Emerald Tablet on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Emerald Tablet, also known as the Smaragdine Table or the ''Tabula Smaragdina'', is a compact and cryptic text traditionally attributed to the legendary

The oldest version of the ''Emerald Tablet'' is found as an appendix in an encyclopaedic treatise on natural philosophy meant as a

The oldest version of the ''Emerald Tablet'' is found as an appendix in an encyclopaedic treatise on natural philosophy meant as a

Another text of the ''Emerald Tablet'' is found towards the end of the tenth-century

Another text of the ''Emerald Tablet'' is found towards the end of the tenth-century

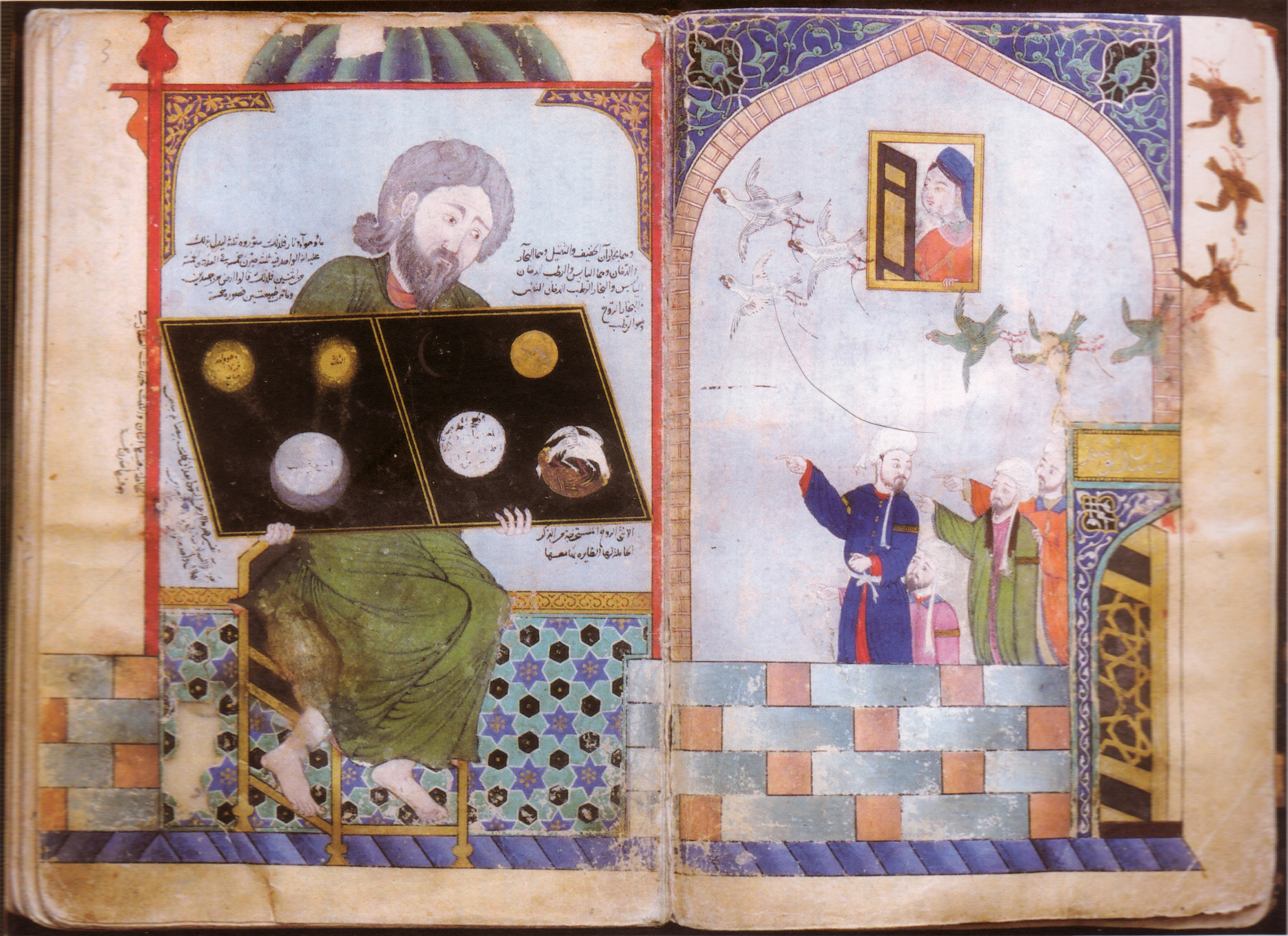

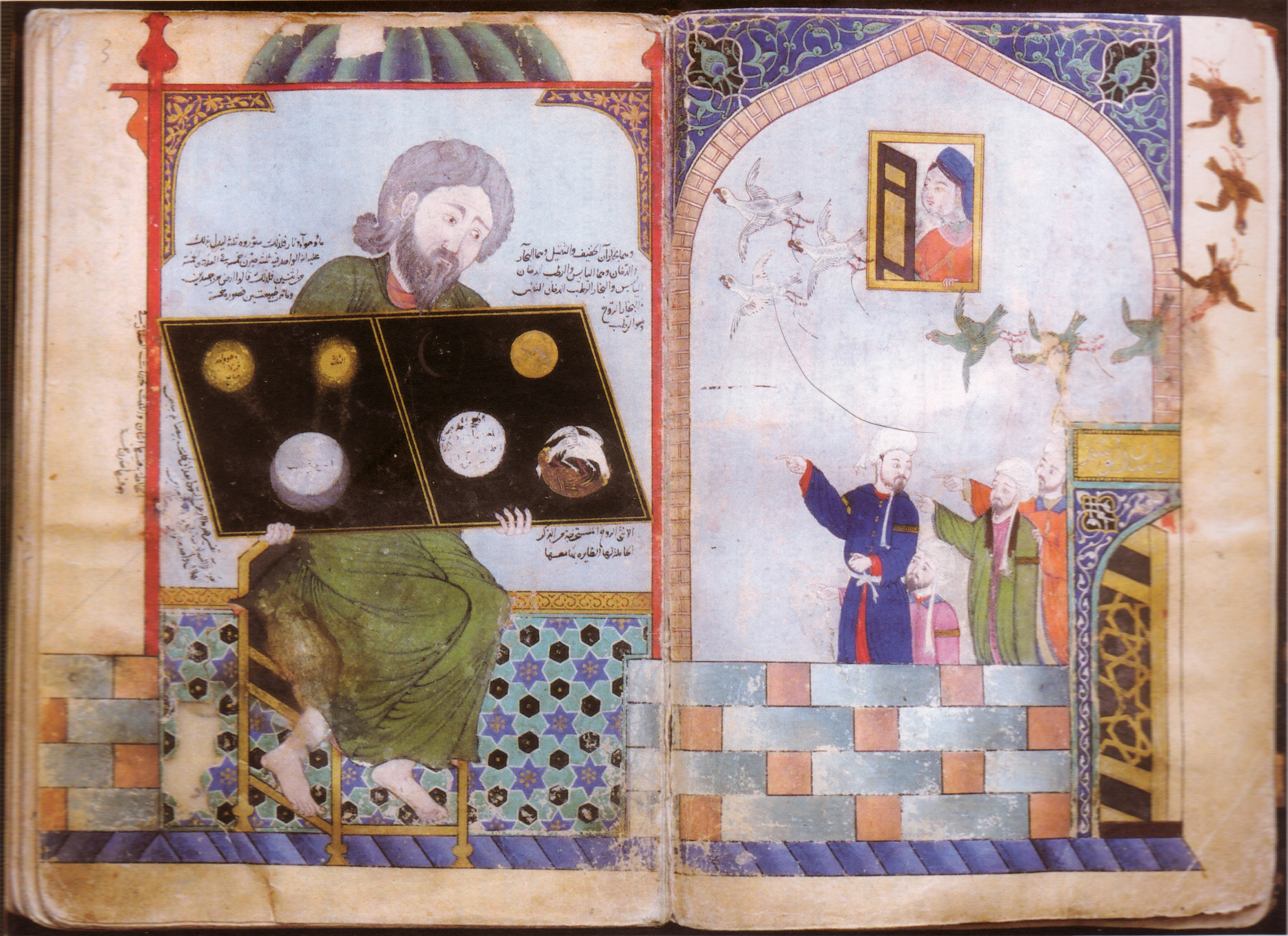

Similarly, an Arabic treatise called the ''Book of the Silvery Water and the Starry Earth'' by Ibn Umayl reproduces a version of the ''Tablet''. This treatise was translated as ''.'' In this version of the frame story, an alchemical stone table is discovered, resting on the knees of Hermes Trismegistus in the secret chamber of a pyramid. However, this table does not contain the ''Tablet'' text which is repeated later in the treatise. It is instead inscribed with writing described as . Its "hieroglyphic" contents are then visually depicted together with an alchemical exegesis thereof.

