Fillmore Administration on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The presidency of Millard Fillmore began on July 9, 1850, when

Before and during Taylor's presidency, a crisis had developed over the land acquired after the Mexican–American War in the

Before and during Taylor's presidency, a crisis had developed over the land acquired after the Mexican–American War in the

On January 29, 1850, Senator Henry Clay introduced a plan which combined the major subjects under discussion. His legislative package included the admission of California as a free state, the

On January 29, 1850, Senator Henry Clay introduced a plan which combined the major subjects under discussion. His legislative package included the admission of California as a free state, the

The debate over slavery in the territories continued despite Taylor's death. Though Fillmore favored the broad outlines of Clay's compromise, he did not believe that it could pass via a single bill. With Fillmore's support, Senator

The debate over slavery in the territories continued despite Taylor's death. Though Fillmore favored the broad outlines of Clay's compromise, he did not believe that it could pass via a single bill. With Fillmore's support, Senator

Fillmore hoped that slavery would one day cease to exist in the United States, but he believed that it was his duty to zealously enforce the Fugitive Slave Act. After 1850, Fillmore's enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Act became the central issue of his administration. The Fugitive Slave Act created the first national system of law enforcement by appointing federal commissioner in every county to hear fugitive slave cases and enforce the fugitive slave law. As there were few federal courts operating throughout the country, the appointment of commissioners allowed for the enforcement of a federal law without relying on state courts, many of which were unsympathetic to slave masters or unwilling to even take on fugitive slave cases. The law also penalized commissioners and

Fillmore hoped that slavery would one day cease to exist in the United States, but he believed that it was his duty to zealously enforce the Fugitive Slave Act. After 1850, Fillmore's enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Act became the central issue of his administration. The Fugitive Slave Act created the first national system of law enforcement by appointing federal commissioner in every county to hear fugitive slave cases and enforce the fugitive slave law. As there were few federal courts operating throughout the country, the appointment of commissioners allowed for the enforcement of a federal law without relying on state courts, many of which were unsympathetic to slave masters or unwilling to even take on fugitive slave cases. The law also penalized commissioners and

Fillmore oversaw two highly competent Secretaries of State, Webster, and after the New Englander's 1852 death, Edward Everett, looking over their shoulders and making all major decisions. The president was particularly active in Asia and the Pacific, especially with regard to Japan, which at this time still Sakoku, prohibited nearly all foreign contact. American businessmen wanted Japan "opened up" for trade, and businessmen and the navy alike wanted the ability to visit Japan to stock up on provisions such as coal. Many Americans were also concerned by the fate of shipwrecked American sailors, who were treated as criminals in Japan. Fillmore began planning an expedition to Japan in 1850, but the expedition, led by Commodore (USN), Commodore Matthew Perry (naval officer), Matthew C. Perry, did not leave until November 1852. Though the

Fillmore oversaw two highly competent Secretaries of State, Webster, and after the New Englander's 1852 death, Edward Everett, looking over their shoulders and making all major decisions. The president was particularly active in Asia and the Pacific, especially with regard to Japan, which at this time still Sakoku, prohibited nearly all foreign contact. American businessmen wanted Japan "opened up" for trade, and businessmen and the navy alike wanted the ability to visit Japan to stock up on provisions such as coal. Many Americans were also concerned by the fate of shipwrecked American sailors, who were treated as criminals in Japan. Fillmore began planning an expedition to Japan in 1850, but the expedition, led by Commodore (USN), Commodore Matthew Perry (naval officer), Matthew C. Perry, did not leave until November 1852. Though the

The 1852 Whig National Convention convened on June 16. Two days later, at the urging of Southern delegates, the Whig National Convention passed a party platform endorsing the Compromise as a final settlement of the slavery question. On the convention's first presidential ballot, Fillmore received 133 of the necessary 147 votes, while Scott won 131 and Webster won 29. After the 46th ballot still failed to produce a presidential nominee, the delegates voted to adjourn until the following Monday. Fillmore supporters offered a deal to the delegates backing Webster: if Webster could win 40 votes on one of the next two ballots, then the Fillmore delegates would switch to Webster. If not, then the Webster delegates would back Fillmore. When informed of the proposed arrangement, Fillmore quickly agreed, but Webster refused to consent to the deal until Monday morning. Scott's supporters were also active over the weekend, and they won the commitment of some delegates who preferred Scott as their second choice. On the 48th ballot, Webster delegates began to defect to Scott, and the general gained the nomination on the 53rd ballot. Webster was far more unhappy at the outcome than was Fillmore, and Fillmore rejected Webster's offer to resign as Secretary of State. Many Southern Whigs, including Alexander H. Stephens and Robert Toombs, refused to support Scott.

Scott proved to be a poor candidate who lacked popular appeal, and he suffered the worst defeat in Whig history. Whigs also lost several congressional and state elections. Scott won just four states and 44 percent of the popular vote, while Pierce won just under 51 percent of the popular vote and a large majority of the Electoral College (United States), electoral vote. The party platform's endorsement of the Compromise of 1850 had destroyed Scott's hope of winning the support of the leaders of the Free Soil Party, and the party nominated John P. Hale for president. Hale's candidacy damaged the Whig ticket in the North, while distrust and apathy led many Southern Whigs to vote for Pierce or to sit out the election. The final months of Fillmore's term were uneventful, and Fillmore left office on March 4, 1853.

The 1852 Whig National Convention convened on June 16. Two days later, at the urging of Southern delegates, the Whig National Convention passed a party platform endorsing the Compromise as a final settlement of the slavery question. On the convention's first presidential ballot, Fillmore received 133 of the necessary 147 votes, while Scott won 131 and Webster won 29. After the 46th ballot still failed to produce a presidential nominee, the delegates voted to adjourn until the following Monday. Fillmore supporters offered a deal to the delegates backing Webster: if Webster could win 40 votes on one of the next two ballots, then the Fillmore delegates would switch to Webster. If not, then the Webster delegates would back Fillmore. When informed of the proposed arrangement, Fillmore quickly agreed, but Webster refused to consent to the deal until Monday morning. Scott's supporters were also active over the weekend, and they won the commitment of some delegates who preferred Scott as their second choice. On the 48th ballot, Webster delegates began to defect to Scott, and the general gained the nomination on the 53rd ballot. Webster was far more unhappy at the outcome than was Fillmore, and Fillmore rejected Webster's offer to resign as Secretary of State. Many Southern Whigs, including Alexander H. Stephens and Robert Toombs, refused to support Scott.

Scott proved to be a poor candidate who lacked popular appeal, and he suffered the worst defeat in Whig history. Whigs also lost several congressional and state elections. Scott won just four states and 44 percent of the popular vote, while Pierce won just under 51 percent of the popular vote and a large majority of the Electoral College (United States), electoral vote. The party platform's endorsement of the Compromise of 1850 had destroyed Scott's hope of winning the support of the leaders of the Free Soil Party, and the party nominated John P. Hale for president. Hale's candidacy damaged the Whig ticket in the North, while distrust and apathy led many Southern Whigs to vote for Pierce or to sit out the election. The final months of Fillmore's term were uneventful, and Fillmore left office on March 4, 1853.

