Federation Of Labor on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The American Federation of Labor (A.F. of L.) was a national federation of

The American Federation of Labor (A.F. of L.) was organized as an association of trade unions in 1886. The organization emerged from a dispute with the

The American Federation of Labor (A.F. of L.) was organized as an association of trade unions in 1886. The organization emerged from a dispute with the

Convinced that no accommodation with the leadership of the Knights of Labor was possible, the heads of the five labor organizations which issued the call for the April 1886 conference issued a new call for a convention to be held December 8, 1886, in

Convinced that no accommodation with the leadership of the Knights of Labor was possible, the heads of the five labor organizations which issued the call for the April 1886 conference issued a new call for a convention to be held December 8, 1886, in

The A.F. of L. faced its first major reversal when employers launched an

The A.F. of L. faced its first major reversal when employers launched an

August 2015, 46 pages Ever the pragmatist, Gompers argued that labor should "reward its friends and punish its enemies" in both major parties. However, in the 1900s (decade), the two parties began to realign, with the main faction of the Republican Party coming to identify with the interests of banks and manufacturers, while a substantial portion of the rival Democratic Party took a more labor-friendly position. While not precluding its members from belonging to the Socialist Party or working with its members, the A.F. of L. traditionally refused to pursue the tactic of independent political action by the workers in the form of the existing Socialist Party or the establishment of a new labor party. After 1908, the organization's tie to the Democratic party grew increasingly strong.

The A.F. of L. vigorously opposed unrestricted immigration from Europe for moral, cultural, and racial reasons. The issue unified the workers who feared that an influx of new workers would flood the labor market and lower wages.

The A.F. of L. vigorously opposed unrestricted immigration from Europe for moral, cultural, and racial reasons. The issue unified the workers who feared that an influx of new workers would flood the labor market and lower wages.

The A.F. of L. and its affiliates were strong supporters of the war effort. The risk of disruptions to war production by labor radicals provided the A.F. of L. political leverage to gain recognition and mediation of labor disputes, often in favor of improvements for workers. The A.F. of L. unions avoided strikes in favor of arbitration. Wages soared as near-full employment was reached at the height of the war. The A.F. of L. unions strongly encouraged young men to enlist in the military, and fiercely opposed efforts to reduce recruiting and slow war production by pacifists, the anti-war

The A.F. of L. and its affiliates were strong supporters of the war effort. The risk of disruptions to war production by labor radicals provided the A.F. of L. political leverage to gain recognition and mediation of labor disputes, often in favor of improvements for workers. The A.F. of L. unions avoided strikes in favor of arbitration. Wages soared as near-full employment was reached at the height of the war. The A.F. of L. unions strongly encouraged young men to enlist in the military, and fiercely opposed efforts to reduce recruiting and slow war production by pacifists, the anti-war

In the pro-business environment of the 1920s, business launched a large-scale offensive on behalf of the so-called "

In the pro-business environment of the 1920s, business launched a large-scale offensive on behalf of the so-called "

During its first years, the A.F. of L. admitted nearly anyone. Gompers opened the A.F. of L. to radical and socialist workers and to some semiskilled and unskilled workers. Women, African Americans, and immigrants joined in small numbers. By the 1890s, the Federation had begun to organize only skilled workers in craft unions and became an organization of mostly white men. Although the A.F. of L. preached a policy of egalitarianism in regard to African-American workers, it actively discriminated against them. The A.F. of L. sanctioned the maintenance of segregated locals within its affiliates, particularly in the construction and railroad industries, a practice that often excluded black workers altogether from union membership and thus from employment in organized industries.

In 1901, the A.F. of L. lobbied Congress to reauthorize the 1882

During its first years, the A.F. of L. admitted nearly anyone. Gompers opened the A.F. of L. to radical and socialist workers and to some semiskilled and unskilled workers. Women, African Americans, and immigrants joined in small numbers. By the 1890s, the Federation had begun to organize only skilled workers in craft unions and became an organization of mostly white men. Although the A.F. of L. preached a policy of egalitarianism in regard to African-American workers, it actively discriminated against them. The A.F. of L. sanctioned the maintenance of segregated locals within its affiliates, particularly in the construction and railroad industries, a practice that often excluded black workers altogether from union membership and thus from employment in organized industries.

In 1901, the A.F. of L. lobbied Congress to reauthorize the 1882

From the beginning, unions affiliated with the A.F. of L. found themselves in conflict when both unions claimed jurisdiction over the same groups of workers: both the Brewers and

From the beginning, unions affiliated with the A.F. of L. found themselves in conflict when both unions claimed jurisdiction over the same groups of workers: both the Brewers and

Employers discovered the efficacy of labor injunctions, first used with great effect by the

Employers discovered the efficacy of labor injunctions, first used with great effect by the

''Some Reasons for Chinese Exclusion. Meat vs. Rice. American Manhood against Asiatic Coolieism. Which Shall Survive?''

Washington, D.C.: American Federation of Labor, 1901. * Gompers, Samuel

''American Labor and the War''

New York: George H. Doran Co., n.d.

''Labor and the Employer''

New York: E.P. Dutton & Co., 1920. * Gompers, Samuel. ''Seventy Years of Life and Labor: An Autobiography''. In two volumes. New York: E.P. Dutton & Co., 1925. * ''The Samuel Gompers Papers''. Currently published in 11 volumes, coverage to 1921. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1991–2009.

excerpt and text search

* Baker, Jay N. "The American Federation of Labor" (1912) * Beik, Millie, ed. ''Labor Relations: Major Issues in American History'' (2005) over 100 annotated primary document

excerpt and text search

* Boris, Eileen, Nelson Lichtenstein, and Thomas Paterson. ''Major Problems In The History Of American Workers: Documents and Essays'' (2002) * Brody, David. ''In Labor's Cause: Main Themes on the History of the American Worker'' (1993

excerpt and text search

* Brooks, George W.; Derber, Milton; McCabe, David A.; and Taft, Philip (eds.), ''Interpreting the Labor Movement''. Madison: Industrial Relations Research Association, 1952. * Browne, Waldo Ralph. ''What's what in the Labor Movement: A Dictionary of Labor Affairs and Labor'' (1921) 577pp; encyclopedia of labor terms, organizations and history

complete text online

* Commons, John R, et al. ''History of Labour in the United States''. esp. ''Vol. 2: 1860–1896'' (1918); ''Vol. 4: Labor Movements, 1896–1932'' (1935). * Currarino, Rosanne. "The Politics of 'More': The Labor Question and the Idea of Economic Liberty in Industrial America." ''Journal of American History''. vol. 93, no. 1 (June 2006). * Dubofsky, Melvyn, and Joseph McCartin. ''Labor in America: A History'' (9th ed. 2017), textbook; originally written by Foster Dulles * Dubofsky, Melvyn, and Warren Van Tine, eds. ''Labor Leaders in America'' (1987) biographies of key leaders, written by scholar

excerpt and text search

* Foner, Philip S. ''History of the Labor Movement in the United States''. In 10 volumes. New York: International Publishers, 1947–1994; ''Vol. 2: From the Founding of the American Federation of Labor to the Emergence of American Imperialism'' (1955); ''Vol. 3: The Policies and Practices of the American Federation of Labor, 1900–1909'' (1964); ''Vol. 5: The AFL in the Progressive Era, 1910–1915'' (1980); ''Vol. 6: On the Eve of America's Entrance into World War I, 1915–1916'' (1982); ''Vol. 7: Labor and World War I, 1914–1918'' (1987); ''Vol. 8: Post-war Struggles, 1918–1920'' (1988). a view from the Left that is hostile to Gompers * Galenson, Walter. ''The CIO Challenge to the AFL: A History of the American Labor Movement, 1935–1941'' (1960) * Greene, Julie. ''Pure and Simple Politics: The American Federation of Labor and Political Activism, 1881–1917'' (1998) ** Greene, Julia Marie. "The strike at the ballot box: Politics and partisanship in the American Federation of Labor, 1881-1916" (PhD dissertation, Yale University; ProQuest Dissertations & Theses, 1990. 9121103). * Karson, Marc. ''American Labor Unions and Politics, 1900–1918''. (Southern Illinois University Press, 1958). * Kersten, Andrew E. ''Labor's home front: the American Federation of Labor during World War II'' (NYU Press, 2006)

online

* Lichtenstein, Nelson. ''State of the Union: A Century of American Labor'' (2003

excerpt and text search

* Livesay, Harold C. ''Samuel Gompers and Organized Labor in America'' (1993), short biograph

online

* McCartin, Joseph A. ''Labor's Great War: The Struggle for Industrial Democracy and the Origins of Modern American Labor Relations, 1912–21''. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1997. * Mandel, Bernard. ''Samuel Gompers: A Biography'' (1963), highly detailed negative biography * Mink, Gwendolyn. ''Old Labor and New Immigrants in American Political Development: Union, Party, and State, 1875–1920'' (1986) * Orth, Samuel Peter

''The Armies of Labor: A Chronicle of the Organized Wage-Earners''

New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1919. * Roberts, William C. (ed.)

