Exmoor on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Exmoor () is loosely defined as an area of hilly open

According to the late 13th-century

According to the late 13th-century

Hamilton, Archibald. The Red Deer of Exmoor, 1906, Chapter 12, The Forest of Exmoor under the Plantagenets and Tudors

, pp.190–210 William Lucar of "Wythecomb", the brother of Elizabeth Lucar, was forester ''temp.'' under Henry VI, between 1422 and 1461. William de Botreaux, 3rd Baron Botreaux was appointed in 1435 warden of the forests of Exmoor and Neroche for life by Richard Duke of York. The Botreaux family had long held the manor of Molland at the southern edge of Exmoor, but were probably resident mainly at North Cadbury in Somerset. On 10 May 1461 William Bourchier, 9th Baron FitzWarin, feudal baron of Bampton was appointed by King Edward IV as Master Forester of the Forests of Exmoor and Neroche for life. Sir John Poyntz of Iron Acton, Gloucestershire, was warden or chief forester of Exmoor in 1568 when he brought an action in the Court of Exchequer against Henry Rolle (of Heanton Satchville, Petrockstowe), the powerful lord of the manors of Exton, Hawkridge and Withypool. In 1608 Sir Hugh Pollard was named as chief forester in a suit brought before the Court of Exchequer by his deputy William Pincombe.

In addition to the Exmoor Coastal Heaths Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI), two other areas are specifically designated. North Exmoor covers and includes the Dunkery Beacon and the Holnicote and Horner Water

In addition to the Exmoor Coastal Heaths Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI), two other areas are specifically designated. North Exmoor covers and includes the Dunkery Beacon and the Holnicote and Horner Water

.

The National Park, 71% of which is in Somerset and 29% in Devon, has a resident population of 10,600. It was designated a National Park in 1954, under the 1949 National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act. About three quarters of the park is privately owned, made up of numerous private estates. The largest landowners are the

The National Park, 71% of which is in Somerset and 29% in Devon, has a resident population of 10,600. It was designated a National Park in 1954, under the 1949 National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act. About three quarters of the park is privately owned, made up of numerous private estates. The largest landowners are the

Hamilton, Archibald. The Red Deer of Exmoor, 1906, Chapter 12, The Forest of Exmoor under the Plantagenets and Tudors

pp. 190–210 * * * *

Exmoor National Park Authority

nbsp;– a charity to protect and enhance the landscapes of Exmoor {{Authority control Hills of Somerset English royal forests Environment of Somerset Hills of Devon Geography of Somerset West Somerset Geology of Devon Parks and open spaces in Devon Parks and open spaces in Somerset Protected areas established in 1954 National parks in England Dark-sky preserves in England International Dark Sky Reserves Natural regions of England Moorlands of England

moorland

Moorland or moor is a type of Habitat (ecology), habitat found in upland (geology), upland areas in temperate grasslands, savannas, and shrublands and the biomes of montane grasslands and shrublands, characterised by low-growing vegetation on So ...

in west Somerset

Somerset ( , ), Archaism, archaically Somersetshire ( , , ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is bordered by the Bristol Channel, Gloucestershire, and Bristol to the north, Wiltshire to the east ...

and north Devon

Devon ( ; historically also known as Devonshire , ) is a ceremonial county in South West England. It is bordered by the Bristol Channel to the north, Somerset and Dorset to the east, the English Channel to the south, and Cornwall to the west ...

in South West England

South West England, or the South West of England, is one of the nine official regions of England, regions of England in the United Kingdom. Additionally, it is one of four regions that altogether make up Southern England. South West England con ...

. It is named after the River Exe

The River Exe ( ) is a river in England that source (river), rises at Exe Head, near the village of Simonsbath, on Exmoor in Somerset, from the Bristol Channel coast, but flows more or less directly due south, so that most of its length lie ...

, the source of which is situated in the centre of the area, two miles north-west of Simonsbath

Simonsbath () is a small village high on Exmoor in the England, English ceremonial county, county of Somerset. It is the principal settlement in the Exmoor civil parish, which is the largest and most sparsely populated civil parish on Exmoo ...

. Exmoor is more precisely defined as the area of the former ancient royal hunting forest, also called Exmoor, which was officially surveyed 1815–1818 as in extent. The moor has given its name to a National Park

A national park is a nature park designated for conservation (ethic), conservation purposes because of unparalleled national natural, historic, or cultural significance. It is an area of natural, semi-natural, or developed land that is protecte ...

, which includes the Brendon Hills

The Brendon Hills are a range of hills in west Somerset, England. The hills merge level into the eastern side of Exmoor and are included within the Exmoor National Park. The highest point of the range is Lype Hill at above sea level with a sec ...

, the East Lyn Valley

East Lyn Valley is a valley of Exmoor, covering northern Devon and western Somerset, England.

The East Lyn River is formed from several main tributaries including Hoar Oak Water beginning near Weir Water. Its mouth is at Lynmouth at the confluen ...

, the Vale of Porlock and of the Bristol Channel

The Bristol Channel (, literal translation: "Severn Sea") is a major inlet in the island of Great Britain, separating South Wales (from Pembrokeshire to the Vale of Glamorgan) and South West England (from Devon to North Somerset). It extends ...

coast. The total area of the Exmoor National Park is , of which 71% is in Somerset and 29% in Devon.

The upland area is underlain by sedimentary

Sedimentary rocks are types of rock formed by the cementation of sediments—i.e. particles made of minerals (geological detritus) or organic matter (biological detritus)—that have been accumulated or deposited at Earth's surface. Sedime ...

rocks dating from the Devonian

The Devonian ( ) is a period (geology), geologic period and system (stratigraphy), system of the Paleozoic era (geology), era during the Phanerozoic eon (geology), eon, spanning 60.3 million years from the end of the preceding Silurian per ...

and early Carboniferous

The Carboniferous ( ) is a Geologic time scale, geologic period and System (stratigraphy), system of the Paleozoic era (geology), era that spans 60 million years, from the end of the Devonian Period Ma (million years ago) to the beginning of the ...

periods with Triassic

The Triassic ( ; sometimes symbolized 🝈) is a geologic period and system which spans 50.5 million years from the end of the Permian Period 251.902 million years ago ( Mya), to the beginning of the Jurassic Period 201.4 Mya. The Triassic is t ...

and Jurassic

The Jurassic ( ) is a Geological period, geologic period and System (stratigraphy), stratigraphic system that spanned from the end of the Triassic Period million years ago (Mya) to the beginning of the Cretaceous Period, approximately 143.1 Mya. ...

age rocks on lower slopes. Where these reach the coast, cliffs are formed which are cut with ravines and waterfalls. It was recognised as a heritage coast

A heritage coast is a strip of coastline in England and Wales, the extent of which is defined by agreement between the relevant statutory national agency and the relevant local authority. Such areas are recognised for their natural beauty, wildlife ...

in 1991. The highest point on Exmoor is Dunkery Beacon; at it is also the highest point in Somerset. The terrain supports lowland heath communities, ancient woodland

In the United Kingdom, ancient woodland is that which has existed continuously since 1600 in England, Wales and Northern Ireland (or 1750 in Scotland). The practice of planting woodland was uncommon before those dates, so a wood present in 1600 i ...

and blanket mire which provide habitats for scarce flora and fauna. There have also been reports of the Beast of Exmoor

In British folklore and urban legend, British big cats refers to the subject of reported sightings of non-native, wild big cats in the United Kingdom. Many of these creatures have been described as "panthers", "pumas" or "black cats".

There ha ...

, a cryptozoological cat

The cat (''Felis catus''), also referred to as the domestic cat or house cat, is a small domesticated carnivorous mammal. It is the only domesticated species of the family Felidae. Advances in archaeology and genetics have shown that the ...

roaming Exmoor. Several areas have been designated as Nature Conservation Review

''A Nature Conservation Review'' is a two-volume work by Derek Ratcliffe, published by Cambridge University Press in 1977. It set out to identify the most important places for nature conservation in Great Britain. It is often known by the initi ...

and Geological Conservation Review

The Geological Conservation Review (GCR) is produced by the UK's Joint Nature Conservation Committee. It is designed to identify those sites of national and international importance needed to show all the key scientific elements of the geological ...

sites.

There is evidence of human occupation from the Mesolithic

The Mesolithic (Ancient Greek language, Greek: μέσος, ''mesos'' 'middle' + λίθος, ''lithos'' 'stone') or Middle Stone Age is the Old World archaeological period between the Upper Paleolithic and the Neolithic. The term Epipaleolithic i ...

. This developed for agriculture and extraction of mineral ores into the Bronze

Bronze is an alloy consisting primarily of copper, commonly with about 12–12.5% tin and often with the addition of other metals (including aluminium, manganese, nickel, or zinc) and sometimes non-metals (such as phosphorus) or metalloid ...

and Iron Age

The Iron Age () is the final epoch of the three historical Metal Ages, after the Chalcolithic and Bronze Age. It has also been considered as the final age of the three-age division starting with prehistory (before recorded history) and progre ...

s. The remains of standing stones, cairn

A cairn is a human-made pile (or stack) of stones raised for a purpose, usually as a marker or as a burial mound. The word ''cairn'' comes from the (plural ).

