G K Chesterton on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

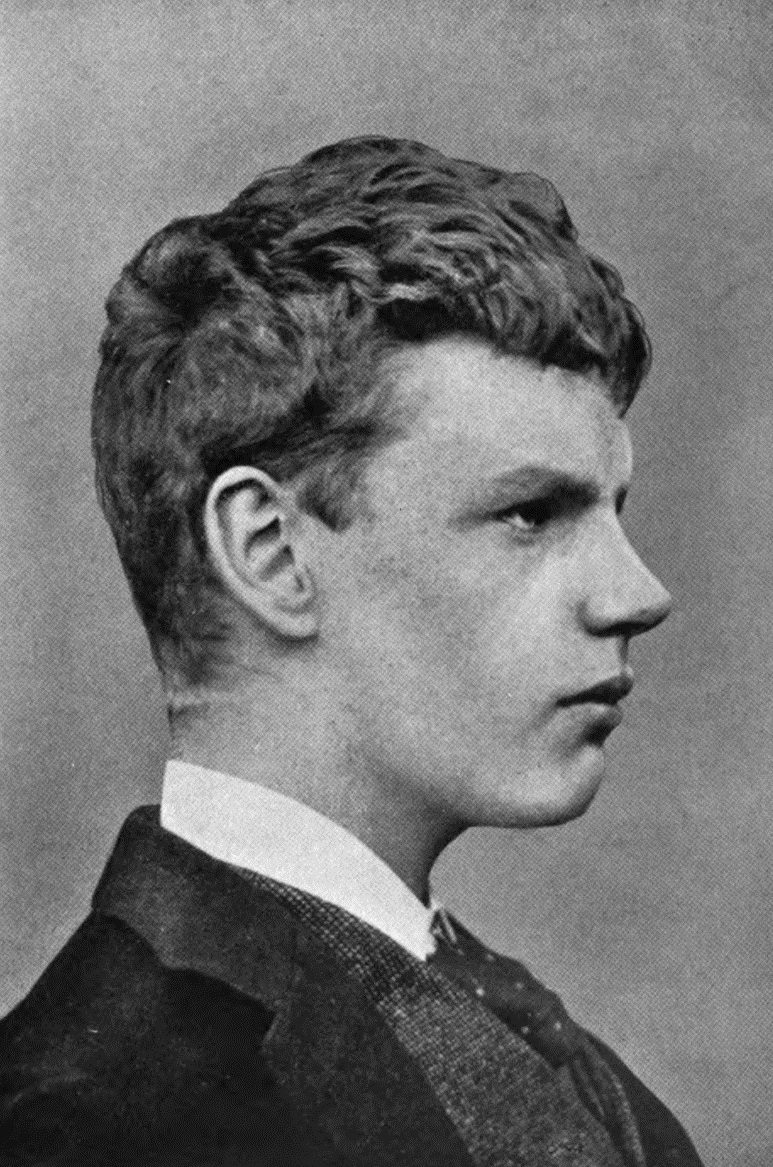

Gilbert Keith Chesterton (29 May 1874 – 14 June 1936) was an English

Chesterton was born in

Chesterton was born in

Chesterton died of

Chesterton died of

Chesterton faced accusations of

Chesterton faced accusations of

Inspired by Leo XIII's encyclical ''

Inspired by Leo XIII's encyclical ''

"The Trees of Pride"

1922 * "The Crime of the Communist", ''Collier's Weekly'', July 1934. * "The Three Horsemen", ''Collier's Weekly'', April 1935. * "The Ring of the Lovers", ''Collier's Weekly'', April 1935. * "A Tall Story", ''Collier's Weekly'', April 1935. * "The Angry Street – A Bad Dream", ''Famous Fantastic Mysteries'', February 1947.

''Gilbert Keith Chesterton''

London: Chelsea Publishing Company. * Cammaerts, Émile (1937). ''The Laughing Prophet: The Seven Virtues nd G. K. Chesterton''. London: Methuen & Co., Ltd. * Campbell, W. E. (1908)

"G. K. Chesterton: Inquisitor and Democrat"

''The Catholic World'', Vol. LXXXVIII, pp. 769–782. * Campbell, W. E. (1909)

"G. K. Chesterton: Catholic Apologist"

''The Catholic World'', Vol. LXXXIX, No. 529, pp. 1–12. * Chesterton, Cecil (1908)

''G. K. Chesterton: A Criticism''

London: Alston Rivers (Rep. b

John Lane Company

1909). * Clipper, Lawrence J. (1974). ''G. K. Chesterton''. New York: Twayne Publishers. * Coates, John (1984). ''Chesterton and the Edwardian Cultural Crisis''. Hull University Press. * Coates, John (2002). ''G. K. Chesterton as Controversialist, Essayist, Novelist, and Critic''.

"G. K. Chesterton"

In: ''Some Impressions of my Elders''. New York: The Macmillan Company, pp. 90–112. * * ''Gilbert Magazine'' (November/December 2008). Vol. 12, No. 2-3, ''Special Issue: Chesterton & The Jews''. * Haldane, John. 'Chesterton's Philosophy of Education', philosophy, Vol. 65, No. 251 (Jan. 1990), pp. 65–80. * Hitchens, Christopher (2012)

"The Reactionary"

''The Atlantic''. * Herts, B. Russell (1914)

"Gilbert K. Chesterton: Defender of the Discarded"

In: ''Depreciations''. New York: Albert & Charles Boni, pp. 65–86. * Hollis, Christopher (1970). ''The Mind of Chesterton''. London: Hollis & Carter. * Hunter, Lynette (1979). ''G. K. Chesterton: Explorations in Allegory''. London: Macmillan Press. * Jaki, Stanley (1986). ''Chesterton: A Seer of Science''. University of Illinois Press. * Jaki, Stanley (1986). "Chesterton's Landmark Year". In: ''Chance or Reality and Other Essays''. University Press of America. * Kenner, Hugh (1947). ''Paradox in Chesterton''. New York:

"G. K. Chesterton: Master of Rejuvenation"

''The New Criterion'', Vol. XXX, p. 26. * Kirk, Russell (1971). "Chesterton, Madmen, and Madhouses", ''Modern Age'', Vol. XV, No. 1, pp. 6–16. * Knight, Mark (2004). ''Chesterton and Evil''. Fordham University Press. * Lea, F. A. (1947). "G. K. Chesterton". In:

"G. K. Chesterton: A Practical Mystic"

''

"G. K. Chesterton on Rome and Germany"

In: ''Readers and Writers (1917–1921)''. London: George Allen & Unwin, pp. 155–161. * Oser, Lee (2007). ''The Return of Christian Humanism: Chesterton, Eliot, Tolkien, and the Romance of History''. University of Missouri Press. * * * Peck, William George (1920)

"Mr. G. K. Chesterton and the Return to Sanity"

In: ''From Chaos to Catholicism''. London: George Allen & Unwin, pp. 52–92. * Raymond, E. T. (1919)

"Mr. G. K. Chesterton"

In: ''All & Sundry''. London: T. Fisher Unwin, pp. 68–76. * Schall, James V. (2000). ''Schall on Chesterton: Timely Essays on Timeless Paradoxes''. Catholic University of America Press. * Scott, William T. (1912)

''Chesterton and Other Essays''

Cincinnati: Jennings & Graham. * Seaber, Luke (2011). ''G. K. Chesterton's Literary Influence on George Orwell: A Surprising Irony''.

"The Adventures of a Journalist: G. K. Chesterton"

In: ''The Catholic Spirit in Modern English Literature''. New York: The Macmillan Company, pp. 229–248. * Slosson, Edwin E. (1917)

"G. K. Chesterton: Knight Errant of Orthodoxy"

In: ''Six Major Prophets''. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, pp. 129–189. * Smith, Marion Couthouy (1921)

"The Rightness of G. K. Chesterton"

''The Catholic World'', Vol. CXIII, No. 678, pp. 163–168. * Stapleton, Julia (2009). ''Christianity, Patriotism, and Nationhood: The England of G. K. Chesterton''. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books. * * Tonquédec, Joseph de (1920)

''G. K. Chesterton, ses Idées et son Caractère''

Nouvelle Librairie National. * Ward, Maisie (1952). ''Return to Chesterton'', London: Sheed & Ward. * West, Julius (1915)

''G. K. Chesterton: A Critical Study''

London: Martin Secker. *

Works by G. K. Chesterton

at

What's Wrong: GKC in Periodicals

Articles by G. K. Chesterton in periodicals, with critical annotations. * .

G. K. Chesterton: Quotidiana

G. K. Chesterton research collection

at The Marion E. Wade Center at Wheaton College

G. K. Chesterton Archival Collection

at the University of St. Michael's College at the

author

In legal discourse, an author is the creator of an original work that has been published, whether that work exists in written, graphic, visual, or recorded form. The act of creating such a work is referred to as authorship. Therefore, a sculpt ...

