also known as Papua or historically ) is the List of islands by area, world's second-largest island, with an area of . Located in Melanesia in the southwestern Pacific Ocean, the island is ...

and did part of the return journey on a Chinese junk. Landing at Normanton, Queensland

Normanton is an outback town and coastal Suburbs and localities (Australia), locality in the Shire of Carpentaria, Queensland, Australia. At the , the locality of Normanton had a population of 1,391 people, and the town of Normanton had a popula ...

, at the end of 1882, Morrison decided to walk to Melbourne

Melbourne ( , ; Boonwurrung language, Boonwurrung/ or ) is the List of Australian capital cities, capital and List of cities in Australia by population, most populous city of the States and territories of Australia, Australian state of Victori ...

. He was not quite 21, he had no horses or camels, and was unarmed. However, carrying his swag and swimming or wading the rivers in his path, he traversed the necessary 2043 miles (3270 km) in 123 days. No doubt the country had been much opened up in the twenty years since Burke and Wills

The Burke and Wills expedition (originally called the Victorian Exploring Expedition) was an exploration expedition organised by the Royal Society of Victoria (RSV) in Australia in 1860–61.

The exploration party initially consisted of nine ...

' well-funded failure, but the journey was nevertheless a remarkable feat, which stamped Morrison as a great natural bushman

The San peoples (also Saan), or Bushmen, are the members of any of the indigenous hunter-gatherer cultures of southern Africa, and the oldest surviving cultures of the region. They are thought to have diverged from other humans 100,000 to 200 ...

and explorer. He arrived at Melbourne on 21 April 1883 to find that during his journey Thomas McIlwraith

Sir Thomas McIlwraith (17 May 1835 – 17 July 1900) was for many years the dominant figure of colonial politics in Queensland. He was Premier of Queensland from 1879 to 1883, again in 1888, and for a third time in 1893. In common with most po ...

, the premier of Queensland

Queensland ( , commonly abbreviated as Qld) is a States and territories of Australia, state in northeastern Australia, and is the second-largest and third-most populous state in Australia. It is bordered by the Northern Territory, South Austr ...

, had annexed part of New Guinea and was vainly endeavouring to secure the support of the British government for his action.

Financed by ''The Age'' and the ''Sydney Morning Herald

''The Sydney Morning Herald'' (''SMH'') is a daily tabloid newspaper published in Sydney, Australia, and owned by Nine Entertainment. Founded in 1831 as the ''Sydney Herald'', the ''Herald'' is the oldest continuously published newspaper in ...

'', Morrison was sent on an exploration journey to New Guinea

New Guinea (; Hiri Motu: ''Niu Gini''; , fossilized , also known as Papua or historically ) is the List of islands by area, world's second-largest island, with an area of . Located in Melanesia in the southwestern Pacific Ocean, the island is ...

. He sailed from Cooktown, Queensland

Cooktown is a coastal town and suburbs and localities (Australia), locality in the Shire of Cook, Queensland, Australia. Cooktown is at the mouth of the Endeavour River, on Cape York Peninsula in Far North Queensland where James Cook beached h ...

, in a small lugger

A lugger is a sailing vessel defined by its rig, using the lug sail on all of its one or more masts. Luggers were widely used as working craft, particularly off the coasts of France, England, Ireland and Scotland. Luggers varied extensively ...

, arriving at Port Moresby

(; Tok Pisin: ''Pot Mosbi''), also referred to as Pom City or simply Moresby, is the capital and largest city of Papua New Guinea. It is one of the largest cities in the southwestern Pacific (along with Jayapura) outside of Australia and New ...

after a stormy passage. On 24 July 1883, Morrison, with a small party started with the intention of crossing to Dyke Ackland Bay, 100 miles (160 km) away. Much high mountain country barred the way, and it took 38 days to cover 50 miles. The indigenous population became hostile and, about a month later, Morrison was struck by two spears and almost killed. Retracing their steps, with Morrison strapped to a horse, Port Moresby was reached in days. Here Morrison received medical attention, but it was more than a month before he reached the hospital at Cooktown. Morrison had penetrated farther into New Guinea than any previous European. After a week's recovery in hospital, Morrison went on to Melbourne. The head of a spear remained in his groin, however, as surgical removal was not thought feasible at the time by most surgeons.

Education, graduation and further travels

Morrison's father decided to send the young George to John Chiene, professor of surgery at theUniversity of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh (, ; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in Post-nominal letters, post-nominals) is a Public university, public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Founded by the City of Edinburgh Council, town council under th ...

