The Franco-Ottoman alliance, also known as the Franco-Turkish alliance, was an alliance established in 1536 between

Francis I,

King of France

France was ruled by monarchs from the establishment of the kingdom of West Francia in 843 until the end of the Second French Empire in 1870, with several interruptions.

Classical French historiography usually regards Clovis I, king of the Fra ...

and

Suleiman I of the Ottoman Empire. The strategic and sometimes tactical alliance was one of the longest-lasting and most important

foreign alliances of France

The foreign alliances of France have a long and complex history spanning more than a millennium. One traditional characteristic of the French diplomacy of alliances has been the ''"Alliance de revers"'' (i.e. "Rear alliance"), aiming at allying w ...

, and was particularly influential during the

Italian Wars

The Italian Wars were a series of conflicts fought between 1494 and 1559, mostly in the Italian Peninsula, but later expanding into Flanders, the Rhineland and Mediterranean Sea. The primary belligerents were the House of Valois, Valois kings o ...

. The Franco-Ottoman military alliance reached its peak with the

Invasion of Corsica of 1553 during the reign of

Henry II of France

Henry II (; 31 March 1519 – 10 July 1559) was List of French monarchs#House of Valois-Angoulême (1515–1589), King of France from 1547 until his death in 1559. The second son of Francis I of France, Francis I and Claude of France, Claude, Du ...

.

As the first non-ideological alliance in effect between a Christian and Muslim state, the alliance attracted heavy controversy for its time and caused a scandal throughout Christendom.

Carl Jacob Burckhardt

Carl Jacob Burckhardt (September 10, 1891 – March 3, 1974) was a Swiss diplomat and historian. His career alternated between periods of academic historical research and diplomatic postings; the most prominent of the latter were League of Natio ...

(1947) called it "the

sacrilegious

Sacrilege is the violation or injurious treatment of a sacred object, site or person. This can take the form of irreverence to sacred persons, places, and things. When the sacrilegious offence is verbal, it is called blasphemy, and when physical ...

union of the

lily

''Lilium'' ( ) is a genus of herbaceous flowering plants growing from bulbs, all with large and often prominent flowers. Lilies are a group of flowering plants which are important in culture and literature in much of the world. Most species are ...

and the

crescent

A crescent shape (, ) is a symbol or emblem used to represent the lunar phase (as it appears in the northern hemisphere) in the first quarter (the "sickle moon"), or by extension a symbol representing the Moon itself.

In Hindu iconography, Hind ...

". It lasted intermittently for more than two and a half centuries,

[Merriman, p.132] until the

Napoleonic campaign in

Ottoman Egypt

Ottoman Egypt was an administrative division of the Ottoman Empire after the conquest of Mamluk Egypt by the Ottomans in 1517. The Ottomans administered Egypt as a province (''eyalet'') of their empire (). It remained formally an Ottoman prov ...

, in 1798–1801.

Background

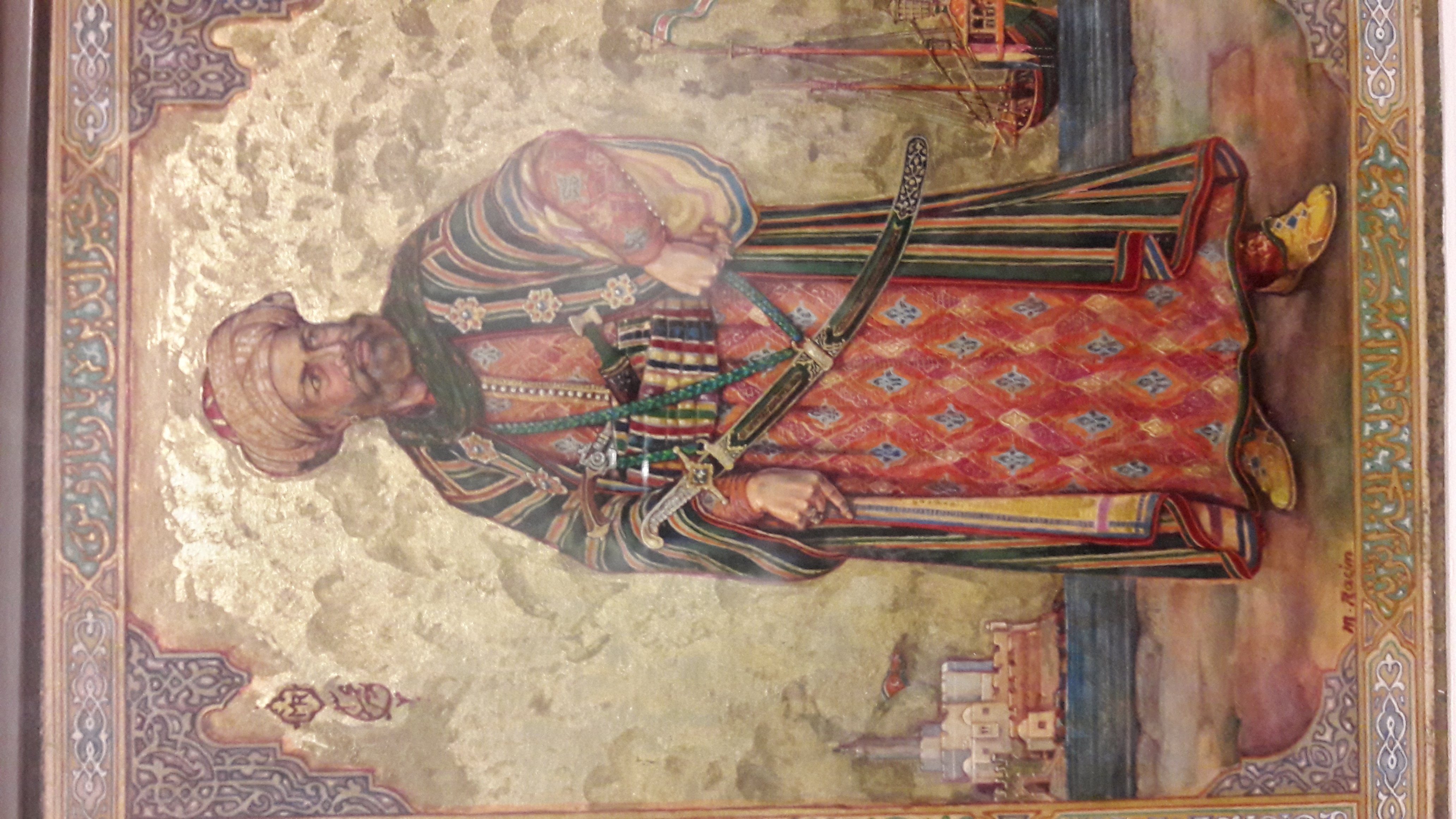

Following the Turkish conquest of

Constantinople

Constantinople (#Names of Constantinople, see other names) was a historical city located on the Bosporus that served as the capital of the Roman Empire, Roman, Byzantine Empire, Byzantine, Latin Empire, Latin, and Ottoman Empire, Ottoman empire ...

in 1453 by

Mehmed II

Mehmed II (; , ; 30 March 14323 May 1481), commonly known as Mehmed the Conqueror (; ), was twice the sultan of the Ottoman Empire from August 1444 to September 1446 and then later from February 1451 to May 1481.

In Mehmed II's first reign, ...

and the unification of swaths of the

Middle East

The Middle East (term originally coined in English language) is a geopolitical region encompassing the Arabian Peninsula, the Levant, Turkey, Egypt, Iran, and Iraq.

The term came into widespread usage by the United Kingdom and western Eur ...

under

Selim I

Selim I (; ; 10 October 1470 – 22 September 1520), known as Selim the Grim or Selim the Resolute (), was the List of sultans of the Ottoman Empire, sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1512 to 1520. Despite lasting only eight years, his reign is ...

,

Suleiman I, the son of Selim, managed to expand Ottoman rule to

Serbia

, image_flag = Flag of Serbia.svg

, national_motto =

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Serbia.svg

, national_anthem = ()

, image_map =

, map_caption = Location of Serbia (gree ...

in 1522. The

Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire, also known as the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation after 1512, was a polity in Central and Western Europe, usually headed by the Holy Roman Emperor. It developed in the Early Middle Ages, and lasted for a millennium ...

thus entered in direct conflict with the Ottomans.

Some early contacts seem to have taken place between the Ottomans and the French.

Philippe de Commines

Philippe de Commines (or de Commynes or "Philippe de Comines"; Latin: ''Philippus Cominaeus''; 1447 – 18 October 1511) was a writer and diplomat in the courts of Burgundy and France. He has been called "the first truly modern writer" (Charles ...

reports that

Bayezid II

Bayezid II (; ; 3 December 1447 – 26 May 1512) was the sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1481 to 1512. During his reign, Bayezid consolidated the Ottoman Empire, thwarted a pro-Safavid dynasty, Safavid rebellion and finally abdicated his throne ...

sent an embassy to

Louis XI

Louis XI (3 July 1423 – 30 August 1483), called "Louis the Prudent" (), was King of France from 1461 to 1483. He succeeded his father, Charles VII. Louis entered into open rebellion against his father in a short-lived revolt known as the ...

in 1483, while

Cem

Cem Sultan (1459–1495) was a prince of the Ottoman Empire.

Cem or CEM may also refer to:

Colleges

* College of Eastern Medicine, a branch of Southern California University of Health Sciences, in Los Angeles, California, US

* College of Eme ...

, his brother and rival pretender to the Ottoman throne was being detained in France at

Bourganeuf

Bourganeuf (; Limousin: ''Borgon Nuòu'') is a commune in the Creuse department in the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region in central France.

Geography

An area of farming and forestry, comprising the village and several hamlets situated in the valley o ...

by

Pierre d'Aubusson

Pierre d'Aubusson (1423 – 3 July 1503) was a List of Grand Masters of the Knights Hospitaller, Grand Master of the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem, and a zealous opponent of the Ottoman Empire.

Pierre probably joined the Knights of Saint John ...

. Louis XI refused to see the envoys, but a large amount of money and Christian relics were offered by the envoy so that Cem could remain in custody in France. Cem was transferred to the custody of

Pope Innocent VIII

Pope Innocent VIII (; ; 1432 – 25 July 1492), born Giovanni Battista Cybo (or Cibo), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 29 August 1484 to his death, in July 1492. Son of the viceroy of Naples, Cybo spent his ea ...

in 1489.

France had signed a first treaty or ''

Capitulation'' with the

Mamluk Sultanate

The Mamluk Sultanate (), also known as Mamluk Egypt or the Mamluk Empire, was a state that ruled Egypt, the Levant and the Hejaz from the mid-13th to early 16th centuries, with Cairo as its capital. It was ruled by a military caste of mamluks ...

of

Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

in 1500, during the reigns of

Louis XII

Louis XII (27 June 14621 January 1515), also known as Louis of Orléans was King of France from 1498 to 1515 and King of Naples (as Louis III) from 1501 to 1504. The son of Charles, Duke of Orléans, and Marie of Cleves, he succeeded his second ...

and Sultan

Bayezid II

Bayezid II (; ; 3 December 1447 – 26 May 1512) was the sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1481 to 1512. During his reign, Bayezid consolidated the Ottoman Empire, thwarted a pro-Safavid dynasty, Safavid rebellion and finally abdicated his throne ...

, in which the Sultan of Egypt had made concessions to the French and the Catalans, and which would be later extended by Suleiman.