, philosopher

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, Value (ethics and social sciences), value, mind, and language. It is a rational an ...

, Christian apologist

Christian apologetics (, "verbal defense, speech in defense") is a branch of Christian theology that defends Christianity.

Christian apologetics have taken many forms over the centuries, starting with Paul the Apostle in the early church and Pa ...

, journalist and magazine editor, and literary

Literature is any collection of written work, but it is also used more narrowly for writings specifically considered to be an art form, especially novels, plays, and poems. It includes both print and digital writing. In recent centuries, ...

and art critic

An art critic is a person who is specialized in analyzing, interpreting, and evaluating art. Their written critiques or reviews contribute to art criticism and they are published in newspapers, magazines, books, exhibition brochures, and catalogue ...

.

Chesterton created the fictional priest-detective Father Brown

Father Brown is a fictional Roman Catholic priest and amateur detective. He is featured in 53 short stories by English author G. K. Chesterton, published between 1910 and 1936. Father Brown solves mysteries and crimes using his intuition and ...

, and wrote on apologetics

Apologetics (from Greek ) is the religious discipline of defending religious doctrines through systematic argumentation and discourse. Early Christian writers (c. 120–220) who defended their beliefs against critics and recommended their f ...

, such as his works ''Orthodoxy

Orthodoxy () is adherence to a purported "correct" or otherwise mainstream- or classically-accepted creed, especially in religion.

Orthodoxy within Christianity refers to acceptance of the doctrines defined by various creeds and ecumenical co ...

'' and ''The Everlasting Man

''The Everlasting Man'' is a Christian apologetics book written by G. K. Chesterton, published in 1925. It is, to some extent, a deliberate rebuttal of H. G. Wells' '' The Outline of History'', disputing Wells' portrayals of human life and civ ...

''. Chesterton routinely referred to himself as an orthodox

Orthodox, Orthodoxy, or Orthodoxism may refer to:

Religion

* Orthodoxy, adherence to accepted norms, more specifically adherence to creeds, especially within Christianity and Judaism, but also less commonly in non-Abrahamic religions like Neo-pag ...

Christian, and came to identify this position more and more with Catholicism

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

, eventually converting from high church Anglicanism

A ''high church'' is a Christian Church whose beliefs and practices of Christian ecclesiology, liturgy, and theology emphasize "ritual, priestly authority, ndsacraments," and a standard liturgy. Although used in connection with various Christian ...

. Biographers have identified him as a successor to such Victorian authors as Matthew Arnold

Matthew Arnold (24 December 1822 – 15 April 1888) was an English poet and cultural critic. He was the son of Thomas Arnold, the headmaster of Rugby School, and brother to both Tom Arnold (academic), Tom Arnold, literary professor, and Willi ...

, Thomas Carlyle

Thomas Carlyle (4 December 17955 February 1881) was a Scottish essayist, historian, and philosopher. Known as the "Sage writing, sage of Chelsea, London, Chelsea", his writings strongly influenced the intellectual and artistic culture of the V ...

, John Henry Newman

John Henry Newman (21 February 1801 – 11 August 1890) was an English Catholic theologian, academic, philosopher, historian, writer, and poet. He was previously an Anglican priest and after his conversion became a cardinal. He was an ...

and John Ruskin

John Ruskin (8 February 1819 20 January 1900) was an English polymath a writer, lecturer, art historian, art critic, draughtsman and philanthropist of the Victorian era. He wrote on subjects as varied as art, architecture, Critique of politic ...

.

He has been referred to as the "prince of paradox

A paradox is a logically self-contradictory statement or a statement that runs contrary to one's expectation. It is a statement that, despite apparently valid reasoning from true or apparently true premises, leads to a seemingly self-contradictor ...

". Of his writing style, ''Time

Time is the continuous progression of existence that occurs in an apparently irreversible process, irreversible succession from the past, through the present, and into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequ ...

'' observed: "Whenever possible, Chesterton made his points with popular sayings, proverbs, allegories—first carefully turning them inside out." His writings were an influence on Jorge Luis Borges

Jorge Francisco Isidoro Luis Borges Acevedo ( ; ; 24 August 1899 – 14 June 1986) was an Argentine short-story writer, essayist, poet and translator regarded as a key figure in Spanish literature, Spanish-language and international literatur ...

, who compared his work with that of Edgar Allan Poe

Edgar Allan Poe (; January 19, 1809 – October 7, 1849) was an American writer, poet, editor, and literary critic who is best known for his poetry and short stories, particularly his tales involving mystery and the macabre. He is widely re ...

.

Biography

Early life

Chesterton was born in

Chesterton was born in Campden Hill

Campden Hill is a hill in Kensington, West London, bounded by Holland Park Avenue on the north, Kensington High Street on the south, Kensington Palace Gardens on the east and Abbotsbury Road on the west. The name derives from the former ''Camp ...

in Kensington

Kensington is an area of London in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, around west of Central London.

The district's commercial heart is Kensington High Street, running on an east–west axis. The north-east is taken up by Kensingt ...

, London, on 29 May 1874. His father was Edward Chesterton, an estate agent, and his mother was Marie Louise, Grosjean, of Swiss-French origin. Chesterton was baptised at the age of one month into the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the State religion#State churches, established List of Christian denominations, Christian church in England and the Crown Dependencies. It is the mother church of the Anglicanism, Anglican Christian tradition, ...

, though his family themselves were irregularly practising Unitarians

Unitarian or Unitarianism may refer to:

Christian and Christian-derived theologies

A Unitarian is a follower of, or a member of an organisation that follows, any of several theologies referred to as Unitarianism:

* Unitarianism (1565–present) ...

. According to his autobiography, as a young man he became fascinated with the occult

The occult () is a category of esoteric or supernatural beliefs and practices which generally fall outside the scope of organized religion and science, encompassing phenomena involving a 'hidden' or 'secret' agency, such as magic and mysti ...

and, along with his brother Cecil

Cecil may refer to:

People with the name

* Cecil (given name), a given name (including a list of people and fictional characters with the name)

* Cecil (surname), a surname (including a list of people with the name)

Places Canada

* Cecil, Alberta ...

, experimented with Ouija boards

The Ouija ( , ), also known as a Ouija board, spirit board, talking board, or witch board, is a flat board marked with the letters of the Latin alphabet, the numbers 0–9, the words "yes", "no", and occasionally "hello" and "goodbye", along ...

. He was educated at St Paul's School, then attended the Slade School of Art

The UCL Slade School of Fine Art (informally The Slade) is the art school of University College London (UCL) and is based in London, England. It has been ranked as the UK's top art and design educational institution. The school is organised as ...

to become an illustrator. The Slade is a department of University College London

University College London (Trade name, branded as UCL) is a Public university, public research university in London, England. It is a Member institutions of the University of London, member institution of the Federal university, federal Uni ...

, where Chesterton also took classes in literature, but he did not complete a degree in either subject. He married Frances Blogg

Frances Alice Blogg Chesterton (28 June 1869 – 12 December 1938) was an English author of verse, songs and school drama. The wife of G. K. Chesterton, she had a large role in his career as his amanuensis and personal manager.

Early life

Fran ...

in 1901; the marriage lasted the rest of his life. Chesterton credited Frances with leading him back to Anglicanism

Anglicanism, also known as Episcopalianism in some countries, is a Western Christianity, Western Christian tradition which developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the ...

, though he later considered Anglicanism to be a "pale imitation". He entered in full communion with the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

in 1922. The couple were unable to have children.

A friend from schooldays was Edmund Clerihew Bentley

Edmund Clerihew Bentley (10 July 1875 – 30 March 1956), who generally published under the names E. C. Bentley and E. Clerihew Bentley, was an English novelist and humorist and inventor of the clerihew, an irregular form of humorous verse ...

, inventor of the clerihew

A clerihew () is a whimsical, four-line biographical poem of a type invented by Edmund Clerihew Bentley. The first line is the name of the poem's subject, usually a famous person, and the remainder puts the subject in an absurd light or reveals so ...

, a whimsical four-line biographical poem. Chesterton himself wrote clerihews and illustrated his friend's first published collection of poetry, ''Biography for Beginners'' (1905), which popularised the clerihew form. He became godfather to Bentley's son, Nicolas

Nicolas or Nicolás may refer to:

People Given name

* Nicolas (given name)

Mononym

* Nicolas (footballer, born 1999), Brazilian footballer

* Nicolas (footballer, born 2000), Brazilian footballer

Surname Nicolas

* Dafydd Nicolas (c.1705–1774), ...

, and opened his novel ''The Man Who Was Thursday'' with a poem written to Bentley.