Cairns have been and are used for a broad variety of purposes. In prehistory, t ...

s and bridges can still be identified. The royal forest was granted a charter in the 13th century, however foresters who managed the area were identified in the Domesday Book

Domesday Book ( ; the Middle English spelling of "Doomsday Book") is a manuscript record of the Great Survey of much of England and parts of Wales completed in 1086 at the behest of William the Conqueror. The manuscript was originally known by ...

. In the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

sheep farming was common with a system of agistment

Agistment originally referred specifically to the proceeds of pasturage in the king's forests. To agist is, in English law, to take cattle to graze, in exchange for payment (derived, via Anglo-Norman ''agister'', from the Old French ''gîte">g ...

licensing the grazing of livestock as the Inclosure Acts divided up the land. The area is now used for a range of recreational purposes.

National character area

Exmoor has been designated as anational character area

A National Character Area (NCA) is a natural subdivision of England based on a combination of landscape, biodiversity, geodiversity and economic activity. There are 159 National Character Areas and they follow natural, rather than administrative, b ...

(No. 145) by Natural England

Natural England is a non-departmental public body in the United Kingdom sponsored by the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs. It is responsible for ensuring that England's natural environment, including its land, flora and fauna, ...

, the public body responsible for England's natural environment. Neighbouring natural regions include The Culm to the southwest, the Devon Redlands

The Devon Redlands is a natural region in southwest Britain that has been designated as National Character Area (NCA) 148 by Natural England.

to the south and the Vale of Taunton and Quantock Fringes to the east.

Exmoor National Park

Exmoor was designated a National Park in 1954, under the 1949 National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act. The Exmoor National Park is primarily an upland area with a dispersed population living mainly in small villages and hamlets. The largest settlements arePorlock

Porlock is a coastal village in Somerset, England, west of Minehead. At the 2011 census, the village had a population of 1,440.

In 2017, Porlock had the highest percentage of elderly population in England, with over 40% being of pensionable ...

, Dulverton, Lynton, and Lynmouth

Lynmouth is a village in Devon, England, on the northern edge of Exmoor. The village straddles the confluence of the West Lyn River, West Lyn and East Lyn River, East Lyn rivers, in a gorge directly below the neighbouring town of Lynton, w ...

, which together contain almost 40 per cent of the park's population. Lynton and Lynmouth are combined into one parish and are connected by the Lynton and Lynmouth Cliff Railway.

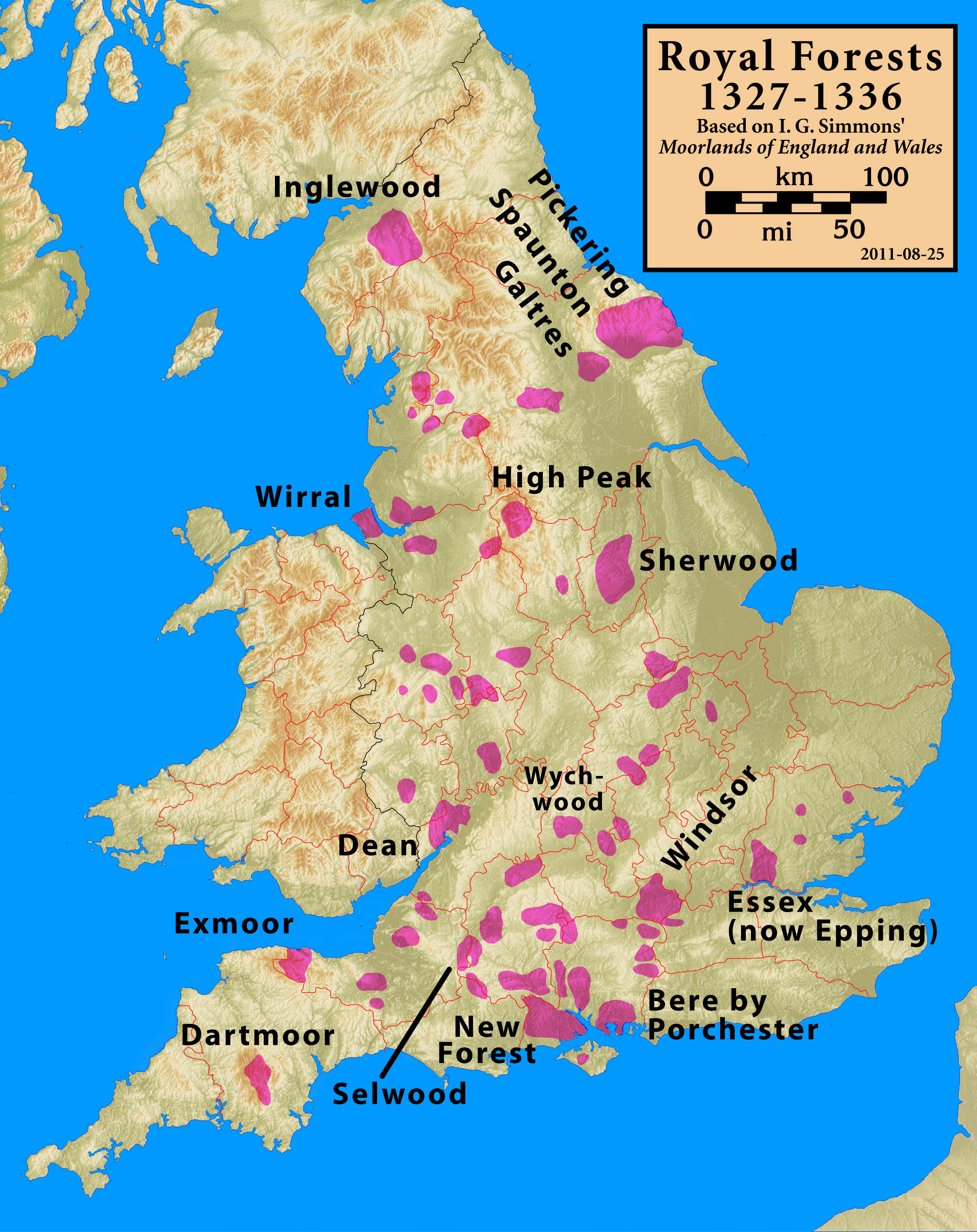

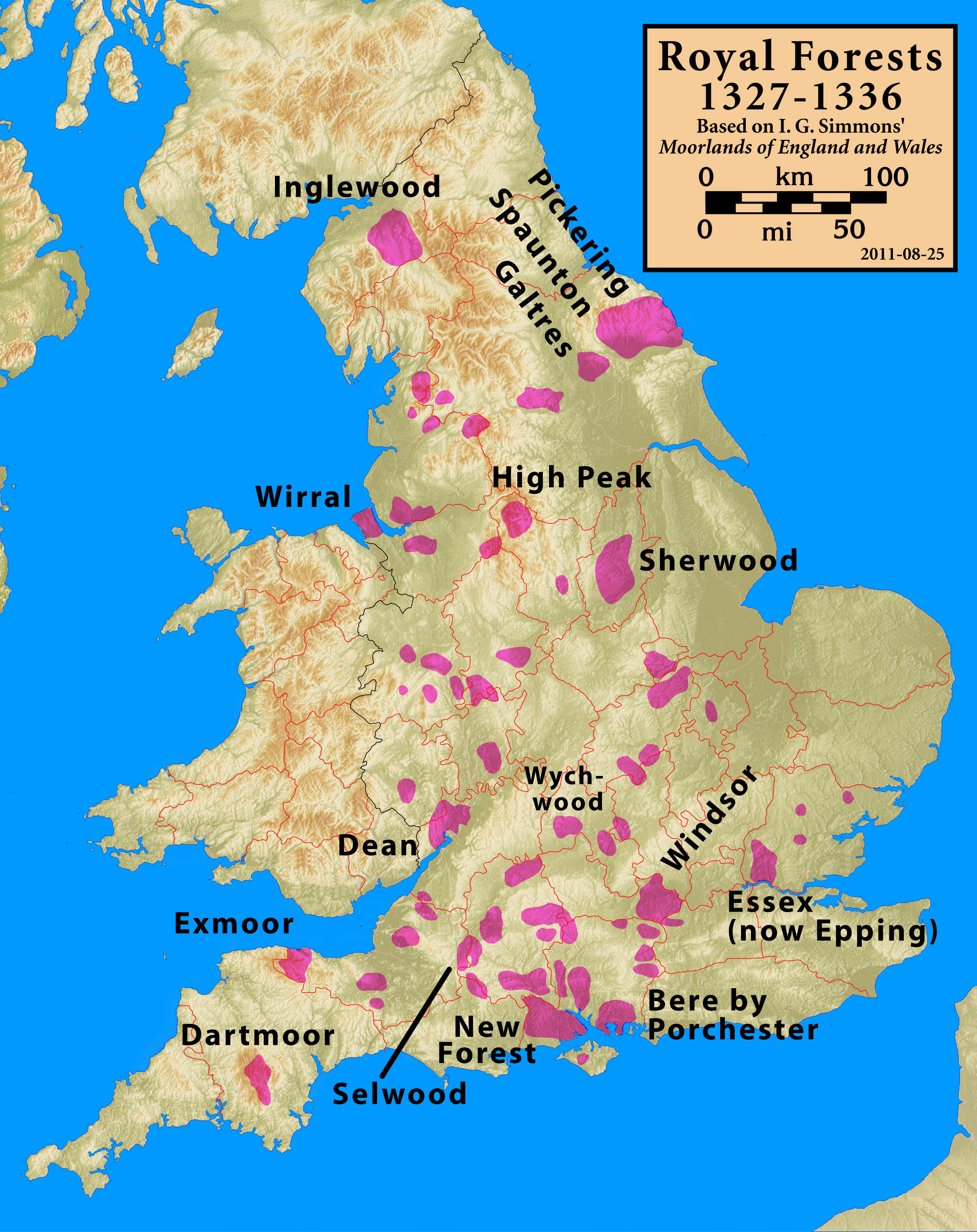

Exmoor was once a royal forest

A royal forest, occasionally known as a kingswood (), is an area of land with different definitions in England, Wales, Scotland and Ireland. The term ''forest'' in the ordinary modern understanding refers to an area of wooded land; however, the ...