France had already been looking for allies in Central Europe. The ambassador of France

Antonio Rincon was employed by

Francis I on several missions to

Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It extends from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Sudetes and Carpathian Mountains in the south, bordered by Lithuania and Russia to the northeast, Belarus and Ukrai ...

and

Hungary

Hungary is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning much of the Pannonian Basin, Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia and ...

between 1522 and 1525. At that time, following the 1522

Battle of Bicoque, Francis I was attempting to ally with king

Sigismund I the Old

Sigismund I the Old (, ; 1 January 1467 – 1 April 1548) was List of Polish monarchs, King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania from 1506 until his death in 1548. Sigismund I was a member of the Jagiellonian dynasty, the son of Casimir IV of P ...

of Poland. Finally, in 1524, a

Franco-Polish alliance

The Franco-Polish Alliance was the military alliance between Poland and France that was active between the early 1920s and the outbreak of the Second World War. The initial agreements were signed in February 1921 and formally took effect in 1923 ...

was signed between Francis I and the king of Poland

Sigismund I.

A momentous intensification of the search for allies in

Central Europe

Central Europe is a geographical region of Europe between Eastern Europe, Eastern, Southern Europe, Southern, Western Europe, Western and Northern Europe, Northern Europe. Central Europe is known for its cultural diversity; however, countries in ...

occurred when the French ruler Francis I was defeated at the

Battle of Pavia

The Battle of Pavia, fought on the morning of 24 February 1525, was the decisive engagement of the Italian War of 1521–1526 between the Kingdom of France and the Habsburg Empire of Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V, Holy Roman Empero ...

on February 24, 1525, by the troops of Emperor

Charles V Charles V may refer to:

Kings and Emperors

* Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor (1500–1558)

* Charles V of Naples (1661–1700), better known as Charles II of Spain

* Charles V of France (1338–1380), called the Wise

Others

* Charles V, Duke ...

. After several months in prison, Francis I was forced to sign the humiliating

Treaty of Madrid, through which he had to relinquish the

Duchy of Burgundy

The Duchy of Burgundy (; ; ) was a medieval and early modern feudal polity in north-western regions of historical Burgundy. It was a duchy, ruled by dukes of Burgundy. The Duchy belonged to the Kingdom of France, and was initially bordering th ...

and the

Charolais to the Empire, renounce his Italian ambitions, and return his belongings and honours to the traitor

Constable de Bourbon. This situation forced Francis I to find an ally against the powerful Habsburg Emperor, in the person of Suleiman the Magnificent.

Alliance of Francis I and Suleiman

The alliance was an opportunity for both rulers to fight against the hegemony of the

House of Habsburg

The House of Habsburg (; ), also known as the House of Austria, was one of the most powerful Dynasty, dynasties in the history of Europe and Western civilization. They were best known for their inbreeding and for ruling vast realms throughout ...

. The objective for Francis I was to find an ally against the Habsburgs,

although the policy of courting a

Muslim

Muslims () are people who adhere to Islam, a Monotheism, monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God ...

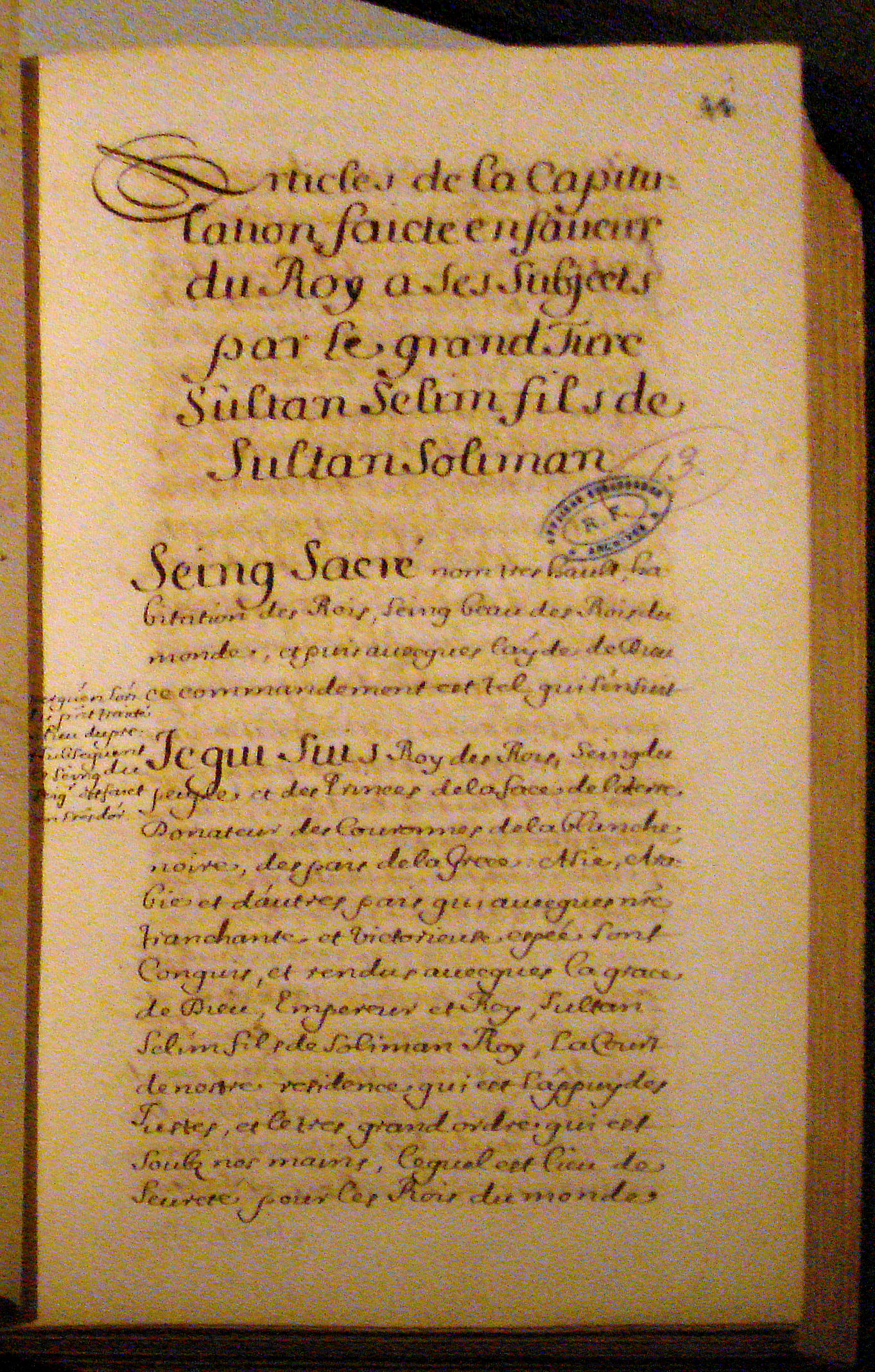

power was in reversal of that of his predecessors. The pretext used by Francis I was the protection of the Christians in Ottoman lands, through agreements called "

Capitulations of the Ottoman Empire

Capitulations of the Ottoman Empire were contracts between the Ottoman Empire and several other Christian powers, particularly France. Turkish capitulations, or Ahidnâmes were generally bilateral acts whereby definite arrangements were enter ...

".

King Francis was imprisoned in

Madrid

Madrid ( ; ) is the capital and List of largest cities in Spain, most populous municipality of Spain. It has almost 3.5 million inhabitants and a Madrid metropolitan area, metropolitan area population of approximately 7 million. It i ...

when the first efforts at establishing an alliance were made. A first French mission to Suleiman seems to have been sent right after the Battle of Pavia by the mother of Francis I,

Louise de Savoie

Louise of Savoy (11 September 1476 – 22 September 1531) was a French noble and regent, Duchess ''suo jure'' of Auvergne and Bourbon, Duchess of Nemours and the mother of King Francis I and Marguerite of Navarre. She was politically active and ...

, but the mission was lost on its way in

Bosnia

Bosnia and Herzegovina, sometimes known as Bosnia-Herzegovina and informally as Bosnia, is a country in Southeast Europe. Situated on the Balkans, Balkan Peninsula, it borders Serbia to the east, Montenegro to the southeast, and Croatia to th ...

.

[Merriman, p.129] In December 1525 a second mission was sent, led by

John Frangipani

The Croat noble called by the French Jean Frangipani was sent by the agents of Francis I of France as ambassador to the Sublime Porte, following the Battle of Pavia (February 1525) which had been a disaster for the French. With the King of France i ...

, which managed to reach Constantinople, the Ottoman capital, with secret letters asking for the deliverance of king Francis I and an attack on the Habsburg. Frangipani returned with an answer from Suleiman, on 6 February 1526:

The plea of the French king nicely corresponded to the ambitions of Suleiman in Europe, and gave him an incentive to attack

Hungary

Hungary is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning much of the Pannonian Basin, Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia and ...

in 1526, leading to the

Battle of Mohács

The Battle of Mohács (; , ) took place on 29 August 1526 near Mohács, in the Kingdom of Hungary. It was fought between the forces of Hungary, led by King Louis II of Hungary, Louis II, and the invading Ottoman Empire, commanded by Suleima ...

.

The Ottomans were also greatly attracted by the prestige of being in alliance with such a country as France, which would give them better legitimacy in their European dominions.

Meanwhile, Charles V was manoeuvring to form a

Habsburg-Persian alliance with

Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) and also known as Persia, is a country in West Asia. It borders Iraq to the west, Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Armenia to the northwest, the Caspian Sea to the north, Turkmenistan to the nort ...

, so that the Ottoman Empire would be attacked on its rear. Envoys were sent to Shah

Tahmasp I

Tahmasp I ( or ; 22 February 1514 – 14 May 1576) was the second shah of Safavid Iran from 1524 until his death in 1576. He was the eldest son of Shah Ismail I and his principal consort, Tajlu Khanum.

Tahmasp ascended the throne after the ...

in 1525, and again in 1529, pleading for an attack on the Ottoman Empire.

With the

War of the League of Cognac

The War of the League of Cognac (1526–1530) was fought between the Habsburg dominions of Charles V—primarily the Holy Roman Empire and Spain—and the League of Cognac, an alliance including the Kingdom of France, Pope Clement VII, the Re ...

(1526–1530) going on, Francis I continued to look for allies in Central Europe and formed a

Franco-Hungarian alliance

A Franco-Hungarian alliance was formed in October 1528 between King Francis I of France and King John Zápolya of Hungary.

Background

France had already been looking for allies in Central Europe. Its ambassador, Antonio Rincon, was sent on seve ...

in 1528 with the

Hungarian king

Zapolya, who himself had just become a vassal of the

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

that same year.

In 1528 also, Francis used the pretext of the protection of Christians in the Ottoman Empire to again enter into contact with Suleiman, asking for the return of a

mosque

A mosque ( ), also called a masjid ( ), is a place of worship for Muslims. The term usually refers to a covered building, but can be any place where Salah, Islamic prayers are performed; such as an outdoor courtyard.

Originally, mosques were si ...

to a

Christian Church

In ecclesiology, the Christian Church is what different Christian denominations conceive of as being the true body of Christians or the original institution established by Jesus Christ. "Christian Church" has also been used in academia as a syn ...

. In his 1528 letter to Francis I Suleiman politely refused, but guaranteed the protection of Christians in his states. He also renewed the privileges of French merchants which had been obtained in 1517 in Egypt.

