Foreign Policy Of The Woodrow Wilson Administration on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The foreign policy under the

After his

After his  Meanwhile, Germany was trying to divert American attention from Europe by sparking a war. It sent Mexico the Zimmermann Telegram in January 1917, offering a military alliance to reclaim lands the United States had forcibly taken via conquest in the

Meanwhile, Germany was trying to divert American attention from Europe by sparking a war. It sent Mexico the Zimmermann Telegram in January 1917, offering a military alliance to reclaim lands the United States had forcibly taken via conquest in the

During World War I, both nations fought on the Allied side. With the cooperation of its ally Great Britain, Japan's military took control of German bases in China and the Pacific, and in 1919 after the war, with U.S. approval, was given a

During World War I, both nations fought on the Allied side. With the cooperation of its ally Great Britain, Japan's military took control of German bases in China and the Pacific, and in 1919 after the war, with U.S. approval, was given a

The Jones Law, or Philippine Autonomy Act, replaced the Organic Act as the constitution for the territory. Its preamble stated that the eventual independence of the Philippines would be American policy, subject to the establishment of a stable government. The law maintained an appointed governor-general, but established a bicameral Philippine Legislature and replaced the appointive Philippine Commission with an elected senate.

Filipino activists suspended the independence campaign during the World War and supported the United States and the

The Jones Law, or Philippine Autonomy Act, replaced the Organic Act as the constitution for the territory. Its preamble stated that the eventual independence of the Philippines would be American policy, subject to the establishment of a stable government. The law maintained an appointed governor-general, but established a bicameral Philippine Legislature and replaced the appointive Philippine Commission with an elected senate.

Filipino activists suspended the independence campaign during the World War and supported the United States and the

United States Senate The declaration passed in the House by a vote of 365 to 1. The US never declared war on Germany's other allies the

US State Department, Office of the Historian, "Home Milestones 1914-1920 The Paris Peace Conference and the Treaty of Versailles" (2017)

a U.S. government document that is not copyright.

excerpt

* Herring, George C. ''From Colony to Superpower: U.S. Foreign Relations since 1776'' (Oxford UP, 2008

online

textbook * Link, Arthur S. ''Woodrow Wilson and the Progressive Era, 1910–1917'' (1954), major scholarly surve

online

brief summary of Link biography vol 2-3-4-5 * Link, Arthur S. ''Wilson the Diplomatist: A Look at His Major Foreign Policies'' (1957

online

* Link, Arthur S. ed. ''Woodrow Wilson and a Revolutionary World, 1913–1921'' (1982). essays by 7 scholar

online

* Perkins, Bradford. ''The Great Rapprochement: England and the United States, 1895–1914'' (1968)

online

* Reed, James. ''The Missionary Mind and American East Asian Policy, 1911–1915'' (Harvard UP, 1983). * Robinson, Edgar Eugene, and Victor J. West. ''The Foreign Policy of Woodrow Wilson, 1913-1917'

online

useful survey with many copies of primary sources. * Smith, Tony. ''America's mission call in the United States and the worldwide struggle for democracy in the twentieth century'' (1994). *

online

* Cude, Michael R. ''Woodrow Wilson: The First World War and Modern Internationalism'' (Routledge, 2024). * * * Doenecke, Justus D. ''Nothing less than war: a new history of America's entry into World War I'' (UP of Kentucky, 2011). * Doerries, Reinhard R. ''Imperial Challenge: Ambassador Count Bernstorff and German-American Relations, 1908-1917'' (1989). * Epstein, Katherine C. “The Conundrum of American Power in the Age of World War I,” ''Modern American History'' (2019): 1-21. * Esposito, David M. ''The Legacy of Woodrow Wilson: American War Aims in World War I.'' (1996). * * Flanagan, Jason C. "Woodrow Wilson's" Rhetorical Restructuring": The Transformation of the American Self and the Construction of the German Enemy." ''Rhetoric & Public Affairs'' 7.2 (2004): 115-148

online

* Floyd, Ryan. ''Abandoning American Neutrality: Woodrow Wilson and the Beginning of the Great War, August 1914–December 1915'' (Springer, 2013). * Gilbert, Charles. ''American financing of World War I'' (1970

online

* * Horn, Martin. ''Britain, France, and the Financing of the First World War'' (2002), with details on US role * Kawamura, Noriko. ''Turbulence in the Pacific: Japanese-US Relations During World War I'' (Greenwood, 2000). * Kazin, Michael. ''War Against War: The American Fight for Peace, 1914-1918'' (2017). * Kennedy, Ross A. "Wilson's Wartime Diplomacy: The United States and the First World War, 1914–1918." in ''A Companion to US Foreign Relations: Colonial Era to the Present'' (2020): 304–324. * * * Levin Jr., N. Gordon. ''Woodrow Wilson and World Politics: America's Response to War and Revolution'' (Oxford UP, 1968), New Left approach. * * May, Ernest R. ''The World War and American isolation : 1914-1917'' (1959

online

a major scholarly study * Mayer, Arno J. ''Wilson vs. Lenin: Political Origins of the New Diplomacy 1917-1918'' (1969) * Safford, Jeffrey J. ''Wilsonian Maritime Diplomacy, 1913–1921.'' 1978. * Smith, Daniel M. ''The Great Departure: The United States in World War I, 1914-1920'' (1965). * Startt, James D. ''Woodrow Wilson, the Great War, and the Fourth Estate'' (Texas A&M UP, 2017) 420 pp. * Stevenson, David. ''The First World War and International Politics'' (1991), Covers the diplomacy of all the major powers. * * Trask, David F. ''The United States in the Supreme War Council: American War Aims and Inter-Allied Strategy, 1917-1918'' (1961) * Tooze, Adam. ''The Deluge: The Great War, America and the Remaking of the Global Order, 1916-1931'' (2014

audio

emphasis on economics * Tucker, Robert W. ''Woodrow Wilson and the Great War: Reconsidering America's Neutrality'' (U of Virginia Press, 2007). * Venzon, Anne ed. ''The United States in the First World War: An Encyclopedia'' (1995), Very thorough coverage. * Walworth, Arthur. ''America's moment, 1918: American diplomacy at the end of World War I'' (1977

online

* Woodward, David R. ''Trial by Friendship: Anglo-American Relations, 1917–1918 '' (1993). * * Young, Ernest William. ''The Wilson Administration and the Great War'' (1922

online edition

* Zahniser, Marvin R. ''Uncertain Friendship: American-French diplomatic relations through the Cold War'' (1975). pp 195–229. * ; als

C-SPAN interview

online

* Boghardt, Thomas. ''The Zimmermann telegram: intelligence, diplomacy, and America's entry into World War I'' (Naval Institute Press, 2012). * De Quesada, Alejandro. ''The Hunt for Pancho Villa: The Columbus Raid and Pershing's Punitive Expedition 1916–17'' (Bloomsbury, 2012). * Gardner, Lloyd C. ''Safe for democracy: the Anglo-American response to revolution, 1913-1923'' (Oxford UP, 1984). * Gilderhus, Mark T. ''Diplomacy and Revolution: US-Mexican Relations under Wilson and Carranza'' (1977)

online

* Haley, P. Edward. ''Revolution and Intervention: The Diplomacy of Taft and Wilson with Mexico, 1910-1917'' (MIT Press, 1970). * Hannigan, Robert E. ''The New World Power'' (U of Pennsylvania Press, 2013

excerpt

* Katz, Friedrich. ''The Secret War in Mexico: Europe, the United States, and the Mexican Revolution'' (1981)

online

* McPherson, Alan. ''A Short History of US Interventions in Latin America and the Caribbean''(John Wiley & Sons, 2016). * Neagle, Michael E. "A Bandit Worth Hunting: Pancho Villa and America's War on Terror in Mexico, 1916-1917." ''Terrorism and Political Violence'' 33.7 (2021): 1492–1510. * Quirk, Robert E. ''An affair of honor: Woodrow Wilson and the occupation of Veracruz'' (1962). on Mexic

online

* Sandos, James A. "Pancho Villa and American Security: Woodrow Wilson's Mexican Diplomacy Reconsidered" ''Journal of Latin American Studies'' 13#2 (1981): 293–311

online

* ** Sherman, David. "Barbara Tuchman's The Zimmermann Telegram: secrecy, memory, and history." ''Journal of Intelligence History'' 19.2 (2020): 125–148.

