Fu-Go balloon bomb on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

was an deployed by Japan against the United States during

World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. It consisted of a hydrogen

Hydrogen is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol H and atomic number 1. It is the lightest and abundance of the chemical elements, most abundant chemical element in the universe, constituting about 75% of all baryon, normal matter ...

-filled paper balloon in diameter, with a payload of four incendiary devices and one high-explosive anti-personnel bomb. The uncontrolled balloons were carried over the Pacific Ocean from Japan to North America by fast, high-altitude air currents, today known as the jet stream

Jet streams are fast flowing, narrow thermal wind, air currents in the Earth's Atmosphere of Earth, atmosphere.

The main jet streams are located near the altitude of the tropopause and are westerly winds, flowing west to east around the gl ...

, and used a sophisticated sandbag ballast

Ballast is dense material used as a weight to provide stability to a vehicle or structure. Ballast, other than cargo, may be placed in a vehicle, often a ship or the gondola of a balloon or airship, to provide stability. A compartment within ...

system to maintain their altitude. The bombs were intended to ignite large-scale forest fires and spread panic.

Between November 1944 and April 1945, the Imperial Japanese Army

The Imperial Japanese Army (IJA; , ''Dai-Nippon Teikoku Rikugun'', "Army of the Greater Japanese Empire") was the principal ground force of the Empire of Japan from 1871 to 1945. It played a central role in Japan’s rapid modernization during th ...

launched about 9,300 balloons from sites on coastal Honshu

, historically known as , is the largest of the four main islands of Japan. It lies between the Pacific Ocean (east) and the Sea of Japan (west). It is the list of islands by area, seventh-largest island in the world, and the list of islands by ...

, of which about 300 were found or observed in the U.S., Canada, and Mexico. The bombs were ineffective as fire starters due to damp seasonal conditions, with no forest fires being attributed to the offensive. A U.S. media censorship campaign prevented the Imperial Army from learning of the offensive's results. On May 5, 1945, six civilians were killed by one of the bombs near Bly, Oregon, becoming the war's only fatalities in the contiguous U.S. The Fu-Go balloon bomb was the first weapon system with intercontinental range, predating the intercontinental ballistic missile

An intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) is a ballistic missile with a range (aeronautics), range greater than , primarily designed for nuclear weapons delivery (delivering one or more Thermonuclear weapon, thermonuclear warheads). Conven ...

.

Background

The balloon bomb concept was developed by theImperial Japanese Army

The Imperial Japanese Army (IJA; , ''Dai-Nippon Teikoku Rikugun'', "Army of the Greater Japanese Empire") was the principal ground force of the Empire of Japan from 1871 to 1945. It played a central role in Japan’s rapid modernization during th ...

's Ninth Technical Research Institute (also known as the Noborito Research Institute), tasked with creating special weapons. In 1933, Lieutenant General Reikichi Tada started a balloon bomb program at Noborito designated Fu-Go, which proposed a hydrogen

Hydrogen is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol H and atomic number 1. It is the lightest and abundance of the chemical elements, most abundant chemical element in the universe, constituting about 75% of all baryon, normal matter ...

-filled balloon in diameter with a time fuse, capable of delivering bombs up to . The project was not completed and stopped by 1935.

After the Doolittle Raid in April 1942, in which American planes bombed the Japanese mainland, the Imperial General Headquarters

The was part of the Supreme War Council (Japan), Supreme War Council and was established in 1893 to coordinate efforts between the Imperial Japanese Army and Imperial Japanese Navy during wartime. In terms of function, it was approximately equi ...

directed Noborito to develop a retaliatory bombing capability against the U.S. In mid-1942, Noborito investigated several proposals, including long-range bombers that could make one-way sorties from Japan to cities on the U.S. West Coast, and small bomb-laden seaplane

A seaplane is a powered fixed-wing aircraft capable of takeoff, taking off and water landing, landing (alighting) on water.Gunston, "The Cambridge Aerospace Dictionary", 2009. Seaplanes are usually divided into two categories based on their tech ...

s which could be launched from submarines. On September 9, 1942, the latter was tested in the Lookout Air Raid, in which a Yokosuka E14Y seaplane was launched from a submarine off the Oregon coast. Warrant Officer Nobuo Fujita dropped two large incendiary bomb

Incendiary weapons, incendiary devices, incendiary munitions, or incendiary bombs are weapons designed to start fires. They may destroy structures or sensitive equipment using fire, and sometimes operate as anti-personnel weaponry. Incendiarie ...

s in Siskiyou National Forest Siskiyou may refer to:

*Siskiyou Mountains

The Siskiyou Mountains are a Coast Ranges, coastal subrange of the Klamath Mountains, and located in northwestern California and southwestern Oregon in the United States. They extend in an arc for appro ...

in the hopes of starting a forest fire and safely returned to the submarine. Response crews spotted the plane and contained the small blazes. The program was cancelled by the Imperial Navy.

