George Washington (, 1799) was a

Founding Father

The following is a list of national founders of sovereign states who were credited with establishing a state. National founders are typically those who played an influential role in setting up the systems of governance, (i.e., political system ...

and the first

president of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president directs the Federal government of the United States#Executive branch, executive branch of the Federal government of t ...

, serving from 1789 to 1797. As commander of the

Continental Army

The Continental Army was the army of the United Colonies representing the Thirteen Colonies and later the United States during the American Revolutionary War. It was formed on June 14, 1775, by a resolution passed by the Second Continental Co ...

, Washington led

Patriot forces to victory in the

American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was the armed conflict that comprised the final eight years of the broader American Revolution, in which Am ...

against the

British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, Crown colony, colonies, protectorates, League of Nations mandate, mandates, and other Dependent territory, territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It bega ...

. He is commonly known as the

Father of the Nation

The Father of the Nation is an honorific title given to a person considered the driving force behind the establishment of a country, state, or nation. Pater Patriae was a Roman honorific meaning the "Father of the Fatherland", bestowed by th ...

for his role in bringing about

American independence

The American Revolution (1765–1783) was a colonial rebellion and war of independence in which the Thirteen Colonies broke from British rule to form the United States of America. The revolution culminated in the American Revolutionary War ...

.

Born in the

Colony of Virginia

The Colony of Virginia was a British Empire, British colonial settlement in North America from 1606 to 1776.

The first effort to create an English settlement in the area was chartered in 1584 and established in 1585; the resulting Roanoke Colo ...

, Washington became the commander of the

Virginia Regiment during the

French and Indian War

The French and Indian War, 1754 to 1763, was a colonial conflict in North America between Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and Kingdom of France, France, along with their respective Native Americans in the United States, Native American ...

(1754–1763). He was later elected to the

Virginia House of Burgesses

The House of Burgesses () was the lower house of the Virginia General Assembly from 1619 to 1776. It existed during the colonial history of the United States in the Colony of Virginia in what was then British America. From 1642 to 1776, the Hou ...

, and opposed the perceived oppression of the American colonists by the British Crown. When the American Revolutionary War against the British began in 1775, Washington was appointed

commander-in-chief of the Continental Army. He directed a poorly organized and equipped force against disciplined British troops. Washington and his army achieved an early victory at the

Siege of Boston

The siege of Boston (April 19, 1775 – March 17, 1776) was the opening phase of the American Revolutionary War. In the siege, Patriot (American Revolution), American patriot militia led by newly-installed Continental Army commander George Wash ...

in March 1776 but were forced to

retreat from New York City in November. Washington

crossed the Delaware River and won the battles of

Trenton in late 1776 and

Princeton

Princeton University is a private Ivy League research university in Princeton, New Jersey, United States. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the Unit ...

in early 1777, then lost the battles of

Brandywine and

Germantown later that year. He faced criticism of his command, low troop morale, and a lack of provisions for his forces as the war continued. Ultimately Washington led a combined French and American force to a decisive victory over the British at

Yorktown in 1781. In the resulting

Treaty of Paris in 1783, the British acknowledged the sovereign independence of the United States. Washington then served as president of the

Constitutional Convention in 1787, which drafted the current

Constitution of the United States

The Constitution of the United States is the Supremacy Clause, supreme law of the United States, United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, on March 4, 1789. Originally includi ...

.

Washington was unanimously elected the first U.S. president by the

Electoral College

An electoral college is a body whose task is to elect a candidate to a particular office. It is mostly used in the political context for a constitutional body that appoints the head of state or government, and sometimes the upper parliament ...

in 1788 and 1792. He implemented a strong, well-financed national government while remaining impartial in the fierce rivalry that emerged within his cabinet between

Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (, 1743July 4, 1826) was an American Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was the primary author of the United States Declaration of Indepe ...

and

Alexander Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton (January 11, 1755 or 1757July 12, 1804) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the first U.S. secretary of the treasury from 1789 to 1795 dur ...

. During the

French Revolution, he proclaimed

a policy of neutrality while supporting the

Jay Treaty

The Treaty of Amity, Commerce, and Navigation, Between His Britannic Majesty and the United States of America, commonly known as the Jay Treaty, and also as Jay's Treaty, was a 1794 treaty between the United States and Great Britain that averted ...

with Britain. Washington set enduring precedents for the

office of president, including

republicanism

Republicanism is a political ideology that encompasses a range of ideas from civic virtue, political participation, harms of corruption, positives of mixed constitution, rule of law, and others. Historically, it emphasizes the idea of self ...

, a

peaceful transfer of power, the use of the title "

Mr. President", and the

two-term tradition.

His 1796 farewell address became a preeminent statement on republicanism: Washington wrote about the importance of national unity and the dangers that regionalism, partisanship, and foreign influence pose to it. As a planter of tobacco and wheat at

Mount Vernon

Mount Vernon is the former residence and plantation of George Washington, a Founding Father, commander of the Continental Army in the Revolutionary War, and the first president of the United States, and his wife, Martha. An American landmar ...

,

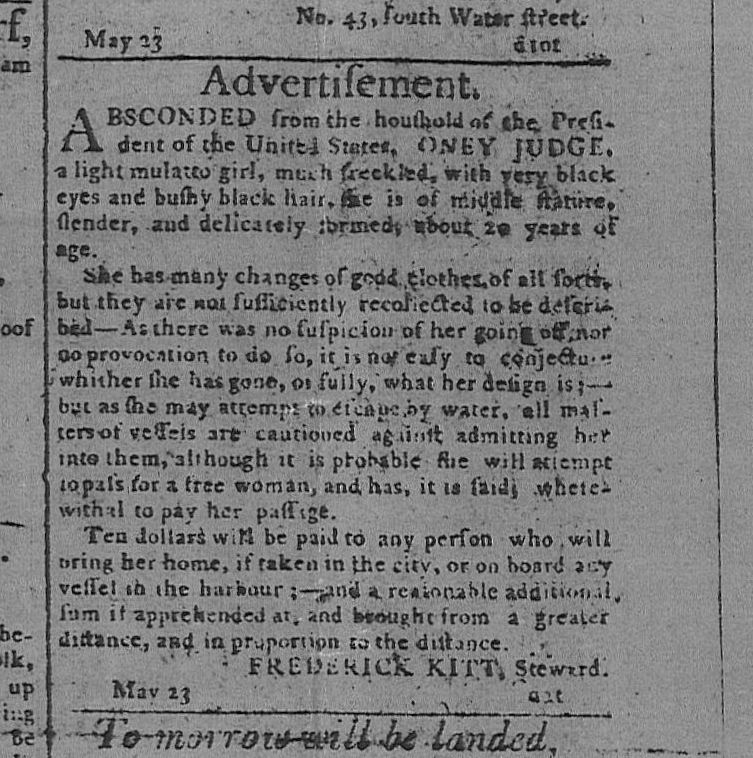

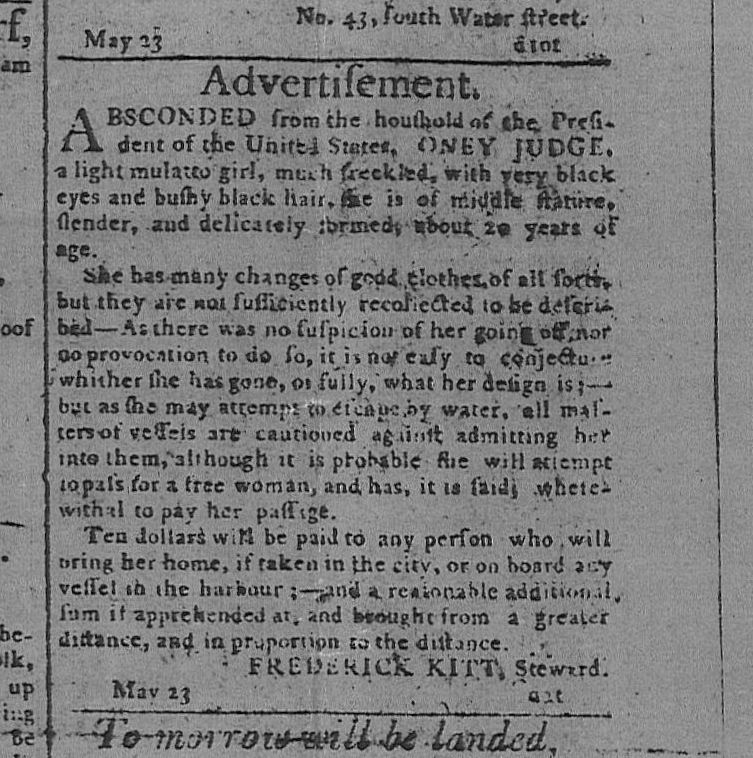

Washington owned many slaves. He began opposing slavery near the end of his life, and provided in his will for the eventual

manumission

Manumission, or enfranchisement, is the act of freeing slaves by their owners. Different approaches to manumission were developed, each specific to the time and place of a particular society. Historian Verene Shepherd states that the most wi ...

of his slaves.

Washington's image is an icon of

American culture

The culture of the United States encompasses various social behaviors, institutions, and Social norm, norms, including forms of Languages of the United States, speech, American literature, literature, Music of the United States, music, Visual a ...

and he

has been extensively memorialized; his namesakes include

the national capital and the

State of Washington

Washington, officially the State of Washington, is a state in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States. It is often referred to as Washington State to distinguish it from the national capital, both named after George Washington ...

