Eurypterus on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Eurypterus'' ( ) is an extinct

The largest arthropods to have ever existed were eurypterids. The largest known species ('' Jaekelopterus rhenaniae'') reached up to in length, about the size of a crocodile. Species of ''Eurypterus'', however, were much smaller.

''E. remipes'' are usually between in length. ''E. lacustris'' average at larger sizes at in length. However, a single

The largest arthropods to have ever existed were eurypterids. The largest known species ('' Jaekelopterus rhenaniae'') reached up to in length, about the size of a crocodile. Species of ''Eurypterus'', however, were much smaller.

''E. remipes'' are usually between in length. ''E. lacustris'' average at larger sizes at in length. However, a single  The ophisthosoma (the

The ophisthosoma (the

The genus ''Eurypterus'' derives from ''E. minor'', the oldest known species from the Llandovery of Scotland. ''E. minor'' is believed to have diverged from '' Dolichopterus macrocheirus'' sometime in the Llandovery. The following is the

The genus ''Eurypterus'' derives from ''E. minor'', the oldest known species from the Llandovery of Scotland. ''E. minor'' is believed to have diverged from '' Dolichopterus macrocheirus'' sometime in the Llandovery. The following is the

Species belonging to the genus, their diagnostic descriptions,

Species belonging to the genus, their diagnostic descriptions,

''Eurypterus'' belongs to the suborder Eurypterina, eurypterids in which the sixth appendage had developed a broad swimming paddle remarkably similar to that of the modern-day swimming crab. Modeling studies on ''Eurypterus'' swimming behavior suggest that they utilized a drag-based rowing type of locomotion where appendages moved synchronously in near-horizontal planes. The paddle blades are almost vertically oriented on the backward and down stroke, pushing the animal forward and lifting it up. The blades are then oriented horizontally on the recovery stroke to slash through the water without pushing the animal back. This type of swimming is exhibited by

''Eurypterus'' belongs to the suborder Eurypterina, eurypterids in which the sixth appendage had developed a broad swimming paddle remarkably similar to that of the modern-day swimming crab. Modeling studies on ''Eurypterus'' swimming behavior suggest that they utilized a drag-based rowing type of locomotion where appendages moved synchronously in near-horizontal planes. The paddle blades are almost vertically oriented on the backward and down stroke, pushing the animal forward and lifting it up. The blades are then oriented horizontally on the recovery stroke to slash through the water without pushing the animal back. This type of swimming is exhibited by  Trace fossil evidence indicates that ''Eurypterus'' employed a rowing stroke when in close proximity to the seafloor. '' Arcuites bertiensis'' is an

Trace fossil evidence indicates that ''Eurypterus'' employed a rowing stroke when in close proximity to the seafloor. '' Arcuites bertiensis'' is an

Examinations of the

Examinations of the

Members of ''Eurypterus'' existed for a relatively short time, yet they are the most abundant eurypterids found today. They flourished between the Late

Members of ''Eurypterus'' existed for a relatively short time, yet they are the most abundant eurypterids found today. They flourished between the Late  They are now only known from fossils from North America, Europe, and northwestern

They are now only known from fossils from North America, Europe, and northwestern

Eurypterid.co.uk

maintained by James Lamsdell

Eurypterids.net

maintained by Samuel J. Ciurca, Jr.

Fossil biomechanics

{{Taxonbar, from=Q2143015 Eurypteroidea Silurian eurypterids Paleontology in New York (state) Symbols of New York (state) Eurypterids of North America Paleozoic life of New Brunswick Paleozoic life of Nunavut Paleozoic life of Quebec Eurypterids of Europe Bertie Formation Fossil taxa described in 1825

genus

Genus (; : genera ) is a taxonomic rank above species and below family (taxonomy), family as used in the biological classification of extant taxon, living and fossil organisms as well as Virus classification#ICTV classification, viruses. In bino ...

of eurypterid

Eurypterids, often informally called sea scorpions, are a group of extinct marine arthropods that form the Order (biology), order Eurypterida. The earliest known eurypterids date to the Darriwilian stage of the Ordovician period, 467.3 Myr, mil ...

, a group of organisms commonly called "sea scorpions". The genus lived during the Silurian

The Silurian ( ) is a geologic period and system spanning 23.5 million years from the end of the Ordovician Period, at million years ago ( Mya), to the beginning of the Devonian Period, Mya. The Silurian is the third and shortest period of t ...

period, from around 432 to 418 million years ago. ''Eurypterus'' is by far the most well-studied and well-known eurypterid. ''Eurypterus'' fossil specimens probably represent more than 95% of all known eurypterid specimens.

There are fifteen species belonging to the genus ''Eurypterus'', the most common of which is ''E. remipes'', the first eurypterid fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserve ...

discovered and the state fossil

Most states in the US have designated a state fossil, many during the 1980s. It is common to designate a fossilized species, rather than a single specimen or a category of fossils. State fossils are distinct from other state emblems like state d ...

of New York.

Members of ''Eurypterus'' averaged at about in length, but the largest individual discovered was estimated to be long. They all possessed spine-bearing appendages and a large paddle they used for swimming. They were generalist species

A generalist species is able to thrive in a wide variety of environmental conditions and can make use of a variety of different natural resource, resources (for example, a heterotroph with a varied diet (nutrition), diet). A specialist species can ...

, equally likely to engage in predation

Predation is a biological interaction in which one organism, the predator, kills and eats another organism, its prey. It is one of a family of common List of feeding behaviours, feeding behaviours that includes parasitism and micropredation ...

or scavenging

Scavengers are animals that consume dead organisms that have died from causes other than predation or have been killed by other predators. While scavenging generally refers to carnivores feeding on carrion, it is also a herbivorous feeding be ...

.

Discovery

The first fossil of ''Eurypterus'' was found in 1818 by S. L. Mitchill, a fossil collector. It was recovered from the Bertie Formation of New York (near Westmoreland, Oneida County). Mitchill interpreted the appendages on the carapace asbarbels

In fish anatomy and turtle anatomy, a barbel is a slender, whisker like sensory organ near the mouth (sometimes called whiskers or tendrils). Fish that have barbels include the catfish, the carp, the goatfish, the hagfish, the sturgeon, the z ...

arising from the mouth. He consequently identified the fossil as a catfish

Catfish (or catfishes; order (biology), order Siluriformes or Nematognathi) are a diverse group of ray-finned fish. Catfish are common name, named for their prominent barbel (anatomy), barbels, which resemble a cat's whiskers, though not ...

of the genus '' Silurus''.

It was only after seven years, in 1825, that the American zoologist James Ellsworth De Kay identified the fossil correctly as an arthropod

Arthropods ( ) are invertebrates in the phylum Arthropoda. They possess an arthropod exoskeleton, exoskeleton with a cuticle made of chitin, often Mineralization (biology), mineralised with calcium carbonate, a body with differentiated (Metam ...

. He named it ''Eurypterus remipes'' and established the genus ''Eurypterus'' in the process. The name means 'wide wing' or 'broad paddle', referring to the swimming legs, from Greek ( 'wide') and ( 'wing').

However, De Kay thought ''Eurypterus'' was a branchiopod (a group of crustacean

Crustaceans (from Latin meaning: "those with shells" or "crusted ones") are invertebrate animals that constitute one group of arthropods that are traditionally a part of the subphylum Crustacea (), a large, diverse group of mainly aquatic arthrop ...

s which include fairy shrimps and water flea

The Diplostraca or Cladocera, commonly known as water fleas, is a superorder of small, mostly freshwater crustaceans, most of which feed on microscopic chunks of organic matter, though some forms are predatory.

