Farleigh Hungerford Castle on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Farleigh Hungerford Castle, sometimes called Farleigh Castle or Farley Castle, is a

After the

After the  Opposite the entrance, and running across the middle of the court, was the

Opposite the entrance, and running across the middle of the court, was the

Sir Walter Hungerford inherited Farleigh Hungerford castle upon the death of his mother, Joan, in 1412. Walter's first political patron was John of Gaunt's son, Henry IV, and later he became a close companion of Henry's own son,

Sir Walter Hungerford inherited Farleigh Hungerford castle upon the death of his mother, Joan, in 1412. Walter's first political patron was John of Gaunt's son, Henry IV, and later he became a close companion of Henry's own son,  Walter left the castle to his son, Robert Hungerford.Kightly, p.22. Records of the castle at the time show considerable luxuries, including valuable

Walter left the castle to his son, Robert Hungerford.Kightly, p.22. Records of the castle at the time show considerable luxuries, including valuable

Sir Walter Hungerford died in 1516, leaving Farleigh Hungerford Castle to his son, Sir Edward. Edward was a successful member of

Sir Walter Hungerford died in 1516, leaving Farleigh Hungerford Castle to his son, Sir Edward. Edward was a successful member of

On Edward's death in 1648, Anthony Hungerford, his half-brother, inherited the castle. The north chapel was extensively renovated during this period by Edward's widow, Margaret Hungerford, who covered the walls with pictures of

On Edward's death in 1648, Anthony Hungerford, his half-brother, inherited the castle. The north chapel was extensively renovated during this period by Edward's widow, Margaret Hungerford, who covered the walls with pictures of

From the 18th century onwards, Farleigh Hungerford Castle slipped into decline. In 1702, the castle was sold on to Hector Cooper, who lived in

From the 18th century onwards, Farleigh Hungerford Castle slipped into decline. In 1702, the castle was sold on to Hector Cooper, who lived in

Aspects of the Mediaeval Landscape of Somerset and Contributions to the Landscape History of the County.

' Taunton, UK: Somerset County Council. . *Bettey, Joseph. (1998) "From the Norman Conquest to the Reformation", in Aston (ed) (1998). *Bull, Henry. (1859)

A History, Military and Municipal, of the Ancient Borough of Devizes.

' London: Longman. . *Creighton, Oliver Hamilton. (2005)

Castles and Landscapes: Power, Community and Fortification in Medieval England.

' London: Equinox. . *Creighton, Oliver Hamilton and Robert Higham. (2003)

Medieval Castles.

' Princes Risborough, UK: Shire Publications. . *Cruickshanks, Eveline and Stuart Handley (eds) (2002)

The House of Commons: 1690–1715.

' Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. . *Emery, Anthony. (2006)

Greater Medieval Houses of England and Wales, 1300–1500: Southern England.

' Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. . *Given-Wilson, Chris. (1996)

The English Nobility in the Late Middle Ages.

' London: Routledge. . *Gondoin, Stéphane W. (2005)

Châteaux-Forts: Assiéger et Fortifier au Moyen Âge.

' Paris: Cheminements. . *Hall, Hubert. (2003)

Society in the Elizabethan Age.

' Whitefish, US: Kessinger Publishing. . *Hayton, D. W. and Henry Lancaster. (2002) "Sir Edward Hungerford", in Cruickshanks and Handley (eds) (2002). * Jackson, J. E. (1851) "Farleigh Hungerford Castle, Somerset", ''Proceedings of Somerset Archaeology'' 1–3 pp. 114–124. *Kightly, Charles. (2006)

Farleigh Hungerford Castle.

' London: English Heritage. . *Mackenzie, James D. (1896)

The Castles of England: Their Story and Structure, Vol II.

' New York: Macmillan. . *Miles, T. J and A. D. Saunders. (1975) "The Chantry House at Farleigh Hungerford Castle", ''Medieval Archaeology'' 19, pp. 165–94. *Murphy, Ignatius Ingoldsby. (1891)

Life of Colonel Daniel E. Hungerford.

' Hartford, US: Case, Lockwood and Brainard. . *Pettifer, Adrian. (2002)

English Castles: a Guide by Counties

'' Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press. . *Pounds, Norman John Greville. (1994)

The Medieval Castle in England and Wales: a Social and Political History.

' Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. . *Roffey, Simon. (2007)

The Medieval Chantry Chapel: an Archaeology.

' Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press. . *Tarlow, Sarah. (2011)

Ritual, Belief and the Dead in Early Modern Britain and Ireland.

' Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. . *Wade, G. W. and J. H. Wade. (1929)

' London: Methuen. . *Wilcox, Ronald. (1981). "Excavations at Farleigh Hungerford Castle, Somerset, 1973-6", ''Proceedings of Somerset Archaeology'' 124, pp. 87–109.

Farleigh Hungerford Castle on English Heritage

{{Authority control 1383 establishments in England Buildings and structures completed in 1383 14th-century fortifications Grade I listed buildings in Mendip District Buildings and structures in Mendip District Castles in Somerset English Heritage sites in Somerset Scheduled monuments in Mendip District Historic house museums in Somerset Grade I listed castles Ruined castles in England Grade I listed ruins Articles containing video clips George Plantagenet, Duke of Clarence Richard III of England

medieval

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of World history (field), global history. It began with the fall of the West ...

castle

A castle is a type of fortification, fortified structure built during the Middle Ages predominantly by the nobility or royalty and by Military order (monastic society), military orders. Scholars usually consider a ''castle'' to be the private ...

in Farleigh Hungerford

Farleigh Hungerford () is a village and former civil parish, now in the parish of Norton St Philip, in the Somerset (district), Somerset district, in the ceremonial county of Somerset, England, 9 miles southeast of Bath, Somerset, Bath, 3½ mile ...

, Somerset

Somerset ( , ), Archaism, archaically Somersetshire ( , , ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is bordered by the Bristol Channel, Gloucestershire, and Bristol to the north, Wiltshire to the east ...

, England. The castle was built in two phases: the inner court was constructed between 1377 and 1383 by Sir Thomas Hungerford, who made his fortune as steward to John of Gaunt

John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster (6 March 1340 – 3 February 1399), was an English royal prince, military leader and statesman. He was the fourth son (third surviving) of King Edward III of England, and the father of King Henry IV. Because ...

. The castle was built to a quadrangular

Quadrangle or The Quadrangle may refer to:

Architecture

*Quadrangle (architecture), a courtyard surrounded by a building or several buildings, often at a college

Various specific quadrangles, often called "the quad" or "the quadrangle":

North A ...

design, already slightly old-fashioned, on the site of an existing manor house

A manor house was historically the main residence of the lord of the manor. The house formed the administrative centre of a manor in the European feudal system; within its great hall were usually held the lord's manorial courts, communal mea ...

overlooking the River Frome. A deer park was attached to the castle, requiring the destruction of the nearby village. Sir Thomas's son, Sir Walter Hungerford, a knight and leading courtier to Henry V Henry V may refer to:

People

* Henry V, Duke of Bavaria (died 1026)

* Henry V, Holy Roman Emperor (1081/86–1125)

* Henry V, Duke of Carinthia (died 1161)

* Henry V, Count Palatine of the Rhine (–1227)

* Henry V, Count of Luxembourg (1216–1281 ...

