The Factory Acts were a series of acts passed by the

The Factory Acts were a series of acts passed by the Health and Morals of Apprentices Act 1802

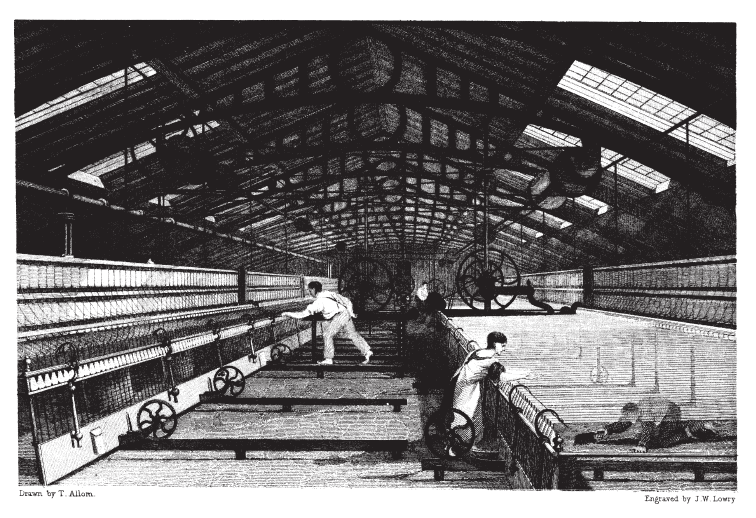

The Health and Morals of Apprentices Act 1802 ( 42 Geo. 3. c. 73) was introduced by Sir Robert Peel; it addressed concerns felt by the medical men ofCotton Mills and Factories Act 1819

The Cotton Mills and Factories Act 1819 ( 59 Geo. 3. c. 66) stated that no children under 9 were to be employed and that children aged 9–16 years were limited to 12 hours' work per day.Early factory legislationParliament.uk. Accessed 2 September 2011. It applied to the cotton industry only, but covered all children, whether apprentices or not. It was seen through Parliament by Sir Robert Peel; it had its origins in a draft prepared by

Cotton Mills Regulation Act 1825

In 1825 John Cam Hobhouse introduced a bill to allow magistrates to act on their own initiative, and to compel witnesses to attend hearings; noting that so far there had been only two prosecutions under the 1819 act. Opposing the bill, a millowner MP agreed that the 1819 bill was widely evaded, but went on to remark that this put millowners at the mercy of millhands "The provisions of Sir Robert Peel's act had been evaded in many respects: and it was now in the power of the workmen to ruin many individuals, by enforcing the penalties for children working beyond the hours limited by that act" and that this showed to him that the best course of action was to repeal the 1819 act. On the other hand, another millowner MP supported Hobhouse's Bill saying that heagreed that, the bill was loudly called for, and, as the proprietor of a large manufactory, admitted that there was much that required remedy. He doubted whether shortening the hours of work would be injurious even to the interests of the manufacturers; as the children would be able, while they were employed, to pursue their occupation with greater vigour and activity. At the same time, there was nothing to warrant a comparison with the condition of the negroes in the West Indies.Hobhouse's bill also sought to limit hours worked to eleven a day; the act as passed, the Cotton Mills Regulation Act 1825 ( 6 Geo. 4. c. 63), improved the arrangements for enforcement, but kept a twelve-hour day Monday-Friday with a shorter day of nine hours on Saturday. The 1819 act had specified that a meal break of an hour should be taken between 11 a.m. and 2 p.m.; a subsequent act, the Labour in Cotton Mills, etc. Act 1819 ( 60 Geo. 3 & 1 Geo. 4. c. 5), allowing water-powered mills to exceed the specified hours in order to make up for lost time widened the limits to 11 a.m. to 4 p.m.; Hobhouse's act set the limits to 11 a.m. to 3 p.m. A parent's assertion of a child's age was sufficient, and relieved employers of any liability should the child in fact be younger. JPs who were millowners or the fathers or sons of millowners could not hear complaints under the act.

Act to Amend the Laws relating to the employment of Children in Cotton Mills & Manufactories 1829

In 1829, Parliament passed an "Act to Amend the Laws relating to the employment of child in Cotton Mills & Manufactories" which relaxed formal requirements for the service of legal documents on millowners (documents no longer had to specify all partners in the concern owning or running the mill; it would be adequate to identify the mill by the name by which it was generally known). The bill passed the Commons but was subject to a minor textual amendment by the Lords (adding the words "to include") and then receivedLabour in Cotton Mills Act 1831 (Hobhouse's Act)