According to his biographer, Robert Scarry: "No president of the United States ... has suffered as much ridicule as Millard Fillmore". He ascribed much of the abuse to a tendency to denigrate the presidents who served in the years just prior to the Civil War as lacking in leadership. For example, president Harry S. Truman "characterized Fillmore as a weak, trivial thumb-twaddler who would do nothing to offend anyone", responsible in part for the Civil War. Professional historians are no more kind. Paul Finkelman commented, "on the central issues of the age his vision was myopic and his legacy is worse ... in the end, Fillmore was always on the wrong side of the great moral and political issues". Finkelman argues that the central accomplishment of Fillmore's tenure, the Compromise of 1850, should instead be called the "Appeasement of 1850" due to its abandoning of the

According to his biographer, Robert Scarry: "No president of the United States ... has suffered as much ridicule as Millard Fillmore". He ascribed much of the abuse to a tendency to denigrate the presidents who served in the years just prior to the Civil War as lacking in leadership. For example, president Harry S. Truman "characterized Fillmore as a weak, trivial thumb-twaddler who would do nothing to offend anyone", responsible in part for the Civil War. Professional historians are no more kind. Paul Finkelman commented, "on the central issues of the age his vision was myopic and his legacy is worse ... in the end, Fillmore was always on the wrong side of the great moral and political issues". Finkelman argues that the central accomplishment of Fillmore's tenure, the Compromise of 1850, should instead be called the "Appeasement of 1850" due to its abandoning of the

Online

* Holman Hamilton. ''Prologue to Conflict: The Crisis and Compromise of 1850'' (1964

Online free to borrow

* Nevins, Allan. ''Ordeal of the Union, vol. 1: Fruits of Manifest Destiny, 1847–1852'' (1947), covers politics in depth

Online free to borrow

* pp. 309–344. *

from the Library of Congress

Biography by Appleton's and Stanley L. Klos

at the New York State Library * * *

Millard Fillmore

A bibliography by The Buffalo History Museum

Millard Fillmore at Encyclopedia American: The American Presidency

Essays on Fillmore and each member of his cabinet and First Lady

"Life Portrait of Millard Fillmore"

from C-SPAN's ''American Presidents: Life Portraits'', June 11, 1999 {{Authority control Presidency of Millard Fillmore, 1850s in the United States Presidencies of the United States, Fillmore, Millard 1850 establishments in the United States 1853 disestablishments in the United States

Millard Fillmore

Millard Fillmore (January 7, 1800March 8, 1874) was the 13th president of the United States, serving from 1850 to 1853; he was the last to be a member of the Whig Party while in the White House. A former member of the U.S. House of Represen ...

became President of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the Federal government of the United States#Executive branch, executive branch of the Federal gove ...

upon the death of Zachary Taylor

Zachary Taylor (November 24, 1784 – July 9, 1850) was an American military leader who served as the 12th president of the United States from 1849 until his death in 1850. Taylor was a career officer in the United States Army, rising to th ...

, and ended on March 4, 1853. Fillmore had been Vice President of the United States

The vice president of the United States (VPOTUS) is the second-highest officer in the executive branch of the U.S. federal government, after the president of the United States, and ranks first in the presidential line of succession. The vice p ...

for when he became the 13th

In music or music theory, a thirteenth is the Musical note, note thirteen scale degrees from the root (chord), root of a chord (music), chord and also the interval (music), interval between the root and the thirteenth. The interval can be ...

United States president. Fillmore was the second president to succeed to the office without being elected to it, after John Tyler

John Tyler (March 29, 1790 – January 18, 1862) was the tenth president of the United States, serving from 1841 to 1845, after briefly holding office as the tenth vice president of the United States, vice president in 1841. He was elected v ...

. He was the last Whig

Whig or Whigs may refer to:

Parties and factions

In the British Isles

* Whigs (British political party), one of two political parties in England, Great Britain, Ireland, and later the United Kingdom, from the 17th to 19th centuries

** Whiggism ...

president. His presidency ended after losing the Whig nomination at the 1852 Whig National Convention

The 1852 Whig National Convention was a presidential nominating convention held from June 17 to June 20, in Baltimore, Maryland. It nominated the Whig Party's candidates for president and vice president in the 1852 election. The convention s ...

. Fillmore was succeeded by Democrat Franklin Pierce.

Upon taking office, Fillmore dismissed Taylor's cabinet and pursued a new policy with regards to the territory acquired in the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Second Federal Republic of Mexico, Mexico f ...

. He supported the efforts of Senators Henry Clay

Henry Clay Sr. (April 12, 1777June 29, 1852) was an American attorney and statesman who represented Kentucky in both the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives. He was the seventh House speaker as well as the ninth secretary of state, ...

and Stephen A. Douglas

Stephen Arnold Douglas (April 23, 1813 – June 3, 1861) was an American politician and lawyer from Illinois. A senator, he was one of two nominees of the badly split Democratic Party for president in the 1860 presidential election, which was ...

, who crafted and passed the Compromise of 1850

The Compromise of 1850 was a package of five separate bills passed by the United States Congress in September 1850 that defused a political confrontation between slave and free states on the status of territories acquired in the Mexican– ...

. The Compromise of 1850 temporarily settled the status of slavery in the lands acquired as result of the Mexican–American War, and led to a brief truce in the escalating political battle between slave and free states

In the United States before 1865, a slave state was a state in which slavery and the internal or domestic slave trade were legal, while a free state was one in which they were not. Between 1812 and 1850, it was considered by the slave states ...

. A controversial part of the Compromise was the Fugitive Slave Act

A fugitive (or runaway) is a person who is fleeing from custody, whether it be from jail, a government arrest, government or non-government questioning, vigilante violence, or outraged private individuals. A fugitive from justice, also know ...

, which expedited the return of escaped slaves to those who claimed ownership. Fillmore felt himself duty-bound to enforce it, but his support of the policy damaged his popularity and split both the Whig Party and the nation. In foreign policy, Fillmore launched the Perry Expedition

The Perry Expedition ( ja, 黒船来航, , "Arrival of the Black Ships") was a diplomatic and military expedition during 1853–1854 to the Tokugawa Shogunate involving two separate voyages by warships of the United States Navy. The goals of th ...

to open trade in Japan, moved to block the French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with France ...

annexation of Hawaii

Hawaii ( ; haw, Hawaii or ) is a state in the Western United States, located in the Pacific Ocean about from the U.S. mainland. It is the only U.S. state outside North America, the only state that is an archipelago, and the only ...

, and reduced tensions with Spain in the aftermath of Narciso López

Narciso López (November 2, 1797, Caracas – September 1, 1851, Havana) was a Venezuelan-born adventurer and Spanish Army general who is best known for his expeditions aimed at liberating Cuba from Spanish rule in the 1850s. His troops carried ...

's filibuster

A filibuster is a political procedure in which one or more members of a legislative body prolong debate on proposed legislation so as to delay or entirely prevent decision. It is sometimes referred to as "talking a bill to death" or "talking out ...

expeditions to Cuba.

Fillmore somewhat reluctantly sought his party's nomination for a full term, but the split between supporters of Fillmore and Secretary of State Daniel Webster

Daniel Webster (January 18, 1782 – October 24, 1852) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented New Hampshire and Massachusetts in the U.S. Congress and served as the U.S. Secretary of State under Presidents William Henry Harri ...

led to the nomination of General Winfield Scott

Winfield Scott (June 13, 1786May 29, 1866) was an American military commander and political candidate. He served as a general in the United States Army from 1814 to 1861, taking part in the War of 1812, the Mexican–American War, the early s ...

at the 1852 Whig National Convention

The 1852 Whig National Convention was a presidential nominating convention held from June 17 to June 20, in Baltimore, Maryland. It nominated the Whig Party's candidates for president and vice president in the 1852 election. The convention s ...

. Pierce defeated Scott by a wide margin in the general election

A general election is a political voting election where generally all or most members of a given political body are chosen. These are usually held for a nation, state, or territory's primary legislative body, and are different from by-elections ( ...

. Though some analysts praise various aspects of his presidency, Fillmore is generally ranked as an inadequate president in polls of historians and political scientists.

Accession

The1848 Whig National Convention

The 1848 Whig National Convention was a presidential nominating convention held from June 7 to 9 in Philadelphia. It nominated the Whig Party's candidates for president and vice president in the 1848 election. The convention selected General Za ...

selected Zachary Taylor

Zachary Taylor (November 24, 1784 – July 9, 1850) was an American military leader who served as the 12th president of the United States from 1849 until his death in 1850. Taylor was a career officer in the United States Army, rising to th ...

