English Protestant on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The English Reformation began in 16th-century England when the

The publication of

The publication of

Henry claimed that this lack of a male heir was because his marriage was "blighted in the eyes of God". Catherine had been his late brother's wife, and it was therefore against biblical teachings for Henry to have married her ( Leviticus 20:21); a special dispensation from

Henry claimed that this lack of a male heir was because his marriage was "blighted in the eyes of God". Catherine had been his late brother's wife, and it was therefore against biblical teachings for Henry to have married her ( Leviticus 20:21); a special dispensation from

For Cromwell and Cranmer, a step in the Protestant agenda was attacking

For Cromwell and Cranmer, a step in the Protestant agenda was attacking

When Henry died in 1547, his nine-year-old son,

When Henry died in 1547, his nine-year-old son,

The historian Eamon Duffy writes that the Marian religious "programme was not one of reaction but of creative reconstruction" absorbing whatever was considered positive in the reforms of Henry VIII and Edward VI. The result was "subtly but distinctively different from the Catholicism of the 1520s." According to historian Christopher Haigh, the Catholicism taking shape in Mary's reign "reflected the mature Erasmian Catholicism" of its leading clerics, who were all educated in the 1520s and 1530s. Marian church literature, church

The historian Eamon Duffy writes that the Marian religious "programme was not one of reaction but of creative reconstruction" absorbing whatever was considered positive in the reforms of Henry VIII and Edward VI. The result was "subtly but distinctively different from the Catholicism of the 1520s." According to historian Christopher Haigh, the Catholicism taking shape in Mary's reign "reflected the mature Erasmian Catholicism" of its leading clerics, who were all educated in the 1520s and 1530s. Marian church literature, church  Mary did what she could to restore church finances and land taken in the reigns of her father and brother. In 1555, she returned to the church the First Fruits and Tenths revenue, but with these new funds came the responsibility of paying the pensions of ex-religious. She restored six religious houses with her own money, notably

Mary did what she could to restore church finances and land taken in the reigns of her father and brother. In 1555, she returned to the church the First Fruits and Tenths revenue, but with these new funds came the responsibility of paying the pensions of ex-religious. She restored six religious houses with her own money, notably

Protestants who refused to conform remained an obstacle to Catholic plans. Around 800 Protestants fled England to find safety in Protestant areas of Germany and Switzerland, establishing networks of independent congregations. Safe from persecution, these Marian exiles carried on a propaganda campaign against Catholicism and the Queen's Spanish marriage, sometimes calling for rebellion. Those who remained in England were forced to practise their faith in secret and meet in underground congregations.

In 1555, the initial reconciling tone of the regime began to harden with the Revival of the Heresy Acts, revival of the English late medieval civil heresy laws, which authorised capital punishment as a penalty for heresy. The persecution of heretics was uncoordinatedŌĆösometimes arrests were ordered by the Privy Council, others by bishops, and others by lay magistrates. Protestants brought attention to themselves usually due to some act of dissent, such as denouncing the Mass or refusing to receive the sacrament. A particularly violent act of protest was William Flower (martyr), William Flower's stabbing of a priest during Mass on Easter Sunday, 14 April 1555. Individuals accused of heresy were examined by a church official and, if heresy was found, given the choice between death and signing a

Protestants who refused to conform remained an obstacle to Catholic plans. Around 800 Protestants fled England to find safety in Protestant areas of Germany and Switzerland, establishing networks of independent congregations. Safe from persecution, these Marian exiles carried on a propaganda campaign against Catholicism and the Queen's Spanish marriage, sometimes calling for rebellion. Those who remained in England were forced to practise their faith in secret and meet in underground congregations.

In 1555, the initial reconciling tone of the regime began to harden with the Revival of the Heresy Acts, revival of the English late medieval civil heresy laws, which authorised capital punishment as a penalty for heresy. The persecution of heretics was uncoordinatedŌĆösometimes arrests were ordered by the Privy Council, others by bishops, and others by lay magistrates. Protestants brought attention to themselves usually due to some act of dissent, such as denouncing the Mass or refusing to receive the sacrament. A particularly violent act of protest was William Flower (martyr), William Flower's stabbing of a priest during Mass on Easter Sunday, 14 April 1555. Individuals accused of heresy were examined by a church official and, if heresy was found, given the choice between death and signing a

Elizabeth I of England, Elizabeth I inherited a kingdom in which a majority of people, especially the political elite, were religiously conservative, and England's main ally was Catholic Spain. For these reasons, the proclamation announcing her accession forbade any "breach, alteration, or change of any order or usage presently established within this our realm". This was only temporary. The new Queen was Protestant, though a conservative one. She also filled her new government with Protestants. The Queen's Secretary of State (England), principal secretary was Sir William Cecil, a moderate Protestant. Her Privy Council was filled with former Edwardian politicians, and only Protestants preached at Royal court, Court.

In 1558, Parliament passed the Act of Supremacy 1558, Act of Supremacy, which re-established the Church of England's independence from Rome and conferred on Elizabeth the title of Supreme Governor of the Church of England. The Act of Uniformity 1559, Act of Uniformity of 1559 authorised the Book of Common Prayer (1559), 1559 ''Book of Common Prayer'', which was a revised version of the 1552 Prayer Book from Edward's reign. Some modifications were made to appeal to Catholics and Lutherans, including giving individuals greater latitude concerning belief in the real presence and Ornaments Rubric, authorising the use of traditional priestly vestments. In 1571, the Thirty-Nine Articles were adopted as a confessional statement for the church, and a Book of Homilies was issued outlining the church's reformed theology in greater detail.

The Elizabethan Settlement established a church that was Reformed in doctrine but that preserved certain characteristics of medieval Catholicism, such as

Elizabeth I of England, Elizabeth I inherited a kingdom in which a majority of people, especially the political elite, were religiously conservative, and England's main ally was Catholic Spain. For these reasons, the proclamation announcing her accession forbade any "breach, alteration, or change of any order or usage presently established within this our realm". This was only temporary. The new Queen was Protestant, though a conservative one. She also filled her new government with Protestants. The Queen's Secretary of State (England), principal secretary was Sir William Cecil, a moderate Protestant. Her Privy Council was filled with former Edwardian politicians, and only Protestants preached at Royal court, Court.

In 1558, Parliament passed the Act of Supremacy 1558, Act of Supremacy, which re-established the Church of England's independence from Rome and conferred on Elizabeth the title of Supreme Governor of the Church of England. The Act of Uniformity 1559, Act of Uniformity of 1559 authorised the Book of Common Prayer (1559), 1559 ''Book of Common Prayer'', which was a revised version of the 1552 Prayer Book from Edward's reign. Some modifications were made to appeal to Catholics and Lutherans, including giving individuals greater latitude concerning belief in the real presence and Ornaments Rubric, authorising the use of traditional priestly vestments. In 1571, the Thirty-Nine Articles were adopted as a confessional statement for the church, and a Book of Homilies was issued outlining the church's reformed theology in greater detail.

The Elizabethan Settlement established a church that was Reformed in doctrine but that preserved certain characteristics of medieval Catholicism, such as

Traditionally, historians have dated the end of the English Reformation to Elizabeth's religious settlement. There are scholars who advocate for a "Long Reformation" that continued into the 17th and 18th centuries.

During the early

Traditionally, historians have dated the end of the English Reformation to Elizabeth's religious settlement. There are scholars who advocate for a "Long Reformation" that continued into the 17th and 18th centuries.

During the early

excerpt

* * * *

Volume IVolume I, Part IIVolume IIVolume II, Part IIVolume IIIVolume III, Part II

* ''Ecclesiastical Memorials, Relating Chiefly to Religion, and the Reformation of It, and the Emergencies of the Church of England, Under King Henry VIII, King Edward VI, and Queen Mary I'' by John Strype (Clarendon Press, 1822)

Vol. I, Pt. IVol. I, Pt. IIVol. II, Pt. IVol. II, Pt. IIVol. III, Pt. IVol. III, Pt. II

* ''Annals of the Reformation and Establishment of Religion, and Other Various Occurrences in the Church of England, During Queen Elizabeth's Happy Reign'' by John Strype (1824 ed.)

Vol. I, Pt. IVol. I, Pt. IIVol. II, Pt. IVol. II., Pt. IIVol. III, Pt. IVol. III, Pt. IIVol. IV

Ćölinks to primary sources.