Francis I lost in his European campaigns, and had to sign the ''

Paix des Dames'' in August 1529. He was even forced to supply some

galleys

A galley is a type of ship optimised for propulsion by oars. Galleys were historically used for warfare, trade, and piracy mostly in the seas surrounding Europe. It developed in the Mediterranean world during antiquity and continued to exist ...

to Charles V in his fight against the Ottomans. However, the Ottomans would continue their campaigns in Central Europe, and besiege the Habsburg capital in the 1529

siege of Vienna Sieges of Vienna may refer to:

* Siege of Vienna (1485), Hungarian victory during the Austro–Hungarian War.

*Siege of Vienna (1529), first Ottoman attempt to conquer Vienna.

*Battle of Vienna, 1683, second Ottoman attempt to conquer Vienna.

* Cap ...

, and again in 1532.

Exchange of embassies

In early July 1532, Suleiman was joined by the French ambassador

Antonio Rincon in

Belgrade

Belgrade is the Capital city, capital and List of cities in Serbia, largest city of Serbia. It is located at the confluence of the Sava and Danube rivers and at the crossroads of the Pannonian Basin, Pannonian Plain and the Balkan Peninsula. T ...

. Antonio Rincon presented Suleiman with

a magnificent four-tiered tiara, made in Venice for 115,000

ducats

The ducat ( ) coin was used as a trade coin in Europe from the later Middle Ages to the 19th century. Its most familiar version, the gold ducat or sequin containing around of 98.6% fine gold, originated in Venice in 1284 and gained wide inter ...

.

Rincon also described the Ottoman camp:

Francis I explained to the

Venetian ambassador

Giorgio Gritti in March 1531 his strategy regarding the Turks:

Ottoman embassies were sent to France, with the

Ottoman embassy to France (1533)

An Ottoman embassy to France was sent in 1533 by Hayreddin Barbarossa, the Ottoman Governor of Algiers, vassal of the Ottoman Emperor Suleiman the Magnificent.

A safe-conduct is thought to have been obtained in 1532 for the embassy by the Ottoma ...

led by

Hayreddin Barbarossa

Hayreddin Barbarossa (, original name: Khiḍr; ), also known as Hayreddin Pasha, Hızır Hayrettin Pasha, and simply Hızır Reis (c. 1466/1483 – 4 July 1546), was an Ottoman corsair and later admiral of the Ottoman Navy. Barbarossa's ...

, and the

Ottoman embassy to France (1534)

An Ottoman embassy to France occurred in 1534, with the objective to prepare and coordinate Franco-Ottoman offensives for the next year, 1535.Garnier, p.88 The embassy closely followed a first Ottoman embassy to France in 1533, as well as the ...

led by representatives of Suleiman.

Combined operations (1534–35)

Suleiman ordered Barbarossa to put his fleet at the disposition of Francis I to attack

Genoa

Genoa ( ; ; ) is a city in and the capital of the Italian region of Liguria, and the sixth-largest city in Italy. As of 2025, 563,947 people live within the city's administrative limits. While its metropolitan city has 818,651 inhabitan ...

and the

Milanese

Milanese (endonym in traditional orthography , ) is the central variety of the Western dialect of the Lombard language spoken in Milan, the rest of its metropolitan city, and the northernmost part of the province of Pavia. Milanese, due to t ...

. In July 1533 Francis received Ottoman representatives at

Le Puy, and he would dispatch in return

Antonio Rincon to Barbarossa in

North Africa

North Africa (sometimes Northern Africa) is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region. However, it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of t ...

and then to the

Asia Minor

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

.

Suleiman explained that "he could not possibly abandon the King of France, who was his brother".

The Franco-Ottoman alliance was by then effectively made.

In 1534 a Turkish fleet sailed against the Habsburg Empire at the request of Francis I, raiding the Italian coast and finally meeting with representatives of Francis in southern France.

The fleet went on to capture

Tunis

Tunis (, ') is the capital city, capital and largest city of Tunisia. The greater metropolitan area of Tunis, often referred to as "Grand Tunis", has about 2,700,000 inhabitants. , it is the third-largest city in the Maghreb region (after Casabl ...

in the

Conquest of Tunis (1534) on 16 August 1534 and continued raiding the Italian coast with the support of Francis I. In a counter-attack however, Charles V dislodged them in the

Conquest of Tunis (1535)

The conquest of Tunis occurred in 1535 when the Habsburg Emperor Charles V and his allies wrestled the city away from the control of the Ottoman Empire.

Background

In 1533, Suleiman the Magnificent ordered Hayreddin Barbarossa, whom he had summon ...

.

Permanent embassy of Jean de La Forêt (1535–1537)

=Trade and religious agreements

=

Treaties, or capitulations, were passed between the two countries starting in 1528 and 1536. The defeat in the

Conquest of Tunis (1535)

The conquest of Tunis occurred in 1535 when the Habsburg Emperor Charles V and his allies wrestled the city away from the control of the Ottoman Empire.

Background

In 1533, Suleiman the Magnificent ordered Hayreddin Barbarossa, whom he had summon ...

at the hands of

Andrea Doria

Andrea Doria, Prince of Melfi (; ; 30 November 146625 November 1560) was an Italian statesman, ', and admiral, who played a key role in the Republic of Genoa during his lifetime.

From 1528 until his death, Doria exercised a predominant influe ...

motivated the Ottoman Empire to enter into a formal alliance with France.

Ambassador

Jean de La Forêt

Jean de La Forêt, also Jean de La Forest or Jehan de la Forest (died 1537), was the first official French Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, serving from 1534 to 1537.''Catholics and Sultans: The Church and the Ottoman Empire 1453-1923'' by Charl ...

was sent to Istanbul, and for the first time was able to become permanent ambassador at the Ottoman court and to negotiate treaties.

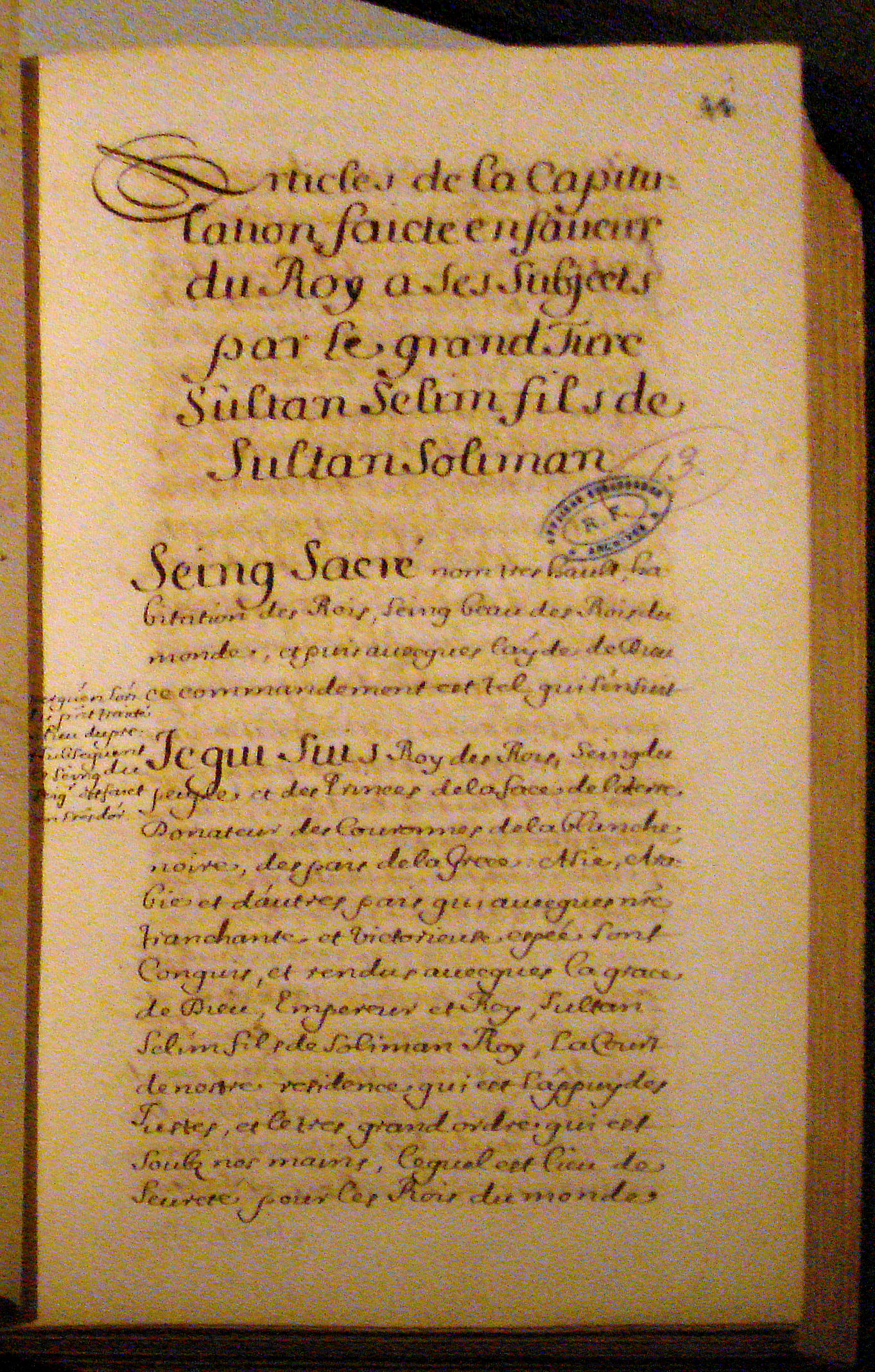

Jean de La Forêt negotiated the

capitulations on 18 February 1536, on the model of previous Ottoman commercial treaties with

Venice

Venice ( ; ; , formerly ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 islands that are separated by expanses of open water and by canals; portions of the city are li ...

and

Genoa

Genoa ( ; ; ) is a city in and the capital of the Italian region of Liguria, and the sixth-largest city in Italy. As of 2025, 563,947 people live within the city's administrative limits. While its metropolitan city has 818,651 inhabitan ...

,

although they only seem to have been ratified by the Ottomans later, in 1569, with ambassador

Claude Du Bourg. These capitulations allowed the French to obtain important privileges, such as the security of the people and goods, extraterritoriality, freedom to transport and sell goods in exchange for the payment of the

selamlik and customs fees. These capitulations would in effect give the French a near trade monopoly in seaport-towns that would be known as ''les Échelles du Levant''. Foreign vessels had to trade with Turkey under the French banner, after the payment of a percentage of their trade.

A French embassy and a Christian chapel were established in the town of

Galata

Galata is the former name of the Karaköy neighbourhood in Istanbul, which is located at the northern shore of the Golden Horn. The district is connected to the historic Fatih district by several bridges that cross the Golden Horn, most nota ...

across the Golden horn from

Constantinople

Constantinople (#Names of Constantinople, see other names) was a historical city located on the Bosporus that served as the capital of the Roman Empire, Roman, Byzantine Empire, Byzantine, Latin Empire, Latin, and Ottoman Empire, Ottoman empire ...

, and commercial privileges were also given to French merchants in the Turkish Empire. Through the capitulations of 1535, the French received the privilege to trade freely in all Ottoman ports.

A formal alliance was signed in 1536. The French were free to practice their religion in the Ottoman Empire, and French Catholics were given custody of holy places.

The capitulations were again renewed in 1604,

and lasted up until the establishment of the

Republic of Turkey

Turkey, officially the Republic of Türkiye, is a country mainly located in Anatolia in West Asia, with a relatively small part called East Thrace in Southeast Europe. It borders the Black Sea to the north; Georgia (country), Georgia, Armen ...

in 1923.

