Early life and education

A military brat, Douglas MacArthur was born 26 January 1880, at Little Rock Barracks inEducation

MacArthur's time on the frontier ended in July 1889 when the family moved to Washington, D.C., where he attended the Force Public School. His father was posted to San Antonio, Texas, in September 1893. While there MacArthur attended the West Texas Military Academy, where he was awarded the gold medal for "scholarship and deportment". He played on the school tennis team, quarterback on the school football team, and shortstop on its baseball team. He was named

MacArthur's time on the frontier ended in July 1889 when the family moved to Washington, D.C., where he attended the Force Public School. His father was posted to San Antonio, Texas, in September 1893. While there MacArthur attended the West Texas Military Academy, where he was awarded the gold medal for "scholarship and deportment". He played on the school tennis team, quarterback on the school football team, and shortstop on its baseball team. He was named Junior officer

MacArthur spent his graduation furlough with his parents at Fort Mason, California, where his father, now a major general, was commanding the Department of the Pacific. Afterward, he joined the 3rd Engineer Battalion, which departed for the Philippines in October 1903. MacArthur was sent to In October 1905, MacArthur received orders to proceed to Tokyo for appointment as aide-de-camp to his father. A man who knew the MacArthurs at this time wrote that "Arthur MacArthur was the most flamboyantly egotistical man I had ever seen, until I met his son." They inspected Japanese military bases at

In October 1905, MacArthur received orders to proceed to Tokyo for appointment as aide-de-camp to his father. A man who knew the MacArthurs at this time wrote that "Arthur MacArthur was the most flamboyantly egotistical man I had ever seen, until I met his son." They inspected Japanese military bases at Veracruz expedition

On 21 April 1914, PresidentWorld War I

Rainbow Division

MacArthur returned to the War Department, where he was promoted toLunéville-Baccarat Defensive sector

The 42nd Division entered the line in the quiet Lunéville sector in February 1918. On 26 February, MacArthur and Captain Thomas T. Handy accompanied a French Trench raiding, trench raid in which MacArthur assisted in the capture of a number of German prisoners. The commander of the 7e corps d'armée (France), French VII Corps, Major General Georges de Bazelaire, decorated MacArthur with the ''Croix de Guerre 1914–1918 (France), Croix de Guerre''. This was the first ever ''Croix de Guerre'' awarded to a member of the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF). Menoher recommended MacArthur for a Silver Star, which he later received. The Silver Star Medal was not instituted until 8 August 1932, but small Silver Citation Stars were authorized to be worn on the campaign ribbons of those cited in orders for gallantry, similar to the British Mentioned in dispatches, mention in despatches. When the Silver Star Medal was instituted, it was retroactively awarded to those who had been awarded Silver Citation Stars. On 9 March, the 42nd Division launched three raids of its own on German trenches in the Salient du Feys. MacArthur accompanied a company of the 168th Infantry Regiment (United States), 168th Infantry. This time, his leadership was rewarded with the Distinguished Service Cross (DSC). A few days later, MacArthur, who was strict about his men carrying their WWI gas mask, gas masks but often neglected to bring his own, was gassed. He recovered in time to show Secretary Baker around the area on 19 March.Champagne-Marne offensive

Upon the recommendation of Menoher, MacArthur was awarded his first "star" when he was promoted to brigadier general on 26 June. At the age of just thirty-eight, this made him, at the time, the youngest general in the AEF. This would remain the case until October when two other men, Lesley J. McNair and Pelham D. Glassford, both being thirty-five, also received promotion to brigadier generals. Around the same time, the 42nd Division was shifted to Châlons-en-Champagne to oppose the impending German Second Battle of the Marne, Champagne-Marne offensive. ''Général d'Armée'' Henri Gouraud (French Army officer), Henri Gouraud of the Fourth Army (France), French Fourth Army elected to meet the attack with a defense in depth, holding the front-line area as thinly as possible and meeting the German attack on his second line of defense. His plan succeeded, and MacArthur was awarded a second Silver Star. The 42nd Division participated in the subsequent Allied counter-offensive, and MacArthur was awarded a third Silver Star on 29 July. Two days later, Menoher relieved the fifty-eight-year-old Brigadier General Robert A. Brown of the 84th Infantry Brigade (which consisted of the 167th Infantry Regiment (United States), 167th and 168th Infantry Regiment (United States), 168th Infantry Regiments and the 151st Machine Gun Battalion) of his command and replaced him with MacArthur. Hearing reports that the enemy had withdrawn, MacArthur went forward on 2 August to see for himself. He later wrote: MacArthur reported back to Menoher and Major General Hunter Liggett, the commander of I Corps (United States), I Corps (under whose command the 42nd Division fell), that the Germans had indeed withdrawn, and was awarded a fourth Silver Star. He was also awarded a second ''Croix de guerre'' and made a ''commandeur'' of the ''Légion d'honneur''. MacArthur's leadership during the Champagne-Marne offensive and counter-offensive campaigns was noted by General Gouraud when he said MacArthur was "one of the finest and bravest officers I have ever served with."Battle of Saint-Mihiel and Meuse-Argonne offensive

The 42nd Division earned a few weeks rest, returning to the line for the Battle of Saint-Mihiel on 12 September 1918. The Allied advance proceeded rapidly, and MacArthur was awarded a fifth Silver Star for his leadership of the 84th Infantry Brigade. In his later life he recalled: He received a sixth Silver Star for his participation in a raid on the night of 25–26 September. The 42nd Division was relieved on the night of 30 September and moved to the Forest of Argonne, Argonne sector where it relieved the 1st Infantry Division (United States), 1st Division on the night of 11 October. On a reconnaissance the next day, MacArthur was gassed again, earning a second Wound Chevron. The 42nd Division's participation in the Meuse–Argonne offensive began on 14 October when it attacked with both brigades. That evening, a conference was called to discuss the attack, during which Major General Charles Pelot Summerall, Charles P. Summerall, commander of V Corps (United States), V Corps, telephoned and demanded that Châtillon-sous-les-Côtes, Châtillon be taken by 18:00 the next evening. An aerial photograph had been obtained that showed a gap in the German barbed wire to the northeast of Châtillon. Lieutenant Colonel Walter E. Bare—the commander of the 167th Infantry Regiment (United States), 167th Infantry—proposed an attack from that direction, covered by a machine-gun barrage. MacArthur adopted this plan. He was wounded, but not severely, while leading a reconnaissance patrol into no man's land at night to confirm the existence of the gap in the barbed wire. As he mentioned to William Addleman Ganoe a few years later, the Germans saw them and shot at MacArthur and the squad with artillery and machine guns. MacArthur was the sole survivor of the patrol, claiming it was a miracle that he survived. He confirmed that there was indeed an enormous, exposed gap in that area due to the lack of enemy gunfire coming from that area. Summerall nominated MacArthur for the Medal of Honor and promotion to major general, but he received neither. Instead, he was awarded a second Distinguished Service Cross. The 42nd Division returned to the line for the last time on the night of 4–5 November 1918. In the final advance on Sedan, Ardennes, Sedan. MacArthur later wrote that this operation "narrowly missed being one of the great tragedies of American history". An order to disregard unit boundaries led to units crossing into each other's zones. In the resulting chaos, MacArthur was taken prisoner by men of the 1st Division, who mistook him for a German general. This would be soon resolved by the removal of his hat and long scarf that he wore. His performance in the attack on the Meuse (river), Meuse heights led to his being awarded a seventh Silver Star. On 10 November, a day before the Armistice of 11 November 1918, armistice with Germany that ended the fighting, MacArthur was appointed commander of the 42nd Division, upon the recommendation of its outgoing commander, Menoher, who had left to take over the newly activated VI Corps (United States), VI Corps. For his service as the 42nd's chief of staff and commander of the 84th Infantry Brigade, he was later awarded the Distinguished Service Medal (U.S. Army), Army Distinguished Service Medal. His period in command of the 42nd Division was brief, for on 22 November he, like other brigadier generals, was replaced and returned to the 84th Infantry Brigade, with Major General Clement Flagler, his former battalion commander from Fort Leavenworth days before the war, instead taking command. It is possible that he may have retained command of the 42nd had he been promoted to major general (making him the youngest in the U.S. Army) but, with the sudden cessation of hostilities, that was unlikely. General Peyton C. March, the Chief of Staff of the United States Army, Army Chief of Staff (and close friend of Arthur MacArthur), "had put a block on promotions. There would be no more stars awarded while the War Department got to grips with demobilization. MacArthur returned to commanding the 84th Brigade". The 42nd Division was chosen to participate in the occupation of the Rhineland, occupying the Ahrweiler (district), Ahrweiler district. In April 1919, the 42nd Division entrained for Brest, France, Brest and Saint-Nazaire, where they boarded ships to return to the United States. MacArthur traveled on the ocean liner , which reached New York on 25 April 1919.Between the wars

Superintendent of the United States Military Academy

Shortly after the return home, MacArthur's 84th Brigade was demobilized at Camp Dodge, Iowa, on 12 May 1919. The following month, he became Superintendents of the United States Military Academy, Superintendent of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, which General March, "an acerbic, thin-lipped intellectual", felt had become out of date in many respects and was much in need of reform. Accepting the post, "one of the most prestigious in the army", also allowed MacArthur to retain his rank of brigadier general (which was only temporary and for the duration of the war), instead of being reduced to his Substantive rank#Types of rank, substantive rank of major like many of his contemporaries. When MacArthur moved into the superintendent's house with his mother, he became the youngest superintendent since Sylvanus Thayer in 1817. However, whereas Thayer had faced opposition from outside the army, MacArthur had to overcome resistance from graduates and the academic board.

