General Sheridan on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Throughout the war, the Confederacy sent armies out of Virginia through the

Throughout the war, the Confederacy sent armies out of Virginia through the  Sheridan got off to a slow start, needing time to organize and to react to reinforcements reaching Early; Grant ordered him not to launch an offensive "with the advantage against you." And yet Grant expressed frustration with Sheridan's lack of progress. The armies remained unengaged for over a month, causing political consternation in the North as the 1864 election drew near. The two generals conferred on September 16 at Charles Town and agreed that Sheridan would begin his attacks within four days.

On September 19, armed with intelligence about the dispositions and strength of Early's forces around Winchester provided by unionist sympathizer and Quaker teacher

Sheridan got off to a slow start, needing time to organize and to react to reinforcements reaching Early; Grant ordered him not to launch an offensive "with the advantage against you." And yet Grant expressed frustration with Sheridan's lack of progress. The armies remained unengaged for over a month, causing political consternation in the North as the 1864 election drew near. The two generals conferred on September 16 at Charles Town and agreed that Sheridan would begin his attacks within four days.

On September 19, armed with intelligence about the dispositions and strength of Early's forces around Winchester provided by unionist sympathizer and Quaker teacher

Sheridan interpreted Grant's orders liberally and instead of heading to

Sheridan interpreted Grant's orders liberally and instead of heading to

After Gen. Lee's surrender, and that of Gen.

After Gen. Lee's surrender, and that of Gen.  During the

During the

In September 1866, Sheridan was assigned to

In September 1866, Sheridan was assigned to

On June 3, 1875, Sheridan married Irene Rucker, a daughter of Army Quartermaster General

On June 3, 1875, Sheridan married Irene Rucker, a daughter of Army Quartermaster General

In

In  In January 1899, the U.S. Army Transport '' Sheridan'' was named for him. In

In January 1899, the U.S. Army Transport '' Sheridan'' was named for him. In

''Thrilling Days in Army Life''

New York and London, Harper & Bros., 1900. . * Suppiger, Joseph E. "Sheridan, The Life of a General." ''Lincoln Herald'' (Sept 1984), 86#3 pp. 157–70 on prewar; 87#1 pp. 18–26 on 1862–63; 87#2 pp. 49–57, on 1863–64. * Wheelan, Joseph. ''Terrible Swift Sword: The Life of General Philip H. Sheridan''. New York: Da Capo Press, 2012. . Civil War * Bissland, James. ''Blood, Tears, and Glory: How Ohioans Won the Civil War''. Wilmington, OH: Orange Frazer Press, 2007. . * Coffey, David. ''Sheridan's Lieutenants: Phil Sheridan, His Generals, and the Final Year of the Civil War''. Wilmington, DE: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2005. . * Drake, William F. ''Little Phil: The Story of General Philip Henry Sheridan''. Prospect, CT: Biographical Publishing Company, 2005. . * Feis, William B

''Civil War History'' 39#3 (September 1993): 199–215. * Gallagher, Gary W., ed. ''The Shenandoah Valley Campaign of 1864''. Military Campaigns of the Civil War. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006. . * Gallagher, Gary W., ed. ''Struggle for the Shenandoah: Essays on the 1864 Valley Campaign''. Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 1991. . * Miller, Samuel H. "Yellow Tavern." ''Civil War History'' 2#1 (March 1956): 57–81. * Naroll, Raoul S

"Sheridan and Cedar Creek—A Reappraisal."

''Military Affairs'' 16#4 (Winter, 1952): 153–68. * Stackpole, Edward J. ''Sheridan in the Shenandoah: Jubal Early's Nemesis'' Harrisburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 1992. . * Wert, Jeffry D. ''From Winchester to Cedar Creek: The Shenandoah Campaign of 1864''. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1987. . Postwar * Dawson, Joseph G. III. "General Phil Sheridan and Military Reconstruction in Louisiana," ''Civil War History'' 24#2 (June 1978): 133–51. * Richter, William L. "General Phil Sheridan, The Historians, and Reconstruction, ''Civil War History'' 33#2 (June 1987): 131–54. * Taylor, Morris F. "The Carr–Penrose Expedition: General Sheridan's Winter Campaign, 1868–1869." ''Chronicles of Oklahoma'' 51#2 (June 1973): 159–76.

PBS on Sheridan

PBS ''National parks'' on Sheridan, including rare images

''Sheridan's Ride'' poem

* * ttps://web.archive.org/web/20031002045823/http://www.aotc.net/Sheridan.htm Commentary on Sheridan's role at Chickamauga {{DEFAULTSORT:Sheridan, Philip 1831 births 1888 deaths 19th-century American politicians Activists from New York (state) Activists from Ohio American military personnel of the Indian Wars American people of Irish descent Apache Wars Burials at Arlington National Cemetery Catholics from Massachusetts Catholics from Ohio Cavalry commanders Commanding Generals of the United States Army Louisiana Republicans Military personnel from Albany, New York People from Dartmouth, Massachusetts People from Somerset, Ohio People of the Reconstruction Era People of Ohio in the American Civil War People of the Great Sioux War of 1876 Presidents of the National Rifle Association Rogue River Wars Texas Republicans Union army generals United States Military Academy alumni United States military governors