. In both popular and scholarly polls, he is consistently considered one of the greatest presidents in American history.

Early life (1732–1752)

George Washington was born on February 22, 1732, at

Popes Creek in

Westmoreland County, Virginia

Westmoreland County is a County (United States), county located in the Northern Neck of the Virginia, Commonwealth of Virginia. As of the 2020 United States census, the population sits at 18,477. Its county seat is Montross, Virginia, Montross ...

. He was the first of six children of

Augustine

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; ; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430) was a theologian and philosopher of Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia, Roman North Africa. His writings deeply influenced the development of Western philosop ...

and

Mary Ball Washington

Mary Washington (; ) was an American planter best known for being the mother of the first president of the United States, George Washington. The second wife of Augustine Washington, she became a prominent member of the Washington family. She spe ...

. His father was a

justice of the peace and a prominent public figure who had four additional children from his first marriage to Jane Butler. Washington was not close to his father and rarely mentioned him in later years; he had a fractious relationship with his mother. Among his siblings, he was particularly close to his older half-brother

Lawrence.

The family moved to a plantation on

Little Hunting Creek in 1735 before settling at

Ferry Farm

Ferry Farm, also known as the George Washington Boyhood Home Site or the Ferry Farm Site, is the farm and home where George Washington spent much of his childhood. The site is located in Stafford County, Virginia, along the northern bank of the ...

near

Fredericksburg, Virginia

Fredericksburg is an Independent city (United States), independent city in Virginia, United States. As of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, the population was 27,982. It is south of Washington, D.C., and north of Richmond, Virginia, R ...

, in 1738. When Augustine died in 1743, Washington inherited Ferry Farm and ten slaves; Lawrence inherited Little Hunting Creek and renamed it

Mount Vernon

Mount Vernon is the former residence and plantation of George Washington, a Founding Father, commander of the Continental Army in the Revolutionary War, and the first president of the United States, and his wife, Martha. An American landmar ...

. Because of his father's death, Washington did not have the formal education his elder half-brothers had received at

Appleby Grammar School in England; he instead attended the

Lower Church School in

Hartfield. He learned mathematics and land

surveying

Surveying or land surveying is the technique, profession, art, and science of determining the land, terrestrial Plane (mathematics), two-dimensional or Three-dimensional space#In Euclidean geometry, three-dimensional positions of Point (geom ...

, and became a talented

draftsman and

mapmaker. By early adulthood, he was writing with what his biographer

Ron Chernow

Ronald Chernow (; born March 3, 1949) is an American writer, journalist, and biographer. He has written bestselling historical non-fiction biographies.

Chernow won the 2011 Pulitzer Prize, 2011 Pulitzer Prize for Biography and the 2011 American ...

described as "considerable force" and "precision". As a teenager, Washington compiled over a hundred rules for social interaction styled ''The Rules of Civility'', copied from an English translation of a French guidebook.

Washington often visited

Belvoir, the plantation of

William Fairfax, Lawrence's father-in-law, and Mount Vernon. Fairfax became Washington's patron and surrogate father. In 1748, Washington spent a month with a team surveying Fairfax's

Shenandoah Valley

The Shenandoah Valley () is a geographic valley and cultural region of western Virginia and the eastern panhandle of West Virginia in the United States. The Valley is bounded to the east by the Blue Ridge Mountains, to the west by the east ...

property. The following year, he received a surveyor's license from the

College of William & Mary

The College of William & Mary (abbreviated as W&M) is a public university, public research university in Williamsburg, Virginia, United States. Founded in 1693 under a royal charter issued by King William III of England, William III and Queen ...

. Even though Washington had not served the customary

apprenticeship

Apprenticeship is a system for training a potential new practitioners of a trade or profession with on-the-job training and often some accompanying study. Apprenticeships may also enable practitioners to gain a license to practice in a regulat ...

,

Thomas Fairfax

Sir Thomas Fairfax (17 January 1612 – 12 November 1671) was an English army officer and politician who commanded the New Model Army from 1645 to 1650 during the English Civil War. Because of his dark hair, he was known as "Black Tom" to his l ...

(William's cousin) appointed him surveyor of

Culpeper County, Virginia

Culpeper County is a county located along the borderlands of the northern and central region of the Commonwealth of Virginia. As of the 2020 United States census, the population was 52,552. Its county seat and only incorporated community is ...

. Washington took his oath of office on July 20, 1749, and resigned in 1750.

[ By 1752, he had bought almost in the Shenandoah Valley and owned .

In 1751, Washington left mainland North America for the first and only time, when he accompanied Lawrence to ]Barbados

Barbados, officially the Republic of Barbados, is an island country in the Atlantic Ocean. It is part of the Lesser Antilles of the West Indies and the easternmost island of the Caribbean region. It lies on the boundary of the South American ...

, hoping the climate would cure his brother's tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB), also known colloquially as the "white death", or historically as consumption, is a contagious disease usually caused by ''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can al ...

. Washington contracted smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by Variola virus (often called Smallpox virus), which belongs to the genus '' Orthopoxvirus''. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (W ...

during the trip, which left his face slightly scarred. Lawrence died in 1752, and Washington leased Mount Vernon from his widow, Anne; he inherited it outright after her death in 1761.

Colonial military career (1752–1758)

Lawrence Washington's service as adjutant general of the Virginia militia

The Virginia militia is an armed force composed of all citizens of the Commonwealth of Virginia capable of bearing arms. The Virginia militia was established in 1607 as part of the English militia system. Militia service in Virginia was compulso ...

inspired George to seek a militia commission. Virginia's lieutenant governor, Robert Dinwiddie

Robert Dinwiddie (1692 – 27 July 1770) was a Scottish colonial administrator who served as the lieutenant governor of Virginia from 1751 to 1758. Since the governors of Virginia remained in Great Britain, he served as the ''de facto'' head o ...

, appointed Washington as a major and commander of one of the four militia districts. The British and French were competing for control of the Ohio River Valley: the British were constructing forts along the river, and the French between the river and Lake Erie

Lake Erie ( ) is the fourth-largest lake by surface area of the five Great Lakes in North America and the eleventh-largest globally. It is the southernmost, shallowest, and smallest by volume of the Great Lakes and also has the shortest avera ...

.

In October 1753, Dinwiddie appointed Washington as a special envoy

Diplomatic rank is a system of professional and social rank used in the world of diplomacy and international relations. A diplomat's rank determines many ceremonial details, such as the order of precedence at official processions, table seating ...

to demand the French forces vacate land that was claimed by the British. Washington was also directed to make peace with the Iroquois Confederacy

The Iroquois ( ), also known as the Five Nations, and later as the Six Nations from 1722 onwards; alternatively referred to by the Endonym and exonym, endonym Haudenosaunee ( ; ) are an Iroquoian languages, Iroquoian-speaking Confederation#Ind ...

and to gather intelligence about the French forces. Washington met with Iroquois leader Tanacharison at Logstown

The riverside village of Logstown (1726?, 1727–1758) also known as Logg's Town, French: ''Chiningue'' (transliterated to ''Shenango'') near modern-day Baden, Pennsylvania, was a significant Native American settlement in Western Pennsylv ...

. Washington said that at this meeting Tanacharison named him Conotocaurius. This name, meaning "devourer of villages", had previously been given to his great-grandfather John Washington

John Washington (1633 – 1677) was an English-born merchant, planter, politician and military officer. Born in Tring, Hertfordshire, he subsequently immigrated to the English colony of Virginia and became a member of the planter class. In add ...

in the late 17th century by the Susquehannock

The Susquehannock, also known as the Conestoga, Minquas, and Andaste, were an Iroquoian Peoples, Iroquoian people who lived in the lower Susquehanna River watershed in what is now Pennsylvania. Their name means “people of the muddy river.”

T ...

.

Washington's party reached the Ohio River in November 1753 and was intercepted by a French patrol. The party was escorted to Fort Le Boeuf, where Washington was received in a friendly manner. He delivered the British demand to vacate to the French commander Jacques Legardeur de Saint-Pierre

Jacques Legardeur de Saint-Pierre (October 24, 1701 - September 8, 1755) was a Canadian colonial military commander and explorer who held posts throughout North America in the 18th century, just before and during the French and Indian War.

Famil ...

, but the French refused to leave. Saint-Pierre gave Washington his official answer after a few days' delay, as well as food and winter clothing for his party's journey back to Virginia. Washington completed the precarious mission in difficult winter conditions, achieving a measure of distinction when his report was published in Virginia and London.