, became rich during the Hundred Years War

The Hundred Years' War (; 1337–1453) was a conflict between the kingdoms of England and France and a civil war in France during the Late Middle Ages. It emerged from feudal disputes over the Duchy of Aquitaine and was triggered by a c ...

with France and extended the castle with an additional, outer court, enclosing the parish church in the process. By Walter's death in 1449, the substantial castle was richly appointed, and its chapel

A chapel (from , a diminutive of ''cappa'', meaning "little cape") is a Christianity, Christian place of prayer and worship that is usually relatively small. The term has several meanings. First, smaller spaces inside a church that have their o ...

decorated with mural

A mural is any piece of Graphic arts, graphic artwork that is painted or applied directly to a wall, ceiling or other permanent substrate. Mural techniques include fresco, mosaic, graffiti and marouflage.

Word mural in art

The word ''mural'' ...

s.

The castle largely remained in the hands of the Hungerford family over the next two centuries, despite periods during the War of the Roses

The Wars of the Roses, known at the time and in following centuries as the Civil Wars, were a series of armed confrontations, machinations, battles and campaigns fought over control of the English throne from 1455 to 1487. The conflict was fo ...

in which it was held by the Crown following the attainder

In English criminal law, attainder was the metaphorical "stain" or "corruption of blood" which arose from being condemned for a serious capital crime (felony or treason). It entailed losing not only one's life, property and hereditary titles, but ...

and execution of members of the family. At the outbreak of the English Civil War

The English Civil War or Great Rebellion was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Cavaliers, Royalists and Roundhead, Parliamentarians in the Kingdom of England from 1642 to 1651. Part of the wider 1639 to 1653 Wars of th ...

in 1642, the castle, modernized to the latest Tudor and Stuart

Stuart may refer to:

People

*Stuart (name), a given name and surname (and list of people with the name)

* Clan Stuart of Bute, a Scottish clan

*House of Stuart, a royal house of Scotland and England

Places Australia Generally

*Stuart Highway, ...

fashions, was held by Sir Edward Hungerford. Edward declared his support for Parliament

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

, becoming a leader of the Roundheads

Roundheads were the supporters of the Parliament of England during the English Civil War (1642–1651). Also known as Parliamentarians, they fought against King Charles I of England and his supporters, known as the Cavaliers or Royalists, who ...

in Wiltshire

Wiltshire (; abbreviated to Wilts) is a ceremonial county in South West England. It borders Gloucestershire to the north, Oxfordshire to the north-east, Berkshire to the east, Hampshire to the south-east, Dorset to the south, and Somerset to ...

. Farleigh Hungerford was seized by Royalist

A royalist supports a particular monarch as head of state for a particular kingdom, or of a particular dynastic claim. In the abstract, this position is royalism. It is distinct from monarchism, which advocates a monarchical system of gove ...

forces in 1643, but recaptured by Parliament without a fight near the end of the conflict in 1645. As a result, it escaped slighting

Slighting is the deliberate damage of high-status buildings to reduce their value as military, administrative, or social structures. This destruction of property is sometimes extended to the contents of buildings and the surrounding landscape. It ...

following the war, unlike many other castles in the south-west of England.

The last member of the Hungerford family to hold the castle, Sir Edward Hungerford, inherited it in 1657, but his gambling and extravagance forced him to sell the property in 1686. By the 18th century, the castle was no longer lived in by its owners and fell into disrepair; in 1730 it was bought by the Houlton family, Trowbridge clothiers, when much of it was broken up for salvage. Antiquarian

An antiquarian or antiquary () is an aficionado or student of antiquities or things of the past. More specifically, the term is used for those who study history with particular attention to ancient artefacts, archaeological and historic si ...

and tourist interest in the now ruined castle increased through the 18th and 19th centuries. The castle chapel

Castle chapels () in European architecture are chapels that were built within a castle. They fulfilled the religious requirements of the castle lord and his retinue, while also sometimes serving as a burial site. Because the construction of suc ...

was repaired in 1779 and became a museum of curiosities, complete with the murals rediscovered on its walls in 1844 and a number of rare lead anthropomorphic coffins from the mid-17th century. In 1915 Farleigh Hungerford Castle was sold to the Office of Works

The Office of Works was an organisation responsible for structures and exterior spaces, first established as part of the English royal household in 1378 to oversee the building and maintenance of the royal castles and residences.

In 1832 it be ...

and a controversial restoration programme began. It is now owned by English Heritage

English Heritage (officially the English Heritage Trust) is a charity that manages over 400 historic monuments, buildings and places. These include prehistoric sites, a battlefield, medieval castles, Roman forts, historic industrial sites, Lis ...

, who operate it as a tourist attraction, and the castle is a Grade I listed building

In the United Kingdom, a listed building is a structure of particular architectural or historic interest deserving of special protection. Such buildings are placed on one of the four statutory lists maintained by Historic England in England, Hi ...

and a scheduled monument

In the United Kingdom, a scheduled monument is a nationally important archaeological site or historic building, given protection against unauthorised change.

The various pieces of legislation that legally protect heritage assets from damage, visu ...

.

History

11th – 14th centuries

After the

After the Norman Conquest

The Norman Conquest (or the Conquest) was the 11th-century invasion and occupation of England by an army made up of thousands of Normans, Norman, French people, French, Flemish people, Flemish, and Bretons, Breton troops, all led by the Du ...

of England, the manor of Ferlege in Somerset

Somerset ( , ), Archaism, archaically Somersetshire ( , , ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is bordered by the Bristol Channel, Gloucestershire, and Bristol to the north, Wiltshire to the east ...

was granted by William the Conqueror

William the Conqueror (Bates ''William the Conqueror'' p. 33– 9 September 1087), sometimes called William the Bastard, was the first Norman king of England (as William I), reigning from 1066 until his death. A descendant of Rollo, he was D ...

to Roger de Courcelles. Ferlege evolved from the Anglo-Saxon

The Anglo-Saxons, in some contexts simply called Saxons or the English, were a Cultural identity, cultural group who spoke Old English and inhabited much of what is now England and south-eastern Scotland in the Early Middle Ages. They traced t ...

name ''faern-laega'', meaning "the ferny pasture", and itself later evolved into Farleigh.Kightly, p.17. William Rufus

William II (; – 2 August 1100) was King of England from 26 September 1087 until his death in 1100, with powers over Normandy and influence in Scotland. He was less successful in extending control into Wales. The third son of William the Co ...

gave the manor to Hugh de Montfort, who renamed it Farleigh Montfort. The manor passed from the Montfort family to Bartholomew de Bunghersh in the early years of the reign of Edward III

Edward III (13 November 1312 – 21 June 1377), also known as Edward of Windsor before his accession, was King of England from January 1327 until his death in 1377. He is noted for his military success and for restoring royal authority after t ...

.

Sir Thomas Hungerford bought the property from the Bunghersh family in 1369 for £733.Dunning, pp.57–8. By 1385 the manor was known as Farley Hungerford, after its new owner. Sir Thomas Hungerford was a knight and courtier, who became rich as the Chief Steward to the powerful John of Gaunt

John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster (6 March 1340 – 3 February 1399), was an English royal prince, military leader and statesman. He was the fourth son (third surviving) of King Edward III of England, and the father of King Henry IV. Because ...

and then the first recorded Speaker

Speaker most commonly refers to:

* Speaker, a person who produces speech

* Loudspeaker, a device that produces sound

** Computer speakers

Speaker, Speakers, or The Speaker may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* "Speaker" (song), by David ...

of the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the Bicameralism, bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of ...

. Thomas decided to make Farleigh Hungerford his principal home and, between 1377 and 1383, built a castle on the site; unfortunately he did not acquire the appropriate licence to crenellate

In medieval England, Wales and the Channel Islands a licence to crenellate (or licence to fortify) granted the holder permission to fortify his property. Such licences were granted by the king, and by the rulers of the counties palatine within the ...

from the king before commencing building, and Thomas had to acquire a royal pardon in 1383.

