Erich Strunck on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Duquesne Spy Ring is the largest

Born in

Born in

Born in Germany, Paul Bante served in the German Army during the First World War. In 1930 he came to the United States, where he was naturalized in 1938. Bante, a former member of the

Born in Germany, Paul Bante served in the German Army during the First World War. In 1930 he came to the United States, where he was naturalized in 1938. Bante, a former member of the

Blank came to the United States from Germany in 1928. While he never became a U.S. citizen, he'd been employed at a German library. Blank boasted to agent Sebold that he had been in the espionage business since 1936, but lost interest in recent years since payments from Germany had fallen off.

Blank pleaded guilty to violating the Registration Act. He was sentenced 18 months in prison and fined $1,000.

Blank came to the United States from Germany in 1928. While he never became a U.S. citizen, he'd been employed at a German library. Blank boasted to agent Sebold that he had been in the espionage business since 1936, but lost interest in recent years since payments from Germany had fallen off.

Blank pleaded guilty to violating the Registration Act. He was sentenced 18 months in prison and fined $1,000.

In September 1934, German-born Heinrich Clausing came to the United States, where he became a naturalized citizen in 1938. Around 1938, Heine was recruited to find American automobile and aviation industry secrets that could be passed to Germany through the Duquesne Spy Ring. Later it was discovered that Heine was also the mysterious "Heinrich" who supplied the spy ring with aerial photographs.

After obtaining technical books relating to magnesium and aluminum alloys, Heine sent the materials to Heinrich Eilers. To ensure safe delivery of the books to Germany in case they did not reach Eilers, Heine indicated the return address on the package as the address of Lilly Stein.

Clausing pleaded guilty to espionage and was sentenced to 8 years in prison. He also received a two-year concurrent sentence and was fined $5,000 for violating of the Registration Act.

In September 1934, German-born Heinrich Clausing came to the United States, where he became a naturalized citizen in 1938. Around 1938, Heine was recruited to find American automobile and aviation industry secrets that could be passed to Germany through the Duquesne Spy Ring. Later it was discovered that Heine was also the mysterious "Heinrich" who supplied the spy ring with aerial photographs.

After obtaining technical books relating to magnesium and aluminum alloys, Heine sent the materials to Heinrich Eilers. To ensure safe delivery of the books to Germany in case they did not reach Eilers, Heine indicated the return address on the package as the address of Lilly Stein.

Clausing pleaded guilty to espionage and was sentenced to 8 years in prison. He also received a two-year concurrent sentence and was fined $5,000 for violating of the Registration Act.

In 1934, Fehse left Germany for the United States, where he was naturalized in 1938. Since emigrating, he'd been employed as a cook aboard ships sailing from the New York Harbor. Fehse was one of the leading forces in the spy ring. He arranged meetings, directed members’ activities, correlated information that had been developed, and arranged for its transmittal to Germany, chiefly through Sebold. Fehse, who was trained for espionage work in

In 1934, Fehse left Germany for the United States, where he was naturalized in 1938. Since emigrating, he'd been employed as a cook aboard ships sailing from the New York Harbor. Fehse was one of the leading forces in the spy ring. He arranged meetings, directed members’ activities, correlated information that had been developed, and arranged for its transmittal to Germany, chiefly through Sebold. Fehse, who was trained for espionage work in

Kärcher emigrated from Germany to the United States in 1923, and was naturalized in 1931. He served in the German Army during World War I, and was a former leader of the German American Bund in New York. During visits to Germany, Kärcher was seen wearing a German Army officer’s uniform. At the time of his arrest, he was engaged in designing power plants for a gas and electricity company in New York City. Kärcher was arrested with Paul Scholz, who'd just given Kärcher a table of call letters and frequencies for transmitting information to Germany by radio.

After pleading guilty to violating the Registration Act, Kärcher was sentenced to 22 months in prison and fined $2,000.

Kärcher emigrated from Germany to the United States in 1923, and was naturalized in 1931. He served in the German Army during World War I, and was a former leader of the German American Bund in New York. During visits to Germany, Kärcher was seen wearing a German Army officer’s uniform. At the time of his arrest, he was engaged in designing power plants for a gas and electricity company in New York City. Kärcher was arrested with Paul Scholz, who'd just given Kärcher a table of call letters and frequencies for transmitting information to Germany by radio.

After pleading guilty to violating the Registration Act, Kärcher was sentenced to 22 months in prison and fined $2,000.

Herman W. Lang had participated in the

Herman W. Lang had participated in the

A native of

A native of

Rene Emanuel Mezenen, a

Rene Emanuel Mezenen, a

Having come to the United States from Germany in 1929, Carl Reuper became a citizen in 1936. Prior to his arrest, he served as an inspector for the

Having come to the United States from Germany in 1929, Carl Reuper became a citizen in 1936. Prior to his arrest, he served as an inspector for the

Born in the

Born in the

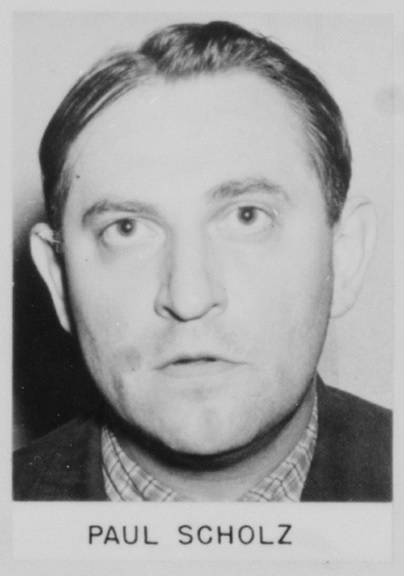

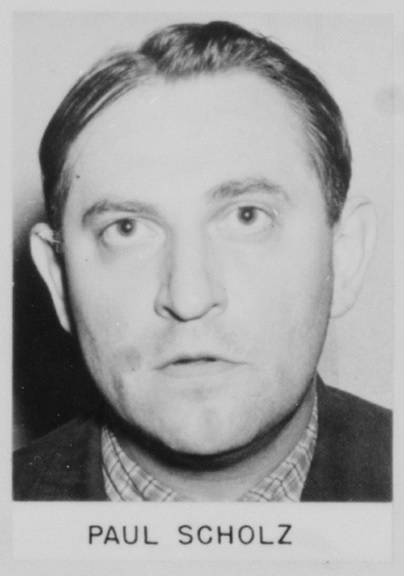

A German native, Paul Scholz went to the United States in 1926 but never attained citizenship. He had been employed in German book stores in New York City, where he disseminated Nazi propaganda.

Scholz had arranged for Josef Klein to construct the radio set used by Felix Jahnke and Axel Wheeler-Hill. At the time of his arrest, Scholz had just given Gustav Wilhelm Kaercher a list of radio call letters and frequencies. He also encouraged members of this spy ring to secure data for Germany and arranged contacts between various German agents.

After being convicted at trial, Scholz was sentenced to 16 years in prison for espionage and received a concurrent two-year sentence under the Registration Act.

A German native, Paul Scholz went to the United States in 1926 but never attained citizenship. He had been employed in German book stores in New York City, where he disseminated Nazi propaganda.

Scholz had arranged for Josef Klein to construct the radio set used by Felix Jahnke and Axel Wheeler-Hill. At the time of his arrest, Scholz had just given Gustav Wilhelm Kaercher a list of radio call letters and frequencies. He also encouraged members of this spy ring to secure data for Germany and arranged contacts between various German agents.

After being convicted at trial, Scholz was sentenced to 16 years in prison for espionage and received a concurrent two-year sentence under the Registration Act.

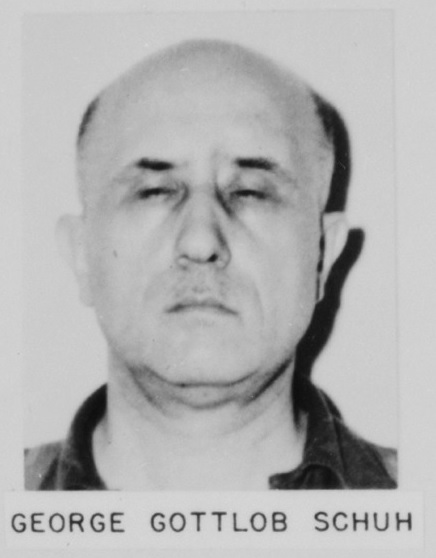

George Gottlob Schuh, a native of Germany, went to the United States in 1923. He became a citizen in 1939 and was employed as a

George Gottlob Schuh, a native of Germany, went to the United States in 1923. He became a citizen in 1939 and was employed as a

Erwin Wilhelm Siegler went to the United States from Germany in 1929 and attained citizenship in 1936. He had served as chief butcher on the until it was taken over by the U.S. Navy.

