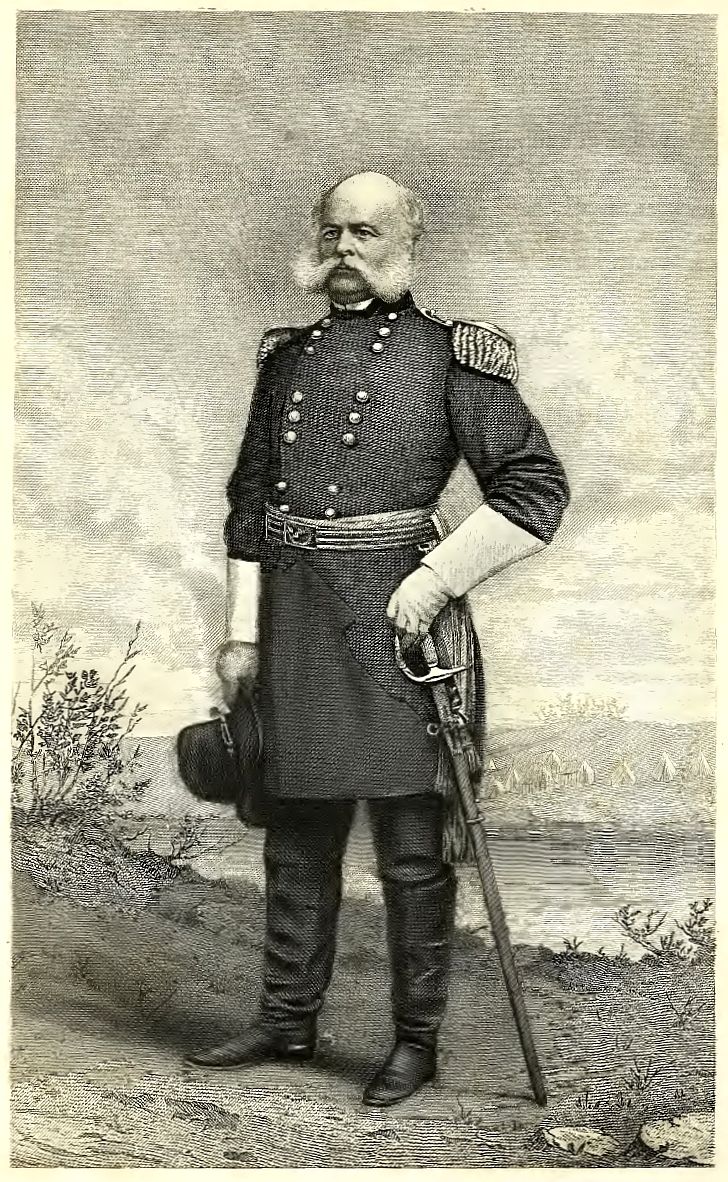

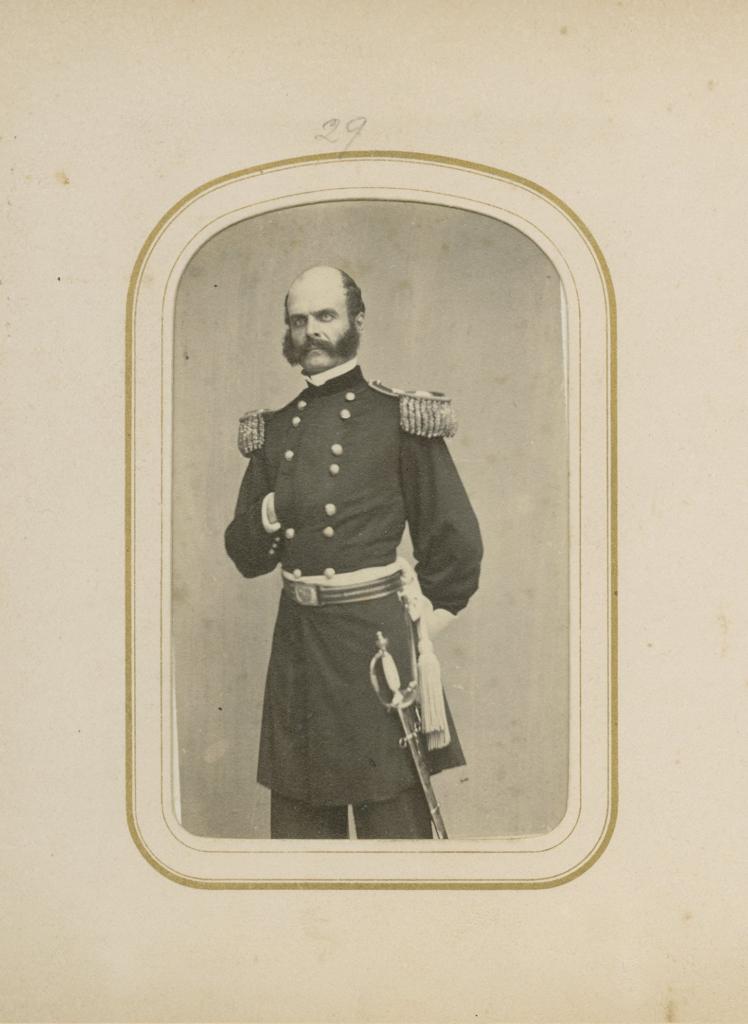

General Burnside on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Ambrose Everts Burnside (May 23, 1824 – September 13, 1881) was an American army officer and politician who became a senior Union

After McClellan failed to pursue General

After McClellan failed to pursue General

Burnside offered to resign his commission altogether but Lincoln declined, stating that there could still be a place for him in the army. Thus, he was placed back at the head of the IX Corps and sent to command the Department of the Ohio, encompassing the states of Ohio, Indiana, Kentucky, and Illinois. This was a quiet area with little activity, and the President reasoned that Burnside could not get himself into too much trouble there. However, antiwar sentiment was riding high in the Western states as they had traditionally carried on a great deal of commerce with the South, and there was little in the way of abolitionist sentiment there or a desire to fight for the purpose of ending slavery. Burnside was thoroughly disturbed by this trend and issued a series of orders forbidding "the expression of public sentiments against the war or the Administration" in his department; this finally climaxed with General Order No. 38, which declared that "any person found guilty of treason will be tried by a military tribunal and either imprisoned or banished to enemy lines".