''American Federation of Labor: History, Encyclopedia, Reference Book''

Washington, DC: American Federation of Labor, 1919. * Taft, Philip. ''The A.F. of L. in the Time of Gompers''. (Harper, 1957)

online

** Taft, Philip. ''The A.F. of L. from the Death of Gompers to the Merger''. (Harper, 1959

online vol 2

Major scholarly studies * Walker, Roger W. "The AFL and child-labor legislation: An exercise in frustration." ''Labor History'' 11.3 (1970): 323–340.

Washington State Federation of Labor Records

1881–1967. 45.44 cubic feet (including 2 microfilm reels, 1 package, and 1 vertical file). At th

Labor Archives of Washington, University of Washington Libraries Special Collections

Harry E. B. Ault Papers

1899–1965. 5.46 cubic feet. At th

Labor Archives of Washington, University of Washington Libraries Special Collections

Leo F. Flynn Papers

1890–1970. 1.09 cubic feet (2 boxes). At th

Labor Archives of Washington, University of Washington Libraries Special Collections

George E. Rennar Papers

1933–1972. approximately 34.73 cubic feet. At th

Labor Archives of Washington, University of Washington Libraries Special Collections

Unions of the AFL–CIO

List and links to AFL–CIO affiliated

George Meany Memorial AFL–CIO Archive

at the

labor unions in the United States

Labor unions represent United States workers in many industries recognized under US labor law since the 1935 enactment of the National Labor Relations Act. Their activity centers on collective bargaining over wages, benefits, and working cond ...

that continues today as the AFL-CIO

The American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO) is a national trade union center that is the largest federation of unions in the United States. It is made up of 61 national and international unions, together r ...

. It was founded in Columbus, Ohio

Columbus (, ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital and List of cities in Ohio, most populous city of the U.S. state of Ohio. With a 2020 United States census, 2020 census population of 905,748, it is the List of United States ...

, in 1886 by an alliance of craft unions eager to provide mutual support and disappointed in the Knights of Labor

The Knights of Labor (K of L), officially the Noble and Holy Order of the Knights of Labor, was the largest American labor movement of the 19th century, claiming for a time nearly one million members. It operated in the United States as well in ...

. Samuel Gompers

Samuel Gompers (; January 27, 1850December 11, 1924) was a British-born American cigar maker, labor union leader and a key figure in American labor history. Gompers founded the American Federation of Labor (AFL) and served as the organization's ...

was elected the full-time president at its founding convention and was re-elected every year except one until his death in 1924. He became the major spokesperson for the union movement.

The A.F. of L. was the largest union grouping, even after the creation of the Congress of Industrial Organizations

The Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) was a federation of Labor unions in the United States, unions that organized workers in industrial unionism, industrial unions in the United States and Canada from 1935 to 1955. Originally created in ...

(CIO) by unions that were expelled by the A.F. of L. in 1935. The A.F. of L. was founded and dominated by craft unions

Craft unionism refers to a model of trade unionism in which workers are organised based on the particular craft or trade in which they work. It contrasts with industrial unionism, in which all workers in the same industry are organized into the sa ...

, especially in the building trades. In the late 1930s, craft affiliates expanded by organizing on an industrial union

Industrial unionism is a trade union organising method through which all workers in the same industry are organized into the same union, regardless of skill or trade, thus giving workers in one industry, or in all industries, more leverage in ba ...

basis to meet the challenge from the CIO. The A.F. of L. and the CIO competed bitterly in the late 1930s but then cooperated during World War II and afterward. In 1955, the two merged to create the AFL-CIO

The American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO) is a national trade union center that is the largest federation of unions in the United States. It is made up of 61 national and international unions, together r ...

, which has comprised the longest lasting and most influential labor federation in the United States to this day.

Organizational history

Origins

The American Federation of Labor (A.F. of L.) was organized as an association of trade unions in 1886. The organization emerged from a dispute with the

The American Federation of Labor (A.F. of L.) was organized as an association of trade unions in 1886. The organization emerged from a dispute with the Knights of Labor

The Knights of Labor (K of L), officially the Noble and Holy Order of the Knights of Labor, was the largest American labor movement of the 19th century, claiming for a time nearly one million members. It operated in the United States as well in ...

(K of L) organization, in which the leadership of that organization solicited locals of various craft unions

Craft unionism refers to a model of trade unionism in which workers are organised based on the particular craft or trade in which they work. It contrasts with industrial unionism, in which all workers in the same industry are organized into the sa ...

to withdraw from their International organizations and to affiliate with the K of L directly, an action which would have moved funds from the various unions to the K of L. The Federation of Organized Trades and Labor Unions

The Federation of Organized Trades and Labor Unions of the United States and Canada (FOTLU) was a federation of labor unions created on November 15, 1881, at Turner Hall in Pittsburgh. It changed its name to the American Federation of Labor (AF ...

also merged into what would become the American Federation of Labor.

One of the organizations embroiled in this controversy was the Cigar Makers' International Union

The Journeymen Cigar Makers' International Union of America (CMIU) was a labor union established in 1864 that represented workers in the cigar industry. The CMIU was part of the American Federation of Labor from 1887 until its merger in 1974.

Org ...

(CMIU), a group subject to competition from a dual union

Dual unionism is the development of a union or political organization parallel to and within an existing labor union. In some cases, the term may refer to the situation where two unions claim the right to organize the same workers.

Dual unionism ...

, a rival "Progressive Cigarmakers' Union", organized by members suspended or expelled by the CMIU.Foner, ''History of the Labor Movement in the United States: Volume 2,'' pg. 134. The two cigar unions competed with one another in signing contracts with various cigar manufacturers, who were at this same time combining themselves into manufacturers' associations of their own in New York City, Detroit

Detroit ( , ) is the List of municipalities in Michigan, most populous city in the U.S. state of Michigan. It is situated on the bank of the Detroit River across from Windsor, Ontario. It had a population of 639,111 at the 2020 United State ...

, Cincinnati

Cincinnati ( ; colloquially nicknamed Cincy) is a city in Hamilton County, Ohio, United States, and its county seat. Settled in 1788, the city is located on the northern side of the confluence of the Licking River (Kentucky), Licking and Ohio Ri ...

, Chicago, and Milwaukee

Milwaukee is the List of cities in Wisconsin, most populous city in the U.S. state of Wisconsin. Located on the western shore of Lake Michigan, it is the List of United States cities by population, 31st-most populous city in the United States ...

.

In January 1886, the Cigar Manufacturers' Association of New York City announced a 20 percent wage cut in factories around the city. The Cigar Makers' International Union refused to accept the cut and 6,000 of its members in 19 factories were locked out by the owners. A strike

Strike may refer to:

People

*Strike (surname)

* Hobart Huson, author of several drug related books

Physical confrontation or removal

*Strike (attack), attack with an inanimate object or a part of the human body intended to cause harm

* Airstrike, ...

lasting four weeks ensued.Foner, ''History of the Labor Movement in the United States: Volume 2,'' pg. 135. Just when it appeared that the strike might be won, the New York District Assembly of the Knights of Labor leaped into the breach, offering to settle with the 19 factories at a lower wage scale than that proposed by the CMIU, so long as only the Progressive Cigarmakers' Union was employed.