Over 1000 species have been recog ...

s). Soon after, ''Eurypterus lacustris'' was also discovered in New York in 1835 by the paleontologist Richard Harlan. Another species was discovered in Estonia

Estonia, officially the Republic of Estonia, is a country in Northern Europe. It is bordered to the north by the Gulf of Finland across from Finland, to the west by the Baltic Sea across from Sweden, to the south by Latvia, and to the east by Ru ...

in 1858 by Jan Nieszkowski. He considered it to be of the same species as the first discovery (''E. remipes''); it is now known as ''E. tetragonophthalmus''. These specimens from Estonia are often of extraordinary quality, retaining the actual cuticle

A cuticle (), or cuticula, is any of a variety of tough but flexible, non-mineral outer coverings of an organism, or parts of an organism, that provide protection. Various types of "cuticle" are non- homologous, differing in their origin, structu ...

of their exoskeletons. In 1898, the Swedish paleontologist Gerhard Holm separated these fossils from the bedrock with acid

An acid is a molecule or ion capable of either donating a proton (i.e. Hydron, hydrogen cation, H+), known as a Brønsted–Lowry acid–base theory, Brønsted–Lowry acid, or forming a covalent bond with an electron pair, known as a Lewis ...

s. Holm was then able to examine the almost perfectly preserved fragments under a microscope. His remarkable study led to the modern breakthrough on eurypterid morphology

Morphology, from the Greek and meaning "study of shape", may refer to:

Disciplines

*Morphology (archaeology), study of the shapes or forms of artifacts

*Morphology (astronomy), study of the shape of astronomical objects such as nebulae, galaxies, ...

.

More fossils were recovered in great abundance in New York in the 19th century, and elsewhere in eastern Eurasia

Eurasia ( , ) is a continental area on Earth, comprising all of Europe and Asia. According to some geographers, Physical geography, physiographically, Eurasia is a single supercontinent. The concept of Europe and Asia as distinct continents d ...

and North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere, Northern and Western Hemisphere, Western hemispheres. North America is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South Ameri ...

. Today, ''Eurypterus'' remains one of the most commonly found and best known eurypterid genera, comprising more than 95% of all known eurypterid fossils.

''E. remipes'' was designated the New York State Fossil by the then Governor Mario Cuomo

Mario Matthew Cuomo ( , ; June 15, 1932 – January 1, 2015) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 52nd governor of New York for three terms, from 1983 to 1994. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic ...

in 1984.

Description

The largest arthropods to have ever existed were eurypterids. The largest known species ('' Jaekelopterus rhenaniae'') reached up to in length, about the size of a crocodile. Species of ''Eurypterus'', however, were much smaller.

''E. remipes'' are usually between in length. ''E. lacustris'' average at larger sizes at in length. However, a single

The largest arthropods to have ever existed were eurypterids. The largest known species ('' Jaekelopterus rhenaniae'') reached up to in length, about the size of a crocodile. Species of ''Eurypterus'', however, were much smaller.

''E. remipes'' are usually between in length. ''E. lacustris'' average at larger sizes at in length. However, a single telson

The telson () is the hindmost division of the body of an arthropod. Depending on the definition, the telson is either considered to be the final segment (biology), segment of the arthropod body, or an additional division that is not a true segm ...

(the posteriormost division of the body) of a specimen of this species reaches this length, being long and indicating a specimen of of length, and that is the largest specimen ever described in literature. In the introduction page of ''E. remipes'' in website of University of Texas at Austin

The University of Texas at Austin (UT Austin, UT, or Texas) is a public university, public research university in Austin, Texas, United States. Founded in 1883, it is the flagship institution of the University of Texas System. With 53,082 stud ...

says that the largest specimen ever found was long, currently on display at the Paleontological Research Institution of New York. However, the text section describes the group eurypterid itself rather than ''Eurypterus'', so it is not possible to determine in context whether the long specimen is actually from ''E. remipes'' or another eurypterid.

''Eurypterus'' fossils often occur in similar sizes in a given area. This may be a result of the fossils being "sorted" into windrow

A windrow is a row of cut (mown) hay or small grain crop. It is allowed to dry before being baled, combined, or rolled. For hay, the windrow is often formed by a hay rake, which rakes hay that has been cut by a mowing machine or by scythe ...

s as they were being deposited in shallow waters by storms and wave action.