The literary theme of the discovery of Hermes' hidden wisdom can be found in other Arabic texts from around the tenth century. The introduction of the Book of Crates provides one such example. In the narrative a Greek philosopher named Crates is praying in the temple ''Sarapieion''. While in prayer he has a vision of the ancient sage. It reads:

Similarly, an Arabic treatise called the ''Book of the Silvery Water and the Starry Earth'' by Ibn Umayl reproduces a version of the ''Tablet''. This treatise was translated as ''.'' In this version of the frame story, an alchemical stone table is discovered, resting on the knees of Hermes Trismegistus in the secret chamber of a pyramid. However, this table does not contain the ''Tablet'' text which is repeated later in the treatise. It is instead inscribed with writing described as . Its "hieroglyphic" contents are then visually depicted together with an alchemical exegesis thereof.

The literary theme of the discovery of Hermes' hidden wisdom can be found in other Arabic texts from around the tenth century. The introduction of the Book of Crates provides one such example. In the narrative a Greek philosopher named Crates is praying in the temple ''Sarapieion''. While in prayer he has a vision of the ancient sage. It reads:

The ''Book of the Secret of Creation'' was translated into Latin' in by Hugo of Santalla. This text does not appear to have been widely circulated. Its translation of the ''Tablet'' reads as follows:

The ''Book of the Secret of Creation'' was translated into Latin' in by Hugo of Santalla. This text does not appear to have been widely circulated. Its translation of the ''Tablet'' reads as follows:

The ''Tablet'' was also translated into Latin as part of the thirteenth-century translation of the ''Secret of Secrets'' () by

The ''Tablet'' was also translated into Latin as part of the thirteenth-century translation of the ''Secret of Secrets'' () by

A third Latin version can be found in an alchemical treatise likely from the twelfth century. This latter, most circulated version is called the ''vulgate'', as it was widespread and formed the subsequent basis for all later editions and translations into European vernacular languages. It is found in an anonymous compilation of commentaries on the ''Emerald Tablet,'' translated from a lost Arabic text–variously called the ''Book of Hermes on Alchemy'', the ''Book of Dabessus'', or the ''Book of the Rebis''. Its translator has been tentatively identified as Plato of Tivoli, who was active in . However, this is merely conjecture, and although it can be deduced from other indices that the text dates to the first half of the twelfth century, its translator remains unknown.

Its translation of the ''Tablet'' reads:

The translator of this version did not understand the and therefore merely transcribed it into Latin as ''telesmus'' or ''telesmum''. This accidental neologism was variously interpreted by commentators, thereby becoming one of the most distinctive, yet ambiguous, terms of alchemy. The word is of Greek origin, from . The obscurity of this word's meaning brought forth many interpretations. In the ''Book of Hermes on Alchemy'' the cryptic ''telesmus'' line was left out entirely. The vulgate's final line referring to the ''operation of Sol'' is commonly interpreted as a reference to the alchemical ''Great Work''. The ''Emerald Tablet'' was seen as a summary of alchemical principles, wherein the secrets of the

A third Latin version can be found in an alchemical treatise likely from the twelfth century. This latter, most circulated version is called the ''vulgate'', as it was widespread and formed the subsequent basis for all later editions and translations into European vernacular languages. It is found in an anonymous compilation of commentaries on the ''Emerald Tablet,'' translated from a lost Arabic text–variously called the ''Book of Hermes on Alchemy'', the ''Book of Dabessus'', or the ''Book of the Rebis''. Its translator has been tentatively identified as Plato of Tivoli, who was active in . However, this is merely conjecture, and although it can be deduced from other indices that the text dates to the first half of the twelfth century, its translator remains unknown.

Its translation of the ''Tablet'' reads:

The translator of this version did not understand the and therefore merely transcribed it into Latin as ''telesmus'' or ''telesmum''. This accidental neologism was variously interpreted by commentators, thereby becoming one of the most distinctive, yet ambiguous, terms of alchemy. The word is of Greek origin, from . The obscurity of this word's meaning brought forth many interpretations. In the ''Book of Hermes on Alchemy'' the cryptic ''telesmus'' line was left out entirely. The vulgate's final line referring to the ''operation of Sol'' is commonly interpreted as a reference to the alchemical ''Great Work''. The ''Emerald Tablet'' was seen as a summary of alchemical principles, wherein the secrets of the

The 1541

The 1541

Hellenistic

In classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Greek history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the death of Cleopatra VII in 30 BC, which was followed by the ascendancy of the R ...

figure Hermes Trismegistus

Hermes Trismegistus (from , "Hermes the Thrice-Greatest") is a legendary Hellenistic period figure that originated as a syncretic combination of the Greek god Hermes and the Egyptian god Thoth.A survey of the literary and archaeological eviden ...

. The earliest known versions are four Arabic

Arabic (, , or , ) is a Central Semitic languages, Central Semitic language of the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family spoken primarily in the Arab world. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) assigns lang ...

recensions preserved in mystical and alchemical treatises between the 8th and 10th centuries CE—chiefly the '' Secret of Creation'' () and the '' Secret of Secrets'' (). It was often accompanied by a frame story about the discovery of an emerald

Emerald is a gemstone and a variety of the mineral beryl (Be3Al2(SiO3)6) colored green by trace amounts of chromium or sometimes vanadium.Hurlbut, Cornelius S. Jr., and Kammerling, Robert C. (1991). ''Gemology'', John Wiley & Sons, New York ...

tablet in Hermes' tomb.

From the 12th century onward, Latin translations—most notably the widespread so-called ''vulgate''—introduced the text to Europe, where it attracted great scholarly interest. Medieval commentators such as Hortulanus interpreted it as a "foundational text" of alchemical instructions for producing the philosopher's stone

The philosopher's stone is a mythic alchemical substance capable of turning base metals such as mercury into gold or silver; it was also known as "the tincture" and "the powder". Alchemists additionally believed that it could be used to mak ...

and making gold. During the Renaissance, interpreters increasingly read the text through Neoplatonic

Neoplatonism is a version of Platonic philosophy that emerged in the 3rd century AD against the background of Hellenistic philosophy and religion. The term does not encapsulate a set of ideas as much as a series of thinkers. Among the common id ...

, allegorical, and Christian lenses; and printers often paired it with an emblem that came to be regarded as a visual representation of the ''Tablet'' itself.

Following the 20th-century rediscovery of Arabic sources by Julius Ruska and Eric Holmyard, modern scholars continue to debate its origins. They agree that the ''Secret of Creation'', the ''Tablets earliest source and its likely original context, was either wholly or at least partly compiled from earlier Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

or Syriac materials. The ''Tablet'' remains influential in esotericism and occultism, where the phrase ''as above, so below

"As above, so below" is a popular modern paraphrase of the second verse of the ''Emerald Tablet,'' a short Hermetica, Hermetic text which first appeared in an Arabic source from the late eighth or early ninth century. The paraphrase is based on ...

'' (a paraphrase of its second verse) has become a popular maxim

Maxim or Maksim may refer to:

Entertainment

*Maxim (magazine), ''Maxim'' (magazine), an international men's magazine

** Maxim (Australia), ''Maxim'' (Australia), the Australian edition

** Maxim (India), ''Maxim'' (India), the Indian edition

*Maxim ...

. It has also been taken up by Jungian psychologists

Analytical psychology (, sometimes translated as analytic psychology; also Jungian analysis) is a term referring to the psychology, psychological practices of Carl Jung. It was designed to distinguish it from Freud's psychoanalytic theories ...

, artists, and figures of pop culture, cementing its status as one of the best-known Hermetica

The ''Hermetica'' are texts attributed to the legendary Hellenistic figure Hermes Trismegistus, a syncretic combination of the Greek god Hermes and the Egyptian god Thoth. These texts may vary widely in content and purpose, but by modern con ...

.

Background and early Arabic versions

Beginning from the first century BCE onwards, Greek texts attributed toHermes Trismegistus

Hermes Trismegistus (from , "Hermes the Thrice-Greatest") is a legendary Hellenistic period figure that originated as a syncretic combination of the Greek god Hermes and the Egyptian god Thoth.A survey of the literary and archaeological eviden ...

, a syncretic combination of the Greek god Hermes

Hermes (; ) is an Olympian deity in ancient Greek religion and mythology considered the herald of the gods. He is also widely considered the protector of human heralds, travelers, thieves, merchants, and orators. He is able to move quic ...

and the Egyptian god Thoth

Thoth (from , borrowed from , , the reflex of " eis like the ibis") is an ancient Egyptian deity. In art, he was often depicted as a man with the head of an African sacred ibis, ibis or a baboon, animals sacred to him. His feminine count ...

, appeared in Greco-Roman Egypt. These texts, known as the Hermetica

The ''Hermetica'' are texts attributed to the legendary Hellenistic figure Hermes Trismegistus, a syncretic combination of the Greek god Hermes and the Egyptian god Thoth. These texts may vary widely in content and purpose, but by modern con ...

, are a heterogeneous collection of works that in the modern day are commonly subdivided into two groups: the technical Hermetica, comprising astrological

Astrology is a range of divinatory practices, recognized as pseudoscientific since the 18th century, that propose that information about human affairs and terrestrial events may be discerned by studying the apparent positions of celesti ...