The leadership of the CMIU was enraged and demanded that the New York District Assembly be investigated and punished by the national officials of the Knights of Labor. The committee of investigation was controlled by individuals friendly to the New York District Assembly, however, and the latter was exonerated. The American Federation of Labor was thus originally formed as an alliance of craft unions outside the Knights of Labor as a means of defending themselves against this and similar incursions.Foner, ''History of the Labor Movement in the United States: Volume 2,'' pg. 136.

On April 25, 1886, a circular letter was issued by Adolph Strasser

Adolph Strasser (1843–1939), born in the Austrian Empire, was an American trade union organizer. Strasser is best remembered as a founder of the United Cigarmakers Union and the American Federation of Labor (AF of L). Strasser was additionally t ...

of the Cigar Makers and P. J. McGuire of the Carpenters, addressed to all national trade unions and calling for their attendance of a conference in Philadelphia

Philadelphia ( ), colloquially referred to as Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania, most populous city in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania and the List of United States cities by population, sixth-most populous city in the Unit ...

on May 18. The call stated that an element of the Knights of Labor was doing "malicious work" and causing "incalculable mischief by arousing antagonisms and dissensions in the labor movement." The call was signed by Strasser and McGuire, along with representatives of the Granite Cutters, the Iron Molders, and the secretary of the Federation of Trades of North America, a forerunner of the A.F. of L. founded in 1881.

Forty-three invitations were mailed, which drew the attendance of 20 delegates and letters of approval from 12 other unions. At this preliminary gathering, held in Donaldson Hall on the corner of Broad and Filbert Streets, the K of L was charged with conspiring with anti-union bosses to provide labor at below going union rates and with making use of individuals who had crossed picket lines or defaulted on payment of union dues.Foner, ''History of the Labor Movement in the United States: Volume 2,'' pg. 137. The body authored a "treaty" to be presented to the forthcoming May 24, 1886, convention of the Knights of Labor, which demanded that the K of L cease attempting to organize members of International Unions into its own assemblies without permission of the unions involved and that K of L organizers violating this provision should suffer immediate suspension.

For its part, the Knights of Labor considered the demand for the parcelling of the labor movement into narrow craft-based fiefdoms to be anathema, a violation of the principle of solidarity of all workers across craft lines. Negotiations with the dissident craft unions were nipped in the bud by the governing General Assembly of the K of L, however, with the organization's Grand Master Workman, Terence V. Powderly

Terence Vincent Powderly (January 22, 1849 – June 24, 1924) was an American labor union leader, politician and attorney, who was the Grand Master Workman of the Knights of Labor from 1879 to 1893.

Born in Carbondale, Pennsylvania, he was late ...

refusing to enter into serious discussions on the matter. The actions of the New York District Assembly of the K of L were upheld.

Formation and early years

Convinced that no accommodation with the leadership of the Knights of Labor was possible, the heads of the five labor organizations which issued the call for the April 1886 conference issued a new call for a convention to be held December 8, 1886, in

Convinced that no accommodation with the leadership of the Knights of Labor was possible, the heads of the five labor organizations which issued the call for the April 1886 conference issued a new call for a convention to be held December 8, 1886, in Columbus, Ohio

Columbus (, ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital and List of cities in Ohio, most populous city of the U.S. state of Ohio. With a 2020 United States census, 2020 census population of 905,748, it is the List of United States ...

, in order to construct "an American federation of alliance of all national and international trade unions." Forty-two delegates representing 13 national unions and various other local labor organizations responded to the call, agreeing to form themselves into an American Federation of Labor.

Revenue for the new organization was to be raised on the basis of a "per-capita tax" of its member organizations, set at the rate of one-half cent per member per month (i.e. six cents per year, equal to $ today).Foner, ''History of the Labor Movement in the United States: Volume 2,'' pg. 143. Governance of the organization was to be by annual conventions, with one delegate allocated for every 4,000 members of each affiliated union. The founding convention voted to make the President of the new federation a full-time official at a salary of $1,000 per year (equal to $ today), and Samuel Gompers

Samuel Gompers (; January 27, 1850December 11, 1924) was a British-born American cigar maker, labor union leader and a key figure in American labor history. Gompers founded the American Federation of Labor (AFL) and served as the organization's ...

of the Cigar Makers' International Union was elected to the position. Gompers would ultimately be re-elected to the position by annual conventions of the organization for every year save one until his death nearly four decades later.

Although the founding convention of the A.F. of L. had authorized the establishment of a publication for the new organization, Gompers made use of the existing labor press to generate support for the position of the craft unions against the Knights of Labor. Powerful opinion-makers of the American labor movement such as the Philadelphia ''Tocsin,'' ''Haverhill Labor,'' the ''Brooklyn Labor Press,'' and the ''Denver Labor Enquirer'' granted Gompers space in their pages, in which he made the case for the unions against the attacks of employers, "all too often aided by the K of L."

Headway was made in the form of endorsement by various local labor bodies. Some assemblies of the K of L supported the Cigar Makers' position and departed the organization: in Baltimore

Baltimore is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland. With a population of 585,708 at the 2020 census and estimated at 568,271 in 2024, it is the 30th-most populous U.S. city. The Baltimore metropolitan area is the 20th-large ...

, 30 locals left the organization, while the membership of the Knights in Chicago fell from 25,000 in 1886 to just 3,500 in 1887. Factional warfare broke out in the K of L, with Terence Powderly blaming the organization's travails on "radicals" in its ranks, while those opposing Powderly called for an end to what they perceived as "autocratic leadership".

In the face of the steady disintegration of its rival, the fledgling American Federation of Labor struggled to maintain itself, with the group showing very slow and incremental growth in its first years, only cracking the 250,000 member mark in 1892.William C. Roberts (ed.), ''American Federation of Labor: History, Encyclopedia, Reference Book''. Washington, DC: American Federation of Labor, 1919; pg. 63. The group from the outset concentrated upon the income and working conditions of its membership as its almost sole focus. The A.F. of L.'s founding convention declaring "higher wages and a shorter workday" to be "preliminary steps toward great and accompanying improvements in the condition of the working people." Participation in partisan politics was avoided as inherently divisive, and the group's constitution was structured to prevent the admission of political parties as affiliates.

This fundamentally conservative "pure and simple" approach limited the A.F. of L. to matters pertaining to working conditions and rates of pay, relegating political goals to its allies in the political sphere. The Federation favored pursuit of workers' immediate demands rather than challenging the property rights of owners, and took a pragmatic view of politics which favored tactical support for particular politicians over formation of a party devoted to workers' interests. The A.F. of L.'s leadership believed the expansion of the capitalist system was seen as the path to betterment of labor, an orientation making it possible for the A.F. of L. to present itself as what one historian has called "the conservative alternative to working class radicalism".

Early 20th century

The A.F. of L. faced its first major reversal when employers launched an

The A.F. of L. faced its first major reversal when employers launched an open shop

An open shop is a place of employment at which one is not required to join or financially support a union ( closed shop) as a condition of hiring or continued employment.

Open shop vs closed shop

The major difference between an open and closed ...

movement in 1903, designed to drive unions out of construction, mining, longshore and other industries. Membership in the A.F. of L.'s affiliated unions declined between 1904 and 1914 in the face of this concerted anti-union drive, which made effective use of legal injunction

An injunction is an equitable remedy in the form of a special court order compelling a party to do or refrain from doing certain acts. It was developed by the English courts of equity but its origins go back to Roman law and the equitable rem ...

s against strikes, court rulings given force when backed with the armed might of the state.

At its November 1907 Convention in Norfolk, Virginia, the A.F. of L. founded the future North America's Building Trades Unions

The Building and Construction Trades Department, commonly known as North America's Building Trades Unions (NABTU), is a trade department of the American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL–CIO) with 14 affiliated ...