Thomas's new castle adapted the existing manor complex overlooking the head of the River Frome. Although the castle sat on a low spur it was overlooked by higher ground from the west and the north and was not ideally placed from a purely defensive perspective. Contemporary castle designs included the construction of huge, palatial tower keeps and apartments for the most powerful nobles, such as Kenilworth

Kenilworth ( ) is a market town and Civil parishes in England, civil parish in the Warwick (district), Warwick District of Warwickshire, England, southwest of Coventry and north of both Warwick and Leamington Spa. Situated at the centre of t ...

, expanded by Thomas's patron, John of Gaunt; or the construction of smaller, French influenced castles such as that seen at nearby Nunney Castle, built by one of Thomas's fellow ''nouveau riche

; ), new rich, or new money (in contrast to old money; ) is a social class of the rich whose wealth has been acquired within their own generation, rather than by familial inheritance. These people previously had belonged to a lower social cla ...

'' landowners.Emery, p.533. By contrast, Farleigh Hungerford drew on the tradition of quadrangular castle

A quadrangular castle or courtyard castle is a type of castle characterised by ranges of buildings which are integral with the curtain walls, enclosing a central ward or quadrangle, and typically with angle towers. There is no keep and frequent ...

s that had begun in France during the early 13th century, in which the traditional buildings of an unfortified manor were enclosed by a four-sided outer wall and protected with corner towers. The style was well established by the late 14th century, even slightly old fashioned.