, medico-botanical, alchemical, and magical writings; and the religio-philosophical Hermetica, comprising mystical-philosophical writings.

These Greek pseudepigraphal texts found receptions, translations, and imitations in Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

, Syriac, Coptic, Armenian

Armenian may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to Armenia, a country in the South Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Armenians, the national people of Armenia, or people of Armenian descent

** Armenian diaspora, Armenian communities around the ...

, and Middle Persian

Middle Persian, also known by its endonym Pārsīk or Pārsīg ( Inscriptional Pahlavi script: , Manichaean script: , Avestan script: ) in its later form, is a Western Middle Iranian language which became the literary language of the Sasania ...

prior to the emergence of Islam and the Arab conquests in the 630s. These conquests brought about various empires in which a new group of Arabic-speaking intellectuals emerged. These scholars received and translated the aforementioned wealth of texts and also began producing Hermetica of their own. By the tenth century, some Arabic-speaking Muslims

Muslims () are people who adhere to Islam, a Monotheism, monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God ...

had come to identify Hermes with the prophet Idris

Idris may refer to:

People

* Idris (name), a list of people and fictional characters with the given name or surname

* Idris (prophet), Islamic prophet in the Qur'an, traditionally identified with Enoch, an ancestor of Noah in the Bible

* Idris ...

, thereby elevating the Hermetica to the level of other Islamic prophetic revelations. Until the early twentieth century, only Latin versions of the ''Emerald Tablet'' were known in the Western world

The Western world, also known as the West, primarily refers to various nations and state (polity), states in Western Europe, Northern America, and Australasia; with some debate as to whether those in Eastern Europe and Latin America also const ...

, with the oldest dating back to the twelfth century. The older Arabic versions were rediscovered by Eric John Holmyard and Julius Ruska.

''Secret of Creation''

The oldest version of the ''Emerald Tablet'' is found as an appendix in an encyclopaedic treatise on natural philosophy meant as a

The oldest version of the ''Emerald Tablet'' is found as an appendix in an encyclopaedic treatise on natural philosophy meant as a cosmogony

Cosmogony is any model concerning the origin of the cosmos or the universe.

Overview

Scientific theories

In astronomy, cosmogony is the study of the origin of particular astrophysical objects or systems, and is most commonly used in ref ...

. It is believed to have been compiled in Arabic in the late eighth or early ninth century. The treatise bears the title '' Book of the Secret of Creation and the Craft of Nature''. Some scholars consider it plausible that this work is a translation of a much older Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

or Syriac original, although no such manuscript is known. At the same time others think it is more likely that it was an original Arabic composition based on older materials. The Arabic text presents itself as a translation of a work by Apollonius of Tyana

Apollonius of Tyana (; ; ) was a Greek philosopher and religious leader from the town of Tyana, Cappadocia in Roman Anatolia, who spent his life travelling and teaching in the Middle East, North Africa and India. He is a central figure in Ne ...

. Pseudepigraphal attributions to Apollonius were common in medieval Arabic texts on magic, astrology, and alchemy. If the ''Tablet'' originally hailed from a pseudo-Apollonian context, it could be considered a text of late antiquity

Late antiquity marks the period that comes after the end of classical antiquity and stretches into the onset of the Early Middle Ages. Late antiquity as a period was popularized by Peter Brown (historian), Peter Brown in 1971, and this periodiza ...

, like other such works.

This earliest known version reads as follows:

The introduction to the ''Book of the Secret of Creation'' presents a narrative that outlines key philosophical and alchemical ideas. It explains that all things are composed of four elemental qualities—heat, cold, moisture, and dryness—drawn from Aristotelian theory. These elements and their combinations are said to determine the sympathetic or antagonistic relationships between beings. In the frame story

A frame story (also known as a frame tale, frame narrative, sandwich narrative, or intercalation) is a literary technique that serves as a companion piece to a story within a story, where an introductory or main narrative sets the stage either fo ...

, Balīnūs, a legendary figure known as the ''Master of Talismans'', discovers a crypt beneath a statue of Hermes Trismegistus. Inside, he finds a tablet made of emerald

Emerald is a gemstone and a variety of the mineral beryl (Be3Al2(SiO3)6) colored green by trace amounts of chromium or sometimes vanadium.Hurlbut, Cornelius S. Jr., and Kammerling, Robert C. (1991). ''Gemology'', John Wiley & Sons, New York ...

, held by an old man seated with a book. The central part of the text is an alchemical treatise, notable for introducing—for the first time—the theory that all metals are formed from two basic substances: sulphur

Sulfur (American spelling and the preferred IUPAC name) or sulphur (English in the Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth spelling) is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol S and atomic number 16. It is abundance of the chemical ...

and mercury. This concept later became a foundational idea in medieval alchemy. Emerald

Emerald is a gemstone and a variety of the mineral beryl (Be3Al2(SiO3)6) colored green by trace amounts of chromium or sometimes vanadium.Hurlbut, Cornelius S. Jr., and Kammerling, Robert C. (1991). ''Gemology'', John Wiley & Sons, New York ...

was the stone traditionally associated with Hermes, while quicksilver was his metal and Mercury his planet. Mars

Mars is the fourth planet from the Sun. It is also known as the "Red Planet", because of its orange-red appearance. Mars is a desert-like rocky planet with a tenuous carbon dioxide () atmosphere. At the average surface level the atmosph ...

was associated with red stones and iron

Iron is a chemical element; it has symbol Fe () and atomic number 26. It is a metal that belongs to the first transition series and group 8 of the periodic table. It is, by mass, the most common element on Earth, forming much of Earth's o ...

, and Saturn

Saturn is the sixth planet from the Sun and the second largest in the Solar System, after Jupiter. It is a gas giant, with an average radius of about 9 times that of Earth. It has an eighth the average density of Earth, but is over 95 tim ...

with black stones and lead

Lead () is a chemical element; it has Chemical symbol, symbol Pb (from Latin ) and atomic number 82. It is a Heavy metal (elements), heavy metal that is density, denser than most common materials. Lead is Mohs scale, soft and Ductility, malleabl ...

. People in antiquity thought of various green-coloured minerals—such as green jasper

Jasper, an aggregate of microgranular quartz and/or cryptocrystalline chalcedony and other mineral phases, is an opaque, impure variety of silica, usually red, yellow, brown or green in color; and rarely blue. The common red color is due to ...

and even green granite

Granite ( ) is a coarse-grained (phanerite, phaneritic) intrusive rock, intrusive igneous rock composed mostly of quartz, alkali feldspar, and plagioclase. It forms from magma with a high content of silica and alkali metal oxides that slowly coo ...

—as emerald.

The text of the ''Emerald Tablet'' appears in the ''Book of the Secret of Creation'' as an appendix. It has long been debated whether it is an extraneous piece, solely cosmogonic in nature, or whether it is an integral part of the rest of the work, in which case it could have had an alchemical significance from the outset. It has been suggested that the ''Emerald Tablet'' was originally a text of talismanic magic that was only later understood as being alchemical in nature. This may have been due to it having been divorced from its original context in the ''Book of the Secret of Creation''; and instead having been commonly transmitted through the alchemical treatise containing the ''vulgate''.

Julius Ruska observed that the ''Tablet''Iranian

Iranian () may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to Iran

** Iranian diaspora, Iranians living outside Iran

** Iranian architecture, architecture of Iran and parts of the rest of West Asia

** Iranian cuisine, cooking traditions and practic ...

, nor Christian. He speculated that it might reflect Chaldean, Harranian, or gnostic

Gnosticism (from Ancient Greek: , romanized: ''gnōstikós'', Koine Greek: �nostiˈkos 'having knowledge') is a collection of religious ideas and systems that coalesced in the late 1st century AD among early Christian sects. These diverse g ...

ideas from the regions northeast of Iran, along the Silk Road

The Silk Road was a network of Asian trade routes active from the second century BCE until the mid-15th century. Spanning over , it played a central role in facilitating economic, cultural, political, and religious interactions between the ...

. Chang Tzu-Kung proposed an origin further east—as he believed Hermes Trismegistus to have been Chinese. He noted that Chinese aphorisms

An aphorism (from Greek ἀφορισμός: ''aphorismos'', denoting 'delimitation', 'distinction', and 'definition') is a concise, terse, laconic, or memorable expression of a general truth or principle. Aphorisms are often handed down by tra ...

commonly hailed from legendary slabs and steles in caves and temples. Tzu-Kung produced a speculative Chinese rendition of the ''Tablet'', which he based on John Read's ''vulgate'' translation.' He then claimed the ''Tablets origin to be a Han dynasty

The Han dynasty was an Dynasties of China, imperial dynasty of China (202 BC9 AD, 25–220 AD) established by Liu Bang and ruled by the House of Liu. The dynasty was preceded by the short-lived Qin dynasty (221–206 BC ...

