First Battle Of Groix on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Cornwallis's Retreat was a naval engagement during the

Captain Robert Stopford on ''Phaeton'' signaled to Cornwallis that the French fleet contained 30 vessels, but did not return to join Cornwallis, causing the British admiral to misunderstand the signal to mean that the French ships, while more numerous than his own, were of inferior strength. Under this misapprehension, Cornwallis, who could only see the ship's sails rather than their hulls, ordered his squadron to advance on the French fleet. Stopford subsequently signaled the exact composition of Villaret's fleet at 11:00 and Cornwallis, realising his error, issued urgent orders for his squadron to haul away to the southwest, tacking to starboard in an effort to escape pursuit with ''Brunswick'' leading the line, followed by ''Royal Sovereign'', ''Bellerophon'', ''Triumph'' and ''Mars''.Clowes, p. 257 ''Phaeton'' was sent to scout ahead, while ''Pallas'' was ordered to keep company with ''Royal Sovereign'' in order to relay Cornwallis's signals to the rest of the squadron. Villaret had immediately ordered his fleet to give chase, and the French followed the British south westwards into the Atlantic, taking advantage of the strengthening wind.

At 14:00 Villaret split his forces, one division sailing northwards to take advantage of the breeze coming off the land, while the other maintained passage to the south. Cornwallis tacked his squadron at 06:00 and 17:00, but Villaret de Joyeuse's plan worked well and a shift in the wind at 18:00 allowed the northern squadron to weather and the southern to lay up, the British squadron now lying directly between them about from either French division.James, p. 239 During the night the chase continued into the Atlantic, the British squadron struggling to maintain formation due to the slow speed of two members: ''Brunswick''

Captain Robert Stopford on ''Phaeton'' signaled to Cornwallis that the French fleet contained 30 vessels, but did not return to join Cornwallis, causing the British admiral to misunderstand the signal to mean that the French ships, while more numerous than his own, were of inferior strength. Under this misapprehension, Cornwallis, who could only see the ship's sails rather than their hulls, ordered his squadron to advance on the French fleet. Stopford subsequently signaled the exact composition of Villaret's fleet at 11:00 and Cornwallis, realising his error, issued urgent orders for his squadron to haul away to the southwest, tacking to starboard in an effort to escape pursuit with ''Brunswick'' leading the line, followed by ''Royal Sovereign'', ''Bellerophon'', ''Triumph'' and ''Mars''.Clowes, p. 257 ''Phaeton'' was sent to scout ahead, while ''Pallas'' was ordered to keep company with ''Royal Sovereign'' in order to relay Cornwallis's signals to the rest of the squadron. Villaret had immediately ordered his fleet to give chase, and the French followed the British south westwards into the Atlantic, taking advantage of the strengthening wind.

At 14:00 Villaret split his forces, one division sailing northwards to take advantage of the breeze coming off the land, while the other maintained passage to the south. Cornwallis tacked his squadron at 06:00 and 17:00, but Villaret de Joyeuse's plan worked well and a shift in the wind at 18:00 allowed the northern squadron to weather and the southern to lay up, the British squadron now lying directly between them about from either French division.James, p. 239 During the night the chase continued into the Atlantic, the British squadron struggling to maintain formation due to the slow speed of two members: ''Brunswick''' s sailing deficiencies had already been noted, but it became clear that ''Bellerophon'' was similarly suffering. In an effort to decrease the weight of the ships and thus increase their speed and allow them to keep pace with the rest of the squadron, captains Lord Charles Fitzgerald and Lord Cranstoun ordered the anchors, boats and much of the provisions and fresh water carried aboard to be thrown over the side: ''Bellerophon'' was sailing so slowly that Cranstoun even ordered four

Following the reorganisation, the entire British squadron was now within range of the leading French ships, all firing at Villaret's advancing line. To facilitate the positioning of more cannon in the stern of the vessels, the British captains ordered their men to cut holes in the stern planks: so many were cut that several ships needed extensive repairs in the aftermath of the action and ''Triumph'' especially had much of her stern either cut or shot away.Clowes, p. 258 At 13:30 the British fire achieved some success when ''Zélé'' fell back with damaged rigging, allowing the second French ship to take up the position at the head of the line. This ship, which had been firing distantly on the British force for half an hour, opened a heavy fire on ''Mars'' as did a number of following French ships over the ensuing hours, including ''Droits de l’Homme'', ''Formidable'' and ''Tigre''.Rouvier, p. 207 This combined attack left ''Mars'' badly damaged in the rigging and sails, causing the ship to slow. Cotton's ship now seemed at serious risk of falling into the midst of the French fleet and being overwhelmed, while Captain Gower's ''Triumph'' was also badly damaged by French shot. Seeing the danger his rearguard was in, Cornwallis took decisive action, ordering Cotton to turn away from the French and swinging ''Royal Sovereign'' southwards, he led ''Triumph'' to ''Mars''

