Elijah Parish Lovejoy on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Elijah Parish Lovejoy (November 9, 1802 – November 7, 1837) was an American

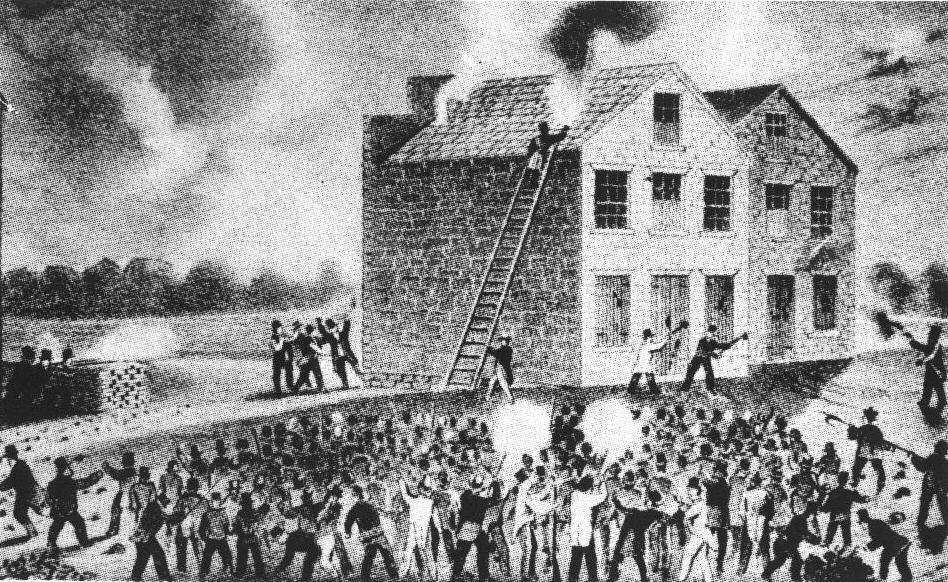

Lovejoy had acquired a fourth press and hid it in a warehouse owned by Winthrop Sargent Gilman and Gilford, major grocers in the area. A mob, said by ''Appleton's'' to be composed mostly of Missourians, attacked the building on the evening of November 6, 1837. Pro-slavery

Lovejoy had acquired a fourth press and hid it in a warehouse owned by Winthrop Sargent Gilman and Gilford, major grocers in the area. A mob, said by ''Appleton's'' to be composed mostly of Missourians, attacked the building on the evening of November 6, 1837. Pro-slavery

'What's In A Name: Profiles of the Trailblazers: History and Heritage of District of Columbia Public and Public Charter Schools'

** Lovejoy Elementary School in Alton, Illinois.

** LoveJoy United Presbyterian Church,

Biography from the Alton, Illinois web

*

, Reprint, ''Alton Observer'', November 7, 1837

St. Louis Walk of Fame

See also papers of nephew Austin Wiswall, officer with 9th

"Old Des Peres Presbyterian Church" (1834)

Frontenac, MO, where Lovejoy preached in its early years *

{{DEFAULTSORT:Lovejoy, Elijah P. 1802 births 1837 deaths People murdered in 1837 19th-century American newspaper editors 19th-century American male writers 19th-century American Presbyterian ministers Abolitionists from Maine American anti-abolitionist riots and civil disorder American male journalists Assassinated American journalists Colby College alumni Deaths by firearm in Illinois American free speech activists Journalists from Maine Journalists killed in the United States Lynching deaths in Illinois November 1838 Origins of the American Civil War People from Alton, Illinois People from Albion, Maine People murdered in Illinois Princeton Theological Seminary alumni Presbyterian abolitionists Presbyterian Church (USA) teaching elders Racially motivated violence in Illinois Riots and civil disorder in Illinois Riots and civil disorder in Missouri St. Louis Observer people Unsolved murders in the United States Writers from Illinois Writers from Maine Writers from Missouri

Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a historically Reformed Protestant tradition named for its form of church government by representative assemblies of elders, known as "presbyters". Though other Reformed churches are structurally similar, the word ''Pr ...

minister, journalist, newspaper editor

An editor-in-chief (EIC), also known as lead editor or chief editor, is a publication's editorial leader who has final responsibility for its operations and policies. The editor-in-chief heads all departments of the organization and is held account ...

, and abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the political movement to end slavery and liberate enslaved individuals around the world.

The first country to fully outlaw slavery was Kingdom of France, France in 1315, but it was later used ...

. After his murder by a mob, he became a martyr

A martyr (, ''mártys'', 'witness' Word stem, stem , ''martyr-'') is someone who suffers persecution and death for advocating, renouncing, or refusing to renounce or advocate, a religious belief or other cause as demanded by an external party. In ...

to the abolitionist cause opposing slavery in the United States

The legal institution of human chattel slavery, comprising the enslavement primarily of List of ethnic groups of Africa, Africans and African Americans, was prevalent in the United States of America from its founding in 1776 until 1865 ...