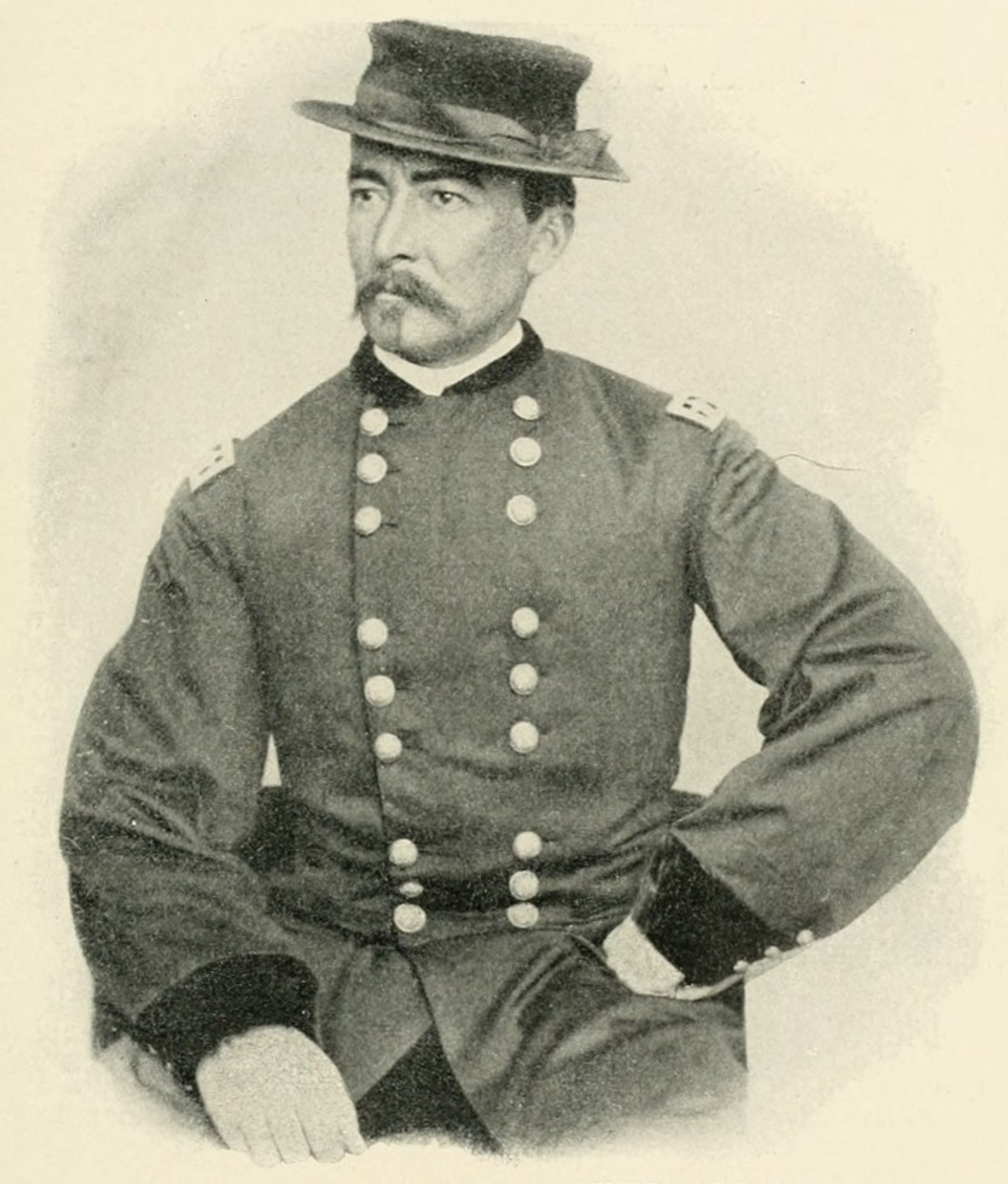

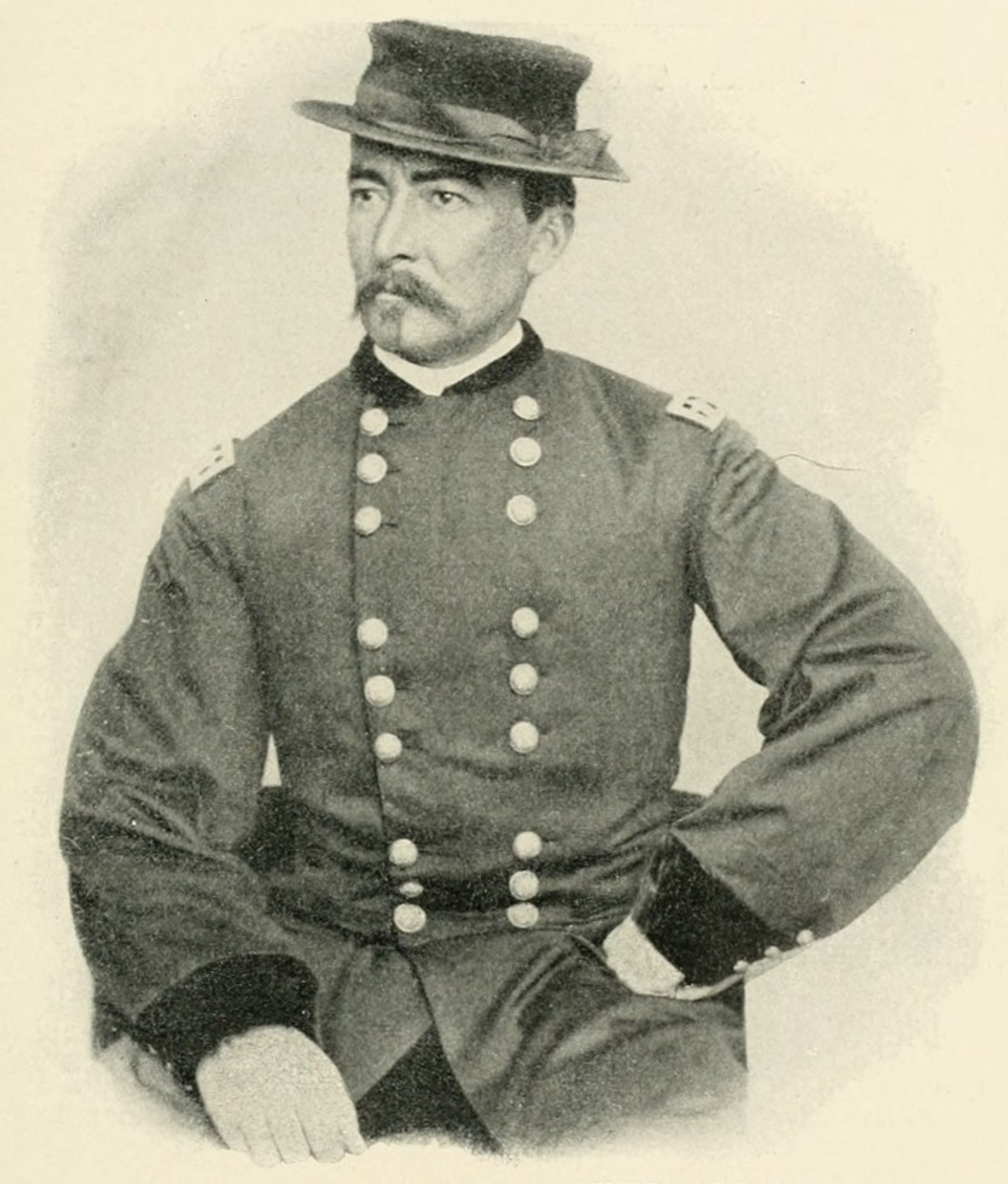

Philip Henry Sheridan (March 6, 1831 – August 5, 1888) was a career

Sheridan was born in

Sheridan was born in

On December 31, 1862, the first day of the

On December 31, 1862, the first day of the

Overland Campaign

The Overland Campaign, also known as Grant's Overland Campaign and the Wilderness Campaign, was a series of battles fought in Virginia during May and June 1864, towards the end of the American Civil War. Lieutenant general (United States), Lt. G ...

" widths="250px" heights="300px">

File:Sheridan's Richmond Raid.png, Sheridan's Richmond Raid, including the Battles of United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the primary Land warfare, land service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is designated as the Army of the United States in the United States Constitution.Article II, section 2, clause 1 of th ...

officer and a Union general

A general officer is an Officer (armed forces), officer of high rank in the army, armies, and in some nations' air force, air and space forces, marines or naval infantry.

In some usages, the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colone ...

in the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

. His career was noted for his rapid rise to major general and his close association with General-in-chief

General-in-chief has been a military rank or title in various armed forces around the world.

France

In France, general-in-chief () was first an informal title for the lieutenant-general commanding over other lieutenant-generals, or even for some ...

Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was the 18th president of the United States, serving from 1869 to 1877. In 1865, as Commanding General of the United States Army, commanding general, Grant led the Uni ...

, who transferred Sheridan from command of an infantry division in the Western Theater to lead the Cavalry Corps of the Army of the Potomac

The Army of the Potomac was the primary field army of the Union army in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was created in July 1861 shortly after the First Battle of Bull Run and was disbanded in June 1865 following the Battle of ...

in the East

East is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from west and is the direction from which the Sun rises on the Earth.

Etymology

As in other languages, the word is formed from the fact that ea ...

. In 1864, he defeated Confederate

A confederation (also known as a confederacy or league) is a political union of sovereign states united for purposes of common action. Usually created by a treaty, confederations of states tend to be established for dealing with critical issu ...

forces under General Jubal Early

Jubal Anderson Early (November 3, 1816 – March 2, 1894) was an American lawyer, politician and military officer who served in the Confederate States Army during the Civil War. Trained at the United States Military Academy, Early resigned his ...

in the Shenandoah Valley

The Shenandoah Valley () is a geographic valley and cultural region of western Virginia and the eastern panhandle of West Virginia in the United States. The Valley is bounded to the east by the Blue Ridge Mountains, to the west by the east ...

and his destruction of the economic infrastructure of the Valley, called "The Burning" by residents, was one of the first uses of scorched-earth

A scorched-earth policy is a military strategy of destroying everything that allows an enemy military force to be able to fight a war, including the deprivation and destruction of water, food, humans, animals, plants and any kind of tools and i ...

tactics in the war. In 1865, his cavalry pursued Gen. Robert E. Lee

Robert Edward Lee (January 19, 1807 – October 12, 1870) was a general officers in the Confederate States Army, Confederate general during the American Civil War, who was appointed the General in Chief of the Armies of the Confederate ...

and was instrumental in forcing his surrender at Appomattox Courthouse.

In his later years, Sheridan fought in the Indian Wars

The American Indian Wars, also known as the American Frontier Wars, and the Indian Wars, was a conflict initially fought by European colonial empires, the United States, and briefly the Confederate States of America and Republic of Texas agains ...

against Native American tribes of the Great Plains

The Great Plains is a broad expanse of plain, flatland in North America. The region stretches east of the Rocky Mountains, much of it covered in prairie, steppe, and grassland. They are the western part of the Interior Plains, which include th ...

. He was instrumental in the development and protection of Yellowstone National Park

Yellowstone National Park is a List of national parks of the United States, national park of the United States located in the northwest corner of Wyoming, with small portions extending into Montana and Idaho. It was established by the 42nd U ...

, both as a soldier and a private citizen. In 1883, Sheridan was appointed general-in-chief of the U.S. Army, and in 1888 he was promoted to the rank of General of the Army

Army general or General of the army is the highest ranked general officer in many countries that use the French Revolutionary System. Army general is normally the highest rank used in peacetime.

In countries that adopt the general officer fou ...

during the term of President Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was the 22nd and 24th president of the United States, serving from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. He was the first U.S. president to serve nonconsecutive terms and the first Hist ...

.

Early life and education

Sheridan was born in

Sheridan was born in Albany, New York

Albany ( ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital city of the U.S. state of New York (state), New York. It is located on the west bank of the Hudson River, about south of its confluence with the Mohawk River. Albany is the oldes ...

, on March 6, 1831, the third of six children of John and Mary Meenagh Sheridan, Irish Catholic

Irish Catholics () are an ethnoreligious group native to Ireland, defined by their adherence to Catholic Christianity and their shared Irish ethnic, linguistic, and cultural heritage.The term distinguishes Catholics of Irish descent, particul ...

immigrants from Killinkere parish in County Cavan

County Cavan ( ; ) is a Counties of Ireland, county in Republic of Ireland, Ireland. It is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Ulster and is part of the Northern and Western Region. It is named after the town of Cavan and is based on the hi ...

, Ireland. He grew up in Somerset, Ohio

Somerset is a village in Perry County, Ohio, United States. The population as of the 2020 census was 1,481. It is located 9.5 miles north of the county seat New Lexington and has a dedicated historical district. Saint Joseph Church, the oldes ...

. Small in stature, he reached only 5 feet 5 inches (165 cm) tall, earning him the nickname, "Little Phil". Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

described his appearance in a famous anecdote: "A brown, chunky little chap, with a long body, short legs, not enough neck to hang him, and such long arms that if his ankles itch he can scratch them without stooping."

As a boy, Sheridan worked in a general store and later as head clerk and bookkeeper at a dry goods store. In 1848, he obtained an appointment to the United States Military Academy

The United States Military Academy (USMA), commonly known as West Point, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York that educates cadets for service as Officer_(armed_forces)#United_States, comm ...

in West Point, New York

West Point is the oldest continuously occupied military post in the United States. Located on the Hudson River in New York (state), New York, General George Washington stationed his headquarters in West Point in the summer and fall of 1779 durin ...