''An Act to repeal the Laws relating to Apprentices and other young Persons employed in Cotton Factories and in Cotton Mills, and to make further Provisions in lieu thereof.'' ( 1 & 2 Will. 4. c. 39) :(Acts repealed were ''59 Geo. 3. c. 66, 60 Geo. 3. c. 5, 6 Geo. 4. c. 63, 10 Geo. 4. c. 51, 10 Geo. 4. c. 63'') In 1831 Hobhouse introduced a further bill with – he claimed to the Commons – the support of the leading manufacturers who felt that "unless the House should step forward and interfere so as to put an end to the night-work in the small factories where it was practised, it would be impossible for the large and respectable factories which conformed to the existing law to compete with them." The Act repealed the previous Acts, and consolidated their provisions in a single Act, which also introduced further restrictions. Night working was forbidden for anyone under 21 and if a mill had been working at night the onus of proof was on the millowner (to show nobody under-age had been employed). The limitation of working hours to twelve now applied up to age eighteen. Complaints could only be pursued if made within three weeks of the offence; on the other hand justices of the peace who were the brothers of millowners were now also debarred from hearing Factory Act cases. Hobhouse's claim of general support was optimistic; the Bill originally covered all textile mills; the Act as passed again applied only to cotton mills.Labour of Children, etc., in Factories Act 1833 (Althorp's Act)

The first 'Ten Hour Bill' – Sadler's Bill (1832), Ashley's Bill (1833)

Dissatisfied with the outcome of Hobhouse's efforts, in 1832 Michael Thomas Sadler introduced a Bill extending the protection existing Factory Acts gave to children working in the cotton industry to those in other textile industries, and reducing to ten per day the working hours of children in the industries legislated for. A network of "Short Time Committees" had grown up in the textile districts of Yorkshire and Lancashire, working for a "ten-hour day Act" for children, with many millhands in the Ten Hour Movement hoping that this would in practice also limit the adult working day. Witnesses to one of the Committees taking evidence on Peel's Bill had noted that there were few millworkers over forty, and that they themselves expected to have to stop mill work at that age because of "the pace of the mill" unless working hours were reduced. see in particular the evidence of a 36-year-old spinner Robert Hyde pp 25–30 Hobhouse advised Richard Oastler, an early and leading advocate of factory legislation for the woolen industry, that Hobhouse had got as much as he could, given the opposition of Scottish flax-spinners and "the state of public business": if Sadler put forward a Bill matching the aims of the Short Time Committees "he will not be allowed to proceed a single stage with any enactment, and ... he will only throw an air of ridicule and extravagance over the whole of this kind of legislation". Oastler responded that a failure with a Ten Hour Bill would "not dishearten its friends. It will only spur them on to greater exertions, ''and would undoubtedly lead to certain success''".the correspondence can also be found as in the British Newspaper ArchiveSadler's Bill (1832)

Sadler's Bill when introduced indeed corresponded closely to the aims of the Short Time Committees. Hobhouse's ban on nightwork up to 21 was retained; no child under nine was to be employed; and the working day for under-eighteens was to be no more than ten hours (eight on Saturday). These restrictions were to apply across all textile industries. The Second Reading debate on Sadler's bill did not take place until 16 March 1832, the Reform Bill having taken precedence over all other legislation. Meanwhile, petitions both for and against the Bill had been presented to the Commons; both Sir Robert Peel (not the originator of the 1802 bill, but his son, the future Prime Minister) and Sir George Strickland had warned that the Bill as it stood was too ambitious: more MPs had spoken for further factory legislation than against, but many supporters wanted the subject to be considered by a Select Committee. Sadler had resisted this: "if the present Bill was referred to one, it would not become a law this Session, and the necessity of legislating was so apparent, that he was unwilling to submit to the delay of a Committee, when he considered they could obtain no new evidence on the subject". In his long Second Reading speech, Sadler argued repeatedly that a Committee was unnecessary, but concluded by accepting that he had not convinced the House or the Government of this, and that the Bill would be referred to a Select Committee. (Lord Althorp, responding for the Government, noted that Sadler's speech made a strong case for considering legislation, but thought it did little to directly support the details of the Bill; the Government supported the Bill as leading to a Select Committee, but would not in advance pledge support for whatever legislation the Committee might recommend). This effectively removed any chance of a Factories Regulation Act being passed before Parliament was dissolved. Sadler was made chairman of the Committee, which allowed him to make his case by hearing evidence from witnesses of Sadler's selection, on the understanding that opponents of the Bill (or of some feature of it) would then have their innings. Sadler attempted (31 July 1832) to progress his Bill without waiting for the committee's report; when this abnormal procedure was objected to by other MPs, he withdrew the Bill. Sadler, as chairman of the committee, reported the minutes of evidence on 8 August 1832, when they were ordered to be printed. Parliament was prorogued shortly afterwards: Sadler gave notice of his intention to reintroduce a Ten-Hour Bill in the next sessionAshley's Bill (1833)