. He was also hailed as a defender of free speech

Freedom of speech is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or a community to articulate their opinions and ideas without fear of retaliation, censorship, or legal sanction. The right to freedom of expression has been recognise ...

and freedom of the press

Freedom of the press or freedom of the media is the fundamental principle that communication and expression through various media, including printed and electronic Media (communication), media, especially publication, published materials, shoul ...

.

Lovejoy was born in New England

New England is a region consisting of six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York (state), New York to the west and by the ...

and graduated from what is today Colby College

Colby College is a private liberal arts college in Waterville, Maine, United States. Founded in 1813 as the Maine Literary and Theological Institution, it was renamed Waterville College in 1821. The donations of Christian philanthropist Gardner ...

. Unsatisfied with a teaching career, he was drawn to journalism and decided to 'go west'. In 1827, he reached St. Louis

St. Louis ( , sometimes referred to as St. Louis City, Saint Louis or STL) is an independent city in the U.S. state of Missouri. It lies near the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a populatio ...

, Missouri

Missouri (''see #Etymology and pronunciation, pronunciation'') is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking List of U.S. states and territories by area, 21st in land area, it border ...

. Under the Missouri Compromise

The Missouri Compromise (also known as the Compromise of 1820) was federal legislation of the United States that balanced the desires of northern states to prevent the expansion of slavery in the country with those of southern states to expand ...

of 1820, Missouri entered the United States as a slave state

In the United States before 1865, a slave state was a state in which slavery and the internal or domestic slave trade were legal, while a free state was one in which they were prohibited. Between 1812 and 1850, it was considered by the slave s ...

. Lovejoy edited a newspaper but returned east for a time to study for the ministry at Princeton University

Princeton University is a private university, private Ivy League research university in Princeton, New Jersey, United States. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth, New Jersey, Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the List of Colonial ...

. On his return to St. Louis, he founded the '' St. Louis Observer'', in which he became increasingly critical of slavery and the powerful interests protecting slavery. Facing threats and violent attacks, Lovejoy decided to move across the river to Alton in Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern United States. It borders on Lake Michigan to its northeast, the Mississippi River to its west, and the Wabash River, Wabash and Ohio River, Ohio rivers to its ...

, a free state. However, Alton was also tied to the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the main stem, primary river of the largest drainage basin in the United States. It is the second-longest river in the United States, behind only the Missouri River, Missouri. From its traditional source of Lake Ita ...

economy, easily reachable by anti-Lovejoy Missourians, and badly split over abolitionism.

In Alton, Lovejoy was fatally shot during an attack by a pro-slavery mob. The mob was seeking to destroy a warehouse owned by Winthrop Sargent Gilman and Benjamin Godfrey, which held Lovejoy's printing press

A printing press is a mechanical device for applying pressure to an inked surface resting upon a printing, print medium (such as paper or cloth), thereby transferring the ink. It marked a dramatic improvement on earlier printing methods in whi ...

and abolitionist materials. According to John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams (; July 11, 1767 – February 23, 1848) was the sixth president of the United States, serving from 1825 to 1829. He previously served as the eighth United States secretary of state from 1817 to 1825. During his long diploma ...

, the murder "ave

is a Latin word, used by the Roman Empire, Romans as a salutation (greeting), salutation and greeting, meaning 'wikt:hail, hail'. It is the singular imperative mood, imperative form of the verb , which meant 'Well-being, to be well'; thus on ...

a shock as of an earthquake throughout this country." The '' Boston Recorder'' wrote that "these events called forth from every part of the land 'a burst of indignation which has not had its parallel in this country since the Battle of Lexington

The Battles of Lexington and Concord on April 19, 1775 were the first major military actions of the American Revolutionary War between the Kingdom of Great Britain and Patriot (American Revolution), Patriot militias from America's Thirteen Co ...

.'" When informed about the murder, John Brown said publicly: "Here, before God, in the presence of these witnesses, from this time, I consecrate my life to the destruction of slavery." Lovejoy is often seen as a martyr to the abolitionist cause and to a free press. The Lovejoy Monument was erected in Alton in 1897.

Early life and education

Elijah Parish Lovejoy was born at his paternal grandparents' frontier farmhouse near Albion, Maine (then part ofMassachusetts

Massachusetts ( ; ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Maine to its east, Connecticut and Rhode ...

), the eldest of nine children of Elizabeth (née Pattee) Lovejoy and Daniel Lovejoy. Lovejoy's father was a Congregational

Congregationalism (also Congregational Churches or Congregationalist Churches) is a Reformed Christianity, Reformed Christian (Calvinist) tradition of Protestant Christianity in which churches practice Congregationalist polity, congregational ...

preacher and farmer, and his mother was a homemaker and a devout Christian. Daniel Lovejoy named his son in honor of his close friend and mentor, Elijah Parish, a minister who was also involved in politics. Due to his own lack of education, the father encouraged his sons – Elijah, Daniel, Joseph Cammett, Owen

Owen may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Owen (name), including a list of people and fictional characters with the given name or surname

Places United States

* Owen, Missouri, a ghost town

* Owen, Wisconsin

* Owen County, Indiana

...