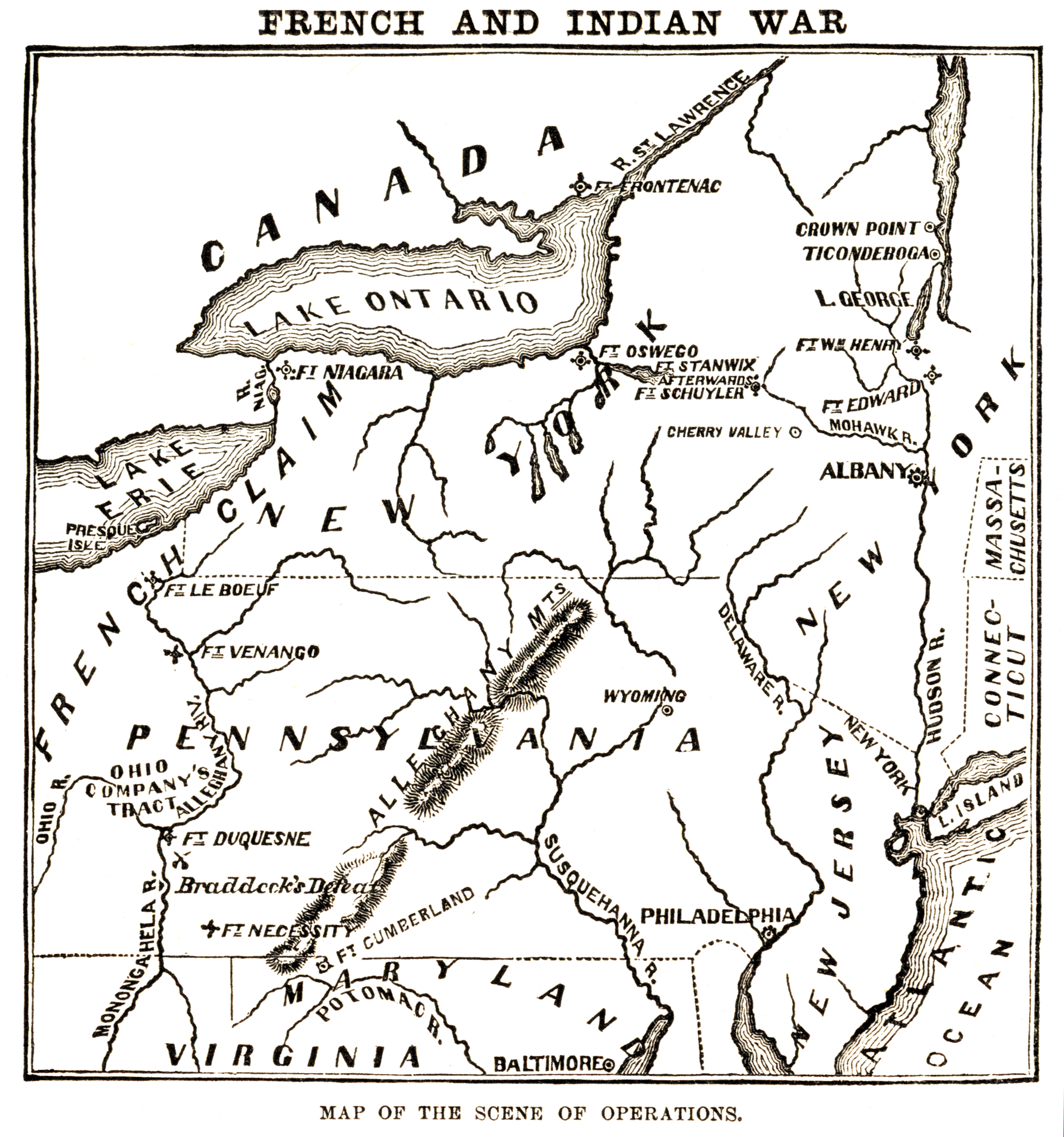

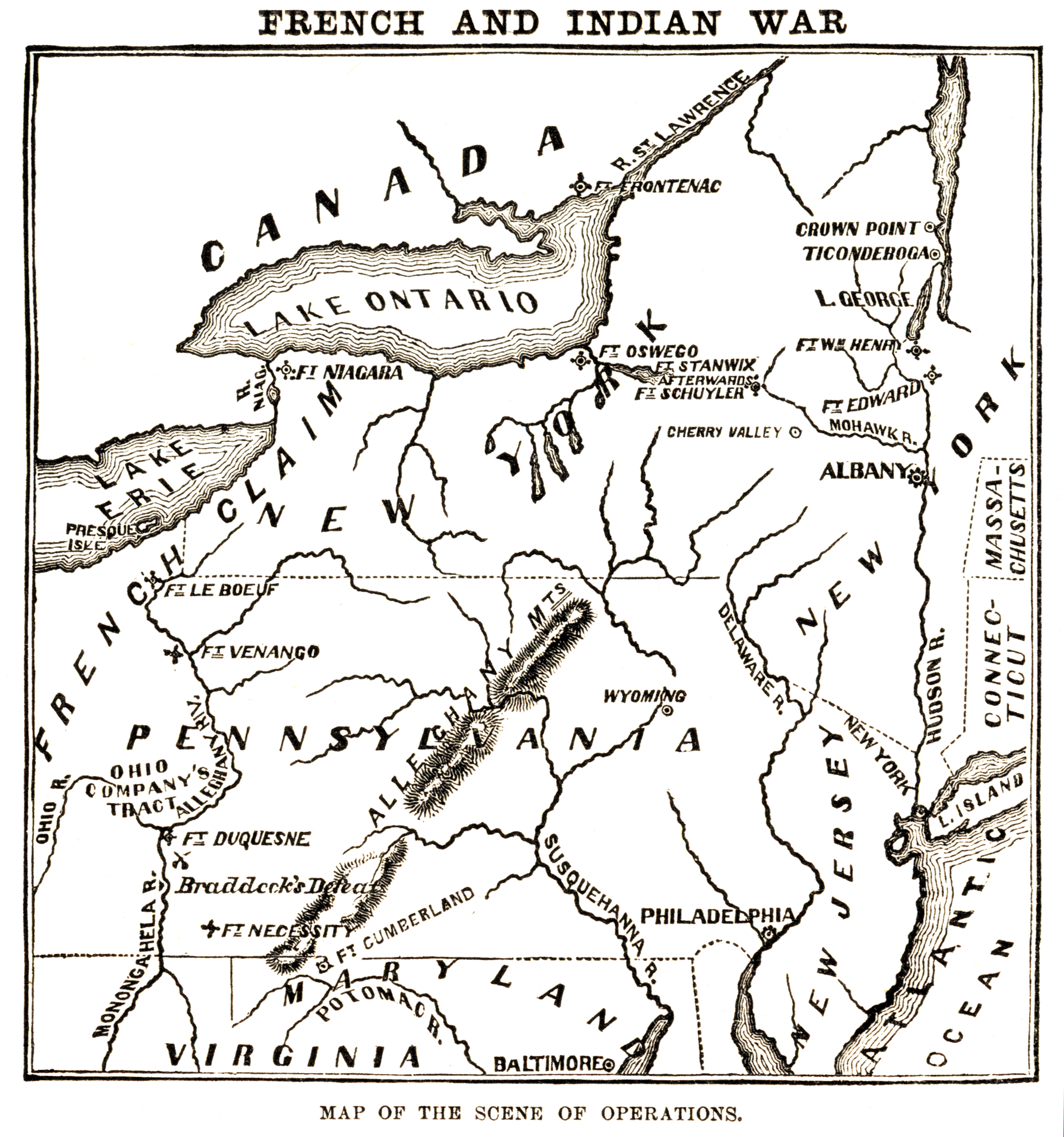

French and Indian War

In February 1754, Dinwiddie promoted Washington to lieutenant colonel and second-in-command of the 300-strong Virginia Regiment, with orders to confront the French at the Forks of the Ohio. Washington set out with half the regiment in April and was soon aware that a French force of 1,000 had begun construction of

In February 1754, Dinwiddie promoted Washington to lieutenant colonel and second-in-command of the 300-strong Virginia Regiment, with orders to confront the French at the Forks of the Ohio. Washington set out with half the regiment in April and was soon aware that a French force of 1,000 had begun construction of Fort Duquesne

Fort Duquesne ( , ; originally called ''Fort Du Quesne'') was a fort established by the French in 1754, at the confluence of the Allegheny and Monongahela rivers. It was later taken over by the British, and later the Americans, and developed ...

there. In May, having established a defensive position at Great Meadows, Washington learned that the French had made camp away; he decided to take the offensive. The French detachment proved to be only about 50 men, so on May 28 Washington commanded an ambush. His small force of Virginians and Indian allies killed the French, including their commander Joseph Coulon de Jumonville

Joseph Coulon de Villiers, Sieur de Jumonville (September 8, 1718 – May 28, 1754) was a French Canadian military officer. His last rank was second ensign (''enseigne en second''). Jumonville's defeat and killing at the Battle of Jumonville Glen ...

, who had been carrying a diplomatic message for the British. The French later found their countrymen dead and scalped

Scalping is the act of cutting or tearing a part of the human scalp, with hair attached, from the head, and generally occurred in warfare with the scalp being a trophy. Scalp-taking is considered part of the broader cultural practice of the taki ...

, blaming Washington, who had retreated to Fort Necessity

Fort Necessity National Battlefield is a National Battlefield in Fayette County, Pennsylvania, United States, which preserves the site of the Battle of Fort Necessity. The battle, which took place on July 3, 1754, was an early battle of the ...

.

The rest of the Virginia Regiment joined Washington the following month with news that he had been promoted to the rank of colonel and given command of the full regiment. They were reinforced by an independent company of a hundred South Carolinians led by Captain James Mackay; his royal commission outranked Washington's and a conflict of command ensued. On July 3, 900 French soldiers attacked Fort Necessity, and the ensuing battle ended in Washington's surrender. Washington did not speak French, but signed a surrender document in which he unwittingly took responsibility for "assassinating" Jumonville, later blaming the translator for not properly translating it. The Virginia Regiment was divided and Washington was offered a captaincy in one of the newly formed regiments. He refused, as it would have been a demotion—the British had ordered that "colonials" could not be ranked any higher than captain—and instead resigned his commission.French and Indian War

The French and Indian War, 1754 to 1763, was a colonial conflict in North America between Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and Kingdom of France, France, along with their respective Native Americans in the United States, Native American ...