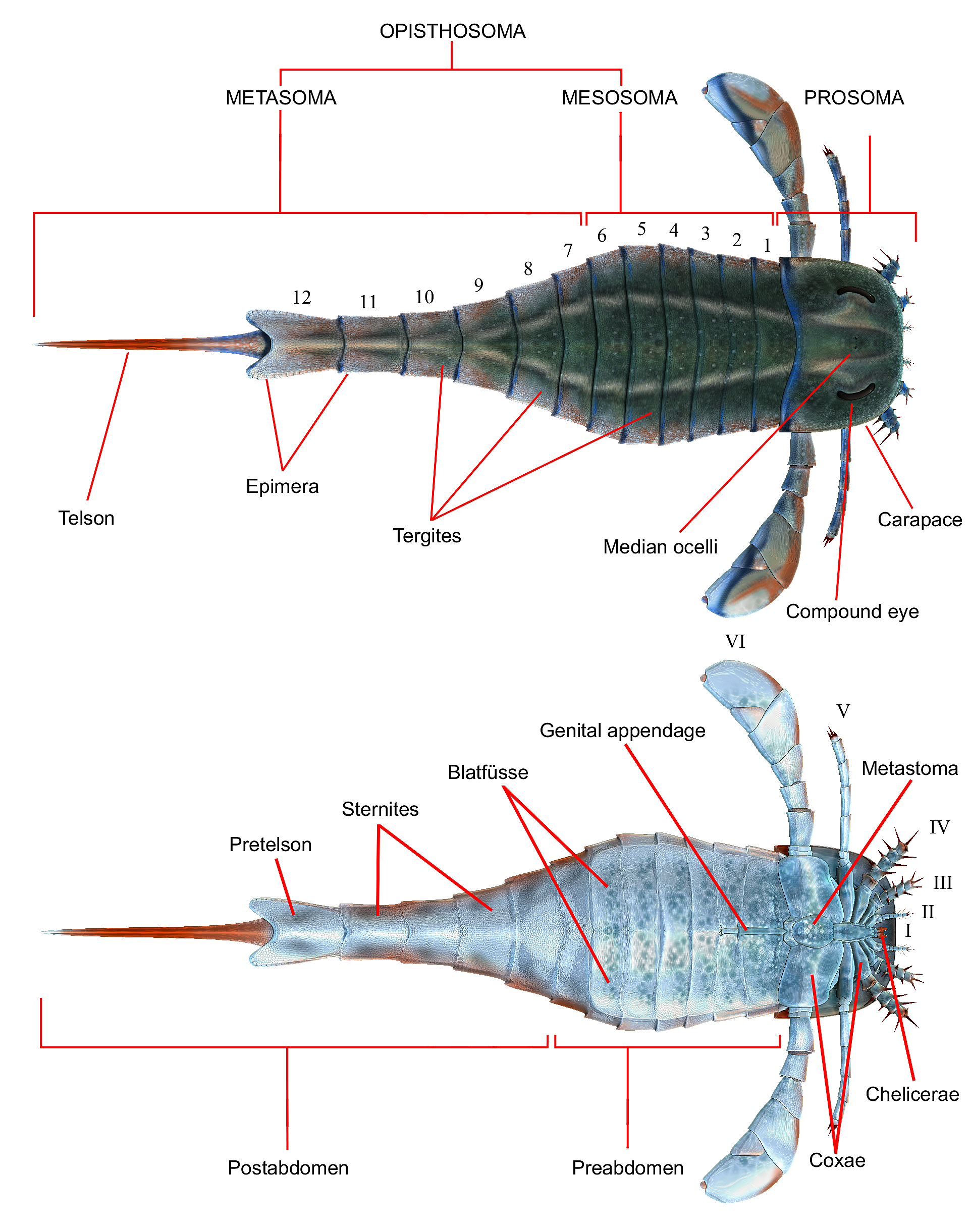

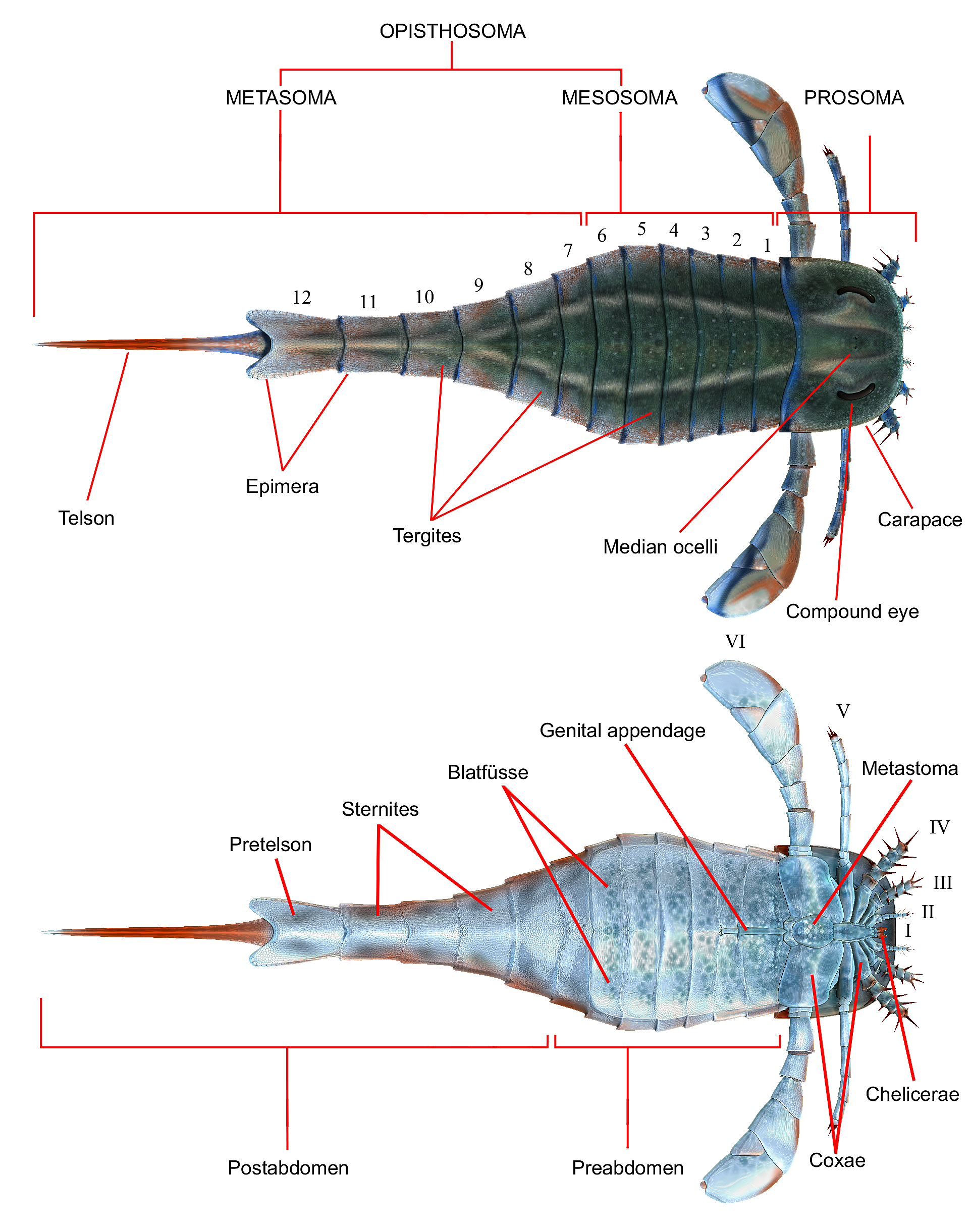

The ''Eurypterus'' body is broadly divided into two parts: the prosoma

The cephalothorax, also called prosoma in some groups, is a tagma of various arthropods, comprising the head and the thorax fused together, as distinct from the abdomen behind. (The terms ''prosoma'' and ''opisthosoma'' are equivalent to ''cepha ...

and the opisthosoma

The opisthosoma is the posterior part of the body in some arthropods, behind the prosoma ( cephalothorax). It is a distinctive feature of the subphylum Chelicerata (arachnids, horseshoe crabs and others). Although it is similar in most respects ...

(in turn divided into the mesosoma

The mesosoma is the middle part of the body, or tagma, of arthropods whose body is composed of three parts, the other two being the prosoma and the metasoma. It bears the legs, and, in the case of winged insects, the wings.

Wasps, bees and a ...

and the metasoma

The metasoma is the posterior part of the body, or tagma (biology), tagma, of arthropods whose body is composed of three parts, the other two being the prosoma and the mesosoma. In insects, it contains most of the digestive tract, respiratory sy ...

).

The prosoma is the forward part of the body, it is actually composed of six segments fused together to form the head and the thorax

The thorax (: thoraces or thoraxes) or chest is a part of the anatomy of mammals and other tetrapod animals located between the neck and the abdomen.

In insects, crustaceans, and the extinct trilobites, the thorax is one of the three main di ...

. It contains the semicircular to subrectangular platelike carapace

A carapace is a dorsal (upper) section of the exoskeleton or shell in a number of animal groups, including arthropods, such as crustaceans and arachnids, as well as vertebrates, such as turtles and tortoises. In turtles and tortoises, the unde ...

. On the dorsal side of the latter are two large crescent-shaped compound eyes. They also possessed two smaller light-sensitive simple eyes (the median ocelli

A simple eye or ocellus (sometimes called a pigment pit) is a form of eye or an optical arrangement which has a single lens without the sort of elaborate retina that occurs in most vertebrates. These eyes are called "simple" to distinguish the ...

) near the center of the carapace on a small elevation (known as the ocellar mound). Underneath the carapace is the mouth and six appendages

An appendage (or outgrowth) is an external body part or natural prolongation that protrudes from an organism's body such as an arm or a leg. Protrusions from single-celled bacteria and archaea are known as cell-surface appendages or surface app ...

, usually referred to in Roman numerals I-VI. Each appendage in turn is composed of nine segments (known as podomeres) labeled in Arabic numerals

The ten Arabic numerals (0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9) are the most commonly used symbols for writing numbers. The term often also implies a positional notation number with a decimal base, in particular when contrasted with Roman numera ...

1–9. The first segments which connect the appendages to the body are known as the coxa (plural coxae).

The first pair (Appendage I) are the chelicerae

The chelicerae () are the arthropod mouthparts, mouthparts of the subphylum Chelicerata, an arthropod group that includes arachnids, horseshoe crabs, and sea spiders. Commonly referred to as "jaws", chelicerae may be shaped as either articulated ...

, small pincer Pincer may refer to:

*Pincers (tool)

*Pincer (biology), part of an animal

*Pincer ligand, a terdentate, often planar molecule that tightly binds a variety of metal ions

*Pincer (Go), a move in the game of Go

*"Pincers!", an episode of the TV series ...

-like arms used for tearing food apart (mastication

Chewing or mastication is the process by which food is comminution, crushed and ground by the teeth. It is the first step in the process of digestion, allowing a greater surface area for digestive enzymes to break down the foods.

During the mast ...

) during feeding. After the chelicerae are three pairs of short legs (Appendages II, III, and IV). They are spiniferous, with predominantly two spines on each podomere and with the tipmost segment having a single spine. The last two segments are often indistinguishable and give the appearance of a single segment having three spines. They are used both for walking and for food capture. The next pair (Appendage V) is the most leg-like of all appendages, longer than the first three pairs and are mostly spineless except at the tipmost segments. The last pair (Appendage VI) are two broad paddle-like legs used for swimming. The coxae of Appendage VI are broad and flat, resembling an 'ear'.

The ophisthosoma (the

The ophisthosoma (the abdomen

The abdomen (colloquially called the gut, belly, tummy, midriff, tucky, or stomach) is the front part of the torso between the thorax (chest) and pelvis in humans and in other vertebrates. The area occupied by the abdomen is called the abdominal ...

) is composed of 12 segments, each consisting of a fused upper plate (tergite) and bottom plate (sternite). It is further subdivided in two ways.

Based on the width and structure of each segment, they can be divided into the broad preabdomen (segments 1 to 7) and the narrow postabdomen (segments 8 to 12). The preabdomen is the broader segments of the anterior portion of the ophisthosoma while the postabdomen are the last five segments of the ''Eurypterus body''. Each of the segments of the postabdomen contain lateral flattened protrusions known as the epimera with the exception of the last needle-like (styliform) part of the body known as the telson. The segment immediately preceding the telson (which also has the largest epimera of the postabdomen) is known as the pretelson.