, and John – to become educated. Elijah was taught to read the Bible and other religious texts by his mother at an early age.

After completing early studies in public schools, Lovejoy attended the private Academy at Monmouth and China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

Academy. When sufficiently proficient in Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

and mathematics

Mathematics is a field of study that discovers and organizes methods, Mathematical theory, theories and theorems that are developed and Mathematical proof, proved for the needs of empirical sciences and mathematics itself. There are many ar ...

, he enrolled at Waterville College (now Colby College) as a sophomore in 1823. Lovejoy received financial support from minister Benjamin Tappan to continue his studies there. Based on faculty recommendations, from 1824 until his graduation in 1826, he also served as headmaster of Colby's associated high school, the Latin School (later known as the Coburn Classical Institute). In September 1826, Lovejoy graduated ''cum laude'' from Waterville, and was class valedictorian

Valedictorian is an academic title for the class rank, highest-performing student of a graduation, graduating class of an academic institution in the United States.

The valedictorian is generally determined by an academic institution's grade poin ...

.

Journey westward

During the winter and spring, he taught at China Academy inMaine

Maine ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the United States, and the northeasternmost state in the Contiguous United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Provinces and ...

. Dissatisfied with teaching, Lovejoy considered moving to the American South

The Southern United States (sometimes Dixie, also referred to as the Southern States, the American South, the Southland, Dixieland, or simply the South) is census regions United States Census Bureau. It is between the Atlantic Ocean and the ...

or westward to the Northwest Territory

The Northwest Territory, also known as the Old Northwest and formally known as the Territory Northwest of the River Ohio, was formed from part of the unorganized western territory of the United States after the American Revolution. Established ...

. His former teachers at Waterville College advised him that he would best serve God in the West (now considered the American Midwest

The Midwestern United States (also referred to as the Midwest, the Heartland or the American Midwest) is one of the four List of regions of the United States, census regions defined by the United States Census Bureau. It occupies the northern c ...

).

In May 1827, he went to Boston

Boston is the capital and most populous city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Massachusetts in the United States. The city serves as the cultural and Financial centre, financial center of New England, a region of the Northeas ...

to earn money for his journey, having settled on the free state of Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern United States. It borders on Lake Michigan to its northeast, the Mississippi River to its west, and the Wabash River, Wabash and Ohio River, Ohio rivers to its ...

as his destination. Unsuccessful at finding work, he started for Illinois by foot. He stopped in New York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

in mid-June to try to find work. He eventually landed a position with the ''Saturday Evening Gazette'' as a newspaper subscription peddler. For nearly five weeks, he worked to sell subscriptions.

Struggling with his finances, he wrote to Jeremiah Chaplin, president of Waterville College, explaining his situation. Chaplin sent the money that his former student needed. Before embarking on his journey westward, Lovejoy wrote a poem which later seemed to prophesy his death:

Career in Missouri

In 1827, Lovejoy arrived in St. Louis, Missouri, a major port in aslave state

In the United States before 1865, a slave state was a state in which slavery and the internal or domestic slave trade were legal, while a free state was one in which they were prohibited. Between 1812 and 1850, it was considered by the slave s ...

that shared its longest border with the free state of Illinois. Although it had a large slave market

A slave market is a place where slaves are bought and sold. These markets are a key phenomenon in the history of slavery.

Asia

Central Asia

Since antiquity, cities along the Silk road of Central Asia, had been centers of slave trade. In ...

, St. Louis identified itself less with the plantation South and more as the "gateway to the West" and the American "frontier."

Lovejoy initially ran a private school

A private school or independent school is a school not administered or funded by the government, unlike a State school, public school. Private schools are schools that are not dependent upon national or local government to finance their fina ...

in St. Louis with a friend, which they modeled after academies in the East. Lovejoy's interest in teaching waned, however, when local editors began publishing his poems in their newspapers.

''St. Louis Times''

In 1829, Lovejoy became a co-editor with T. J. Miller of the ''St. Louis Times'', which promoted the candidacy ofHenry Clay

Henry Clay (April 12, 1777June 29, 1852) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented Kentucky in both the United States Senate, U.S. Senate and United States House of Representatives, House of Representatives. He was the seventh Spea ...

for president of the United States. Working at the ''Times'' introduced him to like-minded community leaders, many of whom were members of the American Colonization Society

The American Colonization Society (ACS), initially the Society for the Colonization of Free People of Color of America, was an American organization founded in 1816 by Robert Finley to encourage and support the repatriation of freeborn peop ...

