execution by firing squad on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Execution by firing squad, in the past sometimes called fusillading (from the French ,

Execution by firing squad, in the past sometimes called fusillading (from the French ,

Execution by firing squad is a specific practice that is distinct from other forms of execution by firearms, such as an execution by shot(s) to the back of the head or neck. However, the single shot to the brain by the squad's officer with a pistol at point blank (

Execution by firing squad is a specific practice that is distinct from other forms of execution by firearms, such as an execution by shot(s) to the back of the head or neck. However, the single shot to the brain by the squad's officer with a pistol at point blank (

The method is often the capital punishment or disciplinary means employed by

The method is often the capital punishment or disciplinary means employed by

Cuba, as part of its penal system, still utilizes death by firing squad, although the last recorded execution was in 2003. In January 1992 a Cuban exile convicted of "terrorism, sabotage and enemy propaganda" was executed by firing squad. The Council of the State noted that the punishment served as a deterrent and stated that the death penalty "fulfills a goal of overall prevention, especially when the idea is to stop such loathsome actions from being repeated, to deter others and so to prevent innocent human lives from being endangered in the future".

During the months following the triumph of the

Cuba, as part of its penal system, still utilizes death by firing squad, although the last recorded execution was in 2003. In January 1992 a Cuban exile convicted of "terrorism, sabotage and enemy propaganda" was executed by firing squad. The Council of the State noted that the punishment served as a deterrent and stated that the death penalty "fulfills a goal of overall prevention, especially when the idea is to stop such loathsome actions from being repeated, to deter others and so to prevent innocent human lives from being endangered in the future".

During the months following the triumph of the

The New Zealand government

Ben Fenton, August 16, 2006, accessed October 14, 2006 On 15 October 1917 Dutch

Italy had used the firing squad as its only form of death penalty, both for civilians and military, since the unification of the country in 1861. The death penalty was abolished completely by both Italian Houses of Parliament in 1889 but revived under the Italian

Italy had used the firing squad as its only form of death penalty, both for civilians and military, since the unification of the country in 1861. The death penalty was abolished completely by both Italian Houses of Parliament in 1889 but revived under the Italian

During the Mexican Independence War, several Independentist generals (such as

During the Mexican Independence War, several Independentist generals (such as

During the

During the  John W. Deering allowed an electrocardiogram recording of the effect of gunshot wounds on his heart during his 1938 execution by firing squad, and afterwards his body was donated to the

John W. Deering allowed an electrocardiogram recording of the effect of gunshot wounds on his heart during his 1938 execution by firing squad, and afterwards his body was donated to the

Firing Squad Execution of a Civil War Deserter Described in an 1861 Newspaper

* ttp://www.thefirstpost.co.uk/64684,in-pictures,news-in-pictures,death-by-firing-squad Death by Firing Squad – slideshow by '' The First Post''

Nazis Meet the Firing Squad

– slideshow by ''

Execution by firing squad, in the past sometimes called fusillading (from the French ,

Execution by firing squad, in the past sometimes called fusillading (from the French , rifle

A rifle is a long gun, long-barreled firearm designed for accurate shooting and higher stopping power, with a gun barrel, barrel that has a helical or spiralling pattern of grooves (rifling) cut into the bore wall. In keeping with their focus o ...

), is a method of capital punishment

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty and formerly called judicial homicide, is the state-sanctioned killing of a person as punishment for actual or supposed misconduct. The sentence (law), sentence ordering that an offender b ...

, particularly common in the military

A military, also known collectively as armed forces, is a heavily armed, highly organized force primarily intended for warfare. Militaries are typically authorized and maintained by a sovereign state, with their members identifiable by a d ...

and in times of war

War is an armed conflict between the armed forces of states, or between governmental forces and armed groups that are organized under a certain command structure and have the capacity to sustain military operations, or between such organi ...

. Some reasons for its use are that firearm

A firearm is any type of gun that uses an explosive charge and is designed to be readily carried and operated by an individual. The term is legally defined further in different countries (see legal definitions).

The first firearms originate ...

s are usually readily available and a gunshot

A gunshot is a single discharge of a gun, typically a man-portable firearm, producing a visible flash, a powerful and loud shockwave and often chemical gunshot residue. The term can also refer to a ballistic wound caused by such a discharge ...

to a vital organ, such as the brain or heart, most often will kill relatively quickly.

Procedure

A firing squad is normally composed of at least several shooters, all of whom are usually instructed to fire simultaneously, thus preventing both disruption of the process by one member and identification of who fired the lethal shot. To avoid disfigurement due to multiple shots to the head, the shooters are typically instructed to aim at theheart

The heart is a muscular Organ (biology), organ found in humans and other animals. This organ pumps blood through the blood vessels. The heart and blood vessels together make the circulatory system. The pumped blood carries oxygen and nutrie ...

, sometimes aided by a paper or cloth target. The prisoner is typically blindfold

A blindfold (from Middle English ') is a garment, usually of cloth, tied to one's head to cover the eyes to disable the wearer's sight. While a properly fitted blindfold prevents sight even if the eyes are open, a poorly tied or trick blindfo ...

ed or hooded as well as restrained. Executions

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty and formerly called judicial homicide, is the state-sanctioned killing of a person as punishment for actual or supposed misconduct. The sentence ordering that an offender be punished in s ...

can be carried out with the condemned either standing or sitting. There is a tradition in some jurisdictions that such executions are carried out at first light or at sunrise, giving rise to the phrase "shot at dawn".

Associated Press writer Jeffrey Collins described the execution by firing squad of a murderer, Brad Sigmon, in 2025 as follows:

:"Mr. Sigmon’s lawyer read his final statement. The hood was put over Mr. Sigmon’s head, and an employee opened the black pull shade that shielded where the three prison-system volunteer shooters were. About two minutes later, they fired. There was no warning or countdown. The abrupt crack of the rifles startled me. And the white target with the red bull’s-eye that had been on his chest, standing out against his black prison jumpsuit, disappeared instantly as Mr. Sigmon’s whole body flinched. A jagged red spot about the size of a small fist appeared where Mr. Sigmon was shot. His chest moved two or three times. Outside of the rifle crack, there was no sound. A doctor came out in less than a minute, and his examination took about a minute more. Mr. Sigmon was declared dead at 6:08 p.m."

The National News Desk reporter Brian McConchie, who attended the execution of Mikal Mahdi in 2025, spoke at the Mahdi execution press conference:

:"This seemed like a very fast process. The curtain opened seconds before 6 p.m. and within four and a half to five minutes the process is over, and you are exiting the chamber in silence, you're not speaking to anyone."

Associated Press journalist Jeffrey Collins provided more detail:

:"Mahdi, 42, cried out as the bullets hit him, and his arms flexed. A white target with the red bull’s-eye over his heart was pushed into the wound in his chest.

Mahdi groaned two more times about 45 seconds after that. His breaths continued for about 80 seconds before he appeared to take one final gasp."

Execution by firing squad is a specific practice that is distinct from other forms of execution by firearms, such as an execution by shot(s) to the back of the head or neck. However, the single shot to the brain by the squad's officer with a pistol at point blank (

Execution by firing squad is a specific practice that is distinct from other forms of execution by firearms, such as an execution by shot(s) to the back of the head or neck. However, the single shot to the brain by the squad's officer with a pistol at point blank (coup de grâce

A coup de grâce (; ) is an act of mercy killing in which a person or animal is struck with a melee weapon or shot with a projectile to end their suffering from mortal wounds with or without their consent. Its meaning has extended to refer to ...

) is sometimes incorporated in a firing squad execution, particularly if the initial volley turns out not to be immediately fatal. Before the introduction of firearms, bows or crossbow

A crossbow is a ranged weapon using an Elasticity (physics), elastic launching device consisting of a Bow and arrow, bow-like assembly called a ''prod'', mounted horizontally on a main frame called a ''tiller'', which is hand-held in a similar f ...

s were often used—Saint Sebastian

Sebastian (; ) was an early Christianity, Christian saint and martyr. According to traditional belief, he was killed during the Diocletianic Persecution of Christians. He was initially tied to a post or tree and shot with arrows, though this d ...

is usually depicted as executed by a squad of Roman auxiliary archers in around AD 288; King Edmund the Martyr

Edmund the Martyr (also known as St Edmund or Edmund of East Anglia, died 20 November 869) was king of East Anglia from about 855 until his death.

Few historical facts about Edmund are known, as the kingdom of East Anglia was devastated by t ...

of East Anglia

East Anglia is an area of the East of England, often defined as including the counties of Norfolk, Suffolk and Cambridgeshire, with parts of Essex sometimes also included.

The name derives from the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of the East Angles, ...

