Franz von Papen on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

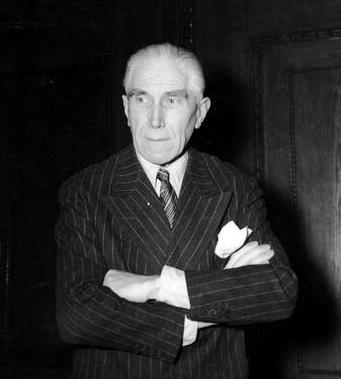

Franz Joseph Hermann Michael Maria von Papen, (; 29 October 18792 May 1969) was a German politician, diplomat, Prussian nobleman and army officer. A national conservative, he served as

On 1 June 1932, Papen was suddenly promoted to high office when President Hindenburg appointed him

On 1 June 1932, Papen was suddenly promoted to high office when President Hindenburg appointed him  On 27 October, the Supreme Court of Germany issued a ruling that Papen's coup deposing the Prussian government was illegal, but allowed Papen to retain control of Prussia. In November 1932, Papen violated the terms of the Treaty of Versailles by approving a program of refurbishment for the German Navy of an aircraft carrier, six battleships, six cruisers, six destroyer flotillas, and 16 submarines, intended to allow Germany to control both the North Sea and the Baltic.

In the November 1932 election, the Nazis lost seats, but Papen was still unable to secure a Reichstag that could be counted on not to pass another vote of no-confidence in his government. Papen's attempt to negotiate with Hitler failed. Under pressure from Schleicher, Papen resigned on 17 November and formed a caretaker government. He told his cabinet that he planned to have martial law declared, which would allow him to rule as a dictator. However, at a cabinet meeting on 2 December, Papen was informed by Schleicher's associate General Eugen Ott about the dubious results of ''

On 27 October, the Supreme Court of Germany issued a ruling that Papen's coup deposing the Prussian government was illegal, but allowed Papen to retain control of Prussia. In November 1932, Papen violated the terms of the Treaty of Versailles by approving a program of refurbishment for the German Navy of an aircraft carrier, six battleships, six cruisers, six destroyer flotillas, and 16 submarines, intended to allow Germany to control both the North Sea and the Baltic.

In the November 1932 election, the Nazis lost seats, but Papen was still unable to secure a Reichstag that could be counted on not to pass another vote of no-confidence in his government. Papen's attempt to negotiate with Hitler failed. Under pressure from Schleicher, Papen resigned on 17 November and formed a caretaker government. He told his cabinet that he planned to have martial law declared, which would allow him to rule as a dictator. However, at a cabinet meeting on 2 December, Papen was informed by Schleicher's associate General Eugen Ott about the dubious results of ''

Hitler offered Papen the assignment of German ambassador to

Hitler offered Papen the assignment of German ambassador to  Papen also contributed to achieving Hitler's goal of undermining Austrian sovereignty and bringing about the ''Anschluss''. On 28 August 1935, Papen negotiated a deal under which the German press would cease its attacks on the Austrian government, in return for which the Austrian press would cease its attacks on Germany's. Papen played a major role in negotiating the 1936 Austro-German agreement under which Austria declared itself a "German state" whose foreign policy would always be aligned with Berlin's and allowed for members of the "national opposition" to enter the Austrian cabinet in exchange for which the Austrian Nazis abandoned their terrorist campaign against the government. The treaty Papen signed in Vienna on 11 July 1936 promised that Germany would not seek to annex Austria and largely placed Austria in the German sphere of influence, greatly reducing Italian influence on Austria. In July 1936, Papen reported to Hitler that the Austro-German treaty he had just signed was the "decisive step" towards ending Austrian independence, and it was only a matter of time before the ''Anschluss'' took place.

In the summer and fall of 1937, Papen pressured the Austrians to include more Nazis in the government. In September 1937, Papen returned to Berlin when

Papen also contributed to achieving Hitler's goal of undermining Austrian sovereignty and bringing about the ''Anschluss''. On 28 August 1935, Papen negotiated a deal under which the German press would cease its attacks on the Austrian government, in return for which the Austrian press would cease its attacks on Germany's. Papen played a major role in negotiating the 1936 Austro-German agreement under which Austria declared itself a "German state" whose foreign policy would always be aligned with Berlin's and allowed for members of the "national opposition" to enter the Austrian cabinet in exchange for which the Austrian Nazis abandoned their terrorist campaign against the government. The treaty Papen signed in Vienna on 11 July 1936 promised that Germany would not seek to annex Austria and largely placed Austria in the German sphere of influence, greatly reducing Italian influence on Austria. In July 1936, Papen reported to Hitler that the Austro-German treaty he had just signed was the "decisive step" towards ending Austrian independence, and it was only a matter of time before the ''Anschluss'' took place.

In the summer and fall of 1937, Papen pressured the Austrians to include more Nazis in the government. In September 1937, Papen returned to Berlin when

Papen was captured along with his son Franz Jr. at his own home on 14 April 1945. Papen was forced by the US to visit a

Papen was captured along with his son Franz Jr. at his own home on 14 April 1945. Papen was forced by the US to visit a  Papen was one of the defendants at the main Nuremberg War Crimes Trial. The investigating tribunal found no solid evidence to support claims that Papen had been involved in the annexation of Austria. The court acquitted him, stating that while he had committed a number of "political immoralities", these actions were not punishable under the "conspiracy to commit crimes against peace" written in Papen's indictment. The Soviets wanted to execute him.

Papen was subsequently sentenced to eight years' hard labour by a West German denazification court, but he was released on appeal in 1949. Until 1954, Papen was forbidden to publish in

Papen was one of the defendants at the main Nuremberg War Crimes Trial. The investigating tribunal found no solid evidence to support claims that Papen had been involved in the annexation of Austria. The court acquitted him, stating that while he had committed a number of "political immoralities", these actions were not punishable under the "conspiracy to commit crimes against peace" written in Papen's indictment. The Soviets wanted to execute him.

Papen was subsequently sentenced to eight years' hard labour by a West German denazification court, but he was released on appeal in 1949. Until 1954, Papen was forbidden to publish in  Papen published a number of books and memoirs, in which he defended his policies and dealt with the years 1930 to 1933 as well as early Western

Papen published a number of books and memoirs, in which he defended his policies and dealt with the years 1930 to 1933 as well as early Western

excerpt

* *

Biographical timeline

Vice-Chancellor Franz von Papen speaks in Trier about the Saarland referendum, 1934

Papen at the Republic Day celebrations in Turkey, 1941

* * , - , - , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Papen, Franz Von 1879 births 1969 deaths 20th-century chancellors of Germany 20th-century German landowners 20th-century German nobility Ambassadors of Germany to Austria Ambassadors of Germany to Turkey Anti-Marxism Anti-Masonry Antisemitism in Germany Centre Party (Germany) politicians Diplomats in the Nazi Party Espionage in the United States German anti-communists German Army personnel of World War I German military attachés German monarchists German nationalists German people of World War II German Roman Catholics German untitled nobility Government ministers of Nazi Germany Hindu–German Conspiracy Knights of Malta Members of the Academy for German Law Members of the Landtag of Prussia Members of the Order of the Holy Sepulchre Members of the Reichstag 1933 Members of the Reichstag 1933–1936 Members of the Reichstag 1936–1938 Members of the Reichstag 1938–1945 Nazis convicted of crimes Nobility in the Nazi Party Ottoman military personnel of World War I Papal chamberlains People acquitted by the International Military Tribunal in Nuremberg People deported from the United States People from the Province of Westphalia People from Werl Minister presidents of Prussia Prisoners and detainees of Germany Prussian Army personnel Recipients of the Iron Cross (1914), 1st class Recipients of the Knights Cross of the War Merit Cross Vice-chancellors of Germany Weimar Republic politicians World War I spies for Germany

Chancellor of Germany

The chancellor of Germany, officially the federal chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany, is the head of the federal Cabinet of Germany, government of Germany. The chancellor is the chief executive of the Federal Government of Germany, ...

in 1932, and then as Vice-Chancellor

A vice-chancellor (commonly called a VC) serves as the chief executive of a university in the United Kingdom, New Zealand, Australia, Nepal, India, Bangladesh, Malaysia, Nigeria, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, South Africa, Kenya, other Commonwealth of Nati ...

under Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

from 1933 to 1934. Papen is largely remembered for his role in bringing Hitler to power.

