Forcible Transfer Of Population on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Population transfer or resettlement is a type of

According to the political scientist Norman Finkelstein, population transfer was considered as an acceptable solution to the problems of ethnic conflict until around

According to the political scientist Norman Finkelstein, population transfer was considered as an acceptable solution to the problems of ethnic conflict until around

Historically, expulsions of

Historically, expulsions of

Following the Greco-Turkish War of 1919–1922, the League of Nations defined those to be mutually expelled as the "Muslim inhabitants of Greece" to Turkey and moving "the Christian Orthodox inhabitants of Turkey" to Greece. The plan met with fierce opposition in both countries and was condemned vigorously by a large number of countries. Undeterred,

Following the Greco-Turkish War of 1919–1922, the League of Nations defined those to be mutually expelled as the "Muslim inhabitants of Greece" to Turkey and moving "the Christian Orthodox inhabitants of Turkey" to Greece. The plan met with fierce opposition in both countries and was condemned vigorously by a large number of countries. Undeterred,

History of the War of Independence: The first month

"

In the ancient world, population transfer was the more humane alternative to putting all the males of a conquered territory to death and enslaving the women and children. From the 13th century BCE, Assyria used military history of the Neo-Assyrian Empire#Deportations, mass deportation as a punishment for List of revolutions and rebellions, rebellions. By the 9th century BCE, the Assyrians regularly deported thousands of restless subjects to other lands. Assyria forcibly resettled the inhabitants of the Kingdom of Israel (Samaria), Northern Kingdom of Israel in 720 BCE; these became known as the Ten Lost Tribes.

In the ancient world, population transfer was the more humane alternative to putting all the males of a conquered territory to death and enslaving the women and children. From the 13th century BCE, Assyria used military history of the Neo-Assyrian Empire#Deportations, mass deportation as a punishment for List of revolutions and rebellions, rebellions. By the 9th century BCE, the Assyrians regularly deported thousands of restless subjects to other lands. Assyria forcibly resettled the inhabitants of the Kingdom of Israel (Samaria), Northern Kingdom of Israel in 720 BCE; these became known as the Ten Lost Tribes.

online review

* A. de Zayas, "International Law and Mass Population Transfers," ''Harvard International Law Journal'' 207 (1975). * A. de Zayas, "The Right to the Homeland, Ethnic Cleansing and the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia," ''Criminal Law Forum,'' Vol. 6, 1995, pp. 257–314. * A. de Zayas, ''Nemesis at Potsdam'', London 1977. * A. de Zayas, ''A Terrible Revenge,'' Palgrave/Macmillan, New York, 1994. . * A. de Zayas, ''Die deutschen Vertriebenen,'' Graz 2006. . * A. de Zayas, ''Heimatrecht ist Menschenrecht,'' München 2001. . * N. Naimark, " Fires of Hatred," ''Ethnic Cleansing in Twentieth-Century Europe,'' Harvard University Press, 2001. * U. Özsu, ''Formalizing Displacement: International Law and Population Transfers'', Oxford University Press, 2015. * St. Prauser and A. Rees, ''The Expulsion of the "German" Communities from Eastern Europe at the End of the Second World War,'' Florence, Italy, European University Institute, 2004.

"Population, Expulsion and Transfer"

''Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law''

UN Report

historical population transfers and exchanges (continues at bottom of page)

''Freedom of Movement – Human rights and population transfer''

UN report on legal status of population transfers

Paul Lovell Hooper, ''Forced Population Transfers in Early Ottoman Imperial Strategy, A Comparative Approach''

2003, senior thesis for BA degree, Princeton University

"Medieval Jewish expulsions from French territories"

, Jewish Gates

, population transfer statistics in the Middle East

Lausanne Treaty Emigrants Association

{{Authority control Forced migration Population Crimes against humanity by type

mass migration

Mass migration refers to the migration of large groups of people from one geographical area to another. Mass migration is distinguished from individual or small-scale migration; and also from seasonal migration, which may occur on a regular basi ...

that is often imposed by a state policy or international authority. Such mass migrations are most frequently spurred on the basis of ethnicity

An ethnicity or ethnic group is a group of people with shared attributes, which they Collective consciousness, collectively believe to have, and long-term endogamy. Ethnicities share attributes like language, culture, common sets of ancestry, ...

or religion, but they also occur due to economic development

In economics, economic development (or economic and social development) is the process by which the economic well-being and quality of life of a nation, region, local community, or an individual are improved according to targeted goals and object ...

. Banishment or exile

Exile or banishment is primarily penal expulsion from one's native country, and secondarily expatriation or prolonged absence from one's homeland under either the compulsion of circumstance or the rigors of some high purpose. Usually persons ...

is a similar process, but is forcibly applied to individuals and groups. Population transfer differs more than simply technically from individually motivated migration

Migration, migratory, or migrate may refer to: Human migration

* Human migration, physical movement by humans from one region to another

** International migration, when peoples cross state boundaries and stay in the host state for some minimum le ...

, but at times of war

War is an armed conflict between the armed forces of states, or between governmental forces and armed groups that are organized under a certain command structure and have the capacity to sustain military operations, or between such organi ...

, the act of fleeing from danger or famine

A famine is a widespread scarcity of food caused by several possible factors, including, but not limited to war, natural disasters, crop failure, widespread poverty, an Financial crisis, economic catastrophe or government policies. This phenom ...

often blurs the differences.

Often the affected population is transferred by force to a distant region, perhaps not suited to their way of life, causing them substantial harm. In addition, the process implies the loss of immovable property

In English common law, real property, real estate, immovable property or, solely in the US and Canada, realty, refers to parcels of land and any associated structures which are the property of a person. For a structure (also called an impro ...

and substantial amounts of movable property when rushed. This transfer may be motivated by the more powerful party's desire to make other uses of the land in question or, less often, by security or disastrous environmental or economic conditions that require relocation.

The first known population transfers date back to the Middle Assyrian Empire

The Middle Assyrian Empire was the third stage of Assyrian history, covering the history of Assyria from the accession of Ashur-uballit I 1363 BC and the rise of Assyria as a territorial kingdom to the death of Ashur-dan II in 912 BC. ...

in the 13th century BCE, with forced resettlement being particularly prevalent during the Neo-Assyrian Empire. The single largest population transfer in history was the Partition of India

The partition of India in 1947 was the division of British India into two independent dominion states, the Dominion of India, Union of India and Dominion of Pakistan. The Union of India is today the Republic of India, and the Dominion of Paki ...

in 1947 that involved up to 12 million people in Punjab Province with a total of up to 20 million people across British India

The provinces of India, earlier presidencies of British India and still earlier, presidency towns, were the administrative divisions of British governance in South Asia. Collectively, they have been called British India. In one form or another ...

, with the second largest being the flight and expulsion of Germans after World War II, which involved more than 12 million people.

Before the forcible deportation of Ukrainians (including thousands of children) to Russia during the Russian invasion of Ukraine

On 24 February 2022, , starting the largest and deadliest war in Europe since World War II, in a major escalation of the Russo-Ukrainian War, conflict between the two countries which began in 2014. The fighting has caused hundreds of thou ...