. The professor removed the spear head successfully, and Morrison resumed his medical studies there. He graduated M.B., Ch.M., on 1 August 1887.

After graduation, Morrison travelled extensively in the United States, the West Indies

The West Indies is an island subregion of the Americas, surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea, which comprises 13 independent island country, island countries and 19 dependent territory, dependencies in thr ...

, and Spain, where he became medical officer at the Rio Tinto mine. He then proceeded to Morocco

Morocco, officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It has coastlines on the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria to Algeria–Morocc ...

, became physician to the Shereef of Wazan, and travelled in the interior. Study at Paris, under Dr. Charcot, followed before he returned to Australia in 1890; for two years he was resident surgeon at the Ballarat

Ballarat ( ) () is a city in the Central Highlands of Victoria, Australia. At the 2021 census, Ballarat had a population of 111,973, making it the third-largest urban inland city in Australia and the third-largest city in Victoria.

Within mo ...

Hospital.

East Asia

Leaving the hospital in May 1893, he went to East Asia, and in February 1894 began a journey from Shanghai toRangoon

Yangon, formerly romanized as Rangoon, is the capital of the Yangon Region and the largest city of Myanmar. Yangon was the List of capitals of Myanmar, capital of Myanmar until 2005 and served as such until 2006, when the State Peace and Dev ...

. He went partly by boat up the Yangtze River

The Yangtze or Yangzi ( or ) is the longest river in Eurasia and the third-longest in the world. It rises at Jari Hill in the Tanggula Mountains of the Tibetan Plateau and flows including Dam Qu River the longest source of the Yangtze, i ...

and rode and walked the remainder of the 3,000 miles (4,800 km). Disguised under a hat with queue attached, he completed the journey in 100 days at a total cost of less than £30 (), which included the wages of two or three Chinese servants whom he picked up and changed on the way as he entered new districts. He was quite unarmed and then knew hardly more than a dozen words of Chinese. But he was willing to conform to—and respect—the customs of the people he met, and everywhere he was received with courtesy. In his interesting account of his journey, '' An Australian in China'', which he managed to sell outright for £75 () and have published in 1895, he spoke well of the personalities of the many missionaries he met; however, he thought them outrageously ineffective, citing Yunnan as an example, where 18 missionaries took eight years to convert 11 Chinese. He later regretted this, as he felt he had given a wrong impression by not sufficiently stressing the value of their social and medical work.

After his arrival at Rangoon, Morrison went to Calcutta

Kolkata, also known as Calcutta (List of renamed places in India#West Bengal, its official name until 2001), is the capital and largest city of the Indian States and union territories of India, state of West Bengal. It lies on the eastern ba ...

, where he became seriously ill with intermittent fever and nearly died. Having recovered, he returned to Geelong in November 1894 on the ''Port Melbourne''. He did not stay long. After being refused a job at ''The Argus'' for being unable to "write up to he editor'sstandard", he turned down a lucrative offer to return to medical practice in Ballarat for ship's surgeon on a boat to London. He went to Scotland

Scotland is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It contains nearly one-third of the United Kingdom's land area, consisting of the northern part of the island of Great Britain and more than 790 adjac ...

, presented a thesis to the University of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh (, ; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in Post-nominal letters, post-nominals) is a Public university, public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Founded by the City of Edinburgh Council, town council under th ...

on "The Heredity Factor in the Causation of Various Malformations and Diseases", and received his M.D. degree in August 1895. He was introduced to Moberly Bell, editor of ''The Times'', who appointed him a special correspondent in the East. In November, he went to Siam

Thailand, officially the Kingdom of Thailand and historically known as Siam (the official name until 1939), is a country in Southeast Asia on the Mainland Southeast Asia, Indochinese Peninsula. With a population of almost 66 million, it spa ...

and travelled extensively in the interior.

From Siam, he crossed into southern China, and at Yunnan

Yunnan; is an inland Provinces of China, province in Southwestern China. The province spans approximately and has a population of 47.2 million (as of 2020). The capital of the province is Kunming. The province borders the Chinese provinces ...

fell seriously ill from what he diagnosed to be bubonic plague

Bubonic plague is one of three types of Plague (disease), plague caused by the Bacteria, bacterium ''Yersinia pestis''. One to seven days after exposure to the bacteria, flu-like symptoms develop. These symptoms include fever, headaches, and ...

