Erasmus Darwin on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Erasmus Robert Darwin (12 December 173118 April 1802) was an English physician. One of the key thinkers of the

Darwin was born in 1731 at Elston Hall, Nottinghamshire, near

Darwin was born in 1731 at Elston Hall, Nottinghamshire, near

Erasmus Darwin House, Lichfield

* * *

Revolutionary Players website

in Ernst Krause, ''Erasmus Darwin'' (1879)

{{DEFAULTSORT:Darwin, Erasmus Proto-evolutionary biologists People of the Industrial Revolution 18th-century British botanists English entomologists Members of the Lunar Society of Birmingham Fellows of the Royal Society Darwin–Wedgwood family People from Lichfield People from Newark and Sherwood (district) 1731 births 1802 deaths Alumni of St John's College, Cambridge Alumni of the University of Edinburgh Paintings by Joseph Wright of Derby 18th-century English medical doctors English physiologists English naturalists English poets English abolitionists English inventors People from Breadsall People educated at Chesterfield Grammar School International members of the American Philosophical Society

Midlands Enlightenment

The Midlands Enlightenment, also known as the West Midlands Enlightenment or the Birmingham Enlightenment, was a scientific, economic, political, cultural and legal manifestation of the Age of Enlightenment that developed in Birmingham and the wid ...

, he was also a natural philosopher

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics, that is, nature and the physical universe, while ignoring any supernatural influence. It was dominant before the developme ...

, physiologist

Physiology (; ) is the scientific study of functions and mechanisms in a living system. As a subdiscipline of biology, physiology focuses on how organisms, organ systems, individual organs, cells, and biomolecules carry out chemical and ...

, slave-trade abolitionist, inventor, freemason

Freemasonry (sometimes spelled Free-Masonry) consists of fraternal groups that trace their origins to the medieval guilds of stonemasons. Freemasonry is the oldest secular fraternity in the world and among the oldest still-existing organizati ...

, and poet.

His poems included much natural history

Natural history is a domain of inquiry involving organisms, including animals, fungi, and plants, in their natural environment, leaning more towards observational than experimental methods of study. A person who studies natural history is cal ...

, including a statement of evolution

Evolution is the change in the heritable Phenotypic trait, characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. It occurs when evolutionary processes such as natural selection and genetic drift act on genetic variation, re ...

and the relatedness of all forms of life.