and hunting ground, covering , which was sold off in 1818. Several areas within the Exmoor National Park have been declared Sites of Special Scientific Interest

A Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) in Great Britain, or an Area of Special Scientific Interest (ASSI) in the Isle of Man and Northern Ireland, is a conservation designation denoting a protected area in the United Kingdom and Isle ...

due to their flora and fauna. This title earns the site some legal protection from development, damage and neglect. In 1993 an environmentally sensitive area was established within Exmoor. It is known as a perfect place for stargazing. In 2011, it was designated Europe's first International Dark Sky Reserve by the International Dark-Sky Association

DarkSky International, formerly the International Dark-Sky Association (IDA), is a United States–based nonprofit organization incorporated in 1988 by founders David Crawford, a professional astronomer, and Tim Hunter, a physician and amateu ...

.

Geology

Exmoor is an upland area formed almost exclusively fromsedimentary

Sedimentary rocks are types of rock formed by the cementation of sediments—i.e. particles made of minerals (geological detritus) or organic matter (biological detritus)—that have been accumulated or deposited at Earth's surface. Sedime ...

rocks dating from the Devonian

The Devonian ( ) is a period (geology), geologic period and system (stratigraphy), system of the Paleozoic era (geology), era during the Phanerozoic eon (geology), eon, spanning 60.3 million years from the end of the preceding Silurian per ...

and early Carboniferous

The Carboniferous ( ) is a Geologic time scale, geologic period and System (stratigraphy), system of the Paleozoic era (geology), era that spans 60 million years, from the end of the Devonian Period Ma (million years ago) to the beginning of the ...

periods. The name of the geological period

The geologic time scale or geological time scale (GTS) is a representation of time based on the geologic record, rock record of Earth. It is a system of chronological dating that uses chronostratigraphy (the process of relating stratum, strata ...

and system

A system is a group of interacting or interrelated elements that act according to a set of rules to form a unified whole. A system, surrounded and influenced by its open system (systems theory), environment, is described by its boundaries, str ...

, 'Devonian', comes from Devon, as rocks of that age were first studied and described here. With the exception of a suite of Triassic

The Triassic ( ; sometimes symbolized 🝈) is a geologic period and system which spans 50.5 million years from the end of the Permian Period 251.902 million years ago ( Mya), to the beginning of the Jurassic Period 201.4 Mya. The Triassic is t ...

and Jurassic

The Jurassic ( ) is a Geological period, geologic period and System (stratigraphy), stratigraphic system that spanned from the end of the Triassic Period million years ago (Mya) to the beginning of the Cretaceous Period, approximately 143.1 Mya. ...

age rocks forming the lower ground between Porlock and Timberscombe and from Minehead to Yarde (within Exmoor National Park but peripheral to the moor itself), all of the solid rocks of Exmoor are assigned to the Exmoor Group, which comprises a mix of gritstone

Gritstone or grit is a hard, coarse-grained, siliceous sandstone. This term is especially applied to such sandstones that are quarried for building material. British gritstone was used for millstones to mill flour, to grind wood into pulp for ...

s, sandstone

Sandstone is a Clastic rock#Sedimentary clastic rocks, clastic sedimentary rock composed mainly of grain size, sand-sized (0.0625 to 2 mm) silicate mineral, silicate grains, Cementation (geology), cemented together by another mineral. Sand ...

s, slate

Slate is a fine-grained, foliated, homogeneous, metamorphic rock derived from an original shale-type sedimentary rock composed of clay or volcanic ash through low-grade, regional metamorphism. It is the finest-grained foliated metamorphic ro ...

s, shale

Shale is a fine-grained, clastic sedimentary rock formed from mud that is a mix of flakes of Clay mineral, clay minerals (hydrous aluminium phyllosilicates, e.g., Kaolinite, kaolin, aluminium, Al2Silicon, Si2Oxygen, O5(hydroxide, OH)4) and tiny f ...

s, limestone

Limestone is a type of carbonate rock, carbonate sedimentary rock which is the main source of the material Lime (material), lime. It is composed mostly of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different Polymorphism (materials science) ...

, siltstone

Siltstone, also known as aleurolite, is a clastic sedimentary rock that is composed mostly of silt. It is a form of mudrock with a low clay mineral content, which can be distinguished from shale by its lack of fissility.

Although its permeabil ...

s and mudstone

Mudstone, a type of mudrock, is a fine-grained sedimentary rock whose original constituents were clays or muds. Mudstone is distinguished from ''shale'' by its lack of fissility.Blatt, H., and R.J. Tracy, 1996, ''Petrology.'' New York, New York, ...

s. Quartz

Quartz is a hard, crystalline mineral composed of silica (silicon dioxide). The Atom, atoms are linked in a continuous framework of SiO4 silicon–oxygen Tetrahedral molecular geometry, tetrahedra, with each oxygen being shared between two tet ...

and iron

Iron is a chemical element; it has symbol Fe () and atomic number 26. It is a metal that belongs to the first transition series and group 8 of the periodic table. It is, by mass, the most common element on Earth, forming much of Earth's o ...

mineralisation can be detected in outcrops and subsoil

Subsoil is the layer of soil under the topsoil on the surface of the ground. Like topsoil, it is composed of a variable mixture of small particles such as sand, silt and clay, but with a much lower percentage of organic matter and humus. The su ...

. The Glenthorne area demonstrates the Trentishoe Member (formerly 'Formation') of the Hangman Sandstone Formation (formerly 'Group'). The Hangman Sandstone represents the Middle Devonian sequence of North Devon and Somerset. These unusual freshwater deposits in the Hangman Grits were mainly formed in desert conditions. As this area of Britain was not subject to glaciation

A glacial period (alternatively glacial or glaciation) is an interval of time (thousands of years) within an ice age that is marked by colder temperatures and glacier advances. Interglacials, on the other hand, are periods of warmer climate be ...

, the plateau remains as a remarkably old landform. The bedrock and more recent superficial deposits are covered in part by moorland which is supported by wet, acid soil.

Geography

Coastline

Exmoor has of coastline. The highest sea cliff on mainland Britain (if a cliff is defined as having a slope greater than 60 degrees) is Great Hangman nearCombe Martin

Combe Martin () is a village, Civil parishes in England, civil parish and former Manorialism, manor on the North Devon coast about east of Ilfracombe. It is a small seaside resort with a sheltered cove on the northwest edge of the Exmoor Nati ...

at high, with a cliff face of . Its sister cliff is the Little Hangman, which marks the edge of Exmoor. The coastal hills reach a maximum height of at Culbone Hill.

Exmoor's woodlands sometimes reach the shoreline, especially between Porlock and Foreland Point, where they form the single longest stretch of coastal woodland in England and Wales

England and Wales () is one of the Law of the United Kingdom#Legal jurisdictions, three legal jurisdictions of the United Kingdom. It covers the constituent countries England and Wales and was formed by the Laws in Wales Acts 1535 and 1542. Th ...

. The Exmoor Coastal Heaths have been recognised as a Site of Special Scientific Interest due to the diversity of plant species present.

The scenery of rocky headlands, ravines, waterfalls and towering cliffs gained the Exmoor coast recognition as a heritage coast

A heritage coast is a strip of coastline in England and Wales, the extent of which is defined by agreement between the relevant statutory national agency and the relevant local authority. Such areas are recognised for their natural beauty, wildlife ...

in 1991. With its huge waterfalls and caves, this dramatic coastline has become an adventure playground for both climbers and explorers. The cliffs provide one of the longest and most isolated seacliff traverses in the UK. The South West Coast Path

The South West Coast Path is England's longest waymarked Long-distance footpaths in the UK, long-distance footpath and a National Trail. It stretches for , running from Minehead in Somerset, along the coasts of Devon and Cornwall, to Poole Harb ...