A courier, Siegler brought microphotographic instructions to Sebold from German authorities on one occasion. He also had brought $2,900 from German contacts abroad to pay Lilly Stein, Duquesne, and Roeder for their services and to buy a bomb sight. He served the espionage group as an organizer and contact man, and he also obtained information about the movement of ships and military defense preparations at the

Erwin Wilhelm Siegler went to the United States from Germany in 1929 and attained citizenship in 1936. He had served as chief butcher on the until it was taken over by the U.S. Navy.

A courier, Siegler brought microphotographic instructions to Sebold from German authorities on one occasion. He also had brought $2,900 from German contacts abroad to pay Lilly Stein, Duquesne, and Roeder for their services and to buy a bomb sight. He served the espionage group as an organizer and contact man, and he also obtained information about the movement of ships and military defense preparations at the

Born in Germany, Oscar Richard Stabler went to the United States in 1923 and became a citizen in 1933. He had been employed primarily as a

Born in Germany, Oscar Richard Stabler went to the United States in 1923 and became a citizen in 1933. He had been employed primarily as a

Heinrich Stade went to the United States from Germany in 1922 and became a citizen in 1929. He had been a musician and publicity agent in New York. He told agent Sebold he had been in the Gestapo since 1936 and boasted that he knew everything in the spy business.

Stade had arranged for Paul Bante's contact with Sebold and had transmitted data to Germany regarding points of rendezvous for

Heinrich Stade went to the United States from Germany in 1922 and became a citizen in 1929. He had been a musician and publicity agent in New York. He told agent Sebold he had been in the Gestapo since 1936 and boasted that he knew everything in the spy business.

Stade had arranged for Paul Bante's contact with Sebold and had transmitted data to Germany regarding points of rendezvous for

Born in

Born in

In 1931, Franz Joseph Stigler, left Germany for the United States, where he became a citizen in 1939. He had been employed as a crew member and chief baker aboard U.S. ships until his discharge from the when the U.S. Navy converted that ship into . His constant companion was Erwin Siegler, and they operated as couriers in transmitting information between the United States and German agents aboard. Stigler sought to recruit amateur radio operators in the United States as channels of communication to German radio stations. He had also observed and reported defense preparations in the

In 1931, Franz Joseph Stigler, left Germany for the United States, where he became a citizen in 1939. He had been employed as a crew member and chief baker aboard U.S. ships until his discharge from the when the U.S. Navy converted that ship into . His constant companion was Erwin Siegler, and they operated as couriers in transmitting information between the United States and German agents aboard. Stigler sought to recruit amateur radio operators in the United States as channels of communication to German radio stations. He had also observed and reported defense preparations in the

A seaman aboard the ships of the

A seaman aboard the ships of the

Leo Waalen was born in Danzig, Germany. He entered the United States by "jumping ship" about 1935. He was a painter for a small boat company which was constructing small craft for the U.S. Navy.

Waalen gathered information about ships sailing for England. He also obtained a confidential booklet issued by the FBI which contained precautions to be taken by industrial plants to safeguard national defense materials from sabotage. He secured government contracts listing specifications for materials and equipment, as well as detailed sea charts of the United States Atlantic coastline.

In May 1941, the American cargo vessel was carrying nine officers, 29 crewmen, seven or eight passengers, and a commercial cargo from New York to

Leo Waalen was born in Danzig, Germany. He entered the United States by "jumping ship" about 1935. He was a painter for a small boat company which was constructing small craft for the U.S. Navy.

Waalen gathered information about ships sailing for England. He also obtained a confidential booklet issued by the FBI which contained precautions to be taken by industrial plants to safeguard national defense materials from sabotage. He secured government contracts listing specifications for materials and equipment, as well as detailed sea charts of the United States Atlantic coastline.

In May 1941, the American cargo vessel was carrying nine officers, 29 crewmen, seven or eight passengers, and a commercial cargo from New York to

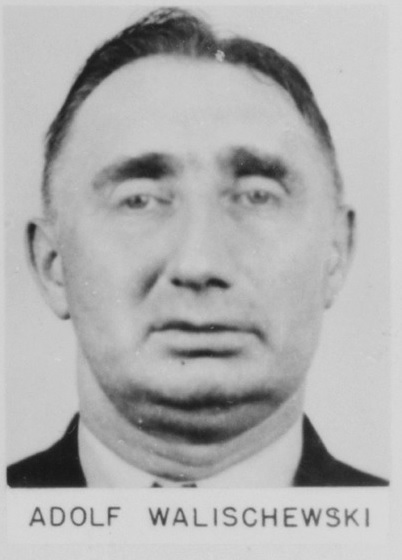

A German native, Walischewski had been a seaman since maturity. He became a naturalized citizen in 1935. Walischewski became connected with the German espionage system through Paul Fehse. His duties were confined to those of courier, carrying data from agents in the United States to contacts abroad.

Upon conviction, Walischewski received a five-year prison sentence on espionage charges, as well as a two-year concurrent sentence under the Registration Act.

A German native, Walischewski had been a seaman since maturity. He became a naturalized citizen in 1935. Walischewski became connected with the German espionage system through Paul Fehse. His duties were confined to those of courier, carrying data from agents in the United States to contacts abroad.

Upon conviction, Walischewski received a five-year prison sentence on espionage charges, as well as a two-year concurrent sentence under the Registration Act.

Else Weustenfeld arrived in the United States from Germany in 1927 and became a citizen 10 years later. From 1935 until her arrest, she was a secretary for a law firm representing the German Consulate in New York City.

Weustenfeld was thoroughly acquainted with the German espionage system and delivered funds to Duquesne which she had received from Lilly Stein, her close friend.

She lived in New York City with Hans W. Ritter, a principal in the German espionage system. His brother, Nickolaus Ritter, was the "Dr. Renken" who had enlisted Sebold as a German agent. In 1940, Weustenfeld visited Hans Ritter in Mexico, where he was serving as a paymaster for the German Intelligence Service.

After pleading guilty, Else Weustenfeld was sentenced to five years' imprisonment on charge of espionage and two concurrent years on a charge of registration violations.

Else Weustenfeld arrived in the United States from Germany in 1927 and became a citizen 10 years later. From 1935 until her arrest, she was a secretary for a law firm representing the German Consulate in New York City.

Weustenfeld was thoroughly acquainted with the German espionage system and delivered funds to Duquesne which she had received from Lilly Stein, her close friend.

She lived in New York City with Hans W. Ritter, a principal in the German espionage system. His brother, Nickolaus Ritter, was the "Dr. Renken" who had enlisted Sebold as a German agent. In 1940, Weustenfeld visited Hans Ritter in Mexico, where he was serving as a paymaster for the German Intelligence Service.

After pleading guilty, Else Weustenfeld was sentenced to five years' imprisonment on charge of espionage and two concurrent years on a charge of registration violations.

Axel Wheeler-Hill went to the United States in 1923 from his native

Axel Wheeler-Hill went to the United States in 1923 from his native

Born in Germany, Bertram Wolfgang Zenzinger went to the United States in 1940 as a naturalized citizen of the

Born in Germany, Bertram Wolfgang Zenzinger went to the United States in 1940 as a naturalized citizen of the

Lieutenant Commander Takeo Ezima of the Imperial Japanese Navy operated in New York as an engineer inspector using the name: E. Satoz; code name: KATO.

He arrived on the ''Heian Maru'' in Seattle in 1938. On October 19, 1940, Sebold received a radio message from Germany that CARR (Abwehr Agent Roeder) was to meet E. Satoz at a Japanese club in New York.

Ezima was filmed by the FBI while meeting with agent Sebold in New York, conclusive evidence of German-Japanese cooperation in espionage, in addition to meeting with Kanegoro Koike, Paymaster Commander of the

Lieutenant Commander Takeo Ezima of the Imperial Japanese Navy operated in New York as an engineer inspector using the name: E. Satoz; code name: KATO.

He arrived on the ''Heian Maru'' in Seattle in 1938. On October 19, 1940, Sebold received a radio message from Germany that CARR (Abwehr Agent Roeder) was to meet E. Satoz at a Japanese club in New York.