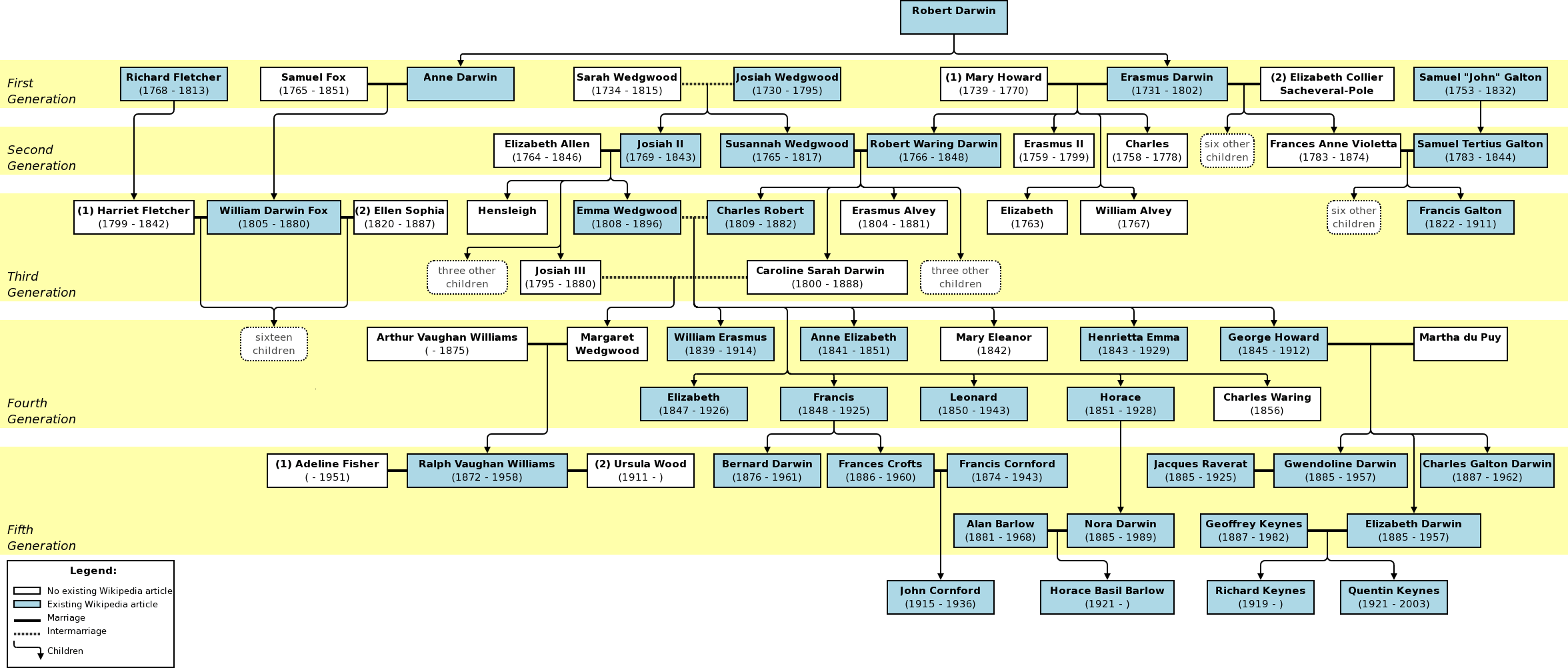

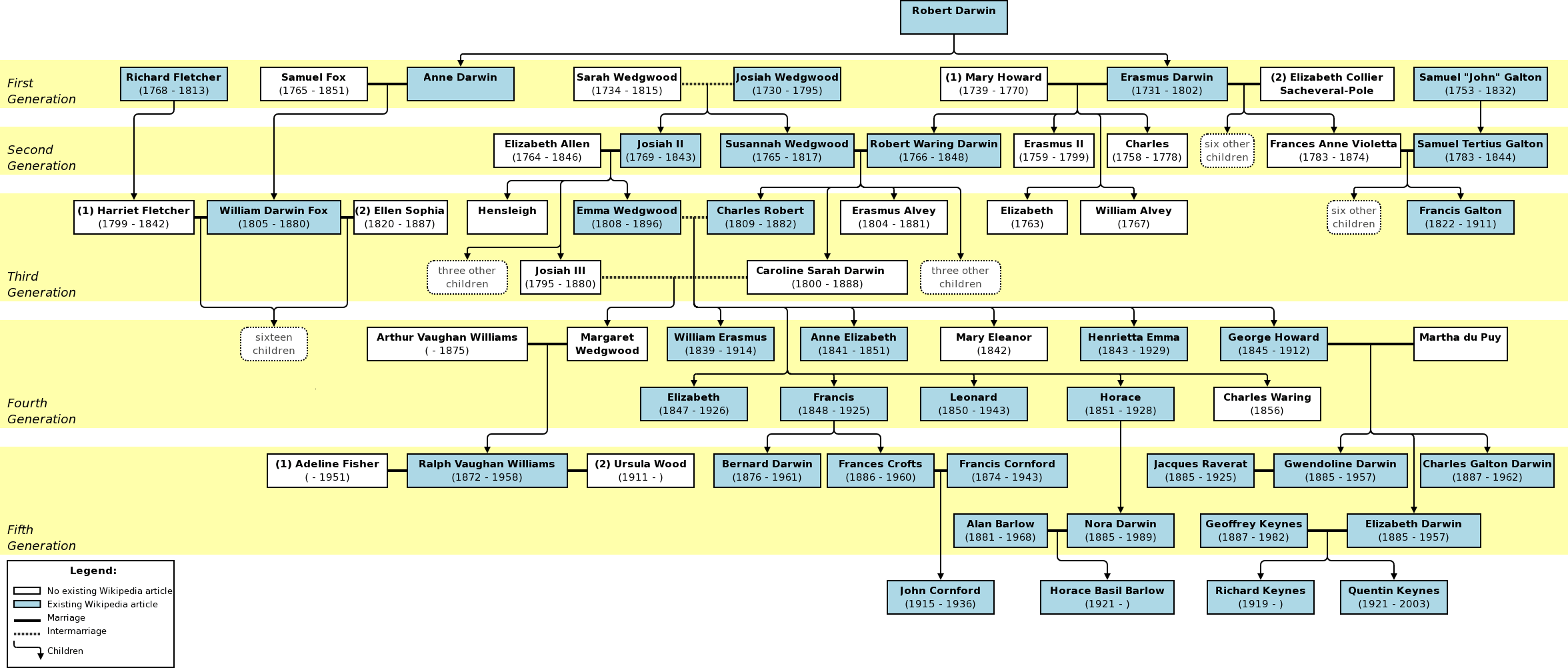

He was a member of the Darwin–Wedgwood family

The Darwin–Wedgwood family are members of two connected families, each noted for particular prominent 18th-century figures: Erasmus Darwin, a physician and natural philosopher, and Josiah Wedgwood FRS, a noted potter and founder of the epon ...

, which includes his grandsons Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English Natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci ...

and Francis Galton

Sir Francis Galton (; 16 February 1822 – 17 January 1911) was an English polymath and the originator of eugenics during the Victorian era; his ideas later became the basis of behavioural genetics.

Galton produced over 340 papers and b ...

. Darwin was a founding member of the Lunar Society of Birmingham

The Lunar Society of Birmingham was a British dinner club and informal learned society of prominent figures in the Midlands Enlightenment, including industrialists, natural philosophers and intellectuals, who met regularly between 1765 and 181 ...

, a discussion group of pioneering industrialists and natural philosophers.

He turned down an invitation from George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and King of Ireland, Ireland from 25 October 1760 until his death in 1820. The Acts of Union 1800 unified Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and ...

to become Physician to the King

Physician to the King (or Queen, as appropriate) is a title (as postnominals, KHP, QHP) held by physicians of the Medical Household of the Sovereign of the United Kingdom. Part of the Royal Household, the Medical Household includes physicians, ...

.

Early life and education

Darwin was born in 1731 at Elston Hall, Nottinghamshire, near

Darwin was born in 1731 at Elston Hall, Nottinghamshire, near Newark-on-Trent

Newark-on-Trent () or Newark is a market town and civil parish in the Newark and Sherwood district in Nottinghamshire, England. It is on the River Trent, and was historically a major inland port. The A1 road (Great Britain), A1 road bypasses th ...

, England, the youngest of seven children of Robert Darwin of Elston (1682–1754), a lawyer and physician, and his wife Elizabeth Hill (1702–97). The name Erasmus

Desiderius Erasmus Roterodamus ( ; ; 28 October c. 1466 – 12 July 1536), commonly known in English as Erasmus of Rotterdam or simply Erasmus, was a Dutch Christian humanist, Catholic priest and Catholic theology, theologian, educationalist ...

had been used by a number of his family and derives from his ancestor Erasmus Earle, Common Sergent of England under Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English statesman, politician and soldier, widely regarded as one of the most important figures in British history. He came to prominence during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, initially ...