(202 BCE – 220 CE) Taoist

Taoism or Daoism (, ) is a diverse philosophical and religious tradition indigenous to China, emphasizing harmony with the Tao ( zh, p=dào, w=tao4). With a range of meaning in Chinese philosophy, translations of Tao include 'way', 'road', ...

text known as the ''Guanzi''. Joseph Needham

Noel Joseph Terence Montgomery Needham (; 9 December 1900 – 24 March 1995) was a British biochemist, historian of science and sinologist known for his scientific research and writing on the history of Chinese science and technology, initia ...

rejected this theory as not yet having been sufficiently proved.

Jabir ibn Hayyan

Another early version of the ''Emerald Tablet'' is found in the ''Second Book of the Element of the Foundation'' () attributed to the eighth-century alchemistJabir ibn Hayyan

Abū Mūsā Jābir ibn Ḥayyān (Arabic: , variously called al-Ṣūfī, al-Azdī, al-Kūfī, or al-Ṭūsī), died 806−816, is the purported author of a large number of works in Arabic, often called the Jabirian corpus. The treatises that ...

. In this somewhat shorter version, lines 6, 8, and 11–15 as found in the ''Secret of Creation'' are missing. Other parts appear to be corrupt. It reads:

''Secret of Secrets''

Another text of the ''Emerald Tablet'' is found towards the end of the tenth-century

Another text of the ''Emerald Tablet'' is found towards the end of the tenth-century pseudo-Aristotelian

Pseudo-Aristotle is a general cognomen for authors of philosophical or medical treatises who attributed their works to the Greek philosopher Aristotle, or whose work was later attributed to him by others. Such falsely attributed works are known as ...

work known as the ''Secret of Secrets''. This entire treatise is framed as a pseudepigraphic

A pseudepigraph (also :wikt:anglicized, anglicized as "pseudepigraphon") is a false attribution, falsely attributed work, a text whose claimed author is not the true author, or a work whose real author attributed it to a figure of the past. Th ...

al letter from Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

to Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon (; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), most commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia (ancient kingdom), Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip ...

during the latter's conquest of Persia and is introduced via a number of letters between the two. It discusses politics, morality, physiognomy

Physiognomy () or face reading is the practice of assessing a person's character or personality from their outer appearance—especially the face. The term can also refer to the general appearance of a person, object, or terrain without referenc ...

, astrology, alchemy, medicine, and more.

It reads:

Ibn Umayl

Similarly, an Arabic treatise called the ''Book of the Silvery Water and the Starry Earth'' by Ibn Umayl reproduces a version of the ''Tablet''. This treatise was translated as ''.'' In this version of the frame story, an alchemical stone table is discovered, resting on the knees of Hermes Trismegistus in the secret chamber of a pyramid. However, this table does not contain the ''Tablet'' text which is repeated later in the treatise. It is instead inscribed with writing described as . Its "hieroglyphic" contents are then visually depicted together with an alchemical exegesis thereof.

The literary theme of the discovery of Hermes' hidden wisdom can be found in other Arabic texts from around the tenth century. The introduction of the Book of Crates provides one such example. In the narrative a Greek philosopher named Crates is praying in the temple ''Sarapieion''. While in prayer he has a vision of the ancient sage. It reads:

Similarly, an Arabic treatise called the ''Book of the Silvery Water and the Starry Earth'' by Ibn Umayl reproduces a version of the ''Tablet''. This treatise was translated as ''.'' In this version of the frame story, an alchemical stone table is discovered, resting on the knees of Hermes Trismegistus in the secret chamber of a pyramid. However, this table does not contain the ''Tablet'' text which is repeated later in the treatise. It is instead inscribed with writing described as . Its "hieroglyphic" contents are then visually depicted together with an alchemical exegesis thereof.

The literary theme of the discovery of Hermes' hidden wisdom can be found in other Arabic texts from around the tenth century. The introduction of the Book of Crates provides one such example. In the narrative a Greek philosopher named Crates is praying in the temple ''Sarapieion''. While in prayer he has a vision of the ancient sage. It reads:

European medieval period

''On the Secrets of Nature''

The ''Book of the Secret of Creation'' was translated into Latin' in by Hugo of Santalla. This text does not appear to have been widely circulated. Its translation of the ''Tablet'' reads as follows:

The ''Book of the Secret of Creation'' was translated into Latin' in by Hugo of Santalla. This text does not appear to have been widely circulated. Its translation of the ''Tablet'' reads as follows:

''Secret of Secrets''

The ''Tablet'' was also translated into Latin as part of the thirteenth-century translation of the ''Secret of Secrets'' () by

The ''Tablet'' was also translated into Latin as part of the thirteenth-century translation of the ''Secret of Secrets'' () by Philip of Tripoli

Philip of Tripoli, sometimes Philippus Tripolitanus or Philip of Foligno (floruit, fl. 1218–1269), was an Italian Catholic priest and translator. Although he had a markedly successful clerical career, his most enduring legacy is his translation ...

. This entire treatise has been called "the most popular book of the Latin Middle Ages". Its translation of the ''Tablet'' differs significantly from both Hugo of Santalla's version and the ''vulgate'' translation. In Roger Bacon

Roger Bacon (; or ', also '' Rogerus''; ), also known by the Scholastic accolades, scholastic accolade ''Doctor Mirabilis'', was a medieval English polymath, philosopher, scientist, theologian and Franciscans, Franciscan friar who placed co ...

's 1255 edition it reads: ''Vulgate''

A third Latin version can be found in an alchemical treatise likely from the twelfth century. This latter, most circulated version is called the ''vulgate'', as it was widespread and formed the subsequent basis for all later editions and translations into European vernacular languages. It is found in an anonymous compilation of commentaries on the ''Emerald Tablet,'' translated from a lost Arabic text–variously called the ''Book of Hermes on Alchemy'', the ''Book of Dabessus'', or the ''Book of the Rebis''. Its translator has been tentatively identified as Plato of Tivoli, who was active in . However, this is merely conjecture, and although it can be deduced from other indices that the text dates to the first half of the twelfth century, its translator remains unknown.

Its translation of the ''Tablet'' reads:

The translator of this version did not understand the and therefore merely transcribed it into Latin as ''telesmus'' or ''telesmum''. This accidental neologism was variously interpreted by commentators, thereby becoming one of the most distinctive, yet ambiguous, terms of alchemy. The word is of Greek origin, from . The obscurity of this word's meaning brought forth many interpretations. In the ''Book of Hermes on Alchemy'' the cryptic ''telesmus'' line was left out entirely. The vulgate's final line referring to the ''operation of Sol'' is commonly interpreted as a reference to the alchemical ''Great Work''. The ''Emerald Tablet'' was seen as a summary of alchemical principles, wherein the secrets of the

A third Latin version can be found in an alchemical treatise likely from the twelfth century. This latter, most circulated version is called the ''vulgate'', as it was widespread and formed the subsequent basis for all later editions and translations into European vernacular languages. It is found in an anonymous compilation of commentaries on the ''Emerald Tablet,'' translated from a lost Arabic text–variously called the ''Book of Hermes on Alchemy'', the ''Book of Dabessus'', or the ''Book of the Rebis''. Its translator has been tentatively identified as Plato of Tivoli, who was active in . However, this is merely conjecture, and although it can be deduced from other indices that the text dates to the first half of the twelfth century, its translator remains unknown.

Its translation of the ''Tablet'' reads:

The translator of this version did not understand the and therefore merely transcribed it into Latin as ''telesmus'' or ''telesmum''. This accidental neologism was variously interpreted by commentators, thereby becoming one of the most distinctive, yet ambiguous, terms of alchemy. The word is of Greek origin, from . The obscurity of this word's meaning brought forth many interpretations. In the ''Book of Hermes on Alchemy'' the cryptic ''telesmus'' line was left out entirely. The vulgate's final line referring to the ''operation of Sol'' is commonly interpreted as a reference to the alchemical ''Great Work''. The ''Emerald Tablet'' was seen as a summary of alchemical principles, wherein the secrets of the philosopher's stone

The philosopher's stone is a mythic alchemical substance capable of turning base metals such as mercury into gold or silver; it was also known as "the tincture" and "the powder". Alchemists additionally believed that it could be used to mak ...

were thought to have been described. This belief led to its consequent popularity and the wide array of European translations of and commentaries on the text, beginning in the High Middle Ages

The High Middle Ages, or High Medieval Period, was the periodization, period of European history between and ; it was preceded by the Early Middle Ages and followed by the Late Middle Ages, which ended according to historiographical convention ...

and persisting to the present.