An alternative way to divide the ophisthosoma is by function. It can also be divided into the mesosoma (segments 1 to 6), and the metasoma (segments 7 to 12). The mesosoma contains the gills and reproductive organs of ''Eurypterus''. Its ventral segments are overlaid by appendage-derived plates known as Blattfüsse (singular Blattfuss, German for "sheet foot"). Protected within which are the branchial chambers which contain the respiratory organs of ''Eurypterus''. The metasoma, meanwhile, do not possess Blattfüsse.

Some authors incorrectly use mesosoma and preabdomen interchangeably, as with metasoma and postabdomen.

The main respiratory organs of ''Eurypterus'' were what seems to be book gills, located in branchial chambers within the segments of the mesosoma. They may have been used for underwater respiration. They are composed of several layers of thin tissue stacked in such a way as to resemble the pages of a book, hence the name. In addition, they also possessed five pairs of oval-shaped areas covered with microscopic projections on the ceiling of the second branchial chambers within the mesosoma, immediately below the gill tracts. These areas are known as Kiemenplatten (or gill-tracts, though the former term is preferred). They are unique to eurypterids.

''Eurypterus'' are sexually dimorphic

Sexual dimorphism is the condition where sexes of the same species exhibit different Morphology (biology), morphological characteristics, including characteristics not directly involved in reproduction. The condition occurs in most dioecy, di ...

. On the bottom side of the first two segments of the mesosoma are central appendages used for reproduction. In females, they are long and narrow. In the males they are very short. A minority of authors, however, assume the reverse: longer genital appendage for males, shorter for females.

The exoskeleton

An exoskeleton () . is a skeleton that is on the exterior of an animal in the form of hardened integument, which both supports the body's shape and protects the internal organs, in contrast to an internal endoskeleton (e.g. human skeleton, that ...

of ''Eurypterus'' is often covered with small outgrowths known as ornamentation. They include pustules (small protrusions), scales

Scale or scales may refer to:

Mathematics

* Scale (descriptive set theory), an object defined on a set of points

* Scale (ratio), the ratio of a linear dimension of a model to the corresponding dimension of the original

* Scale factor, a number ...

, and striations. They vary by species and are used for identification. For more detailed diagnostic descriptions of each species under ''Eurypterus'', see sections below.

Classification

The genus ''Eurypterus'' belongs to thefamily

Family (from ) is a Social group, group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or Affinity (law), affinity (by marriage or other relationship). It forms the basis for social order. Ideally, families offer predictabili ...

Eurypteridae. They are classified under the superfamily Eurypteroidea, suborder

Order () is one of the eight major hierarchical taxonomic ranks in Linnaean taxonomy. It is classified between family and class. In biological classification, the order is a taxonomic rank used in the classification of organisms and recognized ...

Eurypterina

Eurypterina is one of two suborders of eurypterids, an extinct group of chelicerate arthropods commonly known as "sea scorpions". Eurypterine eurypterids are sometimes informally known as "swimming eurypterids". They are known from fossil depos ...

, order

Order, ORDER or Orders may refer to:

* A socio-political or established or existing order, e.g. World order, Ancien Regime, Pax Britannica

* Categorization, the process in which ideas and objects are recognized, differentiated, and understood

...

Eurypterida

Eurypterids, often informally called sea scorpions, are a group of extinct marine arthropods that form the order Eurypterida. The earliest known eurypterids date to the Darriwilian stage of the Ordovician period, 467.3 million years ago. The ...

, and the subphylum

In zoological nomenclature, a subphylum is a taxonomic rank below the rank of phylum.

The taxonomic rank of " subdivision" in fungi and plant taxonomy is equivalent to "subphylum" in zoological taxonomy. Some plant taxonomists have also used th ...

Chelicerata

The subphylum Chelicerata (from Neo-Latin, , ) constitutes one of the major subdivisions of the phylum Arthropoda. Chelicerates include the sea spiders, horseshoe crabs, and arachnids (including harvestmen, scorpions, spiders, solifuges, tic ...

. Until recently, eurypterids were thought to belong to the class

Class, Classes, or The Class may refer to:

Common uses not otherwise categorized

* Class (biology), a taxonomic rank

* Class (knowledge representation), a collection of individuals or objects

* Class (philosophy), an analytical concept used d ...

Merostomata along with order Xiphosura. It is now believed that eurypterids are a sister group

In phylogenetics, a sister group or sister taxon, also called an adelphotaxon, comprises the closest relative(s) of another given unit in an evolutionary tree.

Definition

The expression is most easily illustrated by a cladogram:

Taxon A and ...

to Arachnida

Arachnids are arthropods in the class Arachnida () of the subphylum Chelicerata. Arachnida includes, among others, spiders, scorpions, ticks, mites, pseudoscorpions, harvestmen, camel spiders, whip spiders and vinegaroons.

Adult arachnids ...

, closer to scorpion

Scorpions are predatory arachnids of the Order (biology), order Scorpiones. They have eight legs and are easily recognized by a pair of Chela (organ), grasping pincers and a narrow, segmented tail, often carried in a characteristic forward cur ...

s and spider

Spiders (order (biology), order Araneae) are air-breathing arthropods that have eight limbs, chelicerae with fangs generally able to inject venom, and spinnerets that extrude spider silk, silk. They are the largest order of arachnids and ran ...

s than to horseshoe crab

Horseshoe crabs are arthropods of the family Limulidae and the only surviving xiphosurans. Despite their name, they are not true crabs or even crustaceans; they are chelicerates, more closely related to arachnids like spiders, ticks, and scor ...

s.

''Eurypterus'' was the first recognized taxon

In biology, a taxon (back-formation from ''taxonomy''; : taxa) is a group of one or more populations of an organism or organisms seen by taxonomists to form a unit. Although neither is required, a taxon is usually known by a particular name and ...

of eurypterids and is the most common. As a consequence, nearly every remotely similar eurypterid in the 19th century was classified under the genus (except for the distinctive members of the family Pterygotidae and Stylonuridae). The genus was eventually split into several genera as the science of taxonomy

image:Hierarchical clustering diagram.png, 280px, Generalized scheme of taxonomy

Taxonomy is a practice and science concerned with classification or categorization. Typically, there are two parts to it: the development of an underlying scheme o ...

developed.

In 1958, several species distinguishable by closer placed eyes and spines on their swimming legs were split off into the separate genus '' Erieopterus'' by Erik Kjellesvig-Waering. Another split was proposed by Leif Størmer in 1973 when he reclassified some ''Eurypterus'' to ''Baltoeurypterus'' based on the size of some of the last segments of their swimming legs. O. Erik Tetlie in 2006 deemed these differences too insignificant to justify a separate genus. He merged ''Baltoeurypterus'' back into ''Eurypterus''. It is now believed that the minor variations described by Størmer are simply the differences found in adults and juveniles within a species.

The genus ''Eurypterus'' derives from ''E. minor'', the oldest known species from the Llandovery of Scotland. ''E. minor'' is believed to have diverged from '' Dolichopterus macrocheirus'' sometime in the Llandovery. The following is the

The genus ''Eurypterus'' derives from ''E. minor'', the oldest known species from the Llandovery of Scotland. ''E. minor'' is believed to have diverged from '' Dolichopterus macrocheirus'' sometime in the Llandovery. The following is the phylogenetic tree

A phylogenetic tree or phylogeny is a graphical representation which shows the evolutionary history between a set of species or taxa during a specific time.Felsenstein J. (2004). ''Inferring Phylogenies'' Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, MA. In ...

of ''Eurypterus'' based on phylogenetic studies by O. Erik Tetlie in 2006. Some species are not represented.

Species

Species belonging to the genus, their diagnostic descriptions,

Species belonging to the genus, their diagnostic descriptions, synonyms

A synonym is a word, morpheme, or phrase that means precisely or nearly the same as another word, morpheme, or phrase in a given language. For example, in the English language, the words ''begin'', ''start'', ''commence'', and ''initiate'' are a ...