MacArthur's vision of what was required of an officer came not just from his recent experience of combat in France, but also from that of the occupation of the Rhineland in Germany. The military government of the Rhineland had required the Army to deal with political, economic and social problems but he had found that many West Point graduates had little or no knowledge of fields outside of the military sciences. During the war, West Point had been reduced to little more than an officer candidate school, with five classes being graduated in two years. Cadet and staff morale was low and hazing "at an all-time peak of viciousness". MacArthur's first change turned out to be the easiest. Congress had set the length of the course at three years. MacArthur was able to get the four-year course restored.

During the debate over the length of the course, ''The New York Times'' brought up the issue of the cloistered and undemocratic nature of student life at West Point. Also, starting with Harvard University in 1869, civilian universities had begun grading students on academic performance alone, but West Point had retained the old "whole man" Definitions of education, concept of education. MacArthur sought to modernize the system, expanding the concept of military character to include bearing, leadership, efficiency and athletic performance. He formalized the hitherto unwritten Cadet Honor Code in 1922 when he formed the Cadet Honor Committee to review alleged code violations. Elected by the cadets themselves, it had no authority to punish, but acted as a kind of grand jury, reporting offenses to the commandant. MacArthur attempted to end hazing by using officers rather than upperclassmen to train the plebes.

Instead of the traditional summer camp at Fort Clinton, MacArthur had the cadets trained to use modern weapons by regular army sergeants at Fort Dix; they then marched back to West Point with full packs. He attempted to modernize the curriculum by adding liberal arts, government and economics courses, but encountered strong resistance from the academic board. In Military Art classes, the study of the campaigns of the American Civil War was replaced with the study of those of World War I. In History class, more emphasis was placed on the Far East. MacArthur expanded the sports program, increasing the number of intramural sports and requiring all cadets to participate. He allowed upper class cadets to leave the reservation, and sanctioned a cadet newspaper, ''The Brag'', forerunner of today's ''West Pointer''. He also permitted cadets to travel to watch their football team play, and gave them a monthly allowance of $5 (). Professors and alumni alike protested these radical moves. Most of MacArthur's West Point reforms were soon discarded but, in the ensuing years, his ideas became accepted and his innovations were gradually restored.

Shortly after the return home, MacArthur's 84th Brigade was demobilized at Camp Dodge, Iowa, on 12 May 1919. The following month, he became Superintendents of the United States Military Academy, Superintendent of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, which General March, "an acerbic, thin-lipped intellectual", felt had become out of date in many respects and was much in need of reform. Accepting the post, "one of the most prestigious in the army", also allowed MacArthur to retain his rank of brigadier general (which was only temporary and for the duration of the war), instead of being reduced to his Substantive rank#Types of rank, substantive rank of major like many of his contemporaries. When MacArthur moved into the superintendent's house with his mother, he became the youngest superintendent since Sylvanus Thayer in 1817. However, whereas Thayer had faced opposition from outside the army, MacArthur had to overcome resistance from graduates and the academic board.

MacArthur's vision of what was required of an officer came not just from his recent experience of combat in France, but also from that of the occupation of the Rhineland in Germany. The military government of the Rhineland had required the Army to deal with political, economic and social problems but he had found that many West Point graduates had little or no knowledge of fields outside of the military sciences. During the war, West Point had been reduced to little more than an officer candidate school, with five classes being graduated in two years. Cadet and staff morale was low and hazing "at an all-time peak of viciousness". MacArthur's first change turned out to be the easiest. Congress had set the length of the course at three years. MacArthur was able to get the four-year course restored.

During the debate over the length of the course, ''The New York Times'' brought up the issue of the cloistered and undemocratic nature of student life at West Point. Also, starting with Harvard University in 1869, civilian universities had begun grading students on academic performance alone, but West Point had retained the old "whole man" Definitions of education, concept of education. MacArthur sought to modernize the system, expanding the concept of military character to include bearing, leadership, efficiency and athletic performance. He formalized the hitherto unwritten Cadet Honor Code in 1922 when he formed the Cadet Honor Committee to review alleged code violations. Elected by the cadets themselves, it had no authority to punish, but acted as a kind of grand jury, reporting offenses to the commandant. MacArthur attempted to end hazing by using officers rather than upperclassmen to train the plebes.

Instead of the traditional summer camp at Fort Clinton, MacArthur had the cadets trained to use modern weapons by regular army sergeants at Fort Dix; they then marched back to West Point with full packs. He attempted to modernize the curriculum by adding liberal arts, government and economics courses, but encountered strong resistance from the academic board. In Military Art classes, the study of the campaigns of the American Civil War was replaced with the study of those of World War I. In History class, more emphasis was placed on the Far East. MacArthur expanded the sports program, increasing the number of intramural sports and requiring all cadets to participate. He allowed upper class cadets to leave the reservation, and sanctioned a cadet newspaper, ''The Brag'', forerunner of today's ''West Pointer''. He also permitted cadets to travel to watch their football team play, and gave them a monthly allowance of $5 (). Professors and alumni alike protested these radical moves. Most of MacArthur's West Point reforms were soon discarded but, in the ensuing years, his ideas became accepted and his innovations were gradually restored.

Army's youngest major general

MacArthur became romantically involved with socialite and multi-millionaire heiress Louise Cromwell Brooks. They were married at her family's villa in Palm Beach, Florida, on 14 February 1922. Rumors circulated that General Pershing, who had also courted Louise, had threatened to exile them to the Philippines if they were married. Pershing denied this as "all damn poppycock". More recently, Richard B. Frank has written that Pershing and Brooks had already "severed" their relationship by the time of MacArthur's transfer; Brooks was, however, "informal[ly]" engaged to a close aide of Pershing's (she broke off the relationship in order to accept MacArthur's proposal). Pershing's letter concerning MacArthur's transfer predated—by a few days—Brooks's and MacArthur's engagement announcement, though this did not dispel the newspaper gossip. In October 1922, MacArthur left West Point and sailed to the Philippines with Louise and her two children, Walter and Louise, to assume command of the Military District of Manila. MacArthur was fond of the children, and spent much of his free time with them. The Philippine–American War, revolts in the Philippines had been suppressed, the islands were peaceful now, and in the wake of the Washington Naval Treaty, the garrison was being reduced. MacArthur's friendships with Filipinos like Manuel Quezon offended some people. "The old idea of colonial exploitation", he later conceded, "still had its vigorous supporters." In February and March 1923 MacArthur returned to Washington to see his mother, who was ill from a heart ailment. She recovered, but it was the last time he saw his brother Arthur, who died suddenly from appendicitis in December 1923. In June 1923, MacArthur assumed command of the 23rd Infantry Brigade of the Philippine Division (United States), Philippine Division. On 7 July 1924, he was informed that a mutiny had broken out amongst the Philippine Scouts over grievances concerning pay and allowances. Over 200 were arrested and there were fears of an insurrection. MacArthur was able to calm the situation, but his subsequent efforts to improve the salaries of Filipino troops were frustrated by financial stringency and racial prejudice. On 17 January 1925, at the age of 44, he was promoted, becoming the Army's youngest major general. Returning to the U.S., MacArthur took command of the Corps area, IV Corps Area, based at Fort McPherson in Atlanta, Georgia, on 2 May 1925. However, he encountered southern prejudice because he was the son of a Union Army officer, and he requested to be relieved. A few months later, he assumed command of the III Corps area, based at Fort McHenry in Baltimore, Maryland. The transfer allowed MacArthur and Louise to move to her Rainbow Hill estate, near Garrison, Maryland. However, this relocation also led to what he later described as "one of the most distasteful orders I ever received": a direction to serve on the court-martial of Brigadier General Billy Mitchell. MacArthur was the youngest of the thirteen judges, none of whom had aviation experience. Three of them, including Summerall, the president of the court, were removed when defense challenges revealed bias against Mitchell. Despite MacArthur's claim that he had voted to acquit, Mitchell was found guilty as charged and convicted. MacArthur felt "that a senior officer should not be silenced for being at variance with his superiors in rank and with accepted doctrine". In 1927, MacArthur and Louise separated, and she moved to New York City, adopting as her residence the entire twenty-sixth floor of a Manhattan hotel. In August that year, William C. Prout—the president of the United States Olympic & Paralympic Committee, American Olympic Committee—died suddenly and the committee elected MacArthur as their new president. His main task was to prepare the United States at the 1928 Summer Olympics, U.S. team for the 1928 Summer Olympics in Amsterdam, where the Americans won the most medals. Upon returning to the U.S., MacArthur received orders to assume command of the Philippine Department. This time, the general travelled alone. On 17 June 1929, while he was in Manila, Louise obtained a divorce, ostensibly on the grounds of "failure to provide". In view of Louise's great wealth, William Manchester described this legal fiction as "preposterous". Both later acknowledged the real reason to be "incompatibility".Chief of Staff