Ezima was filmed by the FBI while meeting with agent Sebold in New York, conclusive evidence of German-Japanese cooperation in espionage, in addition to meeting with Kanegoro Koike, Paymaster Commander of the

(Lieutenant colonel)

(Lieutenant colonel)

Federal Bureau of Investigation Vault: Frederick Duquesne Case Write-up

FBI Famous Cases & Criminals: The Duquesne Spy Ring

espionage

Espionage, spying, or intelligence gathering, as a subfield of the intelligence field, is the act of obtaining secret or confidential information ( intelligence). A person who commits espionage on a mission-specific contract is called an ...

case in the United States history that ended in convictions. A total of 33 members of a Nazi German

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a totalitarian dictat ...

espionage network, headed by Frederick "Fritz" Duquesne, were convicted after a lengthy investigation by the Federal Bureau of Investigation

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic Intelligence agency, intelligence and Security agency, security service of the United States and Federal law enforcement in the United States, its principal federal law enforcement ag ...

(FBI). Of those indicted, 19 pleaded guilty. The remaining 14 were brought to jury trial in Federal District Court

The United States district courts are the trial courts of the U.S. federal judiciary. There is one district court for each federal judicial district. Each district covers one U.S. state or a portion of a state. There is at least one feder ...

, Brooklyn, New York

Brooklyn is a Boroughs of New York City, borough of New York City located at the westernmost end of Long Island in the New York (state), State of New York. Formerly an independent city, the borough is coextensive with Kings County, one of twelv ...

, on September 3, 1941; all were found guilty on December 13, 1941. On January 2, 1942, the group members were sentenced to serve a total of over 300 years in prison.

The agents who formed the Duquesne Ring were placed in key jobs in the United States to get information that could be used in the event of war and to carry out acts of sabotage

Sabotage is a deliberate action aimed at weakening a polity, government, effort, or organization through subversion, obstruction, demoralization (warfare), demoralization, destabilization, divide and rule, division, social disruption, disrupti ...

: one opened a restaurant and used his position to get information from his customers; another worked on an airline so that he could report Allied

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not an explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are calle ...

ships that were crossing the Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of the world's five borders of the oceans, oceanic divisions, with an area of about . It covers approximately 17% of Earth#Surface, Earth's surface and about 24% of its water surface area. During the ...

; others worked as delivery people as a cover for carrying secret messages.

William G. Sebold, who had been blackmailed into becoming a spy for Germany, became a double agent

In the field of counterintelligence, a double agent is an employee of a secret intelligence service for one country, whose primary purpose is to spy on a target organization of another country, but who is now spying on their own country's organi ...

and helped the FBI gather evidence. For nearly two years, the FBI ran a shortwave radio

Shortwave radio is radio transmission using radio frequencies in the shortwave bands (SW). There is no official definition of the band range, but it always includes all of the High frequency, high frequency band (HF), which extends from 3 to 30& ...

station in New York for the ring. They learned what information Germany was sending its spies in the United States and controlled what was sent to Germany. Sebold's success as a counterespionage

Counterintelligence (counter-intelligence) or counterespionage (counter-espionage) is any activity aimed at protecting an agency's intelligence program from an opposition's intelligence service. It includes gathering information and conducting ac ...

agent was demonstrated by the successful prosecution of the German agents.

One German spymaster later commented the ring's roundup delivered "the death blow" to their espionage efforts in the United States. FBI director J. Edgar Hoover

John Edgar Hoover (January 1, 1895 – May 2, 1972) was an American attorney and law enforcement administrator who served as the fifth and final director of the Bureau of Investigation (BOI) and the first director of the Federal Bureau o ...

called his concerted FBI swoop on Duquesne's ring the greatest spy roundup in U.S. history.

The 1945 film ''The House on 92nd Street

''The House on 92nd Street'' is a 1945 black-and-white American spy film directed by Henry Hathaway. The movie, shot mostly in New York City, was released shortly after the end of World War II. ''The House on 92nd Street'' was made with the full ...

'' was a thinly disguised version of the ''Duquesne Spy Ring'' saga of 1941.

FBI agents

William Sebold (double-agent)

After the Duquesne Spy Ring convictions, Sebold was provided with a new identity and started a chicken farm inCalifornia

California () is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States that lies on the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. It borders Oregon to the north, Nevada and Arizona to the east, and shares Mexico–United States border, an ...

.

Impoverished and delusional, he was committed to Napa State Hospital

Napa State Hospital is a psychiatric hospital in Napa, California, founded in 1875. It is located along California State Route 221, the Napa-Vallejo Highway, and is one of California's five state mental hospitals. Napa State Hospital holds civil ...

in 1965. Diagnosed with manic-depression, he died there of a heart attack five years later at 70. His life story as a double agent was first told in the 1943 book ''Passport to Treason: The Inside Story of Spies in America'' by Alan Hynd

Alan may refer to:

People

*Alan (surname), an English and Kurdish surname

*Alan (given name), an English given name

**List of people with given name Alan

''Following are people commonly referred to solely by "Alan" or by a homonymous name.''

*Al ...

.

James Ellsworth

Special Agent

In the United States, a special agent is an official title used to refer to certain investigators or detectives of federal, military, tribal, or state agencies who primarily serve in criminal investigatory positions. Additionally, some special ...

Jim Ellsworth was assigned as Sebold's handler or body man, responsible for shadowing his every move during the 16-month investigation.

William Gustav Friedemann

William Gustav Friedemann was a principal witness in the Duquesne case. He began working for the FBI as afingerprint

A fingerprint is an impression left by the friction ridges of a human finger. The recovery of partial fingerprints from a crime scene is an important method of forensic science. Moisture and grease on a finger result in fingerprints on surfa ...

analyst in 1935 and later became an agent after identifying a crucial fingerprint in a kidnapping case.

After World War II, he was assigned to Puerto Rico

; abbreviated PR), officially the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, is a Government of Puerto Rico, self-governing Caribbean Geography of Puerto Rico, archipelago and island organized as an Territories of the United States, unincorporated territo ...

, where he pinpointed the group behind the assassination attempt on President Harry Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. As the 34th vice president in 1945, he assumed the presidency upon the death of Franklin D. Roosevelt that year. Subsequen ...

. Friedemann died of cancer on August 23, 1989, in Stillwater, Oklahoma

Stillwater is the tenth-largest city in the U.S. state of Oklahoma, and the county seat of Payne County, Oklahoma, Payne County. It is located in north-central Oklahoma at the intersection of U.S. Route 177#Oklahoma, U.S. Route 177 and Oklahoma S ...

.

Convicted members of Duquesne Spy Ring

Fritz Duquesne

Born in

Born in Cape Colony

The Cape Colony (), also known as the Cape of Good Hope, was a British Empire, British colony in present-day South Africa named after the Cape of Good Hope. It existed from 1795 to 1802, and again from 1806 to 1910, when it united with three ...

, South Africa, on September 21, 1877, and a naturalized citizen of the United States in 1913, Fritz Joubert Duquesne was a captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader or highest rank officer of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police depa ...

in the Second Boer War

The Second Boer War (, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, Transvaal War, Anglo–Boer War, or South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer republics (the South African Republic and ...

and later a colonel

Colonel ( ; abbreviated as Col., Col, or COL) is a senior military Officer (armed forces), officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, a colon ...

in the ''Abwehr

The (German language, German for ''resistance'' or ''defence'', though the word usually means ''counterintelligence'' in a military context) ) was the German military intelligence , military-intelligence service for the ''Reichswehr'' and the ...

'', Germany's division of military intelligence.

Duquesne was captured and imprisoned three times by the British, once by the Portuguese, and once by the Americans in 1917, and each time he escaped. In World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, he was a spy and ring leader for Germany and during this time he sabotaged British merchant ships in South America with concealed bombs and destroyed several. Duquesne was also ordered to assassinate an American, Frederick Russell Burnham

Major (rank), Major Frederick Russell Burnham Distinguished Service Order, DSO (May 11, 1861 – September 1, 1947) was an American scout and world-traveling adventurer. He is known for his service to the British South Africa Company and to t ...

, Chief of Scouts for the British Army, but failed to do so. He was known as "The man who killed Kitchener" since he claimed to have sabotaged and sunk HMS ''Hampshire'', on which Lord Kitchener was en route to Russia in 1916.

In the spring of 1934, Duquesne became an intelligence officer for the Order of 76, an American pro-Nazi organization, and in January 1935 he began working for U.S. government's Works Progress Administration

The Works Progress Administration (WPA; from 1935 to 1939, then known as the Work Projects Administration from 1939 to 1943) was an American New Deal agency that employed millions of jobseekers (mostly men who were not formally educated) to car ...

. Admiral Wilhelm Canaris

Wilhelm Franz Canaris (1 January 1887 – 9 April 1945) was a admiral (Germany), German admiral and the chief of the ''Abwehr'' (the German military intelligence, military-intelligence service) from 1935 to 1944. Initially a supporter of Ad ...