=Military and financial agreements

=

Jean de la Forêt also had secret military instructions to organize a combined offensive on Italy in 1535: Through the negotiations of de La Forêt with the

Grand Vizier

Grand vizier (; ; ) was the title of the effective head of government of many sovereign states in the Islamic world. It was first held by officials in the later Abbasid Caliphate. It was then held in the Ottoman Empire, the Mughal Empire, the Soko ...

Ibrahim Pasha it was agreed that combined military operations against Italy would take place, in which France would attack

Lombardy

The Lombardy Region (; ) is an administrative regions of Italy, region of Italy that covers ; it is located in northern Italy and has a population of about 10 million people, constituting more than one-sixth of Italy's population. Lombardy is ...

while the Ottoman Empire would attack from

Naples

Naples ( ; ; ) is the Regions of Italy, regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 908,082 within the city's administrative limits as of 2025, while its Metropolitan City of N ...

.

The Ottoman Empire also provided considerable financial support to Francis I. In 1533, Suleiman sent Francis I 100,000 gold pieces, so that he could form a coalition with England and German states against Charles V. In 1535, Francis asked for another 1 million

ducats

The ducat ( ) coin was used as a trade coin in Europe from the later Middle Ages to the 19th century. Its most familiar version, the gold ducat or sequin containing around of 98.6% fine gold, originated in Venice in 1284 and gained wide inter ...

. The military instructions of Jean de la Forêt were highly specific:

Finally, Suleiman intervened diplomatically in favour of Francis on the European scene. He is known to have sent at least one letter to the Protestant princes of Germany to encourage them to ally with Francis I against Charles V.

Francis I effectively allied with the

Schmalkaldic League

The Schmalkaldic League (; ; or ) was a military alliance of Lutheranism, Lutheran Prince of the Holy Roman Empire, principalities and cities within the Holy Roman Empire during the mid-16th century. It received its name from the town of Schm ...

against Charles V in 1535.

Italian War of 1536–1538

Franco-Ottoman military collaboration took place during the Italian War of 1536–1538 following the 1536 Treaty negotiated by

Jean de La Forêt

Jean de La Forêt, also Jean de La Forest or Jehan de la Forest (died 1537), was the first official French Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, serving from 1534 to 1537.''Catholics and Sultans: The Church and the Ottoman Empire 1453-1923'' by Charl ...

.

Campaign of 1536

Francis I invaded

Savoy

Savoy (; ) is a cultural-historical region in the Western Alps. Situated on the cultural boundary between Occitania and Piedmont, the area extends from Lake Geneva in the north to the Dauphiné in the south and west and to the Aosta Vall ...

in 1536,

starting the war. A Franco-Turkish fleet was stationed in

Marseille

Marseille (; ; see #Name, below) is a city in southern France, the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Departments of France, department of Bouches-du-Rhône and of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur Regions of France, region. Situated in the ...

by the end of 1536, threatening

Genoa

Genoa ( ; ; ) is a city in and the capital of the Italian region of Liguria, and the sixth-largest city in Italy. As of 2025, 563,947 people live within the city's administrative limits. While its metropolitan city has 818,651 inhabitan ...

.

While Francis I was attacking Milan and Genoa in April 1536, Barbarossa was raiding the Habsburg possessions in the Mediterranean.

In 1536 the French Admiral

Baron de Saint-Blancard combined his twelve French galleys with a small Ottoman fleet belonging to Barbarossa in

Algiers

Algiers is the capital city of Algeria as well as the capital of the Algiers Province; it extends over many Communes of Algeria, communes without having its own separate governing body. With 2,988,145 residents in 2008Census 14 April 2008: Offi ...

(an Ottoman galley and 6 galiotes), to attack the island of

Ibiza

Ibiza (; ; ; #Names and pronunciation, see below) or Iviza is a Spanish island in the Mediterranean Sea off the eastern coast of the Iberian Peninsula. It is 150 kilometres (93 miles) from the city of Valencia. It is the third largest of th ...

in the

Balearic Islands

The Balearic Islands are an archipelago in the western Mediterranean Sea, near the eastern coast of the Iberian Peninsula. The archipelago forms a Provinces of Spain, province and Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Spain, ...

. After failing to capture the tower of Salé, the fleet raided the Spanish coast from

Tortosa

Tortosa (, ) is the capital of the '' comarca'' of Baix Ebre, in Catalonia, Spain.

Tortosa is located at above sea level, by the Ebro river, protected on its northern side by the mountains of the Cardó Massif, of which Buinaca, one of the hi ...

to

Collioure

Collioure (; , ) is a commune in the southern French department of Pyrénées-Orientales.

Geography

The town of Collioure is on the Côte Vermeille (Vermilion Coast), in the canton of La Côte Vermeille and in the arrondissement of Céret.

...

, finally wintering in

Marseilles

Marseille (; ; see below) is a city in southern France, the prefecture of the department of Bouches-du-Rhône and of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region. Situated in the Provence region, it is located on the coast of the Mediterranean S ...

with 30 galleys from 15 October 1536 (the first time a Turkish fleet laid up for the winter in Marseilles).

Joint campaign of 1537

For 1537 important combined operations were agreed upon, in which the Ottomans would attack southern Italy and

Naples

Naples ( ; ; ) is the Regions of Italy, regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 908,082 within the city's administrative limits as of 2025, while its Metropolitan City of N ...

under

Barbarossa

Barbarossa, a name meaning "red beard" in Italian, primarily refers to:

* Frederick Barbarossa (1122–1190), Holy Roman Emperor

* Hayreddin Barbarossa (c. 1478–1546), Ottoman admiral

* Operation Barbarossa, the Axis invasion of the Soviet Uni ...

, and

Francis I would attack northern Italy with 50,000 men. Suleiman led an army of 300,000 from Constantinople to

Albania

Albania ( ; or ), officially the Republic of Albania (), is a country in Southeast Europe. It is located in the Balkans, on the Adriatic Sea, Adriatic and Ionian Seas within the Mediterranean Sea, and shares land borders with Montenegro to ...

, with the objective of transporting them to Italy with the fleet.

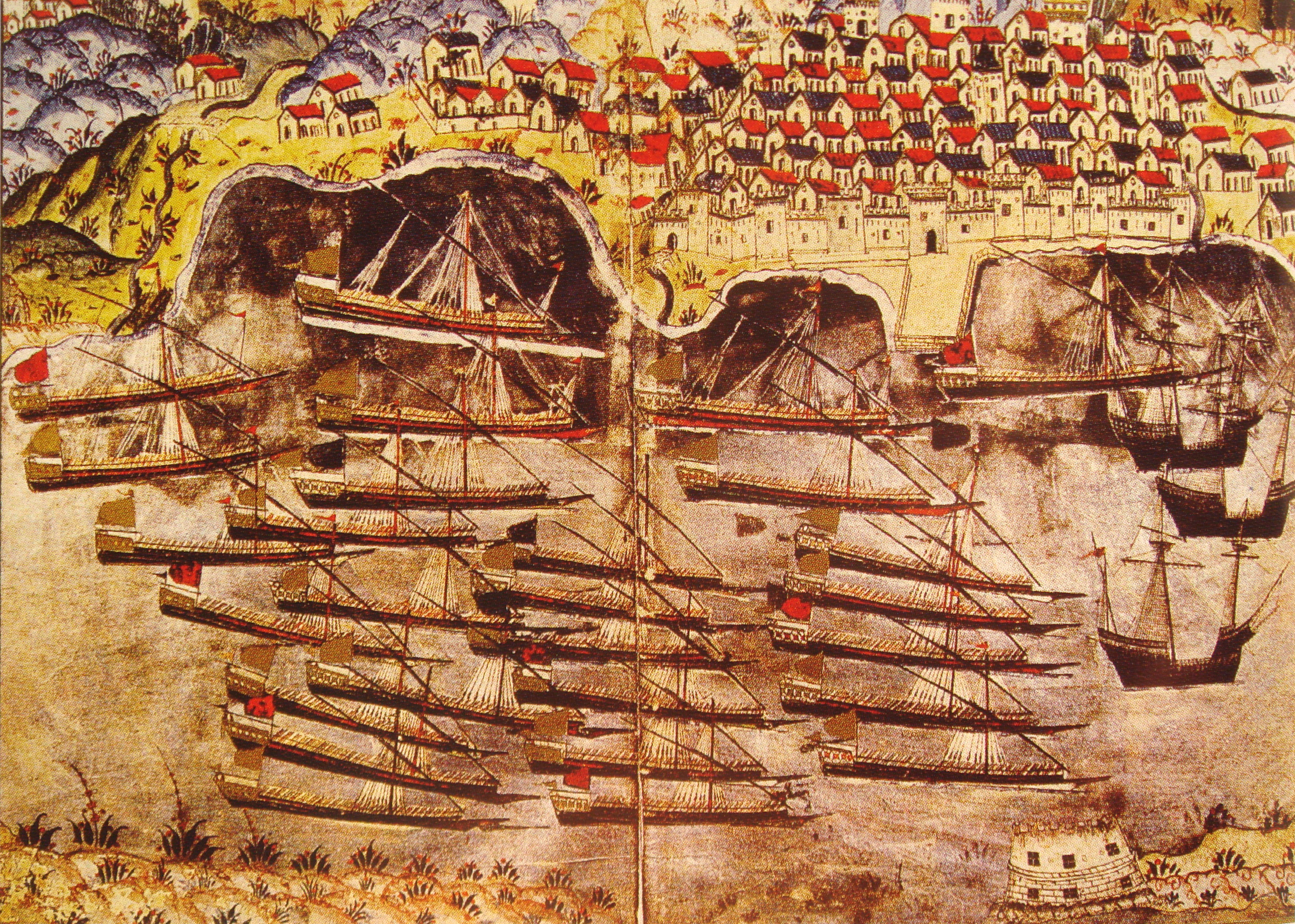

The Ottoman fleet gathered in

Avlona Avlon, Avlona or Avlonas may refer to:

* Avlona, Albania, an English obsolete name of Vlorë, a seaport in Albania, still used in some other languages

* Avlona, Cyprus, a town in Cyprus

* settlements in Greece:

** Avlonas, Attica, a town in northe ...

with 100 galleys, accompanied by the French ambassador Jean de La Forêt.

They landed in

Castro, Apulia

Castro (Salentino: ) is a town and ''comune'' in the Italian province of Lecce in the Apulia region of south-eastern Italy.

History

Castro derives its name from ''Castrum Minervae'' (Latin for "Athena's castle"), which was an ancient town of ...

by the end of July 1537, and departed two weeks later with many prisoners.

Barbarossa had laid waste to the region around

Otranto

Otranto (, , ; ; ; ; ) is a coastal town, port and ''comune'' in the province of Lecce (Apulia, Italy), in a fertile region once famous for its breed of horses. It is one of I Borghi più belli d'Italia ("The most beautiful villages of Italy").

...

, carrying about 10,000 people into slavery. Francis however failed to meet his commitment, and instead attacked the

Netherlands

, Terminology of the Low Countries, informally Holland, is a country in Northwestern Europe, with Caribbean Netherlands, overseas territories in the Caribbean. It is the largest of the four constituent countries of the Kingdom of the Nether ...

.

The Ottomans departed from Southern Italy, and instead mounted the

siege of Corfu in August 1537.

where they were met by the French Admiral

Baron de Saint-Blancard with 12 galleys in early September 1537.