excerpt

* Clements, Kendrick A. ''William Jennings Bryan, missionary isolationist'' (U of Tennessee Press, 1982

online

focus on foreign policy. * Cooper, John Milton. ''Woodrow Wilson: A Biography'' (2009

online

major scholarly biography * Doerries, Reinhard R. ''Imperial Challenge: Ambassador Count Bernstorff and German-American Relations, 1908-1917'' (1989) * * * Graebner. Norman A. ed ''An Uncertain Tradition: American Secretaries of State in the Twentieth Century'' (1961) covers Bryan (pp 79–100) and Lansing (pp 101–127

online

*

online

* Hodgson, Godfrey. ''Woodrow Wilson's Right Hand: The Life of Colonel Edward M. House.'' (2006); short popular biograph

online

* Lazo, Dimitri D. "A question of Loyalty: Robert Lansing and the Treaty of Versailles." ''Diplomatic History'' 9.1 (1985): 35–53. * Link, Arthur Stanley. ''Wilson''

online

**''Wilson: The New Freedom'' vol 2 (1956) **''Wilson: The Struggle for Neutrality: 1914–1915'' vol 3 (1960) **''Wilson: Confusions and Crises: 1915–1916'' vol 4 (1964) **''Wilson: Campaigns for Progressivism and Peace: 1916–1917'' vol 5 (1965) * Neu, Charles E. ''Colonel House: A Biography of Woodrow Wilson's Silent Partner'' (Oxford UP, 2015), 699 pp * Neu, Charles E. ''The Wilson Circle: President Woodrow Wilson and His Advisers'' (2022) * O'Toole, Patricia. ''The Moralist: Woodrow Wilson and the World He Made'' (2018) * ; 904pp; full scale scholarly biography; winner of Pulitzer Prize

online free 2nd ed. 1965

* Walworth, Arthur. ''Wilson and His Peacemakers: American Diplomacy at the Paris Peace Conference, 1919'' (1986)

online

* Williams, Joyce Grigsby. ''Colonel House and Sir Edward Grey: A Study in Anglo-American Diplomacy'' (1984

online review

* Woolsey, Lester H. "Robert Lansing's Record as Secretary of State." ''Current History'' 29.3 (1928): 384–396

online

online

* Ambrosius, Lloyd E. "Wilson, the Republicans, and French Security after World War I." ''Journal of American History'' (1972): 341–352

Online

* Ambrosius, Lloyd E. "World War I and the Paradox of Wilsonianism." ''Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era'' 17.1 (2018): 5-22. * Ambrosius, Lloyd E. ''Wilsonian Statecraft: Theory and Practice of Liberal Internationalism During World War I'' (1991). * * Bacino, Leo C. ''Reconstructing Russia: US policy in revolutionary Russia, 1917-1922'' (Kent State UP, 1999

online

* Bailey, Thomas A. '' Woodrow Wilson and the Lost Peace'' (1963) on Paris, 191

online

* Bailey, Thomas A. ''Woodrow Wilson and the great betrayal'' (1945) on Senate defeat

conclusion-ch 22online

* Birdsall, Paul ''Versailles Twenty Years After'' (1941). * Canfield, Leon H. ''The Presidency of Woodrow Wilson; prelude to a world in crisis'' (1966

online

* Cooper, John Milton, Jr. ''Breaking the Heart of the World: Woodrow Wilson and the Fight for the League of Nations'' (2001)

online

* Curry, George. "Woodrow Wilson, Jan Smuts, and the Versailles Settlement." ''American Historical Review'' 66.4 (1961): 968–986

Online

* Duff, John B. "The Versailles Treaty and the Irish-Americans." ''Journal of American History'' 55.3 (1968): 582–598

Online

* Fifield, R H. ''Woodrow Wilson and the Far East: the diplomacy of the Shantung question'' (Thomas Y. Crowell, 1952). * Graebner, Norman A. and Edward M. Bennett, eds. ''The Versailles Treaty and Its Legacy: The Failure of the Wilsonian Vision'' (Cambridge UP, 2011). * Floto, Inga. ''Colonel House in Paris: A Study of American Policy at the Paris Peace Conference 1919'' (Princeton UP, 1980). * Foglesong, David S. "Policies toward Russia and intervention in the Russian revolution." in ''A Companion to Woodrow Wilson'' (2013): 386–405. * Greene, Theodore, ed. ''Wilson At Versailles'' (1949) short excerpts from scholarly studies

online free

* Ikenberry, G. John, Thomas J. Knock, Anne-Marie Slaughter, and Tony Smith. ''The Crisis of American Foreign Policy: Wilsonianism in the Twenty-first Century'' (Princeton UP, 2009

online

* Jianbiao, Ma. "“At Gethsemane”: The Shandong Decision at the Paris Peace Conference and Wilson's identity crisis." ''Chinese Studies in History'' 54.1 (2021): 45-62. * Kendall, Eric M. "Diverging Wilsonianisms: Liberal Internationalism, the Peace Movement, and the Ambiguous Legacy of Woodrow Wilson" (PhD. Dissertation, Case Western Reserve University, 2012)

online

354pp; with bibliography of primary and secondary sources pp 346–54. * Kennedy, Ross A. ''The will to believe: Woodrow Wilson, World War I, and America's strategy for peace and security'' (Kent State UP, 2008). * Knock, Thomas J. ''To End All Wars: Woodrow Wilson and the Quest for a New World Order'' (Princeton UP, 1992)

online

* Macmillan, Margaret. ''Paris 1919: Six Months That Changed the World'' (2001).

online

* Menchik, Jeremy. "Woodrow Wilson and the Spirit of Liberal Internationalism." ''Politics, Religion & Ideology'' (2021): 1-23. * Perlmutter, Amos. ''Making the world safe for democracy : a century of Wilsonianism and its totalitarian challengers'' (1997

online

* Pierce, Anne R. ''Woodrow Wilson & Harry Truman: Mission and Power in American Foreign Policy'' (Routledge, 2017). * * Roberts, Priscilla. "Wilson, Europe's Colonial Empires," in ''A Companion to Woodrow Wilson'' (2013): 492

online

* Smith, Tony. ''Why Wilson Matters: The Origin of American Liberal Internationalism and Its Crisis Today'' (Princeton University Press, 2017) * Smith, Tony. ''America's Mission: The United States and the Worldwide Struggle for Democracy'' (2nd ed. Princeton UP, 2012). * Stone, Ralph A. ed. ''Wilson and the League of Nations: why America's rejection?'' (1967) short excerpts from 15 historians. * Stone, Ralph A. ''The irreconcilables; the fight against the League of Nations'' (1970

online

* Tillman, Seth P. ''Anglo-American relations at the Paris Peace Conference of 1919'' (https://archive.org/details/angloamericanrel0000till) 961 online* Walworth, Arthur. ''Wilson and his Peacemakers: American Diplomacy at the Paris Peace Conference, 1919'' (WW Norton, 1986

online

* Wolff, Larry. ''Woodrow Wilson and the Reimagining of Eastern Europe'' (Stanford University Press, 2020

online review

* Wright, Esmond. "The Foreign Policy of Woodrow Wilson: A Re-Assessment. Part 2: Wilson and the Dream of Reason" ''History Today'' (Apr 1960) 19#4 pp 223–231

online

* Cooper, John Milton. "The World War and American Memory" ''Diplomatic History'' (2014) 38#4 pp 727–736

online

* Doenecke, Justus D. "American Diplomacy, Politics, Military Strategy, and Opinion‐Making, 1914–18: Recent Research and Fresh Assignments." ''Historian'' 80.3 (2018): 509–532. * Doenecke, Justus D. ''The Literature of Isolationism: A Guide to Non-Interventionist Scholarship, 1930-1972'' (R. Myles, 1972). * Doenecke, Justus D. ''Nothing Less Than War: A New History of America's Entry into World War I'' (2014) * Fordham, Benjamin O. "Revisionism reconsidered: exports and American intervention in World War I." ''International Organization'' 61#2 (2007): 277–310. * Gerwarth, Robert. "The Sky beyond Versailles: The Paris Peace Treaties in Recent Historiography." ''Journal of Modern History'' 93.4 (2021): 896-930. * * * Kennedy, Ross A. ed. ''A Companion to Woodrow Wilson '' (2013

coverage of major scholarly studies by experts * McKillen, Elizabeth. "Integrating labor into the narrative of Wilsonian internationalism: A literature review." ''Diplomatic History'' 34.4 (2010): 643–662. * * Saunders, Robert M. "History, Health and Herons: The Historiography of Woodrow Wilson's Personality and Decision-Making." Presidential Studies Quarterly (1994): 57–77

in JSTOR

* Sharp, Alan. ''Versailles 1919: A Centennial Perspective'' (Haus Publishing, 2018). * Showalter, Dennis. “The United States in the Great War: A Historiography.” ''OAH Magazine of History'' 17#1 (2002), pp. 5–13

online

* Steigerwald, David. "The Reclamation of Woodrow Wilson?" ''Diplomatic History'' 23.1 (1999): 79–99. pro-Wilso

online

* * Woodward. David. ''America and World War I: A Selected Annotated Bibliography'' of English Language Sources'' (2nd ed 2007

excerpt

* Zelikow, Philip, Niall Ferguson, Francis J. Gavin, Anne Karalekas, Daniel Sargent. "Forum 31 on the Importance of the Scholarship of Ernest May" ''H-DIPLO'' Dec. 17, 202

online

partly online; no charge to borrow

* Link. Arthur C., ed. ''The Papers of Woodrow Wilson.'' In 69 volumes. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press (1966–1994); a complete collection of Wilson's writing plus important letters written to him, plus detailed historical explanation. * Robinson, Edgar Eugene, and Victor J. West. ''The Foreign Policy of Woodrow Wilson, 1913-1917'

online

useful survey with copies and extracts from 90 primary sources * Seymour, Charles, ed. ''The intimate papers of Colonel House'' (4 vols., 1928

online

* Stark, Matthew J. "Wilson and the United States Entry into the Great War" ''OAH Magazine of History '' (2002) 17#1 pp. 40–47 lesson plan and primary sources for school project

online

''New International Year Book 1913'' (1914)

