Eric Coates on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Eric Francis Harrison Coates (27 August 1886 – 21 December 1957) was an English composer of

"Coates, Eric (formerly Frank Harrison Coates)"

''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'', Oxford University Press, 2004. As a child, Coates did not go to school, but was educated with his sisters by a

Boosey and Hawkes. Retrieved 29 September 2018 Coates himself said that Wood valued reliability more than virtuosity, and had become exasperated by Coates's frequent absences conducting his compositions elsewhere.

What Coates's biographer Geoffrey Self describes as "a not-too-onerous contract with his publisher" stipulated an annual output of two orchestral pieces – one of fifteen minutes' duration and one of five – and three ballads. Coates was a founder-member of the

What Coates's biographer Geoffrey Self describes as "a not-too-onerous contract with his publisher" stipulated an annual output of two orchestral pieces – one of fifteen minutes' duration and one of five – and three ballads. Coates was a founder-member of the

''Dictionary of National Biography'' archive, Oxford University Press. Retrieved 29 September 2018. Although he and his wife maintained a country house in Sussex, Coates found city life more stimulating, and was more productive when at the family's London flat in

On 28 November 1957 Coates made one of his final public appearances at a fund-raising dinner for the Musicians Benevolent Fund held at the

On 28 November 1957 Coates made one of his final public appearances at a fund-raising dinner for the Musicians Benevolent Fund held at the

Coates's orchestral works are the core of his output, and are the best known. He wrote a few works outside his normal genre – a rhapsody for saxophone and orchestra in 1936 and a "symphonic rhapsody" on

Coates's orchestral works are the core of his output, and are the best known. He wrote a few works outside his normal genre – a rhapsody for saxophone and orchestra in 1936 and a "symphonic rhapsody" on

Biography at the Robert Farnon Society

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Coates, Eric 1886 births 1957 deaths 20th-century English classical composers 20th-century English male musicians 20th-century British violists Alumni of the Royal Academy of Music English classical violists English film score composers English light music composers English male film score composers Golders Green Crematorium People from Hucknall

light music

Light music is a less-serious form of Western classical music, which originated in the 18th and 19th centuries and continues today. Its heyday was in the mid‑20th century. The style is through-composed, usually shorter orchestral pieces and ...

and, early in his career, a leading violist.

Coates was born into a musical family, but, despite his wishes and obvious talent, his parents only reluctantly allowed him to pursue a musical career. He studied at the Royal Academy of Music

The Royal Academy of Music (RAM) in London, England, is one of the oldest music schools in the UK, founded in 1822 by John Fane and Nicolas-Charles Bochsa. It received its royal charter in 1830 from King George IV with the support of the firs ...

under Frederick Corder (composition) and Lionel Tertis

Lionel Tertis, Commander of the Order of the British Empire, CBE (29 December 187622 February 1975) was an English viola, violist. He was one of the first viola players to achieve international fame, and a noted teacher.

Career

Tertis was born ...

(viola), and played in string quartet

The term string quartet refers to either a type of musical composition or a group of four people who play them. Many composers from the mid-18th century onwards wrote string quartets. The associated musical ensemble consists of two Violin, violini ...

s and theatre pit bands, before joining symphony orchestras conducted by Thomas Beecham

Sir Thomas Beecham, 2nd Baronet, (29 April 18798 March 1961) was an English conductor and impresario best known for his association with the London Philharmonic Orchestra, London Philharmonic and the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, Royal Philh ...

and Henry Wood

Sir Henry Joseph Wood (3 March 186919 August 1944) was an English conductor best known for his association with London's annual series of promenade concerts, known as the Proms. He conducted them for nearly half a century, introducing hundr ...

. Coates's experience as a player added to the rigorous training he had received at the academy and contributed to his skill as a composer.

While still working as a violist, Coates composed songs and other light musical works. In 1919 he gave up the viola permanently and from then until his death he made his living as a composer and occasional conductor. His prolific output includes the '' London Suite'' (1932), of which the well-known "Knightsbridge March" is the concluding section; the waltz " By the Sleepy Lagoon" (1930); and "The Dam Busters March

''The Dam Busters'' is the theme for the 1955 British war film '' The Dam Busters''. The musical composition, by Eric Coates, has become synonymous with both the film and the real Operation Chastise. ''The Dam Busters March'' remains a very pop ...

" (1954). His early compositions were influenced by the music of Arthur Sullivan

Sir Arthur Seymour Sullivan (13 May 1842 – 22 November 1900) was an English composer. He is best known for 14 comic opera, operatic Gilbert and Sullivan, collaborations with the dramatist W. S. Gilbert, including ''H.M.S. Pinaf ...

and Edward German

Sir Edward German (born German Edward Jones; 17 February 1862 – 11 November 1936) was an English musician and composer of Welsh descent, best remembered for his extensive output of incidental music for the stage and as a successor to Arthur S ...

, but Coates's style evolved in step with changes in musical taste, and his later works incorporate elements derived from jazz and dance-band music. His output consists almost wholly of orchestral music and songs. With the exception of one unsuccessful short ballet, he never wrote for the theatre, and only occasionally for the cinema.

Life and career

Early years

Coates was born in Hucknall Torkard, Nottinghamshire, the only son, and youngest of five children, of William Harrison Coates (1851–1935), a medicalgeneral practitioner

A general practitioner (GP) is a doctor who is a Consultant (medicine), consultant in general practice.

GPs have distinct expertise and experience in providing whole person medical care, whilst managing the complexity, uncertainty and risk ass ...