, the last major population transfer in Europe was the deportation of 800,000 ethnic Albanians

The Albanians are an ethnic group native to the Balkan Peninsula who share a common Albanian ancestry, Albanian culture, culture, Albanian history, history and Albanian language, language. They are the main ethnic group of Albania and Kosovo, ...

during the Kosovo War

The Kosovo War (; sr-Cyrl-Latn, Косовски рат, Kosovski rat) was an armed conflict in Kosovo that lasted from 28 February 1998 until 11 June 1999. It ...

in 1999. Moreover, some of the largest population transfers in Europe have been attributed to the ethnic policies of the Soviet Union under Joseph Stalin.

Population transfers can also be imposed to further economic development

In economics, economic development (or economic and social development) is the process by which the economic well-being and quality of life of a nation, region, local community, or an individual are improved according to targeted goals and object ...

, for instance China relocated 1.3 million residents in order to construct the Three Gorges Dam

The Three Gorges Dam (), officially known as Yangtze River Three Gorges Water Conservancy Project () is a hydroelectric gravity dam that spans the Yangtze River near Sandouping in Yiling District, Yichang, Hubei province, central China, downs ...

.

Historical background

The earliest known examples of population transfers took place in the context of war and empire. As part ofSennacherib

Sennacherib ( or , meaning "Sin (mythology), Sîn has replaced the brothers") was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 705BC until his assassination in 681BC. The second king of the Sargonid dynasty, Sennacherib is one of the most famous A ...

's campaign against King Hezekiah of Jerusalem (701 BCE) "200,150 people great and small, male and female" were transferred to other lands in the Neo-Assyrian Empire

The Neo-Assyrian Empire was the fourth and penultimate stage of ancient Assyrian history. Beginning with the accession of Adad-nirari II in 911 BC, the Neo-Assyrian Empire grew to dominate the ancient Near East and parts of South Caucasus, Nort ...

. Similar population transfers occurred under the Achaemenid

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire, also known as the Persian Empire or First Persian Empire (; , , ), was an Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great of the Achaemenid dynasty in 550 BC. Based in modern-day Iran, it was the large ...

and Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centred on Constantinople during late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Having survived History of the Roman Empire, the events that caused the ...

s. Population transfers are considered incompatible with the values of post-Enlightenment European societies, but this was usually limited to the home territory of the colonial power itself and population transfers continued in European colonies during the 20th century.

Specific types of population transfer

Population exchange

Population exchange is the transfer of two populations in opposite directions at about the same time. In theory at least, the exchange is non-forcible, but the reality of the effects of these exchanges has always been unequal, and at least one half of the so-called "exchange" has usually been forced by the stronger or richer participant. Such exchanges have taken place several times in the 20th century: * The partition of India and Pakistan * The mass expulsion of Anatolian Greeks and Balkan Turks from Turkey and Greece, respectively, during their so-calledGreek-Turkish population exchange

The 1923 population exchange between Greece and Turkey stemmed from the "Convention Concerning the Exchange of Greek and Turkish Populations" signed at Lausanne, Switzerland, on 30 January 1923, by the governments of Greece and Turkey. It involv ...

. It involved approximately 1.3 million Anatolian Christians (majority Greek) and 354,000 Balkan Muslims (majority Turkish), most of whom were forcibly made refugees and ''de jure'' denaturalized from their homelands.

* The 1940 peaceful population exchange between Bulgaria and Romania

The population exchange between Bulgaria and Romania was a population exchange carried out in 1940 after the transfer of Southern Dobruja to Bulgaria by Romania. It involved 103,711 Romanians, Aromanians and Megleno-Romanians living in Southern Do ...

* The Cyprus population exchange following the Turkish invasion of Cyprus

The Turkish invasion of Cyprus began on 20 July 1974 and progressed in two phases over the following month. Taking place upon a background of Cypriot intercommunal violence, intercommunal violence between Greek Cypriots, Greek and Turkish Cy ...

in 1974 that led to displacement of 140,000 Greeks from the north and around 60,000 Turks that have relocated from the south to the north.

Ethnic dilution

Ethnic dilution is the practice of enacting immigration policies to relocate parts of an ethnically and/or culturally dominant population into a region populated by an ethnic minority or otherwise culturally different or non-mainstream group to dilute and eventually to transform the native ethnic population into the mainstream culture over time.Changes in international law

According to the political scientist Norman Finkelstein, population transfer was considered as an acceptable solution to the problems of ethnic conflict until around

According to the political scientist Norman Finkelstein, population transfer was considered as an acceptable solution to the problems of ethnic conflict until around World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

and even for a time afterward. Transfer was considered a drastic but "often necessary" means to end an ethnic conflict or ethnic civil war

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

. The feasibility of population transfer was hugely increased by the creation of railroad

Rail transport (also known as train transport) is a means of transport using wheeled vehicles running in railway track, tracks, which usually consist of two parallel steel railway track, rails. Rail transport is one of the two primary means of ...

networks from the mid-19th century. George Orwell

Eric Arthur Blair (25 June 1903 – 21 January 1950) was an English novelist, poet, essayist, journalist, and critic who wrote under the pen name of George Orwell. His work is characterised by lucid prose, social criticism, opposition to a ...

, in his 1946 essay "Politics and the English Language

"Politics and the English Language" (1946) is an essay by George Orwell that criticised the "ugly and inaccurate" written English of his time and examined the connection between political orthodoxies and the debasement of language.

The essay ...

" (written during the World War II evacuation and expulsion

Mass evacuation, forced displacement, expulsion, and deportation of millions of people took place across most countries involved in World War II. The Second World War caused the movement of the largest number of people in the shortest period of t ...

s in Europe), observed:

:"In our time, political speech and writing are largely the defence of the indefensible. Things... can indeed be defended, but only by arguments which are too brutal for most people to face, and which do not square with the professed aims of political parties. Thus political language has to consist largely of euphemism, question-begging and sheer cloudy vagueness.... Millions of peasants are robbed of their farms and sent trudging along the roads with no more than they can carry: this is called ''transfer of population'' or ''rectification of frontiers''."

The view of international law on population transfer underwent considerable evolution during the 20th century. Prior to World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, many major population transfers were the result of bilateral treaties and had the support of international bodies such as the League of Nations

The League of Nations (LN or LoN; , SdN) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920), Paris Peace ...

. The expulsion of Germans after World War II

Expulsion or expelled may refer to:

General

* Deportation

* Ejection (sports)

* Eviction

* Exile

* Expeller pressing

* Expulsion (education)

* Expulsion from the United States Congress

* Extradition

* Forced migration

* Ostracism

* Pers ...

from Central and Eastern Europe after World War II was sanctioned by the Allies in Article 13 of the Potsdam communiqué, but research has shown that both the British and the American delegations at Potsdam strongly objected to the size of the population transfer that had already taken place and was accelerating in the summer of 1945. The principal drafter of the provision, Geoffrey Harrison, explained that the article was intended not to approve the expulsions but to find a way to transfer the competence to the Control Council in Berlin to regulate the flow.

The tide started to turn when the Charter of the Nuremberg Trials #REDIRECT Nuremberg trials

{{redirect category shell, {{R from other capitalisation{{R from move ...

of German Nazi leaders declared forced deportation of civilian populations to be both a war crime and a crime against humanity. That opinion was progressively adopted and extended through the remainder of the century. Underlying the change was the trend to assign rights to individuals, thereby limiting the rights of states to make agreements that adversely affect them.