. His siblings were:

* Robert Waring Darwin of Elston (17 October 1724 – 4 November 1816)

* Elizabeth Darwin (15 September 1725 – 8 April 1800)

* William Alvey Darwin (3 October 1726 – 7 October 1783)

* Anne Darwin (12 November 1727 – 3 August 1813)

* Susannah Darwin (10 April 1729 – 29 September 1789)

* Rev. John Darwin, rector of Elston (28 September 1730 – 24 May 1805)

He was educated at Chesterfield Grammar School, then later at St John's College, Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a List of cities in the United Kingdom, city and non-metropolitan district in the county of Cambridgeshire, England. It is the county town of Cambridgeshire and is located on the River Cam, north of London. As of the 2021 Unit ...

. He obtained his medical education at the University of Edinburgh Medical School

The University of Edinburgh Medical School (also known as Edinburgh Medical School) is the medical school of the University of Edinburgh in Scotland and the United Kingdom and part of the University of Edinburgh College of Medicine and Veterinar ...

.

Darwin settled in 1756 as a physician at Nottingham, but met with little success and so moved the following year to Lichfield

Lichfield () is a city status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and Civil parishes in England, civil parish in Staffordshire, England. Lichfield is situated south-east of the county town of Stafford, north-east of Walsall, north-west of ...

to try to establish a practice there. A few weeks after his arrival, using a novel course of treatment, he restored the health of a young fisherman whose death seemed inevitable. This ensured his success in the new locale. Darwin was a highly successful physician for more than fifty years in the Midlands

The Midlands is the central region of England, to the south of Northern England, to the north of southern England, to the east of Wales, and to the west of the North Sea. The Midlands comprises the ceremonial counties of Derbyshire, Herefor ...

. In 1761, he was elected to the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

. George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and King of Ireland, Ireland from 25 October 1760 until his death in 1820. The Acts of Union 1800 unified Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and ...

invited him to be Royal Physician

Royal may refer to:

People

* Royal (name), a list of people with either the surname or given name

* A member of a royal family or royalty

Places United States

* Royal, Arkansas, an unincorporated community

* Royal, Illinois, a village

* Royal, ...

, but Darwin declined.

Personal life

Darwin married twice and had 14 children, including two illegitimate daughters by an employee, and, possibly, at least one further illegitimate daughter. In 1757 he married Mary (Polly) Howard (1740–1770), the daughter of Charles Howard, a Lichfield solicitor. They had four sons and one daughter, two of whom (a son and a daughter) died in infancy: *Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English Natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci ...

(1758–1778), uncle of the naturalist

* Erasmus Darwin Jr (1759–1799)

* Elizabeth Darwin (1763, survived 4 months)

* Robert Waring Darwin

Robert Waring Darwin (30 May 1766 – 13 November 1848) was an English medical doctor who is today best known as the father of naturalist Charles Darwin. He was a member of the influential Darwin–Wedgwood family.

Biography

Darwin was born in ...

(1766–1848), father of the naturalist Charles Darwin

* William Alvey Darwin (1767, survived 19 days)

The first Mrs. Darwin died in 1770. A governess

A governess is a woman employed as a private tutor, who teaches and trains a child or children in their home. A governess often lives in the same residence as the children she is teaching; depending on terms of their employment, they may or ma ...

, Mary Parker, was hired to look after Robert. By late 1771, employer and employee had become intimately involved and together they had two illegitimate daughters:

* Susanna Parker (1772–1856)

* Mary Parker Jr (1774–1859)

Susanna and Mary Jr later established a boarding school

A boarding school is a school where pupils live within premises while being given formal instruction. The word "boarding" is used in the sense of "room and board", i.e. lodging and meals. They have existed for many centuries, and now extend acr ...

for girls. In 1782, Mary Sr (the governess) married Joseph Day (1745–1811), a Birmingham merchant, and moved away.

There was also a rumour that Darwin fathered another child, this time with a married woman. A Lucy Swift gave birth in 1771 to a baby, also named Lucy, who was christened a daughter of her mother and William Swift. It has been suggested that the father was really Darwin. However, it is more likely that this child was the legitimate daughter of Lamech Swift, at that time owner of the Derby Silk Mill and his wife Dorothy, who became a friend of the two Parker girls. Lucy Swift, later known as Lucy Hardcastle after her marriage, went on to be known as a botanist and teacher.

In 1775, Darwin met Elizabeth Pole, daughter of Charles Colyear, 2nd Earl of Portmore, and wife of Colonel Edward Pole (1718–1780); but as she was married, Darwin could only make his feelings known for her through poetry. When Edward Pole died, Darwin married Elizabeth and moved to her home, Radbourne Hall, west of Derby. The hall and village are these days known as Radbourne. In 1782, they moved to Full Street, Derby. They had four sons, one of whom died in infancy, and three daughters:

* Edward Darwin (1782–1829)

* Frances Ann Violetta Darwin (1783–1874), married Samuel Tertius Galton, was the mother of Francis Galton

Sir Francis Galton (; 16 February 1822 – 17 January 1911) was an English polymath and the originator of eugenics during the Victorian era; his ideas later became the basis of behavioural genetics.

Galton produced over 340 papers and b ...

* Emma Georgina Elizabeth Darwin (1784–1818)

* Sir Francis Sacheverel Darwin (1786–1859)

* Revd. John Darwin (1787–1818), rector of All Saints' Church, Elston

* Henry Darwin (1789–1790), died in infancy

* Harriet Darwin (1790–1825), married Admiral Thomas James Maling

Darwin's personal appearance is described in unflattering detail in his Biographical Memoirs, printed by the ''Monthly Magazine'' in 1802. Darwin, the description reads, "was of middle stature, in person gross and corpulent; his features were coarse, and his countenance heavy; if not wholly void of animation, it certainly was by no means expressive. The print of him, from a painting of Mr. Wright, is a good likeness. In his gait and dress he was rather clumsy and slovenly, and frequently walked with his tongue hanging out of his mouth."