, and his wife, Mary Jane Gwyn, ''née'' Blower (1850–1928). It was a musical household: Dr Coates was a capable amateur flautist

The flute is a member of a family of musical instruments in the woodwind group. Like all woodwinds, flutes are aerophones, producing sound with a vibrating column of air. Flutes produce sound when the player's air flows across an opening. In th ...

and singer, and his wife was a fine pianist.Self, Geoffrey"Coates, Eric (formerly Frank Harrison Coates)"

''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'', Oxford University Press, 2004. As a child, Coates did not go to school, but was educated with his sisters by a

governess

A governess is a woman employed as a private tutor, who teaches and trains a child or children in their home. A governess often lives in the same residence as the children she is teaching; depending on terms of their employment, they may or ma ...

. His musicality became clear when he was very young, and asked to be taught to play the violin. His first lessons, from age six, were with a local violin teacher, and from thirteen he studied with George Ellenberger, who was once a pupil of Joseph Joachim

Joseph Joachim (28 June 1831 – 15 August 1907) was a Hungarian Violin, violinist, Conducting, conductor, composer and teacher who made an international career, based in Hanover and Berlin. A close collaborator of Johannes Brahms, he is widely ...

. Coates also took lessons in harmony

In music, harmony is the concept of combining different sounds in order to create new, distinct musical ideas. Theories of harmony seek to describe or explain the effects created by distinct pitches or tones coinciding with one another; harm ...

and counterpoint

In music theory, counterpoint is the relationship of two or more simultaneous musical lines (also called voices) that are harmonically dependent on each other, yet independent in rhythm and melodic contour. The term originates from the Latin ...

from Ralph Horner, lecturer in music at University College Nottingham, who had studied under Ignaz Moscheles

Isaac Ignaz Moscheles (; 23 May 179410 March 1870) was a Bohemian piano virtuoso and composer. He was based initially in London and later at Leipzig, where he joined his friend and sometime pupil Felix Mendelssohn as professor of piano in the Co ...

and Ernst Richter and was a former conductor for the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company

The D'Oyly Carte Opera Company is a professional British light opera company that, from the 1870s until 1982, staged Gilbert and Sullivan's Savoy operas nearly year-round in the UK and sometimes toured in Europe, North America and elsewhere. The ...

. At Ellenberger's request, Coates switched to the viola

The viola ( , () ) is a string instrument of the violin family, and is usually bowed when played. Violas are slightly larger than violins, and have a lower and deeper sound. Since the 18th century, it has been the middle or alto voice of the ...

, supposedly for a single performance; he found the deeper sound of the instrument to his liking and changed permanently from violinist to violist. In that capacity he joined a local string orchestra, for which he wrote his first surviving music, the ''Ballad'', op. 2, dedicated to Ellenberger. It was completed on 23 October 1904 and performed later that year at the Albert Hall, Nottingham, with Coates playing in the viola section.

Coates wanted to pursue a career as a professional musician; his parents were not in favour of it, but eventually agreed that he could seek admission to the Royal Academy of Music

The Royal Academy of Music (RAM) in London, England, is one of the oldest music schools in the UK, founded in 1822 by John Fane and Nicolas-Charles Bochsa. It received its royal charter in 1830 from King George IV with the support of the firs ...

(RAM) in London. They insisted that by the end of his first year there he must have demonstrated that his abilities were equal to a professional career, failing which he was to return to Nottinghamshire and take up a safe and respectable post in a bank. In 1906, aged twenty, Coates auditioned for admission; he was interviewed by the principal, Sir Alexander Mackenzie

Sir Alexander Mackenzie ( – 12 March 1820) was a Scottish explorer and fur trader known for accomplishing the first crossing of North America north of Mexico by a European in 1793. The Mackenzie River and Mount Sir Alexander are named afte ...

, who was sufficiently impressed by the applicant's setting of Burns

Burns may refer to:

Astronomy

* 2708 Burns, an asteroid

* Burns (crater), on Mercury

People

* Burns (surname), list of people and characters named Burns

** Burns (musician), Scottish record producer

Places in the United States

* Burns, ...

's "A Red, Red Rose

"A Red, Red Rose" is a 1794 song in Scots by Robert Burns based on traditional sources. The song is also referred to by the title "(Oh) My Love is Like a Red, Red Rose" and is often published as a poem. Many composers have set Burns' lyric to ...

" to suggest that Coates should take composition as his principal study, with the viola as subsidiary. Coates was adamant that his first concern was the viola. Mackenzie's enthusiasm did not extend to offering a scholarship

A scholarship is a form of Student financial aid, financial aid awarded to students for further education. Generally, scholarships are awarded based on a set of criteria such as academic merit, Multiculturalism, diversity and inclusion, athleti ...

, and Dr Coates had to pay the tuition fees for his son's first year, after which a scholarship was granted.

At the RAM Coates studied the viola with Lionel Tertis

Lionel Tertis, Commander of the Order of the British Empire, CBE (29 December 187622 February 1975) was an English viola, violist. He was one of the first viola players to achieve international fame, and a noted teacher.

Career

Tertis was born ...

and composition with Frederick Corder. Coates made it clear to Corder that he was temperamentally drawn to writing music in a light vein rather than symphonies or oratorios. His songs featured in RAM concerts during his years as a student, and although his first press review called his two songs performed in December 1907 "rather obvious", his four Shakespeare settings were praised the following year for the "charm of a sincere melody". and his "Devon to Me" (also 1908) was credited by ''The Musical Times

''The Musical Times'' was an academic journal of classical music edited and produced in the United Kingdom.

It was originally created by Joseph Mainzer in 1842 as ''Mainzer's Musical Times and Singing Circular'', but in 1844 he sold it to Alfr ...

'' as "a robust and manly ditty, worthy of publication".

