This article describes the

syntax

In linguistics, syntax ( ) is the study of how words and morphemes combine to form larger units such as phrases and sentences. Central concerns of syntax include word order, grammatical relations, hierarchical sentence structure (constituenc ...

of

clause

In language, a clause is a Constituent (linguistics), constituent or Phrase (grammar), phrase that comprises a semantic predicand (expressed or not) and a semantic Predicate (grammar), predicate. A typical clause consists of a subject (grammar), ...

s in the

English language

English is a West Germanic language that developed in early medieval England and has since become a English as a lingua franca, global lingua franca. The namesake of the language is the Angles (tribe), Angles, one of the Germanic peoples th ...

, chiefly in

Modern English

Modern English, sometimes called New English (NE) or present-day English (PDE) as opposed to Middle and Old English, is the form of the English language that has been spoken since the Great Vowel Shift in England

England is a Count ...

. A clause is often said to be the smallest grammatical unit that can express a

complete proposition. But this

semantic

Semantics is the study of linguistic Meaning (philosophy), meaning. It examines what meaning is, how words get their meaning, and how the meaning of a complex expression depends on its parts. Part of this process involves the distinction betwee ...

idea of a clause leaves out much of English clause syntax. For example, clauses can be questions,

but questions are not propositions. A syntactic description of an English clause is that it is a

subject and a

verb

A verb is a word that generally conveys an action (''bring'', ''read'', ''walk'', ''run'', ''learn''), an occurrence (''happen'', ''become''), or a state of being (''be'', ''exist'', ''stand''). In the usual description of English, the basic f ...

. But this too fails, as a clause need not have a subject, as with the imperative,

and, in many theories, an English clause may be verbless.

The idea of what qualifies varies between theories and has changed over time.

History of the concept

The earliest use of the word ''clause'' in

Middle English

Middle English (abbreviated to ME) is a form of the English language that was spoken after the Norman Conquest of 1066, until the late 15th century. The English language underwent distinct variations and developments following the Old English pe ...

is non-technical and similar to the current everyday meaning of ''

phrase

In grammar, a phrasecalled expression in some contextsis a group of words or singular word acting as a grammatical unit. For instance, the English language, English expression "the very happy squirrel" is a noun phrase which contains the adject ...

'': "A sentence or clause, a brief statement, a short passage, a short text or quotation; in a ~, briefly, in short; (b) a written message or letter; a story; a long passage in an author's source."

The first English grammar, ''Pamphlet for Grammar'' by

William Bullokar

William Bullokar was a 16th-century Printer (publisher), printer who devised a 40-letter Phonetic transcription, phonetic alphabet for the English language. Its characters were presented in the Blackletter, black-letter or "gothic" writing style ...

, was published in 1586 and briefly mentions ''clause'' once, without explaining the concept.

A technical meaning is evident from at least 1865, when

Walter Scott Dalgleish describe a clause as "a term of a sentence containing a

predicate

Predicate or predication may refer to:

* Predicate (grammar), in linguistics

* Predication (philosophy)

* several closely related uses in mathematics and formal logic:

**Predicate (mathematical logic)

**Propositional function

**Finitary relation, o ...

within itself; as... a man ''who is wise''."

In the early days of

generative grammar

Generative grammar is a research tradition in linguistics that aims to explain the cognitive basis of language by formulating and testing explicit models of humans' subconscious grammatical knowledge. Generative linguists, or generativists (), ...

, new conceptions of the clause were emerging.

Paul Postal

Paul Martin Postal (born November 10, 1936, in Weehawken, New Jersey) is an American linguist.

Biography

Postal received his PhD from Yale University

Yale University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in New ...

and

Noam Chomsky

Avram Noam Chomsky (born December 7, 1928) is an American professor and public intellectual known for his work in linguistics, political activism, and social criticism. Sometimes called "the father of modern linguistics", Chomsky is also a ...

argued that every

verb phrase

In linguistics, a verb phrase (VP) is a syntax, syntactic unit composed of a verb and its argument (linguistics), arguments except the subject (grammar), subject of an independent clause or coordinate clause. Thus, in the sentence ''A fat man quic ...

had a subject, even if none was expressed, (though

Joan Bresnan

Joan Wanda Bresnan FBA (born August 22, 1945) is Sadie Dernham Patek Professor in Humanities Emerita at Stanford University. She is best known as one of the architects (with Ronald Kaplan) of the theoretical framework of lexical functional gram ...

and

Michael Brame disagreed). As a result, every verb phrase (VP) was thought to

head

A head is the part of an organism which usually includes the ears, brain, forehead, cheeks, chin, eyes, nose, and mouth, each of which aid in various sensory functions such as sight, hearing, smell, and taste. Some very simple ani ...

a clause.

The idea of verbless clauses was perhaps introduced by

James McCawley in the early 1980s with examples like the underlined part of ''with

John in jail''... meaning "John is in jail".

Types of clause in Modern English

Clauses can be classified as

''independent'' (main clauses) and

''dependent'' (subordinate clauses). An

orthogonal

In mathematics, orthogonality (mathematics), orthogonality is the generalization of the geometric notion of ''perpendicularity''. Although many authors use the two terms ''perpendicular'' and ''orthogonal'' interchangeably, the term ''perpendic ...

way of classifying clauses is by the

speech act

In the philosophy of language and linguistics, a speech act is something expressed by an individual that not only presents information but performs an action as well. For example, the phrase "I would like the mashed potatoes; could you please pas ...

they are typically associated with. This results in

declarative (making a statement),

interrogative

An interrogative clause is a clause whose form is typically associated with question-like meanings. For instance, the English sentence (linguistics), sentence "Is Hannah sick?" has interrogative syntax which distinguishes it from its Declarative ...

(asking a question), exclamative (exclaiming), and

imperative (giving an order) clauses, each with its distinctive syntactic features. Declarative and interrogative clauses may be independent or dependent, but imperative clauses are only independent.

Dependent clauses have other cross-cutting types. These include

relative and

comparative

The degrees of comparison of adjectives and adverbs are the various forms taken by adjectives and adverbs when used to compare two entities (comparative degree), three or more entities (superlative degree), or when not comparing entities (positi ...

clauses; and participial and infinitival clauses.

Finally, there are verbless clauses.