, by some accounts, was tied to a tree and executed by Viking

Vikings were seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway, and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded, and settled throughout parts of Europe.Roesdahl, pp. 9� ...

archers on 20 November 869 or 870.

Sometimes, one or more of the members of the firing squad may be issued a rifle containing a blank cartridge

A blank is a firearm cartridge that, when fired, does not shoot a projectile like a bullet or pellet, but generates a muzzle flash and an explosive sound ( muzzle report) like a normal gunshot would. Firearms may need to be modified to allow a ...

. In such cases, the shooters are not told beforehand whether they are using live or blank ammunition. This is believed to reinforce the sense of diffusion of responsibility

Diffusion of responsibility is a sociopsychological phenomenon whereby a person is less likely to take responsibility for action or inaction when other bystanders or witnesses are present. Considered a form of attribution, the individual assume ...

among the firing squad members. It provides each member with a measure of plausible deniability

Plausible deniability is the ability of people, typically senior officials in a formal or informal chain of command, to deny knowledge or responsibility for actions committed by or on behalf of members of their organizational hierarchy. They may ...

that they, personally, did not fire a bullet at all. In practice however, firing a live round produces significant recoil, while firing a blank round does not. In more modern times such as during the 2010 execution of Ronnie Lee Gardner in Utah, US, one rifleman may be given a "dummy" cartridge containing a wax bullet, which provides a more realistic recoil.

Military significance

military court

A court-martial (plural ''courts-martial'' or ''courts martial'', as "martial" is a postpositive adjective) is a military court or a trial conducted in such a court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of members of the arme ...

s for crimes such as cowardice

Cowardice is a characteristic wherein excessive fear prevents an individual from taking a risk or facing danger. It is the opposite of courage. As a label, "cowardice" indicates a failure of character in the face of a challenge. One who succumb ...

, desertion

Desertion is the abandonment of a military duty or post without permission (a pass, liberty or leave) and is done with the intention of not returning. This contrasts with unauthorized absence (UA) or absence without leave (AWOL ), which ...

, espionage

Espionage, spying, or intelligence gathering, as a subfield of the intelligence field, is the act of obtaining secret or confidential information ( intelligence). A person who commits espionage on a mission-specific contract is called an ...

, murder

Murder is the unlawful killing of another human without justification (jurisprudence), justification or valid excuse (legal), excuse committed with the necessary Intention (criminal law), intention as defined by the law in a specific jurisd ...

, mutiny

Mutiny is a revolt among a group of people (typically of a military or a crew) to oppose, change, or remove superiors or their orders. The term is commonly used for insubordination by members of the military against an officer or superior, ...

, or treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state (polity), state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to Coup d'état, overthrow its government, spy ...

.

If the condemned prisoner is an ex-officer who is acknowledged to have shown bravery throughout their career, they may be afforded the privilege of giving the order to fire. Cases of this are the executions of Marshals

Marshal is a term used in several official titles in various branches of society. As marshals became trusted members of the courts of Medieval Europe, the title grew in reputation. During the last few centuries, it has been used for elevated of ...

Michel Ney

Michel Ney, 1st Prince de la Moskowa, 1st Duke of Elchingen (; 10 January 1769 – 7 December 1815), was a French military commander and Marshal of the Empire who fought in the French Revolutionary Wars and the Napoleonic Wars.

The son of ...

and Joachim Murat

Joachim Murat ( , also ; ; ; 25 March 1767 – 13 October 1815) was a French Army officer and statesman who served during the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. Under the French Empire he received the military titles of Marshal of the ...

. As a means of insulting the condemned, however, past executions have had them shot in the back, denied blindfolds, or even tied to chairs. When Galeazzo Ciano

Gian Galeazzo Ciano, 2nd Count of Cortellazzo and Buccari ( , ; 18 March 1903 – 11 January 1944), was an Italian diplomat and politician who served as Italian Minister of Foreign Affairs, Foreign Minister in the government of his father-in-law ...

, son-in-law of Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who, upon assuming office as Prime Minister of Italy, Prime Minister, became the dictator of Fascist Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 un ...

, and several other former fascists who voted to remove Mussolini from power were executed, they were tied to chairs facing away from their executioners. By some reports, Ciano managed to twist his chair around at the last second to face them, but this is unconfirmed.

By country

Argentina

Manuel Dorrego

Manuel Dorrego (11 June 1787 – 13 December 1828) was an Argentine statesman and soldier. He was governor of Buenos Aires in 1820, and then again from 1827 to 1828.

Early life and education

Dorrego was born in Buenos Aires on 11 June 1787 t ...

, a prominent Argentine statesman and soldier who governed Buenos Aires in the 1820s, was executed by firing squad on 12 December 1828 after being defeated in battle by Juan Lavalle and later convicted of treason.

Belgium

On 12 October 1915 British nurseEdith Cavell

Edith Louisa Cavell ( ; 4 December 1865 – 12 October 1915) was a British nurse. She is celebrated for treating wounded soldiers from both sides without discrimination during the First World War and for helping some 200 Allied soldiers escape ...

was executed by a German firing squad at the Tir national

The National Shooting Range (; ) was a firing range and military training complex of situated in the municipality of Schaerbeek in Brussels, Belgium. Opened in 1889, it was intended as a place where the '' Garde Civique'' and the army could co ...

shooting range at Schaerbeek

(French language, French, ; former History of Dutch orthography, Dutch spelling) or (modern Dutch language, Dutch, ) is one of the List of municipalities of the Brussels-Capital Region, 19 municipalities of the Brussels, Brussels-Capital Reg ...

, after being convicted of "conveying troops to the enemy" during the First World War.

On 1 April 1916 a Belgian woman, Gabrielle Petit

Gabrielle Alina Eugenia Maria Petit (20 February 1893 – 1 April 1916) was a Belgian spy who worked for the British Secret Service in German-occupied Belgium during World War I. She was executed in 1916, and was widely celebrated as a Belgi ...

, was executed by a German firing squad at Schaerbeek

(French language, French, ; former History of Dutch orthography, Dutch spelling) or (modern Dutch language, Dutch, ) is one of the List of municipalities of the Brussels-Capital Region, 19 municipalities of the Brussels, Brussels-Capital Reg ...

after being convicted of spying for the British Secret Service during World War I.

During the Battle of the Bulge

The Battle of the Bulge, also known as the Ardennes Offensive or Unternehmen Die Wacht am Rhein, Wacht am Rhein, was the last major German Offensive (military), offensive Military campaign, campaign on the Western Front (World War II), Western ...

in World War II, three captured German spies were tried and executed by a U.S. firing squad at Henri-Chapelle on 23 December 1944. Thirteen other Germans were also tried and shot at either Henri-Chapelle or Huy.Pallud, p. 15 These executed spies took part in Waffen-SS

The (; ) was the military branch, combat branch of the Nazi Party's paramilitary ''Schutzstaffel'' (SS) organisation. Its formations included men from Nazi Germany, along with Waffen-SS foreign volunteers and conscripts, volunteers and conscr ...

commando

A commando is a combatant, or operative of an elite light infantry or special operations force, specially trained for carrying out raids and operating in small teams behind enemy lines.

Originally, "a commando" was a type of combat unit, as oppo ...

Otto Skorzeny

Otto Johann Anton Skorzeny (12 June 1908 – 5 July 1975) was an Austrian-born German SS-''Standartenführer'' in the ''Waffen-SS'' during World War II. During the war, he was involved in a number of operations, including the removal from power ...

's Operation Greif

Operation Greif ( () was a special operation commanded by ''Waffen-SS'' commando Otto Skorzeny during the Battle of the Bulge in World War II. The operation was the brainchild of Adolf Hitler, and its purpose was to capture one or more of the brid ...

, in which English-speaking German commandos operated behind U.S. lines, masquerading in U.S. uniforms and equipment.

Brazil

The Brazilian Constitution of 1988 expressly prohibits the usage of capital punishment in peacetime, but authorizes the use of the death penalty for military crimes committed during wartime. War must be declared formally, in accordance with international law and article 84, item 19 of the Federal Constitution, with due authorization from the Brazilian Congress. The Brazilian Code of Military Penal Law, in its chapter dealing with wartime offences, specifies the crimes that are subject to the death penalty. The death penalty is never the only possible sentence for a crime, and the punishment must be imposed by the military courts system. Per the norms of the Brazilian Code of Military Penal Procedure, the death penalty is carried out by firing squad. Although Brazil still permits the use of capital punishment during wartime, no convicts were actually executed during Brazil's last military conflict, the Second World War. The military personnel sentenced to death during World War II had their sentences reduced by the President of the Republic.Cuba

Cuba, as part of its penal system, still utilizes death by firing squad, although the last recorded execution was in 2003. In January 1992 a Cuban exile convicted of "terrorism, sabotage and enemy propaganda" was executed by firing squad. The Council of the State noted that the punishment served as a deterrent and stated that the death penalty "fulfills a goal of overall prevention, especially when the idea is to stop such loathsome actions from being repeated, to deter others and so to prevent innocent human lives from being endangered in the future".