Following the reorganisation, the entire British squadron was now within range of the leading French ships, all firing at Villaret's advancing line. To facilitate the positioning of more cannon in the stern of the vessels, the British captains ordered their men to cut holes in the stern planks: so many were cut that several ships needed extensive repairs in the aftermath of the action and ''Triumph'' especially had much of her stern either cut or shot away.Clowes, p. 258 At 13:30 the British fire achieved some success when ''Zélé'' fell back with damaged rigging, allowing the second French ship to take up the position at the head of the line. This ship, which had been firing distantly on the British force for half an hour, opened a heavy fire on ''Mars'' as did a number of following French ships over the ensuing hours, including ''Droits de l’Homme'', ''Formidable'' and ''Tigre''.Rouvier, p. 207 This combined attack left ''Mars'' badly damaged in the rigging and sails, causing the ship to slow. Cotton's ship now seemed at serious risk of falling into the midst of the French fleet and being overwhelmed, while Captain Gower's ''Triumph'' was also badly damaged by French shot. Seeing the danger his rearguard was in, Cornwallis took decisive action, ordering Cotton to turn away from the French and swinging ''Royal Sovereign'' southwards, he led ''Triumph'' to ''Mars''' s rescue, drawing close alongside and engaging the leading French ships with a series of broadsides from his powerful first rate. The raking fire of ''Royal Sovereign'' caused the four French ships closing on ''Mars'' to retreat, and gradually the entire French fleet fell back, distant firing continuing until 18:10 when the French fell out of range, although they continued in pursuit of the battered and weakened British squadron.

At 18:40, suddenly and for no immediately apparent reason, Villaret ordered his ships to haul their wind and turn back towards the east, breaking off contact. By the time the sun set a few hours later, the French had almost disappeared over the eastern horizon as the British continued westwards.James, p. 241 Although the order to abandon the action has subsequently been much debated, the cause of Villaret's retreat was in fact the actions of the frigate ''Phaeton'', which Cornwallis had sent ahead of the squadron as a scout early on 17 June. After progressing several miles ahead of the British squadron, Stopford had signalled that there were unknown sails to the northwest, followed by signals indicating four ships in sight and then one for a full fleet, highlighted by firing two cannon. Stopford had been careful to ensure that the French ships could see and read his signals, which were in a code that the French were known to have broken, and Villaret knew well that the only French fleet in those waters was the one he led. He therefore assumed that ''Phaeton'' could see the Channel Fleet beyond the northern horizon, a force significantly more powerful than his own. Stopford compounded the ruse at 15:00 by making a string of nonsensical signals to the non-existent fleet before notifying Cornwallis at 16:30, again in plain sight, that the fleet was composed of allied ships of the line. He completed the operation by raising the

''

French Revolutionary Wars

The French Revolutionary Wars () were a series of sweeping military conflicts resulting from the French Revolution that lasted from 1792 until 1802. They pitted French First Republic, France against Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain, Habsb ...

in which a British Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

squadron of five ships of the line

A ship of the line was a type of naval warship constructed during the Age of Sail from the 17th century to the mid-19th century. The ship of the line was designed for the naval tactic known as the line of battle, which involved the two column ...

and two frigates

A frigate () is a type of warship. In different eras, the roles and capabilities of ships classified as frigates have varied.

The name frigate in the 17th to early 18th centuries was given to any full-rigged ship built for speed and maneuvera ...

was attacked by a much larger French Navy

The French Navy (, , ), informally (, ), is the Navy, maritime arm of the French Armed Forces and one of the four military service branches of History of France, France. It is among the largest and most powerful List of navies, naval forces i ...

fleet of 12 ships of the line and 11 frigates. The action took place in the waters off the west coast of Brittany

Brittany ( ) is a peninsula, historical country and cultural area in the north-west of modern France, covering the western part of what was known as Armorica in Roman Gaul. It became an Kingdom of Brittany, independent kingdom and then a Duch ...

on 16–17 June 1795 (28–29 Prairial an III of the French Republican Calendar).

