Elizabeth I (Armada Portrait) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and

Elizabeth was born at Greenwich Palace on 7 September 1533 and was named after her grandmothers, Elizabeth of York and Lady Elizabeth Howard. She was the second child of

Elizabeth was born at Greenwich Palace on 7 September 1533 and was named after her grandmothers, Elizabeth of York and Lady Elizabeth Howard. She was the second child of

Henry VIII died in 1547 and Elizabeth's half-brother, Edward VI, became king at the age of nine. Catherine Parr, Henry's widow, soon married Thomas Seymour, Baron Seymour of Sudeley, Edward VI's uncle and the brother of Lord Protector Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset. The couple took Elizabeth into their household at Chelsea. There Elizabeth experienced an emotional crisis that some historians believe affected her for the rest of her life. Thomas Seymour engaged in romps and horseplay with the 14-year-old Elizabeth, including entering her bedroom in his nightgown, tickling her, and slapping her on the buttocks. Elizabeth rose early and surrounded herself with maids to avoid his unwelcome morning visits. Parr, rather than confront her husband over his inappropriate activities, joined in. Twice she accompanied him in tickling Elizabeth, and once held her while he cut her black gown "into a thousand pieces". However, after Parr discovered the pair in an embrace, she ended this state of affairs. In May 1548, Elizabeth was sent away.

Thomas Seymour nevertheless continued scheming to control the royal family and tried to have himself appointed the governor of the King's person. When Parr died after childbirth on 5 September 1548, he renewed his attentions towards Elizabeth, intent on marrying her. Her governess Kat Ashley, who was fond of Seymour, sought to convince Elizabeth to take him as her husband. She tried to convince Elizabeth to write to Seymour and "comfort him in his sorrow", but Elizabeth claimed that Thomas was not so saddened by her stepmother's death as to need comfort.

In January 1549, Seymour was arrested and imprisoned in the Tower on suspicion of conspiring to depose his brother Somerset as Protector, marry Lady Jane Grey to King Edward VI, and take Elizabeth as his own wife. Elizabeth, living at Hatfield House, would admit nothing. Her stubbornness exasperated her interrogator, Robert Tyrwhitt, who reported, "I do see it in her face that she is guilty". Seymour was beheaded on 20 March 1549.

Henry VIII died in 1547 and Elizabeth's half-brother, Edward VI, became king at the age of nine. Catherine Parr, Henry's widow, soon married Thomas Seymour, Baron Seymour of Sudeley, Edward VI's uncle and the brother of Lord Protector Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset. The couple took Elizabeth into their household at Chelsea. There Elizabeth experienced an emotional crisis that some historians believe affected her for the rest of her life. Thomas Seymour engaged in romps and horseplay with the 14-year-old Elizabeth, including entering her bedroom in his nightgown, tickling her, and slapping her on the buttocks. Elizabeth rose early and surrounded herself with maids to avoid his unwelcome morning visits. Parr, rather than confront her husband over his inappropriate activities, joined in. Twice she accompanied him in tickling Elizabeth, and once held her while he cut her black gown "into a thousand pieces". However, after Parr discovered the pair in an embrace, she ended this state of affairs. In May 1548, Elizabeth was sent away.

Thomas Seymour nevertheless continued scheming to control the royal family and tried to have himself appointed the governor of the King's person. When Parr died after childbirth on 5 September 1548, he renewed his attentions towards Elizabeth, intent on marrying her. Her governess Kat Ashley, who was fond of Seymour, sought to convince Elizabeth to take him as her husband. She tried to convince Elizabeth to write to Seymour and "comfort him in his sorrow", but Elizabeth claimed that Thomas was not so saddened by her stepmother's death as to need comfort.

In January 1549, Seymour was arrested and imprisoned in the Tower on suspicion of conspiring to depose his brother Somerset as Protector, marry Lady Jane Grey to King Edward VI, and take Elizabeth as his own wife. Elizabeth, living at Hatfield House, would admit nothing. Her stubbornness exasperated her interrogator, Robert Tyrwhitt, who reported, "I do see it in her face that she is guilty". Seymour was beheaded on 20 March 1549.

Elizabeth became queen at the age of 25, and declared her intentions to her council and other peers who had come to Hatfield to swear allegiance. The speech contains the first record of her adoption of the medieval political theology of the sovereign's "two bodies": the body natural and the body politic:

As her triumphal progress wound through the city on the eve of the coronation ceremony, she was welcomed wholeheartedly by the citizens and greeted by orations and pageants, most with a strong Protestant flavour. Elizabeth's open and gracious responses endeared her to the spectators, who were "wonderfully ravished". The following day, 15 January 1559, a date chosen by her astrologer John Dee, Elizabeth was crowned and anointed by Owen Oglethorpe, the Catholic bishop of Carlisle, in Westminster Abbey. She was then presented for the people's acceptance, amidst a deafening noise of organs, fifes, trumpets, drums, and bells. Although Elizabeth was welcomed as queen in England, the country was still in a state of anxiety over the perceived Catholic threat at home and overseas, as well as the choice of whom she would marry.

Elizabeth became queen at the age of 25, and declared her intentions to her council and other peers who had come to Hatfield to swear allegiance. The speech contains the first record of her adoption of the medieval political theology of the sovereign's "two bodies": the body natural and the body politic:

As her triumphal progress wound through the city on the eve of the coronation ceremony, she was welcomed wholeheartedly by the citizens and greeted by orations and pageants, most with a strong Protestant flavour. Elizabeth's open and gracious responses endeared her to the spectators, who were "wonderfully ravished". The following day, 15 January 1559, a date chosen by her astrologer John Dee, Elizabeth was crowned and anointed by Owen Oglethorpe, the Catholic bishop of Carlisle, in Westminster Abbey. She was then presented for the people's acceptance, amidst a deafening noise of organs, fifes, trumpets, drums, and bells. Although Elizabeth was welcomed as queen in England, the country was still in a state of anxiety over the perceived Catholic threat at home and overseas, as well as the choice of whom she would marry.

In the spring of 1559, it became evident that Elizabeth was in love with her childhood friend Robert Dudley. It was said that his wife Amy was suffering from a "malady in one of her breasts" and that the Queen would like to marry Robert if his wife should die. By the autumn of 1559, several foreign suitors were vying for Elizabeth's hand; their impatient envoys engaged in ever more scandalous talk and reported that a marriage with her favourite was not welcome in England: "There is not a man who does not cry out on him and her with indignation ... she will marry none but the favoured Robert." Amy Dudley died in September 1560, from a fall from a flight of stairs and, despite the coroner's inquest finding of accident, many people suspected her husband of having arranged her death so that he could marry the Queen. Elizabeth seriously considered marrying Dudley for some time. However, William Cecil, Nicholas Throckmorton, and some conservative peers made their disapproval unmistakably clear. There were even rumours that the nobility would rise if the marriage took place.

Among other marriage candidates being considered for the queen, Robert Dudley continued to be regarded as a possible candidate for nearly another decade. Elizabeth was extremely jealous of his affections, even when she no longer meant to marry him herself. She raised Dudley to the peerage as

In the spring of 1559, it became evident that Elizabeth was in love with her childhood friend Robert Dudley. It was said that his wife Amy was suffering from a "malady in one of her breasts" and that the Queen would like to marry Robert if his wife should die. By the autumn of 1559, several foreign suitors were vying for Elizabeth's hand; their impatient envoys engaged in ever more scandalous talk and reported that a marriage with her favourite was not welcome in England: "There is not a man who does not cry out on him and her with indignation ... she will marry none but the favoured Robert." Amy Dudley died in September 1560, from a fall from a flight of stairs and, despite the coroner's inquest finding of accident, many people suspected her husband of having arranged her death so that he could marry the Queen. Elizabeth seriously considered marrying Dudley for some time. However, William Cecil, Nicholas Throckmorton, and some conservative peers made their disapproval unmistakably clear. There were even rumours that the nobility would rise if the marriage took place.

Among other marriage candidates being considered for the queen, Robert Dudley continued to be regarded as a possible candidate for nearly another decade. Elizabeth was extremely jealous of his affections, even when she no longer meant to marry him herself. She raised Dudley to the peerage as

This claim of virginity was not universally accepted. Catholics accused Elizabeth of engaging in "filthy lust" that symbolically defiled the nation along with her body. Henry IV of France said that one of the great questions of Europe was "whether Queen Elizabeth was a maid or no".

A central issue, when it comes to the question of Elizabeth's virginity, was whether the Queen ever consummated her love affair with Robert Dudley. In 1559, she had Dudley's bedchambers moved next to her own apartments. In 1561, she was mysteriously bedridden with an illness that caused her body to swell.

In 1587, a young man calling himself Arthur Dudley was arrested on the coast of Spain under suspicion of being a spy. The man claimed to be the illegitimate son of Elizabeth and Robert Dudley, with his age being consistent with birth during the 1561 illness. He was taken to

This claim of virginity was not universally accepted. Catholics accused Elizabeth of engaging in "filthy lust" that symbolically defiled the nation along with her body. Henry IV of France said that one of the great questions of Europe was "whether Queen Elizabeth was a maid or no".