(if present), and distribution Distribution may refer to:

Mathematics

*Distribution (mathematics), generalized functions used to formulate solutions of partial differential equations

*Probability distribution, the probability of a particular value or value range of a varia ...

are as follows:

''Eurypterus'' De Kay, 1825

*?''Eurypterus cephalaspis'' Salter, 1856 – Silurian, England

::Uncertain placement. Only 3 of the specimens described in 1856 are probably ''Eurypterus'', the rest probably belonged to Hughmilleriidae. Its name means 'shield head', from Greek ( 'head'), and ( 'shield or bowl'). Specimens recovered from Herefordshire

Herefordshire ( ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the West Midlands (region), West Midlands of England, bordered by Shropshire to the north, Worcestershire to the east, Gloucestershire to the south-east, and the Welsh ...

, England.

*''Eurypterus dekayi'' Hall, 1859 – Silurian, United States & Canada

::No raised scales on the posterior margin of the carapace or of the three front-most tergites. The rest of the tergites each have four raised scales. Four to six spines on each podomere of Appendages III and IV. Pretelson has large, rounded epimera without ornamentation on the margins. The species is very similar to ''E. laculatus''. The species is named after James Ellsworth De Kay. Specimens recovered from New York and Ontario

Ontario is the southernmost Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada. Located in Central Canada, Ontario is the Population of Canada by province and territory, country's most populous province. As of the 2021 Canadian census, it ...

.

*''Eurypterus flintstonensis'' Swartz, 1923 – Silurian, USA

::Probably a synonym

A synonym is a word, morpheme, or phrase that means precisely or nearly the same as another word, morpheme, or phrase in a given language. For example, in the English language, the words ''begin'', ''start'', ''commence'', and ''initiate'' are a ...

of ''E. remipes'' or ''E. lacustris''. Probably named after Flintstone, Georgia (?). Specimen recovered from eastern United States.

*''Eurypterus hankeni'' Tetlie, 2006 – Silurian, Norway

::Small ''Eurypterus'' species, averaging at long. The largest specimen found is about in length. They can be distinguished by pustules and six scales at the rear margin of their carapaces. Appendages I to IV has two spines on each podomere. The postabdomen have small epimera. The pretelson has long pointed epimera. Telson has striations near its attachment to the pretelson. The species is named after Norwegian paleontologist Nils-Martin Hanken, of the University of Tromsø

The University of Tromsø – The Arctic University of Norway ( Norwegian: ''Universitetet i Tromsø – Norges arktiske universitet''; Northern Sami: ''Romssa universitehta – Norgga árktalaš universitehta'') is a state university in Norway a ...

. Found in the Steinsfjorden Formation of Ringerike, Norway.

*''Eurypterus henningsmoeni'' Tetlie, 2002 – Silurian, Norway

::''Eurypterus'' with broad paddles and metastoma. Postabdomen has small epimera. Pretelson has large rounded epimera with imbricate scales (overlapping, similar to fish scales). It is very similar and closely related to ''E. tetragonophthalmus''. The species was named after the Norwegian paleontologist Gunnar Henningsmoen. Found in Bærum

Bærum () is a list of municipalities of Norway, municipality in the Greater Oslo Region in Akershus County, Norway. It forms an affluent suburb of Oslo on the west coast of the city. Bærum is Norway's fifth largest municipality with a populatio ...

, Norway.

*''Eurypterus laculatus'' Kjellesvig-Waering, 1958 – Silurian, USA & Canada

::The visual area of the compound eyes of this species are surrounded by depressions. The ocelli and the ocellar mound are small. No pustules or raised scales on the carapace or the first tergite. It is probably closely related to ''E. dekayi''. Its specific epithet means 'four-cornered', from Latin ('four-cornered, checkered'). Found in New York and Ontario.

*''Eurypterus lacustris'' Harlan, 1834 – Silurian, USA & Canada

:::= ''Eurypterus pachycheirus '' Hall, 1859 – Silurian, USA & Canada

:::= ''Eurypterus robustus'' Hall, 1859 – Silurian, USA & Canada

::One of the two most common ''Eurypterus'' fossils found. It is very similar to ''E. remipes'' and often found in the same localities, but the eyes are placed at a more posterior position on the carapace of ''E. lacustris''. It is also slightly larger with a slightly narrower metastoma. Its status as a distinct species was once disputed before diagnostic analysis by Tollerton in 1993. Its specific name means 'from a lake', from Latin ('lake'). Found in New York and Ontario.

*''Eurypterus leopoldi'' Tetlie, 2006 – Silurian, Canada

::Frontmost tergite is reduced. Metasoma is rhombiovate in shape with tooth-like projections at the anterior part. The pretelson has serrated edges. the epimera are large, semi-angular with angular striations. The telson is styliform with large angular striations interspersed among smaller more numerous striations. The species is named after Port Leopold and the Leopold Formation where they were collected. Found in the Leopold Formation of Somerset Island, Canada.

*''Eurypterus megalops'' Clarke & Ruedemann, 1912 – Silurian, USA

::Specific name means "large eye", from Greek ( 'big or large') and ( 'eye'). Discovered in New York, United States.

*?''Eurypterus minor'' Laurie, 1899 – Silurian, Scotland

::Small ''Eurypterus'' with large pustules on the carapace and abdomen. Does not possess the scale ornamentation found in other species of ''Eurypterus''. It is the earliest known species of ''Eurypterus''. They have large palpebral lobes (part of "cheeks" of the carapace adjacent to the compound eyes), making it easy to mistake their eyes for being oval. This enlargement is more typical of the genus '' Dolichopterus'' and it may actually belong to Dolichopteridae. The specific name means 'smaller', from Latin . Found in the Reservoir Formation of Pentland Hills, Scotland.

*''Eurypterus ornatus'' Leutze, 1958 – Silurian, USA

::Ornamentation of pustules on the entire surface of the carapace and at least the first tergite. Does not possess raised scales. Its specific name means 'adorned', from Latin ('adorned, ornate'). Recovered from Fayette, Ohio

Ohio ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders Lake Erie to the north, Pennsylvania to the east, West Virginia to the southeast, Kentucky to the southwest, Indiana to the ...

.

*''Eurypterus pittsfordensis'' Sarle, 1903 – Silurian, USA

::The posterior margin of the carapace has three raised scales. Appendages II to IV has two spines per podomere. The metastoma is rhomboid in shape with a deep notch at the front part. The postabdomen has serrated fringes at the middle with small angular epimera at the sides. The pretelson has large, semiangular epimera with angular striations at the margins. The telson is styliform with sparse angular striations at the margins. The name of the species comes from its place of discovery – the Salina shale formations of Pittsford, New York.

*''Eurypterus quebecensis'' Kjellesvig-Waering, 1958 – Silurian, Canada

::Has six raised scales on the posterior margin of the carapace but does not possess pustule ornamentation. It is named after the location it was recovered from Quebec

Quebec is Canada's List of Canadian provinces and territories by area, largest province by area. Located in Central Canada, the province shares borders with the provinces of Ontario to the west, Newfoundland and Labrador to the northeast, ...

, Canada.

*''Eurypterus remipes'' DeKay, 1825 – Silurian, USA, Canada

:::= ''Carcinosoma trigona'' (Ruedemann, 1916) – Silurian, USA

::The most common ''Eurypterus'' species. Has four raised scales at the posterior margin of the carapace. Appendages I to IV has two spines on each podomere. Postabdomen has small epimera. Pretelson has small, semiangular epimera with imbricate scale ornamentation at the margins. The telson has serrated margins along most of its length. It is very similar to ''E. lacustris'' and can often only be distinguished by the position of the eyes. The specific name means 'oar-foot', from Latin ('oar') and ('foot'). Found in New York and Ontario, and is the state fossil of New York.

*''Eurypterus serratus'' (Jones & Woodward, 1888) – Silurian, Sweden

::Similar to ''E. pittsfordensis'' and ''E. leopoldi'' but can be distinguished by the dense angular striations on their styliform telson. The specific name means 'serrated', from Latin ('sawn nto pieces). Originally discovered from Gotland

Gotland (; ; ''Gutland'' in Gutnish), also historically spelled Gottland or Gothland (), is Sweden's largest island. It is also a Provinces of Sweden, province/Counties of Sweden, county (Swedish län), Municipalities of Sweden, municipality, a ...