Comprehensive coverage of national and world affairs; strong on economics; 867pp

''New International Year Book 1914'' (1915)

Comprehensive coverage of national and world affairs, 913pp

''New International Year Book 1915'' (1916)

Comprehensive coverage of national and world affairs, 791pp

''New International Year Book 1916'' (1917)

Comprehensive coverage of national and world affairs, 938pp

''New International Year Book 1917'' (1918)

Comprehensive coverage of national and world affairs, 904 pp

''New International Year Book 1918'' (1919)

904 pp

''New International Year Book 1919'' (1920)

744pp

''New International Year Book 1920'' (1921)

844 pp

''New International Year Book 1921'' (1922)

848 pp

Extensive essay on Wilson and shorter essays on each member of his cabinet and First Lady from the Miller Center of Public Affairs

"Woodrow Wilson and Foreign Policy"-- Secondary school lesson plans from EDSITEment! program of National Endowment for the Humanities

excerpts from Wilson and Senator Lodge {{United States policy Wilson, Woodrow Wilson, Woodrow History of the foreign relations of the United States Progressive Era in the United States Wilson, Woodrow administration Woodrow Wilson

presidency of Woodrow Wilson

Woodrow Wilson served as the 28th president of the United States from March 4, 1913, to March 4, 1921. A Democrat and former governor of New Jersey, Wilson took office after winning the 1912 presidential election, where he defeated the Repu ...

deals with American diplomacy, and political, economic, military, and cultural relationships with the rest of the world from 1913 to 1921. Although Wilson had no experience in foreign policy, he made all the major decisions, usually with the top advisor Edward M. House

Edward Mandell House (July 26, 1858 – March 28, 1938) was an American diplomat, and an adviser to President Woodrow Wilson. He was known as Colonel House, although his title was honorary and he had performed no military service. He was a high ...

. His foreign policy was based on his messianic philosophical belief that America had the utmost obligation to spread its principles while reflecting the 'truisms' of American thought.

Wilson executed the Democratic Party foreign policy which since 1900 had, according to Arthur S. Link:consistently condemned militarism, imperialism, and interventionism in foreign policy. They instead advocated world involvement along liberal-internationalist lines. Wilson's appointment ofThe main foreign policy issues Wilson faced were civil war in neighboring Mexico; keeping out of World War I and protecting American neutral rights; deciding to enter and fight in 1917; and reorganizing world affairs with peace treaties and a League of Nations in 1919. Wilson had a physical collapse in late 1919 that left him too handicapped to closely supervise foreign or domestic policy.William Jennings Bryan William Jennings Bryan (March 19, 1860 – July 26, 1925) was an American lawyer, orator, and politician. He was a dominant force in the History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, running three times as the party' ...as Secretary of State indicated a new departure, for Bryan had long been the leading opponent of imperialism and militarism and a pioneer in the world peace movement.

Leadership

For advice and trouble shooting in foreign policy Wilson relied heavily on his trusted friend "Colonel"Edward M. House

Edward Mandell House (July 26, 1858 – March 28, 1938) was an American diplomat, and an adviser to President Woodrow Wilson. He was known as Colonel House, although his title was honorary and he had performed no military service. He was a high ...

. Wilson came to distrust House's independence in 1919, and ended all contact. After winning the presidency in the 1912 election, Wilson had no alternative choice for the premier cabinet position of Secretary of State. William Jennings Bryan

William Jennings Bryan (March 19, 1860 – July 26, 1925) was an American lawyer, orator, and politician. He was a dominant force in the History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, running three times as the party' ...

had long been the dominant leader of the Democratic Party and had been essential to Wilson's presidential nomination. Nevertheless, the president-elect was worried about Bryan's radical reputation, and especially about his independent base. Bryan had travelled the world giving speeches, promoting peace, and meeting with world leaders. Wilson had no such experience; he had studied English constitutional history in depth, but not its diplomatic history. He had not travelled widely outside the U.S. and Britain. Bryan proved very useful in helping pass major progressive domestic reforms through Congress, especially the Federal Reserve law. In foreign policy they worked together well at first. Bryan handled routine work and Wilson made the major decisions. Since Bryan had such a strong base in the Democratic Party, Wilson kept him informed, and allowed Bryan to pursue his own peace-priority of drafting 30 treaties with other countries that required both signatories to submit all disputes to an investigative tribunal. However he and Wilson clashed over U.S. neutrality in wartime. Bryan resigned in June 1915 after Wilson sent to Berlin a note of protest in response to the Sinking of the RMS Lusitania

was a British-registered ocean liner that was torpedoed by an Imperial German Navy U-boat during the First World War on 7 May 1915, about off the Old Head of Kinsale, Ireland. The attack took place in the declared maritime war-zone around t ...

, a British passenger liner, by a German U-boat

U-boats are Submarine#Military, naval submarines operated by Germany, including during the World War I, First and Second World Wars. The term is an Anglicization#Loanwords, anglicized form of the German word , a shortening of (), though the G ...

, with the death of 128 Americans. Bryan thought they travelled at their own risk into a war zone, while Wilson considered it was a violation of the laws of war to sink a passenger ship without giving the passengers a chance to reach the lifeboats.

Wilson selected Robert Lansing

Robert Lansing (; October 17, 1864 – October 30, 1928) was an American lawyer and diplomat who served as the 42nd United States Secretary of State under President Woodrow Wilson from 1915 to 1920. As Counselor to the State Department and then a ...

to replace Bryan because he was proficient in routine work and passive in ideas and initiative. Unlike Bryan he lacked a political base. The result was that Wilson could be—and indeed actually was—freer to personally make all major foreign policy decisions. John Milton Cooper concludes that it was one of Wilson's worst mistakes as president. Wilson told Colonel House

Edward Mandell House (July 26, 1858 – March 28, 1938) was an American diplomat, and an adviser to President Woodrow Wilson. He was known as Colonel House, although his title was honorary and he had performed no military service. He was a high ...

that as president he would practically be his own Secretary of State, and "Lansing would not be troublesome by uprooting or injecting his own views."

Lansing advocated "benevolent neutrality

A neutral country is a state that is neutral towards belligerents in a specific war or holds itself as permanently neutral in all future conflicts (including avoiding entering into military alliances such as NATO, CSTO or the SCO). As a type o ...

" at the start of the war, but shifted away from the ideal after increasing interference and violation of the rights of neutrals by Great Britain. According to Lester H. Woolsey, a top aide in the State Department and later Lansing's law partner, Lansing by mid-1915 had very strong views against Germany. He kept these to himself because Wilson disagreed. Lansing expressed his views by manipulating the work of the State Department to minimize conflict with Britain and maximize public awareness of Germany's faults. Woolsey states:Although the President cherished the hope that the United States would not be drawn into the war, and while this was the belief of many officials, Mr. Lansing early in July, 1915, came to the conclusion that the German ambition for world domination was the real menace of the war, particularly to democratic institutions. In order to block this German ambition, he believed that the progress of the war would eventually disclose to the American people the purposes of the German Government; that German activities in the United States and in Latin America should be carefully investigated and frustrated; that the American republics to the south should be weaned from the German influences; that friendly relations with Mexico should be maintained even to the extent of recognizing the Carranza faction; that the Danish West Indies should be acquired in order to remove the possibility of Germany's obtaining a foothold in the Caribbean by conquest of Denmark or otherwise; that the United States should enter the war if it should appear that Germany would become the victor; and that American public opinion must be awakened in preparation for this contingency. This outline of Mr. Lansing's views explains why the Lusitania dispute was not brought to the point of a break. It also explains why, though Americans were incensed at the British interference with commerce, the controversy was kept within the arena of debate.The two key Allied ambassadors were

Cecil Spring Rice

Sir Cecil Arthur Spring Rice, (27 February 1859 – 14 February 1918) was a British diplomat who served as British Ambassador to the United States from 1912 to 1918, as which he was responsible for the organisation of British efforts to end ...

for Britain and Jean Jules Jusserand

Jean Adrien Antoine Jules Jusserand (18 February 1855 – 18 July 1932) was a French author and diplomat. He was the French Ambassador to the United States 1903-1925 and played a major diplomatic role during World War I.

Birth and education

...

for France. The latter was highly successful, achieving popularity with Americans from many backgrounds and perspectives. However Spring-Rice was a close friend of Wilson's enemies Theodore Roosevelt and Henry Cabot Lodge, and never was comfortable in the Wilsonian milieu. Wilson distrusted Spring-Rice as incompetent and a mischief-maker. House solved the problem by a close friendship with Sir William Wiseman, a British banker who took charge of financial negotiations as well as intelligence operations. Johann Heinrich von Bernstorff

Johann Heinrich Graf von Bernstorff (14 November 1862 – 6 October 1939) was a German politician and German Ambassador to the United States, ambassador to the United States from 1908 to 1917.