Examples

Independent clause types

Declarative

By far, the most common type of English clause is the independent declarative.

The typical form of such clauses consist of two

constituents, a

subject and a

head

A head is the part of an organism which usually includes the ears, brain, forehead, cheeks, chin, eyes, nose, and mouth, each of which aid in various sensory functions such as sight, hearing, smell, and taste. Some very simple ani ...

verb phrase

In linguistics, a verb phrase (VP) is a syntax, syntactic unit composed of a verb and its argument (linguistics), arguments except the subject (grammar), subject of an independent clause or coordinate clause. Thus, in the sentence ''A fat man quic ...

(VP) in that order,

with the subject corresponding to the predicand and the head VP corresponding to the predicate. For example, the clause ''Jo did it'' has the subject

noun phrase

A noun phrase – or NP or nominal (phrase) – is a phrase that usually has a noun or pronoun as its head, and has the same grammatical functions as a noun. Noun phrases are very common cross-linguistically, and they may be the most frequently ...

''Jo'' followed by the head VP ''did it''. Declarative clauses are associated with the speech act of making a

statement

Statement or statements may refer to: Common uses

*Statement (computer science), the smallest standalone element of an imperative programming language

*Statement (logic and semantics), declarative sentence that is either true or false

*Statement, ...

.

The following diagram shows the syntactic structure of the clause ''this is a tree''. The clause has a subject noun phrase (Subj: NP) ''this'' and a head verb phrase (Head: VP). The VP has a head verb ''is'' and a predicative complement NP (PredComp: NP) ''a tree''.

Information packaging

In linguistics, information structure, also called information packaging, describes the way in which information is formally packaged within a sentence.Lambrecht, Knud. 1994. ''Information structure and sentence form.'' Cambridge: Cambridge Univ ...

constructions can result in the addition of other constituents and various constituent orders.

For example, the ''it-''

cleft construction has ''it'' as a

dummy subject

A dummy pronoun, also known as an expletive pronoun, is a deictic pronoun that fulfills a syntactical requirement without providing a contextually explicit meaning of its referent. As such, it is an example of exophora.

A dummy pronoun is use ...

, followed by a head VP containing a form of the verb ''be'' + a complement corresponding to the predicand + a relative clause whose head corresponds to the predicate. So, the example above as an ''it-''cleft is ''It was Jo who did it.''

= V2

=

Some declarative clauses follow

V2 order, which is to say the first verb appears as the second constituent, even if the subject is not the first constituent. An example would be ''Never did I say such a thing'', where ''never'' is the first constituent and ''did'' is the verb in V2 position. Addition of a tensed form of the auxiliary verb ''do'' is called

''do'' support.

Interrogative

There are two main types of independent

interrogative

An interrogative clause is a clause whose form is typically associated with question-like meanings. For instance, the English sentence (linguistics), sentence "Is Hannah sick?" has interrogative syntax which distinguishes it from its Declarative ...

clauses: open and closed.

These are most associated with asking

question

A question is an utterance which serves as a request for information. Questions are sometimes distinguished from interrogatives, which are the grammar, grammatical forms, typically used to express them. Rhetorical questions, for instance, are i ...

s, but they can be used for other speech acts such as giving advice, making requests, etc.

Open interrogatives include an

interrogative word

An interrogative word or question word is a function word used to ask a question, such as ''what, which'', ''when'', ''where'', '' who, whom, whose'', ''why'', ''whether'' and ''how''. They are sometimes called wh-words, because in English most ...

, which, in most cases either is the subject (e.g., ''

Who went to the shop?'') or comes before an

auxiliary verb

An auxiliary verb ( abbreviated ) is a verb that adds functional or grammatical meaning to the clause in which it occurs, so as to express tense, aspect, modality, voice, emphasis, etc. Auxiliary verbs usually accompany an infinitive verb or ...

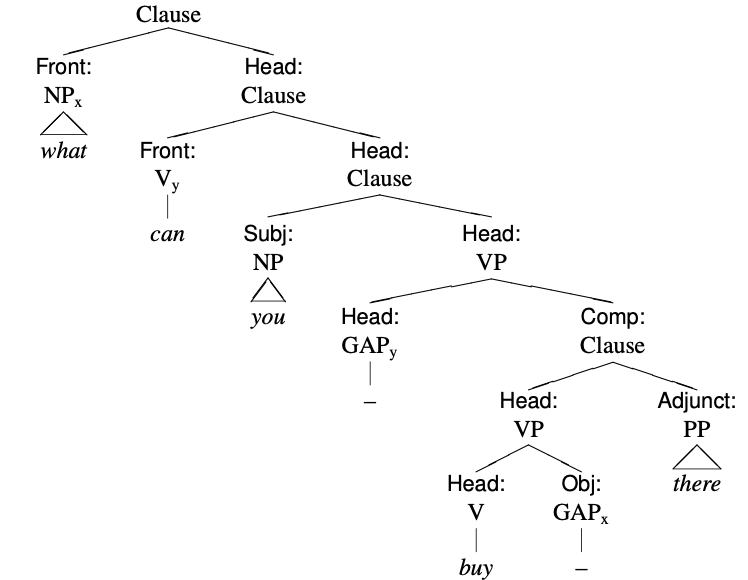

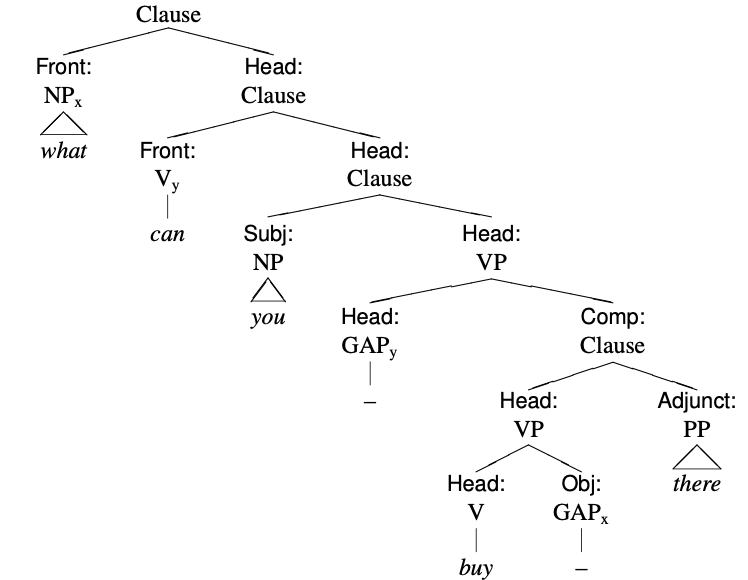

+ the subject. This is seen in ''

What can you buy there?'' where ''what'' is the interrogative word, ''can'' is the auxiliary, and ''you'' is the subject. In such cases, the interrogative word is said to be

fronted, or it may be part of a fronted constituent, as in ''

which shop did you go to?'' When no auxiliary verb is present then ''do'' support is required.