. Having overcome the illness by inducing profuse perspiration, he then made his way through Siam

Thailand, officially the Kingdom of Thailand and historically known as Siam (the official name until 1939), is a country in Southeast Asia on the Mainland Southeast Asia, Indochinese Peninsula. With a population of almost 66 million, it spa ...

to Bangkok

Bangkok, officially known in Thai language, Thai as Krung Thep Maha Nakhon and colloquially as Krung Thep, is the capital and most populous city of Thailand. The city occupies in the Chao Phraya River delta in central Thailand and has an estim ...

, a journey of nearly a thousand miles.

''The Times'' correspondent

In February 1897, ''The Times'' appointed Morrison as the first permanent correspondent at ''The'' ''Argus'', and he took up his residence there in the following month. Unfortunately, his lack of knowledge in the Chinese language meant that he could not verify his stories and one author has suggested some of his reports contained bias and deliberate lies against China. Seagrave, S. ''Dragon Lady: The Life and Legend of the Last Empress of China'' Vintage Books, 1993. Aware of Russian activity in Manchuria at this time, Morrison went toVladivostok

Vladivostok ( ; , ) is the largest city and the administrative center of Primorsky Krai and the capital of the Far Eastern Federal District of Russia. It is located around the Zolotoy Rog, Golden Horn Bay on the Sea of Japan, covering an area o ...

in June. He travelled over a thousand miles to Stretensk and then across Manchuria to Vladivostok again. He reported to ''The Times'' that Russian engineers were making preliminary surveys from Kirin towards Port Arthur ( Lüshunkou). On the very day his communication arrived in London, 6 March 1898, ''The Times'' received a telegram from Morrison to say that Russia had presented a five-day ultimatum to China demanding the right to construct a railway to Port Arthur. This was a triumph for ''The Times'' and its correspondent, but he had also shown prophetic insight in another phrase of his dispatch, when he stated that "the importance of Japan in relation to the future of Manchuria cannot be disregarded". Germany had occupied Kiao-chao towards the end of 1897, and a great struggle for political preponderacy was going on.

In January 1899, he went to Siam and wrote that there was no need for French interference in that country and that it was quite capable of governing itself. He travelled extensively during the following 15 months, returning first to Peking

Beijing, previously romanized as Peking, is the capital city of China. With more than 22 million residents, it is the world's most populous national capital city as well as China's second largest city by urban area after Shanghai. It is l ...

, then on to Korea, Assam

Assam (, , ) is a state in Northeast India, northeastern India, south of the eastern Himalayas along the Brahmaputra Valley, Brahmaputra and Barak River valleys. Assam covers an area of . It is the second largest state in Northeast India, nor ...

, England, Australia, Japan and back to Peking via Korea.

The Boxer Uprising

The Boxer Rebellion, also known as the Boxer Uprising, was an anti-foreign, anti-imperialist, and anti-Christian uprising in North China between 1899 and 1901, towards the end of the Qing dynasty, by the Society of Righteous and Harmonious ...

broke out soon after and, during the siege of the legations from June to August, Morrison, an acting-lieutenant, showed great courage, always ready to volunteer in the face of danger. He was superficially wounded in July but was erroneously reported as killed and the subject of a highly laudatory obituary notice occupying two columns of ''The Times'' on 17 July 1900. After a siege of 55 days, the legations were relieved on 14 August 1900 by an army of various nationalities under General Alfred Gaselee

General Sir Alfred Gaselee, , (3 June 1844 – 29 March 1918) was a soldier who served in the British Indian Army.

Early life

Gaselee was born at Little Yeldham, Essex, the eldest son of the Reverend John Gaselee, rector of Little Yeldham, a ...

. The army then ransacked much of the palaces in Peking, with Morrison taking part in the looting, making off with silks, furs, porcelain and bronzes.

When the Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War (8 February 1904 – 5 September 1905) was fought between the Russian Empire and the Empire of Japan over rival imperial ambitions in Manchuria and the Korean Empire. The major land battles of the war were fought on the ...

broke out on 10 February 1904, Morrison became a correspondent with the Japanese army. He was present at the entry of the Japanese into Port Arthur (now Lüshunkou) early in 1905, and represented ''The Times'' at the Portsmouth, New Hampshire

Portsmouth is a city in Rockingham County, New Hampshire, Rockingham County, New Hampshire, United States. At the 2020 United States census, 2020 census it had a population of 21,956. A historic seaport and popular summer tourist destination on ...

, United States, peace conference. In 1907, he crossed China from Peking to the French border of Tonkin

Tonkin, also spelled Tongkin, Tonquin or Tongking, is an exonym referring to the northern region of Vietnam. During the 17th and 18th centuries, this term referred to the domain '' Đàng Ngoài'' under Trịnh lords' control, including both the ...