, from a nomination from one of his customers, U.S. Congressman

The United States House of Representatives is a chamber of the bicameral United States Congress; it is the lower house, with the U.S. Senate being the upper house. Together, the House and Senate have the authority under Article One of th ...

Thomas Ritchey, whose first candidate was disqualified after failing a mathematics examination and reportedly displayed a "poor attitude". In his fourth year at West Point, Sheridan was suspended for a year for fighting with classmate William R. Terrill. The previous day, Sheridan had threatened to run him through with a fixed bayonet in reaction to a perceived insult on the parade ground. He graduated in 1853, 34th in his class of 52 cadets.

Sheridan was commissioned as a brevet second lieutenant and was assigned to the 1st U.S. Infantry

The 1st Infantry Regiment is a regiment of the United States Army that draws its lineage from a line of post American Revolutionary War units and is decorated with thirty-nine campaign streamers. The 1st Battalion, 1st Infantry is assigned as ...

Regiment at Fort Duncan

Fort Duncan was a United States Army base, set up to protect the first U.S. settlement on the Rio Grande near the current town of Eagle Pass, Texas.

History

A line of seven army posts was established in 1848–49 after the Mexican War to protec ...

in Eagle Pass, Texas

Eagle Pass is a city in and the county seat of Maverick County, Texas, United States. Its population was 28,130 as of the 2020 census. Eagle Pass borders the city of Piedras Negras, Coahuila, Mexico, which is to the southwest and across the ...

, then to the 4th U.S. Infantry Regiment at Fort Reading in Anderson, California

Anderson is a city in Shasta County, California, approximately south of Redding. Its population is 11,323 as of the 2020 census, up from 9,932 from the 2010 census.

Located north of Sacramento, the city's roots are as a railroad town near ...

. Most of his service with the 4th Infantry was in the Pacific Northwest

The Pacific Northwest (PNW; ) is a geographic region in Western North America bounded by its coastal waters of the Pacific Ocean to the west and, loosely, by the Rocky Mountains to the east. Though no official boundary exists, the most common ...

, starting with a topographical survey mission to the Willamette Valley

The Willamette Valley ( ) is a valley in Oregon, in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States. The Willamette River flows the entire length of the valley and is surrounded by mountains on three sides: the Cascade Range to the east, the ...

in 1855, during which he became involved with the Yakima War

The Yakima War (1855–1858), also referred to as the Plateau War or Yakima Indian War, was a conflict between the United States and the Yakama, a Sahaptian-speaking people of the Northwest Plateau, then part of Washington Territory, and the tr ...

and Rogue River Wars

The Rogue River Wars were an armed conflict in 1855–1856 between the U.S. Army, local militias and volunteers, and the Native American tribes commonly grouped under the designation of Rogue River Indians, in the Rogue Valley area of wha ...

, gaining experience in leading small combat teams and some diplomatic skills in his negotiations with Indian tribes. On March 28, 1857, he was wounded when a bullet grazed his nose at Middle Cascade, Oregon Territory

The Territory of Oregon was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from August 14, 1848, until February 14, 1859, when the southwestern portion of the territory was admitted to the United States, Union as the Oreg ...

. He and an Indian woman from Rogue River lived together during part of his tour of duty. Named Frances

Frances is an English given name or last name of Latin origin. In Latin the meaning of the name Frances is 'from France' or 'the French.' The male version of the name in English is Francis (given name), Francis. The original Franciscus, meaning "F ...

by her white friends, she was the daughter of Takelma

The Takelma (also Dagelma) are a Native American people who originally lived in the Rogue Valley of interior southwestern Oregon.

Most of their villages were sited along the Rogue River. The name ''Takelma'' means "(Those) Along the River".

H ...

Chief Harney.

In March 1861, just before the beginning the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

, Sheridan was promoted to first lieutenant

First lieutenant is a commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces; in some forces, it is an appointment.

The rank of lieutenant has different meanings in different military formations, but in most forces it is sub-divided into a se ...

, and then to captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader or highest rank officer of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police depa ...

in May, just weeks after the war commenced following the Confederate

A confederation (also known as a confederacy or league) is a political union of sovereign states united for purposes of common action. Usually created by a treaty, confederations of states tend to be established for dealing with critical issu ...

attack on Fort Sumter

Fort Sumter is a historical Coastal defense and fortification#Sea forts, sea fort located near Charleston, South Carolina. Constructed on an artificial island at the entrance of Charleston Harbor in 1829, the fort was built in response to the W ...

.

Civil War

Western Theater

In the fall of 1861, Sheridan was ordered to travel toJefferson Barracks

The Jefferson Barracks Military Post is located on the Mississippi River at Lemay, Missouri, south of St. Louis. It was an important and active U.S. Army installation from 1826 through 1946. It is the oldest operating U.S. military installatio ...

, near St. Louis

St. Louis ( , sometimes referred to as St. Louis City, Saint Louis or STL) is an independent city in the U.S. state of Missouri. It lies near the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a populatio ...

, Missouri, for assignment to the 13th U.S. Infantry. He departed from his command of Fort Yamhill

Fort Yamhill was an American military fortification in the state of Oregon. Built in 1856 in the Oregon Territory, it remained an active post until 1866. The Army outpost was used to provide a presence next to the Grand Ronde Agency Coastal Rese ...

in Oregon by way of San Francisco

San Francisco, officially the City and County of San Francisco, is a commercial, Financial District, San Francisco, financial, and Culture of San Francisco, cultural center of Northern California. With a population of 827,526 residents as of ...

, across the Isthmus of Panama

The Isthmus of Panama, historically known as the Isthmus of Darien, is the narrow strip of land that lies between the Caribbean Sea and the Pacific Ocean, linking North America, North and South America. The country of Panama is located on the i ...

, and through New York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

to home in Somerset for a brief leave. On the way to his new post, he made a courtesy call to Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck

Henry Wager Halleck (January 16, 1815 – January 9, 1872) was a senior United States Army officer, scholar, and lawyer. A noted expert in military studies, he was known by a nickname that became derogatory: "Old Brains". He was an important part ...

in St. Louis, who commandeered his services to audit the financial records of his immediate predecessor, Maj. Gen. John C. Frémont

Major general (United States), Major-General John Charles Frémont (January 21, 1813July 13, 1890) was a United States Army officer, explorer, and politician. He was a United States senator from California and was the first History of the Repub ...

, whose administration of the Department of the Missouri

The Department of the Missouri was a command echelon of the United States Army in the 19th century and a sub division of the Military Division of the Missouri that functioned through the Indian Wars.

History

Background

Following the successful ...

was tainted by charges of wasteful expenditures and fraud that left the status of $12 million in debt. Sheridan sorted out the mess, impressing Halleck in the process. Much to Sheridan's dismay, Halleck's vision for Sheridan consisted of a continuing role as a staff officer. Nevertheless, Sheridan performed the task assigned to him and entrenched himself as an excellent staff officer in Halleck's view.

In December, Sheridan was appointed chief commissary officer of the Army of Southwest Missouri, but convinced the department commander, Halleck, to also give him the position of quartermaster general. In January 1862, he reported for duty to Maj. Gen. Samuel Curtis

Samuel Curtis (born in Walworth, Surrey on 29 August 1779-died at La Chaire, Rozel Bay, Jersey, on 6 January 1860

and served under him at the Battle of Pea Ridge

The Battle of Pea Ridge (March 7–8, 1862), also known as the Battle of Elkhorn Tavern, took place during the American Civil War near Leetown, Arkansas, Leetown, northeast of Fayetteville, Arkansas, Fayetteville, Arkansas. United States, Feder ...

. Sheridan soon discovered that officers were engaged in profiteering, including stealing horses from civilians and demanding payment from Sheridan. He refused to pay for the stolen property and confiscated the horses for the use of Curtis's army. When Curtis ordered him to pay the officers, Sheridan brusquely responded, "No authority can compel me to jayhawk or steal." Curtis had Sheridan arrested for insubordination but Halleck's influence appears to have ended any formal proceedings. Sheridan performed aptly in his role under Curtis, and then returned to Halleck's headquarters to accompany the army on the Siege of Corinth

The siege of Corinth, also known as the first battle of Corinth, was an American Civil War engagement lasting from April 29 to May 30, 1862, in Corinth, Mississippi. A collection of Union forces under the overall command of Major General Henry H ...

and serve as an assistant to the department's topographical engineer. He made the acquaintance of Brig. Gen. William T. Sherman

William is a masculine given name of Germanic origin. It became popular in England after the Norman conquest in 1066,All Things William"Meaning & Origin of the Name"/ref> and remained so throughout the Middle Ages and into the modern era. It is ...

, who offered him the role of colonel

Colonel ( ; abbreviated as Col., Col, or COL) is a senior military Officer (armed forces), officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, a colon ...

in an Ohio infantry regiment. The appointment fell through, but Sheridan was subsequently aided by friends, including future Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of the ...

Russell A. Alger

Russell Alexander Alger ( ; February 27, 1836 – January 24, 1907) was an American politician and businessman. He served as the 20th governor of Michigan, U.S. Senator, and U.S. Secretary of War. Alger's life was a "rags-to-riches" success tal ...

, who petitioned Michigan Governor

The governor of Michigan is the head of government of the U.S. state of Michigan. The current governor is Gretchen Whitmer, a member of the Democratic Party, who was inaugurated on January 1, 2019, as the state's 49th governor. She was re-elect ...