Born into a wealthy family of Westphalia

Westphalia (; ; ) is a region of northwestern Germany and one of the three historic parts of the state of North Rhine-Westphalia. It has an area of and 7.9 million inhabitants.

The territory of the region is almost identical with the h ...

n Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

aristocrats, Papen served in the Prussian Army from 1898 onward and was trained as an officer of the German General Staff

The German General Staff, originally the Prussian General Staff and officially the Great General Staff (), was a full-time body at the head of the Prussian Army and later, the Imperial German Army, German Army, responsible for the continuous stu ...

. He served as a military attaché

A military attaché or defence attaché (DA),Defence Attachés

''Geneva C ...

in Mexico and the United States from 1913 to 1915, while also covertly organising acts of ''Geneva C ...

sabotage

Sabotage is a deliberate action aimed at weakening a polity, government, effort, or organization through subversion, obstruction, demoralization (warfare), demoralization, destabilization, divide and rule, division, social disruption, disrupti ...

in the United States and quietly backing and financing Mexican forces in the Mexican Revolution

The Mexican Revolution () was an extended sequence of armed regional conflicts in Mexico from 20 November 1910 to 1 December 1920. It has been called "the defining event of modern Mexican history". It saw the destruction of the Federal Army, its ...

on behalf of German military intelligence

Military intelligence is a military discipline that uses information collection and analysis List of intelligence gathering disciplines, approaches to provide guidance and direction to assist Commanding officer, commanders in decision making pr ...

. After being expelled as persona non grata

In diplomacy, a ' (PNG) is a foreign diplomat that is asked by the host country to be recalled to their home country. If the person is not recalled as requested, the host state may refuse to recognize the person concerned as a member of the diplo ...

by the United States State Department in 1915, he served as a battalion commander on the Western Front of World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

and finished his war service in the Middle Eastern theatre as a lieutenant colonel.

Asked to become chancellor of the Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic, officially known as the German Reich, was the German Reich, German state from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a constitutional republic for the first time in history; hence it is also referred to, and unofficially proclai ...

by President Paul von Hindenburg

Paul Ludwig Hans Anton von Beneckendorff und von Hindenburg (2 October 1847 – 2 August 1934) was a German military and political leader who led the Imperial German Army during the First World War and later became President of Germany (1919� ...

in 1932, Papen ruled by presidential decree. He launched the '' Preußenschlag'' coup against the Social Democratic Party-led Government in the Free State of Prussia

The Free State of Prussia (, ) was one of the States of the Weimar Republic, constituent states of Weimar Republic, Germany from 1918 to 1947. The successor to the Kingdom of Prussia after the defeat of the German Empire in World War I, it cont ...

. His failure to secure a base of support in the Reichstag led to his removal by Hindenburg and replacement by General Kurt von Schleicher.

Determined to return to power and regain his wealth, Papen, believing that Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

could be controlled once he was in the government, pressured Hindenburg to appoint Hitler as chancellor and Papen as vice-chancellor in 1933 in a cabinet ostensibly not under Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party ( or NSDAP), was a far-right politics, far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that created and supported the ideology of Nazism. Its precursor ...

domination. Seeing military dictatorship

A military dictatorship, or a military regime, is a type of dictatorship in which Power (social and political), power is held by one or more military officers. Military dictatorships are led by either a single military dictator, known as a Polit ...

as the only alternative to a Nazi Party chancellor, Hindenburg consented. Papen and his allies were quickly marginalized by Hitler and he left the government after the Night of the Long Knives purge in 1934, during which the Nazis killed some of his allies and confidants. Subsequently, Papen served the German Foreign Office as the ambassador in Vienna

Vienna ( ; ; ) is the capital city, capital, List of largest cities in Austria, most populous city, and one of Federal states of Austria, nine federal states of Austria. It is Austria's primate city, with just over two million inhabitants. ...

from 1934 to 1938 and in Ankara

Ankara is the capital city of Turkey and List of national capitals by area, the largest capital by area in the world. Located in the Central Anatolia Region, central part of Anatolia, the city has a population of 5,290,822 in its urban center ( ...

from 1939 to 1944. He joined the Nazi Party in 1938.

After the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, Papen was indicted for Nazi war crimes in the Nuremberg trials #REDIRECT Nuremberg trials

{{redirect category shell, {{R from other capitalisation{{R from move ...

before the International Military Tribunal but was acquitted of all charges. In 1947, a West German denazification court found Papen to have acted as the main culprit in crimes relating to the Nazi government. Papen was given a sentence of eight years' imprisonment at hard labour, but was released on appeal

In law, an appeal is the process in which Legal case, cases are reviewed by a higher authority, where parties request a formal change to an official decision. Appeals function both as a process for error correction as well as a process of cla ...

in 1949. Franz von Papen's memoirs were published in 1952 and 1953; he died in 1969.

Early life and education

Papen was born into a wealthy and nobleCatholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

family in Werl

The pilgrimage town Werl (; Westphalian language, Westphalian: ''Wiärl'') is a town in North Rhine-Westphalia and belongs to the Soest, Germany, Soest district in the Arnsberg administrative district. The official name of pilgrimage town has been ...

, Westphalia

Westphalia (; ; ) is a region of northwestern Germany and one of the three historic parts of the state of North Rhine-Westphalia. It has an area of and 7.9 million inhabitants.

The territory of the region is almost identical with the h ...

, the third child of (1839–1906) and his wife Anna Laura von Steffens (1852–1939). His father, a cavalry officer in the Prussian Army, had served in the Second Schleswig War

The Second Schleswig War (; or German Danish War), also sometimes known as the Dano-Prussian War or Prusso-Danish War, was the second military conflict over the Schleswig–Holstein question of the nineteenth century. The war began on 1 Februar ...

, the Austro-Prussian War

The Austro-Prussian War (German: ''Preußisch-Österreichischer Krieg''), also known by many other names,Seven Weeks' War, German Civil War, Second War of Unification, Brothers War or Fraternal War, known in Germany as ("German War"), ''Deutsc ...

, and the Franco-Prussian War

The Franco-Prussian War or Franco-German War, often referred to in France as the War of 1870, was a conflict between the Second French Empire and the North German Confederation led by the Kingdom of Prussia. Lasting from 19 July 1870 to 28 Janua ...

, taking part in the battles of Dybbøl, Königgrätz, and Sedan, and in the Siege of Paris. He was also a friend of Kaiser Wilhelm II

Wilhelm II (Friedrich Wilhelm Viktor Albert; 27 January 18594 June 1941) was the last German Emperor and King of Prussia from 1888 until Abdication of Wilhelm II, his abdication in 1918, which marked the end of the German Empire as well as th ...

, whom he had met as a student in Bonn

Bonn () is a federal city in the German state of North Rhine-Westphalia, located on the banks of the Rhine. With a population exceeding 300,000, it lies about south-southeast of Cologne, in the southernmost part of the Rhine-Ruhr region. This ...

, where both men had been members of the Corps Borussia Bonn

The Corps Borussia Bonn is a German Student Corps at the University of Bonn.

History

Borussia was established on 22 December 1821 and joined the Kösener Senioren-Convents-Verband (KSCV) in 1856. It is the corps of the House of Hohenzollern a ...

; after his military career, he held several posts in local politics, including that of honorary deputy mayor (''Bürgermeister'') of Werl

The pilgrimage town Werl (; Westphalian language, Westphalian: ''Wiärl'') is a town in North Rhine-Westphalia and belongs to the Soest, Germany, Soest district in the Arnsberg administrative district. The official name of pilgrimage town has been ...