, at the longest National Trail

National Trails are long distance footpaths and bridleways in England and Wales. They are administered by Natural England, an agency of the Government of the United Kingdom, UK government, and Natural Resources Wales, a Welsh Government, Welsh ...

in England and Wales, starts at Minehead

Minehead is a coastal town and civil parish in Somerset, England. It lies on the south bank of the Bristol Channel, north-west of the county town of Taunton, from the boundary with the county of Devon and close to the Exmoor National Park. T ...

and runs along all of Exmoor's coast. There are small harbours at Lynmouth, Porlock Weir and Combe Martin. Once crucial to coastal trade, the harbours are now primarily used for pleasure; individually owned sailing boats and non-commercial fishing boats are often found in the harbours. The Valley of Rocks beyond Lynton is a deep dry valley that runs parallel to the nearby sea and is capped on the seaward side by large rocks, and Sexton's Burrows forms a natural breakwater to the harbour of Watermouth

Watermouth is a sheltered bay and Hamlet (place), hamlet between Hele Bay and Combe Martin on the North Devon coast of England. The settlement's castle, named as Watermouth Castle, is currently used being as a theme park. Watermouth harbour is ...

Bay on the coast.

Rivers

The high ground forms thecatchment area

A catchment area in human geography, is the area from which a location, such as a city, service or institution, attracts a population that uses its services and economic opportunities. Catchment areas may be defined based on from where people are ...

for numerous rivers and streams. There are about of named rivers on Exmoor. The River Exe

The River Exe ( ) is a river in England that source (river), rises at Exe Head, near the village of Simonsbath, on Exmoor in Somerset, from the Bristol Channel coast, but flows more or less directly due south, so that most of its length lie ...

, after which Exmoor is named, rises at Exe Head near the village of Simonsbath

Simonsbath () is a small village high on Exmoor in the England, English ceremonial county, county of Somerset. It is the principal settlement in the Exmoor civil parish, which is the largest and most sparsely populated civil parish on Exmoo ...

, close to the Bristol Channel

The Bristol Channel (, literal translation: "Severn Sea") is a major inlet in the island of Great Britain, separating South Wales (from Pembrokeshire to the Vale of Glamorgan) and South West England (from Devon to North Somerset). It extends ...

coast, but flows more or less directly due south, so that most of its length lies in Devon

Devon ( ; historically also known as Devonshire , ) is a ceremonial county in South West England. It is bordered by the Bristol Channel to the north, Somerset and Dorset to the east, the English Channel to the south, and Cornwall to the west ...

. It reaches the sea at a substantial ria (estuary

An estuary is a partially enclosed coastal body of brackish water with one or more rivers or streams flowing into it, and with a free connection to the open sea. Estuaries form a transition zone between river environments and maritime enviro ...

) on the south (English Channel

The English Channel, also known as the Channel, is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that separates Southern England from northern France. It links to the southern part of the North Sea by the Strait of Dover at its northeastern end. It is the busi ...

) coast of Devon. It has several tributaries which arise on Exmoor. The River Barle runs from northern Exmoor to join the River Exe at Exebridge, Devon. The river and the Barle Valley are both designated as biological Sites of Special Scientific Interest. Another tributary, the River Haddeo, flows from the Wimbleball Lake.

Most other rivers arising on Exmoor flow north to the Bristol Channel. These include the River Heddon, which runs along the western edges of Exmoor, reaching the North Devon coast at Heddon's Mouth, and the East

East is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from west and is the direction from which the Sun rises on the Earth.

Etymology

As in other languages, the word is formed from the fact that ea ...

and West Lyn rivers, which meet at Watersmeet immediately east of Lynmouth. Hoar Oak Water is a moorland tributary of the East Lyn River which also has its confluence there. The River Horner, which is also known as Horner Water, rises near Luccombe and flows into Porlock Bay near Hurlstone Point. The River Mole arises on the south-western flanks of Exmoor and is the major tributary of the River Taw

The River Taw () in England rises at Taw Head, a spring on the central northern flanks of Dartmoor, crosses North Devon and at the town of Barnstaple, formerly a significant port, empties into Barnstaple Bay in the Bristol Channel, having form ...

, which itself flows northward from Dartmoor

Dartmoor is an upland area in southern Devon, South West England. The moorland and surrounding land has been protected by National Park status since 1951. Dartmoor National Park covers .

The granite that forms the uplands dates from the Carb ...

. Badgworthy Water

Badgworthy Water is a small river which flows through Malmsmead on Exmoor, close to the border between Devon and Somerset, England.

It merges with Oare Water to become the East Lyn River.

On the banks of the river are the remains of a few dw ...

is one of the small rivers running north to the coast and is associated with the Lorna Doone legends.

Climate

Along with the rest ofSouth West England

South West England, or the South West of England, is one of the nine official regions of England, regions of England in the United Kingdom. Additionally, it is one of four regions that altogether make up Southern England. South West England con ...

, Exmoor has a temperate climate

In geography, the temperate climates of Earth occur in the middle latitudes (approximately 23.5° to 66.5° N/S of the Equator), which span between the tropics and the polar regions of Earth. These zones generally have wider temperature ra ...

which is generally wetter and milder than the rest of England. The mean annual temperature at Simonsbath is with a season

A season is a division of the year based on changes in weather, ecology, and the number of daylight hours in a given region. On Earth, seasons are the result of the axial parallelism of Earth's axial tilt, tilted orbit around the Sun. In temperat ...

al and diurnal variation, but due to the modifying effect of the sea the range is less than in most other parts of the UK. January is the coldest month, with mean minimum temperatures between . July and August are the warmest months in the region, with mean daily maxima around . In general, December is the month with the least sunshine and June the month with the most sun. The south-west of England has a favoured location with regard to the Azores

The Azores ( , , ; , ), officially the Autonomous Region of the Azores (), is one of the two autonomous regions of Portugal (along with Madeira). It is an archipelago composed of nine volcanic islands in the Macaronesia region of the North Atl ...

high pressure when it extends its influence north-eastwards towards the UK, particularly in summer.

Cloud

In meteorology, a cloud is an aerosol consisting of a visible mass of miniature liquid droplets, frozen crystals, or other particles, suspended in the atmosphere of a planetary body or similar space. Water or various other chemicals may ...

often forms inland, especially near hills, and reduce the amount of sunshine that reaches the park. The average annual sunshine is about 1,600 hours. Rainfall

Rain is a form of precipitation where water droplets that have condensed from atmospheric water vapor fall under gravity. Rain is a major component of the water cycle and is responsible for depositing most of the fresh water on the Earth. ...

tends to be associated with Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, with an area of about . It covers approximately 17% of Earth's surface and about 24% of its water surface area. During the Age of Discovery, it was known for se ...

depressions or with convection. In summer, convection, caused by the sun heating the land surface more than the sea, sometimes forms rain cloud

In meteorology, a cloud is an aerosol consisting of a visible mass of miniature liquid droplets, frozen crystals, or other particles, suspended in the atmosphere of a planetary body or similar space. Water or various other chemicals may ...

s and at that time of year a large proportion of the rainfall comes from showers and thunderstorm

A thunderstorm, also known as an electrical storm or a lightning storm, is a storm characterized by the presence of lightning and its acoustics, acoustic effect on the Earth's atmosphere, known as thunder. Relatively weak thunderstorm ...

s. Annual precipitation varies from in the east of the park to over at The Chains. However, in the 24 hours of 16 August 1952, more than of rain fell at The Chains. This rainfall, which followed an exceptionally wet summer, led to disastrous flooding in Lynmouth with 34 dead and extensive damage to the small town.

Snow

Snow consists of individual ice crystals that grow while suspended in the atmosphere—usually within clouds—and then fall, accumulating on the ground where they undergo further changes.

It consists of frozen crystalline water througho ...

fall is very variable from year to year and ranges from 23 days on the high moors to about 6 on coastal areas. November to March have the highest mean wind speeds, with June to August having the lightest winds. The wind comes mostly from the south-west.

There are two Met Office Weather stations recording climate data within Exmoor: Liscombe and Nettlecombe.

History

There is evidence of occupation of the area by people fromMesolithic

The Mesolithic (Ancient Greek language, Greek: μέσος, ''mesos'' 'middle' + λίθος, ''lithos'' 'stone') or Middle Stone Age is the Old World archaeological period between the Upper Paleolithic and the Neolithic. The term Epipaleolithic i ...

times onward. In the Neolithic

The Neolithic or New Stone Age (from Ancient Greek, Greek 'new' and 'stone') is an archaeological period, the final division of the Stone Age in Mesopotamia, Asia, Europe and Africa (c. 10,000 BCE to c. 2,000 BCE). It saw the Neolithic Revo ...

period, people started to manage animals and grow crops on farms cleared from the woodland, rather than act purely as hunters and as gatherers. It is also likely that extraction and smelting of mineral ores to make metal tools, weapons, containers and ornaments started in the late Neolithic, and continued into the Bronze

Bronze is an alloy consisting primarily of copper, commonly with about 12–12.5% tin and often with the addition of other metals (including aluminium, manganese, nickel, or zinc) and sometimes non-metals (such as phosphorus) or metalloid ...

and Iron Age

The Iron Age () is the final epoch of the three historical Metal Ages, after the Chalcolithic and Bronze Age. It has also been considered as the final age of the three-age division starting with prehistory (before recorded history) and progre ...

s. An earthen ring at Parracombe is believed to be a Neolithic henge

A henge can be one of three related types of Neolithic Earthworks (archaeology), earthwork. The essential characteristic of all three is that they feature a ring-shaped bank and ditch, with the ditch inside the bank. Because the internal ditches ...

dating from 5000–4000 BC, and Cow Castle, which is where White Water meets the River Barle, is an Iron Age fort at the top of a conical hill.