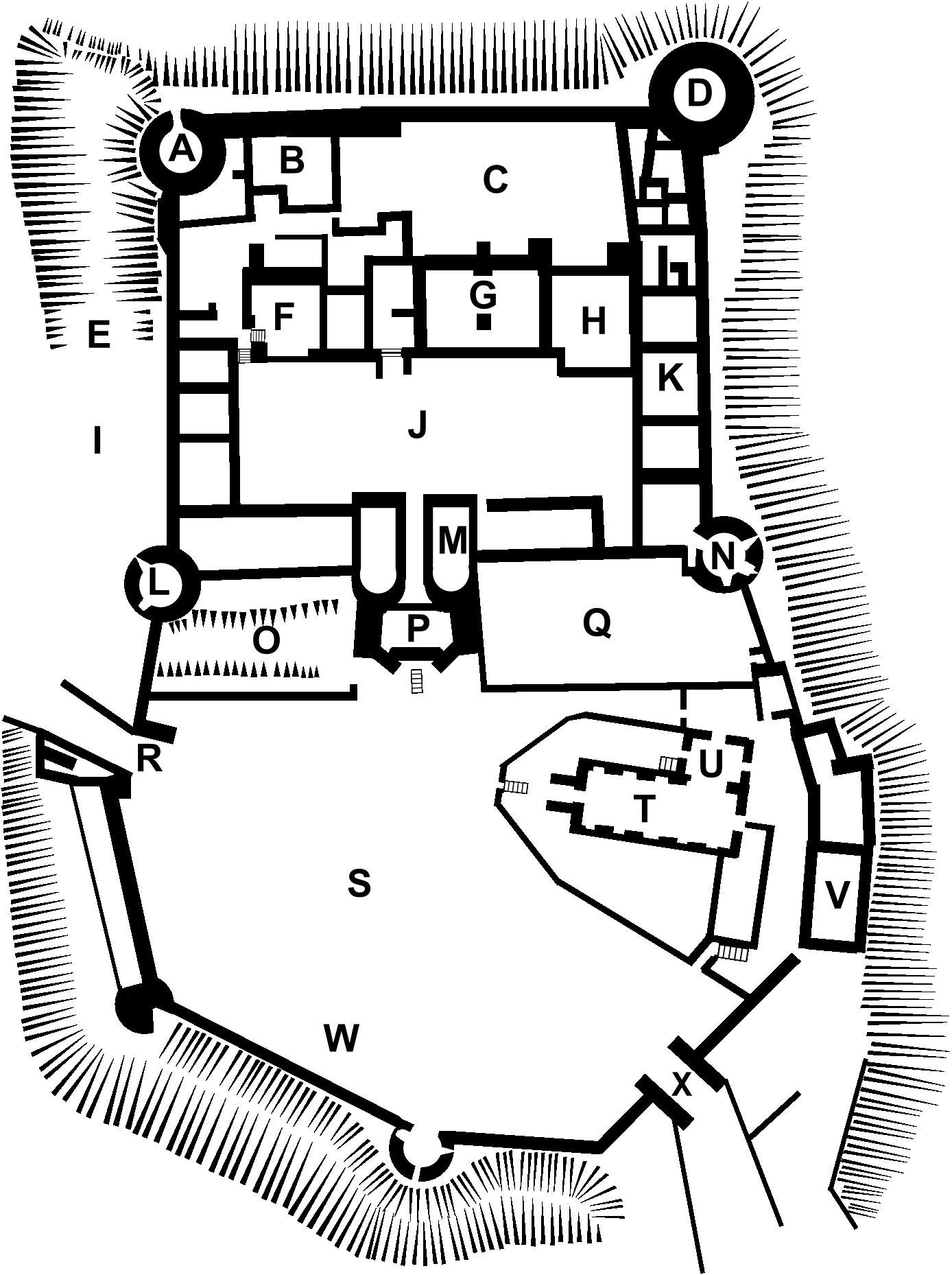

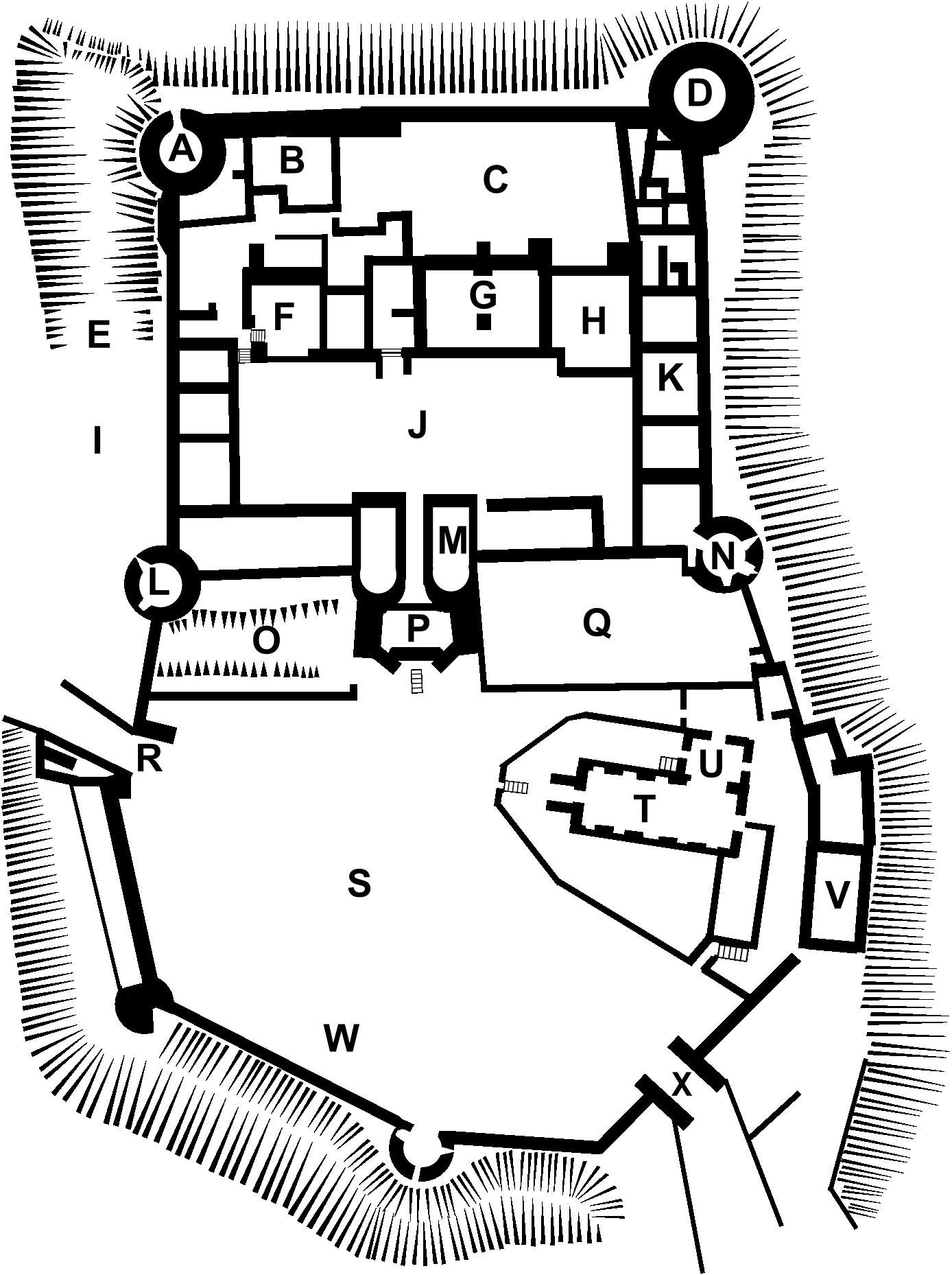

The castle was formed around a court, later called the inner court, enclosed by a curtain wall with a circular tower on each corner and a gatehouse at the front; the north-east tower was larger than the others, perhaps to provide additional defences. Over time the towers acquired their own names: the north-west tower was called the Hazelwell Tower; the north-east the Redcap Tower and the south-west the Lady Tower. The ground fell away sharply on most sides of the castle, but its south and west sides were protected with a wet moat

A moat is a deep, broad ditch dug around a castle, fortification, building, or town, historically to provide it with a preliminary line of defence. Moats can be dry or filled with water. In some places, moats evolved into more extensive water d ...

, using a dam fed from a nearby spring

Spring(s) may refer to:

Common uses

* Spring (season), a season of the year

* Spring (device), a mechanical device that stores energy

* Spring (hydrology), a natural source of water

* Spring (mathematics), a geometric surface in the shape of a he ...

using a pipe. The gatehouse had twin towers and a drawbridge

A drawbridge or draw-bridge is a type of moveable bridge typically at the entrance to a castle or tower surrounded by a moat. In some forms of English, including American English, the word ''drawbridge'' commonly refers to all types of moveable b ...

.Kightly, p.7.

great hall

A great hall is the main room of a royal palace, castle or a large manor house or hall house in the Middle Ages. It continued to be built in the country houses of the 16th and early 17th centuries, although by then the family used the great cha ...

of the castle, with a grand porch

A porch (; , ) is a room or gallery located in front of an entrance to a building. A porch is placed in front of the façade of a building it commands, and forms a low front. Alternatively, it may be a vestibule (architecture), vestibule (a s ...

and steps leading up to the first floor, where prestigious guests would have been entertained amongst carved wall-panels and mural

A mural is any piece of Graphic arts, graphic artwork that is painted or applied directly to a wall, ceiling or other permanent substrate. Mural techniques include fresco, mosaic, graffiti and marouflage.

Word mural in art

The word ''mural'' ...

s. The design of the hall may have emulated Gaunt's hall at Kenilworth; at the very least, it was a powerful symbol of Thomas's authority and status. The west side of the inner court included the castle kitchen, bakery, well and other service facilities; on the east side was the lord's great chamber and a range of other accommodation for other guests. Behind the great hall was a smaller courtyard or garden. Thomas appears to have built up his new castle in stages, with the curtain wall being built first, with the corner towers added afterwards.

A park

A park is an area of natural, semi-natural or planted space set aside for human enjoyment and recreation or for the protection of wildlife or natural habitats. Urban parks are urban green space, green spaces set aside for recreation inside t ...

was established next to the castle; a park was highly prestigious and it enabled Thomas to engage in hunting, provided the castle with a supply of venison

Venison refers primarily to the meat of deer (or antelope in South Africa). Venison can be used to refer to any part of the animal, so long as it is edible, including the internal organs. Venison, much like beef or pork, is categorized into spe ...

as well as generating income. Most of the village of Wittenham had to be destroyed to make way for the park and the site eventually became a deserted village. A new parish church, St Leonard's Chapel, was built by Thomas just outside the castle, after he had demolished the earlier, simpler 12th-century church during the construction of the inner court. Thomas died in 1397 and was buried in the newly built St Anne's Chapel, forming the north transept of St Leonard's Chapel.Kightly, p.13.

15th century

Sir Walter Hungerford inherited Farleigh Hungerford castle upon the death of his mother, Joan, in 1412. Walter's first political patron was John of Gaunt's son, Henry IV, and later he became a close companion of Henry's own son,

Sir Walter Hungerford inherited Farleigh Hungerford castle upon the death of his mother, Joan, in 1412. Walter's first political patron was John of Gaunt's son, Henry IV, and later he became a close companion of Henry's own son, Henry V Henry V may refer to:

People

* Henry V, Duke of Bavaria (died 1026)

* Henry V, Holy Roman Emperor (1081/86–1125)

* Henry V, Duke of Carinthia (died 1161)

* Henry V, Count Palatine of the Rhine (–1227)

* Henry V, Count of Luxembourg (1216–1281 ...

; Henry V made Walter, like his father before him, the Speaker of the Commons in 1414.Kightly, p.18. Walter prospered: he became known as an expert jouster, in 1415 fought at the battle of Agincourt

The Battle of Agincourt ( ; ) was an English victory in the Hundred Years' War. It took place on 25 October 1415 (Saint Crispin's Day) near Azincourt, in northern France. The unexpected victory of the vastly outnumbered English troops agains ...

during the Hundred Years War

The Hundred Years' War (; 1337–1453) was a conflict between the kingdoms of England and France and a civil war in France during the Late Middle Ages. It emerged from feudal disputes over the Duchy of Aquitaine and was triggered by a c ...

, was made Steward of the Royal Household

The Lord Steward or Lord Steward of the Household is one of the three Great Officers of the Household of the British monarch. He is, by tradition, the first great officer of the Court and he takes precedence over all other officers of the househ ...

and was a major figure in government during the 1420s, serving as the Treasurer of England

The Lord High Treasurer was an English government position and has been a British government position since the Acts of Union of 1707. A holder of the post would be the third-highest-ranked Great Officer of State in England, below the Lord Hig ...

and as one of the legal guardians of the young Henry VI. Despite having to pay a ransom of £3,000 to the French after his son was captured in 1429, Walter, by now created Baron Hungerford

Baron Hungerford is a title in the Peerage of England. It was created on 7 January 1426 for Walter Hungerford, who was summoned to parliament, had been Member of Parliament, Speaker of the House and invested as Knight of the Order of the Garter ...

, amassed considerable wealth from his various sources of income, which included the right to one hundred marks

Marks may refer to:

Business

* Mark's, a Canadian retail chain

* Marks & Spencer, a British retail chain

* Collective trade marks

A collective trademark, collective trade mark, or collective mark is a trademark owned by an organization (such ...

(£66) per year from the town of Marlborough

Marlborough or the Marlborough may refer to:

Places Australia

* Marlborough, Queensland

* Principality of Marlborough, a short-lived micronation in 1993

* Marlborough Highway, Tasmania; Malborough was an historic name for the place at the sou ...