. Members of the Papen family, which held '' erbsälzer'' status, had enjoyed the hereditary right to mine brine salt at Werl since 1298, a fact of which Franz was very proud; he always believed in the superiority of the aristocracy over commoners.

Papen was sent to a cadet school in Bensberg of his own volition at the age of 11 in 1891. His four years there were followed by three years of training at the in Lichterfelde. He was trained as a ("gentleman rider"). He served for a period as a military attendant in the Kaiser

Kaiser ( ; ) is the title historically used by German and Austrian emperors. In German, the title in principle applies to rulers anywhere in the world above the rank of king (). In English, the word ''kaiser'' is mainly applied to the emperors ...

's Palace and as a second lieutenant in his father's old unit, the in Düsseldorf

Düsseldorf is the capital city of North Rhine-Westphalia, the most populous state of Germany. It is the second-largest city in the state after Cologne and the List of cities in Germany with more than 100,000 inhabitants, seventh-largest city ...

. Papen joined the German General Staff

The German General Staff, originally the Prussian General Staff and officially the Great General Staff (), was a full-time body at the head of the Prussian Army and later, the Imperial German Army, German Army, responsible for the continuous stu ...

as a captain in March 1913.

On 3 May 1905, he married (1880–1961), the daughter of , a wealthy Saarland industrialist and member of the Villeroy & Boch dynasty of ceramics manufacturers; her dowry made him a very rich man. An excellent horseman and a man of much charm, Papen cut a dashing figure and during this time, befriended Kurt von Schleicher. Fluent in both French and English, he travelled widely all over Europe, the Middle East and North America. He was devoted to Kaiser Wilhelm II

Wilhelm II (Friedrich Wilhelm Viktor Albert; 27 January 18594 June 1941) was the last German Emperor and King of Prussia from 1888 until Abdication of Wilhelm II, his abdication in 1918, which marked the end of the German Empire as well as th ...

. Influenced by the books of General Friedrich von Bernhardi, Papen was a militarist throughout his life.

Military attaché and spymaster in Washington, D.C.

He entered the diplomatic service in December 1913 as amilitary attaché

A military attaché or defence attaché (DA),Defence Attachés

''Geneva C ...

to the German ambassador in the United States.

In early 1914 he travelled to ''Geneva C ...

Mexico

Mexico, officially the United Mexican States, is a country in North America. It is the northernmost country in Latin America, and borders the United States to the north, and Guatemala and Belize to the southeast; while having maritime boundar ...

(to which he was also accredited) and observed the Mexican Revolution

The Mexican Revolution () was an extended sequence of armed regional conflicts in Mexico from 20 November 1910 to 1 December 1920. It has been called "the defining event of modern Mexican history". It saw the destruction of the Federal Army, its ...

. At one time, when the anti-Huerta Zapatistas were advancing on Mexico City, Papen organised a group of European volunteers to fight for Mexican General Victoriano Huerta

José Victoriano Huerta Márquez (; 23 December 1850 – 13 January 1916) was a Mexican general, politician, engineer and dictator who was the 39th President of Mexico, who came to power by coup against the democratically elected government of ...

. In the spring of 1914, as German military attaché to Mexico, Papen was deeply involved in selling arms to the government of General Huerta, believing he could place Mexico in the German sphere of influence, though the collapse of Huerta's regime in July 1914 ended that hope. In April 1914, Papen personally observed the United States occupation of Veracruz when the US seized the city of Veracruz

Veracruz, formally Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave, officially the Free and Sovereign State of Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave, is one of the 31 states which, along with Mexico City, comprise the 32 Political divisions of Mexico, Federal Entit ...

, despite orders from Berlin to stay in Mexico City. During his time in Mexico, Papen acquired the love of international intrigue and adventure that characterised his later diplomatic postings in the United States, Austria and Turkey. On 30 July 1914, Papen arrived in Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from Virginia, and shares land borders with ...

, from Mexico to take up his post as German military attaché to the United States.

During the First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, Papen tried to buy weapons for Germany in the United States, but the British blockade made shipping arms to Germany almost impossible. On 22 August 1914, Papen hired US private detective Paul Koenig, based in New York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

, to conduct a sabotage and bombing campaign against businesses in New York owned by citizens from the Allied nations. Papen, who was given an unlimited fund of cash to draw on by Berlin, attempted to block the British, French and Russian governments from buying war supplies in the United States. Papen set up a front company that tried to preclusively purchase every hydraulic press in the US for the next two years to limit artillery shell production by US firms with contracts with the Allies. To enable German citizens living in the Americas to return to Germany, Papen set up an operation in New York to forge US passports.

Starting in September 1914, Papen abused his diplomatic immunity

Diplomatic immunity is a principle of international law by which certain foreign government officials are recognized as having legal immunity from the jurisdiction of another country.

as German military attaché, violating US laws to start organising plans for incursions into Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its Provinces and territories of Canada, ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, making it the world's List of coun ...

for a campaign of sabotage

Sabotage is a deliberate action aimed at weakening a polity, government, effort, or organization through subversion, obstruction, demoralization (warfare), demoralization, destabilization, divide and rule, division, social disruption, disrupti ...

against canals, bridges and railroads. In October 1914, Papen became involved with what was later dubbed "the Hindu–German Conspiracy", by covertly arranging with Indian nationalists based in California

California () is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States that lies on the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. It borders Oregon to the north, Nevada and Arizona to the east, and shares Mexico–United States border, an ...

for arms trafficking

Arms trafficking or gunrunning is the illicit trade of contraband small arms, explosives, and ammunition, which constitutes part of a broad range of illegal activities often associated with transnational criminal organizations. The illegal tra ...

to the latter for a planned uprising against the British Raj

The British Raj ( ; from Hindustani language, Hindustani , 'reign', 'rule' or 'government') was the colonial rule of the British The Crown, Crown on the Indian subcontinent,

*

* lasting from 1858 to 1947.

*

* It is also called Crown rule ...

. In February 1915, Papen also covertly organised the Vanceboro international bridge bombing, in which his diplomatic immunity protected him from arrest. At the same time, he remained involved in plans to restore Huerta to power, and arranged for the arming and financing of a planned invasion of Mexico.

Papen's covert operations were known to British intelligence, which shared its information with the US government. As a result, for complicity in the planning of acts of sabotage on 28 December 1915, Papen was declared ''persona non grata

In diplomacy, a ' (PNG) is a foreign diplomat that is asked by the host country to be recalled to their home country. If the person is not recalled as requested, the host state may refuse to recognize the person concerned as a member of the diplo ...

'' and recalled to Germany.''Current Biography 1941'', pp. 651–653. Upon his return, he was awarded the Iron Cross

The Iron Cross (, , abbreviated EK) was a military decoration in the Kingdom of Prussia, the German Empire (1871–1918), and Nazi Germany (1933–1945). The design, a black cross pattée with a white or silver outline, was derived from the in ...

.

Papen remained involved in covert operations in the Americas. In February 1916, he contacted Mexican Colonel Gonzalo Enrile, living in Cuba

Cuba, officially the Republic of Cuba, is an island country, comprising the island of Cuba (largest island), Isla de la Juventud, and List of islands of Cuba, 4,195 islands, islets and cays surrounding the main island. It is located where the ...

, in an attempt to arrange German support for Félix Díaz, the would-be strongman of Mexico. Papen served as an intermediary between Roger Casement of the Irish Volunteers

The Irish Volunteers (), also known as the Irish Volunteer Force or the Irish Volunteer Army, was a paramilitary organisation established in 1913 by nationalists and republicans in Ireland. It was ostensibly formed in response to the format ...

and German naval intelligence for the purchase and delivery of arms to be used in Dublin

Dublin is the capital and largest city of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. Situated on Dublin Bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster, and is bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, pa ...

during the Easter Rising

The Easter Rising (), also known as the Easter Rebellion, was an armed insurrection in Ireland during Easter Week in April 1916. The Rising was launched by Irish republicans against British rule in Ireland with the aim of establishing an ind ...

of 1916. He remained involved in further covert operations with Indian nationalists as well. In April 1916, a US federal grand jury

A grand jury is a jury empowered by law to conduct legal proceedings, investigate potential criminal conduct, and determine whether criminal charges should be brought. A grand jury may subpoena physical evidence or a person to testify. A grand ju ...

returned an indictment against Papen for a plot to blow up Canada's Welland Canal

The Welland Canal is a ship canal in Ontario, Canada, and part of the St. Lawrence Seaway and Great Lakes Waterway. The canal traverses the Niagara Peninsula between Port Weller, Ontario, Port Weller on Lake Ontario, and Port Colborne on Lak ...