Coates was fortunate in his viola professor. ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

'' called Tertis the first great protagonist of the instrument, and ''Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians

''The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians'' is an encyclopedic dictionary of music and musicians. Along with the German-language '' Die Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart'', it is one of the largest reference works on the history and th ...

'' ranks him as the foremost player of the viola. He was also regarded as a great teacher, and under his tutelage Coates developed into a first-rate viola player. While still a student he earned money playing in theatre orchestras in the West End, including the Savoy

Savoy (; ) is a cultural-historical region in the Western Alps. Situated on the cultural boundary between Occitania and Piedmont, the area extends from Lake Geneva in the north to the Dauphiné in the south and west and to the Aosta Vall ...

, where he played for several weeks under François Cellier

François Arsène Cellier (14 December 1849 – 5 January 1914), often called Frank, was an English conductor and composer. He is known for his tenure as musical director and conductor of the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company during the original run ...

in a Gilbert and Sullivan

Gilbert and Sullivan refers to the Victorian-era theatrical partnership of the dramatist W. S. Gilbert (1836–1911) and the composer Arthur Sullivan (1842–1900) and to the works they jointly created. The two men collaborated on fourteen com ...

season in 1907.

Professional violist and composer: 1908–1919

In 1908 Coates's studies at the RAM came to an unexpected end when Tertis had to drop out of a tour of South Africa as a member of the Hambourg Quartet, a leading string ensemble; he arranged for Coates to be invited to fill the vacancy. Coates resigned his scholarship at the academy and joined the tour. At about this time he began to be troubled by pain in his left hand and numbness in his right, which were symptoms of theneuritis

Neuritis (), from the Greek ), is inflammation of a nerve or the general inflammation of the peripheral nervous system. Inflammation, and frequently concomitant demyelination, cause impaired transmission of neural signals and leads to aberrant ne ...

that affected him throughout the remaining eleven years of his career as a violist. After working with the Hambourg Quartet, Coates was violist of the Cathie and Walenn quartets."Mr Eric Coates", ''The Times'', 23 December 1957, p. 8

Alongside his busy playing career, Coates had several early successes as a composer. The soprano

A soprano () is a type of classical singing voice and has the highest vocal range of all voice types. The soprano's vocal range (using scientific pitch notation) is from approximately middle C (C4) = 261 Hertz, Hz to A5 in Choir, choral ...

Olga Wood, wife of the conductor Henry Wood

Sir Henry Joseph Wood (3 March 186919 August 1944) was an English conductor best known for his association with London's annual series of promenade concerts, known as the Proms. He conducted them for nearly half a century, introducing hundr ...

, sang Coates's "Four Old English Songs" at the Proms

The BBC Proms is an eight-week summer season of daily orchestral classical music concerts and other events held annually, predominantly in the Royal Albert Hall in central London. Robert Newman founded The Proms in 1895. Since 1927, the ...

in 1909; the music critic of ''The Times'' wrote that they were "tuneful, somewhat in the manner of Mr. Edward German

Sir Edward German (born German Edward Jones; 17 February 1862 – 11 November 1936) was an English musician and composer of Welsh descent, best remembered for his extensive output of incidental music for the stage and as a successor to Arthur S ...

", and showed the influence of Arthur Sullivan

Sir Arthur Seymour Sullivan (13 May 1842 – 22 November 1900) was an English composer. He is best known for 14 comic opera, operatic Gilbert and Sullivan, collaborations with the dramatist W. S. Gilbert, including ''H.M.S. Pinaf ...

in the word-setting. The songs were taken up by other prominent singers including Gervase Elwes, Carrie Tubb and Nellie Melba

Dame Nellie Melba (born Helen Porter Mitchell; 19 May 186123 February 1931) was an Australian operatic lyric coloratura soprano. She became one of the most famous singers of the late Victorian era and the early twentieth century, and was the f ...

.Ponder, Michael (1995). Notes to Naxos CD 8.223806 The composer's many collaborations with the lyricist Frederic Weatherly

Frederic Edward Weatherly, KC (4 October 1848 – 7 September 1929) was an English lawyer, author, lyricist and broadcaster. He was christened and brought up using the name Frederick Edward Weatherly, and appears to have adopted the spelling 'F ...

began with "Stonecracker John" (1909), the first of a succession of highly popular ballads. Wood was the dedicatee of the ''Miniature Suite'', the last movement of which was encored when he conducted its first performance, at the Proms, in October 1911.