During the months following the triumph of the

Cuba, as part of its penal system, still utilizes death by firing squad, although the last recorded execution was in 2003. In January 1992 a Cuban exile convicted of "terrorism, sabotage and enemy propaganda" was executed by firing squad. The Council of the State noted that the punishment served as a deterrent and stated that the death penalty "fulfills a goal of overall prevention, especially when the idea is to stop such loathsome actions from being repeated, to deter others and so to prevent innocent human lives from being endangered in the future".

During the months following the triumph of the Cuban Revolution

The Cuban Revolution () was the military and political movement that overthrew the dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista, who had ruled Cuba from 1952 to 1959. The revolution began after the 1952 Cuban coup d'état, in which Batista overthrew ...

in 1959, soldiers of the Batista

Batista is a Spanish language, Spanish or Portuguese language, Portuguese surname. Notable persons with the name include:

* Batista (footballer, born 1955), Brazilian football player João Batista da Silva

* Dave Bautista, Batista (wrestler) (Dave ...

government and political opponents to the revolution were executed by firing squad.

Finland

The death penalty was widely used during and after theFinnish Civil War

The Finnish Civil War was a civil war in Finland in 1918 fought for the leadership and control of the country between Whites (Finland), White Finland and the Finnish Socialist Workers' Republic (Red Finland) during the country's transition fr ...

(January–May 1918); some 9,700 Finns and an unknown number of Russian volunteers on the Red side were executed during the war or in its aftermath. Most executions were carried out by firing squads after the sentences were given by illegal or semi-legal courts martial. Only some 250 persons were sentenced to death in courts acting on legal authority.

During World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

some 500 persons were executed, half of them condemned spies. The usual causes for death penalty for Finnish citizen

Finnish nationality law details the conditions by which an individual is a national of Finland. The primary law governing these requirements is the Nationality Act, which came into force on 1 June 2003. Finland is a member state of the Euro ...

s were treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state (polity), state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to Coup d'état, overthrow its government, spy ...

and high treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its d ...

(and to a lesser extent cowardice and disobedience, applicable for military personnel). Almost all cases of capital punishment were tried by court-martial. Usually the executions were carried out by the regimental military police platoon, or by the local military police in the case of spies. One Finn, Toivo Koljonen

(12 December 1910 – 21 October 1943) was a Finnish mass murderer and the last Finn executed for a civilian crime. He was executed by firing squad for a sextuple murder.

was born 1910 in , Grand Duchy of Finland, Finland. He had been sent ...

, was executed for a civilian crime (six murders). Most executions occurred in 1941 and during the Soviet Summer Offensive in 1944. The last death sentences were given in 1945 for murder, but later commuted to life imprisonment.

The death penalty was abolished by Finnish law in 1949 for crimes committed during peacetime, and in 1972 for all crimes. Finland is party to the Optional protocol of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights

The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) is a multilateral treaty that commits nations to respect the civil and political rights of individuals, including the right to life, freedom of religion, freedom of speech, freedom ...

, forbidding the use of the death penalty in all circumstances.

France

Pte.Thomas Highgate

Private Thomas James Highgate (13 May 1895 – 8 September 1914) was a British Armed Forces, British soldier during the First World War and the first British soldier to be convicted of desertion and executed by firing squad on the Western Fron ...

was the first British soldier to be convicted of desertion and executed by firing squad in September 1914 at Tournan-en-Brie

Tournan-en-Brie (, literally ''Tournan in Brie (region), Brie''), or simply Tournan, is a Communes of France, commune in the Seine-et-Marne Departments of France, department in the Île-de-France Regions of France, region in north-central France. ...

during World War I. In October 1916 Pte. Harry Farr was shot for cowardice at Carnoy, which was later suspected to be acoustic shock. Highgate and Farr, along with 304 other British and Imperial troops who were executed for similar offenses, were listed at the Shot at Dawn Memorial

The Shot at Dawn Memorial is a monument at the National Memorial Arboretum near Alrewas, in Staffordshire, England. It commemorates the 306 British Army and Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth soldiers executed after courts-martial for desertio ...

which was erected to honor them.The Shot at Dawn CampaignThe New Zealand government

pardon

A pardon is a government decision to allow a person to be relieved of some or all of the legal consequences resulting from a criminal conviction. A pardon may be granted before or after conviction for the crime, depending on the laws of the j ...

ed its troops in 2000; the British government in 1998 expressed sympathy for the executed and in 2006 the Secretary of State for Defence

The secretary of state for defence, also known as the defence secretary, is a secretary of state in the Government of the United Kingdom, with responsibility for the Ministry of Defence. As a senior minister, the incumbent is a member of the ...

announced a full pardon for all 306 executed soldiers from the First World War.The Daily TelegraphBen Fenton, August 16, 2006, accessed October 14, 2006 On 15 October 1917 Dutch

exotic dancer

A stripper or exotic dancer is a person whose occupation involves performing striptease in a public adult entertainment venue such as a strip club. At times, a stripper may be hired to perform at private events.

Modern forms of stripping m ...

Mata Hari

Margaretha Geertruida MacLeod (, ; 7 August 187615 October 1917), better known by the stage name Mata Hari ( , ; , ), was a Dutch Stripper, exotic dancer and courtesan who was convicted of being a spy for German Empire, Germany during World War ...

was executed by a French firing squad at Château de Vincennes

The Château de Vincennes () is a former fortress and royal residence next to the town of Vincennes, on the eastern edge of Paris, alongside the Bois de Vincennes. It was largely built between 1361 and 1369, and was a preferred residence, after ...

castle in the town of Vincennes

Vincennes (; ) is a commune in the Val-de-Marne department in the eastern suburbs of Paris, France. It is located from the centre of Paris. Vincennes is famous for its castle: the Château de Vincennes. It is next to but does not include the ...

after being convicted of spying for Germany during World War I.

During World War II, on 24 September 1944, Josef Wende and Stephan Kortas, two Poles drafted into the German army, crossed the Moselle Rivers behind U.S. lines in civilian clothes to observe Allied strength and were to rejoin their own army on the same day. However, they were discovered by the Americans and arrested. On 18 October 1944 they were found guilty of espionage by a U.S. military commission and sentenced to death. On 11 November 1944 they were shot in the garden of a farmhouse at Toul

Toul () is a Communes of France, commune in the Meurthe-et-Moselle Departments of France, department in north-eastern France.

It is a Subprefectures in France, sub-prefecture of the department.

Geography

Toul is between Commercy and Nancy, Fra ...

. The footage of Wende's execution as well as Kortas's is shown in these links.

On 31 January 1945, U.S. Army Pvt. Edward "Eddie" Slovik was executed by firing squad for desertion near the village of Sainte-Marie-aux-Mines. He was the first American soldier executed for such offense since the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

.

On 15 October 1945 Pierre Laval

Pierre Jean Marie Laval (; 28 June 1883 – 15 October 1945) was a French politician. He served as Prime Minister of France three times: 1931–1932 and 1935–1936 during the Third Republic (France), Third Republic, and 1942–1944 during Vich ...

, the puppet leader of Nazi-occupied Vichy France

Vichy France (; 10 July 1940 – 9 August 1944), officially the French State ('), was a French rump state headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain during World War II, established as a result of the French capitulation after the Battle of France, ...

, was executed for treason at Fresnes Prison in Paris.

On 11 March 1963 Jean Bastien-Thiry was the last person to be executed by firing squad for a failed attempt to assassinate French president Charles de Gaulle

Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle (22 November 18909 November 1970) was a French general and statesman who led the Free France, Free French Forces against Nazi Germany in World War II and chaired the Provisional Government of the French Re ...

.

Indonesia

Execution by firing squad is the capital punishment method used in Indonesia. The following persons were executed (reported by BBC World Service) by firing squad on 29 April 2015 following convictions for drug offences: two Australians,Myuran Sukumaran

Myuran Sukumaran (17 April 1981 – 29 April 2015) was an Australian who was convicted in Indonesia of drug trafficking as a member of the Bali Nine. In 2005, Sukumaran was arrested in a room at the Melasti Hotel in Kuta, Bali with eight othe ...

and Andrew Chan, the Ghanaian Martin Anderson, the Indonesian Zainal Abidin bin Mgs Mahmud Badarudin, three Nigerians: Raheem Agbaje Salami, Sylvester Obiekwe Nwolise and Okwudili Oyatanze, as well as Brazilian Rodrigo Gularte.