On May 1, 1863, Ohio Congressman Clement L. Vallandigham, a prominent opponent of the war, held a large public rally in

Burnside offered to resign his commission altogether but Lincoln declined, stating that there could still be a place for him in the army. Thus, he was placed back at the head of the IX Corps and sent to command the Department of the Ohio, encompassing the states of Ohio, Indiana, Kentucky, and Illinois. This was a quiet area with little activity, and the President reasoned that Burnside could not get himself into too much trouble there. However, antiwar sentiment was riding high in the Western states as they had traditionally carried on a great deal of commerce with the South, and there was little in the way of abolitionist sentiment there or a desire to fight for the purpose of ending slavery. Burnside was thoroughly disturbed by this trend and issued a series of orders forbidding "the expression of public sentiments against the war or the Administration" in his department; this finally climaxed with General Order No. 38, which declared that "any person found guilty of treason will be tried by a military tribunal and either imprisoned or banished to enemy lines".

On May 1, 1863, Ohio Congressman Clement L. Vallandigham, a prominent opponent of the war, held a large public rally in

As the two armies faced the stalemate of

As the two armies faced the stalemate of

Burnside died suddenly of "neuralgia of the heart" (

Burnside died suddenly of "neuralgia of the heart" (

Burnside was noted for his unusual beard, joining strips of hair in front of his ears to his mustache but with the chin clean-shaven; the word ''burnsides'' was coined to describe this style. The syllables were later reversed to give '' sideburns''.

Burnside was noted for his unusual beard, joining strips of hair in front of his ears to his mustache but with the chin clean-shaven; the word ''burnsides'' was coined to describe this style. The syllables were later reversed to give '' sideburns''.

West Point website

* Goolrick, William K., and the Editors of Time-Life Books. ''Rebels Resurgent: Fredericksburg to Chancellorsville''. Alexandria, VA: Time-Life Books, 1985. . * Grimsley, Mark. ''And Keep Moving On: The Virginia Campaign, May–June 1864''. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2002. . * Korn, Jerry, and the Editors of Time-Life Books. ''The Fight for Chattanooga: Chickamauga to Missionary Ridge''. Alexandria, VA: Time-Life Books, 1985. . * McPherson, James M. '' Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era''. Oxford History of the United States. New York: Oxford University Press, 1988. . * Marvel, William. ''Burnside''. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1991. . * Mierka, Gregg A

"Rhode Island's Own."

MOLLUS biography. Accessed July 19, 2010. * Rhea, Gordon C. ''The Battles for Spotsylvania Court House and the Road to Yellow Tavern May 7–12, 1864''. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1997. . * Sauers, Richard A. "Ambrose Everett Burnside." In ''Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History'', edited by David S. Heidler and Jeanne T. Heidler. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2000. . * Sears, Stephen W. ''Landscape Turned Red: The Battle of Antietam''. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1983. . * * Warner, Ezra J. ''Generals in Blue: Lives of the Union Commanders''. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1964. . * Wert, Jeffry D. ''The Sword of Lincoln: The Army of the Potomac''. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2005. . * Wilson, James Grant, John Fiske and Stanley L. Klos, eds

"Ambrose Burnside." In ''Appleton's Cyclopedia of American Biography''

New Work: D. Appleton & Co., 1887–1889 and 1999.

at History of American Women

Ambrose E. Burnside in ''Encyclopedia Virginia''

Burnside's grave

()

{{DEFAULTSORT:Burnside, Ambrose 1824 births 1881 deaths 19th-century Rhode Island politicians 19th-century United States senators American militia generals American people of English descent American people of Irish descent Burials at Swan Point Cemetery Chairmen of the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations Grand Army of the Republic commanders-in-chief People from Liberty, Indiana People of Indiana in the American Civil War People of Rhode Island in the American Civil War Presidents of the National Rifle Association Republican Party United States senators from Rhode Island Republican Party governors of Rhode Island Union army generals United States Military Academy alumni

general

A general officer is an Officer (armed forces), officer of high rank in the army, armies, and in some nations' air force, air and space forces, marines or naval infantry.

In some usages, the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colone ...

in the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

and a three-time Governor of Rhode Island, as well as being a successful inventor and industrialist.

He achieved some of the earliest victories in the Eastern theater of the Civil War, but was then promoted above his abilities, and is mainly remembered for two disastrous defeats, at Fredericksburg (December 1862) and the Battle of the Crater (July 1864, during the Siege of Petersburg

The Richmond–Petersburg campaign was a series of battles around Petersburg, Virginia, fought from June 9, 1864, to March 25, 1865, during the American Civil War. Although it is more popularly known as the siege of Petersburg, it was not a c ...

). Although an inquiry cleared him of blame in the latter case, he never regained credibility as an army commander.

Burnside was a modest and unassuming individual, mindful of his limitations, who had been propelled to high command against his will. He could be described as a genuinely unlucky man, both in battle and in commerce (he was cheated of the profits of a successful cavalry firearm that had been his own invention). His spectacular growth of whiskers became known as " sideburns", deriving from the two syllables of his surname.

Early life

Burnside was born in Liberty, Indiana, and was the fourth of nine children of Edghill and Pamela (or Pamilia) Brown Burnside, a family of Scottish, Scotch-Irish and English origins. His great-great-grandfather Robert Burnside (1725–1775) was born in Scotland and settled in theProvince of South Carolina

The Province of South Carolina, originally known as Clarendon Province, was a province of the Kingdom of Great Britain that existed in North America from 1712 to 1776. It was one of the five Southern colonies and one of the Thirteen Colonies i ...

. His father was a native of South Carolina; he was a slave owner who freed his slaves when he relocated to Indiana. Ambrose attended Liberty Seminary as a young boy, but his education was interrupted when his mother died in 1841; he was apprenticed to a local tailor, eventually becoming a partner in the business.