Sadler, however, was not an MP in the next session: in the first election for the newly enfranchised two member constituency of1833 Factory Commission

This toured the textile districts and made extensive investigations. It wasted little time in doing so, and even less in considering its report; as with other Whig commissions of the period it was suspected to have had a good idea of its recommendations before it started work. During the course of the Factory Commission's inquiries, relationships between it and the Ten Hour Movement became thoroughly adversarial, the Ten Hour Movement attempting to organise a boycott of the commission's investigations: this was in sharp contrast with the commissioners' practice of dining with the leading manufacturers of the districts they visited. The commission's report(Report of the Commissioners on Conditions in Factories, Parliamentary Papers, 1833, volume XX), subsequent extracts are as given in extracts from did not support the more lurid details of Sadler's report – mills were not hotbeds of sexual immorality, and beating of children was much less common than Sadler had asserted (and was dying out). Major millowners such as the Strutts did not tolerate it (and indeed were distinguished by their assiduous benevolence to their employees). Working conditions for mill-children were preferable to those in other industries: after a visit to the coal mine at Worsley one of the commission staff had written Nonetheless, the commission reportedthat mill children did work unduly long hours, leading to * ''Permanent deterioration of the physical constitution:'' * ''The production of disease often wholly irremediable:'' and * ''The partial or entire exclusion (by reason of excessive fatigue) from the means of obtaining adequate education and acquiring useful habits, or of profiting by those means when afforded'' and that these ill-effects were so marked and significant that government intervention was justified but where Sadler's Bill was for a ten-hour day for all workers under eighteen, the commission recommended an eight-hour day for those under thirteen, hoping for a two-shift system for them which would allow mills to run 16 hours a day.Althorp's Act (1833)

The Factory Act 1833 ( 3 & 4 Will. 4. c. 103) was an attempt to establish a regular working day in textile manufacture. The act had the following provisions: *Children (ages 9–12) are limited to 48 hours per week. *Children under 9 were not allowed to be employed in factories, except in silk mills. *Children under 18 must not work at night (i.e. after 8.30 p.m. and before 5.30 a.m.) *Children (ages 9–13) must not work more than 8 hours with an hour lunch break. (Employers could (and it was envisaged they would) operate a 'relay system' with two shifts of children between them covering the permitting working day; adult millworkers therefore being 'enabled' to work a 15-hour day) *Children (ages 9–13) could only be employed if they had a schoolmaster's certificate that the previous week they had two hours of education per day (This was to be paid for by a deduction of a penny in the shilling from the children's wages. A factory inspector could disallow payment of any of this money to an 'incompetent' schoolmaster, but could not cancel a certificate issued by him.)R J Saunders "Report on the Establishment of Schools in the Factory District" in *Children (ages 14–18) must not work more than 12 hours a day with an hour lunch break. *Provided for routine inspections of factories and set up a Factory Inspectorate (subordinate to the'Ineffectual attempts at legislation' (1835–1841)

The 1833 act had few admirers in the textile districts when it came into force. The short-time movement objected to its substitution for Ashley's Bill, and hoped to secure a Ten-Hour Bill. Millowners resented and political economists deplored legislators' interference in response to public opinion, and hoped that the Act could soon be repealed (completely or in part). In 1835, the first report of the Factory Inspectors noted that the education clauses were totally impracticable, and relay working (with a double set of children, both sets working eight hours; the solution which allowed Althorp's Bill to outbid Ashley's in the apparent benefit to children) was difficult if not impracticable, there not being enough children.They also reported that they had been unable to discover any deformity produced by factory labour, nor any injury to health or shortening of the life of factory children caused by working a twelve-hour day. The inspectors appointed were also largely ineffective, simply because there were not enough of them to oversee all 4000 factories on the island. The idea of government-appointed inspectors would gain traction within the following decades, but for now, they were mostly figureheads.Poulett Thomson's bill (1836)

Three of the four inspectors had recommended in their first report that all children 12 or older should be allowed to work twelve hours a day. This was followed by an agitation in the West Riding for relaxation or repeal of the 1833 Act; the short-time movement alleged that workers were being 'leant on' by their employers to sign petitions for repeal, and countered by holding meetings and raising petitions for a ten-hour act. Charles Hindley prepared a draft bill limiting the hours that could be worked by any mill employing people under twenty-one, with no child under ten to be employed, and no education clauses. Hindley's bill was published at the end of the 1834-5 parliamentary session, but was not taken forward in the next session, being pre-empted by a government bill introduced by Charles Poulett Thomson, theFox Maule's bill (1838)