By 1930, MacArthur was 50 and still the youngest and one of the best known of the U.S. Army's major generals. He left the Philippines on 19 September 1930 and for a brief time was in command of the IX Corps Area in San Francisco. On 21 November, he was sworn in as Chief of Staff of the United States Army, with the rank of general. While in Washington, he would ride home each day to have lunch with his mother. At his desk, he would wear a Japanese ceremonial kimono, cool himself with an oriental fan, and smoke cigarettes in a jeweled cigarette holder. In the evenings, he liked to read military history books. About this time, he began referring to himself as "MacArthur". He had already hired a public relations staff to promote his image with the American public, together with a set of ideas he was known to favor, namely: a belief that America needed a strongman leader to deal with the possibility that Communists might lead all of the great masses of unemployed into a revolution; that America's destiny was in the Asia-Pacific region; and a strong hostility to the British Empire. One contemporary described MacArthur as the greatest actor to ever serve as a U.S. Army general while another wrote that MacArthur had a court rather than a staff. The onset of the Great Depression prompted Congress to make cuts in the Army's personnel and budget. Some 53 bases were closed, but MacArthur managed to prevent attempts to reduce the number of regular officers from 12,000 to 10,000. MacArthur's main programs included the development of new mobilization plans. He grouped the nine corps areas together under four armies, which were charged with responsibility for training and frontier defense. He also negotiated the MacArthur-Pratt agreement with the Chief of Naval Operations, Admiral (United States), Admiral William V. Pratt. This was the first of a series of inter-service agreements over the following decades that defined the responsibilities of the different services with respect to aviation. This agreement placed coastal air defense under the Army. In March 1935, MacArthur activated a centralized air command, General Headquarters Air Force, under General Frank M. Andrews. By rapidly promoting Andrews from lieutenant colonel to brigadier general MacArthur supported Andrews' endorsement of the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress heavy bomber and the concept of long-range four-engine bombers. This was controversial at the time because most high-ranking Army generals and officials in the War Department supported twin-engine bombers like the Douglas B-18 Bolo heavy bomber. After MacArthur left his position as Army Chief of Staff in October 1935 his successor Malin Craig and War Secretary Harry Hines Woodring ordered a halt to research and development of the B-17 and in 1939 zero four-engine bombers were ordered by the War Department and instead hundreds of inferior B-18s and other twin-engine bombers were ordered and delivered to the Army. Andrews, thanks to MacArthur putting him in a position of power in 1935, was able to use bureaucratic loopholes to covertly order research and development of the B-17 to the point that when the Army and President Roosevelt finally endorsed four-engine bombers in 1940 B-17s were able to be immediately produced with no delays related to research and testing. The development of the M1 Garand rifle also happened during MacArthur's tenure as chief of staff. There was a debate over what caliber the M1 Garand should use. Many in the Army and Marine Corps wanted the new rifle to use the .276 Pedersen round. MacArthur personally intervened and ordered the M1 Garand to use the .30-06 Springfield round, which was what the M1903 Springfield used. This allowed the military to use the same ammunition for both the old standard service M1903 Springfield rifles and the future new standard service M1 Garand. The M1 Garand, chambered in .30-06 Springfield, was cleared for service in November 1935 and officially adopted in January 1936 as the new Army service rifle just a few months after MacArthur finished his tour of duty as chief of staff.Bonus Army

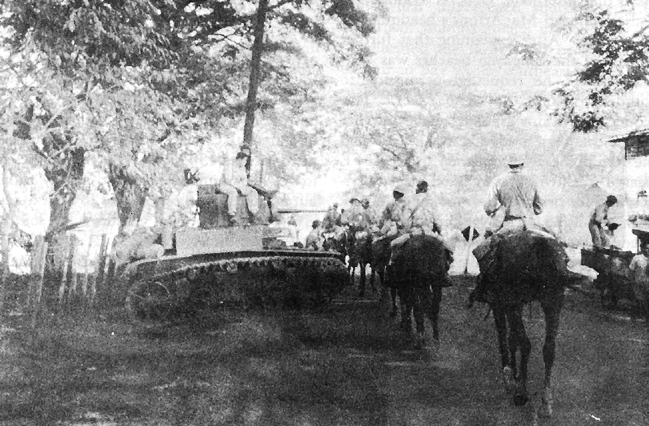

One of MacArthur's most controversial acts came in 1932, when the " On 28 July 1932, in a clash with the District police, two veterans were shot, and later died. President Herbert Hoover ordered MacArthur to "surround the affected area and clear it without delay". MacArthur brought up troops and tanks and, against the advice of Major Dwight D. Eisenhower, decided to accompany the troops, although he was not in charge of the operation. The troops advanced with bayonets and sabers drawn under a shower of bricks and rocks, but no shots were fired. In less than four hours, they cleared the Bonus Army's campground using tear gas. The gas canisters started a number of fires, causing the only death during the riots. While not as violent as other anti-riot operations, it was nevertheless a public relations disaster. However, the defeat of the "Bonus Army", while unpopular with the American people at large, did make MacArthur into the hero of the more right-wing elements in the Republican Party who believed that the general had saved America from a communist revolution in 1932.

In 1934, MacArthur sued journalists Drew Pearson (journalist), Drew Pearson and Robert S. Allen for defamation after they described his treatment of the Bonus marchers as "unwarranted, unnecessary, insubordinate, harsh and brutal". Also accused for proposing 19-gun salutes for friends, MacArthur asked for $750,000 (equivalent to $ in ) to compensate for the damage to his reputation. The journalists threatened to call Isabel Rosario Cooper as a witness. MacArthur had met Isabel while in the Philippines, and she had become his mistress. MacArthur was forced to settle out of court, secretly paying Pearson $15,000 ().

On 28 July 1932, in a clash with the District police, two veterans were shot, and later died. President Herbert Hoover ordered MacArthur to "surround the affected area and clear it without delay". MacArthur brought up troops and tanks and, against the advice of Major Dwight D. Eisenhower, decided to accompany the troops, although he was not in charge of the operation. The troops advanced with bayonets and sabers drawn under a shower of bricks and rocks, but no shots were fired. In less than four hours, they cleared the Bonus Army's campground using tear gas. The gas canisters started a number of fires, causing the only death during the riots. While not as violent as other anti-riot operations, it was nevertheless a public relations disaster. However, the defeat of the "Bonus Army", while unpopular with the American people at large, did make MacArthur into the hero of the more right-wing elements in the Republican Party who believed that the general had saved America from a communist revolution in 1932.

In 1934, MacArthur sued journalists Drew Pearson (journalist), Drew Pearson and Robert S. Allen for defamation after they described his treatment of the Bonus marchers as "unwarranted, unnecessary, insubordinate, harsh and brutal". Also accused for proposing 19-gun salutes for friends, MacArthur asked for $750,000 (equivalent to $ in ) to compensate for the damage to his reputation. The journalists threatened to call Isabel Rosario Cooper as a witness. MacArthur had met Isabel while in the Philippines, and she had become his mistress. MacArthur was forced to settle out of court, secretly paying Pearson $15,000 ().