; he remained under indictment until he became Chancellor of Germany in mid-1932, at which time the charges were dropped.

Army service in World War I

As a Catholic, Papen belonged to the '' Centre Party'', the centrist party that almost all German Catholics supported, but during the course of the war, the nationalist conservative Papen became estranged from his party. Papen disapproved of Matthias Erzberger's cooperation with Social Democrats, and regarded the Reichstag Peace Resolution of 19 July 1917 as almost treason. Later in World War I, Papen returned to the army on active service, at first on the Western Front. In 1916 Papen took command of the 2nd Battalion of the 93rd Reserve Infantry Regiment of the 4th Guards Infantry Division fighting inFlanders

Flanders ( or ; ) is the Dutch language, Dutch-speaking northern portion of Belgium and one of the communities, regions and language areas of Belgium. However, there are several overlapping definitions, including ones related to culture, la ...

. On 22 August 1916, Papen's battalion took heavy losses while successfully resisting a British attack during the Battle of the Somme

The Battle of the Somme (; ), also known as the Somme offensive, was a battle of the First World War fought by the armies of the British Empire and the French Third Republic against the German Empire. It took place between 1 July and 18 Nove ...

. Between November 1916 – February 1917, Papen's battalion was engaged in almost continuous heavy fighting. He was awarded the Iron Cross, 1st Class. On 11 April 1917, Papen fought at Vimy Ridge, where his battalion was defeated with heavy losses by the Canadian Corps

The Canadian Corps was a World War I corps formed from the Canadian Expeditionary Force in September 1915 after the arrival of the 2nd Canadian Division in France. The corps was expanded by the addition of the 3rd Canadian Division in December 19 ...

.

After Vimy, Papen asked for a transfer to the Middle East, which was approved. From June 1917 Papen served as an officer on the General Staff in the Middle East, and then as an officer attached to the Ottoman army in Palestine

Palestine, officially the State of Palestine, is a country in West Asia. Recognized by International recognition of Palestine, 147 of the UN's 193 member states, it encompasses the Israeli-occupied West Bank, including East Jerusalem, and th ...

. During his time in Constantinople, Papen befriended Joachim von Ribbentrop

Ulrich Friedrich-Wilhelm Joachim von Ribbentrop (; 30 April 1893 – 16 October 1946) was a German Nazi politician and diplomat who served as Minister for Foreign Affairs (Germany), Minister of Foreign Affairs of Nazi Germany from 1938 to 1945. ...

. Between October–December 1917, Papen took part in the heavy fighting in the Sinai and Palestine Campaign. He was promoted to the rank of '' Oberstleutnant''.

After the Turks signed an armistice with the Allies on 30 October 1918, the German Asia Corps was ordered home, and Papen was in the mountains at Karapinar when he heard on 11 November 1918 that the war was over. The new republic ordered soldiers' councils to be organised in the German Army, including the Asian corps, which General Otto Liman von Sanders attempted to obey, and which Papen refused to obey. Sanders ordered Papen arrested for his insubordination, which caused Papen to leave his post without permission as he fled to Germany in civilian clothing to personally meet Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg

Paul Ludwig Hans Anton von Beneckendorff und von Hindenburg (2 October 1847 – 2 August 1934) was a German military and political leader who led the Imperial German Army during the First World War and later became President of Germany (1919� ...

, who had the charges dropped.

Catholic politician

After leaving the German Army in the spring of 1919, Papen purchased the , a country estate in Dülmen, and became a gentleman farmer. In April 1920, during the Communist uprising in the Ruhr, Papen took command of a unit to protect Catholicism from the " Red marauders". Impressed with his leadership of his unit, Papen was urged to pursue a career in politics. In the fall of 1920, the president of the Westphalian Farmer's Association, Baron Engelbert von Kerkerinck zur Borg, told Papen his association would campaign for him if he ran for the Prussian . Papen entered politics and renewed his connection with the Centre Party. As a monarchist Papen positioned himself as part of the national conservative wing of the party that rejected bothrepublicanism

Republicanism is a political ideology that encompasses a range of ideas from civic virtue, political participation, harms of corruption, positives of mixed constitution, rule of law, and others. Historically, it emphasizes the idea of self ...

and the Weimar Coalition with the Social Democratic Party of Germany

The Social Democratic Party of Germany ( , SPD ) is a social democratic political party in Germany. It is one of the major parties of contemporary Germany. Saskia Esken has been the party's leader since the 2019 leadership election together w ...

(SPD). In reality, Papen's political ideology was much closer to that of the German National People's Party

The German National People's Party (, DNVP) was a national-conservative and German monarchy, monarchist political party in Germany during the Weimar Republic. Before the rise of the Nazi Party, it was the major nationalist party in Weimar German ...

(DNVP) and he seems to have belonged to the Centre Party out of loyalty to the Catholic Church in Germany and in the hope that he could shift his party's platform towards restoring the constitutional monarchy

Constitutional monarchy, also known as limited monarchy, parliamentary monarchy or democratic monarchy, is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in making decisions. ...

deposed in 1918. Despite this ambiguity, Papen was undoubtedly a highly powerful dealmaker within the political party

A political party is an organization that coordinates candidates to compete in a particular area's elections. It is common for the members of a party to hold similar ideas about politics, and parties may promote specific political ideology, ...

, particularly as the largest shareholder and the chief of the editorial board in the party's Catholic newspaper , the most prestigious of the German Catholic media sources at the time.

Papen was a member of the Landtag of Prussia

The Landtag of Prussia () was the representative assembly of the Kingdom of Prussia implemented in 1849, a bicameralism, bicameral legislature consisting of the upper Prussian House of Lords, House of Lords (''Herrenhaus'') and the lower Prussian ...

from 1921 to 1928 and from 1930 to 1932, representing a heavily Catholic constituency in rural Westphalia. However, he rarely attended Landtag sessions and never spoke at them during his elected mandate. He subsequently tried to have his name entered as a candidate for the Centre Party for the Reichstag elections of May 1924, but this was blocked by the party leadership. In February 1925, Papen was one of the six Centre deputies in the Landtag who voted with the German National People's Party and the German People's Party against the SPD-Centre coalition government

A coalition government, or coalition cabinet, is a government by political parties that enter into a power-sharing arrangement of the executive. Coalition governments usually occur when no single party has achieved an absolute majority after an ...

. Papen was nearly expelled from the party for disobeying orders from his party leadership through his votes in the Landtag. In the 1925 presidential elections, Papen surprised his party by supporting the DNVP candidate Paul von Hindenburg

Paul Ludwig Hans Anton von Beneckendorff und von Hindenburg (2 October 1847 – 2 August 1934) was a German military and political leader who led the Imperial German Army during the First World War and later became President of Germany (1919� ...

over the Centre Party's own candidate Wilhelm Marx. Papen, along with two of his future cabinet ministers, was a member of Arthur Moeller van den Bruck's exclusive Berlin (German Gentlemen's Club).

In March 1930, Papen welcomed the coming of presidential government. But with chancellor Heinrich Brüning's presidential government's dependence upon the Social Democrats in the to "tolerate" it by not voting to cancel laws passed under Article 48, Papen grew more critical. In a speech before a group of farmers in October 1931, Papen called for Brüning to disallow the SPD and base his presidential government on "tolerance" from the NSDAP instead. Papen demanded that Brüning transform the "concealed dictatorship" of a presidential government into a dictatorship that would unite all of the German right under its banner. In the March–April 1932 German presidential election

Presidential elections were held in Germany on 13 March 1932, with a runoff on 10 April. Independent incumbent Paul von Hindenburg won a second seven-year term against Adolf Hitler of the Nazi Party (NSDAP). Communist Party of Germany, Communist ...