Austin Blair

Austin Blair (February 8, 1818 – August 6, 1894) was a politician who served as the 13th governor of Michigan during the American Civil War and in Michigan's House of Representatives and Senate as well as the U.S. Senate. He was known a ...

on his behalf. Sheridan was appointed colonel of the 2nd Michigan Cavalry on May 27, 1862, despite having no experience in the mounted arm.

A month later, Sheridan commanded his first forces in combat, leading a small brigade that included his regiment. At the Battle of Booneville

The Battle of Booneville was fought on July 1, 1862, in Booneville, Mississippi, during the American Civil War. It occurred in the aftermath of the Union victory at the Battle of Shiloh and within the context of Confederate General Braxton Br ...

, Mississippi

Mississippi ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Deep South regions of the United States. It borders Tennessee to the north, Alabama to the east, the Gulf of Mexico to the south, Louisiana to the s ...

, July 1, 1862, he held back several regiments of Brig. Gen. James R. Chalmers

James Ronald Chalmers (January 11, 1831April 9, 1898) was an American politician and senior officer of the Confederate States Army who commanded infantry and cavalry in the Western Theater of the American Civil War.

After the war, Chalmers se ...

's Confederate cavalry, deflected a large flanking attack with a noisy diversion, and reported critical intelligence about enemy dispositions. His actions so impressed the division commanders, including Brig. Gen. William S. Rosecrans, that they recommended Sheridan's promotion to brigadier general. They wrote to Halleck, "Brigadiers scarce; good ones scarce. ... The undersigned respectfully beg that you will obtain the promotion of Sheridan. He is worth his weight in gold." The promotion was approved in September, but dated effective July 1 as a reward for his actions at Booneville. After Booneville, one of his fellow officers gave him the horse that he named Rienzi after the skirmish of Rienzi, Mississippi

Rienzi is a town in Alcorn County, Mississippi, United States. The population was 317 at the 2010 census.

History

Rienzi was named for Cola di Rienzo, a medieval Italian politician. The original town was settled in 1830 and was located one mile ...

, which he rode throughout the Civil War.

Sheridan was assigned to command the 11th Division, III Corps, in Maj. Gen. Don Carlos Buell

Don Carlos Buell (March 23, 1818November 19, 1898) was a United States Army officer who fought in the Seminole War, the Mexican–American War, and the American Civil War. Buell led Union armies in two major Civil War battles— Shiloh and Pe ...

's Army of the Ohio

The Army of the Ohio was the name of two Union Army, Union armies in the American Civil War. The first army became the Army of the Cumberland and the second army was created in 1863.

History

1st Army of the Ohio

General Orders No. 97 appointed ...

. On October 8, 1862, Sheridan led his division in the Battle of Perryville

The Battle of Perryville, also known as the Battle of Chaplin Hills, was fought on October 8, 1862, in the Chaplin Hills west of Perryville, Kentucky, as the culmination of the Confederate Heartland Offensive (Kentucky Campaign) during the Ame ...

. Under orders from Buell and his corps commander, Maj. Gen. Charles Gilbert, Sheridan sent Col. Daniel McCook

Daniel McCook (June 20, 1798 – July 21, 1863) was an attorney and an officer in the Union army during the American Civil War. He was one of two Ohio brothers who, along with 13 of their sons, became widely known as the “Fighting McCook ...

's brigade to secure a water supply for the army. McCook drove off the Confederates and secured water for the parched Union troops at Doctor's Creek. Gilbert ordered McCook not to advance any further and then rode to consult with Buell. Along the way, Gilbert ordered his cavalry to attack the Confederates in Dan McCook's front. Sheridan heard the gunfire and came to the front with another brigade. Although the cavalry failed to secure the heights in front of McCook, Sheridan's reinforcements drove off the Southerners. Gilbert returned and ordered Sheridan to return to McCook's original position. Sheridan's aggressiveness convinced the opposing Confederates under Maj. Gen. Leonidas Polk

Lieutenant-General Leonidas Polk (April 10, 1806 – June 14, 1864) was a Confederate general, a bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of Louisiana and founder of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the Confederate States of America, which separat ...

, that they should remain on the defensive. His troops repelled Confederate attacks later that day, but did not participate in the heaviest fighting of the day, which occurred on the Union left.

On December 31, 1862, the first day of the

On December 31, 1862, the first day of the Battle of Stones River

The Battle of Stones River, also known as the Second Battle of Murfreesboro, was fought from December 31, 1862, to January 2, 1863, in Middle Tennessee, as the culmination of the Stones River Campaign in the Western Theater of the American Ci ...

, Sheridan anticipated a Confederate assault and positioned his division in preparation for it. His division held back the Confederate onslaught on his front until their ammunition ran out and they were forced to withdraw. This action was instrumental in giving the Union army time to rally at a strong defensive position. For his actions, he was promoted to major general on April 10, 1863 (with date of rank December 31, 1862). In six months, he had risen from captain to major general.

The Army of the Cumberland recovered from the shock of Stones River and prepared for its summer offensive against Confederate General Braxton Bragg

Braxton Bragg (March 22, 1817 – September 27, 1876) was an American army Officer (armed forces), officer during the Second Seminole War and Mexican–American War and Confederate General officers in the Confederate States Army, general in th ...

. Sheridan's division participated in the advance against Bragg in Rosecrans's brilliant Tullahoma Campaign, and was the lead division to enter the town of Tullahoma. On the second day of the Battle of Chickamauga

The Battle of Chickamauga, fought on September 18–20, 1863, between the United States Army and Confederate States Army, Confederate forces in the American Civil War, marked the end of a U.S. Army offensive, the Chickamauga Campaign, in southe ...

, September 20, 1863, Rosecrans was shifting Sheridan's division behind the Union battle line when Bragg launched an attack into a gap in the Union line. Sheridan's division made a gallant stand on Lytle Hill against an attack by the Confederate corps of Lt. Gen. James Longstreet

James Longstreet (January 8, 1821January 2, 1904) was a General officers in the Confederate States Army, Confederate general during the American Civil War and was the principal subordinate to General Robert E. Lee, who called him his "Old War Ho ...

, but was swamped by retreating Union soldiers. The Confederates drove Sheridan's division from the field in confusion. He gathered as many men as he could and withdrew toward Chattanooga, rallying troops along the way. Learning of Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas's XIV Corps stand on Snodgrass Hill, Sheridan ordered his division back to the fighting, but they took a circuitous route and did not participate in the fighting as some histories claim. His return to the battlefield ensured that he did not suffer the fate of Rosecrans who was falsely accused of riding off to Chattanooga leaving the army to its fate, and was soon relieved of command.

During the Battle of Chattanooga, at Missionary Ridge on November 25, 1863, Sheridan's division and others in George Thomas's army broke through the Confederate lines in a wild charge that exceeded the orders and expectations of Thomas and Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was the 18th president of the United States, serving from 1869 to 1877. In 1865, as Commanding General of the United States Army, commanding general, Grant led the Uni ...

. Just before his men stepped off, Sheridan told them, "Remember Chickamauga", and many shouted its name as they advanced as ordered to a line of rifle pits in their front. Faced with enemy fire from above, however, they continued up the ridge. Sheridan spotted a group of Confederate officers outlined against the crest of the ridge and shouted, "Here's at you!" An exploding shell sprayed him with dirt and he responded, "That's damn ungenerous! I shall take those guns for that!" The Union charge broke through the Confederate lines on the ridge and Bragg's army fell into retreat. Sheridan impulsively ordered his men to pursue Bragg to the Confederate supply depot at Chickamauga Station, but called them back when he realized that his was the only command so far forward. General Grant reported after the battle, "To Sheridan's prompt movement, the Army of the Cumberland and the nation are indebted for the bulk of the capture of prisoners, artillery, and small arms that day. Except for his prompt pursuit, so much in this way would not have been accomplished."

Overland Campaign

Gen.Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was the 18th president of the United States, serving from 1869 to 1877. In 1865, as Commanding General of the United States Army, commanding general, Grant led the Uni ...

, newly promoted to be general-in-chief of all the Union armies, summoned Sheridan to the Eastern Theater to command the Cavalry Corps of the Army of the Potomac

The Army of the Potomac was the primary field army of the Union army in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was created in July 1861 shortly after the First Battle of Bull Run and was disbanded in June 1865 following the Battle of ...

. Unbeknownst to Sheridan, he was actually Grant's second choice, after Maj. Gen. William B. Franklin

William Buel Franklin (February 27, 1823March 8, 1903) was a career United States Army officer and a Union Army general in the American Civil War. He rose to the rank of a corps commander in the Army of the Potomac, fighting in several notable ba ...

, but Grant agreed to a suggestion about Sheridan from Chief of Staff Henry W. Halleck. After the war, and in his memoirs, Grant claimed that Sheridan was the very man he wanted for the job. Sheridan arrived at the headquarters of the Army of the Potomac on April 5, 1864, less than a month before the start of Grant's massive Overland Campaign

The Overland Campaign, also known as Grant's Overland Campaign and the Wilderness Campaign, was a series of battles fought in Virginia during May and June 1864, towards the end of the American Civil War. Lieutenant general (United States), Lt. G ...

against Robert E. Lee

Robert Edward Lee (January 19, 1807 – October 12, 1870) was a general officers in the Confederate States Army, Confederate general during the American Civil War, who was appointed the General in Chief of the Armies of the Confederate ...

.