Early life

Born in 1862 in London, he was the so ...

was the German ambassador—suave and sophisticated. He tried and failed to get Berlin to accept Wilson's proposals for peace plans. Meanwhile, he was organizing propaganda activities. However, after the war he denied any involvement with sabotage activities to disrupt the shipment of American supplies to the Allies, such as the monster Black Tom explosion

The Black Tom explosion was an act of arson by field agents of the Office of Naval Intelligence of the German Empire, to destroy U.S.-made munitions that were about to be shipped to the Allies during World War I. The explosions occurred on Ju ...

in 1916.

Latin America

American foreign policy under Wilson marked a departure from President Taft's "Dollar Diplomacy." Wilson wished to correct the American errors of the nineteenth century. Instead, Wilson desired to extend American friendship to the nations of Latin America. In his 1913 Address Before the Southern Commercial Congress, Wilson states:In emphasizing the points which must unite us in sympathy and in spiritual interest with the Latin-American peoples we are only emphasizing the points of our own life, and we should prove ourselves untrue to our own traditions if we proved ourselves untrue friends to them. Do not think, therefore, gentlemen, that the questions of the day are mere questions of policy and diplomacy. They are shot through with the principles of life. We dare not turn from the principle that morality and not expediency is the thing that must guide us and that we will never condone iniquity because it is most convenient to do so.Wilson believed that America ought to conduct itself morally and in accordance with its own traditions rather than operating exclusively out of American interest. Wilson was willing to exert American power to attempt to change or influence Latin American nations' internal politics, such as when he withheld recognition of Mexican President Huerta's administration. Wilson, however, justified his lack of recognition on moral grounds since Huerta had seized power in a coup. Wilson believed resisting recognition would force Huerta to allow for free elections. Thus Wilson placed a high importance on conducting American foreign policy for moral ends.

Panama Canal

ThePanama Canal

The Panama Canal () is an artificial waterway in Panama that connects the Caribbean Sea with the Pacific Ocean. It cuts across the narrowest point of the Isthmus of Panama, and is a Channel (geography), conduit for maritime trade between th ...

opened in 1914, just after the start of World War 1. It fulfilled the long-term dream of building a canal across Central America and making possible quick movement between the Atlantic and the Pacific.. For the US Navy the canal allowed quick movement of fleets between the Pacific and the Atlantic. Economically it opened new opportunities to the shippers to reach the Far East. Britain insisted that treaty agreements meant its ships would pay the same toll as American ships, and Congress agreed to the same tolls for every nation.

To further protect the Canal, in 1917, the US purchased the strategically located Danish West Indies

The Danish West Indies () or Danish Virgin Islands () or Danish Antilles were a Danish colony in the Caribbean, consisting of the islands of Saint Thomas with , Saint John () with , Saint Croix with , and Water Island.

The islands of St ...

for $25 million, in gold, from Denmark

Denmark is a Nordic countries, Nordic country in Northern Europe. It is the metropole and most populous constituent of the Kingdom of Denmark,, . also known as the Danish Realm, a constitutionally unitary state that includes the Autonomous a ...

. The territory was renamed the United States Virgin Islands

The United States Virgin Islands, officially the Virgin Islands of the United States, are a group of Caribbean islands and a territory of the United States. The islands are geographically part of the Virgin Islands archipelago and are located ...

. Its population of 27,000 was over 90 per cent Black; its economy was based on sugar.

Mexico

Washington had long recognized the dictatorial government ofPorfirio Díaz

José de la Cruz Porfirio Díaz Mori (; ; 15 September 1830 – 2 July 1915) was a General (Mexico), Mexican general and politician who was the dictator of Mexico from 1876 until Mexican Revolution, his overthrow in 1911 seizing power in a Plan ...

. As Díaz approached eighty years old, he announced he was not going to run in the scheduled 1910 elections. This set off a flurry of political activity about presidential succession. Washington wanted any new president to continue Díaz's policies that had been favorable to American mining and oil interests and produced stability domestically and internationally. However Díaz suddenly reneged on his promise not to run, exiled General Bernardo Reyes

Bernardo Doroteo Reyes Ogazón (30 August 1850 – 9 February 1913) was a Mexican general and politician who fought in the Second French intervention in Mexico and served as the appointed Governor of Nuevo León for more than two decades dur ...

, the most viable candidate. He had the most popular opposition candidate, Francisco I. Madero

Francisco Ignacio Madero González (; 30 October 1873 – 22 February 1913) was a Mexican businessman, revolutionary, writer and statesman, who served as the 37th president of Mexico from 1911 until he was deposed in a coup d'état in Februa ...

jailed. After the rigged 1910 reelection of Diaz, political unrest became open rebellion.

After his

After his Federal Army

The Federal Army (), also known as the Federales () in popular culture, was the army of Mexico from 1876 to 1914 during the Porfiriato, the rule of President Porfirio Díaz, and during the presidencies of Francisco I. Madero and Victoriano Huerta. ...

failed to suppress the insurgents, Díaz resigned and went into exile. An interim government was installed, and new elections were held in October 1911. These were won by Madero. Initially, Washington was optimistic about Madero. He had disbanded the rebel forces that had forced Díaz to resign; retain the Federal Army; and appeared to be open to friendly policies. However the U.S. began to sour on the relationship with Madero and began actively working with opponents to the regime. The new president Victoriano Huerta

José Victoriano Huerta Márquez (; 23 December 1850 – 13 January 1916) was a Mexican general, politician, engineer and dictator who was the 39th President of Mexico, who came to power by coup against the democratically elected government of ...

won recognition from all major countries except the U.S. Wilson, who took office shortly after Madero's assassination, rejected the legitimacy of Huerta's "government of butchers" and demanded that Mexico hold democratic elections to replace him. In the Tampico Affair

The Tampico Affair began as a minor incident involving United States Navy sailors and the Mexican Federal Army loyal to Mexican dictator General Victoriano Huerta. On April 9, 1914, nine sailors had come ashore to secure supplies and were detai ...

of April 9, 1914 nine American sailors were seized for about an hour by Huerta's soldiers. The local commander apologized and released the sailors but refused the demand of the American admiral to salute the U.S. flag and punish the arrested officer. The conflict escalated with Washington's approval and the U.S. Navy seized Veracruz. Some 170 Mexican soldiers and an unknown number of Mexican civilians were killed in the takeover, as well as 22 Americans.

Pancho Villa

Francisco "Pancho" Villa ( , , ; born José Doroteo Arango Arámbula; 5 June 1878 – 20 July 1923) was a Mexican revolutionary and prominent figure in the Mexican Revolution. He was a key figure in the revolutionary movement that forced ...

(1878–1923), a local bandit who built up a regional base, became a major national figure when he led anti-Huerta forces in the Constitutionalist Army

The Constitutional Army (), also known as the Constitutionalist Army (), was the army that fought against the Federal Army, and later, against the Villistas and Zapatistas during the Mexican Revolution. It was formed in March 1913 by Venustia ...

1913–14. At the height of his power and popularity in late 1914 and early 1915, Washington considered recognizing him as Mexico's legitimate authority. However Villa was decisively defeated by Constitutionalist General Alvaro Obregón in summer 1915, and the U.S. aided Constitutionalist leader Venustiano Carranza

José Venustiano Carranza de la Garza (; 29 December 1859 – 21 May 1920), known as Venustiano Carranza, was a Mexican land owner and politician who served as President of Mexico from 1917 until his assassination in 1920, during the Mexican Re ...

directly against Villa. Villa, much weakened, conducted a raid on the small border village of Columbus, New Mexico

Columbus is an incorporated village in Luna County, New Mexico, United States, about north of the Mexican border. It is considered a place of historical interest, as the scene of a 1916 attack by Mexican general Francisco "Pancho" Villa that ...

killing 18 Americans. His goal was to goad Wilson into a war with Carranza. Instead Wilson sent the Army on a limited punitive expedition led by General John J. Pershing

General of the Armies John Joseph Pershing (September 13, 1860 – July 15, 1948), nicknamed "Black Jack", was an American army general, educator, and founder of the Pershing Rifles. He served as the commander of the American Expeditionary For ...

deep into Mexico. It failed to capture Villa. Mexican public and elite opinion turned strongly against the U.S. and war was growing more and more likely. Wilson realized that escalating tensions with Germany were much more important and recalled the invasion force in early 1917 as war with Germany approached.