New Deal

In the 1932 United States presidential election, 1932 presidential election, Herbert Hoover was defeated by Franklin D. Roosevelt. MacArthur and Roosevelt had worked together before World War I and had remained friends despite their political differences. MacArthur supported the New Deal through the Army's operation of the

In the 1932 United States presidential election, 1932 presidential election, Herbert Hoover was defeated by Franklin D. Roosevelt. MacArthur and Roosevelt had worked together before World War I and had remained friends despite their political differences. MacArthur supported the New Deal through the Army's operation of the Field Marshal of the Philippine Army

When the Commonwealth of the Philippines achieved semi-independent status in 1935, President of the Philippines Manuel Quezon asked MacArthur to supervise the creation of a Philippine Army. Quezon and MacArthur had been personal friends since the latter's Arthur MacArthur Jr., father had been Governor-General of the Philippines, 35 years earlier. With President Roosevelt's approval, MacArthur accepted the assignment. It was agreed that MacArthur would receive the rank of field marshal, with its salary and allowances, in addition to his major general's salary as Office of the Military Advisor to the Commonwealth Government of the Philippines, Military Advisor to the Commonwealth Government of the Philippines. This made him the best-paid soldier in the world. It would be his fifth tour in the Far East. MacArthur sailed from San Francisco on the in October 1935, accompanied by his mother and sister-in-law. He brought Eisenhower and Major James B. Ord along as his assistants. Another passenger on the ''President Hoover'' was Jean MacArthur, Jean Marie Faircloth, an unmarried 37-year-old socialite. Over the next two years, MacArthur and Faircloth were frequently seen together. His mother became gravely ill during the voyage and died in Manila on 3 December 1935. President Quezon officially conferred the title of field marshal on MacArthur in a ceremony at Malacañan Palace on 24 August 1936. Eisenhower recalled finding the ceremony "rather fantastic". He found it "pompous and rather ridiculous to be the field marshal of a virtually nonexisting army." Eisenhower learned later on that the field-marshalship had not been (as he had assumed) Quezon's idea. "I was surprised to learn from him that he had not initiated the idea at all; rather, Quezon said that MacArthur himself came up with the high-sounding title." (A persistent myth has pervaded the biographical literature, to the effect that MacArthur wore a "specially designed sharkskin uniform" at the 1936 ceremony to go with his new rank of Philippine Field Marshal. Richard Meixsel has debunked this story; in fact the special uniform was "the creation of a poorly informed journalist in 1937 who mistook a recently introduced U.S. Army white dress uniform for a distinctive field marshal's attire.")

The Philippine Army was formed from conscription. Training was conducted by a regular cadre, and the Philippine Military Academy was created along the lines of West Point to train officers. MacArthur and Eisenhower found that few of the training camps had been constructed and the first group of 20,000 trainees did not report until early 1937. Equipment and weapons were "more or less obsolete" American cast offs, and the budget was completely inadequate. MacArthur's requests for equipment fell on deaf ears, although MacArthur and his naval adviser, Lieutenant Colonel Sidney L. Huff, persuaded the Navy to initiate the development of the PT boat. Much hope was placed in the Philippine Army Air Corps, but the first squadron was not organized until 1939. Article XIX of the 1922 Washington Naval Treaty#Pacific bases, Washington Naval Treaty banned the construction of new fortifications or naval bases in all Pacific Ocean territories and colonies of the five signatories from 1923 to 1936. Also, military bases like at Clark Air Base, Clark and Fort Mills, Corregidor were not allowed to be expanded or modernized during that 13-year period. For example, the Malinta Tunnel#Construction, Malinta Tunnel on Corregidor was constructed from 1932 to 1934 with condemned TNT and without a single dollar from the U.S. government because of the treaty. This added to the numerous challenges facing MacArthur and Quezon.

In Manila, MacArthur was a member of the Freemasons. On 28 March 1936, he became a 32nd degree Scottish Rite Freemason.

MacArthur married Jean Faircloth in a civil ceremony on 30 April 1937. Their marriage produced a son, Arthur MacArthur IV, who was born in Manila on 21 February 1938. On 31 December 1937, MacArthur officially retired from the Army. He ceased to represent the U.S. as military adviser to the government, but remained as Quezon's adviser in a civilian capacity. Eisenhower returned to the U.S., and was replaced as MacArthur's chief of staff by Lieutenant Colonel Richard K. Sutherland, while Richard J. Marshall became deputy chief of staff.

President Quezon officially conferred the title of field marshal on MacArthur in a ceremony at Malacañan Palace on 24 August 1936. Eisenhower recalled finding the ceremony "rather fantastic". He found it "pompous and rather ridiculous to be the field marshal of a virtually nonexisting army." Eisenhower learned later on that the field-marshalship had not been (as he had assumed) Quezon's idea. "I was surprised to learn from him that he had not initiated the idea at all; rather, Quezon said that MacArthur himself came up with the high-sounding title." (A persistent myth has pervaded the biographical literature, to the effect that MacArthur wore a "specially designed sharkskin uniform" at the 1936 ceremony to go with his new rank of Philippine Field Marshal. Richard Meixsel has debunked this story; in fact the special uniform was "the creation of a poorly informed journalist in 1937 who mistook a recently introduced U.S. Army white dress uniform for a distinctive field marshal's attire.")

The Philippine Army was formed from conscription. Training was conducted by a regular cadre, and the Philippine Military Academy was created along the lines of West Point to train officers. MacArthur and Eisenhower found that few of the training camps had been constructed and the first group of 20,000 trainees did not report until early 1937. Equipment and weapons were "more or less obsolete" American cast offs, and the budget was completely inadequate. MacArthur's requests for equipment fell on deaf ears, although MacArthur and his naval adviser, Lieutenant Colonel Sidney L. Huff, persuaded the Navy to initiate the development of the PT boat. Much hope was placed in the Philippine Army Air Corps, but the first squadron was not organized until 1939. Article XIX of the 1922 Washington Naval Treaty#Pacific bases, Washington Naval Treaty banned the construction of new fortifications or naval bases in all Pacific Ocean territories and colonies of the five signatories from 1923 to 1936. Also, military bases like at Clark Air Base, Clark and Fort Mills, Corregidor were not allowed to be expanded or modernized during that 13-year period. For example, the Malinta Tunnel#Construction, Malinta Tunnel on Corregidor was constructed from 1932 to 1934 with condemned TNT and without a single dollar from the U.S. government because of the treaty. This added to the numerous challenges facing MacArthur and Quezon.

In Manila, MacArthur was a member of the Freemasons. On 28 March 1936, he became a 32nd degree Scottish Rite Freemason.

MacArthur married Jean Faircloth in a civil ceremony on 30 April 1937. Their marriage produced a son, Arthur MacArthur IV, who was born in Manila on 21 February 1938. On 31 December 1937, MacArthur officially retired from the Army. He ceased to represent the U.S. as military adviser to the government, but remained as Quezon's adviser in a civilian capacity. Eisenhower returned to the U.S., and was replaced as MacArthur's chief of staff by Lieutenant Colonel Richard K. Sutherland, while Richard J. Marshall became deputy chief of staff.

World War II

Philippines campaign (1941–1942)