A central issue, when it comes to the question of Elizabeth's virginity, was whether the Queen ever consummated her love affair with Robert Dudley. In 1559, she had Dudley's bedchambers moved next to her own apartments. In 1561, she was mysteriously bedridden with an illness that caused her body to swell.

In 1587, a young man calling himself Arthur Dudley was arrested on the coast of Spain under suspicion of being a spy. The man claimed to be the illegitimate son of Elizabeth and Robert Dudley, with his age being consistent with birth during the 1561 illness. He was taken to

Mary was soon the focus for rebellion. In 1569 there was a major Catholic rising in the North; the goal was to free Mary, marry her to Thomas Howard, Duke of Norfolk, and put her on the English throne. After the rebels' defeat, over 750 of them were executed on Elizabeth's orders. In the belief that the revolt had been successful, Pope Pius V issued a bull in 1570, titled '' Regnans in Excelsis'', which declared "Elizabeth, the pretended Queen of England and the servant of crime" to be excommunicated and a heretic, releasing all her subjects from any allegiance to her. Catholics who obeyed her orders were threatened with

Mary was soon the focus for rebellion. In 1569 there was a major Catholic rising in the North; the goal was to free Mary, marry her to Thomas Howard, Duke of Norfolk, and put her on the English throne. After the rebels' defeat, over 750 of them were executed on Elizabeth's orders. In the belief that the revolt had been successful, Pope Pius V issued a bull in 1570, titled '' Regnans in Excelsis'', which declared "Elizabeth, the pretended Queen of England and the servant of crime" to be excommunicated and a heretic, releasing all her subjects from any allegiance to her. Catholics who obeyed her orders were threatened with

When the Protestant Henry IV inherited the French throne in 1589, Elizabeth sent him military support. It was her first venture into France since the retreat from Le Havre in 1563. Henry's succession was strongly contested by the Catholic League and by Philip II, and Elizabeth feared a Spanish takeover of the channel ports.

The subsequent early English campaigns in France, however, were disorganised and ineffective. Peregrine Bertie, largely ignoring Elizabeth's orders, roamed northern France to little effect, with an army of 4,000 men. He withdrew in disarray in December 1590 following the failure of the Siege of Paris. The following year, John Norreys, led 3,000 men to campaign in Brittany, which despite victory at Quenelec in June ended inconclusively.

In July, Elizabeth sent out another force under Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex, to help Henry IV in besieging Rouen which Norreys joined. Essex however accomplished nothing and returned home in January 1592, and Henry abandoned the siege in April. As usual, Elizabeth lacked control over her commanders once they were abroad. "Where he is, or what he doth, or what he is to do," she wrote of Essex, "we are ignorant". Norreys left for London to plead in person for more support. Elizabeth dithered, and in Norreys' absence in May 1592, a Catholic League and Spanish army almost destroyed the remains of his army at Craon, north-west France. As for all such expeditions, Elizabeth was unwilling to invest in the supplies and reinforcements requested by the commanders.

In March 1593, Henry converted to Catholicism in Paris to secure his hold on the French crown. Elizabeth was distraught and shocked at this move, and she resented any further attempts by Henry to win her over and ordered all of her forces home. Despite this, the Catholic leaguers did not trust Henry and still opposed him - their Spanish allies meanwhile continued to campaign in Brittany and advanced on the major port of Brest. King Philip of Spain was intent on establishing advanced bases in western France from which his rebuilt navy could constantly threaten England. Norreys wrote to Elizabeth warning her about this threat - and after some hesitation saw the danger and so sent another force in 1594. Norreys with 4,000 men worked with his French counterpart Jean VI d'Aumont. This time success was achieved; after taking a number of towns, they laid siege to an encroaching Spanish fort near Brest which was overrun and destroyed. This was a decisive victory ending the threat, and not long after the Catholic league collapsed. Elizabeth hailed Norreys a hero, but then ordered him back to England along with his troops.

In 1595 Henry declared war on Spain and wanted England to form an alliance with France. Elizabeth however was not interested, owing to her mistrust of Henry and the fear that France was becoming more dominant. The Spanish however captured Calais in 1596, and with Spain now in sight of England once more, Elizabeth relented – the triple alliance was formed along with the Dutch Republic. Elizabeth however still hesitated, attempting to barter for either Boulogne or an indemnity in money, the latter of which was agreed. When Spanish forces seized

When the Protestant Henry IV inherited the French throne in 1589, Elizabeth sent him military support. It was her first venture into France since the retreat from Le Havre in 1563. Henry's succession was strongly contested by the Catholic League and by Philip II, and Elizabeth feared a Spanish takeover of the channel ports.

The subsequent early English campaigns in France, however, were disorganised and ineffective. Peregrine Bertie, largely ignoring Elizabeth's orders, roamed northern France to little effect, with an army of 4,000 men. He withdrew in disarray in December 1590 following the failure of the Siege of Paris. The following year, John Norreys, led 3,000 men to campaign in Brittany, which despite victory at Quenelec in June ended inconclusively.

In July, Elizabeth sent out another force under Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex, to help Henry IV in besieging Rouen which Norreys joined. Essex however accomplished nothing and returned home in January 1592, and Henry abandoned the siege in April. As usual, Elizabeth lacked control over her commanders once they were abroad. "Where he is, or what he doth, or what he is to do," she wrote of Essex, "we are ignorant". Norreys left for London to plead in person for more support. Elizabeth dithered, and in Norreys' absence in May 1592, a Catholic League and Spanish army almost destroyed the remains of his army at Craon, north-west France. As for all such expeditions, Elizabeth was unwilling to invest in the supplies and reinforcements requested by the commanders.

In March 1593, Henry converted to Catholicism in Paris to secure his hold on the French crown. Elizabeth was distraught and shocked at this move, and she resented any further attempts by Henry to win her over and ordered all of her forces home. Despite this, the Catholic leaguers did not trust Henry and still opposed him - their Spanish allies meanwhile continued to campaign in Brittany and advanced on the major port of Brest. King Philip of Spain was intent on establishing advanced bases in western France from which his rebuilt navy could constantly threaten England. Norreys wrote to Elizabeth warning her about this threat - and after some hesitation saw the danger and so sent another force in 1594. Norreys with 4,000 men worked with his French counterpart Jean VI d'Aumont. This time success was achieved; after taking a number of towns, they laid siege to an encroaching Spanish fort near Brest which was overrun and destroyed. This was a decisive victory ending the threat, and not long after the Catholic league collapsed. Elizabeth hailed Norreys a hero, but then ordered him back to England along with his troops.

In 1595 Henry declared war on Spain and wanted England to form an alliance with France. Elizabeth however was not interested, owing to her mistrust of Henry and the fear that France was becoming more dominant. The Spanish however captured Calais in 1596, and with Spain now in sight of England once more, Elizabeth relented – the triple alliance was formed along with the Dutch Republic. Elizabeth however still hesitated, attempting to barter for either Boulogne or an indemnity in money, the latter of which was agreed. When Spanish forces seized