, Papen voted for Hindenburg on the grounds he was the best man to unite the right, while in the Prussian Landtag's election for the Landtag speaker, Papen voted for the Nazi Hans Kerrl.

Chancellorship

On 1 June 1932, Papen was suddenly promoted to high office when President Hindenburg appointed him

On 1 June 1932, Papen was suddenly promoted to high office when President Hindenburg appointed him chancellor

Chancellor () is a title of various official positions in the governments of many countries. The original chancellors were the of Roman courts of justice—ushers, who sat at the (lattice work screens) of a basilica (court hall), which separa ...

, an appointment he owed to General Kurt von Schleicher, an old friend from the pre-war General Staff, and an influential advisor of President Hindenburg. Schleicher selected Papen because his conservative, aristocratic background and military career made him acceptable to Hindenburg and would create the groundwork for a possible coalition between the Centre Party and the Nazis. It was Schleicher, who himself became Defence Minister, who was responsible for selecting the entire cabinet. The day before, Papen had promised party chairman Ludwig Kaas

Ludwig Kaas (23 May 1881 – 15 April 1952) was a German Roman Catholic priest and politician of the Centre Party during the Weimar Republic. He was instrumental in brokering the Reichskonkordat between the Holy See and the German Reich.

...

he would not accept any appointment. After Papen broke his pledge, Kaas branded him the " Ephialtes of the Centre Party", after the infamous traitor of the Battle of Thermopylae

The Battle of Thermopylae ( ) was fought in 480 BC between the Achaemenid Empire, Achaemenid Persian Empire under Xerxes I and an alliance of Polis, Greek city-states led by Sparta under Leonidas I. Lasting over the course of three days, it wa ...

. On 31 May 1932, in order to forestall being expelled from the party, Papen resigned from it.

The cabinet over which Papen presided was labelled the "cabinet of barons" or "cabinet of monocles". Papen had little support in the Reichstag; the only parties committed to supporting him were the national conservative German National People's Party

The German National People's Party (, DNVP) was a national-conservative and German monarchy, monarchist political party in Germany during the Weimar Republic. Before the rise of the Nazi Party, it was the major nationalist party in Weimar German ...

(DNVP) and the conservative liberal German People's Party (DVP). The Centre Party refused its support for him on account of his betrayal of Chancellor Brüning. Schleicher's planned Centre-Nazi coalition thus failed to materialize, and the Nazis now had little reason to prop up Papen's weak government. Papen grew very close to Hindenburg and first met Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

in June 1932.

Papen consented on 31 May to Hitler's and Hindenburg's agreement of 30 May that the Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party ( or NSDAP), was a far-right politics, far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that created and supported the ideology of Nazism. Its precursor ...

would tolerate Papen's government if fresh elections were called, the ban on the SA cancelled, and the Nazis granted access to the radio network. As agreed, the Papen government dissolved the Reichstag on 4 June and called a national election by 31 July 1932, in the hope that the Nazis would win the largest number of seats in the Reichstag, which would allow him the majority he needed to establish an authoritarian government. In a so-called "presidential government", Papen would rule by Article 48, having emergency decrees signed by President Hindenburg. On 16 June 1932, the new government lifted the ban on the SA and the SS, eliminating the last remaining rationale for Nazi support for Papen.

In June and July 1932, Papen represented Germany at the Lausanne conference where, on 9 July, an agreement was reached for Germany to make a one-time payment of 3 million Reichsmarks in bonds to the Bank for International Settlements

The Bank for International Settlements (BIS) is an international financial institution which is owned by member central banks. Its primary goal is to foster international monetary and financial cooperation while serving as a bank for central bank ...

. The redemption of the bonds, which would not start for at least three years, was to be the last of Germany's reparations payments. Papen nevertheless immediately repudiated the commitment upon his return to Berlin. The treaty signed at the Lausanne Conference was not ratified by any of the countries involved, and Germany never resumed paying reparations after the expiration of the Hoover Moratorium in 1932.

Through Article 48, Papen enacted on 4 September economic policies that cut the payments offered by the unemployment insurance fund, subjected jobless Germans seeking unemployment insurance to a means test, and lowered wages (including those reached by collective bargaining), while arranging tax cuts for corporations and the rich. These austerity policies made Papen deeply unpopular with the general population but had the backing of the business elite.

Negotiations between the Nazis, the Centre Party, and Papen for a new Prussian government began on 8 June but broke down due to the Centre Party's hostility to its deserter Papen. On 11 July 1932 Papen received the support of the cabinet and the President for a decree allowing the national government to take over the Prussian government, which was dominated by the SPD. This move was later justified through the false rumour that the Social Democrats and the Communist Party of Germany

The Communist Party of Germany (, ; KPD ) was a major Far-left politics, far-left political party in the Weimar Republic during the interwar period, German resistance to Nazism, underground resistance movement in Nazi Germany, and minor party ...

(KPD) were planning a merger. The political violence of the so-called Altona Bloody Sunday

Altona Bloody Sunday () is the name given to the events of 17 July 1932 when a recruitment march by the Sturmabteilung, Nazi SA led to violent clashes between the police, the SA and supporters of the Communist Party of Germany (KPD) in Alt ...

clash between Nazis, Communists, and the police on 17 July, gave Papen his pretext. On 20 July, Papen launched a coup against the SPD coalition government of Prussia in the so-called (Prussian Coup). Berlin was put on military lockdown, and Papen informed the members of the Prussian cabinet that they were being removed from office. Papen declared himself Commissioner () of Prussia by way of another emergency decree that he elicited from Hindenburg, further weakening the democracy of the Weimar Republic. Papen viewed the coup as a gift to the Nazis, who had been informed of it by 9 July, and were now supposed to support his government.

On 23 July, Papen instructed German representatives to walk out of the World Disarmament Conference after the French delegation warned that allowing Germany ("equality of status") in armaments would lead to another world war. Papen stated that Germany would not return to the conference until the other powers agreed to consider his demand for equal status.

In the Reichstag election of 31 July the Nazis won the largest number of seats. To combat the rise in SA and SS political terrorism that began right after the elections, Papen on 9 August brought in via Article 48 a new law that drastically streamlined the judicial process in death penalty cases while limiting the right of appeal. New special courts were also created. A few hours later in the town of Potempa, five SA men murdered Communist labourer Konrad Pietrzuch. The "Potempa Five" were promptly arrested, then convicted and sentenced to death on 23 August by a special court. The Potempa case generated enormous media attention, and Hitler made it clear that he would not support Papen's government if the "Five" were executed. On 2 September, Papen in his capacity as Commissioner of Prussia acquiesced to Hitler's demands and commuted the sentences of the "Five" to life imprisonment.

On 11 August, the public holiday of Constitution Day, which commemorated the adoption of the Weimar Constitution in 1919, Papen and his Interior Minister Baron Wilhelm von Gayl called a press conference to announce plans for a new constitution that would, in effect, turn Germany into a dictatorship. Two days later, Schleicher and Papen offered the position of vice-chancellor to Hitler, who rejected it.

When the new Reichstag assembled on 12 September, Papen hoped to destroy the growing alliance between the Nazis and the Centre Party. That day at the President's estate in Neudeck, Papen, Schleicher, and Gayl obtained in advance from Hindenburg a decree to dissolve the Reichstag, then secured another decree to suspend elections beyond the constitutional 60 days. The Communists tabled a motion of no confidence

A motion or vote of no confidence (or the inverse, a motion or vote of confidence) is a motion and corresponding vote thereon in a deliberative assembly (usually a legislative body) as to whether an officer (typically an executive) is deemed fi ...

in the Papen government. Papen had anticipated this move by the Communists, but had been assured that there would be an immediate objection. However, when no one objected, Papen placed the red folder containing the dissolution decree on Reichstag president Hermann Göring

Hermann Wilhelm Göring (or Goering; ; 12 January 1893 – 15 October 1946) was a German Nazism, Nazi politician, aviator, military leader, and convicted war criminal. He was one of the most powerful figures in the Nazi Party, which gov ...