.

In 1755, Washington volunteered as an aide to General Edward Braddock

Edward Braddock (January 1695 – 13 July 1755) was a British officer and commander-in-chief for the Thirteen Colonies during the start of the French and Indian War (1754–1763), the North American front of what is known in Europe and Canada as ...

, who led a British expedition to expel the French from Fort Duquesne and the Ohio Country

The Ohio Country (Ohio Territory, Ohio Valley) was a name used for a loosely defined region of colonial North America west of the Appalachian Mountains and south of Lake Erie.

Control of the territory and the region's fur trade was disputed i ...

. On Washington's recommendation, Braddock split the army into one main column and a smaller "flying column". Washington was suffering from severe dysentery

Dysentery ( , ), historically known as the bloody flux, is a type of gastroenteritis that results in bloody diarrhea. Other symptoms may include fever, abdominal pain, and a feeling of incomplete defecation. Complications may include dehyd ...

so did not initially travel with the expedition forces. When he rejoined Braddock at Monongahela, still very ill, the French and their Indian allies ambushed the divided army. Two-thirds of the British force became casualties in the ensuing Battle of the Monongahela, and Braddock was killed. Under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Gage

General Thomas Gage (10 March 1718/192 April 1787) was a British Army officer and colonial administrator best known for his many years of service in North America, including serving as Commander-in-Chief, North America during the early days ...

, Washington rallied the survivors and formed a rear guard

A rearguard or rear security is a part of a military force that protects it from attack from the rear, either during an advance or withdrawal. The term can also be used to describe forces protecting lines, such as communication lines, behind an ...

, allowing the remnants of the force to retreat. During the engagement, Washington had two horses shot out from under him, and his hat and coat were pierced by bullets. His conduct redeemed his reputation among critics of his command in the Battle of Fort Necessity, but he was not included by the succeeding commander (Colonel Thomas Dunbar) in planning subsequent operations.

The Virginia Regiment was reconstituted in August 1755, and Dinwiddie appointed Washington its commander, again with the rank of colonel. Washington clashed over seniority almost immediately, this time with Captain John Dagworthy, who commanded a detachment of Marylanders at the regiment's headquarters in Fort Cumberland. Washington, impatient for an offensive against Fort Duquesne, was convinced Braddock would have granted him a royal commission and pressed his case in February 1756 with Braddock's successor as Commander-in-Chief, William Shirley

William Shirley (2 December 1694 – 24 March 1771) was a British colonial administrator who served as the governor of the British American colonies of Massachusetts Bay and the Bahamas. He is best known for his role in organizing the succ ...

, and again in January 1757 with Shirley's successor, Lord Loudoun. Loudoun humiliated Washington, refused him a royal commission, and agreed only to relieve him of the responsibility of manning Fort Cumberland.

In 1758, the Virginia Regiment was assigned to the British Forbes Expedition to capture Fort Duquesne.[ General John Forbes took Washington's advice on some aspects of the expedition but rejected his opinion on the best route to the fort. Forbes nevertheless made Washington a brevet brigadier general and gave him command of one of the three brigades that was assigned to assault the fort. The French had abandoned the fort and the valley before the assault, however, and Washington only saw a ]friendly fire

In military terminology, friendly fire or fratricide is an attack by belligerent or neutral forces on friendly troops while attempting to attack enemy or hostile targets. Examples include misidentifying the target as hostile, cross-fire while ...

incident which left 14 dead and 26 injured. Frustrated, he resigned his commission soon afterwards and returned to Mount Vernon.

Under Washington, the Virginia Regiment had defended of frontier against twenty Indian attacks in ten months. He increased the professionalism of the regiment as it grew from 300 to 1,000 men. Though he failed to realize a royal commission, which made him hostile towards the British,[ he gained self-confidence, leadership skills, and knowledge of British military tactics. The destructive competition Washington witnessed among colonial politicians fostered his later support of a strong central government.

]

Marriage, civilian and political life (1759–1775)

On January 6, 1759, Washington, at age 26, married Martha Dandridge Custis, the 27-year-old widow of wealthy plantation owner Daniel Parke Custis

Daniel Parke Custis (October 15, 1711 – July 8, 1757) was an American planter and politician who was the first husband of Martha Dandridge. After his death, his widow, Martha Dandridge Custis married George Washington, who later became the fir ...

. Martha was intelligent, gracious, and experienced in managing a planter's estate, and the couple had a happy marriage. They lived at Mount Vernon, where Washington cultivated tobacco and wheat. The marriage gave Washington control over Martha's one-third dower

Dower is a provision accorded traditionally by a husband or his family, to a wife for her support should she become widowed. It was settlement (law), settled on the bride (being given into trust instrument, trust) by agreement at the time of t ...

interest in the Custis estate, and he managed the remaining two-thirds for Martha's children. As a result, he became one of the wealthiest men in Virginia, which increased his social standing.

At Washington's urging, Governor Lord Botetourt fulfilled Dinwiddie's 1754 promise to grant land bounties to those who served with volunteer militias during the French and Indian War. In late 1770, Washington inspected the lands in the Ohio and Great Kanawha regions, and he engaged surveyor William Crawford to subdivide it. Crawford allotted to Washington, who told the veterans that their land was unsuitable for farming and agreed to purchase , leaving some feeling that they had been duped. He also doubled the size of Mount Vernon to and, by 1775, had more than doubled its slave population to over one hundred.

As a respected military hero and large landowner, Washington held local offices and was elected to the Virginia provincial legislature, representing Frederick County in the Virginia House of Burgesses

The House of Burgesses () was the lower house of the Virginia General Assembly from 1619 to 1776. It existed during the colonial history of the United States in the Colony of Virginia in what was then British America. From 1642 to 1776, the Hou ...

for seven years beginning in 1758. Early in his legislative career, Washington rarely spoke at or even attended legislative sessions, but was more politically active starting in the 1760s, becoming a prominent critic of Britain's taxation and mercantilist

Mercantilism is a nationalist economic policy that is designed to maximize the exports and minimize the imports of an economy. It seeks to maximize the accumulation of resources within the country and use those resources for one-sided trade. ...

policies towards the American colonies. Washington imported luxury goods from England, paying for them by exporting tobacco. His profligate spending combined with low tobacco prices left him £1,800 in debt by 1764. Washington's complete reliance on London tobacco buyer and merchant Robert Cary also threatened his economic security. Between 1764 and 1766, he sought to diversify his holdings: he changed Mount Vernon's primary cash crop from tobacco to wheat and expanded operations to include flour milling and hemp farming. Washington's stepdaughter Patsy suffered from epileptic

Epilepsy is a group of non-communicable neurological disorders characterized by a tendency for recurrent, unprovoked seizures. A seizure is a sudden burst of abnormal electrical activity in the brain that can cause a variety of symptoms, rang ...

attacks, and she died at Mount Vernon in 1773, allowing Washington to use part of the inheritance from her estate to settle his debts.

Opposition to the British Parliament and Crown

Washington was opposed to the taxes which the British Parliament

The Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is the supreme legislative body of the United Kingdom, and may also legislate for the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories. It meets at the Palace of ...

imposed on the Colonies without proper representation. He believed the Stamp Act 1765

The Stamp Act 1765, also known as the Duties in American Colonies Act 1765 (5 Geo. 3. c. 12), was an Act of Parliament (United Kingdom), act of the Parliament of Great Britain which imposed a direct tax on the British America, British coloni ...

was oppressive and celebrated its repeal the following year. In response to the Townshend Acts

The Townshend Acts () or Townshend Duties were a series of British acts of Parliament enacted in 1766 and 1767 introducing a series of taxes and regulations to enable administration of the British colonies in America. They are named after Char ...

, he introduced a proposal in May 1769 which urged Virginians to boycott British goods; the Townshend Acts were mostly repealed in 1770. Washington and other colonists were also angered by the Royal Proclamation of 1763

The Royal Proclamation of 1763 was issued by British King George III on 7 October 1763. It followed the Treaty of Paris (1763), which formally ended the Seven Years' War and transferred French territory in North America to Great Britain. The ...

(which banned American settlement west of the Allegheny Mountains

The Allegheny Mountain Range ( ) — also spelled Alleghany or Allegany, less formally the Alleghenies — is part of the vast Appalachian Mountain Range of the Eastern United States and Canada. Historically it represented a significant barr ...

) and British interference in American western land speculation

In finance, speculation is the purchase of an asset (a commodity, good (economics), goods, or real estate) with the hope that it will become more valuable in a brief amount of time. It can also refer to short sales in which the speculator hope ...

(in which Washington was a participant).

Parliament sought to punish Massachusetts colonists for their role in the Boston Tea Party

The Boston Tea Party was a seminal American protest, political and Mercantilism, mercantile protest on December 16, 1773, during the American Revolution. Initiated by Sons of Liberty activists in Boston in Province of Massachusetts Bay, colo ...

in 1774 by passing the Coercive Acts

The Intolerable Acts, sometimes referred to as the Insufferable Acts or Coercive Acts, were a series of five punitive laws passed by the British Parliament in 1774 after the Boston Tea Party. The laws aimed to punish Massachusetts colonists fo ...