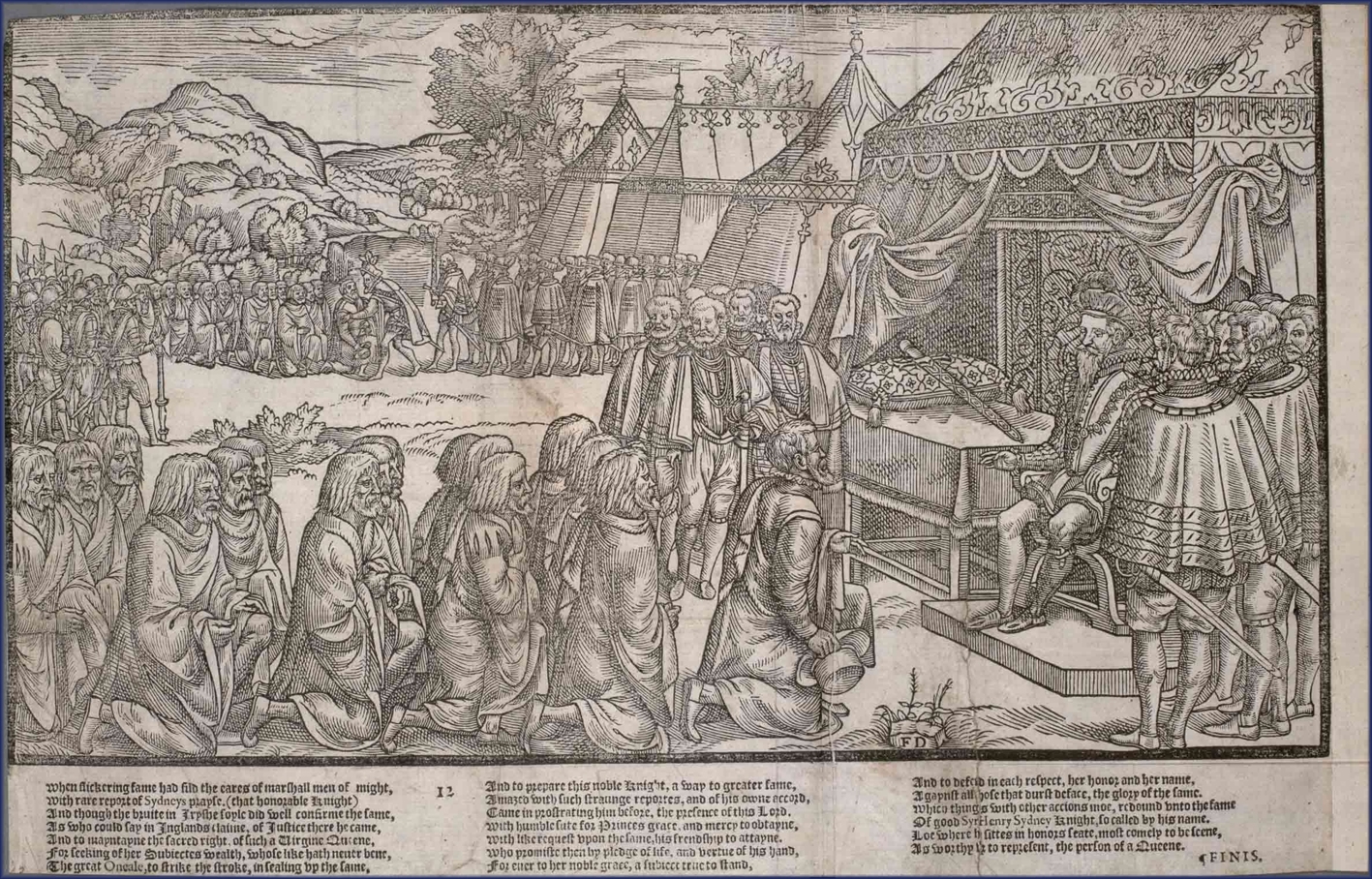

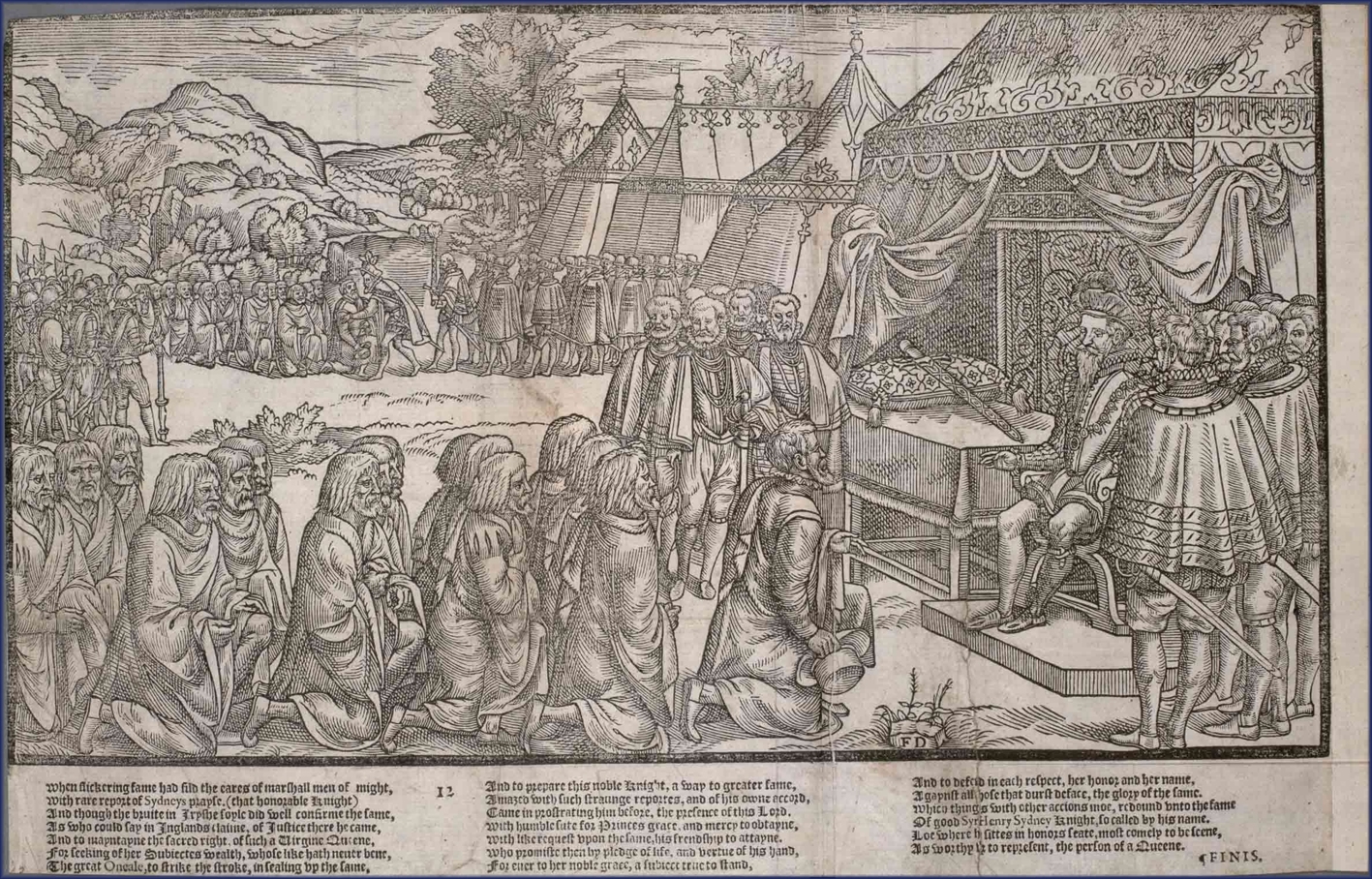

Although Ireland was one of her two kingdoms, Elizabeth faced a hostile, and in places virtually autonomous, Irish population that adhered to Catholicism and was willing to defy her authority and plot with her enemies. Her policy there was to grant land to her courtiers and prevent the rebels from giving Spain a base from which to attack England. In the course of a series of uprisings, Crown forces pursued scorched-earth tactics, burning the land and slaughtering man, woman and child. During a revolt in Munster led by Gerald FitzGerald, Earl of Desmond, in 1582, an estimated 30,000 Irish people starved to death. The poet and colonist

Although Ireland was one of her two kingdoms, Elizabeth faced a hostile, and in places virtually autonomous, Irish population that adhered to Catholicism and was willing to defy her authority and plot with her enemies. Her policy there was to grant land to her courtiers and prevent the rebels from giving Spain a base from which to attack England. In the course of a series of uprisings, Crown forces pursued scorched-earth tactics, burning the land and slaughtering man, woman and child. During a revolt in Munster led by Gerald FitzGerald, Earl of Desmond, in 1582, an estimated 30,000 Irish people starved to death. The poet and colonist

Trade and diplomatic relations developed between England and the Barbary states during the rule of Elizabeth. England established a trading relationship with

Trade and diplomatic relations developed between England and the Barbary states during the rule of Elizabeth. England established a trading relationship with

Tate.org.uk

Elizabeth "agreed to sell munitions supplies to Morocco, and she and Mulai Ahmad al-Mansur talked on and off about mounting a joint operation against the Spanish". Discussions, however, remained inconclusive, and both rulers died within two years of the embassy. Diplomatic relations were also established with the

One of the causes for this "second reign" of Elizabeth, as it is sometimes called, was the changed character of Elizabeth's governing body, the privy council in the 1590s. A new generation was in power. With the exception of William Cecil, Baron Burghley, the most important politicians had died around 1590: the Earl of Leicester in 1588; Francis Walsingham in 1590; and Christopher Hatton in 1591. Factional strife in the government, which had not existed in a noteworthy form before the 1590s, now became its hallmark. A bitter rivalry arose between Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex, and Robert Cecil, son of Lord Burghley, with both being supported by their respective adherents. The struggle for the most powerful positions in the state marred the kingdom's politics. The Queen's personal authority was lessening, as is shown in the 1594 affair of Dr. Roderigo Lopes, her trusted physician. When he was wrongly accused by the Earl of Essex of treason out of personal pique, she could not prevent the doctor's execution, although she had been angry about his arrest and seems not to have believed in his guilt.