, head of the ''Abwehr'', knew Duquesne from his work in World War I and he instructed his new chief of operations in the U.S., Col. Nikolaus Ritter

Nikolaus Ritter (8 January 1899 – 9 April 1974) is best known as the Chief of Air Intelligence in the Abwehr (German military intelligence) who led spyrings in the United Kingdom and the United States from 1936 to 1941.

Early life

Ritter wa ...

, to make contact. Ritter had been friends with Duquesne back in 1931 and the two spies reconnected in New York on December 3, 1937.

On February 8, 1940, Ritter sent Sebold, under the alias of Harry Sawyer, to New York and instructed him to set up a shortwave radio-transmitting station and to contact Duquesne, code-named DUNN.

Once the FBI discovered through Sebold that Duquesne was again in New York operating as a German spy, director J. Edgar Hoover

John Edgar Hoover (January 1, 1895 – May 2, 1972) was an American attorney and law enforcement administrator who served as the fifth and final director of the Bureau of Investigation (BOI) and the first director of the Federal Bureau o ...

provided a background briefing to President Franklin Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), also known as FDR, was the 32nd president of the United States, serving from 1933 until his death in 1945. He is the longest-serving U.S. president, and the only one to have served ...

. FBI agent Raymond Newkirk, using the name Ray McManus, was now assigned to DUNN and he rented a room immediately above Duquesne's apartment near Central Park

Central Park is an urban park between the Upper West Side and Upper East Side neighborhoods of Manhattan in New York City, and the first landscaped park in the United States. It is the List of parks in New York City, sixth-largest park in the ...

and used a hidden microphone to record Duquesne's conversations. But monitoring Duquesne's activities proved to be difficult. As Newkirk described it, "The Duke had been a spy all of his life and automatically used all of the tricks in the book to avoid anyone following him...He would take a local train, change to an express, change back to a local, go through a revolving door and keep going on right around, take an elevator up a floor, get off, walk back to the ground, and take off in a different entrance of the building." Duquesne also informed Sebold that he was certain he was under surveillance, and he even confronted one FBI agent and demanded that he stop tracking him, a story confirmed by agent Newkirk.

In a letter to the Chemical Warfare Service

The Chemical Corps is the branch of the United States Army tasked with defending against and using chemical weapon, chemical, biological agent, biological, radiological weapon, radiological, and nuclear weapon, nuclear (Chemical, biological, r ...

in Washington, D.C., Duquesne requested information on a new gas mask

A gas mask is a piece of personal protective equipment used to protect the wearer from inhaling airborne pollutants and toxic gases. The mask forms a sealed cover over the nose and mouth, but may also cover the eyes and other vulnerable soft ...

. He identified himself as a "well-known, responsible and reputable writer and lecturer." At the bottom of the letter, he wrote, "Don't be concerned if this information is confidential, because it will be in the hands of a good, patriotic citizen." A short time later, the information he requested arrived in the mail and a week later it was being read by intelligence officers in Berlin.

Duquesne was found guilty of espionage and sentenced to 18 years in prison. He received a concurrent two-year sentence and was fined $2,000 for violating the Foreign Agents Registration Act

The Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA) ( ''et seq.'') is a United States law that imposes Public disclosure of private facts, public disclosure obligations on Foreign agent, persons representing foreign interests.

. Duquesne served his sentence in Leavenworth Federal Penitentiary

The Federal Correctional Institution, Leavenworth is a medium-security federal prison for male inmates in northeast Kansas. It is operated by the Federal Bureau of Prisons, a division of the United States Department of Justice. It also includes ...

in Kansas

Kansas ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders Nebraska to the north; Missouri to the east; Oklahoma to the south; and Colorado to the west. Kansas is named a ...

, where he was mistreated and beaten by other inmates. In 1954, he was released due to ill health, having served fourteen years, and died indigent, at City Hospital on Welfare Island

Roosevelt Island is an island in New York City's East River, within the borough of Manhattan. It lies between Manhattan Island to the west, and the borough of Queens, on Long Island, to the east. It is about long, with an area of , and had a ...

(now Roosevelt Island

Roosevelt Island is an island in New York City's East River, within the Borough (New York City), borough of Manhattan. It lies between Manhattan Island to the west, and the borough of Queens, on Long Island, to the east. It is about long, wit ...

), New York City, on May 24, 1956, at the age of 78.

Paul Bante

Born in Germany, Paul Bante served in the German Army during the First World War. In 1930 he came to the United States, where he was naturalized in 1938. Bante, a former member of the

Born in Germany, Paul Bante served in the German Army during the First World War. In 1930 he came to the United States, where he was naturalized in 1938. Bante, a former member of the German American Bund

The German American Bund, or the German American Federation (, ''Amerikadeutscher Volksbund'', AV), was a German-American Nazi organization which was established in 1936 as a successor to the Friends of New Germany (FONG, FDND in German) and ...

, claimed that he was brought into contact with agent Paul Fehse because of his ties to Ignatz Theodor Griebl. Before he fled the United States for Germany, Griebl was accused of belonging to a Nazi spy ring along with Rumrich spy ring. Bante helped Fehse to obtain information about ships leaving for Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-west coast of continental Europe, consisting of the countries England, Scotland, and Wales. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the List of European ...

loaded with war supplies. As a Gestapo

The (, ), Syllabic abbreviation, abbreviated Gestapo (), was the official secret police of Nazi Germany and in German-occupied Europe.

The force was created by Hermann Göring in 1933 by combining the various political police agencies of F ...

agent, he was supposed to cause discontent amongst trade unionists. Sebold met Bante at the ''Little Casino Restaurant'', which was frequently used by the ring's members. During one of these meetings, Bante talked about making a bomb detonator, after which he later gave dynamite and detonators to Sebold.

Bante pleaded guilty to violating the Registration Act. He was sentenced to 18 months in prison and fined $1,000.

Max Blank

Blank came to the United States from Germany in 1928. While he never became a U.S. citizen, he'd been employed at a German library. Blank boasted to agent Sebold that he had been in the espionage business since 1936, but lost interest in recent years since payments from Germany had fallen off.

Blank pleaded guilty to violating the Registration Act. He was sentenced 18 months in prison and fined $1,000.

Blank came to the United States from Germany in 1928. While he never became a U.S. citizen, he'd been employed at a German library. Blank boasted to agent Sebold that he had been in the espionage business since 1936, but lost interest in recent years since payments from Germany had fallen off.

Blank pleaded guilty to violating the Registration Act. He was sentenced 18 months in prison and fined $1,000.

Heinrich Clausing

In September 1934, German-born Heinrich Clausing came to the United States, where he became a naturalized citizen in 1938. Around 1938, Heine was recruited to find American automobile and aviation industry secrets that could be passed to Germany through the Duquesne Spy Ring. Later it was discovered that Heine was also the mysterious "Heinrich" who supplied the spy ring with aerial photographs.

After obtaining technical books relating to magnesium and aluminum alloys, Heine sent the materials to Heinrich Eilers. To ensure safe delivery of the books to Germany in case they did not reach Eilers, Heine indicated the return address on the package as the address of Lilly Stein.

Clausing pleaded guilty to espionage and was sentenced to 8 years in prison. He also received a two-year concurrent sentence and was fined $5,000 for violating of the Registration Act.

In September 1934, German-born Heinrich Clausing came to the United States, where he became a naturalized citizen in 1938. Around 1938, Heine was recruited to find American automobile and aviation industry secrets that could be passed to Germany through the Duquesne Spy Ring. Later it was discovered that Heine was also the mysterious "Heinrich" who supplied the spy ring with aerial photographs.

After obtaining technical books relating to magnesium and aluminum alloys, Heine sent the materials to Heinrich Eilers. To ensure safe delivery of the books to Germany in case they did not reach Eilers, Heine indicated the return address on the package as the address of Lilly Stein.

Clausing pleaded guilty to espionage and was sentenced to 8 years in prison. He also received a two-year concurrent sentence and was fined $5,000 for violating of the Registration Act.

Paul Fehse

In 1934, Fehse left Germany for the United States, where he was naturalized in 1938. Since emigrating, he'd been employed as a cook aboard ships sailing from the New York Harbor. Fehse was one of the leading forces in the spy ring. He arranged meetings, directed members’ activities, correlated information that had been developed, and arranged for its transmittal to Germany, chiefly through Sebold. Fehse, who was trained for espionage work in

In 1934, Fehse left Germany for the United States, where he was naturalized in 1938. Since emigrating, he'd been employed as a cook aboard ships sailing from the New York Harbor. Fehse was one of the leading forces in the spy ring. He arranged meetings, directed members’ activities, correlated information that had been developed, and arranged for its transmittal to Germany, chiefly through Sebold. Fehse, who was trained for espionage work in Hamburg

Hamburg (, ; ), officially the Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg,. is the List of cities in Germany by population, second-largest city in Germany after Berlin and List of cities in the European Union by population within city limits, 7th-lar ...