There is now little debate about the general legal status of involuntary population transfers: "Where population transfers used to be accepted as a means to settle ethnic conflict, today, forced population transfers are considered violations of international law." No legal distinction is made between one-way and two-way transfers since the rights of each individual are regarded as independent of the experience of others.

Article 49 of the Fourth Geneva Convention

The Convention relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War (), more commonly referred to as the Fourth Geneva Convention and abbreviated as GCIV, is one of the four treaties of the Geneva Conventions. It was adopted in August 1 ...

(adopted in 1949 and now part of customary international law

Customary international law consists of international legal obligations arising from established or usual international practices, which are less formal customary expectations of behavior often unwritten as opposed to formal written treaties or c ...

) prohibits mass movement of protected persons

Protected persons is a legal term under international humanitarian law and refers to persons who are under specific protection of the 1949 Geneva Conventions, their 1977 Additional Protocols, and customary international humanitarian law during an ...

out of or into territory under belligerent

A belligerent is an individual, group, country, or other entity that acts in a hostile manner, such as engaging in combat. The term comes from the Latin ''bellum gerere'' ("to wage war"). Unlike the use of ''belligerent'' as an adjective meanin ...

military occupation

Military occupation, also called belligerent occupation or simply occupation, is temporary hostile control exerted by a ruling power's military apparatus over a sovereign territory that is outside of the legal boundaries of that ruling pow ...

:

An interim report of the United Nations Sub-Commission on Prevention of Discrimination and Protection of Minorities (1993) says:

The same report warned of the difficulty of ensuring true voluntariness:

"some historical transfers did not call for forced or compulsory transfers, but included options for the affected populations. Nonetheless, the conditions attending the relevant treaties created strong moral, psychological and economic pressures to move."The final report of the Sub-Commission (1997) invoked numerous legal conventions and treaties to support the position that population transfers contravene international law unless they have the consent of both the moved population and the host population. Moreover, that consent must be given free of direct or indirect negative pressure. "Deportation or forcible transfer of population" is defined as a

crime against humanity

Crimes against humanity are certain serious crimes committed as part of a large-scale attack against civilians. Unlike war crimes, crimes against humanity can be committed during both peace and war and against a state's own nationals as well as ...

by the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court

The Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court is the treaty that established the International Criminal Court (ICC). It was adopted at a diplomatic conference in Rome, Italy on 17 July 1998Michael P. Scharf (August 1998)''Results of the R ...

(Article 7). The International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia

The International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) was a body of the United Nations that was established to prosecute the war crimes in the Yugoslav Wars, war crimes that had been committed during the Yugoslav Wars and to tr ...

has indicted and sometimes convicted a number of politicians and military commanders indicted for forced deportations in that region.

Ethnic cleansing

Ethnic cleansing is the systematic forced removal of ethnic, racial, or religious groups from a given area, with the intent of making the society ethnically homogeneous. Along with direct removal such as deportation or population transfer, it ...

encompasses "deportation or forcible transfer of population" and the force involved may involve other crimes, including crimes against humanity. Nationalist

Nationalism is an idea or movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the State (polity), state. As a movement, it presupposes the existence and tends to promote the interests of a particular nation,Anthony D. Smith, Smith, A ...

agitation can harden public support, one way or the other, for or against population transfer as a solution to current or possible future ethnic conflict, and attitudes can be cultivated by supporters of either plan of action with its supportive propaganda

Propaganda is communication that is primarily used to influence or persuade an audience to further an agenda, which may not be objective and may be selectively presenting facts to encourage a particular synthesis or perception, or using loaded l ...

used as a typical political tool by which their goals can be achieved.

In Europe

France

Two famous transfers connected with thehistory of France

The first written records for the history of France appeared in the Iron Age France, Iron Age.

What is now France made up the bulk of the region known to the Romans as Gaul. Greek writers noted the presence of three main ethno-linguistic grou ...

are the banning of the religion of the Jews in 1308 and that of the Huguenot

The Huguenots ( , ; ) are a Religious denomination, religious group of French people, French Protestants who held to the Reformed (Calvinist) tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, ...

s, French Protestants

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

by the Edict of Fontainebleau

The Edict of Fontainebleau (18 October 1685, published 22 October 1685) was an edict issued by French King Louis XIV and is also known as the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes. The Edict of Nantes (1598) had granted Huguenots the right to prac ...

in 1685. Religious warfare over the Protestants led to many seeking refuge in the Low Countries, England and Switzerland. In the early 18th century, some Huguenots emigrated to colonial America

The colonial history of the United States covers the period of European colonization of North America from the late 15th century until the unifying of the Thirteen British Colonies and creation of the United States in 1776, during the Re ...

. In both cases, the population was not forced out but rather their religion was declared illegal and so many left the country.

According to Ivan Sertima, Louis XV

Louis XV (15 February 1710 – 10 May 1774), known as Louis the Beloved (), was King of France from 1 September 1715 until his death in 1774. He succeeded his great-grandfather Louis XIV at the age of five. Until he reached maturity (then defi ...

ordered all blacks to be deported from France but was unsuccessful. At the time, they were mostly free people of color

In the context of the history of slavery in the Americas, free people of color (; ) were primarily people of mixed African, European, and Native American descent who were not enslaved. However, the term also applied to people born free who we ...

from the Caribbean and Louisiana colonies, usually descendants of French colonial men and African women. Some fathers sent their mixed-race sons to France to be educated or gave them property to be settled there. Others entered the military, as did Thomas-Alexandre Dumas

Army general (France), Army-General Thomas-Alexandre Dumas Davy de la Pailleterie (; 25 March 1762 – 26 February 1806) was a French Army officer who served in the French Revolutionary Wars.

Along with fellow French officers and Toussaint Lo ...

, the father of Alexandre Dumas

Alexandre Dumas (born Alexandre Dumas Davy de la Pailleterie, 24 July 1802 – 5 December 1870), also known as Alexandre Dumas , was a French novelist and playwright.

His works have been translated into many languages and he is one of the mos ...

.

Some Algerians were also forcefully removed from their native land by France in the late 19th century, and moved to the Pacific, most notably to New Caledonia.

Ireland

After theCromwellian conquest of Ireland

The Cromwellian conquest of Ireland (1649–1653) was the re-conquest of Ireland by the Commonwealth of England, initially led by Oliver Cromwell. It forms part of the 1641 to 1652 Irish Confederate Wars, and wider 1639 to 1653 Wars of the Three ...

and Act of Settlement

The Act of Settlement ( 12 & 13 Will. 3. c. 2) is an act of the Parliament of England that settled the succession to the English and Irish crowns to only Protestants, which passed in 1701. More specifically, anyone who became a Roman Cathol ...

in 1652, most indigenous Irish Catholic

Irish Catholics () are an ethnoreligious group native to Ireland, defined by their adherence to Catholic Christianity and their shared Irish ethnic, linguistic, and cultural heritage.The term distinguishes Catholics of Irish descent, particul ...

land holders had their lands confiscated and were banned from living in planted towns. An unknown number, possibly as high as 100,000 Irish were removed to the colonies in the West Indies and North America as indentured servants

Indentured servitude is a form of labor in which a person is contracted to work without salary for a specific number of years. The contract called an "indenture", may be entered voluntarily for a prepaid lump sum, as payment for some good or ser ...