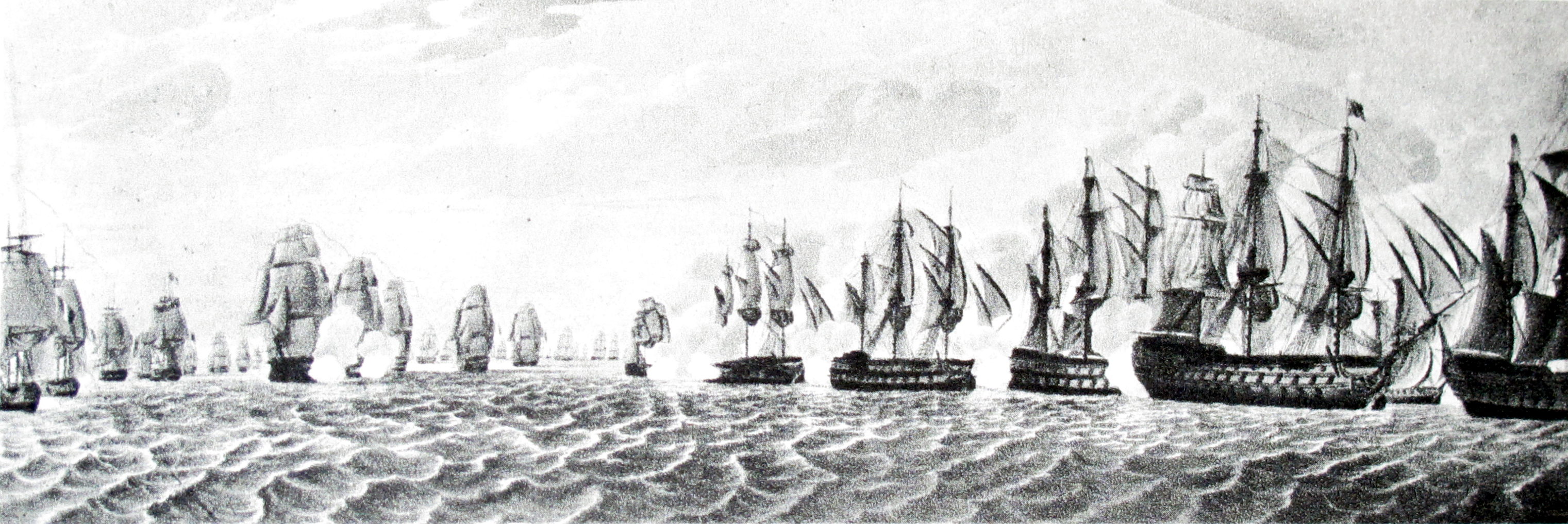

A British naval squadron under Vice-Admiral William Cornwallis began operating off Brittany on 7 June; in the following week he attacked a French merchant convoy and captured several ships. In response, Vice-admiral Louis Thomas Villaret de Joyeuse led the main French fleet out of port to attack the British, who were spotted on 16 June. Heavily outnumbered, Cornwallis turned away from the French and attempted to escape into open water, with the French fleet in pursuit. After a full day's chase the British squadron lost speed, due to poorly loaded holds on two of their ships, and the French vanguard pulled within range on the morning of 17 June. Unwilling to abandon his rearguard, Cornwallis counter-attacked with the rest of his squadron. A fierce combat developed, culminating in Cornwallis interposing his flagship between the British and French forces.

Cornwallis's determined resistance, and his squadron's signals to a group of unknown ships spotted in the distance, led Villaret de Joyeuse to believe that the main British Channel Fleet

The Channel Fleet and originally known as the Channel Squadron was the Royal Navy formation of warships that defended the waters of the English Channel from 1854 to 1909 and 1914 to 1915.

History

Throughout the course of Royal Navy's history th ...

was approaching. Villaret therefore broke off the battle on the evening of 17 June and ordered his ships to withdraw. This allowed Cornwallis to escape; he returned to port at Plymouth

Plymouth ( ) is a port city status in the United Kingdom, city and unitary authority in Devon, South West England. It is located on Devon's south coast between the rivers River Plym, Plym and River Tamar, Tamar, about southwest of Exeter and ...

with his squadron battered but intact. Villaret withdrew to an anchorage off Belle Île

Belle-Île (), Belle-Île-en-Mer (), or Belle Isle (, ; ) is a French island off the coast of Brittany in the ''département in France, département'' of Morbihan, and the largest of Brittany's islands. It is from the Quiberon peninsula.

Admini ...

, close to the naval base at Brest. The French fleet was discovered there by the main British Channel Fleet on 22 June and defeated at the ensuing Battle of Groix

The Battle of Groix (, ) took place on 23 June 1795 off the island of Groix in the Bay of Biscay during the War of the First Coalition. It was fought between elements of the British Channel Fleet and the French Ponant Fleet, Atlantic Fleet, whi ...

, losing three ships of the line. Villaret was criticised by contemporaries for failing to press the attack on Cornwallis's force, whilst the British admiral was praised and rewarded for his defiance in the face of overwhelming French numerical superiority. The battle has since been considered by British historians to be one of the most influential examples "of united courage and coolness to be found in ritishnaval history".

Background

By the late spring of 1795 Britain and France had been at war for more than two years, with the BritishRoyal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

's Channel Fleet

The Channel Fleet and originally known as the Channel Squadron was the Royal Navy formation of warships that defended the waters of the English Channel from 1854 to 1909 and 1914 to 1915.

History

Throughout the course of Royal Navy's history th ...

, known at the time as the "Western Squadron" exerting superiority in the campaign for dominance in the Bay of Biscay

The Bay of Biscay ( ) is a gulf of the northeast Atlantic Ocean located south of the Celtic Sea. It lies along the western coast of France from Point Penmarc'h to the Spanish border, and along the northern coast of Spain, extending westward ...

and the Western Approaches

The Western Approaches is an approximately rectangular area of the Atlantic Ocean lying immediately to the west of Ireland and parts of Great Britain. Its north and south boundaries are defined by the corresponding extremities of Britain. The c ...

. The British, led first by Lord Howe and then by Lord Bridport sailing from their bases at Plymouth

Plymouth ( ) is a port city status in the United Kingdom, city and unitary authority in Devon, South West England. It is located on Devon's south coast between the rivers River Plym, Plym and River Tamar, Tamar, about southwest of Exeter and ...

, Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port city status in the United Kingdom, city and unitary authority in Hampshire, England. Most of Portsmouth is located on Portsea Island, off the south coast of England in the Solent, making Portsmouth the only city in En ...

and Torbay

Torbay is a unitary authority with a borough status in the ceremonial county of Devon, England. It is governed by Torbay Council, based in the town of Torquay, and also includes the towns of Paignton and Brixham. The borough consists of ...