Freemasonry

Darwin had been aFreemason

Freemasonry (sometimes spelled Free-Masonry) consists of fraternal groups that trace their origins to the medieval guilds of stonemasons. Freemasonry is the oldest secular fraternity in the world and among the oldest still-existing organizati ...

throughout his life, in the Time Immemorial Lodge of Cannongate Kilwinning, No. 2, of Scotland. Later on, Sir Francis Darwin, one of his sons, was made a Mason in Tyrian Lodge, No. 253, at Derby, in 1807 or 1808. His son Reginald was made a Mason in Tyrian Lodge in 1804. Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English Natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci ...

's name does not appear on the rolls of the Lodge but it is very possible that he, like Francis, was a Mason.

Death

Darwin died suddenly on 18 April 1802, weeks after having moved to Breadsall Priory, just north ofDerby

Derby ( ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and Unitary authorities of England, unitary authority area on the River Derwent, Derbyshire, River Derwent in Derbyshire, England. Derbyshire is named after Derby, which was its original co ...

. The Monthly Magazine of 1802, in its Biographical Memoirs of the Late Dr. Darwin, reports that "during the last few years, Dr. Darwin was much subject to inflammation in his breast and lungs; he had a very serious attack of this disease in the course of the last Spring, from which, after repeated bleedings, by himself and a surgeon, he with great difficulty recovered."

Darwin's death, the Biographical Memoirs continues, "is variously accounted for: it is supposed to have been caused by the cold fit of an inflammatory fever. Dr. Fox, of Derby, considers the disease which occasioned it to have been angina pectoris

Angina, also known as angina pectoris, is chest pain or pressure, usually caused by insufficient blood flow to the heart muscle (myocardium). It is most commonly a symptom of coronary artery disease.

Angina is typically the result of part ...

; but Dr. Garlicke, of the same place, thinks this opinion not sufficiently well founded. Whatever was the disease, it is not improbable, surely, that the fatal event was hastened by the violent fit of passion with which he was seized in the morning."

His body is buried in All Saints' Church, Breadsall.

Erasmus Darwin is commemorated on one of the Moonstones, a series of monuments in Birmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands (county), West Midlands, within the wider West Midlands (region), West Midlands region, in England. It is the Lis ...

.

Writings

Botanical works and the Lichfield Botanical Society

Darwin formed 'A Botanical Society, at Lichfield' almost always incorrectly named as the Lichfield Botanical Society (despite the name, composed of only three men, Erasmus Darwin, Sir Brooke Boothby and Mr John Jackson,proctor

Proctor (a variant of ''wikt:procurator, procurator'') is a person who takes charge of, or acts for, another.

The title is used in England and some other English-speaking countries in three principal contexts:

# In law, a proctor is a historica ...

of Lichfield Cathedral

Lichfield Cathedral, formally the Cathedral Church of Saint Mary and Saint Chad in Lichfield, is a Church of England cathedral in the city of Lichfield, England. It is the seat of the bishop of Lichfield and the principal church of the diocese ...

fl. 1740s–1790s. Also Bookseller and Printer in Lichfield. When Darwin left Lichfield in 1781, Jackson took over his botanical garden. His daughter, Miss Mary A(nn) Jackson of Lichfield (fl. 1830s–1840s), was a botanical illustrator, and author of ''Botanical Terms illustrated'' (1842) and ''Pictorial Flora'' (1840)) to translate the works of the Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus

Carl Linnaeus (23 May 1707 – 10 January 1778), also known after ennoblement in 1761 as Carl von Linné,#Blunt, Blunt (2004), p. 171. was a Swedish biologist and physician who formalised binomial nomenclature, the modern system of naming o ...

from Latin into English. This took seven years. The result was two publications: ''A System of Vegetables'' between 1783 and 1785, and ''The Families of Plants'' in 1787. In these volumes, Darwin coined many of the English names of plants that we use today.

Darwin then wrote '' The Loves of the Plants,'' a long poem, which was a popular rendering of Linnaeus' works. Darwin also wrote '' Economy of Vegetation'', and together the two were published as '' The Botanic Garden''. Among other writers he influenced were Anna Seward

Anna Seward (12 December 1742 ld style: 1 December 1742./ref>Often wrongly given as 1747.25 March 1809) was an English Romantic poet, often called the Swan of Lichfield. She benefited from her father's progressive views on female education.

L ...

and Maria Jacson.

''Zoonomia''

Darwin's most important scientific work, ''Zoonomia

''Zoonomia; or the Laws of Organic Life'' (1794–96) is a two-volume medical work by Erasmus Darwin dealing with pathology, anatomy, psychology, and the functioning of the body. Its primary framework is one of associationist psychophysiology

...

'' (1794–1796), contains a system of pathology

Pathology is the study of disease. The word ''pathology'' also refers to the study of disease in general, incorporating a wide range of biology research fields and medical practices. However, when used in the context of modern medical treatme ...

and a chapter on 'Generation

A generation is all of the people born and living at about the same time, regarded collectively. It also is "the average period, generally considered to be about 20–30 years, during which children are born and grow up, become adults, and b ...

'. In the latter, he anticipated some of the views of Jean-Baptiste Lamarck

Jean-Baptiste Pierre Antoine de Monet, chevalier de Lamarck (1 August 1744 – 18 December 1829), often known simply as Lamarck (; ), was a French naturalist, biologist, academic, and soldier. He was an early proponent of the idea that biologi ...

, which foreshadowed the modern theory of evolution

Evolution is the change in the heritable Phenotypic trait, characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. It occurs when evolutionary processes such as natural selection and genetic drift act on genetic variation, re ...