Commentaries

Herman of Carinthia

Herman of Carinthia (1105/1110 – after 1154), also called Hermanus Dalmata or Sclavus Dalmata, Secundus, by his own words born in the "heart of Istria", was a philosopher, astronomer, astrologer, mathematician and translator of Arabic works int ...

was one of a few European twelfth-century scholars to cite the ''Emerald Tablet''. He did so in his 1143 treatise ''On Essences,'' where he also recalled the frame story of the tablet's discovery under a statue of Hermes in a cave, from the ''Book of the Secret of Creation.'' Carinthia was a friend of Robert of Chester, who in 1144 translated the '' Book on the Composition of Alchemy'', which is generally considered to be the first Latin translation of an Arabic treatise on alchemy. An anonymous twelfth-century commentator tried to explain the aforementioned neologism ''telesmus'' in the phrase by claiming it is synonymous with . The translator followed this claim with the assertion that a kind of divination, which is "superior to all others" among the Arabs is called . In subsequent commentaries on the ''Emerald Tablet'' only the meaning of ''secret'' was retained. ''On Minerals'' written around 1250 by Albertus Magnus

Albertus Magnus ( 1200 – 15 November 1280), also known as Saint Albert the Great, Albert of Swabia, Albert von Bollstadt, or Albert of Cologne, was a German Dominican friar, philosopher, scientist, and bishop, considered one of the great ...

comments on the vulgate ''Tablet''. Roger Bacon

Roger Bacon (; or ', also '' Rogerus''; ), also known by the Scholastic accolades, scholastic accolade ''Doctor Mirabilis'', was a medieval English polymath, philosopher, scientist, theologian and Franciscans, Franciscan friar who placed co ...

translated and annotated the ''Secret of Secrets'' around 1275–1280''.'' He thought it an authentic work of Aristotle and it greatly influenced his thought. He cited it constantly, from his earliest writings to his last''.'' The most widespread commentary accompanying the text of the ''Emerald Tablet'' is that of Hortulanus. He was an alchemist, who was likely active in the first half of the fourteenth century, about whom very little is known except for what he states about himself in the introduction of the text. Hortulanus, like Albertus Magnus before him, saw the tablet as a cryptic recipe that described laboratory processes using " deck names". This was the dominant view held by Europeans until the fifteenth century. In his commentary, Hortulanus, again like Albertus Magnus, interpreted the sun and moon to represent alchemical gold and silver. Hortulanus translated "telesma" as "secret" or "treasure".

From around 1420, the ''Rising Dawn'' introduced one of the earliest European cycles of alchemical imagery, combining complex metaphors with the motif of glass vessels. Its illustrations depict symbolic operations such as putrefaction

Putrefaction is the fifth stage of death, following pallor mortis, livor mortis, algor mortis, and rigor mortis. This process references the breaking down of a body of an animal Post-mortem interval, post-mortem. In broad terms, it can be view ...

, sublimation, and the union of opposites through figures like Mercury, the sun and moon, dragons, and eagles. These images reflect philosophical principles including “two are one” and “nature vanquishes nature”. Drawing on late antique traditions preserved in Ibn Umayl's ''Book of the Silvery Water and the Starry Earth'', the manuscript visualises the myth of the rediscovery of Hermetic knowledge, portraying hieroglyphic signs as divinely instituted symbols immune to verbal distortion. The ''Rising Dawn'' thus helped establish the Renaissance notion of alchemical imagery as a medium for transmitting original wisdom through visual, rather than textual, means.

Renaissance and early modernity

During theRenaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) is a Periodization, period of history and a European cultural movement covering the 15th and 16th centuries. It marked the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and was characterized by an effort to revive and sur ...

, Hermes Trismegistus was widely regarded as the founder of alchemy and native to Babylon

Babylon ( ) was an ancient city located on the lower Euphrates river in southern Mesopotamia, within modern-day Hillah, Iraq, about south of modern-day Baghdad. Babylon functioned as the main cultural and political centre of the Akkadian-s ...

. He was thought to be a contemporary of Noah

Noah (; , also Noach) appears as the last of the Antediluvian Patriarchs (Bible), patriarchs in the traditions of Abrahamic religions. His story appears in the Hebrew Bible (Book of Genesis, chapters 5–9), the Quran and Baháʼí literature, ...

or Moses

In Abrahamic religions, Moses was the Hebrews, Hebrew prophet who led the Israelites out of slavery in the The Exodus, Exodus from ancient Egypt, Egypt. He is considered the most important Prophets in Judaism, prophet in Judaism and Samaritani ...

and his legend became intertwined with biblical narratives. One illustrative example of the belief that Hermes invented alchemy is found in the anonymous text ''Who Were the First Inventors of this Art'', extracted from a gloss of the fourteenth-century ''Textus Alkimie''. This text or a later French one, incorporating much of its narrative, influenced another discovery legend claiming the tablet (and its ''emblem'') to have been discovered after the Biblical Flood

The Genesis flood narrative (chapters 6–9 of the Book of Genesis) is a Hebrew flood myth. It tells of God's decision to return the universe to its pre- creation state of watery chaos and remake it through the microcosm of Noah's ark.

The Bo ...

in Hebron

Hebron (; , or ; , ) is a Palestinian city in the southern West Bank, south of Jerusalem. Hebron is capital of the Hebron Governorate, the largest Governorates of Palestine, governorate in the West Bank. With a population of 201,063 in ...

Valley.

The narrative further evolved via Hieronymus Torrella's 1496 ''Splendid Work of Astrological Images''. In it, Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon (; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), most commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia (ancient kingdom), Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip ...

discovers a in Hermes' tomb while travelling to the Oracle of Amun in Egypt. This story is repeated in 1617 by Michael Maier

Michael Maier (; 1568–1622) was a German physician and counsellor to Rudolf II, Holy Roman Emperor, Rudolf II Habsburg. He was a learned Alchemy, alchemist, epigramist, and amateur composer.

Early life

Maier was born in Rendsburg, Duchy of ...

in ''Symbols of the Golden Table'', referencing a ''Book of Chymical Secrets'' attributed to, but likely not written by, Albertus Magnus

Albertus Magnus ( 1200 – 15 November 1280), also known as Saint Albert the Great, Albert of Swabia, Albert von Bollstadt, or Albert of Cologne, was a German Dominican friar, philosopher, scientist, and bishop, considered one of the great ...

. That same year, he published ''Fleeing Atalanta''. It was illustrated by Matthaeus Merian the Elder, possibly with cooperation from his cousin Theodor de Bry

Theodor de Bry (also Theodorus de Bry) (152827 March 1598) was an engraver, goldsmith, Editing, editor and publisher, famous for his depictions of early European colonization of the Americas, European expeditions to the Americas. The Spanish In ...

, with fifty alchemical emblems, each accompanied by a poem, the score of a fugue

In classical music, a fugue (, from Latin ''fuga'', meaning "flight" or "escape""Fugue, ''n''." ''The Concise Oxford English Dictionary'', eleventh edition, revised, ed. Catherine Soanes and Angus Stevenson (Oxford and New York: Oxford Universit ...

, and alchemical and mythological explanations. Among them were ones depicting verses from the ''Tablet''.

The first printed edition of the ''Emerald Tablet'' appeared in 1541, in ''Of Alchemy''. It was published in Nuremberg

Nuremberg (, ; ; in the local East Franconian dialect: ''Nämberch'' ) is the Franconia#Towns and cities, largest city in Franconia, the List of cities in Bavaria by population, second-largest city in the States of Germany, German state of Bav ...

by Johann Petreius and edited by a certain Chrysogonus Polydorus. Polydorus is likely a pseudonym used by the Lutheran theologian Andreas Osiander, who edited Copernicus

Nicolaus Copernicus (19 February 1473 – 24 May 1543) was a Renaissance polymath who formulated a mathematical model, model of Celestial spheres#Renaissance, the universe that placed heliocentrism, the Sun rather than Earth at its cen ...

' ''On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres

''De revolutionibus orbium coelestium'' (English translation: ''On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres'') is the seminal work on the Copernican heliocentrism, heliocentric theory of the astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus (1473–1543) of the Rena ...

'' in 1543, also published by Petreius. This edition, which is similar to the ''vulgate'' version, is accompanied by Hortulanus' commentary.

By the early sixteenth century, the writings of Johannes Trithemius

Johannes Trithemius (; 1 February 1462 – 13 December 1516), born Johann Heidenberg, was a German Benedictine abbot and a polymath who was active in the German Renaissance as a Lexicography, lexicographer, chronicler, Cryptography, cryptograph ...

marked a shift away from a laboratory interpretation of the ''Emerald Tablet'', to a metaphysical approach. Trithemius equated Hermes' ''one thing'' with the monad

Monad may refer to:

Philosophy

* Monad (philosophy), a term meaning "unit"

**Monism, the concept of "one essence" in the metaphysical and theological theory

** Monad (Gnosticism), the most primal aspect of God in Gnosticism

* ''Great Monad'', an ...

of Pythagorean

Pythagorean, meaning of or pertaining to the ancient Ionian mathematician, philosopher, and music theorist Pythagoras, may refer to:

Philosophy

* Pythagoreanism, the esoteric and metaphysical beliefs purported to have been held by Pythagoras

* Ne ...

philosophy and the anima mundi

The concept of the (Latin), world soul (, ), or soul of the world (, ) posits an intrinsic connection between all living beings, suggesting that the world is animated by a soul much like the human body. Rooted in ancient Greek and Roman philo ...

