Gay Novel on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Gay literature is a collective term for

Many

Many

The era known as the

The era known as the

In the 21st century, much of LGBT literature has achieved a high level of sophistication and many works have earned mainstream acclaim. Notable authors include

In the 21st century, much of LGBT literature has achieved a high level of sophistication and many works have earned mainstream acclaim. Notable authors include

Document ID 5291

* * Reade, Brian (1970). '' Sexual Heretics: Male Homosexuality in English Literature from 1850 to 1900''.

Lambda Literary Foundation – Publishes the Lambda Book Report and the Lambda Literary Awards

Blithe House Quarterly – online journal

* ttp://www.nuwinepress.com NuWine Press - Gay Christian Book Publisher featuring fresh perspectives on the Christian faith

Lodestar Quarterly — an Online Journal of the Finest Gay, Lesbian, and Queer Literature

Lesbian Mysteries

features Lesbian Mystery Novels

Gay's the Word

UK LGBTQ Specialist Bookshop

* ttp://www.leewind.orgLists, summarizes, and offers reader reviews of Teen, Middle Grade, and Picture Books with Gay (GLBTQ) characters and themes. * {{Authority control

literature

Literature is any collection of Writing, written work, but it is also used more narrowly for writings specifically considered to be an art form, especially novels, Play (theatre), plays, and poetry, poems. It includes both print and Electroni ...

produced by or for the gay community

The LGBTQ community (also known as the LGBT, LGBT+, LGBTQ+, LGBTQIA, LGBTQIA+, or queer community) comprises LGBTQ individuals united by a common culture and social movements. These communities generally celebrate pride, diversity, individua ...

which involves character

Character or Characters may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Literature

* ''Character'' (novel), a 1936 Dutch novel by Ferdinand Bordewijk

* ''Characters'' (Theophrastus), a classical Greek set of character sketches attributed to Theoph ...

s, plot

Plot or Plotting may refer to:

Art, media and entertainment

* Plot (narrative), the connected story elements of a piece of fiction

Music

* ''The Plot'' (album), a 1976 album by jazz trumpeter Enrico Rava

* The Plot (band), a band formed in 2003

...

lines, and/or themes portraying male homosexual

Homosexuality is romantic attraction, sexual attraction, or sexual behavior between people of the same sex or gender. As a sexual orientation, homosexuality is "an enduring pattern of emotional, romantic, and/or sexual attractions" exc ...

behavior.

Overview and history

Because the social acceptance of homosexuality has varied in many world cultures throughout history, LGBT literature has covered a vast array of themes and concepts. LGBT individuals have often turned to literature as a source of validation, understanding, and beautification of same-sex attraction. In contexts where homosexuality has been perceived negatively, LGBT literature may also document the psychological stresses and alienation suffered by those experiencing prejudice, legal discrimination,AIDS

The HIV, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is a retrovirus that attacks the immune system. Without treatment, it can lead to a spectrum of conditions including acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). It is a Preventive healthcare, pr ...

, self-loathing, bullying, violence, religious condemnation, denial, suicide, persecution, and other such obstacles.

Themes of love between individuals of the same gender are found in a variety of ancient texts throughout the world. The ancient Greeks, in particular, explored the theme on a variety of different levels in such works as Plato's ''Symposium

In Ancient Greece, the symposium (, ''sympósion'', from συμπίνειν, ''sympínein'', 'to drink together') was the part of a banquet that took place after the meal, when drinking for pleasure was accompanied by music, dancing, recitals, o ...

''.

Ancient mythology

Many

Many mythologies

Myth is a genre of folklore consisting primarily of narratives that play a fundamental role in a society. For scholars, this is very different from the vernacular usage of the term "myth" that refers to a belief that is not true. Instead, the ...

and religious narratives include stories of romantic affection or sexuality between men or feature divine actions that result in changes in gender. These myths have been interpreted as forms of LGBT expression and modern conceptions of sexuality and gender have been applied to them. Myths have been used by individual cultures, in part, to explain and validate their particular social institutions or to explain the cause of transgender identity or homosexuality.

In classical mythology, male lovers were attributed to ancient Greek god

In ancient Greece, deities were regarded as immortal, anthropomorphic, and powerful. They were conceived of as individual persons, rather than abstract concepts or notions, and were described as being similar to humans in appearance, albeit larg ...

s and heroes such as Zeus

Zeus (, ) is the chief deity of the List of Greek deities, Greek pantheon. He is a sky father, sky and thunder god in ancient Greek religion and Greek mythology, mythology, who rules as king of the gods on Mount Olympus.

Zeus is the child ...

, Apollo

Apollo is one of the Twelve Olympians, Olympian deities in Ancient Greek religion, ancient Greek and Ancient Roman religion, Roman religion and Greek mythology, Greek and Roman mythology. Apollo has been recognized as a god of archery, mu ...

, Poseidon

Poseidon (; ) is one of the twelve Olympians in ancient Greek religion and mythology, presiding over the sea, storms, earthquakes and horses.Burkert 1985pp. 136–139 He was the protector of seafarers and the guardian of many Hellenic cit ...

and Heracles

Heracles ( ; ), born Alcaeus (, ''Alkaios'') or Alcides (, ''Alkeidēs''), was a Divinity, divine hero in Greek mythology, the son of ZeusApollodorus1.9.16/ref> and Alcmene, and the foster son of Amphitryon.By his adoptive descent through ...

(including Ganymede, Hyacinth

''Hyacinthus'' is a genus of bulbous herbs, and spring-blooming Perennial plant, perennials. They are fragrant flowering plants in the family Asparagaceae, subfamily Scilloideae and are commonly called hyacinths (). The genus is native predomin ...

, Nerites and Hylas

In classical mythology, Hylas () was a youth who served Heracles (Roman Hercules) as companion and servant. His abduction by water nymphs was a theme of ancient art, and has been an enduring subject for Western art in the classical tradition.

G ...

, respectively) as a reflection and validation of the tradition of pederasty

Pederasty or paederasty () is a sexual relationship between an adult man and an adolescent boy. It was a socially acknowledged practice in Ancient Greece and Rome and elsewhere in the world, such as Pre-Meiji Japan.

In most countries today, ...

.

Early works

ThoughHomer

Homer (; , ; possibly born ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Despite doubts about his autho ...

did not explicitly portray the heroes Achilles and Patroclus

The relationship between Achilles and Patroclus is a key element of the stories associated with the Trojan War. In the ''Iliad,'' Homer describes a deep, meaningful relationship between Achilles and Patroclus, where Achilles is tender toward Patr ...

as homosexual lovers in his 8th-century BC Trojan War

The Trojan War was a legendary conflict in Greek mythology that took place around the twelfth or thirteenth century BC. The war was waged by the Achaeans (Homer), Achaeans (Ancient Greece, Greeks) against the city of Troy after Paris (mytho ...

epic, the ''Iliad

The ''Iliad'' (; , ; ) is one of two major Ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by modern audiences. As with the ''Odyssey'', the poem is divided into 24 books and ...

'', later ancient authors presented the intense relationship as such. In his 5th-century BC lost tragedy ''The Myrmidons

Priam (right) entering the hut of Achilles in his effort to ransom the body of Hector. The figure at left is probably one of Achilles' servant boys. (Attic red-figure kylix of the early fifth century BCE)

The ''Achilleis'' (; Ancient Greek , ' ...

'', Aeschylus

Aeschylus (, ; ; /524 – /455 BC) was an ancient Greece, ancient Greek Greek tragedy, tragedian often described as the father of tragedy. Academic knowledge of the genre begins with his work, and understanding of earlier Greek tragedy is large ...

casts Achilles and Patroclus as pederastic lovers. In a surviving fragment of the play, Achilles speaks of "our frequent kisses" and a "devout union of the thighs". Plato

Plato ( ; Greek language, Greek: , ; born BC, died 348/347 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher of the Classical Greece, Classical period who is considered a foundational thinker in Western philosophy and an innovator of the writte ...

does the same in his ''Symposium

In Ancient Greece, the symposium (, ''sympósion'', from συμπίνειν, ''sympínein'', 'to drink together') was the part of a banquet that took place after the meal, when drinking for pleasure was accompanied by music, dancing, recitals, o ...

'' (385–370 BC); the speaker Phaedrus cites Aeschylus and holds Achilles up as an example of how people will be more brave and even sacrifice themselves for their lovers. In his oration ''Against Timarchus

"Against Timarchus" () was a speech by Aeschines accusing Timarchus of being unfit to involve himself in public life. The case was brought about in 346–345 BC, in response to Timarchus, along with Demosthenes, bringing a suit against Aeschines, a ...

'', Aeschines

Aeschines (; Greek: ; 389314 BC) was a Greek statesman and one of the ten Attic orators.

Biography

Although it is known he was born in Athens, the records regarding his parentage and early life are conflicting; but it seems probable that h ...

argues that though Homer "hides their love and avoids giving a name to their friendship", Homer assumed that educated readers would understand the "exceeding greatness of their affection". Plato's ''Symposium'' also includes a creation myth

A creation myth or cosmogonic myth is a type of cosmogony, a symbolic narrative of how the world began and how people first came to inhabit it., "Creation myths are symbolic stories describing how the universe and its inhabitants came to be. Cre ...

that explains homo- and heterosexuality (Aristophanes

Aristophanes (; ; ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek Ancient Greek comedy, comic playwright from Classical Athens, Athens. He wrote in total forty plays, of which eleven survive virtually complete today. The majority of his surviving play ...

speech) and celebrates the pederastic tradition and erotic love between men ( Pausanias speech), as does another of his dialogue

Dialogue (sometimes spelled dialog in American and British English spelling differences, American English) is a written or spoken conversational exchange between two or more people, and a literature, literary and theatrical form that depicts suc ...

s, '' Phaedrus''.