. Erasmus Darwin's works were read and commented on by his grandson Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English Natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci ...

the naturalist. Erasmus Darwin based his theories on David Hartley's psychological theory of associationism

Associationism is the idea that mental processes operate by the association of one mental state with its successor states. It holds that all mental processes are made up of discrete psychological elements and their combinations, which are believe ...

. The essence of his views is contained in the following passage, which he follows up with the conclusion that one and the same kind of living filament is and has been the cause of all organic life:

Would it be too bold to imagine, that in the great length of time, since the earth began to exist, perhaps millions of ages before the commencement of the history of mankind, would it be too bold to imagine, that all warm-blooded animals have arisen from one living filament, which THE GREAT FIRST CAUSE endued with animality, with the power of acquiring new parts, attended with new propensities, directed by irritations, sensations, volitions, and associations; and thus possessing the faculty of continuing to improve by its own inherent activity, and of delivering down those improvements by generation to its posterity, world without end!Erasmus Darwin also anticipated survival of the fittest in ''Zoönomia'' mainly when writing about the "three great objects of desire" for every organism: "lust, hunger, and security." A similar "survival of the fittest" view in ''Zoönomia'' is Erasmus' view on how a species "should" propagate itself. Erasmus' idea that "the strongest and most active animal should propagate the species, which should thence become improved". Today, this is called the theory of

survival of the fittest

"Survival of the fittest" is a phrase that originated from Darwinian evolutionary theory as a way of describing the mechanism of natural selection. The biological concept of fitness is defined as reproductive success. In Darwinian terms, th ...

. His grandson Charles Darwin posited the different and fuller theory of natural selection. Charles' theory was that natural selection is the inheritance of changed genetic characteristics that are better adaptations to the environment; these are not necessarily based in "strength" and "activity", which themselves ironically can lead to the overpopulation that results in natural selection yielding nonsurvivors of genetic traits.

Erasmus Darwin was familiar with the earlier proto-evolutionary thinking of James Burnett, Lord Monboddo, and cited him in his 1803 work ''Temple of Nature.''

Poem on evolution

Erasmus Darwin offered the first glimpse of his theory of evolution, obliquely, in a question at the end of a long footnote to his popular poem ''The Loves of the Plants'' (1789), which was republished throughout the 1790s in several editions as '' The Botanic Garden''. His poetic concept was to anthropomorphise thestamen

The stamen (: stamina or stamens) is a part consisting of the male reproductive organs of a flower. Collectively, the stamens form the androecium., p. 10

Morphology and terminology

A stamen typically consists of a stalk called the filament ...

(male) and pistil

Gynoecium (; ; : gynoecia) is most commonly used as a collective term for the parts of a flower that produce ovules and ultimately develop into the fruit and seeds. The gynoecium is the innermost whorl (botany), whorl of a flower; it consists ...

(female) sexual organs, as bride and groom. In this stanza on the flower Curcuma (also Flax and Turmeric) the "youths" are infertile, and he devotes the footnote to other examples of neutered organs in flowers, insect castes, and finally associates this more broadly with many popular and well-known cases of vestigial organs (male nipples, the third and fourth wings of flies, etc.)

Darwin's final long poem, ''The Temple of Nature'', was published posthumously in 1803. The poem was originally titled ''The Origin of Society''. It is considered his best poetic work. It centres on his own conception of evolution

Evolution is the change in the heritable Phenotypic trait, characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. It occurs when evolutionary processes such as natural selection and genetic drift act on genetic variation, re ...

. The poem traces the progression of life from micro-organisms to civilised society. The poem contains a passage that describes the struggle for existence

The concept of the struggle for existence (or struggle for life) concerns the competition or battle for resources needed to live. It can refer to human society, or to organisms in nature. The concept is ancient, and the term ''struggle for existe ...

.

His poetry was admired by Wordsworth

William Wordsworth (7 April 177023 April 1850) was an English Romantic poet who, with Samuel Taylor Coleridge, helped to launch the Romantic Age in English literature with their joint publication '' Lyrical Ballads'' (1798).

Wordsworth's ...

, while Coleridge was intensely critical, writing, "I absolutely nauseate Darwin's poem".

It often made reference to his interests in science; for example botany and steam engine

A steam engine is a heat engine that performs Work (physics), mechanical work using steam as its working fluid. The steam engine uses the force produced by steam pressure to push a piston back and forth inside a Cylinder (locomotive), cyl ...

s.

Education of women

The last two leaves of Darwin's ''A plan for the conduct of female education in boarding schools'' (1797) contain a book list, an apology for the work, and an advert for "Miss Parkers School". The school advertised on the last page is the one he set up inAshbourne, Derbyshire

Ashbourne is a market town in the Derbyshire Dales district in Derbyshire, England. Its population was measured at 8,377 in the 2011 census and was estimated to have grown to 9,163 by 2019. It has many historical buildings and independent sho ...

, for his two illegitimate children, Susanna and Mary.

Darwin regretted that a good education had not been generally available to women in Britain in his time, and drew on the ideas of Locke, Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (, ; ; 28 June 1712 – 2 July 1778) was a Genevan philosopher ('' philosophe''), writer, and composer. His political philosophy influenced the progress of the Age of Enlightenment throughout Europe, as well as aspects ...

, and Genlis in organising his thoughts. Addressing the education of middle-class girls, Darwin argued that amorous romance novels were inappropriate and that they should seek simplicity in dress. He contends that young women should be educated in schools, rather than privately at home, and learn appropriate subjects. These subjects include physiognomy, physical exercise, botany, chemistry, mineralogy, and experimental philosophy. They should familiarise themselves with arts and manufactures through visits to sites like Coalbrookdale

Coalbrookdale is a town in the Ironbridge Gorge and the Telford and Wrekin borough of Shropshire, England, containing a settlement of great significance in the history of iron ore smelting. It lies within the civil parish called The Gorge, Shro ...