, claimed he headed the Marine Division of the Nazi espionage system in the United States.

Having become nervous, Fehse made plans to leave the country. He obtained a position on the SS ''Siboney'', which was scheduled to sail from Hoboken, New Jersey

Hoboken ( ; ) is a City (New Jersey), city in Hudson County, New Jersey, Hudson County in the U.S. state of New Jersey. Hoboken is part of the New York metropolitan area and is the site of Hoboken Terminal, a major transportation hub. As of the ...

, for Lisbon

Lisbon ( ; ) is the capital and largest city of Portugal, with an estimated population of 567,131, as of 2023, within its administrative limits and 3,028,000 within the Lisbon Metropolitan Area, metropolis, as of 2025. Lisbon is mainlan ...

, on March 29, 1941. He planned to desert ship in Lisbon and return to Germany. However, before he could leave, Fehse was arrested by the FBI. Upon his arrest, he admitted sending letters to Italy for transmittal to Germany, as well as reporting the movements of British ships. Fehse pleaded guilty to violating the Registration Act and was sentenced to one year and one day in prison. He later pleaded guilty to espionage and was sentenced to 15 years in prison.

Gustav Wilhelm Kärcher

Kärcher emigrated from Germany to the United States in 1923, and was naturalized in 1931. He served in the German Army during World War I, and was a former leader of the German American Bund in New York. During visits to Germany, Kärcher was seen wearing a German Army officer’s uniform. At the time of his arrest, he was engaged in designing power plants for a gas and electricity company in New York City. Kärcher was arrested with Paul Scholz, who'd just given Kärcher a table of call letters and frequencies for transmitting information to Germany by radio.

After pleading guilty to violating the Registration Act, Kärcher was sentenced to 22 months in prison and fined $2,000.

Kärcher emigrated from Germany to the United States in 1923, and was naturalized in 1931. He served in the German Army during World War I, and was a former leader of the German American Bund in New York. During visits to Germany, Kärcher was seen wearing a German Army officer’s uniform. At the time of his arrest, he was engaged in designing power plants for a gas and electricity company in New York City. Kärcher was arrested with Paul Scholz, who'd just given Kärcher a table of call letters and frequencies for transmitting information to Germany by radio.

After pleading guilty to violating the Registration Act, Kärcher was sentenced to 22 months in prison and fined $2,000.

Herman W. Lang

Herman W. Lang had participated in the

Herman W. Lang had participated in the Beer Hall Putsch

The Beer Hall Putsch, also known as the Munich Putsch,Dan Moorhouse, ed schoolshistory.org.uk, accessed 2008-05-31.Known in German as the or was a failed coup d'état by Nazi Party leader Adolf Hitler, Erich Ludendorff and other leaders i ...

in 1923. He immigrated to the United States in 1927.

Until his arrest, machinist and draftsman Lang had been employed as an assembly inspector by the Carl L. Norden Corp., which manufactured the top secret

Classified information is confidential material that a government deems to be sensitive information which must be protected from unauthorized disclosure that requires special handling and dissemination controls. Access is restricted by law or ...

Norden bombsight

The Norden Mk. XV, known as the Norden M series in U.S. Army service, is a bombsight that was used by the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) and the United States Navy during World War II, and the United States Air Force in the Korean War, ...

. In October 1937 he met Ritter and told him he had overnight access to classified drawings and used it to copy them in his kitchen at home while his family was asleep. He then hid the plans in a wooden casing for an umbrella, and, on January 9, 1938, personally handed the umbrella off to a German steward and secret courier on the ship bound for Bremen

Bremen (Low German also: ''Breem'' or ''Bräm''), officially the City Municipality of Bremen (, ), is the capital of the States of Germany, German state of the Bremen (state), Free Hanseatic City of Bremen (), a two-city-state consisting of the c ...

. For that he received $1500. However, he could not copy all the plans, and Ritter had to invite him to Germany in order to complete a model, where he was received by Hermann Göring

Hermann Wilhelm Göring (or Goering; ; 12 January 1893 – 15 October 1946) was a German Nazism, Nazi politician, aviator, military leader, and convicted war criminal. He was one of the most powerful figures in the Nazi Party, which gov ...

himself.

The Norden bombsight had been considered a critical wartime instrument by the United States Army Air Forces

The United States Army Air Forces (USAAF or AAF) was the major land-based aerial warfare service component of the United States Army and ''de facto'' aerial warfare service branch of the United States during and immediately after World War II ...

, and American bombardiers were required to take an oath during their training stating that they would defend its secret with their own life, if needed.Ross: ''Strategic Bombing by the United States in World War II'' The Lotfernrohr 3 and the BZG 2 in 1942 used a similar set of gyroscopes

A gyroscope (from Ancient Greek γῦρος ''gŷros'', "round" and σκοπέω ''skopéō'', "to look") is a device used for measuring or maintaining Orientation (geometry), orientation and angular velocity. It is a spinning wheel or disc in ...

that provided a stabilized platform for the bombardier to sight through, although the more complex interaction between the bombsight and autopilot was not used. Later in the war, Luftwaffe bombers used the Carl Zeiss

Carl Zeiss (; 11 September 1816 – 3 December 1888) was a German scientific instrument maker, optician and businessman. In 1846 he founded his workshop, which is still in business as Zeiss (company), Zeiss. Zeiss gathered a group of gifted p ...

Lotfernrohr 7

The Carl Zeiss ''Lotfernrohr'' 7 (''Lot'' meant "Vertical" and ''Fernrohr'' meant "Telescope"), or ''Lotfe'' 7, was the primary series of bombsights used in most Luftwaffe level bombers, similar to the United States' Norden bombsight, but much simp ...

, or Lotfe 7, which had an advanced mechanical system similar to the Norden bombsight, but was much simpler to operate and maintain. At one point, Sebold was ordered to contact Lang as it became known that the technology he had stolen from Norden was being used in German bombers. The Nazis offered to spirit him to safety in Germany, but Lang refused to leave his home in Ridgewood, Queens

Ridgewood is a neighborhood in the New York City borough of Queens. It borders the Queens neighborhoods of Maspeth to the north, Middle Village to the east, and Glendale to the southeast, as well as the Brooklyn neighborhoods of Bushwick to ...

.

Upon conviction, Lang was sentenced to 18 years in prison on espionage charges and a concurrent two-year term under the Registration Act. He was released and deported to Germany in September 1950.

Evelyn Clayton Lewis

A native of

A native of Arkansas

Arkansas ( ) is a landlocked state in the West South Central region of the Southern United States. It borders Missouri to the north, Tennessee and Mississippi to the east, Louisiana to the south, Texas to the southwest, and Oklahoma ...

, Evelyn Clayton Lewis had been living with Duquesne in New York City. Lewis had expressed her anti-British and antisemitic

Antisemitism or Jew-hatred is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who harbours it is called an antisemite. Whether antisemitism is considered a form of racism depends on the school of thought. Antisemi ...

feelings during her relationship with Duquesne. She was aware of his espionage activities and condoned them. While she was not active in obtaining information for Germany, she helped Duquesne prepare material for transmittal abroad. After pleading guilty, Lewis was sentenced to serve one year and one day in prison for violating the Registration Act.

Rene Emanuel Mezenen

Rene Emanuel Mezenen, a

Rene Emanuel Mezenen, a Frenchman

French people () are a nation primarily located in Western Europe that share a common French culture, history, and language, identified with the country of France.

The French people, especially the native speakers of langues d'oïl from nort ...

, claimed U.S. citizenship through the naturalization of his father. Prior to his arrest, he was employed as a steward in the Pan American transatlantic clipper service.

The German Intelligence Service

The Federal Intelligence Service (, ; BND) is the foreign intelligence agency of Germany, directly subordinate to the Chancellor's Office. The BND headquarters is located in central Berlin. The BND has 300 locations in Germany and foreign cou ...

in Lisbon, Portugal, asked Mezenen to act as a courier, transmitting information between the United States and Portugal on his regular commercial aircraft trips. As a steward he was able to deliver documents from New York to Lisbon in 24 hours. He accepted this offer for financial gain. In the course of flights across the Atlantic, Mezenen reported his observance of convoys sailing for England. He also became involved in smuggling platinum

Platinum is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol Pt and atomic number 78. It is a density, dense, malleable, ductility, ductile, highly unreactive, precious metal, precious, silverish-white transition metal. Its name origina ...

from the United States to Portugal. When discussing his courier role with agent Sebold, Mezenen boasted that he hid the spy letters so well that if they were found it would have taken two to three weeks to repair the airplane.