In 2006 Fabianus Tibo, Dominggus da Silva and Marinus Riwu were executed. Nigeria

Nigeria, officially the Federal Republic of Nigeria, is a country in West Africa. It is situated between the Sahel to the north and the Gulf of Guinea in the Atlantic Ocean to the south. It covers an area of . With Demographics of Nigeria, ...

n drug smugglers Samuel Iwachekwu Okoye and Hansen Anthoni Nwaolisa were executed in June 2008 in Nusakambangan Island. Five months later three men convicted for the 2002 Bali bombing

The 2002 Bali bombings were a series of terrorist attacks on 12 October 2002 in the tourist district of Kuta on the Indonesian island of Bali. The attacks killed 202 people (including 88 Australians, 38 Indonesians, 23 Britons, and people ...

—Amrozi

Ali Amrozi bin Haji Nurhasyim (, 5 July 1962 – 9 November 2008) was an Indonesian terrorist who was convicted and executed for his role in carrying out the Christmas Eve 2000 Indonesia bombings and 2002 Bali bombings. Amrozi was the brother o ...

, Imam Samudra

Imam Samudra (, 14 January 1970 – 9 November 2008), also known as Abdul Aziz, Qudama/Kudama, Fatih/Fat, Abu Umar or Heri, was an Indonesian terrorist who was convicted and executed for his role in carrying out the Christmas Eve 2000 Indonesia ...

and Ali Ghufron—were executed on the same spot in Nusakambangan. In January 2013 56-year-old British woman Lindsay Sandiford was sentenced to execution by firing squad for importing a large amount of cocaine; she lost her appeal against her sentence in April 2013. On 18 January 2015, under the new leadership of Joko Widodo

Joko Widodo (; born 21 June 1961), often known mononymously as Jokowi, is an Indonesian politician, engineer, and businessman who served as the seventh president of Indonesia from 2014 to 2024. Previously a member of the Indonesian Democratic ...

, six people sentenced to death for producing and smuggling drugs into Indonesia

Indonesia, officially the Republic of Indonesia, is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania, between the Indian Ocean, Indian and Pacific Ocean, Pacific oceans. Comprising over List of islands of Indonesia, 17,000 islands, including Sumatra, ...

were executed at Nusa Kambangan

Nusa Kambangan is an island located in Indonesia, separated by a narrow strait from the south coast of Java. The closest port is Cilacap in Central Java province. It is known as the place where the fabled ''wijayakusuma'', which translates as th ...

Penitentiary shortly after midnight.

Ireland

Following the 1916Easter Rising

The Easter Rising (), also known as the Easter Rebellion, was an armed insurrection in Ireland during Easter Week in April 1916. The Rising was launched by Irish republicans against British rule in Ireland with the aim of establishing an ind ...

in Ireland, 15 of the 16 leaders who were executed were shot by the Dublin Castle administration

Dublin Castle was the centre of the government of Ireland under English and later British rule. "Dublin Castle" is used metonymically to describe British rule in Ireland. The Castle held only the executive branch of government and the Privy Cou ...

under martial law

Martial law is the replacement of civilian government by military rule and the suspension of civilian legal processes for military powers. Martial law can continue for a specified amount of time, or indefinitely, and standard civil liberties ...

. The executions have often been cited as a reason for how the Rising managed to galvanise public support in Ireland after the failed rebellion.

Following the Anglo-Irish Treaty

The 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty (), commonly known in Ireland as The Treaty and officially the Articles of Agreement for a Treaty Between Great Britain and Ireland, was an agreement between the government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain an ...

, a split in the government and the Dáil led to a Civil War

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

during which the Free State Government sanctioned the executions by firing squad of 81 persons. Included in those numbers were some prominent prisoners who were executed without trial as reprisals. Records show that eleven soldiers would have had live rounds in their weapons, and one soldier had a blank round. The officers loaded the weapons for the soldiers so no soldier knew if his weapon contained the blank round or a live one. This method was used to prevent the soldiers from being prosecuted for war crimes in the future, as it was impossible to know which soldier had fired a blank round, and therefore all soldiers could claim innocence.

Italy

Italy had used the firing squad as its only form of death penalty, both for civilians and military, since the unification of the country in 1861. The death penalty was abolished completely by both Italian Houses of Parliament in 1889 but revived under the Italian

Italy had used the firing squad as its only form of death penalty, both for civilians and military, since the unification of the country in 1861. The death penalty was abolished completely by both Italian Houses of Parliament in 1889 but revived under the Italian dictatorship

A dictatorship is an autocratic form of government which is characterized by a leader, or a group of leaders, who hold governmental powers with few to no Limited government, limitations. Politics in a dictatorship are controlled by a dictator, ...

of Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who, upon assuming office as Prime Minister of Italy, Prime Minister, became the dictator of Fascist Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 un ...

in 1926. Mussolini was himself shot in the last days of World War II.

On 1 December 1945 Anton Dostler, the first German general

A general officer is an Officer (armed forces), officer of high rank in the army, armies, and in some nations' air force, air and space forces, marines or naval infantry.

In some usages, the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colone ...

to be tried for war crimes, was executed by a U.S. firing squad in Aversa

Aversa () is a city and ''comune'' in the Province of Caserta in Campania, southern Italy, about 24 km north of Naples. It is the centre of an agricultural district, the ''Agro Aversano'', producing wine and cheese (famous for the typical dome ...

after being found guilty by a U.S. military tribunal of ordering the killing of 15 U.S. prisoners of war in Italy during World War II.

The last execution took place on 4 March 1947, as Francesco La Barbera, Giovanni Puleo and Giovanni D'Ignoti, sentenced to death on multiple accounts of robbery and murder, faced the firing squad at the range of Basse di Stura, near Turin

Turin ( , ; ; , then ) is a city and an important business and cultural centre in northern Italy. It is the capital city of Piedmont and of the Metropolitan City of Turin, and was the first Italian capital from 1861 to 1865. The city is main ...

. Soon after the Constitution of the newly proclaimed Republic prohibited the death penalty except for some crimes of the military penal code of war, like high treason; no one was sentenced to death after 1947. In 2007 the Constitution was amended to ban the death penalty altogether.

Malta

Firing squads were used during the periods of French and British control in Malta. Ringleaders of rebellions were often shot dead by firing squad during the French period, with perhaps the most notable examples beingDun Mikiel Xerri

Dun Mikiel Xerri (Żebbuġ, Hospitaller Malta, 29 September 1737 – 17 January 1799) was a Maltese patriot. He was baptised Mikael Archangelus Joseph in the parish church of Żebbuġ on 30 September 1737, the son of Bartholomew Xerri and his ...

and other patriots in 1799.

The British also used the practice briefly, and for the last time in 1813, when two men were shot separately outside the courthouse

A courthouse or court house is a structure which houses judicial functions for a governmental entity such as a state, region, province, county, prefecture, regency, or similar governmental unit. A courthouse is home to one or more courtrooms, ...

after being convicted of failing to report their infection of plague to the authorities.