The interrogative word can also appear in the non fronted position, so that the example above could be ''You can buy

what there?'' where ''what'' is an

object

Object may refer to:

General meanings

* Object (philosophy), a thing, being, or concept

** Object (abstract), an object which does not exist at any particular time or place

** Physical object, an identifiable collection of matter

* Goal, an a ...

in the VP. When it is fronted, many modern theories of grammar posit a

gap in the non-fronted position: ''What can you buy __ there?'' This is a kind of

discontinuity.

The following diagram shows the syntactic structure of the clause ''What can you buy there?'' The clause has a fronted noun phrase (Front: NP) ''what'', which is co-indexed to the object gap in a lower VP.

Closed interrogative clauses can be further subdivided as polar or alternative. A polar interrogative is one to which the expected response is ''yes'' or ''no''. For example, ''Do you like sweets?'' is a polar interrogative and another case of ''do'' support. An alternative interrogative is one asking for a choice among two or more alternatives, as in ''Would you like coffee or tea?'' In both types of closed interrogatives, an auxiliary verb is fronted. That is to say, it comes before the subject. In the example above, ''would'' is the fronted auxiliary verb and ''you'' is the subject.

Another minor clause type is the

interrogative tag. A tag is appended to a statement and includes only an auxiliary verb and a pronoun: ''you did it,

didn't you?''

Imperative

In most imperative clauses the subject is absent: ''Eat your dinner!'' However imperative clauses may include the subject for emphasis: ''You eat your dinner!'' In either case, the predicand is understood to be the person being addressed. There is also an imperative construction with ''let'' and the first person plural, as in ''let's go.'' An example like ''let them go'' is still understood as having a

second-person predicand.

Imperatives are closely associated with the speak acts of commands and other directives.

The verb in an imperative clause is in the

base form, such as ''eat'', ''write'', ''be'', etc.

Negative imperatives uses ''do''-support, even if the verb is ''be''; see below.

Exclamative

Exclamative clauses start with either the

adjective

An adjective (abbreviations, abbreviated ) is a word that describes or defines a noun or noun phrase. Its semantic role is to change information given by the noun.

Traditionally, adjectives are considered one of the main part of speech, parts of ...

''what'' or the adverb ''how'' and are typically associated with exclamations.

As with open interrogatives, the ''what'' or ''how'' phrase is fronted unless – in the case of ''what'' – it's the subject.

# ''

What great students you have!'' (subject)

# ''

What a nice thing you did.'' (object gap)

# ''

How kind you are.'' (predicative complement gap)

The following diagram shows the syntactic structure of the clause ''How kind you are.'' The clause has a fronted adjective phrase (Front: AdjP) ''how kind'', which is co-indexed to the predicative complement gap (PredComp: gap) in the VP.

Dependent clause types

Clauses can be nested within each other, sometimes up to several levels. These clauses within clauses are said to be dependent. For example, the sentence ''I know the woman

who says !'' contains the following dependent clauses: a non-finite clause (''drinking beer'') within a content clause (''she saw your son drinking beer'') within a relative clause (''who says she saw your son drinking beer''). These are all within the independent declarative clause (the whole sentence).

As the example above shows, a dependent clause may be ''finite'' (based on a

finite verb

A finite verb is a verb that contextually complements a subject, which can be either explicit (like in the English indicative) or implicit (like in null subject languages or the English imperative). A finite transitive verb or a finite intra ...

, as independent clauses are), or

''non-finite'' (based on a verb in the form of an infinitive or participle). Particular types of dependent clause include

relative clauses (also called "adjective clauses"),

content clause

In grammar, a content clause is a dependent clause that provides content implied or commented upon by an independent clause. The term was coined by Danish linguist Otto Jespersen. Content clauses have also traditionally been called noun clauses or ...

s (traditionally called "noun clauses" and also known as "complement clauses") and

comparative

The degrees of comparison of adjectives and adverbs are the various forms taken by adjectives and adverbs when used to compare two entities (comparative degree), three or more entities (superlative degree), or when not comparing entities (positi ...

clauses, each with its own characteristic syntax.

Traditional English grammar also includes

adverbial clause

An adverbial clause is a dependent clause that functions as an adverb. That is, the entire clause modifies a separate element within a sentence or the sentence itself. As with all clauses, it contains a subject and predicate, though the subject a ...

s,

but since at least 1924, when

Jespersen published ''The philosophy of grammar'',

many linguists have taken these to be

prepositions

Adpositions are a class of words used to express spatial or temporal relations (''in, under, towards, behind, ago'', etc.) or mark various semantic roles (''of, for''). The most common adpositions are prepositions (which precede their complemen ...

with content clause complements.

Relative clauses

Syntactically, relative clauses (also called "adjective clauses") typically contain a gap (as explained above in interrogative clauses). Semantically, they contain an

anaphoric relation to an element in a larger clause, typically to a

noun

In grammar, a noun is a word that represents a concrete or abstract thing, like living creatures, places, actions, qualities, states of existence, and ideas. A noun may serve as an Object (grammar), object or Subject (grammar), subject within a p ...

. There are two main relative clause types: ''wh-'' relatives and non-''wh-'' relatives, the latter of which can be further subdivided into ''that'' and ''bare'' types.

The semantic relation can be seen most easily in (1) above. This clause has a gap in the VP headed by ''built'', where an object would usually appear. For the purposes of illustration, the gap is replaced by ''it'' in the following diagram.