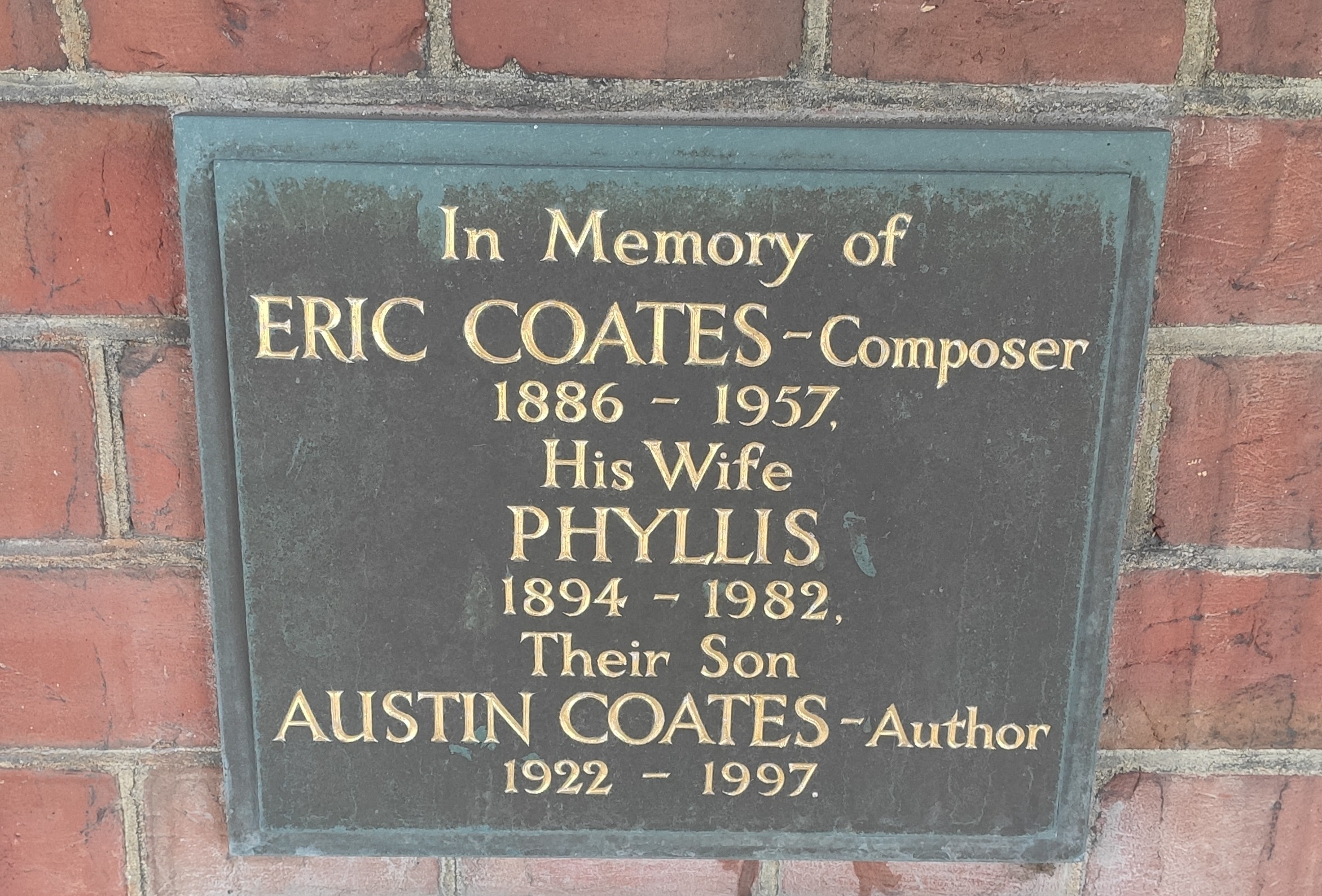

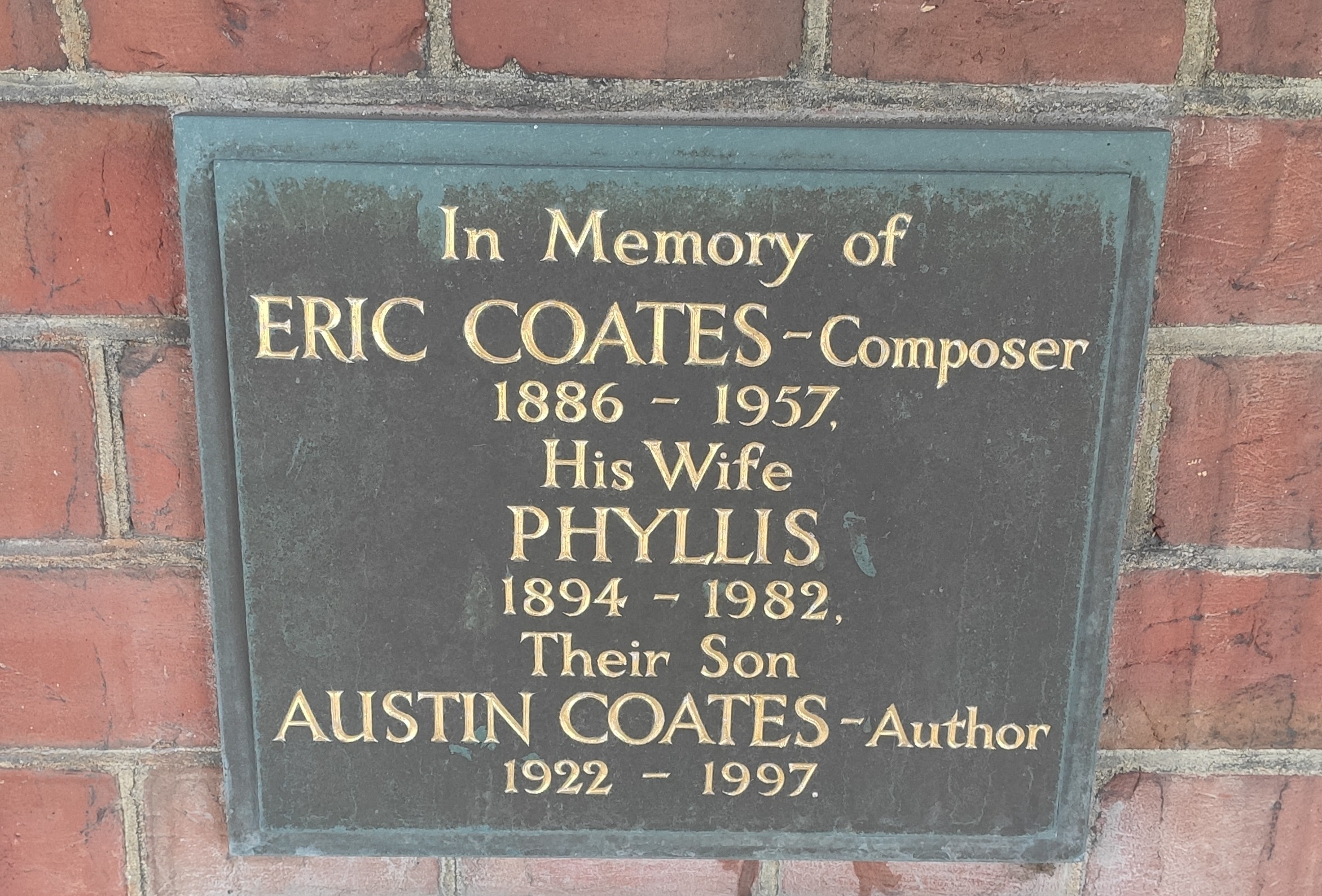

In early 1911 Coates met and fell in love with an RAM student, Phyllis (Phyl) Marguerite Black (1894–1982), an aspiring actress, who was studying recitation. His affections were reciprocated but her parents were doubtful of Coates's prospects as a husband and provider. Although he continued to compose, he was concentrating for the time being on playing the viola for his principal income, first with the Beecham Symphony Orchestra, and, from 1910, with Wood's Queen's Hall

The Queen's Hall was a concert hall in Langham Place, London, Langham Place, London, opened in 1893. Designed by the architect Thomas Knightley, it had room for an audience of about 2,500 people. It became London's principal concert venue. Fro ...

Orchestra. He played under the batons of composers including Elgar

Sir Edward William Elgar, 1st Baronet, (; 2 June 1857 – 23 February 1934) was an English composer, many of whose works have entered the British and international classical concert repertoire. Among his best-known compositions are orchestr ...

, Delius, Holst

Gustav Theodore Holst (born Gustavus Theodore von Holst; 21 September 1874 – 25 May 1934) was an English composer, arranger and teacher. Best known for his orchestral suite ''The Planets'', he composed many other works across a range ...

, Richard Strauss

Richard Georg Strauss (; ; 11 June 1864 – 8 September 1949) was a German composer and conductor best known for his Tone poems (Strauss), tone poems and List of operas by Richard Strauss, operas. Considered a leading composer of the late Roman ...

, Debussy

Achille Claude Debussy (; 22 August 1862 – 25 March 1918) was a French composer. He is sometimes seen as the first Impressionism in music, Impressionist composer, although he vigorously rejected the term. He was among the most influe ...

, and virtuoso conductors such as Willem Mengelberg

Joseph Wilhelm Mengelberg (28 March 1871 – 21 March 1951) was a Dutch conductor, famous for his performances of Beethoven, Brahms, Mahler and Strauss with the Concertgebouw Orchestra in Amsterdam. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest ...

and Arthur Nikisch

Arthur Nikisch (12 October 185523 January 1922) was a Hungary, Hungarian conducting, conductor who performed internationally, holding posts in Boston, London, Leipzig and—most importantly—Berlin. He was considered an outstanding interpreter ...

. This work gave him the necessary financial security to marry Phyllis in February 1913. They had one child, Austin

Austin refers to:

Common meanings

* Austin, Texas, United States, a city

* Austin (given name), a list of people and fictional characters

* Austin (surname), a list of people and fictional characters

* Austin Motor Company, a British car manufac ...

, born in 1922.