, a top American general during the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Second Federal Republic of Mexico, Mexico f ...

, as the Whig

Whig or Whigs may refer to:

Parties and factions

In the British Isles

* Whigs (British political party), one of two political parties in England, Great Britain, Ireland, and later the United Kingdom, from the 17th to 19th centuries

** Whiggism ...

presidential nominee. For Taylor's running mate, John A. Collier

John Allen Collier (November 13, 1787 – March 24, 1873) was an American lawyer and politician from New York.

Early life

John Allen Collier was born on November 13, 1787, in Litchfield, Connecticut. He attended Yale College in 1803, then st ...

convinced his fellow Whigs to nominate Fillmore, a loyal supporter of defeated presidential candidate Henry Clay

Henry Clay Sr. (April 12, 1777June 29, 1852) was an American attorney and statesman who represented Kentucky in both the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives. He was the seventh House speaker as well as the ninth secretary of state, ...

. During the 1848 presidential election, Fillmore campaigned for the Whig ticket, and he helped put an end to a brief anti-Taylor movement among Northern Whigs that had emerged after Taylor accepted the nomination of a small, breakaway group of pro-slavery Democrats. With the Democrats divided by the Free Soil

The Free Soil Party was a short-lived coalition political party in the United States active from 1848 to 1854, when it merged into the Republican Party. The party was largely focused on the single issue of opposing the expansion of slavery into ...

candidacy of former President Martin Van Buren

Martin Van Buren ( ; nl, Maarten van Buren; ; December 5, 1782 – July 24, 1862) was an American lawyer and statesman who served as the eighth president of the United States from 1837 to 1841. A primary founder of the Democratic Party, he ...

, the Whigs won the 1848 presidential election.

Despite the Whig presidential victory, Democrats maintained control of both the House of Representatives

House of Representatives is the name of legislative bodies in many countries and sub-national entitles. In many countries, the House of Representatives is the lower house of a bicameral legislature, with the corresponding upper house often c ...

and the Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the e ...

, preventing the reversal of outgoing President James K. Polk

James Knox Polk (November 2, 1795 – June 15, 1849) was the 11th president of the United States, serving from 1845 to 1849. He previously was the 13th speaker of the House of Representatives (1835–1839) and ninth governor of Tennessee (18 ...

's policies on the tariff

A tariff is a tax imposed by the government of a country or by a supranational union on imports or exports of goods. Besides being a source of revenue for the government, import duties can also be a form of regulation of foreign trade and p ...

and other issues. Taylor's presidency instead centered the status of slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

in the region ceded by Mexico

Mexico ( Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a country in the southern portion of North America. It is bordered to the north by the United States; to the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; to the southeast by Guate ...

following the Mexican–American War. After taking office, Vice President Fillmore was quickly sidelined by the efforts of editor Thurlow Weed

Edward Thurlow Weed (November 15, 1797 – November 22, 1882) was a printer, New York newspaper publisher, and Whig and Republican politician. He was the principal political advisor to prominent New York politician William H. Seward and was in ...

, who viewed Fillmore as a rival to Weed's close political ally, William H. Seward

William Henry Seward (May 16, 1801 – October 10, 1872) was an American politician who served as United States Secretary of State from 1861 to 1869, and earlier served as governor of New York and as a United States Senator. A determined oppo ...

. Fillmore was unhappy during his vice presidency, partly because his wife, Abigail Fillmore

Abigail Fillmore (née Powers; March 13, 1798 – March 30, 1853), wife of President Millard Fillmore, was the First Lady of the United States from 1850 to 1853. She began work as a schoolteacher at the age of 16, where she took on Millard Fillmor ...

, spent much of her time at their home in New York.

Fillmore received the formal notification of Zachary Taylor's death, signed by the cabinet, on the evening of July 9, 1850 in his residence at the Willard Hotel

The Willard InterContinental Washington, commonly known as the Willard Hotel, is a historic luxury Beaux-Arts hotel located at 1401 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Downtown Washington, D.C. It is currently a member oHistoric Hotels of America the offi ...

. Fillmore had spent the previous night in a vigil with the cabinet outside of Taylor's White House bedroom. After acknowledging the letter, Fillmore went to the House of Representatives Chamber in the U.S. Capitol

The United States Capitol, often called The Capitol or the Capitol Building, is the seat of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, which is formally known as the United States Congress. It is located on Capitol Hill at ...

the following day, where he took the presidential oath of office. William Cranch

William Cranch (July 17, 1769 – September 1, 1855) was a United States circuit judge and chief judge of the United States Circuit Court of the District of Columbia. A staunch Federalist and nephew of President John Adams, Cranch moved his leg ...

, chief judge of the U.S. Circuit Court, administered the oath to Fillmore. In contrast to John Tyler

John Tyler (March 29, 1790 – January 18, 1862) was the tenth president of the United States, serving from 1841 to 1845, after briefly holding office as the tenth vice president of the United States, vice president in 1841. He was elected v ...

, whose legitimacy as president had been questioned by many after his accession to the presidency in 1841, Fillmore was widely accepted as the president by members of Congress and the public.

Taylor's widow, Margaret Taylor

Margaret "Peggy" Mackall Taylor ( ''née'' Smith; September 21, 1788 – August 14, 1852) was the first lady of the United States from 1849 to 1850 as the wife of President Zachary Taylor. She married Zachary in 1810 and lived as an army wif ...

, left Washington soon after her husband's death, and Fillmore's family took up residence in the White House shortly thereafter. Because Fillmore's wife, Abigail, was often in poor health, his daughter, Mary Abigail Fillmore

Mary Abigail "Abbie" Fillmore (March 27, 1832, Buffalo, New York – July 26, 1854, East Aurora, New York) was the daughter of President Millard Fillmore and Abigail Powers. During her father's presidency from 1850 to 1853 she often served ...

, frequently served as the White House hostess.

Administration

Taylor's cabinet appointees submitted their resignation on July 10, and Fillmore accepted the resignations the following day. Fillmore is the only president who succeeded by death or resignation not to retain, at least initially, his predecessor's cabinet. The biggest challenge facing Taylor had been the issue of slavery in the territories, and this issue immediately confronted the Fillmore administration as well. Taylor had opposed a plan, formulated by Henry Clay, which was designed to appeal to both anti-slavery northerners and pro-slavery southerners, but which received the most support from Southerners. During his vice presidency, Fillmore had indicated that he might vote to support the compromise, but he had not publicly committed himself on the issue when he assumed the presidency. Fillmore hoped to use the process of selecting the cabinet to re-unify the Whig Party, and he sought to balance the cabinet among North and South, pro-compromise and anti-compromise, and pro-Taylor and anti-Taylor. Fillmore offered the position of Secretary of State toRobert Charles Winthrop

Robert Charles Winthrop (May 12, 1809 – November 16, 1894) was an American lawyer and philanthropist, who served as the speaker of the United States House of Representatives. He was a descendant of John Winthrop.

Early life

Robert Charles ...

, an anti-compromise Massachusetts Whig who was widely popular among Whigs in the House of Representatives, but Winthrop declined the post. Fillmore instead chose Daniel Webster

Daniel Webster (January 18, 1782 – October 24, 1852) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented New Hampshire and Massachusetts in the U.S. Congress and served as the U.S. Secretary of State under Presidents William Henry Harri ...