This shows an anaphoric relation inside the relative clause between the gap (filled by the

resumptive pronoun

A resumptive pronoun is a personal pronoun appearing in a relative clause, which restates the antecedent after a pause or interruption (such as an embedded clause, series of adjectives, or a wh-island), as in ''This is the girli that whenever it ...

''it''), and the fronted

relative pronoun

A relative pronoun is a pronoun that marks a relative clause. An example is the word ''which'' in the sentence "This is the house which Jack built." Here the relative pronoun ''which'' introduces the relative clause. The relative clause modifies th ...

''which''. It shows a second anaphoric relation between the relative pronoun and the noun in the main clause ''the house''. This means "this is the house" and also "Jack built the house". In a ''wh''- relative, when the related item in the relative clause is the subject of the relative, there is no gap, so there is only the anaphoric relation between the relative pronoun and an element in the main clause (e.g., ''

Jack,

who built the house, is a good chap.'')

= Non-''wh-'' relatives

=

Non-''wh-'' relative clauses are of two types: ''that'' clauses and bare clauses. In most cases, either one is possible, as shown in (2) above, but when the relative item is the subject of the relative clause, there is a gap in the subject position, and bare relatives are not possible (e.g., ''these are the folks that __ have been helping'', but not ''*these are the folks __ have been helping.'')

Traditional grammar calls ''that'' a relative pronoun, like ''who'' above, but modern grammars consider it to be a

complementizer

In linguistics (especially generative grammar), a complementizer or complementiser (list of glossing abbreviations, glossing abbreviation: ) is a functional category (part of speech) that includes those words that can be used to turn a clause in ...

, not a pronoun.

Non-''wh-'' relative clauses are not typically possible with supplementary relatives. (See the main article on

English relative clauses

Relative clauses in the English language are formed principally by means of English relative words, relative words. The basic relative pronouns are ''who (pronoun), who'', ''which'', and ''that''; ''who'' also has the derived forms ''whom'' and ''w ...

for the distinction between integrated and supplementary relatives.)

= ''Wh-'' relatives

=

''Wh-'' relative clauses include a

relative word, a pronoun ''who'' or ''which'', a preposition ''when'' or ''where'', and adverb ''how'', or an adjective, also ''how''. This is fronted, leaving a gap, unless it is the subject or part of the subject.

Comparative clauses

Comparative clauses function chiefly as the complement in

prepositional phrases

An adpositional phrase is a syntactic category that includes ''prepositional phrases'', ''postpositional phrases'', and ''circumpositional phrases''. Adpositional phrases contain an adposition (preposition, postposition, or circumposition) as ...

headed by ''than'' or ''as'' (e.g., ''She is taller than

I am.'' ''She's not as tall as

that tree is''.) Like relative clause, comparatives include a gap. Notice that ''be'' in all its forms typically requires a complement, but in a comparative clause, no complement is possible. In the case where she is 180 cm tall and I am 170 cm tall, I can't say ''*She's taller than

I am 170cm tall'', even though ''I am 170cm tall'' is a perfectly good declarative clause. Instead, there has to be a gap where the complement would usually be.

Content clauses

Like independent clauses, content clauses (also called "noun clauses" or "complement clauses") have subtypes that are associated with speech acts. There are declarative, interrogative, and exclamative content clauses. There are no dependent imperatives.

= Declarative content clauses

=

Declarative content clauses have ''that'' and bare subtypes. Syntactically the bare types are generally identical to the independent declarative clauses. The ''that'' types differ only in that they are marked by the complementizer ''that'' (e.g., ''I know'' (''

that'')

''you did it''.) In most contexts either type is possible, but only the ''that'' type is possible in subject function (e.g., ''

that it works is obvious''), while most prepositions that take clausal complements allow only the bare type (''I chose this because

it works'' but not ''*because

that it works'').

= Interrogative content clauses

=

Like the independent interrogative clauses, interrogative content clauses have open and closed types. In both types, but unlike independent interrogative clauses, the subject always precedes all verbs.

The closed types are marked with the complementizer ''whether'' or ''if.'' For example, the independent closed interrogative ''does it work'' becomes the underlined text in ''I wonder

whether it works''.

The open types begin with an interrogative word. For example, the independent open interrogative ''who did you meet'' becomes the underlined text in ''I wonder who you met''. When the interrogative word is the subject or part of the subject, the dependent form is identical to the independent form.

Non-finite clauses

A

non-finite clause

In linguistics, a non-finite clause is a dependent or embedded clause that represents a state or event in the same way no matter whether it takes place before, during, or after text production. In this sense, a non-finite dependent clause represe ...

is one in which the main verb is in a non-finite form, namely an

infinitive

Infinitive ( abbreviated ) is a linguistics term for certain verb forms existing in many languages, most often used as non-finite verbs that do not show a tense. As with many linguistic concepts, there is not a single definition applicable to all ...

,

past participle

In linguistics, a participle (; abbr. ) is a nonfinite verb form that has some of the characteristics and functions of both verbs and adjectives. More narrowly, ''participle'' has been defined as "a word derived from a verb and used as an adject ...

, or ''-ing'' form (

present participle

In linguistics, a participle (; abbr. ) is a nonfinite verb form that has some of the characteristics and functions of both verbs and adjectives. More narrowly, ''participle'' has been defined as "a word derived from a verb and used as an adject ...

or

gerund

In linguistics, a gerund ( abbreviated ger) is any of various nonfinite verb forms in various languages; most often, but not exclusively, it is one that functions as a noun. The name is derived from Late Latin ''gerundium,'' meaning "which is ...

); for how these forms are made, see

English verbs

Verbs constitute one of the main Part of speech, parts of speech (word classes) in the English language. Like other types of words in the language, English verbs are not heavily inflection, inflected. Most combinations of Grammatical tense, tense ...

. (Such a clause may also be referred to as an ''infinitive phrase'', ''participial phrase'', etc.)

The internal syntax of a non-finite clause is generally similar to that of a finite clause, except that there is usually no subject (and in some cases a missing complement; see below). The following types exist:

*

bare infinitive

Infinitive ( abbreviated ) is a linguistics term for certain verb forms existing in many languages, most often used as non-finite verbs that do not show a tense. As with many linguistic concepts, there is not a single definition applicable to all ...

clause, such as ''go to the party'' in the sentence ''let her go to the party''.