In the 1838 session another government factory bill was introduced by Fox Maule Under-Secretary of State for the Home Department. Children in silk mills were not to work more than ten hours a day (but this was not backed up by any certification of age). Otherwise, the bill made no changes to age limits or hours of work, but repealed the education clauses of the 1833 Act, replacing them with literacy tests. After a transitional period, children who could not read the New Testament were not to be employed more than nine hours a day; children who could not read an easy reader to be published by theAshley denounces government complacency

On 22 June, when the government intended to progress a bill on Irish tithes, Ashley forestalled them, moving the second reading of the factory bill. He complained of the evasive conduct of ministers and government apathy and complacency on factory reform. Peel (who normally, even in opposition, deprecated obstruction of government business by backbenchers) supported Ashley: he held very different views on the issue from Ashley, but the issue was important, contentious, and should not be evaded : "so long as ineffectual attempts at legislation remained on the table of the house, the excitement of the manufacturing districts would continue to be kept up": not to be found in the on-line Hansard; that jumps from volume 42 to volume 44 Ashley's motion was lost narrowly 111 to 119. Ashley later attacked the government and its complacency and connivance at the shortcomings in the current Factory Act identified by the government's own Factory Inspectors: * Althorp's Act had claimed superiority over Ashley's Bill of 1833 because of its shorter working hours for children and its provision for education. Those provisions had been violated from the outset, and continued to be violated, and the government connived at those violations: "notwithstanding the urgent representations and remonstrances of their own inspectors, the Government had done nothing whatever to assist them in the discharge of their duties" * Millowners sat on the bench and adjudicated in their own cases (because Althorp's Act had repealed the provisions in Hobhouse's Act forbidding this): they countersigned surgeon's certificates for children employed in their own factory . One factory inspector had reported a case of a millowner sitting as magistrate on a case brought against his own sons, as tenants of a mill he owned. * Magistrates had the power to mitigate the penalties specified in the Act. The inspectors reported that magistrates habitually did so, and to an extent which defeated the law; it was more profitable to break the law and pay the occasional fine than to comply with the Act."After these representations .. by his own inspectors, how could the noble Lord opposite reconcile it with his conscience as an individual, and with his public duty as a Minister of the Crown, during the whole course of his administration, never to have brought forward any measure for the removal of so tremendous an evil?"* The education clauses were not observed in one mill in fifty; where they were, the factory inspectors reported, "the schooling given is a mere mockery of instruction"; vice and ignorance, and their natural consequences, misery and suffering, were rife among the population of the manufacturing districts. "Would the noble Lord opposite venture to say that the education of the manufacturing classes was a matter of indifference to the country at large?"

"He wanted them to decide whether they would amend, or repeal, or enforce the Act now in existence; but if they would do none of these things, if they continued idly indifferent, and obstinately shut their eyes to this great and growing evil, if they were careless of the growth of an immense population, plunged in ignorance and vice, which neither feared God, nor regarded man, then he warned them that they must be prepared for the very worst result that could befall a nation."

Fox Maule tries again (1839–41)

In the 1839 session, Fox Maule revived the 1838 Bill with alterations. The literacy tests were gone, and the education clauses restored. The only other significant changes in the scope of the legislation were that working extra hours to recover lost time was now only permitted for water-powered mills, and magistrates could not countersign surgeon's certificates if they were mill-owners or occupiers (or father, son, or brother of a mill-owner or occupier). Details of enforcement were altered; there was no longer any provision for inspectors to be magistrates ''ex officio'', sub-inspectors were to have nearly the same enforcement powers as inspectors; unlike inspectors they could not examine witnesses on oath, but they now had the same right of entry into factory premises as inspectors. Declaring a schoolmaster incompetent was now to invalidate certificates of education issued by him, and a clause in the bill aimed to make it easier to establish and run a school for factory children; children at schools formed under this clause were not to be educated in a creed objected to by their parents. The bill, introduced in February, did not enter its committee stage until the start of July In committee, a ten-hour amendment was defeated 62–94, but Ashley moved and carried 55-49 an amendment removing the special treatment of silk mills. The government then declined to progress the amended bill. No attempt was made to introduce a factory bill in 1840; Ashley obtained a select committee on the working of the existing Factory Act, which took evidence, most notably from members of the Factory Inspectorate, throughout the session with a view to a new bill being introduced in 1841. Ashley was then instrumental in obtaining a royal commission on the employment of children in mines and manufactures, which eventually reported in 1842 (mines) and 1843 (manufactures): two of the four commissioners had served on the 1833 Factory Commission; the other two were serving factory inspectors. In March 1841 Fox Maule introduced a Factory Bill and a separate Silk Factory Bill. The Factory Bill provided that children were now not to work more than seven hours a day; if working before noon they couldn't work after one p.m. The education clauses of the 1839 Bill were retained. 'Dangerous machinery' was now to be brought within factory legislation. Both the Factory and Silk Factory bills were given unopposed second readings on the understanding that all issues would be discussed at committee stage, both were withdrawn before going into committee, the Whigs having been defeated on a motion of no confidence, and a General Election imminent.Graham's Factory Education Bill (1843)