Ćölinks to primary sources. {{Anglican Liturgy, state=collapsed English Reformation, Anglicanism Protestantism in England Anti-Catholicism in England Anti-Catholicism in Wales Religion and politics History of Catholicism in England History of the Church of England

Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the State religion#State churches, established List of Christian denominations, Christian church in England and the Crown Dependencies. It is the mother church of the Anglicanism, Anglican Christian tradition, ...

broke away first from the authority of the pope

The pope is the bishop of Rome and the Head of the Church#Catholic Church, visible head of the worldwide Catholic Church. He is also known as the supreme pontiff, Roman pontiff, or sovereign pontiff. From the 8th century until 1870, the po ...

and bishops over the King and then from some doctrines and practices of the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

. These events were part of the wider European Reformation

The Reformation, also known as the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation, was a time of major Theology, theological movement in Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the p ...

: various religious and political movements that affected both the practice of Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion, which states that Jesus in Christianity, Jesus is the Son of God (Christianity), Son of God and Resurrection of Jesus, rose from the dead after his Crucifixion of Jesus, crucifixion, whose ...

in Western

Western may refer to:

Places

*Western, Nebraska, a village in the US

*Western, New York, a town in the US

*Western Creek, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western Junction, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western world, countries that id ...

and Central Europe

Central Europe is a geographical region of Europe between Eastern Europe, Eastern, Southern Europe, Southern, Western Europe, Western and Northern Europe, Northern Europe. Central Europe is known for its cultural diversity; however, countries in ...

and relations between church and state.

The English Reformation began as more of a political affair than a theological dispute. In 1527 Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is known for his Wives of Henry VIII, six marriages and his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. ...

requested an annulment of his marriage, but Pope Clement VII

Pope Clement VII (; ; born Giulio di Giuliano de' Medici; 26 May 1478 ŌĆō 25 September 1534) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 19 November 1523 to his death on 25 September 1534. Deemed "the most unfortunate o ...

refused. In response, the Reformation Parliament (1529ŌĆō1536) passed laws abolishing papal authority in England and declared Henry to be head of the Church of England. Final authority in doctrinal disputes now rested with the monarch. Though a religious traditionalist himself, Henry relied on Protestants to support and implement his religious agenda.

Ideologically, the groundwork for the subsequent Reformation was laid by Renaissance humanists who believed that the Scriptures

Religious texts, including scripture, are texts which various religions consider to be of central importance to their religious tradition. They often feature a compilation or discussion of beliefs, ritual practices, moral commandments and ...

were the best source of Christian theology and criticised religious practices which they considered superstitious. By 1520 Martin Luther's new ideas were known and debated in England, but Protestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

s were a religious minority and heretic

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, particularly the accepted beliefs or religious law of a religious organization. A heretic is a proponent of heresy.

Heresy in Christianity, Judai ...

s under the law. However, historians have noted that activities such as the dissolution of the monasteries enriched the "Tudor kleptocracy".

The theology

Theology is the study of religious belief from a Religion, religious perspective, with a focus on the nature of divinity. It is taught as an Discipline (academia), academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itse ...

and liturgy

Liturgy is the customary public ritual of worship performed by a religious group. As a religious phenomenon, liturgy represents a communal response to and participation in the sacred through activities reflecting praise, thanksgiving, remembra ...

of the Church of England became markedly Protestant during the reign of Henry's son Edward VI

Edward VI (12 October 1537 ŌĆō 6 July 1553) was King of England and King of Ireland, Ireland from 28 January 1547 until his death in 1553. He was crowned on 20 February 1547 at the age of nine. The only surviving son of Henry VIII by his thi ...

() largely along lines laid down by Archbishop Thomas Cranmer

Thomas Cranmer (2 July 1489 ŌĆō 21 March 1556) was a theologian, leader of the English Reformation and Archbishop of Canterbury during the reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI and, for a short time, Mary I. He is honoured as a Oxford Martyrs, martyr ...

. Under Mary I

Mary I (18 February 1516 ŌĆō 17 November 1558), also known as Mary Tudor, was Queen of England and Ireland from July 1553 and Queen of Spain as the wife of King Philip II from January 1556 until her death in 1558. She made vigorous a ...

(), Catholicism was briefly restored. The Elizabethan Religious Settlement

The Elizabethan Religious Settlement is the name given to the religious and political arrangements made for England during the reign of Elizabeth I (1558ŌĆō1603). The settlement, implemented from 1559 to 1563, marked the end of the English Ref ...

reintroduced the Protestant religion but in a more moderate manner. Nevertheless, disputes over the structure, theology and worship of the Church of England continued for generations.

The English Reformation is generally considered to have concluded during the reign of Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was List of English monarchs, Queen of England and List of Irish monarchs, Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. She was the last and longest reigning monarch of the House of Tudo ...

(), but scholars also speak of a "Long Reformation" stretching into the 17th and 18th centuries. This time period includes the violent disputes over religion during the Stuart period

The Stuart period of British history lasted from 1603 to 1714 during the dynasty of the House of Stuart. The period was plagued by internal and religious strife, and a large-scale civil war which resulted in the Execution of Charles I, execu ...

, most famously the English Civil War

The English Civil War or Great Rebellion was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Cavaliers, Royalists and Roundhead, Parliamentarians in the Kingdom of England from 1642 to 1651. Part of the wider 1639 to 1653 Wars of th ...

, which resulted in the rule of Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English statesman, politician and soldier, widely regarded as one of the most important figures in British history. He came to prominence during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, initially ...

, a Puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to rid the Church of England of what they considered to be Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should b ...

. After the Stuart Restoration

The Stuart Restoration was the reinstatement in May 1660 of the Stuart monarchy in Kingdom of England, England, Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland, and Kingdom of Ireland, Ireland. It replaced the Commonwealth of England, established in January 164 ...

and the Glorious Revolution

The Glorious Revolution, also known as the Revolution of 1688, was the deposition of James II and VII, James II and VII in November 1688. He was replaced by his daughter Mary II, Mary II and her Dutch husband, William III of Orange ...

, the Church of England remained the established church, but a number of nonconformist churches now existed whose members suffered various civil disabilities

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and political life of ...

until these were removed many years later. A substantial but dwindling minority of people from the late-16th to early-19th centuries remained Catholics in EnglandŌĆötheir church organisation remained illegal until the Roman Catholic Relief Act 1829

The Roman Catholic Relief Act 1829 ( 10 Geo. 4. c. 7), also known as the Catholic Emancipation Act 1829, was an act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that removed the sacramental tests that barred Roman Catholics in the United Kingdom f ...

.

Competing religious ideas

Late medieval Catholicism

The Medieval English church was part of the largerCatholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

led by the pope

The pope is the bishop of Rome and the Head of the Church#Catholic Church, visible head of the worldwide Catholic Church. He is also known as the supreme pontiff, Roman pontiff, or sovereign pontiff. From the 8th century until 1870, the po ...

in Rome

Rome (Italian language, Italian and , ) is the capital city and most populated (municipality) of Italy. It is also the administrative centre of the Lazio Regions of Italy, region and of the Metropolitan City of Rome. A special named with 2, ...

. The dominant view of salvation

Salvation (from Latin: ''salvatio'', from ''salva'', 'safe, saved') is the state of being saved or protected from harm or a dire situation. In religion and theology, ''salvation'' generally refers to the deliverance of the soul from sin and its c ...

in the late medieval church taught that contrite

In Christianity, contrition or contriteness (, i.e. a breaking of something hardened) is repentance for sins one has committed. The remorseful person is said to be ''contrite''.

A central concept in much of Christianity, contrition is regarded ...

persons should cooperate with God

In monotheistic belief systems, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator, and principal object of faith. In polytheistic belief systems, a god is "a spirit or being believed to have created, or for controlling some part of the un ...

's grace towards their salvation (see synergism

In Christian theology, synergism refers to the cooperative effort between God and humanity in the process of Salvation in Christianity, salvation. Before Augustine of Hippo (354ŌĆō430), synergism was almost universally endorsed. Later, it came to ...

) by performing charitable acts, which would merit reward in Heaven. God's grace

Grace may refer to:

Places United States

* Grace, Idaho, a city

* Grace (CTA station), Chicago Transit Authority's Howard Line, Illinois

* Little Goose Creek (Kentucky), location of Grace post office

* Grace, Carroll County, Missouri, an uni ...

was ordinarily given through the seven sacrament

A sacrament is a Christian rite which is recognized as being particularly important and significant. There are various views on the existence, number and meaning of such rites. Many Christians consider the sacraments to be a visible symbol ...

sŌĆöBaptism

Baptism (from ) is a Christians, Christian sacrament of initiation almost invariably with the use of water. It may be performed by aspersion, sprinkling or affusion, pouring water on the head, or by immersion baptism, immersing in water eit ...

, Confirmation

In Christian denominations that practice infant baptism, confirmation is seen as the sealing of the covenant (religion), covenant created in baptism. Those being confirmed are known as confirmands. The ceremony typically involves laying on o ...