Mexico

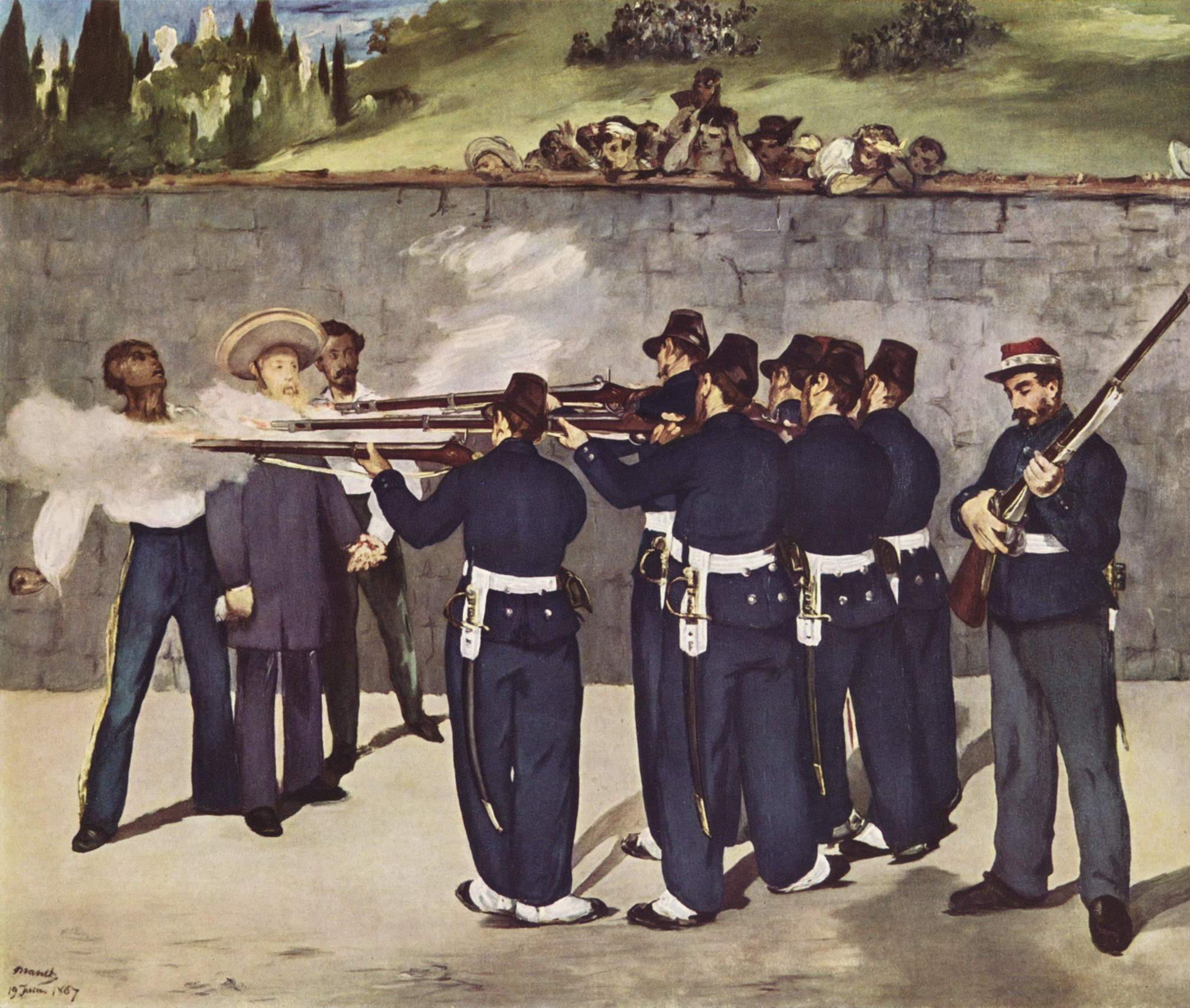

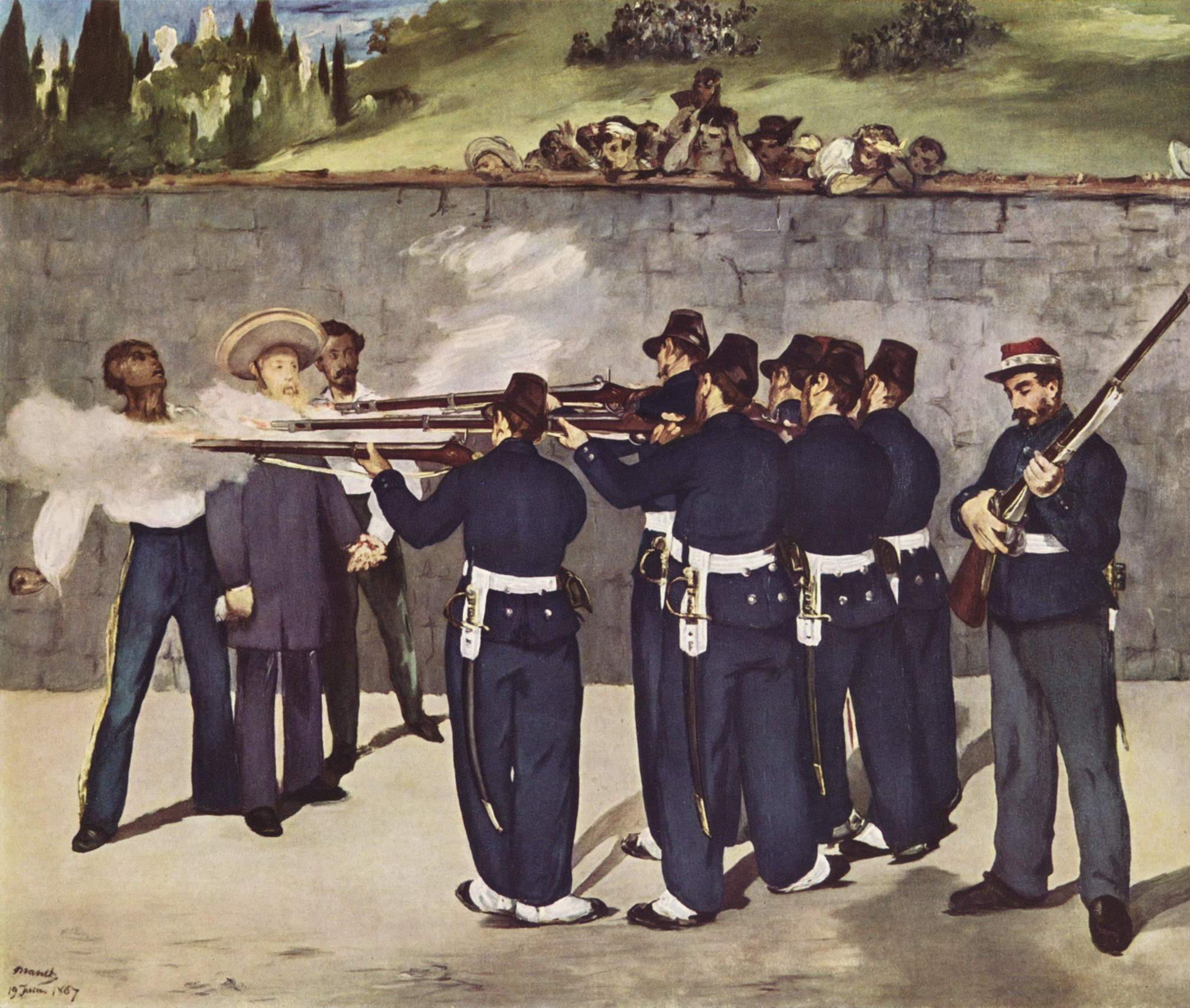

During the Mexican Independence War, several Independentist generals (such as

During the Mexican Independence War, several Independentist generals (such as Miguel Hidalgo

Don Miguel Gregorio Antonio Ignacio Hidalgo y Costilla Gallaga Mandarte y Villaseñor (8 May 1753 – 30 July 1811), commonly known as Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla or simply Miguel Hidalgo (), was a Catholic priest, leader of the Mexican Wa ...

and José María Morelos

José María Teclo Morelos Pérez y Pavón () (30 September 1765 – 22 December 1815) was a Mexican Priesthood in the Catholic Church, Catholic priest, statesman and military leader who led the Mexican War of Independence movement, assuming it ...

) were executed by Spanish firing squads.Known history of the Mexican Revolution Also, Emperor Maximilian I of Mexico

Maximilian I (; ; 6 July 1832 – 19 June 1867) was an Austrian Empire, Austrian archduke who became Emperor of Mexico, emperor of the Second Mexican Empire from 10 April 1864 until his execution by the Restored Republic (Mexico), Mexican Republ ...

and two of his generals were executed in the Cerro de las Campanas after the Juaristas took control of Mexico in 1867. Manet immortalized the execution in a now-famous painting, '' The Execution of Emperor Maximilian''; he painted at least three versions.

Firing-squad execution was the most common way to carry out a death sentence in Mexico, especially during the Mexican Revolution

The Mexican Revolution () was an extended sequence of armed regional conflicts in Mexico from 20 November 1910 to 1 December 1920. It has been called "the defining event of modern Mexican history". It saw the destruction of the Federal Army, its ...

and the Cristero War

The Cristero War (), also known as the Cristero Rebellion or , was a widespread struggle in central and western Mexico from 3 August 1926 to 21 June 1929 in response to the implementation of secularism, secularist and anti-clericalism, anticler ...

. An example of that is in the attempted execution of Wenseslao Moguel, who survived being shot ten times—once at point-blank range—because he fought under Pancho Villa

Francisco "Pancho" Villa ( , , ; born José Doroteo Arango Arámbula; 5 June 1878 – 20 July 1923) was a Mexican revolutionary and prominent figure in the Mexican Revolution. He was a key figure in the revolutionary movement that forced ...

. After these events, the death sentence was imposed for fewer types of crimes in Article 22 of the Mexican Constitution

The current Constitution of Mexico, formally the Political Constitution of the United Mexican States (), was drafted in Santiago de Querétaro, in the State of Querétaro, Mexico, by a constituent convention during the Mexican Revolution. I ...