, who had previously served as Secretary of State under William Henry Harrison

William Henry Harrison (February 9, 1773April 4, 1841) was an American military officer and politician who served as the ninth president of the United States. Harrison died just 31 days after his inauguration in 1841, and had the shortest pres ...

and John Tyler. Webster had outraged his Massachusetts constituents by supporting the compromise, and he was unlikely to win election another term in the Senate in 1851. Webster became Fillmore's most important adviser. Two other prominent Whig Senators, Thomas Corwin

Thomas Corwin (July 29, 1794 – December 18, 1865), also known as Tom Corwin, The Wagon Boy, and Black Tom was a politician from the state of Ohio. He represented Ohio in both houses of Congress and served as the 15th governor of Ohio and the 2 ...

of Ohio and John J. Crittenden

John Jordan Crittenden (September 10, 1787 July 26, 1863) was an American statesman and politician from the U.S. state of Kentucky. He represented the state in the U.S. House of Representatives and the U.S. Senate and twice served as United ...

of Kentucky, also joined Fillmore's cabinet. Fillmore appointed his old law partner, Nathan Hall, as Postmaster General

A Postmaster General, in Anglosphere countries, is the chief executive officer of the postal service of that country, a ministerial office responsible for overseeing all other postmasters. The practice of having a government official responsibl ...

, a cabinet position that controlled many patronage appointments. Charles Magill Conrad

Charles Magill Conrad (December 24, 1804 – February 11, 1878) was a Louisiana politician who served in the United States Senate, United States House of Representatives, and Confederate Congress. He was Secretary of War under President Millar ...

of Louisiana became the Secretary of War, William Alexander Graham

William Alexander Graham (September 5, 1804August 11, 1875) was a United States senator from North Carolina from 1840 to 1843, a senator later in the Confederate States Senate from 1864 to 1865, the 30th governor of North Carolina from 1845 t ...

of North Carolina became Secretary of the Navy, and Alexander Hugh Holmes Stuart

Alexander Hugh Holmes Stuart (April 2, 1807 – February 13, 1891) was a prominent Virginia lawyer and American political figure associated with several political parties. Stuart served in both houses of the Virginia General Assembly (1836-1 ...

of Virginia became Secretary of the Interior. Though Fillmore's cabinet appointments were warmly received by both Northern and Southern Whigs, party unity was shattered soon after Fillmore's accession due to the fight over Clay's compromise.

Judicial appointments

Fillmore appointed oneSupreme Court

A supreme court is the highest court within the hierarchy of courts in most legal jurisdictions. Other descriptions for such courts include court of last resort, apex court, and high (or final) court of appeal. Broadly speaking, the decisions of ...

justice, though two Supreme Court vacancies arose during his presidency. The first vacancy arose due to the death of Associate Justice

Associate justice or associate judge (or simply associate) is a judicial panel member who is not the chief justice in some jurisdictions. The title "Associate Justice" is used for members of the Supreme Court of the United States and some sta ...

Levi Woodbury

Levi Woodbury (December 22, 1789September 4, 1851) was an American attorney, jurist, and Democratic politician from New Hampshire. During a four-decade career in public office, Woodbury served as Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the Un ...

in 1851. Determined to nominate a Whig from New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York to the west and by the Canadian province ...

, Fillmore settled on Benjamin Robbins Curtis

Benjamin Robbins Curtis (November 4, 1809 – September 15, 1874) was an American lawyer and judge. He served as an associate justice of the United States Supreme Court from 1851 to 1857. Curtis was the first and only Whig justice of the ...

. The 41-year-old Curtis had earned notoriety as a leading practitioner of commercial law, and he won the full backing of Secretary of State Webster. Despite some opposition from anti-slavery senators, Curtis ultimately won Senate approval. After the death of Associate Justice John McKinley

John McKinley (May 1, 1780 – July 19, 1852) was a United States Senator from the state of Alabama and an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States.

Early life

McKinley was born in Culpeper County, Virginia, on May 1, 17 ...

in mid-1852, Fillmore successively nominated Edward A. Bradford

Edward Anthony Bradford (September 17, 1813 – November 22, 1872) was a lawyer and unsuccessful nominee to the United States Supreme Court.

Biography

Born in Plainfield, Connecticut, Bradford graduated from Yale University (1833) and Harvard Law ...

, George Edmund Badger

George Edmund Badger (April 17, 1795May 11, 1866) was a slave owner and Whig U.S. senator from the state of North Carolina.

Early life

Badger was born on April 17, 1795, in New Bern, North Carolina. He attended Yale College (where he was a ...

, and William C. Micou

William Chatfield Micou (January 11, 1807 - April 16, 1854) was an American lawyer who was active in Augusta, Georgia, and New Orleans, Louisiana. He was also an unsuccessful nominee to the United States Supreme Court at the end of the Millard Fi ...

. By refusing to act on any of the nominations, Senate Democrats ensured that the vacancy would be filled by Franklin Pierce after Fillmore left office. Curtis would serve on the Supreme Court until 1857, when he resigned in protest of the holding in ''Dred Scott v. Sandford

''Dred Scott v. Sandford'', 60 U.S. (19 How.) 393 (1857), was a landmark decision of the United States Supreme Court that held the U.S. Constitution did not extend American citizenship to people of black African descent, enslaved or free; t ...

''. Fillmore also made four appointments to United States district court

The United States district courts are the trial courts of the U.S. federal judiciary. There is one district court for each federal judicial district, which each cover one U.S. state or, in some cases, a portion of a state. Each district c ...

s, including that of his Postmaster General, Nathan Hall, to the federal district court in Buffalo.

Domestic affairs

Compromise of 1850

Background

Before and during Taylor's presidency, a crisis had developed over the land acquired after the Mexican–American War in the

Before and during Taylor's presidency, a crisis had developed over the land acquired after the Mexican–American War in the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ( es, Tratado de Guadalupe Hidalgo), officially the Treaty of Peace, Friendship, Limits, and Settlement between the United States of America and the United Mexican States, is the peace treaty that was signed on 2 ...

. The key issue was the status of slavery in the territories

A territory is an area of land, sea, or space, particularly belonging or connected to a country, person, or animal.

In international politics, a territory is usually either the total area from which a state may extract power resources or a ...

, which, for many leaders, represented a debate over not just slavery but also morality, property rights, and personal honor. Southern extremists like John C. Calhoun

John Caldwell Calhoun (; March 18, 1782March 31, 1850) was an American statesman and political theorist from South Carolina who held many important positions including being the seventh vice president of the United States from 1825 to 1832. He ...

viewed any limit on slavery as an attack on the Southern way of life, while many Northerners opposed any further expansion of slavery. Further complicating the issue was the fact that much of the newly acquired Western lands seemed unsuitable to slavery due to climate and geography. In 1820, Congress had agreed to the Missouri Compromise

The Missouri Compromise was a federal legislation of the United States that balanced desires of northern states to prevent expansion of slavery in the country with those of southern states to expand it. It admitted Missouri as a slave state an ...

, which had banned slavery in all lands of the Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase (french: Vente de la Louisiane, translation=Sale of Louisiana) was the acquisition of the territory of Louisiana by the United States from the French First Republic in 1803. In return for fifteen million dollars, or app ...

north of the 36° 30' parallel, and many Southerners sought to extend this line to the Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the contine ...

. During the Mexican–American War, a Northern member of Congress had put forth the Wilmot Proviso

The Wilmot Proviso was an unsuccessful 1846 proposal in the United States Congress to ban slavery in territory acquired from Mexico in the Mexican–American War. The conflict over the Wilmot Proviso was one of the major events leading to the ...

, a legislative proposal that would have banned slavery in all territories acquired in the Mexican–American War. Though not adopted by Congress, the debate over the Wilmot Proviso had contributed to an increasingly tense national debate regarding slavery.

The territorial issues centered on the territories of California

California is a state in the Western United States, located along the Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the most populous U.S. state and the 3rd largest by area. It is also the ...

and New Mexico

)

, population_demonym = New Mexican ( es, Neomexicano, Neomejicano, Nuevo Mexicano)

, seat = Santa Fe, New Mexico, Santa Fe

, LargestCity = Albuquerque, New Mexico, Albuquerque

, LargestMetro = Albuquerque metropolitan area, Tiguex

, Offi ...

, as well the state of Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish language, Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2 ...