Tarr Steps are a prehistoric

Prehistory, also called pre-literary history, is the period of human history between the first known use of stone tools by hominins million years ago and the beginning of recorded history with the invention of writing systems. The use o ...

( 1000 BC) clapper bridge across the River Barle, about south-east of Withypool

Withypool (formerly Widepolle, Widipol, Withypoole) is a small village and former civil parish, now in the parish of Withypool and Hawkridge, in the Somerset (district), Somerset district, in the ceremonial county of Somerset, England, near the ...

and north-west of Dulverton. The stone slabs weigh up to 5 tonnes apiece, and the bridge has been designated by English Heritage

English Heritage (officially the English Heritage Trust) is a charity that manages over 400 historic monuments, buildings and places. These include prehistoric sites, a battlefield, medieval castles, Roman forts, historic industrial sites, Lis ...

as a grade I listed building

In the United Kingdom, a listed building is a structure of particular architectural or historic interest deserving of special protection. Such buildings are placed on one of the four statutory lists maintained by Historic England in England, Hi ...

, to recognise its special architectural, historical or cultural significance. There is little evidence of Roman occupation apart from two fortlets on the coast. Lanacombe is the site of several standing stones and cairn

A cairn is a human-made pile (or stack) of stones raised for a purpose, usually as a marker or as a burial mound. The word ''cairn'' comes from the (plural ).

Cairns have been and are used for a broad variety of purposes. In prehistory, t ...

s which have been scheduled as ancient monument

An ancient monument can refer to any early or historical manmade structure or architecture. Certain ancient monuments are of cultural importance for nations and become symbols of international recognition, including the Baalbek, ruins of Baalbek ...

s. The stone settings are between and high. A series of Bronze Age stone cairns are closely associated with the standing stones.

Holwell Castle, at Parracombe, was a Norman motte-and-bailey castle

A motte-and-bailey castle is a European fortification with a wooden or stone keep situated on a raised area of ground called a motte, accompanied by a walled courtyard, or bailey, surrounded by a protective ditch and palisade. Relatively easy ...

built to guard the junction of the east–west and north–south trade routes, enabling movement of people and goods and the growth of the population. Alternative explanations for its construction suggest it may have been constructed to obtain taxes at the River Heddon bridging place, or to protect and supervise silver

Silver is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol Ag () and atomic number 47. A soft, whitish-gray, lustrous transition metal, it exhibits the highest electrical conductivity, thermal conductivity, and reflectivity of any metal. ...

mining in the area around Combe Martin. It was in diameter and high above the bottom of a rock cut ditch which is deep. It was built, in the late 11th or early 12th century. The earthworks of the castle are still clearly visible from a nearby footpath, but there is no public access to them.

Establishment of royal forest

According to the late 13th-century

According to the late 13th-century Hundred Rolls {{Short description, 13th-century census of England and Wales

The Hundred Rolls are a census of England and parts of what is now Wales taken in the late thirteenth century. Often considered an attempt to produce a second Domesday Book, they are na ...

, King Henry II of England

Henry II () was King of England

The monarchy of the United Kingdom, commonly referred to as the British monarchy, is the form of government used by the United Kingdom by which a hereditary monarch reigns as the head of state, with the ...

(d. 1189) gave William of Wrotham the office of steward of Exmoor. The terms steward, warden and forester appear to be synonymous for the king's chief officer of the royal forest.

Wardens

The first recorded wardens were Dodo, Almer & Godric who were named in theDomesday Book

Domesday Book ( ; the Middle English spelling of "Doomsday Book") is a manuscript record of the Great Survey of much of England and parts of Wales completed in 1086 at the behest of William the Conqueror. The manuscript was originally known by ...

(1086) as "foresters of Widepolla", Withypool

Withypool (formerly Widepolle, Widipol, Withypoole) is a small village and former civil parish, now in the parish of Withypool and Hawkridge, in the Somerset (district), Somerset district, in the ceremonial county of Somerset, England, near the ...

having been the ancient capital of the forest. The family of Denys were associated with Ilchester and "Petherton". William of Wrotham, who died in 1217, was steward of the forests of Exmoor and North Petherton, Somerset. Walter and Robert were named as foresters of Exmoor when they witnessed an early 13th-century grant to Forde Abbey. In 1276 the jurors of Brushford manor made a complaint about John de Camera in the Court of Exchequer in which he was described as forester of Exmoor.For an explanation of the Duke of York's tenure, inherited from the Mortimers, seHamilton, Archibald. The Red Deer of Exmoor, 1906, Chapter 12, The Forest of Exmoor under the Plantagenets and Tudors

, pp.190–210 William Lucar of "Wythecomb", the brother of Elizabeth Lucar, was forester ''temp.'' under Henry VI, between 1422 and 1461. William de Botreaux, 3rd Baron Botreaux was appointed in 1435 warden of the forests of Exmoor and Neroche for life by Richard Duke of York. The Botreaux family had long held the manor of Molland at the southern edge of Exmoor, but were probably resident mainly at North Cadbury in Somerset. On 10 May 1461 William Bourchier, 9th Baron FitzWarin, feudal baron of Bampton was appointed by King Edward IV as Master Forester of the Forests of Exmoor and Neroche for life. Sir John Poyntz of Iron Acton, Gloucestershire, was warden or chief forester of Exmoor in 1568 when he brought an action in the Court of Exchequer against Henry Rolle (of Heanton Satchville, Petrockstowe), the powerful lord of the manors of Exton, Hawkridge and Withypool. In 1608 Sir Hugh Pollard was named as chief forester in a suit brought before the Court of Exchequer by his deputy William Pincombe.

James Butler, 1st Duke of Ormonde

Lieutenant general, Lieutenant-General James FitzThomas Butler, 1st Duke of Ormond, Knight of the Garter, KG, Privy Council of England, PC (19 October 1610 – 21 July 1688), was an Anglo-Irish statesman and soldier, known as Earl of Ormond fr ...

, was named as Keeper of Exmoor Forest in 1660 and 1661. James Boevey

James Boevey (1622–1696) (pronounced "Boovey") was an English merchant, lawyer and philosopher of Huguenot parentage.

Origins

He was born in London at 6 a.m. on 7 May 1622 in Mincing Lane, in the parish of St. Dunstan-in-the-East. He was the ...

was a forester in the 17th century. Sir Richard Acland (or possibly Sir Thomas Dyke Acland) was the last forester up to 1818. One of the roles of the Warden was Master of Staghounds and this role continued to be exercised by the Master of the Devon and Somerset Staghounds

The red deer of Exmoor have been hunted since Norman times, when Exmoor was declared a Royal Forest. Collyns stated the earliest record of a pack of Staghounds on Exmoor was 1598. In 1803, the "North Devon Staghounds" became a subscription pack. ...

, a position extant today. By 1820 the royal forest had been divided up. A quarter of the forest, , was sold to John Knight (1765–1850) in 1818. This section comprises the present Exmoor Parish, whose parish church is situated in Simonsbath.

Wool trade

The parish of Exmoor Forest was part of the Hundred of Williton and Freemanners. During theMiddle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

, sheep farming for the wool trade came to dominate the economy. The wool was spun into thread on isolated farms and collected by merchants to be woven, fulled, dyed and finished in thriving towns such as Dunster. The land started to be enclosed and from the 17th century onwards larger estates developed, leading to establishment of areas of large regular shaped fields. During the 16th and 17th centuries the commons were overstocked with agisted livestock, from farmers outside the immediate area who were charged for the privilege. This led to disputes about the number of animals allowed and the enclosure

Enclosure or inclosure is a term, used in English landownership, that refers to the appropriation of "waste" or "common land", enclosing it, and by doing so depriving commoners of their traditional rights of access and usage. Agreements to enc ...

of land. In the mid-17th century James Boevey was the warden. The house that he built at Simonsbath

Simonsbath () is a small village high on Exmoor in the England, English ceremonial county, county of Somerset. It is the principal settlement in the Exmoor civil parish, which is the largest and most sparsely populated civil parish on Exmoo ...

was the only one in the forest for 150 years. When the royal forest was sold off in 1818, John Knight bought the Simonsbath House and the accompanying farm for £50,000. He set about converting the royal forest into agricultural land. He and his family also built most of the large farms in the central section of the moor as well as of metalled access roads to Simonsbath and a wall around his estate, much of which still survives.

In the mid-19th century a mine was developed alongside the River Barle. The mine was originally called Wheal Maria, then changed to Wheal Eliza. It was a copper

Copper is a chemical element; it has symbol Cu (from Latin ) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pinkish-orang ...

mine from 1845 to 1854 and then an iron mine until 1857, although the first mining activity on the site may be from 1552. At Simonsbath, a restored Victorian water-powered sawmill, which was damaged in the floods of 1992, has now been purchased by the National Park and returned to working order; it is now used to make the footpath signs, gates, stiles and bridges for various sites in the park.