Also in September 1942, Major General Sueki Kusaba, who had served under Tada in the original balloon bomb program in the 1930s, was assigned to the laboratory and revived the Fu-Go project with a focus on longer flights. The Oregon air raid, while not achieving its strategic objective, had demonstrated the potential of using unmanned balloons at a low cost to ignite large-scale forest fires. According to U.S. interviews with Japanese officials after the war, the balloon bomb campaign was undertaken "almost exclusively for home propaganda purposes", and the Army had little expectation of its effectiveness.

Design and development

By March 1943, Kusaba's team developed a design capable of floating at for up to 30 hours. The balloons were constructed from four to five thin layers of ''washi

is traditional Japanese paper processed by hand using fibers from the inner bark of the gampi tree, the mitsumata shrub (''Edgeworthia chrysantha''), or the paper mulberry (''kōzo'') bush.

''Washi'' is generally tougher than ordinary ...

'', a durable paper derived from the paper mulberry

The paper mulberry (''Broussonetia papyrifera'', syn. ''Morus papyrifera'' L.) is a species of flowering plant in the family Moraceae. It is native to Asia,konnyaku'' (Japanese potato) paste. The Army mobilized thousands of teenage girls at high schools across the country to laminate and glue the sheets together, with final assembly and inflation tests at large indoor arenas including the Nichigeki Music Hall and

File:342-FH-3B23426 (18160066205).jpg, Fu-Go carriage, with labeled ring, electrical circuits, fuses, ballast, and bombs

File:342-FH-3B23434 (18160038915).jpg, Top view of carriage assembly, with control device removed

File:342-FH-3B23427 (17537483644).jpg, Altitude control device, with central master aneroid barometer and backups

File:342-FH-3B23433 (17537463564).jpg, Bottom view of carriage fuses

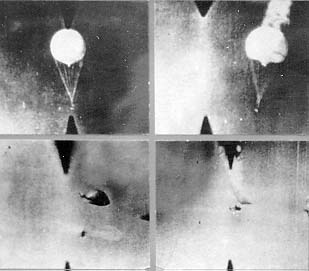

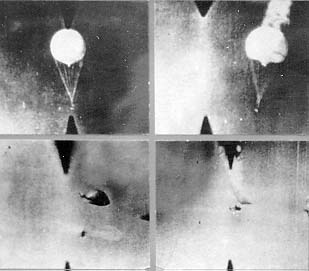

File:342-FH-3B23428 (18160060525).jpg, Recovered Fu-Go at the moment a blowout plug is detonated

Changing pressure levels in a fixed-volume balloon posed technical challenges. During the day, heat from the sun increased pressure, risking the balloon rising above the air currents or bursting. A relief valve was added to allow gas to escape when the envelope's internal pressure rose above a set level. At night, cool temperatures risked the balloon falling below the currents, an issue that worsened as gas was released. To resolve this, engineers developed a sophisticated

A balloon launch organization of three battalions was formed. The first battalion included headquarters and three squadrons, totaling 1,500 men, at nine launch stations at Otsu in

A balloon launch organization of three battalions was formed. The first battalion included headquarters and three squadrons, totaling 1,500 men, at nine launch stations at Otsu in

File:342-FH-3B23422 (18161219731).jpg, Balloon found near

Most U.S. defense plans were only fully implemented after the offensive ended in April 1945. In response to the threat of wildfires in the

Report on Fu-Go balloons by the U.S. Technical Air Intelligence Center, May 1945

* {{Authority control American Theater of World War II Balloon weaponry Balloons (aeronautics) Incendiary weapons Japanese inventions Weapons and ammunition introduced in 1944 World War II weapons of Japan

Ryōgoku Kokugikan

, also known as Ryōgoku Sumo Hall or Kokugikan Arena, is the name bestowed to two different indoor sporting arenas located in Tokyo. The first ''Ryōgoku Kokugikan'' opened its doors in 1909 and was located on the premises of the Ekōin temple i ...

sumo hall in Tokyo. The original proposal called for night launches from submarines located off of the U.S. coast, a distance the balloons could cover in 10 hours. A calibrated timer would release an incendiary bomb at the end of the flight. Two submarines ( ''I-34'' and ''I-35'') were prepared and two hundred balloons were produced by August 1943, but attack missions were postponed due to the need for submarines as weapons and food transports.

Engineers next investigated the feasibility of balloon launches against the United States from the Japanese mainland, a distance of at least . Engineers sought to make use of strong seasonal air currents discovered flowing from west to east at high altitude and speed over Japan, today known as the jet stream

Jet streams are fast flowing, narrow thermal wind, air currents in the Earth's Atmosphere of Earth, atmosphere.

The main jet streams are located near the altitude of the tropopause and are westerly winds, flowing west to east around the gl ...

