Fannie Sellins on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

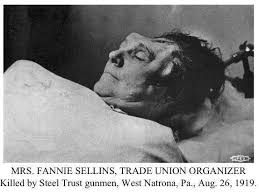

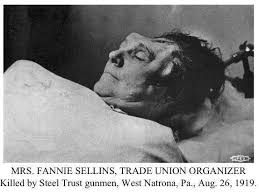

Fannie Sellins (1872 – August 26, 1919) was an American  She was buried from St. Peter's Roman Catholic Church in

She was buried from St. Peter's Roman Catholic Church in

Commonwealth of Pennsylvania Historical Marker

{{DEFAULTSORT:Sellins, Fannie Roman Catholic activists American women trade unionists Activists from Pittsburgh Protest-related deaths 1872 births 1919 deaths People murdered in Pennsylvania American murder victims Deaths by firearm in Pennsylvania People from Brooke County, West Virginia Trade unionists from Pennsylvania

union organizer

A union organizer (or union organiser in Commonwealth spelling) is a specific type of trade union member (often elected) or an appointed union official.

In some unions, the organizer's role is to recruit groups of workers under the organizing ...

.

Born Fanny Mooney in New Orleans

New Orleans (commonly known as NOLA or The Big Easy among other nicknames) is a Consolidated city-county, consolidated city-parish located along the Mississippi River in the U.S. state of Louisiana. With a population of 383,997 at the 2020 ...

, Louisiana

Louisiana ( ; ; ) is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It borders Texas to the west, Arkansas to the north, and Mississippi to the east. Of the 50 U.S. states, it ranks 31st in area and 25 ...

, she married Charles Sellins in St. Louis, Missouri

St. Louis ( , sometimes referred to as St. Louis City, Saint Louis or STL) is an Independent city (United States), independent city in the U.S. state of Missouri. It lies near the confluence of the Mississippi River, Mississippi and the Miss ...

. After his death she worked in a garment factory to support her four children. She helped to organize Local # 67 of the International Ladies' Garment Workers' Union

The International Ladies' Garment Workers' Union (ILGWU) was a labor union for employees in the women's clothing industry in the United States. It was one of the largest unions in the country, one of the first to have a primarily female membersh ...

in St. Louis, where she became a negotiator for 400 women locked out of a garment factory. Thus she came to the attention of Van Bittner, president of District 5 of the United Mine Workers of America

The United Mine Workers of America (UMW or UMWA) is a North American labor union best known for representing coal miners. Today, the Union also represents health care workers, truck drivers, manufacturing workers and public employees in the Unit ...

(UMWA).

In 1913, she moved to begin work for the mine workers union in West Virginia

West Virginia is a mountainous U.S. state, state in the Southern United States, Southern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States.The United States Census Bureau, Census Bureau and the Association of American ...

. Her work, she wrote, was to distribute "clothing and food to starving women and babies, to assist poverty stricken mothers and bring children into the world, and to minister to the sick and close the eyes of the dying." She was arrested once in Colliers, West Virginia

Colliers is an unincorporated community in Brooke County, West Virginia

West Virginia is a mountainous U.S. state, state in the Southern United States, Southern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States.The ...

for defying an anti-union injunction. U.S. President

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president directs the Federal government of the United States#Executive branch, executive branch of the Federal government of t ...

Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was the 28th president of the United States, serving from 1913 to 1921. He was the only History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democrat to serve as president during the Prog ...

intervened for her release.

Sellins had promised to obey the judge's order against picketing. She returned to Colliers from Fairmont, W.Va. and immediately broke her promise by challenging U.S. District Court Judge Alston G. Dayton to arrest her. He did.

With the help of U.S. Congressman Matthew M. Neely

Matthew Mansfield Neely (November 9, 1874January 18, 1958) was an American Democratic politician from West Virginia. He is the only West Virginian to serve in both houses of the United States Congress and as the 21st governor of West Virginia. H ...

, the UMWA waged a public relations campaign to obtain a presidential pardon for Sellins. The union printed thousands of postcards with a photo of Sellins sitting behind the bars of her jail cell in Fairmont. On the back side of the card was the address of the White House.

Philip Murray

Philip Murray (May 25, 1886 – November 9, 1952) was a Scottish-born steelworker and an American labor leader. He was the first president of the Steel Workers Organizing Committee (SWOC), the first president of the United Steelworkers ...

hired Sellins to join the staff of the UMWA in Pittsburgh

Pittsburgh ( ) is a city in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, United States, and its county seat. It is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania#Municipalities, second-most populous city in Pennsylvania (after Philadelphia) and the List of Un ...

, Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania, officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a U.S. state, state spanning the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern United States, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes region, Great Lakes regions o ...

. In 1919, she was assigned to the Allegheny River Valley district to direct picketing by striking miners at Allegheny Coal and Coke Company. On August 26, she witnessed a posse of a dozen of the sheriff's deputies and Coal and Iron Police

The Coal and Iron Police (C&I) was a private police force in the US state of Pennsylvania that existed between 1865 and 1931. It was established by the Pennsylvania General Assembly but employed and paid for by the various coal companies. The Co ...

beating Joseph Starzeleski, a picketing miner, who was killed. When she intervened, deputies shot and killed her with four bullets, then a deputy used a cudgel to fracture her skull. Others said that she was attempting to protect miners' children that were on scene.

She was buried from St. Peter's Roman Catholic Church in

She was buried from St. Peter's Roman Catholic Church in New Kensington, Pennsylvania

New Kensington (known locally as New Ken) is a city in Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania, United States. The population was 12,170 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census. It is situated along the Allegheny River northeast of Pittsburgh ...

on August 29 and interred at Union Cemetery in Arnold. A coroner's jury in 1919 ruled her death justifiable homicide and blamed Sellins for starting the riot which led to her death, although other witnesses portrayed a different event than the deputies at the scene. The union and her family raised money to hire a lawyer to press a criminal investigation and pressure officials to reopen the investigation. A grand jury in Pittsburgh, Allegheny County, indicted three deputies for the killings, but a trial in 1923 ended in acquittal for the two men accused of her murder. The actual gunman, John Pearson, never appeared for his trial and never was seen again. The acquittal was viewed among many in the labor movement as an outrage, a miscarriage of justice and an example of systemic bias against workers and their organizations. An estimated 10,000 marchers attended Sellins' funeral procession.

See also

*Murder of workers in labor disputes in the United States

The list of worker deaths in United States labor disputes captures known incidents of fatal labor-related violence in U.S. labor history, which began in the colonial era with the earliest worker demands around 1636 for better working conditions. ...

References

Further reading

* James Cassedy, “A Bond of Sympathy: The Life and Tragic Death of Fannie Sellins.” ''Labor's Heritage'' (4, Winter 1992): 34-47.External links

Commonwealth of Pennsylvania Historical Marker

{{DEFAULTSORT:Sellins, Fannie Roman Catholic activists American women trade unionists Activists from Pittsburgh Protest-related deaths 1872 births 1919 deaths People murdered in Pennsylvania American murder victims Deaths by firearm in Pennsylvania People from Brooke County, West Virginia Trade unionists from Pennsylvania