, maintained an effective distant blockade

A blockade is the act of actively preventing a country or region from receiving or sending out food, supplies, weapons, or communications, and sometimes people, by military force.

A blockade differs from an embargo or sanction, which are ...

against the French naval bases on the Atlantic, especially the large harbour of Brest in Brittany

Brittany ( ) is a peninsula, historical country and cultural area in the north-west of modern France, covering the western part of what was known as Armorica in Roman Gaul. It became an Kingdom of Brittany, independent kingdom and then a Duch ...

.Gardiner, p. 46 Although French squadrons could occasionally put to sea without interception, the main French fleet had suffered a series of setbacks in the preceding two years, most notably at the battle of the Glorious First of June

The Glorious First of June, also known as the Fourth Battle of Ushant, (known in France as the or ) was fought on 1 June 1794 between the British and French navies during the War of the First Coalition. It was the first and largest fleet a ...

in 1794 at which the fleet lost seven ships of the line

A ship of the line was a type of naval warship constructed during the Age of Sail from the 17th century to the mid-19th century. The ship of the line was designed for the naval tactic known as the line of battle, which involved the two column ...

and then during the '' Croisière du Grand Hiver'' during the winter of 1794–1795 when five ships of the line were wrecked during a sortie into the Bay of Biscay at the height of the Atlantic winter storm season.Gardiner, p. 16

The damage the French Trans-Atlantic fleet had suffered in the winter operation took months to repair and it was not in a condition to sail again until June 1795, although several squadrons had put to sea in the meanwhile. One such squadron consisted of three ships of the line and a number of frigates under Counter-admiral Jean Gaspard Vence sent to Bordeaux

Bordeaux ( ; ; Gascon language, Gascon ; ) is a city on the river Garonne in the Gironde Departments of France, department, southwestern France. A port city, it is the capital of the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region, as well as the Prefectures in F ...

to escort a merchant convoy up the coast to Brest.Clowes, p. 255 The British Channel Fleet had briefly sortied from Torbay in February in response to the ''Croisière du Grand Hiver'' and subsequently retired to Spithead

Spithead is an eastern area of the Solent and a roadstead for vessels off Gilkicker Point in Hampshire, England. It is protected from all winds except those from the southeast, with the Isle of Wight lying to the south-west. Spithead and the ch ...

, from where a squadron of five ships of the line and two frigates were sent on 30 May to patrol the approaches to Brest and to watch the French fleet. The force consisted of the 100-gun first-rate

In the rating system of the Royal Navy used to categorise sailing warships, a first rate was the designation for the largest ships of the line. Originating in the Jacobean era with the designation of Ships Royal capable of carrying at least ...

ship of the line HMS ''Royal Sovereign'', the 74-gun ships of the line HMS ''Mars'', HMS ''Triumph'', HMS ''Brunswick'' and HMS ''Bellerophon'', the frigates HMS ''Phaeton'' and HMS ''Pallas'' and the small brig-sloop

During the 18th and 19th centuries, a sloop-of-war was a warship of the Royal Navy with a single gun deck that carried up to 18 guns. The rating system of the Royal Navy covered all vessels with 20 or more guns; thus, the term encompassed all ...

HMS ''Kingfisher'', under the overall command of Vice-Admiral William Cornwallis in ''Royal Sovereign''.James, p. 237 Cornwallis was a highly experienced naval officer who had been in service with the Navy since 1755 and fought in the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War, 1756 to 1763, was a Great Power conflict fought primarily in Europe, with significant subsidiary campaigns in North America and South Asia. The protagonists were Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and Kingdom of Prus ...

and the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was the armed conflict that comprised the final eight years of the broader American Revolution, in which Am ...

, including the significant naval victories over the French at the Battle of Quiberon Bay

The Battle of Quiberon Bay (known as the ''Bataille des Cardinaux'' by the French) was a decisive naval engagement during the Seven Years' War. It was fought on 20 November 1759 between the Royal Navy and the French Navy in Quiberon Bay, off ...

in 1759 and the Battle of the Saintes

The Battle of the Saintes (known to the French as the Bataille de la Dominique), also known as the Battle of Dominica, was an important naval battle in the Caribbean between the British and the French that took place 9–12 April 1782. The Brit ...

in 1782.

Operations off Belle Île

Cornwallis led his squadron southwest, roundingUshant

Ushant (; , ; , ) is a French island at the southwestern end of the English Channel which marks the westernmost point of metropolitan France. It belongs to Brittany and in medieval times, Léon. In lower tiers of government, it is a commune in t ...

on the night of 7–8 June and cruising southwards down the Breton coast past the Penmarck Rocks. At 10:30 that morning, Captain Sir Erasmus Gower on ''Triumph'' signalled that he could see six sails to the northeast. Cornwallis turned the squadron to investigate, and discovered the small squadron under Vence in command of a large merchant convoy. Vence initially held his course when Cornwallis's squadron appeared, in the belief that they were French. When he realised his mistake at 12:00, he ordered his ships to make all sail towards the anchorage in the shelter of the fortified island of Belle Île

Belle-Île (), Belle-Île-en-Mer (), or Belle Isle (, ; ) is a French island off the coast of Brittany in the ''département in France, département'' of Morbihan, and the largest of Brittany's islands. It is from the Quiberon peninsula.