Ecology

In addition to the Exmoor Coastal Heaths Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI), two other areas are specifically designated. North Exmoor covers and includes the Dunkery Beacon and the Holnicote and Horner Water

In addition to the Exmoor Coastal Heaths Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI), two other areas are specifically designated. North Exmoor covers and includes the Dunkery Beacon and the Holnicote and Horner Water Nature Conservation Review

''A Nature Conservation Review'' is a two-volume work by Derek Ratcliffe, published by Cambridge University Press in 1977. It set out to identify the most important places for nature conservation in Great Britain. It is often known by the initi ...

sites, and the Chains Geological Conservation Review

The Geological Conservation Review (GCR) is produced by the UK's Joint Nature Conservation Committee. It is designed to identify those sites of national and international importance needed to show all the key scientific elements of the geological ...

site. The Chains site is nationally important for its south-western lowland heath communities and for transitions from Ancient woodland

In the United Kingdom, ancient woodland is that which has existed continuously since 1600 in England, Wales and Northern Ireland (or 1750 in Scotland). The practice of planting woodland was uncommon before those dates, so a wood present in 1600 i ...

through upland heath to blanket mire. The site is also of importance for its breeding bird communities, its large population of the nationally rare heath fritillary (''Mellicta athalia''), an exceptional woodland lichen

A lichen ( , ) is a hybrid colony (biology), colony of algae or cyanobacteria living symbiotically among hypha, filaments of multiple fungus species, along with yeasts and bacteria embedded in the cortex or "skin", in a mutualism (biology), m ...

flora

Flora (: floras or florae) is all the plant life present in a particular region or time, generally the naturally occurring (indigenous (ecology), indigenous) native plant, native plants. The corresponding term for animals is ''fauna'', and for f ...

and its palynological interest of deep peat on the Chains.

The South Exmoor SSSI is smaller, covering and including the River Barle and its tributaries with submerged plants such as alternate water-milfoil (''Myriophyllum alterniflorum''). There are small areas of semi-natural woodland within the site, including some which are ancient. The most abundant tree species is sessile oak (''Quercus petraea''), the shrub layer is very sparse and the ground flora includes bracken

Bracken (''Pteridium'') is a genus of large, coarse ferns in the family (biology), family Dennstaedtiaceae. Ferns (Pteridophyta) are vascular plants that undergo alternation of generations, having both large plants that produce spores and small ...

, bilberry

Bilberries () are Eurasian low-growing shrubs in the genus ''Vaccinium'' in the flowering plant family Ericaceae that bear edible, dark blue berries. They resemble but are distinct from North American blueberries.

The species most often referre ...

and a variety of mosses. The heaths have strong breeding populations of birds, including whinchat (''Saxicola rubetra'') and European stonechat (''Saxicola rubicola''). Wheatear (''Oenanthe oenanthe'') are common near stone boundary walls and other stony places. Grasshopper warbler (''Locustella naevia'') breed in scrub and tall heath. Trees on the moorland edges provide nesting sites for Lesser redpoll (''Acanthis cabaret''), common buzzard

The common buzzard (''Buteo buteo'') is a medium-to-large bird of prey which has a large range. It is a member of the genus '' Buteo'' in the family Accipitridae. The species lives in most of Europe and extends its breeding range across much of ...

(''Buteo buteo'') and raven

A raven is any of several large-bodied passerine bird species in the genus '' Corvus''. These species do not form a single taxonomic group within the genus. There is no consistent distinction between crows and ravens; the two names are assigne ...

(''Corvus corax'').

Flora

Uncultivatedheath

A heath () is a shrubland habitat found mainly on free-draining infertile, acidic soils and is characterised by open, low-growing woody vegetation. Moorland is generally related to high-ground heaths with—especially in Great Britain—a coole ...

and moorland cover about a quarter of Exmoor landscape. Some moors are covered by a variety of grass

Poaceae ( ), also called Gramineae ( ), is a large and nearly ubiquitous family (biology), family of monocotyledonous flowering plants commonly known as grasses. It includes the cereal grasses, bamboos, the grasses of natural grassland and spe ...

es and sedges

The Cyperaceae () are a family of graminoid (grass-like), monocotyledonous flowering plants known as sedges. The family is large; botanists have described some 5,500 known species in about 90 generathe largest being the "true sedges" (genu ...

, while others are dominated by heather. There are also cultivated areas including the Brendon Hills

The Brendon Hills are a range of hills in west Somerset, England. The hills merge level into the eastern side of Exmoor and are included within the Exmoor National Park. The highest point of the range is Lype Hill at above sea level with a sec ...

, which lie in the east of the National Park. There are also of Forestry Commission

The Forestry Commission is a non-ministerial government department responsible for the management of publicly owned forests and the regulation of both public and private forestry in England.

The Forestry Commission was previously also respons ...

woodland, comprising a mixture of broad-leaved (oak

An oak is a hardwood tree or shrub in the genus ''Quercus'' of the beech family. They have spirally arranged leaves, often with lobed edges, and a nut called an acorn, borne within a cup. The genus is widely distributed in the Northern Hemisp ...

, ash and hazel

Hazels are plants of the genus ''Corylus'' of deciduous trees and large shrubs native to the temperate Northern Hemisphere. The genus is usually placed in the birch family, Betulaceae,Germplasmgobills Information Network''Corylus''Rushforth, K ...

) and conifer

Conifers () are a group of conifer cone, cone-bearing Spermatophyte, seed plants, a subset of gymnosperms. Scientifically, they make up the phylum, division Pinophyta (), also known as Coniferophyta () or Coniferae. The division contains a sin ...

trees. Horner Woodlands and Tarr Steps woodlands are prime examples. The country's highest beech tree, above sea level, is at Birch Cleave at Simonsbath but beech in hedgebanks grow up to . At least two species of whitebeam

The whitebeams are members of the family Rosaceae, tribe Malinae, comprising a number of deciduous simple or lobe-leaved species formerly lumped together within ''Sorbus'' s.l. Many whitebeams are the result of extensive intergeneric hybridisa ...

: '' Sorbus subcuneata'' and Sorbus 'Taxon D' are unique to Exmoor. These woodlands are home to lichens, moss

Mosses are small, non-vascular plant, non-vascular flowerless plants in the taxonomic phylum, division Bryophyta (, ) ''sensu stricto''. Bryophyta (''sensu lato'', Wilhelm Philippe Schimper, Schimp. 1879) may also refer to the parent group bryo ...

es and fern

The ferns (Polypodiopsida or Polypodiophyta) are a group of vascular plants (plants with xylem and phloem) that reproduce via spores and have neither seeds nor flowers. They differ from mosses by being vascular, i.e., having specialized tissue ...

s. Exmoor is the only national location for the lichens ''Biatoridium delitescens'', ''Rinodina fimbriata'' and ''Rinodina flavosoralifera'', the latter having been found only on one individual tree.

In 2024, plans were unveiled to plant approximately 38,000 trees near the sea on Exmoor as part of a larger initiative led by the National Trust

The National Trust () is a heritage and nature conservation charity and membership organisation in England, Wales and Northern Ireland.

The Trust was founded in 1895 by Octavia Hill, Sir Robert Hunter and Hardwicke Rawnsley to "promote the ...

to plant over 100,000 trees in northern Devon, aimed at supporting Celtic rainforests. Among the species earmarked for planting is the nearly extinct Devon whitebeam, a tree found only in England's West Country

The West Country is a loosely defined area within southwest England, usually taken to include the counties of Cornwall, Devon, Dorset, Somerset and Bristol, with some considering it to extend to all or parts of Wiltshire, Gloucestershire and ...

and in Ireland

Ireland (, ; ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe. Geopolitically, the island is divided between the Republic of Ireland (officially Names of the Irish state, named Irelan ...

. It can reproduce without fertilization and once had its edible fruit sold as "sorb apples" in Devon markets.

Fauna

Sheep

Sheep (: sheep) or domestic sheep (''Ovis aries'') are a domesticated, ruminant mammal typically kept as livestock. Although the term ''sheep'' can apply to other species in the genus '' Ovis'', in everyday usage it almost always refers to d ...

have grazed on the moors for more than 3,000 years, shaping much of the Exmoor landscape by feeding on moorland grasses and heather. Traditional breeds include Exmoor Horn, Cheviot and Whiteface Dartmoor and Greyface Dartmoor sheep. North Devon cattle are also farmed in the area. Exmoor ponies can be seen roaming freely on the moors. They are a landrace

A landrace is a Domestication, domesticated, locally adapted, often traditional variety of a species of animal or plant that has developed over time, through adaptation to its natural and cultural Environment (biophysical), environment of agric ...

rather than a breed

A breed is a specific group of breedable domestic animals having homogeneous appearance (phenotype), homogeneous behavior, and/or other characteristics that distinguish it from other organisms of the same species. In literature, there exist seve ...

of pony, and may be the closest breed to wild horse

The wild horse (''Equus ferus'') is a species of the genus Equus (genus), ''Equus'', which includes as subspecies the modern domestication of the horse, domesticated horse (''Equus ferus caballus'') as well as the Endangered species, endangered ...

s remaining in Europe; they are also one of the oldest breeds of pony in the world. The ponies are rounded up once a year to be marked and checked over. In 1818 Sir Thomas Acland, the last warden of Exmoor, took thirty ponies and established the Acland Herd, now known as the Anchor Herd, whose direct descendants still roam the moor. In the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

the moor became a training ground, and the breed was nearly killed off, with only 50 ponies surviving the war. The ponies are classified as endangered by the Rare Breeds Survival Trust

The Rare Breeds Survival Trust is a conservation (ethic), conservation charity whose purpose is to secure the continued existence and viability of the native farm animal genetic resources (FAnGR) of the United Kingdom. It was founded in 1973 b ...