In the early battles of the campaign, Sheridan's cavalry was relegated by army commander Maj. Gen. George Meade

George Gordon Meade (December 31, 1815 – November 6, 1872) was an American military officer who served in the United States Army and the Union army as Major General in command of the Army of the Potomac during the American Civil War from 1 ...

to its traditional role, including screening, reconnaissance, and guarding trains and rear areas, much to Sheridan's frustration. In the Battle of the Wilderness

The Battle of the Wilderness was fought on May 5–7, 1864, during the American Civil War. It was the first battle of Lieutenant general (United States), Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant's 1864 Virginia Overland Campaign against General (C ...

(May 5–6, 1864), the dense forested terrain prevented any significant cavalry role. As the army swung around the Confederate right flank in the direction of Spotsylvania Court House

The Battle of Spotsylvania Court House, sometimes more simply referred to as the Battle of Spotsylvania (or the 19th-century spelling Spottsylvania), was the second major battle in Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant and Maj. Gen. George G. Meade's 18 ...

, Sheridan's troopers failed to clear the road from the Wilderness, losing engagements along the Plank Road on May 5 and Todd's Tavern on May 6 through May 8, allowing the Confederates to seize the critical crossroads before the Union infantry could arrive.

Yellow Tavern

The Battle of Yellow Tavern was fought on May 11, 1864, as part of the Overland Campaign of the American Civil War. Union cavalry under Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan was detached from Grant's Army of the Potomac to conduct a raid on Richmond, ...

and Meadow Bridge

File:Sheridan's Trevilian Station Raid.png, Routes of Federal and Confederate cavalry to Trevilian Station, June 7–10, 1864

File:Sheridan's Trevilian Station Raid return.png, Sheridan's return to the Army of the Potomac

The Army of the Potomac was the primary field army of the Union army in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was created in July 1861 shortly after the First Battle of Bull Run and was disbanded in June 1865 following the Battle of ...

from his Trevilian Station raid, including the Battle of Saint Mary's Church

The Battle of Saint Mary's Church (also called Samaria Church in the Southern United States, South, or Nance's Shop) was an American Civil War cavalry battle fought on June 24, 1864, as part of Union Army, Union Lieutenant General (United States ...

When Meade quarreled with Sheridan for not performing his duties of screening and reconnaissance as ordered, Sheridan told Meade that he could "whip Stuart" if Meade let him. Meade reported the conversation to Grant, who replied, "Well, he generally knows what he is talking about. Let him start right out and do it." Meade deferred to Grant's judgment and issued orders to Sheridan to "proceed against the enemy's cavalry" and from May 9 through May 24, sent him on a raid toward Richmond

Richmond most often refers to:

* Richmond, British Columbia, a city in Canada

* Richmond, California, a city in the United States

* Richmond, London, a town in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames, England

* Richmond, North Yorkshire, a town ...

, directly challenging the Confederate cavalry. The raid was less successful than hoped; although his raid managed to mortally wound Confederate cavalry commander Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart at Yellow Tavern

The Battle of Yellow Tavern was fought on May 11, 1864, as part of the Overland Campaign of the American Civil War. Union cavalry under Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan was detached from Grant's Army of the Potomac to conduct a raid on Richmond, ...

on May 11 and beat Maj. Gen. Fitzhugh Lee

Fitzhugh "Fitz" Lee (November 19, 1835 – April 28, 1905) was a Confederate cavalry general in the American Civil War, the 40th Governor of Virginia, diplomat, and United States Army general in the Spanish–American War. He was the son of S ...

at Meadow Bridge on May 12, the raid never seriously threatened Richmond and it left Grant without cavalry intelligence for Spotsylvania and North Anna. Historian Gordon C. Rhea wrote, "By taking his cavalry from Spotsylvania Court House, Sheridan severely handicapped Grant in his battles against Lee. The Union Army was deprived of his eyes and ears during a critical juncture in the campaign. And Sheridan's decision to advance boldly to the Richmond defenses smacked of unnecessary showboating that jeopardized his command."

Rejoining the Army of the Potomac, Sheridan's cavalry fought inconclusively at Haw's Shop (May 28), a battle with heavy casualties that allowed the Confederate cavalry to obtain valuable intelligence about Union dispositions. They seized the critical crossroads that triggered the Battle of Cold Harbor

The Battle of Cold Harbor was fought during the American Civil War near Mechanicsville, Virginia, from May 31 to June 12, 1864, with the most significant fighting occurring on June 3. It was one of the final battles of Union Lt. Gen. Ulysses ...

(June 1 to 12) and withstood a number of assaults until reinforced. Grant then ordered Sheridan on a raid to the northwest to break the Virginia Central Railroad

The Virginia Central Railroad was an early railroad in the U.S. state of Virginia that operated between 1850 and 1868 from Richmond westward for to Covington. Chartered in 1836 as the Louisa Railroad by the Virginia General Assembly, the railr ...

and to link up with the Shenandoah Valley

The Shenandoah Valley () is a geographic valley and cultural region of western Virginia and the eastern panhandle of West Virginia in the United States. The Valley is bounded to the east by the Blue Ridge Mountains, to the west by the east ...

army of Maj. Gen. David Hunter

David Hunter (July 21, 1802 – February 2, 1886) was an American military officer. He served as a Union general during the American Civil War. He achieved notability for his unauthorized 1862 order (immediately rescinded) emancipating slaves ...

. He was intercepted by the Confederate cavalry under Maj. Gen. Wade Hampton Wade Hampton may refer to the following people:

People

*Wade Hampton I (1752–1835), American soldier in Revolutionary War and War of 1812 and U.S. congressman

* Wade Hampton II (1791–1858), American plantation owner and soldier in War of 1812

* ...

at the Battle of Trevilian Station

The Battle of Trevilian Station (also called Trevilians) was fought on June 11–12, 1864, in Union Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant's Overland Campaign against Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia. Union cavalry under Maj ...

(June 11–12), where in the largest all-cavalry battle of the war, he achieved tactical success on the first day, but suffered heavy casualties during multiple assaults on the second. He withdrew without achieving his assigned objectives. On his return march, he once again encountered the Confederate cavalry at Samaria (St. Mary's) Church on June 24, where his men suffered significant casualties, but successfully protected the Union supply wagons they were escorting.

History draws decidedly mixed opinions on the success of Sheridan in the Overland Campaign, in no small part because the very clear Union victory at Yellow Tavern

The Battle of Yellow Tavern was fought on May 11, 1864, as part of the Overland Campaign of the American Civil War. Union cavalry under Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan was detached from Grant's Army of the Potomac to conduct a raid on Richmond, ...

, highlighted by the death of Jeb Stuart, tends to overshadow other actions and battles. In Sheridan's report of the Cavalry Corps' actions in the campaign, discussing the strategy of cavalry fighting cavalry, he wrote, "The result was constant success and the almost total annihilation of the rebel cavalry. We marched when and where we pleased; we were always the attacking party, and always successful." A contrary view has been published by historian Eric J. Wittenberg, who notes that of four major strategic raids (Richmond, Trevilian, Wilson-Kautz, and First Deep Bottom) and thirteen major cavalry engagements of the Overland and Richmond–Petersburg

The Greater Richmond Region, also known as the Richmond metropolitan area or Central Virginia, is a region and metropolitan area in the U.S. state of Virginia, centered on Richmond. The U.S. Office of Management and Budget (OMB) defines the area ...

campaigns, only Yellow Tavern can be considered a Union victory, with Haw's Shop, Trevilian Station, Meadow Bridge, Samaria Church, and Wilson-Kautz defeats in which some of Sheridan's forces barely avoided destruction.

Army of the Shenandoah

Throughout the war, the Confederacy sent armies out of Virginia through the

Throughout the war, the Confederacy sent armies out of Virginia through the Shenandoah Valley

The Shenandoah Valley () is a geographic valley and cultural region of western Virginia and the eastern panhandle of West Virginia in the United States. The Valley is bounded to the east by the Blue Ridge Mountains, to the west by the east ...

to invade Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It borders the states of Virginia to its south, West Virginia to its west, Pennsylvania to its north, and Delaware to its east ...

and Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania, officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a U.S. state, state spanning the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern United States, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes region, Great Lakes regions o ...

and threaten Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from Virginia, and shares land borders with ...

Lt. Gen. Jubal Early

Jubal Anderson Early (November 3, 1816 – March 2, 1894) was an American lawyer, politician and military officer who served in the Confederate States Army during the Civil War. Trained at the United States Military Academy, Early resigned his ...

, following the same pattern in the Valley Campaigns of 1864, and hoping to distract Grant from the Siege of Petersburg

The Richmond–Petersburg campaign was a series of battles around Petersburg, Virginia, fought from June 9, 1864, to March 25, 1865, during the American Civil War. Although it is more popularly known as the siege of Petersburg, it was not a c ...

, attacked Union forces near Washington and raided several towns in Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania, officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a U.S. state, state spanning the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern United States, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes region, Great Lakes regions o ...

. Grant, reacting to the political commotion caused by the invasion, organized the Middle Military Division

The Middle Military Division was an organization of the Union Army during the American Civil War, responsible for operations around the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia and the Valley Campaigns of 1864.

In the summer of 1864, Confederate General ...

, whose field troops were known as the Army of the Shenandoah. He considered various candidates for command, including George Meade, William B. Franklin, and David Hunter

David Hunter (July 21, 1802 – February 2, 1886) was an American military officer. He served as a Union general during the American Civil War. He achieved notability for his unauthorized 1862 order (immediately rescinded) emancipating slaves ...

, with the latter two intended for the military division while Sheridan would command the army. All of these choices were rejected by either Grant or the War Department and, over the objection of Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of the ...