, which Washington saw as "an invasion of our rights and privileges". That July, he and George Mason

George Mason (October 7, 1792) was an American planter, politician, Founding Father, and delegate to the U.S. Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in 1787, where he was one of three delegates who refused to sign the Constitution. His wr ...

drafted a list of resolutions for the Fairfax County committee, including a call to end the Atlantic slave trade

The Atlantic slave trade or transatlantic slave trade involved the transportation by slave traders of Slavery in Africa, enslaved African people to the Americas. European slave ships regularly used the triangular trade route and its Middle Pass ...

; the resolutions were adopted. In August, Washington attended the First Virginia Convention and was selected as a delegate to the First Continental Congress

The First Continental Congress was a meeting of delegates of twelve of the Thirteen Colonies held from September 5 to October 26, 1774, at Carpenters' Hall in Philadelphia at the beginning of the American Revolution. The meeting was organized b ...

. As tensions rose in 1774, he helped train militias in Virginia and organized enforcement of the Continental Association

The Continental Association, also known as the Articles of Association or simply the Association, was an agreement among the Thirteen Colonies, American colonies, adopted by the First Continental Congress, which met inside Carpenters' Hall in Phi ...

boycott of British goods instituted by the Congress.

Commander in chief of the army (1775–1783)

The American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was the armed conflict that comprised the final eight years of the broader American Revolution, in which Am ...

broke out on April 19, 1775, with the Battles of Lexington and Concord

The Battles of Lexington and Concord on April 19, 1775 were the first major military actions of the American Revolutionary War between the Kingdom of Great Britain and Patriot (American Revolution), Patriot militias from America's Thirteen Co ...

. Washington hastily departed Mount Vernon on May 4 to join the Second Continental Congress

The Second Continental Congress (1775–1781) was the meetings of delegates from the Thirteen Colonies that united in support of the American Revolution and American Revolutionary War, Revolutionary War, which established American independence ...

in Philadelphia

Philadelphia ( ), colloquially referred to as Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania, most populous city in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania and the List of United States cities by population, sixth-most populous city in the Unit ...

. On June 14, Congress created the Continental Army

The Continental Army was the army of the United Colonies representing the Thirteen Colonies and later the United States during the American Revolutionary War. It was formed on June 14, 1775, by a resolution passed by the Second Continental Co ...

and John Adams

John Adams (October 30, 1735 – July 4, 1826) was a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the second president of the United States from 1797 to 1801. Before Presidency of John Adams, his presidency, he was a leader of ...

nominated Washington as its commander-in-chief, mainly because of his military experience and the belief that a Virginian would better unite the colonies. He was unanimously elected by Congress the next day. Washington gave an acceptance speech on June 16, declining a salary, though he was later reimbursed expenses.

Congress chose Washington's primary staff officers, including Artemas Ward, Horatio Gates

Horatio Lloyd Gates (July 26, 1727April 10, 1806) was a British-born American army officer who served as a general in the Continental Army during the early years of the American Revolutionary War, Revolutionary War. He took credit for the Ameri ...

, Charles Lee, Philip Schuyler

Philip John Schuyler (; November 20, 1733 - November 18, 1804) was an American general in the American Revolutionary War, Revolutionary War and a United States Senate, United States Senator from New York (state), New York. He is usually known as ...

, and Nathanael Greene

Major general (United States), Major General Nathanael Greene (August 7, 1742 – June 19, 1786) was an American military officer and planter who served in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War, Revolutionary War. He emerge ...

. Henry Knox

Henry Knox (July 25, 1750 – October 25, 1806) was an American military officer, politician, bookseller, and a Founding Father of the United States. Knox, born in Boston, became a senior general of the Continental Army during the Revolutionar ...

impressed Adams and Washington with his knowledge of ordnance and was promoted to colonel and chief of artillery. Similarly, Washington was impressed by Alexander Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton (January 11, 1755 or 1757July 12, 1804) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the first U.S. secretary of the treasury from 1789 to 1795 dur ...

's intelligence and bravery; he would later promote Hamilton to colonel and appoint him his aide-de-camp.

Washington initially banned the enlistment of Black soldiers, both free and enslaved. The British saw an opportunity to divide the colonies: the colonial governor of Virginia issued a proclamation promising freedom to slaves if they joined the British forces. In response to this proclamation and the need for troops, Washington soon overturned his ban. By the end of the war, around one-tenth of the soldiers in the Continental Army were Black, with some obtaining freedom.

Siege of Boston

In April 1775, in response to the growing rebellious movement, British troops occupied Boston

Boston is the capital and most populous city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Massachusetts in the United States. The city serves as the cultural and Financial centre, financial center of New England, a region of the Northeas ...

, led by General Thomas Gage

General Thomas Gage (10 March 1718/192 April 1787) was a British Army officer and colonial administrator best known for his many years of service in North America, including serving as Commander-in-Chief, North America during the early days ...

, commander of British forces in America. Local militias surrounded the city and trapped the British troops, resulting in a standoff. As Washington headed for Boston, he was greeted by cheering crowds and political ceremony; he became a symbol of the Patriot cause. Upon Washington's arrival on July 2, he went to inspect the army, but found undisciplined militia. After consultation, he initiated Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin (April 17, 1790) was an American polymath: a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher and Political philosophy, political philosopher.#britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the m ...

's suggested reforms, instituting military drills and imposing strict disciplinary measures. Washington promoted some of the soldiers who had performed well at Bunker Hill to officer rank, and removed officers who he saw as incompetent. In October, King George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and King of Ireland, Ireland from 25 October 1760 until his death in 1820. The Acts of Union 1800 unified Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and ...

declared that the colonies were in open rebellion and relieved Gage of command, replacing him with General William Howe.

When the Charles River

The Charles River (Massachusett language, Massachusett: ), sometimes called the River Charles or simply the Charles, is an river in eastern Massachusetts. It flows northeast from Hopkinton, Massachusetts, Hopkinton to Boston along a highly me ...

froze over, Washington was eager to cross and storm Boston, but Gates and others were opposed to having untrained militia attempt to assault well-garrisoned fortifications. Instead, Washington agreed to secure the Dorchester Heights above Boston to try to force the British out. On March 17, 8,906 British troops, 1,100 Loyalists

Loyalism, in the United Kingdom, its overseas territories and its former colonies, refers to the allegiance to the British crown or the United Kingdom. In North America, the most common usage of the term refers to loyalty to the British Cr ...

, and 1,220 women and children began a chaotic naval evacuation. Washington entered the city with 500 men, giving them explicit orders not to plunder. He refrained from exerting military authority in Boston, leaving civilian matters in the hands of local authorities.