's desk. He demanded the floor in order to read it, but Göring pretended not to see him; the Nazis and the Centre Party had decided to support the Communist motion. The motion carried by 512 votes to 42. Realizing that he did not have nearly enough support to go through with his plan to suspend elections, Papen decided to call another election to punish the Reichstag for the vote of no-confidence.

On 27 October, the Supreme Court of Germany issued a ruling that Papen's coup deposing the Prussian government was illegal, but allowed Papen to retain control of Prussia. In November 1932, Papen violated the terms of the Treaty of Versailles by approving a program of refurbishment for the German Navy of an aircraft carrier, six battleships, six cruisers, six destroyer flotillas, and 16 submarines, intended to allow Germany to control both the North Sea and the Baltic.

In the November 1932 election, the Nazis lost seats, but Papen was still unable to secure a Reichstag that could be counted on not to pass another vote of no-confidence in his government. Papen's attempt to negotiate with Hitler failed. Under pressure from Schleicher, Papen resigned on 17 November and formed a caretaker government. He told his cabinet that he planned to have martial law declared, which would allow him to rule as a dictator. However, at a cabinet meeting on 2 December, Papen was informed by Schleicher's associate General Eugen Ott about the dubious results of ''

On 27 October, the Supreme Court of Germany issued a ruling that Papen's coup deposing the Prussian government was illegal, but allowed Papen to retain control of Prussia. In November 1932, Papen violated the terms of the Treaty of Versailles by approving a program of refurbishment for the German Navy of an aircraft carrier, six battleships, six cruisers, six destroyer flotillas, and 16 submarines, intended to allow Germany to control both the North Sea and the Baltic.

In the November 1932 election, the Nazis lost seats, but Papen was still unable to secure a Reichstag that could be counted on not to pass another vote of no-confidence in his government. Papen's attempt to negotiate with Hitler failed. Under pressure from Schleicher, Papen resigned on 17 November and formed a caretaker government. He told his cabinet that he planned to have martial law declared, which would allow him to rule as a dictator. However, at a cabinet meeting on 2 December, Papen was informed by Schleicher's associate General Eugen Ott about the dubious results of ''Reichswehr

''Reichswehr'' (; ) was the official name of the German armed forces during the Weimar Republic and the first two years of Nazi Germany. After Germany was defeated in World War I, the Imperial German Army () was dissolved in order to be reshaped ...

'' war games, that showed there was no way to maintain order against the Nazis and Communists. Realizing that Schleicher was moving to replace him, Papen asked Hindenburg to dismiss Schleicher as Defence Minister. Instead, Hindenburg appointed Schleicher as chancellor.

Bringing Hitler to power

After his resignation, Papen regularly visited Hindenburg, missing no opportunity to attack Schleicher in these visits. Schleicher had promised Hindenburg that he would never attack Papen in public when he became chancellor, but in a bid to distance himself from the very unpopular Papen, Schleicher in a series of speeches in December 1932 – January 1933 did just that, upsetting Hindenburg. Papen was embittered by the way his former best friend, Schleicher, had brought him down, and was determined to become chancellor again. On 4 January 1933, Hitler and Papen met in secret at the banker Kurt Baron von Schröder's house in Cologne to discuss a common strategy against Schleicher. On 9 January 1933, Papen and Hindenburg agreed to form a new government that would bring in Hitler. On the evening of 22 January in a meeting at the villa ofJoachim von Ribbentrop

Ulrich Friedrich-Wilhelm Joachim von Ribbentrop (; 30 April 1893 – 16 October 1946) was a German Nazi politician and diplomat who served as Minister for Foreign Affairs (Germany), Minister of Foreign Affairs of Nazi Germany from 1938 to 1945. ...

in Berlin, Papen made the concession of abandoning his claim to the chancellorship and committed to support Hitler as chancellor in a proposed "Government of National Concentration", in which Papen would serve as vice-chancellor

A vice-chancellor (commonly called a VC) serves as the chief executive of a university in the United Kingdom, New Zealand, Australia, Nepal, India, Bangladesh, Malaysia, Nigeria, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, South Africa, Kenya, other Commonwealth of Nati ...

and Minister-President of Prussia. On 23 January, Papen presented to Hindenburg his idea for Hitler to be made chancellor, while keeping him "boxed" in. On the same day Schleicher, to avoid a vote of no-confidence in the Reichstag when it reconvened on 31 January, asked the president to declare a state of emergency. Hindenburg declined and Schleicher resigned at midday on 28 January. Hindenburg formally gave Papen the task of forming a new government.

In the morning of 29 January, Papen met with Hitler and Hermann Göring at his apartment, where it was agreed that Papen would serve as vice-chancellor and Commissioner for Prussia. It was in the same meeting that Papen first learned that Hitler wanted to dissolve the Reichstag when he became chancellor and, once the Nazis had won a majority of the seats in the ensuing elections, to activate the Enabling Act in order to be able to enact laws without the involvement of the Reichstag. When the people around Papen voiced their concerns about putting Hitler in power, he asked them, "What do you want?" and reassured them, "I have the confidence of Hindenburg! In two months, we'll have pushed Hitler so far into the corner that he'll squeal."

Editor-in-Chief Theodor Wolff commented in an editorial in the '' Berliner Tagblatt'' on January 29, 1933: "The strongest natures, those with the iron forehead or the board before the head, will insist on the anti-parliamentary solution, on the closing of the Reichstag House, on the coup d'état

A coup d'état (; ; ), or simply a coup

, is typically an illegal and overt attempt by a military organization or other government elites to unseat an incumbent leadership. A self-coup is said to take place when a leader, having come to powe ...

."

In the end, the president, who had previously vowed never to let Hitler become chancellor, appointed Hitler to the post at 11:30 am on 30 January 1933, with Papen as vice-chancellor. While Papen's intrigues appeared to have brought Hitler into power, the crucial dynamic was in fact provided by the Nazi Party's electoral support, which made military dictatorship the only alternative to Nazi rule for Hindenburg and his circle.

At the formation of Hitler's cabinet on 30 January, only three Nazis held cabinet portfolios: Hitler, Göring, and Wilhelm Frick. The other eight posts were held by conservatives close to Papen, including the DNVP chairman, Alfred Hugenberg

Alfred Ernst Christian Alexander Hugenberg (19 June 1865 – 12 March 1951) was an influential German businessman and politician. An important figure in nationalist politics in Germany during the first three decades of the twentieth century, ...

. Additionally, as part of the deal that allowed Hitler to become chancellor, Papen was granted the right to attend every meeting between Hitler and Hindenburg. Moreover, cabinet decisions were made by majority vote. Papen naively believed that his conservative friends' majority in the cabinet and his closeness to Hindenburg would keep Hitler in check.

Vice-chancellor

Hitler and his allies instead quickly marginalised Papen and the rest of the cabinet. For example, as part of the deal between Hitler and Papen, Göring had been appointed interior minister of Prussia, thus putting the largest police force in Germany under Nazi control. Göring frequently acted without consulting his nominal superior, Papen. On 1 February 1933, Hitler presented to the cabinet an Article 48 decree law that had been drafted by Papen in November 1932 allowing the police to take people into "protective custody" without charges. It was signed into law by Hindenburg on 4 February as the "Decree for the Protection of the German People". On the evening of 27 February 1933, Papen joined Hitler, Göring and Goebbels at the burning Reichstag and told him that he shared their belief that this was the signal for Communist revolution. On 18 March 1933, in his capacity as ''Reich'' Commissioner for Prussia, Papen freed the " Potempa Five" under the grounds the murder of Konrad Pietzuch was an act of self-defense, making the five SA men "innocent victims" of a miscarriage of justice. Neither Papen nor his conservative allies waged a fight against theReichstag Fire Decree

The Reichstag Fire Decree () is the common name of the Decree of the Reich President for the Protection of People and State () issued by German President Paul von Hindenburg on the advice of Chancellor Adolf Hitler on 28 February 1933 in immed ...

in late February or the Enabling Act in March. After the Enabling Act was passed, serious deliberations more or less ceased at cabinet meetings when they took place at all, which subsequently neutralised Papen's attempt to "box" Hitler in through cabinet-based decision-making.