.

In addition, the Crown supported a series of population transfers into Ireland to enlarge the loyal Protestant population of Ireland. Known as the plantations, they had migrants come chiefly from Scotland and the northern border counties of England. In the late eighteenth century, the Scots-Irish constituted the largest group of immigrants from the British Isles to enter the Thirteen Colonies

The Thirteen Colonies were the British colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America which broke away from the British Crown in the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783), and joined to form the United States of America.

The Thirteen C ...

before the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was the armed conflict that comprised the final eight years of the broader American Revolution, in which Am ...

.

Scotland

Theenclosure

Enclosure or inclosure is a term, used in English landownership, that refers to the appropriation of "waste" or "common land", enclosing it, and by doing so depriving commoners of their traditional rights of access and usage. Agreements to enc ...

s that depopulated rural England in the British Agricultural Revolution

The British Agricultural Revolution, or Second Agricultural Revolution, was an unprecedented increase in agricultural production in Britain arising from increases in labor and land productivity between the mid-17th and late 19th centuries. Agricu ...

started during the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

. Similar developments in Scotland

Scotland is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It contains nearly one-third of the United Kingdom's land area, consisting of the northern part of the island of Great Britain and more than 790 adjac ...

have lately been called the Lowland Clearances

The Lowland Clearances were one of the results of the Scottish Agricultural Revolution, which changed the traditional system of agriculture which had existed in Lowland Scotland in the seventeenth century. Thousands of cottars and tenant far ...

.

The Highland Clearances

The Highland Clearances ( , the "eviction of the Gaels") were the evictions of a significant number of tenants in the Scottish Highlands and Islands, mostly in two phases from 1750 to 1860.

The first phase resulted from Scottish Agricultural R ...

were forced displacements of the populations of the Scottish Highlands

The Highlands (; , ) is a historical region of Scotland. Culturally, the Highlands and the Scottish Lowlands, Lowlands diverged from the Late Middle Ages into the modern period, when Scots language, Lowland Scots language replaced Scottish Gae ...

and Scottish Islands in the 18th century. They led to mass emigration to the coast, the Scottish Lowlands

The Lowlands ( or , ; , ) is a cultural and historical region of Scotland.

The region is characterised by its relatively flat or gently rolling terrain as opposed to the mountainous landscapes of the Scottish Highlands. This area includes ci ...

and abroad, including to the Thirteen Colonies, Canada and the Caribbean.

Central Europe

Historically, expulsions of

Historically, expulsions of Jews

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

and of Romani people

{{Infobox ethnic group

, group = Romani people

, image =

, image_caption =

, flag = Roma flag.svg

, flag_caption = Romani flag created in 1933 and accepted at the 1971 World Romani Congress

, po ...

reflect the power of state control that has been applied as a tool, in the form of expulsion edicts, laws, mandates etc., against them for centuries.

After the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact

The Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, officially the Treaty of Non-Aggression between Germany and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, and also known as the Hitler–Stalin Pact and the Nazi–Soviet Pact, was a non-aggression pact between Nazi Ge ...

divided Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It extends from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Sudetes and Carpathian Mountains in the south, bordered by Lithuania and Russia to the northeast, Belarus and Ukrai ...

during World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, Germans deported Poles

Pole or poles may refer to:

People

*Poles (people), another term for Polish people, from the country of Poland

* Pole (surname), including a list of people with the name

* Pole (musician) (Stefan Betke, born 1967), German electronic music artist

...

and Jews

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

from Polish territories annexed by Nazi Germany, and the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

deported Poles from areas of Eastern Poland, Kresy

Eastern Borderlands (), often simply Borderlands (, ) was a historical region of the eastern part of the Second Polish Republic. The term was coined during the interwar period (1918–1939). Largely agricultural and extensively multi-ethnic with ...

to Siberia and Kazakhstan. From 1940, Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

tried to get Germans to resettle from the areas in which they were the minority (the Baltics, South-Eastern and Eastern Europe) to the Warthegau, the region around Poznań

Poznań ( ) is a city on the Warta, River Warta in west Poland, within the Greater Poland region. The city is an important cultural and business center and one of Poland's most populous regions with many regional customs such as Saint John's ...

, German ''Posen''. He expelled the Poles and Jews who formed there the majority of the population. Before the war, the Germans

Germans (, ) are the natives or inhabitants of Germany, or sometimes more broadly any people who are of German descent or native speakers of the German language. The Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany, constitution of Germany, imple ...

were 16% of the population in the area.

The Nazis

Nazism (), formally named National Socialism (NS; , ), is the far-right politics, far-right Totalitarianism, totalitarian socio-political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Germany. During H ...

initially tried to press Jews to emigrate and in Austria succeeded in driving out most of the Jewish population. However, increasing foreign resistance brought the plan to a virtual halt. Later on, Jews were transferred to ghetto

A ghetto is a part of a city in which members of a minority group are concentrated, especially as a result of political, social, legal, religious, environmental or economic pressure. Ghettos are often known for being more impoverished than other ...

es and eventually to death camps. Use of forced labor in Nazi Germany during World War II occurred on a large scale. Jews who had signed over properties in Germany and Austria during Nazism, although coerced to do so, found it nearly impossible to be reimbursed after World War II, partly because of the ability of governments to make the "personal decision to leave" argument.

The Germans abducted about 12 million people from almost twenty European countries; about two thirds of whom came from Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the Europe, European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural and socio-economic connotations. Its eastern boundary is marked by the Ural Mountain ...

.

After World War II, when the Curzon line, which had been proposed in 1919 by the Western Allies as Poland's eastern border, was implemented, members of all ethnic groups were transferred to their respective new territories (Poles

Pole or poles may refer to:

People

*Poles (people), another term for Polish people, from the country of Poland

* Pole (surname), including a list of people with the name

* Pole (musician) (Stefan Betke, born 1967), German electronic music artist

...

to Poland, Ukrainians

Ukrainians (, ) are an East Slavs, East Slavic ethnic group native to Ukraine. Their native tongue is Ukrainian language, Ukrainian, and the majority adhere to Eastern Orthodox Church, Eastern Orthodoxy, forming the List of contemporary eth ...

to Soviet Ukraine). The same applied to the formerly-German territories east of the Oder-Neisse line, where German citizens were transferred to Germany. Germans were expelled from areas annexed by the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

and Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It extends from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Sudetes and Carpathian Mountains in the south, bordered by Lithuania and Russia to the northeast, Belarus and Ukrai ...

as well as territories of Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia ( ; Czech language, Czech and , ''Česko-Slovensko'') was a landlocked country in Central Europe, created in 1918, when it declared its independence from Austria-Hungary. In 1938, after the Munich Agreement, the Sudetenland beca ...

, Hungary

Hungary is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning much of the Pannonian Basin, Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia and ...

, Romania

Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern and Southeast Europe. It borders Ukraine to the north and east, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Bulgaria to the south, Moldova to ...

and Yugoslavia

, common_name = Yugoslavia

, life_span = 1918–19921941–1945: World War II in Yugoslavia#Axis invasion and dismemberment of Yugoslavia, Axis occupation

, p1 = Kingdom of SerbiaSerbia

, flag_p ...