Defense of the Philippines

On 26 July 1941, Roosevelt federalized the Philippine Army, recalled MacArthur to active duty in the U.S. Army as a major general, and named him commander of U.S. Army Forces in the Far East (USAFFE). MacArthur was promoted to lieutenant general the following day, and then to general on 20 December. On 31 July 1941, the Philippine Department had 22,000 troops assigned, 12,000 of whom were Philippine Scouts. The main component was the Philippine Division, under the command of Major General Jonathan M. Wainwright (general), Jonathan M. Wainwright. The initial American plan for the defense of the Philippines called for the main body of the troops to retreat to the Bataan peninsula in Manila Bay to hold out against the Japanese until a relief force could arrive. MacArthur changed this plan to one of attempting to hold all of Luzon and using Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress, B-17 Flying Fortresses to sink Japanese ships that approached the islands. MacArthur persuaded the decision-makers in Washington that his plans represented the best deterrent to prevent Japan from choosing war and of winning a war if worse came to worst. Between July and December 1941, the garrison received 8,500 reinforcements. After years of parsimony, much equipment was shipped. By November, a backlog of 1,100,000 shipping tons of equipment intended for the Philippines had accumulated in U.S. ports and depots awaiting vessels. In addition, the Navy intercept station in the islands, known as Station CAST, had an ultra-secret Purple (cipher machine), Purple cipher machine, which decrypted Japanese diplomatic messages, and partial codebooks for the latest JN-25, JN-25 naval code. Station CAST sent MacArthur its entire output, via Sutherland, the only officer on his staff authorized to see it. At 03:30 local time on 8 December 1941 (about 09:00 on 7 December in Hawaii), Sutherland learned of the attack on Pearl Harbor and informed MacArthur. At 05:30, the Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army, General George Marshall, ordered MacArthur to execute the existing war plan, Rainbow Five. This plan had been leaked to the American public by the Chicago Tribune three days prior, and the following day Germany had publicly ridiculed the plan. MacArthur did not follow Marshall's order. On three occasions, the commander of the Far East Air Force (United States), Far East Air Force, Major General Lewis H. Brereton, requested permission to attack Japanese bases in Formosa, in accordance with prewar intentions, but was denied by Sutherland; Brereton instead ordered his aircraft to fly defensive patrol patterns, looking for Japanese warships. Not until 11:00 did Brereton speak with MacArthur, and obtained permission to begin Rainbow Five. MacArthur later denied having the conversation. At 12:30, ten hours after the attack on Pearl Harbor, aircraft of Japan's Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service, 11th Air Fleet achieved complete tactical surprise when they attack on Clark Field, attacked Clark Field and the nearby fighter base at Iba Airfield, Iba Field, and destroyed or disabled 18 of Far East Air Force's 35 B-17s, caught on the ground refueling. Also destroyed were 53 of 107 Curtiss P-40 Warhawk, P-40s, 3 Seversky P-35, P-35s, and more than 25 other aircraft. Substantial damage was done to the bases, and casualties totaled 80 killed and 150 wounded. What was left of the Far East Air Force was all but destroyed over the next few days. MacArthur attempted to slow the Japanese advance with an initial defense against the Japanese landings. MacArthur's plan for holding all of Luzon against the Japanese collapsed, for it distributed the American-Filipino forces too thinly. However, he reconsidered his overconfidence in the ability of his Filipino troops after the Japanese landing force made a rapid advance following its landing at Lingayen Gulf on 21 December, and ordered a Battle of Bataan, retreat to Bataan. Within two days of the Japanese landing at Lingayen Gulf, MacArthur had reverted to the pre-July 1941 plan of attempting to hold only Bataan while waiting for a relief force to come. However, this switching of plans came at a grueling price; most of the American and some of the Filipino troops were able to retreat back to Bataan, but without most of their supplies, which were abandoned in the confusion. Manila was declared an open city at midnight on 24 December, without any consultation with Admiral Thomas C. Hart, commanding the United States Asiatic Fleet, Asiatic Fleet, forcing the Navy to destroy considerable amounts of valuable materiel. The Asiatic Fleet's performance during December 1941 was poor. Although the surface fleet was obsolete and was safely evacuated to try to defend the Dutch East Indies, more than two dozen modern submarines were assigned to Manila – Hart's strongest fighting force. The submariners were confident, but they were armed with the malfunctioning Mark 14 torpedo and were unable to sink a single Japanese warship during the invasion. MacArthur thought the Navy betrayed him. The submariners were ordered to abandon the Philippines by the end of December after ineffective attacks on the Japanese fleet, only returning to Corregidor to evacuate high-ranking politicians or officers for the rest of the campaign.

On the evening of 24 December, MacArthur moved his headquarters to the island fortress of Corregidor in Manila Bay arriving at 21:30, with his headquarters reporting to Washington as being open on the 25th. A series of air raids by the Japanese destroyed all the exposed structures on the island and USAFFE headquarters was moved into the Malinta Tunnel. In the first-ever air raid on Corregidor on 29 December, Japanese airplanes bombed all the buildings on Corregidor#Topside, Topside including MacArthur's house and the barracks. MacArthur's family ran into the air raid shelter while MacArthur went outside to the garden of the house with some soldiers to observe and count the number of bombers involved in the raid when bombs destroyed the home. One bomb struck only ten feet from MacArthur and the soldiers shielded him with their bodies and helmets. Filipino sergeant Domingo Adversario was awarded the Silver Star and Purple Heart for getting his hand wounded by the bomb and covering MacArthur's head with his own helmet, which was also hit by shrapnel. MacArthur was not wounded. Later, most of the headquarters moved to Bataan, leaving only the nucleus with MacArthur. The troops on Bataan knew that they had been written off but continued to fight. Some blamed Roosevelt and MacArthur for their predicament. A ballad sung to the tune of "The Battle Hymn of the Republic" called him "Dugout Doug". However, most clung to the belief that somehow MacArthur "would reach down and pull something out of his hat".

On 1 January 1942, MacArthur accepted $500,000 (equivalent to $ in ) from President Quezon of the Philippines as payment for his pre-war service. MacArthur's staff members also received payments: $75,000 for Sutherland, $45,000 for Richard Marshall, and $20,000 for Huff (equivalent to $, $, and $ in , respectively). Eisenhower—after being appointed Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force, Supreme Commander Allied Expeditionary Force (AEF)—was also offered money by Quezon, but declined. These payments were known only to a few in Manila and Washington, including President Roosevelt and Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson, until they were made public by historian Carol Petillo in 1979. While the payments had been fully legal, the revelation tarnished MacArthur's reputation.

MacArthur attempted to slow the Japanese advance with an initial defense against the Japanese landings. MacArthur's plan for holding all of Luzon against the Japanese collapsed, for it distributed the American-Filipino forces too thinly. However, he reconsidered his overconfidence in the ability of his Filipino troops after the Japanese landing force made a rapid advance following its landing at Lingayen Gulf on 21 December, and ordered a Battle of Bataan, retreat to Bataan. Within two days of the Japanese landing at Lingayen Gulf, MacArthur had reverted to the pre-July 1941 plan of attempting to hold only Bataan while waiting for a relief force to come. However, this switching of plans came at a grueling price; most of the American and some of the Filipino troops were able to retreat back to Bataan, but without most of their supplies, which were abandoned in the confusion. Manila was declared an open city at midnight on 24 December, without any consultation with Admiral Thomas C. Hart, commanding the United States Asiatic Fleet, Asiatic Fleet, forcing the Navy to destroy considerable amounts of valuable materiel. The Asiatic Fleet's performance during December 1941 was poor. Although the surface fleet was obsolete and was safely evacuated to try to defend the Dutch East Indies, more than two dozen modern submarines were assigned to Manila – Hart's strongest fighting force. The submariners were confident, but they were armed with the malfunctioning Mark 14 torpedo and were unable to sink a single Japanese warship during the invasion. MacArthur thought the Navy betrayed him. The submariners were ordered to abandon the Philippines by the end of December after ineffective attacks on the Japanese fleet, only returning to Corregidor to evacuate high-ranking politicians or officers for the rest of the campaign.

On the evening of 24 December, MacArthur moved his headquarters to the island fortress of Corregidor in Manila Bay arriving at 21:30, with his headquarters reporting to Washington as being open on the 25th. A series of air raids by the Japanese destroyed all the exposed structures on the island and USAFFE headquarters was moved into the Malinta Tunnel. In the first-ever air raid on Corregidor on 29 December, Japanese airplanes bombed all the buildings on Corregidor#Topside, Topside including MacArthur's house and the barracks. MacArthur's family ran into the air raid shelter while MacArthur went outside to the garden of the house with some soldiers to observe and count the number of bombers involved in the raid when bombs destroyed the home. One bomb struck only ten feet from MacArthur and the soldiers shielded him with their bodies and helmets. Filipino sergeant Domingo Adversario was awarded the Silver Star and Purple Heart for getting his hand wounded by the bomb and covering MacArthur's head with his own helmet, which was also hit by shrapnel. MacArthur was not wounded. Later, most of the headquarters moved to Bataan, leaving only the nucleus with MacArthur. The troops on Bataan knew that they had been written off but continued to fight. Some blamed Roosevelt and MacArthur for their predicament. A ballad sung to the tune of "The Battle Hymn of the Republic" called him "Dugout Doug". However, most clung to the belief that somehow MacArthur "would reach down and pull something out of his hat".

On 1 January 1942, MacArthur accepted $500,000 (equivalent to $ in ) from President Quezon of the Philippines as payment for his pre-war service. MacArthur's staff members also received payments: $75,000 for Sutherland, $45,000 for Richard Marshall, and $20,000 for Huff (equivalent to $, $, and $ in , respectively). Eisenhower—after being appointed Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force, Supreme Commander Allied Expeditionary Force (AEF)—was also offered money by Quezon, but declined. These payments were known only to a few in Manila and Washington, including President Roosevelt and Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson, until they were made public by historian Carol Petillo in 1979. While the payments had been fully legal, the revelation tarnished MacArthur's reputation.