As a young officer before the Civil War, Burnside was engaged to Charlotte "Lottie" Moon, who left him at the altar. When the minister asked if she took him as her husband, Moon is said to have shouted "No siree Bob!" before running out of the church. Moon is best known for her espionage for the Confederacy during the Civil War. Later, Burnside arrested Moon, her younger sister Virginia "Ginnie" Moon, and their mother. He kept them under house arrest for months but never charged them with espionage.

Early military career

He obtained an appointment to theUnited States Military Academy

The United States Military Academy (USMA), commonly known as West Point, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York that educates cadets for service as Officer_(armed_forces)#United_States, comm ...

in 1843 through his father's political connections and his own interest in military affairs. During his early tenure at the academy, a clerical error was made listing his middle name as Everett, rather than Everts. He graduated in 1847, ranking 18th in a class of 47, and was commissioned a brevet second lieutenant in the 2nd U.S. Artillery. He traveled to Veracruz

Veracruz, formally Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave, officially the Free and Sovereign State of Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave, is one of the 31 states which, along with Mexico City, comprise the 32 Political divisions of Mexico, Federal Entit ...

for the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War (Spanish language, Spanish: ''guerra de Estados Unidos-México, guerra mexicano-estadounidense''), also known in the United States as the Mexican War, and in Mexico as the United States intervention in Mexico, ...

, but he arrived after hostilities had ceased and performed mostly garrison duty around Mexico City

Mexico City is the capital city, capital and List of cities in Mexico, largest city of Mexico, as well as the List of North American cities by population, most populous city in North America. It is one of the most important cultural and finan ...

.Eicher, pp. 155–56; Sauers, pp. 327–28; Warner, pp. 57–58; Wilson, np.

At the close of the war, Lt. Burnside served two years on the western frontier under Captain Braxton Bragg

Braxton Bragg (March 22, 1817 – September 27, 1876) was an American army Officer (armed forces), officer during the Second Seminole War and Mexican–American War and Confederate General officers in the Confederate States Army, general in th ...

in the 3rd U.S. Artillery, a light artillery unit that had been converted to cavalry duty, protecting the Western mail routes through Nevada to California. In August 1849, he was wounded by an arrow in his neck during a skirmish against Apache

The Apache ( ) are several Southern Athabaskan language-speaking peoples of the Southwestern United States, Southwest, the Southern Plains and Northern Mexico. They are linguistically related to the Navajo. They migrated from the Athabascan ho ...

s in Las Vegas, New Mexico. He was promoted to 1st lieutenant on December 12, 1851.

In 1852, he was assigned to Fort Adams

Fort Adams is a former United States Army post in Newport, Rhode Island, Newport, Rhode Island, that was established on July 4, 1799, as a Seacoast defense in the United States#First System, First System Coastal defence and fortification, coas ...

, Newport, Rhode Island

Newport is a seaside city on Aquidneck Island in Rhode Island, United States. It is located in Narragansett Bay, approximately southeast of Providence, Rhode Island, Providence, south of Fall River, Massachusetts, south of Boston, and nort ...

, and he married Mary Richmond Bishop of Providence, Rhode Island

Providence () is the List of capitals in the United States, capital and List of municipalities in Rhode Island, most populous city of the U.S. state of Rhode Island. The county seat of Providence County, Rhode Island, Providence County, it is o ...

, on April 27 of that year. The marriage lasted until Mary's death in 1876, but was childless.Eicher, pp. 155–56; Mierka, np.; Warner, pp. 57–58.

In October 1853, Burnside resigned his commission in the United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the primary Land warfare, land service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is designated as the Army of the United States in the United States Constitution.Article II, section 2, clause 1 of th ...

and was appointed commander of the Rhode Island state militia with the rank of major general. He held this position for two years.

After leaving the Regular Army, Burnside devoted his time and energy to the manufacture of a firearm that bears his name: the Burnside carbine. President Buchanan's Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of the ...

John B. Floyd

John Buchanan Floyd (June 1, 1806 – August 26, 1863) was an American politician who served as the List of governors of Virginia, 31st Governor of Virginia. Under president James Buchanan, he also served as the U.S. Secretary of War from 1857 ...

contracted the Burnside Arms Company to equip a large portion of the Army with his carbine, mostly cavalry and induced him to establish extensive factories for its manufacture. The Bristol

Bristol () is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city, unitary authority area and ceremonial county in South West England, the most populous city in the region. Built around the River Avon, Bristol, River Avon, it is bordered by t ...

Rifle Works were no sooner complete than another gunmaker allegedly bribed Floyd to break his $100,000 contract with Burnside.

Burnside ran as a Democrat for one of the Congressional seats in Rhode Island in 1858 and was defeated in a landslide. The burdens of the campaign and the destruction by fire of his factory contributed to his financial ruin, and he was forced to assign his firearm patents to others. He then went west in search of employment and became treasurer of the Illinois Central Railroad

The Illinois Central Railroad , sometimes called the Main Line of Mid-America, is a railroad in the Central United States. Its primary routes connected Chicago, Illinois, with New Orleans, New Orleans, Louisiana, and Mobile, Alabama, and thus, ...

, where he worked for and became friendly with George B. McClellan

George Brinton McClellan (December 3, 1826 – October 29, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 24th governor of New Jersey and as Commanding General of the United States Army from November 1861 to March 186 ...

, who later became one of his commanding officers.Eicher, pp. 155–56; Mierka, np.; Sauers, pp. 327–28; Warner, pp. 57–58. Burnside became familiar with corporate attorney Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

, future president of the United States, during this time period.

Civil War

First Bull Run

At the outbreak of the Civil War, Burnside was acolonel

Colonel ( ; abbreviated as Col., Col, or COL) is a senior military Officer (armed forces), officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, a colon ...

in the Rhode Island Militia. He raised the 1st Rhode Island Volunteer Infantry Regiment, and was appointed its colonel on May 2, 1861. Two companies of this regiment were then armed with Burnside carbines.