(NABTU) as its Department of Building Trades.Constitution of NABTUAugust 2015, 46 pages Ever the pragmatist, Gompers argued that labor should "reward its friends and punish its enemies" in both major parties. However, in the 1900s (decade), the two parties began to realign, with the main faction of the Republican Party coming to identify with the interests of banks and manufacturers, while a substantial portion of the rival Democratic Party took a more labor-friendly position. While not precluding its members from belonging to the Socialist Party or working with its members, the A.F. of L. traditionally refused to pursue the tactic of independent political action by the workers in the form of the existing Socialist Party or the establishment of a new labor party. After 1908, the organization's tie to the Democratic party grew increasingly strong.

National Civic Federation

Some unions within the A.F. of L. helped form and participated in theNational Civic Federation

The National Civic Federation (NCF) was an American economic organization founded in 1900 which brought together chosen representatives of big business and organized labor, as well as consumer advocates in an attempt to ameliorate labor disputes. I ...

. The National Civic Federation was formed by several progressive employers who sought to avoid labor disputes by fostering collective bargaining and "responsible" unionism.

Major Republican leaders, such as President William McKinley

William McKinley (January 29, 1843September 14, 1901) was the 25th president of the United States, serving from 1897 until Assassination of William McKinley, his assassination in 1901. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Repub ...

and Senator Mark Hanna

Marcus Alonzo Hanna (September 24, 1837 – February 15, 1904) was an American businessman and Republican politician who served as a United States Senator from Ohio as well as chairman of the Republican National Committee. A friend and ...

, made pro-labor statements. According to Gwendolyn Mink: The escalation in labor disruptions and the expansion in union membership encouraged business leaders to promote union-employer cooperation in order to rationalize production and maximize efficiency. The AFL was the linchpin of such cooperation. Where AFL unions existed, the AFL could be called upon to manage labor conflict; equally important, the AFL was unlikely to sacrifice its organization to the volatility of industrial unionism.Labor's participation in the National Civic Federation created internal division within the A.F. of L. The Socialist elemet who believed the only way to help workers was to remove large industry from private ownership, denounced labor's efforts at cooperation with the capitalists. The A.F. of L. nonetheless continued its association with the group, which declined in importance as the decade of the 1910s drew to a close.

Canada

By the 1890s, Gompers was planning an international federation of labor, starting with the expansion of A.F. of L. affiliates in Canada, especially Ontario. He helped the Canadian Trades and Labour Congress with money and organizers, and by 1902, the A.F. of L. came to dominate the Canadian union movement.Immigration restriction

The A.F. of L. vigorously opposed unrestricted immigration from Europe for moral, cultural, and racial reasons. The issue unified the workers who feared that an influx of new workers would flood the labor market and lower wages.

The A.F. of L. vigorously opposed unrestricted immigration from Europe for moral, cultural, and racial reasons. The issue unified the workers who feared that an influx of new workers would flood the labor market and lower wages. Nativism

Nativism may refer to:

* Nativism (politics), ethnocentric beliefs relating to immigration and nationalism

* Nativism (psychology), a concept in psychology and philosophy which asserts certain concepts are "native" or in the brain at birth

* Lingu ...

was not a factor because upwards of half the union members were themselves immigrants or the sons of immigrants from Ireland, Germany and Britain. Nativism was a factor when the A.F. of L. even more strenuously opposed all immigration from Asia because it represented (to its Euro-American members) an alien culture that could not be assimilated into American society. The A.F. of L. intensified its opposition after 1906 and was instrumental in passing immigration restriction bills from the 1890s to the 1920s, such as the 1921 Emergency Quota Act

__NOTOC__

The Emergency Quota Act, also known as the Emergency Immigration Act of 1921, the Immigration Restriction Act of 1921, the Per Centum Law, and the Johnson Quota Act (ch. 8, of May 19, 1921), was formulated mainly in response to the lar ...

and the Immigration Act of 1924

The Immigration Act of 1924, or Johnson–Reed Act, including the Asian Exclusion Act and National Origins Act (), was a United States federal law that prevented immigration from Asia and set quotas on the number of immigrants from every count ...

, and seeing that they were strictly enforced.

Mink (1986) concludes that the link between the A.F. of L. and the Democratic Party rested in part on immigration issues, noting the large corporations, which supported the Republicans, wanted more immigration to augment their labor force.

Prohibition gained strength as the German American community came under fire. The A.F. of L. was against prohibition as it was viewed as cultural right of the working class to drink.

Coalition against child labor

Child labor

Child labour is the exploitation of children through any form of work that interferes with their ability to attend regular school, or is mentally, physically, socially and morally harmful. Such exploitation is prohibited by legislation w ...

was an issue on which the A.F. of L. found common ground with middle class reformers who otherwise kept their distance. The A.F. of L. joined campaigns at the state and national level to limit the employment of children under age 14. In 1904 a major national organization emerged, the National Child Labor Committee

The National Child Labor Committee (NCLC) was a private, non-profit organization in the United States that served as a leading proponent for the national child labor reform movement. Its mission was to promote "the rights, awareness, dignity, well ...

(NCLC). In state after state reformers launched crusades to pass laws restricting child labor, with the ultimate goals of rescuing young bodies and increasing school attendance. The frustrations included the Supreme Court striking down two national laws as unconstitutional, and weak enforcement of state laws due to the political influence of employers.

World War I and after: 1917–1921

The A.F. of L. and its affiliates were strong supporters of the war effort. The risk of disruptions to war production by labor radicals provided the A.F. of L. political leverage to gain recognition and mediation of labor disputes, often in favor of improvements for workers. The A.F. of L. unions avoided strikes in favor of arbitration. Wages soared as near-full employment was reached at the height of the war. The A.F. of L. unions strongly encouraged young men to enlist in the military, and fiercely opposed efforts to reduce recruiting and slow war production by pacifists, the anti-war

The A.F. of L. and its affiliates were strong supporters of the war effort. The risk of disruptions to war production by labor radicals provided the A.F. of L. political leverage to gain recognition and mediation of labor disputes, often in favor of improvements for workers. The A.F. of L. unions avoided strikes in favor of arbitration. Wages soared as near-full employment was reached at the height of the war. The A.F. of L. unions strongly encouraged young men to enlist in the military, and fiercely opposed efforts to reduce recruiting and slow war production by pacifists, the anti-war Industrial Workers of the World

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), whose members are nicknamed "Wobblies", is an international labor union founded in Chicago, United States in 1905. The nickname's origin is uncertain. Its ideology combines general unionism with indu ...

(IWW) and the radical faction of Socialists. To keep factories running smoothly, President Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was the 28th president of the United States, serving from 1913 to 1921. He was the only History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democrat to serve as president during the Prog ...

established the National War Labor Board in 1918, which forced management to negotiate with existing unions. Wilson also appointed A.F. of L. president Gompers to the powerful Council of National Defense

The Council of National Defense was a United States organization formed during World War I to coordinate resources and industry in support of the war effort, including the coordination of transportation, industrial and farm production, financial s ...

, where he set up the War Committee on Labor.

The A. F. of L. was strongly committed to the national war aims and cooperated closely with Washington. It used the opportunity to grow rapidly. It worked out an informal agreement with the United States government, in which the A.F. of L. would coordinate with the government both to support the war effort and to join "into an alliance to crush radical labor groups" that opposed the war effort, especially the Industrial Workers of the World

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), whose members are nicknamed "Wobblies", is an international labor union founded in Chicago, United States in 1905. The nickname's origin is uncertain. Its ideology combines general unionism with indu ...

and Socialist Party of America

The Socialist Party of America (SPA) was a socialist political party in the United States formed in 1901 by a merger between the three-year-old Social Democratic Party of America and disaffected elements of the Socialist Labor Party of America ...

.

Gompers chaired the wartime Labor Advisory Board. He attended the Paris Peace Conference Agreements and declarations resulting from meetings in Paris include:

Listed by name

Paris Accords

may refer to:

* Paris Accords, the agreements reached at the end of the London and Paris Conferences in 1954 concerning the post-war status of Germ ...

in 1919 as an official advisor on labor issues.

In 1920, the A.F. of L. petitioned Washington for the release of prisoners who had been convicted under Wartime Emergency Laws. Wilson did not act but President Warren Harding did so.