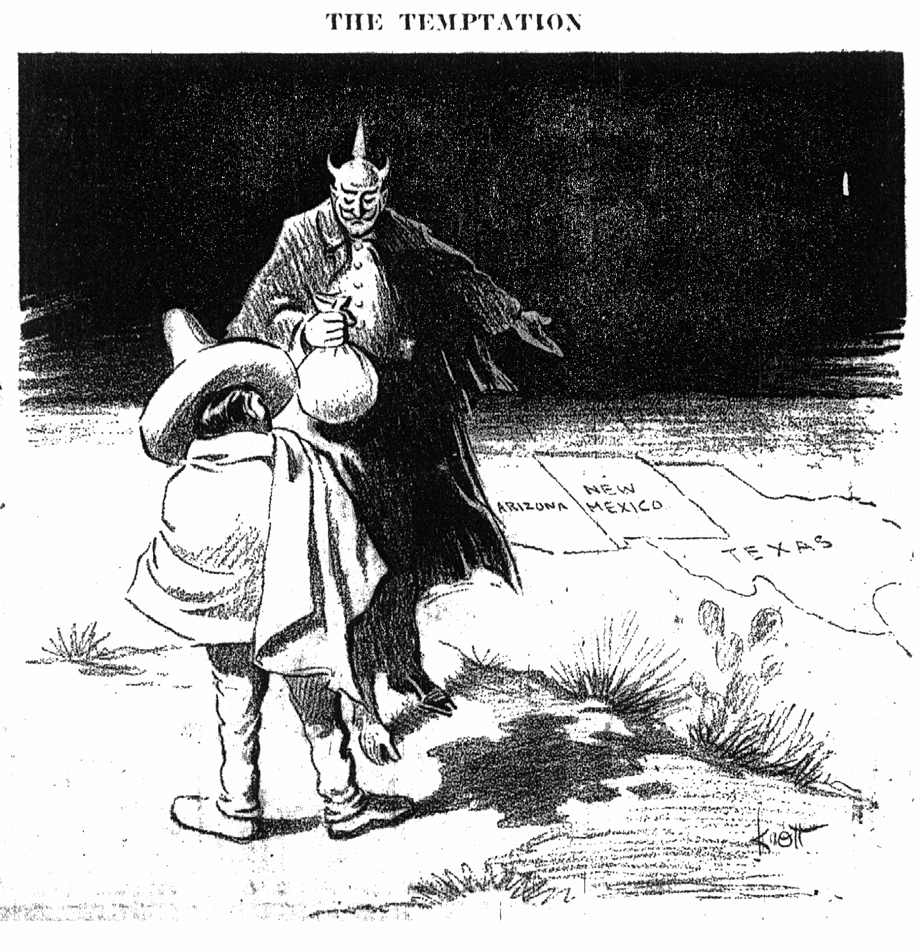

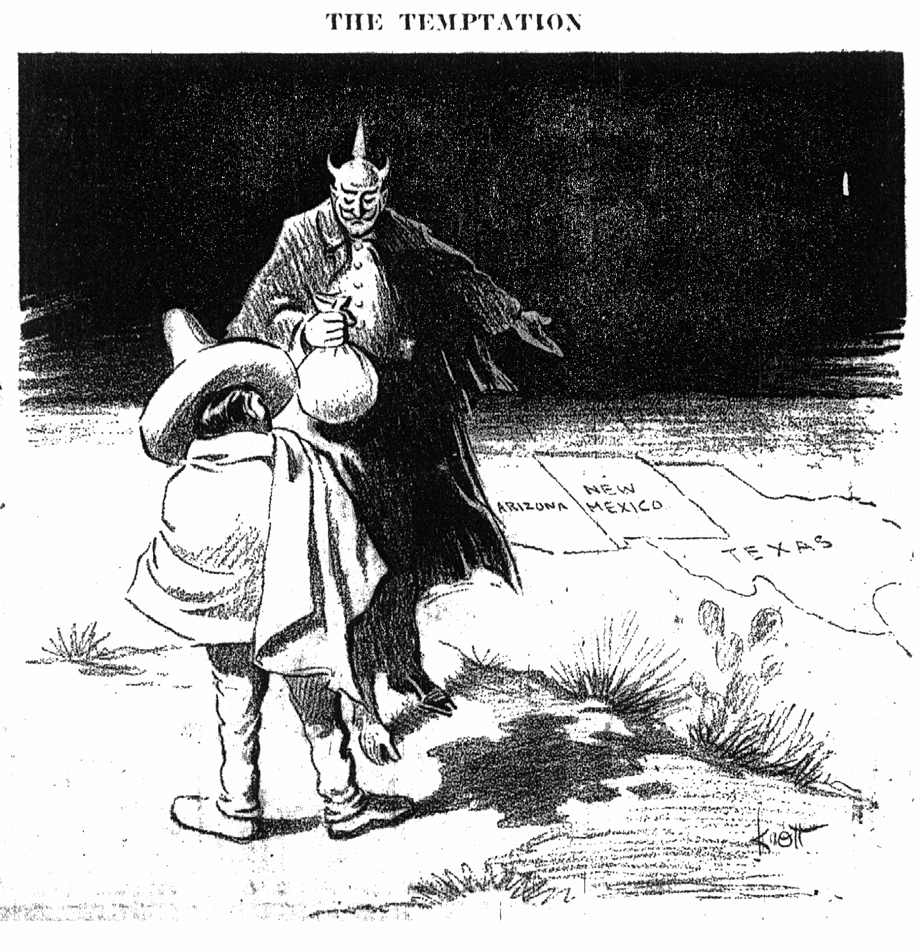

Meanwhile, Germany was trying to divert American attention from Europe by sparking a war. It sent Mexico the Zimmermann Telegram in January 1917, offering a military alliance to reclaim lands the United States had forcibly taken via conquest in the

Meanwhile, Germany was trying to divert American attention from Europe by sparking a war. It sent Mexico the Zimmermann Telegram in January 1917, offering a military alliance to reclaim lands the United States had forcibly taken via conquest in the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War (Spanish language, Spanish: ''guerra de Estados Unidos-México, guerra mexicano-estadounidense''), also known in the United States as the Mexican War, and in Mexico as the United States intervention in Mexico, ...

. British intelligence intercepted the message, and revealed it to the American government when tensions were high. Wilson released it to the press, escalating demands for American war against Germany. The Mexican government rejected the proposal after its military warned of massive defeat if they attempted to follow through with the plan. Mexico stayed neutral; selling large amounts of oil to Britain for the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

.

Nicaragua

According to Benjamin Harrison, Wilson was committed in Latin America to the fostering of democracy and stable governments, as well as fair economic policies. Wilson was largely frustrated by the chaotic situation in Nicaragua.Adolfo Díaz

Adolfo Díaz Recinos (15 July 1875 in Alajuela, Costa Rica – 29 January 1964 in San José, Costa Rica) served as the President of Nicaragua between 9 May 1911 and 1 January 1917 and again between 14 November 1926 and 1 January 1929. Born in C ...

won the presidency in 1911 and replaced European financing with loans from New York banks. Facing a Liberal rebellion, he called on the United States for protection and Wilson obliged. Nicaragua assumed a quasi-protectorate

A protectorate, in the context of international relations, is a State (polity), state that is under protection by another state for defence against aggression and other violations of law. It is a dependent territory that enjoys autonomy over ...

status under the 1916 Bryan–Chamorro Treaty

The Bryan–Chamorro Treaty was signed between Nicaragua and the United States on August 5, 1914. It gave the United States full rights over any future canal built through Nicaragua. The Wilson administration changed the treaty by adding a provis ...

. Under the treaty Nicaragua promised it would not declare war on anyone, would not grant territorial concessions, and would not contract outside debts without Washington's approval. It permitted the US to build a naval base at Fonseca Bay, and gave the US the sole option to construct and control an inter-oceanic canal. The US had no intention of building a canal, but one of the guarantee that no other nation could do so. The US paid Nicaragua $3 million for this option. The original draft also asserted the duty of the United States to intervene militarily in case of domestic turmoil – but that provision was rejected by Democrats in the Senate. The treaty was extremely unpopular in the Caribbean region, but it was observed by both sides until 1933. Díaz was now able to serve out his entire term; he retired in 1917, and moved to the United States, though he briefly returned to power in 1926–1929. According to George Baker, the main effect of the treaty was a higher degree of both political and financial stability in Nicaragua. President Herbert Hoover

Herbert Clark Hoover (August 10, 1874 – October 20, 1964) was the 31st president of the United States, serving from 1929 to 1933. A wealthy mining engineer before his presidency, Hoover led the wartime Commission for Relief in Belgium and ...

(1929-1933) opposed the relationship. Finally in 1933, President Franklin D Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), also known as FDR, was the 32nd president of the United States, serving from 1933 until his death in 1945. He is the longest-serving U.S. president, and the only one to have served ...

invoked his new Good Neighbor policy to end American intervention.

Asia

China

After theXinhai Revolution

The 1911 Revolution, also known as the Xinhai Revolution or Hsinhai Revolution, ended China's last imperial dynasty, the Qing dynasty, and led to the establishment of the Republic of China (ROC). The revolution was the culmination of a decade ...

overthrew the emperor in 1911, The Taft administration recognized the new Government of the Chinese Republic

The Beiyang government was the internationally recognized government of the Republic of China (1912–1949), Republic of China between 1912 and 1928, based in Beijing. It was dominated by the generals of the Beiyang Army, giving it its name.