Within a month, he ascended to brigade command in the Department of northeast Virginia. He commanded the brigade without distinction at the First Battle of Bull Run

The First Battle of Bull Run, called the Battle of First Manassas

. by Confederate States ...

in July and took over division command temporarily for wounded Brig. Gen. . by Confederate States ...

David Hunter

David Hunter (July 21, 1802 – February 2, 1886) was an American military officer. He served as a Union general during the American Civil War. He achieved notability for his unauthorized 1862 order (immediately rescinded) emancipating slaves ...

. His 90-day regiment was mustered out of service on August 2; he was promoted to brigadier-general of volunteers on August 6 and was assigned to train provisional brigades in the Army of the Potomac

The Army of the Potomac was the primary field army of the Union army in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was created in July 1861 shortly after the First Battle of Bull Run and was disbanded in June 1865 following the Battle of ...

.

North Carolina

Burnside commanded the Coast Division or North Carolina Expeditionary Force from September 1861 until July 1862, three brigades assembled inAnnapolis, Maryland

Annapolis ( ) is the capital of the U.S. state of Maryland. It is the county seat of Anne Arundel County and its only incorporated city. Situated on the Chesapeake Bay at the mouth of the Severn River, south of Baltimore and about east ...

, which formed the nucleus for his future IX Corps. He conducted a successful amphibious campaign that closed more than 80% of the North Carolina sea coast to Confederate shipping for the remainder of the war. This included the Battle of Elizabeth City, fought on February 10, 1862, on the Pasquotank River near Elizabeth City, North Carolina.

The participants were vessels of the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the naval warfare, maritime military branch, service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is the world's most powerful navy with the largest Displacement (ship), displacement, at 4.5 millio ...

's North Atlantic Blockading Squadron opposed by vessels of the Confederate Navy's Mosquito Fleet; the latter were supported by a shore-based battery of four guns at Cobb's Point (now called Cobb Point) near the southeastern border of the town. The battle was a part of the campaign in North Carolina that was led by Burnside and known as the Burnside Expedition. The result was a Union victory, with Elizabeth City and its nearby waters in their possession and the Confederate fleet captured, sunk, or dispersed.Mierka, np.

Burnside was promoted to major general of volunteers on March 18, 1862, in recognition of his successes at the battles of Roanoke Island and New Bern

New Bern, formerly Newbern, is a city in Craven County, North Carolina, United States, and its county seat. It had a population of 31,291 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census. It is located at the confluence of the Neuse River, Neuse a ...

, the first significant Union victories in the Eastern Theater. In July, his forces were transported north to Newport News, Virginia

Newport News () is an Independent city (United States), independent city in southeastern Virginia, United States. At the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, the population was 186,247. Located in the Hampton Roads region, it is the List of c ...

, and became the IX Corps of the Army of the Potomac.

Burnside was offered command of the Army of the Potomac following Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan's failure in the Peninsula Campaign

The Peninsula campaign (also known as the Peninsular campaign) of the American Civil War was a major Union operation launched in southeastern Virginia from March to July 1862, the first large-scale offensive in the Eastern Theater. The oper ...

. He refused this opportunity because of his loyalty to McClellan and the fact that he understood his own lack of military experience, and detached part of his corps in support of Maj. Gen. John Pope's Army of Virginia in the Northern Virginia Campaign. He received telegrams at this time from Maj. Gen. Fitz John Porter which were extremely critical of Pope's abilities as a commander, and he forwarded on to his superiors in concurrence. This episode later played a significant role in Porter's court-martial, in which Burnside appeared as a witness.

Burnside again declined command following Pope's debacle at Second Bull Run.Sauers, pp. 327–28; Wilson, np.

Antietam

Burnside was given command of the Right Wing of the Army of the Potomac (the I Corps and his own IX Corps) at the start of theMaryland Campaign

The Maryland campaign (or Antietam campaign) occurred September 4–20, 1862, during the American Civil War. The campaign was Confederate States Army, Confederate General (CSA), General Robert E. Lee's first invasion of the Northern United Stat ...

for the Battle of South Mountain

The Battle of South Mountain, known in several early Southern United States, Southern accounts as the Battle of Boonsboro Gap, was fought on September 14, 1862, as part of the Maryland campaign of the American Civil War. Three pitched battles ...

, but McClellan separated the two corps at the Battle of Antietam

The Battle of Antietam ( ), also called the Battle of Sharpsburg, particularly in the Southern United States, took place during the American Civil War on September 17, 1862, between Confederate General Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virgi ...

, placing them on opposite ends of the Union battle line and returning Burnside to command of just the IX Corps. Burnside implicitly refused to give up his authority and acted as though the corps commander was first Maj. Gen. Jesse L. Reno (killed at South Mountain) and then Brig. Gen. Jacob D. Cox, funneling orders through them to the corps. This cumbersome arrangement contributed to his slowness in attacking and crossing what is now called Burnside's Bridge

Burnside's Bridge is a landmark on the U.S. Civil War Antietam National Battlefield near Sharpsburg, northwestern Maryland. Built in 1836, it played a notable role in the 1862 battle.

History

Construction

Seeking to improve connections ...

on the southern flank of the Union line.

Burnside did not perform an adequate reconnaissance of the area, and he did not take advantage of several easy fording sites out of range of the enemy; his troops were forced into repeated assaults across the narrow bridge, which was dominated by Confederate sharpshooters on the high ground. By noon, McClellan was losing patience. He sent a succession of couriers to motivate Burnside to move forward, ordering one aide, "Tell him if it costs 10,000 men he must go now." He further increased the pressure by sending his inspector general to confront Burnside, who reacted indignantly: "McClellan appears to think I am not trying my best to carry this bridge; you are the third or fourth one who has been to me this morning with similar orders." The IX Corps eventually broke through, but the delay allowed Maj. Gen. A. P. Hill

Ambrose Powell Hill Jr. (November 9, 1825April 2, 1865) was a Confederate States Army, Confederate General officer, general who was killed in the American Civil War. He is usually referred to as A. P. Hill to differentiate him from Confederate ge ...