During the last years of her reign, Elizabeth came to rely on the granting of monopolies as a cost-free system of patronage, rather than asking Parliament for more subsidies in a time of war. The practice soon led to price-fixing, the enrichment of courtiers at the public's expense, and widespread resentment. This culminated in agitation in the House of Commons during the parliament of 1601. In her " Golden Speech" of 30 November 1601 at Whitehall Palace to a deputation of 140 members, Elizabeth professed ignorance of the abuses, and won the members over with promises and her usual appeal to the emotions:

This same period of economic and political uncertainty, however, produced an unsurpassed literary flowering in England. The first signs of a new literary movement had appeared at the end of the second decade of Elizabeth's reign, with John Lyly's ''Euphues'' and

One of the causes for this "second reign" of Elizabeth, as it is sometimes called, was the changed character of Elizabeth's governing body, the privy council in the 1590s. A new generation was in power. With the exception of William Cecil, Baron Burghley, the most important politicians had died around 1590: the Earl of Leicester in 1588; Francis Walsingham in 1590; and Christopher Hatton in 1591. Factional strife in the government, which had not existed in a noteworthy form before the 1590s, now became its hallmark. A bitter rivalry arose between Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex, and Robert Cecil, son of Lord Burghley, with both being supported by their respective adherents. The struggle for the most powerful positions in the state marred the kingdom's politics. The Queen's personal authority was lessening, as is shown in the 1594 affair of Dr. Roderigo Lopes, her trusted physician. When he was wrongly accused by the Earl of Essex of treason out of personal pique, she could not prevent the doctor's execution, although she had been angry about his arrest and seems not to have believed in his guilt.

During the last years of her reign, Elizabeth came to rely on the granting of monopolies as a cost-free system of patronage, rather than asking Parliament for more subsidies in a time of war. The practice soon led to price-fixing, the enrichment of courtiers at the public's expense, and widespread resentment. This culminated in agitation in the House of Commons during the parliament of 1601. In her " Golden Speech" of 30 November 1601 at Whitehall Palace to a deputation of 140 members, Elizabeth professed ignorance of the abuses, and won the members over with promises and her usual appeal to the emotions:

This same period of economic and political uncertainty, however, produced an unsurpassed literary flowering in England. The first signs of a new literary movement had appeared at the end of the second decade of Elizabeth's reign, with John Lyly's ''Euphues'' and

Elizabeth's senior adviser, Lord Burghley, died on 4 August 1598. His political mantle passed to his son Robert, who soon became the leader of the government. One task he addressed was to prepare the way for a smooth succession. Since Elizabeth would never name her successor, Robert Cecil was obliged to proceed in secret. He therefore entered into a coded negotiation with James VI of Scotland, who had a strong but unrecognised claim. Cecil coached the impatient James to humour Elizabeth and "secure the heart of the highest, to whose sex and quality nothing is so improper as either needless expostulations or over much curiosity in her own actions". The advice worked. James's tone delighted Elizabeth, who responded: "So trust I that you will not doubt but that your last letters are so acceptably taken as my thanks cannot be lacking for the same, but yield them to you in grateful sort". In historian J. E. Neale's view, Elizabeth may not have declared her wishes openly to James, but she made them known with "unmistakable if veiled phrases".

Elizabeth's senior adviser, Lord Burghley, died on 4 August 1598. His political mantle passed to his son Robert, who soon became the leader of the government. One task he addressed was to prepare the way for a smooth succession. Since Elizabeth would never name her successor, Robert Cecil was obliged to proceed in secret. He therefore entered into a coded negotiation with James VI of Scotland, who had a strong but unrecognised claim. Cecil coached the impatient James to humour Elizabeth and "secure the heart of the highest, to whose sex and quality nothing is so improper as either needless expostulations or over much curiosity in her own actions". The advice worked. James's tone delighted Elizabeth, who responded: "So trust I that you will not doubt but that your last letters are so acceptably taken as my thanks cannot be lacking for the same, but yield them to you in grateful sort". In historian J. E. Neale's view, Elizabeth may not have declared her wishes openly to James, but she made them known with "unmistakable if veiled phrases".

The Queen's health remained fair until the autumn of 1602, when a series of deaths among her friends plunged her into a severe depression. In February 1603, the death of Catherine Carey, Countess of Nottingham, the niece of her cousin and close friend Lady Knollys, came as a particular blow. In March, Elizabeth fell sick and remained in a "settled and unremovable melancholy", and sat motionless on a cushion for hours on end. When Robert Cecil told her that she must go to bed, she snapped: "Must is not a word to use to princes, little man." She died on 24 March 1603 at Richmond Palace, between two and three in the morning. A few hours later, Cecil and the council set their plans in motion and proclaimed James king of England.

While it has become normative to record Elizabeth's death as occurring in 1603, following English calendar reform in the 1750s, at the time England observed New Year's Day on 25 March, commonly known as Lady Day. Thus Elizabeth died on the last day of the year 1602 in the old calendar. The modern convention is to use the old style calendar for the day and month while using the new style calendar for the year.

Elizabeth's coffin was carried downriver at night to Whitehall, on a barge lit with torches. At her funeral on 28 April, the coffin was taken to Westminster Abbey on a hearse drawn by four horses hung with black velvet. In the words of the chronicler John Stow:

Elizabeth was interred in Westminster Abbey, in a tomb shared with her half-sister, Mary I. The Latin inscription on their tomb, , translates to "Consorts in realm and tomb, here we sleep, Elizabeth and Mary, sisters, in hope of resurrection".

The Queen's health remained fair until the autumn of 1602, when a series of deaths among her friends plunged her into a severe depression. In February 1603, the death of Catherine Carey, Countess of Nottingham, the niece of her cousin and close friend Lady Knollys, came as a particular blow. In March, Elizabeth fell sick and remained in a "settled and unremovable melancholy", and sat motionless on a cushion for hours on end. When Robert Cecil told her that she must go to bed, she snapped: "Must is not a word to use to princes, little man." She died on 24 March 1603 at Richmond Palace, between two and three in the morning. A few hours later, Cecil and the council set their plans in motion and proclaimed James king of England.

While it has become normative to record Elizabeth's death as occurring in 1603, following English calendar reform in the 1750s, at the time England observed New Year's Day on 25 March, commonly known as Lady Day. Thus Elizabeth died on the last day of the year 1602 in the old calendar. The modern convention is to use the old style calendar for the day and month while using the new style calendar for the year.

Elizabeth's coffin was carried downriver at night to Whitehall, on a barge lit with torches. At her funeral on 28 April, the coffin was taken to Westminster Abbey on a hearse drawn by four horses hung with black velvet. In the words of the chronicler John Stow:

Elizabeth was interred in Westminster Abbey, in a tomb shared with her half-sister, Mary I. The Latin inscription on their tomb, , translates to "Consorts in realm and tomb, here we sleep, Elizabeth and Mary, sisters, in hope of resurrection".

Elizabeth I

at the official website of the British monarchy

Elizabeth I

at the official website of the Royal Collection Trust * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Elizabeth 01 1533 births 1603 deaths 16th-century English monarchs 16th-century English translators 16th-century English women 16th-century English writers 16th-century Irish monarchs 16th-century queens regnant 17th-century English monarchs 17th-century English people 17th-century English women 17th-century Irish monarchs 17th-century queens regnant Burials at Westminster Abbey Children of Henry VIII English Anglicans English people of the Anglo-Spanish War (1585–1604) English people of Welsh descent English pretenders to the French throne English women poets Founders of English schools and colleges House of Tudor People excommunicated by the Catholic Church People from Greenwich People of the French Wars of Religion Prisoners in the Tower of London Protestant monarchs Queens regnant of England Queens regnant of Ireland Regicides of Mary, Queen of Scots English princesses

Ireland

Ireland (, ; ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe. Geopolitically, the island is divided between the Republic of Ireland (officially Names of the Irish state, named Irelan ...

from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. She was the last and longest reigning monarch of the House of Tudor

The House of Tudor ( ) was an English and Welsh dynasty that held the throne of Kingdom of England, England from 1485 to 1603. They descended from the Tudors of Penmynydd, a Welsh noble family, and Catherine of Valois. The Tudor monarchs ruled ...

. Her eventful reign, and its effect on history and culture, gave name to the Elizabethan era.

Elizabeth was the only surviving child of Henry VIII and his second wife, Anne Boleyn. When Elizabeth was two years old, her parents' marriage was annulled, her mother was executed, and Elizabeth was declared illegitimate. Henry restored her to the line of succession when she was 10. After Henry's death in 1547, Elizabeth's younger half-brother Edward VI ruled until his own death in 1553, bequeathing the crown to a Protestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

cousin, Lady Jane Grey, and ignoring the claims of his two half-sisters, Mary and Elizabeth, despite statutes to the contrary. Edward's will was quickly set aside and the Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

Mary became queen, deposing Jane. During Mary's reign, Elizabeth was imprisoned for nearly a year on suspicion of supporting Protestant rebels.

Upon Mary's 1558 death, Elizabeth succeeded to the throne and set out to rule by good counsel. She depended heavily on a group of trusted advisers led by William Cecil, whom she created Baron Burghley. One of her first actions as queen was the establishment of an English Protestant church, of which she became the supreme governor. This arrangement, later named the Elizabethan Religious Settlement

The Elizabethan Religious Settlement is the name given to the religious and political arrangements made for England during the reign of Elizabeth I (1558–1603). The settlement, implemented from 1559 to 1563, marked the end of the English Ref ...