Edwin Stanton

Edwin McMasters Stanton (December 19, 1814December 24, 1869) was an American lawyer and politician who served as U.S. Secretary of War, U.S. secretary of war under the Lincoln Administration during most of the American Civil War. Stanton's manag ...

, who believed him to be too young for such a high post, Sheridan took command in both roles at Harpers Ferry

Harpers Ferry is a historic town in Jefferson County, West Virginia, United States. The population was 269 at the 2020 United States census. Situated at the confluence of the Potomac River, Potomac and Shenandoah River, Shenandoah Rivers in the ...

on August 7, 1864. His mission was not only to defeat Early's army and to close off the Northern invasion route, but to deny the Shenandoah Valley as a productive agricultural region to the Confederacy. Grant told Sheridan, "The people should be informed that so long as an army can subsist among them recurrences of these raids must be expected, and we are determined to stop them at all hazards. ... Give the enemy no rest ... Do all the damage to railroads and crops you can. Carry off stock of all descriptions, and negroes, so as to prevent further planting. If the war is to last another year, we want the Shenandoah Valley to remain a barren waste."

Sheridan got off to a slow start, needing time to organize and to react to reinforcements reaching Early; Grant ordered him not to launch an offensive "with the advantage against you." And yet Grant expressed frustration with Sheridan's lack of progress. The armies remained unengaged for over a month, causing political consternation in the North as the 1864 election drew near. The two generals conferred on September 16 at Charles Town and agreed that Sheridan would begin his attacks within four days.

On September 19, armed with intelligence about the dispositions and strength of Early's forces around Winchester provided by unionist sympathizer and Quaker teacher

Sheridan got off to a slow start, needing time to organize and to react to reinforcements reaching Early; Grant ordered him not to launch an offensive "with the advantage against you." And yet Grant expressed frustration with Sheridan's lack of progress. The armies remained unengaged for over a month, causing political consternation in the North as the 1864 election drew near. The two generals conferred on September 16 at Charles Town and agreed that Sheridan would begin his attacks within four days.

On September 19, armed with intelligence about the dispositions and strength of Early's forces around Winchester provided by unionist sympathizer and Quaker teacher Rebecca Wright

Rebecca Wright (5 December 1947, Springfield, Ohio – 29 January 2006, Chevy Chase, Maryland) was an American ballerina, teacher, choreographer and ballet school director.

Biography

Her background in gymnastics and tap dance was a pivotal influen ...

, Sheridan beat Early's much smaller army at Third Winchester and followed up on September 22 with a victory at Fisher's Hill. As Early attempted to regroup, Sheridan began the punitive operations of his mission, sending his cavalry as far south as Waynesboro to seize or destroy livestock and provisions, and to burn barns, mills, factories, and railroads. Sheridan's men did their work relentlessly and thoroughly, rendering over 400 square miles uninhabitable.

The destruction presaged the scorched-earth

A scorched-earth policy is a military strategy of destroying everything that allows an enemy military force to be able to fight a war, including the deprivation and destruction of water, food, humans, animals, plants and any kind of tools and i ...

tactics of Sherman's March to the Sea through Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the South Caucasus

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the southeastern United States

Georgia may also refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Georgia (name), a list of pe ...

, and were designed to deny the Confederacy an army base from which to operate and bring the effects of war home to the population supporting it. Residents referred to this widespread destruction as "The Burning", which remain controversial. Sheridan's troops told of the wanton attack in their letters home, calling themselves "barn burners" and "destroyers of homes". One soldier wrote to his family that he had personally set 60 private homes on fire and believed that "it was a hard looking sight to see the women and children turned out of doors at this season of the year" (winter). A Sergeant William T. Patterson wrote that "the whole country around is wrapped in flames, the heavens are aglow with the light thereof ... such mourning, such lamentations, such crying and pleading for mercy y defenseless women... I never saw or want to see again." The Confederates were not idle during this period and Sheridan's men were plagued by guerrilla

Guerrilla warfare is a form of unconventional warfare in which small groups of irregular military, such as rebels, Partisan (military), partisans, paramilitary personnel or armed civilians, which may include Children in the military, recruite ...

raids by partisan ranger Col. John S. Mosby.

Although Sheridan assumed that Jubal Early was effectively out of action and he considered withdrawing his army to rejoin Grant at Petersburg, Early received reinforcements and, on October 19 at Cedar Creek, launched a well-executed surprise attack while Sheridan was absent from his army, ten miles away at Winchester

Winchester (, ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city in Hampshire, England. The city lies at the heart of the wider City of Winchester, a local government Districts of England, district, at the western end of the South Downs N ...

. Hearing the distant sounds of artillery

Artillery consists of ranged weapons that launch Ammunition, munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during sieges, and l ...

, he rode aggressively to his command. He reached the battlefield about 10:30 a.m. and began to rally his men. Fortunately for Sheridan, Early's men were too occupied to take notice; they were hungry and exhausted and fell out to pillage the Union camps. Sheridan's actions are generally credited with saving the day, although Maj. Gen. Horatio G. Wright

Horatio Gouverneur Wright (March 6, 1820 – July 2, 1899) was an engineer and general in the Union Army during the American Civil War. He took command of the VI Corps in May 1864 following the death of General John Sedgwick. In this capacity, h ...

, commanding Sheridan's VI Corps 6 Corps, 6th Corps, Sixth Corps, or VI Corps may refer to:

France

* VI Cavalry Corps (Grande Armée), a cavalry formation of the Imperial French army during the Napoleonic Wars

* VI Corps (Grande Armée), a formation of the Imperial French army dur ...

, already rallied his men and stopped their retreat. Early had been dealt his most significant defeat, rendering his army almost incapable of future offensive action.

Sheridan received a personal letter of thanks from Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

and was promoted to major general in the regular army

A regular army is the official army of a state or country (the official armed forces), contrasting with irregular forces, such as volunteer irregular militias, private armies, mercenaries, etc. A regular army usually has the following:

* a ...

as of November 8, 1864, making him the fourth ranking general in the Army, after Grant, Sherman, and Meade. Grant wrote to Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of the ...

Edwin M. Stanton

Edwin McMasters Stanton (December 19, 1814December 24, 1869) was an American lawyer and politician who served as U.S. secretary of war under the Lincoln Administration during most of the American Civil War. Stanton's management helped organize ...

after he ordered a 100-gun salute to celebrate Sheridan's victory at Cedar Creek, "Turning what bid fair to be a disaster into glorious victory stamps Sheridan, what I have always thought him, one of the ablest of generals." A famous poem, ''Sheridan's Ride'', was written by Thomas Buchanan Read

Thomas Buchanan Read (March 12, 1822 – May 11, 1872) was an American poet and painter. His portraits

include many famous individuals including Robert Browning, Joseph Harrison Jr., William Henry Harrison, Abraham Lincoln, Henry Wadsworth Long ...

to commemorate the general's return to the battle. Sheridan reveled in the fame that Read's poem brought him, renaming his horse Rienzi to "Winchester", based on the poem's refrain, "Winchester, twenty miles away." The poem was widely used in Republican campaign efforts and some have credited Abraham Lincoln's margin of victory to it. Lincoln was pleased at Sheridan's performance as a commander, writing Sheridan and playfully confessing his reassessment of the relatively short officer, "When this peculiar war began, I thought a cavalryman should be six feet four inches, but I have changed my mind. Five foot four will do in a pinch."

Sheridan spent the next several months occupying Winchester

Winchester (, ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city in Hampshire, England. The city lies at the heart of the wider City of Winchester, a local government Districts of England, district, at the western end of the South Downs N ...

, and was the national military governor of the city after the previous six-month long occupation of his predecessor, national general Robert H. Milroy. He was occupied with light skirmishing and fighting guerrillas. Although Grant continued his exhortations for Sheridan to move south and break the Virginia Central Railroad

The Virginia Central Railroad was an early railroad in the U.S. state of Virginia that operated between 1850 and 1868 from Richmond westward for to Covington. Chartered in 1836 as the Louisa Railroad by the Virginia General Assembly, the railr ...

supplying Petersburg, Sheridan resisted. Wright's VI Corps returned to join Grant in November. Sheridan's remaining men, primarily cavalry and artillery, finally moved out of their winter quarters on February 27, 1865, and headed east.

Writing about Sheridan's occupation of Winchester, a resident wrote:

The orders from Gen. Grant were largely discretionary, interpreted as permitting Sheridan to either destroy the Virginia Central Railroad and the James River Canal

The James River and Kanawha Canal was a partially built canal in Virginia intended to facilitate shipments of passengers and freight by water between the western counties of Virginia and the coast. Ultimately its towpath became the roadbed for ...

, capture Lynchburg if practical, and then either join William T. Sherman in North Carolina or return to Winchester.

Appomattox Campaign

Sheridan interpreted Grant's orders liberally and instead of heading to

Sheridan interpreted Grant's orders liberally and instead of heading to North Carolina

North Carolina ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, South Carolina to the south, Georgia (U.S. stat ...

, in March 1865, he moved to rejoin the Army of the Potomac

The Army of the Potomac was the primary field army of the Union army in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was created in July 1861 shortly after the First Battle of Bull Run and was disbanded in June 1865 following the Battle of ...

at Petersburg. He wrote in his memoirs, "Feeling that the war was nearing its end, I desired my cavalry to be in at the death." His finest service of the Civil War was demonstrated during his relentless pursuit of Robert E. Lee

Robert Edward Lee (January 19, 1807 – October 12, 1870) was a general officers in the Confederate States Army, Confederate general during the American Civil War, who was appointed the General in Chief of the Armies of the Confederate ...