. The currents had been investigated by Japanese scientist Wasaburo Oishi

was a Japanese meteorologist. Born in Tosu, Saga, he is best known for his discovery of the high-altitude air currents now known as the jet stream. He was also an important Esperantist, serving as the second board president of the Japanese Espe ...

in the 1920s. In late 1943, the Army consulted Hidetoshi Arakawa of the Central Meteorological Observatory, who used Oishi's data to extrapolate the air currents across the Pacific Ocean and estimate that a balloon released in winter and that maintained an altitude of could reach the North American continent in 30 to 100 hours. Arakawa further found that the strongest winds blew from November to March at speeds approaching .

ballast

Ballast is dense material used as a weight to provide stability to a vehicle or structure. Ballast, other than cargo, may be placed in a vehicle, often a ship or the gondola of a balloon or airship, to provide stability. A compartment within ...

system with 32 sandbags mounted around a cast aluminum wheel, with each sandbag connected to gunpowder

Gunpowder, also commonly known as black powder to distinguish it from modern smokeless powder, is the earliest known chemical explosive. It consists of a mixture of sulfur, charcoal (which is mostly carbon), and potassium nitrate, potassium ni ...

blowout plugs. The plugs were connected to three redundant aneroid barometers calibrated for an altitude between , below which one sandbag was released; the next plug was armed two minutes after the previous plug was blown. A separate altimeter set between controlled the later release of the bombs. A one-hour activating fuse for the altimeters was ignited at launch, allowing the balloon time to ascend above these two thresholds. Tests of the design in August 1944 indicated success, with several balloons releasing radiosonde

A radiosonde is a battery-powered telemetry instrument carried into the atmosphere usually by a weather balloon that measures various atmospheric parameters and transmits them by radio to a ground receiver. Modern radiosondes measure or calculat ...

signals for up to 80 hours (the maximum time allowed by the batteries). A self-destruct system was added; a three-minute fuse triggered by the release of the last bomb would detonate a block of picric acid

Picric acid is an organic compound with the formula (O2N)3C6H2OH. Its IUPAC name is 2,4,6-trinitrophenol (TNP). The name "picric" comes from (''pikros''), meaning "bitter", due to its bitter taste. It is one of the most acidic phenols. Like ot ...

and destroy the carriage, followed by an 82-minute fuse that would ignite the hydrogen and destroy the envelope.

In late 1942, the Imperial General Headquarters had directed the Navy to begin its own balloon bomb program in parallel with the Army project. Lieutenant Commander Kiyoshi Tanaka headed a group which developed a rubberized silk balloon, designated the B-Type (in contrast to the Army's A-Type). The silk material was an effort to create a flexible envelope that could withstand pressure changes. The design was tested in August 1944, but the balloons burst immediately after reaching altitude, determined to be the result of faulty rubberized seams. The Navy program was subsequently consolidated under Army control, due in part to the declining availability of rubber as the war continued. The B-Type balloons were later equipped with a version of the A-Type's ballast system and tested on November 2, 1944; one of these balloons, which was not loaded with bombs, became the first to be recovered by Americans after being spotted in the water off San Pedro, California

San Pedro ( ; ) is a neighborhood located within the South Bay (Los Angeles County), South Bay and Los Angeles Harbor Region, Harbor region of the city of Los Angeles, California, United States. Formerly a separate city, it consolidated with Los ...

, on November 4.

The final A-Type design was in diameter, and had a gas volume of and a lifting capacity of at operating altitude. The bomb payload most commonly carried was:

* four thermite

Thermite () is a pyrotechnic composition of powder metallurgy, metal powder and metal oxide. When ignited by heat or chemical reaction, thermite undergoes an exothermic redox, reduction-oxidation (redox) reaction. Most varieties are not explos ...

incendiary device

Incendiary weapons, incendiary devices, incendiary munitions, or incendiary bombs are weapons designed to start fires. They may destroy structures or sensitive equipment using fire, and sometimes operate as anti-personnel weapon, anti-personnel ...

s, consisting of a steel tube long and in diameter with a mechanical impact fuse;

* one Type 92 high-explosive anti-personnel bomb, containing a block of picric acid

Picric acid is an organic compound with the formula (O2N)3C6H2OH. Its IUPAC name is 2,4,6-trinitrophenol (TNP). The name "picric" comes from (''pikros''), meaning "bitter", due to its bitter taste. It is one of the most acidic phenols. Like ot ...

or TNT

Troponin T (shortened TnT or TropT) is a part of the troponin complex, which are proteins integral to the contraction of skeletal and heart muscles. They are expressed in skeletal and cardiac myocytes. Troponin T binds to tropomyosin and helps ...

surrounded by shrapnel rings;

* or alternatively to the anti-personnel bomb, one Type 97 incendiary bomb, containing three magnesium

Magnesium is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol Mg and atomic number 12. It is a shiny gray metal having a low density, low melting point and high chemical reactivity. Like the other alkaline earth metals (group 2 ...

containers of thermite.

Offensive and defenses

A balloon launch organization of three battalions was formed. The first battalion included headquarters and three squadrons, totaling 1,500 men, at nine launch stations at Otsu in

A balloon launch organization of three battalions was formed. The first battalion included headquarters and three squadrons, totaling 1,500 men, at nine launch stations at Otsu in Ibaraki Prefecture

is a Prefectures of Japan, prefecture of Japan located in the Kantō region of Honshu. Ibaraki Prefecture has a population of 2,828,086 (1 July 2023) and has a geographic area of . Ibaraki Prefecture borders Fukushima Prefecture to the north, ...