, the wool taxes from Wells, and the ransoms gained from the taking of French prisoners. As a result, he was able to buy more land, acquiring around 110 new manors and estates over the course of his life.

Between 1430 and 1445 Walter expanded the castle considerably. An outer court was built to the south side of the original castle, with its own towers and an additional gatehouse which formed the new entrance to the castle. These new defences were less strong than those of the original inner court, and indeed the eastern gatehouse was not crenellated

A battlement, in defensive architecture, such as that of city walls or castles, comprises a parapet (a defensive low wall between chest-height and head-height), in which gaps or indentations, which are often rectangular, occur at intervals ...

at the time. A barbican

A barbican (from ) is a fortified outpost or fortified gateway, such as at an outer defense perimeter of a city or castle, or any tower situated over a gate or bridge which was used for defensive purposes.

Europe

Medieval Europeans typically b ...

was built, extending the older gatehouse to the inner court. The new court enclosed the parish church

A parish church (or parochial church) in Christianity is the Church (building), church which acts as the religious centre of a parish. In many parts of the world, especially in rural areas, the parish church may play a significant role in com ...

, which became the castle chapel, with a replacement church being built by Walter in the village. Walter had the chapel decorated with a number of murals, depicting scenes from the story of Saint George and the Dragon

In a legend, Saint Georgea soldier venerated in Christianity—defeats a dragon. The story goes that the dragon originally extorted tribute from villagers. When they ran out of livestock and trinkets for the dragon, they started giving up a huma ...

; Saint George was a favoured saint of Henry V, and associated with the prestigious Order of the Garter

The Most Noble Order of the Garter is an order of chivalry founded by Edward III of England in 1348. The most senior order of knighthood in the Orders, decorations, and medals of the United Kingdom, British honours system, it is outranked in ...

, of which Walter was a proud member. A house was built next to the chapel for the use of the chantry

A chantry is an ecclesiastical term that may have either of two related meanings:

# a chantry service, a set of Christian liturgical celebrations for the dead (made up of the Requiem Mass and the Office of the Dead), or

# a chantry chapel, a b ...

priest.Kightly, p.15. Walter also legally combined the two parishes of Farleigh in Somerset and Wittenham in Wiltshire

Wiltshire (; abbreviated to Wilts) is a ceremonial county in South West England. It borders Gloucestershire to the north, Oxfordshire to the north-east, Berkshire to the east, Hampshire to the south-east, Dorset to the south, and Somerset to ...

, which formed part of his castle's park, altering the county boundaries of Somerset and Wiltshire in the process. As a village, Wittenham disappeared completely.

Walter left the castle to his son, Robert Hungerford.Kightly, p.22. Records of the castle at the time show considerable luxuries, including valuable

Walter left the castle to his son, Robert Hungerford.Kightly, p.22. Records of the castle at the time show considerable luxuries, including valuable tapestries

Tapestry is a form of textile art which was traditionally woven by hand on a loom. Normally it is used to create images rather than patterns. Tapestry is relatively fragile, and difficult to make, so most historical pieces are intended to han ...

up to long, silk

Silk is a natural fiber, natural protein fiber, some forms of which can be weaving, woven into textiles. The protein fiber of silk is composed mainly of fibroin and is most commonly produced by certain insect larvae to form cocoon (silk), c ...

bedclothes, rich fur

A fur is a soft, thick growth of hair that covers the skin of almost all mammals. It consists of a combination of oily guard hair on top and thick underfur beneath. The guard hair keeps moisture from reaching the skin; the underfur acts as an ...

s and silver

Silver is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol Ag () and atomic number 47. A soft, whitish-gray, lustrous transition metal, it exhibits the highest electrical conductivity, thermal conductivity, and reflectivity of any metal. ...

bowls and utensils. Unfortunately, Robert's eldest son, the later Lord Moleyns, was captured by the French at the battle of Castillon

The Battle of Castillon was a battle between the forces of England and France which took place on 17 July 1453 in Gascony near the town of Castillon-sur-Dordogne (later Castillon-la-Bataille).

On the day of the battle, the English commande ...

, which was fought at the end of the Hundred Years War in 1453. The huge ransom of over £10,000 required to ensure his release financially crippled the family, and Lord Moleyns did not return to England until 1459. By this time England had entered the period of civil conflict between the Houses of York

York is a cathedral city in North Yorkshire, England, with Roman Britain, Roman origins, sited at the confluence of the rivers River Ouse, Yorkshire, Ouse and River Foss, Foss. It has many historic buildings and other structures, such as a Yor ...

and Lancaster

Lancaster may refer to:

Lands and titles

*The County Palatine of Lancaster, a synonym for Lancashire

*Duchy of Lancaster, one of only two British royal duchies

*Duke of Lancaster

*Earl of Lancaster

*House of Lancaster, a British royal dynasty

...

known as the Wars of the Roses

The Wars of the Roses, known at the time and in following centuries as the Civil Wars, were a series of armed confrontations, machinations, battles and campaigns fought over control of the English throne from 1455 to 1487. The conflict was fo ...

. Moleyns was a Lancastrian supporter and fought against the Yorkists in 1460 and 1461, leading to first his exile and then his attainder

In English criminal law, attainder was the metaphorical "stain" or "corruption of blood" which arose from being condemned for a serious capital crime (felony or treason). It entailed losing not only one's life, property and hereditary titles, but ...

, under which Farleigh Hungerford Castle was seized by the Crown. Moleyns was captured and executed in 1464, and his eldest son, Thomas

Thomas may refer to:

People

* List of people with given name Thomas

* Thomas (name)

* Thomas (surname)

* Saint Thomas (disambiguation)

* Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) Italian Dominican friar, philosopher, and Doctor of the Church

* Thomas the A ...

, met the same fate in 1469.

The Yorkist Edward IV

Edward IV (28 April 1442 – 9 April 1483) was King of England from 4 March 1461 to 3 October 1470, then again from 11 April 1471 until his death in 1483. He was a central figure in the Wars of the Roses, a series of civil wars in England ...

gave Farleigh Hungerford Castle to his brother Richard

Richard is a male given name. It originates, via Old French, from compound of the words descending from Proto-Germanic language">Proto-Germanic ''*rīk-'' 'ruler, leader, king' and ''*hardu-'' 'strong, brave, hardy', and it therefore means 'st ...

, then Duke of Gloucester

Duke of Gloucester ( ) is a British royal title (after Gloucester), often conferred on one of the sons of the reigning monarch. The first four creations were in the Peerage of England and the last in the Peerage of the United Kingdom; the curre ...

, in 1462. Edward and Richard's brother George Plantagenet may have taken up residence at the castle; his daughter Margaret

Margaret is a feminine given name, which means "pearl". It is of Latin origin, via Ancient Greek and ultimately from Iranian languages, Old Iranian. It has been an English language, English name since the 11th century, and remained popular thro ...

was certainly born there. Richard became king in 1483 and gave the castle to John Howard

John Winston Howard (born 26 July 1939) is an Australian former politician who served as the 25th prime minister of Australia from 1996 to 2007. He held office as leader of the Liberal Party of Australia. His eleven-year tenure as prime min ...

, the Duke of Norfolk

Duke of Norfolk is a title in the peerage of England. The premier non-royal peer, the Duke of Norfolk is additionally the premier duke and earl in the English peerage. The seat of the Duke of Norfolk is Arundel Castle in Sussex, although the t ...

. Meanwhile, the late Robert's youngest son, Sir Walter, had become a close supporter of Edward IV; nonetheless, he joined the failed revolt of 1483 against Richard and ended up detained in the Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic citadel and castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London, England. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamle ...