At the Reichstag election of 5 March 1933, Papen was elected as a deputy in an electoral alliance with Hugenberg's DNVP. Papen endorsed Hitler's plan, presented at a cabinet meeting on 7 March 1933, to destroy the Centre Party by severing the Catholic Church from it. This was the origin of the that Papen was to negotiate with the Catholic Church later in the spring of 1933. On 5 April 1933, Papen founded a new political party called the League of German Catholics Cross and Eagle, which was intended as a conservative Catholic party that would hold the NSDAP in check while at the same time working with the NSDAP. Both the Centre Party and the Bavarian People's Party declined to merge into Papen's new party while the rival Coalition of Catholic Germans, which was sponsored by the NSDAP, proved more effective at recruiting German Catholics.

On 8 April Papen travelled to the Vatican

Vatican may refer to:

Geography

* Vatican City, an independent city-state surrounded by Rome, Italy

* Vatican Hill, in Rome, namesake of Vatican City

* Ager Vaticanus, an alluvial plain in Rome

* Vatican, an unincorporated community in the ...

to offer a that defined the German state's relationship with the Catholic Church. During his stay in Rome, Papen met the Italian Prime Minister Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who, upon assuming office as Prime Minister of Italy, Prime Minister, became the dictator of Fascist Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 un ...

and failed to persuade him to drop his support for the Austrian chancellor Dollfuss. Papen was euphoric at the that he negotiated with Cardinal Eugenio Pacelli in Rome, believing that this was a diplomatic success that restored his status in Germany, guaranteed the rights of German Catholics in the Third Reich, and required the disbandment of the Centre Party and the Bavarian People's Party, thereby achieving one of Papen's main political goals since June 1932. During Papen's absence, the ''Landtag'' of Prussia elected Göring as prime minister on 10 April. Papen saw the end of the Centre Party that he had engineered as one of his greatest achievements. Later in May 1933, he was forced to disband the League of German Catholics Cross and Eagle owing to lack of public interest.

In September 1933, Papen visited Budapest to meet the Hungarian Prime Minister Gyula Gömbös, and to discuss how Germany and Hungary might best co-operate against Czechoslovakia. The Hungarians wanted the ''volksdeutsche'' (ethnic German) minorities in the Banat, Transylvania, Slovakia and Carpathia to agitate to return to Hungary in co-operation with the Magyar minorities, a demand that Papen refused to meet. In September 1933, when the Soviet Union ended its secret military co-operation with Germany, the Soviets justified their move under the grounds that Papen had informed the French of the Soviet support for German violations of the Versailles Treaty.

On 3 October 1933, Papen was named a member of the Academy for German Law

The Academy for German Law () was an institute for legal research and reform founded on 26 June 1933 in Nazi Germany. After suspending its operations during the Second World War in August 1944, it was abolished after the fall of the Nazi regime on ...

at its inaugural meeting. Then, on 14 November 1933, Papen was appointed the ''Reich'' Commissioner for the Saar. The Saarland

Saarland (, ; ) is a state of Germany in the southwest of the country. With an area of and population of 990,509 in 2018, it is the smallest German state in area apart from the city-states of Berlin, Bremen, and Hamburg, and the smallest in ...

was under the rule of the League of Nations and a referendum was scheduled for 1935 under which the Saarlanders had the option to return to Germany, join France, or retain the status quo. As a conservative Catholic whose wife was from the Saarland, Papen had much understanding of the heavily Catholic region, and he gave numerous speeches urging the Saarlanders to vote to return to Germany. Papen was successful in persuading the majority of the Catholic clergy in the Saarland to campaign for a return to Germany, and 90% of the Saarland voted to return to Germany in the 1935 referendum.

Papen began covert talks with other conservative forces with the aim of convincing Hindenburg to restore the balance of power back to the conservatives. By May 1934, it had become clear that Hindenburg was dying, with doctors telling Papen that the president only had a few months left to live. Papen together with Otto Meissner, Hindenburg's chief of staff, and Major Oskar von Hindenburg, Hindenburg's son, drafted a "political will and last testament", which the president signed on 11 May 1934. At Papen's request, the will called for the dismissal of certain Nazi ministers from the cabinet, and regular cabinet meetings, which would have achieved Papen's plan of January 1933 for a broad governing coalition of the right.

The Marburg speech

With the Army command recently having hinted at the need for Hitler to control the SA, Papen delivered anaddress

An address is a collection of information, presented in a mostly fixed format, used to give the location of a building, apartment, or other structure or a plot of land, generally using border, political boundaries and street names as references, ...

at the University of Marburg

The Philipps University of Marburg () is a public research university located in Marburg, Germany. It was founded in 1527 by Philip I, Landgrave of Hesse, which makes it one of Germany's oldest universities and the oldest still operating Prote ...

on 17 June 1934 where he called for the restoration of some freedoms, demanded an end to the calls for a "second revolution" and advocated the cessation of SA terror in the streets. Papen intended to "tame" Hitler with the Marburg speech, and gave the speech without any effort at co-ordination beforehand with either Hindenburg or the . The speech was crafted by Papen's speech writer, Edgar Julius Jung, with the assistance of Papen's secretary Herbert von Bose and Catholic leader Erich Klausener, and Papen had first seen the text of the speech only two hours before he delivered it at the University of Marburg. The "Marburg speech" was well received by the graduating students of Marburg university who all loudly cheered the vice-chancellor. Extracts were reproduced in the , the most prestigious newspaper in Germany, and from there picked up by the foreign press.

The speech incensed Hitler, and its publication was suppressed by the Propaganda Ministry. Papen told Hitler that unless the ban on the Marburg speech was lifted and Hitler declared himself willing to follow the line recommended by Papen in the speech, he would resign and would inform Hindenburg why he had resigned. Hitler outwitted Papen by telling him that he agreed with all of the criticism of his regime made in the Marburg speech; told him Goebbels was wrong to ban the speech and he would have the ban lifted at once; and promised that the SA would be put in their place, provided Papen agreed not to resign and would meet with Hindenburg in a joint interview with him. Papen accepted Hitler's suggestions.

Night of the Long Knives

Two weeks after the Marburg speech, Hitler responded to the armed forces' demands to suppress the ambitions of Ernst Röhm and the SA by purging the SA leadership. The purge, known as the Night of the Long Knives, took place between 30 June and 2 July 1934. Though Papen's bold speech against some of the excesses committed by the Nazis had angered Hitler, the latter was aware that he could not act directly against the vice-chancellor without offending Hindenburg. Instead, in the Night of the Long Knives, the Vice-Chancellery, Papen's office, was ransacked by the (SS); his associates Herbert von Bose, Erich Klausener and Edgar Julius Jung were shot. Papen himself was placed under house arrest at his villa with his telephone line cut. Some accounts indicate that this "protective custody" was ordered by Göring, who felt the ex-diplomat could be useful in the future. Reportedly Papen arrived at the Chancellery, exhausted from days of house arrest without sleep, to find the chancellor seated with other Nazi ministers around a round table, with no place for Papen but a hole in the middle. He insisted on a private audience with Hitler and announced his resignation, stating, "My service to the Fatherland is over!" The following day, Papen's resignation as vice-chancellor was formally accepted and publicised, with no successor appointed. When Hindenburg died on 2 August, the last conservative obstacle to complete Nazi rule was gone.Ambassador to Austria

Hitler offered Papen the assignment of German ambassador to

Hitler offered Papen the assignment of German ambassador to Vienna

Vienna ( ; ; ) is the capital city, capital, List of largest cities in Austria, most populous city, and one of Federal states of Austria, nine federal states of Austria. It is Austria's primate city, with just over two million inhabitants. ...