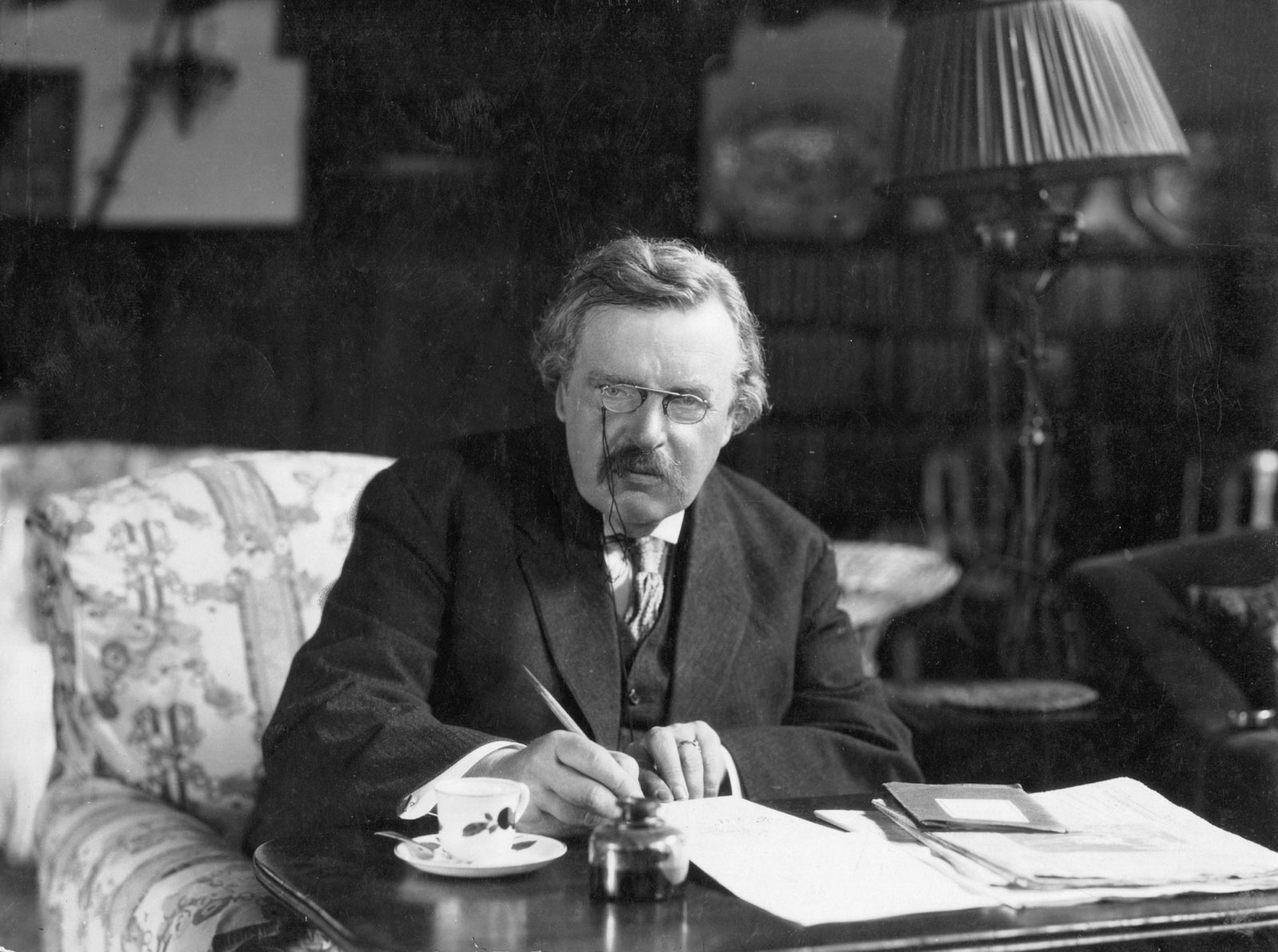

Career

In September 1895, Chesterton began working for the London publisher George Redway, where he remained for just over a year. In October 1896, he moved to the publishing house T. Fisher Unwin, where he remained until 1902. During this period he also undertook his first journalistic work, as a freelance art and literary critic. In 1902, '' The Daily News'' gave him a weekly opinion column, followed in 1905 by a weekly column in ''The Illustrated London News

''The Illustrated London News'', founded by Herbert Ingram and first published on Saturday 14 May 1842, was the world's first illustrated weekly news magazine. The magazine was published weekly for most of its existence, switched to a less freq ...

'', for which he continued to write for the next thirty years.

Early on Chesterton showed a great interest in and talent for art. He had planned to become an artist, and his writing shows a vision that clothed abstract ideas in concrete and memorable images. Father Brown

Father Brown is a fictional Roman Catholic priest and amateur detective. He is featured in 53 short stories by English author G. K. Chesterton, published between 1910 and 1936. Father Brown solves mysteries and crimes using his intuition and ...

is perpetually correcting the incorrect vision of the bewildered folks at the scene of the crime and wandering off at the end with the criminal to exercise his priestly role of recognition, repentance and reconciliation. For example, in the story "''The Flying Stars''", Father Brown entreats the character Flambeau to give up his life of crime: "There is still youth and honour and humour in you; don't fancy they will last in that trade. Men may keep a sort of level of good, but no man has ever been able to keep on one level of evil. That road goes down and down. The kind man drinks and turns cruel; the frank man kills and lies about it. Many a man I've known started like you to be an honest outlaw, a merry robber of the rich, and ended stamped into slime."

Chesterton loved to debate, often engaging in friendly public disputes with such men as George Bernard Shaw

George Bernard Shaw (26 July 1856 – 2 November 1950), known at his insistence as Bernard Shaw, was an Irish playwright, critic, polemicist and political activist. His influence on Western theatre, culture and politics extended from the 188 ...

, H. G. Wells

Herbert George Wells (21 September 1866 – 13 August 1946) was an English writer, prolific in many genres. He wrote more than fifty novels and dozens of short stories. His non-fiction output included works of social commentary, politics, hist ...

, Bertrand Russell

Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3rd Earl Russell, (18 May 1872 – 2 February 1970) was a British philosopher, logician, mathematician, and public intellectual. He had influence on mathematics, logic, set theory, and various areas of analytic ...

and Clarence Darrow

Clarence Seward Darrow (; April 18, 1857 – March 13, 1938) was an American lawyer who became famous in the 19th century for high-profile representations of trade union causes, and in the 20th century for several criminal matters, including the ...

. According to his autobiography, he and Shaw played cowboys in a silent film that was never released. On 7 January 1914 Chesterton (along with his brother Cecil

Cecil may refer to:

People with the name

* Cecil (given name), a given name (including a list of people and fictional characters with the name)

* Cecil (surname), a surname (including a list of people with the name)

Places Canada

* Cecil, Alberta ...

and future sister-in-law Ada

Ada may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* '' Ada or Ardor: A Family Chronicle'', a novel by Vladimir Nabokov

Film and television

* Ada, a character in 1991 movie '' Armour of God II: Operation Condor''

* '' Ada... A Way of Life'', a 2008 Bollywo ...

) took part in the mock-trial of John Jasper for the murder of Edwin Drood

''The Mystery of Edwin Drood'' is the final novel by English author Charles Dickens, originally published in 1870.

Though the novel is named after the character Edwin Drood, it focuses more on Drood's uncle, John Jasper, a precentor, choirma ...

. Chesterton was Judge and George Bernard Shaw played the role of foreman of the jury.

During the First World War, Chesterton was editing ''New Witness

''G.K.'s Weekly'' was a British publication founded in 1925 (with its pilot edition surfacing in late 1924) by writer G. K. Chesterton, continuing until his death in 1936. Its articles typically discussed topical cultural, political, and socio- ...

'' writing editorials, and publishing letters from writers and thinkers, such as Thomas Maynard, English poet and historian of the Catholic Church whose thinking was influenced by Chesterton's (1908) ''Orthodoxy

Orthodoxy () is adherence to a purported "correct" or otherwise mainstream- or classically-accepted creed, especially in religion.

Orthodoxy within Christianity refers to acceptance of the doctrines defined by various creeds and ecumenical co ...

''; and Hilaire Belloc

Joseph Hilaire Pierre René Belloc ( ; ; 27 July 187016 July 1953) was a French-English writer, politician, and historian. Belloc was also an orator, poet, sailor, satirist, writer of letters, soldier, and political activist. His Catholic fait ...

. In 1917, issues of ''New Witness'' shed light on these writers' moral concerns about the way the war was being fought on the home front, by commentary on "the 'Gordon Scandal'", the undercover agent alias "Alex Gordon

Alexander Jonathan Gordon (born February 10, 1984) is an American former professional baseball left fielder who played his entire career for the Kansas City Royals of Major League Baseball (MLB) from 2007 to 2020. Prior to playing professional ...

". This scandal was the refusal of the Attorney-General F.E. Smith to produce 'Gordon', the 'vanishing spy', for examination in court but on whose 'evidence' three defendants to conspiracy to murder (David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. A Liberal Party (United Kingdom), Liberal Party politician from Wales, he was known for leadi ...

and Arthur Henderson

Arthur Henderson (13 September 1863 – 20 October 1935) was a British iron moulder and Labour Party (UK), Labour politician. He was the first Labour Cabinet of the United Kingdom, cabinet minister, won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1934 and, uniqu ...