, Marriage

Marriage, also called matrimony or wedlock, is a culturally and often legally recognised union between people called spouses. It establishes rights and obligations between them, as well as between them and their children (if any), and b ...

, Holy Orders

In certain Christian denominations, holy orders are the ordination, ordained ministries of bishop, priest (presbyter), and deacon, and the sacrament or rite by which candidates are ordained to those orders. Churches recognizing these orders inclu ...

, Anointing of the Sick, Penance

Penance is any act or a set of actions done out of contrition for sins committed, as well as an alternative name for the Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, and Oriental Orthodox sacrament of Reconciliation or Confession.

The word ''penance'' derive ...

and the Eucharist

The Eucharist ( ; from , ), also called Holy Communion, the Blessed Sacrament or the Lord's Supper, is a Christianity, Christian Rite (Christianity), rite, considered a sacrament in most churches and an Ordinance (Christianity), ordinance in ...

. The Eucharist was celebrated during the Mass

Mass is an Intrinsic and extrinsic properties, intrinsic property of a physical body, body. It was traditionally believed to be related to the physical quantity, quantity of matter in a body, until the discovery of the atom and particle physi ...

, the central act of Catholic worship. In this service, a priest

A priest is a religious leader authorized to perform the sacred rituals of a religion, especially as a mediatory agent between humans and one or more deity, deities. They also have the authority or power to administer religious rites; in parti ...

consecrated bread and wine to become the body

Body may refer to:

In science

* Physical body, an object in physics that represents a large amount, has mass or takes up space

* Body (biology), the physical material of an organism

* Body plan, the physical features shared by a group of anim ...

and blood of Christ

Blood of Christ, also known as the Most Precious Blood, in Christian theology refers to the physical blood actually shed by Jesus Christ primarily on the Cross, and the salvation which Christianity teaches was accomplished thereby, or the sacram ...

through transubstantiation

Transubstantiation (; Greek language, Greek: ╬╝╬ĄŽä╬┐ŽģŽā╬»ŽēŽā╬╣Žé ''metousiosis'') is, according to the teaching of the Catholic Church, "the change of the whole substance of sacramental bread, bread into the substance of the Body of Christ and ...

. The church taught that, in the name of the congregation, the priest offered to God the same sacrifice of Christ on the cross that provided atonement

Atonement, atoning, or making amends is the concept of a person taking action to correct previous wrongdoing on their part, either through direct action to undo the consequences of that act, equivalent action to do good for others, or some othe ...

for the sins

In religious context, sin is a transgression against divine law or a law of the deities. Each culture has its own interpretation of what it means to commit a sin. While sins are generally considered actions, any thought, word, or act considere ...

of humanity.

The Mass was also an offering of prayer by which the living could help soul

The soul is the purported MindŌĆōbody dualism, immaterial aspect or essence of a Outline of life forms, living being. It is typically believed to be Immortality, immortal and to exist apart from the material world. The three main theories that ...

s in purgatory

In Christianity, Purgatory (, borrowed into English language, English via Anglo-Norman language, Anglo-Norman and Old French) is a passing Intermediate state (Christianity), intermediate state after physical death for purifying or purging a soul ...

. While genuine penance removed the guilt attached to sin, Catholicism taught that a penalty could remain in the case of imperfect contrition

In Christianity, contrition or contriteness (, i.e. a breaking of something hardened) is repentance for sins one has committed. The remorseful person is said to be ''contrite''.

A central concept in much of Christianity, contrition is regarded ...

. It was believed that most people would end their lives with these penalties unsatisfied and would have to spend "time" in purgatory. Time in purgatory could be lessened through indulgence

In the teaching of the Catholic Church, an indulgence (, from , 'permit') is "a way to reduce the amount of punishment one has to undergo for (forgiven) sins". The ''Catechism of the Catholic Church'' describes an indulgence as "a remission bef ...

s and prayers for the dead

Religions with the belief in a final judgment, a resurrection of the dead or an intermediate state (such as Hades or purgatory) often offer prayers on behalf of the dead to God.

Buddhism

For most funerals that follow the tradition of Chinese Budd ...

, which were made possible by the communion of saints

The communion of saints (Latin: , ), when referred to persons, is the spiritual union of the members of the Christian Church, living and the dead, but excluding the damned. They are all part of a single " mystical body", with Christ as the head, ...

. Religious guild

A guild ( ) is an association of artisans and merchants who oversee the practice of their craft/trade in a particular territory. The earliest types of guild formed as organizations of tradespeople belonging to a professional association. They so ...

s sponsored intercessory Masses for their members through chantries

A chantry is an ecclesiastical term that may have either of two related meanings:

# a chantry service, a set of Christian liturgical celebrations for the dead (made up of the Requiem Mass and the Office of the Dead), or

# a chantry chapel, a bu ...

. The monk

A monk (; from , ''monachos'', "single, solitary" via Latin ) is a man who is a member of a religious order and lives in a monastery. A monk usually lives his life in prayer and contemplation. The concept is ancient and can be seen in many reli ...

s and nun

A nun is a woman who vows to dedicate her life to religious service and contemplation, typically living under vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience in the enclosure of a monastery or convent.''The Oxford English Dictionary'', vol. X, page 5 ...

s who lived in monasteries

A monastery is a building or complex of buildings comprising the domestic quarters and workplaces of monastics, monks or nuns, whether living in communities or alone ( hermits). A monastery generally includes a place reserved for prayer which m ...

prayed for souls as well. By popular demand, "prayer for the dead dominated Catholic devotion in much of northern Europe."

English Catholicism was strong and popular in the early 1500s. One measure of popular engagement is financial contribution. Besides paying obligatory tithe

A tithe (; from Old English: ''teogo├Ša'' "tenth") is a one-tenth part of something, paid as a contribution to a religious organization or compulsory tax to government. Modern tithes are normally voluntary and paid in money, cash, cheques or v ...

s, English people voluntarily donated large amounts of money to their parish church

A parish church (or parochial church) in Christianity is the Church (building), church which acts as the religious centre of a parish. In many parts of the world, especially in rural areas, the parish church may play a significant role in com ...

es.

Lollardy

Lollardy

Lollardy was a proto-Protestantism, proto-Protestant Christianity, Christian religious movement that was active in England from the mid-14th century until the 16th-century English Reformation. It was initially led by John Wycliffe, a Catholic C ...

anticipated some Protestant teachings. This anticlerical

Anti-clericalism is opposition to religious authority, typically in social or political matters. Historically, anti-clericalism in Christian traditions has been opposed to the influence of Catholicism. Anti-clericalism is related to secularism, ...

movement originated from the teachings of the English theologian John Wycliffe

John Wycliffe (; also spelled Wyclif, Wickliffe, and other variants; 1328 ŌĆō 31 December 1384) was an English scholastic philosopher, Christianity, Christian reformer, Catholic priest, and a theology professor at the University of Oxfor ...

(c. 1331ŌĆö1384), and the Catholic Church considered it heretical

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, particularly the accepted beliefs or religious law of a religious organization. A heretic is a proponent of heresy.

Heresy in Christianity, Judai ...

. Lollards believed in the primacy of scripture and that the Bible should be available in the vernacular

Vernacular is the ordinary, informal, spoken language, spoken form of language, particularly when perceptual dialectology, perceived as having lower social status or less Prestige (sociolinguistics), prestige than standard language, which is mor ...

languages for the benefit of the laity

In religious organizations, the laity () ŌĆö individually a layperson, layman or laywoman ŌĆö consists of all Church membership, members who are not part of the clergy, usually including any non-Ordination, ordained members of religious orders, e ...

. They prioritised preaching

A sermon is a religious discourse or oration by a preacher, usually a member of clergy. Sermons address a scriptural, theological, or moral topic, usually expounding on a type of belief, law, or behavior within both past and present contexts. E ...

scripture over the sacraments and did not believe in transubstantiation

Transubstantiation (; Greek language, Greek: ╬╝╬ĄŽä╬┐ŽģŽā╬»ŽēŽā╬╣Žé ''metousiosis'') is, according to the teaching of the Catholic Church, "the change of the whole substance of sacramental bread, bread into the substance of the Body of Christ and ...

. In addition, they condemned prayers for the dead and denied that confession to a priest was necessary for salvation. Lollards believed the Catholic Church was a false church, but they outwardly conformed to Catholicism to evade persecution. When Lollards gathered together, they read the Wycliffite Bible, an English translation of the Latin Vulgate

The Vulgate () is a late-4th-century Bible translations into Latin, Latin translation of the Bible. It is largely the work of Saint Jerome who, in 382, had been commissioned by Pope Damasus I to revise the Gospels used by the Diocese of ...