. When Henry Tudor invaded England in 1485, Walter escaped custody and joined the invading Lancastrian army, fighting alongside Henry at the Battle of Bosworth

The Battle of Bosworth or Bosworth Field ( ) was the last significant battle of the Wars of the Roses, the civil war between the houses of Lancaster and York that extended across England in the latter half of the 15th century. Fought on 22 ...

.Kightly, p.23. Victorious, the newly crowned Henry VII returned Farleigh Hungerford to Walter in 1486.

16th century

Sir Walter Hungerford died in 1516, leaving Farleigh Hungerford Castle to his son, Sir Edward. Edward was a successful member of

Sir Walter Hungerford died in 1516, leaving Farleigh Hungerford Castle to his son, Sir Edward. Edward was a successful member of Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is known for his Wives of Henry VIII, six marriages and his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. ...

's court and died in 1522, leaving the castle to his second wife, Agnes Hungerford, Lady Hungerford. After Edward's death, however, it emerged that Agnes had been responsible for the murder of her former, first husband, John Cotell: two of her servants had strangled him at Farleigh Hungerford Castle, before burning his body in the castle oven to destroy any evidence. Agnes appears to have been motivated by a desire for the wealth that would follow her second marriage to Sir Edward, but in 1523 Agnes and the two servants were hanged for murder in London.

Due to this execution, Edward's son, another Walter

Walter may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Walter (name), including a list of people and fictional and mythical characters with the given name or surname

* Little Walter, American blues harmonica player Marion Walter Jacobs (1930–19 ...

, inherited the castle instead of Agnes. Walter became a political client of Thomas Cromwell

Thomas Cromwell (; – 28 July 1540) was an English statesman and lawyer who served as List of English chief ministers, chief minister to King Henry VIII from 1534 to 1540, when he was beheaded on orders of the king, who later blamed false cha ...

, the powerful chief minister of Henry VIII, and operated on his behalf in the local region. Walter became dissatisfied with his third wife, Elizabeth, after her father became a political liability to him, and Walter detained her in one of the castle towers for several years. Elizabeth complained that while she was imprisoned she was starved in an attempt to kill her, and subjected to several poisoning attempts.Kightly, p.24. She was probably kept in the north-west tower, although the south-west "Lady Tower" is named after her. When Cromwell fell from power in 1540, so did Walter, who was executed for treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state (polity), state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to Coup d'état, overthrow its government, spy ...

, witchcraft

Witchcraft is the use of Magic (supernatural), magic by a person called a witch. Traditionally, "witchcraft" means the use of magic to inflict supernatural harm or misfortune on others, and this remains the most common and widespread meanin ...

and homosexuality

Homosexuality is romantic attraction, sexual attraction, or Human sexual activity, sexual behavior between people of the same sex or gender. As a sexual orientation, homosexuality is "an enduring pattern of emotional, romantic, and/or sexu ...

: Elizabeth was allowed to remarry, but the castle reverted to the Crown.

Walter's son, also called Walter

Walter may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Walter (name), including a list of people and fictional and mythical characters with the given name or surname

* Little Walter, American blues harmonica player Marion Walter Jacobs (1930–19 ...

, bought back the castle from the Crown in 1554 for £5,000.Kightly, p.25. Farleigh Hungerford Castle and the surrounding park remained in good condition — indeed, unusually for the time, the visiting antiquarian

An antiquarian or antiquary () is an aficionado or student of antiquities or things of the past. More specifically, the term is used for those who study history with particular attention to ancient artefacts, archaeological and historic si ...

John Leland was able to praise its "praty" (pretty) and "stately" condition — but Walter continued to update the property, including adding more fashionable, Elizabethan style windows and improving the east range of the inner court, which became the main living area for the family. Walter's second wife, Jane, was a Roman Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics worldwide as of 2025. It is among the world's oldest and largest international institut ...

and during the turbulent religious politics of the later Tudor period, their marriage collapsed, with Jane going into exile. Walter and Jane's only son died young and, after the Walter's death in 1596, the castle passed to his brother, Sir Edward.Kightly, p.26.

17th century

Sir Edward Hungerford died in 1607, leaving Farleigh Hungerford to his great-nephew, another Sir Edward Hungerford. Edward continued to develop the castle, installing new windows in the medieval buildings of the inner court. In 1642, however, theCivil War

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

broke out in England between the supporters of King Charles

King Charles may refer to:

Kings

A number of kings of Albania, Alençon, Anjou, Austria, Bohemia, Croatia, England, France, Holy Roman Empire, Hungary, Ireland, Jerusalem, Naples, Navarre, Norway, Portugal, Romania, Sardinia, Scotland, Sicily, S ...

and those of Parliament

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

. As a reformist Member of Parliament and a Puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to rid the Church of England of what they considered to be Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should b ...

, Edward was an active supporter of Parliament and volunteered himself as the leader of its forces in the neighbouring county of Wiltshire

Wiltshire (; abbreviated to Wilts) is a ceremonial county in South West England. It borders Gloucestershire to the north, Oxfordshire to the north-east, Berkshire to the east, Hampshire to the south-east, Dorset to the south, and Somerset to ...

; unfortunately this put him at odds with Sir Edward Bayntun, a Wiltshire gentleman with similar ambitions. The resulting feud between the two men turned violent before Parliament finally settled the issue by appointing Hungerford as its commander in Wiltshire at the start of 1643. His military record during the conflict was unexceptional: he abandoned several towns to advancing Royalist armies and fought on the losing side at the battle of Roundway Down

The Battle of Roundway Down was fought on 13 July 1643 at Roundway Down near Devizes, in Wiltshire during the First English Civil War. Despite being outnumbered and exhausted after riding overnight from Oxford, a Royalist cavalry force under ...

, although he did successfully seize Wardour Castle

Wardour Castle or Old Wardour Castle is a ruined 14th-century castle at Wardour, on the boundaries of the civil parishes of Tisbury and Donhead St Andrew in the English county of Wiltshire, about west of Salisbury. The castle was built in t ...

in 1643.

Farleigh Hungerford Castle was captured by a Royalist unit in 1643, following a successful campaign by the King's forces across the south-west. The castle was taken without a fight by Colonel John Hungerford, a half-brother of Edward, who installed a garrison that then supported itself by pillaging the surrounding countryside.Kightly, p.27. Several Parliamentary raids against Farleigh Hungerford were undertaken during 1644, but they failed to take back the castle. By 1645, however, the Royalist cause was close to military collapse; Parliamentary forces began to mop up the remaining Royalist garrisons in the south-west, and on 15 September they reached the castle. Colonel Hungerford immediately surrendered on good terms, and Sir Edward Hungerford peacefully reinstalled himself in the undamaged castle. As a result of this process, the castle escaped being slighted

Slighting is the deliberate damage of high-status buildings to reduce their value as military, administrative, or social structures. This destruction of property is sometimes extended to the contents of buildings and the surrounding landscape. It ...

, or deliberately destroyed, by Parliament, unlike many other castles in the region, such as Nunney.

On Edward's death in 1648, Anthony Hungerford, his half-brother, inherited the castle. The north chapel was extensively renovated during this period by Edward's widow, Margaret Hungerford, who covered the walls with pictures of

On Edward's death in 1648, Anthony Hungerford, his half-brother, inherited the castle. The north chapel was extensively renovated during this period by Edward's widow, Margaret Hungerford, who covered the walls with pictures of saint

In Christianity, Christian belief, a saint is a person who is recognized as having an exceptional degree of sanctification in Christianity, holiness, imitation of God, likeness, or closeness to God in Christianity, God. However, the use of the ...

s, cherub

A cherub (; : cherubim; ''kərūḇ'', pl. ''kərūḇīm'') is one type of supernatural being in the Abrahamic religions. The numerous depictions of cherubim assign to them many different roles, such as protecting the entrance of the Garden of ...

s, clouds, ribbons, crowns and heraldry

Heraldry is a discipline relating to the design, display and study of armorial bearings (known as armory), as well as related disciplines, such as vexillology, together with the study of ceremony, Imperial, royal and noble ranks, rank and genealo ...