. The second battalion of 700 men in three squadrons operated six launch stations at Ichinomiya, Chiba, and the third battalion of 600 men in two squadrons operated six launch stations at Nakoso, Fukushima. The Otsu site featured its own hydrogen plant, while the second and third battalions used hydrogen gas transported from factories around Tokyo. The combined launching capacity of the sites was about 200 balloons per day, with 15,000 launches planned through March. The Army estimated that only 10 percent of the balloons would survive the journey across the Pacific Ocean.

Each launch pad consisted of anchor screws drilled into the ground in a circle the same diameter as the balloons. After anchoring an envelope, hoses were used to fill it with of hydrogen while it was tied down with guide ropes and detached from the anchors. The carriage was attached with shroud lines, and the guide ropes were untied. Each launch required a crew of 30 men and took between 30 minutes and one hour, depending on the presence of surface winds. The best time for launches was after a high-pressure front had passed, and wind conditions were best before the onshore breezes at sunrise. Suitable wind conditions were only expected for three to five days a week, for a total of about fifty days during the winter period of maximum jet stream velocity.

The first balloons were launched on November 3, 1944. Some balloons in each of the launches carried radiosonde equipment instead of bombs, and were tracked by direction finding

Direction finding (DF), radio direction finding (RDF), or radiogoniometry is the use of radio waves to determine the direction to a radio source. The source may be a cooperating radio transmitter or may be an inadvertent source, a naturall ...

stations to follow their progress. Two weeks after the discovery of the B-Type balloon off San Pedro, an A-Type balloon was found in the ocean off Kailua, Hawaii

Kailua () is a census-designated place (CDP) in Honolulu County, Hawaii, United States. It lies in the North Koolaupoko, Hawaii, Koolaupoko District of the island of Oahu, Oahu on the windward and leeward, windward coast at Kailua Bay. It is i ...

, on November 14. More were found near Thermopolis, Wyoming, on December 6 (with an explosion heard by witnesses, and a crater later located) and near Kalispell, Montana

Kalispell (, Salish-Spokane-Kalispel language, Montana Salish: Ql̓ispé, Kutenai language: Kqayaqawakⱡuʔnam) is a city in Montana and the county seat of Flathead County, Montana, United States. The 2020 census put Kalispell's population at ...

, on December 11, followed by finds near Marshall

Marshall may refer to:

Places

Australia

*Marshall, Victoria, a suburb of Geelong, Victoria

** Marshall railway station

Canada

* Marshall, Saskatchewan

* The Marshall, a mountain in British Columbia

Liberia

* Marshall, Liberia

Marshall Is ...

and Holy Cross, Alaska, and Estacada, Oregon, later in the month. Authorities were placed on heightened alert, and forest rangers were ordered to report landings and recoveries. The balloons continued to be discovered across North America, with sightings and partial or full recoveries in Alaska

Alaska ( ) is a non-contiguous U.S. state on the northwest extremity of North America. Part of the Western United States region, it is one of the two non-contiguous U.S. states, alongside Hawaii. Alaska is also considered to be the north ...

, Arizona

Arizona is a U.S. state, state in the Southwestern United States, Southwestern region of the United States, sharing the Four Corners region of the western United States with Colorado, New Mexico, and Utah. It also borders Nevada to the nort ...

, California

California () is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States that lies on the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. It borders Oregon to the north, Nevada and Arizona to the east, and shares Mexico–United States border, an ...

, Colorado

Colorado is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States. It is one of the Mountain states, sharing the Four Corners region with Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah. It is also bordered by Wyoming to the north, Nebraska to the northeast, Kansas ...

, Hawaii

Hawaii ( ; ) is an island U.S. state, state of the United States, in the Pacific Ocean about southwest of the U.S. mainland. One of the two Non-contiguous United States, non-contiguous U.S. states (along with Alaska), it is the only sta ...

, Idaho

Idaho ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest and Mountain states, Mountain West subregions of the Western United States. It borders Montana and Wyoming to the east, Nevada and Utah to the south, and Washington (state), ...

, Iowa

Iowa ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the upper Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders the Mississippi River to the east and the Missouri River and Big Sioux River to the west; Wisconsin to the northeast, Ill ...

, Kansas

Kansas ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders Nebraska to the north; Missouri to the east; Oklahoma to the south; and Colorado to the west. Kansas is named a ...

, Michigan

Michigan ( ) is a peninsular U.S. state, state in the Great Lakes region, Great Lakes region of the Upper Midwest, Upper Midwestern United States. It shares water and land boundaries with Minnesota to the northwest, Wisconsin to the west, ...

(where an incendiary bomb was found at Farmington in the easternmost incident), Montana

Montana ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is bordered by Idaho to the west, North Dakota to the east, South Dakota to the southeast, Wyoming to the south, an ...

, Nebraska

Nebraska ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders South Dakota to the north; Iowa to the east and Missouri to the southeast, both across the Missouri River; Ka ...

, Nevada

Nevada ( ; ) is a landlocked state in the Western United States. It borders Oregon to the northwest, Idaho to the northeast, California to the west, Arizona to the southeast, and Utah to the east. Nevada is the seventh-most extensive, th ...

, North Dakota

North Dakota ( ) is a U.S. state in the Upper Midwest, named after the indigenous Dakota people, Dakota and Sioux peoples. It is bordered by the Canadian provinces of Saskatchewan and Manitoba to the north and by the U.S. states of Minneso ...