. They supported sending freed American blacks to Africa, considering it a kind of "repatriation." Opponents of the ACS including Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass (born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, February 14, 1818 – February 20, 1895) was an American social reformer, Abolitionism in the United States, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman. He was the most impor ...

noted most African Americans had been native-born for generations and considered their future to be in the U.S. Among Lovejoy's new acquaintances were prominent St. Louis attorneys and slaveholders such as Edward Bates

Edward Bates (September 4, 1793 – March 25, 1869) was an American lawyer, politician and judge. He represented Missouri in the US House of Representatives and served as the U.S. Attorney General under President Abraham Lincoln. A member ...

(later U.S. Attorney General under President Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

); Hamilton R. Gamble, later Chief Justice of the Missouri Supreme Court; and his brother Archibald Gamble.

Lovejoy occasionally hired slaves who were leased out by owners, to work with him at the paper. Among them was William Wells Brown

William Wells Brown (November 6, 1814 – November 6, 1884) was an American abolitionist, novelist, playwright, and historian. Born into slavery near Mount Sterling, Kentucky, Brown escaped to Ohio in 1834 at the age of 19. He settled in Boston, ...

, who later recounted his experience in a memoir. Brown described Lovejoy as "a very good man, and decidedly the best master that I had ever had. I am chiefly indebted to him, and to my employment in the printing office, for what little learning I obtained while in slavery."

Theological training

Lovejoy struggled with his interest in religion, often writing to his parents about his sinfulness and rebellion against God. He attended revival meetings in 1831 led by William S. Potts, pastor of First Presbyterian Church, that rekindled his interest in religion for a time. However, Lovejoy admitted to his parents that "gradually these feelings all left me, and I returned to the world a more hardened sinner than ever." A year later, Lovejoy found the call to God he had been yearning for. In 1832, influenced byChristian revival

Christian revival is defined as "a period of unusual blessing and activity in the life of the Christian Church". Proponents view revivals as the restoration of the Church to a vital and fervent relationship with God after a period of moral decl ...

ist meetings led by abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the political movement to end slavery and liberate enslaved individuals around the world.

The first country to fully outlaw slavery was Kingdom of France, France in 1315, but it was later used ...

David Nelson, he joined the First Presbyterian Church and decided to become a preacher. He sold his interest in the ''Times,'' and returned East to study at Princeton Theological Seminary

Princeton Theological Seminary (PTSem), officially The Theological Seminary of the Presbyterian Church, is a Private university, private seminary, school of theology in Princeton, New Jersey, Princeton, in the U.S. state of New Jersey. Establish ...

. While he was at Princeton, Lovejoy debated the question of slavery with an abolitionist named Bradford. Although Lovejoy had opposed abolitionism during the debate, after returning to St. Louis he would write to Bradford repeatedly asking him to write articles for his newspaper.

After graduation, he went to Philadelphia

Philadelphia ( ), colloquially referred to as Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania, most populous city in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania and the List of United States cities by population, sixth-most populous city in the Unit ...

, where he became an ordained minister of the Presbyterian Church

Presbyterianism is a historically Reformed Christianity, Reformed Protestantism, Protestant tradition named for its form of ecclesiastical polity, church government by representative assemblies of Presbyterian polity#Elder, elders, known as ...

on April 18, 1833.

''St. Louis Observer''

In 1833, a group of Protestants in St. Louis offered to finance a religious newspaper if Lovejoy would agree to return and edit it. Lovejoy accepted and on November 22, 1833, he published the first issue of the '' St. Louis Observer''. His editorials criticized both theCatholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

and slavery

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

. By 1830, sixty percent of the population of St. Louis was Catholic, and the proprietors of the ''Observer'' tasked Lovejoy with countering the increasing influence of Catholicism.

From the fall of 1833 to the summer 1836, Lovejoy regularly published articles criticizing the Catholic Church and church doctrine. Some were written by Lovejoy, while others were contributed by other authors. Initially, he criticized Catholic beliefs such as transubstantiation

Transubstantiation (; Greek language, Greek: μετουσίωσις ''metousiosis'') is, according to the teaching of the Catholic Church, "the change of the whole substance of sacramental bread, bread into the substance of the Body of Christ and ...

, clerical celibacy

Clerical celibacy is the requirement in certain religions that some or all members of the clergy be unmarried. Clerical celibacy also requires abstention from deliberately indulging in sexual thoughts and behavior outside of marriage, because thes ...

, and the influence of Catholicism on foreign governments. He also argued that "Popery

The words Popery (adjective Popish) and Papism (adjective Papist, also used to refer to an individual) are mainly historical pejorative words in the English language for Roman Catholicism, once frequently used by Protestants and Eastern Orthodox ...

" undermined the fundamental principles of American democracy. Local Catholics and clergy were offended by these attacks and regularly responded in articles of their own in ''The Shepherd of the Times'', a Catholic newspaper funded by Bishop Joseph Rosati.