The Whigs were defeated in the 1841 general election, and Sir Robert Peel formed a Conservative government. Ashley let it be known that he had declined office under Peel because Peel would not commit himself not to oppose a ten-hour bill; Ashley therefore wished to retain freedom of action on factory issues. In February 1842, Peel indicated definite opposition to a ten-hour bill, and Sir James Graham, Peel's Home Secretary, declared his intention to proceed with a bill prepared by Fox Maule, but with some alterations. In response to the findings of his Royal Commission, Ashley saw through Parliament a Mines And Collieries Act banning the employment of women and children underground; the measure was welcomed by both front benches, with Graham assuring Ashley "that her Majesty's Government would render him every assistance in carrying on the measure". In July, it was announced that the government did not intend any modification to the Factory Act in that session.The education issue and Graham's bill

The royal commission had investigated not only the working hours and conditions of the children, but also their moral state. It had found much of concern in their habits and language, but the greatest concern was that "the means of secular and religious instruction.. are so grievously defective, that, in all the districts, great numbers of Children and Young Persons are growing up without any religious, moral, or intellectual training; nothing being done to form them to habits of order, sobriety, honesty, and forethought, or even to restrain them from vice and crime."2nd Report of the Commission on the Employment of Children (Trades and Manufactures), (1843) Parliamentary Papers volume XIII, pp 195–204 as quoted in In 1843, Ashley initiated a debate on "the best means of diffusing the benefits and blessings of a moral and religious education among the working classes..." Responding, Graham stressed that the issue was not a party one (and was borne out on this by the other speakers in the debate); although the problem was a national one, the government would for the moment bring forward measures only for the two areas of education in which the state already had some involvement; the education of workhouse children and the education of factory children. The measures he announced related to England and Wales; Scotland had an established system of parochial schools run by its established church, with little controversy, since in Scotland there was no dissent on doctrine, only on questions of discipline. In the 'education clauses' of his Factory Education Bill of 1843, he proposed to make government loans to a new class of government factory schools effectively under the control of the Church of England and the local magistrates. The default religious education in these schools would be Anglican, but parents would be allowed to opt their children out of anything specifically Anglican; if the opt-out was exercised, religious education would be as in the best type of Dissenter-run schools. Once a trust school was open in a factory district, factory children in that district would have to provide a certificate that they were being educated at it or at some other school certified as 'efficient'. The 'labour clauses' forming the other half of the bill were essentially a revival of Fox Maule's draft; children could work only in the morning or in the afternoon, but not both. There were two significant differences; the working day for children was reduced to six and a half hours, and the minimum age for factory work would be reduced to eight. Other clauses increased penalties and assisted enforcement.Reaction, retreats, and abandonment

A Second Reading debate was held to flesh out major issues before going into committee. At Lord John Russell's urging, the discussion was temperate, but there was considerable opposition to the proposed management of the new schools, which effectively excluded ratepayers (who would repay the loan and meet any shortfall in running costs) and made no provision for a Dissenter presence (to see fair play). The provisions for appointment of schoolmasters were also criticised; as they stood they effectively excluded Dissenters. Out of Parliament, the debate was less temperate; objections that the Bill had the effect of strengthening the Church became objections that it was a deliberate attack on Dissent, that its main purpose was to attack Dissent, and that the Royal Commission had deliberately and grossly defamed the population of the manufacturing districts to give a spurious pretext for an assault on Dissent. Protest meetings were held on that basis throughout the country, and their resolutions condemning the bill and calling for its withdrawal were supported by a campaign of organised petitions: that session Parliament received 13,369 petitions against the bill as drafted with a total of 2,069,058 signatures. (For comparison, in the same session there were 4574 petitions for total repeal of the Corn Laws, with a total of 1,111,141 signatures.) Lord John Russell drafted resolutions calling for modification of the bill along the lines suggested in Parliament; the resolutions were denounced as inadequate by the extra-parliamentary opposition. Graham amended the educational clauses, but this only triggered a fresh round of indignation meetings and a fresh round of petitions (11,839 petitions and 1,920,574 signatures). Graham then withdrew the education clauses but this did not end the objections, since it did not entirely restore the ''status quo ante'' on education. Indeed the education requirements of the 1833 Act now came under attack, the '' Leeds Mercury'' declaring education was something individuals could do for themselves "under the guidance of natural instinct and self-interest, infinitely better than Government could do for them". Hence "''All Government interference to'' COMPEL ''Education is wrong''" and had unacceptable implications: "If Government has a right to compel Education, it has right to ''compel'' RELIGION !" Although as late as 17 July Graham said he intended to get the bill though in the current session, three days later the bill was one of those Peel announced would be dropped for that session.Factories Act 1844 ('Graham's Factory Act')

In 1844 Graham again introduced a Bill to bring in a new Factory Act and repeal the Factory Act 1833. The Bill gave educational issues a wide berth, but otherwise largely repeated the 'labour clauses' of Graham's 1843 Bill, with the important difference that the existing protection of young persons (a twelve-hour day and a ban on night working) was now extended to women of all ages. In Committee, Lord Ashley moved an amendment to the bill's clause 2, which defined the terms used in subsequent (substantive) clauses; his amendment changed the definition of 'night' to 6 p.m. to 6 a.m. – after allowing 90 minutes for mealbreaks only ten-and-a-half hours could be worked; this passed by nine votes. On clause 8, limiting the hours of work for women and young persons, the motion setting a twelve-hour day was defeated (by three votes: 183–186) but Lord Ashley's motion setting the limit at ten hours was also defeated (by seven votes:181–188). Voting on this Bill was not on party lines, the issue revealing both parties to be split into various factions. On clause 8, both 'ten' and 'twelve' hours were rejected (with exactly the same members voting) because five members voted against both 'ten' and 'twelve'. Faced with this impasse, and having considered and rejected the option of compromising on some intermediate time such as eleven hours, Graham withdrew the Bill, preferring to replace it by a new one which amended, rather than repealed, the 1833 Act. Richard Monckton Milnes, a Radical MP warned the government during the debate on clause 8 that Ashley's first victory could never be undone by any subsequent vote: morally the Ten-Hour question had been settled; Government might delay, but could not now prevent, a Ten-hour Act. However, the new bill left the 1833 definition of 'night' unaltered (and so gave no opportunity for redefinition) and Lord Ashley's amendment to limit the working day for women and young persons to ten hours was defeated heavily (295 against, 198 for), it having been made clear that the Ministers would resign if they lost the vote.As a result, the ( 7 & 8 Vict. c. 15) again set a twelve-hour day, its main provisions being: *Children 9–13 years could work for 9 hours a day with a lunch break. *Ages must be verified by surgeons. *Women and young people now worked the same number of hours. They could work for no more than 12 hours a day during the week, including one and a half hours for meals, and 9 hours on Sundays. They must all take their meals at the same time and could not do so in the workroom *Time-keeping to be by a public clock approved by an inspector *Some classes of machinery: ''every fly-wheel directly connected with the steam engine or water-wheel or other mechanical power, whether in the engine-house or not, and every part of a steam engine and water-wheel, and every hoist or teagle, near to which children or young persons are liable to pass or be employed, and all parts of the mill-gearing'' (this included power shafts) ''in a factory'' were to be "securely fenced." *Children and women were not to clean moving machinery. *Accidental death must be reported to a surgeon and investigated; the result of the investigation to be reported to a factory inspector. *Factory owners must wash factories with lime every fourteen months. *Thorough records must be kept regarding the provisions of the Act and shown to the inspector on demand. *An abstract of the amended Act must be hung up in the factory ''so as to be easily read'', and show (amongst other things) names and addresses of the inspector and sub-inspector of the district, the certifying surgeon, the times for beginning and ending work, the amount of time and time of day for meals. *Factory inspectors no longer had the powers of JPs but (as before 1833) millowners, their fathers, brothers and sons were all debarred (if magistrates) from hearing Factory Act cases.

Factories Act 1847

After the collapse of the Peel administration which had resisted any reduction in the working day to less than 12 hours, a Whig administration under Lord John Russell came to power. The new Cabinet contained supporters and opponents of a ten-hour day and Lord John himself favoured an eleven-hour day. The government therefore had no collective view on the matter; in the absence of government opposition, the Ten Hour Bill was passed, becoming the Factories Act 1847 ( 10 & 11 Vict. c. 29). This law (also known as the Ten Hour Act) limited the work week in textile mills (and other textile industries except lace and silk production) for women and children under 18 years of age. Each work week contained 63 hours effective 1 July 1847 and was reduced to 58 hours effective 1 May 1848. In effect, this law limited the workhours only for women and children to 10 hours which earlier was 12 hours. This law was successfully passed due to the contributions of the Ten Hours Movement. This campaign was established during the 1830s and was responsible for voicing demands towards limiting the work week in textile mills. The core of the movement was the 'Short Time Committees' set up (by millworkers and sympathisers) in the textile districts, but the main speakers for the cause were Richard Oastler (who led the campaign outside Parliament) and Lord Ashley, 7th Earl of Shaftesbury (who led the campaign inside Parliament). John Fielden, although no orator, was indefatigable in his support of the cause, giving generously of his time and money and – as the senior partner in one of the great cotton firms – vouching for the reality of the evils of a long working day and the practicality of shortening it.Factories Act 1850 (the 'Compromise Act')

Factories Act 1856

In April 1855 a National Association of Factory Occupiers (NAFO) was formed "to watch over factory legislation with a view to prevent any increase of the present unfair and injudicious enactments". The 1844 act had required that "mill gearing" – which included power shafts – should be securely fenced. Magistrates had taken inconsistent views as to whether this applied where the "mill gearing" was not readily accessible; in particular where power shafting ran horizontally well above head height. In 1856, the Court of Queen's Bench ruled that it did. In April 1856, the National Association of Factory Occupiers succeeded in obtaining the ( 19 & 20 Vict. c. 38) reversing this decision: mill gearing needed secure fencing only of those parts with which women, young persons, and children were liable to come in contact. (The inspectors feared that the potential hazards in areas they did not normally access might be obvious to experienced men, but not be easily appreciated by women and children who were due the legislative protection the 1856 act had removed, especially given the potential severe consequences of their inexperience. An MP speaking against the bill was able to give multiple instances of accidents to protected persons resulting in death or loss of limbs – all caused by unguarded shafting with which they were supposedly not liable to come into contact – despite restricting himself to accidents in mills owned by Members of Parliament (so that he could be corrected by them if had misstated any facts). ( Dickens thereafter referred to the NAFO as the ''National Association for the Protection of the Right to Mangle Operatives''.Factories Act Extension Act 1867

In virtually every debate on the various Factories Bills, opponents had thought it a nonsense to pass legislation for textile mills when the life of a mill child was much preferable to that of many other children: other industries were more tiring, more dangerous, more unhealthy, required longer working hours, involved more unpleasant working conditions, or (this being Victorian Britain) were more conducive to lax morals. This logic began to be applied in reverse once it became clear that the Ten Hours Act had had no obvious detrimental effect on the prosperity of the textile industry or on that of millworkers. Acts were passed making similar provisions for other textile trades: bleaching and dyeworks (the ( 23 & 24 Vict. c. 78) – outdoor bleaching was excluded), lace work (the ( 24 & 25 Vict. c. 117)), calendaring (the ( 26 & 27 Vict. c. 38)), and finishing (the ( 27 & 28 Vict. c. 98)). A further act, the ( 33 & 34 Vict. c. 62), repealed these acts and brought the ancillary textile processes (including outdoor bleaching) within the scope of the main Factory Act. The ( 27 & 28 Vict. c. 48) extended the Factories Act to cover a number of occupations (mostly non-textile): potteries (both heat and exposure to lead glazes were issues), lucifer match making ('phossie jaw') percussion cap and cartridge making, paper staining and fustian cutting. In 1867 the Factories Act was extended to all establishments employing 50 or more workers by the ( 30 & 31 Vict. c. 103). An Hours of Labour Regulation Act applied to 'workshops' (establishments employing less than 50 workers); it subjected these to requirements similar to those for 'factories' (but less onerous on a number of points e.g.: the hours within which the permitted hours might be worked were less restrictive, there was no requirement for certification of age) but was to be administered by local authorities, rather than the Factory Inspectorate. There was no requirement on local authorities for enforcement (or penalties for non-enforcement) of legislation for workshops. The effectiveness of the regulation of workshops therefore varied from area to area; where it was effective, a blanket ban on Sunday working in workshops was a problem for observant Jews. The Factory and Workshop Act 1870 removed the previous special treatments for factories in the printing, dyeing and bleaching industries; while a short act, the } ( 34 & 35 Vict. c. 104), transferred responsibility for regulation of workshops to the Factory Inspectorate, but without an adequate increase in the inspectorates's resources. A separate act, the ( 34 & 35 Vict. c. 19) allowed Sunday working by Jews.Factories (Health of Women, &c.) Act (1874)

The newly-legalisedShaftesbury's valedictory review

Shaftesbury spoke in the Lords Second Reading debate; thinking it might well be his last speech in Parliament on factory reform, he reviewed the changes over the forty-one years it had taken to secure a ten-hour-day, as this bill at last did. In 1833, only two manufacturers had been active supporters of his bill; all but a handful of manufacturers supported the 1874 bill. Economic arguments against reducing working hours had been disproved by decades of experience. Despite the restrictions on hours of work, employment in textile mills had increased (1835; 354,684, of whom 56,455 under 13: in 1871, 880,920 of whom 80,498 under 13), but accidents were half what they had been and 'factory cripples' were no longer seen. In 1835, he asserted, seven-tenths of factory children were illiterate; in 1874 seven-tenths had "a tolerable, if not a sufficient, education". Furthermore, police returns showed "a decrease of 23 percent in the immorality of factory women". The various protective acts now covered over two and a half million people. During the short-time agitation he had been promised "Give us our rights, and you will never again see violence, insurrection, and disloyalty in these counties." And so it had proved: the Cotton Famine had thrown thousands out of work, with misery, starvation, and death staring them in the face; but, "with one or two trifling exceptions, and those only momentary", order and peace had reigned.By legislation you have removed manifold and oppressive obstacles that stood in the way of the working man's comfort, progress, and honour. By legislation you have ordained justice, and exhibited sympathy with the best interests of the labourers, the surest and happiest mode of all government. By legislation you have given to the working classes the full power to exercise, for themselves and for the public welfare, all the physical and moral energies that God has bestowed on them; and by legislation you have given them means to assert and maintain their rights; and it will be their own fault, not yours, my Lords, if they do not, with these abundant and mighty blessings, become a wise and an understanding people.

Factory and Workshop Act 1878 (the 'Consolidation Act')

The Factory and Workshop Act 1878 ( 41 & 42 Vict. c. 16) consolidated and repealed 16 previous factory acts.Factory Act 1891

The Factory and Workshop Act 1891 ( 54 & 55 Vict. c. 75), under the heading 'Conditions of Employment' introduced two considerable additions to previous legislation: the first is the prohibition on employers to employ women within four weeks after confinement (childbirth); the second the raising the minimum age at which a child can be set to work from ten to eleven.Factory and Workshop Act 1895

The main article gives an overview of the state of Factory Act legislation in Edwardian Britain under the Factory and Workshop Acts 1878 to 1895 (the collective title of the Factory and Workshop Act 1878, the Factory and Workshop Act 1883, the Cotton Cloth Factories Act 1889, the Factory and Workshop Act 1891 and the Factory and Workshop Act 1895.)Factory and Workshop Act 1901

The Factory and Workshop Act 1901 ( 1 Edw. 7. c. 22) raised the minimum working age to 12. The act also introduced legislation regarding the education of children, meal times, and fire escapes. Children could also take up a full-time job at the age of 13 years old.Review in 1910

By 1910, Sidney Webb reviewing the cumulative effect of century of factory legislation felt able to write: He also commented on the gradual (accidentally almost Fabian) way this transformation had been achievedFactories Act 1937

The Factories Act 1937 ( 1 Edw. 8. & 1 Geo. 6. c. 67) consolidated and amended the Factory and Workshop Acts from 1901 to 1929. It was introduced to the House of Commons by theFactories Act 1959

The Factories Act 1959 ( 7 & 8 Eliz. 2. c. 67) amended the previous Acts of 1937 and 1948, as well as adding more health, safety and welfare provisions for factory workers. It also revoked regulation 59 of the Defence (General) Regulations 1939 ( SR&O 1939/927). The act is dated 29 July 1959.Factories Act 1961

The Factories Act 1961 ( 9 & 10 Eliz. 2. c. 34) consolidated the 1937 and 1959 acts. , the Factories Act 1961 is substantially still in force, though workplace health and safety is principally governed by the Health and Safety at Work etc. Act 1974 (c. 37) and regulations made under it.See also

*Notes

References

Further reading

* * "Child Labour during the Industrial Revolution" iEncyclopedia of British History

* {{cite book, title=Law and Society in England 1750–1950, author = W.R. Cornish and G. de N. Clark (Available onlin

here

. * Finer, Samuel Edward. ''The life and times of Sir Edwin Chadwick'' (1952

excerpt

pp 50–68. * Peacock, Alan E. "The successful prosecution of the Factory Acts, 1833-55." ''Economic History Review'' (1984): 197-210

online

* Pollard, Sidney. "Factory Discipline in the Industrial Revolution." ''Economic History Review,'' 16#2 1963, pp. 254–271

online

* Thomas, Maurice W. ''The Early Factory Legislation'' (1948

online

External links

The 1833 Factory Act on the UK Parliament website

– a selection of primary documents

Acts of the Parliament of the United Kingdom Child labour in the United Kingdom United Kingdom labour law United Kingdom Acts of Parliament 1802 United Kingdom Acts of Parliament 1819 United Kingdom Acts of Parliament 1833 United Kingdom Acts of Parliament 1844 United Kingdom Acts of Parliament 1847 United Kingdom Acts of Parliament 1850 United Kingdom Acts of Parliament 1867 United Kingdom Acts of Parliament 1878 United Kingdom Acts of Parliament 1891 Health and safety in the United Kingdom Children's rights in the United Kingdom Women's rights in the United Kingdom Cotton production Articles containing video clips