B ...

as the legitimate government of China. In practice a number of powerful regional warlords were in control and the central government handled foreign policy and little else.

The ''Twenty-One Demands

The Twenty-One Demands (; ) was a set of demands made during the World War I, First World War by the Empire of Japan under Prime Minister of Japan, Prime Minister Ōkuma Shigenobu to the Government of the Chinese Republic, government of the Re ...

'' were a set of secret demands made in 1915 by Japan to Yuan Shikai

Yuan Shikai (; 16 September 18596 June 1916) was a Chinese general and statesman who served as the second provisional president and the first official president of the Republic of China, head of the Beiyang government from 1912 to 1916 and ...

the general who served as president of the Republic of China

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia. The main geography of Taiwan, island of Taiwan, also known as ''Formosa'', lies between the East China Sea, East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocea ...

The demands would greatly extend Japanese control. Japan would keep the former German concessions it had conquered at the start of World War I in 1914. Japan would be stronger in Manchuria

Manchuria is a historical region in northeast Asia encompassing the entirety of present-day northeast China and parts of the modern-day Russian Far East south of the Uda (Khabarovsk Krai), Uda River and the Tukuringra-Dzhagdy Ranges. The exact ...

and South Mongolia. It would have an expanded role in railways. The most extreme demands—the fifth set—would gave Japan a decisive voice in China's finance, policing, and government affairs. Indeed, they would make China in effect a protectorate of Japan, and thereby reduce Western influence. Japan was in a strong position, as the Western powers were in a stalemated war with Germany. Britain and Japan had a military alliance since 1902, and in 1914 London had asked Tokyo to enter the war. Beijing published the secret demands and appealed to Washington and London. They were sympathetic and pressured Tokyo. In the final 1916 settlement, Japan gave up its fifth set of demands. It gained a little in China, but lost a great deal of prestige in Washington and London.Bruce Elleman, ''Wilson and China: A Revised History of the Shandong Question'' (Routledge, 2015). E. T. Williams, the senior expert on the Far East in the State Department, argued in January 1915:

:Our present commercial interests in Japan are greater than those in China, but the look ahead shows ''our interest'' to be ''a strong and independent China'' rather than one held in subjection by Japan. China has certain claims upon our sympathy. If we do not recognize them...we are in danger of ''losing our influence in the Far East'' and of adding to the dangers of the situation.

Wilson has been criticized for accepting at the Paris Peace Conference the transfer of the German concession in Shandong to Japan, instead of allowing China to reclaim it. However Bruce Elleman has argued that Wilson did not betray China because his action was in accord with widely recognized treaties which China had signed with Japan during the war. Wilson tried to get Japan to promise to return the concessions in 1922, but the Chinese delegation rejected that compromise. The result in China was the growth of intense nationalism characterized by the May Fourth Movement

The May Fourth Movement was a Chinese cultural and anti-imperialist political movement which grew out of student protests in Beijing on May 4, 1919. Students gathered in front of Tiananmen to protest the Chinese government's weak response ...

, and the tendency of intellectuals and activists in the 1920s to look to Moscow for leadership.

Wilson was in touch with several former Princeton students who were missionaries in China, and he strongly endorsed their work. In 1916 he told a delegation of ministers:This is the most amazing and inspiring vision - this vision of that great sleeping nation suddenly awakened by the voice of Christ. Could there be any greater contribution to the future momentum of the moral forces of the world than could be made by quickening the force, which is being set of foot in China? China is at present inchoate; as a nation it is a congeries of parts, in each of which there is energy, but which are unbound in any essential and active unit, and just as soon as unity comes, its power will come in the world.

Japan

In 1913, California enacted theCalifornia Alien Land Law of 1913

The California Alien Land Law of 1913 (also known as the Webb–Haney Act) prohibited "aliens ineligible for citizenship" from owning agricultural land or possessing long-term leases over it, but permitted leases lasting up to three years. It affe ...

to exclude resident Japanese non-citizens from owning any land in the state. Tokyo protested strongly, and Wilson sent Bryan to California to mediate. Bryan was unable to get California to relax the restrictions, and Wilson accepted the law even though it violated a 1911 treaty with Japan. The law bred resentment in Japan which lingered into the 1920s and 1930s.

During World War I, both nations fought on the Allied side. With the cooperation of its ally Great Britain, Japan's military took control of German bases in China and the Pacific, and in 1919 after the war, with U.S. approval, was given a

During World War I, both nations fought on the Allied side. With the cooperation of its ally Great Britain, Japan's military took control of German bases in China and the Pacific, and in 1919 after the war, with U.S. approval, was given a League of Nations

The League of Nations (LN or LoN; , SdN) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920), Paris Peace ...

mandate over the German islands north of the equator, with Australia getting the rest. The U.S. did not want any mandates.

Japan's aggressive approach in its dealings with China, however, was a continual source of tensionindeed eventually leading to World War II between the two nations. Trouble arose between Japan on the one hand and China, Britain and the U.S. on the other over Japan's Twenty-One Demands

The Twenty-One Demands (; ) was a set of demands made during the World War I, First World War by the Empire of Japan under Prime Minister of Japan, Prime Minister Ōkuma Shigenobu to the Government of the Chinese Republic, government of the Re ...

made on China in 1915. These demands forced China to acknowledge Japanese possession of the former German holdings and its economic dominance of Manchuria, and had the potential of turning China into a puppet state. Washington expressed strongly negative reactions to Japan's rejection of the Open Door Policy. In the Bryan Note issued by Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan

William Jennings Bryan (March 19, 1860 – July 26, 1925) was an American lawyer, orator, and politician. He was a dominant force in the History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, running three times as the party' ...

on March 13, 1915, the U.S., while affirming Japan's "special interests" in Manchuria, Mongolia and Shandong, expressed concern over further encroachments to Chinese sovereignty.

In 1917 the Lansing–Ishii Agreement

The was a diplomatic note signed in Washington between the United States and Imperial Japan on 2 November 1917 over their disputes with regards to China. Both parties agreed to respect the independence and territorial integrity of China and to f ...

was negotiated. Secretary of State Robert Lansing

Robert Lansing (; October 17, 1864 – October 30, 1928) was an American lawyer and diplomat who served as the 42nd United States Secretary of State under President Woodrow Wilson from 1915 to 1920. As Counselor to the State Department and then a ...

specified American acceptance that Manchuria was under Japanese control, while still nominally under Chinese sovereignty. Japanese Foreign Minister Ishii Kikujiro noted Japanese agreement not to limit American commercial opportunities elsewhere in China. The agreement also stated that neither would take advantage of the war in Europe to seek additional rights and privileges in Asia.

At the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, Japan insisted that Germany's concessions in China, especially in the Shandong Peninsula

The Shandong Peninsula or Jiaodong (tsiaotung) Peninsula is a peninsula in Shandong in eastern China, between the Bohai Sea to the north and the Yellow Sea to the south. The latter name refers to the east and Jiaozhou.

Geography

The waters ...

, be transferred to Japan. President Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was the 28th president of the United States, serving from 1913 to 1921. He was the only History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democrat to serve as president during the Prog ...

fought vigorously against Japan's demands regarding China, but backed down upon realizing the Japanese delegation had widespread support. In China there was outrage and anti-Japanese sentiment

Anti-Japanese sentiment (also called Japanophobia, Nipponophobia and anti-Japanism) is the fear or dislike of Japan or Japanese culture. Anti-Japanese sentiment can take many forms, from antipathy toward Japan as a country to racist hatr ...

escalated. The May Fourth Movement

The May Fourth Movement was a Chinese cultural and anti-imperialist political movement which grew out of student protests in Beijing on May 4, 1919. Students gathered in front of Tiananmen to protest the Chinese government's weak response ...

emerged as a student demand for China's honor. In 1922 the U.S. brokered a solution of the Shandong Problem

The Shandong Problem or Shandong Question (; ) was a dispute over Article 156 of the Treaty of Versailles in 1919, which dealt with the concession of the Shandong Peninsula. It was resolved in China's favor in 1922.

The German Empire acquired ...

. China was awarded nominal sovereignty over all of Shandong, including the former German holdings, while in practice Japan's economic dominance continued.

Philippines

The Democratic party in the United States had strongly opposed acquisitions of the Philippines in the first place, and increasingly became committed to independence. Wilson himself was a conservative in the 1890s and supported McKinley's foreign policy and favored annexation of the Philippines. The election of a Democratic president and Congress in 1912 opened up opportunities and Wilson had changed. He now wanted the islands to be governed by Filipinos until it became independent. He appointedFrancis Burton Harrison

Francis Burton Harrison (December 18, 1873 – November 21, 1957) was an American-Filipino Politics of the United States, statesman who served in the United States House of Representatives and was appointed Governor-General of the Philippines ...

as governor, and Harrison replaced nearly all the mainlanders with Filipinos in the bureaucracy. By 1921, of the 13,757 bureaucrats, 13,143 were Filipinos; they held 56 of the top 69 positions.