Escape from the Philippines

In February 1942, as Japanese forces tightened their grip on the Philippines, President Roosevelt ordered MacArthur to relocate to Australia. On the night of 12 March 1942, MacArthur and a select group that included his wife Jean, son Arthur, Arthur's Cantonese people, Cantonese ''Amah (occupation), amah'', Loh Chui, and other members of his staff, including Sutherland, Richard Marshall and Huff, left Corregidor. They traveled in Patrol torpedo boat, PT boats through stormy seas patrolled by Japanese warships, and reached Del Monte Airfield on Mindanao, where B-17s picked them up, and flew them to Australia. MacArthur ultimately arrived in Melbourne by train on 21 March. His famous declaration, "I came through and I shall return", was first made at Terowie railway station in South Australia, on 20 March. Washington asked MacArthur to amend his promise to "We shall return". He ignored the request. Bataan surrendered on 9 April, and Corregidor on 6 May.Medal of Honor

George Marshall decided that MacArthur would be awarded the Medal of Honor, a decoration for which he had twice previously been nominated, "to offset any propaganda by the enemy directed at his leaving his command". Eisenhower pointed out that MacArthur had not actually performed any acts of valor as required by law, but Marshall cited the 1927 award of the medal to Charles Lindbergh as a precedent. Special legislation had been passed to authorize Lindbergh's medal, but while similar legislation was introduced authorizing the medal for MacArthur by Congressmen J. Parnell Thomas and James E. Van Zandt, Marshall felt strongly that a serving general should receive the medal from the president and the War Department, expressing that the recognition "would mean more" if the gallantry criteria were not waived by a bill of relief. Marshall ordered Sutherland to recommend the award and authored the citation himself. Ironically, this also meant that it violated the governing statute, as it could only be considered lawful so long as material requirements were waived by Congress, such as the unmet requirement to perform conspicuous gallantry "above and beyond the call of duty". Marshall admitted the defect to the secretary of war, acknowledging that "there is no specific act of General MacArthur's to justify the award of the Medal of Honor under a literal interpretation of the statutes". Similarly, when the Army's adjutant general reviewed the case in 1945, he determined that "authority for [MacArthur's] award is questionable under strict interpretation of regulations". MacArthur had been nominated for the award twice before and understood that it was for leadership and not gallantry. He expressed the sentiment that "this award was intended not so much for me personally as it is a recognition of the indomitable courage of the gallant army which it was my honor to command". At the age of 62 MacArthur was the oldest living active-duty Medal of Honor recipient in history and as a four-star general, he was the highest-ranked military servicemember to ever receive the Medal of Honor. Arthur and Douglas MacArthur thus became the first father and son to be awarded the Medal of Honor. They remained the only pair until 2001, when Theodore Roosevelt was posthumously awarded for his service during the Spanish–American War, Theodore Roosevelt Jr. having received one posthumously for his gallantry during the World War II Normandy invasion. MacArthur's citation, written by Marshall, read: As the symbol of the forces resisting the Japanese, MacArthur received many other accolades. The Native American tribes of the Southwest chose him as a "Chief of Chiefs", which he acknowledged as from "my oldest friends, the companions of my boyhood days on the Western frontier". He was touched when he was named Father of the Year for 1942, and wrote to the National Father's Day Committee that:New Guinea Campaign

General Headquarters

On 18 April 1942, MacArthur was appointed Supreme Allied Commander, Supreme Commander of Allied Forces in the South West Pacific Area (command), Southwest Pacific Area (SWPA). Lieutenant General George Brett (general), George Brett became Commander, Allied Air Forces, and Vice Admiral Herbert F. Leary became Commander, Allied Naval Forces. Since the bulk of land forces in the theater were Australian, George Marshall insisted an Australian be appointed as Commander, Allied Land Forces, and the job went to General Sir Thomas Blamey. Although predominantly Australian and American, MacArthur's command also included small numbers of personnel from the Netherlands East Indies, the United Kingdom, and other countries. MacArthur established a close relationship with the prime minister of Australia, John Curtin, and was probably the second most-powerful person in the country after the prime minister, although many Australians resented MacArthur as a foreign general who had been imposed upon them. MacArthur had little confidence in Brett's abilities as commander of Allied Air Forces, and in August 1942 selected Major General George C. Kenney to replace him. Kenney's application of air power in support of Blamey's troops would prove crucial. The staff of MacArthur's General Headquarters (GHQ) was built around the nucleus that had escaped from the Philippines with him, who became known as the "Bataan Gang". Though Roosevelt and George Marshall pressed for Dutch and Australian officers to be assigned to GHQ, the heads of all the staff divisions were American and such officers of other nationalities as were assigned served under them. Initially located in Melbourne, GHQ moved to Brisbane—the northernmost city in Australia with the necessary communications facilities—in July 1942, occupying the Australian Mutual Provident Society building (renamed after the war as MacArthur Chambers). MacArthur formed his own signals intelligence organization, known as the Central Bureau, from Australian intelligence units and American Cryptanalysis, cryptanalysts who had escaped from the Philippines. This unit forwarded Ultra (cryptography), Ultra information to MacArthur's Chief of Intelligence, Charles A. Willoughby, for analysis. After a press release revealed details of the Japanese naval dispositions during the Battle of the Coral Sea, at which a Japanese attempt to capture Port Moresby was turned back, Roosevelt ordered that censorship be imposed in Australia, and the Advisory War Council (Australia), Advisory War Council granted GHQ censorship authority over the Australian press. Australian newspapers were restricted to what was reported in the daily GHQ communiqué. Veteran correspondents considered the communiqués, which MacArthur drafted personally, "a total farce" and "Alice-in-Wonderland information handed out at high level".Papuan Campaign

Anticipating that the Japanese would strike at Port Moresby again, the garrison was strengthened and MacArthur ordered the establishment of new bases at Merauke and Milne Bay to cover its flanks. The Battle of Midway in June 1942 led to consideration of a limited offensive in the Pacific. MacArthur's proposal for an attack on the Japanese base at Rabaul met with objections from the Navy, which favored a less ambitious approach, and objected to an Army general being in command of what would be an Amphibious warfare, amphibious operation. The resulting compromise called for a three-stage advance. The first stage, the Battle of Tulagi and Gavutu–Tanambogo, seizure of the Tulagi area, would be conducted by the Pacific Ocean Areas (command), Pacific Ocean Areas, under Admiral Chester W. Nimitz. The later stages would be under MacArthur's command. The Japanese struck first, Invasion of Buna-Gona, landing at Buna in July, and at Battle of Milne Bay, Milne Bay in August. The Australians repulsed the Japanese at Milne Bay, but a series of defeats in the Kokoda Track campaign had a depressing effect back in Australia. On 30 August, MacArthur radioed Washington that unless action was taken, New Guinea Force would be overwhelmed. He sent Blamey to Port Moresby to take personal command. Having committed all available Australian troops, MacArthur decided to send American forces. The 32nd Infantry Division (United States), 32nd Infantry Division, a poorly trained National Guard division, was selected. A series of embarrassing reverses in the Battle of Buna–Gona led to outspoken criticism of the American troops by the Australians. MacArthur then ordered Lieutenant General Robert L. Eichelberger to assume command of the Americans, and "take Buna, or not come back alive".

MacArthur moved the advanced echelon of GHQ to Port Moresby on 6 November 1942. After Buna finally fell on 3 January 1943, MacArthur awarded the Distinguished Service Cross to twelve officers for "precise execution of operations". This use of the country's second highest award aroused resentment, because while some, like Eichelberger and George Alan Vasey, had fought in the field, others, like Sutherland and Willoughby, had not. For his part, MacArthur was awarded his third Distinguished Service Medal, and the Australian government had him appointed an honorary Order of the Bath, Knight Grand Cross of the British Order of the Bath.

The Japanese struck first, Invasion of Buna-Gona, landing at Buna in July, and at Battle of Milne Bay, Milne Bay in August. The Australians repulsed the Japanese at Milne Bay, but a series of defeats in the Kokoda Track campaign had a depressing effect back in Australia. On 30 August, MacArthur radioed Washington that unless action was taken, New Guinea Force would be overwhelmed. He sent Blamey to Port Moresby to take personal command. Having committed all available Australian troops, MacArthur decided to send American forces. The 32nd Infantry Division (United States), 32nd Infantry Division, a poorly trained National Guard division, was selected. A series of embarrassing reverses in the Battle of Buna–Gona led to outspoken criticism of the American troops by the Australians. MacArthur then ordered Lieutenant General Robert L. Eichelberger to assume command of the Americans, and "take Buna, or not come back alive".

MacArthur moved the advanced echelon of GHQ to Port Moresby on 6 November 1942. After Buna finally fell on 3 January 1943, MacArthur awarded the Distinguished Service Cross to twelve officers for "precise execution of operations". This use of the country's second highest award aroused resentment, because while some, like Eichelberger and George Alan Vasey, had fought in the field, others, like Sutherland and Willoughby, had not. For his part, MacArthur was awarded his third Distinguished Service Medal, and the Australian government had him appointed an honorary Order of the Bath, Knight Grand Cross of the British Order of the Bath.