, which Papen accepted. Papen was a German nationalist who always believed that Austria was destined to join Germany in an ''Anschluss

The (, or , ), also known as the (, ), was the annexation of the Federal State of Austria into Nazi Germany on 12 March 1938.

The idea of an (a united Austria and Germany that would form a "German Question, Greater Germany") arose after t ...

'' (annexation

Annexation, in international law, is the forcible acquisition and assertion of legal title over one state's territory by another state, usually following military occupation of the territory. In current international law, it is generally held t ...

), and felt that a success in bringing that about might restore his career. During his time as ambassador to Austria, Papen stood outside the normal chain of command of the '' Auswärtiges Amt'' (Foreign Office) as he refused to take orders from Konstantin von Neurath

Konstantin Hermann Karl Freiherr von Neurath (2 February 1873 – 14 August 1956) was a German politician, diplomat and convicted Nazi war criminal who served as Foreign Minister of Germany between 1932 and 1938.

Born to a Swabian noble famil ...

, his own former Foreign Minister. Instead, Papen reported directly to Hitler.

Papen met often with Austrian Chancellor Kurt von Schuschnigg to assure him that Germany did not wish to annex his country, and only wanted the banned Austrian Nazi Party to participate in Austrian politics. In late 1934-early 1935, Papen took a break from his duties as German ambassador in Vienna to lead the ''Deutsche Front'' ("German Front") in the Saarland plebiscite on 13 January 1935, where the League of Nations observers monitoring the vote noted Papen's "ruthless methods" as he campaigned for the region to return to Germany.

Papen also contributed to achieving Hitler's goal of undermining Austrian sovereignty and bringing about the ''Anschluss''. On 28 August 1935, Papen negotiated a deal under which the German press would cease its attacks on the Austrian government, in return for which the Austrian press would cease its attacks on Germany's. Papen played a major role in negotiating the 1936 Austro-German agreement under which Austria declared itself a "German state" whose foreign policy would always be aligned with Berlin's and allowed for members of the "national opposition" to enter the Austrian cabinet in exchange for which the Austrian Nazis abandoned their terrorist campaign against the government. The treaty Papen signed in Vienna on 11 July 1936 promised that Germany would not seek to annex Austria and largely placed Austria in the German sphere of influence, greatly reducing Italian influence on Austria. In July 1936, Papen reported to Hitler that the Austro-German treaty he had just signed was the "decisive step" towards ending Austrian independence, and it was only a matter of time before the ''Anschluss'' took place.

In the summer and fall of 1937, Papen pressured the Austrians to include more Nazis in the government. In September 1937, Papen returned to Berlin when

Papen also contributed to achieving Hitler's goal of undermining Austrian sovereignty and bringing about the ''Anschluss''. On 28 August 1935, Papen negotiated a deal under which the German press would cease its attacks on the Austrian government, in return for which the Austrian press would cease its attacks on Germany's. Papen played a major role in negotiating the 1936 Austro-German agreement under which Austria declared itself a "German state" whose foreign policy would always be aligned with Berlin's and allowed for members of the "national opposition" to enter the Austrian cabinet in exchange for which the Austrian Nazis abandoned their terrorist campaign against the government. The treaty Papen signed in Vienna on 11 July 1936 promised that Germany would not seek to annex Austria and largely placed Austria in the German sphere of influence, greatly reducing Italian influence on Austria. In July 1936, Papen reported to Hitler that the Austro-German treaty he had just signed was the "decisive step" towards ending Austrian independence, and it was only a matter of time before the ''Anschluss'' took place.

In the summer and fall of 1937, Papen pressured the Austrians to include more Nazis in the government. In September 1937, Papen returned to Berlin when Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who, upon assuming office as Prime Minister of Italy, Prime Minister, became the dictator of Fascist Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 un ...

visited Germany, serving as Hitler's adviser on Italo-German talks about Austria. Papen joined the Nazi Party in 1938. Papen was dismissed from his mission in Austria on 4 February 1938, but Hitler drafted him to arrange a meeting between the German dictator and Schuschnigg at Berchtesgaden

Berchtesgaden () is a municipality in the district Berchtesgadener Land, Bavaria, in southeastern Germany, near the border with Austria, south of Salzburg and southeast of Munich. It lies in the Berchtesgaden Alps. South of the town, the Be ...

. The ultimatum that Hitler presented to Schuschnigg at the meeting on 12 February 1938 led to the Austrian government's capitulation to German threats and pressure, and paved the way for the Anschluss

The (, or , ), also known as the (, ), was the annexation of the Federal State of Austria into Nazi Germany on 12 March 1938.

The idea of an (a united Austria and Germany that would form a "German Question, Greater Germany") arose after t ...

that year.

Ambassador to Turkey

Papen later served the German government as Ambassador to Turkey from 1939 to 1944. In April 1938, after the retirement of the previous ambassador, Friedrich von Keller on his 65th birthday, the German foreign ministerJoachim von Ribbentrop

Ulrich Friedrich-Wilhelm Joachim von Ribbentrop (; 30 April 1893 – 16 October 1946) was a German Nazi politician and diplomat who served as Minister for Foreign Affairs (Germany), Minister of Foreign Affairs of Nazi Germany from 1938 to 1945. ...

attempted to appoint Papen as ambassador in Ankara, but the appointment was vetoed by the Turkish president Mustafa Kemal Atatürk

Mustafa Kemal Atatürk ( 1881 – 10 November 1938) was a Turkish field marshal and revolutionary statesman who was the founding father of the Republic of Turkey, serving as its first President of Turkey, president from 1923 until Death an ...

who remembered Papen well with considerable distaste when he had served alongside him in World War I. In November 1938 and in February 1939, the new Turkish president General İsmet İnönü again vetoed Ribbentrop's attempts to have Papen appointed as German ambassador to Turkey. In April 1939, Turkey accepted Papen as ambassador. Papen was keen to return to Turkey, where he had served during World War I.

Papen arrived in Turkey on 27 April 1939, just after the signing of a UK-Turkish declaration of friendship. İnönü wanted Turkey to join the UK-inspired "peace front" that was meant to stop Germany. On 24 June 1939, France and Turkey signed a declaration committing them to upholding collective security in the Balkans. On 21 August 1939, Papen presented Turkey with a diplomatic note threatening economic sanctions and the cancellation of all arms contracts if Turkey did not cease leaning towards joining the UK-French "peace front", a threat that Turkey rebuffed.

On 1 September 1939, Germany invaded Poland, and two days later on 3 September 1939 the UK and France declared war on Germany. Papen claimed later to have been opposed to Hitler's foreign policy in 1939, and was very depressed when he heard the news of the German attack on Poland on the radio. Papen continued his work of representing the ''Reich'' in Turkey under the grounds that resigning in protest "would indicate the moral weakening in Germany", which was something he could never do.

On 19 October 1939, Papen suffered a notable setback when Turkey signed a treaty of alliance with France and the UK. During the Phoney War

The Phoney War (; ; ) was an eight-month period at the outset of World War II during which there were virtually no Allied military land operations on the Western Front from roughly September 1939 to May 1940. World War II began on 3 Septembe ...

, the conservative Catholic Papen found himself to his own discomfort working together with Soviet diplomats in Ankara to pressure Turkey not to enter the war on the Allied side. In June 1940, with France's defeat, İnönü abandoned his pro-Allied neutrality, and Papen's influence in Ankara dramatically increased.

Between 1940 and 1942 Papen signed three economic agreements that placed Turkey in the German economic sphere of influence. Papen hinted more than once to Turkey that Germany was prepared to support Bulgarian claims to Thrace if Turkey did not prove more accommodating to Germany. In May 1941, when the Germans dispatched an expeditionary force to Iraq to fight against the UK in the Anglo-Iraqi War

The Anglo-Iraqi War was a British-led Allies of World War II, Allied military campaign during the Second World War against the Kingdom of Iraq, then ruled by Rashid Ali al-Gaylani who had seized power in the 1941 Iraqi coup d'état with assista ...