After pleading guilty, Mezenen was sentenced to 8 years in prison for espionage. He received a concurrent two-year sentence for violating the Registration Act.

Carl Reuper

Having come to the United States from Germany in 1929, Carl Reuper became a citizen in 1936. Prior to his arrest, he served as an inspector for the

Having come to the United States from Germany in 1929, Carl Reuper became a citizen in 1936. Prior to his arrest, he served as an inspector for the Westinghouse Electric Company

Westinghouse Electric Company LLC is an American nuclear power company formed in 1999 from the nuclear power division of the original Westinghouse Electric Corporation. It offers nuclear products and services to utilities internationally, includ ...

in Newark, New Jersey

Newark ( , ) is the List of municipalities in New Jersey, most populous City (New Jersey), city in the U.S. state of New Jersey, the county seat of Essex County, New Jersey, Essex County, and a principal city of the New York metropolitan area. ...

. Previously, he worked as a mechanic for the Air Associates Company in Bendix, New Jersey.

Reuper obtained photographs for Germany relating to national defense materials and construction, which he obtained from his employment. He arranged radio contact with Germany through the station established by Felix Jahnke. On one occasion, he conferred with Sebold regarding the latter's facilities for communicating with German authorities. After being convicted at trial, Reuper was sentenced to 16 years in prison on espionage charges and received a concurrent two-year sentence under the Registration Act.

Everett Minster Roeder

Born in the

Born in the Bronx, New York

The Bronx ( ) is the northernmost of the five Boroughs of New York City, boroughs of New York City, coextensive with Bronx County, in the U.S. state of New York (state), New York. It shares a land border with Westchester County, New York, West ...

, Everett Minster Roeder was the son of a celebrated piano instructor, Carl Roeder. A child prodigy, when he was 15 years old he enrolled in engineering at Cornell University and there he met the brothers Edward and Elmer Sperry; however he dropped out of school when he was 18 and married his pregnant girlfriend. He was one of the first employees at the Sperry Gyroscope Company

Sperry Corporation was a major American equipment and electronics company whose existence spanned more than seven decades of the 20th century. Sperry ceased to exist in 1986 following a prolonged hostile takeover bid engineered by Burroughs ...

where he worked as an engineer and designer of confidential materials for the U.S. Army and Navy. In his job as a gyroscope expert working on U.S. military contracts, Roeder built machines such as tracking devices for long-range guns capable of hitting moving targets away, aircraft autopilot and blind-flying systems, ship stabilizers, and anti-aircraft search lights.

Sebold had delivered microphotograph

Microphotographs are photographs shrunk to microscopic scale.

instructions to Roeder, as ordered by German authorities. Roeder and Sebold met in public places and proceeded to spots where they could talk privately. In 1936, Roeder had visited Germany and was requested by German authorities to act as an espionage agent. Primarily due to monetary rewards he would receive, Roeder agreed.

Among the Sperry development secrets Roeder disclosed were the blueprints of the complete radio instrumentation of the new Glenn Martin bomber, classified drawings of range finders, blind-flying instruments, a bank-and-turn indicator, a navigator compass, a wiring diagram of the Lockheed Hudson bomber, and diagrams of the Hudson gun mountings. From Roeder the ''Abwehr'' also obtained the plans for an advanced automatic pilot device that was later used in Luftwaffe

The Luftwaffe () was the aerial warfare, aerial-warfare branch of the before and during World War II. German Empire, Germany's military air arms during World War I, the of the Imperial German Army, Imperial Army and the of the Imperial Ge ...

fighters and bombers. At the time of his arrest, Roeder had 16 guns in his Long Island

Long Island is a densely populated continental island in southeastern New York (state), New York state, extending into the Atlantic Ocean. It constitutes a significant share of the New York metropolitan area in both population and land are ...

home in New York.

Roeder pleaded guilty to espionage and was sentenced to 16 years in prison. In 1949, Roeder published his book, ''Formulas in plane triangles''.

Paul Alfred W. Scholz

A German native, Paul Scholz went to the United States in 1926 but never attained citizenship. He had been employed in German book stores in New York City, where he disseminated Nazi propaganda.

Scholz had arranged for Josef Klein to construct the radio set used by Felix Jahnke and Axel Wheeler-Hill. At the time of his arrest, Scholz had just given Gustav Wilhelm Kaercher a list of radio call letters and frequencies. He also encouraged members of this spy ring to secure data for Germany and arranged contacts between various German agents.

After being convicted at trial, Scholz was sentenced to 16 years in prison for espionage and received a concurrent two-year sentence under the Registration Act.

A German native, Paul Scholz went to the United States in 1926 but never attained citizenship. He had been employed in German book stores in New York City, where he disseminated Nazi propaganda.

Scholz had arranged for Josef Klein to construct the radio set used by Felix Jahnke and Axel Wheeler-Hill. At the time of his arrest, Scholz had just given Gustav Wilhelm Kaercher a list of radio call letters and frequencies. He also encouraged members of this spy ring to secure data for Germany and arranged contacts between various German agents.

After being convicted at trial, Scholz was sentenced to 16 years in prison for espionage and received a concurrent two-year sentence under the Registration Act.

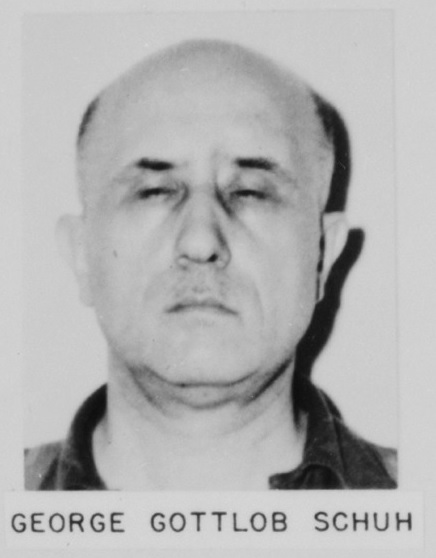

George Gottlob Schuh

George Gottlob Schuh, a native of Germany, went to the United States in 1923. He became a citizen in 1939 and was employed as a

George Gottlob Schuh, a native of Germany, went to the United States in 1923. He became a citizen in 1939 and was employed as a carpenter

Carpentry is a skilled trade and a craft in which the primary work performed is the cutting, shaping and installation of building materials during the construction of buildings, ships, timber bridges, concrete formwork, etc. Carpenter ...

.

As a German agent, he sent information directly to the Gestapo in Hamburg from the United States. Schuh had provided Alfred Brokhoff information that Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

had arrived in the United States on . He also furnished information to Germany concerning the movement of ships carrying materials and supplies to Britain.

Having pleaded guilty to violation of the Registration Act, Schuh received a sentence of 18 months in prison and a $1,000 fine.

Erwin Wilhelm Siegler

Erwin Wilhelm Siegler went to the United States from Germany in 1929 and attained citizenship in 1936. He had served as chief butcher on the until it was taken over by the U.S. Navy.

A courier, Siegler brought microphotographic instructions to Sebold from German authorities on one occasion. He also had brought $2,900 from German contacts abroad to pay Lilly Stein, Duquesne, and Roeder for their services and to buy a bomb sight. He served the espionage group as an organizer and contact man, and he also obtained information about the movement of ships and military defense preparations at the

Erwin Wilhelm Siegler went to the United States from Germany in 1929 and attained citizenship in 1936. He had served as chief butcher on the until it was taken over by the U.S. Navy.

A courier, Siegler brought microphotographic instructions to Sebold from German authorities on one occasion. He also had brought $2,900 from German contacts abroad to pay Lilly Stein, Duquesne, and Roeder for their services and to buy a bomb sight. He served the espionage group as an organizer and contact man, and he also obtained information about the movement of ships and military defense preparations at the Panama Canal

The Panama Canal () is an artificial waterway in Panama that connects the Caribbean Sea with the Pacific Ocean. It cuts across the narrowest point of the Isthmus of Panama, and is a Channel (geography), conduit for maritime trade between th ...

.

After being convicted at trial, Siegler was sentenced to 10 years in prison for espionage and a concurrent two-year term for violating the Registration Act.