; however, in 2005 capital punishment was constitutionally prohibited, and there has not been a judicial execution since 1961.

Netherlands

During the Nazi occupation in World War II some 3,000 persons were executed by German firing squads. The victims were sometimes sentenced by a military court; in other cases they were hostages or arbitrary pedestrians who were executed publicly to intimidate the population. After the attack on high-ranking German officer Hanns Albin Rauter, about 300 people were executed publicly as reprisal against resistance movements. Rauter himself was executed nearScheveningen

Scheveningen () is one of the eight districts of The Hague, Netherlands, as well as a subdistrict () of that city. Scheveningen is a modern seaside resort with a long, sandy beach, an esplanade, a pier, and a lighthouse. The beach is popular ...

on 12 January 1949, following his conviction for war crimes. Anton Mussert, a Dutch Nazi

Nazism (), formally named National Socialism (NS; , ), is the far-right politics, far-right Totalitarianism, totalitarian socio-political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Germany. During H ...

leader, was sentenced to death by firing squad and executed in the dunes near The Hague

The Hague ( ) is the capital city of the South Holland province of the Netherlands. With a population of over half a million, it is the third-largest city in the Netherlands. Situated on the west coast facing the North Sea, The Hague is the c ...

on 7 May 1946.

While under Allied guard in Amsterdam, and five days after the capitulation of Nazi Germany, two German Navy deserters were shot by a firing squad composed of other German prisoners kept in the Canadian

Canadians () are people identified with the country of Canada. This connection may be residential, legal, historical or cultural. For most Canadians, many (or all) of these connections exist and are collectively the source of their being ''C ...

-run prisoner-of-war camp

A prisoner-of-war camp (often abbreviated as POW camp) is a site for the containment of enemy fighters captured as Prisoner of war, prisoners of war by a belligerent power in time of war.

There are significant differences among POW camps, inte ...

. The men were lined up against the wall of an air raid shelter

Air raid shelters are structures for the protection of non-combatants as well as combatants against enemy attacks from the air. They are similar to bunkers in many regards, although they are not designed to defend against ground attack (but ...

near an abandoned Ford Motor Company

Ford Motor Company (commonly known as Ford) is an American multinational corporation, multinational automobile manufacturer headquartered in Dearborn, Michigan, United States. It was founded by Henry Ford and incorporated on June 16, 1903. T ...

assembly plant in the presence of Canadian military.

Nigeria

Nigeria executes criminals who committed armed robberies—such as Ishola Oyenusi, Lawrence Anini and Osisikankwu—as well as military officers convicted of plotting coups against the government, such as Buka Suka Dimka and Maj. Gideon Orkar, by firing squad.Norway

Vidkun Quisling

Vidkun Abraham Lauritz Jonssøn Quisling (; ; 18 July 1887 – 24 October 1945) was a Norwegian military officer, politician and Collaboration with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy, Nazi collaborator who Quisling regime, headed the government of N ...

, the leader of the collaborationist Nasjonal Samling

The Nasjonal Samling (, NS; ) was a Norway, Norwegian far-right politics, far-right political party active from 1933 to 1945. It was the only legal party of Norway from 1942 to 1945. It was founded by former minister of defence Vidkun Quisling a ...

Party and president of Norway during the German occupation in World War II, was sentenced to death for treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state (polity), state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to Coup d'état, overthrow its government, spy ...

and executed by firing squad on 24 October 1945 at the Akershus Fortress

Akershus Fortress (, ) or Akershus Castle ( ) is a medieval castle in the Norwegian capital Oslo that was built to protect and provide a royal residence for the city. Since the Middle Ages the fortress has been the namesake and centre of the ...

.

Philippines

Jose Rizal

Jose is the English transliteration of the Hebrew and Aramaic name ''Yose'', which is etymologically linked to ''Yosef'' or Joseph.

Given name Mishnaic and Talmudic periods

* Jose ben Abin

* Jose ben Akabya

*Jose the Galilean

* Jose ben Halaft ...

was executed by firing squad on the morning of 30 December 1896, in what is now Rizal Park

Rizal Park (), also known as Luneta Park or simply Luneta, is a historic urban park located in Ermita, Manila. It is considered one of the largest urban parks in the Philippines, covering an area of . The site on where the park is situated was ...

, where his remains have since been placed.

While in avitethere were 13 people who executed by firing squad. They are known today as 13 martyrs of Cavite.

During the Marcos

Marcos may refer to:

People with the given name ''Marcos''

*Marcos (given name)

* Marcos family

Sports

;Surnamed

* Dayton Marcos, Negro league baseball team from Dayton, Ohio (early twentieth-century)

* Dimitris Markos, Greek footballer

* Né ...

administration, drug trafficking was punishable by firing-squad execution, as was done to Lim Seng. Execution by firing squad was later replaced by the electric chair

The electric chair is a specialized device used for capital punishment through electrocution. The condemned is strapped to a custom wooden chair and electrocuted via electrodes attached to the head and leg. Alfred P. Southwick, a Buffalo, New Yo ...

, then lethal injection

Lethal injection is the practice of injecting one or more drugs into a person (typically a barbiturate, paralytic, and potassium) for the express purpose of causing death. The main application for this procedure is capital punishment, but t ...

. On 24 June 2006, President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo

Maria Gloria Macaraeg Macapagal-Arroyo (; born April 5, 1947), often referred to as PGMA or GMA, is a Filipino academic and politician who served as the 14th president of the Philippines from Presidency of Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo, 2001 to 2010 ...

abolished capital punishment through the enactment of Republic Act No. 9346. Existing death row

Death row, also known as condemned row, is a place in a prison that houses inmates awaiting execution after being convicted of a capital crime and sentenced to death. The term is also used figuratively to describe the state of awaiting executio ...

inmates, who numbered in the thousands, were eventually given life sentence

Life imprisonment is any sentence of imprisonment under which the convicted individual is to remain incarcerated for the rest of their natural life (or until pardoned or commuted to a fixed term). Crimes that result in life imprisonment are c ...

s or reclusion perpetua instead.

Romania

Nicolae Ceaușescu

Nicolae Ceaușescu ( ; ; – 25 December 1989) was a Romanian politician who was the second and last Communism, communist leader of Socialist Romania, Romania, serving as the general secretary of the Romanian Communist Party from 1965 u ...

was executed by firing squad alongside his wife while singing the Communist Internationale following a show trial, bringing an end to the Romanian Revolution

The Romanian revolution () was a period of violent Civil disorder, civil unrest in Socialist Republic of Romania, Romania during December 1989 as a part of the revolutions of 1989 that occurred in several countries around the world, primarily ...

, on Christmas Day, 1989.

Russia/USSR

In Imperial Russia, firing squads were used in the army for executions during combat on the orders of military tribunals. In the Soviet Union, from the very earliest days, the bullet to the back of the head, in front of a ready-dug burial trench was by far the most common practice. It became especially widely used during theGreat Purge

The Great Purge, or the Great Terror (), also known as the Year of '37 () and the Yezhovshchina ( , ), was a political purge in the Soviet Union that took place from 1936 to 1938. After the Assassination of Sergei Kirov, assassination of ...

.

Saudi Arabia

Executions in Saudi Arabia are usually carried out by beheading; however, at times other methods have been used. Al-Beshi, a Saudi executioner, has said that he has conducted some executions by shooting. Mishaal bint Fahd bin Mohammed Al Saud, a Saudi princess, was also executed in the same way.South Africa

Two soldiers of the Bushveldt Carbineers,Breaker Morant

Harry Harbord "Breaker" Morant (born Edwin Henry Murrant, 9 December 1864 – 27 February 1902) was an English horseman, bush balladist, military officer, and war criminal who was convicted and executed for murdering nine prisoners-of-war ...

and Peter Handcock

Peter Joseph Handcock (17 February 1868 – 27 February 1902) was an Australian-born veterinary lieutenant and convicted war criminal who served in the Bushveldt Carbineers during the Boer War in South Africa.

After a court martial, Handcock ...

, were executed by a British firing squad in the South African Republic

The South African Republic (, abbreviated ZAR; ), also known as the Transvaal Republic, was an independent Boer republics, Boer republic in Southern Africa which existed from 1852 to 1902, when it was annexed into the British Empire as a result ...

on 27 February 1902 for war crime

A war crime is a violation of the laws of war that gives rise to individual criminal responsibility for actions by combatants in action, such as intentionally killing civilians or intentionally killing prisoners of war, torture, taking hostage ...

s they committed during the Second Boer War

The Second Boer War (, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, Transvaal War, Anglo–Boer War, or South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer republics (the South African Republic and ...

.