, would evolve into the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the State religion#State churches, established List of Christian denominations, Christian church in England and the Crown Dependencies. It is the mother church of the Anglicanism, Anglican Christian tradition, ...

. It was expected that Elizabeth would marry and produce an heir; however, despite numerous courtships, she never did. Because of this she is sometimes referred to as the "Virgin Queen". She was succeeded by her cousin, James VI of Scotland.

In government, Elizabeth was more moderate than her father and siblings had been. One of her mottoes was ("I see and keep silent"). In religion, she was relatively tolerant and avoided systematic persecution. After the pope declared her illegitimate in 1570, which in theory released English Catholics from allegiance to her, several conspiracies threatened her life, all of which were defeated with the help of her ministers' secret service, run by Francis Walsingham. Elizabeth was cautious in foreign affairs, manoeuvring between the major powers of France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

and Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

. She half-heartedly supported a number of ineffective, poorly resourced military campaigns in the Netherlands

, Terminology of the Low Countries, informally Holland, is a country in Northwestern Europe, with Caribbean Netherlands, overseas territories in the Caribbean. It is the largest of the four constituent countries of the Kingdom of the Nether ...

, France, and Ireland. By the mid-1580s, England could no longer avoid war with Spain.

As she grew older, Elizabeth became celebrated for her virginity. A cult of personality grew around her which was celebrated in the portraits, pageants, and literature of the day. The Elizabethan era is famous for the flourishing of English drama, led by playwrights such as William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 23 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

and Christopher Marlowe, the prowess of English maritime adventurers, such as Francis Drake and Walter Raleigh, and for the defeat of the Spanish Armada

The Spanish Armada (often known as Invincible Armada, or the Enterprise of England, ) was a Spanish fleet that sailed from Lisbon in late May 1588, commanded by Alonso de Guzmán, Duke of Medina Sidonia, an aristocrat without previous naval ...

. Some historians depict Elizabeth as a short-tempered, sometimes indecisive ruler, who enjoyed more than her fair share of luck. Towards the end of her reign, a series of economic and military problems weakened her popularity. Elizabeth is acknowledged as a charismatic performer ("Gloriana") and a dogged survivor ("Good Queen Bess") in an era when government was ramshackle and limited, and when monarchs in neighbouring countries faced internal problems that jeopardised their thrones. After the short, disastrous reigns of her half-siblings, her 44 years on the throne provided welcome stability for the kingdom and helped to forge a sense of national identity.

Early life

Elizabeth was born at Greenwich Palace on 7 September 1533 and was named after her grandmothers, Elizabeth of York and Lady Elizabeth Howard. She was the second child of

Elizabeth was born at Greenwich Palace on 7 September 1533 and was named after her grandmothers, Elizabeth of York and Lady Elizabeth Howard. She was the second child of Henry VIII of England

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is known for his Wives of Henry VIII, six marriages and his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. ...

born in wedlock to survive infancy. Her mother was Henry VIII's second wife, Anne Boleyn. At birth, Elizabeth was the heir presumptive to the English throne. Her elder half-sister Mary had lost her position as a legitimate heir when Henry annulled his marriage to Mary's mother, Catherine of Aragon

Catherine of Aragon (also spelt as Katherine,

historical Spanish: , now: ; 16 December 1485 – 7 January 1536) was List of English royal consorts, Queen of England as the Wives of Henry VIII, first wife of King Henry VIII from their marr ...

, to marry Anne, with the intent to sire a male heir and ensure the Tudor succession. She was baptised on 10 September 1533, and her godparents were Thomas Cranmer

Thomas Cranmer (2 July 1489 – 21 March 1556) was a theologian, leader of the English Reformation and Archbishop of Canterbury during the reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI and, for a short time, Mary I. He is honoured as a Oxford Martyrs, martyr ...

, Archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the Primus inter pares, ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the bishop of the diocese of Canterbury. The first archbishop ...

; Henry Courtenay, Marquess of Exeter; Elizabeth Stafford, Duchess of Norfolk; and Margaret Wotton, Dowager Marchioness of Dorset. A canopy was carried at the ceremony over the infant by her uncle George Boleyn, Viscount Rochford; John Hussey, Baron Hussey of Sleaford; Lord Thomas Howard; and William Howard, Baron Howard of Effingham.

Elizabeth was two years and eight months old when her mother was beheaded on 19 May 1536, four months after Catherine of Aragon's death from natural causes. Elizabeth was declared illegitimate and deprived of her place in the royal succession. Eleven days after Anne Boleyn's execution, Henry married Jane Seymour. Queen Jane died the next year shortly after the birth of their son, Edward

Edward is an English male name. It is derived from the Anglo-Saxon name ''Ēadweard'', composed of the elements '' ēad'' "wealth, fortunate; prosperous" and '' weard'' "guardian, protector”.

History

The name Edward was very popular in Anglo-S ...

, who was the undisputed heir apparent

An heir apparent is a person who is first in the order of succession and cannot be displaced from inheriting by the birth of another person. A person who is first in the current order of succession but could be displaced by the birth of a more e ...

to the throne. Elizabeth was placed in her half-brother's household and carried the chrisom, or baptismal cloth, at his christening.

Elizabeth's first governess, Margaret Bryan, wrote that she was "as toward a child and as gentle of conditions as ever I knew any in my life". Catherine Champernowne, better known by her later, married name of Catherine "Kat" Ashley, was appointed as Elizabeth's governess in 1537, and she remained Elizabeth's friend until her death in 1565. Champernowne taught Elizabeth four languages: French, Dutch, Italian, and Spanish. By the time William Grindal became her tutor in 1544, Elizabeth could write English, Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

, and Italian. Under Grindal, a talented and skilful tutor, she also progressed in French and Greek. By the age of 12, she was able to translate her stepmother Catherine Parr's religious work '' Prayers or Meditations'' from English into Italian, Latin, and French, which she presented to her father as a New Year's gift. From her teenage years and throughout her life, she translated works in Latin and Greek by numerous classical authors, including the '' Pro Marcello'' of Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, orator, writer and Academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises tha ...

, the '' De consolatione philosophiae'' of Boethius

Anicius Manlius Severinus Boethius, commonly known simply as Boethius (; Latin: ''Boetius''; 480–524 AD), was a Roman Roman Senate, senator, Roman consul, consul, ''magister officiorum'', polymath, historian, and philosopher of the Early Middl ...

, a treatise by Plutarch

Plutarch (; , ''Ploútarchos'', ; – 120s) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo (Delphi), Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for his ''Parallel Lives'', ...

, and the '' Annals'' of Tacitus. A translation of Tacitus from Lambeth Palace Library, one of only four surviving English translations from the early modern era, was confirmed as Elizabeth's own in 2019, after a detailed analysis of the handwriting and paper was undertaken.

After Grindal died in 1548, Elizabeth received her education under her brother Edward's tutor, Roger Ascham, a sympathetic teacher who believed that learning should be engaging. Current knowledge of Elizabeth's schooling and precocity comes largely from Ascham's memoirs. By the time her formal education ended in 1550, Elizabeth was one of the best educated women of her generation. At the end of her life, she was believed to speak the Welsh, Cornish, Scottish, and Irish language

Irish (Standard Irish: ), also known as Irish Gaelic or simply Gaelic ( ), is a Celtic language of the Indo-European language family. It is a member of the Goidelic languages of the Insular Celtic sub branch of the family and is indigenous ...

s in addition to those mentioned above. The Venetian ambassador stated in 1603 that she "possessed heselanguages so thoroughly that each appeared to be her native tongue". Historian Mark Stoyle suggests that she was probably taught Cornish by William Killigrew, Groom of the Privy Chamber and later Chamberlain of the Exchequer.

Thomas Seymour

Henry VIII died in 1547 and Elizabeth's half-brother, Edward VI, became king at the age of nine. Catherine Parr, Henry's widow, soon married Thomas Seymour, Baron Seymour of Sudeley, Edward VI's uncle and the brother of Lord Protector Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset. The couple took Elizabeth into their household at Chelsea. There Elizabeth experienced an emotional crisis that some historians believe affected her for the rest of her life. Thomas Seymour engaged in romps and horseplay with the 14-year-old Elizabeth, including entering her bedroom in his nightgown, tickling her, and slapping her on the buttocks. Elizabeth rose early and surrounded herself with maids to avoid his unwelcome morning visits. Parr, rather than confront her husband over his inappropriate activities, joined in. Twice she accompanied him in tickling Elizabeth, and once held her while he cut her black gown "into a thousand pieces". However, after Parr discovered the pair in an embrace, she ended this state of affairs. In May 1548, Elizabeth was sent away.

Thomas Seymour nevertheless continued scheming to control the royal family and tried to have himself appointed the governor of the King's person. When Parr died after childbirth on 5 September 1548, he renewed his attentions towards Elizabeth, intent on marrying her. Her governess Kat Ashley, who was fond of Seymour, sought to convince Elizabeth to take him as her husband. She tried to convince Elizabeth to write to Seymour and "comfort him in his sorrow", but Elizabeth claimed that Thomas was not so saddened by her stepmother's death as to need comfort.