*''to''-

infinitive clause, such as ''to go to the party''. Although there is no subject in such a clause, the performer of the action can (in some contexts) be expressed with a preceding prepositional phrase using ''for'': ''It would be a good idea for her to go to the party.'' The possibility of placing adjuncts between the ''to'' and the verb in such constructions has been the subject of dispute among

prescriptive grammar

Linguistic prescription is the establishment of rules defining publicly preferred usage of language, including rules of spelling, pronunciation, vocabulary, grammar, etc. Linguistic prescriptivism may aim to establish a standard language, teach w ...

ians; see

split infinitive

A split infinitive is a grammatical construction specific to English in which an adverb or adverbial phrase separates the "to" and "infinitive" constituents of what was traditionally called the "full infinitive", but is more commonly known in mod ...

.

*past participial clause (active type), such as ''made a cake'' and ''seen to it''. This is used in forming

perfect

Perfect commonly refers to:

* Perfection; completeness, and excellence

* Perfect (grammar), a grammatical category in some languages

Perfect may also refer to:

Film and television

* ''Perfect'' (1985 film), a romantic drama

* ''Perfect'' (20 ...

constructions (see below), as in ''he has made a cake''; ''I had seen to it''.

*present participial clause, such as ''being in good health''. When such a clause is used as an adjunct to a main clause, its subject is understood to be the same as that of the main clause; when this is not the case, a subject can be included in the participial clause: ''The king being in good health, his physician was able to take a few days' rest.''

*gerund clause. This has the same form as the above, but serves as a noun rather than an adjective or adverb. The pre-appending of a subject in this case (as in ''I don't like you drinking'', rather than the arguably more correct ''...your drinking'') is criticized by some prescriptive grammarians – see

Fused participle.

In certain uses, a non-finite clause contains a missing (

zero

0 (zero) is a number representing an empty quantity. Adding (or subtracting) 0 to any number leaves that number unchanged; in mathematical terminology, 0 is the additive identity of the integers, rational numbers, real numbers, and compl ...

) item – this may be an object or complement of the verb, or the complement of a preposition within the clause (leaving the preposition "

stranded"). Examples of uses of such "passive" non-finite clauses are given below:

*''to''-infinitive clauses – ''this is easy to use'' (zero object of ''use''); ''he is the man to talk to'' (zero complement of preposition ''to'').

*past participial clauses – as used in forming

passive voice

A passive voice construction is a grammatical voice construction that is found in many languages. In a clause with passive voice, the grammatical subject expresses the ''theme'' or ''patient'' of the main verb – that is, the person or thing ...

constructions (''the cake was made'', with zero object of ''made''), and in some other uses, such as ''I want to get it seen to'' (zero complement of ''to''). In many such cases the performer of the action can be expressed using a prepositional phrase with ''by'', as in ''the cake was made by Alan''.

*gerund clauses – particularly after ''want'' and ''need'', as in ''Your car wants/needs cleaning'' (zero object of ''cleaning''), and ''You want/need your head seeing to'' (zero complement of ''to'').

For details of the uses of such clauses, see below. See also

English passive voice

In English, the passive voice is marked by a subject that is followed by a stative verb complemented by a past participle. For example:

The recipient of a sentence's action is referred to as the patient. In sentences using the active voice, t ...

(particularly under

Additional passive constructions).

Verbless clauses

Verbless clauses are composed of a

predicand

In semantics, a predicand is an argument in an utterance, specifically that of which something is predicated. By extension, in syntax, it is the constituent in a clause typically functioning as the subject.

Examples

In the most typical cases ...

and a verbless predicate. For example, the underlined string in

'With the children so sick,''''we've been at home a lot'' means the same thing as the clause ''the children are so sick''. It attributes the predicate "so sick" to the predicand "the children". In most contexts, *''the children so sick'' would be ungrammatical. Verbless clauses of this sort are common as the

complement

Complement may refer to:

The arts

* Complement (music), an interval that, when added to another, spans an octave

** Aggregate complementation, the separation of pitch-class collections into complementary sets

* Complementary color, in the visu ...

of ''with'' or ''without''.

Other

prepositions

Adpositions are a class of words used to express spatial or temporal relations (''in, under, towards, behind, ago'', etc.) or mark various semantic roles (''of, for''). The most common adpositions are prepositions (which precede their complemen ...

such as ''although'', ''once'', ''when'', and ''while'' also take verbless clause complements, such as ''Although

no longer a student, she still dreamed of the school,

'' in which the predicand corresponds to the subject of the main clause, ''she''. Supplements, too can be verbless clauses, as in ''Many people came,

some of them children'' or ''

Break over, they returned to work.''

Neither ''

A comprehensive grammar of the English language

''A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language'' is a descriptive grammar of English written by Randolph Quirk, Sidney Greenbaum, Geoffrey Leech, and Jan Svartvik. It was first published by Longman in 1985.

In 1991, it was called "The g ...

''

nor''

The Cambridge grammar of the English language

''The Cambridge Grammar of the English Language'' (''CamGEL''The abbreviation ''CamGEL'' is less commonly used for the work than is ''CGEL'' (and the authors themselves use ''CGEL'' in their other works), but ''CGEL'' is ambiguous because it has ...

'' offer any speculations about the structure(s) of such clauses. The latter says, without hedging, "the head of a clause (the predicate) is realised by a VP." It is not clear how such a statement could be compatible with the existence of verbless clauses.

Constituents of a clause

A clause typically consists of a subject and head VP, along with any

adjuncts

In brewing, adjuncts are unmalted grains (such as barley, wheat, maize, rice, rye, and oats) or grain products used in brewing beer which supplement the main mash ingredient (such as malted barley). This is often done with the intention of cut ...

(

modifiers

In linguistics, a modifier is an optional element in phrase structure or clause structure which ''modifies'' the meaning of another element in the structure. For instance, the adjective "red" acts as a modifier in the noun phrase "red ball", provi ...

or supplements). The following tree diagram shows the structure of the very simple clause ''she arrived'', which consists of a subject noun phrase and a head verb phrase (VP).