In 1834, the ''St. Louis Observer'' began to increase its coverage of slavery, the most controversial issue of the day. At first, Lovejoy resisted calling himself an abolitionist, because he disliked the negative connotations associating abolitionism with social unrest. Even as he expressed antislavery views, he claimed to be an "emancipationist" rather than an "abolitionist." In the spring of 1835, the '' Missouri Republican'' advocated the gradual emancipation of slaves in Missouri, and Lovejoy voiced his support through the ''Observer''. Lovejoy urged antislavery groups in Missouri to push for the issue to be addressed during a proposed state constitutional convention. To their dismay, the editors of both newspapers soon found that their "moderate" proposal to end slavery gradually could not be discussed without igniting a polarizing political debate.

Over time, Lovejoy became bolder and more outspoken about his antislavery views, advocating the outright emancipation of all slaves on religious and moral grounds. Lovejoy condemned slavery and "implored all Christians who owned slaves to recognize that slaves were human beings who possessed a soul," and famously wrote:Slavery, as it exists among us ... is demonstrably an evil. In every community where it exists, it presses like a nightmare on the body politic. Or, like the vampire, it slowly and imperceptibly sucks away the life-blood of society, leaving it faint and disheartened to stagger along the road of improvement.

Threats of violence

Lovejoy's views on slavery began to incite complaints and threats. Pro-slavery proponents condemned anti-slavery coverage which appeared in newspapers, stating that it was against "the vital interests of the slaveholding states." Lovejoy was threatened to betarred and feathered

Tarring and feathering is a form of public torture where a victim is stripped naked, or stripped to the waist, while wood tar (sometimes hot) is either poured or painted onto the person. The victim then either has feathers thrown on them or is ...

if he continued to publish anti-slavery content.

By October 1835, there were rumors of mob action against ''The Observer.'' A group of prominent St. Louisans, including many of Lovejoy's friends, wrote a letter pleading with him to cease discussion of slavery in the newspaper. Lovejoy was away from the city at this time, and the publishers declared that no further articles on slavery would be published during his absence. They said that when he returned, he would follow a more rigorous editorial policy. Lovejoy responded by expressing disagreement with the publishers' policy. As tensions over slavery escalated in St. Louis, Lovejoy would not back down from his convictions; he sensed that he would become a martyr for the cause. He was asked to resign as editor of ''The Observer'', to which he agreed. After the newspaper's owners released ''The Observer'' property to the moneylender who held the mortgage, the new owners asked Lovejoy to stay on as editor.

Lynching of Francis McIntosh

Lovejoy and ''The Observer'' continued to be embroiled in controversy. In April 1836, Francis McIntosh, afree man of color

In the context of the history of slavery in the Americas, free people of color (; ) were primarily people of mixed African, European, and Indigenous peoples of the Americas, Native American descent who were not enslaved. However, the term also ...

and boatman, was arrested by two policemen. En route to the jail, McIntosh grabbed a knife and stabbed both men. One was killed and the other seriously injured. McIntosh attempted to escape, but was caught by a white mob, who tied him up and burned him to death. Some of the mob were brought before a grand jury to face charges. The presiding judge, Judge Luke Lawless, refused to convict anyone; he said the crime was a spontaneous mob action without any specific people to prosecute. The judge made remarks suggesting that abolitionists, including Lovejoy and ''The Observer,'' had incited McIntosh into stabbing the policemen.

Marriage and family

Lovejoy also served as an evangelist preacher. He traveled a circuit across the state, during which he met Celia Ann French of St. Charles, located on the Missouri River west of St. Louis, now a suburb of the city. She was the daughter of Thomas French, a lawyer who came to St. Charles in the 1820s. The couple were married on March 4, 1835. Their son Edward P. Lovejoy was born in 1836. Their second child was born after Elijah's death and died as an infant. In a letter to his mother, Elijah had written about Celia:My dear wife is a perfect heroine... never has she by a single word attempted to turn me from the scene of warfare and danger – never has she whispered a feeling of discontent at the hardships to which she has been subjected in consequence of her marriage to me, and those have been neither few nor small.

Move to Illinois

In the summer of 1836, Lovejoy attended the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church inPittsburgh

Pittsburgh ( ) is a city in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, United States, and its county seat. It is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania#Municipalities, second-most populous city in Pennsylvania (after Philadelphia) and the List of Un ...

and met several followers of abolitionist Theodore Weld. At the assembly, Lovejoy was frustrated by the church's hesitation to fully support petitions for abolition and drafted a protest submitted to church leadership. By this time, he had fully embraced the label of "abolitionist."

In the face of all the negative publicity and two break-ins in May 1836, Lovejoy decided to move ''The Observer'' across the Mississippi River to Alton, Illinois

Alton ( ) is a city on the Mississippi River in Madison County, Illinois, United States, about north of St. Louis, Missouri. The population was 25,676 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census. It is a part of the River Bend (Illinois), Riv ...