, and Wedgwood's potteries; they should learn how to handle money, and study modern languages. Darwin's educational philosophy took the view that men and women should have different capabilities, skills, interests, and spheres of action, where the woman's education was designed to support and serve male accomplishment and financial reward, and to relieve him of daily responsibility for children and the chores of life. In the context of the times, this program may be read as a modernising influence in the sense that the woman was at least to learn about the "man's world", although not be allowed to participate in it. The text was written seven years after A Vindication of the Rights of Woman

''A Vindication of the Rights of Woman: with Strictures on Political and Moral Subjects'' , is a 1792 feminist essay written by British philosopher and women's rights advocate Mary Wollstonecraft (1759–1797), and is one of the earliest work ...

by Mary Wollstonecraft

Mary Wollstonecraft ( , ; 27 April 175910 September 1797) was an English writer and philosopher best known for her advocacy of women's rights. Until the late 20th century, Wollstonecraft's life, which encompassed several unconventional ...

, which has the central argument that women should be educated in a rational manner to give them the opportunity to contribute to society.

Some women of Darwin's era were receiving more substantial education and participating in the broader world. An example is Susanna Wright, who was raised in Lancashire and became an American colonist associated with the Midlands Enlightenment. It is not known whether Darwin and Wright knew each other, although they definitely knew many people in common. Other women who received substantial education and who participated in the broader world (albeit sometimes anonymously) whom Darwin definitely knew were Maria Jacson and Anna Seward

Anna Seward (12 December 1742 ld style: 1 December 1742./ref>Often wrongly given as 1747.25 March 1809) was an English Romantic poet, often called the Swan of Lichfield. She benefited from her father's progressive views on female education.

L ...

.

Lunar Society

These dates indicate the year in which Darwin became friends with these people, who, in turn, became members of theLunar Society

The Lunar Society of Birmingham was a British dinner club and informal learned society of prominent figures in the Midlands Enlightenment, including industrialists, natural philosophy, natural philosophers and intellectuals, who met regularly b ...

. The Lunar Society existed from 1765 to 1813.

Before 1765:

* Matthew Boulton

Matthew Boulton ( ; 3 September 172817 August 1809) was an English businessman, inventor, mechanical engineer, and silversmith. He was a business partner of the Scottish engineer James Watt. In the final quarter of the 18th century, the par ...

, originally a buckle maker in Birmingham

* John Whitehurst of Derby, maker of clocks and scientific instruments, pioneer of geology

After 1765:

* Josiah Wedgwood

Josiah Wedgwood (12 July 1730 – 3 January 1795) was an English potter, entrepreneur and abolitionist. Founding the Wedgwood company in 1759, he developed improved pottery bodies by systematic experimentation, and was the leader in the indu ...

, potter 1765

* Dr. William Small, 1765, man of science, formerly Professor of Natural Philosophy at the College of William and Mary

The College of William & Mary (abbreviated as W&M) is a public research university in Williamsburg, Virginia, United States. Founded in 1693 under a royal charter issued by King William III and Queen Mary II, it is the second-oldest instit ...

, where Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (, 1743July 4, 1826) was an American Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was the primary author of the United States Declaration of Indepe ...

was an appreciative pupil

* Richard Lovell Edgeworth

Richard Lovell Edgeworth (31 May 1744 – 13 June 1817) was an Anglo-Irish politician, writer and inventor. He had 22 children.

Biography

Edgeworth was born in Pierrepont Street, Bath, England, son of Richard Edgeworth senior, and great ...

, 1766, inventor

* James Watt

James Watt (; 30 January 1736 (19 January 1736 OS) – 25 August 1819) was a Scottish inventor, mechanical engineer, and chemist who improved on Thomas Newcomen's 1712 Newcomen steam engine with his Watt steam engine in 1776, which was f ...

, 1767, improver of steam engine

* James Keir

James Keir FRS (20 September 1735 – 11 October 1820) was a Scottish chemist, geologist, industrialist, and inventor, and an important member of the Lunar Society of Birmingham.

Life and work

Keir was born in Stirlingshire, Scotland, in 1 ...

, 1767, pioneer of the chemical industry

* Thomas Day, 1768, eccentric and author

* Dr. William Withering, 1775, the death of Dr. Small left an opening for a physician in the group.

* Joseph Priestley

Joseph Priestley (; 24 March 1733 – 6 February 1804) was an English chemist, Unitarian, Natural philosophy, natural philosopher, English Separatist, separatist theologian, Linguist, grammarian, multi-subject educator and Classical libera ...

, 1780, experimental chemist and discoverer of many substances.

* Samuel Galton, 1782, a Quaker gunmaker with a taste for science, took Darwin's place after Darwin moved to Derby.

Darwin also established a lifelong friendship with Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin (April 17, 1790) was an American polymath: a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher and Political philosophy, political philosopher.#britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the m ...

, who shared Darwin's support for the American and French revolutions. The Lunar Society was instrumental as an intellectual driving force behind England's Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution, sometimes divided into the First Industrial Revolution and Second Industrial Revolution, was a transitional period of the global economy toward more widespread, efficient and stable manufacturing processes, succee ...

.

The members of the Lunar Society, and especially Darwin, opposed the slave trade. He attacked it in ''The Botanic Garden'' (1789–1791), and in ''The Loves of Plants'' (1789), ''The Economy of Vegetation'' (1791), and the ''Phytologia'' (1800).

Other activities

In 1761, Darwin was elected a fellow of theRoyal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

.