The internal structure of the VP allows a wide range of

complements – most notably one or two

objects – along with any adjuncts. English is an

SVO language, that is, in simple declarative sentences the order of the main components is

SUBJECT + HEAD-VP where the basic VP consists of

HEAD-VERB + OBJECT. A clause may also have fronted constituents, such as question words or auxiliary verbs appearing before the subject.

The presence of complements depends on the

pattern followed by the verb (for example, whether it is a

transitive verb

A transitive verb is a verb that entails one or more transitive objects, for example, 'enjoys' in ''Amadeus enjoys music''. This contrasts with intransitive verbs, which do not entail transitive objects, for example, 'arose' in ''Beatrice arose ...

, i.e. one taking a direct object). A given verb may allow a number of possible patterns (for example, the verb ''write'' may be either transitive, as in ''He writes letters'', or intransitive, as in ''He writes often'').

Some verbs can take two objects: an

indirect object

In linguistics, an object is any of several types of arguments. In subject-prominent, nominative-accusative languages such as English, a transitive verb typically distinguishes between its subject and any of its objects, which can include but ...

and a direct object. An indirect object precedes a direct one, as in ''He gave the dog a bone'' (where ''the dog'' is the indirect object and ''a bone'' the direct object). However the indirect object may also be replaced with a prepositional phrase, usually with the preposition ''to'' or ''for'', as in ''He gave a bone to the dog''. (The latter method is particularly common when the direct object is a

personal pronoun

Personal pronouns are pronouns that are associated primarily with a particular grammatical person – first person (as ''I''), second person (as ''you''), or third person (as ''he'', ''she'', ''it''). Personal pronouns may also take different f ...

and the indirect object is a stronger noun phrase: ''He gave it to the dog'' would be used rather than ?''He gave the dog it''.)

Adjuncts are often placed after the verb and object, as in ''I met John

yesterday''. However other positions in the sentence are also possible. Another adverb which is subject to special rules is the

negating word ''not''; see below.

Objects normally precede other complements in the VP, as in ''I told

him to fetch it'' (where ''him'' is the object, and the infinitive phrase ''to fetch it'' is a further complement). Other possible complements include

prepositional phrases

An adpositional phrase is a syntactic category that includes ''prepositional phrases'', ''postpositional phrases'', and ''circumpositional phrases''. Adpositional phrases contain an adposition (preposition, postposition, or circumposition) as ...

, such as ''for Jim'' in the clause ''They waited

for Jim'' or ''before you did'' in the clause ''I arrived

before you did'';

predicative expression

A predicative expression (or just predicative) is part of a clause predicate, and is an expression that typically follows a copula or linking verb, e.g. ''be'', ''seem'', ''appear'', or that appears as a second complement (object complement) of ...

s, such as ''red'' in ''The ball is

red''; or content or non-finite clauses.

Many English verbs are used together with a particle (such as ''in'' or ''away'') and with preposition phrases in constructions that are commonly referred to as "phrasal verbs". These complements often modify the meaning of the verb in an unpredictable way, and a verb-particle combination such as ''give up'' can be considered a single lexical item. The position of such particles in the clause is subject to different rules from other adverbs; for details see

Phrasal verb

In the traditional grammar of Modern English, a phrasal verb typically constitutes a single semantic unit consisting of a verb followed by a particle (e.g., ''turn down'', ''run into,'' or ''sit up''), sometimes collocated with a preposition (e. ...

.

English is not a "pro-drop" (specifically,

null-subject) language – that is, unlike some languages, English requires that the subject of a clause always be expressed explicitly, even if it can be deduced from the form of the verb and the context, and even if it has no meaningful referent, as in the sentence ''It is raining'', where the subject ''it'' is a

dummy pronoun

A dummy pronoun, also known as an expletive pronoun, is a deictic pronoun that fulfills a syntactical requirement without providing a contextually explicit meaning of its referent. As such, it is an example of exophora.

A dummy pronoun is us ...

. Imperative and non-finite clauses are exceptions, in that they usually do not have a subject expressed.

Variations on SVO pattern

Variations on the basic SVO pattern occur in certain types of clause. The subject is absent in most imperative clauses and most non-finite clauses (see the sections). For cases in which the verb or a verb complement is omitted, see .

The verb and subject are

inverted in most interrogative clauses. This requires that the verb be an

auxiliary

Auxiliary may refer to:

In language

* Auxiliary language (disambiguation)

* Auxiliary verb

In military and law enforcement

* Auxiliary police

* Auxiliaries, civilians or quasi-military personnel who provide support of some kind to a military se ...

(and

''do''-support is used to provide an auxiliary if there is otherwise no invertible verb). This is exemplified in the following tree diagram, which shows a fronted NP ''who'' co-indexed to a gap lower down in the clause. It also shows that auxiliary verb ''did'' in front of the subject NP ''you'', instead of the usual subject–verb order.

The same type of inversion occurs in certain other types of clause, particularly main clauses beginning with an adjunct having negative force (''Never have I witnessed such carnage''), and some dependent clauses expressing a condition (''Should you decide to come,...''). For details see

subject–auxiliary inversion

Subject–auxiliary inversion (SAI; also called subject–operator inversion) is a frequently occurring type of inversion (linguistics), inversion in the English language whereby a finite auxiliary verb – taken here to include finite forms of th ...

and

negative inversion

In linguistics, negative inversion is one of many types of subject–auxiliary inversion in English language, English. A negation (e.g. ''not'', ''no'', ''never'', ''nothing'', etc.) or a word that implies negation (''only'', ''hardly'', ''scarcely ...

.

A somewhat different type of inversion may involve a wider set of verbs (as in ''After the sun comes the rain''); see

subject–verb inversion.

In certain types of clause an object or other complement becomes zero or is brought to the front of the clause: see .

Fronting and zeroing

In interrogative and relative clauses,

''wh''-fronting occurs; that is, the interrogative word or relative pronoun (or in some cases a phrase containing it) is brought to the front of the clause: ''What did you see?'' (the interrogative word ''what'' comes first even though it is the object); ''The man to whom you gave the book...'' (the phrase ''to whom'', containing the relative pronoun, comes to the front of the relative clause; for more detail on relative clauses see

English relative clauses

Relative clauses in the English language are formed principally by means of English relative words, relative words. The basic relative pronouns are ''who (pronoun), who'', ''which'', and ''that''; ''who'' also has the derived forms ''whom'' and ''w ...