. At the time, Alton was a large and prosperous river port (many times larger than the frontier town of Chicago). Although Illinois was a free state, Alton was also a center for slave catchers and pro-slavery forces active in the southern area. Many refugee slaves crossed the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the main stem, primary river of the largest drainage basin in the United States. It is the second-longest river in the United States, behind only the Missouri River, Missouri. From its traditional source of Lake Ita ...

from Missouri

Missouri (''see #Etymology and pronunciation, pronunciation'') is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking List of U.S. states and territories by area, 21st in land area, it border ...

, and attempted to reach freedom on the underground railroad

The Underground Railroad was an organized network of secret routes and safe houses used by freedom seekers to escape to the abolitionist Northern United States and Eastern Canada. Enslaved Africans and African Americans escaped from slavery ...

. Among Alton's residents were pro-slavery Southerners who thought Alton should not become a haven for escaped slaves. John Glanville Gill, ''Tide Without Turning: Elijah P. Lovejoy and Freedom of the Press'' (1958).

On July 21, 1836, Lovejoy published a scathing editorial in St. Louis criticizing the way that the Missouri court's Judge Luke Lawless had handled the murder trial of Francis McIntosh. Arguing that the judge's actions appeared to condone the murder, he wrote that Lawless was "a Papist; and in his charge we see the cloven foot of Jesuitism." He also announced that his next issue would be printed in Alton. Before he could move the press, an angry mob

Mobbing, as a sociological term, refers either to bullying in any context, or specifically to that within the workplace, especially when perpetrated by a group rather than an individual.

Psychological and health effects

Victims of workplace mo ...

broke into ''The Observer'' office and vandalized it. Only Alderman and future mayor Bryan Mullanphy

Bryan Mullanphy (1809 in Baltimore, Maryland – June 15, 1851, in St. Louis, Missouri) was the tenth mayor of St. Louis, serving from 1847 to 1848.

Bryan Mullanphy was the son of John Mullanphy, an Irish immigrant who became a wealthy mercha ...

attempted to stop the crime, and no policemen or city officials intervened. Lovejoy packed what remained of the office for shipment to Alton. The printing press sat on the riverbank, unguarded, overnight; vandals destroyed it and threw the remains into the Mississippi River.

''Alton Observer''

Lovejoy served as pastor at Upper Alton Presbyterian Church (now College Avenue Presbyterian Church). In 1837, he started the '' Alton Observer'', also an abolitionist, Presbyterian paper. Lovejoy's views on slavery became more extreme, and he called for a convention to discuss forming an Illinois state chapter of theAmerican Anti-Slavery Society

The American Anti-Slavery Society (AASS) was an Abolitionism in the United States, abolitionist society in the United States. AASS formed in 1833 in response to the nullification crisis and the failures of existing anti-slavery organizations, ...

, established in Philadelphia in 1833.

Many residents of Alton began to question whether they should continue to allow Lovejoy to print in their town. After an economic crisis in March 1837, Alton citizens wondered if Lovejoy's views were contributing to hard times. They felt Southern states, or even the city of St. Louis, might not want to do business with their town if they continued to harbor such an outspoken abolitionist.

Lovejoy held the Illinois Antislavery Congress at the Presbyterian church in Upper Alton on October 26, 1837. Supporters were surprised to see two pro-slavery advocates in the crowd, John Hogan and Illinois Attorney General Usher F. Linder. The Lovejoy supporters were not happy to have his enemies at the convention, but relented as the meeting was open to all parties.

On November 2, 1837, Lovejoy responded to threats in a speech, saying:

Mob attack and death

partisan

Partisan(s) or The Partisan(s) may refer to:

Military

* Partisan (military), paramilitary forces engaged behind the front line

** Francs-tireurs et partisans, communist-led French anti-fascist resistance against Nazi Germany during WWII

** Ital ...

s approached Gilman's warehouse, where Lovejoy had hidden his printing press. The conflict continued. According to the ''Alton Observer'', the mob fired shots into the warehouse. When Lovejoy and his men returned fire, they hit several people in the crowd, killing a man named Bishop. After the attacking party had apparently withdrawn, Lovejoy opened the door and was instantly struck by five bullets, dying in a few minutes.

Jon Meacham

Jon Ellis Meacham (; born May 20, 1969) is an American writer, reviewer, historian and presidential biographer who is serving as the Canon Historian of the Washington National Cathedral since November 7, 2021. A former executive editor and execut ...

in his book ''And There Was Light: Abraham Lincoln and the American Struggle'' notes that Lovejoy was murdered on November 7, 1837, after he helped William Lloyd Garrison

William Lloyd Garrison (December , 1805 – May 24, 1879) was an Abolitionism in the United States, American abolitionist, journalist, and reformism (historical), social reformer. He is best known for his widely read anti-slavery newspaper ''The ...

found an Illinois chapter of Garrison's Anti-Slavery Society.