, Oregon

Oregon ( , ) is a U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States. It is a part of the Western U.S., with the Columbia River delineating much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington (state), Washington, while t ...

, South Dakota

South Dakota (; Sioux language, Sioux: , ) is a U.S. state, state in the West North Central states, North Central region of the United States. It is also part of the Great Plains. South Dakota is named after the Dakota people, Dakota Sioux ...

, Texas

Texas ( , ; or ) is the most populous U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. It borders Louisiana to the east, Arkansas to the northeast, Oklahoma to the north, New Mexico to the we ...

, Utah

Utah is a landlocked state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is one of the Four Corners states, sharing a border with Arizona, Colorado, and New Mexico. It also borders Wyoming to the northea ...

, Washington, and Wyoming

Wyoming ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States, Western United States. It borders Montana to the north and northwest, South Dakota and Nebraska to the east, Idaho t ...

; in Canada in Alberta

Alberta is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province in Canada. It is a part of Western Canada and is one of the three Canadian Prairies, prairie provinces. Alberta is bordered by British Columbia to its west, Saskatchewan to its east, t ...

, British Columbia

British Columbia is the westernmost Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada. Situated in the Pacific Northwest between the Pacific Ocean and the Rocky Mountains, the province has a diverse geography, with rugged landscapes that ...

, Manitoba

Manitoba is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada at the Centre of Canada, longitudinal centre of the country. It is Canada's Population of Canada by province and territory, fifth-most populous province, with a population ...

, Saskatchewan

Saskatchewan is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province in Western Canada. It is bordered on the west by Alberta, on the north by the Northwest Territories, on the east by Manitoba, to the northeast by Nunavut, and to the south by the ...

, and the Northwest

The points of the compass are a set of horizontal, radially arrayed compass directions (or azimuths) used in navigation and cartography. A '' compass rose'' is primarily composed of four cardinal directions—north, east, south, and west— ...

and Yukon Territories; in Mexico in Baja California Norte and Sonora

Sonora (), officially Estado Libre y Soberano de Sonora (), is one of the 31 states which, along with Mexico City, comprise the Administrative divisions of Mexico, Federal Entities of Mexico. The state is divided into Municipalities of Sonora, 72 ...

; and at sea. By August 1945, the U.S. Army had recorded 285 balloon incidents (28 by January, 54 in February, 114 in March, 42 in April, 16 in May, 17 in June, and 14 in July).

Alturas, California

Alturas ( Spanish for "Heights"; Achumawi: ''Kasalektawi'') is the only incorporated city in Modoc County, California of which it is also the county seat. Located in the Shasta Cascade region of Northern California, the city had a population ...

, on January 10, 1945, reinflated at Moffett Field

Moffett Federal Airfield , also known as Moffett Field, is a joint civil-military airport located in an unincorporated part of Santa Clara County, California, United States, between northern Mountain View and northern Sunnyvale. On November ...

File:342-FH-3B23424 (18156536642).jpg, Balloon found near Bigelow, Kansas, on February 23, 1945

File:342-FH-3B23423 (17973857089).jpg, Balloon found near Nixon, Nevada

Nixon is a census-designated place (CDP) in Washoe County, Nevada, Washoe County, Nevada, United States, USA. The population was 374 at the United States Census 2010, 2010 census. It is part of the Reno, Nevada, Reno–Sparks, Nevada, Sparks ...

, on March 29, 1945

FIle:342-FH-3B23432 (18160047105).jpg, Aerial photograph of a balloon taken from an American plane

File:342-FH-3B23437 (18133550866).jpg, Another aerial photograph of a balloon

Pacific Northwest

The Pacific Northwest (PNW; ) is a geographic region in Western North America bounded by its coastal waters of the Pacific Ocean to the west and, loosely, by the Rocky Mountains to the east. Though no official boundary exists, the most common ...

during the summer months, the Army's Western Defense Command

Western Defense Command (WDC) was established on 17 March 1941 as the command formation of the United States Army responsible for coordinating the defense of the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast region of the United States during Wo ...

(WDC), Fourth Air Force

The Fourth Air Force (4 AF) is a numbered air force of the Air Force Reserve Command (AFRC). It is headquartered at March Air Reserve Base, California.

4 AF directs the activities and supervises the training of more than 30,000 Air Force Reserv ...

, and Ninth Service Command organized the "Firefly Project" with Stinson L-5 Sentinel and Douglas C-47 Skytrain

The Douglas C-47 Skytrain or Dakota ( RAF designation) is a military transport aircraft developed from the civilian Douglas DC-3 airliner. It was used extensively by the Allies during World War II. During the war the C-47 was used for tro ...

aircraft and 2,700 troops, including 200 paratroopers from the all-black 555th Parachute Infantry Battalion, who were deployed in 36 firefighting missions between May and October 1945. The Army used the U.S. Forest Service

The United States Forest Service (USFS) is an agency within the U.S. Department of Agriculture. It administers the nation's 154 national forests and 20 national grasslands covering of land. The major divisions of the agency are the Chief's ...

as a proxy agency, unifying fire suppression communications between federal and state agencies and modernizing the service through an influx of military personnel, equipment, and tactics. In the WDC's "Lightning Project", health and agricultural officers, veterinarians, and 4-H

4-H is a U.S.-based network of youth organizations whose mission is "engaging youth to reach their fullest potential while advancing the field of youth development". Its name is a reference to the occurrence of the initial letter H four times ...

clubs were instructed to report any new diseases of crops or livestock caused by potential biological warfare

Biological warfare, also known as germ warfare, is the use of biological toxins or Pathogen, infectious agents such as bacteria, viruses, insects, and Fungus, fungi with the intent to kill, harm or incapacitate humans, animals or plants as an ...