Admini ...

.Brenton, p. 229 Vence's squadron made rapid progress towards the anchorage, but Cornwallis had sent his faster ships ahead, ''Phaeton'', ''Kingfisher'' and ''Triumph'' in the lead, while ''Brunswick'', which had been badly loaded when at anchor in Spithead and thus was unable to sail smoothly, fell far behind. The leading British ships were able to fire on Vence's force at a distance, and attacked the trailing merchant ships and their frigate escorts, forcing a French frigate to abandon a merchant ship it had under tow, but could not bring Vence to action without the support of the slower vessels in Cornwallis's squadron.Clowes, p. 256 As a result, all of the French warships and all but eight of the merchant vessels were safely anchored at Belle Île. ''Triumph'' and ''Phaeton'' both advanced on the anchored ships, but came under heavy fire from batteries on the island and found that the water was too shallow and the passage too uncertain to risk their ships. ''Phaeton'' lost one man killed and seven wounded before Cornwallis called off the attack.

Taking his eight prizes laden with wine and brandy, Cornwallis retired to the sheltered anchorage of Palais Road, close to Belle Île, where the squadron remained until 9 June. In the evening, Cornwallis took advantage of a fresh breeze to sail his ships out into the Bay of Biscay and around the Ushant headland, reaching the Scilly Isles

The Isles of Scilly ( ; ) are a small archipelago off the southwestern tip of Cornwall, England. One of the islands, St Agnes, is over farther south than the most southerly point of the British mainland at Lizard Point, and has the souther ...

on 11 June and sending ''Kingfisher'' back to Spithead with the French prizes and two American merchant ships seized in French waters. Cornwallis then ordered the squadron to turn back to the blockade of Brest in the hope of encountering Vence in more favourable circumstances. At Brest, messages had arrived warning that Vence and the convoy were "blockaded" at Belle Île and the French commander was instructed to rescue him. In fact, as was pointed out by a number of officers in the French fleet including Vice-admiral Yves-Joseph de Kerguelen-Trémarec

Rear-Admiral Yves Joseph Marie de Kerguelen-Trémarec (13 February 1734 – 3 March 1797) was a French Navy officer. He discovered the Kerguelen Islands in 1772 during his first expedition to the southern Indian Ocean. Welcomed as a hero after h ...

, the anchorage at Belle Île could never be effectively blockaded as it was too open to block all potential approaches and too close to the major port of Lorient

Lorient (; ) is a town (''Communes of France, commune'') and Port, seaport in the Morbihan Departments of France, department of Brittany (administrative region), Brittany in western France.

History

Prehistory and classical antiquity

Beginn ...

and therefore a rescue was unnecessary.James, p. 238 This advice was ignored, and Vice-admiral Louis Thomas Villaret de Joyeuse sailed from Brest on 12 June with the ships that were anchored in Brest Roads ready for sea. Villaret's fleet consisted of nine ships of the line, nine frigates (including two ships of the line razee

A razee or razée is a sailing ship that has been cut down (''razeed'') to reduce the number of decks. The word is derived from the French ''vaisseau rasé'', meaning a razed (in the sense of shaved down) ship.

Seventeenth century

During the ...

d into 50-gun frigates) and four corvette

A corvette is a small warship. It is traditionally the smallest class of vessel considered to be a proper (or " rated") warship. The warship class above the corvette is that of the frigate, while the class below was historically that of the sloo ...

s.

On 15 June, the French fleet encountered Vence's squadron sailing off the island of Groix near Lorient

Lorient (; ) is a town (''Communes of France, commune'') and Port, seaport in the Morbihan Departments of France, department of Brittany (administrative region), Brittany in western France.

History

Prehistory and classical antiquity

Beginn ...

, and the two joined, Vence having sent the remainder of his convoy safely to Brest while Villaret was ''en route''. Turning north back towards Brest, the French fleet was off Penmarck Point at 10:30 on 16 June with the wind in the northwest, when sails were spotted to the northwest. This force was Cornwallis's squadron, returning to Belle Île in search of Vence. Sighting his numerically inferior opponent to windward, Villaret immediately ordered his fleet to advance on the British force while Cornwallis, anticipating Vence's merchant convoy and not immediately apprehending the danger his squadron was in, sent ''Phaeton'' to investigate the sails on the horizon.Tracy, p. 121

Retreat

Captain Robert Stopford on ''Phaeton'' signaled to Cornwallis that the French fleet contained 30 vessels, but did not return to join Cornwallis, causing the British admiral to misunderstand the signal to mean that the French ships, while more numerous than his own, were of inferior strength. Under this misapprehension, Cornwallis, who could only see the ship's sails rather than their hulls, ordered his squadron to advance on the French fleet. Stopford subsequently signaled the exact composition of Villaret's fleet at 11:00 and Cornwallis, realising his error, issued urgent orders for his squadron to haul away to the southwest, tacking to starboard in an effort to escape pursuit with ''Brunswick'' leading the line, followed by ''Royal Sovereign'', ''Bellerophon'', ''Triumph'' and ''Mars''.Clowes, p. 257 ''Phaeton'' was sent to scout ahead, while ''Pallas'' was ordered to keep company with ''Royal Sovereign'' in order to relay Cornwallis's signals to the rest of the squadron. Villaret had immediately ordered his fleet to give chase, and the French followed the British south westwards into the Atlantic, taking advantage of the strengthening wind.