Coates was declared medically unfit for military service in the First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, and continued his musical career. The war brought about a severe reduction in work, and the couple's income received a welcome boost from Phyllis's acting engagements. As her career progressed, she appeared with other rising performers including Noël Coward

Sir Noël Peirce Coward (16 December 189926 March 1973) was an English playwright, composer, director, actor, and singer, known for his wit, flamboyance, and what ''Time (magazine), Time'' called "a sense of personal style, a combination of c ...

.

In 1919 Coates gave up playing the viola. His contract to lead the section in the Queen's Hall orchestra expired and was not renewed. Some sources ascribe this to Coates's wish to pursue a full-time career as a composer; others say that his neuritis affected his playing;"Eric Coates"Boosey and Hawkes. Retrieved 29 September 2018 Coates himself said that Wood valued reliability more than virtuosity, and had become exasperated by Coates's frequent absences conducting his compositions elsewhere.

Full-time composer: 1920s and 1930s

Whether or not Wood had lost patience with Coates as a violist, he regarded him well enough as a composer to invite him to conduct the first performance of his suite ''Summer Days'' at a Queen's HallPromenade concert

Promenade concerts were musical performances in the 18th and 19th century pleasure gardens of London, where the audience would stroll about while listening to the music. The term derives from the French ''se promener'', "to walk".

Today, the t ...

in October 1919, and to engage him for repeat performances of the piece in 1920, 1924 and 1925, and for more of his orchestral works including the suite ''Joyous Youth'' (1922) and the premiere of ''The Three Bears'' (1926). The latter, one of three of Coates's most substantial works, labelled "Phantasies", was inspired by the children's stories that Phyllis Coates read to their son; the others were ''The Selfish Giant'' (1925) and ''Cinderella'' (1930).

What Coates's biographer Geoffrey Self describes as "a not-too-onerous contract with his publisher" stipulated an annual output of two orchestral pieces – one of fifteen minutes' duration and one of five – and three ballads. Coates was a founder-member of the

What Coates's biographer Geoffrey Self describes as "a not-too-onerous contract with his publisher" stipulated an annual output of two orchestral pieces – one of fifteen minutes' duration and one of five – and three ballads. Coates was a founder-member of the Performing Right Society

PRS for Music Limited (formerly The MCPS-PRS Alliance Limited) is a British music copyright collective, made up of two collection societies: the Mechanical-Copyright Protection Society (MCPS) and the Performing Right Society (PRS). It undertakes ...

, and was among the first composers whose main income came from broadcasts and recordings, after the demand for sheet music of popular songs declined in the 1920s and 1930s.