In January 1549, Seymour was arrested and imprisoned in the Tower on suspicion of conspiring to depose his brother Somerset as Protector, marry Lady Jane Grey to King Edward VI, and take Elizabeth as his own wife. Elizabeth, living at Hatfield House, would admit nothing. Her stubbornness exasperated her interrogator, Robert Tyrwhitt, who reported, "I do see it in her face that she is guilty". Seymour was beheaded on 20 March 1549.

Henry VIII died in 1547 and Elizabeth's half-brother, Edward VI, became king at the age of nine. Catherine Parr, Henry's widow, soon married Thomas Seymour, Baron Seymour of Sudeley, Edward VI's uncle and the brother of Lord Protector Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset. The couple took Elizabeth into their household at Chelsea. There Elizabeth experienced an emotional crisis that some historians believe affected her for the rest of her life. Thomas Seymour engaged in romps and horseplay with the 14-year-old Elizabeth, including entering her bedroom in his nightgown, tickling her, and slapping her on the buttocks. Elizabeth rose early and surrounded herself with maids to avoid his unwelcome morning visits. Parr, rather than confront her husband over his inappropriate activities, joined in. Twice she accompanied him in tickling Elizabeth, and once held her while he cut her black gown "into a thousand pieces". However, after Parr discovered the pair in an embrace, she ended this state of affairs. In May 1548, Elizabeth was sent away.

Thomas Seymour nevertheless continued scheming to control the royal family and tried to have himself appointed the governor of the King's person. When Parr died after childbirth on 5 September 1548, he renewed his attentions towards Elizabeth, intent on marrying her. Her governess Kat Ashley, who was fond of Seymour, sought to convince Elizabeth to take him as her husband. She tried to convince Elizabeth to write to Seymour and "comfort him in his sorrow", but Elizabeth claimed that Thomas was not so saddened by her stepmother's death as to need comfort.

In January 1549, Seymour was arrested and imprisoned in the Tower on suspicion of conspiring to depose his brother Somerset as Protector, marry Lady Jane Grey to King Edward VI, and take Elizabeth as his own wife. Elizabeth, living at Hatfield House, would admit nothing. Her stubbornness exasperated her interrogator, Robert Tyrwhitt, who reported, "I do see it in her face that she is guilty". Seymour was beheaded on 20 March 1549.

Reign of Mary

Edward VI died on 6 July 1553, aged 15. His will ignored the Succession to the Crown Act 1543, excluded both Mary and Elizabeth from the succession, and instead declared as his heir Lady Jane Grey, granddaughter of Henry VIII's younger sister Mary Tudor, Queen of France. Jane was proclaimed queen by the privy council, but her support quickly crumbled, and she was deposed after nine days. On 3 August 1553, Mary rode triumphantly into London, with Elizabeth at her side. The show of solidarity between the sisters did not last long. Mary, a devoutCatholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

, was determined to crush the Protestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

faith in which Elizabeth had been educated, and she ordered that everyone attend Catholic Mass; Elizabeth outwardly conformed. Mary's initial popularity ebbed away in 1554 when she announced plans to marry Philip of Spain, the son of Holy Roman Emperor Charles V and a Catholic. Discontent spread rapidly through the country, and many looked to Elizabeth as a focus for their opposition to Mary's religious policies.

In January and February 1554, Wyatt's rebellion broke out; it was soon suppressed. Elizabeth was brought to court and interrogated regarding her role, and on 18 March, she was imprisoned in the Tower of London. Elizabeth fervently protested her innocence. Though it is unlikely that she had plotted with the rebels, some of them were known to have approached her. Mary's closest confidant, Emperor Charles's ambassador Simon Renard, argued that her throne would never be safe while Elizabeth lived; and Lord Chancellor Stephen Gardiner, worked to have Elizabeth put on trial. Elizabeth's supporters in the government, including William Paget, 1st Baron Paget, convinced Mary to spare her sister in the absence of hard evidence against her. Instead, on 22 May, Elizabeth was moved from the Tower to Woodstock Palace, where she was to spend almost a year under house arrest in the charge of Henry Bedingfeld. Crowds cheered her all along the way.

On 17 April 1555, Elizabeth was recalled to court to attend the final stages of Mary's apparent pregnancy. If Mary and her child died, Elizabeth would become queen, but if Mary gave birth to a healthy child, Elizabeth's chances of becoming queen would recede sharply. When it became clear that Mary was not pregnant, no one believed any longer that she could have a child. Elizabeth's succession seemed assured.

King Philip, who ascended the Spanish throne in 1556, acknowledged the new political reality and cultivated his sister-in-law. She was a better ally than the chief alternative, Mary, Queen of Scots

Mary, Queen of Scots (8 December 1542 – 8 February 1587), also known as Mary Stuart or Mary I of Scotland, was List of Scottish monarchs, Queen of Scotland from 14 December 1542 until her forced abdication in 1567.

The only surviving legit ...

, who had grown up in France and was betrothed to Francis, Dauphin of France. When his wife fell ill in 1558, Philip sent the Count of Feria to consult with Elizabeth. This interview was conducted at Hatfield House, where she had returned to live in October 1555. By October 1558, Elizabeth was already making plans for her government. Mary recognised Elizabeth as her heir on 6 November 1558 and Elizabeth became queen when Mary died on 17 November.

Accession

Elizabeth became queen at the age of 25, and declared her intentions to her council and other peers who had come to Hatfield to swear allegiance. The speech contains the first record of her adoption of the medieval political theology of the sovereign's "two bodies": the body natural and the body politic:

As her triumphal progress wound through the city on the eve of the coronation ceremony, she was welcomed wholeheartedly by the citizens and greeted by orations and pageants, most with a strong Protestant flavour. Elizabeth's open and gracious responses endeared her to the spectators, who were "wonderfully ravished". The following day, 15 January 1559, a date chosen by her astrologer John Dee, Elizabeth was crowned and anointed by Owen Oglethorpe, the Catholic bishop of Carlisle, in Westminster Abbey. She was then presented for the people's acceptance, amidst a deafening noise of organs, fifes, trumpets, drums, and bells. Although Elizabeth was welcomed as queen in England, the country was still in a state of anxiety over the perceived Catholic threat at home and overseas, as well as the choice of whom she would marry.

Elizabeth became queen at the age of 25, and declared her intentions to her council and other peers who had come to Hatfield to swear allegiance. The speech contains the first record of her adoption of the medieval political theology of the sovereign's "two bodies": the body natural and the body politic:

As her triumphal progress wound through the city on the eve of the coronation ceremony, she was welcomed wholeheartedly by the citizens and greeted by orations and pageants, most with a strong Protestant flavour. Elizabeth's open and gracious responses endeared her to the spectators, who were "wonderfully ravished". The following day, 15 January 1559, a date chosen by her astrologer John Dee, Elizabeth was crowned and anointed by Owen Oglethorpe, the Catholic bishop of Carlisle, in Westminster Abbey. She was then presented for the people's acceptance, amidst a deafening noise of organs, fifes, trumpets, drums, and bells. Although Elizabeth was welcomed as queen in England, the country was still in a state of anxiety over the perceived Catholic threat at home and overseas, as well as the choice of whom she would marry.

Church settlement

Elizabeth's personal religious convictions have been much debated by scholars. She was a Protestant, but kept Catholic symbols (such as the crucifix), and downplayed the role of sermons in defiance of a key Protestant belief. Elizabeth and her advisers perceived the threat of a Catholic crusade against heretical England. The Queen therefore sought a Protestant solution that would not offend Catholics too greatly while addressing the desires of English Protestants, but she would not tolerate the Puritans, who were pushing for far-reaching reforms. As a result, the Parliament of 1559 started to legislate for a church based on the Protestant settlement of Edward VI, with the monarch as its head, but with many Catholic elements, such as vestments. TheHouse of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the Bicameralism, bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of ...

backed the proposals strongly, but the bill of supremacy met opposition in the House of Lords

The House of Lords is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Like the lower house, the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminster in London, England. One of the oldest ext ...

, particularly from the bishops. Elizabeth was fortunate that many bishoprics were vacant at the time, including the Archbishopric of Canterbury. This enabled supporters amongst peers to outvote the bishops and conservative peers. Nevertheless, Elizabeth was forced to accept the title of Supreme Governor of the Church of England rather than the more contentious title of Supreme Head, which many thought unacceptable for a woman to bear. The new Act of Supremacy became law on 8 May 1559. All public officials were forced to swear an oath of loyalty to the monarch as the supreme governor or risk disqualification from office; the heresy

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, particularly the accepted beliefs or religious law of a religious organization. A heretic is a proponent of heresy.

Heresy in Heresy in Christian ...

laws were repealed, to avoid a repeat of the persecution of dissenters by Mary. At the same time, a new Act of Uniformity was passed, which made attendance at church and the use of the 1559 ''Book of Common Prayer'' (an adapted version of the 1552 prayer book) compulsory, though the penalties for recusancy, or failure to attend and conform, were not extreme.