1919—the first year of peace—was one of turmoil in the labor movement. A.F. of L. membership soared to 2.4 million in 1917 and 4.1 million at the end of 1919. The A.F. of L. unions tried to make their gains permanent and called a series of major strikes in meat, steel and other industries. The strikes ultimately failed. Many African Americans had taken war jobs; other became strikebreakers in 1919. Racial tensions were high, with major race riots. The economy was very prosperous during the war but entered a postwar recession. In general, workers lost out and the A.F. of L. lost influence.

1920s

In the pro-business environment of the 1920s, business launched a large-scale offensive on behalf of the so-called "

In the pro-business environment of the 1920s, business launched a large-scale offensive on behalf of the so-called "open shop

An open shop is a place of employment at which one is not required to join or financially support a union ( closed shop) as a condition of hiring or continued employment.

Open shop vs closed shop

The major difference between an open and closed ...

", which meant that a person did not have to be a union member to be hired. A.F. of L. unions lost membership steadily until 1933. In 1924, following the death of Samuel Gompers, UMWA

The United Mine Workers of America (UMW or UMWA) is a North American labor union best known for representing coal miners. Today, the Union also represents health care workers, truck drivers, manufacturing workers and public employees in the Unit ...

member and A.F. of L. vice president William Green became the president of the labor federation.

The organization endorsed pro-labor progressive Robert M. La Follette

Robert Marion La Follette Sr. (June 14, 1855June 18, 1925), nicknamed "Fighting Bob," was an American lawyer and politician. He represented Wisconsin in both chambers of Congress and served as the 20th governor of Wisconsin from 1901 to 1906. ...

in the 1924 presidential election. He only carried his home state of Wisconsin. The campaign failed to establish a permanent independent party closely connected to the labor movement, however, and thereafter the Federation embraced ever more closely the Democratic Party, despite the fact that many union leaders remained Republicans. Herbert Hoover

Herbert Clark Hoover (August 10, 1874 – October 20, 1964) was the 31st president of the United States, serving from 1929 to 1933. A wealthy mining engineer before his presidency, Hoover led the wartime Commission for Relief in Belgium and ...

in 1928 won the votes of many Protestant A.F. of L. members.

New Deal

TheGreat Depression

The Great Depression was a severe global economic downturn from 1929 to 1939. The period was characterized by high rates of unemployment and poverty, drastic reductions in industrial production and international trade, and widespread bank and ...

were hard times for the unions, and membership fell sharply across the country. As the national economy began to recover in 1933, so did union membership. The New Deal

The New Deal was a series of wide-reaching economic, social, and political reforms enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1938, in response to the Great Depression in the United States, Great Depressi ...

of president Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), also known as FDR, was the 32nd president of the United States, serving from 1933 until his death in 1945. He is the longest-serving U.S. president, and the only one to have served ...

, a Democrat, strongly favored labor unions. He made sure that relief operations like the Civilian Conservation Corps

The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) was a voluntary government unemployment, work relief program that ran from 1933 to 1942 in the United States for unemployed, unmarried men ages 18–25 and eventually expanded to ages 17–28. The CCC was ...

did not include a training component that would produce skilled workers who would compete with union members in a still glutted market. The major legislation was the National Labor Relations Act

The National Labor Relations Act of 1935, also known as the Wagner Act, is a foundational statute of United States labor law that guarantees the right of private sector employees to organize into trade unions, engage in collective bargaining, an ...

of 1935, called the Wagner Act

The National Labor Relations Act of 1935, also known as the Wagner Act, is a foundational statute of United States labor law that guarantees the right of private sector employees to organize into trade unions, engage in collective bargaining, an ...

. It greatly strengthened organized unions, especially by weakening the company unions that many workers belonged to. It was to the members advantage to transform a company union into a local of an A.F. of L. union, and thousands did so, dramatically boosting the membership. The Wagner Act also set up to the National Labor Relations Board

The National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) is an Independent agencies of the United States government, independent agency of the federal government of the United States that enforces United States labor law, U.S. labor law in relation to collect ...

, which used its powers to rule in favor of unions and against the companies.

In the early 1930s, A.F. of L. president William Green (president, 1924–1952) experimented with an industrial approach to organizing in the automobile and steel industries. The A.F. of L. made forays into industrial unionism

Industrial unionism is a trade union organising method through which all workers in the same industry are organized into the same union, regardless of skill or trade, thus giving workers in one industry, or in all industries, more leverage in b ...

by chartering federal labor unions, which would organize across an industry and be chartered by the Federation, not through existing craft unions, guilds, or brotherhoods. As early as 1923, the A.F. of L. had chartered federal labor unions, including six news writer locals that had formerly been part of the International Typographical Union

The International Typographical Union (ITU) was a North American trade union for the printing trade of newspapers and other media. It was founded on May 3, 1852, in the United States as the National Typographical Union. It changed its name to the ...

. However, in the 1930s the A.F. of L. began chartering these federal labor unions as an industrial organizing strategy. The dues in these federal labor unions (FLUs) were kept intentionally low to make them more accessible to low paid industrial workers; however, these low dues later allowed the Internationals in the Federation to deny members of FLUs voting membership at conventions. In 1933, Green sent William Collins to Detroit to organize automobile workers into a federal labor union. That same year workers at the Westinghouse plant in East Springfield MA, members of federal labor union 18476, struck for recognition. In 1933, the A.F. of L. received 1,205 applications for charters for federal labor unions, 1006 of which were granted. By 1934, the A.F. of L. had successfully organized 32,500 autoworkers using the federal labor union model. Most of the leadership of the craft union internationals that made up the federation, advocated for the FLU's to be absorbed into existing craft union internationals and for these internationals to have supremacy of jurisdiction. At the 1933 A.F. of L. convention in Washington, DC, John Frey of the Molders and Metal Trades pushed for craft union internationals to have jurisdictional supremacy over the FLU's; the Carpenters

Carpentry is a skilled trade and a craft in which the primary work performed is the cutting, shaping and installation of building materials during the construction of buildings, ships, timber bridges, concrete formwork, etc. Carpenters trad ...

headed by William Hutchenson and the IBEW

The International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers (IBEW) is a labor union that represents approximately 820,000 workers and retirees in the electrical industry in the United States, Canada, Guam, Panama, Puerto Rico, and the US Virgin Islands; i ...

also pushed for FLU's to turn over their members to the authority of the craft internationals between 1933 and 1935. In 1934, one hundred FLUs met separately and demanded that the A.F. of L. continue to issue charters to unions organizing on an industrial basis independent of the existing craft union internationals. In 1935 the FLUs representing autoworkers and rubber workers both held conventions independent of the craft union internationals.

By the 1935 A.F. of L. convention, Green and the advocates of traditional craft unionism faced increasing dissension led by John L. Lewis

John Llewellyn Lewis (February 12, 1880 – June 11, 1969) was an American leader of Labor unions in the United States, organized labor who served as president of the United Mine Workers, United Mine Workers of America (UMW) from 1920 to 1960. ...

of the coal miners, Sidney Hillman of the Amalgamated

Amalgamation is the process of combining or uniting multiple entities into one form.

Amalgamation, amalgam, and other derivatives may refer to:

Mathematics and science

* Amalgam (chemistry), the combination of mercury with another metal

**Pan ama ...

, David Dubinsky of the Garment Workers

Clothing industry or garment industry summarizes the types of trade and industry along the production and value chain of clothing and garments, starting with the textile industry (producers of cotton, wool, fur, and synthetic fibre), embellishme ...

, Charles Howard of the ITU

The International Telecommunication Union (ITU)In the other common languages of the ITU:

*

* is a specialized agency of the United Nations responsible for many matters related to information and communication technologies. It was established ...

, Thomas McMahon of the Textile Workers

Textile is an umbrella term that includes various fiber-based materials, including fibers, yarns, filaments, threads, and different types of fabric. At first, the word "textiles" only referred to woven fabrics. However, weaving is not ...