New Guinea Campaign

At the Pacific Military Conference in March 1943, the Joint Chiefs of Staff approved MacArthur's plan for Operation Cartwheel, the advance on Rabaul. MacArthur explained his strategy:Philippines Campaign (1944–45)

Leyte

In July 1944, President Roosevelt summoned MacArthur to meet with him in Hawaii "to determine the phase of action against Japan". Nimitz made the case for attacking Formosa. MacArthur stressed America's moral obligation to liberate the Philippines and won Roosevelt's support. In September, Admiral William Halsey Jr.'s carriers made a series of air strikes on the Philippines. Opposition was feeble; Halsey concluded, incorrectly, that Leyte was "wide open" and possibly undefended, and recommended that projected operations be skipped in favor of an assault on Leyte. On 20 October 1944, troops of Krueger's Sixth Army Battle of Leyte, landed on Leyte, while MacArthur watched from the light cruiser . That afternoon he arrived on the beach. The advance had not progressed far; snipers were still active and the area was under sporadic mortar fire. When his whaleboat grounded in knee-deep water, MacArthur requested a landing craft, but the beachmaster was too busy to grant his request. MacArthur was compelled to wade ashore. In his prepared speech, he said:

Since Leyte was out of range of Kenney's land-based aircraft, MacArthur was dependent on carrier aircraft. Japanese air activity soon increased, with raids on Tacloban, where MacArthur decided to establish his headquarters, and on the fleet offshore. MacArthur enjoyed staying on ''Nashville''s bridge during air raids, although several bombs landed close by, and two nearby cruisers were hit. Over the next few days, the Japanese counterattacked in the Battle of Leyte Gulf, resulting in a near-disaster that MacArthur attributed to the command being divided between himself and Nimitz. Nor did the campaign ashore proceed smoothly. Heavy monsoonal rains disrupted the airbase construction program. Carrier aircraft proved to be no substitute for land-based aircraft, and the lack of air cover permitted the Japanese to pour troops into Leyte. Adverse weather and tough Japanese resistance slowed the American advance, resulting in a protracted campaign.

By the end of December, Krueger's headquarters estimated that 5,000 Japanese remained on Leyte, and on 26 December MacArthur issued a communiqué announcing that "the campaign can now be regarded as closed except for minor mopping up". Yet Eichelberger's Eighth United States Army, Eighth Army killed another 27,000 Japanese on Leyte before the campaign ended in May 1945. On 18 December 1944, MacArthur was promoted to the new five-star rank of General of the Army, placing him in the company of Marshall and followed by Eisenhower and Henry H. Arnold, Henry "Hap" Arnold, the only four men to achieve the rank in World War II. Including Omar Bradley who was promoted during the Korean War so as not to be outranked by MacArthur, they were the only five men to achieve the rank of General of the Army since the 5 August 1888 death of Philip Sheridan. MacArthur was senior to all but Marshall. The rank was created by an Act of Congress when Public Law s:Public Law 78-482, 78-482 was passed on 14 December 1944, This law allowed only 75% of pay and allowances to the grade for those on the retired list. as a temporary rank, subject to reversion to permanent rank six months after the end of the war. The temporary rank was then declared permanent 23 March 1946 by Public Law 333 of the 79th Congress, which also awarded full pay and allowances in the grade to those on the retired list.

On 20 October 1944, troops of Krueger's Sixth Army Battle of Leyte, landed on Leyte, while MacArthur watched from the light cruiser . That afternoon he arrived on the beach. The advance had not progressed far; snipers were still active and the area was under sporadic mortar fire. When his whaleboat grounded in knee-deep water, MacArthur requested a landing craft, but the beachmaster was too busy to grant his request. MacArthur was compelled to wade ashore. In his prepared speech, he said:

Since Leyte was out of range of Kenney's land-based aircraft, MacArthur was dependent on carrier aircraft. Japanese air activity soon increased, with raids on Tacloban, where MacArthur decided to establish his headquarters, and on the fleet offshore. MacArthur enjoyed staying on ''Nashville''s bridge during air raids, although several bombs landed close by, and two nearby cruisers were hit. Over the next few days, the Japanese counterattacked in the Battle of Leyte Gulf, resulting in a near-disaster that MacArthur attributed to the command being divided between himself and Nimitz. Nor did the campaign ashore proceed smoothly. Heavy monsoonal rains disrupted the airbase construction program. Carrier aircraft proved to be no substitute for land-based aircraft, and the lack of air cover permitted the Japanese to pour troops into Leyte. Adverse weather and tough Japanese resistance slowed the American advance, resulting in a protracted campaign.

By the end of December, Krueger's headquarters estimated that 5,000 Japanese remained on Leyte, and on 26 December MacArthur issued a communiqué announcing that "the campaign can now be regarded as closed except for minor mopping up". Yet Eichelberger's Eighth United States Army, Eighth Army killed another 27,000 Japanese on Leyte before the campaign ended in May 1945. On 18 December 1944, MacArthur was promoted to the new five-star rank of General of the Army, placing him in the company of Marshall and followed by Eisenhower and Henry H. Arnold, Henry "Hap" Arnold, the only four men to achieve the rank in World War II. Including Omar Bradley who was promoted during the Korean War so as not to be outranked by MacArthur, they were the only five men to achieve the rank of General of the Army since the 5 August 1888 death of Philip Sheridan. MacArthur was senior to all but Marshall. The rank was created by an Act of Congress when Public Law s:Public Law 78-482, 78-482 was passed on 14 December 1944, This law allowed only 75% of pay and allowances to the grade for those on the retired list. as a temporary rank, subject to reversion to permanent rank six months after the end of the war. The temporary rank was then declared permanent 23 March 1946 by Public Law 333 of the 79th Congress, which also awarded full pay and allowances in the grade to those on the retired list.

Luzon

MacArthur's next move was the Battle of Mindoro, invasion of Mindoro, where there were good potential airfield sites. Willoughby estimated, correctly as it turned out, that the island had only about 1,000 Japanese defenders. The problem this time was getting there. Kinkaid balked at sending escort carriers into the restricted waters of the Sulu Sea, and Kenney could not guarantee land based air cover. The operation was clearly hazardous, and MacArthur's staff talked him out of accompanying the invasion on ''Nashville''. As the invasion force entered the Sulu Sea, a ''kamikaze'' struck ''Nashville'', killing 133 people and wounding 190 more. Australian and American engineers had three airstrips in operation within two weeks, but the resupply convoys were repeatedly attacked by ''kamikazes''. During this time, MacArthur quarreled with Sutherland, notorious for his abrasiveness, over the latter's mistress, Captain Elaine Clark. MacArthur had instructed Sutherland not to bring Clark to Leyte, due to a personal undertaking to Curtin that Australian women on the GHQ staff would not be taken to the Philippines, but Sutherland had brought her along anyway. The way was now clear for the Battle of Luzon, invasion of Luzon. This time, based on different interpretations of the same intelligence data, Willoughby estimated the strength of General Tomoyuki Yamashita's forces on Luzon at 137,000, while Sixth Army estimated it at 234,000. MacArthur's response was "Bunk!". He felt that even Willoughby's estimate was too high. "Audacity, calculated risk, and a clear strategic aim were MacArthur's attributes", and he disregarded the estimates. In fact, they were too low; Yamashita had more than 287,000 troops on Luzon. This time, MacArthur traveled aboard the light cruiser , watching as the ship was nearly hit by a bomb and torpedoes fired by midget submarines. His communiqué read: "The decisive battle for the liberation of the Philippines and the control of the Southwest Pacific is at hand. General MacArthur is in personal command at the front and landed with his assault troops." MacArthur's primary concern was the capture of the port of Manila and the airbase at Clark Field, which were required to support future operations. He urged his commanders on. On 25 January 1945, he moved his advanced headquarters forward to Hacienda Luisita, closer to the front than Krueger's. He ordered the 1st Cavalry Division to conduct a rapid advance on Manila. It reached the northern outskirts of Manila on 3 February, but, unknown to the Americans, Rear Admiral Sanji Iwabuchi had decided to defend Manila to the death. The Battle of Manila (1945), Battle of Manila raged for the next three weeks. To spare the civilian population, MacArthur prohibited the use of air strikes, but thousands of civilians died in the crossfire or Japanese massacres. He also refused to restrict the traffic of civilians who clogged the roads in and out of Manila, placing humanitarian concerns above military ones except in emergencies. For his part in the capture of Manila, MacArthur was awarded his third Distinguished Service Cross. After taking Manila, MacArthur installed one of his Filipino friends, Manuel Roxas—who also happened to be one of the few people who knew about the huge sum of money Quezon had given MacArthur in 1942—into a position of power that ensured Roxas was to become the next Filipino president. Roxas had been a leading Japanese collaborator serving in the puppet government of José Laurel, but MacArthur claimed that Roxas had secretly been an American agent all the long. About MacArthur's claim that Roxas was really part of the resistance, Weinberg wrote that "evidence to this effect has yet to surface", and that by favoring the Japanese collaborator Roxas, MacArthur ensured there was no serious effort to address the issue of Filipino collaboration with the Japanese after the war. There was evidence that Roxas used his position of working in the Japanese puppet government to secretly gather intelligence to pass onto guerillas, MacArthur, and his intelligence staff during the occupation period. One of the major reasons for MacArthur to return to the Philippines was to liberate List of Japanese-run internment camps during World War II#Camps in the Philippines, prisoner-of-war camps and civilian internee camps as well as to relieve the Filipino civilians suffering at the hands of the very brutal Japanese occupiers. MacArthur authorized daring rescue raids at numerous prison camps like Raid at Cabanatuan, Cabanatuan, Raid on Los Baños, Los Baños, and Santo Tomas Internment Camp#Arrival of the American Army, Santo Tomas. At Santo Tomas Japanese guards held 200 prisoners hostage, but the U.S. soldiers were able to negotiate safe passage for the Japanese to escape peacefully in exchange for the release of the prisoners. After the Battle of Manila, MacArthur turned his attention to Yamashita, who had retreated into the mountains of central and northern Luzon. Yamashita chose to fight a defensive campaign, being pushed back slowly by Krueger, and was still holding out at the time the war ended, much to MacArthur's intense annoyance as he had wished to liberate the entire Philippines before the war ended. On 2 September 1945, Yamashita (who had a hard time believing that the Emperor had ordered Japan to sign an armistice) came down from the mountains to surrender with some 50,500 of his men.Southern Philippines