. From 1944 until 1948, between 13.5 and 16.5 million Germans were expelled, evacuated or fled from Central and Eastern Europe. The Statistisches Bundesamt (federal statistics office) estimates the loss of life at 2.1 million

Poland and Soviet Ukraine

The Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, abbreviated as the Ukrainian SSR, UkrSSR, and also known as Soviet Ukraine or just Ukraine, was one of the constituent republics of the Soviet Union from 1922 until 1991. Under the Soviet one-party m ...

conducted population exchanges. Poles residing east of the new Poland-Soviet border were deported to Poland (2,100,000 persons), and Ukrainians

Ukrainians (, ) are an East Slavs, East Slavic ethnic group native to Ukraine. Their native tongue is Ukrainian language, Ukrainian, and the majority adhere to Eastern Orthodox Church, Eastern Orthodoxy, forming the List of contemporary eth ...

that resided west of the New border were deported to Soviet Ukraine. Population transfer to Soviet Ukraine occurred from September 1944 to May 1946 (450,000 persons). Some Ukrainians (200,000 persons) left southeast Poland more or less voluntarily (between 1944 and 1945). The second event occurred in 1947 under Operation Vistula

Operation Vistula (; ) was the codename for the 1947 forced resettlement of close to 150,000 Ukrainians in Poland, Ukrainians (including Rusyns, Boykos, and Lemkos) from the southeastern provinces of People's Republic of Poland, postwar Poland to ...

.

Nearly 20 million people in Europe

Europe is a continent located entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Eastern Hemisphere. It is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Mediterranean Sea to the south, and Asia to the east ...

fled their homes or were expelled, transferred or exchanged during the process of sorting out ethnic groups between 1944 and 1951.

Spain

In 1492 the Jewish population of Spain was expelled through theAlhambra Decree

The Alhambra Decree (also known as the Edict of Expulsion; Spanish language, Spanish: ''Decreto de la Alhambra'', ''Edicto de Granada'') was an edict issued on 31 March 1492 by the joint Catholic Monarchs of Spain, Isabella I of Castile and Ferdi ...

. Some of the Jews went to North Africa; others east into Poland, France and Italy, and other Mediterranean countries.

In 1609, was the Expulsion of the Moriscos, the final transfer of 300,000 Muslims out of Spain, after more than a century of Catholic trials, segregation, and religious restrictions. Most of the Spanish Muslims went to North Africa and to areas of Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

control.

Southeastern Europe

In September 1940, with the return ofSouthern Dobruja

Southern Dobruja or South Dobruja ( or simply , ; or , ), also the Quadrilateral (), is an area of north-eastern Bulgaria comprising Dobrich and Silistra provinces, part of the historical region of Dobruja. It has an area of 7,412 square km an ...

by Romania

Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern and Southeast Europe. It borders Ukraine to the north and east, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Bulgaria to the south, Moldova to ...

to Bulgaria

Bulgaria, officially the Republic of Bulgaria, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern portion of the Balkans directly south of the Danube river and west of the Black Sea. Bulgaria is bordered by Greece and Turkey t ...

under the Treaty of Craiova

The Treaty of Craiova (; ) was signed on 7 September 1940 and ratified on 13 September 1940 by the Kingdom of Bulgaria and the Kingdom of Romania. Under its terms, Romania had to allow Bulgaria to retake Southern Dobruja, which Romania had gained ...

, a population exchange was carried out. 103,711 Romanians, Aromanians

The Aromanians () are an Ethnic groups in Europe, ethnic group native to the southern Balkans who speak Aromanian language, Aromanian, an Eastern Romance language. They traditionally live in central and southern Albania, south-western Bulgari ...

and Megleno-Romanians

The Megleno-Romanians, also known as Meglenites (), Moglenite Vlachs or simply Vlachs (), are an Eastern Romance ethnic group, originally inhabiting seven villages in the Moglena region spanning the Pella and Kilkis regional units of Central ...

were compelled to move north of the border, while 62,278 Bulgarians living in Northern Dobruja

Dobruja or Dobrudja (; or ''Dobrudža''; , or ; ; Dobrujan Tatar: ''Tomrîğa''; Ukrainian language, Ukrainian and ) is a Geography, geographical and historical region in Southeastern Europe that has been divided since the 19th century betw ...

were forced to move into Bulgaria.

Around 360,000 Bulgarian Turks

Bulgarian Turks (; ) are ethnic Turkish people from Bulgaria. According to the 2021 census, there were 508,375 Bulgarians of Turkish descent, roughly 8.4% of the population, making them the country's largest ethnic minority. Bulgarian Turks ...

fled Bulgaria during the Revival Process.

During the Yugoslav wars

The Yugoslav Wars were a series of separate but related#Naimark, Naimark (2003), p. xvii. ethnic conflicts, wars of independence, and Insurgency, insurgencies that took place from 1991 to 2001 in what had been the Socialist Federal Republic of ...

in the 1990s, the breakup of Yugoslavia

, common_name = Yugoslavia

, life_span = 1918–19921941–1945: World War II in Yugoslavia#Axis invasion and dismemberment of Yugoslavia, Axis occupation

, p1 = Kingdom of SerbiaSerbia

, flag_p ...

caused large population transfers, mostly involuntary. As it was a conflict fueled by ethnic nationalism

Ethnic nationalism, also known as ethnonationalism, is a form of nationalism wherein the nation and nationality are defined in terms of ethnicity, with emphasis on an ethnocentric (and in some cases an ethnostate/ethnocratic) approach to variou ...

, people of minority ethnicities generally fled towards regions that their ethnicity was the majority.

The phenomenon of "ethnic cleansing

Ethnic cleansing is the systematic forced removal of ethnic, racial, or religious groups from a given area, with the intent of making the society ethnically homogeneous. Along with direct removal such as deportation or population transfer, it ...

" was first seen in Croatia

Croatia, officially the Republic of Croatia, is a country in Central Europe, Central and Southeast Europe, on the coast of the Adriatic Sea. It borders Slovenia to the northwest, Hungary to the northeast, Serbia to the east, Bosnia and Herze ...

but soon spread to Bosnia

Bosnia and Herzegovina, sometimes known as Bosnia-Herzegovina and informally as Bosnia, is a country in Southeast Europe. Situated on the Balkans, Balkan Peninsula, it borders Serbia to the east, Montenegro to the southeast, and Croatia to th ...

. Since the Bosnian Muslims

The Bosniaks (, Cyrillic: Бошњаци, ; , ) are a South Slavic ethnic group native to the Southeast European historical region of Bosnia, today part of Bosnia and Herzegovina, and who share a common ancestry, culture, history and the ...

had no immediate refuge, they were arguably the hardest hit by the ethnic violence. United Nations tried to create ''safe areas'' for Muslim populations of eastern Bosnia but in the Srebrenica massacre

The Srebrenica massacre, also known as the Srebrenica genocide, was the July 1995 genocidal killing of more than 8,000 Bosniak Muslim men and boys in and around the town of Srebrenica during the Bosnian War. It was mainly perpetrated by unit ...

and elsewhere, the peacekeeping troops failed to protect the ''safe areas'', resulting in the massacre of thousands of Muslims.