.

In 1401 the Parliament of England

The Parliament of England was the legislature of the Kingdom of England from the 13th century until 1707 when it was replaced by the Parliament of Great Britain. Parliament evolved from the Great Council of England, great council of Lords Spi ...

passed the Suppression of Heresy Act, the first English law authorising the burning

Combustion, or burning, is a high-temperature exothermic redox chemical reaction between a fuel (the reductant) and an oxidant, usually atmospheric oxygen, that produces oxidized, often gaseous products, in a mixture termed as smoke. Combust ...

of unrepentant or reoffending heretics. In reaction to Lollardy, the 1409 Constitutions of Oxford The Constitutions of Oxford or ''Constitutiones Thomae Arundel'' were several resolutions of the 1407 university convocation intended to deal with the use of Scripture in lectures and sermons at Oxford University, following disturbances caused by t ...

prohibited vernacular Bible translations unless authorised by the bishops. This effectively became a total ban as the bishops never did authorise an official English translation. At the same time, the Bible was available in most other European languages

There are over 250 languages indigenous to Europe, and most belong to the Indo-European language family. Out of a total European population of 744 million as of 2018, some 94% are native speakers of an Indo-European language. The three larges ...

. As literacy rates increased, a growing number of orthodox laity who could read English but not Latin resorted to reading the Wycliffite Bible.

Lollards were forced underground and survived as a tiny movement of peasants and artisans. It "helped to create popular reception-areas for the newly imported Lutheranism

Lutheranism is a major branch of Protestantism that emerged under the work of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German friar and Protestant Reformers, reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practices of the Catholic Church launched ...

".

Humanism

Some Renaissance humanists, such asErasmus

Desiderius Erasmus Roterodamus ( ; ; 28 October c. 1466 ŌĆō 12 July 1536), commonly known in English as Erasmus of Rotterdam or simply Erasmus, was a Dutch Christian humanist, Catholic priest and Catholic theology, theologian, educationalist ...

(who lived in England for a time), John Colet

John Colet (January 1467 ŌĆō 16 September 1519) was an English Catholic priest and educational pioneer.

Colet was an English scholar, Renaissance humanist, theologian, member of the Worshipful Company of Mercers, and Dean of St Paul's Cathedr ...

and Thomas More

Sir Thomas More (7 February 1478 ŌĆō 6 July 1535), venerated in the Catholic Church as Saint Thomas More, was an English lawyer, judge, social philosopher, author, statesman, theologian, and noted Renaissance humanist. He also served Henry VII ...

, called for a return ''ad fontes

''Ad fontes'' is a Latin expression which means " ackto the sources" (lit. "to the sources"). The phrase epitomizes the renewed study of Greek and Latin classics in Renaissance humanism, subsequently extended to Biblical texts. The idea in bo ...

'' ("back to the sources") of Christian faithŌĆöthe scriptures as understood through textual, linguistic, classical and patristic scholarshipŌĆöand wanted to make the Bible available in the vernacular. Humanists criticised so-called superstitious

A superstition is any belief or practice considered by non-practitioners to be irrational or supernatural, attributed to fate or magic, perceived supernatural influence, or fear of that which is unknown. It is commonly applied to beliefs and p ...

practices and clerical corruption, while emphasising inward piety over religious ritual. Some of the early Protestant leaders went through a humanist phase before embracing the new movement. A notable early use of the English word ''reformation'' came in 1512, when the English bishops were called together by Henry, notionally to discuss the extirpation of the rump Lollard heresy. John Colet (then working with Erasmus on the establishment of his school) gave a notoriously confrontational sermon on Romans 12:2 ("Be ye not conformed to this world, but be ye reformed in the newness of your minds") saying that the first to reform must be the bishops themselves, then the clergy, and only then the laity.

Lutheranism

TheProtestant Reformation

The Reformation, also known as the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation, was a time of major theological movement in Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the papacy and ...

was initiated by Martin Luther

Martin Luther ( ; ; 10 November 1483 ŌĆō 18 February 1546) was a German priest, Theology, theologian, author, hymnwriter, professor, and former Order of Saint Augustine, Augustinian friar. Luther was the seminal figure of the Reformation, Pr ...

, a German friar

A friar is a member of one of the mendicant orders in the Catholic Church. There are also friars outside of the Catholic Church, such as within the Anglican Communion. The term, first used in the 12th or 13th century, distinguishes the mendi ...

. By the early 1520s, Luther's views were known and disputed in England. The main plank of Luther's theology was justification by faith alone rather than by faith with good works. In other words, justification is a gift from God received through faith

Faith is confidence or trust in a person, thing, or concept. In the context of religion, faith is " belief in God or in the doctrines or teachings of religion".

According to the Merriam-Webster's Dictionary, faith has multiple definitions, inc ...

.

If Luther was correct, then the Mass, the sacraments, charitable acts, prayers to saints

File:Prayers-collage.png, 300px, alt=Collage of various religionists praying ŌĆō Clickable Image, Collage of various religionists praying ''(Clickable image ŌĆō use cursor to identify.)''

rect 0 0 1000 1000 Shinto festivalgoer praying in front ...

, prayers for the dead, pilgrimage

A pilgrimage is a travel, journey to a holy place, which can lead to a personal transformation, after which the pilgrim returns to their daily life. A pilgrim (from the Latin ''peregrinus'') is a traveler (literally one who has come from afar) w ...

, and the veneration of relic

In religion, a relic is an object or article of religious significance from the past. It usually consists of the physical remains or personal effects of a saint or other person preserved for the purpose of veneration as a tangible memorial. Reli ...

s do not mediate divine favour. To believe otherwise would be superstition at best and idolatry

Idolatry is the worship of an idol as though it were a deity. In Abrahamic religions (namely Judaism, Samaritanism, Christianity, Islam, and the Bah├Ī╩╝├Ł Faith) idolatry connotes the worship of something or someone other than the Abrahamic ...

at worst. Early Protestants portrayed Catholic practices such as confession to priests, clerical celibacy

Clerical celibacy is the requirement in certain religions that some or all members of the clergy be unmarried. Clerical celibacy also requires abstention from deliberately indulging in sexual thoughts and behavior outside of marriage, because thes ...

, and requirements to fast

Fast or FAST may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* "Fast" (Juice Wrld song), 2019

* "Fast" (Luke Bryan song), 2016

* "Fast" (Sueco song), 2019

* "Fast" (GloToven song), 2019

* ''Fast'', an album by Custom, 2002

* ''Fast'', a 2010 short fil ...

and keep vows

A vow ( Lat. ''votum'', vow, promise; see vote) is a promise or oath. A vow is used as a promise that is solemn rather than casual.

Marriage vows

Marriage vows are binding promises each partner in a couple makes to the other during a wedding ...

as burdensome and spiritually oppressive. Not only did purgatory lack any biblical basis according to Protestants, but the clergy were also accused of leveraging the fear of purgatory to make money from prayers and masses. The Catholics countered that justification by faith alone was a "licence to sin".