. Stocks of decontamination chemicals, ultimately unused, were shipped to key points in the western states. Although biological warfare had been a concern for months, the WDC's plan was not formalized and fully implemented until July 1945. A sub-section of the project, "Arrow", provided for rapid air transportation of all balloon remains to the Technical Air Intelligence Center laboratory in Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from Virginia, and shares land borders with ...

, for biological analysis. A U.S. investigation after the war concluded there had not been plans for chemical or biological payloads.

Army Air Forces

The United States Army Air Forces (USAAF or AAF) was the major land-based aerial warfare service component of the United States Army and ''de facto'' aerial warfare service branch of the United States during and immediately after World War II ...

and Navy fighter planes were scrambled on several occasions to intercept balloons, but they had little success due to inaccurate sighting reports, bad weather, and the very high altitude at which they traveled. In all, only about 20 balloons were shot down by U.S. and Canadian pilots. Attempts to track the radiosonde balloons produced 95 suspected signals, but they were of little use due to the very low proportion of balloons with transmitters, and observed fading of signals as they approached. Experiments on recovered balloons in February 1945 to determine their radar reflectivity were unsuccessful. In the "Sunset Project", initiated in early April and fully operational by June, the Fourth Air Force attempted to detect balloons with search radars at ground-controlled interception

Ground-controlled interception (GCI) is an air defence tactic whereby one or more radar stations or other observational stations are linked to a command communications centre which guides interceptor aircraft to an airborne target. This tactic wa ...

sites in coastal Washington, but the project detected nothing and was cancelled in early August.

Few American officials believed at first that the balloons could have come directly from Japan. Early U.S. theories speculated that they were launched from German prisoner of war camps or from Japanese-American internment centers. After bombs of Japanese origin were found, it was believed that the balloons were launched from coastal submarines. Statistical analysis of valve serial numbers suggested that tens of thousands of balloons had been produced. The mineral and diatom

A diatom (Neo-Latin ''diatoma'') is any member of a large group comprising several Genus, genera of algae, specifically microalgae, found in the oceans, waterways and soils of the world. Living diatoms make up a significant portion of Earth's B ...

composition of sand from the sandbags was studied by the Military Geology Unit of the United States Geological Survey

The United States Geological Survey (USGS), founded as the Geological Survey, is an agency of the U.S. Department of the Interior whose work spans the disciplines of biology, geography, geology, and hydrology. The agency was founded on Mar ...

, which assessed its origin as Shiogama, Miyagi, or less likely, Ichinomiya, Chiba, only the latter being correct. Aerial reconnaissance

Aerial reconnaissance is reconnaissance for a military or Strategy, strategic purpose that is conducted using reconnaissance aircraft. The role of reconnaissance can fulfil a variety of requirements including Artillery observer, artillery spott ...

of Shiogama in May 1945 showed what was mistakenly interpreted as inflated balloons and a possible launch area at the beach.

Censorship campaign

On January 4, 1945, the U.S.Office of Censorship

The Office of Censorship was an emergency wartime agency set up by the United States federal government on December 19, 1941, to aid in the censorship of all communications coming into and going out of the United States, including its territories ...

sent a confidential memo to newspaper editors and radio broadcasters asking that they give no publicity to balloon incidents; this proved highly effective, with the agency sending another memo three months later stating that cooperation had been "excellent" and that "there is no question that your refusal to publish or broadcast information about these balloons has baffled the Japanese, annoyed and hindered them, and has been an important contribution to security." The Imperial Army only ever learned of the balloon at Kalispell from an article in the Chinese newspaper ''Ta Kung Pao

''Ta Kung Pao'' (; formerly ''L'Impartial'' in Latin-based languages) is a Hong Kong-based, state-owned Chinese-language newspaper. Founded in Tianjin in 1902, the paper is controlled by the Liaison Office of the Central People's Government i ...

'' on December 18, 1944. The Kalispell find was originally reported on December 14 by the ''Western News'', a weekly published in Libby, Montana

Libby is a city in northwestern Montana, United States and the county seat of Lincoln County, Montana, Lincoln County. The population was 2,775 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census.

Libby suffered from the area's contamination from nea ...

; the story later appeared in articles in the January 1, 1945, editions of ''Time

Time is the continuous progression of existence that occurs in an apparently irreversible process, irreversible succession from the past, through the present, and into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequ ...