Spain

Since theSpanish transition to democracy

The Spanish transition to democracy, known in Spain as (; ) or (), is a period of History of Spain, modern Spanish history encompassing the regime change that moved from the Francoist dictatorship to the consolidation of a parliamentary system ...

in 1977 the new Spanish constitution

The Spanish Constitution () is the supreme law of the Kingdom of Spain. It was enacted after its approval in 1978 in a constitutional referendum; it represents the culmination of the Spanish transition to democracy.

The current version was a ...

prohibits the death penalty. Previously, execution by firing squad was reserved for cases under military jurisdiction. As in the rest of Europe, the death penalty ordered by a civil court was carried out by other methods clearly different from execution. In modern times, mainly by hanging

Hanging is killing a person by suspending them from the neck with a noose or ligature strangulation, ligature. Hanging has been a standard method of capital punishment since the Middle Ages, and has been the primary execution method in numerou ...

or garrote

A garrote ( ; alternatively spelled as garotte and similar variants)''Oxford English Dictionary'', 11th Ed: garrotte is normal British English spelling, with single r alternate. Article title is US English spelling variant. or garrote vil () is ...

.

During the decolonization of the Americas

The decolonization of the Americas occurred over several centuries as most of the countries in the Americas gained their independence from European rule. The American Revolution was the first in the Americas, and the British defeat in the Amer ...

, several heroes of the independence of the former viceroyalties were executed by firing squad, including Camilo Torres Tenorio, Antonio Baraya, Antonio Villavicencio

Antonio Villavicencio y Verástegui (January 9, 1775 – June 6, 1816) was a statesman and soldier of New Kingdom of Granada, New Granada, born in Quito, and educated in Spain. He served in the Battle of Trafalgar as an officer in the Spanish N ...

, José María Carbonell, Francisco José de Caldas, Jorge Tadeo Lozano, Policarpa Salavarrieta, María Antonia Santos Plata, José María Morelos

José María Teclo Morelos Pérez y Pavón () (30 September 1765 – 22 December 1815) was a Mexican Priesthood in the Catholic Church, Catholic priest, statesman and military leader who led the Mexican War of Independence movement, assuming it ...

, Mariano Matamoros

Mariano Matamoros y Guridi (August 14, 1770 – February 3, 1814) was a Mexican Roman Catholic priest and revolutionary rebel soldier of the Mexican War of Independence, who fought for independence against Spain in the early 19th century.

...

, etc.

At the time of the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War () was a military conflict fought from 1936 to 1939 between the Republican faction (Spanish Civil War), Republicans and the Nationalist faction (Spanish Civil War), Nationalists. Republicans were loyal to the Left-wing p ...

the phrase "''¡Al paredón!''" ("To the wall!") to express the death threat

A death threat is a threat, often made anonymously, by one person or a group of people to kill another person or group of people. These threats are often designed to intimidate victims in order to manipulate their behaviour, in which case a d ...

to whom certain blame is attributed to be summarily executed. "''Dar un paseo''" (Going for a walk) is the euphemism

A euphemism ( ) is when an expression that could offend or imply something unpleasant is replaced with one that is agreeable or inoffensive. Some euphemisms are intended to amuse, while others use bland, inoffensive terms for concepts that the u ...

of a series of violent episodes and political repression that occurred during the Spanish Civil War, which took place on both the Republican and the Nationalist factions, looking for victims with the excuse of taking them for a walk, which ended with the shooting in the open fields, often at night. It was an abbreviated murder procedure in the form of the '' Ley de fugas'' (Law for escapes). Sometimes common criminals participated in them.

Indalecio Prieto

Indalecio Prieto Tuero (30 April 1883 – 11 February 1962) was a Spanish politician, a minister and one of the leading figures of the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE) in the years before and during the Second Spanish Republic. Less radi ...

would define these executions in ''Letters to a sculptor: small details of great events'' as:"Executions without summary that were carried out in both areas of Spain and that dishonored us Spaniards on both sides equally".The last use of capital punishment in Spain took place on 27 September 1975 by firing squads for two members of the

terrorist

Terrorism, in its broadest sense, is the use of violence against non-combatants to achieve political or ideological aims. The term is used in this regard primarily to refer to intentional violence during peacetime or in the context of war aga ...

group ETA political-military and three members of the Revolutionary Antifascist Patriotic Front (FRAP).

United Arab Emirates

In theUnited Arab Emirates

The United Arab Emirates (UAE), or simply the Emirates, is a country in West Asia, in the Middle East, at the eastern end of the Arabian Peninsula. It is a Federal monarchy, federal elective monarchy made up of Emirates of the United Arab E ...

, firing squad is the preferred method of execution.

United Kingdom

The standard method of execution in the United Kingdom washanging

Hanging is killing a person by suspending them from the neck with a noose or ligature strangulation, ligature. Hanging has been a standard method of capital punishment since the Middle Ages, and has been the primary execution method in numerou ...

. Execution by firing squad was limited to times of war, armed insurrection

Rebellion is an uprising that resists and is organized against one's government. A rebel is a person who engages in a rebellion. A rebel group is a consciously coordinated group that seeks to gain political control over an entire state or a ...

and in the military

A military, also known collectively as armed forces, is a heavily armed, highly organized force primarily intended for warfare. Militaries are typically authorized and maintained by a sovereign state, with their members identifiable by a d ...

, although it is now outlawed in all circumstances, along with all other forms of capital punishment.

The Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic citadel and castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London, England. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamle ...

was used during both World Wars for executions. During World War I, eleven captured German spies were shot between 1914 and 1916: nine on the Tower's rifle range and two in the Tower Ditch, all of whom were buried in East London Cemetery, in Plaistow, London. On 15 August 1941, the last execution at the Tower was that of German Cpl. Josef Jakobs, shot for espionage during World War II.

Since the 1960s, there has been some controversy concerning the 346 British and Imperial troops—including 25 Canadians, 22 Irish and 5 New Zealanders—shot for desertion, murder, cowardice and other offences during World War I, some of whom are now thought to have been suffering from combat stress reaction

Combat stress reaction (CSR) is acute behavioral disorganization as a direct result of the trauma of war. Also known as "combat fatigue", "battle fatigue", "operational exhaustion", or "battle/war neurosis", it has some overlap with the diagnosis ...

or post-traumatic stress disorder

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a mental disorder that develops from experiencing a Psychological trauma, traumatic event, such as sexual assault, domestic violence, child abuse, warfare and its associated traumas, natural disaster ...

("shell-shock", as it was then known). This led to organisations such as the Shot at Dawn Campaign being set up in later years to try to uncover just why these soldiers were executed. The Shot at Dawn Memorial

The Shot at Dawn Memorial is a monument at the National Memorial Arboretum near Alrewas, in Staffordshire, England. It commemorates the 306 British Army and Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth soldiers executed after courts-martial for desertio ...

was erected at Staffordshire

Staffordshire (; postal abbreviation ''Staffs''.) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the West Midlands (region), West Midlands of England. It borders Cheshire to the north-west, Derbyshire and Leicestershire to the east, ...

to honour these soldiers. In August 2006 it was announced that 306 of these soldiers would receive posthumous pardons.

United States

American War of Independence

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was the armed conflict that comprised the final eight years of the broader American Revolution, in which Am ...

, General George Washington approved a sentence of death by firing squad, but the prisoner was later pardoned.

During the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

, 433 of the 573 men executed were shot dead by a firing squad: 186 of the 267 executed by the Union Army, and 247 of the 306 executed by the Confederate Army.

The United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the primary Land warfare, land service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is designated as the Army of the United States in the United States Constitution.Article II, section 2, clause 1 of th ...

carried out 10 executions by firing squad during World War II from 1942 to 1945, including Eddie Slovik, the only US soldier to be executed for desertion.

The United States Army took over Shepton Mallet prison in Somerset

Somerset ( , ), Archaism, archaically Somersetshire ( , , ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is bordered by the Bristol Channel, Gloucestershire, and Bristol to the north, Wiltshire to the east ...

, U.K. in 1942, renaming it Disciplinary Training Center No.1 and housing troops convicted of offences across Europe. There were eighteen executions at the prison, two of them by firing squad for murder: U.S. Army Pvt. Alexander Miranda on 30 May 1944 and Pvt. Benjamin Pygate on 28 November 1944. Locals complained about the noise, as the executions took place in the prison yard at 1:00am.

In 1913, Andriza Mircovich became the first and only inmate in Nevada

Nevada ( ; ) is a landlocked state in the Western United States. It borders Oregon to the northwest, Idaho to the northeast, California to the west, Arizona to the southeast, and Utah to the east. Nevada is the seventh-most extensive, th ...

to be executed by shooting. After the warden of Nevada State Prison could not find five men to form a firing squad, a shooting machine was built to carry out Mircovich's execution.