) were convicted and imprisoned (''R v Alice Wheeldon & Ors'', 1917).

Chesterton was a large man, standing tall and weighing around . His girth gave rise to an anecdote during the First World War, when a lady in London asked why he was not "out at the Front

Front may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Films

* ''The Front'' (1943 film), a 1943 Soviet drama film

* '' The Front'', 1976 film

Music

* The Front (band), an American rock band signed to Columbia Records and active in the 1980s and ...

"; he replied, "If you go round to the side, you will see that I am." On another occasion he remarked to his friend George Bernard Shaw, "To look at you, anyone would think a famine had struck England." Shaw retorted, "To look at you, anyone would think you had caused it." P. G. Wodehouse

Sir Pelham Grenville Wodehouse ( ; 15 October 1881 – 14 February 1975) was an English writer and one of the most widely read humorists of the 20th century. His creations include the feather-brained Bertie Wooster and his sagacious valet, Je ...

once described a very loud crash as "a sound like G. K. Chesterton falling onto a sheet of tin". Chesterton usually wore a cape and a crumpled hat, with a swordstick

A swordstick or cane-sword is a cane containing a hidden blade or sword. The term is typically used to describe European weapons from around the 18th century. But similar devices have been used throughout history, notably the Roman ''dolon'', t ...

in hand, and a cigar hanging out of his mouth. He had a tendency to forget where he was supposed to be going and miss the train that was supposed to take him there. It is reported that on several occasions he sent a telegram to his wife Frances from an incorrect location, writing such things as "Am in Market Harborough

Market Harborough is a market town in the Harborough District, Harborough district of Leicestershire, England, close to the border with Northamptonshire. The population was 24,779 at the United Kingdom census, 2021, 2021 census. It is the ad ...

. Where ought I to be?" to which she would reply, "Home". Chesterton himself told this story, omitting, however, his wife's alleged reply, in his autobiography.

In 1931, the BBC

The British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) is a British public service broadcaster headquartered at Broadcasting House in London, England. Originally established in 1922 as the British Broadcasting Company, it evolved into its current sta ...

invited Chesterton to give a series of radio talks. He accepted, tentatively at first. He was allowed (and encouraged) to improvise on the scripts. This allowed his talks to maintain an intimate character, as did the decision to allow his wife and secretary to sit with him during his broadcasts. The talks were very popular. A BBC official remarked, after Chesterton's death, that "in another year or so, he would have become the dominating voice from Broadcasting House." Chesterton was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature

The Nobel Prize in Literature, here meaning ''for'' Literature (), is a Swedish literature prize that is awarded annually, since 1901, to an author from any country who has, in the words of the will of Swedish industrialist Alfred Nobel, "in ...

in 1935.

Chesterton was part of the Detection Club

The Detection Club was formed in 1930 by a group of British mystery writers, including Agatha Christie, Dorothy L. Sayers, Ronald Knox, Freeman Wills Crofts, Arthur Morrison, Hugh Walpole, John Rhode, Jessie Louisa Rickard, Baroness Orczy, ...

, a society of British mystery authors founded by Anthony Berkeley

Anthony Berkeley Cox (5 July 1893 – 9 March 1971) was an English crime writer. He wrote under several pen-names, including Francis Iles, Anthony Berkeley and A. Monmouth Platts.

Early life and education

Anthony Berkeley Cox was born 5 July ...

in 1928. He was elected as the first president and served from 1930 to 1936 until he was succeeded by E. C. Bentley.

Chesterton was one of the dominating figures of the London literary scene in the early 20th century.

Death

Chesterton died of

Chesterton died of congestive heart failure

Heart failure (HF), also known as congestive heart failure (CHF), is a syndrome caused by an impairment in the heart's ability to fill with and pump blood.

Although symptoms vary based on which side of the heart is affected, HF typically pr ...

on 14 June 1936, aged 62, at his home in Beaconsfield

Beaconsfield ( ) is a market town and Civil parishes in England, civil parish in Buckinghamshire, England, northwest of central London and southeast of Aylesbury. Three other towns are within : Gerrards Cross, Amersham and High Wycombe.

The ...

, Buckinghamshire. His last words were a greeting of good morning spoken to his wife Frances. The sermon at Chesterton's Requiem Mass

A Requiem (Latin: ''rest'') or Requiem Mass, also known as Mass for the dead () or Mass of the dead (), is a Mass of the Catholic Church offered for the repose of the souls of the deceased, using a particular form of the Roman Missal. It is u ...

in Westminster Cathedral

Westminster Cathedral, officially the Metropolitan Cathedral of the Most Precious Blood, is the largest Catholic Church in England and Wales, Roman Catholic church in England and Wales. The shrine is dedicated to the Blood of Jesus Ch ...

, London, was delivered by Ronald Knox

Ronald Arbuthnott Knox (17 February 1888 – 24 August 1957) was an English Catholic priest, theologian

Theology is the study of religious belief from a religious perspective, with a focus on the nature of divinity. It is taught as an ...

on 27 June 1936. Knox said, "All of this generation has grown up under Chesterton's influence so completely that we do not even know when we are thinking Chesterton." He is buried in Beaconsfield in the Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

Cemetery. Chesterton's estate was probate

In common law jurisdictions, probate is the judicial process whereby a will is "proved" in a court of law and accepted as a valid public document that is the true last testament of the deceased; or whereby, in the absence of a legal will, the e ...

d at £28,389, .

Near the end of Chesterton's life, Pope Pius XI

Pope Pius XI (; born Ambrogio Damiano Achille Ratti, ; 31 May 1857 – 10 February 1939) was head of the Catholic Church from 6 February 1922 until his death in February 1939. He was also the first sovereign of the Vatican City State u ...

invested him as Knight Commander with Star of the Papal Order of St. Gregory the Great

The Pontifical Equestrian Order of St. Gregory the Great (; ) was established on 1 September 1831, by Pope Gregory XVI, seven months after his election as Pope.

The order is one of the five Papal order of knighthood, orders of knighthood of th ...

(KC*SG). The Chesterton Society has proposed that he be beatified

Beatification (from Latin , "blessed" and , "to make") is a recognition accorded by the Catholic Church of a deceased person's entrance into Heaven and capacity to intercede on behalf of individuals who pray in their name. ''Beati'' is the ...

.

Writing

Chesterton wrote around 80 books, several hundred poems, some 200 short stories, 4,000 essays (mostly newspaper columns), and several plays. He was a literary and social critic, historian, playwright, novelist, and Catholic theologian andapologist

Apologetics (from Greek ) is the religious discipline of defending religious doctrines through systematic argumentation and discourse. Early Christian writers (c. 120–220) who defended their beliefs against critics and recommended their fa ...

, debater, and mystery writer. He was a columnist for the ''Daily News'', ''The Illustrated London News

''The Illustrated London News'', founded by Herbert Ingram and first published on Saturday 14 May 1842, was the world's first illustrated weekly news magazine. The magazine was published weekly for most of its existence, switched to a less freq ...

'', and his own paper, ''G. K.'s Weekly

''G.K.'s Weekly'' was a British publication founded in 1925 (with its pilot edition surfacing in late 1924) by writer G. K. Chesterton, continuing until his death in 1936. Its articles typically discussed topical cultural, political, and socio- ...

''; he also wrote articles for the ''Encyclopædia Britannica

The is a general knowledge, general-knowledge English-language encyclopaedia. It has been published by Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. since 1768, although the company has changed ownership seven times. The 2010 version of the 15th edition, ...

'', including the entry on Charles Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens (; 7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English novelist, journalist, short story writer and Social criticism, social critic. He created some of literature's best-known fictional characters, and is regarded by ...

and part of the entry on Humour in the 14th edition (1929). His best-known character is the priest-detective Father Brown

Father Brown is a fictional Roman Catholic priest and amateur detective. He is featured in 53 short stories by English author G. K. Chesterton, published between 1910 and 1936. Father Brown solves mysteries and crimes using his intuition and ...

, who appeared only in short stories, while ''The Man Who Was Thursday

''The Man Who Was Thursday: A Nightmare'' is a 1908 novel by G. K. Chesterton. The book has been described as a metaphysical thriller.

Plot summary

Chesterton prefixed the novel with a poem written to Edmund Clerihew Bentley, revisiting the ...

'' is arguably his best-known novel. He was a convinced Christian long before he was received into the Catholic Church, and Christian themes and symbolism appear in much of his writing. In the United States, his writings on distributism

Distributism is an economic theory asserting that the world's productive assets should be widely owned rather than concentrated. Developed in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, distributism was based upon Catholic social teaching princi ...

were popularised through '' The American Review'', published by Seward Collins

Seward Bishop Collins (April 22, 1899 – December 8, 1952) was an American New York socialite and publisher. By the end of the 1920s, he was a self-described "fascism, fascist".