'' and ''Newsweek

''Newsweek'' is an American weekly news magazine based in New York City. Founded as a weekly print magazine in 1933, it was widely distributed during the 20th century and has had many notable editors-in-chief. It is currently co-owned by Dev P ...

'' magazines, as well as on the front page of the January 2 edition of ''The Oregonian

''The Oregonian'' is a daily newspaper based in Portland, Oregon, United States, owned by Advance Publications. It is the oldest continuously published newspaper on the West Coast of the United States, U.S. West Coast, founded as a weekly by Tho ...

'' of Portland, Oregon

Portland ( ) is the List of cities in Oregon, most populous city in the U.S. state of Oregon, located in the Pacific Northwest region. Situated close to northwest Oregon at the confluence of the Willamette River, Willamette and Columbia River, ...

, before the Office of Censorship sent the memo. Starting in mid-February 1945, Japanese propaganda broadcasts falsely announced numerous fires and a panicked American public, further claiming casualties in the hundreds or thousands.

One breach occurred in late February, when Representative Arthur L. Miller

Arthur Lewis Miller (May 24, 1892 – March 16, 1967) was a Nebraska United States Republican Party, Republican politician.

Born on a farm near Plainview, Nebraska, he graduated from the Plainview High School in 1911. He then taught rural schoo ...

mentioned the balloons in a weekly column he sent to all 91 newspapers in his Nebraska district, which stated in part: "As a final act of desperation, it is believed that the Japs may release fire balloons aimed at our great forests in the northwest". In response, intelligence officers at the Seventh Service Command in Omaha contacted the editors at all 91 papers, requesting censorship; this was largely successful, with only two papers printing the column. In late March, the United Press

United Press International (UPI) is an American international news agency whose newswires, photo, news film, and audio services provided news material to thousands of newspapers, magazines, radio and television stations for most of the 20th ...

(UP) wrote a detailed article on the balloons intended for its national distributors; the Army officer who reported the breach commented that it included "a lot of mechanical detail on the thing, in addition to being a hell of a scare story". Censors contacted the UP, which replied that the article had not yet been teletyped; all five copies were retrieved and destroyed. Investigators determined the information originated from a briefing to Colorado state legislators, which had been leaked in an open session.

In late April, censors investigated the nationally-syndicated comic strip '' Tim Tyler's Luck'' by Lyman Young, which depicted a Japanese balloon recovered by the crew of a U.S. submarine. In subsequent weeks, its protagonists fought monster vines which sprang from seeds the balloon was carrying, created by an evil Japanese horticulturalist. A few weeks later, the comic strip '' Smilin' Jack'' by Zack Mosley depicted a plane crashing into a Japanese balloon, which exploded and started a fire upon falling to the ground. In both cases, the Office of Censorship deemed it unnecessary to censor the Sunday comics

The Sunday comics or Sunday strip is the comic strip section carried in some Western newspapers. Compared to weekday comics, Sunday comics tend to be full pages and are in color. Many newspaper readers called this section the Sunday funnies, t ...

.

Abandonment and results

By mid-April 1945, Japan lacked the resources to continue manufacturing balloons, with both paper and hydrogen in short supply. Furthermore, the Army had little evidence that the balloons were reaching North America, let alone causing damage. The campaign was halted, with no intention to revive it when the jet stream regained strength in fall 1945. The last balloon was launched on April 20. In total, about 9,300 were launched in the campaign (about 700 in November 1944, 1,200 in December, 2,000 in January 1945, 2,500 in February, 2,500 in March, and 400 in April), of which about 300 were found or observed in North America. The Fu-Go balloon bomb is considered to be the first weapon system in history with intercontinental range, a significant development in warfare which was followed by the advent of the world's firstintercontinental ballistic missile

An intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) is a ballistic missile with a range (aeronautics), range greater than , primarily designed for nuclear weapons delivery (delivering one or more Thermonuclear weapon, thermonuclear warheads). Conven ...

(ICBM), the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

's R-7, in 1957.

Only "one or two" small grass fires were attributed to the balloon bombs. As predicted by Imperial Army officials, the winter and spring launch dates had limited the chances of the incendiaries starting fires due to the high levels of precipitation in the Pacific Northwest; forests were generally snow-covered or too damp to catch fire easily. Furthermore, much of the western U.S. received disproportionately more precipitation in 1945 than in any other year in the decade, with some areas receiving of precipitation more than other years. The most damaging attack occurred on March 10, 1945, when a balloon descended near Toppenish, Washington, and collided with electric transmission lines, causing a short circuit

A short circuit (sometimes abbreviated to short or s/c) is an electrical circuit that allows a current to travel along an unintended path with no or very low electrical impedance. This results in an excessive current flowing through the circuit ...

which cut off power to the Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development program undertaken during World War II to produce the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States in collaboration with the United Kingdom and Canada.

From 1942 to 1946, the ...

's production facility at the state's Hanford Engineer Works. Backup devices restored power to the site, but it took three days for its plutonium

Plutonium is a chemical element; it has symbol Pu and atomic number 94. It is a silvery-gray actinide metal that tarnishes when exposed to air, and forms a dull coating when oxidized. The element normally exhibits six allotropes and four ...