New York and New Jersey

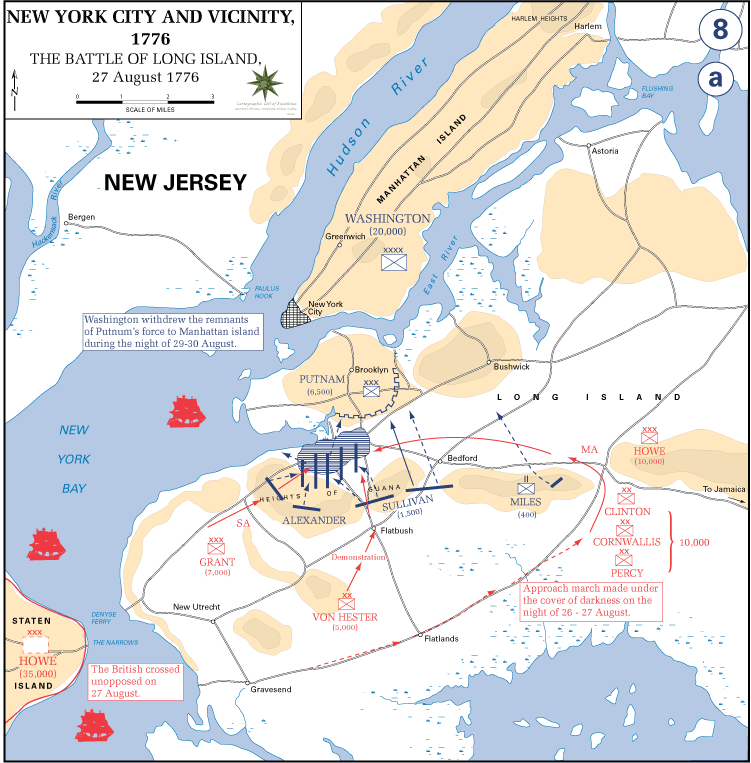

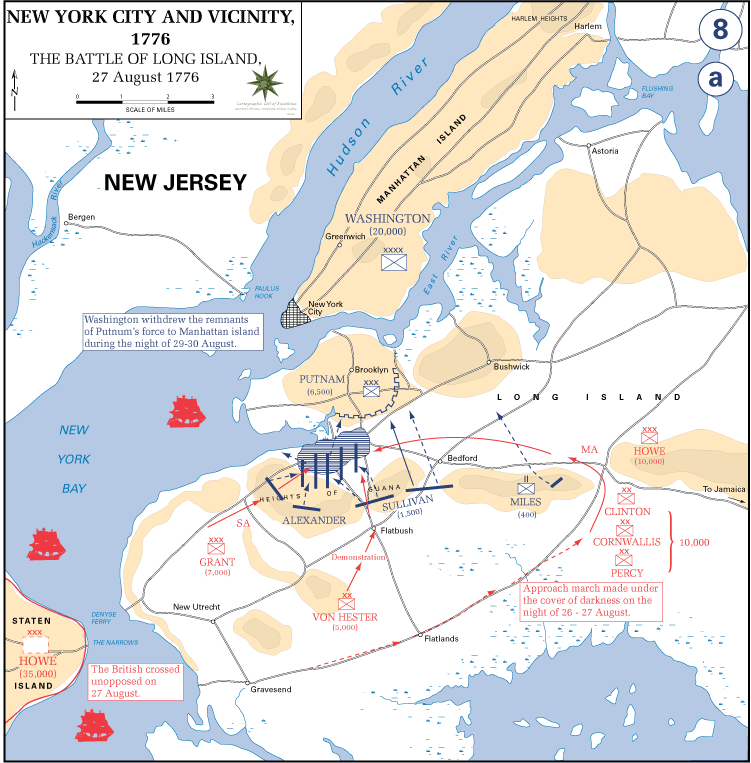

Battle of Long Island

After the victory at Boston, Washington correctly guessed that the British would return to New York City and retaliate. He arrived there on April 13, 1776, and ordered the construction of fortifications. He also ordered his forces to treat civilians and their property with respect, to avoid the abuses Bostonians suffered at the hands of British troops. The British forces, including more than a hundred ships and thousands of troops, began arriving on

After the victory at Boston, Washington correctly guessed that the British would return to New York City and retaliate. He arrived there on April 13, 1776, and ordered the construction of fortifications. He also ordered his forces to treat civilians and their property with respect, to avoid the abuses Bostonians suffered at the hands of British troops. The British forces, including more than a hundred ships and thousands of troops, began arriving on Staten Island

Staten Island ( ) is the southernmost of the boroughs of New York City, five boroughs of New York City, coextensive with Richmond County and situated at the southernmost point of New York (state), New York. The borough is separated from the ad ...

in July to lay siege to the city.

Howe's troop strength totaled 32,000 regulars and Hessian auxiliaries; Washington had 23,000 men, mostly untrained recruits and militia. In August, Howe landed 20,000 troops at Gravesend, Brooklyn

Gravesend is a neighborhood in the south-central section of the New York City Boroughs of New York City, borough of Brooklyn, on the southwestern edge of Long Island in the United States, U.S. state of New York (state), New York. It is bounded ...

, and approached Washington's fortifications. Overruling his generals, Washington chose to fight, based on inaccurate information that Howe's army had only around 8,000 soldiers. In the Battle of Long Island

The Battle of Long Island, also known as the Battle of Brooklyn and the Battle of Brooklyn Heights, was an action of the American Revolutionary War fought on August 27, 1776, at and near the western edge of Long Island in present-day Brooklyn ...

, Howe assaulted Washington's flank and inflicted 1,500 Patriot casualties. Washington retreated to Manhattan

Manhattan ( ) is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the Boroughs of New York City, five boroughs of New York City. Coextensive with New York County, Manhattan is the County statistics of the United States#Smallest, larg ...

.

Howe sent a message to Washington to negotiate peace, addressing him as "George Washington, Esq." Washington declined to accept the message, demanding to be addressed with diplomatic protocol—not as a rebel. Despite misgivings, Washington heeded the advice of General Greene to defend Fort Washington, but was ultimately forced to abandon it. Howe pursued and Washington retreated across the Hudson River

The Hudson River, historically the North River, is a river that flows from north to south largely through eastern New York (state), New York state. It originates in the Adirondack Mountains at Henderson Lake (New York), Henderson Lake in the ...

to Fort Lee. In November, Howe captured Fort Washington. Loyalists in New York City considered Howe a liberator and spread a rumor that Washington had set fire to the city. Now reduced to 5,400 troops, Washington's army retreated through New Jersey

New Jersey is a U.S. state, state located in both the Mid-Atlantic States, Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern United States, Northeastern regions of the United States. Located at the geographic hub of the urban area, heavily urbanized Northeas ...

.

Crossing the Delaware, Trenton, and Princeton

Washington crossed the Delaware River

The Delaware River is a major river in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States and is the longest free-flowing (undammed) river in the Eastern United States. From the meeting of its branches in Hancock, New York, the river flows for a ...

into Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania, officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a U.S. state, state spanning the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern United States, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes region, Great Lakes regions o ...

, where General John Sullivan joined him with 2,000 more troops. The future of the Continental Army was in doubt due to a lack of supplies, a harsh winter, expiring enlistments, and desertion

Desertion is the abandonment of a military duty or post without permission (a pass, liberty or leave) and is done with the intention of not returning. This contrasts with unauthorized absence (UA) or absence without leave (AWOL ), which ...

s. Howe posted a Hessian garrison at Trenton to hold western New Jersey and the east shore of the Delaware. At sunrise on December 26, 1776, Washington, aided by Colonel Knox and artillery, led his men in a successful surprise attack on the Hessians.

Washington returned to New Jersey on January 3, 1777, launching an attack on the British regulars at Princeton

Princeton University is a private Ivy League research university in Princeton, New Jersey, United States. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the Unit ...

, with 40 Americans killed or wounded and 273 British killed or captured. Howe retreated to New York City for the winter. Washington took up winter headquarters in Morristown, New Jersey

Morristown () is a Town (New Jersey), town in and the county seat of Morris County, New Jersey, Morris County, in the U.S. state of New Jersey. . Strategically, Washington's victories at Trenton and Princeton were pivotal: they revived Patriot morale and quashed the British strategy of showing overwhelming force followed by offering generous terms, changing the course of the war.

Philadelphia

Brandywine, Germantown, and Saratoga

In July 1777, the British general John Burgoyne

General (United Kingdom), General John "Gentleman Johnny" Burgoyne (24 February 1722 – 4 August 1792) was a British Army officer, playwright and politician who sat in the House of Commons of Great Britain from 1761 to 1792. He first saw acti ...

led his British troops south from Quebec

Quebec is Canada's List of Canadian provinces and territories by area, largest province by area. Located in Central Canada, the province shares borders with the provinces of Ontario to the west, Newfoundland and Labrador to the northeast, ...

in the Saratoga campaign

The Saratoga campaign in 1777 was an attempt by the British to gain military control of the strategically important Hudson River valley during the American Revolutionary War. It ended in the surrender of a British army, which historian Edmund M ...

; he recaptured Fort Ticonderoga, intending to divide New England

New England is a region consisting of six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York (state), New York to the west and by the ...

. However, General Howe took his army from New York City south to Philadelphia rather than joining Burgoyne near Albany. Washington and Gilbert, Marquis de Lafayette rushed to Philadelphia to engage Howe. In the Battle of Brandywine

The Battle of Brandywine, also known as the Battle of Brandywine Creek, was fought between the American Continental Army of General George Washington and the British Army of General Sir William Howe on September 11, 1777, as part of the Am ...

on September 11, 1777, Howe outmaneuvered Washington and marched unopposed into the American capital at Philadelphia. A Patriot attack against the British at Germantown in October failed.

In Upstate New York

Upstate New York is a geographic region of New York (state), New York that lies north and northwest of the New York metropolitan area, New York City metropolitan area of downstate New York. Upstate includes the middle and upper Hudson Valley, ...

, the Patriots were led by General Horatio Gates. Concerned about Burgoyne's movements southward, Washington sent reinforcements north with Generals Benedict Arnold

Benedict Arnold (#Brandt, Brandt (1994), p. 4June 14, 1801) was an American-born British military officer who served during the American Revolutionary War. He fought with distinction for the American Continental Army and rose to the rank of ...

and Benjamin Lincoln

Benjamin Lincoln (January 24, 1733 ( O.S. January 13, 1733) – May 9, 1810) was an American army officer. He served as a major general in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War. Lincoln was involved in three major surrender ...

. On October 7, 1777, Burgoyne tried to take Bemis Heights but was isolated from support and forced to surrender. Gates' victory emboldened Washington's critics, who favored Gates as a military leader. According to the biographer John Alden, "It was inevitable that the defeats of Washington's forces and the concurrent victory of the forces in upper New York should be compared." Admiration for Washington was waning.

Valley Forge and Monmouth

Washington and his army of 11,000 men went into winter quarters at

Washington and his army of 11,000 men went into winter quarters at Valley Forge

Valley Forge was the winter encampment of the Continental Army, under the command of George Washington, during the American Revolutionary War. The Valley Forge encampment lasted six months, from December 19, 1777, to June 19, 1778. It was the t ...

north of Philadelphia in December 1777. There they lost between 2,000 and 3,000 men as a result of disease and lack of food, clothing, and shelter, reducing the army to below 9,000 men. By February, Washington was facing low troop morale and increased desertions. An internal revolt by his officers prompted some members of Congress to consider removing Washington from command. Washington's supporters resisted, and the matter was ultimately dropped.

Washington made repeated petitions to Congress for provisions and expressed the urgency of the situation to a congressional delegation. Congress agreed to strengthen the army's supply lines and reorganize the quartermaster

Quartermaster is a military term, the meaning of which depends on the country and service. In land army, armies, a quartermaster is an officer who supervises military logistics, logistics and requisitions, manages stores or barracks, and distri ...

and commissary

A commissary is a government official charged with oversight or an ecclesiastical official who exercises in special circumstances the jurisdiction of a bishop.