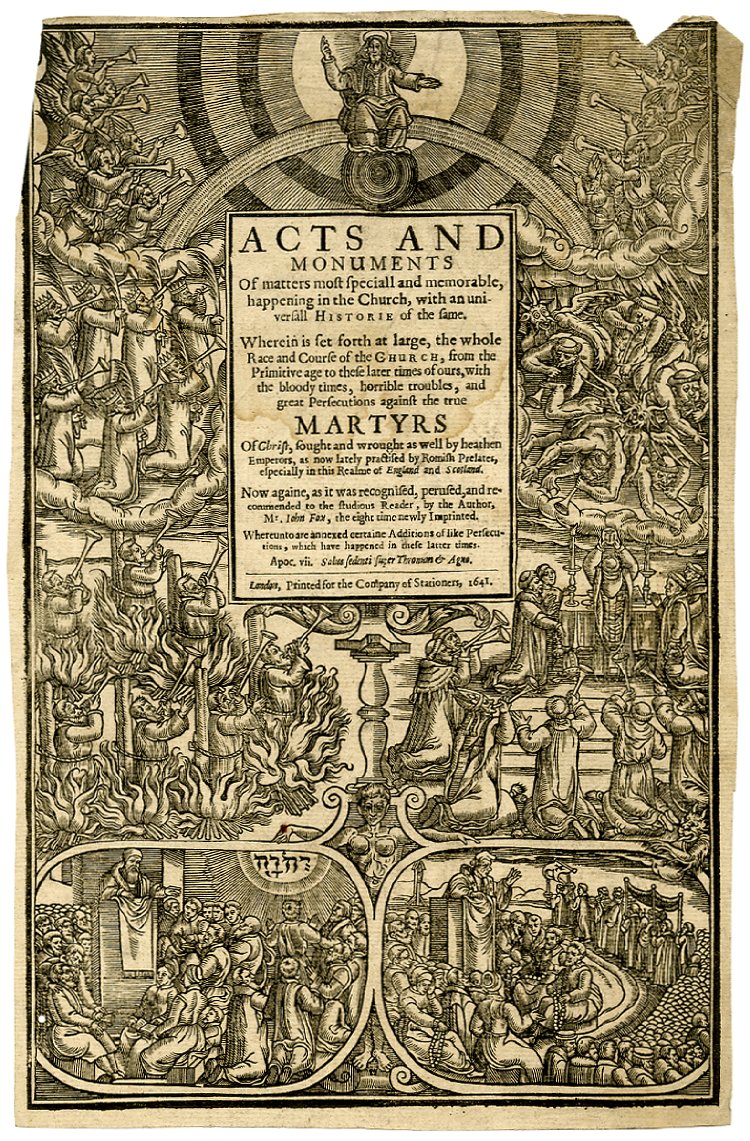

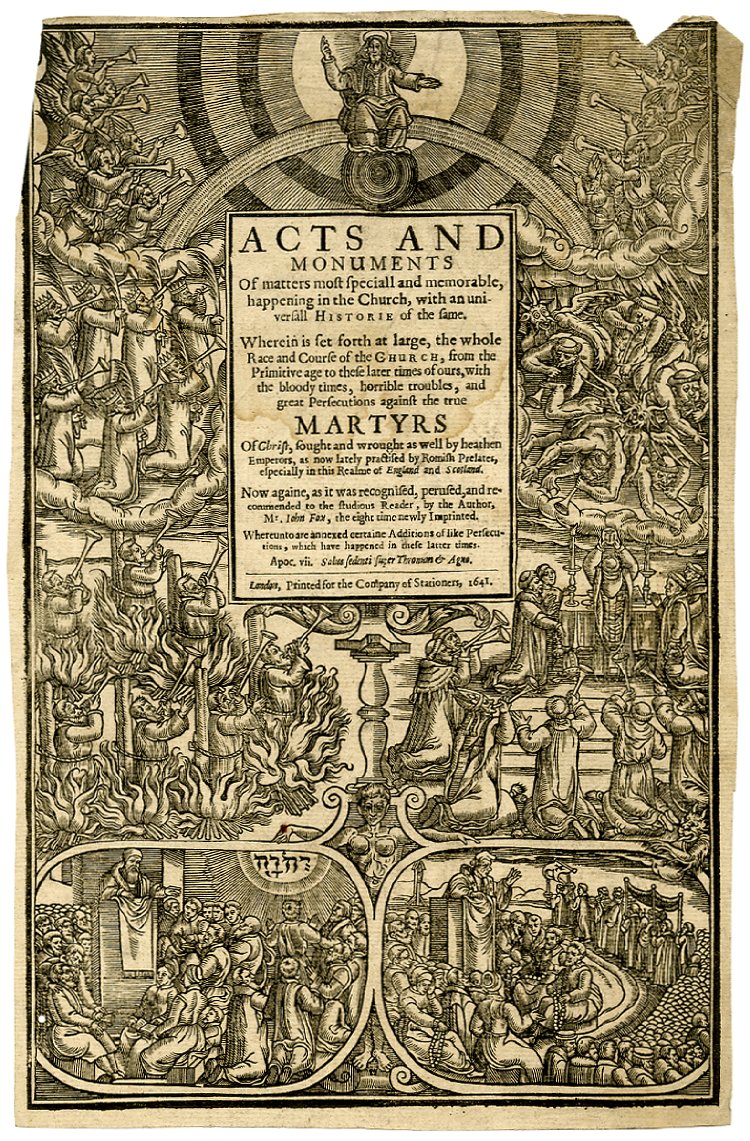

The publication of

The publication of William Tyndale

William Tyndale (; sometimes spelled ''Tynsdale'', ''Tindall'', ''Tindill'', ''Tyndall''; – October 1536) was an English Biblical scholar and linguist who became a leading figure in the Protestantism, Protestant Reformation in the year ...

's English New Testament

The New Testament (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus in Christianity, Jesus, as well as events relating to Christianity in the 1st century, first-century Christianit ...

in 1526 helped to spread Protestant ideas. Printed abroad and smuggled into the country, the Tyndale Bible

The Tyndale Bible (TYN) generally refers to the body of biblical translations by William Tyndale into Early Modern English, made . Tyndale's biblical text is credited with being the first English-language Biblical translation to work directly ...

was the first English Bible to be mass-produced; there were probably 16,000 copies in England by 1536. Tyndale's translation was highly influential, forming the basis of all subsequent English translations until the 20th century. An attack on traditional religion, Tyndale's translation included an epilogue explaining Luther's theology of justification by faith, and many translation choices were designed to undermine traditional Catholic teachings. Tyndale translated the Greek word ''charis'' as ''favour'' rather than ''grace'' to de-emphasise the role of grace-giving sacraments. His choice of ''love'' rather than ''charity'' to translate ''agape

(; ) is "the highest form of love, charity" and "the love of God for uman beingsand of uman beingsfor God". This is in contrast to , brotherly love, or , self-love, as it embraces a profound sacrificial love that transcends and persists rega ...

'' de-emphasised good works. When rendering the Greek verb '' metanoeite'' into English, Tyndale used ''repent

Repentance is reviewing one's actions and feeling contrition or regret for past or present wrongdoings, which is accompanied by commitment to and actual actions that show and prove a change for the better.

In modern times, it is generally seen ...

'' rather than ''do penance''. The former word indicated an internal turning to God, while the latter translation supported the sacrament of confession.

The Protestant ideas were popular among some parts of the English population, especially among academics and merchants with connections to continental Europe. Protestant thought was better received at the University of Cambridge

The University of Cambridge is a Public university, public collegiate university, collegiate research university in Cambridge, England. Founded in 1209, the University of Cambridge is the List of oldest universities in continuous operation, wo ...

than at the University of Oxford

The University of Oxford is a collegiate university, collegiate research university in Oxford, England. There is evidence of teaching as early as 1096, making it the oldest university in the English-speaking world and the List of oldest un ...

. A group of reform-minded Cambridge students (known by the moniker "Little Germany") met at the White Horse tavern from the mid-1520s. Its members included Robert Barnes, Hugh Latimer

Hugh Latimer ( ŌĆō 16 October 1555) was a Fellow of Clare College, Cambridge, and Bishop of Worcester during the Reformation, and later Church of England chaplain to King Edward VI. In 1555 under the Catholic Queen Mary I he was burned at the ...

, John Frith John Frith may refer to:

* John Frith (assailant) (fl. 1760ŌĆō1791), English petitioner and asylum inmate

* John Frith (cartoonist) (), Australian cartoonist, at ''The Herald'' in Melbourne in the 1950s and 1960s

* John Frith (martyr) (1503ŌĆō1533 ...

, Thomas Bilney

Thomas Bilney ( 149519 August 1531) was an English priest, Protestant reformer, and martyr of the English Reformation.

Early life

Thomas Bilney was born around 1495 in Norfolk, most likely in Norwich. Nothing is known of his parents excep ...

, George Joye

George Joye (also Joy and ) (c. 1495 ŌĆō 1553) was a 16th-century Bible List of Bible translators, translator who produced the first printed Bible translations, translation of several books of the Old Testament into English (1530ŌĆō1534), as well ...

, and Thomas Arthur.

Those who held Protestant sympathies remained a religious minority until political events intervened. As heretics in the eyes of church and state, early Protestants were persecuted. Between 1530 and 1533, Thomas Hitton (England's first Protestant martyr

A martyr (, ''m├Īrtys'', 'witness' Word stem, stem , ''martyr-'') is someone who suffers persecution and death for advocating, renouncing, or refusing to renounce or advocate, a religious belief or other cause as demanded by an external party. In ...

), Thomas Bilney, Richard Bayfield, John Tewkesbury, James Bainham

James Bainham (died 30 April 1532) was an English lawyer and Protestant reformer who was burned as a heretic in 1532.

Life

According to John Foxe he was a son of Sir Alexander Bainham, who was sheriff of Gloucestershire in 1497, 1501, and 1516; ...

, Thomas Benet, Thomas Harding

Thomas Harding (born 1448 in Cambridge, Gloucestershire, England and died at Chesham, Buckinghamshire, England, May 1532) was a sixteenth-century English religious dissident who, while waiting to be burnt at the stake as a Lollard in 1532, wa ...