-producing nuclear reactor

A nuclear reactor is a device used to initiate and control a Nuclear fission, fission nuclear chain reaction. They are used for Nuclear power, commercial electricity, nuclear marine propulsion, marine propulsion, Weapons-grade plutonium, weapons ...

s to be restored to full capacity; the plutonium was later used in Fat Man

"Fat Man" (also known as Mark III) was the design of the nuclear weapon the United States used for seven of the first eight nuclear weapons ever detonated in history. It is also the most powerful design to ever be used in warfare.

A Fat Man ...

, the atomic bomb dropped on Nagasaki.

Single lethal attack

On May 5, 1945, six civilians were killed near Bly, Oregon, when they discovered one of the balloon bombs in Fremont National Forest, becoming the only fatalities from Axis action in the continental U.S. during the war. Reverend Archie Mitchell and his pregnant wife Elsie (age 26) drove up Gearhart Mountain that day with five of theirSunday school

]

A Sunday school, sometimes known as a Sabbath school, is an educational institution, usually Christianity, Christian in character and intended for children or neophytes.

Sunday school classes usually precede a Sunday church service and are u ...

students for a picnic. While Archie was parking the car, Elsie and the children discovered a balloon and carriage, loaded with an anti-personnel bomb, on the ground. A large explosion occurred; the four boys (Edward Engen, 13; Jay Gifford, 13; Dick Patzke, 14; and Sherman Shoemaker, 11) were killed instantly, while Elsie and Joan Patzke (13) died from their wounds shortly afterwards. An Army investigation concluded that the bomb had likely been kicked or dropped, and that it had lain undisturbed for about one month before the incident. The U.S. press blackout was lifted on May 22 so the public could be warned of the balloon threat.

A memorial, the Mitchell Monument, was built in 1950 at the site of the explosion, and the surrounding Mitchell Recreation Area was listed on the National Register of Historic Places

The National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) is the Federal government of the United States, United States federal government's official United States National Register of Historic Places listings, list of sites, buildings, structures, Hist ...

in 2003. A ponderosa pine

''Pinus ponderosa'', commonly known as the ponderosa pine, bull pine, blackjack pine, western yellow-pine, or filipinus pine, is a very large pine tree species of variable habitat native to mountainous regions of western North America. It is t ...

near the site bears scars on its trunk from the bomb's shrapnel. In 1987, a group of Japanese women involved in Fu-Go production as schoolgirls delivered 1,000 paper cranes to the victims' families as a symbol of peace and healing, and six cherry trees were planted at the site on the incident's 50th anniversary in 1995.

After World War II

All Japanese records on the Fu-Go program were destroyed in compliance with a directive issued on August 15, 1945, the day Japan announced its surrender. Thus, a single interview with Lieutenant Colonel Terato Kunitake of the Army General Staff and a Major Inouye became the source of nearly all information on the project's objectives for U.S. investigators. A five-volume report, prepared by a team led by Karl T. Compton of theOffice of Scientific Research and Development

The Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD) was an agency of the United States federal government created to coordinate scientific research for military purposes during World War II. Arrangements were made for its creation during May ...

and Edward L. Moreland of MIT

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) is a private research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Established in 1861, MIT has played a significant role in the development of many areas of modern technology and sc ...

, was later submitted to President Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. As the 34th vice president in 1945, he assumed the presidency upon the death of Franklin D. Roosevelt that year. Subsequen ...

.

The remains of balloons have continued to be discovered after the war. At least eight were found in the 1940s, three in the 1950s, two in the 1960s, and one in the 1970s. A carriage with a live bomb was found near Lumby, British Columbia, in 2014 and detonated by a Royal Canadian Navy

The Royal Canadian Navy (RCN; , ''MRC'') is the Navy, naval force of Canada. The navy is one of three environmental commands within the Canadian Armed Forces. As of February 2024, the RCN operates 12 s, 12 s, 4 s, 4 s, 8 s, and several auxiliary ...

ordnance disposal team. Remains of another balloon were found near McBride, British Columbia, in 2019. Many war museums in the U.S. and Canada hold Fu-Go fragments, including the National Air and Space Museum

The National Air and Space Museum (NASM) of the Smithsonian Institution is a museum in Washington, D.C., in the United States, dedicated to history of aviation, human flight and space exploration.

Established in 1946 as the National Air Museum, ...

and the Canadian War Museum

The Canadian War Museum (CWM) () is a National museums of Canada, national museum on the military history of Canada, country's military history in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. The museum serves as both an educational facility on Canadian military hist ...

.

See also

* E77 balloon bomb – 1950s U.S. biological weapon inspired by Fu-Go * History of military ballooning – Includes Austrian use of balloon bombs at Venice in 1849 * Operation Outward – WWII British attack on Germany with balloon bombs * WS-124A Flying Cloud – 1950s U.S. Air Force balloon bomb programNotes

References

Works cited

* *Further reading

* * *External links

Report on Fu-Go balloons by the U.S. Technical Air Intelligence Center, May 1945

* {{Authority control American Theater of World War II Balloon weaponry Balloons (aeronautics) Incendiary weapons Japanese inventions Weapons and ammunition introduced in 1944 World War II weapons of Japan