Early life and education

Collins was born in Albion, Orleans Co ...

in New York.

Of his nonfiction, ''Charles Dickens: A Critical Study'' (1906) has received some of the broadest-based praise. According to Ian Ker (''The Catholic Revival in English Literature, 1845–1961'', 2003), "In Chesterton's eyes Dickens belongs to Merry

Merry may refer to:

A happy person with a jolly personality.

People

* Merry (given name)

* Merry (surname)

Music

* Merry (band), a Japanese rock band

* ''Merry'' (EP), an EP by Gregory Douglass

* "Merry" (song), by American power pop band Magn ...

, not Puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to rid the Church of England of what they considered to be Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should b ...

, England"; Ker treats Chesterton's thought in chapter 4 of that book as largely growing out of his true appreciation of Dickens, a somewhat shop-soiled property in the view of other literary opinions of the time. The biography was largely responsible for creating a popular revival for Dickens's work as well as a serious reconsideration of Dickens by scholars.

Chesterton's writings consistently displayed wit and a sense of humour. He employed paradox, while making serious comments on the world, government, politics, economics, philosophy, theology and many other topics.

T. S. Eliot

Thomas Stearns Eliot (26 September 18884 January 1965) was a poet, essayist and playwright.Bush, Ronald. "T. S. Eliot's Life and Career", in John A Garraty and Mark C. Carnes (eds), ''American National Biography''. New York: Oxford University ...

summed up his work as follows:

Eliot commented further that "His poetry was first-rate journalistic balladry, and I do not suppose that he took it more seriously than it deserved. He reached a high imaginative level with '' The Napoleon of Notting Hill'', and higher with ''The Man Who Was Thursday

''The Man Who Was Thursday: A Nightmare'' is a 1908 novel by G. K. Chesterton. The book has been described as a metaphysical thriller.

Plot summary

Chesterton prefixed the novel with a poem written to Edmund Clerihew Bentley, revisiting the ...

'', romances in which he turned the Stevensonian fantasy to more serious purpose. His book on Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens (; 7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English novelist, journalist, short story writer and social critic. He created some of literature's best-known fictional characters, and is regarded by many as the great ...

seems to me the best essay on that author that has ever been written. Some of his essays can be read again and again; though of his essay-writing as a whole, one can only say that it is remarkable to have maintained such a high average with so large an output."

In 2022, a three-volume bibliography of Chesterton was published, listing 9,000 contributions he made to newspapers, magazines, and journals, as well as 200 books and 3,000 articles about him.

Contemporaries

"Chesterbelloc"

Chesterton is often associated with his close friend, the poet and essayistHilaire Belloc

Joseph Hilaire Pierre René Belloc ( ; ; 27 July 187016 July 1953) was a French-English writer, politician, and historian. Belloc was also an orator, poet, sailor, satirist, writer of letters, soldier, and political activist. His Catholic fait ...

. George Bernard Shaw coined the name "Chesterbelloc" for their partnership, and this stuck. Though they were very different men, they shared many beliefs; in 1922, Chesterton joined Belloc in the Catholic faith, and both voiced criticisms of capitalism and socialism. They instead espoused a third way: distributism

Distributism is an economic theory asserting that the world's productive assets should be widely owned rather than concentrated. Developed in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, distributism was based upon Catholic social teaching princi ...

. '' G. K.'s Weekly'', which occupied much of Chesterton's energy in the last 15 years of his life, was the successor to Belloc's ''New Witness

''G.K.'s Weekly'' was a British publication founded in 1925 (with its pilot edition surfacing in late 1924) by writer G. K. Chesterton, continuing until his death in 1936. Its articles typically discussed topical cultural, political, and socio- ...

'', taken over from Cecil Chesterton

Cecil Edward Chesterton (12 November 1879 – 6 December 1918) was an English journalist and political commentator, known particularly for his role as editor of '' The New Witness'' from 1912 to 1916, and in relation to its coverage of the Marco ...

, Gilbert's brother, who died in World War I.

In his book ''On the Place of Gilbert Chesterton in English Letters'', Belloc wrote that "Everything he wrote upon any one of the great English literary names was of the first quality. He summed up any one pen (that of Jane Austen

Jane Austen ( ; 16 December 1775 – 18 July 1817) was an English novelist known primarily for #List of works, her six novels, which implicitly interpret, critique, and comment on the English landed gentry at the end of the 18th century ...

, for instance) in exact sentences; sometimes in a single sentence, after a fashion which no one else has approached. He stood quite by himself in this department. He understood the very minds (to take the two most famous names) of Thackeray

William Makepeace Thackeray ( ; 18 July 1811 – 24 December 1863) was an English novelist and illustrator. He is known for his satirical works, particularly his 1847–1848 novel '' Vanity Fair'', a panoramic portrait of British society, and t ...

and of Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens (; 7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English novelist, journalist, short story writer and social critic. He created some of literature's best-known fictional characters, and is regarded by many as the great ...

. He understood and presented Meredith. He understood the supremacy in Milton. He understood Pope

The pope is the bishop of Rome and the Head of the Church#Catholic Church, visible head of the worldwide Catholic Church. He is also known as the supreme pontiff, Roman pontiff, or sovereign pontiff. From the 8th century until 1870, the po ...

. He understood the great Dryden. He was not swamped as nearly all his contemporaries were by Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 23 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's natio ...

, wherein they drown as in a vast sea – for that is what Shakespeare is. Gilbert Chesterton continued to understand the youngest and latest comers as he understood the forefathers in our great corpus of English verse and prose."

Wilde

In his book ''Heretics

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, particularly the accepted beliefs or religious law of a religious organization. A heretic is a proponent of heresy.

Heresy in Christianity, Judai ...

'', Chesterton said this of Oscar Wilde

Oscar Fingal O'Fflahertie Wills Wilde (16 October 185430 November 1900) was an Irish author, poet, and playwright. After writing in different literary styles throughout the 1880s, he became one of the most popular and influential playwright ...

: "The same lesson f the pessimistic pleasure-seeker

F, or f, is the sixth letter of the Latin alphabet and many modern alphabets influenced by it, including the modern English alphabet and the alphabets of all other modern western European languages. Its name in English is ''ef'' (pronounc ...

was taught by the very powerful and very desolate philosophy of Oscar Wilde. It is the carpe diem

() is a Latin aphorism, usually translated "seize the day", taken from book 1 of the Roman poet Horace's work '' Odes'' (23 BC).

Translation

is the second-person singular present active imperative of '' carpō'' "pick or pluck" used by Ho ...

religion; but the carpe diem religion is not the religion of happy people, but of very unhappy people. Great joy does not gather the rosebuds while it may; its eyes are fixed on the immortal rose which Dante saw." More briefly, and with a closer approximation to Wilde's own style, he wrote in his 1908 book ''Orthodoxy

Orthodoxy () is adherence to a purported "correct" or otherwise mainstream- or classically-accepted creed, especially in religion.

Orthodoxy within Christianity refers to acceptance of the doctrines defined by various creeds and ecumenical co ...

'' concerning the necessity of making symbolic sacrifices for the gift of creation: "Oscar Wilde said that sunsets were not valued because we could not pay for sunsets. But Oscar Wilde was wrong; we can pay for sunsets. We can pay for them by not being Oscar Wilde."

Shaw

Chesterton andGeorge Bernard Shaw

George Bernard Shaw (26 July 1856 – 2 November 1950), known at his insistence as Bernard Shaw, was an Irish playwright, critic, polemicist and political activist. His influence on Western theatre, culture and politics extended from the 188 ...

were famous friends and enjoyed their arguments and discussions. Although rarely in agreement, they each maintained good will toward, and respect for, the other. In his writing, Chesterton expressed himself very plainly on where they differed and why. In ''Heretics'' he writes of Shaw:

Views

Advocacy of Catholicism

Chesterton's views, in contrast to Shaw and others, became increasingly focused towards the Church. In ''Orthodoxy'' he wrote: "The worship of will is the negation of will... If Mr Bernard Shaw comes up to me and says, 'Will something', that is tantamount to saying, 'I do not mind what you will', and that is tantamount to saying, 'I have no will in the matter.' You cannot admire will in general, because the essence of will is that it is particular." Chesterton's ''The Everlasting Man

''The Everlasting Man'' is a Christian apologetics book written by G. K. Chesterton, published in 1925. It is, to some extent, a deliberate rebuttal of H. G. Wells' '' The Outline of History'', disputing Wells' portrayals of human life and civ ...

'' contributed to C. S. Lewis

Clive Staples Lewis (29 November 1898 – 22 November 1963) was a British writer, literary scholar and Anglican lay theologian. He held academic positions in English literature at both Magdalen College, Oxford (1925–1954), and Magdalen ...