Between the First and Second

The second (symbol: s) is a unit of time derived from the division of the day first into 24 hours, then to 60 minutes, and finally to 60 seconds each (24 × 60 × 60 = 86400). The current and formal definition in the International System of U ...

world wars, Coates was in demand as a conductor of his own works, appearing in London and seaside resorts such as Bournemouth

Bournemouth ( ) is a coastal resort town in the Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole unitary authority area, in the ceremonial county of Dorset, England. At the 2021 census, the built-up area had a population of 196,455, making it the largest ...

, Scarborough Scarborough or Scarboro may refer to:

People

* Scarborough (surname)

* Earl of Scarbrough

Places Australia

* Scarborough, Western Australia, suburb of Perth

* Scarborough, New South Wales, suburb of Wollongong

* Scarborough, Queensland, sub ...

and Hastings

Hastings ( ) is a seaside town and Borough status in the United Kingdom, borough in East Sussex on the south coast of England,

east of Lewes and south east of London. The town gives its name to the Battle of Hastings, which took place to th ...

, which then maintained substantial orchestras devoted to light music. But it was in the studio that he made the most impact as a composer-conductor. Beginning in 1923 he made records of his music for Columbia, which attracted a substantial following. Among those who bought his records was Elgar, who made a point of buying all Coates's discs as they came out."Coates, Eric"''Dictionary of National Biography'' archive, Oxford University Press. Retrieved 29 September 2018. Although he and his wife maintained a country house in Sussex, Coates found city life more stimulating, and was more productive when at the family's London flat in

Baker Street

Baker Street is a street in the Marylebone district of the City of Westminster in London. It is named after builder James Baker. The area was originally high class residential, but now is mainly occupied by commercial premises.

The street is ...

. The views from there across the roofscapes prompted his '' London Suite'' (1933), with its depictions of Covent Garden

Covent Garden is a district in London, on the eastern fringes of the West End, between St Martin's Lane and Drury Lane. It is associated with the former fruit-and-vegetable market in the central square, now a popular shopping and tourist sit ...

, Westminster

Westminster is the main settlement of the City of Westminster in Central London, Central London, England. It extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street and has many famous landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, Buckingham Palace, ...

and Knightsbridge

Knightsbridge is a residential and retail district in central London, south of Hyde Park, London, Hyde Park. It is identified in the London Plan as one of two international retail centres in London, alongside the West End of London, West End. ...

. The work transformed Coates's status from moderate prominence to national celebrity when the BBC

The British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) is a British public service broadcaster headquartered at Broadcasting House in London, England. Originally established in 1922 as the British Broadcasting Company, it evolved into its current sta ...

chose the "Knightsbridge" march from the suite as the signature tune for its new and prodigiously popular radio programme '' In Town Tonight'', which ran from 1933 to 1960.

Another work written at the Baker Street flat that enhanced the composer's fame was '' By the Sleepy Lagoon'' (1930), an orchestral piece that made little initial impression, but with an added lyric became a hit song in the US in 1940, and in its original instrumental version became familiar in Britain as the title music of the BBC radio series ''Desert Island Discs

''Desert Island Discs'' is a radio programme broadcast on BBC Radio 4. It was first broadcast on the BBC Forces Programme on 29 January 1942.

Each week a guest, called a " castaway" during the programme, is asked to choose eight audio recordin ...

'' which began in 1942 and (in 2023) is still running.

Later years: 1940–1957

During the early part of the Second World War, Coates composed little until his wife suggested he might write something for the staff at theRed Cross

The organized International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement is a Humanitarianism, humanitarian movement with approximately 16million volunteering, volunteers, members, and staff worldwide. It was founded to protect human life and health, to ...

depot where she was a volunteer worker. The result, the march "Calling All Workers" became one of his best known pieces, benefiting from use as another BBC signature tune, this time for the popular series '' Music While You Work''. At the BBC's request he wrote a report on light music on radio, completed in 1943. Some of his findings and recommendations were accepted but, according to a biographical sketch by Tim McDonald, Coates "failed to bring about any significant lessening of the inherent snobbery within the Corporation which tended to take a rather dismissive view of light music".

Coates was a director of the Performing Right Society, which he represented at international conferences after the war in company with William Walton

Sir William Turner Walton (29 March 19028 March 1983) was an English composer. During a sixty-year career, he wrote music in several classical genres and styles, from film scores to opera. His best-known works include ''Façade'', the cantat ...

, A. P. Herbert and others. His autobiography, ''Suite in Four Movements'', was published in 1953. The following year one of his last works became one of his best known. A march theme occurred to him, and he wrote it out and scored it with no particular end in view. Within days the producers of a forthcoming film, '' The Dam Busters'', asked Coates's publishers if he would be willing to provide a march for the film. The new piece was incorporated in the soundtrack and was a considerable success. In a 2003 study of the music for war films, Stuart Jeffries commented that the closing credits of ''The Dam Busters'', with the march as a valedictory anthem, would make later composers of such music despair of matching it.

On 28 November 1957 Coates made one of his final public appearances at a fund-raising dinner for the Musicians Benevolent Fund held at the

On 28 November 1957 Coates made one of his final public appearances at a fund-raising dinner for the Musicians Benevolent Fund held at the Savoy Hotel

The Savoy Hotel is a luxury hotel located in the Strand in the City of Westminster in central London, England. Built by the impresario Richard D'Oyly Carte with profits from his Gilbert and Sullivan opera productions, it opened on 6 August 1 ...

, playing dulcimer in the premiere performance of Malcolm Arnold

Sir Malcolm Henry Arnold (21 October 1921 – 23 September 2006) was an English composer. His works feature music in many genres, including a cycle of nine symphonies, numerous concertos, concert works, chamber music, choral music and music f ...