Elijah Lovejoy was buried in Alton Cemetery; his grave was unmarked to prevent vandalism. The ceremony was kept small. In 1864, journalist and lecturer Thomas Dimmock "reclaimed from oblivion" Lovejoy's grave. Dimmock had "succeeded in establishing the location of the grave... in a roadway where vehicles were passing over it... Mr. Dimmock had the bones disinterred and... laid in a new grave where they would be free from trespass." He also arranged for a gravestone and helped found a committee to create a monument to the editor. Dimmock was principal orator at the dedication of a later monument erected in 1897 to commemorate Lovejoy.

The ''Chicago Tribune'' said of the grave marking and association to fund a monument:

Alton riot trial

Francis B. Murdoch, the district attorney of Alton, prosecuted charges of riot related to both assailants and defenders of the warehouse in January 1838, on Wednesday and Friday of the same week. He called the Illinois Attorney General, Usher F. Linder, to assist him. Murdoch (with Linder) first prosecuted Gilman, owner of the warehouse, and eleven other defenders of the new press and building. They were indicted on two charges related to the riot at a trial opening January 16, 1838, for "unlawful defence", so defined and charged because it was "violently and tumultuously done." Gilman moved to be tried separately; his counsel said he needed to be able to show his lack of criminal intent. The court agreed on the condition that the other eleven defendants would be tried together. Although the proceedings lasted until 10 p.m. that night, in the case of Gilman, the jury returned after ten minutes to declare him "Not Guilty." The next morning the "City Attorney entered a 'Nolle Prosequi

, abbreviated or , is legal Latin meaning "to be unwilling to pursue".Nolle prosequi

. refe ...

' as to the other eleven defendants", effectively dismissing the charges against them.

A new jury was called to hear the case against the assailants of the warehouse. The attackers allegedly responsible for destruction of the warehouse and Lovejoy's death were tried beginning January 19, 1838. Concluding it was not possible to assign responsibility among the several suspects and others not indicted, the jury gave a verdict of "not guilty". The jury foreman had been identified as a member of the mob and was wounded in the attack. The presiding judge doubled as a witness to the proceedings. These conflicts of interest are believed to have contributed to the "not guilty" verdict.

. refe ...

Aftermath and legacy

After Lovejoy was killed, there was a dramatic increase in the number of people in the North and the West who joined anti-slavery societies, which formed beginning in the 1830s. Partly because he was a clergyman, there was outrage about his death. It became a catalyst for other pro- and anti-slavery events, likeJohn Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry

John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry was an effort by abolitionist John Brown, from October 16th to 18th, 1859, to initiate a slave revolt in Southern states by taking over the United States arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia (since 1863, We ...

, that culminated with the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

.

Lovejoy was considered a martyr

A martyr (, ''mártys'', 'witness' Word stem, stem , ''martyr-'') is someone who suffers persecution and death for advocating, renouncing, or refusing to renounce or advocate, a religious belief or other cause as demanded by an external party. In ...

by the abolition movement. In his name, his brother Owen Lovejoy became the leader of the Illinois abolitionists. Owen and his brother Joseph wrote a memoir about Elijah, which was published in 1838 by the Anti-Slavery Society in New York and distributed widely among abolitionists in the nation. With his killing symbolic of the rising tensions within the country, Lovejoy is called the "first casualty of the Civil War."

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

referred to Lovejoy in his Lyceum address in January 1838. About Lovejoy's murder, Lincoln said, "Let every man remember that to violate the law gainst violence is to trample on the blood of his father, and to tear the charter of his own, and his children's liberty... Let reverence for the laws be breathed by every American mother...in short let it become the political religion of the nation..."; he warned that the United States could only fail if it was torn apart internally.

John Brown was inspired by Lovejoy's death. At a church meeting the Sunday after Lovejoy's murder, he vowed to commit his life to abolition. Two neighbors recalled that he announced: "I pledge myself, with God's help, that I devote my life to increasing hostility to slavery." A later recollection by his half-brother Edward Brown had a different formulation: "Here, before God, in the presence of these witnesses, from this time, I consecrate my life to the destruction of slavery."

John Glanville Gill completed his Ph.D. at Harvard in 1946 on ''The Issues Involved in the Death of the Rev. Elijah P. Lovejoy, Alton, 1837''. This thesis was adapted and published in 1958 as the first biography of Lovejoy, entitled ''Tide Without Turning: Elijah P. Lovejoy and Freedom of the Press''.

Honors and awards

* Rankin was a 2013 Inductee into the National Abolition Hall of Fame inPeterboro, New York

Peterboro, located approximately southeast of Syracuse, New York, is a historic Hamlet (New York), hamlet and currently the administrative center for the Smithfield, New York, Town of Smithfield, Madison County, New York, Madison County, New Y ...

.

** The Elijah Parish Lovejoy Award was established by Colby College

Colby College is a private liberal arts college in Waterville, Maine, United States. Founded in 1813 as the Maine Literary and Theological Institution, it was renamed Waterville College in 1821. The donations of Christian philanthropist Gardner ...

in his honor. It is awarded annually to a member of the press who "has contributed to the nation's journalistic achievement." A major classroom building at Colby is also named for Lovejoy. An inscribed memorial rock from his birthplace was installed in a grassy square at Colby.