's conversion to Christianity. In a letter to Sheldon Vanauken

Sheldon Vanauken (; August 4, 1914October 18, 1996) was an American author, best known for his autobiographical book '' A Severe Mercy'' (1977), which recounts his and his wife's friendship with C. S. Lewis, their conversion to Christianity, and ...

(14 December 1950), Lewis called the book "the best popular apologetic I know", and to Rhonda Bodle he wrote (31 December 1947) "the erybest popular defence of the full Christian position I know is G. K. Chesterton's ''The Everlasting Man''". The book was also cited in a list of 10 books that "most shaped his vocational attitude and philosophy of life".

Chesterton's hymn "O God of Earth and Altar" was printed in ''The Commonwealth

''The'' is a grammatical article in English, denoting nouns that are already or about to be mentioned, under discussion, implied or otherwise presumed familiar to listeners, readers, or speakers. It is the definite article in English. ''The ...

'' and then included in ''The English Hymnal

''The English Hymnal'' is a hymn book which was published in 1906 for the Church of England by Oxford University Press. It was edited by the clergyman and writer Percy Dearmer and the composer and music historian Ralph Vaughan Williams, and ...

'' in 1906. Several lines of the hymn appear in the beginning of the song "Revelations" by the British heavy metal band Iron Maiden

Iron Maiden are an English Heavy metal music, heavy metal band formed in Leyton, East London, in 1975 by bassist and primary songwriter Steve Harris (musician), Steve Harris. Although fluid in the early years of the band, the line-up for most ...

on their 1983 album ''Piece of Mind

''Piece of Mind'' is the fourth studio album by English heavy metal band Iron Maiden. It was released on 16 May 1983 in the United Kingdom by EMI Records and in the United States by Capitol Records. It was the first album to feature drummer ...

''. Lead singer Bruce Dickinson

Paul Bruce Dickinson (born 7 August 1958) is an English singer who is best known as the lead vocalist of the heavy metal band Iron Maiden. Dickinson has performed in the band across two stints, from 1981 to 1993 and from 1999 to the present d ...

in an interview stated "I have a fondness for hymns. I love some of the ritual, the beautiful words, ''Jerusalem

Jerusalem is a city in the Southern Levant, on a plateau in the Judaean Mountains between the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean and the Dead Sea. It is one of the List of oldest continuously inhabited cities, oldest cities in the world, and ...

'' and there was another one, with words by G. K. Chesterton ''O God of Earth and Altar'' – very fire and brimstone: 'Bow down and hear our cry'. I used that for an Iron Maiden song, "Revelations". In my strange and clumsy way I was trying to say look it's all the same stuff."

Étienne Gilson

Étienne Henri Gilson (; 13 June 1884 – 19 September 1978) was a French philosopher and historian of philosophy. A scholar of medieval philosophy, he originally specialised in the thought of Descartes; he also philosophized in the tradition ...

praised Chesterton's book on Thomas Aquinas: "I consider it as being, without possible comparison, the best book ever written on Saint Thomas... the few readers who have spent twenty or thirty years in studying St. Thomas Aquinas, and who, perhaps, have themselves published two or three volumes on the subject, cannot fail to perceive that the so-called 'wit' of Chesterton has put their scholarship to shame."

Archbishop Fulton J. Sheen, the author of 70 books, identified Chesterton as the stylist who had the greatest impact on his own writing, stating in his autobiography ''Treasure in Clay'', "the greatest influence in writing was G. K. Chesterton who never used a useless word, who saw the value of a paradox, and avoided what was trite." Chesterton wrote the introduction to Sheen's book ''God and Intelligence in Modern Philosophy; A Critical Study in the Light of the Philosophy of Saint Thomas''.

Common Sense

Chesterton has been called "The Apostle of Common Sense". He was critical of the thinkers and popular philosophers of the day, who though very clever, were saying things that he considered nonsensical. This is illustrated again in ''Orthodoxy'': "Thus when Mr H. G. Wells says (as he did somewhere), 'All chairs are quite different', he utters not merely a misstatement, but a contradiction in terms. If all chairs were quite different, you could not call them 'all chairs'."Conservatism

Although Chesterton was an early member of theFabian Society

The Fabian Society () is a History of the socialist movement in the United Kingdom, British socialist organisation whose purpose is to advance the principles of social democracy and democratic socialism via gradualist and reformist effort in ...

, he resigned at the time of the Second Boer War

The Second Boer War (, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, Transvaal War, Anglo–Boer War, or South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer republics (the South African Republic and ...

. He is often identified as a traditionalist conservative

Traditionalist conservatism, often known as classical conservatism, is a political and social philosophy that emphasizes the importance of transcendent moral principles, manifested through certain posited natural laws to which it is claimed ...

due to his staunch support of tradition, expressed in ''Orthodoxy'' and other works with Burkean

Edmund Burke (; 12 January NS">New_Style.html" ;"title="/nowiki>New Style">NS/nowiki> 1729 – 9 July 1797) was an Anglo-Irish Politician, statesman, journalist, writer, literary critic, philosopher, and parliamentary orator who is regarded ...

quotes such as the following:

Chesterton has been considered among the United Kingdom's conservative anti-imperialist wing, contrasted with his intellectual rivals in Shaw and Wells. Chesterton's association with conservatism has expanded beyond British politics; Japanese conservative intellectuals, such as , have often referred to Chesterton's appeal to tradition as the "democracy of the dead". However, Chesterton did not equate conservatism with complacency, arguing that cultural conservatives had to be politically radical.

Liberalism

In spite of his association with tradition and conservatism, Chesterton called himself "the last liberal". He was a supporter of theLiberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world.

The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left. For example, while the political systems ...

until he severed ties in 1928 following the death of former Liberal Prime Minister H. H. Asquith

Herbert Henry Asquith, 1st Earl of Oxford and Asquith (12 September 1852 – 15 February 1928) was a British statesman and Liberal Party (UK), Liberal politician who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1908 to 1916. He was the last ...

, although his attachment had already gradually weakened over the decades. In addition the ''Daily News'', for which Chesterton had been a columnist between 1903 and 1913, was aligned with the Liberals.

Chesterton's increasing coolness towards the Liberal Party was a response to the rise of New Liberalism in the early 20th century, which differed from his own vision of liberalism in several respects: it was secular, rather than being rooted in Christianity like the party's previously predominant creed of Gladstonian liberalism

Gladstonian liberalism is a political doctrine named after the British Victorian Prime Minister and Liberal Party leader William Ewart Gladstone. Gladstonian liberalism consisted of limited government expenditure and low taxation whilst making ...

, and advocated a collectivist approach to social reform at odds with Chesterton's concern about what he saw as an increasingly interventionist and technocratic

Technocracy is a form of government in which decision-makers appoint knowledge experts in specific domains to provide them with advice and guidance in various areas of their policy-making responsibilities. Technocracy follows largely in the tra ...

state challenging both the primacy of the family in social organisation and democracy as a political ideal.

Despite this critique of the development of left-liberalism in this period, Chesterton also criticised the laissez-faire

''Laissez-faire'' ( , from , ) is a type of economic system in which transactions between private groups of people are free from any form of economic interventionism (such as subsidies or regulations). As a system of thought, ''laissez-faire'' ...

approach of Manchester Liberalism

Manchester Liberalism (also called the Manchester School, Manchester Capitalism and Manchesterism) comprises the political, economic and social movements of the 19th century that originated in Manchester. Led by Richard Cobden and John Bright ...

which had been influential among Liberals in the late 19th century, arguing that this had led to the development of monopolies

A monopoly (from Greek and ) is a market in which one person or company is the only supplier of a particular good or service. A monopoly is characterized by a lack of economic competition to produce a particular thing, a lack of viable sub ...

and plutocracy

A plutocracy () or plutarchy is a society that is ruled or controlled by people of great wealth or income. The first known use of the term in English dates from 1631. Unlike most political systems, plutocracy is not rooted in any established ...

rather than the competition classical theorists had predicted, as well as the exploitation of workers for profit.

In addition to Chesterton, other distributists including Belloc were also involved with the Liberals before the First World War. They shared much common ground in terms of their policy agenda with the broader party during this time, including devolution of power to local government, franchise reform, replication of the Irish Wyndham Land Act in Britain, supporting trade unions and a degree of social reform by central government, whilst opposing socialism.

Chesterton opposed the Conservative Education Act 1902

The Education Act 1902 ( 2 Edw. 7. c. 42), also known as the Balfour Act, was a highly controversial act of Parliament that set the pattern of elementary education in England and Wales for four decades. It was brought to Parliament by a Conserva ...

, which provided for public funding of Church schools, on the grounds that religious freedom was best served by keeping religion out of education. However, he disassociated himself from the campaign against it led by John Clifford, whose invoking of the Act's provisions as resulting in "Rome on the rates

Rate or rates may refer to:

Finance

* Rate (company), an American residential mortgage company formerly known as Guaranteed Rate

* Rates (tax), a type of taxation system in the United Kingdom used to fund local government

* Exchange rate, rate ...