, which had been annexed

Annexation (Latin ''ad'', to, and ''nexus'', joining), in international law, is the forcible acquisition of one state's territory by another state, usually following military occupation of the territory. It is generally held to be an illegal act ...

in 1845. Because California lacked an organized territorial government, the federal government faced difficulties in providing adequate governance in the midst of the California Gold Rush, and many sought immediate statehood for California. After the start of the gold rush, hundreds of slaves were imported into California to work the gold mines, provoking a harsh reaction from competing miners. With the approval of military governor Bennet C. Riley

Bennet C. RileyHis name is sometimes written as Bennett, but his own correspondence uses the spelling of Bennet. See United States. Congress. House. 13th Congress, 2d Session-49th Congress. House Documents, Otherwise Publ. as Executive Documents: ...

, in 1849 Californians held a constitutional convention Constitutional convention may refer to:

* Constitutional convention (political custom), an informal and uncodified procedural agreement

*Constitutional convention (political meeting), a meeting of delegates to adopt a new constitution or revise an e ...

. In anticipation of imminent statehood, the convention wrote a new constitution that would ban slavery in California. Meanwhile, Texas claimed all of the Mexican Cession east of the Rio Grande

The Rio Grande ( and ), known in Mexico as the Río Bravo del Norte or simply the Río Bravo, is one of the principal rivers (along with the Colorado River) in the southwestern United States and in northern Mexico.

The length of the Rio ...

, including parts of the former Mexican state of New Mexico

)

, population_demonym = New Mexican ( es, Neomexicano, Neomejicano, Nuevo Mexicano)

, seat = Santa Fe, New Mexico, Santa Fe

, LargestCity = Albuquerque, New Mexico, Albuquerque

, LargestMetro = Albuquerque metropolitan area, Tiguex

, Offi ...

that it had never exercised de facto control over. Texan leaders had expected to be granted control of all territory east of the Rio Grande after the Mexican-American War, but the inhabitants of New Mexico had resisted Texan control. New Mexico had long prohibited slavery, a fact that affected the debate over its territorial status, but many New Mexican leaders opposed joining Texas primarily because Texas's capital lay hundreds of miles away and because Texas and New Mexico had a history of conflict dating back to the 1841 Santa Fe Expedition

The Texan Santa Fe Expedition was a commercial and military expedition to secure the Republic of Texas's claims to parts of Northern New Mexico for Texas in 1841. The expedition was unofficially initiated by the then-President of Texas, Mirabeau B ...

. Outside of Texas, many Southern leaders supported Texas's claims to New Mexico in order to secure as much territory as possible for the expansion of slavery. President Taylor had opposed Texas's ambitions in New Mexico, and he favored quickly granting statehood to both California and New Mexico in order to avoid reigniting the debate over the Wilmot Proviso.

Congress also faced the issue of Utah

Utah ( , ) is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. Utah is a landlocked U.S. state bordered to its east by Colorado, to its northeast by Wyoming, to its north by Idaho, to its south by Arizona, and to its ...

, which like California and New Mexico, had been ceded by Mexico. Utah was inhabited largely by Mormons

Mormons are a Religious denomination, religious and cultural group related to Mormonism, the principal branch of the Latter Day Saint movement started by Joseph Smith in upstate New York during the 1820s. After Smith's death in 1844, the mov ...

, whose practice of polygamy

Crimes

Polygamy (from Late Greek (') "state of marriage to many spouses") is the practice of marrying multiple spouses. When a man is married to more than one wife at the same time, sociologists call this polygyny. When a woman is marri ...

was unpopular in the United States. Aside from the disposition of the territories, other issues had risen to prominence during the Taylor years. The Washington, D.C. slave trade angered many in the North, who viewed the presence of slavery in the capital as a blemish on the nation. Disputes around fugitive slaves had grown since 1830 in part due to improving means of transportation, as escaped slaves used roads, railroads, and ships to escape. The Fugitive Slave Act of 1793

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 was an Act of the United States Congress to give effect to the Fugitive Slave Clause of the US Constitution ( Article IV, Section 2, Clause 3), which was later superseded by the Thirteenth Amendment, and to also g ...

had granted jurisdiction to all state and federal judges over cases regarding fugitive slaves, but several Northern states, dissatisfied by the lack of due process

Due process of law is application by state of all legal rules and principles pertaining to the case so all legal rights that are owed to the person are respected. Due process balances the power of law of the land and protects the individual pe ...

in these cases, had passed personal liberty laws

In the context of slavery in the United States, the personal liberty laws were laws passed by several U.S. states in the North to counter the Fugitive Slave Acts of 1793 and 1850. Different laws did this in different ways, including allowing ju ...

that made it more difficult to return alleged fugitive slaves to the South. Another issue that would affect the compromise was Texas's debt; it had approximately $10 million in debt left over from its time as an independent nation, and that debt would become a factor in the debates over the territories.

Taylor presidency

On January 29, 1850, Senator Henry Clay introduced a plan which combined the major subjects under discussion. His legislative package included the admission of California as a free state, the

On January 29, 1850, Senator Henry Clay introduced a plan which combined the major subjects under discussion. His legislative package included the admission of California as a free state, the cession

The act of cession is the assignment of property to another entity. In international law it commonly refers to land transferred by treaty. Ballentine's Law Dictionary defines cession as "a surrender; a giving up; a relinquishment of jurisdict ...

by Texas of some of its northern and western territorial claims in return for debt relief, the establishment of New Mexico

)

, population_demonym = New Mexican ( es, Neomexicano, Neomejicano, Nuevo Mexicano)

, seat = Santa Fe, New Mexico, Santa Fe

, LargestCity = Albuquerque, New Mexico, Albuquerque

, LargestMetro = Albuquerque metropolitan area, Tiguex

, Offi ...

and Utah

Utah ( , ) is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. Utah is a landlocked U.S. state bordered to its east by Colorado, to its northeast by Wyoming, to its north by Idaho, to its south by Arizona, and to its ...

territories, a ban on the importation of slaves into the District of Columbia for sale, and a more stringent fugitive slave law. In the final months of his life, Senator Calhoun attempted to rally Southerners against the compromise, arguing that it was biased against the South because it would lead to the creation of new free states. Anti-slavery Northerners like William Seward and Salmon Chase

Salmon () is the common name for several commercially important species of euryhaline ray-finned fish from the family Salmonidae, which are native to tributaries of the North Atlantic (genus ''Salmo'') and North Pacific (genus ''Oncorhynchus' ...

also opposed the compromise. Clay's proposal did, however, win the backing of many Southern and Northern leaders, many of whom attacked opponents of the compromise as extremists. Fillmore, who presided over the Senate in his role as vice president, privately came to support Clay's position.

Though Clay had originally favored voting on each of his proposals separately, Senator Henry S. Foote

Henry Stuart Foote (February 28, 1804May 19, 1880) was a United States Senator from Mississippi and the chairman of the United States Senate Committee on Foreign Relations from 1847 to 1852. He was a Unionist Governor of Mississippi from 1852 to ...

of Mississippi convinced him to combine the proposals regarding California's admission and the disposition of Texas's borders into one bill. Clay hoped that this combination of measures would convince congressmen from both North and South to support the overall package of laws even if they objected to specific provisions. Clay's proposal attracted the support of some Northern Democrats and Southern Whigs, but it lacked the backing necessary to win passage, and debate over the bill continued. Foote and other Southern leaders attempted to condition California's statehood either on granting Texas the full extent of its boundary claims on New Mexico, or on the requirement that slavery be allowed in the disputed region if it was not awarded to Texas. Foote also sought to split California into two states, with the division at the 35th parallel north. Taylor opposed the bill, since he favored granting California statehood immediately and denied the legitimacy of Texas's claims over New Mexico. While Congress continued to debate Clay's proposals, Texas Governor Peter Hansborough Bell

Peter Hansborough Bell (May 11, 1810Various sources give multiple dates in May 1810 and May 1812 for Bell's birth. Bell's gravestone uses a May 1812 date.March 8, 1898) was an American military officer and politician who served as the third Gove ...

loudly protested the organization of New Mexico's constitutional convention, which had been proceeded with the approval of Taylor and the military government of New Mexico instigated by General Stephen W. Kearny

Stephen Watts Kearny (sometimes spelled Kearney) ( ) (August 30, 1794October 31, 1848) was one of the foremost antebellum frontier officers of the United States Army. He is remembered for his significant contributions in the Mexican–American Wa ...

during the Mexican–American War. Following the New Mexico constitutional convention, Taylor urged that Congress immediately grant statehood to both California and New Mexico, and he prepared for a clash with Texas. When Taylor died in July 1850, none of the major domestic issues facing his presidency had been settled.