John W. Deering allowed an electrocardiogram recording of the effect of gunshot wounds on his heart during his 1938 execution by firing squad, and afterwards his body was donated to the

John W. Deering allowed an electrocardiogram recording of the effect of gunshot wounds on his heart during his 1938 execution by firing squad, and afterwards his body was donated to the University of Utah School of Medicine

The University of Utah School of Medicine is located on the upper campus of the University of Utah in Salt Lake City, Utah. It was founded in 1905 and is currently the only MD-granting medical school in the state of Utah.

History

The school bega ...

, at his request.

Since 1960 there have been six executions by firing squad, four in Utah

Utah is a landlocked state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is one of the Four Corners states, sharing a border with Arizona, Colorado, and New Mexico. It also borders Wyoming to the northea ...

and two in South Carolina

South Carolina ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders North Carolina to the north and northeast, the Atlantic Ocean to the southeast, and Georgia (U.S. state), Georg ...

: The 1960 execution of James W. Rodgers, Gary Gilmore's execution in 1977, John Albert Taylor in 1996, who chose a firing squad for his execution, according to ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

'', "to make a statement that Utah was sanctioning murder". However, a 2010 article for the British newspaper ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British Newspaper#Daily, daily Newspaper#National, national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its modern name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its si ...

'' quotes Taylor justifying his choice because he did not want to "flop around like a dying fish" during a lethal injection. Ronnie Lee Gardner was executed by firing squad in 2010, having said he preferred this method of execution because of his "Mormon

Mormons are a religious and cultural group related to Mormonism, the principal branch of the Latter Day Saint movement started by Joseph Smith in upstate New York during the 1820s. After Smith's death in 1844, the movement split into several ...

heritage". Gardner also felt that lawmakers were trying to eliminate the firing squad, in opposition to popular opinion in Utah, because of concern over the state's image in the 2002 Winter Olympics

The 2002 Winter Olympics, officially the XIX Olympic Winter Games and commonly known as Salt Lake 2002 (; Gosiute dialect, Gosiute Shoshoni: ''Tit'-so-pi 2002''; ; Shoshoni language, Shoshoni: ''Soónkahni 2002''), were an international wi ...

. Brad Sigmon was executed in South Carolina on March 7, 2025 after also opting a firing squad. On April 11, 2025, Mikal Mahdi became the second inmate to be executed by firing squad in South Carolina.

Execution by firing squad was banned in Utah in 2004, but as the ban was not retroactive, three inmates on Utah's death row

Death row, also known as condemned row, is a place in a prison that houses inmates awaiting execution after being convicted of a capital crime and sentenced to death. The term is also used figuratively to describe the state of awaiting executio ...

have the firing squad set as their method of execution. Idaho

Idaho ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest and Mountain states, Mountain West subregions of the Western United States. It borders Montana and Wyoming to the east, Nevada and Utah to the south, and Washington (state), ...

banned execution by firing squad in 2009, temporarily leaving Oklahoma

Oklahoma ( ; Choctaw language, Choctaw: , ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. It borders Texas to the south and west, Kansas to the north, Missouri to the northea ...

as the only state utilizing this method of execution (and only as a secondary method).

Reluctance by drug companies to see their drugs used to kill people has led to a shortage of the commonly used lethal injection drugs. In March 2015, Utah enacted legislation allowing for execution by firing squad if the drugs they use are unavailable. Several other states are also exploring a return to the firing squad. Thus, after waning in both use and popularity in recent decades, as of 2022, firing squad executions appear to be at least anecdotally regaining popularity as an alternative to lethal injection

Lethal injection is the practice of injecting one or more drugs into a person (typically a barbiturate, paralytic, and potassium) for the express purpose of causing death. The main application for this procedure is capital punishment, but t ...

.

On January 30, 2019, South Carolina's Senate voted 26–13 in favor of a revived proposal to bring back the electric chair and add firing squads to its execution options. On May 14, 2021, South Carolina Governor Henry McMaster

Henry Dargan McMaster (born May 27, 1947) is an American politician and attorney serving since 2017 as the 117th governor of South Carolina. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party, he was the 50th List of Attorneys Ge ...

signed a bill into law which brought back the electric chair

The electric chair is a specialized device used for capital punishment through electrocution. The condemned is strapped to a custom wooden chair and electrocuted via electrodes attached to the head and leg. Alfred P. Southwick, a Buffalo, New Yo ...

as the default method of execution (in the event lethal injection was unavailable) and added the firing squad to the list of execution options. South Carolina had not performed executions in over a decade, and its lethal injection drugs expired in 2013. Pharmaceutical companies have since refused to sell drugs for lethal injection.

On April 7, 2022, the South Carolina Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of South Carolina is the highest court in the U.S. state of South Carolina. The court is composed of a chief justice and four associate justices.

scheduled the execution of Richard Bernard Moore for April 29, 2022. On April 15, 2022, Moore chose to be executed by firing squad instead of the electric chair, however, his execution was later stayed by the South Carolina Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of South Carolina is the highest court in the U.S. state of South Carolina. The court is composed of a chief justice and four associate justices.

, and was executed on November 1, 2024 by lethal injection

Lethal injection is the practice of injecting one or more drugs into a person (typically a barbiturate, paralytic, and potassium) for the express purpose of causing death. The main application for this procedure is capital punishment, but t ...

.

On March 20, 2023, a firing squad bill passed the Idaho state legislature, and was signed by the governor.

In 2023, The Tennessee legislature debated about using the firing squad as a means of execution.

On February 7, 2025, the South Carolina Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of South Carolina is the highest court in the U.S. state of South Carolina. The court is composed of a chief justice and four associate justices.

scheduled the execution of Brad Sigmon for March 7, 2025. He was given the choice to die by lethal injection, firing squad, or electrocution, the latter of which his lawyers stated he did not want to die from. Due to concerns about the lethal injection doses, on February 21, 2025, Sigmon chose to die by firing squad. On March 7, 2025, at just after 6 PM EST, Sigmon was executed and pronounced dead a few minutes later.

Three weeks after Sigmon was executed, Mikal Mahdi, another prisoner from South Carolina's death row, also elected to be put to death by firing squad after receiving an execution date of April 11, 2025. He was executed as scheduled, becoming the fifth person in the United States and the second in South Carolina to be executed by this method. His execution is the most recent one to have been carried out by firing squad in the United States.

On March 12, 2025, Idaho Governor Brad Little

Bradley Jay Little (born February 15, 1954) is an American politician serving as the 33rd governor of Idaho since January 2019. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party, he served as the 42nd Lieutenant Governor of Idaho ...

signed a bill to designate firing squad

Firing may refer to:

* Dismissal (employment), sudden loss of employment by termination

* Firemaking, the act of starting a fire

* Burning; see combustion

* Shooting, specifically the discharge of firearms

* Execution by firing squad, a method of ...

as the primary execution method in the state. Idaho

Idaho ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest and Mountain states, Mountain West subregions of the Western United States. It borders Montana and Wyoming to the east, Nevada and Utah to the south, and Washington (state), ...

became the first state with such a policy.

As of 2025, Idaho, Mississippi, Oklahoma, South Carolina, and Utah are the only states that use firing squad for the death penalty.

See also

* Bullet fee * Use of capital punishment by countryReferences

Further reading

* Moore, William, ''The Thin Yellow Line'', Wordsworth Editions Ltd, 1974 * Putkowski and Sykes, ''Shot at Dawn'', Leo Cooper, 2006 * Hughs-Wilson, John and Corns, Cathryn M, ''Blindfold and Alone: British Military Executions in the Great War'', Cassell, 2005 * Johnson, David, ''Executed at Dawn: The British Firing Squads of the First World War'', History Press, 2015External links

Firing Squad Execution of a Civil War Deserter Described in an 1861 Newspaper

* ttp://www.thefirstpost.co.uk/64684,in-pictures,news-in-pictures,death-by-firing-squad Death by Firing Squad – slideshow by '' The First Post''

Nazis Meet the Firing Squad

– slideshow by ''

Life magazine

''Life'' (stylized as ''LIFE'') is an American magazine launched in 1883 as a weekly publication. In 1972, it transitioned to publishing "special" issues before running as a monthly from 1978 to 2000. Since then, ''Life'' has irregularly publi ...

''

{{DEFAULTSORT:Execution By Firing Squad

Firing squad

Firing may refer to:

* Dismissal (employment), sudden loss of employment by termination

* Firemaking, the act of starting a fire

* Burning; see combustion

* Shooting, specifically the discharge of firearms

* Execution by firing squad, a method of ...

Capital punishment

Gun violence