's Confederate division to come up from Harpers Ferry

Harpers Ferry is a historic town in Jefferson County, West Virginia, United States. The population was 269 at the 2020 United States census. Situated at the confluence of the Potomac River, Potomac and Shenandoah River, Shenandoah Rivers in the ...

and repulse the Union breakthrough. McClellan refused Burnside's requests for reinforcements, and the battle ended in a tactical stalemate.

Fredericksburg

After McClellan failed to pursue General

After McClellan failed to pursue General Robert E. Lee

Robert Edward Lee (January 19, 1807 – October 12, 1870) was a general officers in the Confederate States Army, Confederate general during the American Civil War, who was appointed the General in Chief of the Armies of the Confederate ...

's retreat from Antietam, Lincoln ordered McClellan's removal on November 5, 1862, and selected Burnside to replace him on November 7, 1862. Burnside reluctantly obeyed this order, the third such in his brief career, in part because the courier told him that, if he refused it, the command would go instead to Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker, whom Burnside

disliked. Burnside assumed charge of the Army of the Potomac in a change of command ceremony at the farm of Julia Claggett in New Baltimore, Virginia. McClellan visited troops to bid them farewell. Columbia Claggett, Julia Claggett's daughter-in-law, testified after the war that a "parade and transfer of the Army to Gen. Burnside took place on our farm in front of our house in a change of command ceremony at New Baltimore, Virginia on November 9, 1862."

President Abraham Lincoln pressured Burnside to take aggressive action and approved his plan on November 14 to capture the Confederate capital at Richmond, Virginia

Richmond ( ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital city of the Commonwealth (U.S. state), U.S. commonwealth of Virginia. Incorporated in 1742, Richmond has been an independent city (United States), independent city since 1871. ...

. This plan led to a humiliating and costly Union defeat at the Battle of Fredericksburg

The Battle of Fredericksburg was fought December 11–15, 1862, in and around Fredericksburg, Virginia, in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. The combat between the Union Army, Union Army of the Potomac commanded by Major general ( ...

on December 13. His advance upon Fredericksburg was rapid, but the attack was delayed when the engineers were slow to marshal pontoon bridges for crossing the Rappahannock River

The Rappahannock River is a river in eastern Virginia, in the United States, approximately in length.U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map accessed April 1, 2011 It traverses the enti ...

, as well as his own reluctance to deploy portions of his army across fording points. This allowed Gen. Lee to concentrate along Marye's Heights just west of town and easily repulse the Union attacks.

Assaults south of town were also mismanaged, which were supposed to be the main avenue of attack, and initial Union breakthroughs went unsupported. Burnside was upset by the failure of his plan and by the enormous casualties of his repeated, futile frontal assaults, and declared that he would personally lead an assault by the IX corps. His corps commanders talked him out of it, but relations were strained between the general and his subordinates. Accepting full blame, he offered to retire from the U.S. Army, but this was refused. Burnside's detractors labeled him the "Butcher of Fredericksburg".

In January 1863, Burnside launched a second offensive against Lee, but it bogged down in winter rains before anything was accomplished, and has derisively been called the Mud March. In its wake, he asked that several openly insubordinate officers be relieved of duty and court-martial

A court-martial (plural ''courts-martial'' or ''courts martial'', as "martial" is a postpositive adjective) is a military court or a trial conducted in such a court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of members of the arme ...

ed; he also offered to resign. Lincoln quickly accepted the latter option, and on January 26 replaced Burnside with Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker

Joseph Hooker (November 13, 1814 – October 31, 1879) was an American Civil War general for the Union, chiefly remembered for his decisive defeat by Confederate General Robert E. Lee at the Battle of Chancellorsville in 1863.

Hooker had serv ...

, one of the officers who had conspired against him.Wilson, np.; Warner, p. 58; Sauers, p. 328.

East Tennessee

Burnside offered to resign his commission altogether but Lincoln declined, stating that there could still be a place for him in the army. Thus, he was placed back at the head of the IX Corps and sent to command the Department of the Ohio, encompassing the states of Ohio, Indiana, Kentucky, and Illinois. This was a quiet area with little activity, and the President reasoned that Burnside could not get himself into too much trouble there. However, antiwar sentiment was riding high in the Western states as they had traditionally carried on a great deal of commerce with the South, and there was little in the way of abolitionist sentiment there or a desire to fight for the purpose of ending slavery. Burnside was thoroughly disturbed by this trend and issued a series of orders forbidding "the expression of public sentiments against the war or the Administration" in his department; this finally climaxed with General Order No. 38, which declared that "any person found guilty of treason will be tried by a military tribunal and either imprisoned or banished to enemy lines".

On May 1, 1863, Ohio Congressman Clement L. Vallandigham, a prominent opponent of the war, held a large public rally in

Burnside offered to resign his commission altogether but Lincoln declined, stating that there could still be a place for him in the army. Thus, he was placed back at the head of the IX Corps and sent to command the Department of the Ohio, encompassing the states of Ohio, Indiana, Kentucky, and Illinois. This was a quiet area with little activity, and the President reasoned that Burnside could not get himself into too much trouble there. However, antiwar sentiment was riding high in the Western states as they had traditionally carried on a great deal of commerce with the South, and there was little in the way of abolitionist sentiment there or a desire to fight for the purpose of ending slavery. Burnside was thoroughly disturbed by this trend and issued a series of orders forbidding "the expression of public sentiments against the war or the Administration" in his department; this finally climaxed with General Order No. 38, which declared that "any person found guilty of treason will be tried by a military tribunal and either imprisoned or banished to enemy lines".

On May 1, 1863, Ohio Congressman Clement L. Vallandigham, a prominent opponent of the war, held a large public rally in Mount Vernon, Ohio

Mount Vernon is a city in Knox County, Ohio, United States, and its county seat. It is located along the Kokosing River, northeast of Columbus, Ohio, Columbus. The population was 16,956 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census.