Compromise

The debate over slavery in the territories continued despite Taylor's death. Though Fillmore favored the broad outlines of Clay's compromise, he did not believe that it could pass via a single bill. With Fillmore's support, Senator

The debate over slavery in the territories continued despite Taylor's death. Though Fillmore favored the broad outlines of Clay's compromise, he did not believe that it could pass via a single bill. With Fillmore's support, Senator James Pearce

James Alfred Pearce (December 14, 1805December 20, 1862) was an American politician. He was a member of the U.S. House of Representatives, representing the second district of Maryland from 1835 to 1839 and 1841 to 1843. He later served as a ...

of Maryland helped defeat Clay's compromise bill by proposing to remove a provision related to the Texas-New Mexico boundary. In the ensuing debate, all provisions of the bill were removed except for the organization of Utah Territory. With the apparent collapse of the bill, Clay took a temporary leave from the Senate, and Democratic Senator Stephen A. Douglas

Stephen Arnold Douglas (April 23, 1813 – June 3, 1861) was an American politician and lawyer from Illinois. A senator, he was one of two nominees of the badly split Democratic Party for president in the 1860 presidential election, which was ...

of Illinois took the lead in advocating for a compromise based largely on Clay's proposals. Rather than passing the proposals as one bill, Douglas would seek to pass each proposal one-by-one.

Upon taking office, Fillmore reinforced federal troops in the disputed New Mexico region, and warned Texas Governor Bell to keep the peace. In an August 6, 1850 message to Congress, Fillmore disclosed a belligerent letter from Governor Bell and his own reply to Bell. In that reply, Fillmore denied Texas's claims to New Mexico, asserting that United States had promised to protect the territorial integrity of New Mexico in the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. In his message to Congress, Fillmore also urged Congress to settle the boundary dispute as quickly as possible, and indicated support for providing monetary compensation to Texas in return for the establishment of New Mexico Territory, which would include all of the land it had controlled prior to the Mexican–American War. Fillmore's forceful response helped convince Texas's U.S. Senators, Sam Houston

Samuel Houston (, ; March 2, 1793 – July 26, 1863) was an American general and statesman who played an important role in the Texas Revolution. He served as the first and third president of the Republic of Texas and was one of the first two i ...

and Thomas Jefferson Rusk

Thomas Jefferson Rusk (December 5, 1803July 29, 1857) was an early political and military leader of the Republic of Texas, serving as its first Secretary of War as well as a general at the Battle of San Jacinto. He was later a US politician and ...

, to support Stephen Douglas's compromise. With their support, a senate bill providing for a final settlement of Texas's borders won passage days after Fillmore delivered his message. Under the terms of the bill, the U.S. would assume Texas's debts, while Texas's northern border was set at the 36° 30' parallel north (the Missouri Compromise line) and much of its western border followed the 103rd meridian. The bill attracted the support of a bipartisan coalition of Whigs and Democrats from both sections, though most opposition to the bill came from the South. The Senate quickly moved onto the other major issues, passing bills that provided for the admission of California, the organization of New Mexico Territory, and the establishment of a new fugitive slave law.

The debate then moved to the House of Representatives, where Fillmore, Webster, Douglas, Congressman Linn Boyd

Linn Boyd (November 22, 1800 – December 17, 1859) (also spelled "Lynn") was a prominent US politician of the 1840s and 1850s, and served as Speaker of the United States House of Representatives from 1851 to 1855. Boyd was elected to the Hou ...

, and Speaker of the House Howell Cobb

Howell Cobb (September 7, 1815 – October 9, 1868) was an American and later Confederate political figure. A southern Democrat, Cobb was a five-term member of the United States House of Representatives and the speaker of the House from 184 ...

took the lead in convincing members to support the compromise bills that had been passed in the Senate. The Senate's proposed settlement of the Texas-New Mexico boundary faced intense opposition from many Southerners, as well as from some Northerners who believed that the Texas did not deserve monetary compensation. After a series of close votes that nearly delayed consideration of the issue, the House voted to approve a Texas bill similar to that which had been passed by the Senate. Following that vote, the House and the Senate quickly agreed on each of the major issues, including the banning of the slave trade in Washington. The president quickly signed each bill into law save for the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850

The Fugitive Slave Act or Fugitive Slave Law was passed by the United States Congress on September 18, 1850, as part of the Compromise of 1850 between Southern interests in slavery and Northern

Northern may refer to the following:

Geogra ...

; he ultimately signed that law as well after Attorney General Crittenden assured him that the law was constitutional. Though some in Texas still favored sending a military expedition into New Mexico, in November 1850 the state legislature voted to accept the compromise.

Passage of the Compromise of 1850, as it became known, caused celebration in Washington and elsewhere, with crowds shouting, "the Union is saved!" Fillmore himself described the Compromise of 1850 as a "final settlement" of sectional issues, though the future of slavery in New Mexico and Utah remained unclear. The admission of new states, or the organization of territories in the remaining unorganized portion of the Louisiana Purchase, could also potentially reopen the polarizing debate over slavery. Not all accepted the Compromise of 1850; a South Carolina newspaper wrote, "the Rubicon is passed ... and the Southern States are now vassals in this Confederacy." Many Northerners, meanwhile, were displeased by the fugitive slave law.

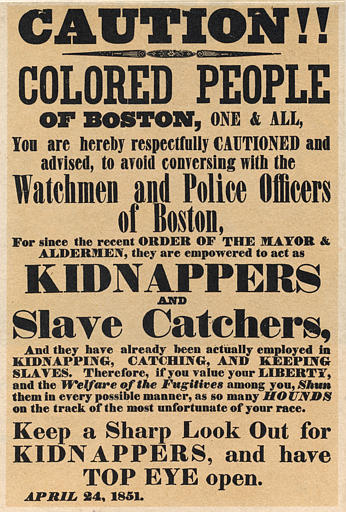

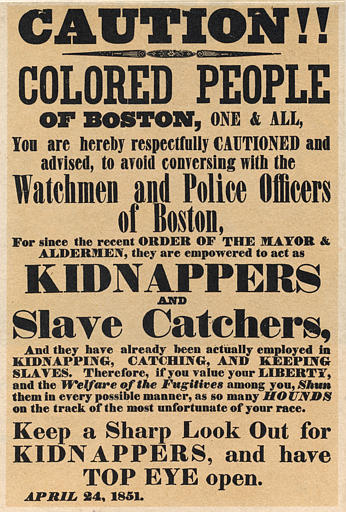

Fugitive Slave Act

Fillmore hoped that slavery would one day cease to exist in the United States, but he believed that it was his duty to zealously enforce the Fugitive Slave Act. After 1850, Fillmore's enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Act became the central issue of his administration. The Fugitive Slave Act created the first national system of law enforcement by appointing federal commissioner in every county to hear fugitive slave cases and enforce the fugitive slave law. As there were few federal courts operating throughout the country, the appointment of commissioners allowed for the enforcement of a federal law without relying on state courts, many of which were unsympathetic to slave masters or unwilling to even take on fugitive slave cases. The law also penalized commissioners and