In many countries, the term is used as an administrative or police title. It often c ...

departments, while Washington launched the Grand Forage of 1778 to collect food from the surrounding region. Meanwhile, Baron Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben

Friedrich Wilhelm August Heinrich Ferdinand Freiherr von Steuben ( , ; born Friedrich Wilhelm Ludolf Gerhard Augustin Louis Freiherr von Steuben; September 17, 1730 – November 28, 1794), also referred to as Baron von Steuben, was a German-b ...

's incessant drilling transformed Washington's recruits into a disciplined fighting force. Washington appointed him Inspector General.

In early 1778, the French entered into a Treaty of Alliance with the Americans. In May, Howe resigned and was replaced by Sir Henry Clinton. The British evacuated Philadelphia for New York that June and Washington summoned a war council of American and French generals. He chose to order a limited strike on the retreating British. Generals Lee and Lafayette moved with 4,000 men, without Washington's knowledge, and bungled their first strike on June 28. Washington relieved Lee and achieved a draw after an expansive battle. The British continued their retreat to New York.

This battle "marked the end of the war's campaigning in the northern and middle states. Washington would not fight the British in a major engagement again for more than three years". British attention shifted to the Southern theatre; in late 1778, General Clinton captured Savannah, Georgia

Savannah ( ) is the oldest city in the U.S. state of Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia and the county seat of Chatham County, Georgia, Chatham County. Established in 1733 on the Savannah River, the city of Savannah became the Kingdom of Great Brita ...

, a key port in the American South. Washington, meanwhile, ordered an expedition against the Iroquois

The Iroquois ( ), also known as the Five Nations, and later as the Six Nations from 1722 onwards; alternatively referred to by the Endonym and exonym, endonym Haudenosaunee ( ; ) are an Iroquoian languages, Iroquoian-speaking Confederation#Ind ...

, the Indigenous allies of the British, destroying their villages.

Espionage and West Point

Washington became America's first spymaster

A spymaster is a leader of a group of spies or an intelligence agency

An intelligence agency is a government agency responsible for the collection, Intelligence analysis, analysis, and exploitation of information in support of law enforce ...

by designing an espionage system against the British. In 1778, Major Benjamin Tallmadge

Benjamin Tallmadge (February 25, 1754 – March 7, 1835) was an American military officer, spymaster, and politician. He is best known for his service as an officer in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War. He acted as lead ...

formed the Culper Ring

The Culper Ring was a network of Espionage, spies active during the American Revolutionary War, organized by Major Benjamin Tallmadge and General George Washington in 1778 during the British New York and New Jersey campaign, occupation of New Yo ...

at Washington's direction to covertly collect information about the British in New York. Intelligence from the Culper Ring saved French forces from a surprise British attack, which was itself based on intelligence from Washington's general turned British spy Benedict Arnold.

Washington had disregarded incidents of disloyalty by Arnold, who had distinguished himself in many campaigns, including the invasion of Quebec. In 1779, Arnold began supplying the British spymaster John André

Major John André (May 2, 1750 – October 2, 1780) was a British Army officer who served as the head of Britain's intelligence operations during the American War for Independence. In September 1780, he negotiated with Continental Army offic ...

with sensitive information intended to allow the British to capture West Point

The United States Military Academy (USMA), commonly known as West Point, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York that educates cadets for service as Officer_(armed_forces)#United_States, comm ...

, a key American defensive position on the Hudson River. On September 21, Arnold gave André plans to take over the garrison. André was captured by militia who discovered the plans, after which Arnold escaped to New York. On being told about Arnold's treason, Washington recalled the commanders positioned under Arnold at key points around the fort to prevent any complicity. He assumed personal command at West Point and reorganized its defenses.

Southern theater and Yorktown

By June 1780, the British had occupied the South Carolina

By June 1780, the British had occupied the South Carolina Piedmont

Piedmont ( ; ; ) is one of the 20 regions of Italy, located in the northwest Italy, Northwest of the country. It borders the Liguria region to the south, the Lombardy and Emilia-Romagna regions to the east, and the Aosta Valley region to the ...

and had firm control of the South. Washington was reinvigorated, however, when Lafayette returned from France with more ships, men, and supplies, and 5,000 veteran French troops led by Marshal Rochambeau arrived at Newport, Rhode Island

Newport is a seaside city on Aquidneck Island in Rhode Island, United States. It is located in Narragansett Bay, approximately southeast of Providence, Rhode Island, Providence, south of Fall River, Massachusetts, south of Boston, and nort ...

in July.

General Clinton sent Arnold, now a British brigadier general, to Virginia in December with 1,700 troops to capture Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port city status in the United Kingdom, city and unitary authority in Hampshire, England. Most of Portsmouth is located on Portsea Island, off the south coast of England in the Solent, making Portsmouth the only city in En ...

and conduct raids on Patriot forces. Washington sent Lafayette south to counter Arnold's efforts. Washington initially hoped to bring the fight to New York, drawing the British forces away from Virginia and ending the war there, but Rochambeau advised him that Cornwallis

Charles Cornwallis, 1st Marquess Cornwallis (31 December 1738 – 5 October 1805) was a British Army officer, Whig politician and colonial administrator. In the United States and United Kingdom, he is best known as one of the leading Britis ...

in Virginia was the better target. On August 19, 1781, Washington and Rochambeau began a march to Yorktown, Virginia

Yorktown is a town in York County, Virginia, United States. It is the county seat of York County, one of the eight original shires formed in Colony of Virginia, colonial Virginia in 1682. Yorktown's population was 195 as of the 2010 census, while ...

, known now as the " celebrated march". Washington was in command of an army of 7,800 Frenchmen, 3,100 militia, and 8,000 Continental troops. Inexperienced in siege warfare, he often deferred to the judgment of Rochambeau. Despite this, Rochambeau never challenged Washington's authority as the battle's commanding officer.

By late September, Patriot-French forces surrounded Yorktown, trapping the British Army, while the French navy emerged victorious at the Battle of the Chesapeake

The Battle of the Chesapeake, also known as the Battle of the Virginia Capes or simply the Battle of the Capes, was a crucial naval battle in the American Revolutionary War that took place near the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay on 5 September 1 ...

. The final American offensive began with a shot fired by Washington. The siege ended with a British surrender on October 19, 1781; over 7,000 British soldiers became prisoners of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of war for a ...

. Washington negotiated the terms of surrender for two days, and the official signing ceremony took place on October 19. Although the peace treaty was not negotiated for two more years, Yorktown proved to be the last significant battle of the Revolutionary War, with the British Parliament agreeing to cease hostilities in March 1782.

Demobilization and resignation

When peace negotiations began in April 1782, both the British and French began gradually evacuating their forces. In March 1783, Washington successfully calmed the

When peace negotiations began in April 1782, both the British and French began gradually evacuating their forces. In March 1783, Washington successfully calmed the Newburgh Conspiracy

The Newburgh Conspiracy was a failed apparent threat by leaders of the Continental Army in March 1783, at the end of the American Revolutionary War. The Army's commander, George Washington, successfully calmed the soldiers and helped secure back ...

, a planned mutiny by American officers dissatisfied with a lack of pay.[ Washington submitted an account of $450,000 in expenses which he had advanced to the army. The account was settled, though it was vague about large sums and included expenses his wife had incurred through visits to his headquarters.

When the Treaty of Paris was signed on September 3, 1783, Britain officially recognized American independence. Washington disbanded his army, giving a farewell address to his soldiers on November 2. He oversaw the evacuation of British forces in New York and was greeted by parades and celebrations.

In early December 1783, Washington bade farewell to his officers at ]Fraunces Tavern

Fraunces Tavern is a museum and restaurant in New York City, situated at 54 Pearl Street at the corner of Broad Street in the Financial District of Lower Manhattan. The location played a prominent role in history before, during, and after th ...

and resigned as commander-in-chief soon after. In a final appearance in uniform, he gave a statement to the Congress: "I consider it an indispensable duty to close this last solemn act of my official life, by commending the interests of our dearest country to the protection of Almighty God, and those who have the superintendence of them, to His holy keeping." Washington's resignation was acclaimed at home and abroad, "extolled by later historians as a signal event that set the country's political course" according to the historian Edward J. Larson. The same month, Washington was appointed president-general of the Society of the Cincinnati

The Society of the Cincinnati is a lineage society, fraternal, hereditary society founded in 1783 to commemorate the American Revolutionary War that saw the creation of the United States. Membership is largely restricted to descendants of milita ...

, a newly established hereditary fraternity of Revolutionary War officers.

Early republic (1783–1789)

Return to Mount Vernon

After spending just ten days at Mount Vernon out of years of war, Washington was eager to return home. He arrived on Christmas Eve; Professor John E. Ferling wrote that he was delighted to be "free of the bustle of a camp and the busy scenes of public life". He received a constant stream of visitors paying their respects at Mount Vernon.