. This interpretation of the Hermetic text was adopted by alchemists such as John Dee

John Dee (13 July 1527 – 1608 or 1609) was an English mathematician, astronomer, teacher, astrologer, occultist, and alchemist. He was the court astronomer for, and advisor to, Elizabeth I, and spent much of his time on alchemy, divination, ...

, Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa

Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa von Nettesheim (; ; 14 September 1486 – 18 February 1535) was a German Renaissance polymath, physician, legal scholar, soldier, knight, theologian, and occult writer. Agrippa's ''Three Books of Occult Philosophy'' pub ...

, and Gerhard Dorn

Gerhard Dorn (c. 1530 – 1584) was a philosopher, translator, alchemist, physician and bibliophile.

Biography

The details of Gerhard Dorn's early life, along with those of many other 16th century personalities, are lost to history. It is k ...

. In 1583, Dorn published ''On the Light of Physical Nature'' by Christoph Corvinus. This Paracelsian

Paracelsianism (also Paracelsism; German: ') was an early modern History of medicine, medical movement based on the theories and therapies of Paracelsus.

It developed in the second half of the 16th century, during the decades following Paracel ...

treatise drew up a detailed parallel between the Emerald Tablet and the Genesis creation narrative

The Genesis creation narrative is the creation myth of both Judaism and Christianity, told in the book of Genesis chapters 1 and 2. While the Jewish and Christian tradition is that the account is one comprehensive story, modern scholars of ...

.

Emblem

From the late sixteenth century onwards, the ''Emerald Tablet'' was often accompanied by a symbolic figure called . This figure is encircled by anacrostic

An acrostic is a poem or other word composition in which the ''first'' letter (or syllable, or word) of each new line (or paragraph, or other recurring feature in the text) spells out a word, message or the alphabet. The term comes from the Fre ...

in whose seven initials form the word . At the top, the sun and moon pour into a cup above the planetary symbol

Planetary symbols are used in astrological symbol, astrology and traditionally in astronomical symbol, astronomy to represent a classical planet (which includes the Sun and the Moon) or one of the modern planets. The classical symbols were also use ...

☿ representing Mercury. Surrounding this mercurial cup are the four other planets, representing the classic association between the seven planets and the seven metals. Though, many of the extant copies of the emblem are not set in colour, it was originally polychrome—linking each planetary-metallic pair with a specific colour, thus rendering: gold– Sol-gold, silver–Luna

Luna commonly refers to:

* Earth's Moon, named "Luna" in Latin, Spanish and other languages

* Luna (goddess)

In Sabine and ancient Roman religion and myth, Luna is the divine embodiment of the Moon (Latin ''Lūna'' ). She is often presented as t ...

–silver, grey– Mercury–quicksilver, blue–Jupiter

Jupiter is the fifth planet from the Sun and the List of Solar System objects by size, largest in the Solar System. It is a gas giant with a Jupiter mass, mass more than 2.5 times that of all the other planets in the Solar System combined a ...

–tin, red–Mars

Mars is the fourth planet from the Sun. It is also known as the "Red Planet", because of its orange-red appearance. Mars is a desert-like rocky planet with a tenuous carbon dioxide () atmosphere. At the average surface level the atmosph ...

–iron, green–Venus

Venus is the second planet from the Sun. It is often called Earth's "twin" or "sister" planet for having almost the same size and mass, and the closest orbit to Earth's. While both are rocky planets, Venus has an atmosphere much thicker ...

–copper, and black–Saturn

Saturn is the sixth planet from the Sun and the second largest in the Solar System, after Jupiter. It is a gas giant, with an average radius of about 9 times that of Earth. It has an eighth the average density of Earth, but is over 95 tim ...

–lead. At the centre are a ring and a globus cruciger

The for, la, globus cruciger, cross-bearing orb, also known as ''stavroforos sphaira'' () or "the orb and cross", is an Sphere, orb surmounted by a Christian cross, cross. It has been a Christian Church, Christian symbol of authority since the M ...

; at the bottom, the celestial and terrestrial spheres. Three charges represent, according to the accompanying poem, the '' three principles'' of Paracelsian alchemical theory: the eagle signifying quicksilver and the spirit, the lion signifying sulphur and the soul, and the star signifying salt and the body. Finally, two Schwurhand

The ''Schwurhand'' (, "Oath, swear-hand"; ) is a traditional List of gestures, hand gesture and heraldic Charge (heraldry), charge (depicting the gesture) that is used in Germanic peoples, Germanic Europe and neighbouring countries, when swearing ...

s appear alongside the image, affirming the creator’s veracity.

The oldest known printed reproduction of this emblem is found in the ''Golden Fleece'', attributed to Salomon Trismosin—likely a pseudonym

A pseudonym (; ) or alias () is a fictitious name that a person assumes for a particular purpose, which differs from their original or true meaning ( orthonym). This also differs from a new name that entirely or legally replaces an individual's o ...

employed by a German Paracelsian

Paracelsianism (also Paracelsism; German: ') was an early modern History of medicine, medical movement based on the theories and therapies of Paracelsus.

It developed in the second half of the 16th century, during the decades following Paracel ...

. Wherein the image was accompanied by a didactic alchemical poem in German titled (). This poem explained the emblem's symbolism in relation to the Great Work and the classical goals of alchemy: wealth, health, and long life. The emblem is largely derivative. The colours, symbols and associations are all found in different Paracelsian works from the same period and unlikely to be influenced by the ''Tablet'' itself. The association with the cryptic text might have served primarily as a legitimation for an artwork also meant to be read metaphorically. Additionally, the image first spread in the circle of Karl Widemann, a known Paracelsian mystifier. Initially, the image was presented alongside the ''Emerald Tablet'' as a merely ancillary element. However, in printed editions of the seventeenth century, the poem was omitted, and the emblem came to be known as the symbolic or graphical representation of the ''Emerald Tablet''. The emblem proliferated quickly, was frequently reproduced, and gained narrative antiquity. From Ehrd de Naxagoras in his 1733 ''Supplement to the Golden Fleece'' came an example of such a narrative. In the aforementioned discovery legend a woman named Zora finds "a precious emerald plaque" engraved with this emblem in Hermes' grave in Hebron

Hebron (; , or ; , ) is a Palestinian city in the southern West Bank, south of Jerusalem. Hebron is capital of the Hebron Governorate, the largest Governorates of Palestine, governorate in the West Bank. With a population of 201,063 in ...

Valley. The emblem thus came to be conceptualised of as part of the esoteric tradition of interpreting Egyptian hieroglyphs. It also came to serve as an example of the Renaissance-Platonic and alchemical belief that "the deepest secrets of nature could only be appropriately expressed through an obscure and veiled mode of representation”.

Nuremberg edition

The 1541

The 1541 Nuremberg

Nuremberg (, ; ; in the local East Franconian dialect: ''Nämberch'' ) is the Franconia#Towns and cities, largest city in Franconia, the List of cities in Bavaria by population, second-largest city in the States of Germany, German state of Bav ...

edition from Johannes Petreius

Johann(es) Petreius (''Hans Peterlein'', ''Petrejus'', ''Petri''; c. 1497, in Langendorf near Bad Kissingen – 18 March 1550, in Nuremberg) was a German printer in Nuremberg.

Life

He studied at the University of Basel, receiving the Master of ...

' '' Of Alchemy''—largely similar to the ''vulgate''—reads:

French sonnet translation

In the fifteenth century an anonymous French version, set in verse, appeared. A revised 1621sonnet

A sonnet is a fixed poetic form with a structure traditionally consisting of fourteen lines adhering to a set Rhyme scheme, rhyming scheme. The term derives from the Italian word ''sonetto'' (, from the Latin word ''sonus'', ). Originating in ...

version by reads:

Enlightenment

From the dawning seventeenth-centuryEnlightenment

Enlightenment or enlighten may refer to:

Age of Enlightenment

* Age of Enlightenment, period in Western intellectual history from the late 17th to late 18th century, centered in France but also encompassing (alphabetically by country or culture): ...

onward, a number of authors began to issue challenges to the attribution of the ''Emerald Tablet'' to Hermes Trismegistus. Chronologically first among them was the former alchemist Nicolas Guibert. He believed the ancients had never mentioned alchemy by name and the practice of identifying gold and silver by the names of planets was an idea first advanced by Proclus

Proclus Lycius (; 8 February 412 – 17 April 485), called Proclus the Successor (, ''Próklos ho Diádokhos''), was a Greek Neoplatonist philosopher, one of the last major classical philosophers of late antiquity. He set forth one of th ...

. He argued, therefore, that the ''Emerald Tablet'' must be inauthentic. These attacks were supported by a rising spectre of doubt surrounding all things Hermetic, following a linguistic analysis by Isaac Casaubon

Isaac Casaubon (; ; 18 February 1559 – 1 July 1614) was a classical scholar and philologist, first in France and then later in England.

His son Méric Casaubon was also a classical scholar.

Life Early life

He was born in Geneva to two F ...