Fillmore hoped that slavery would one day cease to exist in the United States, but he believed that it was his duty to zealously enforce the Fugitive Slave Act. After 1850, Fillmore's enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Act became the central issue of his administration. The Fugitive Slave Act created the first national system of law enforcement by appointing federal commissioner in every county to hear fugitive slave cases and enforce the fugitive slave law. As there were few federal courts operating throughout the country, the appointment of commissioners allowed for the enforcement of a federal law without relying on state courts, many of which were unsympathetic to slave masters or unwilling to even take on fugitive slave cases. The law also penalized commissioners and federal marshals

The United States Marshals Service (USMS) is a federal law enforcement agency in the United States. The USMS is a bureau within the U.S. Department of Justice, operating under the direction of the Attorney General, but serves as the enforce ...

who allowed slaves to escape from their custody, and levied fines against anyone who aided a fugitive slave or interfered with the return of slaves. Fugitive slave proceedings lacked many due process

Due process of law is application by state of all legal rules and principles pertaining to the case so all legal rights that are owed to the person are respected. Due process balances the power of law of the land and protects the individual pe ...

protections such as the right to a jury trial

A jury trial, or trial by jury, is a legal proceeding in which a jury makes a decision or findings of fact. It is distinguished from a bench trial in which a judge or panel of judges makes all decisions.

Jury trials are used in a significant ...

, and defendants were not allowed to testify at their own hearing. Many in the North felt that the Fugitive Slave Act effectively brought slavery into their home states, and while the abolitionist movement

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The British ...

remained weak, many Northerners increasingly came to detest slavery.

Though the law was highly offensive to many Northerners, Southerners complained bitterly about perceived slackness in enforcement. Many of the administration's prosecutions or attempts to return slaves ended badly for the government, as in the case of Shadrach Minkins

Shadrach Minkins (c. 1814 – December 13, 1875) was an African-American fugitive slave from Virginia who escaped in 1850 and reached Boston. He also used the pseudonyms Frederick Wilkins and Frederick Jenkins.Collison (1998), p. 1. He is known fo ...

. A major controversy erupted over the fate of Ellen and William Craft

Ellen Craft (1826–1891) and William Craft (September 25, 1824 – January 29, 1900) were American fugitives who were born and enslaved in Macon, Georgia. They escaped to the North in December 1848 by traveling by train and steamboat, arriving ...

, two escaped slaves living in Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the capital city, state capital and List of municipalities in Massachusetts, most populous city of the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financ ...

. Fillmore threatened to send federal soldiers into the city in order to compel the return of the Crafts to the South, but the Crafts' escape to England put an end to the controversy. Disputes over fugitive slaves were widely publicized North and South, inflaming passions and undermining the good feeling that had followed the Compromise. Harriet Beecher Stowe wrote the novel ''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' in response to the Fugitive Slave Act, and its publication in 1852 further raised sectional tensions.

Stirrings of disunion

The Compromise of 1850 shook up partisan alignments in South, with elections being contested by Unionist Party (United States), unionists and extremist "Fire-Eaters" rather than Whigs and Democrats. The Georgia Platform represented the moderate Southern position; it opposed secession, but also demanded Northern compromise on the slavery issue. Fire-Eater leaders like Robert Rhett and William Lowndes Yancey urged secession from the United States, and attempted to win control of the states of the Deep South in the 1851 elections. Fillmore took the threat of secession seriously, and on the advice of GeneralWinfield Scott

Winfield Scott (June 13, 1786May 29, 1866) was an American military commander and political candidate. He served as a general in the United States Army from 1814 to 1861, taking part in the War of 1812, the Mexican–American War, the early s ...

he strengthened the garrisons of federal forts in Charleston, South Carolina, Charleston and other parts of the South. In the 1851 elections, unionists won victories in Georgia, Alabama, and Mississippi. Even in South Carolina, the state most open to talk of secession, voters rejected the possibility of unilateral secession from the United States. The victory of pro-compromise Southern politicians in several elections, along with Fillmore's attempts at diligently enforcing the Fugitive Slave Clause, temporarily quieted Southern calls for secession. There was less support for outright secession in the North than in the South, but in the aftermath of the Compromise politicians such as Seward began contemplating the creation of a new major party explicitly opposed to the extension of slavery. Despite the disruptions caused by the debate over the Compromise, no major long-term partisan realignment occurred during Fillmore's presidency, and both parties remained intact for the 1852 presidential election.

Other issues

A longtime supporter of internal improvements, national infrastructure development, Fillmore called for investments in roads, railroads, and waterways. He signed bills to subsidize the Illinois Central railroad from Chicago to Mobile, Alabama, Mobile, and for Soo Locks, a canal at Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan, Sault Ste. Marie. The 1851 completion of the Erie Railroad in New York prompted Fillmore and his cabinet to ride the first train from New York City to the shores of Lake Erie, in company with many other politicians and dignitaries. Fillmore made many speeches along the way from the train's rear platform, urging acceptance of the Compromise, and afterwards went on a tour of New England with his Southern cabinet members. Although Fillmore urged Congress to authorize a transcontinental railroad, it did not do so until a decade later. Fillmore was a longtime proponent of Clay's American System (economic plan), American System, which favored a hightariff

A tariff is a tax imposed by the government of a country or by a supranational union on imports or exports of goods. Besides being a source of revenue for the government, import duties can also be a form of regulation of foreign trade and p ...

and federally-supported banks and infrastructure projects, but Congress did not consider major revisions to banking laws or the tariff during Fillmore's presidency. In a period of budget surpluses and economic prosperity, few congressmen saw the need for a higher tariff or economic interventionism.

To deescalate the Mormon issue, Fillmore appointed Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints leader Brigham Young as the first governor of Utah Territory in September 1850. In gratitude, Young named the first territorial capital "Fillmore, Utah, Fillmore" and the surrounding county "Millard County, Utah, Millard".

In August 1850, the social reformer Dorothea Dix wrote to Fillmore, urging support for her proposal in Congress for land grants to finance asylums for the impoverished mentally ill. Though her proposal did not pass, they became friends and continued to correspond well after Fillmore's presidency.

On September 21, 1850, Fillmore signed the Donation Land Claim Act of 1850 which was intended to promote homestead settlements in the Oregon Territory, but ended up displeasing Native Americans.

Noting that many miners involved in the California Gold Rush were forced to sell their gold at a discount, Fillmore asked Congress to create a United States Mint, federal mint in California, resulting in the establishment of the San Francisco Mint.

Foreign affairs

Fillmore oversaw two highly competent Secretaries of State, Webster, and after the New Englander's 1852 death, Edward Everett, looking over their shoulders and making all major decisions. The president was particularly active in Asia and the Pacific, especially with regard to Japan, which at this time still Sakoku, prohibited nearly all foreign contact. American businessmen wanted Japan "opened up" for trade, and businessmen and the navy alike wanted the ability to visit Japan to stock up on provisions such as coal. Many Americans were also concerned by the fate of shipwrecked American sailors, who were treated as criminals in Japan. Fillmore began planning an expedition to Japan in 1850, but the expedition, led by Commodore (USN), Commodore Matthew Perry (naval officer), Matthew C. Perry, did not leave until November 1852. Though the

Fillmore oversaw two highly competent Secretaries of State, Webster, and after the New Englander's 1852 death, Edward Everett, looking over their shoulders and making all major decisions. The president was particularly active in Asia and the Pacific, especially with regard to Japan, which at this time still Sakoku, prohibited nearly all foreign contact. American businessmen wanted Japan "opened up" for trade, and businessmen and the navy alike wanted the ability to visit Japan to stock up on provisions such as coal. Many Americans were also concerned by the fate of shipwrecked American sailors, who were treated as criminals in Japan. Fillmore began planning an expedition to Japan in 1850, but the expedition, led by Commodore (USN), Commodore Matthew Perry (naval officer), Matthew C. Perry, did not leave until November 1852. Though the Perry Expedition

The Perry Expedition ( ja, 黒船来航, , "Arrival of the Black Ships") was a diplomatic and military expedition during 1853–1854 to the Tokugawa Shogunate involving two separate voyages by warships of the United States Navy. The goals of th ...

did not reach Japan until after Fillmore's presidency, it served as the catalyst for the Bakumatsu, end of Japan's isolationist policy. Fillmore also supported an effort to build a railroad across Mexico's Isthmus of Tehuantepec, but disagreements among the United States, Mexico, and rival companies prevented the railroad's construction.