" was judged by Chesterton to be bigotry appealing to straw man

A straw man fallacy (sometimes written as strawman) is the informal fallacy of refuting an argument different from the one actually under discussion, while not recognizing or acknowledging the distinction. One who engages in this fallacy is said ...

arguments. The Chestertons and Belloc supported the Liberal leadership on the passage of David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. A Liberal Party (United Kingdom), Liberal Party politician from Wales, he was known for leadi ...

's People's Budget

The 1909/1910 People's Budget was a proposal of the Liberal government that introduced unprecedented taxes on the lands and incomes of Britain's wealthy to fund new social welfare programmes, such as non-contributary old age pensions under Ol ...

and the weakening of the power of the House of Lords through the Parliament Act 1911

The Parliament Act 1911 ( 1 & 2 Geo. 5. c. 13) is an act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It is constitutionally important and partly governs the relationship between the House of Commons and the House of Lords, the two Houses of Parl ...

in response to its resistance to the budget, but were critical of their timidity in pushing for Irish Home Rule

The Home Rule movement was a movement that campaigned for self-government (or "home rule") for Ireland within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It was the dominant political movement of Irish nationalism from 1870 to the end of ...

.

Following the War the position of the New Liberals had strengthened, and the distributists came to believe that the party's positions were closer to social democracy

Social democracy is a Social philosophy, social, Economic ideology, economic, and political philosophy within socialism that supports Democracy, political and economic democracy and a gradualist, reformist, and democratic approach toward achi ...

than liberalism. They also differed from most Liberals by advocating for home rule for all of Ireland, rather than partition. More generally they developed a policy agenda distinct from any of the main three parties during this time, including promoting guild

A guild ( ) is an association of artisans and merchants who oversee the practice of their craft/trade in a particular territory. The earliest types of guild formed as organizations of tradespeople belonging to a professional association. They so ...

s and the nuclear family, introducing primary election

Primary elections or primaries are elections held to determine which candidates will run in an upcoming general election. In a partisan primary, a political party selects a candidate. Depending on the state and/or party, there may be an "open pr ...

s and referendum

A referendum, plebiscite, or ballot measure is a Direct democracy, direct vote by the Constituency, electorate (rather than their Representative democracy, representatives) on a proposal, law, or political issue. A referendum may be either bin ...

s, antitrust

Competition law is the field of law that promotes or seeks to maintain market competition by regulating anti-competitive conduct by companies. Competition law is implemented through public and private enforcement. It is also known as antitrust l ...

action, tax reform to favour small businesses, and transparency regarding party funding and the Honours Lists.

On War

Chesterton first emerged as a journalist just after the turn of the 20th century. His great, and very lonely, opposition to theSecond Boer War

The Second Boer War (, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, Transvaal War, Anglo–Boer War, or South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer republics (the South African Republic and ...

, set him very much apart from most of the rest of the British press. Chesterton was a Little Englander

The Little Englanders were a British political movement who opposed empire-building and advocated complete independence for Britain's existing colonies. The ideas of Little Englandism first began to gain popularity in the late 18th century after ...

, opposed to imperialism

Imperialism is the maintaining and extending of Power (international relations), power over foreign nations, particularly through expansionism, employing both hard power (military and economic power) and soft power (diplomatic power and cultura ...

, British or otherwise. Chesterton thought that Great Britain betrayed her own principles in the Boer Wars.

In vivid contrast to his opposition to the Boer Wars, Chesterton vigorously defended and encouraged the Allies in World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

. "The war was in Chesterton's eyes a crusade, and he was certain that England was right to fight as she had been wrong in fighting the Boers." Chesterton saw the roots of the war in Prussian militarism. He was deeply disturbed by Prussia's unprovoked invasion and occupation of neutral Belgium and by reports of shocking atrocities the Imperial German Army

The Imperial German Army (1871–1919), officially referred to as the German Army (), was the unified ground and air force of the German Empire. It was established in 1871 with the political unification of Germany under the leadership of Kingdom o ...

was allegedly committing in Belgium. Over the course of the War, Chesterton wrote hundreds of essays defending it, attacking pacifism, and exhorting the public to persevere until victory. Some of these essays were collected in the 1916 work, ''The Barbarism of Berlin''.

One of Chesterton's most successful works in support of the War was his 1915 tongue-in-cheek ''The Crimes of England''. The work is ironic, supposedly apologizing and trying to help a fictitious Prussian professor named Whirlwind make the case for Prussia in WWI, while actually attacking Prussia throughout. Part of the book's humorous impact is the conceit that Professor Whirlwind never realizes how his supposed benefactor is undermining Prussia at every turn. Chesterton "blames" England for historically building up Prussia against Austria, and for its pacifism, especially among wealthy British Quaker political donors, who prevented Britain from standing up to past Prussian aggression.

Accusations of antisemitism

Chesterton faced accusations of

Chesterton faced accusations of antisemitism

Antisemitism or Jew-hatred is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who harbours it is called an antisemite. Whether antisemitism is considered a form of racism depends on the school of thought. Antisemi ...

during his lifetime, saying in his 1920 book '' The New Jerusalem'' that it was something "for which my friends and I were for a long period rebuked and even reviled". Despite his protestations to the contrary, the accusation continues to be repeated. An early supporter of Captain Dreyfus, by 1906 he had turned into an anti-Dreyfusard. From the early 20th century, his fictional work included caricatures of Jews, stereotyping them as greedy, cowardly, disloyal and communists. Martin Gardner

Martin Gardner (October 21, 1914May 22, 2010) was an American popular mathematics and popular science writer with interests also encompassing magic, scientific skepticism, micromagic, philosophy, religion, and literatureespecially the writin ...

suggests that ''Four Faultless Felons'' was allowed to go out of print in the United States because of the "anti-Semitism which mars so many pages."

The Marconi scandal

The Marconi scandal was a British political scandal that broke in mid-1912. Allegations were made that highly placed members of the Liberal government under the Prime Minister H. H. Asquith had profited by improper use of information about the g ...

of 1912–1913 brought issues of anti-Semitism into the political mainstream. Senior ministers in the Liberal government had secretly profited from advance knowledge of deals regarding wireless telegraphy, and critics regarded it as relevant that some of the key players were Jewish. According to historian Todd Endelman, who identified Chesterton as among the most vocal critics, "The Jew-baiting at the time of the Boer War and the Marconi scandal was linked to a broader protest, mounted in the main by the Radical wing of the Liberal Party, against the growing visibility of successful businessmen in national life and their challenge to what were seen as traditional English values."

In a work of 1917, titled ''A Short History of England'', Chesterton considers the royal decree of 1290 by which Edward I expelled Jews from England, a policy that remained in place until 1655. Chesterton writes that popular perception of Jewish moneylenders could well have led Edward I's subjects to regard him as a "tender father of his people" for "breaking the rule by which the rulers had hitherto fostered their bankers' wealth". He felt that Jews, "a sensitive and highly civilized people" who "were the capitalists of the age, the men with wealth banked ready for use", might legitimately complain that "Christian kings and nobles, and even Christian popes and bishops, used for Christian purposes (such as the Crusades and the cathedrals) the money that could only be accumulated in such mountains by a usury they inconsistently denounced as unchristian; and then, when worse times came, gave up the Jew to the fury of the poor".

In ''The New Jerusalem,'' Chesterton dedicated a chapter to his views on the Jewish question

The Jewish question was a wide-ranging debate in 19th- and 20th-century Europe that pertained to the appropriate status and treatment of Jews. The debate, which was similar to other " national questions", dealt with the civil, legal, national, ...

: the sense that Jews were a distinct people without a homeland of their own, living as foreigners in countries where they were always a minority. He wrote that in the past, his position:

In the same place he proposed the thought experiment (describing it as "a parable" and "a flippant fancy") that Jews should be admitted to any role in English public life on condition that they must wear distinctively Middle Eastern garb, explaining that "The point is that we should know where we are; and he would know where he is, which is in a foreign land."

Chesterton, like Belloc, openly expressed his abhorrence of Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

's rule almost as soon as it started. As Rabbi Stephen Samuel Wise

Stephen Samuel Wise (March 17, 1874 – April 19, 1949) was an early 20th-century American Reform rabbi and Zionist leader in the Progressive Era. Born in Budapest, he was an infant when his family immigrated to New York. He followed his father ...

wrote in a posthumous tribute to Chesterton in 1937:

In ''The Truth About the Tribes,'' Chesterton attacked Nazi racial theories

The German Nazi Party adopted and developed several Racial hierarchy, racial hierarchical categorizations as an important part of its racist ideology (Nazism) in order to justify enslavement, genocide, extermination, racism, ethnic persecut ...

, writing: "the essence of Nazi Nationalism is to preserve the purity of a race in a continent where all races are impure".