's Toy Symphony

The Toy Symphony (original titles: ''Berchtoldsgaden Musick'' or ''Sinphonia Berchtolgadensis'') is a symphony in C major dating from the 1760s with parts for toy instruments, including toy trumpet, Ratchet (instrument), ratchet, bird calls (cucko ...

. On 17 December, he suffered a stroke

Stroke is a medical condition in which poor cerebral circulation, blood flow to a part of the brain causes cell death. There are two main types of stroke: brain ischemia, ischemic, due to lack of blood flow, and intracranial hemorrhage, hemor ...

while at the family's Sussex house and died in the Royal West Sussex Hospital, Chichester

Chichester ( ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and civil parish in the Chichester District, Chichester district of West Sussex, England.OS Explorer map 120: Chichester, South Harting and Selsey Scale: 1:25 000. Publisher ...

after four days there, aged 71. He was cremated at the Golders Green Crematorium

Golders Green Crematorium and Mausoleum was the first crematorium to be opened in London, and is one of the oldest crematoria in Britain. The land for the crematorium was purchased in 1900, costing £6,000 (the equivalent of £136,000 in 2021), ...

.

Music

In ''Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians

''The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians'' is an encyclopedic dictionary of music and musicians. Along with the German-language '' Die Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart'', it is one of the largest reference works on the history and th ...

'', Geoffrey Self writes that Coates consistently recognised and accommodated new fashions in music. As contemporary reviewers observed, his early compositions showed the influence of Sullivan and German, but as the 20th century progressed, Coates absorbed and made use of features of the music of Elgar and Richard Strauss. Coates and his wife were keen dancers, and in the 1920s he made use of the new syncopated dance-band styles. ''The Selfish Giant'' (1925) and ''The Three Bears'' (1926) show this distantly jazz-derived aspect of Coates's music, with chromatic counter-melodies and use of muted brass.

Self sums up the characteristics of Coates's music as "strong melody, foot-tapping rhythm, brilliant counterpoints, and colourful orchestration". Coates derived the effective orchestration of his scores from his rigorous early training, experience in theatre pits of the practicalities of orchestration and arranging, and from hearing the symphony orchestra from the inside as a viola player. In the works of some composers, orchestral viola parts are frequently uninteresting to play, and having had to do so in Beecham's and Wood's orchestra, Coates was determined that his own compositions would have interesting and colourful music for every instrument of the orchestra.

Coates and his music attracted a certain amount of snobbery:"Eric Coates", ''The Manchester Guardian'', 23 December 1957, p. 8 ''The Times'' characterised his music as "fundamentally commonplace … but well written, easy on the ear and lightly sentimental … superficial but sincere". In its obituary notice, ''The Manchester Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in Manchester in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'' and changed its name in 1959, followed by a move to London. Along with its sister paper, ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardi ...

'' took issue with such a dismissal, and preferred the French attitude of cherishing ''petits-maîtres'' for what they were rather than condemning them for what they were not: "better to write second-class masterpieces than fail to be a second Beethoven". One of Coates's most important musical gifts was the ability to write memorable tunes – "a genuine lyrical impulse" as ''The Manchester Guardian'' put it. On first meeting him Dame Ethel Smyth said, "You are the man who writes tunes", and asked him how he did it.

Orchestral

Coates's orchestral works are the core of his output, and are the best known. He wrote a few works outside his normal genre – a rhapsody for saxophone and orchestra in 1936 and a "symphonic rhapsody" on

Coates's orchestral works are the core of his output, and are the best known. He wrote a few works outside his normal genre – a rhapsody for saxophone and orchestra in 1936 and a "symphonic rhapsody" on Richard Rodgers

Richard Charles Rodgers (June 28, 1902 – December 30, 1979) was an American Musical composition, composer who worked primarily in musical theater. With 43 Broadway theatre, Broadway musicals and over 900 songs to his credit, Rodgers wa ...

's "With a song in my heart" – his only treatment of music by another composer. The most extended of his orchestral works (at just under 20 minutes in length) is the tone poem ''The Enchanted Garden'' (1938), derived from an abortive ballet on the theme of the Seven Dwarfs, originally composed for André Charlot

Eugène André Maurice Charlot (26 July 1882 – 20 May 1956) was a French-born impresario known primarily for the musical revues he staged in London between 1912 and 1937. He later worked as a character actor in numerous American films.

Born in ...

. But in the main his orchestral works fall into categories: suites, phantasies, marches and waltzes, plus a stand-alone overture and other short orchestral items.

Of the thirteen suites, the most often played are the ''London Suite'' (1932), ''London Again'' (1936) and a later work, ''The Three Elizabeths'' (1944), alluding musically first to Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was List of English monarchs, Queen of England and List of Irish monarchs, Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. She was the last and longest reigning monarch of the House of Tudo ...

, then Elizabeth of Glamis (the then queen consort), and finally the latter's elder daughter, the future Elizabeth II

Elizabeth II (Elizabeth Alexandra Mary; 21 April 19268 September 2022) was Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms from 6 February 1952 until Death and state funeral of Elizabeth II, her death in 2022. ...

. The suites generally follow a pattern of robust outer movements with a more reflective inner movement. Of the seven stand-alone waltzes, the best known, "By the Sleepy Lagoon" (1930), is described as a "valse-serenade", although over the years it has been rendered as a beguine

The Beguines () and the Beghards () were Christianity, Christian laity, lay religious orders that were active in Western Europe, particularly in the Low Countries, in the 13th–16th centuries. Their members lived in monasticism, semi-monastic ...

, a slow waltz and a slow fox-trot.