History

Th ...

in which he denounced President Lincoln as a "tyrant" who sought to abolish the Constitution and set up a dictatorship. Burnside had dispatched several agents to the rally who took down notes and brought back their "evidence" to the general, who then declared that it was sufficient grounds to arrest Vallandigham for treason. A military court tried him and found him guilty of violating General Order No. 38, despite his protests that he was expressing his opinions publicly. Vallandigham was sentenced to imprisonment for the duration of the war and was turned into a martyr by antiwar Democrats. Burnside next turned his attention to Illinois, where the Chicago ''Times'' newspaper had been printing antiwar editorials for months. The general dispatched a squadron of troops to the paper's offices and ordered them to cease printing.

Lincoln had not been asked or informed about either Vallandigham's arrest or the closure of the Chicago ''Times''. He remembered the section of General Order No. 38 which declared that offenders would be banished to enemy lines and finally decided that it was a good idea so Vallandigham was freed from jail and sent to Confederate hands. Meanwhile, Lincoln ordered the Chicago ''Times'' to be reopened and announced that Burnside had exceeded his authority in both cases. The President then issued a warning that generals were not to arrest civilians or close down newspapers again without the White House's permission.

Burnside also dealt with Confederate raiders such as John Hunt Morgan.

In the Knoxville Campaign, Burnside advanced to Knoxville, Tennessee

Knoxville is a city in Knox County, Tennessee, United States, and its county seat. It is located on the Tennessee River and had a population of 190,740 at the 2020 United States census. It is the largest city in the East Tennessee Grand Division ...

, first bypassing the Confederate-held Cumberland Gap and ultimately occupying Knoxville unopposed; he then sent troops back to the Cumberland Gap. Confederate commander Brig. Gen. John W. Frazer refused to surrender in the face of two Union brigades but Burnside arrived with a third, forcing the surrender of Frazer and 2,300 Confederates.

Union Maj. Gen. William S. Rosecrans was defeated at the Battle of Chickamauga, and Burnside was pursued by Lt. Gen. James Longstreet

James Longstreet (January 8, 1821January 2, 1904) was a General officers in the Confederate States Army, Confederate general during the American Civil War and was the principal subordinate to General Robert E. Lee, who called him his "Old War Ho ...

, against whose troops he had battled at Marye's Heights. Burnside skillfully outmaneuvered Longstreet at the Battle of Campbell's Station and was able to reach his entrenchments and safety in Knoxville, where he was briefly besieged until the Confederate defeat at the Battle of Fort Sanders outside the city. Tying down Longstreet's corps at Knoxville contributed to Gen. Braxton Bragg's defeat by Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was the 18th president of the United States, serving from 1869 to 1877. In 1865, as Commanding General of the United States Army, commanding general, Grant led the Uni ...

at Chattanooga

Chattanooga ( ) is a city in Hamilton County, Tennessee, United States, and its county seat. It is located along the Tennessee River and borders Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia to the south. With a population of 181,099 in 2020, it is Tennessee ...

. Troops under Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman

William is a masculine given name of Germanic origin. It became popular in England after the Norman conquest in 1066,All Things William"Meaning & Origin of the Name"/ref> and remained so throughout the Middle Ages and into the modern era. It is ...

marched to Burnside's aid, but the siege had already been lifted; Longstreet withdrew, eventually returning to Virginia.

Overland Campaign

Burnside was ordered to take the IX Corps back to the Eastern Theater, where he built it up to a strength of over 21,000 in Annapolis, Maryland. The IX Corps fought in theOverland Campaign

The Overland Campaign, also known as Grant's Overland Campaign and the Wilderness Campaign, was a series of battles fought in Virginia during May and June 1864, towards the end of the American Civil War. Lieutenant general (United States), Lt. G ...

of May 1864 as an independent command, reporting initially to Grant; his corps was not assigned to the Army of the Potomac because Burnside outranked its commander Maj. Gen. George G. Meade, who had been a division commander under Burnside at Fredericksburg. This cumbersome arrangement was rectified on May 24 just before the Battle of North Anna

The Battle of North Anna was fought May 23–26, 1864, as part of Union Army, Union Lieutenant General (United States), Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant's Overland Campaign against Confederate States Army, Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee's Army of North ...

, when Burnside agreed to waive his precedence of rank and was placed under Meade's direct command.

Burnside fought at the battles of Wilderness

Wilderness or wildlands (usually in the plurale tantum, plural) are Earth, Earth's natural environments that have not been significantly modified by human impact on the environment, human activity, or any urbanization, nonurbanized land not u ...

and Spotsylvania Court House, where he did not perform in a distinguished manner, attacking piecemeal and appearing reluctant to commit his troops to the costly frontal assaults that characterized these battles. After North Anna and Cold Harbor

The Battle of Cold Harbor was fought during the American Civil War near Mechanicsville, Virginia, from May 31 to June 12, 1864, with the most significant fighting occurring on June 3. It was one of the final battles of Union Army, Union Lieuten ...

, he took his place in the siege lines at Petersburg.

The Crater

As the two armies faced the stalemate of

As the two armies faced the stalemate of trench warfare

Trench warfare is a type of land warfare using occupied lines largely comprising Trench#Military engineering, military trenches, in which combatants are well-protected from the enemy's small arms fire and are substantially sheltered from a ...

at Petersburg in July 1864, Burnside agreed to a plan suggested by a regiment of former coal miners in his corps, the 48th Pennsylvania: to dig a mine under a fort named Elliot's Salient in the Confederate entrenchments and ignite explosives there to achieve a surprise breakthrough. The fort was destroyed on July 30 in what is known as the Battle of the Crater.

Because of interference from Meade, Burnside was ordered, only hours before the infantry attack, not to use his division of black troops, which had been specially trained for the assault: instead, he was forced to use untrained white troops. He could not decide which division to choose as a replacement, so he had his three subordinate commanders draw lots.

The division chosen by chance was that commanded by Brig. Gen. James H. Ledlie, who had failed to brief the men on what was expected of them, and was observed to be drinking liquor with Brig. Gen Edward Ferrero in a bombproof shelter well behind the lines during the battle, providing no leadership at all.