, and, in 1910, rode from Honan City, Burma

Myanmar, officially the Republic of the Union of Myanmar; and also referred to as Burma (the official English name until 1989), is a country in northwest Southeast Asia. It is the largest country by area in Mainland Southeast Asia and ha ...

, across Asia to Andijan

Andijan ( ), also spelt Andijon () and formerly romanized as Andizhan ( ), is a city in Uzbekistan. It is the administrative, economic, and cultural center of Andijan Region. Andijan is a district-level city with an area of . Andijan is the most ...

in Russian Turkestan

Turkestan,; ; ; ; also spelled Turkistan, is a historical region in Central Asia corresponding to the regions of Transoxiana and East Turkestan (Xinjiang). The region is located in the northwest of modern day China and to the northwest of its ...

, a journey of 3,750 miles (6,000 km), which was completed in 174 days. From Andijan, he took a train to St Petersburg, and then traveled to London, arriving on 29 July 1910.

Morrison returned to China the next year and, when plague broke out in Manchuria

Manchuria is a historical region in northeast Asia encompassing the entirety of present-day northeast China and parts of the modern-day Russian Far East south of the Uda (Khabarovsk Krai), Uda River and the Tukuringra-Dzhagdy Ranges. The exact ...

, went to Harbin

Harbin, ; zh, , s=哈尔滨, t=哈爾濱, p=Hā'ěrbīn; IPA: . is the capital of Heilongjiang, China. It is the largest city of Heilongjiang, as well as being the city with the second-largest urban area, urban population (after Shenyang, Lia ...

, where there had been success in stemming its spread. He wrote a series of articles advocating the launch of modern scientific public health services in China. When the Chinese revolution began in 1911, Morrison took the side of the revolutionaries.

Morrison was a tall and fearless man. He had sought adventure, gathering experience and knowledge as he went. Polly Condit Smith, who was alongside Morrison during the Boxer uprising, wrote: "Although he was not a military man he had proved himself one of the most important members of the garrison, being always in motion and cognizant of what was going on everywhere, and by far the best informed person within the Legation quadrangle. To this must be added a cool judgement, total disregard of danger and a perpetual sense of responsibility to help everyone to do his best – the most attractive at our impromptu mess

The mess (also called a mess deck aboard ships) is a designated area where military personnel socialize, eat and (in some cases) live. The term is also used to indicate the groups of military personnel who belong to separate messes, such as the o ...

, as dirty, happy and healthy a hero as one could find anywhere." Sir Robert Hart, on the other hand, in Peking at the same time as Morrison, regarded him as a lazy, self-indulgent man—intolerant, racist, and unprincipled.

Political adviser

Citing poor pay and lack of prospects, in August 1912 Morrison resigned his position at ''The Times'' to become a political adviser to thePresident

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Film and television

*'' Præsident ...

of the Chinese Republic, at a salary equivalent to £4,000 () a year, and immediately went to London to assist in floating a Chinese loan of £10 million (equivalent to A$ million in ). In China, during the following years, he had an anxious time advising upon, and endeavouring to deal with, the political intrigues that prevailed. He was instrumental in ensuring that Peking foster its relations with the United States over Japan during this period. He visited Australia, again, in December 1917, and returned to Peking, in February 1918. He represented China during the peace discussions at Versailles

The Palace of Versailles ( ; ) is a former royal residence commissioned by King Louis XIV located in Versailles, Yvelines, Versailles, about west of Paris, in the Yvelines, Yvelines Department of Île-de-France, Île-de-France region in Franc ...

, in 1919, but his health began to decline, and he retired to England.

Personal life

Morrison had married, in 1912, Jennie Wark Robin (1889–1923), his former secretary, who survived him by only three years. His three sons, Ian (1913–1950), Alastair Gwynne (1915–2009), and Colin (1917–1990), all grew to adulthood and graduated at theUniversity of Cambridge

The University of Cambridge is a Public university, public collegiate university, collegiate research university in Cambridge, England. Founded in 1209, the University of Cambridge is the List of oldest universities in continuous operation, wo ...

. He died on 30 May 1920, at Sidmouth

Sidmouth () is a town on the English Channel in Devon, South West England, southeast of Exeter. With a population of 13,258 in 2021, it is a tourist resort and a gateway to the Jurassic Coast World Heritage Site. A large part of the town has ...

, Devon, and is buried there.