Marriage question

From the start of Elizabeth's reign it was expected that she would marry, and the question arose to whom. Although she received many offers, she never married and remained childless; the reasons for this are not clear. Historians have speculated that Thomas Seymour had put her off sexual relationships. She considered several suitors until she was about 50 years old. Her last courtship was with Francis, Duke of Anjou, 22 years her junior. While risking possible loss of power like her sister, who played into the hands of King Philip II of Spain, marriage offered the chance of an heir. However, the choice of a husband might also provoke political instability or even insurrection.Robert Dudley

In the spring of 1559, it became evident that Elizabeth was in love with her childhood friend Robert Dudley. It was said that his wife Amy was suffering from a "malady in one of her breasts" and that the Queen would like to marry Robert if his wife should die. By the autumn of 1559, several foreign suitors were vying for Elizabeth's hand; their impatient envoys engaged in ever more scandalous talk and reported that a marriage with her favourite was not welcome in England: "There is not a man who does not cry out on him and her with indignation ... she will marry none but the favoured Robert." Amy Dudley died in September 1560, from a fall from a flight of stairs and, despite the coroner's inquest finding of accident, many people suspected her husband of having arranged her death so that he could marry the Queen. Elizabeth seriously considered marrying Dudley for some time. However, William Cecil, Nicholas Throckmorton, and some conservative peers made their disapproval unmistakably clear. There were even rumours that the nobility would rise if the marriage took place.

Among other marriage candidates being considered for the queen, Robert Dudley continued to be regarded as a possible candidate for nearly another decade. Elizabeth was extremely jealous of his affections, even when she no longer meant to marry him herself. She raised Dudley to the peerage as

In the spring of 1559, it became evident that Elizabeth was in love with her childhood friend Robert Dudley. It was said that his wife Amy was suffering from a "malady in one of her breasts" and that the Queen would like to marry Robert if his wife should die. By the autumn of 1559, several foreign suitors were vying for Elizabeth's hand; their impatient envoys engaged in ever more scandalous talk and reported that a marriage with her favourite was not welcome in England: "There is not a man who does not cry out on him and her with indignation ... she will marry none but the favoured Robert." Amy Dudley died in September 1560, from a fall from a flight of stairs and, despite the coroner's inquest finding of accident, many people suspected her husband of having arranged her death so that he could marry the Queen. Elizabeth seriously considered marrying Dudley for some time. However, William Cecil, Nicholas Throckmorton, and some conservative peers made their disapproval unmistakably clear. There were even rumours that the nobility would rise if the marriage took place.

Among other marriage candidates being considered for the queen, Robert Dudley continued to be regarded as a possible candidate for nearly another decade. Elizabeth was extremely jealous of his affections, even when she no longer meant to marry him herself. She raised Dudley to the peerage as Earl of Leicester

Earl of Leicester is a title that has been created seven times. The first title was granted during the 12th century in the Peerage of England. The current title is in the Peerage of the United Kingdom and was created in 1837.

History

Earl ...

in 1564. In 1578, he finally married Lettice Knollys, to whom the queen reacted with repeated scenes of displeasure and lifelong hatred. Still, Dudley always "remained at the centre of lizabeth'semotional life", as historian Susan Doran has described the situation. He died shortly after the defeat of the Spanish Armada

The Spanish Armada (often known as Invincible Armada, or the Enterprise of England, ) was a Spanish fleet that sailed from Lisbon in late May 1588, commanded by Alonso de Guzmán, Duke of Medina Sidonia, an aristocrat without previous naval ...

in 1588. After Elizabeth's own death, a note from him was found among her most personal belongings, marked "his last letter" in her handwriting.

Foreign candidates

Marriage negotiations constituted a key element in Elizabeth's foreign policy. She turned down the hand of Philip, her half-sister's widower, early in 1559 but for several years entertained the proposal of King Eric XIV of Sweden. Earlier in Elizabeth's life, a Danish match for her had been discussed; Henry VIII had proposed one with the Danish prince Adolf, Duke of Holstein-Gottorp, in 1545, and Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset, suggested a marriage with Prince Frederick (later Frederick II) several years later, but the negotiations had abated in 1551. In the years around 1559, a Dano-English Protestant alliance was considered, and to counter Sweden's proposal, King Frederick II proposed to Elizabeth in late 1559. For several years, she seriously negotiated to marry Philip's cousin Charles II, Archduke of Austria. By 1569, relations with the Habsburgs had deteriorated. Elizabeth considered marriage to two French Valois princes in turn, first Henry, Duke of Anjou, and then from 1572 to 1581 his brother Francis, Duke of Anjou, formerly Duke of Alençon. This last proposal was tied to a planned alliance against Spanish control of the Southern Netherlands. Elizabeth seems to have taken the courtship seriously for a time, wearing a frog-shaped earring that Francis had sent her. In 1563, Elizabeth told an imperial envoy: "If I follow the inclination of my nature, it is this: beggar-woman and single, far rather than queen and married". Later in the year, following Elizabeth's illness withsmallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by Variola virus (often called Smallpox virus), which belongs to the genus '' Orthopoxvirus''. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (W ...

, the succession question became a heated issue in Parliament. Members urged the Queen to marry or nominate an heir, to prevent a civil war upon her death. She refused to do either. In April she prorogued the Parliament, which did not reconvene until she needed its support to raise taxes in 1566.

Having previously promised to marry, she told an unruly House:

By 1570, senior figures in the government privately accepted that Elizabeth would never marry or name a successor. William Cecil was already seeking solutions to the succession problem. For her failure to marry, Elizabeth was often accused of irresponsibility. Her silence, however, strengthened her own political security: she knew that if she named an heir, her throne would be vulnerable to a coup; she remembered the way that "a second person, as I have been" had been used as the focus of plots against her predecessor.

Virginity

Elizabeth's unmarried status inspired a cult of virginity related to that of the Virgin Mary. In poetry and portraiture, she was depicted as a virgin, a goddess, or both, not as a normal woman. At first, only Elizabeth made a virtue of her ostensible virginity: in 1559, she told the Commons, "And, in the end, this shall be for me sufficient, that a marble stone shall declare that a queen, having reigned such a time, lived and died a virgin". Later on, poets and writers took up the theme and developed an iconography that exalted Elizabeth. Public tributes to the Virgin by 1578 acted as a coded assertion of opposition to the queen's marriage negotiations with the Duke of Alençon. Ultimately, Elizabeth would insist she was married to her kingdom and subjects, under divine protection. In 1599, she spoke of "all my husbands, my good people". This claim of virginity was not universally accepted. Catholics accused Elizabeth of engaging in "filthy lust" that symbolically defiled the nation along with her body. Henry IV of France said that one of the great questions of Europe was "whether Queen Elizabeth was a maid or no".

A central issue, when it comes to the question of Elizabeth's virginity, was whether the Queen ever consummated her love affair with Robert Dudley. In 1559, she had Dudley's bedchambers moved next to her own apartments. In 1561, she was mysteriously bedridden with an illness that caused her body to swell.

In 1587, a young man calling himself Arthur Dudley was arrested on the coast of Spain under suspicion of being a spy. The man claimed to be the illegitimate son of Elizabeth and Robert Dudley, with his age being consistent with birth during the 1561 illness. He was taken to

This claim of virginity was not universally accepted. Catholics accused Elizabeth of engaging in "filthy lust" that symbolically defiled the nation along with her body. Henry IV of France said that one of the great questions of Europe was "whether Queen Elizabeth was a maid or no".

A central issue, when it comes to the question of Elizabeth's virginity, was whether the Queen ever consummated her love affair with Robert Dudley. In 1559, she had Dudley's bedchambers moved next to her own apartments. In 1561, she was mysteriously bedridden with an illness that caused her body to swell.

In 1587, a young man calling himself Arthur Dudley was arrested on the coast of Spain under suspicion of being a spy. The man claimed to be the illegitimate son of Elizabeth and Robert Dudley, with his age being consistent with birth during the 1561 illness. He was taken to Madrid

Madrid ( ; ) is the capital and List of largest cities in Spain, most populous municipality of Spain. It has almost 3.5 million inhabitants and a Madrid metropolitan area, metropolitan area population of approximately 7 million. It i ...

for investigation, where he was examined by Francis Englefield, a Catholic aristocrat exiled to Spain and secretary to King Philip II. Three letters exist today describing the interview, detailing what Arthur proclaimed to be the story of his life, from birth in the royal palace to the time of his arrival in Spain. However, this failed to convince the Spaniards: Englefield admitted to King Philip that Arthur's "claim at present amounts to nothing", but suggested that "he should not be allowed to get away, but ..kept very secure." The King agreed, and Arthur was never heard from again. Modern scholarship dismisses the story's basic premise as "impossible", and asserts that Elizabeth's life was so closely observed by contemporaries that she could not have hidden a pregnancy.