As a result, Ledlie's men entered the huge crater instead of going around it, became trapped, and were subjected to heavy fire from Confederates around the rim, resulting in high casualties. in the end his forces suffered 3,800 casualties Chernow, 2017, pp. 426-429

As a result of the Crater fiasco, Burnside was relieved of command on August 14 and sent on "extended leave" by Grant. He was never recalled to duty for the remainder of the war. A court of inquiry later placed the blame for the defeat on Burnside, Ledlie and Ferrero. In December, Burnside met with President Lincoln and General Grant about his future. He was contemplating resignation, but Lincoln and Grant requested that he remain in the Army. At the end of the interview, Burnside wrote, "I was not informed of any duty upon which I am to be placed." He finally resigned his commission on April 15, 1865, after Lee's surrender at Appomattox.

The United States Congress Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War later exonerated Burnside and placed the blame for the Union defeat at the Crater on General Meade for requiring the specially trained USCT (United States Colored Troops) men to be withdrawn.

Postbellum career

After his resignation, Burnside was employed in numerous railroad and industrial directorships, including the presidencies of the Cincinnati and Martinsville Railroad, the Indianapolis and Vincennes Railroad, the Cairo and Vincennes Railroad, and the Rhode Island Locomotive Works. He was elected to three one-year terms as Governor of Rhode Island, serving from May 29, 1866, to May 25, 1869. He was nominated by the Republican Party to be their candidate for governor in March 1866, and Burnside was elected governor in a landslide on April 4, 1866. This began Burnside's political career as a Republican, as he had been a Democrat before the war. Burnside was a Companion of the Massachusetts Commandery of theMilitary Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States

The Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States (MOLLUS), or, simply, the Loyal Legion, is a United States military order organized on April 15, 1865, by three veteran officers of the Union Army. The original membership was consisted ...

, a military society of Union officers and their descendants, and served as the Junior Vice Commander of the Massachusetts Commandery in 1869. He was commander-in-chief of the Grand Army of the Republic

The Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) was a fraternal organization composed of veterans of the Union Army (United States Army), Union Navy (United States Navy, U.S. Navy), and the United States Marine Corps, Marines who served in the American Ci ...

(GAR) veterans' association from 1871 to 1872, and also served as the Commander of the Department of Rhode Island of the GAR.Eicher, pp. 155–56. At its inception in 1871, the National Rifle Association of America chose him as its first president.

During a visit to Europe in 1870, Burnside attempted to mediate between the French and the Germans in the Franco-Prussian War

The Franco-Prussian War or Franco-German War, often referred to in France as the War of 1870, was a conflict between the Second French Empire and the North German Confederation led by the Kingdom of Prussia. Lasting from 19 July 1870 to 28 Janua ...

. He was registered at the offices of Drexel, Harjes & Co., Geneva, week ending November 5, 1870. Drexel Harjes was a major lender to the new French government after the war, helping it to repay its massive war reparations

War reparations are compensation payments made after a war by one side to the other. They are intended to cover damage or injury inflicted during a war. War reparations can take the form of hard currency, precious metals, natural resources, in ...

.

In 1876 Burnside was elected as commander of the New England Battalion of the Centennial Legion, the title of a collection of 13 militia units from the original 13 states, which participated in the parade in Philadelphia on July 4, 1876, to mark the centennial of the signing of the Declaration of Independence

A declaration of independence is an assertion by a polity in a defined territory that it is independent and constitutes a state. Such places are usually declared from part or all of the territory of another state or failed state, or are breaka ...

.

In 1874 Burnside was elected by the Rhode Island Senate as a U.S. Senator from Rhode Island, was re-elected in 1880, and served until his death in 1881. Burnside continued his association with the Republican Party, playing a prominent role in military affairs as well as serving as chairman of the Foreign Relations Committee in 1881.Wilson, np.; Eicher, p. 156.

Death and burial

Burnside died suddenly of "neuralgia of the heart" (

Burnside died suddenly of "neuralgia of the heart" (angina pectoris

Angina, also known as angina pectoris, is chest pain or pressure, usually caused by insufficient blood flow to the heart muscle (myocardium). It is most commonly a symptom of coronary artery disease.

Angina is typically the result of part ...

) on the morning of September 13, 1881, at his home in Bristol, Rhode Island, accompanied only by his doctor and family servants.

Burnside's body lay in state at City Hall

In local government, a city hall, town hall, civic centre (in the UK or Australia), guildhall, or municipal hall (in the Philippines) is the chief administrative building of a city, town, or other municipality. It usually houses the city o ...

until his funeral on September 16. A procession took his casket, in a hearse drawn by four black horses, to the First Congregational Church for services which were attended by many local dignitaries. Following the services, the procession made its way to Swan Point Cemetery for burial. Businesses and mills were closed for much of the day, and "thousands" of mourners from "all towns of the state and many places in Massachusetts and Connecticut" crowded the streets of Providence for the occasion.

Assessment and legacy

Personally, Burnside was always very popular, both in the army and in politics. He made friends easily, smiled a lot, and remembered everyone's name. His professional military reputation, however, was less positive, and he was known for being obstinate, unimaginative, and unsuited both intellectually and emotionally for high command.Goolrick, p. 29. Grant stated that he was "unfitted" for the command of an army and that no one knew this better than Burnside himself. Knowing his capabilities, he twice refused command of the Army of the Potomac, accepting only the third time when the courier told him that otherwise the command would go to Joseph Hooker. Jeffry D. Wert described Burnside's relief after Fredericksburg in a passage that sums up his military career:Bruce Catton

Charles Bruce Catton (October 9, 1899 – August 28, 1978) was an American historian and journalist, known best for his books concerning the American Civil War. Known as a narrative historian, Catton specialized in popular history, featuring in ...

summarized Burnside:

Sideburns

Burnside was noted for his unusual beard, joining strips of hair in front of his ears to his mustache but with the chin clean-shaven; the word ''burnsides'' was coined to describe this style. The syllables were later reversed to give '' sideburns''.