, calling into question the authenticity of the Corpus Hermeticum

The is a collection of 17 Greek writings whose authorship is traditionally attributed to the legendary Hellenistic figure Hermes Trismegistus, a syncretic combination of the Greek god Hermes and the Egyptian god Thoth. The treatises were orig ...

and Hermes himself. The most prominent attack came from Athanasius Kircher

Athanasius Kircher (2 May 1602 – 27 November 1680) was a German Society of Jesus, Jesuit scholar and polymath who published around 40 major works of comparative religion, geology, and medicine. Kircher has been compared to fellow Jes ...

in his ''Egyptian Oedipus''. Kircher rejected the ''Emerald Tablet''’s attribution to Hermes Trismegistus, as it did not support his interpretation of hieroglyphs; he argued that the Tablet’s “barbaric” Latin betrayed a much later, post‐classical origin. Additionally, he pointed out that no ancient Greek philosophers ever mention it—a silence he took as evidence of forgery. Further, he associated it with a group of alchemists he considered delusional and rejected the story of its discovery in Hermes’ tomb as a pure figment of their imagination. He applied critical arguments he otherwise rejected—for example when defending the legitimacy of the Corpus Hermeticum—when the text in question conflicted with his aims. Kircher’s critique was forceful enough to draw out a response from the Danish alchemist Ole Borch

Ole Borch (7 April 1626 – 13 October 1690) (latinized to ''Olaus Borrichius'' or ''Olaus Borrichus'') was a Danish scientist, physician, grammarian, and poet. He was royal physician to both Kings Frederick III of Denmark and Christian V of D ...

in his 1668 ''On the Origin and Progress of Chemistry.'' In which Borch sought to distinguish genuinely ancient Hermetic writings from later forgeries and to re‐value the ''Emerald Tablet'' as truly Egyptian in origin. Amid this climate of inquiry and doubt a 1684 tractate by deployed linguistic analysis—incorporating Hebrew—to assert that Hermes Trismegistus was not the Egyptian Thoth

Thoth (from , borrowed from , , the reflex of " eis like the ibis") is an ancient Egyptian deity. In art, he was often depicted as a man with the head of an African sacred ibis, ibis or a baboon, animals sacred to him. His feminine count ...

but the Phoenician Taaut—whom Tacitus identifies as Tuisto

According to Tacitus's ''Germania'' (AD 98), Tuisto (or Tuisco) is the legendary divine ancestor of the Germanic peoples. The figure remains the subject of some scholarly discussion, largely focused upon etymological connections and comparisons ...

, the legendary divine progenitor of the Germanic peoples. The debate continued and both Borch’s and Kriegsmann’s treatises were reprinted (alongside many others) in Jean-Jacques Manget's '' Curious Chemical Library''.

The ''Emerald Tablet'' was still translated and commented upon by Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton () was an English polymath active as a mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, theologian, and author. Newton was a key figure in the Scientific Revolution and the Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment that followed ...

, who rendered the recondite as "perfection". But the result of this age of upheaval and inquiry was the gradual decline of alchemy during the eighteenth century. The hardest blow to alchemy's legitimacy was the advent of modern chemistry and the work of Lavoisier

Antoine-Laurent de Lavoisier ( ; ; 26 August 17438 May 1794),

CNRS (

CNRS (

science

Science is a systematic discipline that builds and organises knowledge in the form of testable hypotheses and predictions about the universe. Modern science is typically divided into twoor threemajor branches: the natural sciences, which stu ...

fundamentally conflicted with the practical and theoretical traditions of alchemy. It left no room for alchemists within the new definition of the scientist, leading to a sharp decline in alchemical works after the 1780s.

Modernity and present

Esotericism and academia

The ''Emerald Tablet'' continued to interest esotericists—and beginning in the 1850s and lasting up to the 1920s the newly emerging occultist current. In France the first occultist,Éliphas Lévi

Éliphas Lévi Zahed, born Alphonse Louis Constant (8 February 1810 – 31 May 1875), was a French esotericist, poet, and writer. Initially pursuing an ecclesiastical career in the Catholic Church, he abandoned the priesthood in his mid-twenti ...

, considered it the most important magical text. Additionally, figures like Stanislas de Guaïta and Papus spent little time engaging with the broader Hermetic tradition but focused much of their efforts onto exegesis of the ''Tablet''. In Italy Giuliano Kremmerz

Giuliano M. Kremmerz (1861–1930), born Ciro Formisano, was an Italian alchemist working within the tradition of Hermeticism.

In 1896, Kremmerz founded the Confraternita Terapeutica e Magica di Myriam (Therapeutic and Magic Brotherhood of Myria ...

authored a long commentary on it. English scholars such as John Chambers initiated the academic study of the Hermetica. However, the most influential figure in this endeavor was George R.S. Mead. He began his examinations in the ''Theosophical Society

The Theosophical Society is the organizational body of Theosophy, an esoteric new religious movement. It was founded in New York City, U.S.A. in 1875. Among its founders were Helena Blavatsky, a Russian mystic and the principal thinker of the ...

'', but broke with it in 1879. From thereon he developed a scholarly objectivity when engaging with the material while not concealing his personal occultist beliefs.

The co-founder of the Theosophical Society, Helena Blavatsky

Helena Petrovna Blavatsky (; – 8 May 1891), often known as Madame Blavatsky, was a Russian-born Mysticism, mystic and writer who emigrated to the United States where she co-founded the Theosophical Society in 1875. She gained an internat ...

produced exegetical interpretations of the ''Tablet''. She also popularized a paraphrase of the second verse of the ''vulgate'': "as above, so below

"As above, so below" is a popular modern paraphrase of the second verse of the ''Emerald Tablet,'' a short Hermetica, Hermetic text which first appeared in an Arabic source from the late eighth or early ninth century. The paraphrase is based on ...

". This use—along with that in the ''Kybalion''—propelled it to become an oft-cited motto. Later in the twentieth century, it would rise to particular prominence in New Age

New Age is a range of Spirituality, spiritual or Religion, religious practices and beliefs that rapidly grew in Western world, Western society during the early 1970s. Its highly eclecticism, eclectic and unsystematic structure makes a precise d ...

circles. This led to its adoption as a title for various works of art.

A figure also influenced by Blavatsky was the Dutch founder of the '' Lectorium Rosicrucianum'', Jan van Rijckenborgh. He used the Tablet to derive the crux of his own worldview and ascribed much antiquity to it. The world's most extensive collection of Hermetica is found in the ''Bibliotheca Philosophica Hermetica

Bibliotheca Philosophica Hermetica (BPH) or The Ritman Library is a Dutch library founded by Joost Ritman located in the Huis met de Hoofden (House with the Heads) at Keizersgracht 123, in the center of Amsterdam. The Bibliotheca Philosophica He ...

'', which was founded by a memer of the ''Lectorium'', Joost Ritman. Perennialist

The perennial philosophy (), also referred to as perennialism and perennial wisdom, is a school of thought in philosophy and spirituality that posits that the recurrence of common themes across world religions illuminates universal truths about ...

s as a whole have kept their distance from Hermeticism and its receptions in Western esotericism

Western esotericism, also known as the Western mystery tradition, is a wide range of loosely related ideas and movements that developed within Western society. These ideas and currents are united since they are largely distinct both from orthod ...

more generally. However, one of the best-known modern commentaries on the ''Tablet'' was produced by the traditionalist, Titus Burckhardt

Titus Burckhardt (; ; 24 October 1908 – 15 January 1984) was a Swiss writer and a leading member of the Perennialist or Traditionalist School. He was the author of numerous works on metaphysics, cosmology, anthropology, esoterism, alchemy, Su ...

.

A prominent academic reception of the ''Tablet'' occurred in Carl Jung

Carl Gustav Jung ( ; ; 26 July 1875 – 6 June 1961) was a Swiss psychiatrist, psychotherapist, and psychologist who founded the school of analytical psychology. A prolific author of Carl Jung publications, over 20 books, illustrator, and corr ...

's psychology of alchemy. He saw it as the paramount text of alchemy. Jung had read and was familiar with the Arabic text of the '' Book of the Secret of Creation'' and the debates surrounding the text's age and original language. He focused his textual analysis mainly, however, on the Latin ''vulgate'' text. The ''Tablet''’s alchemical operations—most notably the “operation of the sun”—became, for Jung, powerful metaphors: the sun’s “art” of creating gold is none other than consciousness splitting from a “primeval” archetypal

The concept of an archetype ( ) appears in areas relating to behavior, History of psychology#Emergence of German experimental psychology, historical psychology, philosophy and literary analysis.

An archetype can be any of the following:

# a stat ...

source, working through the “prima materia” of the psyche, and reuniting to generate a transformed, individuated self

In philosophy, the self is an individual's own being, knowledge, and values, and the relationship between these attributes.

The first-person perspective distinguishes selfhood from personal identity. Whereas "identity" is (literally) same ...

.

Arts and popular culture

At the beginning of the twentieth century, alchemy fascinated thesurrealist

Surrealism is an art movement, art and cultural movement that developed in Europe in the aftermath of World War I in which artists aimed to allow the unconscious mind to express itself, often resulting in the depiction of illogical or dreamlike s ...