At 14:00 Villaret split his forces, one division sailing northwards to take advantage of the breeze coming off the land, while the other maintained passage to the south. Cornwallis tacked his squadron at 06:00 and 17:00, but Villaret de Joyeuse's plan worked well and a shift in the wind at 18:00 allowed the northern squadron to weather and the southern to lay up, the British squadron now lying directly between them about from either French division.James, p. 239 During the night the chase continued into the Atlantic, the British squadron struggling to maintain formation due to the slow speed of two members: ''Brunswick''

Captain Robert Stopford on ''Phaeton'' signaled to Cornwallis that the French fleet contained 30 vessels, but did not return to join Cornwallis, causing the British admiral to misunderstand the signal to mean that the French ships, while more numerous than his own, were of inferior strength. Under this misapprehension, Cornwallis, who could only see the ship's sails rather than their hulls, ordered his squadron to advance on the French fleet. Stopford subsequently signaled the exact composition of Villaret's fleet at 11:00 and Cornwallis, realising his error, issued urgent orders for his squadron to haul away to the southwest, tacking to starboard in an effort to escape pursuit with ''Brunswick'' leading the line, followed by ''Royal Sovereign'', ''Bellerophon'', ''Triumph'' and ''Mars''.Clowes, p. 257 ''Phaeton'' was sent to scout ahead, while ''Pallas'' was ordered to keep company with ''Royal Sovereign'' in order to relay Cornwallis's signals to the rest of the squadron. Villaret had immediately ordered his fleet to give chase, and the French followed the British south westwards into the Atlantic, taking advantage of the strengthening wind.

At 14:00 Villaret split his forces, one division sailing northwards to take advantage of the breeze coming off the land, while the other maintained passage to the south. Cornwallis tacked his squadron at 06:00 and 17:00, but Villaret de Joyeuse's plan worked well and a shift in the wind at 18:00 allowed the northern squadron to weather and the southern to lay up, the British squadron now lying directly between them about from either French division.James, p. 239 During the night the chase continued into the Atlantic, the British squadron struggling to maintain formation due to the slow speed of two members: ''Brunswick''carronades

A carronade is a short, smoothbore, cast iron, cast-iron cannon which was used by the Royal Navy. It was first produced by the Carron Company, an ironworks in Falkirk, Scotland, and was used from the last quarter of the 18th century to the mid- ...

to be jettisoned with a large amount of roundshot.

During the night Villaret had split his forces further, creating a windward division of three ships of the line and five frigates, a centre division of five ships of the line and four frigates and the lee division of four ships of the line, five frigates and three smaller vessels. Of these forces, the weather division was closest to Cornwallis's squadron and at 09:00 the leading French ship '' Zélé'' began to fire on the British rearguard ship, ''Mars'' under Captain Sir Charles Cotton. Cotton returned fire with his stern-chasers, but was unable to prevent the 40-gun frigate '' Virginie'' from approaching his ship's port quarter and firing repeated broadsides at ''Mars''. The rest of the French frigates held station to windward of the British force without approaching within range. Concerned that ''Bellerophon'', which was close to the developing action, might lose a sail, a loss that Cranstoun would be unable to replace, Cornwallis ordered ''Triumph'' and ''Royal Sovereign'' to fall back and allow ''Bellerophon'' to join ''Brunswick'' in the vanguard.James, p. 240

Following the reorganisation, the entire British squadron was now within range of the leading French ships, all firing at Villaret's advancing line. To facilitate the positioning of more cannon in the stern of the vessels, the British captains ordered their men to cut holes in the stern planks: so many were cut that several ships needed extensive repairs in the aftermath of the action and ''Triumph'' especially had much of her stern either cut or shot away.Clowes, p. 258 At 13:30 the British fire achieved some success when ''Zélé'' fell back with damaged rigging, allowing the second French ship to take up the position at the head of the line. This ship, which had been firing distantly on the British force for half an hour, opened a heavy fire on ''Mars'' as did a number of following French ships over the ensuing hours, including ''Droits de l’Homme'', ''Formidable'' and ''Tigre''.Rouvier, p. 207 This combined attack left ''Mars'' badly damaged in the rigging and sails, causing the ship to slow. Cotton's ship now seemed at serious risk of falling into the midst of the French fleet and being overwhelmed, while Captain Gower's ''Triumph'' was also badly damaged by French shot. Seeing the danger his rearguard was in, Cornwallis took decisive action, ordering Cotton to turn away from the French and swinging ''Royal Sovereign'' southwards, he led ''Triumph'' to ''Mars''