, as part of an elaborate tomb for her and Edward which cost £1,100 (£136,000 in 2009 terms). The renovation effectively blocked most of the access into the north chapel, making the new tomb the focus of attention for any visitor or religious activity. A number of lead

Lead () is a chemical element; it has Chemical symbol, symbol Pb (from Latin ) and atomic number 82. It is a Heavy metal (elements), heavy metal that is density, denser than most common materials. Lead is Mohs scale, soft and Ductility, malleabl ...

, anthropomorphic coffin

A coffin or casket is a funerary box used for viewing or keeping a corpse, for burial, entombment or cremation. Coffins are sometimes referred to as caskets, particularly in American English.

A distinction is commonly drawn between "coffins" a ...

s, some with moulded faces or death masks, were laid down in the crypt in the mid- to late-17th century. Four men, two women and two children were embalmed in the castle in this way, probably including Edward and Margaret, as well as the final Sir Edward Hungerford, his wife, son and daughter-in-law. Such lead coffins were extremely expensive during the period and reserved for the wealthiest in society.Tarlow, p.33. Originally the lead coffins would have been encased in wood, but this outer casing has since been lost.

Anthony passed on both the castle and a considerable fortune to his son, yet another Sir Edward Hungerford, in 1657. After his marriage, Edward enjoyed an income of around £8,000 (£1,110,000) a year, making him a very wealthy man.Hayton and Lancaster, p.437. Edward lived a lavish lifestyle, however, including giving a huge gift of money to the exiled Charles II shortly before his restoration to the throne, and later entertaining the royal court at Farleigh Hungerford Castle in 1673.Kightly, p.28. Edward later fell out with the king over the proposal that the Roman Catholic James II should succeed to the throne on Charles's death, and after the discovery of the Rye House Plot

The Rye House Plot of 1683 was a plan to assassinate King Charles II of England and his brother (and heir to the throne) James, Duke of York. The royal party went from Westminster to Newmarket to see horse races and were expected to make the r ...

in 1683 the castle was searched by royal officials looking for stocks of weapons that might be used in a possible revolt.

Meanwhile, Edward had been living a truly extravagant lifestyle, including extensive gambling

Gambling (also known as betting or gaming) is the wagering of something of Value (economics), value ("the stakes") on a Event (probability theory), random event with the intent of winning something else of value, where instances of strategy (ga ...

, resulting in his running up debts of some £40,000, which in 1683 forced him to sell many of his estates in Wiltshire. Over the next two years, Edward incurred further debts of around £38,000 (£5,270,000) and in 1686 was finally forced to sell his remaining lands in the south-west, including Farleigh Hungerford Castle, to Sir Henry Bayntun, who purchased them for £56,000 (£7,750,000).Kightly, p.29. Bayntun lived in the castle for a few years, until his death in 1691.

18th – 20th centuries

From the 18th century onwards, Farleigh Hungerford Castle slipped into decline. In 1702, the castle was sold on to Hector Cooper, who lived in

From the 18th century onwards, Farleigh Hungerford Castle slipped into decline. In 1702, the castle was sold on to Hector Cooper, who lived in Trowbridge

Trowbridge ( ) is the county town of Wiltshire, England; situated on the River Biss in the west of the county, close to the border with Somerset. The town lies south-east of Bath, Somerset, Bath, south-west of Swindon and south-east of Brist ...

; in 1730 it was passed in turn to the Houlton family, who had purchased the estates surrounding the castle.Jackson, pp.123–4. The Houlton family broke up castle's stone walls and the internal contents for salvage. Some of the parts, such as the marble floors, were reused at Longleat

Longleat is a stately home about west of Warminster in Wiltshire, England. A leading and early example of the Elizabethan prodigy house, it is a Grade I listed building and the seat of the Marquesses of Bath.

Longleat is set in of parkl ...

or in the Houlton's new house, Farleigh House

Farleigh House, or Farleigh Castle, sometimes called Farleigh New Castle, is a large English country house in the county of Somerset, formerly the centre of the Farleigh Hungerford estate. Much of the stone to build it came from the nearby Farlei ...

, built nearby in the 1730s; other elements were reused by local villagers. By the end of the 1730s the castle was ruinous and, although the castle chapel was repaired and brought back into use in 1779, the north-west and north-east towers had both collapsed by the end of 1797.Kightly, p.30. The outer court became a farm yard, with the priest's house becoming the farm house. The castle's park was reassigned to serve Farleigh House instead.

Antiquarian curiosity in the castle had begun as early as 1700, when Peter Le Neve

Peter Le Neve (21 January 1661 – 24 September 1729) was an English herald and antiquary. He was appointed Rouge Dragon Pursuivant 17 January 1690 and created Norroy King at Arms on 25 May 1704. From 1707 to 1721 he was Richmond Herald of ...

visited and recorded some of the architectural details, but interest increased in the 19th century.Jackson, p.117. This was partially due to the work of the local curate

A curate () is a person who is invested with the ''care'' or ''cure'' () of souls of a parish. In this sense, ''curate'' means a parish priest; but in English-speaking countries the term ''curate'' is commonly used to describe clergy who are as ...

, the Reverend J. Jackson, who undertook the first archaeological excavations at the site during the 1840s, uncovering many of the foundations of the inner court. 17th and 18th century stained glass

Stained glass refers to coloured glass as a material or art and architectural works created from it. Although it is traditionally made in flat panels and used as windows, the creations of modern stained glass artists also include three-dimensio ...

windows from the continent were installed in the chapel, where the 15th century wall paintings were rediscovered in 1844. The then owner, Colonel John Houlton, turned the chapel into a museum of curiosities, where for a small fee visitors could see sets of armour, what was said to be a pair of Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English statesman, politician and soldier, widely regarded as one of the most important figures in British history. He came to prominence during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, initially ...

's boots and other English Civil War artefacts, including letters from Cromwell written to the Hungerfords.

The foundations that Jackson discovered during the excavations were left exposed for the benefit of visitors and larger numbers of tourists began to come to the castle to see the ruins, including Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte in 1846.Kightly, p.31. The lead coffins in the chapel crypt were popular with tourists, although the coffins were extensively damaged by those visitors keen to see the contents inside. The south-west tower, completely covered by thick ivy

''Hedera'', commonly called ivy (plural ivies), is a genus of 12–15 species of evergreen climbing or ground-creeping woody plants in the family Araliaceae, native to Western Europe, Central Europe, Southern Europe, Macaronesia, northwestern ...

, collapsed in 1842, after local children accidentally set fire to the vegetation that was, by then, holding the tower together. Battlements

A battlement, in defensive architecture, such as that of city walls or castles, comprises a parapet (a defensive low wall between chest-height and head-height), in which gaps or indentations, which are often rectangular, occur at intervals t ...

were added to the east gatehouse during this period, transforming the appearance of its original gable

A gable is the generally triangular portion of a wall between the edges of intersecting roof pitches. The shape of the gable and how it is detailed depends on the structural system used, which reflects climate, material availability, and aesth ...

d roof.Kightly, p.11.