Saint-Blancard in vain attempted to convince the Ottomans to again raid the coasts of

Apulia

Apulia ( ), also known by its Italian language, Italian name Puglia (), is a Regions of Italy, region of Italy, located in the Southern Italy, southern peninsular section of the country, bordering the Adriatic Sea to the east, the Strait of Ot ...

,

Sicily

Sicily (Italian language, Italian and ), officially the Sicilian Region (), is an island in the central Mediterranean Sea, south of the Italian Peninsula in continental Europe and is one of the 20 regions of Italy, regions of Italy. With 4. ...

and the March of

Ancona

Ancona (, also ; ) is a city and a seaport in the Marche region of central Italy, with a population of around 101,997 . Ancona is the capital of the province of Ancona, homonymous province and of the region. The city is located northeast of Ro ...

, and Suleiman returned with his fleet to Constantinople by mid-September without having captured Corfu.

French ambassador Jean de La Forêt became seriously ill and died around that time.

Francis I finally penetrated into Italy, and reached

Rivoli on 31 October 1537.

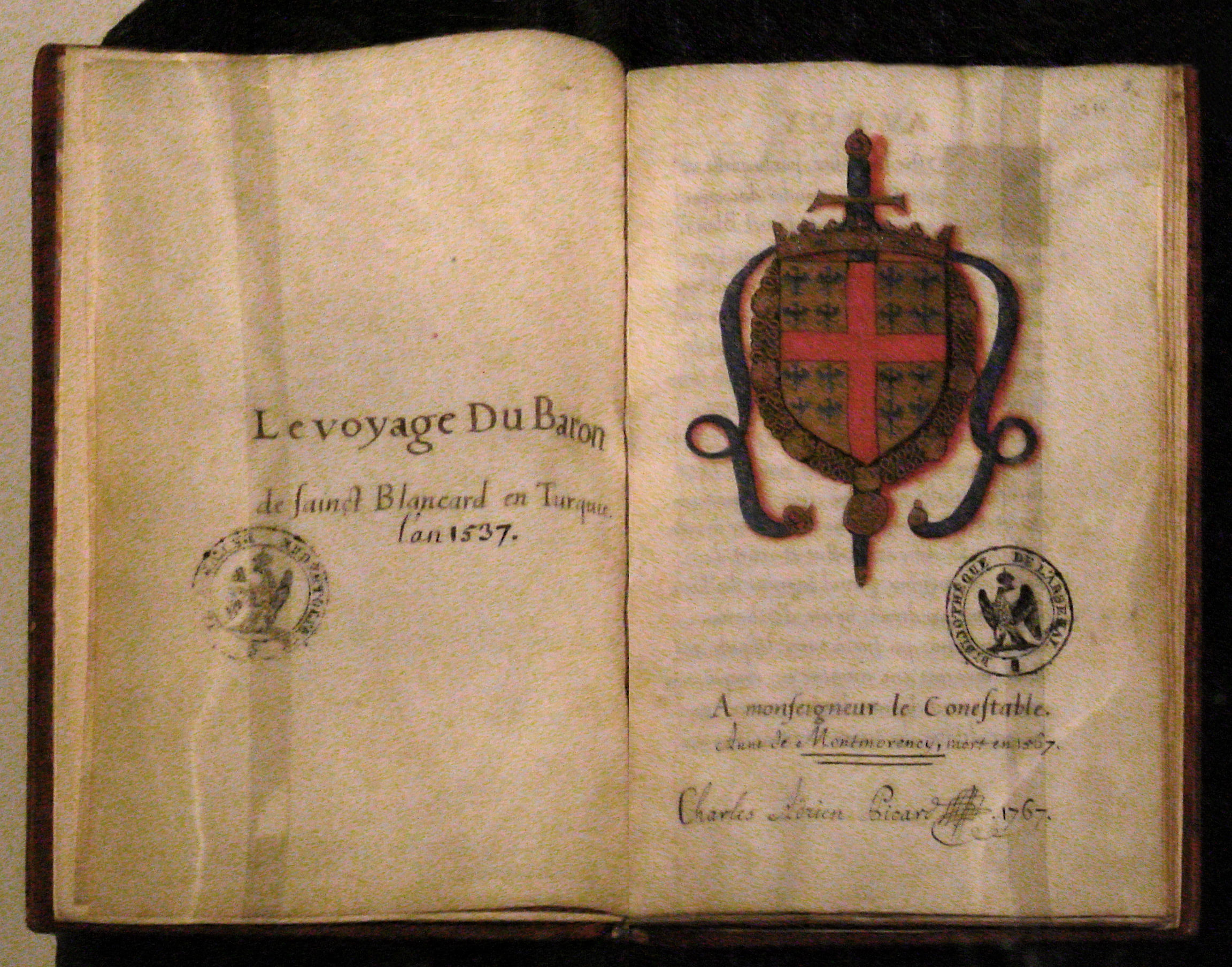

For two years, until 1538, Saint-Blancard would accompany the fleet of Barbarossa, and between 1537 and 1538, Saint-Blancard would winter with his galleys in Constantinople and meet with Suleiman. During that time, Saint-Blancard was funded by Barbarossa. The campaign of Saint-Blancard with the Ottomans was written down in ''Le Voyage du Baron de Saint Blancard en Turquie'', by

Jean de la Vega

Jean de la Vega, also Jehan de la Vega, was a French traveler and writer of the 16th century. He was a member of the fleet Bertrand d'Ornesan which collaborated with the Ottomans under the Franco-Ottoman alliance.

As a member of D'Ornessan's sta ...

, who had accompanied Saint-Blancard in his mission. Although the French accompanied most of the campaigns of Barbarossa, they sometimes refrained from participating in Turkish assaults, and their accounts express horror at the violence of these encounters, in which Christians were slaughtered or taken as captives.

Habsburg-Valois Truce of Nice (1538)

With

Charles V Charles V may refer to:

Kings and Emperors

* Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor (1500–1558)

* Charles V of Naples (1661–1700), better known as Charles II of Spain

* Charles V of France (1338–1380), called the Wise

Others

* Charles V, Duke ...

unsuccessful in battle and squeezed between the French invasion and the Ottomans, he and Francis I ultimately made peace with the

Truce of Nice on 18 June 1538.

In the truce, Charles and Francis made an agreement to ally against the Ottomans to expel them from Hungary.

Charles V turned his attention to fighting the Ottomans, but could not launch large forces in Hungary due to a raging conflict with the German princes of the

Schmalkaldic League

The Schmalkaldic League (; ; or ) was a military alliance of Lutheranism, Lutheran Prince of the Holy Roman Empire, principalities and cities within the Holy Roman Empire during the mid-16th century. It received its name from the town of Schm ...

.

On 28 September 1538 Barbarosa won the major

Battle of Preveza

The Battle of Preveza (also known as Prevesa) was a naval engagement that took place on 28 September 1538 near Preveza in the Ionian Sea in northwestern Greece between an Ottoman fleet and that of a Holy League. The battle was an Ottoman vi ...

against the Imperial fleet. At the end of the conflict, Suleiman set as a condition for peace with Charles V that the latter returns to Francis I the lands that were his by right.

The Franco-Ottoman alliance was crippled for a while however, due to Francis' official change of alliance at Nice in 1538. Open conflict between Charles and Francis would resume in 1542, as well as Franco-Ottoman collaboration, with the 4 July 1541 assassination by Imperial troops of the

French Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire

France had a permanent embassy to the Ottoman Empire beginning in 1535, during the time of King Francis I and Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent. It is considered to have been the direct predecessor of the modern-day embassy to the Republic of Turk ...

Antonio Rincon, as he was travelling through Italy near

Pavia

Pavia ( , ; ; ; ; ) is a town and comune of south-western Lombardy, in Northern Italy, south of Milan on the lower Ticino (river), Ticino near its confluence with the Po (river), Po. It has a population of c. 73,086.

The city was a major polit ...

.

Italian War of 1542–1546 and Hungary Campaign of 1543

During the Italian War of 1542–46 Francis I and Suleiman I were again pitted against the

Holy Roman Emperor

The Holy Roman Emperor, originally and officially the Emperor of the Romans (disambiguation), Emperor of the Romans (; ) during the Middle Ages, and also known as the Roman-German Emperor since the early modern period (; ), was the ruler and h ...

Charles V Charles V may refer to:

Kings and Emperors

* Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor (1500–1558)

* Charles V of Naples (1661–1700), better known as Charles II of Spain

* Charles V of France (1338–1380), called the Wise

Others

* Charles V, Duke ...

, and

Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is known for his Wives of Henry VIII, six marriages and his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. ...

of

England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

. The course of the war saw extensive fighting in Italy, France, and the

Low Countries

The Low Countries (; ), historically also known as the Netherlands (), is a coastal lowland region in Northwestern Europe forming the lower Drainage basin, basin of the Rhine–Meuse–Scheldt delta and consisting today of the three modern "Bene ...

, as well as attempted invasions of

Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

and England; but, although the conflict was ruinously expensive for the major participants, its outcome was inconclusive. In the

Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern ...

, active naval collaboration took place between the two powers to fight against Spanish forces, following a request by Francis I, conveyed by

Antoine Escalin des Aimars

Antoine Escalin des Aimars (1516–1578), also known as Captain Polin or Captain Paulin, later Baron de La Garde, was French ambassador to the Ottoman Empire from 1541 to 1547, and ''"Général des Galères"'' ("General of the galleys") from 154 ...

, also known as Captain Polin.

Failed coordination in the campaign of 1542

In early 1542, Polin successfully negotiated the details of the alliance, with the Ottoman Empire promising to send 60,000 troops against the territories of the German king Ferdinand, as well as 150 galleys against Charles, while France promised to attack

Flanders

Flanders ( or ; ) is the Dutch language, Dutch-speaking northern portion of Belgium and one of the communities, regions and language areas of Belgium. However, there are several overlapping definitions, including ones related to culture, la ...

, harass the coasts of Spain with a naval force, and send 40 galleys to assist the Turks for operations in the Levant.

A landing harbour in the north of the

Adriatic

The Adriatic Sea () is a body of water separating the Italian Peninsula from the Balkans, Balkan Peninsula. The Adriatic is the northernmost arm of the Mediterranean Sea, extending from the Strait of Otranto (where it connects to the Ionian Se ...

was prepared for Barberousse, at

Marano. The port was seized in the name of France by

Piero Strozzi

Piero (or Pietro) Strozzi ( 1510 – 21 June 1558) was an Italian military leader. He was a member of the rich Florentine family of the Strozzi.

Biography

left, Portrait of Piero Strozzi by Anonymous artist

Born in Florence, Piero Strozzi w ...

on 2 January 1542.

Polin left Constantinople on 15 February 1542 with a contract from Suleiman outlining the details of the Ottoman commitment for 1542. He arrived in

Blois

Blois ( ; ) is a commune and the capital city of Loir-et-Cher Departments of France, department, in Centre-Val de Loire, France, on the banks of the lower Loire river between Orléans and Tours.

With 45,898 inhabitants by 2019, Blois is the mos ...

on 8 March 1542 to obtain a ratification of the agreement by Francis I.

[Garnier, p.211] Accordingly, Francis I designated the city of

Perpignan

Perpignan (, , ; ; ) is the prefectures in France, prefecture of the Pyrénées-Orientales departments of France, department in Southern France, in the heart of the plain of Roussillon, at the foot of the Pyrenees a few kilometres from the Me ...

as the objective for the Ottoman expedition, in order to obtain a seaway to Genoa. Polin, after some delays in Venice, finally managed to take a galley to Constantinople on 9 May 1542, but he arrived too late for the Ottomans to launch a sea campaign.