In addition to the Lunar Society, Erasmus Darwin belonged to the influential Derby Philosophical Society, as did his brother-in-law Samuel Fox (see family tree below). He experimented with the use of air and gases to alleviate infections and cancers in patients. A Pneumatic Institution was established at Clifton in 1799 for clinically testing these ideas. He conducted research into the formation of clouds, on which he published in 1788. He also inspired Robert Weldon's Somerset Coal Canal

The Somerset Coal Canal (originally known as the Somersetshire Coal Canal) was a narrow canal in England, built around 1800. Its route began in basins at Paulton and Timsbury, ran to nearby Camerton, over two aqueducts at Dunkerton, throug ...

caisson lock.

In 1792, Darwin was elected as a member to the American Philosophical Society

The American Philosophical Society (APS) is an American scholarly organization and learned society founded in 1743 in Philadelphia that promotes knowledge in the humanities and natural sciences through research, professional meetings, publicat ...

in Philadelphia

Philadelphia ( ), colloquially referred to as Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania, most populous city in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania and the List of United States cities by population, sixth-most populous city in the Unit ...

.

Percy Bysshe Shelley

Percy Bysshe Shelley ( ; 4 August 1792 – 8 July 1822) was an English writer who is considered one of the major English Romantic poets. A radical in his poetry as well as in his political and social views, Shelley did not achieve fame durin ...

specifically mentions Darwin in the first sentence of the 1818 Preface to ''Frankenstein

''Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus'' is an 1818 Gothic novel written by English author Mary Shelley. ''Frankenstein'' tells the story of Victor Frankenstein, a young scientist who creates a Sapience, sapient Frankenstein's monster, crea ...

'' to support his contention that the creation of life is possible. His wife Mary Shelley

Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley ( , ; ; 30 August 1797 – 1 February 1851) was an English novelist who wrote the Gothic novel ''Frankenstein, Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus'' (1818), which is considered an History of science fiction# ...

in her introduction to the 1831 edition of ''Frankenstein

''Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus'' is an 1818 Gothic novel written by English author Mary Shelley. ''Frankenstein'' tells the story of Victor Frankenstein, a young scientist who creates a Sapience, sapient Frankenstein's monster, crea ...

'' wrote that she overheard her husband talk about Darwin's experiments with Lord Byron

George Gordon Byron, 6th Baron Byron (22 January 1788 – 19 April 1824) was an English poet. He is one of the major figures of the Romantic movement, and is regarded as being among the greatest poets of the United Kingdom. Among his best-kno ...

about unspecified "experiments of Dr. Darwin" that led to the idea for the novel.

Cosmological speculation

Contemporary literature dates the cosmological theories of theBig Bang

The Big Bang is a physical theory that describes how the universe expanded from an initial state of high density and temperature. Various cosmological models based on the Big Bang concept explain a broad range of phenomena, including th ...

and Big Crunch

The Big Crunch is a hypothetical scenario for the ultimate fate of the universe, in which the expansion of the universe eventually reverses and the universe recollapses, ultimately causing the cosmic scale factor to reach absolute zero, an eve ...

to the 19th and 20th centuries. However, Erasmus Darwin had speculated on these sorts of events in ''The Botanic Garden, A Poem in Two Parts: Part 1, The Economy of Vegetation, 1791'':

Inventions

Darwin was the inventor of several devices, though he did not patent any: he believed this would damage his reputation as a doctor. He encouraged his friends to patent their own modifications of his designs. * A horizontalwindmill

A windmill is a machine operated by the force of wind acting on vanes or sails to mill grain (gristmills), pump water, generate electricity, or drive other machinery.

Windmills were used throughout the high medieval and early modern period ...

, which he designed for Josiah Wedgwood

Josiah Wedgwood (12 July 1730 – 3 January 1795) was an English potter, entrepreneur and abolitionist. Founding the Wedgwood company in 1759, he developed improved pottery bodies by systematic experimentation, and was the leader in the indu ...

(who would be Charles Darwin's other grandfather, see family tree below).

* A carriage

A carriage is a two- or four-wheeled horse-drawn vehicle for passengers. In Europe they were a common mode of transport for the wealthy during the Roman Empire, and then again from around 1600 until they were replaced by the motor car around 1 ...

that would not tip over (1766).

* A steering mechanism for his carriage

A carriage is a two- or four-wheeled horse-drawn vehicle for passengers. In Europe they were a common mode of transport for the wealthy during the Roman Empire, and then again from around 1600 until they were replaced by the motor car around 1 ...

, known today as the Ackermann linkage, that would be adopted by cars 130 years later (1759).

* A speaking machine, which was a mechanical larynx made of wood, silk, and leather and pronounced several sounds so well 'as to deceive all who heard it unseen' (at Clifton in 1799).

* A canal lift for barges.

* A minute artificial bird.

* A copying

Copying is the duplication of information or an wiktionary:artifact, artifact based on an instance of that information or artifact, and not using the process that originally generated it. With Analog device, analog forms of information, copying is ...

machine (1778).

* A variety of weather monitoring machines.

Rocket engine

In notes dating to 1779, Darwin made a sketch of a simple hydrogen-oxygenrocket engine

A rocket engine is a reaction engine, producing thrust in accordance with Newton's third law by ejecting reaction mass rearward, usually a high-speed Jet (fluid), jet of high-temperature gas produced by the combustion of rocket propellants stor ...

, with gas tanks connected by plumbing and pumps to an elongated combustion chamber and expansion nozzle, a concept not to be seen again until one century later.

Major publications

* Erasmus Darwin, ''A Botanical Society at Lichfield. A System of Vegetables, according to their classes, orders... translated from the 13th edition of Linnaeus' Systema Vegetabiliium''. 2 vols., 1783, Lichfield, J. Jackson, for Leigh and Sotheby, London. * Erasmus Darwin, ''A Botanical Society at Lichfield. The Families of Plants with their natural characters...Translated from the last edition of Linnaeus' Genera Plantarum''. 1787, Lichfield, J. Jackson, for J. Johnson, London. * Erasmus Darwin, '' The Botanic Garden, Part I, The Economy of Vegetation''. 1791 London, J. Johnson. * Part II, ''The Loves of the Plants''. 1789, London, J. Johnson. * Erasmus Darwin, ''Zoonomia

''Zoonomia; or the Laws of Organic Life'' (1794–96) is a two-volume medical work by Erasmus Darwin dealing with pathology, anatomy, psychology, and the functioning of the body. Its primary framework is one of associationist psychophysiology

...