Legacy

In his role as adviser to the president of China, Morrison is credited with having a significant influence on China's decision to enter World War I in opposition to Germany, and in its foreign relations thereafter. Morrison could not speak Chinese fluently, but he was an avid collector of books on China in Western languages. In 1917, Morrison's remarkable library, which contained the largest number of books on China ever collected, was sold to Baron Iwasaki Hisaya, son of Iwasaki Yatarō, the founder ofMitsubishi Corporation

is a Japanese general trading company ( ''sogo shosha'') and a core member of the Mitsubishi Group. For much of the post-war period, Mitsubishi Corporation has been the largest of the five great ''sogo shosha'' (Mitsubishi, Mitsui, Itochu, S ...

, of Tokyo, for £35,000 (equivalent to $ in ), with the provisos that it remain intact and that serious students should have access to it. It had taken 18 years at a cost, by 1912, of £12,000 (equivalent to $ in ) for Morrison to accumulate—ultimately, some 24,000 works. He had no other assets of note at the time of the sale.

The collection, considered by far the most extensive Asiatic library ever assembled, subsequently became the foundation of the Oriental Library in Tokyo.Official Toyo Bunko website, retrieved 17 November 2009 In 1932, the inaugural George Ernest Morrison Lecture in Ethnology was delivered at

Canberra

Canberra ( ; ) is the capital city of Australia. Founded following the Federation of Australia, federation of the colonies of Australia as the seat of government for the new nation, it is Australia's list of cities in Australia, largest in ...

, a fund having been established by Chinese residents of Australia to provide for an annual lecture in Morrison's memory.

Morrison's diaries, manuscripts and papers were bequeathed to the Mitchell Library, Sydney, Australia.

A fictional account of Morrison's romantic affair with Mae Ruth Perkins was published in '' A Most Immoral Woman'' by Australian author Linda Jaivin in 2009.

See also

* Anglo-Chinese relations * Sinophilia *Ernest Satow

Sir Ernest Mason Satow (30 June 1843 – 26 August 1929), was a British diplomat, scholar and Japanologist. He is better known in Japan, where he was known as , than in Britain or the other countries in which he served as a diplomat. He was ...

who met Morrison many times in Peking, 1900–06

Notes

References

*Further reading

* Lo Hui-min, ''The Correspondence of G.E. Morrison'' – 2 vols, (Cambridge U. Press, 1976). * Clune, Frank, ''Sky High to Shanghai'' – (Angus & Robertson, Sydney 1941). *Peter Thompson and Robert Macklin, ''The man who died twice: the life and adventures of Morrison of Peking'' – (Allen & Unwin, 2004. ) * "The Early Days of the Morrison Lecture," Benjamin Penny''East Asian History'' 34 (December 2007)

* "The Objects of the Foundation of the Lectureship, and a Review of Dr Morrison's Life in China," W.P. Che

''East Asian History'' Issue 34 (December 2007)

* "Reminiscences of George E. Morrison; and Chinese Abroad,"

Wu Lien-Teh

Wu Lien-teh ( zh, t=伍連德, p=Wǔ Liándé, poj=Gó͘ Liân-tek, j=Ng5 Lin4 Dak1; Goh Lean Tuck and Ng Leen Tuck in Minnan and Cantonese transliteration respectively; 10 March 1879 – 21 January 1960) was a Malayan physician renowned for ...

''East Asian History'' Issue 34 (December 2007)

External links

* *J. S. Gregory,,

Australian Dictionary of Biography

The ''Australian Dictionary of Biography'' (ADB or AuDB) is a national co-operative enterprise founded and maintained by the Australian National University (ANU) to produce authoritative biographical articles on eminent people in Australia's ...

, Vol. 10, MUP, 1986, pp. 593–596.

Digital Archive

of Toyo Bunko Rare Books: 27 rare books selected from the collection of Dr. George Ernest Morrison. * *

"Dr George Morrison and his Correspondence," An Appreciation by C.P. FitzGerald

forward to The Correspondence of George E. Morrison, 1895–1912, edited by Lo Hui-min (Cambridge University Press, 1974), vol.1, pp.vii-xiv. * Linda Jaivin. "Morrison's World" (72nd Annual George E. Morrison Lecture

YouTube

{{DEFAULTSORT:Morrison, George Ernest 1862 births 1920 deaths Australian people of Scottish descent 20th-century Australian geologists People from Geelong The Age (Melbourne) people Burials at Brompton Cemetery People educated at Geelong College War correspondents of the Russo-Japanese War Alumni of the University of Edinburgh Australian book and manuscript collectors People from the Colony of Victoria Australian expatriates in China People of the Boxer Rebellion