, Sweden.

*''Eurypterus tetragonophthalmus'' Fischer, 1839 – Silurian, Ukraine & Estonia

:::= ''Eurypterus fischeri'' Eichwald, 1854 – Silurian, Ukraine

:::= ''Eurypterus fischeri '' var. ''rectangularis'' Schmidt, 1883 – Silurian, Estonia

::Four raised scales on the posterior margin of the carapce. Appendages II to IV each have two spines on each podomere. Postabdomen has small epimera. The pretelson has large, rounded epimera with imbricate scale ornamentation at the margins. Telson has imbricate scale ornamentations at the margins of the base which become serrations towards the tip. The specific name means 'four-edged eye', from Greek ( 'four'), ( 'angle'), and ( 'eye'). Found in the Rootsiküla Formation of Saaremaa

Saaremaa (; ) is the largest and most populous island in Estonia. Measuring , its population is 31,435 (as of January 2020). The main island of the West Estonian archipelago (Moonsund archipelago), it is located in the Baltic Sea, south of Hi ...

(Ösel), Estonia, with additional discoveries in Ukraine, Norway, and possibly Moldova and Romania.

The list does not include the large number of fossils previously classified under ''Eurypterus''. Most of them are now reclassified to other genera, identified as other animals (like crustacean

Crustaceans (from Latin meaning: "those with shells" or "crusted ones") are invertebrate animals that constitute one group of arthropods that are traditionally a part of the subphylum Crustacea (), a large, diverse group of mainly aquatic arthrop ...

s) or pseudofossils, or remains of doubtful placement. Classification is based on Dunlop ''et al.''(2011).