As part of a broader strategy of establishing U.S. influence in the Pacific, Fillmore and Webster also sought increased influence in Hawaii, which U.S. policymakers saw as an important link between the U.S. and Asia. In 1842, President John Tyler

John Tyler (March 29, 1790 – January 18, 1862) was the tenth president of the United States, serving from 1841 to 1845, after briefly holding office as the tenth vice president of the United States, vice president in 1841. He was elected v ...

had announced the "Tyler doctrine," which proclaimed that the U.S. would not accept annexation of Hawaii by a European power.#CITEREFHerring, Herring, pp. 208–209. France under Napoleon III sought to annex Hawaii, but backed down after Fillmore issued a strongly worded message warning that "the United States would not stand for any such action." The U.S. also signed a secret treaty with King Kamehameha III of Hawaii which stipulated that the U.S.

would gain sovereignty over Hawaii in case of war. Although many in Hawaii and the U.S. desired the annexation of Hawaii as U.S. state, the U.S. was unwilling to grant full citizenship to Hawaii's non-white population.

Many Southerners hoped to see Cuba, a Spain, Spanish slave-holding colony, annexed to the United States. Venezuelan adventurer Narciso López

Narciso López (November 2, 1797, Caracas – September 1, 1851, Havana) was a Venezuelan-born adventurer and Spanish Army general who is best known for his expeditions aimed at liberating Cuba from Spanish rule in the 1850s. His troops carried ...

recruited Americans for three filibuster (military), filibustering expeditions to Cuba, in the hope of overthrowing Spanish rule there. After the second attempt in 1850, López and some of his followers were indicted for breach of the Neutrality Act of 1794, Neutrality Act, but were quickly acquitted by friendly Southern juries. Fillmore ordered federal authorities to attempt to prevent López from launching a third expedition, and proclaimed that his administration would not protect anyone captured by Spain. López's third expedition ended in total failure, as the Cuban populace once again refused to rally to their would-be liberator. López and several Americans, including the nephew of Attorney General Crittenden, were executed by the Spanish, while another 160 Americans were forced to work in Spanish mines. Fillmore, Webster and the Spanish government worked out a series of face-saving measures, including the release of the American prisoners, that settled a brewing crisis between the two countries. Following the crisis, Britain and France offered a three-party treaty in which all signatories would agree to uphold Spanish control of Cuba, but Fillmore rejected the offer. Many Southerners, including Whigs, had supported the filibusters, and Fillmore's consistent opposition to the filibusters further divided his party as the 1852 election approached.

A much-publicized event of Fillmore's presidency was the arrival in late 1851 of Lajos Kossuth, the exiled leader of a failed Hungarian revolution against Austria. Kossuth wanted the U.S. to recognize Hungary's independence. Many Americans were sympathetic to the Hungarian rebels, especially recent German immigrants, who were now coming to the U.S. in large numbers and had become a major political force. Kossuth was feted by Congress, and Fillmore allowed a White House meeting after receiving word that Kossuth would not try to politicize it. In spite of his promise, Kossuth made a speech promoting his cause. The American enthusiasm for Kossuth petered out, and he departed for Europe; Fillmore refused to change American policy, remaining neutral.

1852 election and completion of term

As the 1852 United States presidential election, election of 1852 approached, Fillmore remained undecided whether to run for a full term as president. Fillmore's enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Act had made him unpopular among many in the North, but he retained considerable support from the South, where he was seen as the only candidate capable of uniting the party. Secretary Webster had long coveted the presidency and, though in poor health, planned a final attempt to gain the White House. Webster hoped that his pro-Compromise stance would help him garner support throughout the country, but his reputation as the spokesman for New England limited his appeal outside of his home region, especially in the South. Fillmore was sympathetic to the ambitions of his longtime friend, but was reluctant to rule out accepting the party's 1852 nomination, as he feared doing so would allow Seward to gain control of the party. Yet he also believed that the Whig nominee was likely to lose in 1852, and feared that a loss would bring an end to his political career. Ultimately, he refused to pull out of the race, and allowed his supporters to run his campaign for the Whig nomination. A third candidate emerged in the form of General Winfield Scott, who, like previously successful Whig presidential nominees William Henry Harrison and Zachary Taylor, had earned fame for his martial accomplishments. Though Thurlow Weed advised Seward to accept whoever the Whigs nominated, Seward threw his backing behind Scott. Scott had supported the Compromise of 1850, but his association with Seward made him unacceptable to Southern Whigs. Thus, approaching the June1852 Whig National Convention

The 1852 Whig National Convention was a presidential nominating convention held from June 17 to June 20, in Baltimore, Maryland. It nominated the Whig Party's candidates for president and vice president in the 1852 election. The convention s ...

in Baltimore, the major candidates were Fillmore, Webster, and General Scott. Supporters of the Compromise of 1850 were split between Fillmore and Webster, while Northern opponents of the Compromise backed Scott.

Stephen Douglas's role in the Compromise of 1850, along with his aggressive rhetoric in foreign policy, had made him a front-runner for the 1852 Democratic nomination. But by the time of the May 1852 Democratic National Convention, former Secretary of State James Buchanan of Pennsylvania had eclipsed Douglas, who had made several enemies in the party and faced rumors about his drinking. The convention deadlocked between 1848 nominee Lewis Cass of Michigan and Buchanan, each of whom led on different ballots. On the 49th ballot, the party nominated former New Hampshire senator Franklin Pierce, who had been out of national politics for nearly a decade before 1852. The nomination of Pierce, a Northerner sympathetic to the Southern view on slavery, united the Democrats and gave the party a decided advantage in the 1852 campaign.

Historical reputation

According to his biographer, Robert Scarry: "No president of the United States ... has suffered as much ridicule as Millard Fillmore". He ascribed much of the abuse to a tendency to denigrate the presidents who served in the years just prior to the Civil War as lacking in leadership. For example, president Harry S. Truman "characterized Fillmore as a weak, trivial thumb-twaddler who would do nothing to offend anyone", responsible in part for the Civil War. Professional historians are no more kind. Paul Finkelman commented, "on the central issues of the age his vision was myopic and his legacy is worse ... in the end, Fillmore was always on the wrong side of the great moral and political issues". Finkelman argues that the central accomplishment of Fillmore's tenure, the Compromise of 1850, should instead be called the "Appeasement of 1850" due to its abandoning of the

According to his biographer, Robert Scarry: "No president of the United States ... has suffered as much ridicule as Millard Fillmore". He ascribed much of the abuse to a tendency to denigrate the presidents who served in the years just prior to the Civil War as lacking in leadership. For example, president Harry S. Truman "characterized Fillmore as a weak, trivial thumb-twaddler who would do nothing to offend anyone", responsible in part for the Civil War. Professional historians are no more kind. Paul Finkelman commented, "on the central issues of the age his vision was myopic and his legacy is worse ... in the end, Fillmore was always on the wrong side of the great moral and political issues". Finkelman argues that the central accomplishment of Fillmore's tenure, the Compromise of 1850, should instead be called the "Appeasement of 1850" due to its abandoning of the Wilmot Proviso

The Wilmot Proviso was an unsuccessful 1846 proposal in the United States Congress to ban slavery in territory acquired from Mexico in the Mexican–American War. The conflict over the Wilmot Proviso was one of the major events leading to the ...

, thereby opening up all of the territories of the Mexican Cession to slavery.