Following the reorganisation, the entire British squadron was now within range of the leading French ships, all firing at Villaret's advancing line. To facilitate the positioning of more cannon in the stern of the vessels, the British captains ordered their men to cut holes in the stern planks: so many were cut that several ships needed extensive repairs in the aftermath of the action and ''Triumph'' especially had much of her stern either cut or shot away.Clowes, p. 258 At 13:30 the British fire achieved some success when ''Zélé'' fell back with damaged rigging, allowing the second French ship to take up the position at the head of the line. This ship, which had been firing distantly on the British force for half an hour, opened a heavy fire on ''Mars'' as did a number of following French ships over the ensuing hours, including ''Droits de l’Homme'', ''Formidable'' and ''Tigre''.Rouvier, p. 207 This combined attack left ''Mars'' badly damaged in the rigging and sails, causing the ship to slow. Cotton's ship now seemed at serious risk of falling into the midst of the French fleet and being overwhelmed, while Captain Gower's ''Triumph'' was also badly damaged by French shot. Seeing the danger his rearguard was in, Cornwallis took decisive action, ordering Cotton to turn away from the French and swinging ''Royal Sovereign'' southwards, he led ''Triumph'' to ''Mars''Dutch flag

The national flag of the Netherlands () is a horizontal tricolour of red, white, and blue. The current design originates as a variant of the late 16th century orange-white-blue '' Prinsenvlag'' ("Prince's Flag"), evolving in the early 17th ...

and signalling for the non-existent fleet to join with Cornwallis. It is not clear to what extent Villaret was taken in by this charade, the French fleet continuing their attack without pause, until at 18:00 when a number of sails appeared on the northwest horizon. At this point ''Phaeton'' wore round to return to Cornwallis, and Villaret, now convinced that the strangers, which were in reality a small convoy of merchant vessels, were the vanguard of the Channel Fleet, abandoned the chase.Woodman, p. 60

Aftermath

With the French fleet out of sight, Cornwallis ordered his squadron north against the northeast wind, returning through the English Channel toPlymouth

Plymouth ( ) is a port city status in the United Kingdom, city and unitary authority in Devon, South West England. It is located on Devon's south coast between the rivers River Plym, Plym and River Tamar, Tamar, about southwest of Exeter and ...

for repairs. ''Phaeton'' was sent ahead with despatches intended to warn Lord Bridport that the French fleet was at sea and inform him of Cornwallis's safety. However, Bridport had already sailed on 12 June with 15 ships of the line as a cover for a secondary force detailed to land a British and French Royalist army at Quiberon Bay

Quiberon Bay (, ; ) is an area of sheltered water on the south coast of Brittany. The bay is in the Morbihan département.

Geography

The bay is roughly triangular in shape, open to the south with the Gulf of Morbihan to the north-east and the ...

, and the main British fleet was already off Brest when the action between Cornwallis and Villaret de Joyeuse was fought.James, p. 244 The ships of Cornwallis's squadron had all suffered damage, especially ''Triumph'' and ''Mars'': ''Triumph'' had to have extensive repairs to its stern, which had been heavily cut away during the action. Historian Edward Pelham Brenton credits this action with influencing Robert Seppings

Sir Robert Seppings, FRS (11 December 176725 April 1840) was an English naval architect. His experiments with diagonal trusses in the construction of ships led to his appointment as Surveyor of the Navy in 1813, a position he held until 1835.

...

in his future designs of ships of the line, providing rounded sterns that offered a wider field of fire at pursuing warships. Casualties were light however, with just 12 men wounded on ''Mars'' and no other losses on the remainder of the squadron.

The French fleet was only lightly damaged and had only taken light casualties of 29 men killed and wounded. Villaret continued the fleet's passage eastwards, rounding Penmarck Point and entering Audierne

Audierne (; ) is a commune in the Finistère department of Brittany in northwestern France. On 1 January 2016 the former commune of Esquibien merged into Audierne.gale

A gale is a strong wind; the word is typically used as a descriptor in nautical contexts. The U.S. National Weather Service defines a gale as sustained surface wind moving at a speed between .

, driving the French fleet southwards and dispersing them across the coastline. Over the ensuing days Villaret was able to reconstitute his fleet in the anchorage off Belle Île where Vence had laid up on 8 June.Clowes, p. 260 When the fleet was all assembled, Villaret again ordered it to sail north in an effort to regain Brest. His fleet had originally sailed from Brest in such a rush due to the perceived danger to Vence's squadron that it was only carrying 15 days worth of provisions on board and had now been at sea for ten days, making a return to Brest a priority. At 03:30 on 22 June, as the French fleet passed north along the coast, the British Channel Fleet appeared to the northwest, Bridport having discovered the French fleet absent from Brest and cast southwards to protect the Quiberon invasion convoy.

Villaret considered the newly arrived British fleet to be significantly superior to his own and retreated before it, sailing towards the French coast with the intention of sheltering in the protected coastal waters around the island of Groix and returning to Brest from this position.James, p. 245 Bridport instructed his fleet to pursue the French force, and a chase developed lasting the day of 22 June and into the early morning of 23 June, when Bridport's leading ships caught the stragglers at the rear of Villaret's fleet off the island. In a sharp engagement known as the Battle of Groix

The Battle of Groix (, ) took place on 23 June 1795 off the island of Groix in the Bay of Biscay during the War of the First Coalition. It was fought between elements of the British Channel Fleet and the French Ponant Fleet, Atlantic Fleet, whi ...