Oscar Richard Stabler

Born in Germany, Oscar Richard Stabler went to the United States in 1923 and became a citizen in 1933. He had been employed primarily as a

Born in Germany, Oscar Richard Stabler went to the United States in 1923 and became a citizen in 1933. He had been employed primarily as a barber

A barber is a person whose occupation is mainly to cut, dress, groom, style and shave hair or beards. A barber's place of work is known as a barbershop or the barber's. Barbershops have been noted places of social interaction and public discourse ...

aboard transoceanic ships. In December 1940, British authorities in Bermuda found a map of Gibraltar

Gibraltar ( , ) is a British Overseas Territories, British Overseas Territory and British overseas cities, city located at the southern tip of the Iberian Peninsula, on the Bay of Gibraltar, near the exit of the Mediterranean Sea into the A ...

in his possession. He was detained for a short period before being released. A close associate of Conradin Otto Dold, Stabler served as a courier, transmitting information between German agents in the United States and contacts abroad.

Stabler was convicted and sentenced to five years in prison for espionage and a concurrent two-year term under the Registration Act.

Heinrich Stade

Heinrich Stade went to the United States from Germany in 1922 and became a citizen in 1929. He had been a musician and publicity agent in New York. He told agent Sebold he had been in the Gestapo since 1936 and boasted that he knew everything in the spy business.

Stade had arranged for Paul Bante's contact with Sebold and had transmitted data to Germany regarding points of rendezvous for

Heinrich Stade went to the United States from Germany in 1922 and became a citizen in 1929. He had been a musician and publicity agent in New York. He told agent Sebold he had been in the Gestapo since 1936 and boasted that he knew everything in the spy business.

Stade had arranged for Paul Bante's contact with Sebold and had transmitted data to Germany regarding points of rendezvous for convoys

A convoy is a group of vehicles, typically motor vehicles or ships, traveling together for mutual support and protection. Often, a convoy is organized with armed defensive support and can help maintain cohesion within a unit. It may also be used ...

carrying supplies to England.

Stade was arrested while playing in the orchestra at an inn on Long Island

Long Island is a densely populated continental island in southeastern New York (state), New York state, extending into the Atlantic Ocean. It constitutes a significant share of the New York metropolitan area in both population and land are ...

, New York. Following a guilty plea to violation of the Registration Act, Stade was fined $1,000 and received a 15-month prison sentence.

Lilly Barbara Carola Stein

Born in

Born in Vienna

Vienna ( ; ; ) is the capital city, capital, List of largest cities in Austria, most populous city, and one of Federal states of Austria, nine federal states of Austria. It is Austria's primate city, with just over two million inhabitants. ...

, Stein was a Jewish immigrant who had escaped in 1939 with the help of a U.S. diplomat in Vienna, Vice Consul Ogden Hammond Jr. She later met Hugo Sebold, the espionage instructor who had trained William Sebold (the two men were not related) in Hamburg, Germany. She enrolled in this school and was sent to the United States by way of Sweden in 1939.

In New York, she worked as an artist's model and was said to have moved in New York's social circles. As a German agent her mission was to find her targets at New York nightclubs, sleep with these men, and attempt to blackmail them or otherwise entice them to give up valuable secrets. One FBI agent described her as a "good-looking nymphomaniac". Stein was one of the people to whom Sebold had been instructed to deliver microphotograph instructions upon his arrival in the United States. She frequently met with Sebold to give him information for transmittal to Germany, and her address was used as a return address by other agents in mailing data for Germany.

Stein pleaded guilty and was sentenced to 10 years in prison for espionage and a concurrent two-year term for violating the Registration Act. After her release, she left for France where she found employment at a luxury resort near Strasbourg

Strasbourg ( , ; ; ) is the Prefectures in France, prefecture and largest city of the Grand Est Regions of France, region of Geography of France, eastern France, in the historic region of Alsace. It is the prefecture of the Bas-Rhin Departmen ...

.

Franz Joseph Stigler

In 1931, Franz Joseph Stigler, left Germany for the United States, where he became a citizen in 1939. He had been employed as a crew member and chief baker aboard U.S. ships until his discharge from the when the U.S. Navy converted that ship into . His constant companion was Erwin Siegler, and they operated as couriers in transmitting information between the United States and German agents aboard. Stigler sought to recruit amateur radio operators in the United States as channels of communication to German radio stations. He had also observed and reported defense preparations in the

In 1931, Franz Joseph Stigler, left Germany for the United States, where he became a citizen in 1939. He had been employed as a crew member and chief baker aboard U.S. ships until his discharge from the when the U.S. Navy converted that ship into . His constant companion was Erwin Siegler, and they operated as couriers in transmitting information between the United States and German agents aboard. Stigler sought to recruit amateur radio operators in the United States as channels of communication to German radio stations. He had also observed and reported defense preparations in the Panama Canal Zone

The Panama Canal Zone (), also known as just the Canal Zone, was a International zone#Concessions, concession of the United States located in the Isthmus of Panama that existed from 1903 to 1979. It consisted of the Panama Canal and an area gene ...

and had met with other German agents to advise them in their espionage pursuits. In January 1941, Stigler asked agent Sebold to radio Germany that Prime Minister Winston Churchill had arrived secretly in the U.S. on with Lord Halifax

Edward Frederick Lindley Wood, 1st Earl of Halifax (16 April 1881 – 23 December 1959), known as the Lord Irwin from 1925 until 1934 and the Viscount Halifax from 1934 until 1944, was a British Conservative politician of the 1930s. He h ...

.

Upon conviction, Stigler was sentenced to serve 16 years in prison on espionage charges with two concurrent years for registration violations.

Erich Strunck

A seaman aboard the ships of the

A seaman aboard the ships of the United States Lines

United States Lines was an organization of the United States Shipping Board's (USSB) Emergency Fleet Corporation (EFC), created to operate German liners seized by the United States in 1917. The ships were owned by the USSB and all finances of t ...

since his arrival in the United States, Erich Strunck went to the United States from Germany in 1927. He became a naturalized citizen in 1935. As a courier, Strunck carried messages between German agents in the United States and Europe. He requested authority to steal the diplomatic bag

A diplomatic bag, also known as a diplomatic pouch, is a container with certain legal protections used for carrying official correspondence or other items between a diplomatic mission and its home government or other diplomatic, consular, or other ...

of a British officer traveling aboard his ship and to dispose of the officer by pushing him overboard. Sebold convinced him that it would be too risky to do so.

Strunck was convicted and sentenced to serve 10 years in prison on espionage charges. He also was sentenced to serve a two-year concurrent term under the Registration Act.

Leo Waalen

Leo Waalen was born in Danzig, Germany. He entered the United States by "jumping ship" about 1935. He was a painter for a small boat company which was constructing small craft for the U.S. Navy.

Waalen gathered information about ships sailing for England. He also obtained a confidential booklet issued by the FBI which contained precautions to be taken by industrial plants to safeguard national defense materials from sabotage. He secured government contracts listing specifications for materials and equipment, as well as detailed sea charts of the United States Atlantic coastline.

In May 1941, the American cargo vessel was carrying nine officers, 29 crewmen, seven or eight passengers, and a commercial cargo from New York to

Leo Waalen was born in Danzig, Germany. He entered the United States by "jumping ship" about 1935. He was a painter for a small boat company which was constructing small craft for the U.S. Navy.

Waalen gathered information about ships sailing for England. He also obtained a confidential booklet issued by the FBI which contained precautions to be taken by industrial plants to safeguard national defense materials from sabotage. He secured government contracts listing specifications for materials and equipment, as well as detailed sea charts of the United States Atlantic coastline.

In May 1941, the American cargo vessel was carrying nine officers, 29 crewmen, seven or eight passengers, and a commercial cargo from New York to Mozambique

Mozambique, officially the Republic of Mozambique, is a country located in Southeast Africa bordered by the Indian Ocean to the east, Tanzania to the north, Malawi and Zambia to the northwest, Zimbabwe to the west, and Eswatini and South Afr ...

via South Africa, without a protective convoy. On 21 May, the ship was stopped by ''U-69'' in the tropical Atlantic west of the British-controlled port of Freetown, Sierra Leone

Freetown () is the capital and largest city of Sierra Leone. It is a major port city on the Atlantic Ocean and is located in the Western Area of the country. Freetown is Sierra Leone's major urban, economic, financial, cultural, educational an ...

. Although the ''Robin Moor'' was flying the flag of a neutral country, her mate

Mate may refer to:

Science

* Mate, one of a pair of animals involved in:

** Mate choice, intersexual selection

*** Mate choice in humans

** Mating

* Multi-antimicrobial extrusion protein, or MATE, an efflux transporter family of proteins

Pers ...

was told by the U-boat crew that they had decided to "let us have it". After a brief period for the ship's crew and passengers to board her four lifeboats, the U-boat fired a torpedo and then shelled the vacated ship. Once the ship sank beneath the waves, the submarine's crew pulled up to Captain W.E. Myers' lifeboat, left him with four tins of ersatz bread and two tins of butter, and explained that the ship had been sunk because she was carrying supplies to Germany's enemy. In October 1941, federal prosecutors adduced testimony that Waalen, one of the fourteen accused men who had pleaded not guilty to all charges, had submitted the sailing date of the ''Robin Moor'' for radio transmission to Germany, five days before the ship began her final voyage.