, John Frith, and Andrew Hewet were burned to death. William Tracy

William Tracy (December 1, 1917 ŌĆō July 18, 1967) was an American character actor.

Early life and career

Tracy was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

He is perhaps best known for the role of Pepi Katona, the delivery boy, in '' The Shop Ar ...

was posthumously convicted of heresy for denying purgatory and affirming justification by faith, and his corpse was disinterred and burned.

Henrician Reformation

Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is known for his Wives of Henry VIII, six marriages and his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. ...

acceded to the English throne in 1509 at the age of 17. He made a dynastic marriage with Catherine of Aragon

Catherine of Aragon (also spelt as Katherine,

historical Spanish: , now: ; 16 December 1485 ŌĆō 7 January 1536) was List of English royal consorts, Queen of England as the Wives of Henry VIII, first wife of King Henry VIII from their marr ...

, the widow of his brother Arthur

Arthur is a masculine given name of uncertain etymology. Its popularity derives from it being the name of the legendary hero King Arthur.

A common spelling variant used in many Slavic, Romance, and Germanic languages is Artur. In Spanish and Ital ...

, in June 1509, just before his coronation on Midsummer's Day

Midsummer is a celebration of the season of summer, taking place on or near the date of the summer solstice in the Northern Hemisphere; the longest day of the year. The name "midsummer" mainly refers to summer solstice festivals of European or ...

. Unlike his father, who was secretive and conservative, young Henry appeared the epitome of chivalry and sociability. An observant Catholic, he heard up to five masses a day (except during the hunting-season).

As with many of his contemporary monarchs, Henry felt his prerogatives were not recognised or were threatened by the Popes, and ''vice versa''. In the period 1513 to 1519, he contended with Pope Leo X

Pope Leo X (; born Giovanni di Lorenzo de' Medici, 11 December 14751 December 1521) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 9 March 1513 to his death in December 1521.

Born into the prominent political and banking Me ...

to remove the bishop of Tournai

Tournai ( , ; ; ; , sometimes Anglicisation (linguistics), anglicised in older sources as "Tournay") is a city and Municipalities in Belgium, municipality of Wallonia located in the Hainaut Province, Province of Hainaut, Belgium. It lies by ...

, the region of modern-day Belgium which Henry had then personally conquered, and developed increasingly imperialist

Imperialism is the maintaining and extending of power over foreign nations, particularly through expansionism, employing both hard power (military and economic power) and soft power ( diplomatic power and cultural imperialism). Imperialism fo ...

and absolutist justifications.

Annulment controversy

Henry was regarded as having a "powerful but unoriginal mind"; he let himself be influenced by his advisors, from whom he was never apart, by night or day. He was thus susceptible to whoever had his ear. This contributed to a state of hostility between his young contemporaries and theLord Chancellor

The Lord Chancellor, formally titled Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain, is a senior minister of the Crown within the Government of the United Kingdom. The lord chancellor is the minister of justice for England and Wales and the highest-ra ...

, Cardinal Thomas Wolsey

Thomas Wolsey ( ; ŌĆō 29 November 1530) was an English statesman and Catholic cardinal (catholic), cardinal. When Henry VIII became King of England in 1509, Wolsey became the king's Lord High Almoner, almoner. Wolsey's affairs prospered and ...

. As long as Wolsey had his ear, Henry's Catholicism was secure: in 1521, he had defended the Catholic Church from Martin Luther's accusations of heresy in a book he wroteŌĆöprobably with considerable help from the conservative Bishop of Rochester

The Bishop of Rochester is the Ordinary (officer), ordinary of the Church of England's Diocese of Rochester in the Province of Canterbury.

The town of Rochester, Kent, Rochester has the bishop's seat, at the Rochester Cathedral, Cathedral Chur ...

John Fisher

John Fisher (c. 19 October 1469 ŌĆō 22 June 1535) was an English Catholic prelate who served as Bishop of Rochester from 1504 to 1535 and as chancellor of the University of Cambridge. He is honoured as a martyr and saint by the Catholic Chu ...

ŌĆöentitled ''The Defence of the Seven Sacraments

The ''Defence of the Seven Sacraments'' () is a theological treatise published in 1521, written by King Henry VIII of England, allegedly with the assistance of Sir Thomas More. The extent of More's involvement with this project has been a point ...

'', for which he was awarded the title "Defender of the Faith" (''Fidei Defensor

Defender of the Faith ( or, specifically feminine, '; ) is a phrase used as part of the full Royal and noble styles, style of many English, Scottish and later British monarchs since the early 16th century, as well as by other monarchs and heads of ...

'') by Pope Leo X

Pope Leo X (; born Giovanni di Lorenzo de' Medici, 11 December 14751 December 1521) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 9 March 1513 to his death in December 1521.

Born into the prominent political and banking Med ...

. (Successive English and British monarchs have retained this title to the present, even after the Anglican Church broke away from Catholicism, in part because the title was re-conferred by Parliament in 1544, after the split.) Wolsey's enemies at court included those who had been influenced by Lutheran

Lutheranism is a major branch of Protestantism that emerged under the work of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German friar and Protestant Reformers, reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practices of the Catholic Church launched ...

ideas, among whom was attractive, charismatic Anne Boleyn

Anne Boleyn (; 1501 or 1507 ŌĆō 19 May 1536) was List of English royal consorts, Queen of England from 1533 to 1536, as the Wives of Henry VIII, second wife of King Henry VIII. The circumstances of her marriage and execution, by beheading ...

.

Anne arrived at court in 1522 as maid of honour

A maid of honour is a junior attendant of a queen in royal households. The position was and is junior to the lady-in-waiting. The equivalent title and office has historically been used in most European royal courts.

Tudors and Stuarts

Traditi ...

to Queen Catherine, having spent some years in France being educated by Queen Claude

Claude of France (13 October 1499 ŌĆō 26 July 1524) was Queen of France from 1 January 1515 as the wife of King Francis I and Duchess of Brittany in her own right from 9 January 1514 until her death in 1524. She was the eldest daughter of King ...

. She was a woman of "charm, style and wit, with will and savagery which made her a match for Henry". Anne was a distinguished French conversationalist, singer, and dancer. She was cultured and is the disputed author of several songs and poems. By 1527, Henry wanted his marriage to Catherine annulled

Annulment is a legal procedure within secular and religious legal systems for declaring a marriage null and void. Unlike divorce, it is usually retroactive, meaning that an annulled marriage is considered to be invalid from the beginning almo ...

. She had not produced a male heir who survived longer than two months, and Henry wanted a son to secure the Tudor dynasty

The House of Tudor ( ) was an English and Welsh dynasty that held the throne of England from 1485 to 1603. They descended from the Tudors of Penmynydd, a Welsh noble family, and Catherine of Valois. The Tudor monarchs ruled the Kingdom of Eng ...

. Before Henry's father ( Henry VII) acceded to the throne, England had been beset by civil warfare over rival claims to the English crown. Henry wanted to avoid a similar uncertainty over the succession. Catherine of Aragon's only surviving child was Princess Mary.

Henry claimed that this lack of a male heir was because his marriage was "blighted in the eyes of God". Catherine had been his late brother's wife, and it was therefore against biblical teachings for Henry to have married her ( Leviticus 20:21); a special dispensation from

Henry claimed that this lack of a male heir was because his marriage was "blighted in the eyes of God". Catherine had been his late brother's wife, and it was therefore against biblical teachings for Henry to have married her ( Leviticus 20:21); a special dispensation from Pope Julius II

Pope Julius II (; ; born Giuliano della Rovere; 5 December 144321 February 1513) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 1503 to his death, in February 1513. Nicknamed the Warrior Pope, the Battle Pope or the Fearsome ...

had been needed to allow the wedding in the first place. Henry argued the marriage was never valid because the biblical prohibition was part of unbreakable divine law, and even popes could not dispense with it. In 1527, Henry asked Pope Clement VII

Pope Clement VII (; ; born Giulio di Giuliano de' Medici; 26 May 1478 ŌĆō 25 September 1534) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 19 November 1523 to his death on 25 September 1534. Deemed "the most unfortunate o ...

to annul the marriage, but the Pope refused. According to canon law

Canon law (from , , a 'straight measuring rod, ruler') is a set of ordinances and regulations made by ecclesiastical jurisdiction, ecclesiastical authority (church leadership) for the government of a Christian organization or church and its membe ...

, the Pope could not annul a marriage on the basis of a canonical impediment

In the canon law (Catholic Church), canon law of the Catholic Church, an impediment is a legal obstacle that prevents a sacraments of the Catholic Church, sacrament from being performed either Validity and liceity (Catholic Church), validly or lic ...

previously dispensed. Clement also feared the wrath of Catherine's nephew, Holy Roman Emperor

The Holy Roman Emperor, originally and officially the Emperor of the Romans (disambiguation), Emperor of the Romans (; ) during the Middle Ages, and also known as the Roman-German Emperor since the early modern period (; ), was the ruler and h ...