, and Max Zaritsky of the Hat, Cap, and Millinery Workers, in addition to the members of the FLU's themselves. Lewis argued that the A.F.of L. was too heavily oriented toward traditional craftsmen, and was overlooking the opportunity to organize millions of semiskilled workers, especially those in industrial factories that made automobiles, rubber, glass and steel. In 1935 Lewis led the dissenting unions in forming a new Congress for Industrial Organization (CIO) within the A.F. of L. Both the new CIO industrial unions, and the older A.F. of L. crafts unions grew rapidly after 1935. President Franklin D. Roosevelt became a hero to them. He won reelection in a landslide in 1936, and by a closer margin in 1940. Labor unions gave strong support in 1940, compared to very strong support in 1936. The Gallup Poll showed CIO voters declined from 85% in 1935 to 79% in 1940. A.F. of L. voters went from 80% to 71%. Other union members went from 74% to 57%. Blue collar workers who were not union members went 72% to 64%.

World War II and merger

The A.F. of L. retained close ties to the Democratic machines in big cities through the 1940s. Its membership surged during the war and it held on to most of its new members after wartime legal support for labor was removed. Despite its close connections to many in Congress, the A.F. of L. was not able to block theTaft–Hartley Act

The Labor Management Relations Act, 1947, better known as the Taft–Hartley Act, is a Law of the United States, United States federal law that restricts the activities and power of trade union, labor unions. It was enacted by the 80th United S ...

in 1947. Also in 1947, the union supported the strike efforts of thousands of switchboard operators by donating thousands of dollars.

In 1955, the A.F. of L. and CIO merged to form the AFL-CIO

The American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO) is a national trade union center that is the largest federation of unions in the United States. It is made up of 61 national and international unions, together r ...

, headed by George Meany

William George Meany (August 16, 1894 – January 10, 1980) was an American labor union administrator for 57 years. He was a vital figure in the creation of the AFL–CIO and served as its first president, from 1955 to 1979.

Meany, the son of a ...

.

Historical problems

Racism

During its first years, the A.F. of L. admitted nearly anyone. Gompers opened the A.F. of L. to radical and socialist workers and to some semiskilled and unskilled workers. Women, African Americans, and immigrants joined in small numbers. By the 1890s, the Federation had begun to organize only skilled workers in craft unions and became an organization of mostly white men. Although the A.F. of L. preached a policy of egalitarianism in regard to African-American workers, it actively discriminated against them. The A.F. of L. sanctioned the maintenance of segregated locals within its affiliates, particularly in the construction and railroad industries, a practice that often excluded black workers altogether from union membership and thus from employment in organized industries.

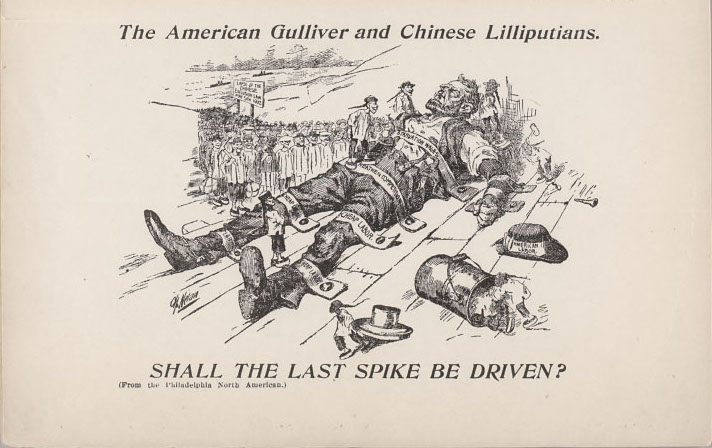

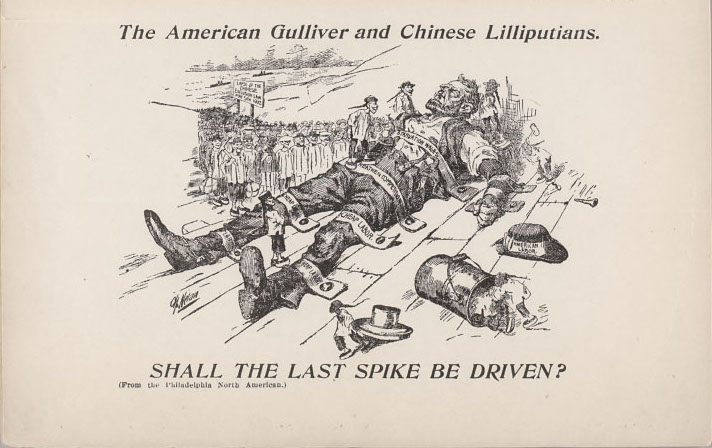

In 1901, the A.F. of L. lobbied Congress to reauthorize the 1882

During its first years, the A.F. of L. admitted nearly anyone. Gompers opened the A.F. of L. to radical and socialist workers and to some semiskilled and unskilled workers. Women, African Americans, and immigrants joined in small numbers. By the 1890s, the Federation had begun to organize only skilled workers in craft unions and became an organization of mostly white men. Although the A.F. of L. preached a policy of egalitarianism in regard to African-American workers, it actively discriminated against them. The A.F. of L. sanctioned the maintenance of segregated locals within its affiliates, particularly in the construction and railroad industries, a practice that often excluded black workers altogether from union membership and thus from employment in organized industries.

In 1901, the A.F. of L. lobbied Congress to reauthorize the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act

The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 was a United States Code, United States federal law signed by President Chester A. Arthur on May 6, 1882, prohibiting all immigration of Chinese laborers for 10 years. The law made exceptions for travelers an ...

, and issued a pamphlet entitled "Some reasons for Chinese Exclusion. Meat vs. Rice. American Manhood against Asiatic Coolieism. Which shall survive?". The A.F. of L. also began one of the first organized labor boycotts when they began putting white stickers on the cigars made by unionized white cigar rollers while simultaneously discouraging consumers from purchasing cigars rolled by Chinese workers.

Sexism

In most ways, the A.F. of L.'s treatment of women workers paralleled its policy towards black workers. The A.F. of L. never adopted a strict policy of gender exclusion and, at times, even came out in favor of women's unionism. However, despite such rhetoric, it only half-heartedly supported women's attempts to organize and, more often, took pains to keep women out of unions and the workforce altogether. Only two national unions affiliated with the A.F. of L. at its founding openly included women, and others passed bylaws barring women's membership entirely. The A.F. of L. hired its first female organizer,Mary Kenney O'Sullivan

Mary Kenney O'Sullivan (January 8, 1864 – January 18, 1943), was an organizer in the early U.S. labor movement. She learned early the importance of unions from poor treatment received at her first job in dressmaking. Making a career in bookbind ...

, only in 1892, released her after five months, and it did not replace her or hire another woman

A woman is an adult female human. Before adulthood, a female child or Adolescence, adolescent is referred to as a girl.

Typically, women are of the female sex and inherit a pair of X chromosomes, one from each parent, and women with functi ...

national organizer until 1908. Women who organized their own unions were often turned down in bids to join the Federation, and even women who did join unions found them hostile or intentionally inaccessible. Unions often held meetings at night or in bars when women might find it difficult to attend and where they might feel uncomfortable, and male unionists heckled women who tried to speak at meetings.

Generally, the A.F. of L. viewed women workers as competition, strikebreakers, or an unskilled labor reserve that kept wages low. As such, it often opposed women's employment entirely. When it organized women workers, it most often did so to protect men's jobs and earning power, not to improve the conditions, lives, or wages of women workers. In response, most women workers remained outside the labor movement. In 1900, only 3.3% of working women were organized into unions. In 1910, even as the A.F. of L. surged forward in membership, that number had dipped to 1.5%. It improved to 6.6% over the next decade, but women remained mostly outside of unions and practically invisible inside of them into the mid-1920s.

Attitudes gradually changed within the A.F. of L. by the pressure of organized female workers. Female-domination began to emerge in the first two decades of the 20th century, including particularly the International Ladies Garment Workers' Union

The International Ladies' Garment Workers' Union (ILGWU) was a labor union for employees in the women's clothing industry in the United States. It was one of the largest unions in the country, one of the first to have a primarily female membersh ...