).

Fronting of various elements can also occur for reasons of

focus

Focus (: foci or focuses) may refer to:

Arts

* Focus or Focus Festival, former name of the Adelaide Fringe arts festival in East Australia Film

*Focus (2001 film), ''Focus'' (2001 film), a 2001 film based on the Arthur Miller novel

*Focus (2015 ...

; occasionally even an object or other verbal complement can be fronted rather than appear in its usual position after the verb, as in ''I met Tom yesterday, but Jane I haven't seen for ages''. (For cases in which fronting is accompanied by inversion of subject and verb, see

negative inversion

In linguistics, negative inversion is one of many types of subject–auxiliary inversion in English language, English. A negation (e.g. ''not'', ''no'', ''never'', ''nothing'', etc.) or a word that implies negation (''only'', ''hardly'', ''scarcely ...

and

subject–verb inversion.)

In certain types of non-finite clause ("passive" types; see

non-finite clauses

In linguistics, a non-finite clause is a dependent or embedded clause that represents a state or event in the same way no matter whether it takes place before, during, or after text production. In this sense, a non-finite dependent clause represe ...

above), and in some relative clauses, an object or a preposition complement is absent (becomes

zero

0 (zero) is a number representing an empty quantity. Adding (or subtracting) 0 to any number leaves that number unchanged; in mathematical terminology, 0 is the additive identity of the integers, rational numbers, real numbers, and compl ...

). For example, in ''I like the cake you made'', the words ''you made'' form a

reduced relative clause

A reduced relative clause is a relative clause that is not marked by an explicit relative pronoun or relativizer such as ''who'', ''which'' or ''that''. An example is the clause ''I saw'' in the English sentence "This is the man ''I saw''." Unred ...

in which the verb ''made'' has zero object. This can produce

preposition stranding

Preposition stranding or p-stranding is the syntax, syntactic construction in which a so-called ''stranded'', ''hanging'', or ''dangling'' preposition occurs somewhere other than immediately before its corresponding object (grammar), object; for ex ...

(as can ''wh''-fronting): ''I like the song you were listening to''; ''Which chair did you sit on?''

Elliptical clauses

Certain clauses display

ellipsis

The ellipsis (, plural ellipses; from , , ), rendered , alternatively described as suspension points/dots, points/periods of ellipsis, or ellipsis points, or colloquially, dot-dot-dot,. According to Toner it is difficult to establish when t ...

, where some component is omitted, usually by way of avoidance of repetition. Examples include:

*omitted verb between subject and complement, as in ''You love me, and I you'' (where the same verb ''love'' is understood between ''I' and ''you'').''

*

tag questions

A tag question is a construction in which an interrogative element is added to a declarative or an imperative clause. The resulting speech act comprises an assertion paired with a request for confirmation. For instance, the English tag question ...

, as in ''He can't speak French, can he?'' (where the infinitive clause ''speak French'' is understood to be the dependent of ''can'').

*similar short sentences or clauses such as ''I can'', ''there is'', ''we will'', etc., where the omitted non-finite clause or other complement is understood from what has gone before (for examples involving inversion, such as ''so/neither do I'', see

subject–auxiliary inversion

Subject–auxiliary inversion (SAI; also called subject–operator inversion) is a frequently occurring type of inversion (linguistics), inversion in the English language whereby a finite auxiliary verb – taken here to include finite forms of th ...

).

For more analysis and further examples, see

Verb phrase ellipsis

In linguistics, Verb phrase ellipsis (VP ellipsis or VPE) is a type of Ellipsis (linguistics), grammatical omission where a verb phrase is left out (elided) but its meaning can still be inferred from context. For example, "''She will sell sea shell ...

.

Functions of clauses

Independent clauses

Independent clauses generally have no functional relationship to larger syntactic units. The main exception is in a

coordination

Coordination may refer to:

* Coordination (linguistics), a compound grammatical construction

* Coordination complex, consisting of a central atom or ion and a surrounding array of bound molecules or ions

** A chemical reaction to form a coordinati ...

of clauses, where they can be coordinates or heads of a marked clause. An example would be ''I came, and I went'', which is shown in the following syntax tree. Neither coordinate is the head of the coordination; a coordination is a non-headed construction.

The first clause, ''I came'' is unmarked, and cannot be marked. The second is marked with the coordinator ''and'', so that the clause ''I went'' functions as the head of the marked clause ''and I went''.

The example above uses declarative clauses, but the same holds for interrogative, exclamative, and imperative clauses.

Dependent clauses

Dependent clauses are much more various in their functions. They typically function as dependents, but they can also function as heads, despite their names, and the list of possible functions depends on the clause type.

Complement in a verb phrase

Traditional grammar takes clauses like the underlined part of ''heard

she went there'' as noun clauses, under the ideas that they "function as nouns". But these can appear where semantically related noun phrases are not possible: ''We decided that we would meet'', but not ''*We decided a meeting.''

The most typical dependent clause function is

complement

Complement may refer to:

The arts

* Complement (music), an interval that, when added to another, spans an octave

** Aggregate complementation, the separation of pitch-class collections into complementary sets

* Complementary color, in the visu ...

in a verb phrase (VP). Different verbs license different clause types as complements. For example, the verb ''wonder'' licenses interrogative content clauses but not declarative content clauses (e.g., ''I wonder

whether it will work or not''. but not *''I wonder

that it will work''.) Similarly, ''like'' licenses ''that'' declarative content clauses, exclamatives, ''to'' infinitivals and present participials: ''I like

that it looks good''; ''I like

what a great look that is''; ''I like

to think so''; ''I

like being here''. But ''enjoy'', with a very similar meaning, does not license ''to'' infinitival clauses (e.g., ''*I enjoy

to think so''.), and a declarative content clauses complement is marginal

?''I enjoy

that it works''.

Complement in a preposition phrase

Traditional grammar takes constructions like ''before she went there'' to be adverbial clauses, but since Jespersen (1924),

many modern grammars take them to be

prepositional phrases

An adpositional phrase is a syntactic category that includes ''prepositional phrases'', ''postpositional phrases'', and ''circumpositional phrases''. Adpositional phrases contain an adposition (preposition, postposition, or circumposition) as ...

with clausal complements. Prepositions that take clausal complements include ''although'', ''before'', ''if'', ''when'', and many others (See ).