Following his conviction, Waalen was sentenced to 12 years in prison for espionage and a concurrent two-year term for violation of the Registration Act.

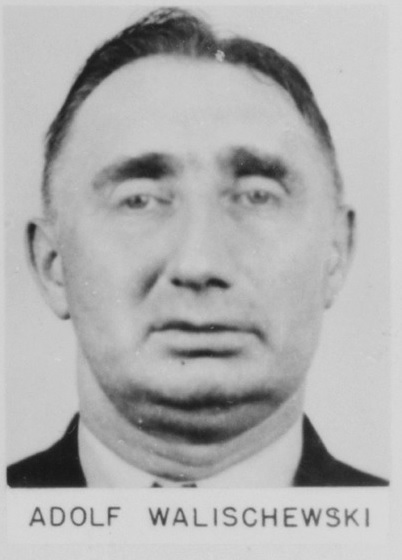

Adolf Henry August Walischewski

A German native, Walischewski had been a seaman since maturity. He became a naturalized citizen in 1935. Walischewski became connected with the German espionage system through Paul Fehse. His duties were confined to those of courier, carrying data from agents in the United States to contacts abroad.

Upon conviction, Walischewski received a five-year prison sentence on espionage charges, as well as a two-year concurrent sentence under the Registration Act.

A German native, Walischewski had been a seaman since maturity. He became a naturalized citizen in 1935. Walischewski became connected with the German espionage system through Paul Fehse. His duties were confined to those of courier, carrying data from agents in the United States to contacts abroad.

Upon conviction, Walischewski received a five-year prison sentence on espionage charges, as well as a two-year concurrent sentence under the Registration Act.

Else Weustenfeld

Else Weustenfeld arrived in the United States from Germany in 1927 and became a citizen 10 years later. From 1935 until her arrest, she was a secretary for a law firm representing the German Consulate in New York City.

Weustenfeld was thoroughly acquainted with the German espionage system and delivered funds to Duquesne which she had received from Lilly Stein, her close friend.

She lived in New York City with Hans W. Ritter, a principal in the German espionage system. His brother, Nickolaus Ritter, was the "Dr. Renken" who had enlisted Sebold as a German agent. In 1940, Weustenfeld visited Hans Ritter in Mexico, where he was serving as a paymaster for the German Intelligence Service.

After pleading guilty, Else Weustenfeld was sentenced to five years' imprisonment on charge of espionage and two concurrent years on a charge of registration violations.

Else Weustenfeld arrived in the United States from Germany in 1927 and became a citizen 10 years later. From 1935 until her arrest, she was a secretary for a law firm representing the German Consulate in New York City.

Weustenfeld was thoroughly acquainted with the German espionage system and delivered funds to Duquesne which she had received from Lilly Stein, her close friend.

She lived in New York City with Hans W. Ritter, a principal in the German espionage system. His brother, Nickolaus Ritter, was the "Dr. Renken" who had enlisted Sebold as a German agent. In 1940, Weustenfeld visited Hans Ritter in Mexico, where he was serving as a paymaster for the German Intelligence Service.

After pleading guilty, Else Weustenfeld was sentenced to five years' imprisonment on charge of espionage and two concurrent years on a charge of registration violations.

Axel Wheeler-Hill

Axel Wheeler-Hill went to the United States in 1923 from his native

Axel Wheeler-Hill went to the United States in 1923 from his native Latvia

Latvia, officially the Republic of Latvia, is a country in the Baltic region of Northern Europe. It is one of the three Baltic states, along with Estonia to the north and Lithuania to the south. It borders Russia to the east and Belarus to t ...

. Between 1918 and 1922, he'd served in the Baltic Freikorps during the Latvian War of Independence

The Latvian War of Independence (), sometimes called Latvia's freedom battles () or the Latvian War of Liberation (), was a series of military conflicts in Latvia between 5 December 1918, after the newly proclaimed Republic of Latvia was invade ...

. He was naturalized as a citizen in 1929 and was employed as a truck driver.

Wheeler-Hill obtained information for Germany regarding ships sailing to Britain from New York Harbor. With Felix Jahnke, he enlisted the aid of Paul Scholz in building a radio set for sending coded messages to Germany.

Following conviction, Wheeler-Hill was sentenced to serve 15 years in prison for espionage and 2 concurrent years under the Registration Act.

Bertram Wolfgang Zenzinger

Born in Germany, Bertram Wolfgang Zenzinger went to the United States in 1940 as a naturalized citizen of the

Born in Germany, Bertram Wolfgang Zenzinger went to the United States in 1940 as a naturalized citizen of the Union of South Africa

The Union of South Africa (; , ) was the historical predecessor to the present-day South Africa, Republic of South Africa. It came into existence on 31 May 1910 with the unification of the British Cape Colony, Cape, Colony of Natal, Natal, Tra ...

. His reported reason for coming to the United States was to study mechanical dentistry in Los Angeles, California

Los Angeles, often referred to by its initials L.A., is the List of municipalities in California, most populous city in the U.S. state of California, and the commercial, Financial District, Los Angeles, financial, and Culture of Los Angeles, ...

.

In July 1940, Zenzinger received a pencil for preparing invisible messages for Germany in the mail from Siegler. He sent several letters to Germany through a mail drop in Sweden, outlining details of national defense materials.

Zenzinger was arrested by FBI agents on April 16, 1941. Pleading guilty, he was sentenced to 8 years in prison for espionage and 18 months in prison for Registration Act.

Liaisons to the Duquesne Spy Ring

Takeo Ezima

Lieutenant Commander Takeo Ezima of the Imperial Japanese Navy operated in New York as an engineer inspector using the name: E. Satoz; code name: KATO.

He arrived on the ''Heian Maru'' in Seattle in 1938. On October 19, 1940, Sebold received a radio message from Germany that CARR (Abwehr Agent Roeder) was to meet E. Satoz at a Japanese club in New York.

Ezima was filmed by the FBI while meeting with agent Sebold in New York, conclusive evidence of German-Japanese cooperation in espionage, in addition to meeting with Kanegoro Koike, Paymaster Commander of the

Lieutenant Commander Takeo Ezima of the Imperial Japanese Navy operated in New York as an engineer inspector using the name: E. Satoz; code name: KATO.

He arrived on the ''Heian Maru'' in Seattle in 1938. On October 19, 1940, Sebold received a radio message from Germany that CARR (Abwehr Agent Roeder) was to meet E. Satoz at a Japanese club in New York.

Ezima was filmed by the FBI while meeting with agent Sebold in New York, conclusive evidence of German-Japanese cooperation in espionage, in addition to meeting with Kanegoro Koike, Paymaster Commander of the Japanese Imperial Navy

The Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN; Kyūjitai: Shinjitai: ' 'Navy of the Greater Japanese Empire', or ''Nippon Kaigun'', 'Japanese Navy') was the navy of the Empire of Japan from 1868 to 1945, when it was dissolved following Japan's surrender ...

assigned to the Office of the Japanese Naval Inspector in New York. Ezima obtained a number of military materials from Duquesne, including ammunition, a drawing of a hydraulic unit with pressure switch A-5 of the Sperry Gyroscope, and an original drawing from the Lawrence Engineering and Research Corporation of a soundproofing installation, and he agreed to deliver materials to Germany via Japan. The British had made the ''Abwehr'' courier route from New York through Lisbon, Portugal difficult, so Ezima arranged an alternate route to the west coast with deliveries every two weeks on freighters destined for Japan.

As the FBI arrested Duquesne and his agents in New York in 1941, Ezima escaped to the west coast, boarded the Japanese freighter ''Kamakura Maru

The was a Japanese passenger ship which, renamed ''Kamakura Maru'', was sunk during World War II, killing 2,035 soldiers and civilians on board.

The ''Chichibu Maru'' was built for the Nippon Yusen shipping company by the Yokohama Dock Company. ...

'', and left for Tokyo. One historian states that Ezima was arrested for espionage in 1942 and sentenced to 15 years; however, U.S. Naval Intelligence documents state that "at the request fthe State Department, Ezima was not prosecuted."

Nikolaus Adolph Fritz Ritter

(Lieutenant colonel)

(Lieutenant colonel) Nikolaus Ritter

Nikolaus Ritter (8 January 1899 – 9 April 1974) is best known as the Chief of Air Intelligence in the Abwehr (German military intelligence) who led spyrings in the United Kingdom and the United States from 1936 to 1941.

Early life

Ritter wa ...