Burnside was noted for his unusual beard, joining strips of hair in front of his ears to his mustache but with the chin clean-shaven; the word ''burnsides'' was coined to describe this style. The syllables were later reversed to give '' sideburns''.

Honors

* In 1866, Allison Township inLapeer County, Michigan

Lapeer County ( ') is a County (United States), county located in the U.S. state of Michigan. As of the 2020 United States census, 2020 Census, the population was 88,619. The county seat is Lapeer, Michigan, Lapeer. The county was created on S ...

, was renamed Burnside Township to honor Ambrose Burnside.

* An equestrian statue

An equestrian statue is a statue of a rider mounted on a horse, from the Latin ''eques'', meaning 'knight', deriving from ''equus'', meaning 'horse'. A statue of a riderless horse is strictly an equine statue. A full-sized equestrian statue is a ...

designed by Launt Thompson

Launt Thompson (February 8, 1833 – September 26, 1894) was an American sculptor.

Biography

He was born in Abbeyleix, Ireland. Due to the Great Famine occurring in Ireland at the time, he emigrated to the United States in 1847 with his widowe ...

, a New York sculptor, was dedicated in 1887 at Exchange Place in Providence, facing City Hall. In 1906, the statue was moved to City Hall Park, which was re-dedicated as Burnside Park.

* Bristol, Rhode Island

Bristol is a town in Bristol County, Rhode Island, United States, as well as the county seat. The population of Bristol was 22,493 at the 2020 census. It is a deep water seaport named after Bristol, England. Major industries include boat buil ...

, has a small street named for Burnside.

* The Burnside Memorial Hall in Bristol, Rhode Island, is a two-story Richardson Romanesque public building on Hope Street. It was dedicated in 1883 by President Chester A. Arthur and Governor Augustus O. Bourn. Originally, a statue of Burnside was intended to be the focus of the porch. The architect was Stephen C. Earle.

* Burnside, Kentucky

Burnside is a home rule-class city in Pulaski County, Kentucky, United States. The population was 611 at the 2010 census. In 2004, Burnside became the only town in Pulaski County or any adjoining county to allow the sale of alcoholic beverages ...

, in south-central Kentucky, is a small town south of Somerset named for the former site of Camp Burnside, near the former Cumberland River town of Point Isabelle.

* New Burnside, Illinois, along the Cairo and Vincennes Railroad, was named after the former general for his role in founding the village through directorship of the new rail line.

* Burnside Residence Hall at the University of Rhode Island

The University of Rhode Island (URI) is a public land-grant research university with its main campus in Kingston, Rhode Island, United States. It is the flagship public research as well as the land-grant university of Rhode Island. The univer ...

in Kingston was opened in 1966.

* Burnside, Wisconsin is named for the general.

Portrayals

* Burnside was portrayed by Alex Hyde-White in Ronald F. Maxwell's 2003 film '' Gods and Generals'', which includes the Battle of Fredericksburg.See also

* List of American Civil War generals (Union) *List of United States Congress members who died in office (1790–1899)

The following is a list of United States United States Senate, senators and United States House of Representatives, representatives who died of natural or accidental causes, or who killed themselves, while serving their terms between 1790 and 18 ...

Citations

Bibliography

* Bailey, Ronald H., and the Editors of Time-Life Books. ''The Bloodiest Day: The Battle of Antietam''. Alexandria, VA: Time-Life Books, 1984. . * Catton, Bruce. ''Mr. Lincoln's Army''. Garden City, NY: Doubleday and Company, 1951. . * * Eicher, John H., and David J. Eicher. ''Civil War High Commands''. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2001. . * Esposito, Vincent J. ''West Point Atlas of American Wars''. New York: Frederick A. Praeger, 1959. . The collection of maps (without explanatory text) is available online at thWest Point website

* Goolrick, William K., and the Editors of Time-Life Books. ''Rebels Resurgent: Fredericksburg to Chancellorsville''. Alexandria, VA: Time-Life Books, 1985. . * Grimsley, Mark. ''And Keep Moving On: The Virginia Campaign, May–June 1864''. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2002. . * Korn, Jerry, and the Editors of Time-Life Books. ''The Fight for Chattanooga: Chickamauga to Missionary Ridge''. Alexandria, VA: Time-Life Books, 1985. . * McPherson, James M. '' Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era''. Oxford History of the United States. New York: Oxford University Press, 1988. . * Marvel, William. ''Burnside''. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1991. . * Mierka, Gregg A

"Rhode Island's Own."

MOLLUS biography. Accessed July 19, 2010. * Rhea, Gordon C. ''The Battles for Spotsylvania Court House and the Road to Yellow Tavern May 7–12, 1864''. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1997. . * Sauers, Richard A. "Ambrose Everett Burnside." In ''Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History'', edited by David S. Heidler and Jeanne T. Heidler. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2000. . * Sears, Stephen W. ''Landscape Turned Red: The Battle of Antietam''. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1983. . * * Warner, Ezra J. ''Generals in Blue: Lives of the Union Commanders''. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1964. . * Wert, Jeffry D. ''The Sword of Lincoln: The Army of the Potomac''. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2005. . * Wilson, James Grant, John Fiske and Stanley L. Klos, eds

"Ambrose Burnside." In ''Appleton's Cyclopedia of American Biography''

New Work: D. Appleton & Co., 1887–1889 and 1999.

External links

at History of American Women

Ambrose E. Burnside in ''Encyclopedia Virginia''

Burnside's grave

()

{{DEFAULTSORT:Burnside, Ambrose 1824 births 1881 deaths 19th-century Rhode Island politicians 19th-century United States senators American militia generals American people of English descent American people of Irish descent Burials at Swan Point Cemetery Chairmen of the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations Grand Army of the Republic commanders-in-chief People from Liberty, Indiana People of Indiana in the American Civil War People of Rhode Island in the American Civil War Presidents of the National Rifle Association Republican Party United States senators from Rhode Island Republican Party governors of Rhode Island Union army generals United States Military Academy alumni