The Dayton Accords

The General Framework Agreement for Peace in Bosnia and Herzegovina, also known as the Dayton Agreement or the Dayton Accords ( sh-Latn-Cyrl, Dejtonski mirovni sporazum, Дејтонски мировни споразум), and colloquially kn ...

ended the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina

Bosnia and Herzegovina, sometimes known as Bosnia-Herzegovina and informally as Bosnia, is a country in Southeast Europe. Situated on the Balkans, Balkan Peninsula, it borders Serbia to the east, Montenegro to the southeast, and Croatia to th ...

, fixing the borders between the two warring parties roughly to those established by the autumn of 1995. One immediate result of the population transfer after the peace deal was a sharp decline in ethnic violence in the region.

A massive and systematic deportation of Serbia

, image_flag = Flag of Serbia.svg

, national_motto =

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Serbia.svg

, national_anthem = ()

, image_map =

, map_caption = Location of Serbia (gree ...

's Albanians

The Albanians are an ethnic group native to the Balkan Peninsula who share a common Albanian ancestry, Albanian culture, culture, Albanian history, history and Albanian language, language. They are the main ethnic group of Albania and Kosovo, ...

took place during the Kosovo War

The Kosovo War (; sr-Cyrl-Latn, Косовски рат, Kosovski rat) was an armed conflict in Kosovo that lasted from 28 February 1998 until 11 June 1999. It ...

of 1999, with around 800,000 Albanians (out of a population of about 1.5 million) forced to flee Kosovo

Kosovo, officially the Republic of Kosovo, is a landlocked country in Southeast Europe with International recognition of Kosovo, partial diplomatic recognition. It is bordered by Albania to the southwest, Montenegro to the west, Serbia to the ...

. Albanians became the majority in Kosovo at the wars end, around 200,000 Serbs and Roma fled Kosovo. When Kosovo proclaimed independence in 2008, the bulk of its population was Albanian.

A number of commanders and politicians, notably Serbia and Yugoslav President Slobodan Milošević

Slobodan Milošević ( sr-Cyrl, Слободан Милошевић, ; 20 August 1941 – 11 March 2006) was a Yugoslav and Serbian politician who was the President of Serbia between 1989 and 1997 and President of the Federal Republic of Yugos ...

, were put on trial by the UN's International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia

The International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) was a body of the United Nations that was established to prosecute the war crimes in the Yugoslav Wars, war crimes that had been committed during the Yugoslav Wars and to tr ...

for a variety of war crime

A war crime is a violation of the laws of war that gives rise to individual criminal responsibility for actions by combatants in action, such as intentionally killing civilians or intentionally killing prisoners of war, torture, taking hostage ...

s, including deportations and genocide.

Greece and Turkey

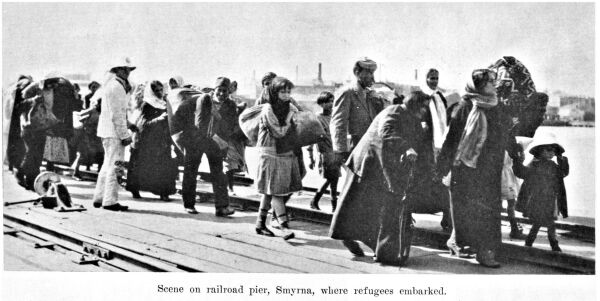

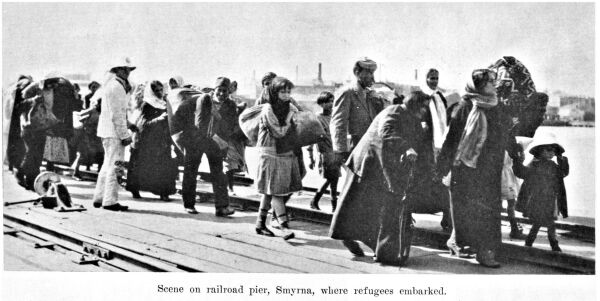

Following the Greco-Turkish War of 1919–1922, the League of Nations defined those to be mutually expelled as the "Muslim inhabitants of Greece" to Turkey and moving "the Christian Orthodox inhabitants of Turkey" to Greece. The plan met with fierce opposition in both countries and was condemned vigorously by a large number of countries. Undeterred,

Following the Greco-Turkish War of 1919–1922, the League of Nations defined those to be mutually expelled as the "Muslim inhabitants of Greece" to Turkey and moving "the Christian Orthodox inhabitants of Turkey" to Greece. The plan met with fierce opposition in both countries and was condemned vigorously by a large number of countries. Undeterred, Fridtjof Nansen

Fridtjof Wedel-Jarlsberg Nansen (; 10 October 1861 – 13 May 1930) was a Norwegian polymath and Nobel Peace Prize laureate. He gained prominence at various points in his life as an explorer, scientist, diplomat, humanitarian and co-founded the ...

worked with both Greece and Turkey to gain their acceptance of the proposed population exchange. About 1.5 million Christians and half a million Muslims were moved from one side of the international border to the other.

When the exchange was to take effect (1 May 1923), most of the prewar Orthodox Greek population of Aegean Turkey had already fled due to persecution and the Greek Genocide, and so only the Orthodox Christians of central Anatolia (both Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

and Turkish-speaking), and the Pontic Greeks

The Pontic Greeks (; or ; , , ), also Pontian Greeks or simply Pontians, are an ethnically Greek group indigenous to the region of Pontus, in northeastern Anatolia (modern-day Turkey). They share a common Pontic Greek culture that is di ...

were involved, a total of roughly 189,916. The total number of Muslims

Muslims () are people who adhere to Islam, a Monotheism, monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God ...

involved was 354,647.

The population transfer prevented further attacks on minorities in the respective states, and Nansen was awarded a Nobel Peace Prize

The Nobel Peace Prize (Swedish language, Swedish and ) is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the Will and testament, will of Sweden, Swedish industrialist, inventor, and armaments manufacturer Alfred Nobel, along with the prizes in Nobe ...

. As a result of the transfers, the Muslim minority in Greece and the Greek minority in Turkey were much reduced. Cyprus

Cyprus (), officially the Republic of Cyprus, is an island country in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Situated in West Asia, its cultural identity and geopolitical orientation are overwhelmingly Southeast European. Cyprus is the List of isl ...

and the Dodecanese

The Dodecanese (, ; , ''Dodekánisa'' , ) are a group of 15 larger and 150 smaller Greek islands in the southeastern Aegean Sea and Eastern Mediterranean, off the coast of Anatolia, of which 26 are inhabited. This island group generally define ...

were not included in the Greco-Turkish population transfer of 1923 because they were under direct British and Italian control respectively. For the fate of Cyprus

Cyprus (), officially the Republic of Cyprus, is an island country in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Situated in West Asia, its cultural identity and geopolitical orientation are overwhelmingly Southeast European. Cyprus is the List of isl ...

, see below. The Dodecanese became part of Greece in 1947.

Italy

In 1939, Hitler andMussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who, upon assuming office as Prime Minister, became the dictator of Fascist Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his overthrow in 194 ...

agreed to give the German-speaking population of South Tyrol a choice (the South Tyrol Option Agreement): they could emigrate to neighbouring Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

(including the recently annexed

Annexation, in international law, is the forcible acquisition and assertion of legal title over one state's territory by another state, usually following military occupation of the territory. In current international law, it is generally held to ...