's Army, effectively managing the most crucial aspects of the Appomattox Campaign for Grant.

On the way to Petersburg, at the Battle of Waynesboro, on March 2, 1865, he trapped the remainder of Early's army. and 1,500 soldiers surrendered. On April 1, he cut off General Lee's lines of support at Five Forks, forcing Lee to evacuate Petersburg. During the battle, he ruined the military career of Maj. Gen. Gouverneur K. Warren by removing him from command of the V Corps 5th Corps, Fifth Corps, or V Corps may refer to:

France

* 5th Army Corps (France)

* V Cavalry Corps (Grande Armée), a cavalry unit of the Imperial French Army during the Napoleonic Wars

* V Corps (Grande Armée), a unit of the Imperial French Arm ...

under circumstances that a court of inquiry later determined were unjustified. President Rutherford B. Hayes

Rutherford Birchard Hayes (; October 4, 1822 – January 17, 1893) was the 19th president of the United States, serving from 1877 to 1881.

Hayes served as Cincinnati's city solicitor from 1858 to 1861. He was a staunch Abolitionism in the Un ...

ordered a court of inquiry that convened in 1879 and, after hearing testimony from dozens of witnesses over 100 days, found that Sheridan's relief of Warren had been unjustified. Unfortunately for Warren, these results were not published until after his death.

Sheridan's aggressive and well-executed performance at the Battle of Sayler's Creek

A battle is an occurrence of combat in warfare between opposing military units of any number or size. A war usually consists of multiple battles. In general, a battle is a military engagement that is well defined in duration, area, and force c ...

on April 6 effectively sealed the fate of Lee's army, capturing over 20% of his remaining men. President Lincoln sent Grant a telegram on April 7: "Gen. Sheridan says 'If the thing is pressed I think that Lee will surrender.' Let the thing be pressed." At Appomattox Court House, on April 9, 1865, Sheridan blocked Lee's escape, forcing the surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia

The Army of Northern Virginia was a field army of the Confederate States Army in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was also the primary command structure of the Department of Northern Virginia. It was most often arrayed agains ...

later that day. Grant summed up Little Phil's performance in these final days, saying, "I believe General Sheridan has no superior as a general, either living or dead, and perhaps not an equal."

Reconstruction

After Gen. Lee's surrender, and that of Gen.

After Gen. Lee's surrender, and that of Gen. Joseph E. Johnston

Joseph Eggleston Johnston (February 3, 1807 – March 21, 1891) was an American military officer who served in the United States Army during the Mexican–American War (1846–1848) and the Seminole Wars. After Virginia declared secession from ...

in North Carolina, the only significant Confederate field force remaining was in Texas under Gen. Edmund Kirby Smith

Edmund Kirby Smith (May 16, 1824March 28, 1893) was a General officers in the Confederate States Army, Confederate States Army Four-star rank, general, who oversaw the Trans-Mississippi Department (comprising Arkansas, Missouri, Texas, western L ...

. Sheridan was supposed to lead troops in the Grand Review of the Armies

The Grand Review of the Armies was a military procession and celebration in the national capital city of Washington, D.C., on May 23–24, 1865, following the Union victory in the American Civil War (1861–1865). Elements of the Union Army in th ...

in Washington, D.C., but Grant appointed him commander of the Military District of the Southwest on May 17, 1865 six days before the parade, with orders to defeat Smith without delay and restore Texas and Louisiana to Union control. However, Smith surrendered before Sheridan reached New Orleans

New Orleans (commonly known as NOLA or The Big Easy among other nicknames) is a Consolidated city-county, consolidated city-parish located along the Mississippi River in the U.S. state of Louisiana. With a population of 383,997 at the 2020 ...

.

Grant was also concerned about the situation in neighboring Mexico, where 40,000 French soldiers propped up the puppet regime of Austrian Archduke Maximilian

Maximilian or Maximillian (Maximiliaan in Dutch and Maximilien in French) is a male name.

The name "Max" is considered a shortening of "Maximilian" as well as of several other names.

List of people

Monarchs

*Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor (1 ...

. He gave Sheridan permission to gather a large Texas occupation force. Sheridan assembled 50,000 men in three corps, quickly occupied Texas coastal cities, spread inland, and began to patrol the Mexico–United States border

The international border separating Mexico and the United States extends from the Pacific Ocean in the west to the Gulf of Mexico in the east. The border traverses a variety of terrains, ranging from urban areas to deserts. It is the List of ...

. The Army's presence, U.S. political pressure, and the growing resistance of Benito Juárez

Benito Pablo Juárez García (; 21 March 1806 – 18 July 1872) was a Mexican politician, military commander, and lawyer who served as the 26th president of Mexico from 1858 until his death in office in 1872. A Zapotec peoples, Zapotec, he w ...

induced the French to abandon their claims against Mexico. Napoleon III

Napoleon III (Charles-Louis Napoléon Bonaparte; 20 April 18089 January 1873) was President of France from 1848 to 1852 and then Emperor of the French from 1852 until his deposition in 1870. He was the first president, second emperor, and last ...

announced a staged withdrawal of French troops to be completed in November 1867. In light of growing opposition at home and concern with the rise of German military prowess, Napoleon III stepped up the French withdrawal, which was completed by March 12, 1867. By June 19 of that year, Mexico's republican army had captured, tried, and executed Maximilian. Sheridan later admitted in his memoirs that he had supplied arms and ammunition to Juárez's forces: "... which we left at convenient places on our side of the river to fall into their hands".

On July 30, 1866, while Sheridan was in Texas, a white mob broke up the state constitutional convention in New Orleans

New Orleans (commonly known as NOLA or The Big Easy among other nicknames) is a Consolidated city-county, consolidated city-parish located along the Mississippi River in the U.S. state of Louisiana. With a population of 383,997 at the 2020 ...

, killing 34 blacks. Shortly after Sheridan returned, he wired Grant, "The more information I obtain of the affair of the 30th in this city the more revolting it becomes. It was no riot; it was an absolute massacre." In March 1867, with Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*''Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Union ...

barely started, Sheridan was appointed military governor of the Fifth Military District

The Fifth Military District of the U.S. Army was one of five temporary administrative units of the U.S. War Department that existed in the American South from 1867 to 1870. The district was stipulated by the Reconstruction Acts during the Recons ...

(Texas and Louisiana). He severely limited voter registration for former Confederates and ruled that only registered voters, including black men, were eligible to serve on juries. Furthermore, an inquiry into the deadly New Orleans riot

The New Orleans massacre of 1866 occurred on July 30, when a peaceful demonstration of mostly Black Freedmen was set upon by a mob of white rioters, many of whom had been soldiers of the recently defeated Confederate States of America, leading ...

of 1866 implicated numerous local officials; Sheridan dismissed the mayor of New Orleans, the Louisiana attorney general, and a district judge. Following widespread anti-segregation protests in New Orleans, railroad company leaders met with Sheridan to try to get him to support their efforts to maintain the segregated "star car" system. He rejected their requests, thereby forcing them to desegregate New Orleans street cars. He later removed Louisiana Governor James M. Wells

James Madison Wells (January 7, 1808February 28, 1899) was a planter, lawyer, and politician who became the List of Governors of Louisiana, 20th Governor of Louisiana during Reconstruction Era, Reconstruction. Although a slave owner, Wells opp ...

, accusing him of being "a political trickster and a dishonest man". He also dismissed Texas Governor James W. Throckmorton

James Webb Throckmorton (February 1, 1825April 21, 1894) was an American politician who served as the 12th governor of Texas from 1866 to 1867 during the early days of Reconstruction. He was a United States Congressman from Texas from 1875 to 1 ...

, a former Confederate, for being an "impediment to the reconstruction of the State", replacing him with the Republican who had lost to him in the previous election Elisha M. Pease. Sheridan had been feuding with President Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808July 31, 1875) was the 17th president of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. The 16th vice president, he assumed the presidency following the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was a South ...

for months over interpretations of the Military Reconstruction Acts and voting rights issues, and within a month of the second firing, the president removed Sheridan, stating to an outraged Gen. Grant that, "His rule has, in fact, been one of absolute tyranny, without references to the principles of our government or the nature of our free institutions."

Sheridan was not popular in Texas, and he did not have much appreciation for Texas, either. In 1866, he quipped that, "If I owned Texas and Hell, I would rent Texas and live in Hell."

During the

During the Grant administration

Ulysses S. Grant's tenure as the 18th president of the United States began on March 4, 1869, and ended on March 4, 1877. Grant, a Republican Party (US), Republican, took office after winning the 1868 United States presidential election, 1868 e ...

, while Sheridan was assigned to duty in the West

West is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from east and is the direction in which the Sun sets on the Earth.

Etymology

The word "west" is a Germanic word passed into some Romance langu ...

, he was sent to Louisiana on two additional occasions to deal with problems that lingered in Reconstruction. In January 1875, federal troops intervened in the Louisiana Legislature following attempts by the Democrats to seize control of disputed seats. Sheridan supported Republican governor William P. Kellogg, who won the 1872 gubernatorial election, and declared that the Democratic opponents of the Republican regime who used violence to overcome legitimate electoral results were "banditti" who should be subjected to military tribunals and loss of their habeas corpus

''Habeas corpus'' (; from Medieval Latin, ) is a legal procedure invoking the jurisdiction of a court to review the unlawful detention or imprisonment of an individual, and request the individual's custodian (usually a prison official) to ...

rights. The Grant administration backed down after an enormous public outcry. A headline in the ''New York World

The ''New York World'' was a newspaper published in New York City from 1860 to 1931. The paper played a major role in the history of American newspapers as a leading national voice of the Democratic Party. From 1883 to 1911 under publisher Jo ...