Charles V Charles V may refer to:

Kings and Emperors

* Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor (1500ŌĆō1558)

* Charles V of Naples (1661ŌĆō1700), better known as Charles II of Spain

* Charles V of France (1338ŌĆō1380), called the Wise

Others

* Charles V, Duke ...

, whose troops earlier that year had sacked Rome and briefly taken the Pope prisoner.

The combination of Henry's "scruple of conscience" and his captivation by Anne Boleyn made his desire to rid himself of his queen compelling. The indictment of his chancellor Cardinal Wolsey in 1529 for praemunire

In English history, or ( or ) was the assertion or maintenance of papal jurisdiction, or any other foreign jurisdiction or claim of supremacy in England, against the supremacy of the monarch. The 14th-century law prohibiting this was enforced ...

(taking the authority of the papacy above the Crown) and Wolsey's subsequent death in November 1530 on his way to London to answer a charge of high treason left Henry open to both the influences of the supporters of the queen and the opposing influences of those who sanctioned the abandonment of the Roman allegiance, for whom an annulment was but an opportunity.

Actions against clergy

In 1529 Henry summoned theParliament of England

The Parliament of England was the legislature of the Kingdom of England from the 13th century until 1707 when it was replaced by the Parliament of Great Britain. Parliament evolved from the Great Council of England, great council of Lords Spi ...

to deal with the annulment and other grievances against the church. The Catholic Church was a powerful institution in England with a number of privileges. The King could not tax or sue clergy in civil courts. The church could also grant fugitives sanctuary

A sanctuary, in its original meaning, is a sacred space, sacred place, such as a shrine, protected by ecclesiastical immunity. By the use of such places as a haven, by extension the term has come to be used for any place of safety. This seconda ...

, and many areas of the lawŌĆösuch as family lawŌĆöwere controlled by the church. For centuries, kings had attempted to reduce the church's power, and the English Reformation was a continuation of this power struggle.

The Reformation Parliament sat from 1529 to 1536 and brought together those who wanted reform but who disagreed what form it should take. There were common lawyers who resented the privileges of the clergy to summon laity

In religious organizations, the laity () ŌĆö individually a layperson, layman or laywoman ŌĆö consists of all Church membership, members who are not part of the clergy, usually including any non-Ordination, ordained members of religious orders, e ...

to their ecclesiastical court

In organized Christianity, an ecclesiastical court, also called court Christian or court spiritual, is any of certain non-adversarial courts conducted by church-approved officials having jurisdiction mainly in spiritual or religious matters. Histo ...

s, and there were those who had been influenced by Lutheranism and were hostile to the theology of Rome. Henry's chancellor, Thomas More

Sir Thomas More (7 February 1478 ŌĆō 6 July 1535), venerated in the Catholic Church as Saint Thomas More, was an English lawyer, judge, social philosopher, author, statesman, theologian, and noted Renaissance humanist. He also served Henry VII ...

, successor to Wolsey, also wanted reform: he wanted new laws against heresy. The lawyer and member of Parliament Thomas Cromwell

Thomas Cromwell (; ŌĆō 28 July 1540) was an English statesman and lawyer who served as List of English chief ministers, chief minister to King Henry VIII from 1534 to 1540, when he was beheaded on orders of the king, who later blamed false cha ...

saw how Parliament could be used to advance royal supremacy over the church and further Protestant beliefs.

Initially, Parliament passed minor legislation to control ecclesiastical fees, clerical pluralism

A benefice () or living is a reward received in exchange for services rendered and as a retainer for future services. The Roman Empire used the Latin term as a benefit to an individual from the Empire for services rendered. Its use was adopted by ...

, and sanctuary. In the matter of the annulment, no progress seemed possible. The Pope seemed more afraid of Emperor Charles V than of Henry. Anne, Cromwell and their allies wished simply to ignore the Pope, but in October 1530 a meeting of clergy and lawyers advised that Parliament could not empower the Archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the Primus inter pares, ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the bishop of the diocese of Canterbury. The first archbishop ...

to act against the Pope's prohibition. Henry thus resolved to bully the priest

A priest is a religious leader authorized to perform the sacred rituals of a religion, especially as a mediatory agent between humans and one or more deity, deities. They also have the authority or power to administer religious rites; in parti ...

s.

Having first charged eight bishops and seven other clerics with praemunire

In English history, or ( or ) was the assertion or maintenance of papal jurisdiction, or any other foreign jurisdiction or claim of supremacy in England, against the supremacy of the monarch. The 14th-century law prohibiting this was enforced ...

, the King decided in 1530 to proceed against the whole clergy for violating the 1392 Statute of Praemunire

The Statute of Praemunire ( 16 Ric. 2. c. 5) was an act of the Parliament of England enacted in 1392, during the reign of Richard II. Its intention was to limit the powers of the papacy in England, by making it illegal to appeal an English cou ...

, which forbade obedience to the Pope or any foreign ruler. Henry wanted the clergy of Canterbury province

The Canterbury Province was a province of New Zealand from 1853 until the abolition of provincial government in 1876. Its capital was Christchurch.

History

Canterbury was founded in December 1850 by the Canterbury Association of influential En ...

to pay ┬Ż100,000 for their pardon; this was a sum equal to the Crown's annual income. This was agreed by the Convocation of Canterbury on 24 January 1531. It wanted the payment spread over five years, but Henry refused. The convocation responded by withdrawing their payment altogether and demanded that Henry should fulfil certain guarantees before they would give him the money. Henry refused these conditions, agreeing only to the five-year period of payment. On 7 February, Convocation was asked to agree to five articles that specified that:

# The clergy should recognise Henry as the "sole protector and supreme head of the English Church and clergy"

# The King was responsible for the souls of his subjects

# The privileges of the church were upheld only if they did not detract from the royal prerogative

The royal prerogative is a body of customary authority, Privilege (law), privilege, and immunity recognised in common law (and sometimes in Civil law (legal system), civil law jurisdictions possessing a monarchy) as belonging to the monarch, so ...

and the laws of the realm

# The King pardoned the clergy for violating the Statute of Praemunire

# The laity were also pardoned.

In Parliament, Bishop Fisher championed Catherine and the clergy, inserting into the first article the phrase "as far as the word of God allows". On 11 February, William Warham

William Warham ( ŌĆō 22 August 1532) was the Archbishop of Canterbury from 1503 to his death in 1532.

Early life and education

Warham was the son of Robert Warham of Malshanger in Hampshire. He was educated at Winchester College and New Colleg ...

, Archbishop of Canterbury, presented the revised wording to Convocation. The clergy were to acknowledge the King to be "singular protector, supreme lord and even, so far as the law of Christ allows, supreme head of the English Church and clergy". When Warham requested a discussion, there was silence. Warham then said, "He who is silent seems to consent", to which a bishop responded, "Then we are all silent." The Convocation granted consent to the King's five articles and the payment on 8 March 1531. Later, the Convocation of York agreed to the same on behalf of the clergy of York province. That same year, Parliament passed the Pardon to Clergy Act 1531.

By 1532, Cromwell was responsible for managing government business in the House of Commons. He authored and presented to the Commons the ''Supplication against the Ordinaries

The Supplication against the Ordinaries was a petition passed by the House of Commons in 1532. It was the result of grievances against Church of England prelates and the clergy. Ordinaries in this Act means a cleric, such as the diocesan bishop ...

'', which was a list of grievances against the bishops, including abuses of power and Convocation's independent legislative authority. After passing the Commons, the ''Supplication'' was presented to the King as a petition for reform on 18 March. On 26 March, the ''Act in Conditional Restraint of Annates'' mandated the clergy pay no more than five percent of their first year's revenue (annates

Annates ( or ; , from ', "year") were a payment from the recipient of an ecclesiastical benefice to the collating authorities. Eventually, they consisted of half or the whole of the first year's profits of a benefice; after the appropriation of th ...

) to Rome.

On 10 May, the King demanded of Convocation that the church renounce all authority to make laws. On 15 May, Convocation renounced its authority to make canon law without royal assentŌĆöthe so called Submission of the Clergy

The Submission of the Clergy was a process by which the Catholic Church in England gave up their power to formulate church laws without the King's licence and assent. It was passed first by the Convocation of Canterbury in 1532 and then by the R ...