Austria

Austria, formally the Republic of Austria, is a landlocked country in Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine Federal states of Austria, states, of which the capital Vienna is the List of largest cities in Aust ...

) or stay in Italy and accept to be assimilated. Because of the outbreak of World War II, the agreement was only partially consummated.

Cyprus

After theTurkish invasion of Cyprus

The Turkish invasion of Cyprus began on 20 July 1974 and progressed in two phases over the following month. Taking place upon a background of Cypriot intercommunal violence, intercommunal violence between Greek Cypriots, Greek and Turkish Cy ...

and subsequent division of the island, there was an agreement between the Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

representative on one side and the Turkish Cypriot

Turkish Cypriots or Cypriot Turks ( or ; ) are so called ethnic Turks originating from Cyprus. Turkish Cypriots are mainly Sunni Muslims. Following the Ottoman conquest of the island in 1571, about 30,000 Turkish settlers were given land onc ...

representative on the other side under the auspices of the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is the Earth, global intergovernmental organization established by the signing of the Charter of the United Nations, UN Charter on 26 June 1945 with the stated purpose of maintaining international peace and internationa ...

on August 2, 1975. The Government of the Republic of Cyprus would lift any restrictions in the voluntary movement of Turkish Cypriots to the Turkish-occupied areas of the island, and in exchange, the Turkish Cypriot side would allow all Greek Cypriots who remained in the occupied areas to stay there and to be given every help to live a normal life.

Around 150,000 people (amounting to more than one-quarter of the total population of Cyprus, and to one-third of its Greek Cypriot population) were displaced from the northern part of the island, where Greek Cypriots had constituted 80% of the population. Over the course of the next year, roughly 60,000 Turkish Cypriots

Turkish Cypriots or Cypriot Turks ( or ; ) are so called ethnic Turks originating from Cyprus. Turkish Cypriots are mainly Sunni Muslims. Following the Ottoman conquest of the island in 1571, about 30,000 Turkish settlers were given land onc ...

, amounting to half the Turkish Cypriot population, were displaced from the south to the north.

Soviet Union

Shortly before, during and immediately afterWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Dzhugashvili; 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and revolutionary who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

conducted a series of deportations on a huge scale, which profoundly affected the ethnic map of the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

. Over 1.5 million people were deported to Siberia

Siberia ( ; , ) is an extensive geographical region comprising all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has formed a part of the sovereign territory of Russia and its predecessor states ...

and the Central Asian

Central Asia is a region of Asia consisting of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. The countries as a group are also colloquially referred to as the "-stans" as all have names ending with the Persian language, Pers ...

republics. Separatism, resistance to Soviet rule and collaboration with the invading Germans were cited as the main official reasons for the deportations. After World War II, the population of East Prussia

East Prussia was a Provinces of Prussia, province of the Kingdom of Prussia from 1772 to 1829 and again from 1878 (with the Kingdom itself being part of the German Empire from 1871); following World War I it formed part of the Weimar Republic's ...

was replaced by the Soviet one, mainly by Russians

Russians ( ) are an East Slavs, East Slavic ethnic group native to Eastern Europe. Their mother tongue is Russian language, Russian, the most spoken Slavic languages, Slavic language. The majority of Russians adhere to Eastern Orthodox Church ...

. Many Tartari Muslims were transferred to Northern Crimea, now Ukraine, while Southern Crimea and Yalta were populated with Russians.

At the conclusion of the Yalta Conference

The Yalta Conference (), held 4–11 February 1945, was the World War II meeting of the heads of government of the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union to discuss the postwar reorganization of Germany and Europe. The three sta ...

, the Allies made numerous promises, one of them was their promise to return all Soviet

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

citizens who found themselves in the Allied zone to the Soviet Union (Operation Keelhaul

Operation Keelhaul was a forced repatriation of Soviet citizens and members of the Soviet Army in the West to the Soviet Union (although it often included former soldiers of the Russian Empire or Russian Republic, who did not have Soviet citizens ...

). That policy immediately affected the Soviet prisoners of war who were liberated by the Allies, and it was extended to all Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the Europe, European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural and socio-economic connotations. Its eastern boundary is marked by the Ural Mountain ...

an refugees

A refugee, according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), is a person "forced to flee their own country and seek safety in another country. They are unable to return to their own country because of feared persecution as ...

. Outlining the plan to force refugees to return to the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

, the codicil was kept secret from the American and British people for over 50 years.

Ukraine

Hundreds of thousands of Ukrainians have reportedly been forcibly deported to Russia during the2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine

On 24 February 2022, , starting the largest and deadliest war in Europe since World War II, in a major escalation of the Russo-Ukrainian War, conflict between the two countries which began in 2014. The fighting has caused hundreds of thou ...

. Because of Russia's deporting of thousands of Ukrainian children to Russia, the international criminal court issued an arrest warrant for Vladimir Putin

Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin (born 7 October 1952) is a Russian politician and former intelligence officer who has served as President of Russia since 2012, having previously served from 2000 to 2008. Putin also served as Prime Minister of Ru ...

the president of Russia and Maria Lvova-Belova Russia's commissioner for children's rights. As of 21 November 2023 there was 6,338,100 Ukrainian refugees fleeing the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Most (5,946,000) have gone to European countries but a minority (392,100) went to countries outside of Europe

In the Americas

Inca Empire

TheInca Empire

The Inca Empire, officially known as the Realm of the Four Parts (, ), was the largest empire in pre-Columbian America. The administrative, political, and military center of the empire was in the city of Cusco. The History of the Incas, Inca ...

dispersed conquered ethnic groups throughout the empire to break down traditional community ties and force the heterogeneous population to adopt the Quechua language

Quechua (, ), also called (, 'people's language') in Southern Quechua, is an Indigenous languages of the Americas, indigenous language family that originated in central Peru and thereafter spread to other countries of the Andes. Derived from ...

and culture. Never fully successful in the pre-Columbian

In the history of the Americas, the pre-Columbian era, also known as the pre-contact era, or as the pre-Cabraline era specifically in Brazil, spans from the initial peopling of the Americas in the Upper Paleolithic to the onset of European col ...

era, the totalitarian

Totalitarianism is a political system and a form of government that prohibits opposition from political parties, disregards and outlaws the political claims of individual and group opposition to the state, and completely controls the public sph ...

policies had their greatest success when they were adopted, from the 16th century, to create a pan-Andean identity defined against Spanish rule. Much of the current knowledge of Inca population transfers comes from their description by the Spanish chroniclers Pedro Cieza de León and Bernabé Cobo

Bernabé Cobo (born at Lopera in Spain, 1582; died at Lima, Peru, 9 October 1657) was a Spanish Jesuit missionary and writer. He played a part in the early history of quinine by his description of cinchona bark; he brought some to Europe on a vi ...

.