The tradition of pederasty in ancient Greece

Pederasty in ancient Greece was a socially acknowledged relationship between an older male (the ''erastes'') and a younger male (the '' eromenos'') usually in his teens. It was characteristic of the Archaic and Classical periods.

Some s ...

(as early as 650 BC) and later the acceptance of limited homosexuality in ancient Rome

Homosexuality in ancient Rome Societal attitudes toward homosexuality, differed markedly from the contemporary Western culture, West. Latin lacks words that would precisely Translation, translate "homosexual" and "heterosexual". The primary dich ...

infused an awareness of male-male attraction and sex into ancient poetry. In the second

The second (symbol: s) is a unit of time derived from the division of the day first into 24 hours, then to 60 minutes, and finally to 60 seconds each (24 × 60 × 60 = 86400). The current and formal definition in the International System of U ...

of Virgil

Publius Vergilius Maro (; 15 October 70 BC21 September 19 BC), usually called Virgil or Vergil ( ) in English, was an ancient Rome, ancient Roman poet of the Augustan literature (ancient Rome), Augustan period. He composed three of the most fa ...

's ''Eclogues

The ''Eclogues'' (; , ), also called the ''Bucolics'', is the first of the three major works of the Latin poet Virgil.

Background

Taking as his generic model the Greek bucolic poetry of Theocritus, Virgil created a Roman version partly by o ...

'' (1st century BC), the shepherd Corydon proclaims his love for the boy Alexis. Some of the erotic poetry of Catullus

Gaius Valerius Catullus (; ), known as Catullus (), was a Latin neoteric poet of the late Roman Republic. His surviving works remain widely read due to their popularity as teaching tools and because of their personal or sexual themes.

Life

...

in the same century is directed at other men (''Carmen 48'', ''50'', and ''99''), and in a wedding hymn (''Carmen 61'') he portrays a male concubine

Concubinage is an interpersonal relationship, interpersonal and Intimate relationship, sexual relationship between two people in which the couple does not want to, or cannot, enter into a full marriage. Concubinage and marriage are often regarde ...

about to be supplanted by his master's future wife. The first line of his infamous invective

Invective (from Middle English ''invectif'', or Old French and -4; we might wonder whether there's a point at which it's appropriate to talk of the beginnings of French, that is, when it wa ... and Late Latin ''invectus'') is abusive, or insulting ...

'' Carmen 16'' — which has been called "one of the filthiest expressions ever written in Latin—or in any other language, for that matter" — contains explicit homosexual sex acts.

The ''Satyricon

The ''Satyricon'', ''Satyricon'' ''liber'' (''The Book of Satyrlike Adventures''), or ''Satyrica'', is a Latin work of fiction believed to have been written by Gaius Petronius in the late 1st century AD, though the manuscript tradition identifi ...

'' by is a Latin work of fiction detailing the misadventures of Encolpius and his lover, a handsome and promiscuous sixteen-year-old servant boy named Giton. Written in the 1st century AD during the reign of Nero

Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus ( ; born Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus; 15 December AD 37 – 9 June AD 68) was a Roman emperor and the final emperor of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, reigning from AD 54 until his ...

, it is the earliest known text of its kind depicting homosexuality.

In the celebrated Japanese work ''The Tale of Genji

is a classic work of Japanese literature written by the noblewoman, poet, and lady-in-waiting Murasaki Shikibu around the peak of the Heian period, in the early 11th century. It is one of history's first novels, the first by a woman to have wo ...

'', written by Murasaki Shikibu

was a Japanese novelist, Japanese poetry#Age of Nyobo or court ladies, poet and lady-in-waiting at the Imperial Court in Kyoto, Imperial court in the Heian period. She was best known as the author of ''The Tale of Genji'', widely considered t ...

in the early 11th century, the title character Hikaru Genji

is the protagonist of Murasaki Shikibu's Heian-era Japanese novel ''The Tale of Genji''. "Hikaru" means "shining", deriving from his appearance, hence he is known as the "Shining Prince." He is portrayed as a superbly handsome man and a gen ...

is rejected by the lady Utsusemi in chapter 3 and instead sleeps with her young brother: "Genji pulled the boy down beside him ... Genji, for his part, or so one is informed, found the boy more attractive than his chilly sister."

Antonio Rocco

Antonio Rocco (1586–1653) was an Italian priest and philosophy teacher (he graduated under Cesare Cremonini), and a writer. Ever since 1888, when he was identified as its anonymous author, he is best known for his satirical homosexual text, ' ...

's '' Alcibiades the Schoolboy'', published anonymously in 1652, is an Italian dialogue

Dialogue (sometimes spelled dialog in American and British English spelling differences, American English) is a written or spoken conversational exchange between two or more people, and a literature, literary and theatrical form that depicts suc ...

written as a defense of homosexual sodomy

Sodomy (), also called buggery in British English, principally refers to either anal sex (but occasionally also oral sex) between people, or any Human sexual activity, sexual activity between a human and another animal (Zoophilia, bestiality). I ...

. The first such explicit work known to be written since ancient times, its intended purpose as a "Carnivalesque

The Carnivalesque is a literary mode that subverts and liberates the assumptions of the dominant style or atmosphere through humor and chaos. It originated as "carnival" in Mikhail Bakhtin's ''Problems of Dostoevsky's Poetics'' and was further dev ...

satire

Satire is a genre of the visual, literary, and performing arts, usually in the form of fiction and less frequently non-fiction, in which vices, follies, abuses, and shortcomings are held up to ridicule, often with the intent of exposin ...

", a defense of pederasty

Pederasty or paederasty () is a sexual relationship between an adult man and an adolescent boy. It was a socially acknowledged practice in Ancient Greece and Rome and elsewhere in the world, such as Pre-Meiji Japan.

In most countries today, ...

, or a work of pornography

Pornography (colloquially called porn or porno) is Sexual suggestiveness, sexually suggestive material, such as a picture, video, text, or audio, intended for sexual arousal. Made for consumption by adults, pornographic depictions have evolv ...

is unknown, and debated.

Several medieval

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of World history (field), global history. It began with the fall of the West ...

European works contain references to homosexuality, such as in ''Giovanni Boccaccio

Giovanni Boccaccio ( , ; ; 16 June 1313 – 21 December 1375) was an Italian people, Italian writer, poet, correspondent of Petrarch, and an important Renaissance humanism, Renaissance humanist. Born in the town of Certaldo, he became so ...

''s ''Decameron

''The Decameron'' (; or ''Decamerone'' ), subtitled ''Prince Galehaut'' (Old ) and sometimes nicknamed ''l'Umana commedia'' ("the Human comedy", as it was Boccaccio that dubbed Dante Alighieri's ''Comedy'' "''Divine''"), is a collection of ...

'' or ''Lanval

''Lanval'' is one of the Lais of Marie de France. Written in Anglo-Norman, it tells the story of Lanval, a knight at King Arthur's court, who is overlooked by the king, wooed by a fairy lady, given all manner of gifts by her, and subsequently r ...

'', a French lai, in which the knight Lanval is accused by Guinevere

Guinevere ( ; ; , ), also often written in Modern English as Guenevere or Guenever, was, according to Arthurian legend, an early-medieval queen of Great Britain and the wife of King Arthur. First mentioned in literature in the early 12th cen ...

of having "no desire for women". Others include homosexual themes, like '' Yde et Olive''.

18th and 19th centuries

The era known as the

The era known as the Age of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment (also the Age of Reason and the Enlightenment) was a Europe, European Intellect, intellectual and Philosophy, philosophical movement active from the late 17th to early 19th century. Chiefly valuing knowledge gained th ...

(the 1650s to the 1780s) gave rise to, in part, a general challenge to the traditional doctrines of society in Western Europe. A particular interest in the Classical era of Greece and Rome "as a model for contemporary life" put the Greek appreciation of nudity, the male form and male friendship (and the inevitable homoerotic overtones) into art and literature. It was common for gay authors at this time to include allusions to Greek mythological characters as a code that homosexual readers would recognize. Gay men of the period "commonly understood ancient Greece and Rome to be societies where homosexual relationships were tolerated and even encouraged", and references to those cultures might identify an author or book's sympathy with gay readers and gay themes but probably be overlooked by straight readers. Despite the "increased visibility of queer behavior" and prospering networks of male prostitution

Male prostitution is a form of sex work consisting of the act or practice of men providing sexual services in return for payment. Although clients can be of any gender, the vast majority are older males looking to fulfill their sexual needs. M ...

in cities like Paris and London, homosexual activity had been outlawed in England (and by extension, the United States) as early as the Buggery Act 1533

The Buggery Act 1533, formally An Acte for the punishment of the vice of Buggerie (25 Hen. 8. c. 6), was an Act of Parliament (United Kingdom), act of the Parliament of England that was passed during the reign of Henry VIII.

The act was the c ...

. Across much of Europe in the 1700s and 1800s, the legal punishment for sodomy was death, making it dangerous to publish or distribute anything with overt gay themes. James Jenkins of Valancourt Books

Valancourt Books is an independent American publishing house founded by James Jenkins and Ryan Cagle in 2005. The company specializes in "the rediscovery of rare, neglected, and out-of-print fiction", in particular gay titles, Gothic novels a ...

noted:

Many early Gothic fiction

Gothic fiction, sometimes referred to as Gothic horror (primarily in the 20th century), is a literary aesthetic of fear and haunting. The name of the genre is derived from the Renaissance era use of the word "gothic", as a pejorative to mean me ...

authors, like Matthew Lewis, William Thomas Beckford

William Thomas Beckford (29 September 1760 – 2 May 1844) was an English novelist, art critic, planter and politician. He was reputed at one stage to be England's richest commoner.

He was the son of William Beckford (politician), William Beckf ...

and Francis Lathom

Francis Lathom (14 July 1774 – 19 May 1832) was a British gothic novelist and playwright. Most of his novels were out of print throughout the 20th century, but some have since been rediscovered and republished by Valancourt Books. His best kn ...

, were homosexual, and would sublimate these themes and express them in more acceptable forms, using transgressive genres like Gothic and horror fiction. The title character of Lewis's ''The Monk

''The Monk: A Romance'' is a Gothic novel by Matthew Gregory Lewis, published in 1796 across three volumes. Written early in Lewis's career, it was published anonymously when he was 20. It tells the story of a virtuous Catholic monk who give ...

'' (1796) falls in love with young novice Rosario, and though Rosario is later revealed to be a woman named Matilda, the gay subtext is clear. A similar situation occurs in Charles Maturin

Charles Robert Maturin, also known as C. R. Maturin (25 September 1780 – 30 October 1824), was an Irish Protestant clergyman (ordained in the Church of Ireland) and a writer of Gothic fiction, Gothic plays and novels.Chris Morgan, "Maturin, C ...

's ''The Fatal Revenge'' (1807) when the valet Cyprian asks his master, Ippolito, to kiss him as though he were Ippolito's lover; later Cyprian is also revealed to be a woman. In Maturin's ''Melmoth the Wanderer

''Melmoth the Wanderer'' is an 1820 Gothic novel by Irish playwright, novelist and clergyman Charles Maturin. The novel's titular character is a scholar who sold his soul to the devil in exchange for 150 extra years of life, and searches the wo ...

'' (1820), the close friendship between a young monk and a new novice is scrutinized as potentially "too like love". Sheridan Le Fanu

Joseph Thomas Sheridan Le Fanu (; 28 August 1814 – 7 February 1873), popularly known as J. S. Le Fanu, was an Irish writer of Gothic literature, mystery novels, and horror fiction. Considered by critics to be one of the greatest ghost ...

's novella ''Carmilla

''Carmilla'' is an 1872 Gothic fiction, Gothic novella by Irish author Sheridan Le Fanu, Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu. It is one of the earliest known works of vampire fiction, predating Bram Stoker's ''Dracula'' (1897) by 25 years. First published ...

'' (1872) was the first lesbian vampire

Lesbian vampirism is a Trope (literature), trope in early gothic horror and 20th century exploitation film. The archetype of a lesbian vampire used the fantasy genre to circumvent the heavy LGBT censorship, censorship of lesbian characters in the ...

story, and influenced Bram Stoker

Abraham Stoker (8 November 1847 – 20 April 1912), better known by his pen name Bram Stoker, was an Irish novelist who wrote the 1897 Gothic horror novel ''Dracula''. The book is widely considered a milestone in Vampire fiction, and one of t ...

's ''Dracula

''Dracula'' is an 1897 Gothic fiction, Gothic horror fiction, horror novel by Irish author Bram Stoker. The narrative is Epistolary novel, related through letters, diary entries, and newspaper articles. It has no single protagonist and opens ...

'' (1897). Stoker's novel has its own homoerotic aspects, as when Count Dracula

Count Dracula () is the title character of Bram Stoker's 1897 gothic horror novel ''Dracula''. He is considered the prototypical and archetypal vampire in subsequent works of fiction. Aspects of the character are believed by some to have been i ...

warns off the female vampire

A vampire is a mythical creature that subsists by feeding on the Vitalism, vital essence (generally in the form of blood) of the living. In European folklore, vampires are undead, undead humanoid creatures that often visited loved ones and c ...

s and claims Jonathan Harker

Jonathan Harker is a fictional character and one of the main protagonists of Bram Stoker's 1897 Gothic horror novel ''Dracula''. An English solicitor, his journey to Transylvania and encounter with the vampire Count Dracula and his Brides at Ca ...

, saying "This man belongs to me!"

'' A Year in Arcadia: Kyllenion'' (1805) by Augustus, Duke of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg

Augustus, Duke of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg (full name: ''Emil Leopold August'') (23 November 1772 — 17 May 1822), was a Duke of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg, and the author of one of the first modern novels to treat of homoerotic love. He was the maternal ...

is "the earliest known novel that centers on an explicitly male-male love affair". Set in ancient Greece, the German novel features several couples—including a homosexual one—falling in love, overcoming obstacles and living happily ever after. The Romantic movement

Romanticism (also known as the Romantic movement or Romantic era) was an artistic and intellectual movement that originated in Europe towards the end of the 18th century. The purpose of the movement was to advocate for the importance of subjec ...

gaining momentum at the end of the 18th century allowed men to "express deep affection for each other", and the motif of ancient Greece as "a utopia of male-male love" was an acceptable vehicle to reflect this, but some of Duke August's contemporaries felt that his characters "stepped over the bounds of manly affection into unseemly eroticism." The first American gay novel was '' Joseph and His Friend: A Story of Pennsylvania'' (1870) by Bayard Taylor

Bayard Taylor (January 11, 1825December 19, 1878) was an American poet, literary critic, translator, travel author, and diplomat. As a poet, he was very popular, with a crowd of more than 4,000 attending a poetry reading once, which was a record ...

, the story of a newly engaged young man who finds himself instead falling in love with another man. Robert K. Martin called it "quite explicit in its adoption of a political stance toward homosexuality" and notes that the character Philip "argues for the 'rights' of those 'who cannot shape themselves according to the common-place pattern of society. Henry Blake Fuller's 1898 play, ''At St. Judas's'', and 1919 novel, '' Bertram Cope's Year'', are noted as among the earliest published American works in literature on the theme of homosexual relationships.

The new "atmosphere of frankness" created by the Enlightenment sparked the production of pornography like John Cleland

John Cleland (24 September 1709 – 23 January 1789) was an English novelist best known for his fictional '' Fanny Hill: or, the Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure'', whose eroticism led to his arrest. James Boswell called him "a sly, old malcont ...

's infamous ''Fanny Hill

''Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure'' – popularly known as ''Fanny Hill'' – is an erotic novel by the English novelist John Cleland first published in London in 1748 and 1749. Written while the author was in debtors' prison in London,Wagne ...

'' (1749), which features a rare graphic scene of male homosexual sex. Published anonymously a century later, ''The Sins of the Cities of the Plain

''The Sins of the Cities of the Plain; or, The Recollections of a Mary-Ann, with Short Essays on Sodomy and Tribadism'', by the pseudonymous " Jack Saul", is one of the first exclusively homosexual works of pornographic literature published in E ...

'' (1881) and ''Teleny, or The Reverse of the Medal

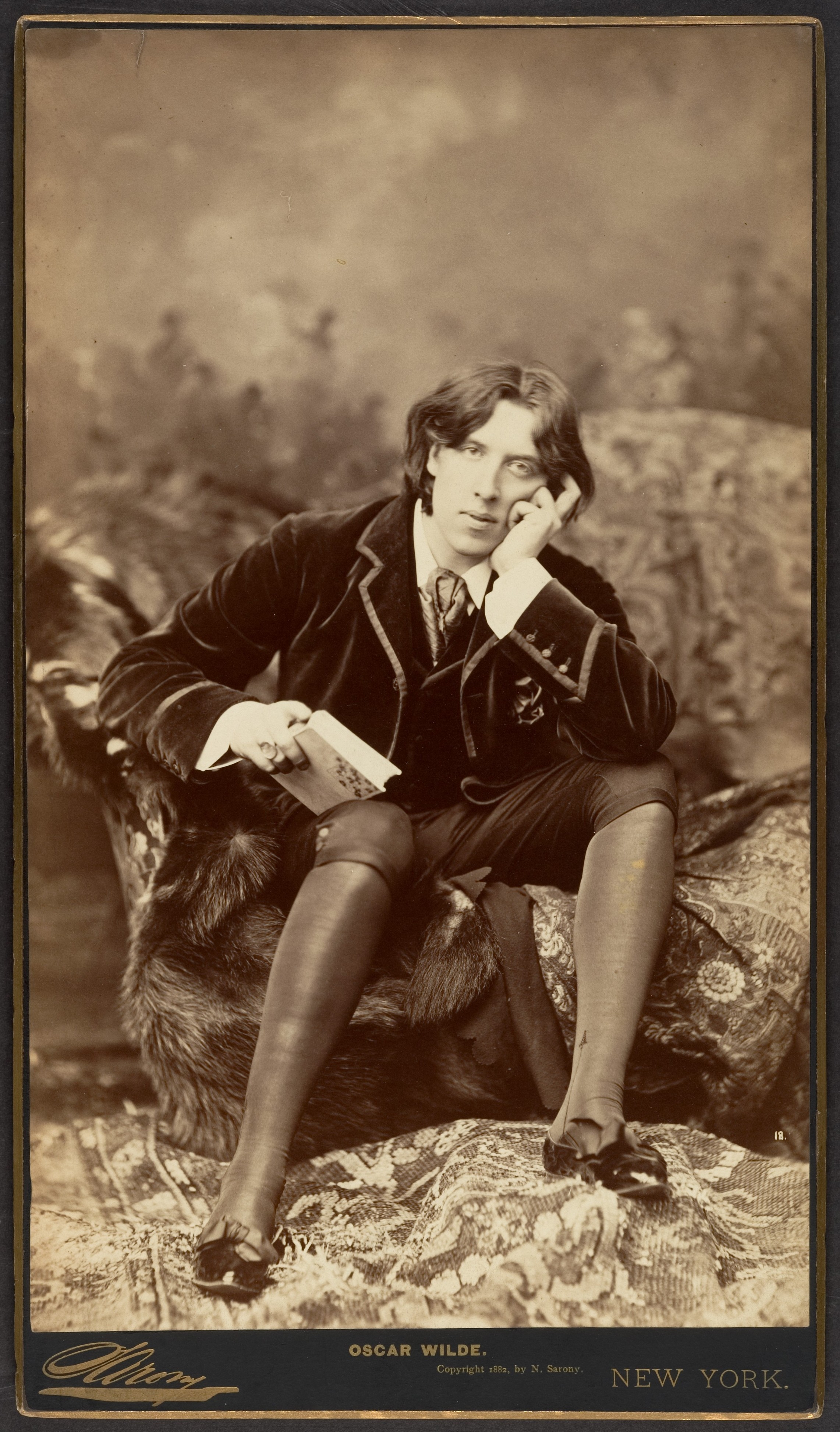

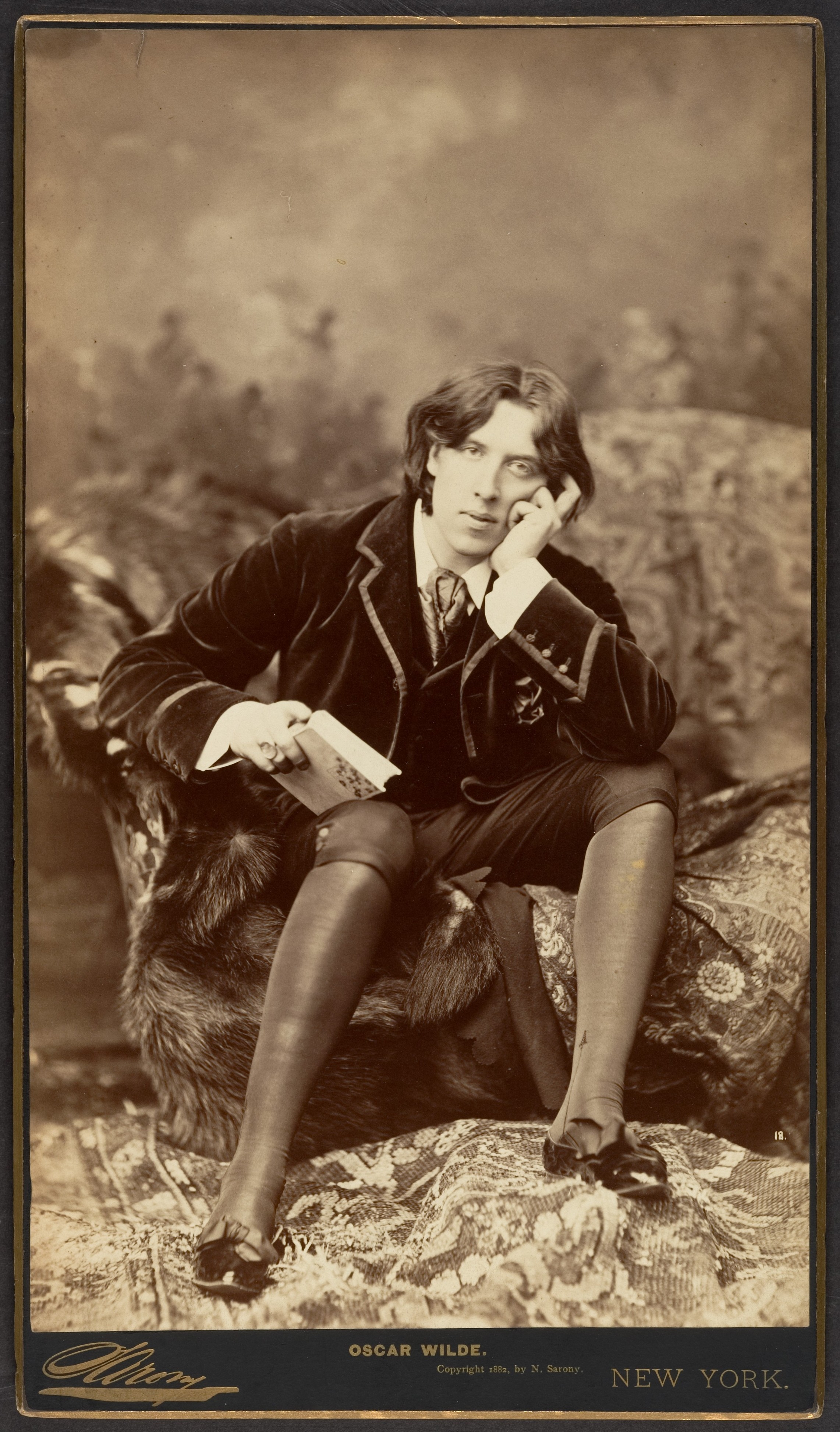

''Teleny, or The Reverse of the Medal'' is a pornographic novel, first published in London in 1893. The authorship of the work is unknown. There is a consensus that it was an ensemble effort, but it has often been attributed to Oscar Wilde. Se ...

'' (1893) are two of the earliest pieces of English-language pornography to explicitly and near-exclusively concern homosexuality. ''The Sins of the Cities of the Plain'' is about a male prostitute, and set in London around the time of the Cleveland Street Scandal

The Cleveland Street scandal occurred in 1889, when a homosexual male brothel and Love hotel, house of assignation on Cleveland Street, London, was discovered by police. The government was accused of covering up the scandal to protect the names ...

and the Oscar Wilde

Oscar Fingal O'Fflahertie Wills Wilde (16 October 185430 November 1900) was an Irish author, poet, and playwright. After writing in different literary styles throughout the 1880s, he became one of the most popular and influential playwright ...

trials. ''Teleny'', chronicling a passionate affair between a Frenchman and a Hungarian pianist, is often attributed to a collaborative effort by Wilde and some of his contemporaries. Wilde's more mainstream ''The Picture of Dorian Gray

''The Picture of Dorian Gray'' is an 1890 philosophical fiction and Gothic fiction, Gothic horror fiction, horror novel by Irish writer Oscar Wilde. A shorter novella-length version was published in the July 1890 issue of the American period ...

'' (1890) still shocked readers with its sensuality and overtly homosexual characters. Drew Banks called Dorian Gray a groundbreaking gay character because he was "one of the first in a long list of hedonistic

Hedonism is a family of philosophical views that prioritize pleasure. Psychological hedonism is the theory that all human behavior is motivated by the desire to maximize pleasure and minimize pain. As a form of egoism, it suggests that peopl ...

fellows whose homosexual tendencies secured a terrible fate." The French realist Émile Zola

Émile Édouard Charles Antoine Zola (, ; ; 2 April 184029 September 1902) was a French novelist, journalist, playwright, the best-known practitioner of the literary school of Naturalism (literature), naturalism, and an important contributor to ...

in his novel ''Nana

Nana, Na Na or NANA may refer to:

People

* Nana (given name), including a list of people and characters with the given name

* Nana (surname), including a list of people and characters with the surname

* Nana (chief) (died 1896), Mimbreño Ap ...

'' (1880) depicted, along with a wide variety of heterosexual couplings and some lesbian scenes, a single homosexual character, Labordette. Paris theater society and the ''demi-monde'' are long accustomed to his presence and role as go-between; he knows all the women, escorts them, and runs errands for them. He is "a parasite, with even a touch of pimp", but also a more sympathetic figure than most of the men, as much a moral coward as them but physically brave and not a stereotype.

20th century

By the 20th century, discussion of homosexuality became more open and society's understanding of it evolved. A number of novels with explicitly gay themes and characters began to appear in the domain of mainstream or art literature.Nobel Prize

The Nobel Prizes ( ; ; ) are awards administered by the Nobel Foundation and granted in accordance with the principle of "for the greatest benefit to humankind". The prizes were first awarded in 1901, marking the fifth anniversary of Alfred N ...

-winner André Gide

André Paul Guillaume Gide (; 22 November 1869 – 19 February 1951) was a French writer and author whose writings spanned a wide variety of styles and topics. He was awarded the 1947 Nobel Prize in Literature. Gide's career ranged from his begi ...

's semi-autobiographical novel ''The Immoralist

''The Immoralist'' () is a novel by André Gide, published in France in 1902.

Plot

''The Immoralist'' is a recollection of events that Michel narrates to his three visiting friends. One of those friends solicits job search assistance for Miche ...

'' (1902) finds a newly married man reawakened by his attraction to a series of young Arab boys. Though Bayard Taylor's ''Joseph and His Friend'' (1870) had been the first American gay novel, Edward Prime-Stevenson's '' Imre: A Memorandum'' (1906) was the first in which the homosexual couple were happy and united at the end. Initially published privately under the pseudonym "Xavier Mayne", it tells the story of a British aristocrat and a Hungarian soldier whose new friendship turns into love. In Thomas Mann

Paul Thomas Mann ( , ; ; 6 June 1875 – 12 August 1955) was a German novelist, short story writer, social critic, philanthropist, essayist, and the 1929 Nobel Prize in Literature laureate. His highly symbolic and ironic epic novels and novell ...

's 1912 novella ''Death in Venice

''Death in Venice ''() is a novella by German author Thomas Mann, published in 1912. It presents an ennobled writer who visits Venice and is liberated, uplifted, and then increasingly obsessed by the sight of a boy in a family of Polish tourist ...

'', a tightly wound, aging writer finds himself increasingly infatuated with a young Polish boy. Marcel Proust

Valentin Louis Georges Eugène Marcel Proust ( ; ; 10 July 1871 – 18 November 1922) was a French novelist, literary critic, and essayist who wrote the novel (in French – translated in English as ''Remembrance of Things Past'' and more r ...

's serialized novel ''In Search of Lost Time

''In Search of Lost Time'' (), first translated into English as ''Remembrance of Things Past'', and sometimes referred to in French as ''La Recherche'' (''The Search''), is a novel in seven volumes by French author Marcel Proust. This early twen ...

'' (1913–1927) and Gide's '' The Counterfeiters'' (1925) also explore homosexual themes.

British author E.M. Forster

Edward Morgan Forster (1 January 1879 – 7 June 1970) was an English author. He is best known for his novels, particularly '' A Room with a View'' (1908), ''Howards End'' (1910) and '' A Passage to India'' (1924). He also wrote numerous shor ...

earned a prominent reputation as a novelist while concealing his own homosexuality from the broader British public. In 1913–14, he privately penned ''Maurice

Maurice may refer to:

*Maurice (name), a given name and surname, including a list of people with the name

Places

* or Mauritius, an island country in the Indian Ocean

*Maurice, Iowa, a city

*Maurice, Louisiana, a village

*Maurice River, a trib ...

'', a bildungsroman that follows a young, upper-middle-class man through the self-discovery of his own attraction to other men, two relationships, and his interactions with an often uncomprehending or hostile society. The book is notable for its affirming tone and happy ending. "A happy ending was imperative", wrote Forster, "I was determined that in fiction anyway, two men should fall in love and remain in it for the ever and ever that fiction allows ... Happiness is its keynote." The book was not published until 1971, after Forster's death. William J. Mann

William J. Mann (born August 7, 1963) is an American novelist, biographer, and Hollywood historian best known for his studies of Hollywood and the American film industry, especially his 2006 biography of Katharine Hepburn, ''Kate: The Woman Who W ...

said of the novel, " lec Scudder of ''Maurice'' wasa refreshingly unapologetic young gay man who was not an effete Oscar Wilde aristocrat, but rather a working class, masculine, ordinary guy ... an example of the working class teaching the privileged class about honesty and authenticity a bit of a stereotype now, but back then quite extraordinary."

In Germany in 1920, Erwin von Busse

Erwin von Busse also known as Granand or Erwin von Busse-Granand (12 January 1885 – 10 April 1939) was a German writer, painter, theater director, art historian and art critic. His 1920 short story collection ''Das erotische Komödiengärtlein' ...

published a collection of short stories about erotic encounters between men using the pseudonym Granand. Promptly banned for "indecency", it was not republished until 1993 and only appeared in an English translation as ''Berlin Garden of Erotic Delights'' in 2022.

Blair Niles

Blair Niles (née Mary Blair Rice, 1880–1959) was an American novelist and travel writer. She was a founding member of the Society of Woman Geographers.

Early life and expeditions

Born Mary Blair Rice, Blair was born on ''The Oaks,'' her pa ...

's '' Strange Brother'' (1931), about the platonic relationship between a heterosexual woman and a gay man in New York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

in the late 1920s and early 1930s, is an early, objective exploration of homosexual issues during the Harlem Renaissance

The Harlem Renaissance was an intellectual and cultural revival of African-American music, dance, art, fashion, literature, theater, politics, and scholarship centered in Harlem, Manhattan, New York City, spanning the 1920s and 1930s. At the ti ...

. Though praised for its journalistic approach, sympathetic nature and promotion of tolerance and compassion, the novel has been numbered among a group of early gay novels that is "cast in the form of a tragic melodrama" and, according to editor and author Anthony Slide

Anthony Slide (born 7 November 1944) is an English writer who has produced more than seventy books and edited a further 150 on the history of popular entertainment. He wrote a "letter from Hollywood" for the British ''Film Review'' magazine fro ...

, illustrates the "basic assumption that gay characters in literature must come to a tragic end." "Smoke, Lilies, and Jade" by gay author and artist Richard Bruce Nugent

Richard Bruce Nugent (July 2, 1906 – May 27, 1987), aka Richard Bruce and Bruce Nugent, was an American gay writer and painter in the Harlem Renaissance. Nugent was among the few Harlem artists of the time who were publicly out. He was rec ...

, published in 1926, was the first short story by an African-American writer openly addressing his homosexuality. Written in a modernist stream-of-consciousness style, its subject matter was bisexuality and interracial male desire.

Forman Brown

Forman Brown (January 8, 1901 – January 10, 1996) was one of the world's leaders in puppet theatre in his day, as well as an important early gay novelist. He was a member of the Yale Puppeteers and the driving force behind Turnabout Theatre. ...

's 1933 novel ''Better Angel

''Better Angel'' is a novel by Forman Brown first published in 1933 under the pseudonym Richard Meeker. It was republished as ''Torment'' in 1951. It is an early novel which describes a gay lifestyle without condemning it. Christopher Carey calle ...

'', published under the pseudonym Richard Meeker, is an early novel which describes a gay lifestyle without condemning it. Christopher Carey called it "the first homosexual novel with a truly happy ending". Slide names only four familiar gay novels of the first half of the 20th century in English: Djuna Barnes

Djuna Barnes ( ; June 12, 1892 – June 18, 1982) was an American artist, illustrator, journalist, and writer who is perhaps best known for her novel '' Nightwood'' (1936), a cult classic of lesbian fiction and an important work of modernist lite ...

' ''Nightwood

''Nightwood'' is a 1936 novel by American author Djuna Barnes that was first published by publishing house Faber and Faber. It is one of the early prominent novels to portray explicit homosexuality between women, and as such can be considered ...

'' (1936), Carson McCullers

Carson McCullers (February 19, 1917 – September 29, 1967) was an American novelist, short-story writer, playwright, essayist, and poet. Her first novel, ''The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter'' (1940), explores the spiritual isolation of misfits ...

' '' Reflections in a Golden Eye'' (1941), Truman Capote

Truman Garcia Capote ( ; born Truman Streckfus Persons; September 30, 1924 – August 25, 1984) was an American novelist, screenwriter, playwright, and actor. Several of his short stories, novels, and plays have been praised as literary classics ...

's '' Other Voices, Other Rooms'' (1948) and Gore Vidal

Eugene Luther Gore Vidal ( ; born Eugene Louis Vidal, October 3, 1925 – July 31, 2012) was an American writer and public intellectual known for his acerbic epigrammatic wit. His novels and essays interrogated the Social norm, social and sexual ...

's ''The City and the Pillar

''The City and the Pillar'' is the third published novel by United States, American writer Gore Vidal, written in 1946 and published on January 10, 1948. The story is about a young man who is coming of age and discovers his own homosexuality.

...

'' (1948). In John O'Hara

John Henry O'Hara (January 31, 1905 – April 11, 1970) was an American writer. He was one of America's most prolific writers of Short story, short stories, credited with helping to invent ''The New Yorker'' magazine short story style.John O'H ...

's 1935 novel ''BUtterfield 8

''BUtterfield 8'' is a 1960 American drama film directed by Daniel Mann, starring Elizabeth Taylor and Laurence Harvey. Taylor won her first Academy Award for her performance in a leading role. The film was based on a 1935 novel of the same ...

'', the principal female character Gloria Wondrous has a friend Ann Paul, who in school "was suspect because of a couple of crushes which ... her former schoolmates were too free about calling Lesbian, and Gloria did not think so". Gloria speculates that "there was a little of that in practically all women", considers her own experience with women making passes, and rejects her own theory.

The story of a young man who is coming of age

Coming of age is a young person's transition from being a child to being an adult. The specific age at which this transition takes place varies between societies, as does the nature of the change. It can be a simple legal convention or can b ...

and discovers his own homosexuality, ''The City and the Pillar'' (1946) is recognized as the first post-World War II

The aftermath of World War II saw the rise of two global superpowers, the United States (U.S.) and the Soviet Union (U.S.S.R.). The aftermath of World War II was also defined by the rising threat of nuclear warfare, the creation and implementati ...

novel whose openly gay and well-adjusted protagonist is not killed off at the end of the story for defying social norms

A social norm is a shared standard of acceptance, acceptable behavior by a group. Social norms can both be informal understandings that govern the behavior of members of a society, as well as be codified into wikt:rule, rules and laws. Social norma ...

. It is also one of the "definitive war-influenced gay novels", one of the few books of its period dealing directly with male homosexuality. ''The City and the Pillar'' has also been called "the most notorious of the gay novels of the 1940s and 1950s." It sparked a public scandal, including notoriety and criticism, because it was released at a time when homosexuality was commonly considered immoral and because it was the first book by an accepted American author to portray overt homosexuality as a natural behavior. Upon its release, ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

'' refused to publish advertisements for the novel and Vidal was blacklist

Blacklisting is the action of a group or authority compiling a blacklist of people, countries or other entities to be avoided or distrusted as being deemed unacceptable to those making the list; if people are on a blacklist, then they are considere ...

ed to the extent that no major newspaper or magazine would review any of his novels for six years. Modern scholars note the importance of the novel to the visibility of gay literature. Michael Bronski

Michael Bronski (born May 12, 1949) is an American academic and writer, best known for his 2011 book ''A Queer History of the United States''. He has been involved with LGBT politics since 1969 as an activist and organizer. He has won numerous a ...

points out that "gay-male-themed books received greater critical attention than lesbian ones" and that "writers such as Gore Vidal were accepted as important American writers, even when they received attacks from homophobic critics." Ian Young notes that social disruptions of World War II changed public morals, and lists ''The City and the Pillar'' among a spate of war novels that use the military as backdrop for overt homosexual behavior.

Other notable works of the 1940s and 1950s include Jean Genet

Jean Genet (; ; – ) was a French novelist, playwright, poet, essayist, and political activist. In his early life he was a vagabond and petty criminal, but he later became a writer and playwright. His major works include the novels '' The Th ...

's semiautobiographical ''Our Lady of the Flowers

Our or OUR may refer to:

* The possessive form of " we"

Places

* Our (river), in Belgium, Luxembourg, and Germany

* Our, Belgium, a village in Belgium

* Our, Jura, a commune in France

Other uses

* Office of Utilities Regulation (OUR), a gove ...

'' (1943) and ''The Thief's Journal

''The Thief's Journal'' (''Journal du voleur'', published in 1949) is a novel by Jean Genet. Although autobiographical to some degree, Genet’s exploitation of poetic language results in an ambiguity throughout the text. Superficially, the nove ...

'' (1949), Yukio Mishima

Kimitake Hiraoka ( , ''Hiraoka Kimitake''; 14 January 192525 November 1970), known by his pen name Yukio Mishima ( , ''Mishima Yukio''), was a Japanese author, poet, playwright, actor, model, Shintoist, Ultranationalism (Japan), ultranationalis ...

's ''Confessions of a Mask

is the second novel by Japanese author Yukio Mishima. First published on 5 July 1949 by Kawade Shobō, it launched him to national fame though he was only in his early twenties. Some have posited that Mishima's similarities to the main charac ...

'' (1949), Umberto Saba

Umberto Saba (9 March 1883 – 25 August 1957) was an Italian poet and novelist, born Umberto Poli in the cosmopolitan Mediterranean port of Trieste when it was the fourth largest city of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Poli assumed the pen name "S ...

's ''Ernesto Ernesto, form of the name Ernest in several Romance languages, may refer to:

* ''Ernesto'' (novel) (1953), an unfinished autobiographical novel by Umberto Saba, published posthumously in 1975

** ''Ernesto'' (film), a 1979 Italian drama loosely ba ...

'' (written in 1953, published posthumously in 1975), and ''Giovanni's Room

''Giovanni's Room'' is a 1956 novel by James Baldwin. The book concerns the events in the life of an American man living in Paris and his feelings and frustrations with his relationships with other men in his life, particularly an Italian barte ...

'' (1956) by James Baldwin

James Arthur Baldwin (né Jones; August 2, 1924 – December 1, 1987) was an American writer and civil rights activist who garnered acclaim for his essays, novels, plays, and poems. His 1953 novel '' Go Tell It on the Mountain'' has been ranked ...

. Mary Renault

Eileen Mary Challans (4 September 1905 – 13 December 1983), known by her pen name Mary Renault ("She always pronounced it 'Ren-olt', though almost everyone would come to speak of her as if she were a French car." ), was a British writer best k ...

's ''The Charioteer

''The Charioteer'' is a romantic war novel by Mary Renault (pseudonym for Eileen Mary Challans) first published in London in 1953. Renault's US publisher (Morrow) refused to publish it until 1959, after a revision of the text, due to its genera ...

'', a 1953 British war novel

A war novel or military fiction is a novel about war. It is a novel in which the primary action takes place on a battlefield, or in a civilian setting (or home front), where the characters are preoccupied with the preparations for, suffering th ...

about homosexual men in and out of the military, quickly became a bestseller

A bestseller is a book or other media noted for its top selling status, with bestseller lists published by newspapers, magazines, and book store chains. Some lists are broken down into classifications and specialties (novel, nonfiction book, cookb ...

within the gay community. Renault's historical novels ''The Last of the Wine

''The Last of the Wine'' is Mary Renault's first novel set in ancient Greece, the setting that would become her most important arena. The novel was published in 1956 and is the second of her works to feature male homosexuality as a major theme ...

'' (1956) about Athenian pederasty

Pederasty in ancient Greece was a socially acknowledged relationship between an older male (the ''erastes'') and a younger male (the ''eromenos'') usually in his teens. It was characteristic of the Archaic and Classical periods.

Some sc ...

in ancient Greece

Ancient Greece () was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity (), that comprised a loose collection of culturally and linguistically r ...

and '' The Persian Boy'' (1972) about Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon (; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), most commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia (ancient kingdom), Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip ...

and his slave lover Bagoas

Bagoas (; , ; died 336 BCE) was a prominent Persian official who served as the vizier (Chief Minister) of the Achaemenid Empire until his death.

Biography

Bagoas was a eunuch who later became vizier to Artaxerxes III. In this role, he allied ...

followed suit. '' A Room in Chelsea Square'' (1958) by British author Michael Nelson — about a wealthy gentleman who lures an attractive younger man to London with the promise of an upper crust lifestyle — was originally published anonymously both because of its explicit gay content at a time when homosexuality was still illegal, and because its characters were "thinly veiled portrayals of prominent London literary figures".

A key element of Allen Drury

Allen Stuart Drury (September 2, 1918 – September 2, 1998) was an American novelist. During World War II, he was a reporter in the Senate, closely observing Presidents Franklin D. Roosevelt and Harry S. Truman, among others. He would convert the ...

's 1959 bestselling and Pulitzer Prize

The Pulitzer Prizes () are 23 annual awards given by Columbia University in New York City for achievements in the United States in "journalism, arts and letters". They were established in 1917 by the will of Joseph Pulitzer, who had made his fo ...

-winning political novel

Political fiction employs narrative to comment on political events, systems and theories. Works of political fiction, such as political novels, often "directly criticize an existing society or present an alternative, even fant ...

''Advise and Consent

''Advise and Consent'' is a 1959 political fiction novel by Allen Drury that explores the United States Senate confirmation of controversial Secretary of State nominee Robert Leffingwell, whose promotion is endangered due to growing evidence ...

'' is the blackmail

Blackmail is a criminal act of coercion using a threat.

As a criminal offense, blackmail is defined in various ways in common law jurisdictions. In the United States, blackmail is generally defined as a crime of information, involving a thr ...

ing of young US senator Brigham Anderson, who is hiding a secret wartime homosexual tryst. In 2009, ''The Wall Street Journal

''The Wall Street Journal'' (''WSJ''), also referred to simply as the ''Journal,'' is an American newspaper based in New York City. The newspaper provides extensive coverage of news, especially business and finance. It operates on a subscriptio ...

'' Scott Simon

Scott Simon (born March 16, 1952) is an American journalist and the host of '' Weekend Edition Saturday'' on NPR.

Early life

Simon was born in Chicago, Illinois, the son of comedian Ernie Simon and actress Patricia Lyons.

wrote of Drury that "the conservative Washington novelist was more progressive than Hollywood liberals", noting that the character Anderson is "candid and unapologetic" about his affair, and even calling him "Drury's most appealing character". Frank Rich

Frank Hart Rich Jr. (born June 2, 1949) is an American essayist and liberal op-ed columnist, who held various positions within ''The New York Times'' from 1980 to 2011. He has also produced television series and documentaries for HBO.

Rich is ...

wrote in ''The New York Times'' in 2005:

In Taiwan, during the martial law period (1949–1987), the Kuomintang

The Kuomintang (KMT) is a major political party in the Republic of China (Taiwan). It was the one party state, sole ruling party of the country Republic of China (1912-1949), during its rule from 1927 to 1949 in Mainland China until Retreat ...

government focused on strengthening Taiwan's industrial and economic power and reinforcing traditional Confucious values on society. The heterosexual image of the modern family dominated, and "public discourses of same-sex desire were almost non-existent." Nevertheless, Pai Hsien-yung

Kenneth Hsien-yung Pai ( zh, c=白先勇, poj=Pe̍h Sian-ióng, p=Bái Xiānyǒng, w=Pai Hsien-yung; born July 11, 1937) is a Taiwanese writer who has been described as a "melancholy pioneer". He was born in Guilin, Guangxi at the cusp of the Se ...

's ''Jade Love'' (1960), "Moon Dream" (1960), "Youthfulness" (1961), and "Seventeen Years Old and Lonely" (1961) — novellas and short stories exploring male homosexual desire — were published in '' Xiandai Wenxue''. He published " A Sky Full of Bright, Twinkling Stars" in 1969, which follows gay characters who frequent Taipei's New Park area and would appear in Pai's 1983 novel ''Crystal Boys

''Crystal Boys'' (孽子, pinyin: ''Nièzǐ'', "sons of sin") is a novel written by author Pai Hsien-yung and first published in 1983 in Taiwan. In 1988, this novel went into circulation in China; its French and English translations were publi ...

''. ''Crystal Boys'' is set in 1970s Taipei and covers the main character Li-Qing's life after he is expelled from school for engaging in sexual relations with his classmate Zhao Ying. It is commonly identified as "the first Chinese novel that depicts the life struggles in the homosexual community ndgrew out of the particular socio-historical environment of Taiwan in the 1970s." Other works published in Taiwan in the early 1960s include Chiang Kuei's ''Double Suns'' (1961), with depictions of male homosexual desire, and Kuo Liang-hui

Kuo Liang-hui (; 17 August 1926 in Kaifeng, Henan – 19 June 2013 in Taiwan) was a Taiwanese novelist. Several of her works were turned into films.

Early life

Kuo Liang-hui was born in the Juye County in Shandong Province. She completed h ...

's ''Green Is the Grass'' (1963), which follows two Taiwanese middle school boys who exhibit sexual and romantic desires toward each other. The status of ''Double Suns'' in the Taiwanese gay literature scene has been questioned since male homosexuality is not the main focus of the work. On this, Chi Ta-wei

Chi Ta-wei (, born February 3, 1972) is a Taiwanese writer.

Life

Chi Ta-wei was born in Taichung, Taiwan in 1972. He received B.A. and M.A. in the Department of Foreign Languages and Literatures (locally known as "Waiwenxi" at National Taiwa ...

comments on its influence and significance in the history of homosexual literature in Taiwan, writing that " underestimate he characters of Double Sunsand deem them 'not homosexual enough' is to truncate the history of literature and to regulate the ever-elusive homosexuality to a confined definition."

Gillian Freeman

Gillian Freeman (5 December 1929 – 23 February 2019) was an English writer. Her first book, ''The Liberty Man'', appeared while she was working as a secretary to the novelist Louis Golding. Her fictional diary, ''Nazi Lady: The Diaries of E ...

's 1961 novel ''The Leather Boys

''The Leather Boys'' is a 1964 British drama film directed by Sidney J. Furie and starring Rita Tushingham, Colin Campbell, and Dudley Sutton. The story is set in the very early 1960s ton-up boy era, just before the rocker subculture in Lon ...

'', originally published under the pseudonym Eliot George, tells the story of a gay relationship between two young working-class men in London, one married and the other a biker. It was the first novel to focus on love between young working-class men rather than aristocrats. James Baldwin followed ''Giovanni's Room'' with '' Another Country'' (1962), a "controversial bestseller" that "explicitly combines racial and sexual protests ... structured around the lives of eight racially, regionally, socioeconomically, and sexually diverse characters." John Rechy

John Francisco Rechy (born March 10, 1931) is a Mexican-American novelist and essayist. His novels are written extensively about gay culture in Los Angeles and wider America, among other subject matter. '' City of Night'', his debut novel publis ...

's ''City of Night

''City of Night'' is a novel written by John Rechy. It was originally published in 1963 in New York by ''Grove Press''. Earlier excerpts had appeared in '' Evergreen Review'', ''Big Table'', ''Nugget'', and ''The London Magazine''.

''City o ...

'' (1963) and ''Numbers

A number is a mathematical object used to count, measure, and label. The most basic examples are the natural numbers 1, 2, 3, 4, and so forth. Numbers can be represented in language with number words. More universally, individual numbers can ...

'' (1967) are graphic tales of male hustlers; ''City of Night'' has been called a "landmark novel" that "marked a radical departure from all other novels of its kind, and gave voice to a subculture that had never before been revealed with such acuity." Claude J. Summers

Claude J. Summers (born 1944) is an American literary scholar, and the William E. Stirton Professor Emeritus in the Humanities and Professor Emeritus of English at the University of Michigan-Dearborn. A native of Galvez, Louisiana, he was the third ...

wrote of Christopher Isherwood

Christopher William Bradshaw Isherwood (26 August 1904 – 4 January 1986) was an Anglo-American novelist, playwright, screenwriter, autobiographer, and diarist. His best-known works include '' Goodbye to Berlin'' (1939), a semi-autobiographical ...

's ''A Single Man

''A Single Man'' is a 2009 American historical drama film, period romantic drama film based on A Single Man (novel), the 1964 novel by Christopher Isherwood. The List of directorial debuts, directorial debut of fashion designer Tom Ford, the fi ...

'' (1964):

George Baxt

George Baxt (June 11, 1923 – June 28, 2003) was an American screenwriter and author of crime fiction, best remembered for creating the gay black detective, Pharaoh Love. Four of his novels were finalists for the Lambda Literary Award for Gay My ...

's ''A Queer Kind of Death'' (1966) introduced Pharaoh Love, the first gay black detective in fiction. The novel was met with considerable acclaim, and ''The New York Times'' critic Anthony Boucher

William Anthony Parker White (August 21, 1911 – April 29, 1968), better known by his pen name Anthony Boucher (), was an American author, critic, and editor who wrote several classic mystery novels, short stories, science fiction, and radio dr ...

wrote, "This is a detective story, and unlike any other that you have read. No brief review can attempt to convey its quality. I merely note that it deals with a Manhattan subculture wholly devoid of ethics or morality, that said readers may well find it 'shocking', that it is beautifully plotted and written with elegance and wit ... and that you must under no circumstances miss it." Love would be the central figure in two immediate sequels ''Swing Low Sweet Harriet'' (1967) and ''Topsy and Evil'' (1968) and also two later novels, ''A Queer Kind of Love'' (1994) and ''A Queer Kind of Umbrella'' (1995). Though released the same year that homosexual acts were partially decriminalised in England and Wales

England and Wales () is one of the Law of the United Kingdom#Legal jurisdictions, three legal jurisdictions of the United Kingdom. It covers the constituent countries England and Wales and was formed by the Laws in Wales Acts 1535 and 1542. Th ...

by the Sexual Offences Act 1967

The Sexual Offences Act 1967 (c. 60) is an act of Parliament in the United Kingdom. It legalised homosexual acts in England and Wales, on the condition that they were consensual, in private and between two men who had attained the age of 21. ...

, the 1967 gay thriller '' The Wrong People'' by British author Robin Maugham

Robert Cecil Romer Maugham, 2nd Viscount Maugham (17 May 1916 – 13 March 1981), known as Robin Maugham, was a British author.

Trained as a barrister, he served with distinction in the Second World War, and wrote a successful novella, '' The ...

was originally published under the pseudonym David Griffin because its frank depiction of pederasty

Pederasty or paederasty () is a sexual relationship between an adult man and an adolescent boy. It was a socially acknowledged practice in Ancient Greece and Rome and elsewhere in the world, such as Pre-Meiji Japan.

In most countries today, ...

and sex trafficking

Sex trafficking is human trafficking for the purpose of sexual exploitation. Perpetrators of the crime are called sex traffickers or pimps—people who manipulate victims to engage in various forms of commercial sex with paying customers. Se ...

were considered so scandalous. In his controversial 1968 satire

Satire is a genre of the visual, literary, and performing arts, usually in the form of fiction and less frequently non-fiction, in which vices, follies, abuses, and shortcomings are held up to ridicule, often with the intent of exposin ...

''Myra Breckinridge

''Myra Breckinridge'' is a 1968 satirical novel by Gore Vidal written in the form of a diary. Described by the critic Dennis Altman as "part of a major cultural assault on the assumed norms of gender and sexuality which swept the western world ...

'', Gore Vidal explored the mutability of gender-roles and sexual-orientation as being social constructs established by social mores

Mores (, sometimes ; , plural form of singular , meaning "manner, custom, usage, or habit") are social norms that are widely observed within a particular society or culture. Mores determine what is considered morally acceptable or unacceptable ...

, making the eponymous heroine a transsexual

A transsexual person is someone who experiences a gender identity that is inconsistent with their assigned sex, and desires to permanently transition to the sex or gender with which they identify, usually seeking medical assistance (incl ...

waging a "war against gender roles".

In 1969, Taiwanese author Lin Hwai-min

Lin Hwai-min (; born 19 February 1947) is a Taiwanese dancer, writer, choreographer, and founder of Cloud Gate Dance Theater of Taiwan.

Biography

Family

Lin was born in Xingang, Chiayi. He came from an intellectual family. His great-grandfathe ...

published "Cicada" in his short story collection of the same name, ''Cicada''. "Cicada" follows the lives of several college students living in Ximending

Ximending is a neighborhood and shopping district in the Wanhua District of Taipei, Taiwan. The Ximending Pedestrian Area was the first pedestrian zone constructed in Taipei and remains the largest in Taiwan.

History Name

The area is named aft ...

, Taipei, who explore and struggle with expressing homosexual desires for each other.

Fifteen years after ''Advise and Consent'', Drury wrote about the unrequited love of one male astronaut for another in his 1971 novel '' The Throne of Saturn'', and in his two-part tale of ancient Egypt

Ancient Egypt () was a cradle of civilization concentrated along the lower reaches of the Nile River in Northeast Africa. It emerged from prehistoric Egypt around 3150BC (according to conventional Egyptian chronology), when Upper and Lower E ...

ian Pharaoh

Pharaoh (, ; Egyptian language, Egyptian: ''wikt:pr ꜥꜣ, pr ꜥꜣ''; Meroitic language, Meroitic: 𐦲𐦤𐦧, ; Biblical Hebrew: ''Parʿō'') was the title of the monarch of ancient Egypt from the First Dynasty of Egypt, First Dynasty ( ...

Akhenaten

Akhenaten (pronounced ), also spelled Akhenaton or Echnaton ( ''ʾŪḫə-nə-yātəy'', , meaning 'Effective for the Aten'), was an ancient Egyptian pharaoh reigning or 1351–1334 BC, the tenth ruler of the Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt, Eig ...