Meanwhile, Francis I initiated the hostilities with Charles V on 20 July 1542, and kept with his part of the agreement by laying siege at Perpignan and attacking Flanders.

André de Montalembert André de Montalembert (1483–1553), Seigneur d' Essé, was a French nobleman and officer of the 16th century. As a young boy he fought in the Italian Wars. When King Francis I met with Henry VIII of England at the Field of the Cloth of Gold in 1 ...

was sent to Constantinople to ascertain the Ottoman offensive, but it turned out that Suleiman, partly under the anti-alliance influence of

Suleyman Pasha, was unwilling to send an army that year, and promised to send an army twice as strong the following year, in 1543.

When Francis I learnt from André de Montalembert that the Ottomans were not coming, he raised the siege of Perpignan.

Joint siege of Nice (1543)

Most notably, the French forces, led by

François de Bourbon and the Ottoman forces, led by Barbarossa, joined at

Marseille

Marseille (; ; see #Name, below) is a city in southern France, the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Departments of France, department of Bouches-du-Rhône and of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur Regions of France, region. Situated in the ...

in August 1543, and collaborated to bombard the city of

Nice

Nice ( ; ) is a city in and the prefecture of the Alpes-Maritimes department in France. The Nice agglomeration extends far beyond the administrative city limits, with a population of nearly one million[siege of Nice

The siege of Nice occurred in 1543 and was part of the Italian War of 1542–46 in which Francis I and Suleiman the Magnificent collaborated as part of the Franco-Ottoman alliance against the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, and Henry VIII of ...]

.

In this action 110 Ottoman galleys, amounting to 30,000 men, combined with 50 French galleys.

[''The Cambridge History of Islam'', p.328] The Franco-Ottomans laid waste to the city of Nice, but were confronted by a stiff resistance which gave rise to the story of

Catherine Ségurane

Catherine Ségurane ( in the Niçard dialect of Provençal) is a folk heroine of the city of Nice, France who is said to have played a decisive role in repelling the city's siege by Turkish invaders allied with Francis I, during the Franco-Ott ...

. They had to raise the siege of the citadel upon the arrival of enemy troops.

Barbarossa wintering in Toulon (1543–1544)

After the siege of Nice, the Ottomans were offered by Francis to winter at

Toulon

Toulon (, , ; , , ) is a city in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region of southeastern France. Located on the French Riviera and the historical Provence, it is the prefecture of the Var (department), Var department.

The Commune of Toulon h ...

, so that they could continue to harass the

Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire, also known as the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation after 1512, was a polity in Central and Western Europe, usually headed by the Holy Roman Emperor. It developed in the Early Middle Ages, and lasted for a millennium ...

, and especially the coast of

Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

and Italy, as well the communications between the two countries:

During the wintering of Barbarossa, the

Toulon Cathedral

Toulon Cathedral (), also known as Sainte-Marie-Majeure, is a Catholic church located in Toulon, in the Var department of France. The cathedral is a national monument. Construction of the church began in the 11th century and finished in the 18th ...

was transformed into a

mosque

A mosque ( ), also called a masjid ( ), is a place of worship for Muslims. The term usually refers to a covered building, but can be any place where Salah, Islamic prayers are performed; such as an outdoor courtyard.

Originally, mosques were si ...

, the call to prayer occurred five times a day, and Ottoman coinage was the currency of choice. According to an observer: "To see Toulon, one might imagine oneself at Constantinople".

Throughout the winter, the Ottomans were able to use Toulon as a base to attack the Spanish and Italian coasts, raiding

Sanremo

Sanremo, also spelled San Remo in English and formerly in Italian, is a (municipality) on the Mediterranean coast of Liguria, in northwestern Italy. Founded in Roman times, it has a population of 55,000, and is known as a tourist destination ...

,

Borghetto Santo Spirito

Borghetto Santo Spirito is a ''comune'' (municipality) in the Province of Savona in the Italian region Liguria, located about southwest of Genoa and about southwest of Savona.

Borghetto Santo Spirito borders the following municipalities: Boiss ...

,

Ceriale

Ceriale (, locally ) is a ''comune'' (municipality) in the Province of Savona in the Italian region of Liguria, located about southwest of Genoa and about southwest of Savona.

Ceriale borders the following municipalities: Albenga, Balestrino, ...

and defeating Italo-Spanish naval attacks. Sailing with his whole fleet to

Genoa

Genoa ( ; ; ) is a city in and the capital of the Italian region of Liguria, and the sixth-largest city in Italy. As of 2025, 563,947 people live within the city's administrative limits. While its metropolitan city has 818,651 inhabitan ...

, Barbarossa negotiated with

Andrea Doria

Andrea Doria, Prince of Melfi (; ; 30 November 146625 November 1560) was an Italian statesman, ', and admiral, who played a key role in the Republic of Genoa during his lifetime.

From 1528 until his death, Doria exercised a predominant influe ...

the release of

Turgut Reis

Dragut (; 1485 – 23 June 1565) was an Ottoman corsair, naval commander, governor, and noble. Under his command, the Ottoman Empire's maritime power was extended across North Africa. Recognized for his military genius, and as being among "th ...

. The Ottomans departed from their Toulon base in May 1544 after Francis I had paid 800,000

ecus to Barbarossa.

[Crowley, p.75]

Captain Polin in Constantinople (1544)

Five French galleys under

Captain Polin

Antoine Escalin des Aimars (1516–1578), also known as Captain Polin or Captain Paulin, later Baron de La Garde, was French ambassador to the Ottoman Empire from 1541 to 1547, and ''"Général des Galères"'' ("General of the galleys") from 154 ...

, including the superb ''

Réale'', accompanied Barbarossa's fleet, on a diplomatic mission to Suleiman.

The French fleet accompanied Barbarossa during his attacks on the west coast of Italy on the way to Constantinople, as he laid waste to the cities of

Porto Ercole

Porto Ercole () is an Italian town located in the municipality of Monte Argentario, in the Province of Grosseto, Tuscany. It is one of the two major towns that form the township, along with Porto Santo Stefano. Its name means "Port Hercules". It i ...

,

Giglio,

Talamona

Talamona () is a (municipality) in the Province of Sondrio in the Italian region of Lombardy, located about northeast of Milan and about west of Sondrio. As of 31 December 2004, it had a population of 4,623 and an area of .All demographics and o ...

,

Lipari

Lipari (; ) is a ''comune'' including six of seven islands of the Aeolian Islands (Lipari, Vulcano, Panarea, Stromboli, Filicudi and Alicudi) and it is located in the Tyrrhenian Sea off the northern coast of Sicily, Southern Italy; it is ...

and took about 6,000 captives, but separated in

Sicily

Sicily (Italian language, Italian and ), officially the Sicilian Region (), is an island in the central Mediterranean Sea, south of the Italian Peninsula in continental Europe and is one of the 20 regions of Italy, regions of Italy. With 4. ...

from Barbarossa's fleet to continue alone to the Ottoman capital.

Jerôme Maurand, a priest of

Antibes

Antibes (, , ; ) is a seaside city in the Alpes-Maritimes Departments of France, department in Southeastern France. It is located on the French Riviera between Cannes and Nice; its cape, the Cap d'Antibes, along with Cap Ferrat in Saint-Jean-Ca ...

who accompanied Polin and the Ottoman fleet in 1544, wrote a detailed account in ''Itinéraire d'Antibes à Constantinonple''. They arrived in Constantinople on 10 August 1544 to meet with Suleiman and give him an account of the campaign.

[Garnier, p.240] Polin was back to Toulon on 2 October 1544.

Joint campaign in Hungary (1543–1544)

On land Suleiman was concomitantly fighting for the conquest of

Hungary

Hungary is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning much of the Pannonian Basin, Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia and ...

in 1543, as a part of the

Little War. French troops were supplied to the Ottomans on the Central European front: in Hungary, a French artillery unit was dispatched in 1543–1544 and attached to the

Ottoman Army

The Military of the Ottoman Empire () was the armed forces of the Ottoman Empire. It was founded in 1299 and dissolved in 1922.

Army

The Military of the Ottoman Empire can be divided in five main periods. The foundation era covers the years ...

.

Following major sieges such as the

siege of Esztergom (1543)

The siege of Esztergom occurred between 25 July and 10 August 1543, when the Ottoman Empire, Ottoman Military_of_the_Ottoman_Empire, army, led by Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent, besieged the city of Esztergom in modern Hungary. The city was capt ...

, Suleiman took a commanding position in Hungary, obtaining the signature of the

Truce of Adrianople

The Truce of Adrianople in 1547, named after the Ottoman city of Adrianople (present-day Edirne), was signed between Charles V and Suleiman the Magnificent. Through this treaty, Ferdinand I of Austria and Charles V recognized total Ottoman cont ...

with the Habsburg in 1547.

Besides the powerful effect of a

strategic alliance

A strategic alliance is an agreement between two or more Legal party, parties to pursue a set of agreed upon objectives needed while remaining independent organizations.

The alliance is a cooperation or collaboration which aims for a synergy wh ...

encircling the Habsburg Empire, combined tactical operations were significantly hampered by the distances involved, the difficulties in communication, and the unpredictable changes of plans on one side or the other. From a financial standpoint, fiscal revenues were also generated for both powers through the ransoming of enemy ships in the Mediterranean. The French Royal House also borrowed large amounts of

gold

Gold is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol Au (from Latin ) and atomic number 79. In its pure form, it is a brightness, bright, slightly orange-yellow, dense, soft, malleable, and ductile metal. Chemically, gold is a transition metal ...

from the Ottoman banker

Joseph Nasi

Joseph Nasi (1524 – 1579), known in Portuguese as João Miques, was a Portuguese Sephardi diplomat and administrator, member of the House of Mendes and House of Benveniste, nephew of Doña Gracia Mendes Nasi, and an influential figure in th ...

and the Ottoman Empire, amounting to around 150,000

écus as of 1565, the repayment of which became contentious in the following years.

French support in the Ottoman-Safavid war (1547)

In 1547, when

Sultan Suleiman I attacked Persia in his second campaign of the

Ottoman-Safavid War (1532–1555), France sent him the ambassador

Gabriel de Luetz

Gabriel de Luetz, Baron et Seigneur d'Aramon et de Vallabregues (died 1553), often also abbreviated to Gabriel d'Aramon, was the French Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire from 1546 to 1553, in the service first of Francis I, who dispatched him t ...

to accompany him in his campaign.

Gabriel de Luetz was able to give decisive military advice to Suleiman, as when he advised on artillery placement during the

Siege of Van.

[''The Cambridge history of Iran'' by William Bayne Fisher p.384''ff'']

Consequences

The alliance provided strategic support to, and effectively protected, the kingdom of France from the ambitions of

Charles V Charles V may refer to:

Kings and Emperors

* Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor (1500–1558)

* Charles V of Naples (1661–1700), better known as Charles II of Spain

* Charles V of France (1338–1380), called the Wise

Others

* Charles V, Duke ...

. It also gave the opportunity for the Ottoman Empire to become involved in European diplomacy and gain prestige in its European dominions. According to historian Arthur Hassall the consequences of the Franco-Ottoman alliance were far-reaching: ''"The Ottoman alliance had powerfully contributed to save France from the grasp of Charles V, it had certainly aided

Protestantism

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

in

Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

, and from a French point of view, it had rescued the North German allies of Francis I."'