The Spanish conquerors continued these Inca policies settling for example thousands of indigenous yanakuna from what is today Ecuador, Bolivia and Peru in the newly conquered central Chile. In 1666 the Spanish resettled the Quilmes people from the vicinity of San Miguel de Tucumán

San Miguel de Tucumán (), usually called simply Tucumán, is the capital and largest city of Tucumán Province, located in northern Argentina from Buenos Aires. It is the fifth-largest city of Argentina after Buenos Aires, Córdoba, Argentin ...

more than 1,000 km southeast in Quilmes

Quilmes () is a city on the coast of the Rio de la Plata, in the , on the southeast end of the Greater Buenos Aires, being some away from the urban centre area of Buenos Aires. The city was founded in 1666 and is the seat of the eponymous '' ...

next to Buenos Aires

Buenos Aires, controlled by the government of the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires, is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Argentina. It is located on the southwest of the Río de la Plata. Buenos Aires is classified as an Alpha− glob ...

.

Canada

During theFrench and Indian War

The French and Indian War, 1754 to 1763, was a colonial conflict in North America between Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and Kingdom of France, France, along with their respective Native Americans in the United States, Native American ...

(the North American theatre of the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War, 1756 to 1763, was a Great Power conflict fought primarily in Europe, with significant subsidiary campaigns in North America and South Asia. The protagonists were Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and Kingdom of Prus ...

between Great Britain and France), the British forcibly relocated approximately 8,000 Acadians

The Acadians (; , ) are an ethnic group descended from the French colonial empire, French who settled in the New France colony of Acadia during the 17th and 18th centuries. Today, most descendants of Acadians live in either the Northern Americ ...

from the Canadian

Canadians () are people identified with the country of Canada. This connection may be residential, legal, historical or cultural. For most Canadians, many (or all) of these connections exist and are collectively the source of their being ''C ...

Maritime Provinces

The Maritimes, also called the Maritime provinces, is a region of Eastern Canada consisting of three provinces: New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward Island. The Maritimes had a population of 1,899,324 in 2021, which makes up 5.1% of ...

, first to the Thirteen Colonies

The Thirteen Colonies were the British colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America which broke away from the British Crown in the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783), and joined to form the United States of America.

The Thirteen C ...

and then to France. Thousands died of drowning, starvation, or illness as a result of the deportation. Some of the Acadians who had been relocated to France then emigrated to Louisiana

Louisiana ( ; ; ) is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It borders Texas to the west, Arkansas to the north, and Mississippi to the east. Of the 50 U.S. states, it ranks 31st in area and 25 ...

, where their descendants became part of the French-American cultural group known as Cajuns

The Cajuns (; Louisiana French language, French: ''les Cadjins'' or ''les Cadiens'' ), also known as Louisiana ''Acadians'' (French: ''les Acadiens''), are a Louisiana French people, Louisiana French ethnic group, ethnicity mainly found in t ...

.

Beginning with the Indian Act

The ''Indian Act'' () is a Canadian Act of Parliament that concerns registered Indians, their bands, and the system of Indian reserves. First passed in 1876 and still in force with amendments, it is the primary document that defines how t ...

, but underlying federal and provincial policies towards Indigenous peoples throughout the 1800s and 1900s, the Canadian Government pursued a deliberate policy of forced relocation against hundreds of Indigenous communities. The Canadian Indian residential school system

The Canadian Indian residential school system was a network of boarding schools for Indigenous peoples. The network was funded by the Canadian government's Department of Indian Affairs and administered by various Christian churches. The sch ...

and the Indian reserve

In Canada, an Indian reserve () or First Nations reserve () is defined by the '' Indian Act'' as a "tract of land, the legal title to which is vested in Her Majesty, that has been set apart by Her Majesty for the use and benefit of a band." ...

system (which forced Indigenous peoples off traditional territories and into small parcels of crown land in order to establish agricultural and industrial developments, and to begin the process of settler colonialism

Settler colonialism is a logic and structure of displacement by Settler, settlers, using colonial rule, over an environment for replacing it and its indigenous peoples with settlements and the society of the settlers.

Settler colonialism is ...

) are key to this history and have been seen by many scholars as evidence of the government's intent to "extinguish Aboriginal title through administrative and bureaucratic means". The efforts to displace Indigenous peoples from their traditional territories were also carried out by more brutal means. The Pass system, which controlled the supply of food and resources, movement in and out of reserve lands, and all other aspects of Indigenous peoples' lives, was implemented via the Indian Act in direct response to the 1885 North-West Rebellion

The North-West Rebellion (), was an armed rebellion of Métis under Louis Riel and an associated uprising of Cree and Assiniboine mostly in the District of Saskatchewan, against the Government of Canada, Canadian government. Important events i ...

, in which Cree, Metis, and other Indigenous peoples resisted the seizure of land and rights by the government. The North-West Mounted Police

The North-West Mounted Police (NWMP) was a Canadian paramilitary police force, established in 1873, to maintain order in the new Canadian North-West Territories (NWT) following the 1870 transfer of Rupert's Land and North-Western Territory to ...

, precursor to the Royal Canadian Mounted Police

The Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP; , GRC) is the Law enforcement in Canada, national police service of Canada. The RCMP is an agency of the Government of Canada; it also provides police services under contract to 11 Provinces and terri ...

, were likewise established as a direct response to Indigenous resistance against colonialism. Their purview was to carry out John A. Macdonald, John A. Macdonald's colonial and national policies, especially in Rupert's Land, what would become the Prairie provinces.

The High Arctic relocation took place during the Cold War in the 1950s, when 87 Inuit were moved by the Government of Canada to the High Arctic. The relocation has been a source of controversy, and is an understudied aspect of forced migration instigated by the Canadian federal government to assert its sovereignty in the Northern Canada#Sub-divisions, Far North against the Soviet Union. Relocated Inuit peoples were not given sufficient support and were not given a say in their relocation.

Numerous other indigenous peoples of Canada have been forced to relocate their communities to different reserve lands, including the 'Nak'waxda'xw in 1964.

Japanese Canadian internment

Japanese Canadian Internment refers to the detainment of Japanese Canadians following the attack on Pearl Harbor and the Canadian declaration of war on Japan during World War II. The forced relocation subjected Japanese Canadians to government-enforced curfews and interrogations and job and property losses. The internment of Japanese Canadians was ordered by Prime Minister Mackenzie King, largely because of existing racism. However, evidence supplied by theRoyal Canadian Mounted Police

The Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP; , GRC) is the Law enforcement in Canada, national police service of Canada. The RCMP is an agency of the Government of Canada; it also provides police services under contract to 11 Provinces and terri ...

and the Department of National Defence (Canada), Department of National Defence show that the decision was unwarranted.

Until 1949, four years after World War II had ended, all persons of Japanese heritage were systematically removed from their homes and businesses and sent to internment camps. The Canadian government shut down all Japanese-language newspapers, took possession of businesses and fishing boats, and effectively sold them. To fund the internment itself, vehicles, houses, and personal belongings were also sold.

United States

Independence

During and after theAmerican Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was the armed conflict that comprised the final eight years of the broader American Revolution, in which Am ...

, many United Empire Loyalist, Loyalists were deprived of life, liberty or property or suffered lesser physical harm, sometimes under Act of Attainder#American usage, acts of attainder and sometimes by main force. Parker Wickham and other Loyalists developed a well-founded fear. As a result, many chose or were forced to leave their former homes in what became the United States, often going to Canada, where the Crown promised them land in an effort at compensation and resettlement. Most were given land on the frontier in what became Upper Canada and had to create new towns. The communities were largely settled by people of the same ethnic ancestry and religious faith. In some cases, towns were started by men of particular military units and their families.

Native American relocations