. Women organized independent locals among New York hat makers, in the Chicago stockyards, and among Jewish and Italian waist makers, to name only three examples. Through the efforts of middle-class reformers and activists, often of the Women's Trade Union League

The Women's Trade Union League (WTUL) (1903–1950) was a United States, U.S. organization of both working class and more well-off women to support the efforts of women to organize labor unions and to eliminate sweatshop conditions. The WTUL pla ...

, those unions joined the A.F. of L.

Conflicts between affiliated unions

From the beginning, unions affiliated with the A.F. of L. found themselves in conflict when both unions claimed jurisdiction over the same groups of workers: both the Brewers and

From the beginning, unions affiliated with the A.F. of L. found themselves in conflict when both unions claimed jurisdiction over the same groups of workers: both the Brewers and Teamsters

The International Brotherhood of Teamsters (IBT) is a trade union, labor union in the United States and Canada. Formed in 1903 by the merger of the Team Drivers International Union and the Teamsters National Union, the union now represents a di ...

claimed to represent beer truck drivers, both the Machinists and the International Typographical Union

The International Typographical Union (ITU) was a North American trade union for the printing trade of newspapers and other media. It was founded on May 3, 1852, in the United States as the National Typographical Union. It changed its name to the ...

claimed to represent certain printroom employees, and the Machinists and a fledgling union known as the "Carriage, Wagon and Automobile Workers Union" sought to organize the same employees even though neither union had made any effort to organize or bargain for those employees. In some cases, the A.F. of L. mediated the dispute, usually by favoring the larger or more influential union. The A.F. of L. often reversed its jurisdictional rulings over time, as the continuing jurisdictional battles between the Brewers and the Teamsters showed.

Affiliates within the AFL formed "departments" to help resolve these jurisdictional conflicts and to provide a more effective voice for member unions in given industries. The Metal Trades Department engaged in some organizing of its own, primarily in shipbuilding, where unions such as the Pipefitters, Machinists and Iron Workers joined through local metal workers' councils to represent a diverse group of workers. The Railway Employes' Department dealt with both jurisdictional disputes between affiliates and pursued a common legislative agenda for all of them.

Historical achievements

Organizing and coordination

The A.F. of L. made efforts in its early years to assist its affiliates in organizing: it advanced funds or provided organizers or, in some cases, such as theInternational Brotherhood of Electrical Workers

The International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers (IBEW) is a trade union, labor union that represents approximately 820,000 workers and retirees in the electricity, electrical industry in the United States, Canada, Guam, Panama, Puerto Rico, an ...

, the Teamsters

The International Brotherhood of Teamsters (IBT) is a trade union, labor union in the United States and Canada. Formed in 1903 by the merger of the Team Drivers International Union and the Teamsters National Union, the union now represents a di ...

and the American Federation of Musicians

The American Federation of Musicians of the United States and Canada (AFM/AFofM) is a 501(c)(5) trade union, labor union representing professional instrumental musicians in the United States and Canada. The AFM, which has its headquarters in N ...

, helped form the union. The A.F. of L. also used its influence, including refusal of charters or expulsion, to heal splits within affiliated unions, to force separate unions seeking to represent the same or closely related jurisdictions to merge, or to mediate disputes between rival factions where both sides claimed to represent the leadership of an affiliated union. The A.F. of L. also chartered " federal unions", local unions not affiliated with any international union, in those fields in which no affiliate claimed jurisdiction.

The A.F. of L. also encouraged the formation of local labor bodies, known as central labor councils, in major metropolitan areas in which all of the affiliates could participate. Those local labor councils acquired a great deal of influence in some cases. For example, the Chicago Federation of Labor

The Chicago Federation of Labor (CFL) is an umbrella organization for Trade union, unions in Chicago, Illinois, US. It is a subordinate body of the AFL–CIO, and as of 2011 has about 320 affiliated member unions representing half a million union ...

spearheaded efforts to organize packinghouse and steel workers during and immediately after World War I. Local building trades councils also became powerful in some areas. In San Francisco

San Francisco, officially the City and County of San Francisco, is a commercial, Financial District, San Francisco, financial, and Culture of San Francisco, cultural center of Northern California. With a population of 827,526 residents as of ...

, the local Building Trades Council, led by Carpenters official P. H. McCarthy

Patrick Henry McCarthy (March 17, 1863 – July 1, 1933), nicknamed "Pinhead", was an influential labor leader in San Francisco and the 29th Mayor of the City from 1910 to 1912. Born in County Limerick, Ireland, he apprenticed as a carpenter ...

, not only dominated the local labor council but helped elect McCarthy mayor of San Francisco in 1909. In a very few cases early in the A.F. of L.'s history, state and local bodies defied A.F. of L. policy or chose to disaffiliate over policy disputes.

Political action

Though Gompers had contact withsocialists

Socialism is an economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes the economic, political, and socia ...

and such as A.F. of L. co-founder Peter J. McGuire, the A.F. of L. adopted a philosophy of "business unionism" that emphasized unions' contribution to businesses' profits and national economic growth. The business unionist approach also focused on skilled workers' immediate job-related interests, while refusing to "rush to the support of any one of the numerous society-saving or society destroying schemes" involved in larger political issues.

This approach was set by Gompers, who was influenced by a fellow cigar maker (and former socialist) Ferdinand Laurrel. Despite his socialist contacts, Gompers himself was not a socialist.

Cleveland

Cleveland is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Cuyahoga County. Located along the southern shore of Lake Erie, it is situated across the Canada–U.S. maritime border and approximately west of the Ohio-Pennsylvania st ...

administration during the Pullman Strike

The Pullman Strike comprised two interrelated strikes in 1894 that shaped national labor policy in the United States during a period of deep economic depression. First came a strike by the American Railway Union (ARU) against the Pullman Company' ...

in 1894. While the A.F. of L. sought to outlaw "yellow dog contracts

A yellow-dog contract (a yellow-dog clause of a contract, also known as an ironclad oath) is an agreement between an employer and an employee in which the employee agrees, as a condition of employment, not to be a member of a labor union. In the ...

", to limit the courts' power to impose "government by injunction" and to obtain exemption from the antitrust

Competition law is the field of law that promotes or seeks to maintain market competition by regulating anti-competitive conduct by companies. Competition law is implemented through public and private enforcement. It is also known as antitrust l ...

laws that were being used to criminalize labor organizing, the courts reversed what few legislative successes the labor movement won.

The A.F. of L. concentrated its political efforts during the last decades of the Gompers administration on securing freedom from state control of unions—in particular an end to the court's use of labor injunctions to block the right to organize or strike and the application of the anti-trust laws to criminalize labor's use of pickets, boycotts and strikes. The A.F. of L. thought that it had achieved the latter with the passage of the Clayton Antitrust Act

The Clayton Antitrust Act of 1914 (, codified at , ), is a part of United States antitrust law with the goal of adding further substance to the U.S. antitrust law regime; the Clayton Act seeks to prevent anticompetitive practices in their inci ...

in 1914—which Gompers referred to as "Labor's Magna Carta

(Medieval Latin for "Great Charter"), sometimes spelled Magna Charta, is a royal charter of rights agreed to by King John of England at Runnymede, near Windsor, on 15 June 1215. First drafted by the Archbishop of Canterbury, Cardin ...

". But in '' Duplex Printing Press Co. v. Deering'', 254 U.S. 443 (1921), the United States Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that turn on question ...

narrowly read the Act and codified the federal courts' existing power to issue injunctions rather than limit it. The court read the phrase "between an employer and employees" (contained in the first paragraph of the Act) to refer only to cases involving an employer and its own employees, leaving the courts free to punish unions for engaging in sympathy strike

Solidarity action (also known as secondary action, a secondary boycott, a solidarity strike, or a sympathy strike) is industrial action by a trade union in support of a strike initiated by workers in a separate corporation, but often the same en ...

s or secondary boycotts.