Paleobiology

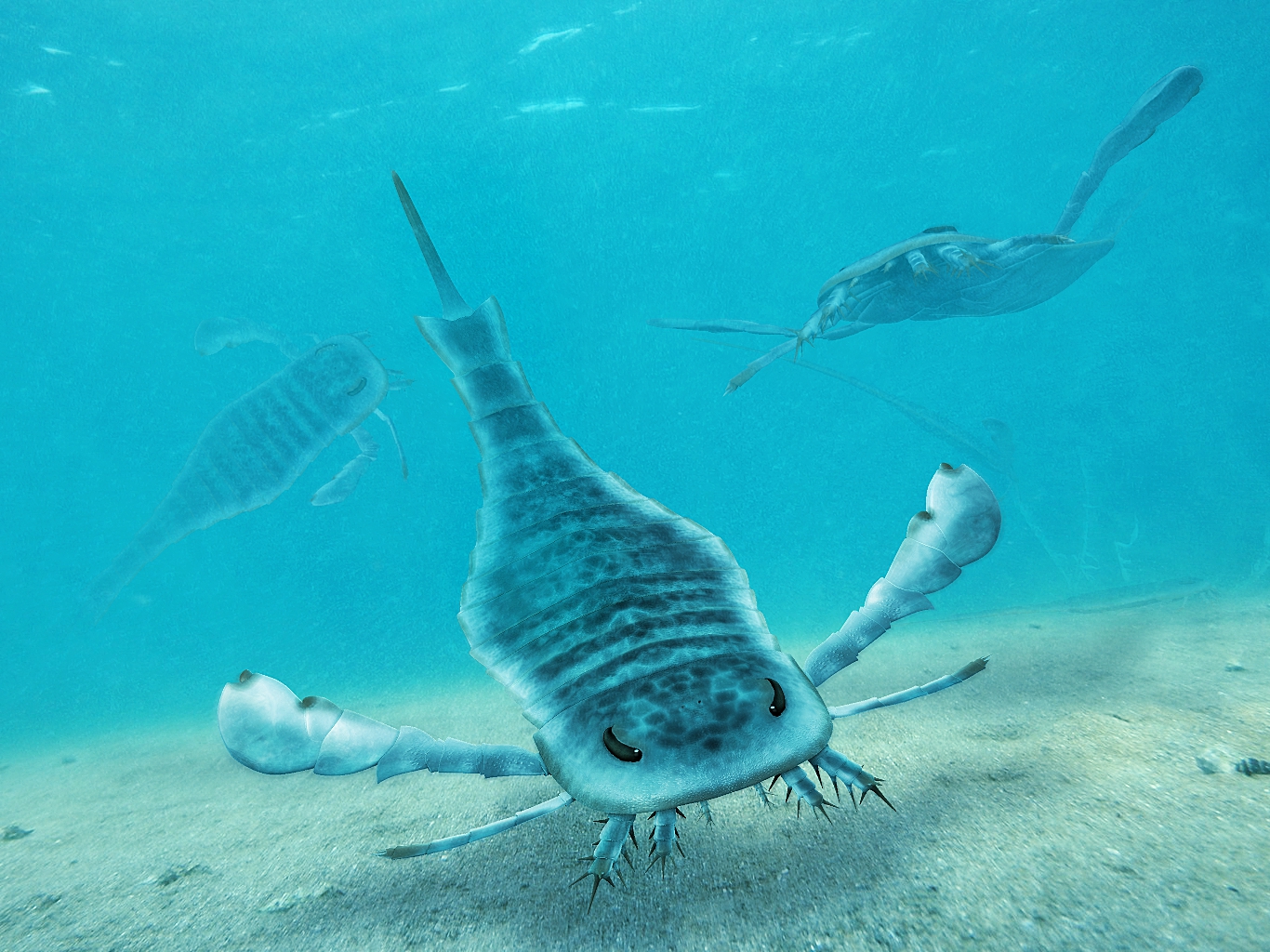

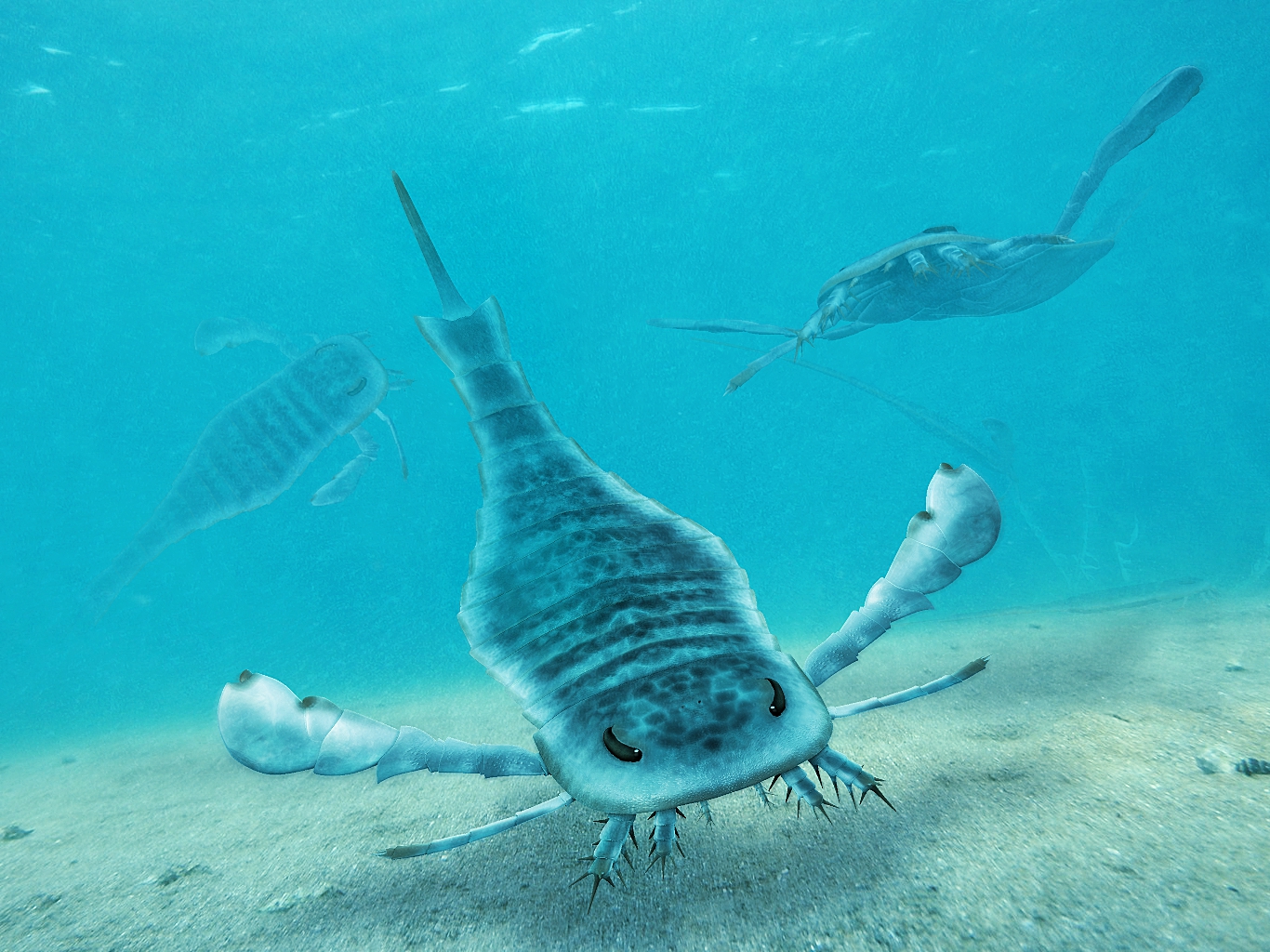

''Eurypterus'' belongs to the suborder Eurypterina, eurypterids in which the sixth appendage had developed a broad swimming paddle remarkably similar to that of the modern-day swimming crab. Modeling studies on ''Eurypterus'' swimming behavior suggest that they utilized a drag-based rowing type of locomotion where appendages moved synchronously in near-horizontal planes. The paddle blades are almost vertically oriented on the backward and down stroke, pushing the animal forward and lifting it up. The blades are then oriented horizontally on the recovery stroke to slash through the water without pushing the animal back. This type of swimming is exhibited by

''Eurypterus'' belongs to the suborder Eurypterina, eurypterids in which the sixth appendage had developed a broad swimming paddle remarkably similar to that of the modern-day swimming crab. Modeling studies on ''Eurypterus'' swimming behavior suggest that they utilized a drag-based rowing type of locomotion where appendages moved synchronously in near-horizontal planes. The paddle blades are almost vertically oriented on the backward and down stroke, pushing the animal forward and lifting it up. The blades are then oriented horizontally on the recovery stroke to slash through the water without pushing the animal back. This type of swimming is exhibited by crab

Crabs are decapod crustaceans of the infraorder Brachyura (meaning "short tailed" in Greek language, Greek), which typically have a very short projecting tail-like abdomen#Arthropoda, abdomen, usually hidden entirely under the Thorax (arthropo ...

s and water beetles.

An alternative hypothesis for ''Eurypterus'' swimming behavior is that individuals were capable of underwater flying (or subaqueous flight), in which the sinuous motions and shape of the paddles themselves acting as hydrofoil

A hydrofoil is a lifting surface, or foil, that operates in water. They are similar in appearance and purpose to aerofoils used by aeroplanes. Boats that use hydrofoil technology are also simply termed hydrofoils. As a hydrofoil craft gains sp ...

s are enough to generate lift. This type is similar to that found in sea turtle

Sea turtles (superfamily Chelonioidea), sometimes called marine turtles, are reptiles of the order Testudines and of the suborder Cryptodira. The seven existing species of sea turtles are the flatback, green, hawksbill, leatherback, loggerh ...

s and sea lion

Sea lions are pinnipeds characterized by external ear flaps, long foreflippers, the ability to walk on all fours, short and thick hair, and a big chest and belly. Together with the fur seals, they make up the family Otariidae, eared seals. ...

s. It has a relatively slower acceleration rate than the rowing type, especially since adults have proportionally smaller paddles than juveniles. But since the larger sizes of adults mean a higher drag coefficient, using this type of propulsion is more energy-efficient.

Juveniles probably swam using the rowing type, the rapid acceleration afforded by this propulsion is more suited for quickly escaping predators. A small ''Eurypterus'' could achieve two and a half body lengths per second immediately. Larger adults, meanwhile, probably swam with the subaqueous flight type. The maximum velocity of adults when cruising would have been per second, slightly faster than turtles and sea otter

The sea otter (''Enhydra lutris'') is a marine mammal native to the coasts of the northern and eastern Pacific Ocean, North Pacific Ocean. Adult sea otters typically weigh between , making them the heaviest members of ...

s.

Trace fossil evidence indicates that ''Eurypterus'' employed a rowing stroke when in close proximity to the seafloor. '' Arcuites bertiensis'' is an

Trace fossil evidence indicates that ''Eurypterus'' employed a rowing stroke when in close proximity to the seafloor. '' Arcuites bertiensis'' is an ichnospecies

An ichnotaxon (plural ichnotaxa) is "a taxon based on the fossilized work of an organism", i.e. the non-human equivalent of an artifact. ''Ichnotaxon'' comes from the Ancient Greek (''íchnos'') meaning "track" and English , itself derived from ...

that includes a pair of crescent-shaped impressions and a short medial drag, and it has been found in upper Silurian eurypterid Lagerstatten in Ontario and Pennsylvania. This trace fossil is very similar to traces made by modern aquatic swimming insects that row such as water boatmen, and is considered to have been made by juvenile to adult-sized eurypterids while swimming in very shallow nearshore marine environments. The morphology of '' A. bertiensis'' suggests that ''Eurypterus'' had the ability to move its swimming appendages in both the horizontal and vertical plane.

''Eurypterus'' did not swim to hunt, rather they simply swam in order to move from one feeding site to another quickly. Most of the time they walked on the substrate with their legs (including their swimming leg). They were generalist species

A generalist species is able to thrive in a wide variety of environmental conditions and can make use of a variety of different natural resource, resources (for example, a heterotroph with a varied diet (nutrition), diet). A specialist species can ...

, equally likely to engage in predation

Predation is a biological interaction in which one organism, the predator, kills and eats another organism, its prey. It is one of a family of common List of feeding behaviours, feeding behaviours that includes parasitism and micropredation ...

or scavenging

Scavengers are animals that consume dead organisms that have died from causes other than predation or have been killed by other predators. While scavenging generally refers to carnivores feeding on carrion, it is also a herbivorous feeding be ...

. They hunted small soft-bodied invertebrate

Invertebrates are animals that neither develop nor retain a vertebral column (commonly known as a ''spine'' or ''backbone''), which evolved from the notochord. It is a paraphyletic grouping including all animals excluding the chordata, chordate s ...

s like worms. They utilized the mass of spines on their front appendages to both kill and hold them while they used their chelicerae to rip off pieces small enough to swallow. Young individuals may also have fallen prey to cannibalism

Cannibalism is the act of consuming another individual of the same species as food. Cannibalism is a common ecological interaction in the animal kingdom and has been recorded in more than 1,500 species. Human cannibalism is also well document ...

by larger adults.

''Eurypterus'' were most probably marine animals, as their remains are mostly found in intertidal shallow environments. The concentrations of ''Eurypterus'' fossils in certain sites has been interpreted to be a result of mass mating and molting behavior. Juveniles were likely to have inhabited nearshore hypersaline environments, safer from predators, and moved to deeper waters as they grew older and larger. Adults that reach sexual maturity would then migrate en masse to shore areas in order to mate, lay eggs, and molt. Activities that would have made them more vulnerable to predators. This could also explain why the vast majority of fossils found in such sites are molts and not of actual animals. The same behavior can be seen in modern horseshoe crabs.