André Breton

André Robert Breton (; ; 19 February 1896 – 28 September 1966) was a French writer and poet, the co-founder, leader, and principal theorist of surrealism. His writings include the first ''Surrealist Manifesto'' (''Manifeste du surréalisme'') ...

. He saw in Hermetic practice a model for “transubstantiating the world” and resisting the modern reign of ''miserablism''. In the 1924 Surrealist Manifesto

The Surrealist Manifesto refers to several publications by Yvan Goll and André Breton, leaders of rival Surrealism, surrealist groups. Goll and Breton both published manifestos in October 1924 titled ''Manifeste du surréalisme''. Breton wrote ...

he said: "Heraclitus

Heraclitus (; ; ) was an Ancient Greece, ancient Greek Pre-Socratic philosophy, pre-Socratic philosopher from the city of Ephesus, which was then part of the Achaemenid Empire, Persian Empire. He exerts a wide influence on Western philosophy, ...

is surrealist in dialectic. Lully

Jean-Baptiste Lully ( – 22 March 1687) was a French composer, dancer and instrumentalist of Italian birth, who is considered a master of the French Baroque music style. Best known for his operas, he spent most of his life working in the court o ...

is surrealist in definition. Flamel is surrealist in the night of gold." He believed the aim of surrealism should be to ascertain the point within the mind where life and death, real and imaginary, past and future etc no longer seem contradictory. This approach could be seen as merely Hegelian

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (27 August 1770 – 14 November 1831) was a 19th-century German idealist. His influence extends across a wide range of topics from metaphysical issues in epistemology and ontology, to political philosophy and the ...

, but Breton's circle was steeped in living Hermeticism: the Surrealists devoured Fulcanelli

Fulcanelli (fl. 1920s) was the name used by a French alchemist and esoteric writer, whose identity is still debated. The name Fulcanelli seems to be a play on words: Vulcan, the ancient Roman god of fire, plus El, a Canaanite name for God and so ...

, tried to enlist Eugène Canseliet and René Guénon for '' La Révolution surréaliste'', and flocked to Maria de Naglowska's occult soirées in early‑1930s Paris. Additionally, Hegel's philosophy itself was influenced by esoteric thinkers, like Jakob Böhme

Jakob Böhme (; ; 24 April 1575 – 17 November 1624) was a German philosopher, Christian mysticism, Christian mystic, and Lutheran Protestant Theology, theologian. He was considered an original thinker by many of his contemporaries within the L ...

and Emanual Swedenborg—a fact Breton was acutely aware of. In the introduction of a 1942 essay, Breton overturned the ''Emerald Tablet''’s dictum “as above, so below

"As above, so below" is a popular modern paraphrase of the second verse of the ''Emerald Tablet,'' a short Hermetica, Hermetic text which first appeared in an Arabic source from the late eighth or early ninth century. The paraphrase is based on ...

” by invoking the image of a soaring bird and a lift descending into a mine-shaft clashing. The metaphor led up to his new commandment: “Never believe in the interior of a cave

Caves or caverns are natural voids under the Earth's Planetary surface, surface. Caves often form by the weathering of rock and often extend deep underground. Exogene caves are smaller openings that extend a relatively short distance undergrou ...

, always in the surface of an egg”. Breton thereby employed alchemy to collapse depth and surface. He used it as a means to bind dichotomous forces into a seamless whole. He saw Max Ernst

Max Ernst (; 2 April 1891 – 1 April 1976) was a German-born painter, sculptor, printmaker, graphic artist, and poet. A prolific artist, Ernst was a primary pioneer of the Dada movement and surrealism in Europe. He had no formal artistic trai ...

, who claimed to have been born from an egg, as that very “alchemical egg”—his birth myth and his art as having fused celestial and chthonic forces into that single whole.

Jorge Ben

Jorge Duílio Lima Menezes (born March 22, 1939) is a Brazilian popular musician, performing under the stage name Jorge Ben Jor since the 1980s, though commonly known by his former stage name Jorge Ben (). Performing in a samba style that also ...

released the studio album '' A Tábua de Esmeralda'' ("The Emerald Tablet") in 1974. In it, he explored the theme of alchemy through tracks like “Os Alquimistas estão chegando Os Alquimistas,” “Errare Humanum Est,” and “Hermes Trismegisto e Sua Celeste Tábua de Esmeralda,” using reiterated modal phrases that evoked a liturgical resonance. The album exemplified Ben’s distinctive fusion of samba

Samba () is a broad term for many of the rhythms that compose the better known Brazilian music genres that originated in the Afro-Brazilians, Afro Brazilian communities of Bahia in the late 19th century and early 20th century, It is a name or ...

with elements of jazz

Jazz is a music genre that originated in the African-American communities of New Orleans, Louisiana, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Its roots are in blues, ragtime, European harmony, African rhythmic rituals, spirituals, h ...

and rock

Rock most often refers to:

* Rock (geology), a naturally occurring solid aggregate of minerals or mineraloids

* Rock music, a genre of popular music

Rock or Rocks may also refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* Rock, Caerphilly, a location in Wale ...

, shaped by his percussive, self-taught guitar technique and supported by musicians from across the spectrum of Música popular brasileira

(, ''Brazilian Popular Music'') or MPB is a trend in post-bossa nova urban popular music in Brazil that revisits typical Brazilian styles such as samba, samba-canção and Baião (music), baião and other Brazilian regional music, combining them ...

. Some Música popular brasileira-traditionalists saw this as a concession to the US garage rock-inspired style known as Jovem Guarda

Jovem GuardaJovem Guarda translates literally as "young guard". It could be interpreted as "vanguard". was primarily a Brazilian musical television show first aired by Rede Record in 1965, although the term soon expanded to designate the entir ...

.

Manfred Kelkel

Manfred Kelkel (15 January 1929 – 18 April 1999) was a 20th-century French musicologist and composer of contemporary music. A pupil of Darius Milhaud at the Conservatoire de Paris, he got interested in the music of Russian composer Alexander Scri ...

composed ''Tabula Smaragdina'' (Op. 24) between 1975 and 1977. Conceived as a ''ballet

Ballet () is a type of performance dance that originated during the Italian Renaissance in the fifteenth century and later developed into a concert dance form in France and Russia. It has since become a widespread and highly technical form of ...

hermétique'', the work aimed to unite his passions for esotericism, alchemy, and music. Kelkel sought to render sound and thought visible through graphic mandalas

A mandala (, ) is a geometric configuration of symbols. In various spiritual traditions, mandalas may be employed for focusing attention of practitioners and adepts, as a spiritual guidance tool, for establishing a sacred space and as an aid ...

, which mapped zodiac signs

In Western astrology, astrological signs are the twelve 30-degree sectors that make up Earth's 360-degree orbit around the Sun. The signs enumerate from the first day of spring, known as the First Point of Aries, which is the vernal equinox. T ...

, planets, and the four elements

The classical elements typically refer to earth, water, air, fire, and (later) aether which were proposed to explain the nature and complexity of all matter in terms of simpler substances. Ancient cultures in Greece, Angola, Tibet, India, a ...

onto instruments, scales, and rhythms. During performance, twelve symbolic images were projected alongside a simplified conventional score—transforming each page of the work into both stage scenery and musical instructions. To structure the piece, Kelkel drew on sources such as Chinese trigrams, fractal geometry

In mathematics, a fractal is a geometric shape containing detailed structure at arbitrarily small scales, usually having a fractal dimension strictly exceeding the topological dimension. Many fractals appear similar at various scales, as ...

, medieval magic squares

In mathematics, especially historical and recreational mathematics, a square array of numbers, usually positive integers, is called a magic square if the sums of the numbers in each row, each column, and both main diagonals are the same. The " ...

, and the harmony of the spheres. He created twelve successive movements, each named after a phase in the alchemical process—such as ''Nuptiae chymicae'' and ''Coagulatio''—and each possessing its own emblem and formal rules. The result was a codified "metamusic", designed to awaken hidden cosmic and psychological resonances through structured, alchemical transformations..

In the 2010s German time travel

Time travel is the hypothetical activity of traveling into the past or future. Time travel is a concept in philosophy and fiction, particularly science fiction. In fiction, time travel is typically achieved through the use of a device known a ...

television series ''Dark

Darkness is the condition resulting from a lack of illumination, or an absence of visible light.

Human vision is unable to distinguish colors in conditions of very low luminance because the hue-sensitive photoreceptor cells on the retina are ...

'', the mysterious priest Noah has a large image of a graphic depiction of an emerald tablet, featuring the text of the ''Emerald Tablet'', tattooed on his back. The image, which stems from Heinrich Khunrath's ''Amphitheatre of Eternal Wisdom'' (1609), also appears on a metal door in the caves that are central to the plot. Several characters are shown looking at copies of the text. A verse from the 1541 Nuremberg version plays a prominent thematic role in the series and is the title of the sixth episode of the first season..

Notes

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* * * {{Authority control Alchemical documents Hermetica Medieval texts Arabic literature