In 1891, most of Farleigh Hungerford Castle was sold by the Houlton family to Lord Donington, whose heir in turn sold it onto Lord Cairns

Hugh McCalmont Cairns, 1st Earl Cairns (27 December 1819 – 2 April 1885) was an Anglo-Irish statesman who served as Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain during the first two ministries of Benjamin Disraeli. He was one of the most prominent ...

in 1907. Cairns passed the castle to the Office of Works

The Office of Works was an organisation responsible for structures and exterior spaces, first established as part of the English royal household in 1378 to oversee the building and maintenance of the royal castles and residences.

In 1832 it be ...

in 1915, by which time it was almost all heavily overgrown with ivy.Kightly, p.31; Miles and Saunders, p.167. The Office of Works began a process of controversial restoration work, removing the ivy and repairing the stone work; the result was critiqued by H. Avray Tipping at the time as "giving the whole castle the effect of a new concrete building". Further excavations took place in 1924 as part of the project, which retained the castle as a tourist attraction. The last inhabitants of the farmhouse left in 1959, when the last parts of the outer court were sold to the government and restored. Attempts were made to preserve the wall paintings in the chapel during 1931 and 1955, but the treatments, which involved the use of red wax

Waxes are a diverse class of organic compounds that are lipophilic, malleable solids near ambient temperatures. They include higher alkanes and lipids, typically with melting points above about 40 °C (104 °F), melting to give lo ...

, stained the paintings and caused considerable damage: the wax was removed in the 1970s. Further excavations followed around the chapel and the priest's house in 1962 and 1968. English Heritage

English Heritage (officially the English Heritage Trust) is a charity that manages over 400 historic monuments, buildings and places. These include prehistoric sites, a battlefield, medieval castles, Roman forts, historic industrial sites, Lis ...

took over responsibility for running the castle in 1983.

21st century

Today, most of Farleigh Hungerford Castle is ruined. In the inner court only the exposed foundations remain of most of the castle buildings, along with the shells of the south-west and south-east towers.Pettifer, p.221. Unusually for English castles, the outer court has survived better than the inner. The restored eastern gatehouse is carved with the badge of the Hungerfords and the initials of the first Sir Edward Hungerford, who had them carved there between 1516 and 1522. The priest's house remains intact, measuring by with two rooms on the ground floor and four rooms above. In Saint Leonard's Chapel, the outlines of many of the medieval murals can still be made out, with the painting of Saint George and Dragon still in particularly good condition; historian Simon Roffey describes this work, one of only four such surviving works in England, as "remarkable". The late 17th century tombs of the Hungerfords remain intact in the north transept chapel dedicated to Saint Anne. The surviving lead anthropomorphic coffins in thecrypt

A crypt (from Greek κρύπτη (kryptē) ''wikt:crypta#Latin, crypta'' "Burial vault (tomb), vault") is a stone chamber beneath the floor of a church or other building. It typically contains coffins, Sarcophagus, sarcophagi, or Relic, religiou ...

are archaeologically significant: although numerous in the late 16th and 17th centuries, few lead coffins survive today, and the chapel has what historian Charles Kightly considers "the best collection" in the country.

The castle site is run by English Heritage as a tourist attraction

A tourist attraction is a place of interest that tourists visit, typically for its inherent or exhibited natural or cultural value, historical significance, natural or built beauty, offering leisure and amusement.

Types

Places of natural beaut ...

. It is a Scheduled Monument

In the United Kingdom, a scheduled monument is a nationally important archaeological site or historic building, given protection against unauthorised change.

The various pieces of legislation that legally protect heritage assets from damage, visu ...

, and the castle and chapel are Grade I listed building

In the United Kingdom, a listed building is a structure of particular architectural or historic interest deserving of special protection. Such buildings are placed on one of the four statutory lists maintained by Historic England in England, Hi ...

s.

See also

*Castles in Great Britain and Ireland

Castles have played an important military, economic and social role in Great Britain and Ireland since their introduction following the Norman invasion of England in 1066. Although a small number of castles had been built in England in the 105 ...

* List of castles in England

This list of castles in England is not a list of every building and site that has "castle" as part of its name, nor does it list only buildings that conform to a strict definition of a castle as a medieval fortified residence. It is not a list ...

* List of castles in Somerset

* Grade I listed buildings in Mendip

Mendip is a former local government district in the English county of Somerset. The Mendip district covers a largely rural area of ranging from the Mendip Hills through on to the Somerset Levels. It has a population of approximately 11,000. The ...

Notes

References

Bibliography

*Aston, M. (ed) (1998)Aspects of the Mediaeval Landscape of Somerset and Contributions to the Landscape History of the County.

' Taunton, UK: Somerset County Council. . *Bettey, Joseph. (1998) "From the Norman Conquest to the Reformation", in Aston (ed) (1998). *Bull, Henry. (1859)

A History, Military and Municipal, of the Ancient Borough of Devizes.

' London: Longman. . *Creighton, Oliver Hamilton. (2005)

Castles and Landscapes: Power, Community and Fortification in Medieval England.

' London: Equinox. . *Creighton, Oliver Hamilton and Robert Higham. (2003)

Medieval Castles.

' Princes Risborough, UK: Shire Publications. . *Cruickshanks, Eveline and Stuart Handley (eds) (2002)

The House of Commons: 1690–1715.

' Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. . *Emery, Anthony. (2006)

Greater Medieval Houses of England and Wales, 1300–1500: Southern England.

' Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. . *Given-Wilson, Chris. (1996)

The English Nobility in the Late Middle Ages.

' London: Routledge. . *Gondoin, Stéphane W. (2005)

Châteaux-Forts: Assiéger et Fortifier au Moyen Âge.

' Paris: Cheminements. . *Hall, Hubert. (2003)

Society in the Elizabethan Age.

' Whitefish, US: Kessinger Publishing. . *Hayton, D. W. and Henry Lancaster. (2002) "Sir Edward Hungerford", in Cruickshanks and Handley (eds) (2002). * Jackson, J. E. (1851) "Farleigh Hungerford Castle, Somerset", ''Proceedings of Somerset Archaeology'' 1–3 pp. 114–124. *Kightly, Charles. (2006)

Farleigh Hungerford Castle.

' London: English Heritage. . *Mackenzie, James D. (1896)

The Castles of England: Their Story and Structure, Vol II.

' New York: Macmillan. . *Miles, T. J and A. D. Saunders. (1975) "The Chantry House at Farleigh Hungerford Castle", ''Medieval Archaeology'' 19, pp. 165–94. *Murphy, Ignatius Ingoldsby. (1891)

Life of Colonel Daniel E. Hungerford.

' Hartford, US: Case, Lockwood and Brainard. . *Pettifer, Adrian. (2002)

English Castles: a Guide by Counties

'' Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press. . *Pounds, Norman John Greville. (1994)

The Medieval Castle in England and Wales: a Social and Political History.

' Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. . *Roffey, Simon. (2007)

The Medieval Chantry Chapel: an Archaeology.

' Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press. . *Tarlow, Sarah. (2011)

Ritual, Belief and the Dead in Early Modern Britain and Ireland.

' Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. . *Wade, G. W. and J. H. Wade. (1929)

' London: Methuen. . *Wilcox, Ronald. (1981). "Excavations at Farleigh Hungerford Castle, Somerset, 1973-6", ''Proceedings of Somerset Archaeology'' 124, pp. 87–109.

External links

Farleigh Hungerford Castle on English Heritage

{{Authority control 1383 establishments in England Buildings and structures completed in 1383 14th-century fortifications Grade I listed buildings in Mendip District Buildings and structures in Mendip District Castles in Somerset English Heritage sites in Somerset Scheduled monuments in Mendip District Historic house museums in Somerset Grade I listed castles Ruined castles in England Grade I listed ruins Articles containing video clips George Plantagenet, Duke of Clarence Richard III of England