Mary, Queen of Scots

Elizabeth's first policy towardScotland

Scotland is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It contains nearly one-third of the United Kingdom's land area, consisting of the northern part of the island of Great Britain and more than 790 adjac ...

was to oppose the French presence there. She feared that the French planned to invade England and put her Catholic cousin Mary, Queen of Scots, on the throne. Mary was considered by many to be the heir to the English crown, being the granddaughter of Henry VIII's elder sister, Margaret

Margaret is a feminine given name, which means "pearl". It is of Latin origin, via Ancient Greek and ultimately from Iranian languages, Old Iranian. It has been an English language, English name since the 11th century, and remained popular thro ...

. Mary boasted being "the nearest kinswoman she hath". Elizabeth was persuaded to send a force into Scotland to aid the Protestant rebels, and though the campaign was inept, the resulting Treaty of Edinburgh of July 1560 removed the French threat in the north. When Mary returned from France to Scotland in 1561 to take up the reins of power, the country had an established Protestant church and was run by a council of Protestant nobles supported by Elizabeth. Mary refused to ratify the treaty.

In 1563, Elizabeth proposed her own suitor, Robert Dudley, as a husband for Mary, without asking either of the two people concerned. Both proved unenthusiastic, and in 1565, Mary married Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley, who carried his own claim to the English throne. The marriage was the first of a series of errors of judgement by Mary that handed the victory to the Scottish Protestants and to Elizabeth. Darnley quickly became unpopular and was murdered in February 1567 by conspirators almost certainly led by James Hepburn, Earl of Bothwell. Shortly afterwards, on 15 May 1567, Mary married Bothwell, arousing suspicions that she had been party to the murder of her husband. Elizabeth confronted Mary about the marriage, writing to her:

These events led rapidly to Mary's defeat and imprisonment in Lochleven Castle. The Scottish lords forced her to abdicate in favour of her one-year-old son, James VI. James was taken to Stirling Castle

Stirling Castle, located in Stirling, is one of the largest and most historically and architecturally important castles in Scotland. The castle sits atop an Intrusive rock, intrusive Crag and tail, crag, which forms part of the Stirling Sill ge ...

to be raised as a Protestant. Mary escaped in 1568 but after a defeat at Langside sailed to England, where she had once been assured of support from Elizabeth. Elizabeth's first instinct was to restore her fellow monarch, but she and her council instead chose to play safe. Rather than risk returning Mary to Scotland with an English army or sending her to France and the Catholic enemies of England, they detained her in England, where she was imprisoned for the next nineteen years.

Catholic cause

Mary was soon the focus for rebellion. In 1569 there was a major Catholic rising in the North; the goal was to free Mary, marry her to Thomas Howard, Duke of Norfolk, and put her on the English throne. After the rebels' defeat, over 750 of them were executed on Elizabeth's orders. In the belief that the revolt had been successful, Pope Pius V issued a bull in 1570, titled '' Regnans in Excelsis'', which declared "Elizabeth, the pretended Queen of England and the servant of crime" to be excommunicated and a heretic, releasing all her subjects from any allegiance to her. Catholics who obeyed her orders were threatened with

Mary was soon the focus for rebellion. In 1569 there was a major Catholic rising in the North; the goal was to free Mary, marry her to Thomas Howard, Duke of Norfolk, and put her on the English throne. After the rebels' defeat, over 750 of them were executed on Elizabeth's orders. In the belief that the revolt had been successful, Pope Pius V issued a bull in 1570, titled '' Regnans in Excelsis'', which declared "Elizabeth, the pretended Queen of England and the servant of crime" to be excommunicated and a heretic, releasing all her subjects from any allegiance to her. Catholics who obeyed her orders were threatened with excommunication

Excommunication is an institutional act of religious censure used to deprive, suspend, or limit membership in a religious community or to restrict certain rights within it, in particular those of being in Koinonia, communion with other members o ...

. The papal bull provoked legislative initiatives against Catholics by Parliament, which were, however, mitigated by Elizabeth's intervention. In 1581, to convert English subjects to Catholicism with "the intent" to withdraw them from their allegiance to Elizabeth was made a treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state (polity), state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to Coup d'état, overthrow its government, spy ...

able offence, carrying the death penalty. From the 1570s missionary

A missionary is a member of a Religious denomination, religious group who is sent into an area in order to promote its faith or provide services to people, such as education, literacy, social justice, health care, and economic development.Thoma ...

priests from continental seminaries went to England secretly in the cause of the "reconversion of England". Some were executed for treasonable conduct, engendering a cult of martyrdom

A martyr (, ''mártys'', 'witness' stem , ''martyr-'') is someone who suffers persecution and death for advocating, renouncing, or refusing to renounce or advocate, a religious belief or other cause as demanded by an external party. In colloqui ...

.

''Regnans in Excelsis'' gave English Catholics a strong incentive to look to Mary as the legitimate sovereign of England. Mary may not have been told of every Catholic plot to put her on the English throne, but from the Ridolfi Plot of 1571 (which caused Mary's suitor, the Duke of Norfolk, to lose his head) to the Babington Plot

The Babington Plot was a plan in 1586 to assassinate Queen Elizabeth I, a Protestantism, Protestant, and put Mary, Queen of Scots, her Catholic Church, Catholic cousin, on the English throne. It led to Mary's execution, a result of a letter s ...

of 1586, Elizabeth's spymaster Francis Walsingham and the royal council keenly assembled a case against her. At first, Elizabeth resisted calls for Mary's death. By late 1586, she had been persuaded to sanction Mary's trial and execution on the evidence of letters written during the Babington Plot. Elizabeth's proclamation of the sentence announced that "the said Mary, pretending title to the same Crown, had compassed and imagined within the same realm diverse things tending to the hurt, death and destruction of our royal person." On 8 February 1587, Mary was beheaded at Fotheringhay Castle, Northamptonshire. After the execution, Elizabeth claimed that she had not intended for the signed execution warrant to be dispatched, and blamed her secretary, William Davison, for implementing it without her knowledge. The sincerity of Elizabeth's remorse and whether or not she wanted to delay the warrant have been called into question both by her contemporaries and later historians.

Wars

Elizabeth's foreign policy was largely defensive. The exception was the English occupation ofLe Havre

Le Havre is a major port city in the Seine-Maritime department in the Normandy (administrative region), Normandy region of northern France. It is situated on the right bank of the estuary of the Seine, river Seine on the English Channel, Channe ...

from October 1562 to June 1563, which ended in failure when Elizabeth's Huguenot allies joined with the Catholics to retake the port. Elizabeth's intention had been to exchange Le Havre for Calais, lost to France in January 1558. Only through the activities of her fleets did Elizabeth pursue an aggressive policy. This paid off in the war against Spain, 80% of which was fought at sea. She knighted Francis Drake after his circumnavigation of the globe from 1577 to 1580, and he won fame for his raids on Spanish ports and fleets. An element of piracy

Piracy is an act of robbery or criminal violence by ship or boat-borne attackers upon another ship or a coastal area, typically with the goal of stealing cargo and valuable goods, or taking hostages. Those who conduct acts of piracy are call ...

and self-enrichment drove Elizabethan seafarers, over whom the Queen had little control.

Netherlands

After the occupation and loss of Le Havre in 1562–1563, Elizabeth avoided military expeditions on the continent until 1585, when she sent an English army to aid the Protestant Dutch rebels against Philip II. This followed the deaths in 1584 of the Queen's allies William the Silent, Prince of Orange, and the Duke of Anjou, and the surrender of a series of Dutch towns to Alexander Farnese, Duke of Parma, Philip's governor of the Spanish Netherlands. In December 1584, an alliance between Philip II and the French Catholic League atJoinville

Joinville () is the largest city in Santa Catarina (state), Santa Catarina, in the Southern Brazil, Southern Region of Brazil. It is the third largest municipality in the southern region of Brazil, after the much larger state capitals of Curitib ...

undermined the ability of Anjou's brother, Henry III of France, to counter Spanish domination of the Netherlands. It also extended Spanish influence along the channel coast of France, where the Catholic League was strong, and exposed England to invasion. The siege of Antwerp in the summer of 1585 by the Duke of Parma necessitated some reaction on the part of the English and the Dutch. The outcome was the Treaty of Nonsuch of August 1585, in which Elizabeth promised military support to the Dutch. The treaty marked the beginning of the Anglo-Spanish War.

The expedition was led by Elizabeth's former suitor, the Earl of Leicester. Elizabeth from the start did not really back this course of action. Her strategy, to support the Dutch on the surface with an English army, while beginning secret peace talks with Spain within days of Leicester's arrival in Holland, had necessarily to be at odds with Leicester's, who had set up a protectorate and was expected by the Dutch to fight an active campaign. Elizabeth, on the other hand, wanted him "to avoid at all costs any decisive action with the enemy". He enraged Elizabeth by accepting the post of Governor-General from the Dutch States General. Elizabeth saw this as a Dutch ploy to force her to accept sovereignty over the Netherlands, which so far she had always declined. She wrote to Leicester: