Gaetano Bresci on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Gaetano Bresci (; 11 November 186922 May 1901) was an Italian anarchist who assassinated King

Umberto I of Italy

Umberto I (; 14 March 1844 – 29 July 1900) was King of Italy from 9 January 1878 until his assassination in 1900. His reign saw Italy's expansion into the Horn of Africa, as well as the creation of the Triple Alliance (1882), Triple Alliance a ...

. As a young weaver, his experiences with exploitation in the workplace drew him to anarchism

Anarchism is a political philosophy and Political movement, movement that seeks to abolish all institutions that perpetuate authority, coercion, or Social hierarchy, hierarchy, primarily targeting the state (polity), state and capitalism. A ...

. Bresci emigrated to the United States, where he became involved with other Italian immigrant anarchists in Paterson, New Jersey

Paterson ( ) is the largest City (New Jersey), city in and the county seat of Passaic County, New Jersey, Passaic County, in the U.S. state of New Jersey.Bava Beccaris massacre motivated him to return to Italy, where he planned to assassinate Umberto. Local police knew of his return but did not mobilize. Bresci killed the king in July 1900 during Umberto's scheduled appearance in

In 1898, Bresci received news of the Bava Beccaris massacre. Protests in

In 1898, Bresci received news of the Bava Beccaris massacre. Protests in  On the morning of 29 July 1900, after preparing his weapon and thoroughly grooming himself, Bresci left his hotel intent on assassinating the king at the end of the contest. He spent most of the day walking around town and eating ice cream, briefly stopping for lunch with a stranger, whom he told, "Look at me carefully, because you will perhaps remember me for the rest of your life." That evening at 21:30, Umberto took his car to the stadium, where he was to hand out medals to the competition's athletes at 22:00. There were very few law enforcement agents () stationed along the route and not enough to effectively carry out

On the morning of 29 July 1900, after preparing his weapon and thoroughly grooming himself, Bresci left his hotel intent on assassinating the king at the end of the contest. He spent most of the day walking around town and eating ice cream, briefly stopping for lunch with a stranger, whom he told, "Look at me carefully, because you will perhaps remember me for the rest of your life." That evening at 21:30, Umberto took his car to the stadium, where he was to hand out medals to the competition's athletes at 22:00. There were very few law enforcement agents () stationed along the route and not enough to effectively carry out

A month after the assassination, Bresci was tried, convicted, and sentenced in a single day on 30 August 1900. His lawyer,

A month after the assassination, Bresci was tried, convicted, and sentenced in a single day on 30 August 1900. His lawyer,  Bresci was convicted of murder and sentenced to life imprisonment, the most severe punishment available, as Italy had already abolished the

Bresci was convicted of murder and sentenced to life imprisonment, the most severe punishment available, as Italy had already abolished the

On 22 May 1901, Bresci was found hanging by the neck in his cell. ''Vengeance'' had been carved into the wall. With his cell under constant surveillance, Bresci had apparently hanged himself while one of his guards was asleep and the other was using the toilet. The prison director reported that Bresci had hanged himself from his cell window using a towel – which prisoners were prohibited from possessing – knotted to the collar of his jacket. All of this occurred at a time that Bresci was awaiting the results of an appeal to Italy's Supreme Court of Cassation. He also left wine and cheese uneaten, which he had reportedly purchased that morning.

Upon receiving word of Bresci's death, Giolitti immediately dispatched a prison inspector to Santo Stefano, where he reportedly arrived late on the night of 22 May. The inspector and three physicians autopsied Bresci and confirmed that he had died of strangulation but also found that his body had undergone a level of

On 22 May 1901, Bresci was found hanging by the neck in his cell. ''Vengeance'' had been carved into the wall. With his cell under constant surveillance, Bresci had apparently hanged himself while one of his guards was asleep and the other was using the toilet. The prison director reported that Bresci had hanged himself from his cell window using a towel – which prisoners were prohibited from possessing – knotted to the collar of his jacket. All of this occurred at a time that Bresci was awaiting the results of an appeal to Italy's Supreme Court of Cassation. He also left wine and cheese uneaten, which he had reportedly purchased that morning.

Upon receiving word of Bresci's death, Giolitti immediately dispatched a prison inspector to Santo Stefano, where he reportedly arrived late on the night of 22 May. The inspector and three physicians autopsied Bresci and confirmed that he had died of strangulation but also found that his body had undergone a level of

Although the assassination was condemned by some anarchists, including Errico Malatesta, who rejected revenge killings and worried it might harm the anarchist cause, it was praised by others. The assassination quickly became a cornerstone of Italian

Although the assassination was condemned by some anarchists, including Errico Malatesta, who rejected revenge killings and worried it might harm the anarchist cause, it was praised by others. The assassination quickly became a cornerstone of Italian

The assassination directly inspired the Polish-American anarchist

The assassination directly inspired the Polish-American anarchist

Monza

Monza (, ; ; , locally ; ) is a city and ''comune'' (municipality) on the Lambro, River Lambro, a tributary of the Po (river), River Po, in the Lombardy region of Italy, about north-northeast of Milan. It is the capital of the province of Mo ...

amid a sparse police presence.

The government of Italy

The government of Italy is that of a democratic republic, established by the Italian constitution in 1948. It consists of Legislature, legislative, Executive (government), executive, and Judiciary, judicial subdivisions, as well as of a head of ...

suspected that Bresci had been a part of a conspiracy

A conspiracy, also known as a plot, ploy, or scheme, is a secret plan or agreement between people (called conspirers or conspirators) for an unlawful or harmful purpose, such as murder, treason, or corruption, especially with a political motivat ...

but no evidence was found to indicate that others were involved. He was consequently sentenced to life imprisonment

Life imprisonment is any sentence (law), sentence of imprisonment under which the convicted individual is to remain incarcerated for the rest of their natural life (or until pardoned or commuted to a fixed term). Crimes that result in life impr ...

for murder and confined on Santo Stefano Island in Latina, Lazio, where he was found dead of an apparent suicide within the year. After his death, Bresci gained the status of a martyr

A martyr (, ''mártys'', 'witness' Word stem, stem , ''martyr-'') is someone who suffers persecution and death for advocating, renouncing, or refusing to renounce or advocate, a religious belief or other cause as demanded by an external party. In ...

within the Italian anarchist movement, who defended his regicidal act. Bresci inspired some anarchists to carry out their own acts of propaganda by deed, most prominently Leon Czolgosz

Leon Frank Czolgosz ( ; ; May 5, 1873 – October 29, 1901) was an American wireworker and Anarchism, anarchist who assassination of William McKinley, assassinated President of the United States, United States president William McKinley on Septe ...

's assassination of United States president William McKinley

William McKinley (January 29, 1843September 14, 1901) was the 25th president of the United States, serving from 1897 until Assassination of William McKinley, his assassination in 1901. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Repub ...

. Italian anarchists erected a monument to Bresci in Carrara

Carrara ( ; ; , ) is a town and ''comune'' in Tuscany, in central Italy, of the province of Massa and Carrara, and notable for the white or blue-grey Carrara marble, marble quarried there. It is on the Carrione River, some Boxing the compass, ...

despite governmental attempts to block it.

Early life

On 11 November 1869, Gaetano Bresci was born into a lower middle-class family inPrato

Prato ( ; ) is a city and municipality (''comune'') in Tuscany, Italy, and is the capital of the province of Prato. The city lies in the northeast of Tuscany, at an elevation of , at the foot of Monte Retaia (the last peak in the Calvana ch ...

, Tuscany. The son of Gaspero Bresci and Maddalena Godi, his parents owned a small amount of land in , where they farmed grapes, olives, and wheat. His older brothers, Lorenzo and Angiolo, respectively worked as a shoemaker

Shoemaking is the process of making footwear.

Originally, shoes were made one at a time by hand, often by groups of shoemakers, or '' cordwainers'' (sometimes misidentified as cobblers, who repair shoes rather than make them). In the 18th cen ...

and as an officer in the Italian military. In 1880, the Kingdom of Italy

The Kingdom of Italy (, ) was a unitary state that existed from 17 March 1861, when Victor Emmanuel II of Kingdom of Sardinia, Sardinia was proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy, proclaimed King of Italy, until 10 June 1946, when the monarchy wa ...

began importing cheap grain from the United States, which economically devastated small farmers like the Brescis. As the price of grain fell, the family fell into poverty

Poverty is a state or condition in which an individual lacks the financial resources and essentials for a basic standard of living. Poverty can have diverse Biophysical environmen ...

and Gaetano himself started working to support his family's income. He came to blame the Italian state for his family's experiences with poverty. When he was 11 years old, Bresci began an apprenticeship

Apprenticeship is a system for training a potential new practitioners of a trade or profession with on-the-job training and often some accompanying study. Apprenticeships may also enable practitioners to gain a license to practice in a regulat ...

as a weaver at a textile factory. On Sundays, he attended a vocational school

A vocational school (alternatively known as a trade school, or technical school), is a type of educational institution, which, depending on the country, may refer to either secondary education#List of tech ed skills, secondary or post-secondar ...

, where he specialised in weaving silk

Silk is a natural fiber, natural protein fiber, some forms of which can be weaving, woven into textiles. The protein fiber of silk is composed mainly of fibroin and is most commonly produced by certain insect larvae to form cocoon (silk), c ...

. By the time he reached the age of 15, he had qualified to work as a silk weaver.

Bresci was radicalized by his experiences of exploitation in the workplace, and he joined the Italian anarchist movement. On 3 October 1892, Bresci and a group of about twenty anarchists confronted two police officers that had given a young worker a citation

A citation is a reference to a source. More precisely, a citation is an abbreviated alphanumeric expression embedded in the body of an intellectual work that denotes an entry in the bibliographic references section of the work for the purpose o ...

for not closing his butcher shop on time. Armed police dispersed the group and Bresci was later arrested for the act. On 27 December 1892, he was tried and found guilty of insulting the police. He was sentenced to 15 days in prison, and was subsequently marked in police files as a "dangerous anarchist".

Bresci was arrested again in 1895, after organising a textile workers' strike

Strike may refer to:

People

*Strike (surname)

* Hobart Huson, author of several drug related books

Physical confrontation or removal

*Strike (attack), attack with an inanimate object or a part of the human body intended to cause harm

* Airstrike, ...

, for which he was exiled to Lampedusa by the government of Francesco Crispi. During his on the island, Bresci studied anarchist literature and became further radicalized. Bresci was granted amnesty

Amnesty () is defined as "A pardon extended by the government to a group or class of people, usually for a political offense; the act of a sovereign power officially forgiving certain classes of people who are subject to trial but have not yet be ...

in 1896, and returned to the mainland. His status as an anarchist activist also followed him and he initially had difficulty finding work, before being hired to work at a wool factory. He developed a reputation as a dandy

A dandy is a man who places particular importance upon physical appearance and personal grooming, refined language and leisurely hobbies. A dandy could be a self-made man both in person and ''persona'', who emulated the aristocratic style of l ...

and engaged in numerous affairs, possibly fathering a child with one of his co-workers. Sustained economic difficulties, among other factors, soon led him to consider emigration.

In 1897, Bresci immigrated to the United States. From New York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

, Bresci moved to Hoboken, New Jersey

Hoboken ( ; ) is a City (New Jersey), city in Hudson County, New Jersey, Hudson County in the U.S. state of New Jersey. Hoboken is part of the New York metropolitan area and is the site of Hoboken Terminal, a major transportation hub. As of the ...

, where he met and married Sophie Kneiland, an Irish-American with whom he fathered two daughters: Madeleine and Gaetanina. To support his family, Bresci spent his weekdays working as a silk weaver in Paterson, New Jersey

Paterson ( ) is the largest City (New Jersey), city in and the county seat of Passaic County, New Jersey, Passaic County, in the U.S. state of New Jersey.photography

Photography is the visual arts, art, application, and practice of creating images by recording light, either electronically by means of an image sensor, or chemically by means of a light-sensitive material such as photographic film. It is empl ...

as a hobby. In Paterson, Bresci quickly became involved in the local trade unions and the immigrant anarchist movement. He briefly joined the Right to Existence Group (), but left after a few months as he found the group insufficiently radical. At one of the group's meetings, Bresci reportedly saved the life of Errico Malatesta

Errico Malatesta (4 December 1853 – 22 July 1932) was an Italian anarchist propagandist, theorist and revolutionary socialist. He edited several radical newspapers and spent much of his life exiled and imprisoned, having been jailed and expel ...

, when he disarmed a disgruntled individualist anarchist

Individualist anarchism or anarcho-individualism is a collection of anarchist currents that generally emphasize the individual and their will over external determinants such as groups, society, traditions, and ideological systems.

Individuali ...

who had shot and wounded Malatesta. Bresci also co-founded and financially supported its newspaper, '' La Questione Sociale'', for which he became a prolific " firebrand" contributor. He wrote to his brother that they benefitted from freedom of the press

Freedom of the press or freedom of the media is the fundamental principle that communication and expression through various media, including printed and electronic Media (communication), media, especially publication, published materials, shoul ...

and relative political equality

Politics () is the set of activities that are associated with making decisions in groups, or other forms of power relations among individuals, such as the distribution of status or resources.

The branch of social science that studies poli ...

in the United States, but that anti-Italian sentiments also ran high, recalling that Anglo-Americans

Anglo-Americans are a demographic group in Anglo-America. It typically refers to the predominantly European-descent nations and ethnic groups in the Americas that speak English as a native language, making up the majority of people in the world ...

called Italians "pigs".

Assassination of Umberto I

In 1898, Bresci received news of the Bava Beccaris massacre. Protests in

In 1898, Bresci received news of the Bava Beccaris massacre. Protests in Milan

Milan ( , , ; ) is a city in northern Italy, regional capital of Lombardy, the largest city in Italy by urban area and the List of cities in Italy, second-most-populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of nea ...

against the rising price of bread had been violently suppressed by the Royal Italian Army

The Royal Italian Army () (RE) was the land force of the Kingdom of Italy, established with the proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy. During the 19th century Italy started to unify into one country, and in 1861 Manfredo Fanti signed a decree c ...

, which fired on and killed many of the protestors. By this time, Bresci had fallen under the influence of the individualist anarchist Giuseppe Ciancabilla, an advocate of propaganda of the deed

Propaganda of the deed, or propaganda by the deed, is a type of direct action intended to influence public opinion. The action itself is meant to serve as an example for others to follow, acting as a catalyst for social revolution.

It is primari ...

. Bresci swore revenge against King Umberto I of Italy

Umberto I (; 14 March 1844 – 29 July 1900) was King of Italy from 9 January 1878 until his assassination in 1900. His reign saw Italy's expansion into the Horn of Africa, as well as the creation of the Triple Alliance (1882), Triple Alliance a ...

, who he held personally responsible for the massacre as he had decreed a state of siege in Milan and awarded a medal to Fiorenzo Bava Beccaris, the general who ordered the shooting.

Bresci requested that ''La Questione Sociale'' return $150 () which he had lent to them, and with it he bought a .32 S&W revolver and a one-way ticket back to Europe. They respectively cost him $7 () and $27 (), with the latter discounted for the occasion of the 1900 Paris Exposition. Before leaving, he told his wife that he was returning to resolve his deceased parents' estate. Bresci set sail in May 1900, disembarking at Le Havre

Le Havre is a major port city in the Seine-Maritime department in the Normandy (administrative region), Normandy region of northern France. It is situated on the right bank of the estuary of the Seine, river Seine on the English Channel, Channe ...

and briefly staying in Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

, before leaving for Italy. In June 1900, Bresci returned to his home city of Prato, where he stayed with his brother's family. Although the local police chief was aware of Bresci's presence and knew that police records had listed him as a "dangerous anarchist", the chief did not follow procedure of informing Italy's Ministry of the Interior

An interior ministry or ministry of the interior (also called ministry of home affairs or ministry of internal affairs) is a government department that is responsible for domestic policy, public security and law enforcement.

In some states, the ...

or retaining Bresci's passport. Unsurveilled, Bresci was free to practice firing his revolver daily.

In July 1900, Bresci visited his sister in Castel San Pietro Terme, before moving on to Milan. On 25 July, he toured Milan with his friend Luigi Granotti before traveling to Monza

Monza (, ; ; , locally ; ) is a city and ''comune'' (municipality) on the Lambro, River Lambro, a tributary of the Po (river), River Po, in the Lombardy region of Italy, about north-northeast of Milan. It is the capital of the province of Mo ...

. Bresci learned that Umberto was due to attend a gymnastics competition at the Royal Villa of Monza. Bresci found a room near the Monza train station and waited to strike. For two days, he scouted the area and inquired about the king's activities.

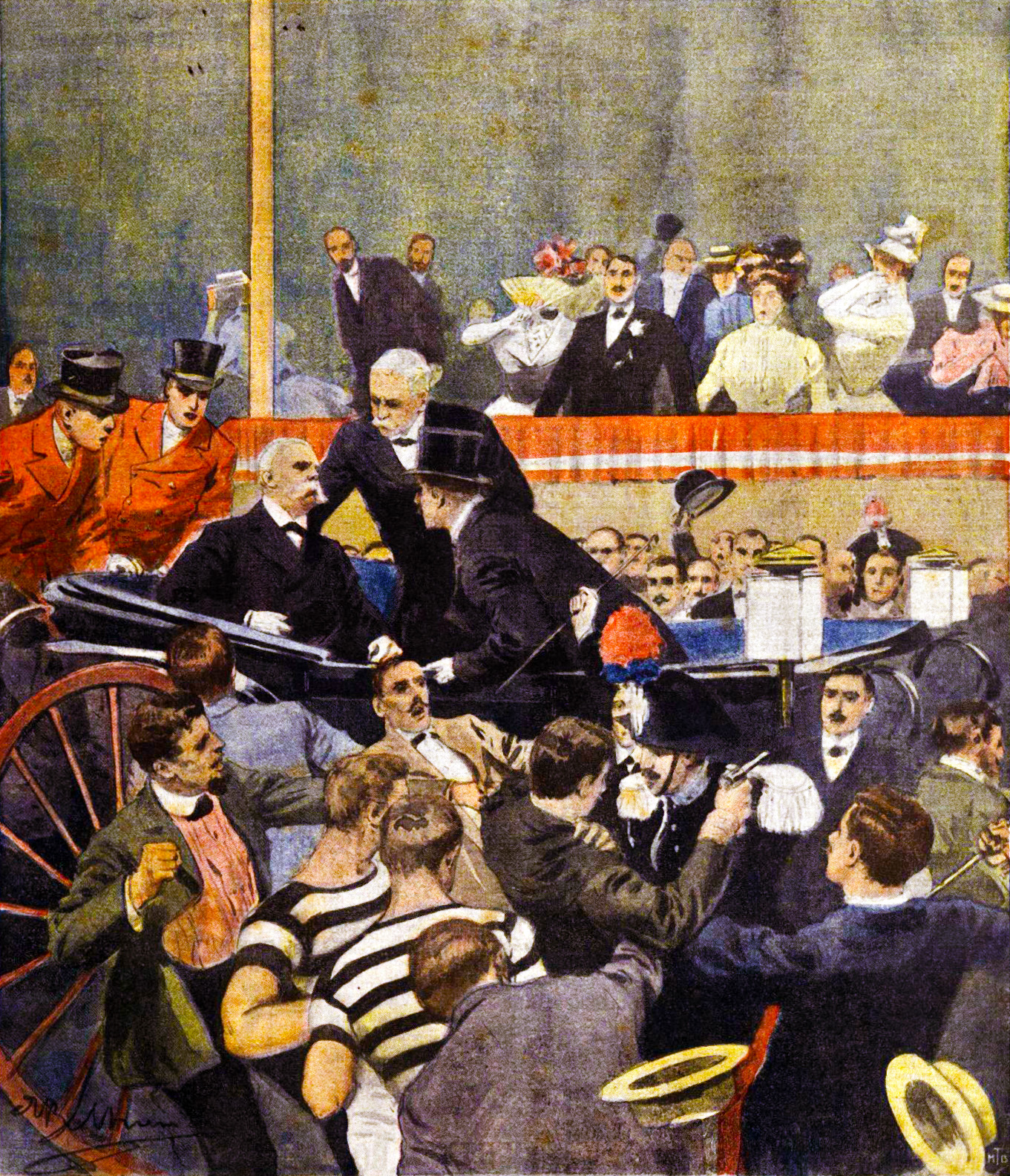

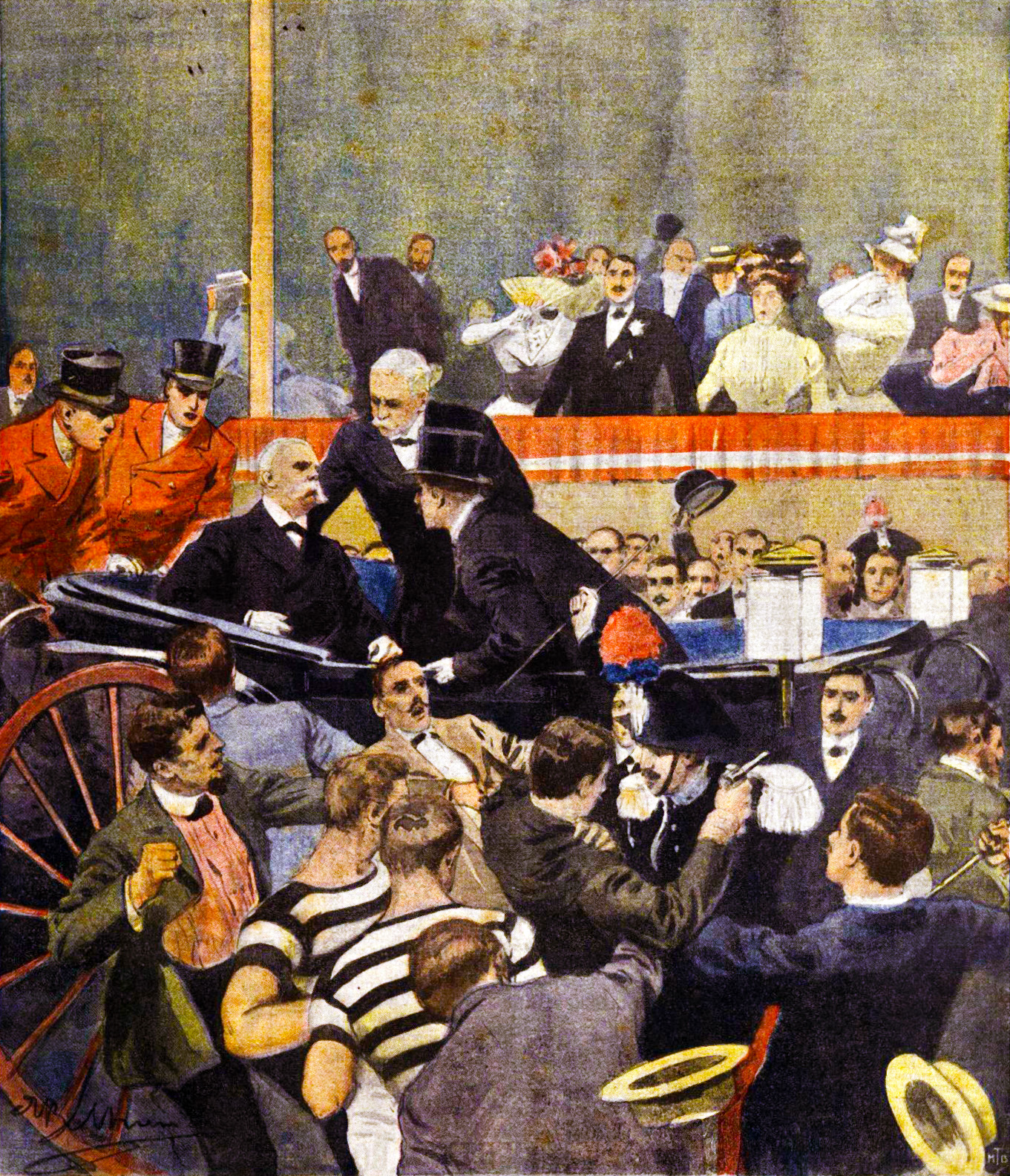

On the morning of 29 July 1900, after preparing his weapon and thoroughly grooming himself, Bresci left his hotel intent on assassinating the king at the end of the contest. He spent most of the day walking around town and eating ice cream, briefly stopping for lunch with a stranger, whom he told, "Look at me carefully, because you will perhaps remember me for the rest of your life." That evening at 21:30, Umberto took his car to the stadium, where he was to hand out medals to the competition's athletes at 22:00. There were very few law enforcement agents () stationed along the route and not enough to effectively carry out

On the morning of 29 July 1900, after preparing his weapon and thoroughly grooming himself, Bresci left his hotel intent on assassinating the king at the end of the contest. He spent most of the day walking around town and eating ice cream, briefly stopping for lunch with a stranger, whom he told, "Look at me carefully, because you will perhaps remember me for the rest of your life." That evening at 21:30, Umberto took his car to the stadium, where he was to hand out medals to the competition's athletes at 22:00. There were very few law enforcement agents () stationed along the route and not enough to effectively carry out crowd control

Crowd control is a public security practice in which large crowds are managed in order to prevent the outbreak of crowd crushes, affray, fights involving drunk and disorderly people or riots. Crowd crushes in particular can cause many hundre ...

at the stadium.

Bresci had positioned himself along the road exiting the stadium to give himself a chance at escape; the excited crowd swept him within three meters of the king's car and blocked his way out. While amongst the crowd, Bresci drew his revolver and shot Umberto three or four times. As the king lay dying, the angry crowd wrestled Bresci to the ground and a ''Carabinieri'' marshal intervened before Bresci could be lynched. He accepted arrest without resistance, declaring: "I did not kill Umberto. I have killed the King. I killed a principle."

Trial and conviction

A month after the assassination, Bresci was tried, convicted, and sentenced in a single day on 30 August 1900. His lawyer,

A month after the assassination, Bresci was tried, convicted, and sentenced in a single day on 30 August 1900. His lawyer, Francesco Saverio Merlino

Francesco Saverio Merlino (9 September 1856 – 30 June 1930) was an Italian lawyer, anarchist activist and theorist of libertarian socialism.

During his law studies at the University of Naples Federico II, Merlino joined the International Wor ...

, argued that the idolization of kings had weakened Italy and that the criminalization of the anarchist movement had directly led to Umberto's assassination. He proposed that the decriminalization

Decriminalization or decriminalisation is the legislative process which removes prosecutions against an action so that the action remains illegal but has no criminal penalties or at most some civil fine. This reform is sometimes applied retroacti ...

of radical ideologies and the resumption of civil liberties

Civil liberties are guarantees and freedoms that governments commit not to abridge, either by constitution, legislation, or judicial interpretation, without due process. Though the scope of the term differs between countries, civil liberties of ...

would put an end to propaganda of the deed

Propaganda of the deed, or propaganda by the deed, is a type of direct action intended to influence public opinion. The action itself is meant to serve as an example for others to follow, acting as a catalyst for social revolution.

It is primari ...

, the anarchist practice of political assassination. Bresci's character was further defended by his old foreman, a long-time co-worker, and his own wife, who herself expressed surprise that her husband could have committed the assassination. Examinations by the Italian criminologist Cesare Lombroso

Cesare Lombroso ( , ; ; born Ezechia Marco Lombroso; 6 November 1835 – 19 October 1909) was an Italian eugenicist, criminologist, phrenologist, physician, and founder of the Italian school of criminology. He is considered the founder of m ...

found no evidence of mental illness and the prosecution was thus unable to establish criminal insanity.

The government of Italy assumed Bresci had acted as part of a conspiracy. Interior minister Giovanni Giolitti

Giovanni Giolitti (; 27 October 1842 – 17 July 1928) was an Italian statesman. He was the prime minister of Italy five times between 1892 and 1921. He is the longest-serving democratically elected prime minister in Italian history, and the sec ...

was convinced the assassination had been plotted by Paterson anarchists such as Errico Malatesta together with the exiled Neapolitan Queen Maria Sophie of Bavaria, whom Giolitti alleged was planning to return to power in Italy. Another popular conspiracy theory

A conspiracy theory is an explanation for an event or situation that asserts the existence of a conspiracy (generally by powerful sinister groups, often political in motivation), when other explanations are more probable.Additional sources:

* ...

asserted that Giuseppe Ciancabilla had originally been selected as the assassin by a revolutionary committee in London, but was replaced by Bresci after he got into a conflict with Malatesta over the editorship of ''La Questione Sociale''. In the investigation that ensued after Bresci's trial, eleven of his associates – including his brother, travel companions, and epistolary partners – were arrested and held in solitary confinement under suspicion of collaborating on the assassination. They were finally released the following year, when the Milan appellate court

An appellate court, commonly called a court of appeal(s), appeal court, court of second instance or second instance court, is any court of law that is empowered to hear a case upon appeal from a trial court or other lower tribunal. Appel ...

found insufficient evidence of their involvement and dropped the charges. Further investigations in the United States likewise found no evidence of a conspiracy by Paterson anarchists to assassinate Umberto. The Italian diplomats and Saverio Fava were themselves left thoroughly dissatisfied with the "worthless" investigations conducted by the New York City Police Department

The City of New York Police Department, also referred to as New York City Police Department (NYPD), is the primary law enforcement agency within New York City. Established on May 23, 1845, the NYPD is the largest, and one of the oldest, munic ...

, United States Secret Service

The United States Secret Service (USSS or Secret Service) is a federal law enforcement agency under the Department of Homeland Security tasked with conducting criminal investigations and providing protection to American political leaders, thei ...

, and the Pinkerton detective agency.

death penalty

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty and formerly called judicial homicide, is the state-sanctioned killing of a person as punishment for actual or supposed misconduct. The sentence ordering that an offender be punished in s ...

. Bresci was initially held in Milan's San Vittore Prison, then transferred to a prison in Elba

Elba (, ; ) is a Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean island in Tuscany, Italy, from the coastal town of Piombino on the Italian mainland, and the largest island of the Tuscan Archipelago. It is also part of the Arcipelago Toscano National Park, a ...

, where he was illegally held in an underground cell below sea level. Fears of news leaking about the conditions of his imprisonment, combined with unrest among Bresci's supporters in the prison, resulted in his being transferred again on 23 January 1901. He was moved to solitary confinement

Solitary confinement (also shortened to solitary) is a form of imprisonment in which an incarcerated person lives in a single Prison cell, cell with little or no contact with other people. It is a punitive tool used within the prison system to ...

on the remote Santo Stefano Island, where he was held in a small, unfurnished cell, with his feet shackled.

Bresci was only allowed to keep a few personal items, such as clothing and hairstyling tool

Hairstyling tools may include hair irons (including flat and curling irons), hair dryers, hairbrushes (both flat and round), hair rollers, diffusers and various types of scissors.

Hair dressing might also include the use of Hairstyling product ...

s. His daily rations consisted largely of soup and bread, with meat on Sundays and public holidays, and occasional wine and cheese bought with money sent by his wife. For one hour of each day, he was permitted to exercise in the corridor outside his cell. The rest of his time was spent in solitary confinement, away from other prisoners and prohibited from receiving visitors and even his own guards were forbidden to speak to him. To keep himself entertained, he used a napkin as a makeshift football and read from a French dictionary. Bresci reportedly remained in high spirits throughout his time in prison, which the authorities reported was due to his belief that he would be freed in an imminent revolution

In political science, a revolution (, 'a turn around') is a rapid, fundamental transformation of a society's class, state, ethnic or religious structures. According to sociologist Jack Goldstone, all revolutions contain "a common set of elements ...

. By May 1901, Giolitti himself began to fear that Bresci's conspirators were planning to break him out of prison. To deter such a plot, Giolitti deployed an armed force to guard the island.

Death

On 22 May 1901, Bresci was found hanging by the neck in his cell. ''Vengeance'' had been carved into the wall. With his cell under constant surveillance, Bresci had apparently hanged himself while one of his guards was asleep and the other was using the toilet. The prison director reported that Bresci had hanged himself from his cell window using a towel – which prisoners were prohibited from possessing – knotted to the collar of his jacket. All of this occurred at a time that Bresci was awaiting the results of an appeal to Italy's Supreme Court of Cassation. He also left wine and cheese uneaten, which he had reportedly purchased that morning.

Upon receiving word of Bresci's death, Giolitti immediately dispatched a prison inspector to Santo Stefano, where he reportedly arrived late on the night of 22 May. The inspector and three physicians autopsied Bresci and confirmed that he had died of strangulation but also found that his body had undergone a level of

On 22 May 1901, Bresci was found hanging by the neck in his cell. ''Vengeance'' had been carved into the wall. With his cell under constant surveillance, Bresci had apparently hanged himself while one of his guards was asleep and the other was using the toilet. The prison director reported that Bresci had hanged himself from his cell window using a towel – which prisoners were prohibited from possessing – knotted to the collar of his jacket. All of this occurred at a time that Bresci was awaiting the results of an appeal to Italy's Supreme Court of Cassation. He also left wine and cheese uneaten, which he had reportedly purchased that morning.

Upon receiving word of Bresci's death, Giolitti immediately dispatched a prison inspector to Santo Stefano, where he reportedly arrived late on the night of 22 May. The inspector and three physicians autopsied Bresci and confirmed that he had died of strangulation but also found that his body had undergone a level of putrefaction

Putrefaction is the fifth stage of death, following pallor mortis, livor mortis, algor mortis, and rigor mortis. This process references the breaking down of a body of an animal Post-mortem interval, post-mortem. In broad terms, it can be view ...

suggesting that he had died earlier than reported. They raised this with the prison authorities but the matter was not investigated any further. On 26 May, Bresci was buried in the prison cemetery, interred with his belongings and letters from his wife that he had not been permitted to read. ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

'' celebrated the news of Bresci's death, while Umberto's successor and son, Victor Emmanuel III

Victor Emmanuel III (; 11 November 1869 – 28 December 1947) was King of Italy from 29 July 1900 until his abdication on 9 May 1946. A member of the House of Savoy, he also reigned as Emperor of Ethiopia from 1936 to 1941 and King of the Albani ...

, commented that it was "perhaps the best thing that could have happened to the unhappy man".

The circumstances of Bresci's death aroused suspicion and several 21st-century historians have suggested he was murdered. Investigations into Giolitti's papers in the Central Archives of the State found two empty folders pertaining to Bresci, the title of the first indicated that the prison inspector had actually arrived on the island on 18 May 1901. While looking further into the case, Italian journalist Arrigo Petacco found that Bresci's page in the Santo Stefano prison registry had been torn out.

Legacy

Governmental and policing reforms

Prior to Umberto's assassination by Bresci, thereactionary

In politics, a reactionary is a person who favors a return to a previous state of society which they believe possessed positive characteristics absent from contemporary.''The New Fontana Dictionary of Modern Thought'' Third Edition, (1999) p. 729. ...

government of Luigi Pelloux had been replaced by a left-wing government under Giuseppe Saracco of the Historical Left and Italy experienced a return to democracy

Democracy (from , ''dēmos'' 'people' and ''kratos'' 'rule') is a form of government in which political power is vested in the people or the population of a state. Under a minimalist definition of democracy, rulers are elected through competitiv ...

. Other than a series of arrests during the investigation of the case, the state repression Italian anarchists had expected in the wake of the assassination never actually manifested. Subsequent governments led by Giolitti passed a series of reforms of the Italian law enforcement apparatus, reining in police repression against striking workers. Giolitti downplayed or suppressed information about further violent attacks by anarchists, even omitting any mention of anarchism from his memoirs about Bresci's assassination, which he depicted as the result of a "deranged mind". Dissatisfied with the ineffectiveness of their foreign intelligence apparatus, as well as the investigations of the American authorities, the Italian government also established a new surveillance network to monitor emigrant Italian anarchists in Europe and the Americas.

British prime minister Robert Gascoyne-Cecil responded to the assassination by proclaiming that European governments had been too lenient towards anarchists, whose "morbid thirst for notoriety" he feared presented a threat to the existence of civilization. Switzerland passed a new law that punished expressions of support for crimes committed by anarchists, imprisoning Luigi Bertoni under this law after he publicly praised Bresci's actions. European governments that had participated in the International Conference of Rome for the Social Defense Against Anarchists also attempted to appeal to the United States government, calling for it to surveil the American anarchist movement and suppress the radical press. The United States Department of State

The United States Department of State (DOS), or simply the State Department, is an United States federal executive departments, executive department of the U.S. federal government responsible for the country's foreign policy of the United State ...

, without a federal law enforcement agency, responded that it lacked the means to carry out such an operation. Bresci's assassination of Umberto nevertheless contributed to a rising climate of xenophobia

Xenophobia (from (), 'strange, foreign, or alien', and (), 'fear') is the fear or dislike of anything that is perceived as being foreign or strange. It is an expression that is based on the perception that a conflict exists between an in-gr ...

and anti-anarchist sentiment in the United States, culminating in the passage of the Immigration Act of 1903, which prohibited anarchists from entering the country.

Regard in left-wing circles

Although the assassination was condemned by some anarchists, including Errico Malatesta, who rejected revenge killings and worried it might harm the anarchist cause, it was praised by others. The assassination quickly became a cornerstone of Italian

Although the assassination was condemned by some anarchists, including Errico Malatesta, who rejected revenge killings and worried it might harm the anarchist cause, it was praised by others. The assassination quickly became a cornerstone of Italian left-wing

Left-wing politics describes the range of Ideology#Political ideologies, political ideologies that support and seek to achieve social equality and egalitarianism, often in opposition to social hierarchy either as a whole or of certain social ...

counterculture, with 29 July being celebrated as an anarchist holiday. Many anarchists came to regard Bresci as a martyr. The American anarchist newspaper '' Free Society'' stated that anarchists regarded Bresci's actions with "unqualified approval". In its ode to Bresci, the paper described him as a "kind hearted and humane man" who had resolved to kill the "tyran Umberto, not as a representative of an organization but in an individual act of revenge for the "great suffering and misery caused by the oppressive measures of the Italian government". Bresci was praised in the same paper by Emma Goldman

Emma Goldman (June 27, 1869 – May 14, 1940) was a Russian-born Anarchism, anarchist revolutionary, political activist, and writer. She played a pivotal role in the development of anarchist political philosophy in North America and Europ ...

, who said he had "loved his kind, felt the existing wrongs in the world, and dared to strike a blow at organized authority". She described him as having had "overflowing sympathy with human suffering", and declared his assassination of Umberto to have been "good and noble, grand and useful", as she believed he had intended it to help "free mankind from tyranny". Anarchists in Yohoghany, Pennsylvania even sent a telegram to the Italian prime minister, celebrating the assassination of Umberto.

On Italian anarchist postcards, Bresci's face was superimposed onto the Statue of Liberty

The Statue of Liberty (''Liberty Enlightening the World''; ) is a colossal neoclassical sculpture on Liberty Island in New York Harbor, within New York City. The copper-clad statue, a gift to the United States from the people of French Thir ...

, and his deeds were eulogized in a poem by the American anarchist Voltairine de Cleyre and in Italian revolutionary music. Paterson became known as the "capital of world anarchism" after Bresci's assassination of Umberto. Although Bresci's wife did not know about her husband's plan to assassinate Umberto, or even what anarchism entailed, she was routinely surveilled by the police and harassed by members of her own community, forcing her to move to Chicago. When the Italian monarchist newspaper ''L'Araldo Italiano'' raised $1,000 () to decorate Umberto's tomb, the Paterson anarchists quickly matched the amount to support Bresci's widow and two daughters, despite police harassment at their fundraising events. Luigi Galleani was accused of embezzling funds raised for Bresci's children, but he denied the charges and published letters from Sophia Bresci and the benefit fund's organizer attesting to his innocence.

A Roman Catholic priest

The priesthood is the office of the ministers of religion, who have been commissioned ("ordained") with the holy orders of the Catholic Church. Technically, bishops are a priestly order as well; however, in common English usage ''priest'' re ...

was imprisoned for declaring his support for Bresci's actions, which he characterized as "an instrument of divine vengeance against a dynasty he House of Savoy">House_of_Savoy.html" ;"title="he he House of Savoythat had Roman question">deprived the Popes of their temporal power." In 1910, when he was still a member of the Italian Socialist Party">House of Savoy">he House of Savoythat had Roman question">deprived the Popes of their temporal power." In 1910, when he was still a member of the Italian Socialist Party, the future Italian fascist dictator Benito Mussolini praised Bresci in the pages of the socialist newspaper ''Lotta di Classe''. According to the Italian historian Gaetano Salvemini, Bresci received support from the majority of Italian society due to the unpopularity of Umberto I. Salvemini considered Bresci's assassination of Umberto to be an act of tyrannicide

Tyrannicide is the killing or assassination of a tyrant or unjust ruler, purportedly for the common good, and usually by one of the tyrant's subjects. Tyrannicide was legally permitted and encouraged in Classical Athens. Often, the term "tyrant ...

, which he contrasted with the indiscriminate attacks of terrorism

Terrorism, in its broadest sense, is the use of violence against non-combatants to achieve political or ideological aims. The term is used in this regard primarily to refer to intentional violence during peacetime or in the context of war aga ...

.

Further assassinations and attempts

Shortly after Umberto's death, the French anarchist François Salson attempted to assassinate the Persian kingMozaffar ad-Din Shah Qajar

Mozaffar ad-Din Shah Qajar (; 23 March 1853 – 3 January 1907) was the fifth Qajar shah of Iran, reigning from 1896 until his death in 1907. He is often credited with the creation of the Persian Constitution of 1906, which he approved of in ...

in Paris. Although Salson never disclosed his motives, international newspapers (including ''Corriere della Sera

(; ) is an Italian daily newspaper published in Milan with an average circulation of 246,278 copies in May 2023. First published on 5 March 1876, is one of Italy's oldest newspapers and is Italy's most read newspaper. Its masthead has remain ...

'', ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British Newspaper#Daily, daily Newspaper#National, national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its modern name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its si ...

'', and the ''New York Herald

The ''New York Herald'' was a large-distribution newspaper based in New York City that existed between 1835 and 1924. At that point it was acquired by its smaller rival the '' New-York Tribune'' to form the '' New York Herald Tribune''.

Hi ...

'') all claimed that the attempt had been directly inspired by Bresci's actions. Print media also linked Bresci's actions with those of Belgian anarchist Jean-Baptiste Sipido

Jean-Baptiste Victor Sipido (20 December 1884 – 20 August 1959) was a Belgium, Belgian anarchist who became known when he, then a young tinsmith's apprentice, attempted to assassinate Albert Edward, Prince of Wales (later Edward VII), at th ...

(who attempted to assassinate the British crown prince) and Italian anarchist Luigi Lucheni (who had assassinated Empress Elisabeth of Austria

Elisabeth (born Duchess Elisabeth Amalie Eugenie in Bavaria; 24 December 1837 – 10 September 1898), nicknamed Sisi or Sissi, was Empress of Austria and List of Hungarian consorts, Queen of Hungary from her marriage to Franz Joseph I of Austri ...

). Bresci and Lucheni shared little motive in common; Lucheni later expressed his admiration for Bresci's actions.

The assassination directly inspired the Polish-American anarchist

The assassination directly inspired the Polish-American anarchist Leon Czolgosz

Leon Frank Czolgosz ( ; ; May 5, 1873 – October 29, 1901) was an American wireworker and Anarchism, anarchist who assassination of William McKinley, assassinated President of the United States, United States president William McKinley on Septe ...

. According to his parents, Czolgosz obsessively read newspaper accounts of the assassination, keeping a clipping with him for months and reading it in bed each night. In May 1901, he inquired for information from an anarchist group in Cleveland

Cleveland is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Cuyahoga County. Located along the southern shore of Lake Erie, it is situated across the Canada–U.S. maritime border and approximately west of the Ohio-Pennsylvania st ...

about newspaper stories that American anarchists were plotting a similar assassination, but the group's treasurer denied the rumors. In early September, Czolgosz read an article in ''Free Society'' which exalted "monster-slayers" such as Bresci. This ultimately drove him to carry out the assassination

Assassination is the willful killing, by a sudden, secret, or planned attack, of a personespecially if prominent or important. It may be prompted by political, ideological, religious, financial, or military motives.

Assassinations are orde ...

of United States president William McKinley

William McKinley (January 29, 1843September 14, 1901) was the 25th president of the United States, serving from 1897 until Assassination of William McKinley, his assassination in 1901. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Repub ...

. In the wake of this assassination, mounting public pressure and police surveillance forced Bresci's family to flee their home in Cliffside Park, New Jersey.

Bresci and Czolgosz would later be a source of inspiration for the insurrectionary anarchist Luigi Galleani

Luigi Galleani (; 12 August 1861 – 4 November 1931) was an Italian insurrectionary anarchism, insurrectionary anarchist and Communism, communist best known for his advocacy of "propaganda of the deed", a strategy of political assassinations ...

, who praised their actions in his newspaper ''Cronaca Sovversiva

''Cronaca Sovversiva'' (Subversive Chronicle) was an Italian-language, anarchism in the United States, United States–based anarchist newspaper associated with Luigi Galleani from 1903 to 1920. It is one of the country's most significant Anarc ...

''. In 1911, Italian anarchists inspired by Bresci planned to assassinate Victor Emanuele III and Giolitti at the Turin International

The Turin International was a world's fair held in Turin in 1911 titled ''Esposizione internazionale dell'industria e del lavoro''. It received 7,409,145 visits and covered 247 acres.

Summary

The fair opened on 29 April, was held just nine y ...

but were arrested before they could carry out their attack. Italian anarchists from Paterson and New York established groups in Bresci's name, while a group in Pittsburgh named themselves in the "Twenty-Ninth of July" group, in reference to the date of Umberto's assassination. By 1914, the New York-based Bresci Circle had reached 600 members, who met frequently on East Harlem

East Harlem, also known as Spanish Harlem, or , is a neighborhood of Upper Manhattan in New York City, north of the Upper East Side and bounded by 96th Street to the south, Fifth Avenue to the west, and the East and Harlem Rivers to the eas ...

's 106th Street. The group was implicated in a plot to assassinate John D. Rockefeller

John Davison Rockefeller Sr. (July 8, 1839 – May 23, 1937) was an American businessman and philanthropist. He was one of the List of richest Americans in history, wealthiest Americans of all time and one of the richest people in modern hist ...

, the richest person of the ''fin de siècle

"''Fin de siècle''" () is a French term meaning , a phrase which typically encompasses both the meaning of the similar English idiom '' turn of the century'' and also makes reference to the closing of one era and onset of another. Without co ...

'' era. The following year, the group was infiltrated by an undercover operation

A covert operation or undercover operation is a military or police operation involving a covert agent or troops acting under an assumed cover to conceal the identity of the party responsible.

US law

Under US law, the Central Intelligence Ag ...

and two of its members were convicted of plotting to bomb St. Patrick's Cathedral in Manhattan

Manhattan ( ) is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the Boroughs of New York City, five boroughs of New York City. Coextensive with New York County, Manhattan is the County statistics of the United States#Smallest, larg ...

. The group was also suspected of involvement in the 1919 United States anarchist bombings, and finally disbanded during the Palmer Raids

The Palmer Raids were a series of raids conducted in November 1919 and January 1920 by the United States Department of Justice under the administration of President Woodrow Wilson to capture and arrest suspected socialists, especially anarchist ...

. Bresci's example, along with that of the anarchist assassins Émile Henry, Michele Angiolillo and Paulí Pallàs, was later invoked by Nicola Sacco when he was on death row

Death row, also known as condemned row, is a place in a prison that houses inmates awaiting execution after being convicted of a capital crime and sentenced to death. The term is also used figuratively to describe the state of awaiting executio ...

.

Contemporary commemorations

In 1976, a street in Bresci's home town of Prato was named after him. During the 1980s, Tuscan anarchists commissioned a monument to Bresci to be erected in Turigliano, nearCarrara

Carrara ( ; ; , ) is a town and ''comune'' in Tuscany, in central Italy, of the province of Massa and Carrara, and notable for the white or blue-grey Carrara marble, marble quarried there. It is on the Carrione River, some Boxing the compass, ...

; it was blocked by the government. In July 1986, the Italian Communist Party

The Italian Communist Party (, PCI) was a communist and democratic socialist political party in Italy. It was established in Livorno as the Communist Party of Italy (, PCd'I) on 21 January 1921, when it seceded from the Italian Socialist Part ...

-controlled municipal council voted to allow the anarchists space in the to construct their monument to Bresci to the protest of monarchist activists and interior minister Oscar Luigi Scalfaro. Court proceedings were initiated against members of the council and of the "Bresci committee" but were all acquitted, as the proposed monument's inscription did not mention the assassination of Umberto. In 1990, it was erected overnight in the cemetery by Ugo Mazzucchelli, who turned himself in afterwards. In response, mayor declared that the council's resolution to allow the monument was still valid. Victor Emanuele III commissioned the Expiatory Chapel of Monza to commemorate the place where his father Umberto had been assassinated. In 2013, Bresci's name was adopted by a short-lived occupied social center in Catania

Catania (, , , Sicilian and ) is the second-largest municipality on Sicily, after Palermo, both by area and by population. Despite being the second city of the island, Catania is the center of the most densely populated Sicilian conurbation, wh ...

.

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Bresci, Gaetano 1869 births 1901 deaths 19th-century Italian criminals 20th-century Italian people Anarchist assassins Deaths by hanging Death conspiracy theories Italian anarchists Italian assassins Italian emigrants to the United States Italian prisoners sentenced to life imprisonment Italian people convicted of murder Italian people who died in prison custody Italian regicides Italian revolutionaries People convicted of murder by Italy People from Paterson, New Jersey People from the Province of Prato Prisoners sentenced to life imprisonment by Italy Prisoners who died in Italian detention Umberto I of Italy