In his orchestral scores Coates was particular about metronome

A metronome () is a device that produces an audible click or other sound at a uniform interval that can be set by the user, typically in beats per minute (BPM). Metronomes may also include synchronized visual motion, such as a swinging pendulum ...

markings and accents. When conducting his music, he tended to set fairly brisk tempi, and disliked it when other conductors took his works at slower speeds that, to his mind, made them drag.

Songs

Coates's first published works were the "Four Old English Songs", written while he was still a student at the RAM. By the end of the 20th century his songs had become much less well known than his orchestral music, but when they were written they were an essential and highly popular part of his output. ''Grove'' lists 155 songs, beginning with the three Burns settings (1903) that favourably impressed Mackenzie, and ending with "The Scent of Lilac" (1954) to words by Winifred May. By the mid-1920s the demand for ballads and other traditional types of song was in decline, and Coates's output dropped accordingly. The violist and music scholar Michael Ponder writes that Coates, who was principally interested in writing orchestral music, found writing songs limiting and did so chiefly to fulfil his contract with his publisher. Nevertheless, Ponder considers that some of Coates's later songs show him at his finest. He praises "Because I miss you so" and "The Young Lover" (both 1930) for their "rich, glorious melodic vocal line" supported by "subtle piano writing that maintains the unity and intensifies the colour and effect of the vocal line". Almost all the songs, whether from the composer's early, middle or late periods, are in a slow or fairly slow tempo. Ponder comments that Coates's last songs were on a grander scale, perhaps influenced by the big numbers in West End andBroadway

Broadway may refer to:

Theatre

* Broadway Theatre (disambiguation)

* Broadway theatre, theatrical productions in professional theatres near Broadway, Manhattan, New York City, U.S.

** Broadway (Manhattan), the street

** Broadway Theatre (53rd Stre ...

shows.

Coates chose texts by a wide range of authors, including Shakespeare, Christina Rossetti

Christina Georgina Rossetti (5 December 1830 – 29 December 1894) was an English writer of romanticism, romantic, devotional and children's poems, including "Goblin Market" and "Remember". She also wrote the words of two Christmas carols well k ...

, Arthur Conan Doyle

Sir Arthur Ignatius Conan Doyle (22 May 1859 – 7 July 1930) was a British writer and physician. He created the character Sherlock Holmes in 1887 for ''A Study in Scarlet'', the first of four novels and fifty-six short stories about Hol ...

; among those whose words he set most often were Weatherly, Phyllis Black (Mrs Coates), and Royden Barrie. On one occasion he wrote his own words: "A Bird's Lullaby" (1911).

Other music

Coates always conceived his music in orchestral terms, even when writing for solo voice and piano. Despite his background as a member of three string quartets, he composed little chamber music. ''Grove'' lists five such works by Coates, three of which are lost. The two surviving pieces are a minuet for string quartet from 1908, and "First Meeting" (1941) for viola and piano. Similarly, although he learned a substantial part of his craft while playing in theatre orchestras, Coates wrote no musical shows. When he toured with theLondon Philharmonic Orchestra

The London Philharmonic Orchestra (LPO) is a British orchestra based in London. One of five permanent symphony orchestras in London, the LPO was founded by the conductors Thomas Beecham, Sir Thomas Beecham and Malcolm Sargent in 1932 as a riv ...

, conducting his own music, in 1940, the reviewer in ''The Manchester Guardian'' urged him to find a librettist and write a comic opera: "He ought to succeed greatly in that line. He is quick-witted, has a gift for lilting melody, deals in spicy and exhilarating harmony, and scores his music with a brilliancy that tells of experienced craftsmanship". Coates did not follow the paper's advice. His biographer Geoffrey Self suggests that he simply lacked the stamina, the aggressiveness or possibly the inclination to write for the musical theatre.

The few ventures Coates made into drama were for the cinema rather than the theatre. His orchestral phantasy ''Cinderella'' was first heard in the film '' A Symphony in Two Flats'', and he contributed the "Eighth Army March" to the 1941 war film ''Nine Men

The Nine Men was a council of citizens elected by the residents of New Netherland to advise its Director General Peter Stuyvesant on the governance of the colony. It replaced the previous body, the Eight Men, which itself had superseded th ...

'' and the "High Flight March" to '' High Flight'' (1957). As noted above, his most celebrated piece of cinema music, "The Dam Busters March

''The Dam Busters'' is the theme for the 1955 British war film '' The Dam Busters''. The musical composition, by Eric Coates, has become synonymous with both the film and the real Operation Chastise. ''The Dam Busters March'' remains a very pop ...

", was not written specially for the film. With these exceptions, Coates declined the offers from producers in Britain and the US who continually sought to secure his services. He realised that film music is liable to be cut, rearranged, or otherwise changed to meet the requirements of directors, and, mindful of such difficulties encountered by Arthur Bliss

Sir Arthur Edward Drummond Bliss (2 August 189127 March 1975) was an English composer and conductor.

Bliss's musical training was cut short by the First World War, in which he served with distinction in the army. In the post-war years he qui ...

in composing the score for ''Things to Come

''Things to Come'' is a 1936 British science fiction film produced by Alexander Korda, directed by William Cameron Menzies, and written by H. G. Wells. It is a loose adaptation of Wells' book '' The Shape of Things to Come''. The film stars Ra ...

'', he did not wish his music to be subjected to similar treatment.Self, p. 93

Notes, references and sources

Notes

References

Sources

* * * * * * * *External links

* * * *Biography at the Robert Farnon Society

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Coates, Eric 1886 births 1957 deaths 20th-century English classical composers 20th-century English male musicians 20th-century British violists Alumni of the Royal Academy of Music English classical violists English film score composers English light music composers English male film score composers Golders Green Crematorium People from Hucknall