Most such prepositions allow only bare declarative content clauses (e.g., ''before

she went there''), but others are sometimes possible. For example, ''about

whether they are true''.

= Comparative clauses in a prepositional phrase

=

Comparative clauses are almost entirely limited to functioning as the complement of the prepositions ''than'' or ''as''.

Complement in a noun phrase

Some nouns license content clause complements, as in ''the idea

that it might work''. Typically, these nouns

denote

In linguistics and philosophy, the denotation of a word or expression is its strictly literal meaning. For instance, the English word "warm" denotes the property of having high temperature. Denotation is contrasted with other aspects of meaning in ...

thought (e.g., ''idea'', ''decision'', ''guess'', etc.) or language (e.g., ''claim'', ''statement'', etc.). With some nouns, ''to'' infinitival clauses are also possible (e.g., ''the decision to go'').

Complement in an adjective phrase

Quite a few adjectives also license content clause complements, as in ''happy

that you made it''. again, these adjectives tend to be

semantically related to thoughts and feelings (e.g., ''happy'', ''excited'', ''disappointed'', etc.).

Subject in a clause

Most subordinate clause types can function as subject in a clause. The main exceptions are relative clauses, comparative clauses, and bare declarative clauses.

Modifier in a noun phrase

The most common function of relative clauses is modifier in a noun phrase, as in ''the house

that Jack built.''

Supplement in a clause or verb phrase

Most subordinate clause types can function as a supplement in a clause or verb phrase, comparative clauses being the main exception.

Head in a larger clause of the same type

When a subordinate clause has a marker, such as a

coordinator (''and'', ''or'', ''but'', etc.) or

complementizer

In linguistics (especially generative grammar), a complementizer or complementiser (list of glossing abbreviations, glossing abbreviation: ) is a functional category (part of speech) that includes those words that can be used to turn a clause in ...

(''that'', ''whether'', ''if'', etc.), it is headed by a clause of the same type. This is shown in the following syntax tree.

Negation

A clause is

negated

In logic, negation, also called the logical not or logical complement, is an operation that takes a proposition P to another proposition "not P", written \neg P, \mathord P, P^\prime or \overline. It is interpreted intuitively as being true w ...

by the inclusion of the word ''not'':

*In a finite indicative clause in which the finite verb is an auxiliary or copula, the word ''not'' comes after that verb, often forming a

contraction in ''n't'': ''He will not (won't) win''.

*In a finite indicative clause in which there is otherwise no auxiliary or copula,

''do''-support is used to provide one: ''He does not (doesn't) want to win''.

*In the above clause types, if there is inversion (for example, because the sentence is interrogative), the subject may come after the verb and before ''not'', or after the contraction in ''n't'': ''Do you not (Don't you) want to win?'' In the case of inversion expressing a condition, the contracted form is not possible: ''Should you not'' (not: *''Shouldn't you'') ''wish to attend...''

*Negative imperatives are formed with ''do''-support, even in the case of the copula: ''Don't be silly!''

*The negative of the present subjunctive is made by placing ''not'' before the verb: ''...that you not meet us''; ''...that he not be punished''. The past subjunctive ''were'' is negated like the indicative (''were not'', ''weren't'').

*A non-finite clause is negated by placing ''not'' before the verb form: ''not to be outdone'' (sometimes ''not'' is placed after ''to'' in such clauses, though often frowned upon as a

split infinitive

A split infinitive is a grammatical construction specific to English in which an adverb or adverbial phrase separates the "to" and "infinitive" constituents of what was traditionally called the "full infinitive", but is more commonly known in mod ...

), ''not knowing what to do''.

See also

*

English grammar

English grammar is the set of structural rules of the English language. This includes the structure of words, phrases, clauses, Sentence (linguistics), sentences, and whole texts.

Overview

This article describes a generalized, present-day Standar ...

*

English verb tenses

*

English auxiliary verbs

English auxiliary verbs are a small set of English verbs, which include the English modal auxiliary verbs and a few others. Although the Auxiliary verb, auxiliary verbs of English are widely believed to lack inherent semantic meaning and instead ...

*

English passive voice

In English, the passive voice is marked by a subject that is followed by a stative verb complemented by a past participle. For example:

The recipient of a sentence's action is referred to as the patient. In sentences using the active voice, t ...

*

English subjunctive

While the English language lacks distinct inflections for mood, an English subjunctive is recognized in most grammars. Definition and scope of the concept vary widely across the literature, but it is generally associated with the description of ...

References

{{Language syntaxes

Clause

In language, a clause is a Constituent (linguistics), constituent or Phrase (grammar), phrase that comprises a semantic predicand (expressed or not) and a semantic Predicate (grammar), predicate. A typical clause consists of a subject (grammar), ...

Closed interrogative clauses can be further subdivided as polar or alternative. A polar interrogative is one to which the expected response is ''yes'' or ''no''. For example, ''Do you like sweets?'' is a polar interrogative and another case of ''do'' support. An alternative interrogative is one asking for a choice among two or more alternatives, as in ''Would you like coffee or tea?'' In both types of closed interrogatives, an auxiliary verb is fronted. That is to say, it comes before the subject. In the example above, ''would'' is the fronted auxiliary verb and ''you'' is the subject.

Another minor clause type is the interrogative tag. A tag is appended to a statement and includes only an auxiliary verb and a pronoun: ''you did it, didn't you?''

Closed interrogative clauses can be further subdivided as polar or alternative. A polar interrogative is one to which the expected response is ''yes'' or ''no''. For example, ''Do you like sweets?'' is a polar interrogative and another case of ''do'' support. An alternative interrogative is one asking for a choice among two or more alternatives, as in ''Would you like coffee or tea?'' In both types of closed interrogatives, an auxiliary verb is fronted. That is to say, it comes before the subject. In the example above, ''would'' is the fronted auxiliary verb and ''you'' is the subject.

Another minor clause type is the interrogative tag. A tag is appended to a statement and includes only an auxiliary verb and a pronoun: ''you did it, didn't you?''

This shows an anaphoric relation inside the relative clause between the gap (filled by the

This shows an anaphoric relation inside the relative clause between the gap (filled by the