Respiration

Examinations of the

Examinations of the respiratory system

The respiratory system (also respiratory apparatus, ventilatory system) is a biological system consisting of specific organs and structures used for gas exchange in animals and plants. The anatomy and physiology that make this happen varies grea ...

s of ''Eurypterus'' have led many paleontologists to conclude that it was capable of breathing air and walking on land for a short amount of time. ''Eurypterus'' had two types of respiratory systems. Its main organs for breathing were the book gills inside the segments of the mesosoma. These structures were supported by semicircular 'ribs' and were probably attached near the center of the body, similar to the gills of modern horseshoe crabs. They were protected under platelike appendages (which actually formed the apparent 'belly' of ''Eurypterus'') known as Blattfüsse. These gills may have also played a role in osmoregulation

Osmoregulation is the active regulation of the osmotic pressure of an organism's body fluids, detected by osmoreceptors, to maintain the homeostasis of the organism's water content; that is, it maintains the fluid balance and the concentration ...

.

The second system are the Kiemenplatten, also referred to as gill-tracts. These oval-shaped areas within the body wall of the preabdomen. Their surfaces are covered with numerous small spines arranged into hexagonal 'rosettes'. These areas were vascularized, hence the conclusion that they were secondary breathing organs.

The function of the book gills are usually interpreted to be for aquatic breathing, while the Kiemenplatten are supplementary for temporary breathing on land. However, some authors have argued that the two systems alone could not have supported an organism the size of ''Eurypterus''. Both structures might actually have been for breathing air and the true gills (for underwater breathing) of ''Eurypterus'' have yet to be discovered. ''Eurypterus'', however, were undoubtedly primarily aquatic.

Ontogeny

Juvenile ''Eurypterus'' differed from adults in several ways. Their carapaces were narrower and longer ( parabolic) in contrast to the trapezoidal carapaces of adults. The eyes are aligned almost laterally but move to a more anterior location during growth. The preabdomen also lengthened, increasing the overall length of the ophisthosoma. The swimming legs also became narrower and the telsons shorter and broader (though in ''E. tetragonophthalmus'' and ''E. henningsmoeni'' the telsons changed from being angular in juveniles to larger and more rounded in adults). All these changes are believed to be a result of the respiratory and reproductive requirements of adults.Paleoecology

Members of ''Eurypterus'' existed for a relatively short time, yet they are the most abundant eurypterids found today. They flourished between the Late

Members of ''Eurypterus'' existed for a relatively short time, yet they are the most abundant eurypterids found today. They flourished between the Late Llandovery

Llandovery (; ) is a market town and community (Wales), community in Carmarthenshire, Wales. It lies on the River Tywi and at the junction of the A40 road, A40 and A483 road, A483 roads, about north-east of Carmarthen, north of Swansea and w ...

epoch

In chronology and periodization, an epoch or reference epoch is an instant in time chosen as the origin of a particular calendar era. The "epoch" serves as a reference point from which time is measured.

The moment of epoch is usually decided b ...

(around 432 million years ago) to sometime during the Přídolí epoch (418.1 million years ago) of the Silurian period. A span of only around 10 to 14 million years.

During this period, the landmasses were mostly restricted to the southern hemisphere of the Earth, with the supercontinent

In geology, a supercontinent is the assembly of most or all of Earth's continent, continental blocks or cratons to form a single large landmass. However, some geologists use a different definition, "a grouping of formerly dispersed continents", ...

Gondwana

Gondwana ( ; ) was a large landmass, sometimes referred to as a supercontinent. The remnants of Gondwana make up around two-thirds of today's continental area, including South America, Africa, Antarctica, Australia (continent), Australia, Zea ...

straddling the South Pole. The equator had three continents (Avalonia

Avalonia was a microcontinent in the Paleozoic era. Crustal fragments of this former microcontinent are terranes in parts of the eastern coast of North America: Atlantic Canada, and parts of the East Coast of the United States, East Coast of the ...

, Baltica

Baltica is a paleocontinent that formed in the Paleoproterozoic and now constitutes northwestern Eurasia, or Europe north of the Trans-European Suture Zone and west of the Ural Mountains.

The thick core of Baltica, the East European Craton, i ...

, and Laurentia

Laurentia or the North American craton is a large continental craton that forms the Geology of North America, ancient geological core of North America. Many times in its past, Laurentia has been a separate continent, as it is now in the form of ...

) which slowly drifted together to form the second supercontinent of Laurussia

Laurasia () was the more northern of two large landmasses that formed part of the Pangaea supercontinent from around (Million years ago, Mya), the other being Gondwana. It separated from Gondwana (beginning in the late Triassic period) during ...

(also known as Euramerica

Laurasia () was the more northern of two large landmasses that formed part of the Pangaea supercontinent from around ( Mya), the other being Gondwana. It separated from Gondwana (beginning in the late Triassic period) during the breakup of Pa ...

, not to be confused with Laurasia

Laurasia () was the more northern of two large landmasses that formed part of the Pangaea supercontinent from around ( Mya), the other being Gondwana. It separated from Gondwana (beginning in the late Triassic period) during the breakup of Pa ...

).

The ancestors of ''Eurypterus'' were believed to have originated from Baltica (eastern Laurussia, modern western Eurasia) based on the earliest recorded fossils. During the Silurian, they spread to Laurentia (western Laurussia, modern North America) when the two continents began to collide. They rapidly colonized the continent as invasive species

An invasive species is an introduced species that harms its new environment. Invasive species adversely affect habitats and bioregions, causing ecological, environmental, and/or economic damage. The term can also be used for native spec ...

, becoming the most dominant eurypterid in the region. This accounts for why they are the most commonly found genus of eurypterids today. ''Eurypterus'' (and other members of Eurypteroidea), however, were unable to cross vast expanses of oceans between the two supercontinents during the Silurian. Their range

Range may refer to:

Geography

* Range (geographic), a chain of hills or mountains; a somewhat linear, complex mountainous or hilly area (cordillera, sierra)

** Mountain range, a group of mountains bordered by lowlands

* Range, a term used to i ...

were thus limited to the coastlines and the large, shallow, and hypersaline inland seas of Laurussia.

They are now only known from fossils from North America, Europe, and northwestern

They are now only known from fossils from North America, Europe, and northwestern Asia

Asia ( , ) is the largest continent in the world by both land area and population. It covers an area of more than 44 million square kilometres, about 30% of Earth's total land area and 8% of Earth's total surface area. The continent, which ...

, craton

A craton ( , , or ; from "strength") is an old and stable part of the continental lithosphere, which consists of Earth's two topmost layers, the crust and the uppermost mantle. Having often survived cycles of merging and rifting of contine ...

s that were the former components of Laurussia. While three species of ''Eurypterus'' were purportedly discovered in China in 1957, the evidence of them belonging to the genus (or if they were even eurypterids at all) is nonexistent. No other traces of ''Eurypterus'' in modern continents from Gondwana are currently known.

''Eurypterus'' are very common fossils in their regions of occurrence, millions of specimens are possible in a given area, though access to the rock formations

A rock formation is an isolated, scenic, or spectacular surface rock (geology), rock outcrop. Rock formations are usually the result of weathering and erosion sculpting the existing rock. The term ''rock Geological formation, formation ...

may be difficult. Most fossil eurypterids are the disjointed shed exoskeleton (known as exuvia

In biology, exuviae are the remains of an exoskeleton and related structures that are left after ecdysozoans (including insects, crustaceans and arachnids) have molted. The exuviae of an animal can be important to biologists as they can often b ...

e) of individuals after molting (ecdysis

Ecdysis is the moulting of the cuticle in many invertebrates of the clade Ecdysozoa. Since the cuticle of these animals typically forms a largely inelastic exoskeleton, it is shed during growth and a new, larger covering is formed. The remnant ...

). Some are complete but are most probably exuviae as well. Fossils of the actual remains of eurypterids (i.e. their carcasses) are relatively rare. Fossil eurypterids are often deposited in characteristic windrows, probably a result of wave and wind action.

See also

* List of eurypteridsReferences

External links

Eurypterid.co.uk

maintained by James Lamsdell

Eurypterids.net

maintained by Samuel J. Ciurca, Jr.

Fossil biomechanics

{{Taxonbar, from=Q2143015 Eurypteroidea Silurian eurypterids Paleontology in New York (state) Symbols of New York (state) Eurypterids of North America Paleozoic life of New Brunswick Paleozoic life of Nunavut Paleozoic life of Quebec Eurypterids of Europe Bertie Formation Fossil taxa described in 1825