; or, The Laws of Organic Life'', 1794, Part I. London, J. Johnson.

* Part I–III. 1796, London, J. Johnson.

* (last two leaves contain a book list, an apology for the work, and an advert for "Miss Parkers School")

* Erasmus Darwin, ''Phytologia; or, The Philosophy of Agriculture and Gardening''. 1800, London, J. Johnson.

* Erasmus Darwin, ''The Temple of Nature; or, The Origin of Society''. 1803, London, J. Johnson.

Family tree

Commemoration

Erasmus Darwin House, his home inLichfield

Lichfield () is a city status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and Civil parishes in England, civil parish in Staffordshire, England. Lichfield is situated south-east of the county town of Stafford, north-east of Walsall, north-west of ...

, Staffordshire, is a museum dedicated to him and his life's work. A secondary school at Burntwood, near Lichfield, was renamed Erasmus Darwin Academy in 2011.

A science building on the Clifton campus of Nottingham Trent University

Nottingham Trent University (NTU) is a public research university located in Nottingham, England. Its origins date back to 1843 with the establishment of the Nottingham School of Design, Nottingham Government School of Design, which still opera ...

is named after him.

In fiction

*Charles Sheffield

Charles Sheffield (25 June 1935 – 2 November 2002), was an English-born mathematician, physicist, and science-fiction writer who served as a President of the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America and of the American Astronautical ...

, an author noted largely for hard science fiction

Hard science fiction is a category of science fiction characterized by concern for scientific accuracy and logic. The term was first used in print in 1957 by P. Schuyler Miller in a review of John W. Campbell's ''Islands of Space'' in the Novemb ...

, wrote a number of stories featuring Darwin in a role similar to that of Sherlock Holmes

Sherlock Holmes () is a Detective fiction, fictional detective created by British author Arthur Conan Doyle. Referring to himself as a "Private investigator, consulting detective" in his stories, Holmes is known for his proficiency with obser ...

. These stories were collected in a book, ''The Amazing Dr. Darwin''.

* The forgetting of Erasmus' designs for a rocket is a major plot point in Stephen Baxter's tale of alternate universes, ''Manifold: Origin''.

* Phrases from Darwin's poem '' The Botanic Garden'' are used as chapter headings in ''The Pornographer of Vienna'' by Lewis Crofts.

* Darwin appears as a character in Sergey Lukyanenko

Sergei Vasilyevich Lukyanenko (, ; born 11 April 1968) is a Russian science fiction and fantasy author, writing in Russian language, Russian. His works often feature intense Action fiction, action-packed plots, interwoven with the Ethical dilemma ...

's novel '' New Watch'' as a Dark Other, and a prophet living in Regent's Park Estate.

See also

* Evolutionary ideas of the Renaissance and Enlightenment *History of evolutionary thought

Evolutionary thought, the recognition that species change over time and the perceived understanding of how such processes work, has roots in antiquity. With the beginnings of modern Taxonomy (biology), biological taxonomy in the late 17th cent ...

Notes

References

Sources

* * * * * * * *Biographies and criticism

* * * King-Hele, Desmond. 1963. ''Doctor Darwin''. Scribner's, N.Y. * King-Hele, Desmond. 1977. ''Doctor of Revolution: the life and genius of Erasmus Darwin''. Faber, London. * King-Hele, Desmond. 1999. ''Erasmus Darwin: a life of unequalled achievement'' Giles de la Mare Publishers. * King-Hele, Desmond (ed) 2002. ''Charles Darwin's 'The Life of Erasmus Darwin' '' Cambridge University Press. * Krause, Ernst 1879. ''Erasmus Darwin, with a preliminary notice by Charles Darwin''. Murray, London. * Pearson, Hesketh. 1930. ''Doctor Darwin''. Dent, London. * Porter, Roy, 1989. 'Erasmus Darwin: doctor of evolution?' in 'History, Humanity and Evolution: Essays for John C. Greene, ed. James R. Moore. * * * *Further reading

* Darwin, Erasmus. (1794–96). ''Zoonomia

''Zoonomia; or the Laws of Organic Life'' (1794–96) is a two-volume medical work by Erasmus Darwin dealing with pathology, anatomy, psychology, and the functioning of the body. Its primary framework is one of associationist psychophysiology

...

''. J. Johnson (reissued by Cambridge University Press

Cambridge University Press was the university press of the University of Cambridge. Granted a letters patent by King Henry VIII in 1534, it was the oldest university press in the world. Cambridge University Press merged with Cambridge Assessme ...

, 2009; )

*

External links

Erasmus Darwin House, Lichfield

* * *

Revolutionary Players website

in Ernst Krause, ''Erasmus Darwin'' (1879)

{{DEFAULTSORT:Darwin, Erasmus Proto-evolutionary biologists People of the Industrial Revolution 18th-century British botanists English entomologists Members of the Lunar Society of Birmingham Fellows of the Royal Society Darwin–Wedgwood family People from Lichfield People from Newark and Sherwood (district) 1731 births 1802 deaths Alumni of St John's College, Cambridge Alumni of the University of Edinburgh Paintings by Joseph Wright of Derby 18th-century English medical doctors English physiologists English naturalists English poets English abolitionists English inventors People from Breadsall People educated at Chesterfield Grammar School International members of the American Philosophical Society