. (Parliament subsequently gave this statutory force with the Submission of the Clergy Act.) The next day, More resigned as lord chancellor. This left Cromwell as Henry's chief minister. (Cromwell never became chancellor. His power cameŌĆöand was lostŌĆöthrough his informal relations with Henry.)

Separation from Rome

Archbishop Warham died in August 1532. Henry wantedThomas Cranmer

Thomas Cranmer (2 July 1489 ŌĆō 21 March 1556) was a theologian, leader of the English Reformation and Archbishop of Canterbury during the reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI and, for a short time, Mary I. He is honoured as a Oxford Martyrs, martyr ...

ŌĆöa Protestant who could be relied on to oppose the papacyŌĆöto replace him. The Pope reluctantly approved Cranmer's appointment, and he was consecrated on 30 March 1533. By this time, Henry was secretly married to Anne, who was pregnant. The impending birth of an heir gave new urgency to annulling his marriage to Catherine. Nevertheless, a decision continued to be delayed because Rome was the final authority in all ecclesiastical matters. To address this issue, Parliament passed the Act in Restraint of Appeals

The Ecclesiastical Appeals Act 1533 ( 24 Hen. 8. c. 12), also called the Statute in Restraint of Appeals, the Act of Appeals and the Act of Restraints in Appeals, was an Act of the Parliament of England.

It was passed in the first week of Apri ...

, which outlawed appeals to Rome on ecclesiastical matters and declared that

This declared England an independent country in every respect. English historian Geoffrey Elton

Sir Geoffrey Rudolph Elton (born Gottfried Rudolf Otto Ehrenberg; 17 August 1921 ŌĆō 4 December 1994) was a German-born British political and constitutional historian, specialising in the Tudor period. He taught at Clare College, Cambridge, and ...

called this act an "essential ingredient" of the "Tudor revolution" in that it expounded a theory of national sovereignty

A nation state, or nation-state, is a political entity in which the state (a centralized political organization ruling over a population within a territory) and the nation (a community based on a common identity) are (broadly or ideally) co ...

. Cranmer was now able to grant an annulment of the marriage to Catherine as Henry required, pronouncing on 23 May the judgment that Henry's marriage with Catherine was against the law of God. The Pope responded by excommunicating

Excommunication is an institutional act of religious censure used to deprive, suspend, or limit membership in a religious community or to restrict certain rights within it, in particular those of being in communion with other members of the con ...

Henry on 11 July 1533. Anne gave birth to a daughter, Princess Elizabeth, on 7 September 1533.

In 1534, Parliament took further action to limit papal authority in England. A new Heresy Act ensured that no one could be punished for speaking against the Pope and also made it more difficult to convict someone of heresy; however, sacramentarians and Anabaptist

Anabaptism (from Neo-Latin , from the Greek language, Greek : 're-' and 'baptism'; , earlier also )Since the middle of the 20th century, the German-speaking world no longer uses the term (translation: "Re-baptizers"), considering it biased. ...

s continued to be vigorously persecuted. The Act in Absolute Restraint of Annates

The Appointment of Bishops Act 1533 ( 25 Hen. 8. c. 20), also known as the Act Concerning Ecclesiastical Appointments and Absolute Restraint of Annates, is an act of the Parliament of England.

The act remains partly in force in England and Wal ...

outlawed all annates to Rome and also ordered that if cathedral

A cathedral is a church (building), church that contains the of a bishop, thus serving as the central church of a diocese, Annual conferences within Methodism, conference, or episcopate. Churches with the function of "cathedral" are usually s ...

s refused the King's nomination for bishop, they would be liable to punishment by praemunire. The Act of First Fruits and Tenths transferred the taxes on ecclesiastical income from the Pope to the Crown. The Act Concerning Peter's Pence and Dispensations

The Ecclesiastical Licences Act 1533 ( 25 Hen. 8. c. 21), also known as the Dispensations Act 1533, Peter's Pence Act 1533 or the Act Concerning Peter's Pence and Dispensations, is an act of the Parliament of England. It was passed by the Engl ...

outlawed the annual payment by landowners of Peter's Pence

Peter's Pence (or ''Denarii Sancti Petri'' and "Alms of St Peter") are donations or payments made directly to the Holy See of the Catholic Church. The practice began under the Saxons in Kingdom of England, England and spread through Europe. Both ...

to the Pope, and transferred the power to grant dispensations and licences from the Pope to the Archbishop of Canterbury. This Act also reiterated that England had "no superior under God, but only your Grace" and that Henry's "imperial crown" had been diminished by "the unreasonable and uncharitable usurpations and exactions" of the Pope.

The First Act of Supremacy

The Acts of Supremacy are two acts passed by the Parliament of England in the 16th century that established the English monarchs as the head of the Church of England; two similar laws were passed by the Parliament of Ireland establishing the Eng ...

made Henry Supreme Head of the Church of England and disregarded any "usage, custom, foreign laws, foreign authority rprescription". In case this should be resisted, Parliament passed the Treasons Act 1534

The Treasons Act 1534 or High Treason Act 1534 ( 26 Hen. 8. c. 13) was an act of the Parliament of England passed in 1534, during the reign of King Henry VIII.

Background

This act was passed after the Act of Supremacy 1534 ( 26 Hen. 8. c. 1 ...

, which made it high treason punishable by death to deny royal supremacy. The following year, Thomas More and John Fisher were executed under this legislation. Finally, in 1536, Parliament passed the Act against the Pope's Authority, which removed the last part of papal authority still legal. This was Rome's power in England to decide disputes concerning Scripture

Religious texts, including scripture, are texts which various religions consider to be of central importance to their religious tradition. They often feature a compilation or discussion of beliefs, ritual practices, moral commandments and ...

.

Moderate religious reform

The break with Rome gave Henry the power to administer the English Church, tax it, appoint its officials, and control its laws. It also gave him control over the church's doctrine and ritual. While Henry remained a traditional Catholic, his most important supporters in breaking with Rome were the Protestants. Yet, not all of his supporters were Protestants. Some were traditionalists, such asStephen Gardiner

Stephen Gardiner (27 July 1483 ŌĆō 12 November 1555) was an English Catholic bishop and politician during the English Reformation period who served as Lord Chancellor during the reign of Queen Mary I.

Early life

Gardiner was born in Bury St Ed ...

, opposed to the new theology but felt papal supremacy

Papal supremacy is the doctrine of the Catholic Church that the Pope, by reason of his office as Vicar of Christ, the visible source and foundation of the unity both of the bishops and of the whole company of the faithful, and as priest of the ...

was not essential to the Church of England's identity. The King relied on Protestants, such as Thomas Cromwell and Thomas Cranmer, to carry out his religious programme and embraced the language of the continental Reformation, while maintaining a middle way between religious extremes. What followed was a period of doctrinal confusion as both conservatives and reformers attempted to shape the church's future direction.

The reformers were aided by Cromwell, who in January 1535 was made vicegerent

Vicegerent is the official administrative deputy of a ruler or head of state: ''vice'' (Latin for "in place of") and ''gerere'' (Latin for "to carry on, conduct").

In Oxford colleges, a vicegerent is often someone appointed by the Master of a ...

in spirituals. Effectively the King's vicar general

A vicar general (previously, archdeacon) is the principal deputy of the bishop or archbishop of a diocese or an archdiocese for the exercise of administrative authority and possesses the title of local ordinary. As vicar of the bishop, the vica ...

, Cromwell's authority was greater than that of bishops, even the Archbishop of Canterbury. Largely due to Anne Boleyn's influence, a number of Protestants were appointed bishops between 1534 and 1536. These included Latimer, Thomas Goodrich

Sir Thomas Goodrich (also spelled Goodricke; died 10 May 1554) was an English ecclesiastic and statesman who was Bishop of Ely from 1534 until his death.

Life

He was a son of Edward Goodrich of East Kirkby, Lincolnshire and brother of He ...

, John Salcot, Nicholas Shaxton

Nicholas Shaxton (c. 1485 ŌĆō 1556) was Bishop of Salisbury. For a time, he had been a Reformer, but recanted this position, returning to the Roman faith. Under Henry VIII, he attempted to persuade other Protestant leaders to also recant. Unde ...

, William Barlow, John Hilsey

John Hilsey (a.k.a. Hildesley or Hildesleigh; died 4 August 1539) was an English Dominican, prior provincial of his order, then an agent of Henry VIII and the English Reformation, and Bishop of Rochester.

Life

According to Anthony Wood, Hilse ...

, and Edward Foxe

Edward Foxe (c. 1496 ŌĆō 8 May 1538) was an English churchman, Bishop of Hereford. He played a major role in Henry VIII's divorce from Catherine of Aragon, and he assisted in drafting the '' Ten Articles'' of 1536.

Early life

He was born at ...