, three ships were overrun and attacked, suffering heavy damage and casualties before surrendering.Clowes, p. 263 Others were damaged, but at 08:37, with most of his fleet still unengaged and the French scattered along the coast, Bridport suddenly called off the action and instructed his ships to gather their prizes and retire, a decision that was greatly criticised by contemporary officers and later historians.Woodman, p. 61

In France, Villaret's failure to press his attack against Cornwallis's squadron was blamed on a number of factors, including accusations that the captains of the French ships leading the attack had deliberately disobeyed orders to engage the British and that they were unable to effectively manoeuvre their vessels.Clowes, p. 259 It was also insisted by several of the French officers present that the sails on the northwest horizon really had been Bridport's fleet and that this was the only factor that had induced them to disengage.James, p. 242 Villaret placed much of the blame on Captain Jean Magnac of ''Zélé'', whom he accused of withdrawing from the action prematurely and disobeying orders. Magnac was later court-martial

A court-martial (plural ''courts-martial'' or ''courts martial'', as "martial" is a postpositive adjective) is a military court or a trial conducted in such a court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of members of the arme ...

ed and dismissed from the French Navy.Rouvier, p. 208 In Britain, the battle was celebrated as one of the most notable actions of the early years of the conflict, an attitude encouraged by the modesty of Cornwallis's dispatch to the Admiralty, which when describing how he had faced down an entire French fleet at the climax of the action wrote only that the French had "made a Shew of a more ferious attack upon the Mars . . . and obliged me to bear up for her Support ." He did however subsequently note of his men that

Cornwallis was given the thanks of both Houses of Parliament

The Palace of Westminster is the meeting place of the Parliament of the United Kingdom and is located in London, England. It is commonly called the Houses of Parliament after the House of Commons and the House of Lords, the two legislative ch ...

, but fell out of favour with the Admiralty in October 1795 in a dispute about naval discipline and was court-martial

A court-martial (plural ''courts-martial'' or ''courts martial'', as "martial" is a postpositive adjective) is a military court or a trial conducted in such a court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of members of the arme ...

ed and censured in 1796 for abandoning a convoy to the West Indies

The West Indies is an island subregion of the Americas, surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea, which comprises 13 independent island country, island countries and 19 dependent territory, dependencies in thr ...

due to damage to ''Royal Sovereign'' and ill-health.Cornwallis, Sir William''

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

The ''Dictionary of National Biography'' (''DNB'') is a standard work of reference on notable figures from History of the British Isles, British history, published since 1885. The updated ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (''ODNB'') ...

'', Andrew Lambert

Andrew David Lambert (born 31 December 1956) is a British naval historian, who since 2001 has been the Laughton Professor of Naval History in the Department of War Studies, King's College London.

Academic career

After completing his doctoral ...

, (subscription required), Retrieved 15 April 2012 He entered retirement that year, but in 1801 he was given command of the Channel Fleet by Earl St Vincent

Viscount St Vincent, of Meaford in the County of Stafford, is a title in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. It was created on 27 April 1801 for the noted naval commander John Jervis, Earl of St Vincent, with remainder to his nephews William H ...

and for the next five years led the blockade of the French Atlantic Fleet, most notably during the Trafalgar campaign

The Trafalgar campaign was a long and complicated series of fleet manoeuvres carried out by the combined French Navy, French and Spanish Navy, Spanish fleets; and the opposing moves of the Royal Navy during much of 1805. These were the culmina ...

of 1805 when he sent reinforcements to the fleet under Vice-Admiral Lord Nelson

Horatio Nelson, 1st Viscount Nelson, 1st Duke of Bronte ( – 21 October 1805) was a Royal Navy officer whose leadership, grasp of strategy and unconventional tactics brought about a number of decisive British naval victories during the French ...

at a critical juncture. British historians have highly praised the conduct of Cornwallis and his men at the unequal battle: In 1825 Brenton wrote that Cornwallis's Retreat is "justly considered one of the finest displays of united courage and coolness to be found in our naval history." while in 1827 William James

William James (January 11, 1842 – August 26, 1910) was an American philosopher and psychologist. The first educator to offer a psychology course in the United States, he is considered to be one of the leading thinkers of the late 19th c ...

wrote of the "masterly retreat of Vice-admiral Cornwallis" in which "the spirit manifested by the different ships' companies of his little squadron, while pressed upon by a force from its threefold superiority so capable of crushing them, was just as ought always to animate British seamen when in the presence of an enemy." Modern historian Robert Gardiner echoed this sentiment, noting in 1998 that "'Cornwallis's Retreat' became as famous as many of the Royal Navy's real victories."Gardiner, p. 46

Notes

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * {{cite book , last = Woodman , first = Richard , author-link = Richard Woodman , year = 2001 , title = The Sea Warriors , publisher = Constable Publishers , isbn = 1-84119-183-3 Naval battles of the French Revolutionary Wars involving France Naval battles of the French Revolutionary Wars involving Great Britain Conflicts in 1795