Political debate

Side effects included a lot of negative propaganda against the actions of France and its "unholy" alliance with a

Muslim

Muslims () are people who adhere to Islam, a Monotheism, monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God ...

power. Charles V strongly appealed to the rest of Europe against the alliance of Francis I, and caricatures were made showing the collusion between France and the Ottoman Empire.

[ Ecouen Museum exhibit] In the late sixteenth century, Italian political philosopher

Giovanni Botero

Giovanni Botero (c. 1544 – 23 June 1617) was an Italian thinker, priest, poet, and diplomat, author of '' Della Ragion di Stato (The Reason of State)'',Botero, Giovanni, Pamela Waley, Daniel Philip Waley, and Robert Peterson. 1956. The Rea ...

referred to the alliance as "a vile, infamous, diabolical treaty" and blamed it for the extinction of the

Valois dynasty

The Capetian House of Valois ( , also , ) was a cadet branch of the Capetian dynasty. They succeeded the House of Capet (or "Direct Capetians") to the French throne, and were the royal house of France from 1328 to 1589. Junior members of th ...

. Even the French

Huguenot

The Huguenots ( , ; ) are a Religious denomination, religious group of French people, French Protestants who held to the Reformed (Calvinist) tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, ...

Francois de La Noue denounced the alliance in a 1587 work, claiming that "this confederation has been the occasion to diminish the glory and power of such a flourishing kingdom as France."

Numerous authors intervened to take the defense of the French king for his alliance. Authors wrote about the Ottoman civilization, such as

Guillaume Postel

Guillaume Postel (25 March 1510 – 6 September 1581) was a French linguist, Orientalist, astronomer, Christian Kabbalist, diplomat, polyglot, professor, religious universalist, and writer.

Born in the village of Barenton in Normandy, Post ...

or

Christophe Richer, in sometimes extremely positive ways. In the 1543 work ''Les Gestes de Francoys de Valois'',

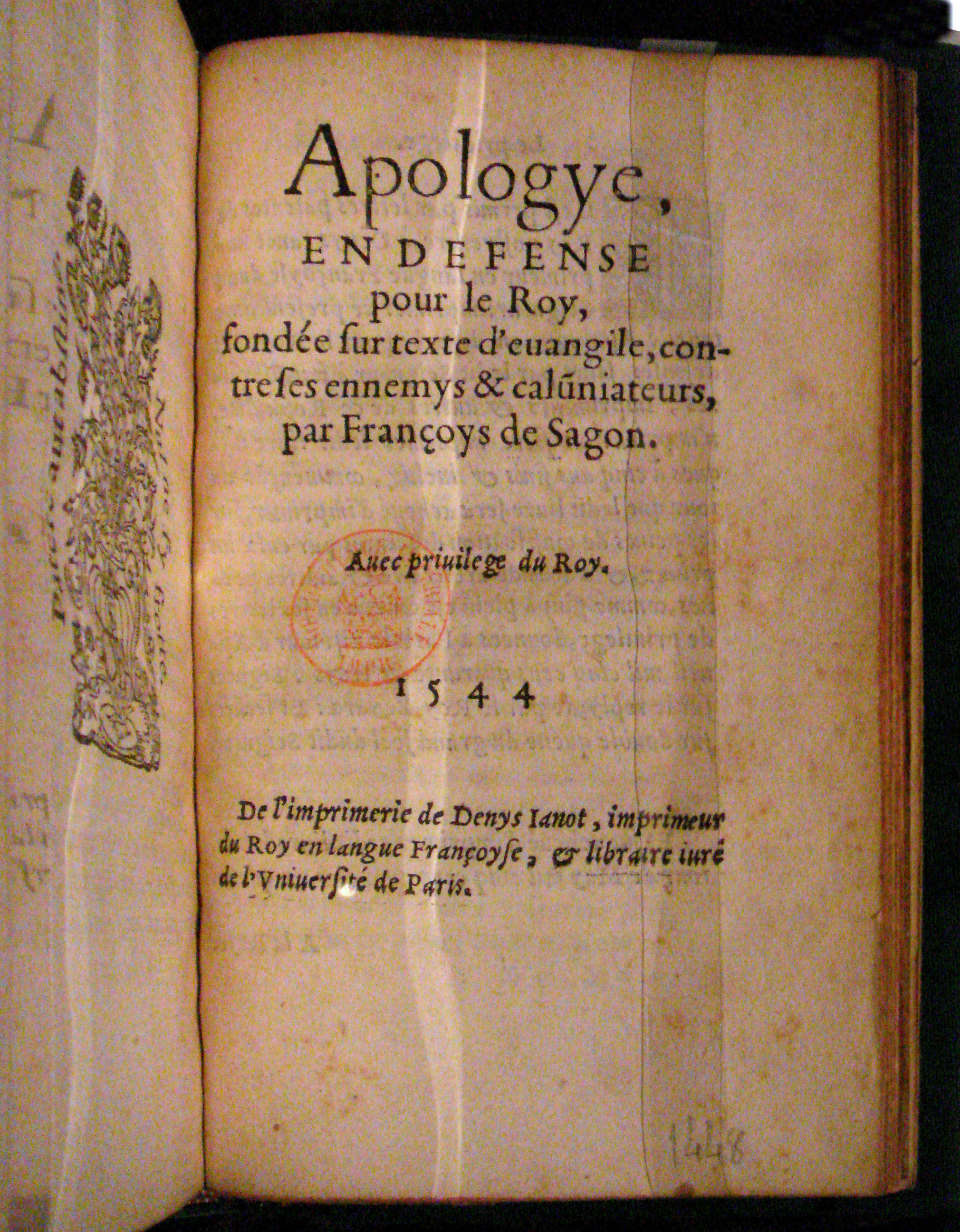

Etienne Dolet justified the alliance by comparing it to Charles V's relations with Persia and Tunis. Dolet also claimed that it should not be "forbidden for a prince to make alliance and seek intelligence of another, whatever creed or law he may be." The author

François de Sagon

François de Sagon was a French priest and poet of the 16th century.

He was famous for his enmity with Clément Marot.

He published in 1544 ''Apologye en défense pour le Roy'', a text defending the actions of Francis I in the Franco-Ottoman all ...

wrote in 1544 ''Apologye en défense pour le Roy'', a text defending the actions of Francis I by drawing parallels with the

parable of the Good Samaritan

The parable of the Good Samaritan is told by Jesus in the Gospel of Luke. It is about a traveler (implicitly understood to be Jewish) who is stripped of clothing, beaten, and left half dead alongside the road. A Jewish priest and then a Levite ...

in the

Bible

The Bible is a collection of religious texts that are central to Christianity and Judaism, and esteemed in other Abrahamic religions such as Islam. The Bible is an anthology (a compilation of texts of a variety of forms) originally writt ...

, in which Francis is compared to the wounded man, the Emperor to the thieves, and Suleiman to the

Good Samaritan

In most contexts, the concept of good denotes the conduct that should be preferred when posed with a choice between possible actions. Good is generally considered to be the opposite of evil. The specific meaning and etymology of the term and its ...

providing help to Francis.

Guillaume du Bellay

Guillaume du Bellay, seigneur de Langey (1491 – 9 January 1543), was a French diplomat and general from a notable Angevin family under King Francis I.

He was born at the château of Glatigny, near Souday, in 1491.

His father, Louis du Bella ...

and his brother

Jean du Bellay

Jean du Bellay (1492 – 16 February 1560) was a French diplomat and cardinal, a younger brother of Guillaume du Bellay, and cousin and patron of the poet Joachim du Bellay. He was bishop of Bayonne by 1526, a member of the ''Conseil privé'' ...

wrote in defense of the alliance, at the same time minimizing it and legitimizing on the ground that Francis I was defending himself against an aggression.

Jean de Montluc used examples from Christian history to justify the endeavour to obtain Ottoman support.

Jean de Montluc's brother

Blaise de Montluc

Blaise de Monluc, also known as Blaise de Lasseran-Massencôme, seigneur de Monluc, (24 July 1577) was a professional soldier whose career began in 1521 and reached the rank of marshal of France in 1574. Written between 1570 and 1576, an account ...

argued in 1540 that the alliance was permissible because "against one's enemies one can make arrows of any kind of wood." In 1551, wrote ''Apologie, faicte par un serviteur du Roy, contre les calomnies des Impériaulx: sur la descente du Turc''.

Cultural and scientific exchanges

Cultural and scientific exchanges between France and the Ottoman Empire flourished. French scholars such as

Guillaume Postel

Guillaume Postel (25 March 1510 – 6 September 1581) was a French linguist, Orientalist, astronomer, Christian Kabbalist, diplomat, polyglot, professor, religious universalist, and writer.

Born in the village of Barenton in Normandy, Post ...

or

Pierre Belon

Pierre Belon (1517–1564) was a French traveller, natural history, naturalist, writer and diplomat. Like many others of the Renaissance period, he studied and wrote on a range of topics including ichthyology, ornithology, botany, comparative anat ...

were able to travel to

Asia Minor

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

and the

Middle East

The Middle East (term originally coined in English language) is a geopolitical region encompassing the Arabian Peninsula, the Levant, Turkey, Egypt, Iran, and Iraq.

The term came into widespread usage by the United Kingdom and western Eur ...

to collect information.

Scientific exchange is thought to have occurred, as numerous works in Arabic, especially pertaining to

astronomy

Astronomy is a natural science that studies celestial objects and the phenomena that occur in the cosmos. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and their overall evolution. Objects of interest includ ...

were brought back, annotated and studied by scholars such as Guillaume Postel. Transmission of scientific knowledge, such as the

Tusi-couple, may have occurred on such occasions, at the time when

Copernicus

Nicolaus Copernicus (19 February 1473 – 24 May 1543) was a Renaissance polymath who formulated a mathematical model, model of Celestial spheres#Renaissance, the universe that placed heliocentrism, the Sun rather than Earth at its cen ...

was establishing his own astronomical theories.

Books, such as the Muslim holy text, the

Quran

The Quran, also Romanization, romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a Waḥy, revelation directly from God in Islam, God (''Allah, Allāh''). It is organized in 114 chapters (, ) which ...

, were brought back to be integrated in Royal libraries, such as the ''Bibliothèque Royale de Fontainebleau'', to create a foundation for the ''Collège des lecteurs royaux'', future

Collège de France

The (), formerly known as the or as the ''Collège impérial'' founded in 1530 by François I, is a higher education and research establishment () in France. It is located in Paris near La Sorbonne. The has been considered to be France's most ...

.

French novels and tragedies were written with the Ottoman Empire as a theme or background.

In 1561,

Gabriel Bounin published ''La Soltane'', a

tragedy

A tragedy is a genre of drama based on human suffering and, mainly, the terrible or sorrowful events that befall a tragic hero, main character or cast of characters. Traditionally, the intention of tragedy is to invoke an accompanying catharsi ...

highlighting the role of

Roxelane

Hürrem Sultan (; , "''the joyful one''"; 1505– 15 April 1558), also known as Roxelana (), was the chief consort, the first Haseki Sultan of the Ottoman Empire and the legal wife of the Ottoman Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent, and the mother ...

in the 1553 execution of

Mustapha, the elder son of

Suleiman

Suleiman (; or dictionary.reference.comsuleiman/ref>) is the Arabic name of the Jewish and Quranic king and Islam, Islamic prophet Solomon (name), Solomon.