, with only 390 breeding females left in the UK. In 2006 a Rural Enterprise Grant, administered locally by the South West Rural Development Service, was obtained to create a new Exmoor Pony Centre at Ashwick, at a disused farm with of land with a further of moorland.

Red deer

The red deer (''Cervus elaphus'') is one of the largest deer species. A male red deer is called a stag or Hart (deer), hart, and a female is called a doe or hind. The red deer inhabits most of Europe, the Caucasus Mountains region, Anatolia, Ir ...

have a stronghold on the moor and can be seen on quiet hillsides in remote areas, particularly in the early morning. The Emperor of Exmoor, a red stag (''Cervus elaphus''), was Britain's largest known wild land animal, until it was killed in October 2010.Exmoor, Emperor Stag, shot dead.

The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in Manchester in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'' and changed its name in 1959, followed by a move to London. Along with its sister paper, ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardi ...

, 25 October 2010. The moorland

Moorland or moor is a type of Habitat (ecology), habitat found in upland (geology), upland areas in temperate grasslands, savannas, and shrublands and the biomes of montane grasslands and shrublands, characterised by low-growing vegetation on So ...

habitat is also home to hundreds of species of bird

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class (biology), class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the Oviparity, laying of Eggshell, hard-shelled eggs, a high Metabolism, metabolic rate, a fou ...

s and insect

Insects (from Latin ') are Hexapoda, hexapod invertebrates of the class (biology), class Insecta. They are the largest group within the arthropod phylum. Insects have a chitinous exoskeleton, a three-part body (Insect morphology#Head, head, ...

s. Birds seen on the moor include merlin

The Multi-Element Radio Linked Interferometer Network (MERLIN) is an interferometer array of radio telescopes spread across England. The array is run from Jodrell Bank Observatory in Cheshire by the University of Manchester on behalf of UK Re ...

, peregrine falcon

The peregrine falcon (''Falco peregrinus''), also known simply as the peregrine, is a Cosmopolitan distribution, cosmopolitan bird of prey (raptor) in the family (biology), family Falconidae renowned for its speed. A large, Corvus (genus), cro ...

, Eurasian curlew

The Eurasian curlew or common curlew (''Numenius arquata'') is a very large wader in the family Scolopacidae. It is one of the most widespread of the curlews, breeding across temperate Europe and Asia. In Europe, this species is often referred ...

, European stonechat, dipper

Dippers are members of the genus ''Cinclus'' in the bird family Cinclidae, so-called because of their bobbing or dipping movements. They are unique among passerines for their ability to dive and swim underwater.

Taxonomy

The genus ''Cinclus'' ...

, Dartford warbler

The Dartford warbler (''Curruca undata'') is a typical warbler from the warmer parts of western Europe and northwestern Africa. It is a small warbler with a long thin tail and a thin pointed bill. The adult male has grey-brown upperparts and is d ...

and ring ouzel. Black grouse

The black grouse (''Lyrurus tetrix''), also known as northern black grouse, Eurasian black grouse, blackgame or blackcock, is a large Aves, bird in the grouse family. It is a Bird migration, sedentary species, spanning across the Palearctic in m ...

and red grouse

The red grouse (''Lagopus scotica'') is a medium-sized bird of the grouse family which is found in Calluna, heather moorland in Great Britain and Ireland.

It was formerly classified as a subspecies of the willow ptarmigan (''Lagopus lagopus'') ...

are now extinct

Extinction is the termination of an organism by the death of its Endling, last member. A taxon may become Functional extinction, functionally extinct before the death of its last member if it loses the capacity to Reproduction, reproduce and ...

on Exmoor, probably as a result of a reduction in habitat management, and for the former species, an increase in visitor pressure.

Beast

TheBeast of Exmoor

In British folklore and urban legend, British big cats refers to the subject of reported sightings of non-native, wild big cats in the United Kingdom. Many of these creatures have been described as "panthers", "pumas" or "black cats".

There ha ...

is a cryptozoological cat

The cat (''Felis catus''), also referred to as the domestic cat or house cat, is a small domesticated carnivorous mammal. It is the only domesticated species of the family Felidae. Advances in archaeology and genetics have shown that the ...

(see phantom cat) that is reported to roam Exmoor. There have been numerous reports of eyewitness sightings. The BBC calls it "the famous-yet-elusive beast of Exmoor". Sightings were first reported in the 1970s although it became notorious in 1983, when a South Molton farmer claimed to have lost over 100 sheep in the space of three months, all of them apparently killed by violent throat injuries. In response to these reports Royal Marine Commandos were deployed from bases in the West Country to watch for the mythical beast from covert observation points. After 6 months no sightings had been made by the Royal Marines and the deployments were ended. Descriptions of its colouration range from black to tan or dark grey. It is possibly a cougar

The cougar (''Puma concolor'') (, ''Help:Pronunciation respelling key, KOO-gər''), also called puma, mountain lion, catamount and panther is a large small cat native to the Americas. It inhabits North America, North, Central America, Cent ...

or black leopard

The leopard (''Panthera pardus'') is one of the five extant cat species in the genus ''Panthera''. It has a pale yellowish to dark golden fur with dark spots grouped in rosettes. Its body is slender and muscular reaching a length of with a ...

which was released after a law was passed in 1976 making it illegal for them to be kept in captivity outside zoos. In 2006, the British Big Cats Society reported that a skull found by a Devon farmer was that of a puma; however, the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs

The Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) is a Departments of the Government of the United Kingdom, ministerial department of the government of the United Kingdom. It is responsible for environmental quality, environmenta ...

(Defra) states, "Based on the evidence, Defra does not believe that there are big cats living in the wild in England."

Government and politics

National Trust

The National Trust () is a heritage and nature conservation charity and membership organisation in England, Wales and Northern Ireland.

The Trust was founded in 1895 by Octavia Hill, Sir Robert Hunter and Hardwicke Rawnsley to "promote the ...

, which owns over 10% of the land, and the National Park Authority, which owns about 7%. Other areas are owned by the Forestry Commission

The Forestry Commission is a non-ministerial government department responsible for the management of publicly owned forests and the regulation of both public and private forestry in England.

The Forestry Commission was previously also respons ...

, Crown Estate

The Crown Estate is a collection of lands and holdings in the United Kingdom belonging to the British monarch as a corporation sole, making it "the sovereign's public estate", which is neither government property nor part of the monarch's priva ...

and Water Companies. The largest private landowner is the ''Badgworthy Land Company'', which represents hunting interests.

From 1954 on, local government was the responsibility of the district and county councils, which remain responsible for the social and economic well-being of the local community. Since 1997 the Exmoor National Park Authority, which is known as a 'single purpose' authority, has taken over some functions to meet its aims to "conserve and enhance the natural beauty, wildlife and cultural heritage of the National Parks" and "promote opportunities for the understanding and enjoyment of the special qualities of the parks by the public", including responsibility for the conservation of the historic environment.

The Park Authority receives 80% of its funding as a direct grant from the government. The Park Authority Committee consists of members from parish and county councils, and six appointed by the Secretary of State. The work is carried out by 80 staff including rangers, volunteers and a team of estate workers who carry out a wide range of tasks including maintaining the many miles of rights of way, hedge laying, fencing, swaling, walling, invasive weed control and habitat management on National Park Authority land. There are ongoing debates between the authority and farmers over the biological monitoring of SSSIs, showing the need for a controlled regime of grazing and burning; farmers claim that these regimes are not practical or effective in the long term.

The National Park Authority operates CareMoor for Exmoor as an opportunity for those that appreciate the area to give back, with donations supporting conservation and access projects.

Sport and recreation

Sightseeing

Tourism is travel for pleasure, and the commercial activity of providing and supporting such travel. UN Tourism defines tourism more generally, in terms which go "beyond the common perception of tourism as being limited to holiday activity o ...

, walking

Walking (also known as ambulation) is one of the main gaits of terrestrial locomotion among legged animals. Walking is typically slower than running and other gaits. Walking is defined as an " inverted pendulum" gait in which the body vaults o ...