The historian Simon Mayers points out that Chesterton wrote in works such as ''The Crank'', ''The Heresy of Race'', and ''The Barbarian as Bore'' against the concept of racial superiority and critiqued pseudo-scientific race theories, saying they were akin to a new religion. In ''The Truth About the Tribes'' Chesterton wrote, "the curse of race religion is that it makes each separate man the sacred image which he worships. His own bones are the sacred relics; his own blood is the blood of St. Januarius". Mayers records that despite "his hostility towards Nazi antisemitism … t is unfortunate that he madeclaims that 'Hitlerism' was a form of Judaism, and that the Jews were partly responsible for race theory". In ''The Judaism of Hitler'', as well as in ''A Queer Choice'' and ''The Crank'', Chesterton made much of the fact that the very notion of "a Chosen Race" was of Jewish origin, saying in ''The Crank'': "If there is one outstanding quality in Hitlerism it is its Hebraism" and "the new Nordic Man has all the worst faults of the worst Jews: jealousy, greed, the mania of conspiracy, and above all, the belief in a Chosen Race".

Mayers also shows that Chesterton portrayed Jews not only as culturally and religiously distinct, but racially as well. In ''The Feud of the Foreigner'' (1920) he said that the Jew "is a foreigner far more remote from us than is a Bavarian from a Frenchman; he is divided by the same type of division as that between us and a Chinaman or a Hindoo. He not only is not, but never was, of the same race".

In ''The Everlasting Man'', while writing about human sacrifice

Human sacrifice is the act of killing one or more humans as part of a ritual, which is usually intended to please or appease deity, gods, a human ruler, public or jurisdictional demands for justice by capital punishment, an authoritative/prie ...

, Chesterton suggested that medieval stories about Jews killing children might have resulted from a distortion of genuine cases of devil worship. Chesterton wrote:

The American Chesterton Society has devoted a whole issue of its magazine, ''Gilbert'', to defending Chesterton against charges of antisemitism. Likewise, Ann Farmer, author of ''Chesterton and the Jews: Friend, Critic, Defender'', writes, "Public figures from Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

to Wells proposed remedies for the 'Jewish problem

The Jewish question was a wide-ranging debate in 19th- and 20th-century Europe that pertained to the appropriate status and treatment of Jews. The debate, which was similar to other " national questions", dealt with the civil, legal, national, ...

' – the seemingly endless cycle of anti-Jewish persecution – all shaped by their worldviews. As patriots, Churchill and Chesterton embraced Zionism; both were among the first to defend the Jews from Nazism", concluding that "A defender of Jews in his youth – a conciliator as well as a defender – GKC returned to the defence when the Jewish people needed it most."

Opposition to eugenics

In ''Eugenics and Other Evils'', Chesterton attackedeugenics

Eugenics is a set of largely discredited beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetic quality of a human population. Historically, eugenicists have attempted to alter the frequency of various human phenotypes by inhibiting the fer ...

as Parliament was moving towards passage of the Mental Deficiency Act 1913. Some backing the ideas of eugenics called for the government to sterilise people deemed "mentally defective"; this view did not gain popularity but the idea of segregating them from the rest of society and thereby preventing them from reproducing did gain traction. These ideas disgusted Chesterton who wrote, "It is not only openly said, it is eagerly urged that the aim of the measure is to prevent any person whom these propagandists do not happen to think intelligent from having any wife or children." He condemned the proposed wording for such measures as being so vague as to apply to anyone, including "Every tramp who is sulk, every labourer who is shy, every rustic who is eccentric, can quite easily be brought under such conditions as were designed for homicidal maniacs. That is the situation; and that is the point... we are already under the Eugenist State; and nothing remains to us but rebellion." He derided such ideas as founded on nonsense, "as if one had a right to dragoon and enslave one's fellow citizens as a kind of chemical experiment". Chesterton mocked the idea that poverty was a result of bad breeding: " t is astrange new disposition to regard the poor as a race; as if they were a colony of Japs or Chinese coolies... The poor are not a race or even a type. It is senseless to talk about breeding them; for they are not a breed. They are, in cold fact, what Dickens describes: 'a dustbin of individual accidents,' of damaged dignity, and often of damaged gentility."

Chesterton's fence

"Chesterton's fence" is the principle that reforms should not be made until the reasoning behind the existing state of affairs is understood. The quotation is from Chesterton's 1929 book, ''The Thing: Why I Am a Catholic'', in the chapter, "The Drift from Domesticity":Distributism

Rerum novarum

''Rerum novarum'', or ''Rights and Duties of Capital and Labor'', is an encyclical issued by Pope Leo XIII on 15 May 1891. It is an open letter, passed to all Catholic patriarchs, primates, archbishops, and bishops, which addressed the condi ...

'', Chesterton's brother Cecil

Cecil may refer to:

People with the name

* Cecil (given name), a given name (including a list of people and fictional characters with the name)

* Cecil (surname), a surname (including a list of people with the name)

Places Canada

* Cecil, Alberta ...

and his friend, Hilaire Belloc

Joseph Hilaire Pierre René Belloc ( ; ; 27 July 187016 July 1953) was a French-English writer, politician, and historian. Belloc was also an orator, poet, sailor, satirist, writer of letters, soldier, and political activist. His Catholic fait ...

were instrumental in developing the economic philosophy of distributism

Distributism is an economic theory asserting that the world's productive assets should be widely owned rather than concentrated. Developed in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, distributism was based upon Catholic social teaching princi ...

, a word Belloc coined. Gilbert embraced their views and, particularly after Cecil's death in World War I, became one of the foremost distributists and the newspaper whose care he inherited from Cecil, which ultimately came to be named '' G. K.'s Weekly'', became its most consistent advocate. Distributism stands as a third way, against both unrestrained capitalism, and socialism, advocating a wide distribution of both property and political power.

Scottish and Irish nationalism

Despite his opposition to Nazism, Chesterton was not an opponent of nationalism in general and gave a degree of support toScottish

Scottish usually refers to something of, from, or related to Scotland, including:

*Scottish Gaelic, a Celtic Goidelic language of the Indo-European language family native to Scotland

*Scottish English

*Scottish national identity, the Scottish ide ...

and Irish nationalism

Irish nationalism is a nationalist political movement which, in its broadest sense, asserts that the people of Ireland should govern Ireland as a sovereign state. Since the mid-19th century, Irish nationalism has largely taken the form of cult ...

. He endorsed Cunninghame Graham

Robert Bontine Cunninghame Graham (24 May 1852 – 20 March 1936) was a Scottish politician, writer, journalist and adventurer. He was a Liberal Party (UK), Liberal Party Member of Parliament (MP); the first ever socialist member of the Parliam ...

and Compton Mackenzie

Sir Edward Montague Compton Mackenzie, (17 January 1883 – 30 November 1972) was a Scottish writer of fiction, biography, histories and a memoir, as well as a cultural commentator, raconteur and lifelong Scottish nationalist. He was one of t ...

for the post of Lord Rector of Glasgow University

Lord is an appellation for a person or deity who has authority, control, or power over others, acting as a master, chief, or ruler. The appellation can also denote certain persons who hold a title of the peerage in the United Kingdom, or are e ...

in 1928 and 1931 respectively and praised Scottish Catholics as "patriots" in contrast to Anglophile Protestants such as John Knox

John Knox ( – 24 November 1572) was a Scottish minister, Reformed theologian, and writer who was a leader of the country's Reformation. He was the founder of the Church of Scotland.

Born in Giffordgate, a street in Haddington, East Lot ...

. Chesterton was also a supporter of the Irish Home Rule movement

The Home Rule movement was a movement that campaigned for Devolution, self-government (or "home rule") for Ireland within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It was the dominant political movement of Irish nationalism from 1870 to ...

and maintained friendships with members of the Irish Parliamentary Party

The Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP; commonly called the Irish Party or the Home Rule Party) was formed in 1874 by Isaac Butt, the leader of the Nationalist Party, replacing the Home Rule League, as official parliamentary party for Irish nati ...

. This was in part due to his belief that Irish Catholics

Irish Catholics () are an ethnoreligious group native to Ireland, defined by their adherence to Catholic Christianity and their shared Irish ethnic, linguistic, and cultural heritage.The term distinguishes Catholics of Irish descent, particul ...

had a naturally distributist outlook on property ownership.

Legacy

James Parker, in ''The Atlantic

''The Atlantic'' is an American magazine and multi-platform publisher based in Washington, D.C. It features articles on politics, foreign affairs, business and the economy, culture and the arts, technology, and science.

It was founded in 185 ...

'', gave a modern appraisal:

Possible sainthood

The Bishop Emeritus of Northampton, Peter Doyle, in 2012 had opened a preliminary investigation into possibly launching a cause forbeatification

Beatification (from Latin , "blessed" and , "to make") is a recognition accorded by the Catholic Church of a deceased person's entrance into Heaven and capacity to intercede on behalf of individuals who pray in their name. ''Beati'' is the p ...

and then canonization