** In 2003, Reed College

Reed College is a Private college, private Liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts college in Portland, Oregon, United States. Founded in 1908, Reed is a residential college with a campus in the Eastmoreland, Portland, Oregon, E ...

established the Elijah Parish and Owen Lovejoy Scholarship, which it awards annually.

* Memorials and plaques

** In 1897, the 110-foot tall Elijah P. Lovejoy Monument was erected at Alton's City Cemetery; $25,000 had been appropriated by the state legislature, and $5,000 raised by residents of Alton and other supporters.

** A plaque honoring Elijah Parish Lovejoy was installed on an external wall at the Mackay Campus Center at his alma mater, Princeton Theological Seminary.

** He is the first person listed in the "Journalists Memorial" located at the Newseum, 555 Pennsylvania Avenue NW, Washington, DC.

** Elijah Lovejoy is recognized by a star on the St. Louis Walk of Fame.

* Numerous places and institutions were named after him:

** The majority African-American village of Brooklyn, Illinois, located just north of East St. Louis, is popularly known as 'Lovejoy' in his honor.

** The Presbytery of Giddings-Lovejoy, Presbyterian Church (USA)

The Presbyterian Church (USA), abbreviated PCUSA, is a mainline Protestant Christian denomination, denomination in the Religion in the United States, United States. It is the largest Presbyterian denomination in the United States too. Its th ...

, formed on January 3, 1985, from the merger of Elijah Parish Lovejoy Presbytery and the Presbytery of Southeast Missouri.

** Lovejoy Health Center in Albion, Maine, his birthplace.

** The Lovejoy School in Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from Virginia, and shares land borders with ...

was named in his honor in 1870. It moved to a new Victorian building at 12th and D Street NE in 1872, and closed in 1988. It was adapted and converted to the Lovejoy Lofts condominiums in 2004.Wood River, Illinois

Wood River is a city in Madison County, Illinois. The population was 10,464 as of the 2020 census.

Geography

Wood River is located in western Madison County on the Mississippi River approximately upstream of downtown St. Louis, Missouri. It is ...

** Lovejoy Library at Southern Illinois University Edwardsville

Southern Illinois University Edwardsville (SIUE) is a public university in Edwardsville, Illinois, United States. Located within the Metro East of Greater St. Louis, SIUE was established in 1957 as an extension of Southern Illinois University Ca ...

See also

* List of lynchings and other homicides in Illinois *Censorship in the United States

In the United States, censorship involves the suppression of speech or public communication and raises issues of freedom of speech, which is protected by the First Amendment to the United States Constitution. Interpretation of this fundamen ...

* List of journalists killed in the United States

* List of unsolved murders

* The Rev. John R. Anderson who worked for Lovejoy and witnessed his murder

Notes

References

Citations

Works cited

* * * * * * * * (first published in Chicago, 1881; reprint edition 1971) *Further reading

N.B.: Please keep in descending chronological order (most recent first). * * * (Biography for middle-grade readers.) * * *External links

Biography from the Alton, Illinois web

*

, Reprint, ''Alton Observer'', November 7, 1837

St. Louis Walk of Fame

See also papers of nephew Austin Wiswall, officer with 9th

United States Colored Troops

United States Colored Troops (USCT) were Union Army regiments during the American Civil War that primarily comprised African Americans, with soldiers from other ethnic groups also serving in USCT units. Established in response to a demand fo ...

, captured and held in prison at Andersonville, Georgia

Andersonville is a city in Sumter County, Georgia, United States. As of the 2020 census, the city had a population of 237. It is located in the southwest part of the state, approximately southwest of Macon on the Central of Georgia railroad ...

.

* – Anne Silverwood Twitty, ''Slavery and Freedom in the American Confluence, from the Northwest Ordinance to Dred Scott''], Ph.D. dissertation, Princeton University, 2010,

"Old Des Peres Presbyterian Church" (1834)

Frontenac, MO, where Lovejoy preached in its early years *

{{DEFAULTSORT:Lovejoy, Elijah P. 1802 births 1837 deaths People murdered in 1837 19th-century American newspaper editors 19th-century American male writers 19th-century American Presbyterian ministers Abolitionists from Maine American anti-abolitionist riots and civil disorder American male journalists Assassinated American journalists Colby College alumni Deaths by firearm in Illinois American free speech activists Journalists from Maine Journalists killed in the United States Lynching deaths in Illinois November 1838 Origins of the American Civil War People from Alton, Illinois People from Albion, Maine People murdered in Illinois Princeton Theological Seminary alumni Presbyterian abolitionists Presbyterian Church (USA) teaching elders Racially motivated violence in Illinois Riots and civil disorder in Illinois Riots and civil disorder in Missouri St. Louis Observer people Unsolved murders in the United States Writers from Illinois Writers from Maine Writers from Missouri