's attempt to change Egyptian religion—'' A God Against the Gods'' (1976) and '' Return to Thebes'' (1977)—Akhenaten's romance with his brother Smenkhkara contributes to his downfall. Tormented homosexual North McAllister is one of the ensemble of Alpha Zeta fraternity brothers and their families that Drury follows over the course of 60 years in his ''University'' novels (1990–1998), as well as René Suratt—villain and "bisexual seducer of students"—and the tragic lovers Amos Wilson and Joel. Assessing Drury's body of work in 1999, Erik Tarloff suggested in ''The New York Times'' that "homosexuality does appear to be the only minority status to which Drury seems inclined to accord much sympathy."

Though Thomas Pynchon

Thomas Ruggles Pynchon Jr. ( , ; born May 8, 1937) is an American novelist noted for his dense and complex novels. His fiction and non-fiction writings encompass a vast array of subject matter, Literary genre, genres and Theme (narrative), th ...

's ''Gravity's Rainbow

''Gravity's Rainbow'' is a 1973 novel by the American writer Thomas Pynchon. The narrative is set primarily in Europe at the end of World War II and centers on the design, production and dispatch of V-2 rockets by the German military. In partic ...

'' (1973) was unanimously recommended by the Pulitzer Prize

The Pulitzer Prizes () are 23 annual awards given by Columbia University in New York City for achievements in the United States in "journalism, arts and letters". They were established in 1917 by the will of Joseph Pulitzer, who had made his fo ...

fiction jury to receive the 1974 award, the Pulitzer board chose instead to make no award that year. In 2005 ''Time

Time is the continuous progression of existence that occurs in an apparently irreversible process, irreversible succession from the past, through the present, and into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequ ...

'' named the novel one of its "All-Time 100 Greatest Novels", a list of the best English language novels from 1923 to 2005. Other notable novels from the 1970s include Manuel Puig

Juan Manuel Puig Delledonne (December 28, 1932 – July 22, 1990), commonly called Manuel Puig, was an Argentine author. Among his best-known novels are '' La traición de Rita Hayworth'' ('' Betrayed by Rita Hayworth'', 1968), ''Boquitas pin ...

's '' Kiss of the Spider Woman'' (1976), Andrew Holleran

Andrew Holleran is the pseudonym of Eric Garber (born 1944), an American novelist, essayist, and short story writer, born on the island of Aruba. Most of his adult life has been spent in New York City, Washington, D.C., and a small town in Florid ...

's ''Dancer from the Dance

''Dancer from the Dance'' is a 1978 gay novel by Andrew Holleran (pen name of Eric Garber) about gay men in New York City and Fire Island.

Plot summary

The novel revolves around two main characters: Anthony Malone, a young man from the Midw ...

'' (1978), and ''Tales of the City

''Tales of the City'' is a series of ten novels written by American author Armistead Maupin from 1978 to 2024, depicting the life of a group of friends in San Francisco, many of whom are LGBTQ. The stories from ''Tales'' were originally seri ...

'' (1978), the first volume of Armistead Maupin

Armistead Jones Maupin, Jr. ( ; born May 13, 1944) is an American writer notable for '' Tales of the City'', a series of novels set in San Francisco.

Early life

Maupin was born in Washington, D.C., to Diana Jane (Barton) and Armistead Jones Maup ...

's long-running ''Tales of the City'' series. David Jackson of ''The New York Review of Books

''The New York Review of Books'' (or ''NYREV'' or ''NYRB'') is a semi-monthly magazine with articles on literature, culture, economics, science and current affairs. Published in New York City, it is inspired by the idea that the discussion of ...

'' wrote in 1979, "Homosexual love and/or attraction have become such standard spices in today's fiction, one no longer is surprised at the taste in the dish."

In the 1980s, Edmund White

Edmund Valentine White III (January 13, 1940 – June 3, 2025) was an American novelist, memoirist, playwright, biographer, and essayist. A pioneering figure in LGBTQ and especially gay literature after the Stonewall riots, he wrote with ra ...

— who had cowritten the 1977 gay sex manual

Sex manuals are books which explain how to perform sexual practices; they also commonly feature advice on birth control, and sometimes on safe sex and sexual relationships.

Early sex manuals

In the Graeco-Roman era, a sex manual was written ...

''The Joy of Gay Sex

''The Joy of Gay Sex'' is a sex manual for men who have sex with men by Charles Silverstein and Edmund White. The book was first published in 1977 and was inspired by the bestselling 1972 book ''The Joy of Sex''. The original print run was for ...

'' — published the semiautobiographical novels ''A Boy's Own Story

''A Boy's Own Story'' is a 1982 semi-autobiographical novel by American novelist Edmund White.

Overview

''A Boy's Own Story'' is the first of a trilogy of novels, describing a boy's coming of age and documenting a young man's experience of homo ...

'' (1982) and ''The Beautiful Room Is Empty

''The Beautiful Room Is Empty'' is a 1988 semi-autobiographical novel by Edmund White.

It is the second of a trilogy of novels, being preceded by '' A Boy's Own Story'' (1982) and followed by '' The Farewell Symphony'' (1997). It depicts th ...

'' (1988). Bret Easton Ellis

Bret Easton Ellis (born March 7, 1964) is an American author and screenwriter. Ellis was one of the literary Brat Pack (literary), Brat Pack and is a self-proclaimed satirist whose trademark technique as a writer is the expression of extreme acts ...

also came to prominence with '' Less than Zero'' (1985), ''The Rules of Attraction

''The Rules of Attraction'' is a satirical black comedy novel by Bret Easton Ellis published in 1987. The novel follows a handful of rowdy and often promiscuous, spoiled bohemian students at a liberal arts college in 1980s New Hampshire, inclu ...

'' (1987) and later ''American Psycho

''American Psycho'' is a black comedy horror novel by American writer Bret Easton Ellis, published in 1991. The story is told in the First-person narrative, first-person by Patrick Bateman, a wealthy, narcissistic, and vain Manhattan investmen ...

'' (1991). Nobel Prize winner Roger Martin du Gard

Roger Martin du Gard (; 23 March 1881 – 22 August 1958) was a French novelist, winner of the 1937 Nobel Prize in Literature.

Biography

Trained as a paleographer and archivist, he brought to his works a spirit of objectivity and a scrupulous ...

's unfinished ''Lieutenant-Colonel de Maumort'', written between 1941 and 1958, was published posthumously in 1983. It explores adolescent homosexual relations and includes a fictional first-person account, written in 1944, of a brief tragic encounter between a young soldier and a bakery apprentice in rural France.

Colombian-born gay author Fernando Vallejo

Fernando Vallejo Rendón (born 1942 in Medellín, Colombia) is a Colombian-born novelist, filmmaker and essayist. He obtained Mexican nationality in 2007.

Biography

Vallejo was born and raised in Medellín, though he left his hometown early in ...

on 1994 published his semi-autobiographical novel ''Our Lady of the Assassins''. The novel deals with the topic of homosexuality in a secondary way, but it is notable for being set in the context of a Latin American country where it is a taboo.

Taiwanese author Chu T'ien-wen's '' Notes of a Desolate Man'' (1994) is written from the first-person perspective of a Taiwanese gay man. Chu compiled the experience of gay men in various cultures as portrayed through media to construct the narrative of ''Notes of a Desolate Man''. The novel has often been criticized by Taiwanese critics for its fragmentary structure and narrative, due to Chu's frequent use of quotations and references. Chu's "presumably heterosexual" and female identity has also inspired various different readings of the novel, as well as "a tension that has been used to serve very different sorts of sexual politics."

The following year, Chi Ta-wei

Chi Ta-wei (, born February 3, 1972) is a Taiwanese writer.

Life

Chi Ta-wei was born in Taichung, Taiwan in 1972. He received B.A. and M.A. in the Department of Foreign Languages and Literatures (locally known as "Waiwenxi" at National Taiwa ...

published ''Sensory World'' (1995), which is composed of short stories are significant because of their explicit discussion of sex, sexuality, gender, transgender

A transgender (often shortened to trans) person has a gender identity different from that typically associated with the sex they were sex assignment, assigned at birth.

The opposite of ''transgender'' is ''cisgender'', which describes perso ...

identity, and male homosexual desire. In 1997, Chi published ''Queer Carnival'', which contains a detailed list of Taiwanese queer

''Queer'' is an umbrella term for people who are non-heterosexual or non- cisgender. Originally meaning or , ''queer'' came to be used pejoratively against LGBTQ people in the late 19th century. From the late 1980s, queer activists began to ...

literature (covering themes of gay

''Gay'' is a term that primarily refers to a homosexual person or the trait of being homosexual. The term originally meant 'carefree', 'cheerful', or 'bright and showy'.

While scant usage referring to male homosexuality dates to the late ...

, lesbian

A lesbian is a homosexual woman or girl. The word is also used for women in relation to their sexual identity or sexual behavior, regardless of sexual orientation, or as an adjective to characterize or associate nouns with female homosexu ...

, transgender, and other sexuality and gender identities).

In 1997, the short story "Brokeback Mountain

''Brokeback Mountain'' is a 2005 American neo-Western romantic drama film directed by Ang Lee and produced by Diana Ossana and James Schamus. Adapted from Brokeback Mountain (short story), the 1997 short story by Annie Proulx, the screenplay ...

" written by Annie Proulx