The A.F. of L.'s pessimistic attitude towards politics did not, on the other hand, prevent affiliated unions from pursuing their own agendas. Construction unions supported legislation that governed entry of contractors into the industry and protected workers' rights to pay, rail and mass production industries sought workplace safety legislation, and unions generally agitated for the passage of workers' compensation

Workers' compensation or workers' comp is a form of insurance providing wage replacement and medical benefits to employees injured in the course of employment in exchange for mandatory relinquishment of the employee's right to sue his or her emp ...

statutes.

At the same time, the A.F. of L. took efforts on behalf of women in supporting protective legislation. It advocated fewer hours for women workers, and based its arguments on assumptions of female weakness. Like efforts to unionize, most support for protective legislation for women came out of a desire to protect men's jobs. If women's hours could be limited, reasoned A.F. of L. officials, they would infringe less on male employment and earning potential. But the A.F. of L. also took more selfless efforts. Even from the 1890s, the A.F. of L. declared itself vigorously in favor of women's suffrage. It often printed pro-suffrage articles in its periodical, and in 1918, it supported the National Union of Women's Suffrage.

The A.F. of L. relaxed its rigid stand against legislation after the death of Gompers. Even so, it remained cautious. Its proposals for unemployment benefits (made in the late 1920s) were too modest to have practical value, as the Great Depression

The Great Depression was a severe global economic downturn from 1929 to 1939. The period was characterized by high rates of unemployment and poverty, drastic reductions in industrial production and international trade, and widespread bank and ...

soon showed. The impetus for the major federal labor laws of the 1930s came from the New Deal

The New Deal was a series of wide-reaching economic, social, and political reforms enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1938, in response to the Great Depression in the United States, Great Depressi ...

. The enormous growth in union membership came after Congress passed the National Industrial Recovery Act

The National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933 (NIRA) was a US labor law and consumer law passed by the 73rd US Congress to authorize the president to regulate industry for fair wages and prices that would stimulate economic recovery. It als ...

in 1933 and National Labor Relations Act

The National Labor Relations Act of 1935, also known as the Wagner Act, is a foundational statute of United States labor law that guarantees the right of private sector employees to organize into trade unions, engage in collective bargaining, an ...

in 1935. The A.F. of L. refused to sanction or participate in the mass strikes led by John L. Lewis

John Llewellyn Lewis (February 12, 1880 – June 11, 1969) was an American leader of Labor unions in the United States, organized labor who served as president of the United Mine Workers, United Mine Workers of America (UMW) from 1920 to 1960. ...

of the United Mine Workers and other left unions such as the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America

Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America (ACWA) was a United States labor union known for its support for "social unionism" and progressive political causes. Led by Sidney Hillman for its first thirty years, it helped found the Congress of Indus ...

. After the A.F. of L. expelled the CIO in 1936, the CIO undertook a major organizing effort. In 1947, when the Taft-Hartley Act was passed, political activities were stirred. In resistance to the new law, the CIO joined the A.F. of L., and political co-operation set the path for union unity. The two groups merged, eight years later, into the AFL–CIO coalition with George Meany as the new president.

Leadership

Presidents

*Samuel Gompers

Samuel Gompers (; January 27, 1850December 11, 1924) was a British-born American cigar maker, labor union leader and a key figure in American labor history. Gompers founded the American Federation of Labor (AFL) and served as the organization's ...

, 1886–1894

* John McBride, 1894–1895

* Samuel Gompers

Samuel Gompers (; January 27, 1850December 11, 1924) was a British-born American cigar maker, labor union leader and a key figure in American labor history. Gompers founded the American Federation of Labor (AFL) and served as the organization's ...

, 1895–1924

* William Green, 1924–1952

* George Meany

William George Meany (August 16, 1894 – January 10, 1980) was an American labor union administrator for 57 years. He was a vital figure in the creation of the AFL–CIO and served as its first president, from 1955 to 1979.

Meany, the son of a ...

, 1952–1955 (afterwards President of the AFL–CIO)

Secretaries

:1886: Peter J. McGuire :1889: Chris Evans :1894:August McCraith Augustine McCraith (January 19, 1864 – March 26, 1909) was a Canadian labor unionist.

Born on Prince Edward Island, McCraith became a printer and moved to Boston. He was an individualist anarchist, who argued that unions should be politicall ...

:1897: Frank Morrison

:1935: ''Position merged''

Treasurers

:1886:Gabriel Edmonston

Gabriel Edmonston (March 29, 1839 – May 16, 1918) was an American labor unionist and carpenter.

Born in Washington, D.C., Edmonston trained as a carpenter. During the American Civil War, he served in the Confederate Army, in the First Corp ...

:1890: John Brown Lennon

John Brown Lennon (October 12, 1850 - January 17, 1923) was an American labor union leader and general-secretary of the Journeymen Tailors Union of America (JTU). In 1890, he was elected treasurer of the American Federation of Labor and served in ...

:1917: Daniel J. Tobin

:1928: Martin Francis Ryan

:1935: ''Position merged''

Secretary-Treasureres

:1936: Frank Morrison :1939:George Meany

William George Meany (August 16, 1894 – January 10, 1980) was an American labor union administrator for 57 years. He was a vital figure in the creation of the AFL–CIO and served as its first president, from 1955 to 1979.

Meany, the son of a ...

:1952: William F. Schnitzler

Affiliated unions and brotherhoods

: Sources: ''American Labor Year Book, 1926,'' pp. 85–87, 103–172. ''American Labor Press Directory,'' pp. 1–11.State federations

*Pennsylvania Federation of Labor

Pennsylvania, officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a U.S. state, state spanning the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern United States, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes region, Great Lakes regions o ...

*Texas State Federation of Labor

The Texas State Federation of Labor (TSFL) was the Texas affiliate of the American Federation of Labor (AFL). It was formed in 1900 and disbanded in July 1957, when it merged with the Texas State CIO Council to form the Texas AFL-CIO.

History

...

See also

*AFL–CIO

The American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO) is a national trade union center that is the largest federation of unions in the United States. It is made up of 61 national and international unions, together r ...

* Labor history of the United States

The nature and power of organized labor in the United States is the outcome of historical tensions among counter-acting forces involving workplace rights, wages, working hours, political expression, US labor law, labor laws, and other working co ...

* Federation of Organized Trades and Labor Unions

The Federation of Organized Trades and Labor Unions of the United States and Canada (FOTLU) was a federation of labor unions created on November 15, 1881, at Turner Hall in Pittsburgh. It changed its name to the American Federation of Labor (AF ...

* Industrial Workers of the World

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), whose members are nicknamed "Wobblies", is an international labor union founded in Chicago, United States in 1905. The nickname's origin is uncertain. Its ideology combines general unionism with indu ...

* Knights of Labor

The Knights of Labor (K of L), officially the Noble and Holy Order of the Knights of Labor, was the largest American labor movement of the 19th century, claiming for a time nearly one million members. It operated in the United States as well in ...

* Labor federation competition in the United States

Labor federation competition in the United States is a history of the labor movement, considering U.S. labor organizations and federations that have been regional, national, or international in scope, and that have united organizations of disparate ...

* Labor unions in the United States

Labor unions represent United States workers in many industries recognized under US labor law since the 1935 enactment of the National Labor Relations Act. Their activity centers on collective bargaining over wages, benefits, and working cond ...

* Western Federation of Miners

The Western Federation of Miners (WFM) was a labor union that gained a reputation for militancy in the mines of the western United States and British Columbia. Its efforts to organize both hard rock miners and smelter workers brought it into ...

References

Cited and general references and further reading

Primary sources

* American Federation of Labor''Some Reasons for Chinese Exclusion. Meat vs. Rice. American Manhood against Asiatic Coolieism. Which Shall Survive?''

Washington, D.C.: American Federation of Labor, 1901. * Gompers, Samuel

''American Labor and the War''

New York: George H. Doran Co., n.d.

918

__NOTOC__

Year 918 (Roman numerals, CMXVIII) was a common year starting on Thursday of the Julian calendar.

Events

By place

Europe

* December 23 – King Conrad I of Germany, Conrad I, injured at one of his battles with Arnulf, D ...

* Gompers, Samuel''Labor and the Employer''