Philippine nationalists led by Manuel L. Quezon

Manuel Luis Quezon y Molina (, , , ; 19 August 1878 – 1 August 1944), also known by his initials MLQ, was a Filipino people, Filipino lawyer, statesman, soldier, and politician who was president of the Commonwealth of the Philippines from 1 ...

and Sergio Osmeña

Sergio Osmeña Sr. (, ; zh, c=吳文釗, poj=Gô͘ Bûn-chiau; September 9, 1878 – October 19, 1961) was a Filipino people, Filipino lawyer and politician who served as the List of presidents of the Philippines, fourth president of the Ph ...

enthusiastically endorsed the draft Jones Bill of 1912, which provided for Philippine independence

The Philippines, officially the Republic of the Philippines, is an Archipelagic state, archipelagic country in Southeast Asia. Located in the western Pacific Ocean, it consists of List of islands of the Philippines, 7,641 islands, with a tot ...

after eight years, but later changed their views, opting for a bill which focused less on time than on the conditions of independence. The nationalists demanded complete and absolute independence to be guaranteed by the United States, since they feared that too-rapid independence from American rule without such guarantees might cause the Philippines to fall into Japanese hands. The Jones Bill was rewritten and passed a Congress controlled by Democrats in 1916 with a later date of independence.

The Jones Law, or Philippine Autonomy Act, replaced the Organic Act as the constitution for the territory. Its preamble stated that the eventual independence of the Philippines would be American policy, subject to the establishment of a stable government. The law maintained an appointed governor-general, but established a bicameral Philippine Legislature and replaced the appointive Philippine Commission with an elected senate.

Filipino activists suspended the independence campaign during the World War and supported the United States and the

The Jones Law, or Philippine Autonomy Act, replaced the Organic Act as the constitution for the territory. Its preamble stated that the eventual independence of the Philippines would be American policy, subject to the establishment of a stable government. The law maintained an appointed governor-general, but established a bicameral Philippine Legislature and replaced the appointive Philippine Commission with an elected senate.

Filipino activists suspended the independence campaign during the World War and supported the United States and the Allies of World War I

The Allies or the Entente (, ) was an international military coalition of countries led by the French Republic, the United Kingdom, the Russian Empire, the United States, the Kingdom of Italy, and the Empire of Japan against the Central Powers ...

against the German Empire

The German Empire (),; ; World Book, Inc. ''The World Book dictionary, Volume 1''. World Book, Inc., 2003. p. 572. States that Deutsches Reich translates as "German Realm" and was a former official name of Germany. also referred to as Imperia ...

. After the war they resumed their independence drive with great vigour. In 1919, the Philippine Legislature passed a "Declaration of Purposes", which stated the inflexible desire of the Filipino people to be free and sovereign. A Commission of Independence was created to study ways and means of attaining liberation ideal. This commission recommended the sending of an independence mission to the United States. The "Declaration of Purposes" referred to the Jones Law as a veritable pact, or covenant, between the American and Filipino peoples whereby the United States promised to recognize the independence of the Philippines as soon as a stable government should be established. American Governor-General Harrison had concurred in the report of the Philippine Legislature as to a stable government.

Russia and its Revolution

President Wilson believed that with the end of Tsarist rule the new country would eventually transition to a modern democracy after the end of the chaos of theRussian Civil War

The Russian Civil War () was a multi-party civil war in the former Russian Empire sparked by the 1917 overthrowing of the Russian Provisional Government in the October Revolution, as many factions vied to determine Russia's political future. I ...

, and that intervention against Soviet Russia would only turn the country against the United States. He likewise publicly advocated a policy of noninterference in the war in the Fourteen Points, although he argued that the Russia's prewar Polish territory should be ceded to the newly independent Second Polish Republic

The Second Polish Republic, at the time officially known as the Republic of Poland, was a country in Central and Eastern Europe that existed between 7 October 1918 and 6 October 1939. The state was established in the final stage of World War I ...

. Additionally many of Wilson's political opponents in the United States, including the Chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee

The United States Senate Committee on Foreign Relations is a standing committee of the U.S. Senate charged with leading foreign-policy legislation and debate in the Senate. It is generally responsible for authorizing and overseeing foreign a ...

Henry Cabot Lodge

Henry Cabot Lodge (May 12, 1850November 9, 1924) was an American politician, historian, lawyer, and statesman from Massachusetts. A member of the History of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party, he served in the United States ...

, believed that an independent Ukraine

Ukraine is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the List of European countries by area, second-largest country in Europe after Russia, which Russia–Ukraine border, borders it to the east and northeast. Ukraine also borders Belarus to the nor ...

should be established. Despite this the United States, as a result of the fear of Japanese

Japanese may refer to:

* Something from or related to Japan, an island country in East Asia

* Japanese language, spoken mainly in Japan

* Japanese people, the ethnic group that identifies with Japan through ancestry or culture

** Japanese diaspor ...

expansion into Russian-held territory and their support for the Allied-aligned Czech Legion

The Czechoslovak Legion (Czech: ''Československé legie''; Slovak: ''Československé légie'') were volunteer armed forces consisting predominantly of Czechs and Slovaks fighting on the side of the Entente powers during World War I and the ...

, sent a small number of troops to Northern Russia

The Russian North () is an ethnocultural region situated in the Northwest Russia, northwestern part of Russia. It spans the regions of Arkhangelsk Oblast (including Nenets Autonomous Okrug), Murmansk Oblast, the Republic of Karelia, Komi Republi ...

and Siberia

Siberia ( ; , ) is an extensive geographical region comprising all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has formed a part of the sovereign territory of Russia and its predecessor states ...

. The United States also provided indirect aid such as food and supplies to the White Army

The White Army, also known as the White Guard, the White Guardsmen, or simply the Whites, was a common collective name for the armed formations of the White movement and Anti-Sovietism, anti-Bolshevik governments during the Russian Civil War. T ...

.

At the Paris Peace Conference in 1919 Wilson and British Prime Minister David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. A Liberal Party (United Kingdom), Liberal Party politician from Wales, he was known for leadi ...

, despite the objections of French President Georges Clemenceau

Georges Benjamin Clemenceau (28 September 1841 – 24 November 1929) was a French statesman who was Prime Minister of France from 1906 to 1909 and again from 1917 until 1920. A physician turned journalist, he played a central role in the poli ...

and Italian Foreign Minister Sidney Sonnino

Sidney Costantino, Baron Sonnino (; 11 March 1847 – 24 November 1922) was an Italian statesman, 19th prime minister of Italy and twice served briefly as one, in 1906 and again from 1909 to 1910. In 1901, he founded a new major newspaper, '' Il ...

, pushed forward an idea to convene a summit at Prinkipo between the Bolsheviks and the White movement

The White movement,. The old spelling was retained by the Whites to differentiate from the Reds. also known as the Whites, was one of the main factions of the Russian Civil War of 1917–1922. It was led mainly by the Right-wing politics, right- ...

to form a common Russian delegation to the Conference. The Soviet Commissariat of Foreign Affairs, under the leadership of Leon Trotsky

Lev Davidovich Bronstein ( – 21 August 1940), better known as Leon Trotsky,; ; also transliterated ''Lyev'', ''Trotski'', ''Trockij'' and ''Trotzky'' was a Russian revolutionary, Soviet politician, and political theorist. He was a key figure ...

and Georgy Chicherin

Georgy Vasilyevich Chicherin (or Tchitcherin; ; 24 November 1872 – 7 July 1936) was a Russian Marxist revolutionary and a Soviet politician who served as the first People's Commissar for Foreign Affairs in the Soviet government from March 1918 ...

, received British and American envoys respectfully but had no intentions of agreeing to the deal due to their belief that the Conference was composed of an old capitalist

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their use for the purpose of obtaining profit. This socioeconomic system has developed historically through several stages and is defined by ...

order that would be swept away in a world revolution

World revolution is the Marxist concept of overthrowing capitalism in all countries through the conscious revolutionary action of the organized working class. For theorists, these revolutions will not necessarily occur simultaneously, but whe ...

. By 1921, after the Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, were a radical Faction (political), faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with the Mensheviks at the 2nd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, ...

gained the upper hand in the Russian Civil War, executed

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty and formerly called judicial homicide, is the state-sanctioned killing of a person as punishment for actual or supposed misconduct. The sentence (law), sentence ordering that an offender b ...

the Romanov imperial family, repudiated the tsarist debt, and called for a world revolution by the working class, it was regarded as a pariah nation by most of the world. Beyond the Russian Civil War, relations were also dogged by claims of American companies for compensation for the nationalized industries they had invested in.

Famine and starvation raged in Russia and parts of Eastern Europe after the war. A very large food relief operation, centered mostly in Russia, was primarily funded by the U.S. government, as well as philanthropies, and Britain and France. The American Relief Administration

American Relief Administration (ARA) was an American Humanitarian aid, relief mission to Europe and later Russian Civil War, post-revolutionary Russia after World War I. Herbert Hoover, future president of the United States, was the program dire ...