Washington reactivated his interests in the Great Dismal Swamp

The Great Dismal Swamp is a large swamp in the Coastal Plain Region of southeastern Virginia and northeastern North Carolina in the eastern United States, between Norfolk, Virginia, and Elizabeth City, North Carolina. It is located in parts of t ...

and Potomac Canal projects, begun before the war, though neither paid him any dividends. He undertook a 34-day, trip in 1784 to check on his land holdings in the Ohio Country. He oversaw the completion of remodeling work at Mount Vernon, which transformed his residence into the mansion that survives to this day—although his financial situation was not strong. Creditors paid him in depreciated

In accountancy, depreciation refers to two aspects of the same concept: first, an actual reduction in the fair value of an asset, such as the decrease in value of factory equipment each year as it is used and wears, and second, the allocation i ...

wartime currency, and he owed significant amounts in taxes and wages. Mount Vernon had made no profit during his absence, and he saw persistently poor crop yields due to pestilence and bad weather. His estate recorded its eleventh year running at a deficit in 1787.

To make his estate profitable again, Washington undertook a new landscaping plan and succeeded in cultivating a range of fast-growing trees and native shrubs. He also began breeding mule

The mule is a domestic equine hybrid between a donkey, and a horse. It is the offspring of a male donkey (a jack) and a female horse (a mare). The horse and the donkey are different species, with different numbers of chromosomes; of the two ...

s after being gifted a stud

Stud may refer to:

Animals

* Stud (animal), an animal retained for breeding

** Stud farm, a property where livestock are bred

Arts and entertainment

* Stud (band), a British progressive rock group

* The Stud (bar), a gay bar in San Francisco

* ...

by King Charles III of Spain

Charles III (; 20 January 1716 – 14 December 1788) was King of Spain in the years 1759 to 1788. He was also Duke of Parma and Piacenza, as Charles I (1731–1735); King of Naples, as Charles VII; and King of Sicily, as Charles III (or V) (1735� ...

in 1785; he believed that they would revolutionize agriculture.

Constitutional Convention of 1787

Before returning to private life in June 1783, Washington called for a strong union. Though he was concerned that he might be criticized for meddling in civil matters, he sent a circular letter to the states, maintaining that the

Before returning to private life in June 1783, Washington called for a strong union. Though he was concerned that he might be criticized for meddling in civil matters, he sent a circular letter to the states, maintaining that the Articles of Confederation

The Articles of Confederation, officially the Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union, was an agreement and early body of law in the Thirteen Colonies, which served as the nation's first Constitution, frame of government during the Ameri ...

were no more than "a rope of sand". He believed the nation was on the verge of "anarchy and confusion", was vulnerable to foreign intervention, and that a national constitution would unify the states under a strong central government.

When Shays's Rebellion erupted in Massachusetts in August 1786, Washington was further convinced that a national constitution was needed.[ Some nationalists feared that the new republic had descended into lawlessness, and they met on September 11, 1786, at ]Annapolis

Annapolis ( ) is the capital of the U.S. state of Maryland. It is the county seat of Anne Arundel County and its only incorporated city. Situated on the Chesapeake Bay at the mouth of the Severn River, south of Baltimore and about east o ...

to ask the Congress to revise the Articles of Confederation. Congress agreed to a Constitutional Convention to be held in Philadelphia in 1787, with each state to send delegates. Washington was chosen to lead the Virginia delegation, but he declined. He had concerns about the legality of the convention and consulted James Madison

James Madison (June 28, 1836) was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. Madison was popularly acclaimed as the ...

, Henry Knox, and others. They persuaded him to attend as they felt his presence might induce reluctant states to send delegates and smooth the way for the ratification process while also giving legitimacy to the convention.

Washington arrived in Philadelphia on May 9, 1787, and the convention began on May 25. Benjamin Franklin nominated Washington to preside over the meeting, and he was unanimously elected. The delegate Edmund Randolph

Edmund Jennings Randolph (August 10, 1753 September 12, 1813) was a Founding Father of the United States, attorney, and the seventh Governor of Virginia. As a delegate from Virginia, he attended the Constitutional Convention and helped to cre ...

introduced Madison's Virginia Plan

The Virginia Plan (also known as the Randolph Plan or the Large-State Plan) was a proposed plan of government for the United States presented at the Constitutional Convention (United States), Constitutional Convention of 1787. The plan called fo ...

; it called for an entirely new constitution and a sovereign national government, which Washington highly recommended. However, details around representation were particularly contentious, resulting in a competing New Jersey Plan

The New Jersey Plan (also known as the Small State Plan or the Paterson Plan) was a proposal for the structure of the United States government presented during the Constitutional Convention of 1787. Principally authored by William Paterson of Ne ...

being brought forward. On July 10, Washington wrote to Alexander Hamilton: "I almost despair of seeing a favorable issue to the proceedings of our convention and do therefore repent having had any agency in the business." Nevertheless, he lent his prestige to the work of the other delegates, lobbying many to support the ratification of the Constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organization or other type of entity, and commonly determines how that entity is to be governed.

When these pri ...

. The final version adopted the Connecticut Compromise

The Connecticut Compromise, also known as the Great Compromise of 1787 or Sherman Compromise, was an agreement reached during the Constitutional Convention of 1787 that in part defined the legislative structure and representation each state ...

between the two plans, and was signed by 39 of 55 delegates on September 17, 1787.

First presidential election

Just prior to the first presidential election of 1789, in 1788 Washington was appointed chancellor of the College of William & Mary

The chancellor of the College of William & Mary is the ceremonial head of the College of William & Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia, United States, chosen by the university's Board of Visitors. The office was created by the college's Royal Charte ...

. He continued to serve through his presidency until his death.

Presidency (1789–1797)

First term

Washington was inaugurated on April 30, 1789, taking the oath of office

An oath of office is an oath or affirmation a person takes before assuming the duties of an office, usually a position in government or within a religious body, although such oaths are sometimes required of officers of other organizations. Suc ...

at Federal Hall

Federal Hall was the first capitol building of the United States under the Constitution. Serving as the meeting place of the First United States Congress and the site of George Washington's first presidential inauguration, the building existe ...

in New York City. His coach was led by militia and a marching band and followed by statesmen and foreign dignitaries in an inaugural parade, with a crowd of 10,000. Robert R. Livingston administered the oath, using a Bible provided by the Masons. Washington read a speech in the Senate Chamber, asking "that Almighty Being ... consecrate the liberties and happiness of the people of the United States". Though he wished to serve without a salary, Congress insisted that he receive one,[ providing Washington $25,000 annually (compared to $5,000 annually for the vice president).

Washington wrote to James Madison: "As the first of everything in our situation will serve to establish a precedent, it is devoutly wished on my part that these precedents be fixed on true principles." To that end, he argued against the majestic titles proposed by the Senate, including "His Majesty" and "His Highness the President", in favor of "Mr. President". His executive precedents included the inaugural address, messages to Congress, and the cabinet form of the ]executive branch

The executive branch is the part of government which executes or enforces the law.

Function

The scope of executive power varies greatly depending on the political context in which it emerges, and it can change over time in a given country. In ...

. He also selected the first justices for the Supreme Court

In most legal jurisdictions, a supreme court, also known as a court of last resort, apex court, high (or final) court of appeal, and court of final appeal, is the highest court within the hierarchy of courts. Broadly speaking, the decisions of ...

.

Washington was an able administrator and judge of talent and character. The old Confederation

A confederation (also known as a confederacy or league) is a political union of sovereign states united for purposes of common action. Usually created by a treaty, confederations of states tend to be established for dealing with critical issu ...

lacked the powers to handle its workload and had weak leadership, no executive, a small bureaucracy of clerks, large debt, worthless paper money, and no power to establish taxes. Congress created executive departments in 1789, including the State Department

The United States Department of State (DOS), or simply the State Department, is an executive department of the U.S. federal government responsible for the country's foreign policy and relations. Equivalent to the ministry of foreign affairs o ...

, the War Department, and the Treasury Department. Washington appointed Edmund Randolph as Attorney General

In most common law jurisdictions, the attorney general (: attorneys general) or attorney-general (AG or Atty.-Gen) is the main legal advisor to the government. In some jurisdictions, attorneys general also have executive responsibility for law enf ...

, Samuel Osgood as Postmaster General

A Postmaster General, in Anglosphere countries, is the chief executive officer of the postal service of that country, a ministerial office responsible for overseeing all other postmasters.

History

The practice of having a government official ...

, Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (, 1743July 4, 1826) was an American Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was the primary author of the United States Declaration of Indepe ...

as Secretary of State, Henry Knox as Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of the ...

, and Alexander Hamilton as Secretary of the Treasury

The United States secretary of the treasury is the head of the United States Department of the Treasury, and is the chief financial officer of the federal government of the United States. The secretary of the treasury serves as the principal a ...

. Washington's cabinet became a consulting and advisory body, not mandated by the Constitution. Washington restricted cabinet discussions to topics of his choosing and expected department heads to agreeably carry out his decisions. He exercised restraint in using his veto power, writing that "I give my Signature to many Bills with which my Judgment is at variance."

Washington opposed political factionalism and remained non-partisan throughout his presidency (the only United States president to do so). He was sympathetic to a Federalist form of government. Washington's closest advisors formed two factions, portending the First Party System

The First Party System was the political party system in the United States between roughly 1792 and 1824. It featured two national parties competing for control of the presidency, Congress, and the states: the Federalist Party, created largel ...

. Hamilton formed the Federalist Party

The Federalist Party was a conservativeMultiple sources:

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

* and nationalist American political party and the first political party in the United States. It dominated the national government under Alexander Hamilton from 17 ...