, cycling

Cycling, also known as bicycling or biking, is the activity of riding a bicycle or other types of pedal-driven human-powered vehicles such as balance bikes, unicycles, tricycles, and quadricycles. Cycling is practised around the world fo ...

and mountain biking

Mountain biking (MTB) is a sport of riding bicycles off-road, often over rough terrain, usually using specially designed mountain bikes. Mountain bikes share similarities with other bikes but incorporate features designed to enhance durability ...

taking in Exmoor's dramatic heritage coastline and moorland countryside scenery are the main attractions.

The South West Coast Path

The South West Coast Path is England's longest waymarked Long-distance footpaths in the UK, long-distance footpath and a National Trail. It stretches for , running from Minehead in Somerset, along the coasts of Devon and Cornwall, to Poole Harb ...

starts at Minehead

Minehead is a coastal town and civil parish in Somerset, England. It lies on the south bank of the Bristol Channel, north-west of the county town of Taunton, from the boundary with the county of Devon and close to the Exmoor National Park. T ...

and follows all along the Exmoor coast before continuing to Poole

Poole () is a coastal town and seaport on the south coast of England in the Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole unitary authority area in Dorset, England. The town is east of Dorchester, Dorset, Dorchester and adjoins Bournemouth to the east ...

.

The Coleridge Way is an footpath

A footpath (also pedestrian way, walking trail, nature trail) is a type of thoroughfare that is intended for use only by pedestrians and not other forms of traffic such as Motor vehicle, motorized vehicles, bicycles and horseback, horses. They ...

which follows the walks taken by poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge

Samuel Taylor Coleridge ( ; 21 October 177225 July 1834) was an English poet, literary critic, philosopher, and theologian who was a founder of the Romantic Movement in England and a member of the Lake Poets with his friend William Wordsworth ...

to Lynmouth

Lynmouth is a village in Devon, England, on the northern edge of Exmoor. The village straddles the confluence of the West Lyn River, West Lyn and East Lyn River, East Lyn rivers, in a gorge directly below the neighbouring town of Lynton, w ...

, starting from Coleridge Cottage at Nether Stowey in the Quantocks where he once lived.

The Two Moors Way

The Two Moors Way is a long-distance trail mostly in Devon, UK, first established in 1976. It links Dartmoor and Exmoor and has been extended to become a Devon Coast-to-Coast trail.

History

The Two Moors Way was the brainchild of Joe Turner o ...

runs from Ivybridge

Ivybridge is a town and civil parish in the South Hams, in Devon, England. It lies about east of Plymouth. It is at the southern extremity of Dartmoor, a National Park of England and Wales and lies along the A38 "Devon Expressway" road. The ...

in South Devon

South Devon is the southern part of Devon, England. Because Devon has its major population centres on its two coasts, the county is divided informally into North Devon and South Devon.For exampleNorth DevonanSouth Devonnews sites. In a narrower s ...

to Lynmouth

Lynmouth is a village in Devon, England, on the northern edge of Exmoor. The village straddles the confluence of the West Lyn River, West Lyn and East Lyn River, East Lyn rivers, in a gorge directly below the neighbouring town of Lynton, w ...

on the coast of North Devon, crossing parts of both Dartmoor and Exmoor. Both of these walks intersect with the South West Coast Path

The South West Coast Path is England's longest waymarked Long-distance footpaths in the UK, long-distance footpath and a National Trail. It stretches for , running from Minehead in Somerset, along the coasts of Devon and Cornwall, to Poole Harb ...

, Britain's longest National Trail.

Other Exmoor walking trails include the Tarka Trail, Samaritans Way South West, Macmillan Way West

The Macmillan Way West is a long-distance footpath in Somerset and Devon, England. It runs for from Castle Cary in Somerset to Barnstaple in Devon. It is one of the Macmillan Ways and connects with the main Macmillan Way at Castle Cary.

The ...

, Exe Valley Way and Celtic Way Exmoor Option.

In addition to long distant walks the Exmoor National Park Authority promote a series 'top walks' in 3 collections of Exmoor Strolls (step and stile free routes more accessible routes), Exmoor Explorers (shorter walks to discover the best of Exmoor) and Exmoor Classics (longer walks to discover more of Exmoor).

For others, although the hunting

Hunting is the Human activity, human practice of seeking, pursuing, capturing, and killing wildlife or feral animals. The most common reasons for humans to hunt are to obtain the animal's body for meat and useful animal products (fur/hide (sk ...

of animal with hounds was made illegal by the Hunting Act 2004

The Hunting Act 2004 (c. 37) is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom which bans the hunting of most wild mammals (notably foxes, deer, hares and mink) with dogs in England and Wales, subject to some strictly limited exemptions; the ...

, the Exmoor hunts still meet in full regalia and there is a campaign to resurrect this rural sport. Nine hunts cover the area—the Devon and Somerset Staghounds and the Quantock Staghounds, the Exmoor, Dulverton West, Dulverton Farmers and West Somerset Foxhounds, the Minehead Harriers, the West Somerset Beagles and the North Devon Beagles. During the spring, amateur steeplechase meetings ( point-to-points) are run by hunts at temporary courses such as Bratton Down and Holnicote. These, along with thoroughbred racing

Thoroughbred racing is a sport and industry involving the racing of Thoroughbred horses. It is governed by different national bodies. There are two forms of the sport – flat racing and jump racing, the latter known as National Hunt racing in ...

and pony racing, are an opportunity for farmers, hunt staff and the public to witness a day of traditional country entertainment.

Places of interest

The attractions of Exmoor include 208Scheduled monument

In the United Kingdom, a scheduled monument is a nationally important archaeological site or historic building, given protection against unauthorised change.

The various pieces of legislation that legally protect heritage assets from damage, visu ...

s, 16 conservation areas, and other open access land as designated by the Countryside and Rights of Way Act 2000

The Countryside and Rights of Way Act 2000 (c. 37), also known as the CRoW Act and "Right to Roam" Act, is a United Kingdom Act of Parliament affecting England and Wales which came into force on 30 November 2000.

Right to roam

The Act impleme ...

. Exmoor receives approximately 1.4 million visitor days per year which include single day visits and those for longer periods.

The Exmoor National Park Authority operates three Exmoor National Park Centres in Dulverton, Dunster and Lynmouth to provide information and inspiration for users of the National Park.

Attractions on the coast include the Lynton and Lynmouth Cliff Railway, which connects Lynton to neighbouring picturesque Lynmouth

Lynmouth is a village in Devon, England, on the northern edge of Exmoor. The village straddles the confluence of the West Lyn River, West Lyn and East Lyn River, East Lyn rivers, in a gorge directly below the neighbouring town of Lynton, w ...

at the confluence of the East Lyn and West Lyn rivers, nearby Valley of Rocks and Watersmeet.

Woody Bay, a few miles west of Lynton, is home to the Lynton & Barnstaple Railway, a narrow-gauge railway

A narrow-gauge railway (narrow-gauge railroad in the US) is a railway with a track gauge (distance between the rails) narrower than . Most narrow-gauge railways are between and .

Since narrow-gauge railways are usually built with tighter cur ...

which once connected the twin towns of Lynton and Lynmouth

Lynmouth is a village in Devon, England, on the northern edge of Exmoor. The village straddles the confluence of the West Lyn River, West Lyn and East Lyn River, East Lyn rivers, in a gorge directly below the neighbouring town of Lynton, w ...

to Barnstaple

Barnstaple ( or ) is a river-port town and civil parish in the North Devon district of Devon, England. The town lies at the River Taw's lowest crossing point before the Bristol Channel. From the 14th century, it was licensed to export wool from ...

, about 31 km (just over 19 miles) away.

Further along the coast, Porlock

Porlock is a coastal village in Somerset, England, west of Minehead. At the 2011 census, the village had a population of 1,440.

In 2017, Porlock had the highest percentage of elderly population in England, with over 40% being of pensionable ...

is a quiet coastal town with an adjacent salt marsh

A salt marsh, saltmarsh or salting, also known as a coastal salt marsh or a tidal marsh, is a coastal ecosystem in the upper coastal intertidal zone between land and open saltwater or brackish water that is regularly flooded by the tides. I ...

nature reserve and a harbour at nearby Porlock Weir. Watchet is a historic harbour town with a marina and is home to a carnival, which is held annually in July.

Inland, many of the attractions are small towns and villages or linked to the river valleys, such as the ancient clapper bridge at Tarr Steps and the Snowdrop Valley near Wheddon Cross, which is carpeted in snowdrops in February and, later, displays bluebells. Withypool

Withypool (formerly Widepolle, Widipol, Withypoole) is a small village and former civil parish, now in the parish of Withypool and Hawkridge, in the Somerset (district), Somerset district, in the ceremonial county of Somerset, England, near the ...

is also in the Barle Valley, the Two Moors Way passes through the village. As well as Dunster Castle

Dunster Castle is a former motte and bailey castle, now a English country house, country house, in the village of Dunster, Somerset, England. The castle lies on the top of a steep hill called the Tor, and has been fortified since the late Anglo ...

, Dunster's other attractions include a priory, dovecote

A dovecote or dovecot , doocot (Scots Language, Scots) or columbarium is a structure intended to house Domestic pigeon, pigeons or doves. Dovecotes may be free-standing structures in a variety of shapes, or built into the end of a house or b ...

, yarn market, inn, packhorse bridge