'' shrieked, "Tyranny! A Sovereign State Murdered!" In 1876, Sheridan was sent to New Orleans to command troops keeping the peace in the aftermath of the disputed 1876 presidential election.

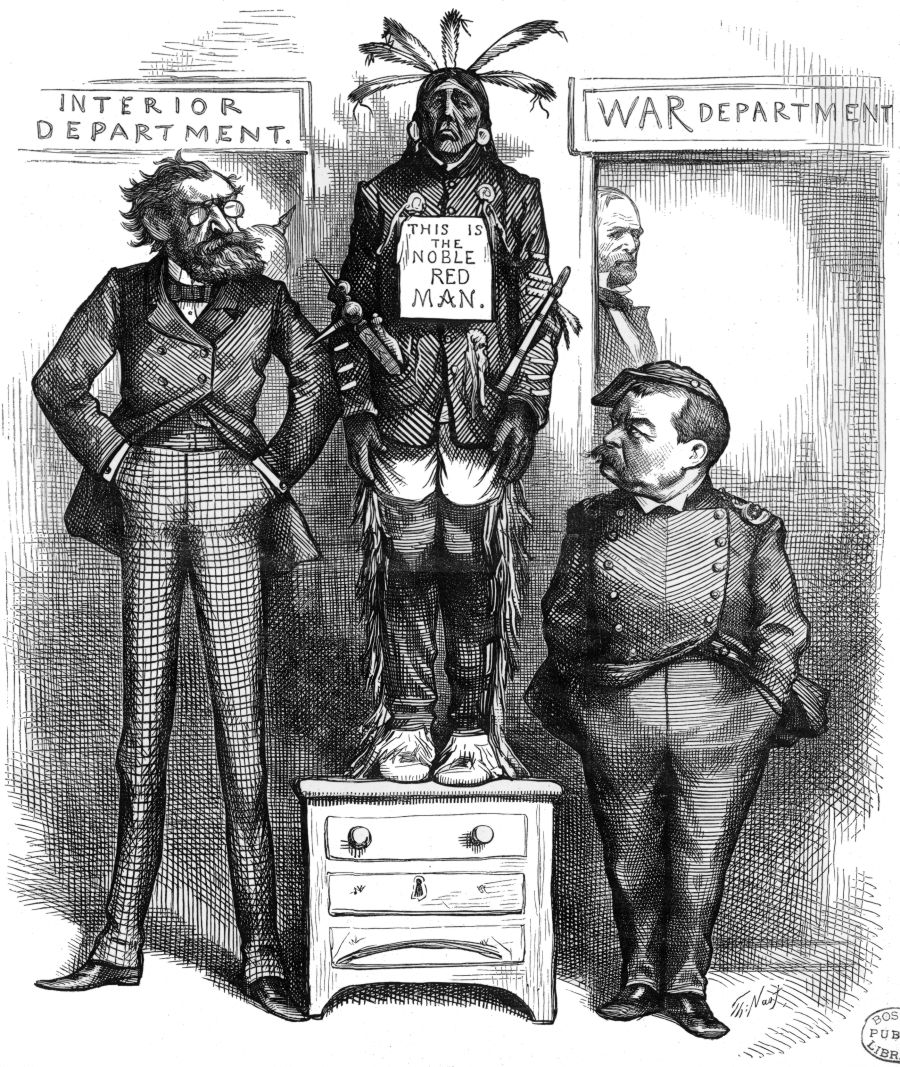

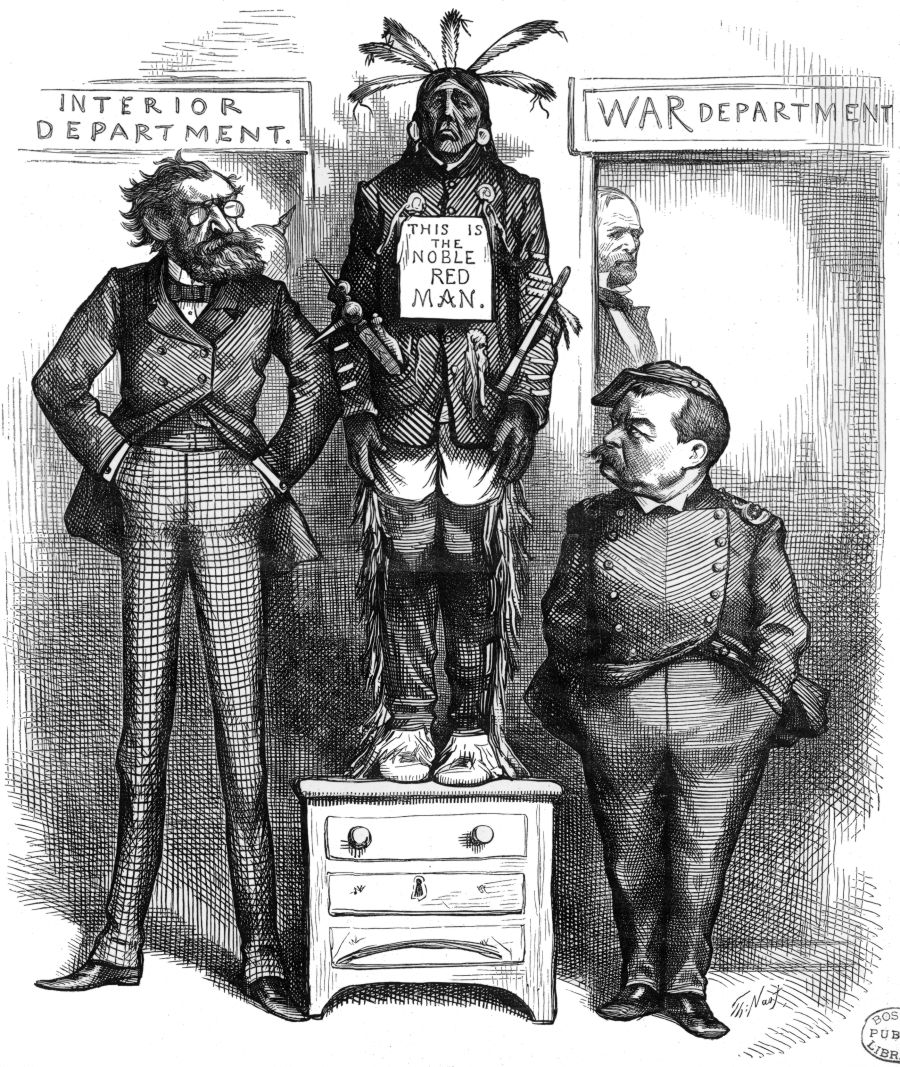

Indian Wars

In September 1866, Sheridan was assigned to

In September 1866, Sheridan was assigned to Fort Martin Scott

Fort Martin Scott is a restored United States Army outpost near Fredericksburg in the Texas Hill Country, United States, that was active from December 5, 1848, until April, 1853. It was part of a line of frontier forts established to protect tr ...

near Fredericksburg, Texas

Fredericksburg () is a city in and the county seat of Gillespie County, Texas, United States. As of the 2020 United States census, 2020 Census, this city had a population of 10,875.

Fredericksburg was founded in 1846 and named after Prince Frede ...

, to administer the formerly Confederate area. While there, he spent three months subduing marauding Indians in the Texas Hill Country

The Texas Hill Country is a geographic region of Central and South Texas, forming the southeast part of the Edwards Plateau. Given its location, climate, terrain, and vegetation, the Hill Country can be considered the border between the Ame ...

.

At this time, President Johnson was dissatisfied with the way Republican Army Generals were administering Reconstruction in the post-war Southern states and sought to replace them with Democratic ones more in tune with the (formerly Confederate) White populations committed to instituting Jim Crow laws

The Jim Crow laws were U.S. state, state and local laws introduced in the Southern United States in the late 19th and early 20th centuries that enforced Racial segregation in the United States, racial segregation, "Jim Crow (character), Ji ...

.

Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock

Winfield Scott Hancock (February 14, 1824 – February 9, 1886) was a United States Army officer and the Democratic nominee for President of the United States in 1880. He served with distinction in the Army for four decades, including service ...

had been assigned to the Department of the Missouri

The Department of the Missouri was a command echelon of the United States Army in the 19th century and a sub division of the Military Division of the Missouri that functioned through the Indian Wars.

History

Background

Following the successful ...

, an administrative area of over 1,000,000 square miles, encompassing land between the Mississippi River and the Rocky Mountains, and from Kansas north, but had mishandled his campaign mistreating the Plains Indians, primarily Sioux

The Sioux or Oceti Sakowin ( ; Dakota/ Lakota: ) are groups of Native American tribes and First Nations people from the Great Plains of North America. The Sioux have two major linguistic divisions: the Dakota and Lakota peoples (translati ...

and Cheyenne

The Cheyenne ( ) are an Indigenous people of the Great Plains. The Cheyenne comprise two Native American tribes, the Só'taeo'o or Só'taétaneo'o (more commonly spelled as Suhtai or Sutaio) and the (also spelled Tsitsistas, The term for th ...

, resulting in retaliatorily raids that attacked mail coaches

The mail or post is a system for physically transporting postcards, letters, and parcels. A postal service can be private or public, though many governments place restrictions on private systems. Since the mid-19th century, national postal syst ...