Although MacArthur had no specific directive to do so, and the fighting on Luzon was far from over, he committed his forces to liberate the remainder of the Philippines. In the GHQ communiqué on 5 July, he announced that the Philippines had been liberated and all operations ended, although Yamashita still held out in northern Luzon. Starting in May 1945, MacArthur used his Australian troops in the Borneo campaign (1945), invasion of Borneo. He accompanied the Battle of North Borneo, assault on Labuan and visited the troops ashore. While returning to GHQ in Manila, he visited Davao City, Davao, where he told Eichelberger that no more than 4,000 Japanese remained alive on Mindanao. A few months later, six times that number surrendered. In July 1945, he was awarded his fourth Distinguished Service Medal.

As part of preparations for Operation Downfall, the invasion of Japan, MacArthur became commander in chief U.S. Army Forces Pacific (AFPAC) in April 1945, assuming command of all Army and Army Air Force units in the Pacific except the Twentieth Air Force. At the same time, Nimitz became commander of all naval forces. Command in the Pacific therefore remained divided. During his planning of the invasion of Japan, MacArthur stressed to the decision-makers in Washington that it was essential to have the Soviet Union enter the war as he argued it was crucial to have the Red Army tie down the Kwantung army in Manchuria. Contrary to the claim that this meant that MacArthur urged Roosevelt to agree to every Soviet demand at the Yalta Conference, he was in fact not told about any of the territorial concessions to the Soviet Union in Asia as agreed upon in the secret deal that Roosevelt made with Joseph Stalin, and MacArthur said that he would not have supported the Soviet invasion of Manchuria had he known about the secret deal that involved Lüshun Port, Port Arthur, other parts of Manchuria, and northern Korea being given by the western Allies to the Soviet Union. Unlike Nimitz, who was told about the atomic bomb in February 1945, MacArthur was not told about its existence until a few days before Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Hiroshima was bombed. The invasion was pre-empted by the

Although MacArthur had no specific directive to do so, and the fighting on Luzon was far from over, he committed his forces to liberate the remainder of the Philippines. In the GHQ communiqué on 5 July, he announced that the Philippines had been liberated and all operations ended, although Yamashita still held out in northern Luzon. Starting in May 1945, MacArthur used his Australian troops in the Borneo campaign (1945), invasion of Borneo. He accompanied the Battle of North Borneo, assault on Labuan and visited the troops ashore. While returning to GHQ in Manila, he visited Davao City, Davao, where he told Eichelberger that no more than 4,000 Japanese remained alive on Mindanao. A few months later, six times that number surrendered. In July 1945, he was awarded his fourth Distinguished Service Medal.

As part of preparations for Operation Downfall, the invasion of Japan, MacArthur became commander in chief U.S. Army Forces Pacific (AFPAC) in April 1945, assuming command of all Army and Army Air Force units in the Pacific except the Twentieth Air Force. At the same time, Nimitz became commander of all naval forces. Command in the Pacific therefore remained divided. During his planning of the invasion of Japan, MacArthur stressed to the decision-makers in Washington that it was essential to have the Soviet Union enter the war as he argued it was crucial to have the Red Army tie down the Kwantung army in Manchuria. Contrary to the claim that this meant that MacArthur urged Roosevelt to agree to every Soviet demand at the Yalta Conference, he was in fact not told about any of the territorial concessions to the Soviet Union in Asia as agreed upon in the secret deal that Roosevelt made with Joseph Stalin, and MacArthur said that he would not have supported the Soviet invasion of Manchuria had he known about the secret deal that involved Lüshun Port, Port Arthur, other parts of Manchuria, and northern Korea being given by the western Allies to the Soviet Union. Unlike Nimitz, who was told about the atomic bomb in February 1945, MacArthur was not told about its existence until a few days before Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Hiroshima was bombed. The invasion was pre-empted by the Occupation of Japan

Protecting the Emperor

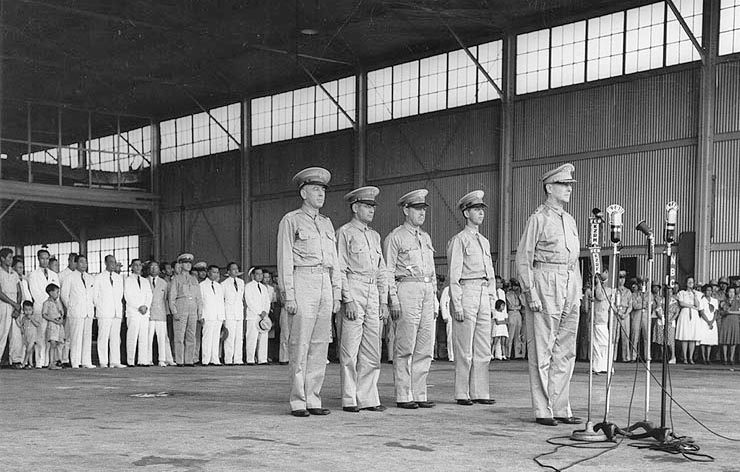

On 29 August 1945, MacArthur was ordered to exercise authority through the Japanese government machinery, including the Emperor of Japan, Emperor Hirohito. MacArthur's headquarters was located in the DN Tower 21, Dai Ichi Life Insurance Building in Tokyo. Unlike in Germany, where the Allies had in May 1945 abolished the German state, the Americans chose to allow the Japanese state to continue to exist, albeit under their ultimate control. Unlike Germany, there was a certain partnership between the occupiers and occupied as MacArthur decided to rule Japan via the Emperor and most of the rest of the Japanese elite. The Emperor was a living god to the Japanese people, and MacArthur found that ruling via the Emperor made his job in running Japan much easier than it otherwise would have been. After the Japanese surrender in August 1945, there was a large amount of pressure that came from both Allied countries and Japanese leftists that demanded the emperor step down and be indicted as a war criminal. MacArthur disagreed, as he thought that an ostensibly cooperating emperor would help establish a peaceful allied occupation regime in Japan. Since retaining the emperor was crucial to ensuring control over the population, the allied forces shielded him from war responsibility and avoided undermining his authority. Evidence that would incriminate the emperor and his family was excluded from the International Military Tribunal for the Far East.

Code-named Operation Blacklist, MacArthur created a plan that separated the emperor from the militarists, retained the emperor as a constitutional monarch but only as a figurehead, and used the emperor to retain control over Japan and help the U.S. achieve their objectives. The American historian Herbert P. Bix described the relationship between the general and the Emperor as: "the Allied commander would use the Emperor, and the Emperor would cooperate in being used. Their relationship became one of expediency and mutual protection, of more political benefit to Hirohito than to MacArthur because Hirohito had more to lose—the entire panoply of symbolic, legitimizing properties of the imperial throne".