Suleiman the Magnificent (1494–1566) was the longest-reigning sultan of the Ottoman E ...

.

This tragedy marks the first time the Ottomans were introduced on stage in France.

International trade

Strategically, the alliance with the Ottoman Empire also allowed France to offset to some extent the

Habsburg Empire

The Habsburg monarchy, also known as Habsburg Empire, or Habsburg Realm (), was the collection of empires, kingdoms, duchies, counties and other polities (composite monarchy) that were ruled by the House of Habsburg. From the 18th century it is ...

's advantage in the

New World

The term "New World" is used to describe the majority of lands of Earth's Western Hemisphere, particularly the Americas, and sometimes Oceania."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: ...

trade, and French trade with the eastern Mediterranean through

Marseille

Marseille (; ; see #Name, below) is a city in southern France, the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Departments of France, department of Bouches-du-Rhône and of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur Regions of France, region. Situated in the ...

indeed increased considerably after 1535. After the Capitulations of 1569, France also gained precedence over all other Christian states, and her authorization was required for when another state wished to trade with the Ottoman Empire.

Military alliance under Henry II

The son of Francis I,

Henry II

Henry II may refer to:

Kings

* Saint Henry II, Holy Roman Emperor (972–1024), crowned King of Germany in 1002, of Italy in 1004 and Emperor in 1014

*Henry II of England (1133–89), reigned from 1154

*Henry II of Jerusalem and Cyprus (1271–1 ...

, also sealed a treaty with Suleyman in order to cooperate against the

Austrian Navy

The Austro-Hungarian Navy or Imperial and Royal War Navy (, in short ''k.u.k. Kriegsmarine'', ) was the naval force of Austria-Hungary. Ships of the Austro-Hungarian Navy were designated ''SMS'', for '' Seiner Majestät Schiff'' (His Majesty's ...

.

This was triggered by the 8 September 1550 conquest of

Mahdiya by the Genoese Admiral

Andrea Doria

Andrea Doria, Prince of Melfi (; ; 30 November 146625 November 1560) was an Italian statesman, ', and admiral, who played a key role in the Republic of Genoa during his lifetime.

From 1528 until his death, Doria exercised a predominant influe ...

on behalf of

Charles V Charles V may refer to:

Kings and Emperors

* Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor (1500–1558)

* Charles V of Naples (1661–1700), better known as Charles II of Spain

* Charles V of France (1338–1380), called the Wise

Others

* Charles V, Duke ...

. The alliance allowed Henry II to push for French conquests towards the

Rhine

The Rhine ( ) is one of the List of rivers of Europe, major rivers in Europe. The river begins in the Swiss canton of Graubünden in the southeastern Swiss Alps. It forms part of the Swiss-Liechtenstein border, then part of the Austria–Swit ...

, while a Franco-Ottoman fleet defended southern France.

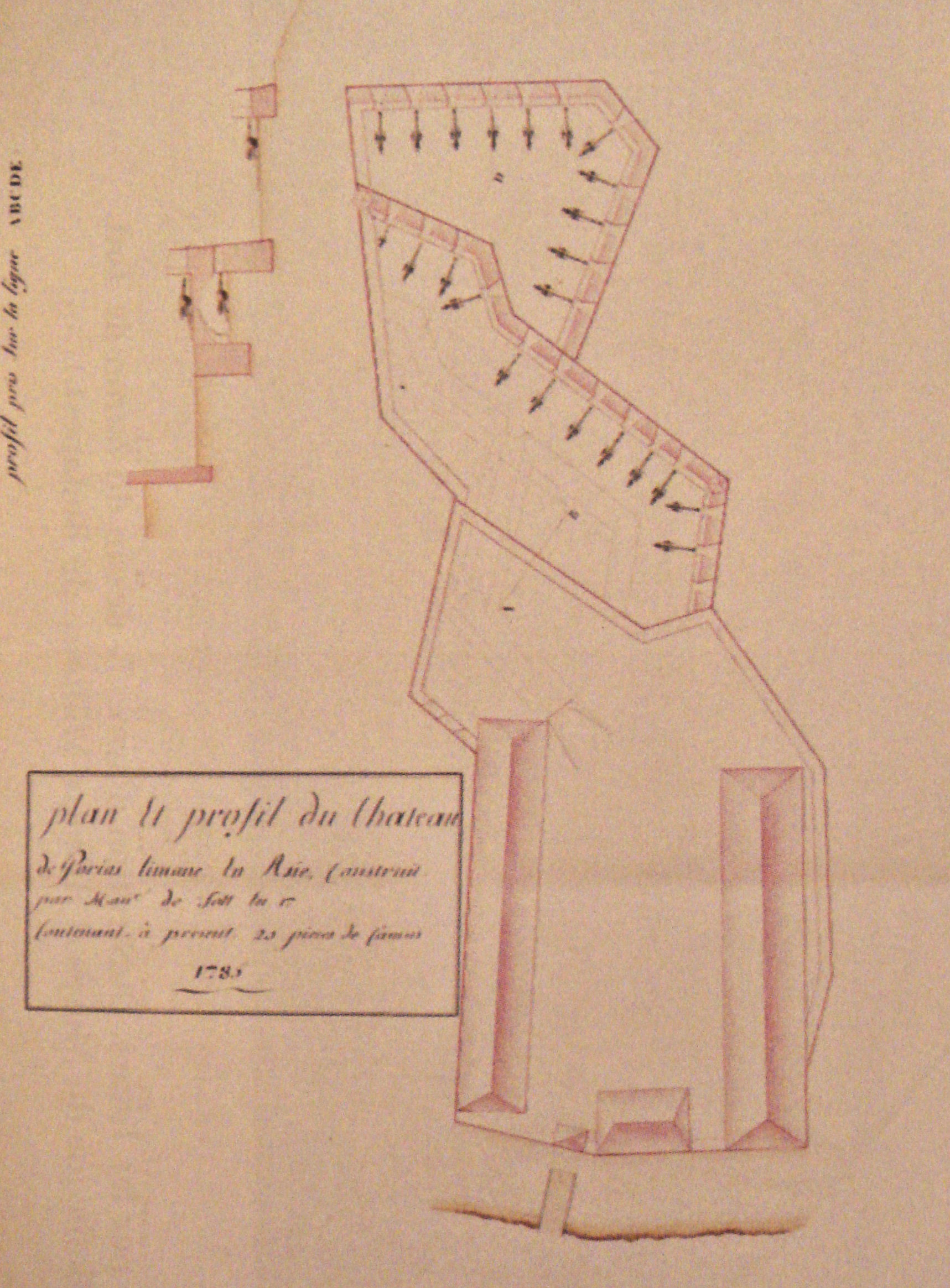

Cooperation during the Italian War of 1551–1559

Various military actions were coordinated during the

Italian War of 1551–1559

The Italian War of 1551–1559 began when Henry II of France declared war against Holy Roman Emperor Charles V with the intent of recapturing parts of Italy and ensuring French, rather than Habsburg, domination of European affairs. The war e ...

. In 1551, the Ottomans, accompanied by the French ambassador

Gabriel de Luez d'Aramon, succeeded in the

siege of Tripoli

The siege of Tripoli lasted from 1102 until 12 July 1109. It took place on the site of the present day Lebanese city of Tripoli, Lebanon, Tripoli, in the aftermath of the First Crusade. It led to the establishment of the fourth crusader state, t ...

.

Joint attacks on the Kingdom of Naples (1552)

In 1552, when Henry II attacked Charles V, the Ottomans sent 100 galleys to the Western Mediterranean. The Ottoman fleet was accompanied by three French galleys under Gabriel de Luez d'Aramon, who accompanied the Ottoman fleet from Istanbul in its raids along the coast of

Calabria

Calabria is a Regions of Italy, region in Southern Italy. It is a peninsula bordered by the region Basilicata to the north, the Ionian Sea to the east, the Strait of Messina to the southwest, which separates it from Sicily, and the Tyrrhenian S ...

in Southern Italy, capturing the city of

Reggio. The plan was to join with the French fleet of

Baron de la Garde

Antoine Escalin des Aimars (1516–1578), also known as Captain Polin or Captain Paulin, later Baron de La Garde, was French ambassador to the Ottoman Empire from 1541 to 1547, and ''"Général des Galères"'' ("General of the galleys") from 154 ...

and the troops of the

Prince of Salerno

This page is a list of the rulers of the Principality of Salerno.

Salerno was a Lombard Principality in southern Italy in the latter centuries of the first millenium.

When Prince Sicard of Benevento was assassinated by Radelchis I of Benevento, ...

, but both were delayed and could not join the Ottomans in time. In the

Battle of Ponza in front of the island of

Ponza

Ponza (Italian: ''isola di Ponza'' ) is the largest island of the Italy, Italian Pontine Islands archipelago, located south of Cape Circeo in the Tyrrhenian Sea. It is also the name of the commune of the island, a part of the province of Latina ...

with 40 galleys of

Andrea Doria

Andrea Doria, Prince of Melfi (; ; 30 November 146625 November 1560) was an Italian statesman, ', and admiral, who played a key role in the Republic of Genoa during his lifetime.

From 1528 until his death, Doria exercised a predominant influe ...

, the Franco-Ottoman fleet managed to vanquish them and capture 7 galleys on 5 August 1552. The Franco-Ottoman fleet left Naples to go back to the east on 10 August, missing the Baron de la Garde who reached Naples a week later with 25 galleys and troops. The Ottoman fleet then wintered in

Chios

Chios (; , traditionally known as Scio in English) is the fifth largest Greece, Greek list of islands of Greece, island, situated in the northern Aegean Sea, and the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, tenth largest island in the Medi ...

, where it was joined by the fleet of Baron de la Garde, ready for naval operations the following year.

Joint invasion of Corsica (1553)

On 1 February 1553, a new treaty of alliance, involving naval collaboration against the Habsburg was signed between France and the Ottoman Empire.

In 1553, the Ottoman admirals

Dragut

Dragut (; 1485 – 23 June 1565) was an Ottoman corsair, naval commander, governor, and noble. Under his command, the Ottoman Empire's maritime power was extended across North Africa. Recognized for his military genius, and as being among "the ...

and

Koca Sinan together with the French squadron raided the coasts of

Naples

Naples ( ; ; ) is the Regions of Italy, regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 908,082 within the city's administrative limits as of 2025, while its Metropolitan City of N ...

,

Sicily

Sicily (Italian language, Italian and ), officially the Sicilian Region (), is an island in the central Mediterranean Sea, south of the Italian Peninsula in continental Europe and is one of the 20 regions of Italy, regions of Italy. With 4. ...

,

Elba

Elba (, ; ) is a Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean island in Tuscany, Italy, from the coastal town of Piombino on the Italian mainland, and the largest island of the Tuscan Archipelago. It is also part of the Arcipelago Toscano National Park, a ...

and

Corsica

Corsica ( , , ; ; ) is an island in the Mediterranean Sea and one of the Regions of France, 18 regions of France. It is the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, fourth-largest island in the Mediterranean and lies southeast of the Metro ...

.

A Franco-Ottoman fleet accomplished an

Invasion of Corsica for the benefit of France.

The military alliance is said to have reached its peak in 1553.

In 1555, the French ambassador

Michel de Codignac, successor to Gabriel de Luetz d'Aramon, is known to have participated to Suleiman's

Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) and also known as Persia, is a country in West Asia. It borders Iraq to the west, Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Armenia to the northwest, the Caspian Sea to the north, Turkmenistan to the nort ...