, 1919–1923, at first was under the direction of Herbert Hoover

Herbert Clark Hoover (August 10, 1874 – October 20, 1964) was the 31st president of the United States, serving from 1929 to 1933. A wealthy mining engineer before his presidency, Hoover led the wartime Commission for Relief in Belgium and ...

.

Wilson had been reluctant to join but he sent two forces into Russia. The American Expeditionary Force, Siberia

The American Expeditionary Force, Siberia (AEF in Siberia) was a formation of the United States Army involved in the Russian Civil War in Vladivostok, Russia, after the October Revolution, from 1918 to 1920. The force was part of the larger All ...

was a formation of the United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the primary Land warfare, land service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is designated as the Army of the United States in the United States Constitution.Article II, section 2, clause 1 of th ...

involved in the Russian Civil War

The Russian Civil War () was a multi-party civil war in the former Russian Empire sparked by the 1917 overthrowing of the Russian Provisional Government in the October Revolution, as many factions vied to determine Russia's political future. I ...

in Vladivostok

Vladivostok ( ; , ) is the largest city and the administrative center of Primorsky Krai and the capital of the Far Eastern Federal District of Russia. It is located around the Zolotoy Rog, Golden Horn Bay on the Sea of Japan, covering an area o ...

, Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

, from 1918 to 1920. The other force was the American Expeditionary Force, North Russia

The American Expeditionary Force, North Russia (AEF in North Russia) (also known as the Polar Bear Expedition) was a contingent of about 5,000 United States Army troops that landed in Arkhangelsk, Russia as part of the Allied intervention in t ...

a part of the larger Allied French and British North Russia Intervention

The North Russia intervention, also known as the Northern Russian expedition, the Archangel campaign, and the Murman deployment, was part of the Allied intervention in the Russian Civil War after the October Revolution. The intervention brought a ...

, under the command of British General Edmund Ironside

Edmund Ironside (30 November 1016; , , ; sometimes also known as Edmund II) was King of the English from 23 April to 30 November 1016. He was the son of King Æthelred the Unready and his first wife, Ælfgifu of York. Edmund's reign was marre ...

. The Siberian force was ostensibly designed to help the 40,000 men of the Czechoslovak Legion

The Czechoslovak Legion ( Czech: ''Československé legie''; Slovak: ''Československé légie'') were volunteer armed forces consisting predominantly of Czechs and Slovaks fighting on the side of the Entente powers during World War I and the ...

, who were being held up by Bolshevik forces as they attempted to make their way along the Trans-Siberian Railroad to Vladivostok, and it was hoped, eventually to the Western Front. They had escaped from Russian POW camps and were headed to join the Allies on the Western Front. The North Russia force had a mission of preventing the German army from seizing Allied munitions sent there before Russia dropped out of the war. Neither force had an officially acknowledged combat mission. Historians have speculated that Wilson shared the anti-Bolshevik ambitions of the larger Allied intervention in the Russian Civil War

The Allied intervention in the Russian Civil War consisted of a series of multi-national military expeditions that began in 1918. The initial impetus behind the interventions was to secure munitions and supply depots from falling into the German ...

.

Entry into World War I

Brokering peace

From the outbreak of the war in 1914 until January 1917, Wilson's primary goal was using American neutrality to broker a peace conference that would end the war. In the first two years neither side was interested in negotiations. However, that changed in late 1916 when,Philip D. Zelikow

Philip David Zelikow (; born 21 September 1954) is an American diplomat and international relations scholar.

He has worked as the executive director of the 9/11 Commission, director of the Miller Center of Public Affairs at the University of Vi ...

argues, both sides were ready for peace negotiations, if Wilson would be the broker. However, Wilson waited too long, failed to realize the importance of his financial power over Britain, and put mistaken reliance on Colonel House

Edward Mandell House (July 26, 1858 – March 28, 1938) was an American diplomat, and an adviser to President Woodrow Wilson. He was known as Colonel House, although his title was honorary and he had performed no military service. He was a high ...

and Secretary of State Robert Lansing

Robert Lansing (; October 17, 1864 – October 30, 1928) was an American lawyer and diplomat who served as the 42nd United States Secretary of State under President Woodrow Wilson from 1915 to 1920. As Counselor to the State Department and then a ...

, who undermined his proposals by encouraging Britain to stall. Zelikow emphasizes that German Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg was seriously interested in peace, but he had to fend off the demands of Paul von Hindenburg

Paul Ludwig Hans Anton von Beneckendorff und von Hindenburg (2 October 1847 – 2 August 1934) was a German military and political leader who led the Imperial German Army during the First World War and later became President of Germany (1919� ...

and Erich Ludendorff

Erich Friedrich Wilhelm Ludendorff (; 9 April 1865 – 20 December 1937) was a German general and politician. He achieved fame during World War I (1914–1918) for his central role in the German victories at Battle of Liège, Liège and Battle ...

who were taking dictatorial control of Germany. Zelikow argues that when Wilson finally did make his peace proposal in January 1917, it was too little and too late, and instead of peace the war escalated. Hindenburg and Ludendorff had convinced the Kaiser that victory was at hand by using unrestricted submarine warfare, and moving troops in from the Russian front to smash the French and British front lines.

Wilson's decision to enter the war came in April 1917, more than two and a half years after the war began. The main reasons were the German submarine campaign to sink American ships carrying supplies to Britain, and his determination to make the world safe for democracy. Joseph Siracusa argues that Wilson's own position evolved from, 1914 to 1917. He finally decided that war was necessary because Germany threatened American global ideals of democracy and peace through militarism and Prussian autocracy. Furthermore, it was a threat to American commerce on the high seas, and to American rights as a neutral. Public opinion, elite opinion, and Members of Congress gave Wilson strong support by April 1917. The U.S. took an independent role and did not have a formal alliance with Britain or France.

German submarine warfare against Britain

With the outbreak ofWorld War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

in August 1914, the United States declared neutrality and worked to broker a peace. It insisted on its neutral rights, which included allowing private corporations and banks to sell supplies or loan money to either side. With the tight British blockade, there were almost no sales or loans to Germany, only to the Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not an explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are calle ...

. Americans were shocked by the Rape of Belgium

The Rape of Belgium was a series of systematic war crimes, especially mass murder and German occupation of Belgium during World War I#Deportation and forced labour, deportation, by German troops against Belgians, Belgian civilians during Germa ...

—German Army atrocities against civilians in Belgium. Britain was favored by elite WASP

A wasp is any insect of the narrow-waisted suborder Apocrita of the order Hymenoptera which is neither a bee nor an ant; this excludes the broad-waisted sawflies (Symphyta), which look somewhat like wasps, but are in a separate suborder ...

element. Pro-war forces were led by ex-president Theodore Roosevelt, who repeatedly denounced Wilson for timidity and cowardice. Wilson insisted on neutrality, denouncing both British and German violations. The British seized American property; the Germans seized American lives. In 1915 a German U-boat (a kind of submarine) torpedoed the unarmed British passenger liner RMS ''Lusitania''. It sank in 20 minutes, killing 128 American civilians and over 1,000 Britons. It was against the laws of war to sink any passenger ship without allowing the passengers to reach the life boats. American opinion turned strongly against Germany as a bloodthirsty threat to civilization. Germany apologized and promised to stop attacks by its U-boats. Both sides rejected Wilson's repeated efforts to negotiate an end to the war. Berlin reversed course in early 1917 when it saw the opportunity to strangle Britain's food supply by unrestricted submarine warfare. The Kaiser and Germany's real rulers, the Army commanders, realized it meant war with the United States, but expected they could defeat the Allies before the Americans could play a major military role. Germany started sinking American merchant ships in early 1917. Wilson asked Congress for a declaration of war in April 1917. He neutralized the antiwar element by arguing this was a war with the main long-term postwar goal of ending aggressive militarism and making the world "safe for democracy."

Public opinion

Apart fromWhite Anglo-Saxon Protestant

In the United States, White Anglo-Saxon Protestants or Wealthy Anglo-Saxon Protestants (WASP) is a Sociology, sociological term which is often used to describe White Americans, white Protestantism in the United States, Protestant Americans of E ...

and Anglophile

An Anglophile is a person who admires or loves England, its people, its culture, its language, and/or its various accents.

In some cases, Anglophilia refers to an individual's appreciation of English history and traditional English cultural ico ...

high society

High society, sometimes simply Society, is the behavior and lifestyle of people with the highest levels of wealth, power, fame and social status. It includes their related affiliations, social events and practices. Upscale social clubs were open ...

demanding a Special Relationship

The Special Relationship is an unofficial term for relations between the United Kingdom and the United States.

Special Relationship also may refer to:

* Special relationship (international relations), other exceptionally strong ties between nat ...

with the British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, Crown colony, colonies, protectorates, League of Nations mandate, mandates, and other Dependent territory, territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It bega ...

, American public opinion in 1914-1916 reflected a strong desire to stay out of the war. Support for American neutrality was particularly strong among those whom Wilson later demonised as Hyphenated Americans